- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

- Formal Analysis Paper Examples

Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Writing a paper for an art history course is similar to the analytical, research-based papers that you may have written in English literature courses or history courses. Although art historical research and writing does include the analysis of written documents, there are distinctive differences between art history writing and other disciplines because the primary documents are works of art. A key reference guide for researching and analyzing works of art and for writing art history papers is the 10th edition (or later) of Sylvan Barnet’s work, A Short Guide to Writing about Art . Barnet directs students through the steps of thinking about a research topic, collecting information, and then writing and documenting a paper.

A website with helpful tips for writing art history papers is posted by the University of North Carolina.

Wesleyan University Writing Center has a useful guide for finding online writing resources.

The following are basic guidelines that you must use when documenting research papers for any art history class at UA Little Rock. Solid, thoughtful research and correct documentation of the sources used in this research (i.e., footnotes/endnotes, bibliography, and illustrations**) are essential. Additionally, these guidelines remind students about plagiarism, a serious academic offense.

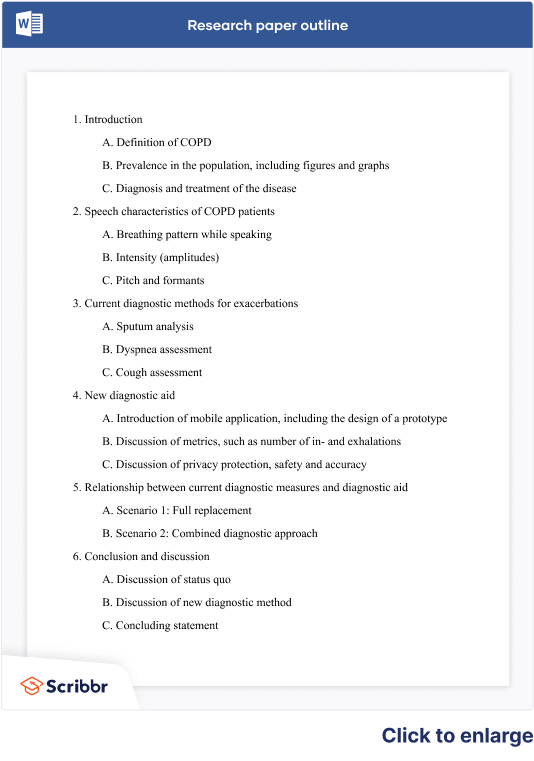

Paper Format

Research papers should be in a 12-point font, double-spaced. Ample margins should be left for the instructor’s comments. All margins should be one inch to allow for comments. Number all pages. The cover sheet for the paper should include the following information: title of paper, your name, course title and number, course instructor, and date paper is submitted. A simple presentation of a paper is sufficient. Staple the pages together at the upper left or put them in a simple three-ring folder or binder. Do not put individual pages in plastic sleeves.

Documentation of Resources

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), as described in the most recent edition of Sylvan Barnet’s A Short Guide to Writing about Art is the department standard. Although you may have used MLA style for English papers or other disciplines, the Chicago Style is required for all students taking art history courses at UA Little Rock. There are significant differences between MLA style and Chicago Style. A “Quick Guide” for the Chicago Manual of Style footnote and bibliography format is found http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html. The footnote examples are numbered and the bibliography example is last. Please note that the place of publication and the publisher are enclosed in parentheses in the footnote, but they are not in parentheses in the bibliography. Examples of CMS for some types of note and bibliography references are given below in this Guideline. Arabic numbers are used for footnotes. Some word processing programs may have Roman numerals as a choice, but the standard is Arabic numbers. The use of super script numbers, as given in examples below, is the standard in UA Little Rock art history papers.

The chapter “Manuscript Form” in the Barnet book (10th edition or later) provides models for the correct forms for footnotes/endnotes and the bibliography. For example, the note form for the FIRST REFERENCE to a book with a single author is:

1 Bruce Cole, Italian Art 1250-1550 (New York: New York University Press, 1971), 134.

But the BIBLIOGRAPHIC FORM for that same book is:

Cole, Bruce. Italian Art 1250-1550. New York: New York University Press. 1971.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in a footnote is:

2 Anne H. Van Buren, “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits,” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 199.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in the BIBLIOGRAPHY is:

Van Buren, Anne H. “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits.” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 185-204.

If you reference an article that you found through an electronic database such as JSTOR, you do not include the url for JSTOR or the date accessed in either the footnote or the bibliography. This is because the article is one that was originally printed in a hard-copy journal; what you located through JSTOR is simply a copy of printed pages. Your citation follows the same format for an article in a bound volume that you may have pulled from the library shelves. If, however, you use an article that originally was in an electronic format and is available only on-line, then follow the “non-print” forms listed below.

B. Non-Print

Citations for Internet sources such as online journals or scholarly web sites should follow the form described in Barnet’s chapter, “Writing a Research Paper.” For example, the footnote or endnote reference given by Barnet for a web site is:

3 Nigel Strudwick, Egyptology Resources , with the assistance of The Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge University, 1994, revised 16 June 2008, http://www.newton.ac.uk/egypt/ , 24 July 2008.

If you use microform or microfilm resources, consult the most recent edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual of Term Paper, Theses and Dissertations. A copy of Turabian is available at the reference desk in the main library.

C. Visual Documentation (Illustrations)

Art history papers require visual documentation such as photographs, photocopies, or scanned images of the art works you discuss. In the chapter “Manuscript Form” in A Short Guide to Writing about Art, Barnet explains how to identify illustrations or “figures” in the text of your paper and how to caption the visual material. Each photograph, photocopy, or scanned image should appear on a single sheet of paper unless two images and their captions will fit on a single sheet of paper with one inch margins on all sides. Note also that the title of a work of art is always italicized. Within the text, the reference to the illustration is enclosed in parentheses and placed at the end of the sentence. A period for the sentence comes after the parenthetical reference to the illustration. For UA Little Rcok art history papers, illustrations are placed at the end of the paper, not within the text. Illustration are not supplied as a Powerpoint presentation or as separate .jpgs submitted in an electronic format.

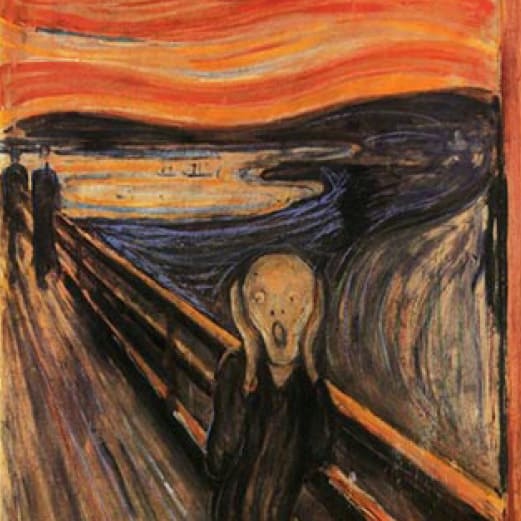

Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream, dated 1893, represents a highly personal, expressive response to an experience the artist had while walking one evening (Figure 1).

The caption that accompanies the illustration at the end of the paper would read:

Figure 1. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Tempera and casein on cardboard, 36 x 29″ (91.3 x 73.7 cm). Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway.

Plagiarism is a form of thievery and is illegal. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, to plagiarize is to “take and pass off as one’s own the ideas, writings, etc. of another.” Barnet has some useful guidelines for acknowledging sources in his chapter “Manuscript Form;” review them so that you will not be mguilty of theft. Another useful website regarding plagiarism is provided by Cornell University, http://plagiarism.arts.cornell.edu/tutorial/index.cfm

Plagiarism is a serious offense, and students should understand that checking papers for plagiarized content is easy to do with Internet resources. Plagiarism will be reported as academic dishonesty to the Dean of Students; see Section VI of the Student Handbook which cites plagiarism as a specific violation. Take care that you fully and accurately acknowledge the source of another author, whether you are quoting the material verbatim or paraphrasing. Borrowing the idea of another author by merely changing some or even all of your source’s words does not allow you to claim the ideas as your own. You must credit both direct quotes and your paraphrases. Again, Barnet’s chapter “Manuscript Form” sets out clear guidelines for avoiding plagiarism.

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

- University of Texas Libraries

Art and Art History

- How to Write About Art

- Overview Resources

- Find Art & Art History Books

- Find Art and Art History Articles

- Find Images

- Color Resources

- Collecting & Provenance This link opens in a new window

- Art Collections at UT

- Foundry @ FAL Information

- Professional Art Organizations

Write and Cite

- Cite Sources UT Austin Guide Learn more about what citations are and how to manage them. Includes information about citation tools like Noodle Tools and Zotero.

- UT Austin University Writing Center A resource for help with your writing. The Writing Center includes one on one consultations as well as classes.

- OWL Purdue - Chicago Style The OWL Purdue is a great resource for writing and citation help. Chicago Style is the preferred citation format for art history. The OWL also includes citation help for other styles include APA and MLA.

Writing Aids and Publication Manuals

Write about Art

- Last Updated: Oct 20, 2023 7:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/art

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Hum Neurosci

Visualizing the Impact of Art: An Update and Comparison of Current Psychological Models of Art Experience

Matthew pelowski.

1 Department of Basic Research and Research Methods, Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Patrick S. Markey

Jon o. lauring.

2 BRAINlab, Department of Neuroscience and Pharmacology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Helmut Leder

The last decade has witnessed a renaissance of empirical and psychological approaches to art study, especially regarding cognitive models of art processing experience. This new emphasis on modeling has often become the basis for our theoretical understanding of human interaction with art. Models also often define areas of focus and hypotheses for new empirical research, and are increasingly important for connecting psychological theory to discussions of the brain. However, models are often made by different researchers, with quite different emphases or visual styles. Inputs and psychological outcomes may be differently considered, or can be under-reported with regards to key functional components. Thus, we may lose the major theoretical improvements and ability for comparison that can be had with models. To begin addressing this, this paper presents a theoretical assessment, comparison, and new articulation of a selection of key contemporary cognitive or information-processing-based approaches detailing the mechanisms underlying the viewing of art. We review six major models in contemporary psychological aesthetics. We in turn present redesigns of these models using a unified visual form, in some cases making additions or creating new models where none had previously existed. We also frame these approaches in respect to their targeted outputs (e.g., emotion, appraisal, physiological reaction) and their strengths within a more general framework of early, intermediate, and later processing stages. This is used as a basis for general comparison and discussion of implications and future directions for modeling, and for theoretically understanding our engagement with visual art.

Introduction

Today, millions of individuals across the globe regularly encounter works of art. Whether, in the museum, the city-center, or on the web, art is an omnipresent part of human life. Underlying the fascination with art is a uniquely impactful experience. When individuals describe noteworthy art or explain why they go to museums, most often they refer to a complex mix of psychological events (Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 ). Art viewing engenders myriad emotions, evokes evaluations, physiological reactions, and in some cases can mark or alter lives. Reactions can also differ greatly between individuals and settings, or evolve within individual experiences themselves.

Understanding this multifaceted impact of art is key for numerous areas of scholarship—including all humanities, sociology, evolution, museum education, art history—and is especially key for psychology and empirical art research (Leder, 2013 ). The relevance of the topic has only grown in the past decade, which has seen a burgeoning of psychological aesthetics through the emergence of new empirical methods, growing interest in affect and emotion, and new integration between behavioral and neurophysiological analyses.

Perhaps most important, recent approaches have been accompanied by attempts to model the underlying processes of art engagement (Leder, 2013 ). These models build from recent trends in cognitive science, employing a visual approach for highlighting the interconnections and outcomes in our experience. They posit key inputs, and connect these via a flow of processing stages (often utilizing a box-and-arrow design) to outcomes or psychological implications. Thus, by offering a process-driven articulation of psychological elements, models have become the indispensable basis for shaping hypotheses. Even more, by stepping beyond written theory and articulating ideas within a visual frame, models can emphasize processes and important elements that previously might have been merely implicit. Thus, the visual models themselves often become the working theories for art study, and determine empirical research.

However, current modeling also suffers from several limitations, which hamper our ability to fully compare and understand approaches. Models are often made with different emphases and visual grammars. There are often also different arrangements of processing stages or focus on different portions of the processing sequence. Psychological inputs and outcomes are also often differently considered, or can be omitted from the processing sequence. Thus, we often lose the major theoretical benefit—a clear connection between inputs, processes, and outputs—that can be had from placing ideas into a visual form. It is also difficult to consider various models' overlaps or major differences when explaining specific reactions to art, and thus difficult to articulate how they might contribute to our understanding of art experience.

This is the goal of this paper, which represents our attempt to provide a comparison of current key modeling approaches, and involving their translation into a comparable visual format. We do this by reviewing six influential approaches to art experience, as well as supporting literature by the same authors, and place these into a model form. For existing models, we adapt the previous approaches to a unified layout, and also suggest additions or changes based on our literature review. When an author's idea does not yet have a visual form, we newly create models based on their arguments. Through our review, we also give specific consideration to outputs or psychological implications for art experience, as well as general organization around early, intermediate and late processing stages. We end with a synthesis and discussion of avenues for future research. In this review, we have chosen approaches, which, we feel, have come to be bases for the past decade of general empirical art-viewing research, and which employ a cognitive or information processing focus. Although this paper can, admittedly, only address a small selection of models, by providing this analysis, we hope to create one more useful tool for advancing understanding of art processing and modeling research.

Review: key model components and previous approaches to modeling art

Before beginning, it is instructive to briefly review what aspects should be considered in models of viewing art, and which will provide the material for this paper's comparison. Psychological models generally have three main components. These include: (1) inputs that feed into experience. These might include personality of the viewer, social or cultural setting, background affective state, other context (e.g., Jacobsen, 2006 ), as well as the specific artwork body and its history (Bullot and Reber, 2013 ); (2) processing mechanisms, which act on the inputs in specific stages (explained further below); and (3) mental and behavioral consequences (outputs) that arise from processing art. While it is the second stage of actual processing that makes up the bulk of models we will review, it is these outputs that constitute their implicit goal of addressing art interaction, and also the frame for this paper's review.

A literature review suggests multiple output examples. We have given these short labels, which will be used in the following discussions, and which can be divided into four main clusters: First, art has the capability to influence basic aspects of affect or the body. This can come from: (1) Affect , specific emotions/moods evoked by content or derived from the act of viewing; (2) Physiology , such as heart rate, skin conductivity, or other processes of the autonomic nervous system (e.g., Tschacher et al., 2012 ); and (3) Actions , for example gesture, eye movement, or physical movement during art reception.

Art also has been connected to numerous aspects of perception and understanding (e.g., see Leder et al., 2004 ), including: (4) Appraisals or particular judgments (beauty, liking); (5) Meaning-making as well as ability to strengthen conceptions, help us to learn, challenge our ideas, or even lead to insight. (6) Novelty: Art can impact what we see, induce changes in visual or perceptual experience involving new attention to physical aspects.

There are also elements which are more art-specific, or which are particularly salient in reports of art experience: (7) Transcendence : feelings of more sudden change, epiphany, or catharsis (Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 ); (8) Aesthetic mode: “aesthetic” emotions and responses, which might involve a state of being, whereby one detaches or uncouples from concerns or everyday life perceptions, often related to periods of contemplation or harmonious enjoyment, as well as potential positive reaction to negatively-valenced or troubling art (Cupchik et al., 2009 ). (9) Negative affect: Art can also evoke negative reactions such as disgust, queasiness or anger—outcomes that particularly require an explanation in models of experience (Silvia, 2009 ).

Art is also argued to create longitudinal impacts. These include: (10) Self-adjustment , changes in one's personality, worldview, cognitive ability (Lasher et al., 1983 ), or in the relation between art and viewer. This might also include a deepened ability to appreciate art or a more general improvement in visual-spatial ability (Funch et al., 2012 ). (11) Social : Art also may guide social behavior—e.g., in rituals or institutions—or lead to social ends such as indoctrination or social cohesion (Dissayanake, 2008 ). (12) Health : art may even have general impact on health and wellbeing, for example through reduced stress (Cuypers et al., 2012 ).

A brief note on previous art modeling research

The above aspects have been the main focus for attempts to explain interaction with art. Models—as a result of systematic, scientific endeavor—can be traced back to at least the work of Berlyne (e.g., Berlyne, 1960 , 1974 ; see also Funch, 2013 for review), who revived focus on art within empirical aesthetics, integrating a psychophysiological and cognitive perspective. Looking to physiological arousal, he posited opposing reward and aversion systems tied to “collative” art properties. He was followed by Kreitler and Kreitler ( 1972 ), who took a largely cognitive and Gestalt approach, arguing that artwork content and structure make it a carrier of multiple meanings that can stimulate understanding and emotion. Similarly, based on Gestalt perception, (e.g., Arnheim, 1966 ) considered the means whereby structural unity of artworks (balance, grouping) and individual features drive responses. This was followed by, for example, Martindale (Martindale, 1988 ; Martindale et al., 1988 ), who more fully emphasized cognition, focusing on matching of schema and stimulus, and proposing prototypicality as a key determinant for positive appraisal/affective response. These were followed by an even greater expansion of approaches. Notable examples include: Lasher et al. ( 1983 ), who proposed a cognition-based model of profound experience or insight; Ramachandran and Hirstein ( 1999 ), who gave one of the first attempts to posit universal rules for reactions and their underlying biological or neurological connections; and Jacobsen ( 2006 ) as well as Solso ( 1994 ), Vitz ( 1988 ), Zeki and Nash ( 1999 ), who presented an integrative neuro-cognitive theory. Other important approaches, many of which deal with specific aspects of viewing, also include: the fluency-based theory of aesthetic pleasure by Reber et al. ( 2004 ); Graf and Landwehr's ( 2015 ) updated consideration of fluency and visual interest; Van de Cruys and Wagemans ( 2011 ) account of rewarding reactions; Armstrong and Detweiler-Bedell's ( 2008 ) work with beauty; Funch's ( 2007 ) phenomenological model of art experience; Carbon ( 2011 ); Hekkert's ( 2012 ) design-based model; Bullot and Reber's ( 2013 ) integrated model of low-level processes and top-down integration regarding viewer knowledge of artwork history; and Tinio's ( 2013 ) consideration of creating/viewing art.

These approaches, among many others, give a basis for present modeling, notably pointing out the importance of individual elements such as beauty, pleasure. They also represent a research trend from emphasizing single, often simple visual elements to a more complex interplay of factors, which may drive emotion and physiological response. Especially cognitive approaches have also strongly contributed to the basic input-process-output form of the models we consider below.

Current models and cohesive theories of interacting with art

What follows is a review of six models, which we feel, offer a good overview of present approaches to general empirical exploration of art experience. These again are not the only important models, as witnessed from the review above, but were chosen because they offer psychological explanations which are explicit in respect to underlying cognitive processes, and which are presently used in empirical consideration of outputs/inputs when viewing art. The following paragraphs will follow a repeated pattern: First, the background and main elements of each model are presented and put into a unified visual form. When a visual example has been previously produced by the models' authors, we have attempted to reproduce in verbatim the original structure and wording, with only some shifting in the location of elements. At the same time, we have taken the liberty of creating new models or new processing elements when this was deemed to be necessary. To distinguish from our own additions, previously created model components are shown in black, while our contributions are shown in blue. All models will thus have a standardized format, employing five components. Inputs and contextual factors are shown with rounded edges and depicted on the far left, processing stages in the middle, and outputs on the far right (distinguished by a gray band).

The middle section also incorporates a timeline (bottom), showing general ordering and designating early, intermediate, and late processing stages. These were included because the specific placement of components within these stages may be key in hypothesis-making, and the relative emphasis also varies greatly between the reviewed models. Although there is as of yet no agreed-upon distinction, generally the early stage refers to immediate, automatic, bottom-up visual processing and attention, while intermediate refers to more specific processes involving object recognition, classification and memory contribution. The late stage refers to more overt cognitive components such as reflection, association, or changes in viewer approach (Leder and Nadal, 2014 ). Thus, this factor provided one more point for comparison and for the ordering of model presentation below. In the time line, we also include designation of automatic or more overtly conscious processing, as this is mentioned in many approaches. Finally, specific outputs, using the above labels (see also Table 2 ), are placed in red circles at their suggested model location. If an output could be posited, yet was not explicitly considered by the authors, it is shown in a lighter shade.

Chatterjee: neurological/cognitive model

We begin with the earliest model from the present group, and one which emphasizes early processing stages. This also makes a nice example of the present box and arrow design. This model was introduced by Chatterjee ( 2004 , 2009 , 2010 ; see Cela-Conde et al., 2011 for review), and has become a central tool for framing empirical assessments. It was designed to address cognitive and neuropsychological aspects, connecting processing stages to brain functioning. Chatterjee ( 2010 ) argues that visual interaction with art has multiple components and that experience emerges from a combination of responses to these elements. It draws its main theoretical emphasis from vision research (Chatterjee, 2004 , 2010 ). Thus, it focuses primarily on three stages which are argued to correspond to the rough functional division of “early,” “intermediate,” and “late” human visual recognition (e.g., Marr, 1982 ).

As shown in Figure Figure1, 1 , where we have reproduced the original model, Chatterjee posits that visual attributes of art are first processed, like any other stimulus, by extracting simple components (location, color, shape, luminance, motion) from the visual environment, and processing these in different brain regions 1 . Early features are subsequently either segregated or, most often, grouped to form larger units in intermediate vision. Here, elements help to define the object and to “process and make sense of what would otherwise be a chaotic and overwhelming” array of information (Chatterjee, 2004 , p. 55). Late vision then involves selecting regions to scrutinize or to give attention, as well as evoking memories, attaching meaning, and assessing foci of specific evolutionary importance (e.g., faces, landscapes) 2 . Following recognition and assessment, evaluations are then evoked as well as emotions.

Chatterjee model adapted from original visual model in Chatterjee ( 2004 ) . Original elements shown in black. Additions not originally included in model shown in blue. If possible, original wording has been retained or adapted from model author's publications.

This model also provides an important basis for empirically approaching the role of the brain, with imaging studies having identified regions tied to its posited stages (Nadal et al., 2008 ). It affords a basis for making observations about how we progress in viewing, and how particular aspects—in relation to the way they are processed by the brain—impact judgments. For example, it suggests that one first perceives formal elements due to their importance in early and intermediate vision, while content is typically assessed in later vision (Chatterjee, 2010 ). Further, the model affords nuanced understanding of how processes may integrate. For example, the process of taking initially diverse perceptions from the first stage and grouping them within the second may explain satisfaction or interest often generated by complex art (Chatterjee, 2004 ), suggesting a “unity in diversity,” which itself is a central idea in aesthetics.

The model also highlights the transition from automatic to self-aware assessment. It is argued that the initial perception of many formal features (e.g., attractiveness, beauty), as well as intermediate grouping, occurs automatically (Chatterjee, 2010 ). This is followed by memory-dependent processing, where the perceiver's knowledge and background experiences are activated, and consequently, objects are identified, leading to experience-defining outcomes that result from often effortful and focused cognition, such as meaning-making and aesthetic judgments (Tinio, 2013 ). Thus, a general progression from bottom-up to top-down processing, and from low-level features to more complex higher-order assessments of art, is illustrated. This approach does not imply a strictly linear “sequence” (Chatterjee, 2004 ). Rather, processes may often run in parallel, and the individual may revisit or jump between stages (Nadal et al., 2008 ).

Model outputs

This model affords opportunity for discussion of several impacts from art (Zaidel et al., 2013 for similar review). First, the model first focuses on reward value, which is connected to numerous brain regions and specifically associated with the generation of pleasant feelings in anticipation and response to art (“ Affect ” in Figure Figure1 1 ) 3 . High-level top-down processes are also involved in forming evaluative judgments and thus represent another vital component of aesthetic experiences ( Appraisal ) 4 . The model proposes a fluency or mastery-based assessment, where success in processing leads to positive responses. Due to its tie to brain function in reward and pleasure areas, the model could potentially also account for Negative responses here, which would presumably be linked to failing to place and group visual aspects, although this had not been described (we have made this addition in the Figure). The processing of objects, extraction of prototypes, connection to memory and final decision would also presumably connect to meaning-making or understanding ( Meaning ). Zaidel et al. ( 2013 , p. 104) also note that “neuroimaging studies have identified an enhancement of cortical sensory processing” 5 during aesthetic experiences. This would involve attention and may be tied to physical Action (eye movements), Physiology (relating to enhanced brain activity in certain regions), and changes in perception (enabling perception of new aspects or Novelty ). This process may also include self-awareness, monitoring of one's affective state or conflict resolution, which may play a role in bringing about final aesthetic emotion and judgment.

The above three aspects are also connected to the possibility for profound/ Aesthetic experience. If intermediate processing involves perceptions of specifically compelling or pleasing qualities of an object (e.g., symmetry, balance, as well as content) these qualities are argued to engage frontal-parietal attention circuits. These networks may continue to modulate processing, as an individual continues looking, within the ventral visual stream. Thus, “a feed forward system,” as might be seen in the arrow connecting early vision to attention, is established “in which the attributes of an aesthetic object engage attention, and attention further enhances the processing of these attributes” (Chatterjee, 2004 , p. 55), leading to heightened engagement and pleasure. This outcome may also be particularly unique for defining aesthetic experiences (Nadal et al., 2008 ). We have suggested this connection in our update to the model.

Chatterjee ( 2011 ) also suggests that the evolutionary or biological basis for human fascination with art may be tied to the interplay of three factors: (1) beauty, potentially linked to the evolutionary aspect of mate selection; (2) aesthetic attitude, or mental processes involved when apprehending objects, and which may connect with the idea of “prototypes” (presumably in early vision) which are preferred and may influence environmental navigation. Finally, (3) he notes cultural or socially-derived concepts of “making special” (e.g., Dissayanake, 2008 ), where ordinary objects are transformed by the artist and whereby the institutional frameworks that promote and display art may tie to adaptive importance in enhancing cooperation and continuity within human groups. This latter might then connect to more longitudinal impacts ( Social ).

Regarding inputs (primarily the blue arrows from the model left side), Tinio ( 2013 ), in his review, notes that the intermediary stage of vision should involve processing that recruits access to memory and processing that involves higher-order cognitions such as the perceiver's knowledge and background experiences, which may also influence the final stage of meaning-making. Chatterjee ( 2004 ), referencing Ramachandran and Hirstein ( 1999 ), also notes the importance of several artwork qualities. He suggests that neural structures that evolved to respond to specific visual stimuli respond more vigorously to primitives. This may be both based on previous experience, while also explaining the specific power of abstract art. In later theoretical work, he explained how other design cues might further impact the viewer. For example, artists might play with certain art-processing elements—violating physics of shadows, reflections, colors, and contours—thereby engendering specific brain responses (Chatterjee, 2010 ). Artists' use of complex interactions between visual components within art may also create a specifically powerful response by causing interplay between the dorsal (“where”) and ventral (“what”) vision systems within the first and second stages. Because the dorsal stream is sensitive to luminance differences, motion, and spatial location, while the ventral stream is sensitive to simple form and color, their interaction may lead to a shimmering quality of water or the sun's glow on the horizon, as in impressionist paintings (see also Livingstone, 2002 ).

Suggested additions

Finally, in regards to possible additions, besides those discussed above, the model is heavily influenced by both beauty and visual research, as well as philosophical ideas of (e.g., Kantian) disinterest (Vartanian and Nadal, 2007 ). While the emphasis on detached reception and visual pleasure may adhere to classical (pre-modern) art examples, it does not touch many aspects of modern art experience. Notably this includes a more robust or differentiated explanation for emotions, and negative evaluations. While the integrated nature of the model does allow for discussion of what brain areas may be tied to changes in perception/emotion, there is no explanation of the driving force that may bring these about. This is especially clear in Chatterjee's ( 2011 ) discussion of the evolutionary role of art. As he explains, focusing on liking or other aesthetic judgment as our sole focus would be maladaptive. If “the most profound …experiences involve a refined liking, often described as awe or feeling the sublime, in which wanting has been tossed aside, […and where] individuals lose themselves in the experience,” the individual would be rendered “vulnerable”—“Entering an aesthetic attitude is dangerous.” However, this does not take into account adaptations in the viewer. Most notably, we would recommend adding longitude changes (see box on far right), relating to making special or Social/Health . We would also suggest adding an indication of the “feed forward loop,” noted in the theoretical writing, and which appears to be placed between decision and attention stages, as well as contextual aspects such as perceiver and art qualities.

Locher et al.: early and intermediate visual processing

Locher et al. ( 2007 , 2010 ) also introduced a model, which deals with early/intermediate processing, primarily driven by empirical approaches to vision research. This model was conceived to describe the relationship between eye movements and scan patterns when processing visual art, 6 and takes a somewhat different approach to the model layout, centering on three overlapping elements. The “person context” relates to both the personality inputs and the internal processes of the viewer. “Artifact context” refers to the physical aspects of the art. The “interaction space” details the physical meeting of viewer and art, mainly pertaining to eye movement and other outputs regarding actions. For the purpose of unification with the other approaches, we have moved these inputs to the model's left side and moved the processing stages to the middle (Figure (Figure2 2 ).

Locher model (adapted from Locher, 1996 ; Locher et al., 2010 ) .

The model involves two processing stages: First, similar to Chatterjee and following previous theory regarding vision (Marr, 1982 ; Rasche and Koch, 2002 ), Locher et al. argue that art viewing, like other perception, begins with a rapid survey of the global content of the pictorial field producing an initial “gist” impression (e.g., Locher, 2015 ) of global structural organization, composition and semantic meaning. This processing alone can activate memories, lead to emotion, and contribute to a first impression/evaluation. The detected gist information and resulting impression then drive the second stage, involving a more focused period of attention on form and functionality. This stage also involves focus on details or specific aspects of pictorial features in order to satisfy cognitive curiosity and to develop aesthetic appreciation. Information is gathered by moving the eyes over art in a sequence of rapid jumps, followed by fixations.

The authors posit that interaction in the second stage is also driven by the “Central Executive” (blue box inside “person context”)—consisting of “effortful control processes that direct voluntary attention” in a top-down, cognitively driven manner (Locher et al., 2010 , p. 71). This also forms the “crucial interface” between perception, memory, attention, and action (depicted in the model's box labeled “spatio-temporal aspects of encoding”), and performs four important executive processes (following Baddeley, 2007 ): focusing, dividing, or switching attention, and providing a link between working and long-term memory. Thus there is argued to be a continuous, dynamic bottom-up/top-down interaction inside the Central Executive, involving assessed properties (form) and functionality of the object, and “viewer sensory-motor-perceptual” (i.e., visual) processes, as well as viewer cognitive structure. “Thus, as an aesthetic experience progresses, the artifact presents continually changing, ‘action driven’ affordances” (Locher et al., 2010 , p. 71). These “influence the timing, rhythm, flow, and feel of the interaction.” Ultimately, “together the top-down and bottom-up component processes underlying thought and action create both meaning and aesthetic quality,” defining art experience. Like many of the other authors, Locher et al. note both automatic and more deliberate processing. Especially in the first phase, many aspects specific to a work—complexity, symmetry, organizational balance—are argued to be detected “automatically or pre-attentively by genetically determined, hard-wired” mechanisms (p. 73).

The model especially involves focus on eye movements ( Action ). The authors' research—using eye tracking, as well as museum based observations and participant descriptions—specifically shows evidence for the initial gist processing, relating to a movement of the eyes over a large visual area and showing attention to elements perceived as compositional units (Locher et al., 2007 ; see also Locher and Nodine, 1987 ; Locher, 1996 ; Nodine and Krupinski, 2003 ). They also showed a later switch to focus on details as well as expressiveness and style/form elements. This also gives new evidence for discussion of Appraisal and Meaning -making, which can result from this sequential looking. They note that the stage of early processing can itself play an important role in these outcomes. Further, within their most recent model discussion, the authors classify three channels of information that one might create. These are composed of functional or conceptual information, inherent information (via affordances communicated in the object), and augmented information, presumably that which is changed or developed through viewing ( Novelty ). These outcomes would most likely come through directed looking in the second stage. The authors also note that emotion ( Affect ) may be evoked throughout the viewing process, however, they do not address how.

The model notably argues for “two driving forces”: the “artifact itself” and a “person context that reflects the user's cognitive structures” (Locher et al., 2010 , p. 72). With respect to the artwork, the authors (2010, p. 73) cite research (e.g., Creusen and Schoormans, 2005 ), which suggests “at least six ways” in which appearance influences evaluation and choice, including conveying aesthetic and symbolic value, providing quality impression, functional characteristics and ease of use, drawing attention via novelty, and communicating “ease of categorization.”

Regarding the viewer, the authors note that this input “contains several types of [acquired] information (semantic, episodic, and strategic),” and is also the “repository of one's personality, motivations, and emotional state,” all of which influence, in a top-down fashion, how viewers “perceive,” and “evaluate” (Locher et al., 2010 , p. 73). They note that this might play a role in the second phase, where memory “spontaneously activates subsets of featural and semantic information in the user's knowledge base,” including the user's level of aesthetic sophistication, experience, tastes, education, culture, and personality. In addition, they note that “individuals are capable of rapidly detecting and categorizing learned properties of a stimulus,” for example characteristics of the artistic style and a composition's pleasantness and interestingness. “These responses occur by a rapid and direct match in activated memory between the structural features of an art object…and a viewer's knowledge” (p. 76). They also suggest that emotion itself may be an input. Locher ( 2015 ) also suggests that expertise of a viewer may play a particularly important role in the initial gist impression as well. For example, experts may give more importance to the initial impression and resulting affective reaction when appraising value or authenticity of artworks.

Locher et al. ( 2010 ) furthermore note importance of context. This includes social-cultural and socio-economic factors related to the object, its historical significance, symbolic associations and social value. These “contribute to a user's self-perception of his or her cultural taste” or aspirations (p. 78). These aspects are also argued to influence art interaction in a cognitively-driven, top-down fashion. However, the actual tie to outcomes is not discussed. Other mentioned factors include the environment, available time for viewing, and previous mood or exposures. For example, they cite studies in which individuals were primed by giving candy, resulting in better mood, which positively influenced evaluations, attention to details, and more balanced patterns of eye movement.

An integration of the discussion of action/eye-movement with emotion or evaluations would be useful. The authors also tend to place most aspects within the second stage and do not explain how possible sequences or patterns might lead to certain outputs within experience, nor how experience changes. This may also be a result of the lack of defined temporal flow in the model design. Interestingly, when Locher et al. ( 2007 ) gave individuals the opportunity to verbalize their initial gist reaction (roughly the first seven seconds), they did not find changes in the way individuals described artworks after this period, raising questions regarding the present delineation between stage one and two. They also do not consider longitudinal aspects. Better explanation of “augmented information”—one of the three channels of information argued to be created from looking in stage two—might give a point of entry for this. Further, in their empirical support for the model and its outputs, they note that their artworks were created by renowned artists “and are, therefore, presumably visually right” (Locher et al., 2007 , p. 74). However, this raises the question of what makes a work “right,” and how less visually-successful art might be processed.

Leder et al.: intermediate stages and aesthetic appreciation and judgments

A model that has its strengths in linking early and late processing, with focus on intermediate stages, is that of Leder and colleagues (Leder et al., 2004 ; updated in Leder, 2013 ; Leder and Nadal, 2014 ). This has also become perhaps the most prominent approach for empirical study (Vartanian and Nadal, 2007 ).

Based largely on the cognitive work of Kreitler, Kreitler, and Berlyne above (Leder et al., 2005 ), their model considers art experience as a series of information-processing stages, focusing largely on perceptual attunement to various formal factors in art. However, it also integrates this sensory information with “conceptual and abstracted” meaning (p. 12) as well as emotion and body responses. As shown in Figure Figure3, 3 , after an initial pre-classification (most presumably regarding situational context), the model proposes five stages (Leder et al., 2004 ), occurring in sequence: (1) “perceptual analysis,” where an object is initially subjected to analysis of low-level visual features (e.g., shape, contrast); followed by (2) “implicit memory integration,” in which art is processed via previous experiences, expertise, and particular schema held by the viewer. This is followed by (3) an “explicit classification,” where one attunes to conceptual or formal/artistic factors, such as content and style, and (4) “cognitive mastering,” in which one creates and/or discovers meaning by making interpretations, associations, and links to existing knowledge. The process ends in (5) a stage of “evaluation,” where processing outcomes combine, culminating in both aesthetic judgment and the potential for “aesthetic emotions.” The model also makes a distinction between “explicit” and “implicit” processing (see timeline), with the first two (or possibly three) stages occurring automatically or with little conscious awareness (Tinio, 2013 ). In latter stages, there is then a component of self-aware or self-referential processing, where the perceiver “evaluates his affective state and uses this information to stop the processing once a satisfactory state is achieved” (Leder et al., 2004 , p. 502).

Leder model (adapted from Leder et al., 2004 ; Leder and Nadal, 2014 ) .

This model offers a number of advancements from previous work. Because all stages feed into a continuously updated state (Leder et al., 2004 ), it affords a more holistic understanding of how one comes to evaluations or responses. In addition it incorporates a number of factors—emotion, viewer experience, and formal aspects of artworks—to these stages, which partially influence final results. Thus, the model can be used for both a top-down, mechanism-based evaluation of the general processing of art, or for bottom-up, experience-based testing of hypotheses for specific sequences that may inform particular varieties of response (Vartanian and Nadal, 2007 ). Because of its emphasis on fundamental cognitive mechanisms, the model has also been used in a number of areas outside art—e.g., design, dance, and music (Leder, 2013 for review).

Primarily, this model proposes two outputs—aesthetic Appraisal and Affect . These are mainly explained as a result of successful visual/cognitive processing. The authors claim that part of the pleasure derived from looking is the feeling of having grasped the meaning, thus understanding an artwork results in reward-related brain activation. Looking at Figure Figure3, 3 , emotion or assessment come about by moving through each stage, especially “cognitive mastery,” to a successful end. This argument is in keeping with a number of approaches—most notably Berlyne's concept of curiosity/interest and Bartlett's ( 1932 ) ( 1932 ; see Belke et al., 2010 ) “effort after meaning”—which stress importance of intellectual engagement or understanding as core dimensions of positive response. The model also notes meaning-making (Meaning) , suggesting that this comes through classification and implicit memory integration in which one connects a specific work to an interpretation. Finally, the model accounts for profound or Aesthetic experience. This is argued to derive from the natural extrapolation of the cognitive mastery process, whereby the more completely one can master a work, the more harmonious and pleasurable the outcome, occasionally to the extent that one experiences a pleasurable, “flow”-type experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990 ; Leder et al., 2004 ).

The model also mentions several inputs (left side, Figure Figure1). 1 ). Primarily, the stages of implicit memory integration and explicit classification are argued to be influenced by previous art experience—determining whether one first sees, for example, a “post-impressionist work,” a “sunflower,” or a “Van Gogh” (Belke et al., 2010 ). Previous experience or expertise also impact assessments of prototypicality and fluency within the second stage—which influence positive/negative emotions and evaluations (Leder et al., 2004 , 2005 ). Explicit classification also involves processing of style and content, driven by personal viewer characteristics such as knowledge and taste (Leder et al., 2005 ; also Hager et al., 2012 ) and understanding of art historical context (e.g., see Bullot and Reber, 2013 ). More recently, an updated discussion of the model in regards to emotion (Leder et al., 2015 ) suggested that the switch between aesthetic or more pragmatic approaches in “explicit classification” may be driven by a check of one's desires for emotion or mood state. In cognitive mastering, where meaning is extracted, lay persons may also be more likely to draw on self-related interpretations like feelings, personal memories, or experience, while experts may rely more on art-specific style or concepts (Augustin and Leder, 2006 ; Hager et al., 2012 , p. 321). Leder ( 2013 ) extends this even to classifying objects as “Art.” He notes that top-down classification before the actual episode, may affect experience by engaging an aesthetic mode, regulating hedonic expectations, and thus modulating intensity of emotion or interest.

In regards to the actual outcome of viewing art, the exact relation of specific emotions or evaluations to certain given inputs largely remains unclear. As also noted by Leder ( 2013 ), there is need of a more integrated explanation of how emotion or other physiological responses might tie to processing experience. While the model notes the role of personality and experience as a driver of outcomes, and the specific stages where self components may have an impact, it does not consider how these aspects are actually integrated or acted upon within psychological experience (see also Silvia below) 7 . There is also need for more explanation of how art-viewing can alter perceptions or understanding within experience (Novelty, Transcendence, Self Adjustment). While acknowledging potential for such results, it remains unclear what must happen within specific encounters for a change of the next viewing moment or the next experience. Presumably, the process might follow our additions (far right: Figure Figure3), 3 ), where specific mastery in one encounter (or even within one stage), mediated by positive feedback or emotion/evaluation, would allow one to add to memories/experiences, which would then modify the self. A related output might also be posited for art's longitudinal impacts (Social, Health).

Another issue involves disruptions. Recent work by Leder's group (Jakesch and Leder, 2009 ) has shown the importance of ambiguity or breakdowns in the mastery process. This is displayed in the “evaluation” stage, and may create a more intense experience by causing one to undergo another loop of the model. However, the specifics of how these arise and create intense vs., for example, negative reactions could be more fully addressed. As it stands, the model appears to afford only a one-way mechanism for improving mastery, which leads to pleasurable experience. This raises the question of how one overcomes difficulty or finds new interpretations (Leder, 2013 ). The model has also not been connected to specific negative outcomes or physical action. These could presumably be placed as one more component of affective state (bottom).

The late stages: Silvia et al.: appraisal theory and emotion with art

Several approaches also expand past the models above to consider in more detail later processing elements. First, the work of Silvia (e.g., Silvia, 2005a , b ) specifically builds on the ideas of Leder, emphasizing information processing and visual art. However, Silvia's approach focuses on the mechanisms for arriving at specific emotions and artwork assessments, while it simultaneously questions previous psychobiological, prototypicality, and processing fluency approaches.

Silvia (Silvia and Brown, 2007 ) argues that past processing theories had two major limitations: First, their use of fluency or typicality as a main determinate of positive or negative reactions leads to difficulties in explaining why specific emotions would arise beyond this basic affect. Specifically, previous theories could not discriminate between emotions. At best, they proposed an undifferentiated feeling of aversion or interest. Second, reactions to works could be both positive or negative, but this would depend on other contextual factors such as personality rather than just ability to fluently process. Further, it is especially “hard to derive” what feelings arise from not-fluent or non-prototypical interactions with art (Reber et al., 2004 ). In response, Silvia proposed an approach based in appraisal theory (e.g., Scherer et al., 2006 ) that connects reactions with the personal relationship between viewer and art. He argues that each emotion has a distinct appraisal structure or set of evaluations that evoke the response. These evaluations are inherently contextual and subjective, with the central assumption being that evaluations, not the object, are the local cause of experience.

As shown in Figure Figure4, 4 , where we have produced a model based on his arguments, Silvia proposes that responses can be broken into two main components: (1) There is a “novelty check” (Silvia, 2005a , p. 122), which is connected to processing of “collative” factors (following Berlyne)—referring to the relative understandability, interestingness or uniqueness of art. This is also tied to the matching of object to the existing schema or expectations of the viewer, and might be further divided into both basic “congruence” and the relevance that the object or the act of matching has to one's goals or self (Silvia and Brown, 2007 ), with the output being a feeling of relative ease and understanding. (2) There is also “coping potential,” or estimate of relative control or efficacy within the situation itself (Silvia, 2005a ). Throughout his writing, he also includes a third factor, relating to (3) relative importance of the object/situation to the self.

Silvia model (created by the authors for this paper) .

For example, in the case of interest (Silvia, 2005a , 2006 ), the appraisal structure would consist of: (1) a judgment of high novelty/complexity (i.e., low schema congruence), combined with (2) high coping potential, and (3) low self relevance or little importance for one's goals or expectations and thus low perceived threat. In contrast, anger (Cooper and Silvia, 2009 ) would combine appraising an event as (1) inconsistent with one's schema (low schema congruence), but also (2) with low coping potential (e.g., as action beyond one's control) and (3) closely tied to one's goals/self. Because of this structure, Silvia concludes that in any situation, different people will have different responses to these processing checks, and thus different emotions to the same stimulus, or the same person may even have different emotions depending on context (Silvia, 2005a ). Like Leder, Silvia also emphasizes that responses need not require overt awareness.

This model also makes an important contribution, especially regarding art impact. The two main outcomes, as in the above models, are Affect and Appraisal . Silvia however adds to the previous models by proposing pathways for specific reactions (Silvia and Warburton, 2006 ), giving a frame for empirical assessment of experience. By assessing the processing checks noted above, typically via Likert-type assessments, 8 the model can explain why people have different emotions to the same event, and why different personality traits, skills, and values can predict responses (Silvia and Brown, 2007 ). This also enables movement beyond simple pleasure and preference, to surprise, confusion (Silvia and Nusbaum, 2011 ) as well as Negative responses such as anger, disgust, contempt (Silvia, 2009 ). As shown in Figure Figure5, 5 , these are specifically explained as arising from low congruency and differences in relative coping and self relevance. Beyond emotion, Silvia also groups outputs into clusters (Cooper and Silvia, 2009 , p. 111), noting that appraisal theories “are componential theories,” which include facial, vocal, postural expressions or other Actions , as well as Physiological response.

Pelowski model (adapted from Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 ) .

The model also posits categories of responses that specifically tie to different self-art relations. He notes “knowledge emotions” (interest, confusion, surprise), which are tied to intellectual matching of stimuli to schema, typically in high coping contexts. “Hostile emotions” (anger, disgust, contempt), hinge on threat to goals/self. “Self-conscious” emotions (pride, shame, embarrassment) tie to appraising events as congruent or incongruent with one's goals, and are also viewed as being caused by oneself rather than external events (Silvia, 2009 ). In the knowledge emotion category, Silvia (2009, p. 49) also notes the role of meta-cognitive reflection on the self. These emotions “stem from people's appraisals of what they know, what they expect to happen, and what they think they can learn and understand.” With self-conscious emotions, “to experience feelings like pride, shame, guilt, regret…[we] must have a sense of self and the ability to reflect upon what the self has done” (p. 50). In both cases this reflection might act as a conduit to Adjustment /learning and/or creation of Meaning . Especially knowledge emotions may “motivate learning, thinking, and exploring, actions that foster the growth of knowledge” (Silvia, 2006 , p. 140), and would come about as an output of one model cycle. It is also presumably through the earlier matching of schema to art—or rather in mismatches, paired with acceptable levels of coping/relevance—that one encounters Novelty or changed perception.

In the discussion of hostile emotional responses, the role of the self relates to attack on identity or schema. Responses stem from a “deliberate trespass” (Silvia, 2009 , p. 49) against one's goals/values. These responses are tied to action that is often given as a means of maintaining or protecting the self, motivating aggression and self-assertion (Silvia, 2009 ). Finally, he notes potential longitudinal impact ( Self Adj .), claiming “a consistent finding …is that training in art affects people's emotional responses…[and] changes people's emotional responses by changing how they think about art” (Silvia, 2006 , p. 140). He links this especially to knowledge emotions experienced in the art processing experience.

Silvia also explicitly connects responses with inputs, specifically personality. He notes that perhaps the most important aspect is how events relate to important goals or values (Silvia and Brown, 2007 ). This was empirically considered, for example, in his finding of changes in correlation between complexity/coping and interest depending on other individual personality factors (Silvia, 2005a ). Elsewhere, in a study on chills and absorption, Silvia found that people high in “openness to experience” as well as art expertise reported more such responses (Silvia and Nusbaum, 2011 , p. 208).

Adjustments

Questions remain, especially regarding the ordering of the three assessment checks. Specifically, while previous writing tends to present them with only a rough order, one could argue that this would most likely not be the case. One might question whether there is a primacy of assessment for either schema congruence or self relevance. It could be argued that with low relevance, the outcome of the congruence check has little meaning. On the other hand, individuals may be predisposed to constant checks of congruence, relating to basic processing or self-preservation, and thus this assessment may often come first. Another question regards when and how we reflect on our experience. While Silvia does explain reactions in terms of self-related assessments, he does not detail exactly what kind of mechanism this would require. This is most clear in discussion of hostile reactions. Arguing against prior fluency or prototypicality approaches, Cooper and Silvia (2009, p. 113) claim “it seems unlikely” that people have hostile reactions to art “because they find it insufficiently pleasing, prototypical, meaningful.” Instead, “people appraise art in ways that evoke hostile emotions, …in short, some art makes some people mad.” However, this argument is rather circular. Therefore, it would be useful to go one step further, and visually articulate—within a model— why this might be so at the individual level. Similar discussions could also be made of specific actions or body responses. His approach also does not divide between automatic and more reflective experience. This question, he notes is “an intriguing, cutting-edge area of appraisal research” (Silvia, 2005b , p. 6). While noting that we might be changed from our experience and that emotional responses may change throughout art exposure, there is no explanation of how this might develop within experience itself (Silvia, 2006 ).

Pelowski et al.: discrepant and transformative reactions to art

The model of Pelowski (Pelowski and Akiba, 2009 , 2011 ) was also conceived as an extension of the Leder approach, with the addition of some appraisal theory elements, and attempts to refocus on the specific discussion of changes or evolutions in responses within the art interaction experience.

Pelowski et al. argue against a typical emphasis on harmony, fluency, or immediate understanding, and instead advocate a more labored process of discrepancy and subsequent adjustment. Pelowski and Akiba ( 2011 ) note that many past discussions of art experience—both theoretical and anecdotal—involve some means of disruption or break from the flow of everyday life experience. It is these untypical reactions that are argued to actually constitute the impact and importance of art, acting to disrupt a viewer's pre-expectations and forcing upon them a new means of perception or insight (see also Pelowski et al., 2012 ; Muth et al., 2015 for similar argument). Yet, these very qualities are often eliminated from the study of art perception. They further argue that models have come to “equate art perception to either an emotional/empathic alignment of viewer to artist or artwork” or to a cognitive “assessment of an artwork's …information” via matching of schema to the object of perception, leaving models “without a means of accounting for fundamental change within art experience” (Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 , p. 82). Like Silvia, they also argue that current approaches cannot describe how individuals arrive at specific reactions, limiting researchers' ability to unite cognitive, emotional, and evaluative reactions within experience.

Their model (Figure (Figure5) 5 ) posits five stages, beginning with a specific conception of expectations or viewer identity. Pelowski and Akiba ( 2011 , p. 87) argues that viewers carry “fundamental meanings regarding themselves, other persons, objects, or behaviors—‘Who am I?’ ‘What is art?’ ‘How does art relate to me?”’ which collectively combine to form what they refer to as the “ideal self image.” Updating previous work by Carver ( 1996 ), Pelowski and Akiba ( 2011 ) specifically posit a theoretical construction for this self, which can be considered as a hierarchical pyramid with core traits (“be goals”) at the top, and branching down to expectations for general actions (“do goals”), and further subdivided into more specific schema. Through connection of low-level schema to core ideas of the self, all action (such as viewing art) then involves application of this structure. This occurs in tandem with human drives to protect the self image, through cognitive filters that lead attention away from potentially damaging information. Thus “success or failure in perception, as well as what individuals can [initially] perceive or understand, are a result of this postulate system” (pp. 85–87), and provide the mechanism for understanding reaction to art.

The authors then propose three main outcomes. First, individuals attempt to successfully match schema to art by classifying and understanding, coinciding with the “cognitive mastery” in the Leder model. They also acknowledge that this outcome is a general goal of most experience, and may induce pleasure, harmony, or even flow-type states. However, because this outcome marks a matching of schema to perception, mastery also would coincide with a “facile” reaction to art, reinforcing previous expectations and cutting off possibility for new perception or insight. Moving past this point, they argue, requires some “discrepancy” within experience. This can involve any number of aspects—e.g., between expectations for perception and art, between meaning and prior concepts, between bodily reactions and expectations for how one should act. In each case discrepancy acts to “bump” an individual out of their preconceived frame (Pelowski et al., 2014 , p. 4), forcing response or adjustment.

Upon discrepancy, the model then posits that individuals move to a “secondary control” stage in which they try to diminish or escape from the discrepant element. This is accompanied by actions—e.g., re-classifying art as bad or meaningless, diminishing importance of the encounter, or physically moving away—which avoid a questioning of higher-order aspects of the self image, and also explain the negative emotional or evaluative experiences sometimes had with art. On the other hand, if viewers persist, they may instead eventually alter their own schema in order to better approach the art. This is argued to be most likely when art-viewing has a fundamental tie to the self (representing a higher order goal) and one cannot easily escape (Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 ). This change also coincides with a shift from direct perception to a more meta-cognitive perspective, in which viewers give up previous attempts at control, acknowledge discrepancy, and eventually create new schema for viewing the art. They conclude that it is this process whereby one “transforms” the self, that can be connected to change, novelty, or insight, and coincides with highly positive emotion, and deepened or harmonious engagement.

This model is especially important for explaining both highly positive ( Aesthetic ), and Negative , as well as insightful or Novel and Transcendent reactions. The model also unites these within one progressive experience. It is argued that in order to arrive at the final outcome a viewer moves through all antecedent stages (Pelowski et al., 2012 ). In this vein, one of the model's key benefits is its division into specific stages, tied to application, protection or adjustment of the self. Thus the authors can attach general theory regarding various reactions noted for each of these events (see also Leder, 2013 ). Notably, they suggest emotion or Affect , which, following Silvia, would arise in specific clusters depending on the positive or negative experience of applying the self. They argue that empirical analysis of viewing art would be expected to show a progression from no emotion in the facile stage, to confusion, anxiety, and tension, followed by anger in secondary control, and finally self-awareness, epiphany, or happiness in the aesthetic stage. This division has also been supported by recent empirical evidence (Pelowski et al., 2012 ; Pelowski, 2015 ). Similar results are also tied to Physiology , specifically heart rate and skin conductance. They argue that the first stage should show little physiological response, while secondary control would lead to sympathetic (fight or flight), schema change to both parasympathetic and sympathetic, and the final stage to parasympathetic return to homeostasis. This final outcome was also recently tied to crying (Pelowski, 2015 ). They also suggest specific Action (need to leave) in the “secondary control” stage.

Regarding Appraisal , they also argue that evaluation ending in cognitive mastery may reveal appraisals that aid in ignoring or assimilating discrepancy (Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 ). On the other hand, in secondary control, self-protectionary strategies would manifest in negative hedonic appraisals, as well as lower “potency or activity” (e.g., Osgood et al., 1957 ). They further consider Meaning , dividing outcomes into three modes: (1) initial assessment for surface or mimetic qualities in cognitive mastery, (2) meaninglessness in secondary control, and (3) “a fundamental change in viewer-stimuli relation” in the last stages, where art meaning is tied to metacognitive reflection on its impact and the preceding psychological experience (Pelowski et al., 2012 , p. 249).

The model is also particularly unique in its explanation of changes or transformation with art. Recently, Pelowski et al. ( 2014 ) connected this outcome to goals of museum/art education, and pointed out its equivalence to discussions of insight or creativity. By breaking from the mastery process through the introduction of meta-cognitive assessment and schema-change, followed by re-engaging in final mastery with a new set of schema, they argue, “we introduce a means of explaining the transcendental quality of art” and of “connecting the existing conception of mastery to …novelty and personal growth” (Pelowski and Akiba, 2011 , p. 90). They also posit longitudinal impact, tied to changes in schema or the “hierarchical self.” Especially the aesthetic outcome may manifest in re-evaluation of a viewer's own self image, which may be detectible in paired self-evaluations before and after viewing ( Self Adj .). They also argue that both the abortive or transformative outcome may cause change in individual's relationship with the class of art or artists, involving hedonic and potency evaluations ( Social ), and may spur individuals to seek out/avoid other encounters.

Regarding inputs, the model considers the role of specific expectations or personality, and goes further to place these within a theory of the self. The authors note that “those who have a strong relationship to a stimulus, or high expectations for success…are [more] likely to find themselves in the intractable position” leading to aesthetic experience (Pelowski et al., 2012 , pp. 246–247). This might be tied to training in the arts, or might affect those who identify as art lovers, who have a high need to find meaning in artworks, or who have the general need for control. More recently, the authors have also taken into account the physical and social situation, noting that the environment, especially when one is among others who one considers more knowledgeable, may be likely to evoke facile or negative experience, tying to a need for protecting the self (Pelowski et al., 2014 ).

At the same time, the model has a conceptual focus, laying emphasis on schema and overlooking much of the way individuals might often respond to art (basic perceptions, mimetic evaluations, or pre-reflective experience). A recent review (Leder, 2013 ) also noted that it is “more descriptive than formalized,” requiring transformation into “more operative versions with process-based rules,” quantifying what feature of a representation at one stage affects latter stages.

Cupchik: detached/aesthetic and pragmatic approaches to art

Finally, the theories of Cupchik have also not yet been placed into a unified model, but have individually been instrumental in empirical art research. These also involve several themes which can be connected to form an understanding of art experience, 9 and thus were deemed an ideal target for this paper (Figure (Figure6 6 ).

Cupchik model (created by the authors for this paper) .

Similar to other cognitive approaches, Cupchik views art experience as a meeting of object, environment, and personality factors (Cupchik and Gignac, 2007 ). In order to understand their interaction, a main theme regards two modes of responses (Cupchik, 2011 , p. 321): “everyday pragmatic” and “aesthetic.” The way that these modes are integrated, and often which of the two the viewer employs, determine the outcomes of experience. The pragmatic involves a predominantly cognitive, schema-based assessment, in which one assesses meaning and significance. The “aesthetic,” on the other hand, involves integrating context, memory, and physical/sensory qualities “associated with style and symbolic information” (p. 321). This involves a more reactive or “holistic” appraisal “in which specific codes for interpreting are bound with affective responses that map onto dimensions of pleasure or arousal.” Cupchik ( 2006 , 2013 ) also posits an alternative naming for this division, suggesting a contrast between “subjective engagement” and “objective detachment.” While subjective engagement is based on intense personal responses, objective detachment reflects a more intellectual treatment 10 .

In engaging art, one may switch between modes in response to different information or one's processing experience. Cupchik ( 2011 , 2013 ) notes that the two modes' “extreme conditions” can also lead to unwanted experience. This would involve either “underdistancing,” in which subject matter reminds us of troubling aspects of our personal lives, or causes unwanted emotion, or “overdistancing,” when design aspects push one too far away (as in some avant-garde art), with little emotional involvement (Kemp and Cupchik, 2007 ). The most pleasant responses may occur when individuals find an “aesthetic middle” (Fechner, 1978 ) between absorption and detachment—“utmost decrease of distance without its disappearance” (Cupchik, 2006 , p. 217). Cupchik ( 2013 ) also argued that one appeal of art is the opportunity at reconciliation between modes. While he argues that it is not possible to be in both modes at the same time, we can “shift rapidly between the two” (2011, p. 321). Thus, it is “the capacity of a work of art to be grasped, elaborated, and experienced in several systems” that makes it compelling (p. 294).

The model can further be articulated through its discussion of outputs. First is its discussion of Appraisal , which it connects to the aesthetic or reactive mode. Cupchik notes potential for Meaning making , via reflective and/or pragmatic processing. Affect is also noted. In an earlier publication, Cupchik ( 1993 , p. 179) suggested that two kinds of emotional processes might in fact be distinguished, which would coincide with either the analytical/schema-based or holistic/experiential processing modes. These can be termed “dimensional” and “category” reactions. The former are closely tied to bodily states of pleasure/arousal caused by a particular stimulus. The latter pertain “to primary emotions,” such as happiness, interest, surprise, fear, anger, and emphasizing spontaneity or empathic reaction to art. More recently, Cupchik ( 2011 , p. 321) suggested that the former affect type may accompany aesthetic experiences “from the first moment of perception,” giving as evidence studies involving displaying artworks of differing complexities or affective contents for very short durations, and where participants would avoid a second viewing based on their ability to detect lack of order or unwanted emotional valence 11 . In turn, the primary emotions are associated with longer exposure durations “that enable a person to situate the work in the context of life experiences” (Cupchik and Gignac, 2007 ). He also notes that this often touches the reflective mode of appraising, which is more closely related to emotions linked to the self (Cupchik, 2011 ). He suggests that both cases may lead to Negative affect. This would come from either: (1) difficulty in initially processing art, leading to hedonic aversion through the reactive/aesthetic mode, (2) “under-distancing,” where the work is too close to one's self and/or a troubling situation, or (3) negatively perceived content in art as processed in the reflective mode.