- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches

- John W. Creswell - Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan

- J. David Creswell - Carnegie Mellon University, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

“A long time ago, I participated in one of Dr. Creswell’s workshops on mixed methods research.... I am still learning from Dr. Creswell. I appreciate how he takes complex topics and makes them accessible to everyone. But I must caution my students that Dr. Creswell’s easygoing cadence and elegant descriptions sometimes mask the depth of the material. This reminds me of why he is such a highly respected researcher and teacher.”

“I always have enjoyed using Creswell's books (as a student and as an instructor) because the writing is straightforward.”

“This book is based around dissertation chapters, and that's why I love it using in my class. Practical, concise, and to the point!”

“This book is easy to use. The information and additional charts are also helpful.”

Clear material, student support website, and faculty resources.

The book provides a comprehensive overview and does well at demystifying the research philosophy. I have recommended it to my level 7 students for their dissertation project.

This book will be added to next academic year's reading list.

I am fed up with trying to get access to this "inspection copy". You don't respond to emails (and the email addresses you provide do not work). I get regular emails from you saying my ebook order is ready, but it does not appear in VitalSource and I cannot access it through any link on this web page. I am not willing to waste any more time on this. There are good alternatives.

Excellent introduction for research methods.

Creswell has always had excellent textbooks. Sixth Edition is no exception!

- Fully updated for the 7th edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association.

- More inclusive and supportive language throughout helps readers better see themselves in the research process.

- Learning Objectives provide additional structure and clarity to the reading process.

- The latest information on participatory research, evaluating literature for quality, using software to design literature maps, and additional statistical software types is newly included in this edition.

- Chapter 4: Writing Strategies and Ethical Considerations now includes information on indigenous populations and data collection after IRB review.

- An updated Chapter 8: Quantitative Methods now includes more foundational details, such as Type 1 and Type 2 errors and discussions of advantages and disadvantages of quantitative designs.

- A restructured and revised Chapter 10: Mixed Methods Procedures brings state-of-the-art thinking to this increasingly popular approach.

- Chapters 8, 9, and 10 now have parallel structures so readers can better compare and contrast each approach.

- Reworked end-of-chapter exercises offer a more straightforward path to application for students.

- New research examples throughout the text offer students contemporary studies for evaluation.

- Current references and additional readings are included in this new edition.

- Compares qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research in one book for unparalleled coverage.

- Highly interdisciplinary examples make this book widely appealing to a broad range of courses and disciplines.

- Ethical coverage throughout consistently reminds students to use good judgment and to be fair and unbiased in their research.

- Writing exercises conclude each chapter so that readers can practice the principles learned in the chapter; if the reader completes all of the exercises, they will have a written plan for their scholarly study.

- Numbered points provide checklists of each step in a process.

- Annotated passages help reinforce the reader's comprehension of key research ideas.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1: The Selection of a Research Approach

Chapter 2: Review of the Literature

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, and Triangulation Research Simplified

- PMID: 38567919

- DOI: 10.3928/00220124-20240328-03

For the novice nurse researcher, identifying a clinical researchable problem may be simple, but discerning an appropriate research approach may be daunting. What are the differences among quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and triangulation research? Which method is applicable for the study one wants to conduct? This article discusses the two main research traditions (quantitative and qualitative) and the differences and similarities in methods for front-line nurses. It simplifies and clarifies how the reader might enhance the rigor of the research study by using mixed methods or triangulation. The four types of research are described, and examples are provided to support readers to plan projects, use the most appropriate method, and effectively communicate findings. [ J Contin Educ Nurs. 202x;5x(x):xx-xx.] .

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Education & Teaching

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

- Highlight, take notes, and search in the book

- In this edition, page numbers are just like the physical edition

Rent $35.71

Today through selected date:

Rental price is determined by end date.

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches 6th Edition, Kindle Edition

- ISBN-13 978-1071817940

- Edition 6th

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher SAGE Publications, Inc

- Publication date October 24, 2022

- Language English

- File size 22105 KB

- See all details

- Kindle (5th Generation)

- Kindle Keyboard

- Kindle (2nd Generation)

- Kindle (1st Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite

- Kindle Paperwhite (5th Generation)

- Kindle Touch

- Kindle Voyage

- Kindle Oasis

- Kindle Scribe (1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire HDX 8.9''

- Kindle Fire HDX

- Kindle Fire HD (3rd Generation)

- Fire HDX 8.9 Tablet

- Fire HD 7 Tablet

- Fire HD 6 Tablet

- Kindle Fire HD 8.9"

- Kindle Fire HD(1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire(2nd Generation)

- Kindle Fire(1st Generation)

- Kindle for Windows 8

- Kindle for Windows Phone

- Kindle for BlackBerry

- Kindle for Android Phones

- Kindle for Android Tablets

- Kindle for iPhone

- Kindle for iPod Touch

- Kindle for iPad

- Kindle for Mac

- Kindle for PC

- Kindle Cloud Reader

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

John W. Creswell, PhD, is a professor of family medicine and senior research scientist at the Michigan Mixed Methods Program at the University of Michigan. He has authored numerous articles and 30 books on mixed methods research, qualitative research, and research design. While at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, he held the Clifton Endowed Professor Chair, served as Director of the Mixed Methods Research Office, founded SAGE’s Journal of Mixed Methods Research , and was an adjunct professor of family medicine at the University of Michigan and a consultant to the Veterans Administration health services research center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He was a Senior Fulbright Scholar to South Africa in 2008 and to Thailand in 2012. In 2011, he co-led a National Institute of Health working group on the “best practices of mixed methods research in the health sciences,” and in 2014 served as a visiting professor at Harvard’s School of Public Health. In 2014, he was the founding President of the Mixed Methods International Research Association. In 2015, he joined the staff of Family Medicine at the University of Michigan to Co-Direct the Michigan Mixed Methods Program. In 2016, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Pretoria, South Africa. In 2017, he co-authored the American Psychological Association “standards” on qualitative and mixed methods research. In 2018 his book on “Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design” (with Cheryl Poth) won the Textbook and Academic Author’s 2018 McGuffey Longevity Award in the United States. He currently makes his home in Ashiya, Japan and Honolulu, Hawaii.

Product details

- ASIN : B0B5HJGW31

- Publisher : SAGE Publications, Inc; 6th edition (October 24, 2022)

- Publication date : October 24, 2022

- Language : English

- File size : 22105 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 320 pages

- Page numbers source ISBN : 1071817949

- #3 in Social Science Methodology

- #3 in Education Theory Research

- #6 in Social Science Research

About the author

John w. creswell.

John W. Creswell is a Professor of Educational Psychology at Teachers College, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He is affiliated with a graduate program in educational psychology that specializes in quantitative and qualitative methods in education. In this program, he specializes in qualitative and quantitative research designs and methods, multimethod research, and faculty and academic leadership issues in colleges and universities.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2024

The role of champions in the implementation of technology in healthcare services: a systematic mixed studies review

- Sissel Pettersen 1 ,

- Hilde Eide 2 &

- Anita Berg 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 456 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

229 Accesses

Metrics details

Champions play a critical role in implementing technology within healthcare services. While prior studies have explored the presence and characteristics of champions, this review delves into the experiences of healthcare personnel holding champion roles, as well as the experiences of healthcare personnel interacting with them. By synthesizing existing knowledge, this review aims to inform decisions regarding the inclusion of champions as a strategy in technology implementation and guide healthcare personnel in these roles.

A systematic mixed studies review, covering qualitative, quantitative, or mixed designs, was conducted from September 2022 to March 2023. The search spanned Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus, focusing on studies published from 2012 onwards. The review centered on health personnel serving as champions in technology implementation within healthcare services. Quality assessments utilized the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

From 1629 screened studies, 23 were included. The champion role was often examined within the broader context of technology implementation. Limited studies explicitly explored experiences related to the champion role from both champions’ and health personnel’s perspectives. Champions emerged as promoters of technology, supporting its adoption. Success factors included anchoring and selection processes, champions’ expertise, and effective role performance.

The specific tasks and responsibilities assigned to champions differed across reviewed studies, highlighting that the role of champion is a broad one, dependent on the technology being implemented and the site implementing it. Findings indicated a correlation between champion experiences and organizational characteristics. The role’s firm anchoring within the organization is crucial. Limited evidence suggests that volunteering, hiring newly graduated health personnel, and having multiple champions can facilitate technology implementation. Existing studies predominantly focused on client health records and hospitals, emphasizing the need for broader research across healthcare services.

Conclusions

With a clear mandate, dedicated time, and proper training, health personnel in champion roles can significantly contribute professional, technological, and personal competencies to facilitate technology adoption within healthcare services. The review finds that the concept of champions is a broad one and finds varied definitions of the champion role concept. This underscores the importance of describing organizational characteristics, and highlights areas for future research to enhance technology implementation strategies in different healthcare settings with support of a champion.

Peer Review reports

Digital health technologies play a transformative role in healthcare service systems [ 1 , 2 ]. The utilization of technology and digitalization is essential for ensuring patient safety, delivering high quality, cost-effective, and sustainable healthcare services [ 3 , 4 ]. The implementation of technology in healthcare services is a complex process that demands systematic changes in roles, workflows, and service provision [ 5 , 6 ].

The successful implementation of new technologies in healthcare services relies on the adaptability of health professionals [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Champions have been identified as a key factor in the successful implementation of technology among health personnel [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However, they have rarely been studied as an independent strategy; instead, they are often part of a broader array of strategies in implementation studies (e.g., Hudson [ 13 ], Gullslett and Bergmo [ 14 ]). Prior research has frequently focused on determining the presence or absence of champions [ 10 , 12 , 15 ], as well as investigating the characteristics of individuals assuming the champion role (e.g., George et al. [ 16 ], Shea and Belden [ 17 ]).

Recent reviews on champions [ 18 , 19 , 20 ] have studied their effects on adherence to guidelines, implementation of innovations and facilitation of evidence-based practice. While these reviews suggest that having champions yields positive effects, they underscore the importance for studies that offer detailed insights into the champion’s role concerning specific types of interventions.

There is limited understanding of the practical role requirements and the actual experiences of health personnel in performing the champion role in the context of technology implementation within healthcare services. Further, this knowledge is needed to guide future research on the practical, professional, and relational prerequisites for health personnel in this role and for organizations to successfully employ champions as a strategy in technology implementation processes.

This review seeks to synthesize the existing empirical knowledge concerning the experiences of those in the champion role and the perspectives of health personnel involved in technology implementation processes. The aim is to contribute valuable insights that enhance our understanding of practical role requirements, the execution of the champion role, and best practices in this domain.

The term of champions varies [ 10 , 19 ] and there is a lack of explicit conceptualization of the term ‘champion’ in the implementation literature [ 12 , 18 ]. Various terms for individuals with similar roles also exist in the literature, such as implementation leader, opinion leader, facilitator, change agent, superuser and facilitator. For the purpose of this study, we have adopted the terminology utilized in the recent review by Rigby, Redley and Hutchinson [ 21 ] collectively referring to these roles as ‘champions’. This review aims to explore the experiences of health personnel in their role as champions and the experiences of health personnel interacting with them in the implementation of technology in the healthcare services.

Prior review studies on champions in healthcare services have employed various designs [ 10 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. In this review, we utilized a comprehensive mixed studies search to identify relevant empirical studies [ 22 ]. The search was conducted utilizing the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, ensuring a transparent and comprehensive overview that can be replicated or updated by others [ 23 ]. The study protocol is registered in PROSPERO (ID CRD42022335750), providing a more comprehensive description of the methods [ 24 ]. A systematic mixed studies review, examining research using diverse study designs, is well-suited for synthesizing existing knowledge and identifying gaps by harnessing the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods [ 22 ]. Our search encompassed qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods design to capture experiences with the role of champions in technology implementation.

Search strategy and study selection

Search strategy.

The first author, in collaboration with a librarian, developed the search strategy based on initial searches to identify appropriate terms and truncations that align with the eligibility criteria. The search was constructed utilizing a combination of MeSH terms and keywords related to technology, implementation, champion, and attitudes/experiences. Conducted in August/September 2022, the search encompassed four databases: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus, with an updated search conducted in March 2023. The full search strategy for Medline is provided in Appendix 1 . The searches in Embase, CINAHL and Scopus employed the same strategy, with adopted terms and phrases to meet the requirements of each respective database.

Eligibility criteria

We included all empirical studies employing qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods designs that detailed the experiences and/or attitudes of health personnel regarding the champions role in the implementation of technology in healthcare services. Articles in the English language published between 2012 and 2023 were considered. The selected studies involved technology implemented or adapted within healthcare services.

Conference abstract and review articles were excluded from consideration. Articles published prior 2012 were excluded as a result of the rapid development of technology, which could impact the experiences reported. Furthermore, articles involving surgical technology and pre-implementation studies were also excluded, as the focus was on capturing experiences and attitudes from the adoption and daily use of technology. The study also excluded articles that involved champions without clinical health care positions.

Study selection

A total of 1629 studies were identified and downloaded from the selected databases, with Covidence [ 25 ] utilized as a software platform for screening. After removing 624 duplicate records, all team members collaborated to calibrate the screening process utilizing the eligibility criteria on the initial 50 studies. Subsequently, the remaining abstracts were independently screened by two researchers, blinded to each other, to ensure adherence to the eligibility criteria. Studies were included if the title and abstract included the term champion or its synonyms, along with technology in healthcare services, implementation, and health personnel’s experiences or attitudes. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus among all team members. A total of 949 abstracts were excluded for not meeting this inclusion condition. During the initial search, 56 remaining studies underwent full-text screening, resulting in identification of 22 studies qualified for review.

In the updated search covering the period September 2022 to March 2023, 64 new studies were identified. Of these, 18 studies underwent full-text screening, and one study was included in our review. The total number of included studies is 23. The PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1 ) illustrates the process.

Flow Chart illustrating the study selection and screening process

Data extraction

The research team developed an extraction form for the included studies utilizing an Excel spreadsheet. Following data extraction, the information included the Name of Author(s) Year of publication, Country/countries, Title of the article, Setting, Aim, Design, Participants, and Sample size of the studies, Technology utilized in healthcare services, name/title utilized to describe the Champion Role, how the studies were analyzed and details of Attitude/Experience with the role of champion. Data extraction was conducted by SP, and the results were deliberated in a workshop with the other researchers AB, and HE until a consensus was reached. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussions. The data extraction was categorized into three categories: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods, in preparation for quality appraisal.

Quality appraisal

The MMAT [ 26 ] was employed to assess the quality of the 23 included studies. Specifically designed for mixed studies reviews, the MMAT allows for the appraisal of the methodological quality of studies falling into five categories. The studies in our review encompassed qualitative, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods studies. The MMAT begins with two screening questions to confirm the empirical nature of this study. Subsequently, all studies were categorized by type and evaluated utilizing specific criteria based on their research methods, with ratings of ‘Yes,’ ‘No’ or ‘Can’t tell.’ The MMAT discourages overall scores in favor of providing a detailed explanation for each criterion. Consequently, we did not rely on the MMAT’s overall methodical quality scores and continued to include all 23 studies for our review. Two researchers independently scored the studies, and any discrepancies were discussed among all team members until a consensus was reached. The results of the MMAT assessments are provided in Appendix 2 .

Data synthesis

Based on discussions of this material, additional tables were formulated to present a comprehensive overview of the study characteristics categorized by study design, study settings, technology included, and descriptions/characteristics of the champion role. To capture attitudes and experiences associated with the champion role, the findings from the included studies were translated into narrative texts [ 22 ]. Subsequently, the reviewers worked collaboratively to conduct a thematic analysis, drawing inspiration from Braun and Clarke [ 27 ]. Throughout the synthesis process, multiple meetings were conducted to discern and define the emerging themes and subthemes.

The adopting of new technology in healthcare services can be perceived as both an event and a process. According to Iqbal [ 28 ], experience is defined as the knowledge and understanding gained after an event or the process of living through or undergoing an event. This review synthesizes existing empirical knowledge regarding the experiences of occupying the champion role, and the perspectives of health personnel interacting with champions in technology implementation processes.

Study characteristics

The review encompassed a total of 23 studies, and an overview of these studies is presented in Table 1 . Of these, fourteen studies employed a qualitative design, four had quantitative design, and five utilized a mixed method design. The geographical distribution revealed that the majority of studies were conducted in the USA (8), followed by Australia (5), England (4), Canada (2), Norway (2), Ireland (1), and Malaysia (1). In terms of settings, 11 studies were conducted in hospitals, five in primary health care, three in home-based care settings, and four in a mixed settings where two or more settings collaborated. Various technologies were employed across these studies, with client health records (7) and telemedicine (5) being the most frequently utilized. All studies included experiences from champions or health personnel collaborating with champions in their respective healthcare services. Only three studies had the champion role as a main objective [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. The remaining studies described champions as one of the strategies in technology implementation processes, including 10 evaluation studies (including feasibility studies [ 32 , 33 , 34 ] and one cost-benefit study [ 30 ]).

Several studies underscored the importance of champions for successful implementation [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 49 ]. Four studies specifically highlighted champions as a key factor for success [ 34 , 36 , 37 , 43 ], and one study went further to describe champions as the most important factor for successful implementation [ 39 ]. Additionally, one study associated champions with reduced labor cost [ 30 ].

Thin descriptions, yet clear expectations for technology champions’ role and -attributes

The analyses revealed that the concept of champions in studies pertaining to technology implementation in healthcare services varies, primarily as a result of the diversity of terms utilized to describe the role combined with short role descriptions. Nevertheless, the studies indicated clear expectations for the champion’s role and associated attributes.

The term champion

The term champion was expressed in 20 different forms across the 23 studies included in our review. Three studies utilized multiple terms within the same study [ 32 , 47 , 48 ] and 15 different authors [ 29 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 50 ] employed the term with different compositions (Table 1 ). Furthermore, four authors utilized the term Super user [ 30 , 31 , 49 , 51 ], while four authors employed the terms Facilitator [ 38 ], IT clinician [ 48 ], Leader [ 45 ], and Manager [ 34 ], each in combination with more specific terms (such as local opinion leaders, IT nurse, or practice manager).

Most studies associated champion roles with specific professions. In seven studies, the professional title was explicitly linked to the concept of champions, such as physician champions or clinical nurse champions, or through the strategic selection of specific professions [ 29 , 33 , 36 , 40 , 43 , 47 , 50 ]. Additionally, some studies did not specify professions, but utilized terms like clinicians [ 45 ] or health professionals [ 41 ].

All included articles portray the champion’s role as facilitating implementation and daily use of technology among staff. In four studies, the champion’s role was not elaborated beyond indicating that the individual holding the role is confident with an interest in technology [ 35 , 41 , 42 , 44 ]. The champion’s role was explicitly examined in six studies [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 46 , 50 ]. Furthermore, seven studies described the champion in both the methods and results [ 32 , 36 , 38 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 51 ]. In ten of the studies, champions were solely mentioned in the results [ 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ].

Eight studies provided a specific description or definition of the champion [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 38 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. The champion’s role was described as involving training in the specific technology, being an expert on the technology, providing support and assisting peers when needed. In some instance, the champion had a role in leading the implementation [ 50 ], while in other situations, the champion operated as a mediator [ 48 ].

The champions tasks

In the included studies, the champion role encompassed two interrelated facilitators tasks: promoting the technology and supporting others in adopting the technology in their daily practice. Promoting the technology involved encouraging staff adaptation [ 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 40 , 41 , 49 ], generally described as being enthusiastic about the technology [ 32 , 35 , 37 , 41 , 48 ], influencing the attitudes and beliefs of colleagues [ 42 , 45 ] and legitimizing the introduction of the technology [ 42 , 46 , 48 ]. Supporting others in technology adaption involved training and teaching [ 31 , 35 , 38 , 40 , 51 ], as well as providing technical support [ 30 , 31 , 39 , 43 , 49 ] and social support [ 49 ]. Only four studies reported that the champions received their own training to enable them able to support their colleagues [ 30 , 31 , 39 , 48 ]. Furthermore, eight studies [ 32 , 34 , 38 , 40 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ], specified that the champion role included leadership and management responsibilities, mentioning tasks such as planning, organizing, coordinating, and mediating technology adaption without providing further details.

Desirable champion attributes

To effectively fulfill their role, champions should ideally possess clinical expertise and experience [ 29 , 35 , 38 , 40 , 48 ], stay professionally updated [ 37 , 48 ], and possess knowledge of the organization and workflows [ 29 , 34 , 46 ]. They should have the ability to understand and communicate effectively with healthcare personnel [ 31 , 32 , 46 , 49 ] and be proficient in IT language [ 51 ]. Moreover, champions should demonstrate a general technological interest and competence, and competence, along with specific knowledge of the technology to be implemented [ 32 , 37 , 49 ]. It is also emphasized that they should command formal and/or informal respect and authority in the organization [ 36 , 45 ], be accessible to others [ 39 , 43 ], possess leadership qualities [ 34 , 37 , 38 , 46 ], and understand and balance the needs of stakeholders [ 43 ]. Lastly, the champions should be enthusiastic promoters of the technology, engaging and supporting others [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 49 ], while also effectively coping with cultural resistance to change [ 31 , 46 ].

Anchoring and recruiting for the champion role

The champions were organized differently within services, holding various positions in the organizations, and being recruited for the role in different ways.

Anchoring the champion role

The champion’s role is primarily anchored at two levels: the management level and/or the clinical level, with two studies having champions at both levels [ 34 , 49 ]. Those working with the management actively participated in the planning of the technology implementation [ 29 , 36 , 40 , 41 , 45 ]. Serving as advisors to management, they leveraged their clinical knowledge to guide the implementation in alignment with the necessities and possibilities of daily work routines in the clinics. Champions in this capacity experienced having a clear formal position that enabled them to fulfil their role effectively [ 29 , 40 ]. Moreover, these champions served as bridge builders between the management and department levels [ 36 , 45 ], ensuring the necessary flow of information in both directions.

Champions anchored at the clinic level played a pivotal role in the practical implementation and facilitation of the daily use of technology [ 31 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 43 , 48 , 51 ]. Additionally, these champions actively participated in meetings with senior management to discuss the technology and its implementation in the clinic. This position conferred potential influence over health personnel [ 33 , 35 ]. Champions at the clinic level facilitated collaboration between employees, management, and suppliers [ 48 ]. Fontaine et al. [ 36 ] identified respected champions at the clinical level, possessing authority and formal support from all leadership levels, as the most important factor for success.

Only one study reported that the champions received additional compensation for their role [ 36 ], while another study mentioned champions having dedicated time to fulfil their role [ 46 ]. The remaining studies did not provide this information.

Recruiting for the role as champion

Several studies have reported different experiences regarding the management’s selection of champions. A study highlighted the distinctions between a volunteered role and an appointed champion’s role [ 31 ]. Some studies underscored that appointed champions were chosen based on technological expertise and skills [ 41 , 48 , 51 ]. Moreover, the selection criteria included champions’ interest in the specific technology [ 42 ] or experiential skills [ 40 ]. The remaining studies did not provide this information.

While the champion role was most frequently held by health personnel with clinical experience, one study deviated by hiring 150 newly qualified nurses as champions [ 30 ] for a large-scale implementation of an Electronic Health Record (EHR). Opting for clinical novices assisted in reducing implementation costs, as it avoided disrupting daily tasks and interfering with daily operations. According to Bullard [ 30 ], these super-user nurses became highly sought after post-implementation as a result of their technological confidence and competence.

Reported experiences of champions and health personnel

Drawing from the experiences of both champions and health personnel, it is essential for a champion to possess a combination of general knowledge and specific champion characteristics. Furthermore, champions are required to collaborate with individuals both within and outside the organization. The subsequent paragraphs delineate these experiences, categorizing them into four subsets: champions’ contextual knowledge and expertise, preferred performance of the champion role, recognizing that a champion alone is insufficient, and distinguishing between reactive and proactive champions.

Champions’ contextual knowledge and know-how

Health personnel with experience interacting with champions emphasized that a champion must be familiar with the department and its daily work routines [ 35 , 40 ]. Knowledge of the department’s daily routines made it easier for champions to facilitate the adaptation of technology. However, there was a divergence of opinions on whether champions were required to possess extensive clinical experience to fulfil their role. In most studies, having an experienced and competent clinician as a champion instilled a sense of confidence among health personnel. Conversely, Bullard’s study [ 30 ] exhibited that health personnel were satisfied with newly qualified nurses in the role of champion, despite their initial skepticism.

It is a generally expected that champions should possess technological knowledge beyond that of other health professionals [ 37 , 41 ]. Some health personnel perceived the champions as uncritical promoters of technology, with the impression that health personnel were being compelled to utilize technology [ 46 ]. Champions could also overestimate the readiness of health personnel to implement a technology, especially during the early phases of the implementation process [ 32 ]. Regardless of whether the champion is at the management level or the clinic level, champions themselves have acknowledged the importance of providing time and space for innovation. Moreover, the recruitment of champions should span all levels of the organization [ 34 , 46 ]. Furthermore, champions must be familiar with daily work routines, work tools, and work surfaces [ 38 , 40 , 43 ].

Preferable performance of the champion role

The studies identified several preferable characteristics of successful champions. Health personnel favored champions utilizing positive words when discussing technology and exhibiting positive attitudes while facilitating and adapting it [ 33 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 46 ]. Additionally, champions who were enthusiastic and engaging were considered good role models for the adoption of technology. Successful champions were perceived as knowledgeable and adept problem solvers who motivated and supported health personnel [ 41 , 43 , 44 , 48 ]. They were also valued for being available and responding promptly when contacted [ 42 ]. Health professionals noted that champions perceived as competent garnered respect in the organization [ 40 ]. Moreover, some health personnel felt that some certain champions wielded a greater influence based on how they encouraged the use of the system [ 48 ]. It was also emphasized that health personnel needed to feel it was safe to provide feedback to champions, especially when encountering difficulties or uncertainties [ 49 ].

A champion is not enough

The role of champions proved to be more demanding than expected [ 29 , 31 , 38 ], involving tasks such as handling an overwhelming number of questions or actively participating in the installation process to ensure the technology functions effectively in the department [ 29 ]. Regardless of the organizational characteristics or the champion’s profile, appointing the champion as a “solo implementation agent” is deemed unsuitable. If the organization begins with one champion, it is recommended that this individual promptly recruits others into the role [ 42 ].

Health personnel, reliant on champions’ expertise, found it beneficial to have champions in all departments, and these champions had to be actively engaged in day-to-day operations [ 31 , 33 , 34 , 37 ]. Champions themselves also noted that health personnel increased their technological expertise through their role as champions in the department [ 39 ].

Furthermore, the successful implementation of technology requires the collaboration of various professions and support functions, a task that cannot be solely addressed by a champion [ 29 , 43 , 48 ]. In Orchard et. al.‘s study [ 34 ], champions explicitly emphasized the necessity of support from other personnel in the organization, such as those responsible for the technical aspects and archiving routines, to provide essential assistance.

According to health personnel, the role of champions is vulnerable in case they become sick or leave their position [ 42 , 51 ]. In some of the included studies, only one or a few hold the position of champion [ 37 , 38 , 42 , 48 ]. Two studies observed that their implementations were not completed because champions left or reassigned for various reasons [ 32 , 51 ]. The health professionals in the study by Owens and Charles [ 32 ] expressed that champions must be replaced in such cases. Further, the study of Olsen et al., 2021 [ 42 ] highlights the need for quicky building a champion network within the organization.

Reactive and proactive champions

Health personnel and champions alike noted that champions played both a reactive and proactive role. The proactive role entailed facilitating measures such as training and coordination [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 48 , 49 ] as initiatives to generate enthusiasm for the technology [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 49 ]. On the other hand, the reactive role entailed hands-on support and troubleshooting [ 30 , 31 , 39 , 43 , 49 ].

In a study presenting experiences from both health personnel and champions, Yuan et al. [ 31 ] found that personnel observed differences in the assistance provided by appointed and self-chosen champions. Appointed champions demonstrated the technology, answered questions from health personnel, but quickly lost patience and track of employees who had received training [ 31 ]. Health personnel perceived that self-chosen champions were proactive and well-prepared to facilitate the utilization of technology, communicating with the staff as a group and being more competent in utilizing the technology in daily practice [ 31 ]. Health personnel also noted that volunteer champions were supportive, positive, and proactive in promoting the technology, whereas appointed champions acted on request and had a more reactive approach [ 31 ].

This review underscores the breadth of the concept of champion and the significant variation in the champion’s role in implementation of technology in healthcare services. This finding supports the results from previous reviews [ 10 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. The majority of studies meeting our inclusion criteria did not specifically focus on the experiences of champions and health personnel regarding the champion role, with the exception of studies by Bullard [ 30 ], Gui et al. [ 29 ], Helmer-Smith et al. [ 33 ], Hogan-Murphy et al. [ 46 ], Rea et al. [ 50 ], and Yuan et al. [ 31 ].

The 23 studies encompassed in this review utilized 20 different terms for the champion role. In most studies, the champion’s role was briefly described in terms of the duties it entailed or should entail. This may be linked to the fact that the role of champions was not the primary focus of the study, but rather one of the strategies in the implementation process being investigated. This result reinforces the conclusions drawn by Miech et al. [ 10 ] and Shea et al. [ 12 ] regarding the lack of united understandings of the concept. Furthermore, in Santos et al.‘s [ 19 ] review, champions were only operationalized through presence or absence in 71.4% of the included studies. However, our review finds that there is a consistent and shared understanding that champions should promote and support technology implementation.

Several studies advocate for champions as an effective and recommended strategy for implementing technology [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 46 ]. However, we identified that few studies exclusively explore health personnel`s experiences within the champion role when implementing technology in healthcare services.

This suggests a general lack of information essential for understanding the pros, cons, and prerequisites for champions as a strategy within this field of knowledge. However, this review identifies, on a general basis, the types of support and structures required for champions to perform their role successfully from the perspectives of health personnel, contributing to Shea’s conceptual model [ 12 ].

Regarding the organization of the role, this review identified champions holding both formal appointed and informal roles, working in management or clinical settings, being recruited for their clinical and/or technological expertise, and either volunteering or being hired with specific benefits for the role. Regardless of these variations, anchoring the role is crucial for both the individuals holding the champion role and the health personnel interacting with them. Anchoring, in this context, is associated with the clarity of the role’s content and a match between role expectations and opportunities for fulfilment. Furthermore, the role should be valued by the management, preferably through dedicated time and/or salary support [ 34 , 36 , 46 ]. Additionally, our findings indicate that relying on a “solo champion” is vulnerable to issues such as illness, turnover, excessive workload, and individual champion performance [ 32 , 37 ]. Based on these insights, it appears preferable to appoint multiple champions, with roles at both management and clinical levels [ 33 ].

Some studies have explored the selection of champions and its impact on role performance, revealing diverse experiences [ 30 , 31 ]. Notably, Bullard [ 30 ], stands out for emphasizing long clinical experience, and hiring newly trained nurses as superusers to facilitate the use of electronic health records. Despite facing initial reluctance, these newly trained nurses gradually succeeded in their roles. This underscores the importance of considering contextual factors in the champion selection [ 30 , 52 ]. In Bullard’s study [ 30 ], the collaboration between newly trained nurses as digital natives and clinical experienced health personnel proved beneficial, highlighting the need to align champion selection with the organization’s needs based on personal characteristics. This finding aligns with Melkas et al.‘s [ 9 ] argument that implementing technology requires a deeper understanding of users, access to contextual know-how, and health personnel’s tacit knowledge.

To meet role expectations and effectively leverage their professional and technological expertise, champions should embody personal qualities such as the ability to engage others, take a leadership role, be accessible, supportive, and communicate clearly. These qualities align with the key attributes for change in healthcare champions described by Bonawitz et al. [ 15 ]. These attributes include influence, ownership, physical presence, persuasiveness, grit, and a participative leadership style (p.5). These findings suggest that the active performance of the role, beyond mere presence, is crucial for champions to be a successful strategy in technology implementation. Moreover, the recruitment process is not inconsequential. Identifying the right person for the role and providing them with adequate training, organizational support, and dedicated time to fulfill their responsibilities emerge as an important factor based on the insights from champions and health personnel.

Strengths and limitations

While this study benefits from identifying various terms associated with the role of champions, it acknowledges the possibility of missing some studies as a result of diverse descriptions of the role. Nonetheless, a notable strength of the study lies in its specific focus on the health personnel’s experiences in holding the champion role and the broader experiences of health personnel concerning champions in technology implementation within healthcare services. This approach contributes valuable insights into the characteristics of experiences and attitudes toward the role of champions in implementing technology. Lastly, the study emphasizes the relationship between the experiences with the champion role and the organizational setting’s characteristics.

The champion role was frequently inadequately defined [ 30 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 51 ], aligning with previous reviews [ 17 , 19 , 21 ]. As indicated by van Laere and Aggestam [ 52 ], this lack of clarity complicates the identification and comparison of champions across studies. Studies that lacking a distinct definition of the champion’s role were consequently excluded. Only studies written in English were included, introducing the possibility of overlooking relevant studies based on our chosen terms for identifying the champion’s role. Most of the included studies focused on technology implementation in a general context, with champions being just one of several measures. This approach resulted in scant descriptions, as champions were often discussed in the results, discussion, or implications sections rather than being the central focus of the research.

As highlighted by Hall et al. [ 18 ]., methodological issues and inadequate reporting in studies of the champion role create challenges for conducting high-quality reviews, introducing uncertainty around the findings. We have adopted a similar approach to Santos et al. [ 19 ], including all studies even when some issues were identified during the quality assessment. Our review shares the same limitations as previous review by Santos et al. [ 19 ] on the champion role.

Practical implications, policy, and future research

The findings emphasize the significance of the relationship between experiences with the champion role and characteristics of organizational settings as crucial factors for success in the champion role. Clear anchoring of the role within the organization is vital and may impact routines, workflows, staffing, and budgets. Despite limited evidence on the experience of the champion’s role, volunteering, hiring newly graduated health personnel, and appointing more than one champion are identified as facilitators of technology implementation. This study underscores the need for future empirical research including clear descriptions of the champion roles, details on study settings and the technologies to be adopted. This will enable the determination of outcomes and success factors in holding champions in technology implementation processes, transferability of knowledge between contexts and technologies as well as enhance the comparability of studies. Furthermore, there is a need for studies to explore experiences with the champion role, preferably from the perspective of multiple stakeholders, as well as focus on the champion role within various healthcare settings.

This study emphasizes that champions can hold significant positions when provided with a clear mandate, dedicated time, and training, contributing their professional, technological, and personal competencies to expedite technology adoption within services. It appears to be an advantage if the health personnel volunteer or apply for the role to facilitate engaged and proactive champions. The implementation of technology in healthcare services demands efforts from the entire service, and the experiences highlighted in this review exhibits that champions can play an important role. Consequently, empirical studies dedicated to the champion role, employing robust designs based current knowledge, are still needed to provide solid understanding of how champions can be a successful initiative when implementing technology in healthcare services.

Data availability

This review relies exclusively on previously published studies. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its supplementary files: Description and characteristics of included studies in Table 1 , Study characteristics. The search strategy is provided in Appendix 1 , and the Critical Appraisal Summary of included studies utilizing MMAT is presented in Appendix 2 .

Abbreviations

Electronic Health Record

Implementation Outcomes Framework

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematics and Meta-Analysis

Meskó B, Drobni Z, Bényei É, Gergely B, Győrffy Z. Digital health is a cultural transformation of traditional healthcare. mHealth. 2017;3:38. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2017.08.07 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pérez Sust P, Solans O, Fajardo JC, Medina Peralta M, Rodenas P, Gabaldà J, et al. Turning the crisis into an opportunity: Digital health strategies deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e19106. https://doi.org/10.2196/19106 .

Alotaibi YK, Federico F. The impact of health information technology on patient safety. Saudi MedJ. 2017;38:117380. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.12.20631 .

Article Google Scholar

Kuoppamäki S. The application and deployment of welfare technology in Swedish municipal care: a qualitative study of procurement practices among municipal actors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:918. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06944-w .

Kraus S, Schiavone F, Pluzhnikova A, Invernizzi AC. Digital transformation in healthcare: analyzing the current state-of-research. J Bus Res. 2021;123:557–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.030 .

Frennert S. Approaches to welfare technology in municipal eldercare. JTechnolHum. 2020;38:22646. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2020.1747043 .

Konttila J, Siira H, Kyngäs H, Lahtinen M, Elo S, Kääriäinen M, et al. Healthcare professionals’ competence in digitalisation: a systematic review. Clin Nurs. 2019;28:74561. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14710 .

Jacob C, Sanchez-Vazquez A, Ivory C. Social, organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: systematic literature review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8:e15935. https://doi.org/10.2196/15935 .

Melkas H, Hennala L, Pekkarinen S, Kyrki V. Impacts of robot implementation on care personnel and clients in elderly-care institutions. Int J Med Inf. 2020;134:104041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.104041 .

Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118773261 .

Foong HF, Kyaw BM, Upton Z, Tudor Car L. Facilitators and barriers of using digital technology for the management of diabetic foot ulcers: a qualitative systematic review. Int Wound J. 2020;17:126681. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13396 .

Shea CM. A conceptual model to guide research on the activities and effects of innovation champions. Implement Res Pract. 2021;2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489521990443 .

Hudson D. Physician engagement strategies in health information system implementations. Healthc Manage Forum. 2023;36:86–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/08404704221131921 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gullslett MK, Strand Bergmo T. Implementation of E-prescription for multidose dispensed drugs: qualitative study of general practitioners’’ experiences. JMIR HumFactors. 2022;9:e27431. https://doi.org/10.2196/27431 .

Bonawitz K, Wetmore M, Heisler M, Dalton VK, Damschroder LJ, Forman J, et al. Champions in context: which attributes matter for change efforts in healthcare? Implement Sci. 2020;15:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01024-9 .

George ER, Sabin LL, Elliott PA, Wolff JA, Osani MC, McSwiggan Hong J, et al. Examining health care champions: a mixed-methods study exploring self and peer perspectives of champions. Implement Res Pract. 2022;3. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895221077880 .

Shea CM, Belden CM. What is the extent of research on the characteristics, behaviors, and impacts of health information technology champions? A scoping review. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2016;16:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0240-4 .

Hall AM, Flodgren GM, Richmond HL, Welsh S, Thompson JY, Furlong BM, Sherriff A. Champions for improved adherence to guidelines in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):85–85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00185-y .

Santos WJ, Graham ID, Lalonde M, Demery Varin M, Squires JE. The effectiveness of champions in implementing innovations in health care: a systematic review. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3(1):1–80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00315-0 .

Wood K, Giannopoulos V, Louie E, Baillie A, Uribe G, Lee KS, Haber PS, Morley KC. The role of clinical champions in facilitating the use of evidence-based practice in drug and alcohol and mental health settings: a systematic review. Implement Res Pract. 2020;1:2633489520959072–2633489520959072. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489520959072 .

Rigby K, Redley B, Hutchinson AM. Change agent’s role in facilitating use of technology in residential aged care: a systematic review. Int J Med Informatics. 2023;105216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105216 .

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:29–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Pettersen S, Berg A, Eide H. Experiences and attitudes to the role of champions in implementation of technology in health services. A systematic review. PROSPERO. 2022. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022335750 . Accessed [15 Feb 2023].

Covidence. Better Syst Rev Manag. https://www.covidence.org/ . 2023;26.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The mixed methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34:285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221 .

Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. 1st ed. SAGE; 2022.

Iqbal MP, Manias E, Mimmo L, Mears S, Jack B, Hay L, Harrison R. Clinicians’ experience of providing care: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05812-3 .

Gui X, Chen Y, Zhou X, Reynolds TL, Zheng K, Hanauer DA. Physician champions’ perspectives and practices on electronic health records implementation: challenges and strategies. JAMIA open. 2020;3:5361. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz051 .

Bullard KL. Cost effective staffing for an EHR implementation. Nurs Econ. 2016;34:726.

Google Scholar

Yuan CT, Bradley EH, Nembhard IM. A mixed methods study of how clinician ‘super users’ influence others during the implementation of electronic health records. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2015;15:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-015-0154-6 .

Owens C, Charles N. Implementation of a text-messaging intervention for adolescents who self-harm (TeenTEXT): a feasibility study using normalisation process theory. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2016;10:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0101-z .

Helmer-Smith M, Fung C, Afkham A, Crowe L, Gazarin M, Keely E, et al. The feasibility of using electronic consultation in long-term care homes. JAm Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:11661170e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.003 .

Orchard J, Lowres N, Freedman SB, Ladak L, Lee W, Zwar N, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation during influenza vaccinations by primary care nurses using a smartphone electrocardiograph (iECG): a feasibility study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:13–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316670255 .

Bee P, Lovell K, Airnes Z, Pruszynska A. Embedding telephone therapy in statutory mental health services: a qualitative, theory-driven analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0761-5 .

Fontaine P, Whitebird R, Solberg LI, Tillema J, Smithson A, Crabtree BF. Minnesota’s early experience with medical home implementation: viewpoints from the front lines. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):899–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3136-y .

Kolltveit B-CH, Gjengedal E, Graue M, Iversen MM, Thorne S, Kirkevold M. Conditions for success in introducing telemedicine in diabetes foot care: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Nurs. 2017;16:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0201-y .

Salbach NM, McDonald A, MacKay-Lyons M, Bulmer B, Howe JA, Bayley MT, et al. Experiences of physical therapists and professional leaders with implementing a toolkit to advance walking assessment poststroke: a realist evaluation. Phys Ther. 2021;101:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab232 .

Schwarz M, Coccetti A, Draheim M, Gordon G. Perceptions of allied health staff of the implementation of an integrated electronic medical record across regional and metropolitan settings. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44:965–72. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH19024 .

Stewart J, McCorry N, Reid H, Hart N, Kee F. Implementation of remote asthma consulting in general practice in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: an evaluation using extended normalisation process theory. BJGP Open. 2022;6:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0189 .

Bennett-Levy J, Singer J, DuBois S, Hyde K. Translating mental health into practice: what are the barriers and enablers to e-mental health implementation by aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals? JMed. Internet Res. 2017;19:e1. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6269 .

Olsen J, Peterson S, Stevens A. Implementing electronic health record-based National Diabetes Prevention Program referrals in a rural county. Public Health Nurs (Boston Mass). 2021;38(3):464–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12860 .

Yang L, Brown-Johnson CG, Miller-Kuhlmann R, Kling SMR, Saliba-Gustafsson EA, Shaw JG, et al. Accelerated launch of video visits in ambulatory neurology during COVID-19: key lessons from the Stanford experience. Neurology. 2020;95:305–11. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010015 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Buckingham SA, Sein K, Anil K, Demain S, Gunn H, Jones RB, et al. Telerehabilitation for physical disabilities and movement impairment: a service evaluation in South West England. JEval Clin Pract. 2022;28:108495. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13689 .

Chung OS, Robinson T, Johnson AM, Dowling NL, Ng CH, Yücel M, et al. Implementation of therapeutic virtual reality into psychiatric care: clinicians’ and service managers’’ perspectives. Front Psychiatry. 2022;12:791123. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.791123 .

Hogan-Murphy D, Stewart D, Tonna A, Strath A, Cunningham S. Use of normalization process theory to explore key stakeholders’ perceptions of the facilitators and barriers to implementing electronic systems for medicines management in hospital settings. Res SocialAdm Pharm. 2021;17:398405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.005 .

Moss SR, Martinez KA, Nathan C, Pfoh ER, Rothberg MB. Physicians’ views on utilization of an electronic health record-embedded calculator to assess risk for venous thromboembolism among medical inpatients: a qualitative study. TH Open. 2022;6:e33–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1742227 .

Yusof MM. A case study evaluation of a critical Care Information System adoption using the socio-technical and fit approach. Int J Med Inf. 2015;84:486–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.03.001 .

Dugstad J, Sundling V, Nilsen ER, Eide H. Nursing staff’s evaluation of facilitators and barriers during implementation of wireless nurse call systems in residential care facilities. A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4998-9 .

Rea K, Le-Jenkins U, Rutledge C. A technology intervention for nurses engaged in preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Comput Inf Nurs. 2018;36:305–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000429 .

Bail K, Davey R, Currie M, Gibson J, Merrick E, Redley B. Implementation pilot of a novel electronic bedside nursing chart: a mixed-methods case study. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44:672–6. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH18231 .

van Laere J, Aggestam L. Understanding champion behaviour in a health-care information system development project – how multiple champions and champion behaviours build a coherent whole. Eur J Inf Syst. 2016;25:47–63. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2015.5 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the librarian Malin E. Norman, at Nord university, for her assistance in the development of the search, as well as guidance regarding the scientific databases.

This study is a part of a PhD project undertaken by the first author, SP, and funded by Nord University, Norway. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, as well as not-for-profit sectors.

Open access funding provided by Nord University

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Nursing and Health Sciences, Nord university, P.O. Box 474, N-7801, Namsos, Norway

Sissel Pettersen & Anita Berg

Centre for Health and Technology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of South-Eastern Norway, PO Box 7053, N-3007, Drammen, Norway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The first author/SP has been the project manager and was mainly responsible for all phases of the study. The second and third authors HE and AB have contributed to screening, quality assessment, analysis and discussion of findings. Drafting of the final manuscript has been a collaboration between the first/SP and third athor/AB. The final manuscript has been approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sissel Pettersen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This review does not involve the processing of personal data, and given the nature of this study, formal consent is not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pettersen, S., Eide, H. & Berg, A. The role of champions in the implementation of technology in healthcare services: a systematic mixed studies review. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 456 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10867-7

Download citation

Received : 19 June 2023

Accepted : 14 March 2024

Published : 11 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10867-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Technology implementation

- Healthcare personnel

- Healthcare services

- Mixed methods

- Organizational characteristics

- Technology adoption

- Role definitions

- Healthcare settings

- Systematic review

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 16 April 2024

‘Enough is enough’: a mixed methods study on the key factors driving UK NHS nurses’ decision to strike

- Daniel Sanfey 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 247 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

61 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

The UK National Health Service (NHS) is one of the largest employers in the world and employs around 360,000 registered nurses. Following a protracted pay dispute in December 2022 NHS nurses engaged in industrial action resulting in the largest nurse strikes in the 74-year history of the NHS. Initially it appeared these strikes were a direct consequence of pay disputes but evidence suggests that the situation was more complex. This study aimed to explore what the key factors were in driving UK NHS nurses’ decision to strike.

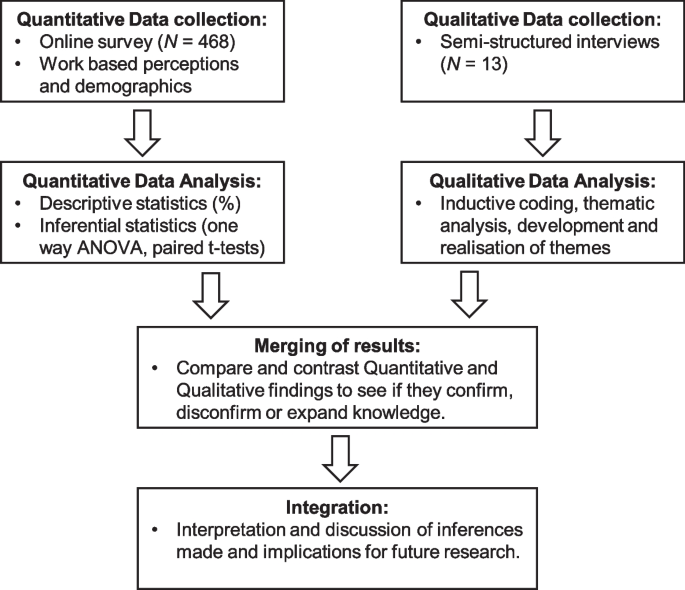

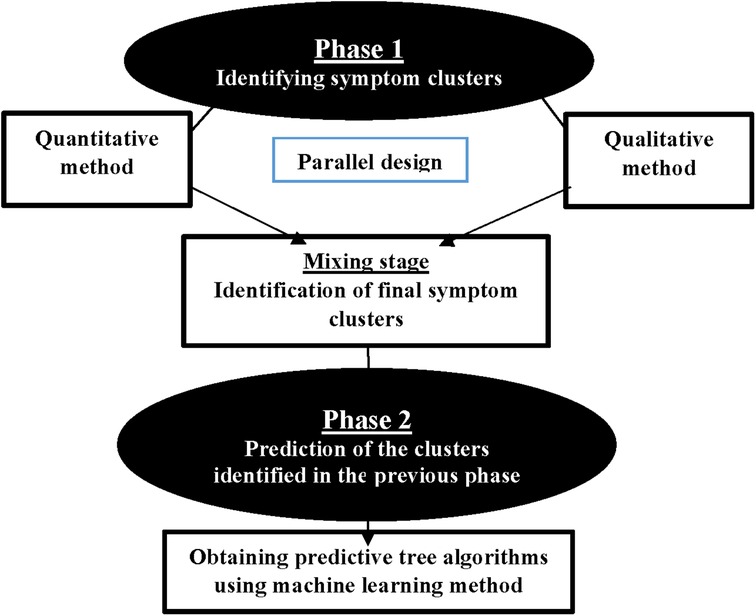

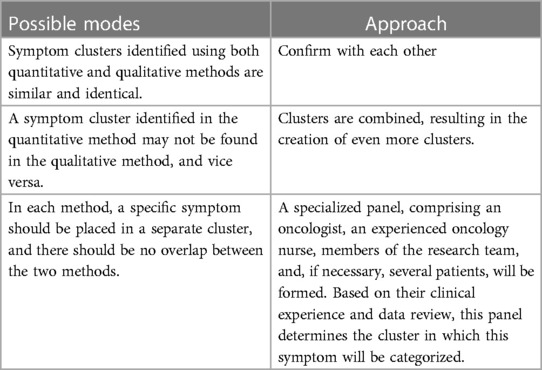

A convergent parallel mixed methods design was used. The study was conducted throughout the UK and involved participants who were nurses working for the NHS who voted in favour of strike action. Data collection involved the use of an online survey completed by 468 nurses and 13 semi-structured interviews. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for quantitative data analysis and a process of inductive thematic analysis for the qualitative data. The quantitative and qualitative data were analysed separately and then integrated to generate mixed methods inferences.

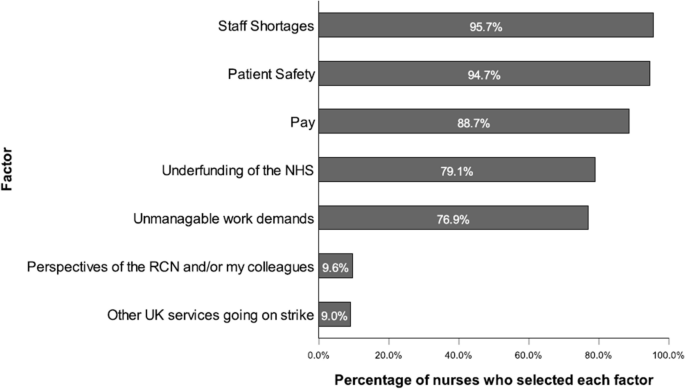

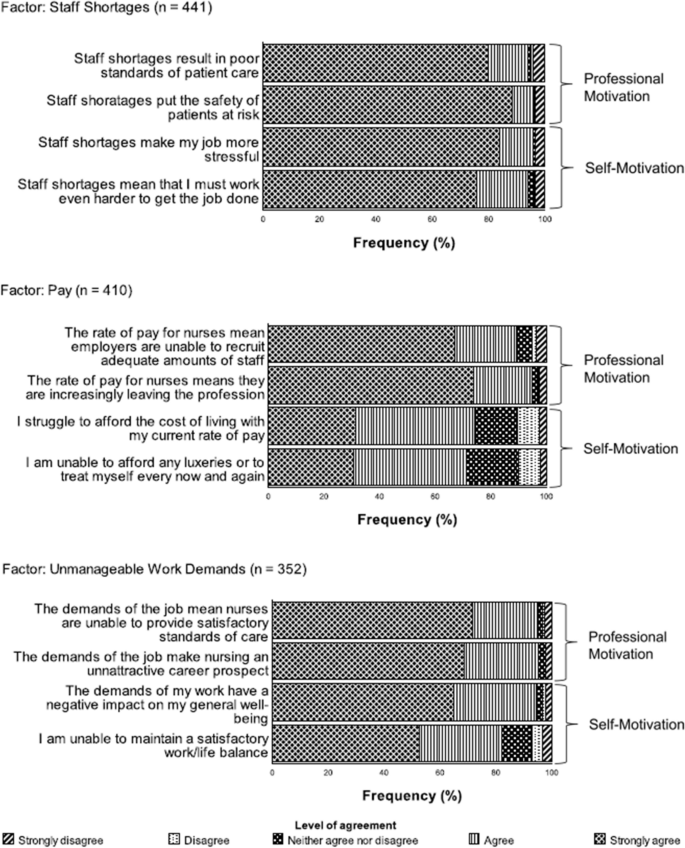

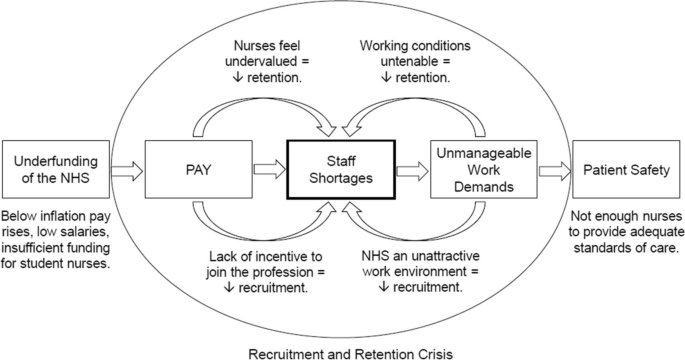

The quantitative findings showed that patient safety, followed by staff shortages, pay, and unmanageable work demands were the most important factors encouraging nurses’ decision to strike. The qualitative findings served to further the understanding of these factors particularly in relation to participants’ perception of the NHS and the consequences of inadequate pay and staff shortages. Three overarching and overlapping themes represented the qualitative findings: Save our NHS, Money talks, and It’s untenable. Integration of the findings showed a high level of concordance between the two data sets and suggest that the factors involved are interconnected and inextricably linked.

Conclusions

The UK NHS is a challenging and demanding work environment in which the well-being of its patients is dependent on the well-being of those who care for them. Concerns relating to patient welfare, the nursing profession and the NHS played a large part in driving UK NHS nurses’ decision to strike. In order to address these concerns a focus on recruitment and retention of nurses in the NHS is needed.

Peer Review reports

The United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS) is the seventh largest employer in the world [ 1 ] providing public health services for a population of around 67 million people [ 2 ]. Of the 1.4 million staff working for the NHS approximately a quarter of these are registered nurses [ 3 ]. Nurses are the backbone of the NHS providing hospital and community services and are often patients’ first and last point of contact when accessing care.

Nurses working for the NHS are paid according to a pre agreed pay and grading system decided upon by the UK Government with recommendations from an independent NHS pay review body. Research has shown that when taking inflation into account the average pay of NHS nurses has fallen in real terms by 8% between 2010/11 and 2021/22 [ 4 ], with the figure estimated at closer to 20% for more experienced nurses [ 5 ].

The Royal College of Nurses (RCN) is the largest nursing union in the world and represents around 405,000 registered nurses working in the UK [ 6 ]. Following a protracted pay dispute with the UK government, in October 2022 the RCN balloted its members working for the NHS on whether to take industrial action in the form of strikes. Despite the high threshold for success, with all ballots needing to be conducted by post and a 50% turnout and 40% vote in favour, the ballot was conclusive. NHS nurses voted in favour of strike action in the majority of NHS Trusts throughout the UK. Footnote 1 In December 2022, for the first time in the RCN’s 106-year history their members engaged in strike action. The largest nursing strike in the 74-year history of the NHS.

On the surface it appears clear. NHS nurses were striking to secure better pay. This is supported by the most recent NHS staff survey [ 7 ] which found that only 25.6% of staff were satisfied with their level of pay. However, the staff survey also highlighted a number of other factors that indicate a high level of discontent, portraying the NHS as a stressful, demanding and unsatisfactory work environment. Furthermore, increasing numbers of nurses are leaving the profession due to health reasons, burnout and exhaustion [ 8 ], with additional nurses voicing their intent to leave because of high workload pressures and feeling undervalued [ 9 ]. This leads to the question: what are the key factors that have driven UK NHS nurses’ decision to strike?

Answering this research question is particularly pertinent at this time as the UK NHS is currently experiencing some of the greatest pressures in its history [ 10 ]. Waiting times are at an all-time high and record numbers of patients are waiting for treatment [ 11 ]. Not only are nurses engaging in strike action but also a plethora of other professions within the NHS including doctors, radiologists and physiotherapists; all of which only serves to exacerbate what is widely considered as an NHS in crisis [ 12 ]. At a time of widespread industrial action throughout the UK in which 2022 saw the highest number of working days lost to strikes for more than 30 years [ 13 ], determining the key factors driving UK NHS nurses’ decision to strike may serve to inform those concerned with prolonged and future industrial action, not just within the nursing profession and the NHS, but also the wider UK workforce.

Literature review

A strike has been defined as ‘A temporary stoppage of work by a group of employees in order to express a grievance or enforce a demand’ (p.3) [ 14 ], Hyman [ 15 ] highlights that it is predominantly a calculated act and that the complete stoppage of work and its temporary and collective nature distinguish it from other forms of work-based protest.

Nursing strikes are a global phenomenon with incidences occurring in a diverse range of countries including America, Japan, Kenya, India, Australia and throughout Europe. In the UK nurses have a rich history of protest, but the incidences of strikes within the profession are few and far between. A limited number of empirical studies exist identifying factors that have driven nurses to go on strike. These include quantitative [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], qualitative [ 19 , 20 , 21 ], and mixed methods designs [ 22 , 23 ]. Within these, issues relating to pay and working conditions predominate, but other factors such as intimidation from unions, failures of healthcare systems and addressing public perceptions of nurses were also found. What is notable is that none of these studies focus solely on factors driving nurses’ decision to strike, instead collecting data on a broad range of topics. This diverse approach may explain to some extent why they fail to facilitate a thorough understanding of the key factors driving nurses’ decision to strike. At present, it appears that there are no existing empirical studies focusing on nurse strikes within the UK, signifying a gap in the literature.

In addition to existing empirical studies there is a wide body of literature in the form of retrospective accounts that document and provide theoretical interpretations of individual and country specific nurse strikes [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. By depicting the nurse strike within a historical, political, and professional context these accounts help to further illuminate the phenomenon and facilitate a much richer and deeper understanding. With this, we begin to appreciate the nurse strike as distinct from those within industrialised settings and as much a form of advocacy as that of self-preservation.

For any strike there are consequences. Whether they be for employers, workers, service users, the government, or for society at large. Within the healthcare environment there are concerns that a strike may have the additional consequence of compromising patient care. This has led some to denounce strikes by nurses citing them as immoral, unjustifiable [ 31 ] and wholly inappropriate [ 32 ]. Yet, it has been argued that such a stance fails to see the bigger picture and puts too much emphasis on the nurse/patient relationship [ 33 ].

Healthcare provision is a collective endeavour and whilst nurses have a professional responsibility to prioritise patient care and put the safety and wellbeing of those requiring care at the forefront of all they do [ 34 , 35 ]; governments, employers and health policy makers also have a responsibility to facilitate an environment conducive to such an approach [ 36 ]. In situations where this does not happen it can be argued that to not stand up and take appropriate action would in itself be unethical [ 37 ] and antithetical to the standards required. It has therefore been posited that concerns around patient safety and standards of care can now be seen as one of the key driving factors for nurse strikes [ 26 ].