6 Hypothesis Examples in Psychology

The hypothesis is one of the most important steps of psychological research. Hypothesis refers to an assumption or the temporary statement made by the researcher before the execution of the experiment, regarding the possible outcome of that experiment. A hypothesis can be tested through various scientific and statistical tools. It is a logical guess based on previous knowledge and investigations related to the problem under investigation. In this article, we’ll learn about the significance of the hypothesis, the sources of the hypothesis, and the various examples of the hypothesis.

Sources of Hypothesis

The formulation of a good hypothesis is not an easy task. One needs to take care of the various crucial steps to get an accurate hypothesis. The hypothesis formulation demands both the creativity of the researcher and his/her years of experience. The researcher needs to use critical thinking to avoid committing any errors such as choosing the wrong hypothesis. Although the hypothesis is considered the first step before further investigations such as data collection for the experiment, the hypothesis formulation also requires some amount of data collection. The data collection for the hypothesis formulation refers to the review of literature related to the concerned topic, and understanding of the previous research on the related topic. Following are some of the main sources of the hypothesis that may help the researcher to formulate a good hypothesis.

- Reviewing the similar studies and literature related to a similar problem.

- Examining the available data concerned with the problem.

- Discussing the problem with the colleagues, or the professional researchers about the problem under investigation.

- Thorough research and investigation by conducting field interviews or surveys on the people that are directly concerned with the problem under investigation.

- Sometimes ‘institution’ of the well known and experienced researcher is also considered as a good source of the hypothesis formulation.

Real Life Hypothesis Examples

1. null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis examples.

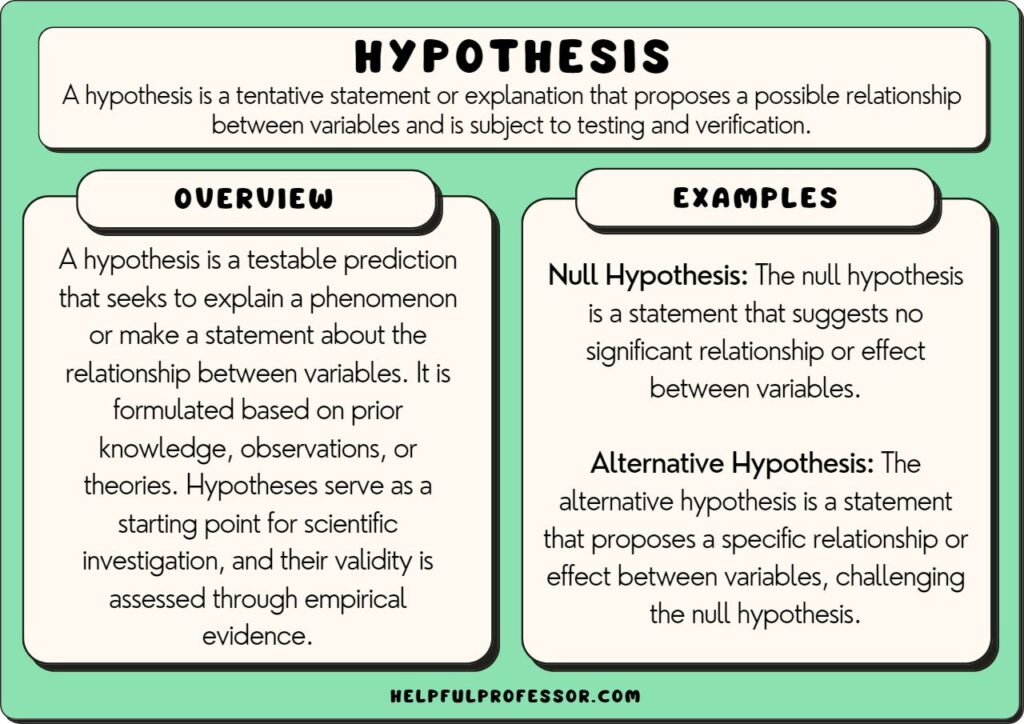

Every research problem-solving procedure begins with the formulation of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of the relationship between the variables under study, while the null hypothesis denies the relationship between the variables under study. Following are examples of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis based on the research problem.

Research Problem: What is the benefit of eating an apple daily on your health?

Alternative Hypothesis: Eating an apple daily reduces the chances of visiting the doctor.

Null Hypothesis : Eating an apple daily does not impact the frequency of visiting the doctor.

Research Problem: What is the impact of spending a lot of time on mobiles on the attention span of teenagers.

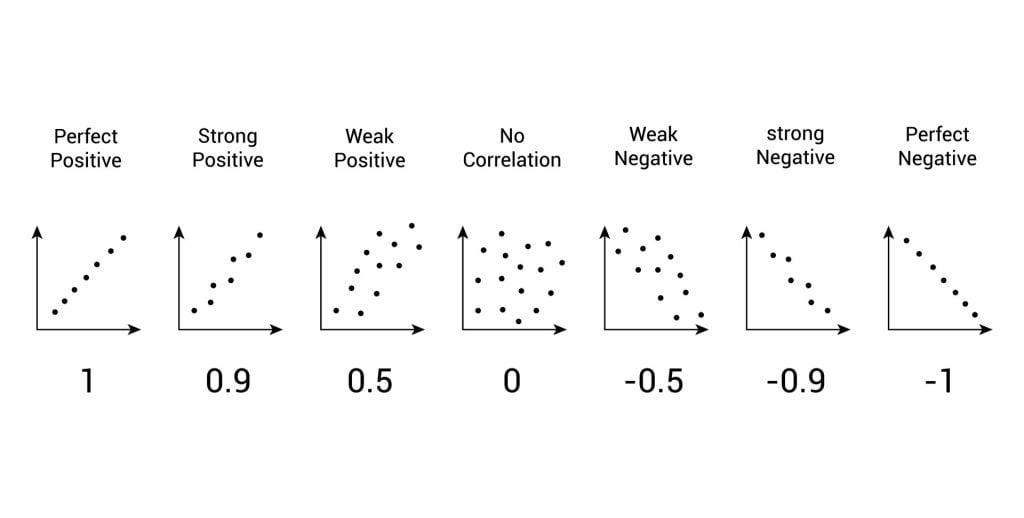

Alternative Problem: Spending time on the mobiles and attention span have a negative correlation.

Null Hypothesis: There does not exist any correlation between the use of mobile by teenagers on their attention span.

Research Problem: What is the impact of providing flexible working hours to the employees on the job satisfaction level.

Alternative Hypothesis : Employees who get the option of flexible working hours have better job satisfaction than the employees who don’t get the option of flexible working hours.

Null Hypothesis: There is no association between providing flexible working hours and job satisfaction.

2. Simple Hypothesis Examples

The hypothesis that includes only one independent variable (predictor variable) and one dependent variable (outcome variable) is termed the simple hypothesis. For example, the children are more likely to get clinical depression if their parents had also suffered from the clinical depression. Here, the independent variable is the parents suffering from clinical depression and the dependent or the outcome variable is the clinical depression observed in their child/children. Other examples of the simple hypothesis are given below,

- If the management provides the official snack breaks to the employees, the employees are less likely to take the off-site breaks. Here, providing snack breaks is the independent variable and the employees are less likely to take the off-site break is the dependent variable.

3. Complex Hypothesis Examples

If the hypothesis includes more than one independent (predictor variable) or more than one dependent variable (outcome variable) it is known as the complex hypothesis. For example, clinical depression in children is associated with a family clinical depression history and a stressful and hectic lifestyle. In this case, there are two independent variables, i.e., family history of clinical depression and hectic and stressful lifestyle, and one dependent variable, i.e., clinical depression. Following are some more examples of the complex hypothesis,

4. Logical Hypothesis Examples

If there are not many pieces of evidence and studies related to the concerned problem, then the researcher can take the help of the general logic to formulate the hypothesis. The logical hypothesis is proved true through various logic. For example, if the researcher wants to prove that the animal needs water for its survival, then this can be logically verified through the logic that ‘living beings can not survive without the water.’ Following are some more examples of logical hypotheses,

- Tia is not good at maths, hence she will not choose the accounting sector as her career.

- If there is a correlation between skin cancer and ultraviolet rays, then the people who are more exposed to the ultraviolet rays are more prone to skin cancer.

- The beings belonging to the different planets can not breathe in the earth’s atmosphere.

- The creatures living in the sea use anaerobic respiration as those living outside the sea use aerobic respiration.

5. Empirical Hypothesis Examples

The empirical hypothesis comes into existence when the statement is being tested by conducting various experiments. This hypothesis is not just an idea or notion, instead, it refers to the statement that undergoes various trials and errors, and various extraneous variables can impact the result. The trials and errors provide a set of results that can be testable over time. Following are the examples of the empirical hypothesis,

- The hungry cat will quickly reach the endpoint through the maze, if food is placed at the endpoint then the cat is not hungry.

- The people who consume vitamin c have more glowing skin than the people who consume vitamin E.

- Hair growth is faster after the consumption of Vitamin E than vitamin K.

- Plants will grow faster with fertilizer X than with fertilizer Y.

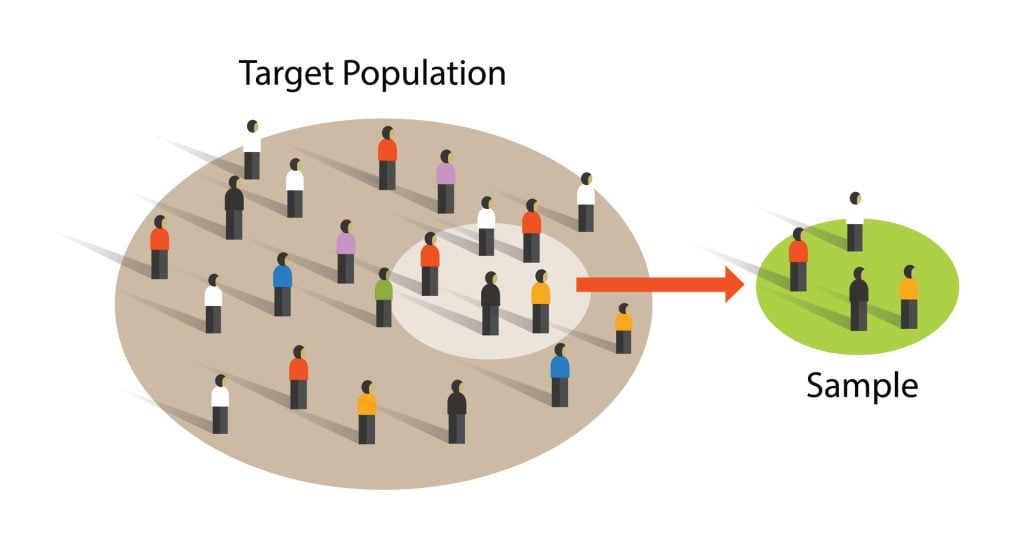

6. Statistical Hypothesis Examples

The statements that can be proven true by using the various statistical tools are considered the statistical hypothesis. The researcher uses statistical data about an area or the group in the analysis of the statistical hypothesis. For example, if you study the IQ level of the women belonging to nation X, it would be practically impossible to measure the IQ level of each woman belonging to nation X. Here, statistical methods come to the rescue. The researcher can choose the sample population, i.e., women belonging to the different states or provinces of the nation X, and conduct the statistical tests on this sample population to get the average IQ of the women belonging to the nation X. Following are the examples of the statistical hypothesis.

- 30 per cent of the women belonging to the nation X are working.

- 50 per cent of the people living in the savannah are above the age of 70 years.

- 45 per cent of the poor people in the United States are uneducated.

Significance of Hypothesis

A hypothesis is very crucial in experimental research as it aims to predict any particular outcome of the experiment. Hypothesis plays an important role in guiding the researchers to focus on the concerned area of research only. However, the hypothesis is not required by all researchers. The type of research that seeks for finding facts, i.e., historical research, does not need the formulation of the hypothesis. In the historical research, the researchers look for the pieces of evidence related to the human life, the history of a particular area, or the occurrence of any event, this means that the researcher does not have a strong basis to make an assumption in these types of researches, hence hypothesis is not needed in this case. As stated by Hillway (1964)

When fact-finding alone is the aim of the study, a hypothesis is not required.”

The hypothesis may not be an important part of the descriptive or historical studies, but it is a crucial part for the experimental researchers. Following are some of the points that show the importance of formulating a hypothesis before conducting the experiment.

- Hypothesis provides a tentative statement about the outcome of the experiment that can be validated and tested. It helps the researcher to directly focus on the problem under investigation by collecting the relevant data according to the variables mentioned in the hypothesis.

- Hypothesis facilitates a direction to the experimental research. It helps the researcher in analysing what is relevant for the study and what’s not. It prevents the researcher’s time as he does not need to waste time on reviewing the irrelevant research and literature, and also prevents the researcher from collecting the irrelevant data.

- Hypothesis helps the researcher in choosing the appropriate sample, statistical tests to conduct, variables to be studied and the research methodology. The hypothesis also helps the study from being generalised as it focuses on the limited and exact problem under investigation.

- Hypothesis act as a framework for deducing the outcomes of the experiment. The researcher can easily test the different hypotheses for understanding the interaction among the various variables involved in the study. On this basis of the results obtained from the testing of various hypotheses, the researcher can formulate the final meaningful report.

Related Posts

Role Morality

Backward and Forward Integration

5 Examples of Self-actualization Needs (Maslow’s Hierarchy)

Psychology and Other Disciplines

3 Psychodynamic Theory Examples

Kohlberg’s Stages and Theory of Moral Development Explained

Add comment cancel reply.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

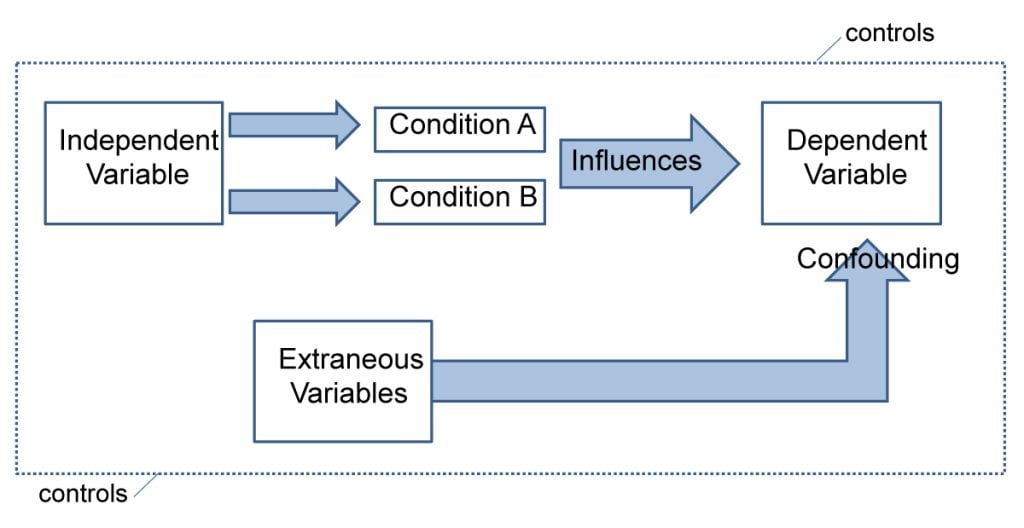

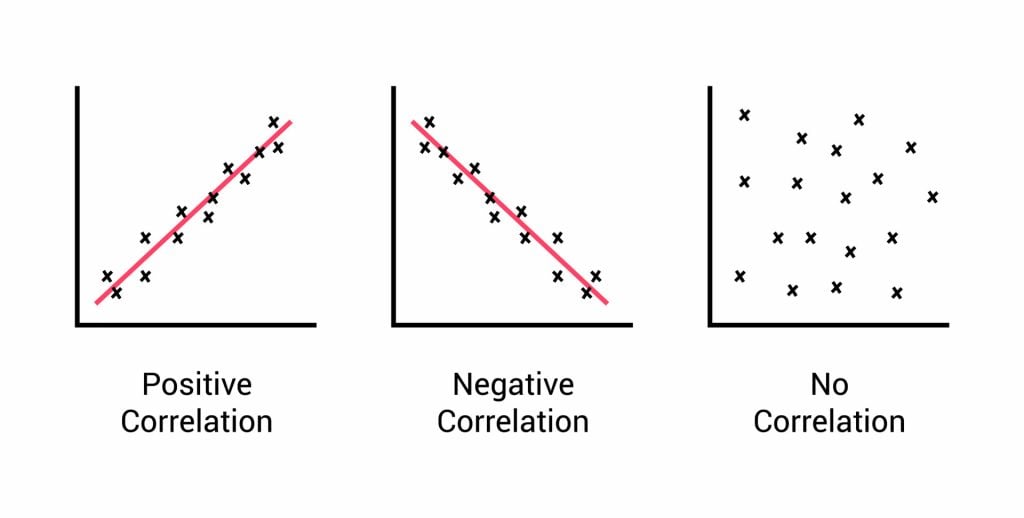

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

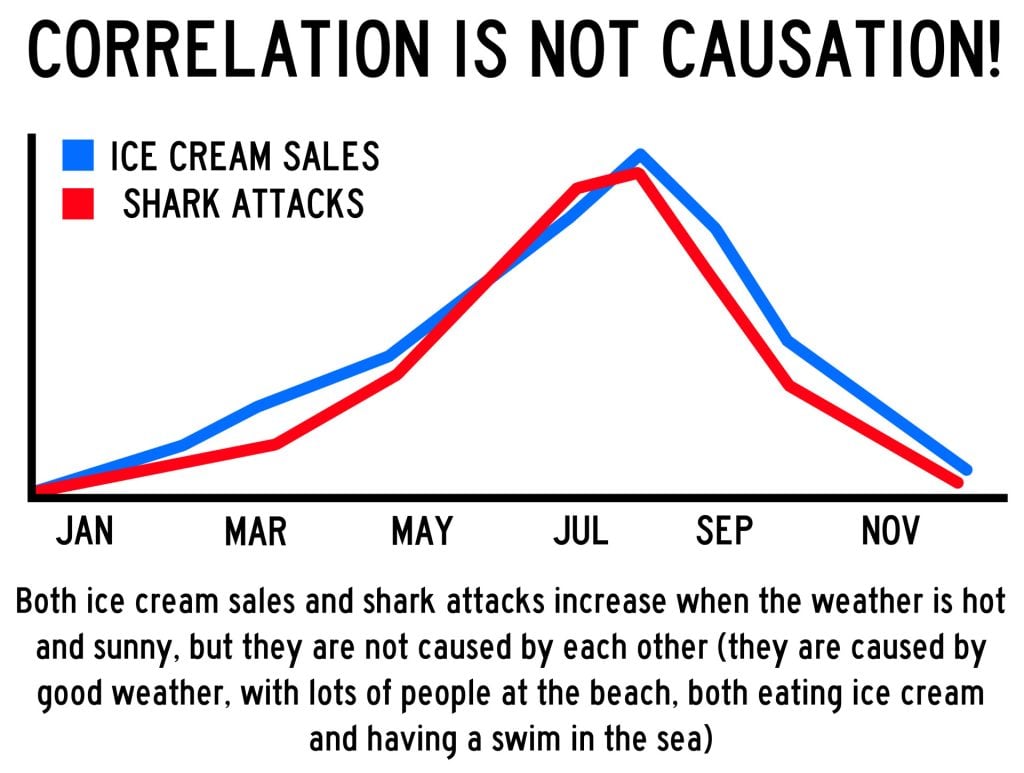

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

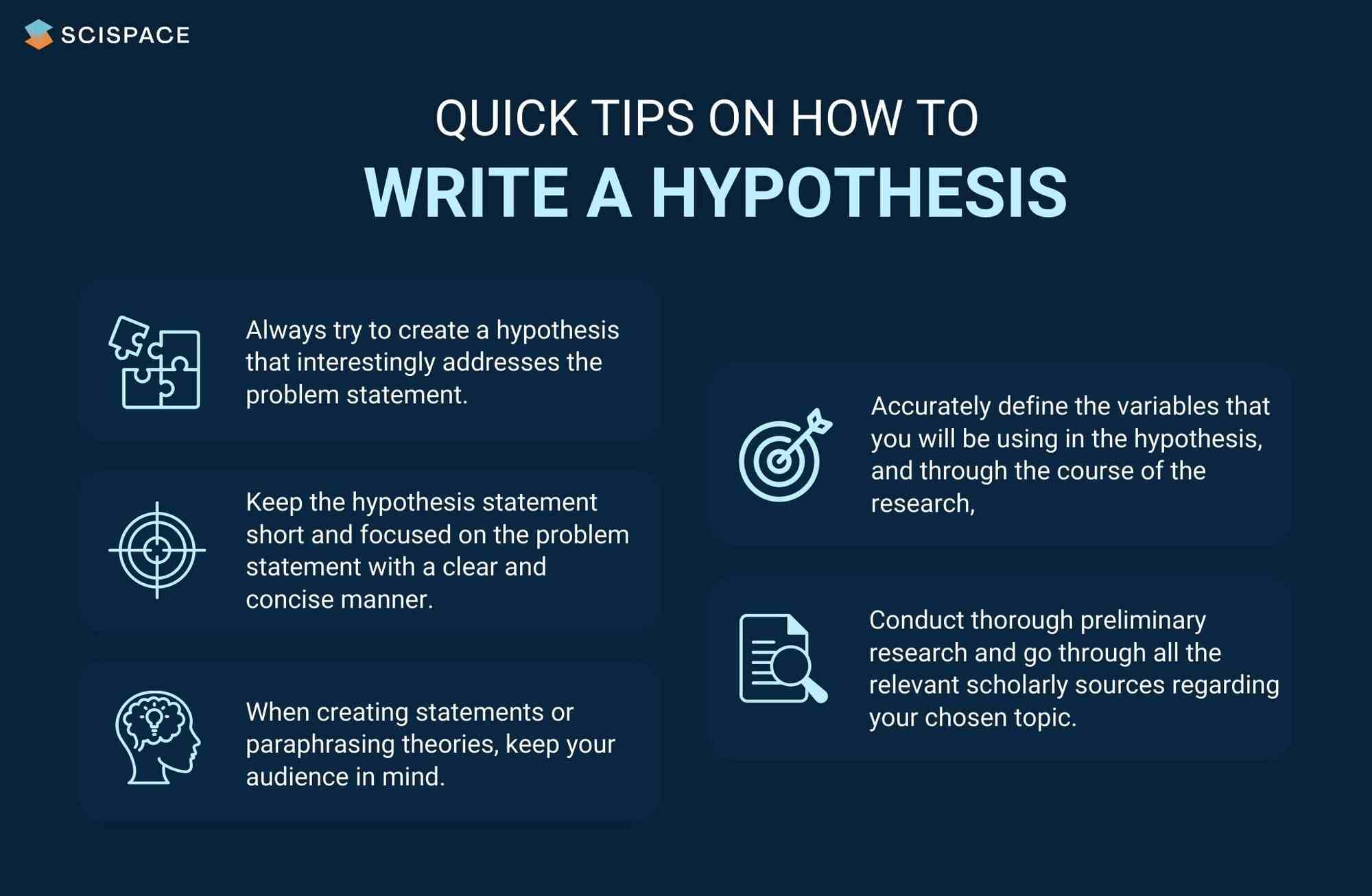

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

2.4 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is imporant to distinguish betwee a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

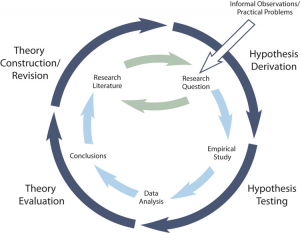

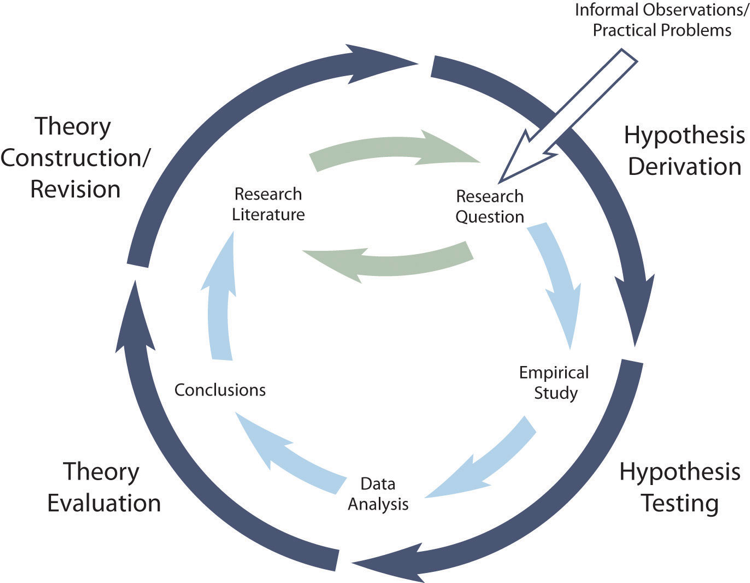

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 2.2 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Overview of the Scientific Method

10 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.3 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

A coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena.

A specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate.

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.

The ability to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and the possibility to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 Chapter 3: From Theory to Hypothesis

From theory to hypothesis, 3.1 phenomena and theories.

A phenomenon (plural, phenomena) is a general result that has been observed reliably in systematic empirical research. In essence, it is an established answer to a research question. Some phenomena we have encountered in this book are that expressive writing improves health, women do not talk more than men, and cell phone usage impairs driving ability. Some others are that dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder) increased greatly in prevalence during the late 20th century, people perform better on easy tasks when they are being watched by others (and worse on difficult tasks), and people recall items presented at the beginning and end of a list better than items presented in the middle.

Some Famous Psychological Phenomena

Phenomena are often given names by their discoverers or other researchers, and these names can catch on and become widely known. The following list is a small sample of famous phenomena in psychology.

· Blindsight. People with damage to their visual cortex are often able to respond to visual stimuli that they do not consciously see.

· Bystander effect. The more people who are present at an emergency situation, the less likely it is that any one of them will help.

· Fundamental attribution error. People tend to explain others’ behavior in terms of their personal characteristics as opposed to the situation they are in.

· McGurk effect. When audio of a basic speech sound is combined with video of a person making mouth movements for a different speech sound, people often perceive a sound that is intermediate between the two.

· Own-race effect. People recognize faces of people of their own race more accurately than faces of people of other races.

· Placebo effect. Placebos (fake psychological or medical treatments) often lead to improvements in people’s symptoms and functioning.

· Mere exposure effect. The more often people have been exposed to a stimulus, the more they like it—even when the stimulus is presented subliminally.

· Serial position effect. Stimuli presented near the beginning and end of a list are remembered better than stimuli presented in the middle.

· Spontaneous recovery. A conditioned response that has been extinguished often returns with no further training after the passage of time.

Although an empirical result might be referred to as a phenomenon after being observed only once, this term is more likely to be used for results that have been replicated. Replication means conducting a study again—either exactly as it was originally conducted or with modifications—to be sure that it produces the same results. Individual researchers usually replicate their own studies before publishing them. Many empirical research reports include an initial study and then one or more follow-up studies that replicate the initial study with minor modifications. Particularly interesting results come to the attention of other researchers who conduct their own replications. The positive effect of expressive writing on health and the negative effect of cell phone usage on driving ability are examples of phenomena that have been replicated many times by many different researchers.

Sometimes a replication of a study produces results that differ from the results of the initial study. This could mean that the results of the initial study or the results of the replication were a fluke—they occurred by chance and do not reflect something that is generally true. In either case, additional replications would be likely to resolve this. A failure to produce the same results could also mean that the replication differed in some important way from the initial study. For example, early studies showed that people performed a variety of tasks better and faster when they were watched by others than when they were alone. Some later replications, however, showed that people performed worse when they were watched by others. Eventually researcher Robert Zajonc identified a key difference between the two types of studies. People seemed to perform better when being watched on highly practiced tasks but worse when being watched on relatively unpracticed tasks (Zajonc, 1965). These two phenomena have now come to be called social facilitation and social inhibition.

What Is a Theory?

A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

In addition to theory, researchers in psychology use several related terms to refer to their explanations and interpretations of phenomena. A perspective is a broad approach—more general than a theory—to explaining and interpreting phenomena. For example, researchers who take a biological perspective tend to explain phenomena in terms of genetics or nervous and endocrine system structures and processes, while researchers who take a behavioral perspective tend to explain phenomena in terms of reinforcement, punishment, and other external events. A model is a precise explanation or interpretation of a specific phenomenon—often expressed in terms of equations, computer programs, or biological structures and processes. A hypothesis can be an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts—although this term more commonly refers to a prediction about a new phenomenon based on a theory. Adding to the confusion is the fact that researchers often use these terms interchangeably. It would not be considered wrong to refer to the drive theory as the drive model or even the drive hypothesis. And the biopsychosocial model of health psychology—the general idea that health is determined by an interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors—is really more like a perspective as defined here. Keep in mind, however, that the most important distinction remains that between observations and interpretations.

What Are Theories For?

Of course, scientific theories are meant to provide accurate explanations or interpretations of phenomena. But there must be more to it than this. Consider that a theory can be accurate without being very useful. To say that expressive writing helps people “deal with their emotions” might be accurate as far as it goes, but it seems too vague to be of much use. Consider also that a theory can be useful without being entirely accurate.

3.2 Additional Purposes of Theories

Here we look at three additional purposes of theories: the organization of known phenomena, the prediction of outcomes in new situations, and the generation of new research.

Organization

One important purpose of scientific theories is to organize phenomena in ways that help people think about them clearly and efficiently. The drive theory of social facilitation and social inhibition, for example, helps to organize and make sense of a large number of seemingly contradictory results. The multistore model of human memory efficiently summarizes many important phenomena: the limited capacity and short retention time of information that is attended to but not rehearsed, the importance of rehearsing information for long-term retention, the serial-position effect, and so on.

Thus theories are good or useful to the extent that they organize more phenomena with greater clarity and efficiency. Scientists generally follow the principle of parsimony, which holds that a theory should include only as many concepts as are necessary to explain or interpret the phenomena of interest. Simpler, more parsimonious theories organize phenomena more efficiently than more complex, less parsimonious theories.

A second purpose of theories is to allow researchers and others to make predictions about what will happen in new situations. For example, a gymnastics coach might wonder whether a student’s performance is likely to be better or worse during a competition than when practicing alone. Even if this particular question has never been studied empirically, Zajonc’s drive theory suggests an answer. If the student generally performs with no mistakes, she is likely to perform better during competition. If she generally performs with many mistakes, she is likely to perform worse.

In clinical psychology, treatment decisions are often guided by theories. Consider, for example, dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder). The prevailing scientific theory of dissociative identity disorder is that people develop multiple personalities (also called alters) because they are familiar with this idea from popular portrayals (e.g., the movie Sybil) and because they are unintentionally encouraged to do so by their clinicians (e.g., by asking to “meet” an alter). This theory implies that rather than encouraging patients to act out multiple personalities, treatment should involve discouraging them from doing this (Lilienfeld & Lynn, 2003).

Generation of New Research

A third purpose of theories is to generate new research by raising new questions. Consider, for example, the theory that people engage in self-injurious behavior such as cutting because it reduces negative emotions such as sadness, anxiety, and anger. This theory immediately suggests several new and interesting questions. Is there, in fact, a statistical relationship between cutting and the amount of negative emotions experienced? Is it causal? If so, what is it about cutting that has this effect? Is it the pain, the sight of the injury, or something else? Does cutting affect all negative emotions equally?

Notice that a theory does not have to be accurate to serve this purpose. Even an inaccurate theory can generate new and interesting research questions. Of course, if the theory is inaccurate, the answers to the new questions will tend to be inconsistent with the theory. This will lead researchers to reevaluate the theory and either revise it or abandon it for a new one. And this is how scientific theories become more detailed and accurate over time.

Multiple Theories

At any point in time, researchers are usually considering multiple theories for any set of phenomena. One reason is that because human behavior is extremely complex, it is always possible to look at it from different perspectives. For example, a biological theory of sexual orientation might focus on the role of sex hormones during critical periods of brain development, while a sociocultural theory might focus on cultural factors that influence how underlying biological tendencies are expressed. A second reason is that—even from the same perspective—there are usually different ways to “go beyond” the phenomena of interest. For example, in addition to the drive theory of social facilitation and social inhibition, there is another theory that explains them in terms of a construct called “evaluation apprehension”—anxiety about being evaluated by the audience. Both theories go beyond the phenomena to be interpreted, but they do so by proposing somewhat different underlying processes.

Different theories of the same set of phenomena can be complementary—with each one supplying one piece of a larger puzzle. A biological theory of sexual orientation and a sociocultural theory of sexual orientation might accurately describe different aspects of the same complex phenomenon. Similarly, social facilitation could be the result of both general physiological arousal and evaluation apprehension. But different theories of the same phenomena can also be competing in the sense that if one is accurate, the other is probably not. For example, an alternative theory of dissociative identity disorder—the posttraumatic theory—holds that alters are created unconsciously by the patient as a means of coping with sexual abuse or some other traumatic experience. Because the sociocognitive theory and the posttraumatic theories attribute dissociative identity disorder to fundamentally different processes, it seems unlikely that both can be accurate.

The fact that there are multiple theories for any set of phenomena does not mean that any theory is as good as any other or that it is impossible to know whether a theory provides an accurate explanation or interpretation. On the contrary, scientists are continually comparing theories in terms of their ability to organize phenomena, predict outcomes in new situations, and generate research. Those that fare poorly are assumed to be less accurate and are abandoned, while those that fare well are assumed to be more accurate and are retained and compared with newer—and hopefully better—theories. Although scientists generally do not believe that their theories ever provide perfectly accurate descriptions of the world, they do assume that this process produces theories that come closer and closer to that ideal.

Key Takeaways

· Scientists distinguish between phenomena, which are their systematic observations, and theories, which are their explanations or interpretations of phenomena.

· In addition to providing accurate explanations or interpretations, scientific theories have three basic purposes. They organize phenomena, allow people to predict what will happen in new situations, and help generate new research.

· Researchers generally consider multiple theories for any set of phenomena. Different theories of the same set of phenomena can be complementary or competing.

3.3 Using Theories in Psychological Research

We have now seen what theories are, what they are for, and the variety of forms that they take in psychological research. In this section we look more closely at how researchers actually use them. We begin with a general description of how researchers test and revise their theories, and we end with some practical advice for beginning researchers who want to incorporate theory into their research.

Theory Testing and Revision

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us return to Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This leads to social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969). The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory.

Constructing or Choosing a Theory

Along with generating research questions, constructing theories is one of the more creative parts of scientific research. But as with all creative activities, success requires preparation and hard work more than anything else. To construct a good theory, a researcher must know in detail about the phenomena of interest and about any existing theories based on a thorough review of the literature. The new theory must provide a coherent explanation or interpretation of the phenomena of interest and have some advantage over existing theories. It could be more formal and therefore more precise, broader in scope, more parsimonious, or it could take a new perspective or theoretical approach. If there is no existing theory, then almost any theory can be a step in the right direction.

As we have seen, formality, scope, and theoretical approach are determined in part by the nature of the phenomena to be interpreted. But the researcher’s interests and abilities play a role too. For example, constructing a theory that specifies the neural structures and processes underlying a set of phenomena requires specialized knowledge and experience in neuroscience (which most professional researchers would acquire in college and then graduate school). But again, many theories in psychology are relatively informal, narrow in scope, and expressed in terms that even a beginning researcher can understand and even use to construct his or her own new theory.

It is probably more common, however, for a researcher to start with a theory that was originally constructed by someone else—giving due credit to the originator of the theory. This is another example of how researchers work collectively to advance scientific knowledge. Once they have identified an existing theory, they might derive a hypothesis from the theory and test it or modify the theory to account for some new phenomenon and then test the modified theory.

Deriving Hypotheses

Again, a hypothesis is a prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in Chapter 2 and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this is an interesting question on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991). Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Evaluating and Revising Theories

If a hypothesis is confirmed in a systematic empirical study, then the theory has been strengthened. Not only did the theory make an accurate prediction, but there is now a new phenomenon that the theory accounts for. If a hypothesis is disconfirmed in a systematic empirical study, then the theory has been weakened. It made an inaccurate prediction, and there is now a new phenomenon that it does not account for.