The Dark Psychology of Serial Killers: Unpacking the Factors Behind their Brutal Behaviour

Serial killers have long captivated the public’s imagination with their shocking and senseless acts of violence. But what drives individuals to commit such heinous crimes? In an effort to answer this question, psychologists and criminologists have been exploring the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors that can contribute to the development of a serial killer.

While there is no one-size-fits-all explanation for why someone becomes a serial killer, research has shed light on several key factors that can increase the likelihood of violent behaviour.

One of the most well-known biological factors is brain structure and chemistry. Studies have shown that a malfunctioning amygdala , the region of the brain responsible for regulating emotions and aggression, may be involved in the development of violent behaviour. Additionally, low levels of serotonin , a neurotransmitter that regulates mood, have also been linked to impulsive and violent behaviour. This means that a serial killer’s brain structure and chemistry can play a significant role in their behaviour, leading to an increased likelihood of violence.

Childhood abuse and trauma are also important factors in the development of serial killers. Childhood abuse can have lasting effects on an individual’s mental and emotional health, and research has suggested that individuals who experienced childhood abuse are more likely to engage in violent behaviour compared to those who did not experience abuse. In some cases, this abuse can lead to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which can further increase the likelihood of violent behaviour.

Personality disorders also play a role in the development of serial killers. Serial killers often display a range of personality disorders, including antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), narcissistic personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder .

ASPD, in particular, is characterised by a lack of empathy and a willingness to engage in criminal behaviour, making it a key factor in the development of serial killers. These personality disorders can lead individuals to become detached from reality and engage in violent behaviour.

Social and environmental factors also play a role in the development of serial killers. Growing up in dysfunctional families or communities where violence is common can increase the likelihood of violent behaviour. Exposure to violent media, such as films and video games, has also been linked to an increased likelihood of violent behaviour. This exposure can desensitise individuals to violence and normalise it in their minds, leading to an increased likelihood of violent behaviour.

The psychology of serial killers is complex and multifaceted, and it is unlikely that any one factor can fully explain why someone becomes a serial killer. Instead, it is likely that a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors contribute to the development of violent behaviour.

A 2022 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health explored the psychological profiles of serial killers and found that they often share several key characteristics. These include a lack of empathy, a history of childhood abuse and trauma, a desire for control, and a fascination with death and violence. The study also found that serial killers often display traits of both psychopathy and sadism, suggesting that these two personality disorders may be key factors in the development of serial killers.

A 2005 study published in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology looked at the role of childhood abuse in the development of serial killers. The study found that childhood abuse is a strong predictor of violent behaviour and can have lasting effects on an individual’s mental and emotional health. The study also found that individuals who experienced childhood abuse are more likely to engage in violent behaviour, including serial murder.

Knowing what makes a serial killer tick is crucial in stopping them from striking again. Researchers are diving into the mix of biological, psychological, and social factors to figure out why some people feel the urge to kill multiple times. This understanding can then be used to create better prevention strategies and help with future investigations.

Finding out why serial killers do what they do can also bring comfort to victims’ families and help society tackle violent crime in a more complete way. The study of serial killer psychology is ongoing and full of new discoveries. By looking into the complicated nature of serial murder, researchers are working towards a world without these horrible crimes.

Dennis Relojo-Howell is the managing director of Psychreg.

VIEW AUTHOR’S PROFILE

Related Articles

I love the west, but sometimes i hate their hypocrisy, the uplifting power of communities, the psychology of fashion – how our choice of clothing reflects and shapes our identity, the evolution of the escort business and changing perceptions, collecting feedback on your government surveys, new report reveals 10 most dangerous uk cities for pedestrians, shielding rights: the work of an arizona criminal defence lawyer, the dei fatigue: rethinking the approach to diversity and inclusion efforts, moral heroes and underdogs win our hearts in fiction, finds new study, study reveals lower volunteering in diverse us states – trust key factor, the type of white normativity that activists convieniently ignore, how animal cruelty images on social media affect our mental well-being, observing how repeated social injustice can significantly impact mental well-being, digital media fuels jihadist radicalisation in australia, finds study, study shows social media’s influence on islamist militancy among bangladeshi youth, new book offers in-depth exploration of forensic psychology’s role in legal systems, new study reveals how depression influences political attitudes, a guide to using the insanity defence in a criminal trial, study finds shaky connection between moral foundations and moral attitudes, study shows vaccination alters body odour and facial attractiveness, resolve to be greener: seven easy, small steps freelancers and sole traders can take to be more sustainable in 2024, “they don’t like you because you’re black” – injecting racial poison into children’s minds, police are not hunting black boys, texan philanthropists appointed honorary fellows of the oxford centre for animal ethics.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

Why are there fewer serial killers now than there used to be?

- Search Search

Looking at the most-streamed movies or television shows on any given streaming service, it would be easy to assume that serial killers lurk behind every corner. The stories of Jeffrey Dahmer, Ted Bundy and the Boston Strangler still loom large––even if the likelihood that you’ll encounter another Zodiac Killer has never been lower.

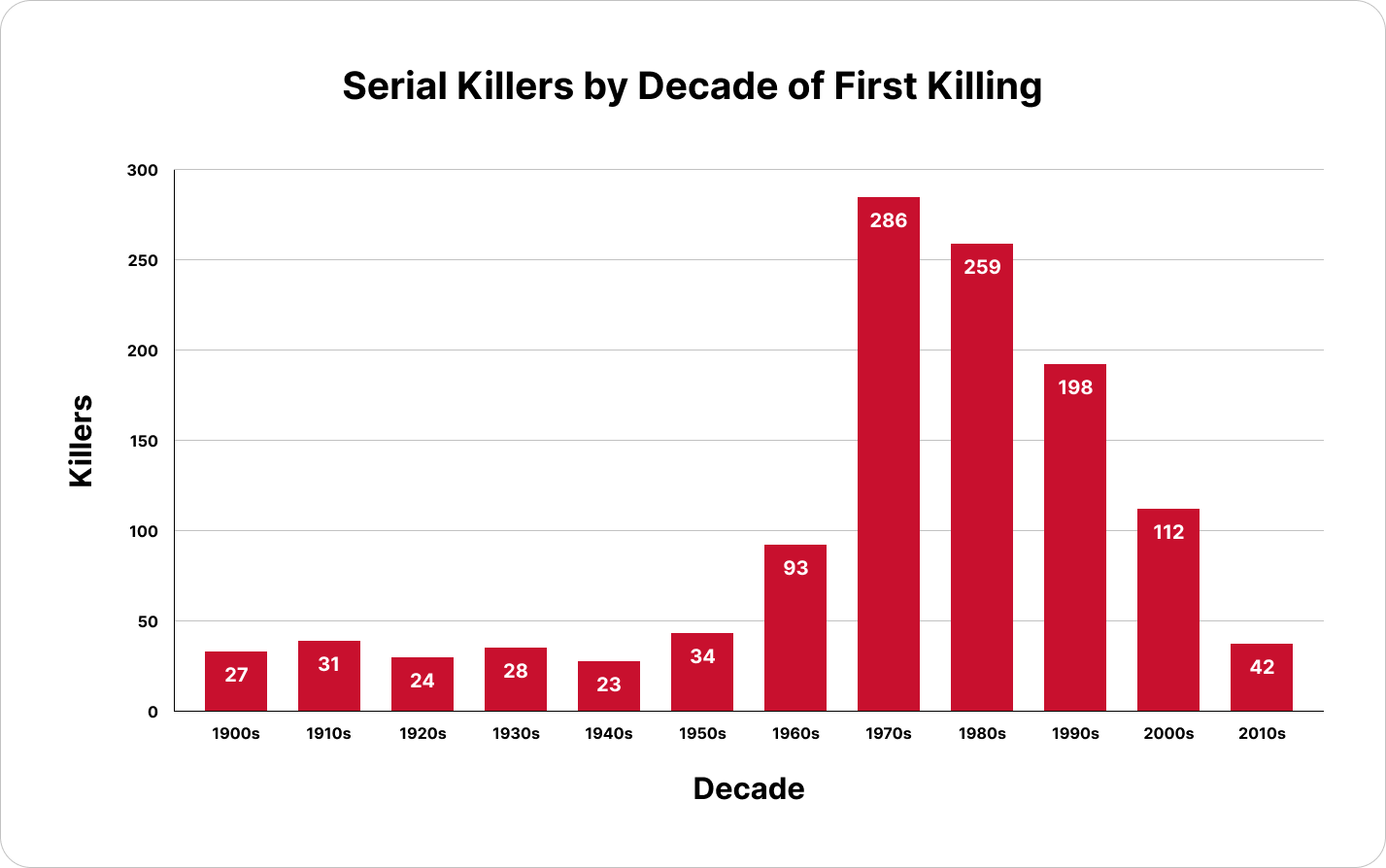

Since the 1970s and 1980s, a high activity period for serial murderers, the numbers have dropped significantly. Numbers peaked in the 1970s when there were nearly 300 known active serial killers in the U.S. In the 1980s, there were more than 250 active killers who accounted for between 120 and 180 deaths per year. By the time the 2010s rolled around there were fewer than 50 known active killers.

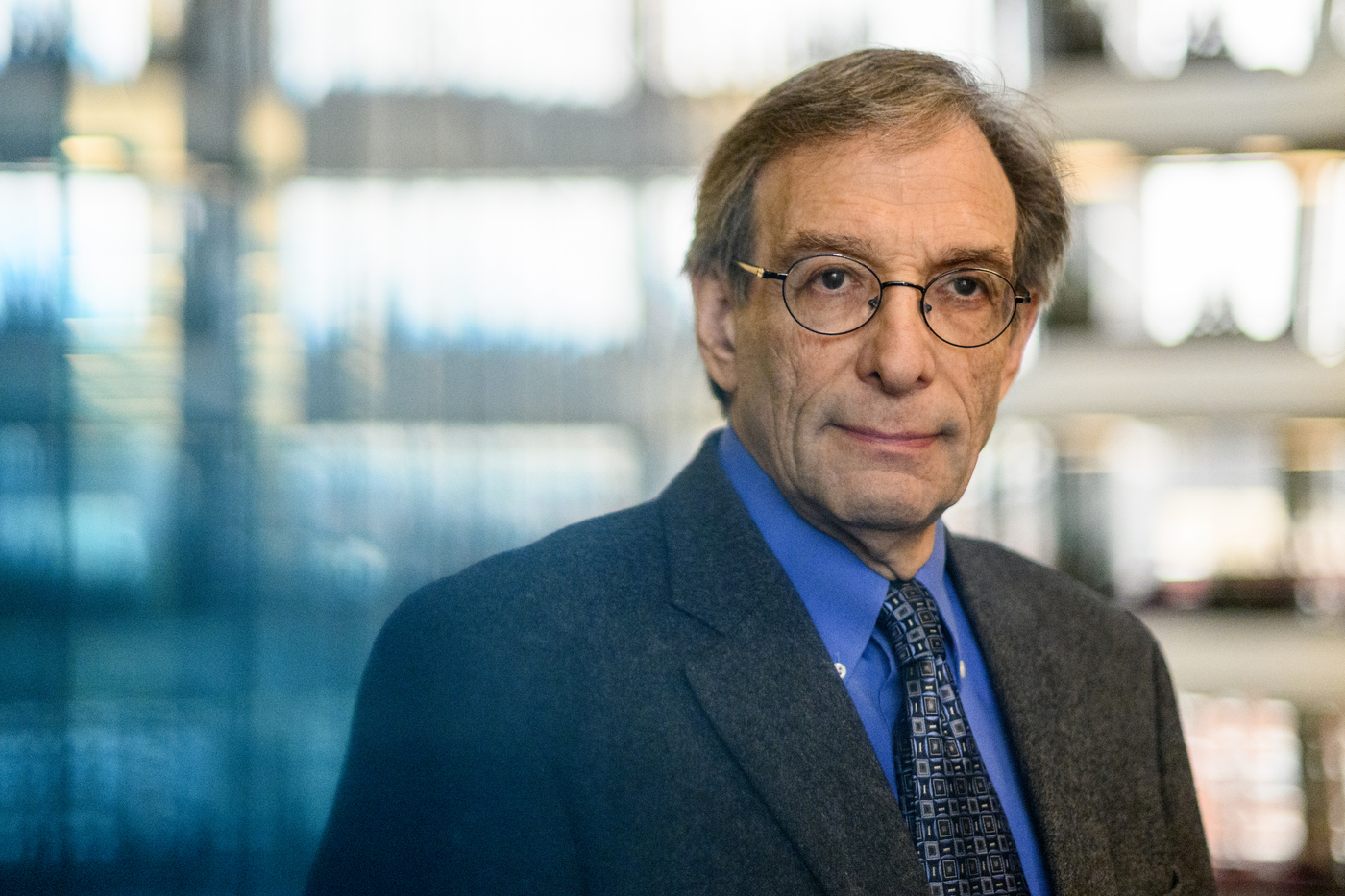

This data is based on numbers from the Radford University/Florida Gulf Coast University Serial Killer Database that have been further analyzed, combed through and published in the recently-updated “Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder” by James Alan Fox , Jack Levin , Emma Fridel.

But what accounts for this dramatic decrease over the last 40 years?

According to Fox, a criminology professor at Northeastern University, it comes down to several major changes in forensic science, policing, criminal justice and technology that have made it harder than ever for the BTK Killers of the world to escape capture.

Northeastern Global News, in your inbox.

Sign up for NGN’s daily newsletter for news, discovery and analysis from around the world.

The decline that started in the 1980s mirrors a decrease in a nationwide crackdown on crime that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s made it difficult for serial killers, let alone anyone involved in violent crime, to stay out of prison.

“Part of it has to do with the same reason the murder rate has gone down,” Fox says. “You have a surging number of people behind bars, so some of the would-be serial killers were likely behind bars as opposed to in the bars looking for victims.”

Between 1980 and 1992, the incarceration rate in federal and state prisons more than doubled to 332 per 100,000 U.S. residents, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics .

Advances in forensic science and DNA testing have also made it possible for police to more effectively investigate murders, even those that have remained open or questionable for decades .

“The first case I was involved with in 1990, I was on a task force investigating the murders of five college students,” Fox says. “We had DNA, but it was pretty crude. We couldn’t get DNA from hair––now you can. You needed a lot of genetic material to be able to identify the DNA pattern––now you don’t.”

Forensic genealogy , recently used in the case of suspected quadruple murderer Bryan Kohlberger, has even made it possible to test DNA collected at a crime scene against DNA collected from a suspect’s family.

And serial killers can leave a digital fingerprint too. Fox says the proliferation of surveillance cameras and the advent of the cellphone with its GPS tracking capabilities have made it harder for serial killers to abduct their victims in the first place. Investigators also have even more tools at their disposal to track a killer’s whereabouts, whether it’s an IP address or, in the case of the BTK Killer , the metadata off of a floppy disk.

Fox also attributes the decrease in serial killers to changing behaviors among the public as well. With widespread social and cultural changes in the 60s and 70s––drug use, hitchhiking, the hippie movement, anti-establishment sentiment––conditions were prime for predators to go on the prowl, Fox says.

@northeasternglobalnews The chances of you encountering someone from Mindhunter has never been lower, research suggests. Why? #Northeastern criminology professor James Alan Fox points to several factors, including parenting styles and advanced technology, contributing to this decrease. #TrueCrime #TrueCrimeTikTok #DeepDive ♬ Spooky, quiet, scary atmosphere piano songs – Skittlegirl Sound

But things have changed in the last few decades. Fears around mass killings have increased, as has the public’s general anxiety and distrust for one another . People are “much more aware and cautious than we used to be” and might be less likely to accept help from a stranger who says they just want to help you fix your flat tire .

Changes in how parents think about their children’s safety also mean some of the most common targets for serial killers, young women and girls, are less vulnerable than in decades past. According to Fox, Levin and Fridel, of the 5,582 victims killed by serial killers since 1970, more than half are female. About 30.2% of those female victims are between the ages of 20 and 29 and 23% are between the ages of 5 and 19.

Laurie Kramer , a professor of applied psychology at Northeastern, says many parents now feel like the world is a “more dangerous and risky” place, even at school , places they previously assumed were “risk free.”

“There is that sense that parents need to be much more participatory and intentional about selecting those opportunities in which their kids are going to be beyond school and church or other sorts of things that are pretty normative for them,” Kramer says. “There’s just a general anxiety, and I think that plays out with being protective.”

Kramer also speculates that the shift toward social emotional learning that occurred in school systems across the country over the last decade could partly explain why there are fewer serial killers now. SEL helps students develop empathy and manage their frustration and anger, while also giving educators a chance to “compensate for some trauma that kids may have experienced in other settings, like their homes,” Kramer says. Although it’s not a guaranteed fix, that extra layer of support could help prevent potential serial killers from developing in the first place.

“By having some ability to identify individuals early in life who are having difficulty, to provide appropriate forms of intervention and treatment earlier and to provide more effective forms of treatment, all of this is improving,” Kramer says.

Even though there are fewer serial killers stalking American streets, the culture at large remains fascinated by the horrific, sordid tales of who Fox calls “the legacy killers.” Serial killers may have an oversized cultural presence given how unlikely it is for people to encounter them, but Fox says it is still vitally important to study and, hopefully, prevent them from killing.

“The Boston Strangler killed 13 people and impacted their loved ones, but also was able to hold this entire city in a grip of terror for years,” Fox says. “The idea that there was one person who wreaked so much havoc on the city, whatever we can do to understand and prevent and capture someone like that early on, the better off we are.”

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at [email protected] . Follow him on X/Twitter @Proelectioneer .

Editor's Picks

Can big data have a role in treating dementia that’s what this northeastern student is hoping to help solve , she went from marketing exec and part-time singer to opening her own art studio — while leaning on her northeastern mba, the uk wants to ban the next generation from smoking. will it work, .ngn-magazine__shapes {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--emphasize, #000) } .ngn-magazine__arrow {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--accent, #cf2b28) } ngn magazine these northeastern graduates are improving our neighborhoods one tree at a time, new models of big bang by northeastern physicists show that visible universe and invisible dark matter co-evolved, featured stories, wheelchair sensors can cost $10,000. here’s how northeastern engineering students built a better version — for $87, start summit at northeastern’s portland campus focuses on inclusivity and welcoming new entrepreneurs to maine, how can we provide better care for patients with severe brain injuries that’s the mission of this northeastern graduate, the whole world would lose in a full-blown war between israel and iran, northeastern expert says after latest escalation, society & culture.

Recent Stories

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

What can neuroscience tell us about the mind of a serial killer?

- By John Parrington

- April 19 th 2021

Serial killers—people who repeatedly murder others—provoke revulsion but also a certain amount of fascination in the general public. But what can modern psychology and neuroscience tell us about what might be going on inside the head of such individuals?

Serial killers characteristically lack empathy for others, coupled with an apparent absence of guilt about their actions. At the same time, many can be superficially charming, allowing them to lure potential victims into their web of destruction. One explanation for such cognitive dissonance is that serial killers are individuals in whom two minds co-exist—one a rational self, able to successfully navigate the intricacies of acceptable social behaviour and even charm and seduce, the other a far more sinister self, capable of the most unspeakable and violent acts against others. This view has been a powerful stimulus in fictional portrayals ranging from Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde , to Hitchcock’s Psycho , and a more recent film, Split . Yet there is little evidence that real-life serial killers suffer from dissociative identity disorder (DID), in which an individual has two or more personalities cohabiting in their mind, apparently unaware of each other.

Instead, DID is a condition more associated with victims, rather than perpetrators, of abuse, who adopt multiple personalities as a way of coming to terms with the horrors they have encountered. Of course a perpetrator of abuse may also be a victim, and many serial killers were abused as children, but in general they appear not to be split personalities, but rather people conscious of their acts. Despite this, there is surely a dichotomy in the minds of such individuals perhaps best personified by US killer Ted Bundy, who was a “charming, handsome, successful individual [yet also] a sadist, necrophile, rapist, and murderer with zero remorse who took pride in his ability to successfully kill and evade capture.”

“a recent brain imaging study … showed that criminal psychopaths had decreased connectivity between … a brain region that processes negative stimuli and those that give rise to fearful reactions”

One puzzling aspect of serial killers’ minds is the fact that they appear to lack—or can override—the emotional responses that in other people allows us to identify the pain and suffering of other humans as similar to our own, and empathise with that suffering. A possible explanation of this deficit was identified in a recent brain imaging study. This showed that criminal psychopaths had decreased connectivity between the amygdala—a brain region that processes negative stimuli and those that give rise to fearful reactions—and the prefrontal cortex, which interprets responses from the amygdala. When connectivity between these two regions is low, processing of negative stimuli in the amygdala does not translate into any strongly felt negative emotions. This may explain why criminal psychopaths do not feel guilty about their actions, or sad when their victims suffer.

Yet serial killers also seem to possess an enhanced emotional drive that leads to an urge to hurt and kill other human beings. This apparent contradiction in emotional responses still needs to be explained at a neurological level. At the same time, we should not ignore social influences as important factors in the development of such contradictory impulses. It seems possible that serial killers have somehow learned to view their victims as purely an object to be abused, or even an assembly of unconnected parts. This might explain why some killers have sex with dead victims, or even turn their bodies into objects of utility or decoration, but it does not explain why they seem so driven to hurt and kill their victims. One explanation for the latter phenomenon is that many serial killers are insecure individuals who feel compelled to kill due to a morbid fear of rejection. In many cases, the fear of rejection seems to result from having been abandoned or abused by a parent. Such fear may compel a fledgling serial killer to want to eliminate any objects of their affections. They may come to believe that by destroying the person they desire, they can eliminate the possibility of being abandoned, humiliated, or otherwise hurt, as they were in childhood.

Serial killers also appear to lack a sense of social conscience. Through our parents, siblings, teachers, peers, and other individuals who influence us as we grow up, we learn to distinguish right from wrong. It is this that inhibits us from engaging in anti-social behaviour. Yet serial killers seem to feel they are exempt from the most important social sanction of all—not taking another person’s life. For instance, Richard Ramirez, named the “Night Stalker” by the media, claimed at his trial that “you don’t understand me. You are not expected to. You are not capable of it. I am beyond your experience. I am beyond good and evil … I don’t believe in the hypocritical, moralistic dogma of this so-called civilized society.”

It remains far from clear why a few people react to abuse or trauma at an earlier stage in their lives by later becoming a serial killer. But hopefully new insights into the psychological or neurological basis of their actions may in the future help us to identify potential future such killers and dissuade them from committing such horrendous crimes.

Featured image via Pixabay

John Parrington is an Associate Professor in Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology at the University of Oxford, and a Tutorial Fellow in Medicine at Worcester College, Oxford. His latest book, Mind Shift (OUP, 2021), draws on the latest research on the human brain to show how it differs strikingly from those of other animals in its structure and function at a molecular and cellular level.

Parrington is also the author of The Deeper Genome (OUP, 2015) and Redesigning Life (OUP, 2016). He has published over 100 peer-reviewed articles in science journals including Nature, Current Biology, Journal of Cell Biology, Journal of Clinical Investigation, The EMBO Journal, Development, Developmental Biology , and Human Reproduction .

- Anthropology

- Psychology & Neuroscience

- Science & Medicine

- Social Sciences

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

[…] Click here to view original web page at blog.oup.com […]

For being so academically educated this article was poorly written. Everything here has been written many times before fervently. As much as the fascination exists to walk in their mind and body we can not unless we are like them. Unless there is stunning new research in anantomy, physiology or psychology; maybe it would be more productive to focus on teaching feelings, emotional intelligence and empathy to prevent this type of individual.

It would be better if the study/s mentioned were properly referenced to double-check them. I think that’s a paramount element when reading about any science-related topic.

Comments are closed.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Unravelling of an Expert on Serial Killers

By Lauren Collins

A brother and a sister are standing on the balcony of a sixth-floor apartment in Monte Carlo. It’s the nineteen-seventies, in May, the afternoon of the Grand Prix. The sun is glinting off the dinghies in the turquoise shallows of the harbor. The trees are so lush they’re almost black.

The brother, Stéphane Bourgoin, is in his twenties. He’s come from Paris to visit his sister Claude-Marie Dugué. Race cars circle the city, careening onto the straightaway on Boulevard Albert 1er, which Dugué’s apartment overlooks. Over the thrum, Bourgoin leans in and tells her something shocking: in America, where he’d recently been living, he had a girlfriend who was murdered and “cut up into pieces.” Her name was Hélène.

Bourgoin’s revelation was one of those moments when you “remember exactly what you were doing that day at that precise moment, the news is so striking and indelible,” Dugué recalled recently. “It was stupefaction and shudders, amid the revving engines of Formula 1.” Dugué and Bourgoin shared a father but had different mothers. They had got to know each other not long before, and Dugué didn’t feel that she could probe for details about a girlfriend she hadn’t met, or even heard of until that day. “I found the whole situation disturbing,” she said. She simply told Bourgoin how sorry she was.

At the time, Bourgoin had a career in the realm of B movies, reviewing fantasy and horror films for fanzines and dabbling in adult film. Later, he started writing his own books, which became hugely popular and helped establish him as a prominent expert on serial killers in France. His best-known work, “Serial Killers,” a thousand-page compendium of depravity, was released in five editions by the prestigious publisher Grasset. Travelling around the country to book festivals, Bourgoin built up a particularly devoted following within the already zealous subculture of true crime. One fan, Bourgoin said, sent him annotated copies of his own books, with items such as scissors, razors, and pubic hairs glued to the pages, corresponding to words in the text.

Bourgoin also had admirers in law and law enforcement. “He was one of the first people in France to say that serial killers weren’t only in America,” Jacques Dallest, the general prosecutor of the Grenoble appeals court, told me. Dallest was so impressed with Bourgoin that he invited him to speak at the École Nationale de la Magistrature, France’s national academy for judges and prosecutors. Bourgoin also gave talks at the Centre National de Formation à la Police Judiciaire, a training center for one of France’s main law-enforcement bodies, for which he claimed to have created the country’s first unit of serial-killer profilers.

[ Support The New Yorker’s award-winning journalism. Subscribe today » ]

An energetic self-promoter, Bourgoin appeared frequently in the press and on television. “I counted, I did eighty-four TV shows in one month,” he once said. “I get up at 4:45 A.M. to be on the morning shows and go home at midnight to have a bite to eat.” He cultivated a flamboyantly geeky look, with equal shades of Sherlock Holmes (ascot, horn-rimmed glasses) and Ace Ventura (cerulean blazer, silky skull-print shirt). A quirky-shoes enthusiast, he sometimes wore a pair of white brogues made to look as though they were spattered with blood. On Facebook, he claimed to possess the remains of Gerard Schaefer, a serial killer from Florida. “To each person who buys my book, I will offer a small bag containing a little piece of Schaefer—fingernails, hair, ear, kneecap, skin, bones, etc.,” he wrote, in 2015. Female fans, he added, would be given priority.

Bourgoin was most famous for his jailhouse interviews with murderers. In the course of more than forty years, he had conducted seventy-seven of them, he said, “in the four corners of the planet.” He riveted audiences with tales of his encounters with the “Son of Sam” killer David Berkowitz (“David, I come here, you agreed to meet me, but I hope you’re not going to tell me the same bullshit that you told at your trial”), with the homicidal hospital orderly Donald Harvey (“He confesses seventeen additional crimes to me that he hadn’t even been suspected of”), with the “Killer Clown” John Wayne Gacy (who, Bourgoin said, grabbed his buttocks during the encounter). “Confronting these individuals can be dangerous from a mental point of view,” Bourgoin wrote, in “Mes Conversations avec les Tueurs” (“My Conversations with Killers”), a 2012 book. “To make them talk, you have to let down your guard, open yourself completely to a psychopath, who manipulates, lies, and is devoid of any scruple.”

If you dedicate your life to serial killers, the first question anyone asks is “Why?” Bourgoin’s answer was that Hélène’s death made him want to confront the worst that humanity had to offer, as “a form of catharsis” or even as “a personal exorcism.” At some point, he started pronouncing her name “Eileen,” the American way. He said that he’d met her in the mid-seventies, when he was living in Los Angeles, working on B movies; that, in 1976, he went on a trip out of town; that when he returned to the home they shared he discovered her dead body, “mutilated, raped, and practically decapitated.” The killer was apprehended two years later, and eventually confessed to almost a dozen other murders. He was now awaiting execution on death row.

When an interviewer asked for an image of Eileen, Bourgoin would produce a black-and-white photograph of the young couple. It was beautifully composed, almost professional-looking. In it, the two of them are pictured in closeup, facing each other. Eileen has feathered hair and rainbow-shaped brows. Bourgoin’s hair is long, and he appears to be wearing a leather jacket with a big shearling collar. He is turned toward her in a protective stance. She looks up at him with a snaggletoothed smile. They’re so close that their noses are almost touching.

“Eileen was his hook,” Hervé Weill, who co-runs a crime-fiction festival at which Bourgoin often appeared, told me. The story of her death stirred the public’s emotions, adding a sheen of moral righteousness to Bourgoin’s vocation. “I knew of Stéphane Bourgoin well before this program having seen almost all his interviews with prisoners, but I’m only here learning that he was the partner of a victim,” a YouTube user wrote, after watching one of Bourgoin’s television appearances. “Incredible man.”

In his public appearances, Bourgoin delivered even the most gruesome anecdotes with weary didacticism, as if he had seen it all and emerged omniscient, emotion transmogrified into expertise. He spoke in data points: seventeen crimes, seventy-seven serial killers, “hundreds of thousands” of case files that he claimed to have stored in his cellar. “For nearly fifteen years, I accumulated files that I synthesized into more than five thousand tables, four of which are reproduced in the book,” he said at one point, announcing that he had, in all likelihood, solved the long-standing mystery of the murder of Elizabeth Short, known as the Black Dahlia.

Bourgoin could seem a little off at times, more like an admirer than a dispassionate observer of the killers he studied. But it was easy enough to interpret this macabre streak as a consequence of his trauma. His social-media feeds featured an uncomfortable mixture of cat pictures (he named a cat Bundy), promotional brags (“once again a packed house, for the seventeenth time in a row”), morbid memes (“ BEING CREMATED IS MY LAST HOPE FOR A SMOKING HOT BODY ”), and crime-related kitsch (barricade-tape toilet paper; gloves and a jacket designed to look as if they were made from human skin). He spoke of his opposition, on moral grounds, to the death penalty, but he’d pose for a photograph in a fake electric chair, captioning it “Today, I’m lacking a little juice.” What might normally have seemed in bad taste could feel like defiance coming from a bereaved partner. He showed up for interviews in a Jeffrey Dahmer T-shirt and signed books “With My Bloodiest Regards.”

In 1991, Bourgoin travelled to the Florida State Prison to meet Ottis Toole, sometimes called the Jacksonville Cannibal, for a French-television documentary. Toole claimed to have eaten some of his victims and allegedly issued a recipe for barbecue sauce calling for, among other ingredients, two cloves of garlic and a cup of blood.

Link copied

Bourgoin opened the interview brightly, saying that someone had sent him the recipe for the sauce. “And I must tell you that I tried it,” he said.

“Was it any good?” Toole asked.

“Yeah, it was very good,” Bourgoin answered, his voice quickening. “Although I didn’t try it on the same kind of meat that you did!”

Despite Bourgoin’s inclination toward facts and figures, his own memories could be indistinct. Sometimes he said that he’d been introduced to serial killers, in the late seventies, by a police officer he got to know from Eileen’s case; at other times, he said that he’d met some sympathetic cops at meals hosted by Robert Bloch, the author of “Psycho.” Bourgoin refused to identify Eileen’s killer, or to give her last name, saying that he was preserving her anonymity out of respect for her parents. Whether because of decency, laziness, or esteem for his reputation, Bourgoin’s interlocutors tended not to press him very hard. “I seem to have been prepared to put down his evasions to professional caution or eccentric obsession,” Tony Allen-Mills, a British journalist who interviewed Bourgoin in 2000, told me. “He was accepted as an expert, and that’s how I treated him.”

Bourgoin knew the power of fandom, having spent decades stoking the public’s emotional investment in true crime. But he underestimated the intelligence of the audience. After years of watching TV specials, attending talks, reading books, and replaying DVD boxed sets about necrophilia, satanism, bestiality, torture, infanticide, matricide, patricide, and the like, followers of the genre had learned not to count on anybody’s better angels, or to underestimate humankind’s capacity for deceit. They were connoisseurs of the self-valorizing lie, having been trained by authors like the “master of noir” himself.

One group of true-crime fans, disturbed by inconsistencies in Bourgoin’s stories, launched their own investigation, which would unravel his career. “Can you imagine yourself in a long hallway?” a member of the group told me. “Each time you open a door, behind it there’s another door. That’s how many lies there were.”

One seemingly grandiose element of Bourgoin’s life story is true: his father, Lucien Joseph Jean Bourgoin, was a great man of history. Jean, as he was known, was born in 1897, in Papeete, Tahiti. He joined the French military at the age of seventeen, fighting with distinction in the First World War before studying at the élite engineering school École Polytechnique. During the Second World War, he made a bold escape from French-colonial Indochina after being put under surveillance for his support of the Free French, and was personally summoned by Charles de Gaulle to join the government-in-exile in London.

As a civilian, Jean travelled the world building roads, tunnels, railroads, irrigation systems, and electrical networks. Later, he became a Commander of the Legion of Honor, and took part in UNESCO ’s effort to relocate the ancient Egyptian temples of Abu Simbel. His twenty-two-page dossier in the National Archives of France chronicles countless missions, decorations, and “special services rendered to Colonization” in roughly twenty countries. “I’ve heard that there was much more to the story, that he was also a high-level intelligence officer,” Julien Cuny, his grandson, told me.

Bourgoin’s mother, Franziska Glöckner, was as mysterious and daring as her husband. Born in Germany in 1910, she moved to France in the thirties after marrying her second husband, a French diplomat. In 1940, with her husband at war, she took a job as an interpreter with the German command at Saint-Malo, on the coast of Brittany. “Intelligent, courtesan-like, and calculating,” according to one writer, she spent the war years facilitating fishing permits, attending cocktail parties, and consorting with the Grand Duke of the Romanovs, who was living in exile at a nearby villa. A French official recalled that she eventually acquired “such an influence that she was known to all as ‘Commandante du Port.’ ” A newspaper article later dubbed her the “Mata Hari of Saint-Malo.”

Toward the end of the war, Franziska was arrested on charges of treason and was accused of acting as an informant. At her trial, ten local witnesses, including the former mayor of Saint-Malo, testified in her defense. “It was thanks to her exceptional situation with the high German command that the docks of Saint-Malo, where ninety-six mineshafts had been set, were not exploded,” a newspaper article reported. She was ultimately acquitted.

Jean and Franziska married in Saigon in 1951. He was fifty-three and she was forty. Two years later, their only child, Stéphane, was born in Paris. The family lived in a Haussman-style apartment in the Seventeenth Arrondissement, not far from the Arc de Triomphe. Stéphane spoke French, German, and English, and attended the venerable Lycée Carnot. He seems to have been an awkward child. “The second the bell rang, three minutes later I was outside with twenty people, but he was rather isolated,” Jean-Louis Repelski, a classmate, recalled.

An unremarkable student, Bourgoin left high school without a diploma. He was obsessed with cinema, sometimes seeing five movies in a day. “He was a walking dictionary,” Claude-Marie Dugué told me. “He knew all the directors and films by heart, and inundated me with references and anecdotes.” At some point, Bourgoin parlayed this interest into a series of jobs in adult film. He is credited as the screenwriter of “Extreme Close-Up,” “La Bête et la Belle,” and “Johnny Does Paris,” a series of late-seventies and early-eighties productions starring John Holmes, the prolific American porn actor.

Bourgoin has said that his career in movies got started in the U.S., but, despite featuring some American actors, the three films were shot in France. Bourgoin did go to America at least once in his youth, as I learned from the papers of his father’s former wife, Alice Gilbert Smith Bourgoin. Alice was a New England patrician, with a degree from Smith College, who appears to have had an ardent but melancholic relationship with Jean, exacerbated by the turbulence of their era. Toward the end of her life, she wrote an affectionate letter to Jean offering to return “two handsome and valuable rings you gave me—a solitaire diamond and a beautiful dark blue sapphire.”

Alice’s letter arrived in Paris on June 7, 1977, but Stéphane was the one to receive it. Jean had died, of a heart attack, three days earlier, at a ceremony hosted by his alma mater. Jean’s death must have been a shock, but Stéphane replied to Alice, in a letter dated the same day. “You do not know me, but I am Jean’s son, Stéphane, born in 1953, and, by the way, the only child of his last mariage [ sic ],” he wrote, in English. “Perhaps you want to know a little bit more about me.”

He told her that he had recently spent almost a year in America, but the letter made no mention of a murdered lover, or of a serial killer. “I love very much the USA and the kindness of the Americans,” he wrote. He added that he was engaged to an American girl who was living in France, a love story just like Alice and his father’s. “Right now, I am keeping aside every penny I earn to be able to make another trip to the States.” He concluded by giving Alice his telephone number and his address.

In the bottom left-hand corner of the second page of the letter, there is a handwritten note, made at a later date by a nephew of Alice’s:

Stéphane subsequently came to the USA and visited ASB, at her expense, when she handed over the rings. He never wrote to express any appreciation and was not heard from again before she died.

As a young man, Bourgoin resembled a character out of a potboiler. In the late seventies, he began working at Au Troisième Œil, a secondhand crime bookstore in Paris’s Ninth Arrondissement, which he later took over. Customers could find him there, presiding “like a spider in his web,” according to a longtime client. The shop was a narrow room bursting with first editions, forgotten genre novels, and rare crime fanzines, stacked double on shelves that ran from floor to ceiling. “It was a lair stuffed with literary treasures, and you could spend ages there talking about le roman noir ,” the writer Didier Daeninckx recalled.

The cultivated seediness of the place and its proprietor was irresistible to the writers who frequented the shop. Daeninckx put Bourgoin into one of his books, as a bookstore manager who deduces that a key character has cribbed his tale of suicide by piano from the plot of an obscure novel. Bourgoin also seems to have inspired the character of Étienne Jallieu, a “self-taught erudite shopkeeper” who outwits professional sleuths, in Jean-Hugues Oppel’s thriller “Six-Pack.” Bourgoin spun the myth out further, co-writing several especially grisly true-crime books (one focussed on infanticides) under the pseudonym Étienne Jallieu.

Bourgoin got an early taste of public attention in 1991, as a writer on “100 Years of X,” a cable documentary about porn. This was also the year of Bourgoin’s first filmed meeting with a murderer. Serial killers were having a cultural moment, following the success of Thomas Harris’s novel “The Silence of the Lambs.” On the eve of the book’s publication in French, Bourgoin wrote an article for a small crime-literature review about “a new type of criminal: the serial killer.” He seems to have sensed that a phenomenon was in the air, one that would only gain momentum with the release of a film version of “The Silence of the Lambs,” starring Anthony Hopkins and Jodie Foster. One night in Paris, Bourgoin regaled guests at a dinner party with tales of these new American murderers and the profilers who spent their days tracking them. “We were utterly captivated,” Carol Kehringer, a documentary producer who attended the dinner, told Scott Sayare, writing in the Guardian . “I started asking him all sorts of questions,” she added. “The more he spoke, the more I thought to myself, We’ve got to do a film!”

Kehringer and Bourgoin were acquaintances and had worked together before, so she asked him to conduct the interviews for the documentary. In the fall of 1991, Bourgoin and a crew flew to the United States to shoot the film for the French television channel FR3. At Quantico, they met with John Douglas, the pioneering F.B.I. criminal profiler who would later gain fame through his book “Mindhunter.” They travelled to Florida and California for meetings with murderers, arranged by the production crew.

The film, sold as “An Investigation Into Deviance,” was Bourgoin’s first public foray into the world of serial killers, but, by the time it was finished, Bourgoin and Kehringer were no longer speaking. “When he had the killers in front of him, it was as if he was sitting across from his idols,” she told the Guardian . Still, other producers continued working with him, and he soon published his first book on serial killers, a study of Jack the Ripper. He followed it with a flurry of spinoff volumes and, in 1993, with the first edition of his masterwork, the “Serial Killers” almanac.

Eileen doesn’t figure in Bourgoin’s work from this time. He seems to have introduced her into his professional repertoire sometime around 2000, even though, according to his sister, he had been telling the story privately for decades. “I had doubts when he said his girlfriend had been murdered, simply because I had known him for years and he had never spoken about it before,” François Guérif, a well-known French crime-fiction editor and Bourgoin’s former boss at the bookshop, recalled. Bourgoin was clearly conscious of a need to add emotional punch to his work. “He could cry on command,” Barbara Necek, who co-directed documentaries featuring Bourgoin, told me. Some of Bourgoin’s peers considered him a hack who presented himself as a globe-trotting criminologist when he was merely a jobbing presenter. “Neither I nor any of our mutual friends at the time had heard the story of his murdered girlfriend, nor of his so-called F.B.I. training,” a colleague and friend of Bourgoin’s from the eighties told me. “It triggered rounds of knowing laughter among us, because we all knew it was absolutely bogus.”

But elsewhere Bourgoin was taken seriously. As his career progressed, he came into contact with family members of the victims of killers. They saw him as a kindred survivor, someone who could be trusted to treat them with integrity, because of his personal experience. Conversely, proximity to them was valuable to Bourgoin as a form of reputational currency. “Each month, two or three people contact me,” he boasted, of his relationship with victims’ families, in 2012. Through his association with a victims-advocacy group called Victimes en Série, Bourgoin got to know Dahina Sy. She had been kidnapped and raped at the age of fourteen by Michel Fourniret, who later murdered seven young women.

One evening, Sy went to a dinner at Bourgoin’s house. The atmosphere there was peculiar—a “museum of horrors,” according to a journalist who once visited, filled with slasher-film posters, F.B.I. memorabilia, porcelain cherubs in satin masks, and case files of uncertain provenance. Sy told me, “He said, ‘Come here, I want to show you something.’ ” Bourgoin began pulling crime-scene photographs out of a folder. “Puddles of blood,” Sy said. “It was absolutely abject.” Sy had suffered from post-traumatic stress for years after her abduction. One of its manifestations was extreme arachnophobia. At the dinner table, Bourgoin put a plastic spider on her shoulder. “I was paralyzed, and he was laughing,” Sy recalled. “I think it gave him pleasure to mess with my mind.”

In 2018, Bourgoin began collaborating with the publishing house Glénat on a branded series of graphic novels (“Stéphane Bourgoin Presents the Serial Killers”). The second installment, about Fourniret, came out in March of 2020. Alerted by an acquaintance to the book’s existence, Sy was shocked to encounter her adolescent image rendered “flesh and bone” in a cartoon strip, with Fourniret threatening her (“I will be forced to disfigure you if you don’t do exactly as I say”), his words suspended in dialogue bubbles. Sy says that neither Bourgoin nor the publisher had notified her about the book, or about the fact that it reprinted the entirety of an interview that she’d given in a different context years earlier. She hired a lawyer to send a letter of complaint to the book’s publisher, which withdrew it from the market. “It was like being defiled a second time,” she told me.

Bourgoin never interrogated Fourniret, but, oddly, the book’s writer inserted a character inspired by Bourgoin throughout the text, a revered criminologist who goes by Bourgoin’s old pseudonym Étienne Jallieu.

“I admit that I’m having trouble understanding the dynamics of your relationship with your wife,” Jallieu tells Fourniret, facing him across a table in an alfresco interrogation room set up on a prison basketball court. “Probably because none of you tell the exact truth.”

“What is the truth for you, Monsieur Jallieu?” Fourniret asks.

“What you’ve spent your entire life trying to hide, Monsieur Fourniret,” Jallieu replies.

In 2019, a man who goes by the pseudonym Valak—inspired by a demon in the film “The Conjuring 2”—picked up a Bourgoin book that happened to be at hand. Valak, who is forty-five, lives in a port city in the South of France and works in a field unrelated to serial killers. When we spoke one day, over Zoom, he sat in a small room in front of a red velvet curtain. He wore a black baseball cap, a black polo, and a black mask, an outfit that was intended to protect his identity but also gave off a whiff of stagecraft. Valak told me that he had always been interested in human psychology, particularly at its extremes. He had enjoyed Bourgoin’s work as a teen-ager, but, revisiting it as an adult, he was struck by its sloppiness.

“There were things that didn’t seem coherent,” Valak told me. “I told myself, ‘O.K., it must be me that’s paranoid, that’s looking for a nit to pick.’ And then I discovered Facebook.”

One day, in a large Facebook group of true-crime enthusiasts, someone posted a link to an article about Bourgoin. Valak commented, expressing his unease about the work. He recalled, “There were a bunch of people who responded after that, saying, ‘ Bah , oui , I agree.’ ”

The skeptics—about thirty of them—formed a chat group to discuss their doubts about Bourgoin. That group eventually splintered into a smaller cohort, composed of Valak and seven others, living in France, Belgium, and Canada. (One member left the group after a falling out.) They called themselves the 4ème Œil Corporation (the Fourth Eye Corporation)—a play on Au Troisième Œil (At the Third Eye), the name of the bookstore that Bourgoin once ran.

At first, the group members saw their task as largely literary. They set to work combing through Bourgoin’s dozens of books, expecting to find instances of plagiarism. Bourgoin had, in fact, lifted passages from English-language works that hadn’t been translated into French. In some cases, he had even pilfered other people’s life experiences. He claimed, for instance, that, while visiting a crime scene in South Africa with the profiler Micki Pistorius, he was splattered by maggots and decomposing body parts that had been churned up by police helicopters. (Pistorius did experience a similar incident, but Bourgoin was not there.)

The members of the collective weren’t professional researchers, but they were assiduous. “As soon as we started looking,” Valak recalled, “we found more and more inconsistencies.” They decided to expand the scope of their investigation. Soon, they were devoting as much time to Bourgoin as they were to their day jobs. They contacted Bourgoin’s purported former colleagues, sent letters to prisons across the U.S., and scoured YouTube for clips of obscure speaking engagements and television appearances, like music lovers searching for concert bootlegs. They were completists, even interviewing a representative of the clerk of court in St. Lucie County, Florida, about Bourgoin’s claim that he possessed most of the case evidence related to Gerard Schaefer, who was sentenced there in 1973. (Bourgoin had neither the evidence nor the remains that he had bragged about.) This was the inverse of fandom: a passionate connection driven by disappointment rather than by admiration. One man became so consumed by the work that his relationship nearly ended.

In January of 2020, after months of research, the collective began posting a series of damning videos on YouTube. They contended that Bourgoin, a “serial mythomaniac,” had fabricated numerous aspects of his life and career. Eileen, for example, was not Bourgoin’s first wife, as he sometimes claimed (alternatively, he called her his “partner,” “girlfriend,” or “very close friend”): French public records obtained by the group established that his first wife was a Frenchwoman, and that they divorced in 1995. The collective showed that Bourgoin had also given wildly conflicting accounts of the timing, the place, and even the manner of Eileen’s death. Her supposed killer, furthermore, was nowhere to be found. The 4ème Œil had gone through a list of prisoners awaiting execution in California, and there wasn’t a single one who had killed the correct number of people in the time period that Bourgoin had laid out. Nor did they find evidence of a victim who fit the description that Bourgoin had given of Eileen.

Bourgoin’s professional résumé was as dubious as his personal history. By the collective’s reckoning, he had not interviewed seventy-seven serial killers but, rather, more likely only eight or nine. An interview with Charles Manson? Nobody in Manson’s camp had ever heard of it. In setting out his credentials, Bourgoin often claimed that the F.B.I. had invited him to complete two six-month training courses at Quantico with Douglas’s team of profilers. The 4ème Œil contacted Douglas, who, according to the group, replied, “Bourgoin is delusional and an imposter.”

Bourgoin’s lies ran the spectrum from pointless little fictions to brazen fabulation. In some cases, he tried to make himself sound more important than he was—he really did give talks at the Centre National de Formation à la Police Judiciaire, even if he had nothing to do with creating the law-enforcement body’s profiling unit. He really did know the writer James Ellroy, but a picture of the two of them that he had tweeted wasn’t taken “on vacation”; it was from a crime-fiction and film festival. Bourgoin also often took risks that didn’t comport with their potential payoff, as when he claimed that he had played professional soccer for seven years with the Red Star Football Club before moving to America. Bourgoin was born in 1953, and by 1976, the year in which Eileen was allegedly murdered, he was supposed to have been living in the U.S. “If his career had lasted for 7 years,” the 4ème Œil deduced, “he would have been pro at 16.” (Red Star: “No trace of him.”)

Bourgoin’s story wasn’t so much a house of cards as a total teardown. Some of his lies hardly made sense except in fulfilling his seemingly irresistible desire to become a character in dramas that didn’t concern him. At a talk that he gave to high-school students in 2015, he showed a clip of the interview he had done with the killer Donald Harvey, who was accompanied by his longtime attorney, William Whalen. Bourgoin called Whalen “a very close friend of mine.” He told the students, “Whenever he came to Europe, he stayed at my place in Paris. Unfortunately, last year he committed suicide, and in his suicide note he said that he was ultimately never able to live with the fact that he’d defended a killer like Donald Harvey.” Whalen, Bourgoin concluded, was a “new victim” of Harvey’s. Whalen’s family told me that they had never heard of Bourgoin, that Whalen had never travelled outside North America, and that Whalen was, to the end, a strong believer in the American judicial system and “very proud of defending Donald Harvey.”

The 4ème Œil even composed a psychological sketch similar to the serial-killer profiles with which Bourgoin had titillated the public: “The typical mythomaniac is fragile, subject to a strong dependence on others, and his faculties of imagination are increased tenfold. Whatever his profile, he is often the first victim of his imaginary stories, which he struggles to distinguish from reality.” The collective described Bourgoin as a “ voleur de vie ”—a stealer of life. “We’re by no means accusing Stéphane Bourgoin of being an assassin,” the group wrote. “By voleur de vie we mean that he helps himself to pieces of other people’s lives.”

Most cons become harder to keep up the longer they go on, but Bourgoin’s was cleverly self-sustaining. His lies enabled him to gain the very experience that he lacked, and every jailhouse interview doubled as a master class in manipulation. Blagging his way into prisons and police academies, Bourgoin, in pretending to be a serial-killer expert, at some point actually became one.

The 4ème Œil has extended the right of reply to Bourgoin on several occasions, but he has never responded to the group directly. The closest he came was when he hired a legal adviser who, citing copyright and privacy violations, got the group’s videos removed from YouTube. In February of 2020, Bourgoin announced that he was closing his public Facebook page and migrating to a private group. (It has nearly three thousand members, but its administrators blocked me as I was reporting this story.) He was going to be less active on social media, he said, but only because he needed to save all his time and energy for “the most important project of my life,” whose parameters he didn’t specify. Almost airily, he mentioned that he had been the victim of a “campaign of cyberbullying and hate on social media” and was being targeted by “bitter and jealous” individuals. Their acts, he declared, were akin to those of people who snitched on their neighbors during the collaborationist regime of Marshal Pétain.

Three months later, with pressure on Bourgoin mounting in the French press, he spoke to Émilie Lanez, of Paris Match. “ STéPHANE BOURGOIN, SERIAL LIAR?” the headline read. “ HE CONFESSES IN MATCH .” The article was empathetic, attesting to Bourgoin’s “phenomenal knowledge” and the respect that he commanded in the law-enforcement community, and presenting his lies as an unfortunate sideshow to a largely legitimate career. Bourgoin seemed erratic, toggling between tears and offhandedness, lamenting the weight of his lies but then dismissing them as “bullshit” or “jokes.”

Even as he unburdened himself, Bourgoin was sowing fresh confusion. The article explained, for instance, that Eileen was actually Susan Bickrest, who was murdered by a serial killer near Daytona Beach in 1975. The article described Bickrest as a barmaid and an aspiring cosmetologist who supplemented her income with sex work. Before her death, she and Bourgoin had seen each other “four or five times,” and he had transformed her into his wife because he “didn’t want people to know that he’d been helping her out financially.” The dates of Bickrest’s murder and her killer’s arrest didn’t align with the Eileen story, however, and even a cursory glance at photographs of the two women revealed that, except for both having blond hair, they didn’t look much alike.

“Day after day, we patiently untangled the threads, trying to distinguish true from false in the jumble of his statements,” Lanez wrote. Engaging with Bourgoin’s lies, I found, could have a strange generative power, inspiring in those who tried to decipher them the same kind of slippery speculation that they were attempting to resist. Étienne Jallieu, people pointed out, was nearly an anagram for “ J’ai tué Eileen ”—“I killed Eileen,” in French. (A more likely derivation is the town of Bourgoin-Jallieu, near Lyon.) A bio of Bourgoin at the end of an old, undated interview claimed that he had sometimes used the alias John Walsh in his adult-film days. John Walsh is a common enough name, but it also happens to be the name of the man who hosted “America’s Most Wanted” for many years. Walsh’s six-year-old son was murdered in Florida in 1981, and in 2008 Ottis Toole, the Florida drifter with whom Bourgoin joked about barbecue sauce, was posthumously recognized as the child’s murderer. Might Bourgoin have refashioned himself as the family member of a victim in imitation of Walsh? Or was his desire for proximity to mass killing born of his work on the films of John Holmes, who was later tried for and acquitted of the so-called Wonderland murders of 1981?

Just when I thought I was gaining some traction on Bourgoin’s story, a tiny crack would open up, sending me down a new rabbit hole. The Paris Match article, for instance, made the unusually specific claim that Bourgoin, in the seventies, lived on the eleventh floor of an apartment building on 155th Street in New York. I remembered that Bourgoin had once given a similar address in a Facebook post, claiming that he’d “lived in New York at the moment of the Son of Sam’s crimes.” That address turned out to be slightly different: 155 East Fifty-fifth Street. Curious, I typed it into a database. One of the first hits was a Times article from 1976—the year of Son of Sam—describing an apartment at the address as a “midtown house of prostitution.”

Xaviera Hollander, a former sex worker who now runs a bed-and-breakfast in Amsterdam, confirmed that 155 East Fifty-fifth Street was “the famous, or should I say infamous, apartment building where I started off as the happy hooker,” in the early seventies, but she had no memory of Bourgoin. Hollander added that the building used to be called the “horizontal whorehouse,” where “every floor had one or two hookers.” Eventually, I found the owner of apartment 11-H, where Bourgoin supposedly lived, and he told me that a man named Beau Buchanan had rented it in 1976. A director and producer of porn movies, Buchanan died in 2020. He easily could have known Bourgoin—but did Bourgoin take Buchanan’s address and make it his own, or had he really lived there?

It seemed a reasonable guess, given the period fashions and the professional composition, that the photograph of Bourgoin and the woman he had identified as Eileen had been taken on one of the movie sets he worked on in the seventies. The 4ème Œil felt reasonably sure that Eileen was Dominique Saint Claire, a well-known adult-film actress of the era. A porn expert I contacted suggested, independently, that Eileen might be Saint Claire, but, looking at the pictures of Saint Claire that were available online, I wasn’t convinced. (My attempts to contact Saint Claire were unsuccessful.)

I watched a head-spinning selection of films from the era and called a number of former actors—one was a maker of traditional and erotic chocolates—searching for some hint of Eileen. The movies that Bourgoin wrote are almost impossible to get ahold of, but Jill C. Nelson, a biographer of John Holmes, agreed to mail me a DVD of “Extreme Close-Up” from her personal collection. It’s a love-triangle story in which, as the DVD’s jacket copy notes, an American writer “is led into a world of European sexual delights where fantasy merges with reality.” I watched the movie attentively—at one point pausing an open-mouthed-orgasm scene to search for a snaggletooth—but none of the women resembled the one in Bourgoin’s photograph.

In early March, I called Bourgoin from a street corner in a rural village on France’s southwest coast, near where he now lives. I wasn’t expecting him to answer; I had tried to contact him before, without much luck. But, to my surprise, he picked up and quickly furnished his address. Several miles down the road, I found him standing in funky green shoes outside a modest house with an orange tiled roof and voile curtains with teapot appliqués and gingham trim.

Bourgoin invited me inside. I noticed, as he made coffee, that his knife rack was shaped like a human body, stuck through with blades at various points: forehead, heart, groin. Eventually, we sat down at a small table in the sunroom. He seemed unruffled by my unannounced visit, almost as though he’d been waiting for someone to show up.

A person who was once close to Bourgoin told me that he was an “excellent actor” and “extremely convincing, because, when he lies, he believes it very strongly, and so you believe it, too.” At the table, though, Bourgoin was diffident. He didn’t seem to be putting much effort into making me—or, possibly, himself—believe what he said. Or maybe he believed it so deeply that the delivery was no longer relevant. When I asked how many killers he had actually interviewed, he replied, in English, “It depends. Each time I was going to a jail, I asked to meet serial killers other than the ones I was authorized to film or interview. So sometimes at Florida State Prison I met in the courtyard during the promenade—I don’t know, two? five?—other serial killers.” He was just as evasive on other subjects. I asked him about the prank that he played on Dahina Sy. “It was a fake spider,” he said, as though that explained everything. (He later claimed that he was unaware of Sy’s arachnophobia.) When I brought up the rings that Alice, his father’s former wife, had given him, he said that he had called to thank her the next time he was in New York.

His instinct, in tense moments, was to show me his collections: piles of dusty tabloids, stacks of pulp fiction, an attic full of DVDs, desks and dressers and wardrobes containing boxes of old notebooks in which he had dutifully listed and rated, in a prim, upright hand, every film he’d seen. When I asked about the apartment at 155 East Fifty-fifth Street, he produced three large envelopes, postmarked in the early fall of 1975 and sent to “Stéphane Bourgoin, A.R.T. Films” at that address. A.R.T., he said, was a distribution company that had belonged to a friend of his, Beau Buchanan. The envelopes didn’t shed much light on Bourgoin’s doings in seventies New York, but for him such objects seemed almost equivalent to experiences.

In an article called “How I Was Bamboozled by Stéphane Bourgoin,” the Swiss journalist Anna Lietti examined her decision to write a mostly positive article about Bourgoin, despite her discomfort with his “overly smooth” presentation. “I was disappointed by the superficiality of my interlocutor and the lack of depth of his remarks,” Lietti, describing him as a sort of human reference book, wrote. “He lined up facts, dates, details, without offering a perspective, an original key to understanding these monsters to which he devoted his life.” In his countryside house, Bourgoin seemed a sad figure—a collector of trivia and paraphernalia, a man who just as easily could have spent decades amassing esoteric toys or obsessing over cryptocurrency, rather than living off the misfortunes of others. It was as though he thought that gathering enough props would make him a protagonist.

“I’m sorry that I lied and exaggerated things,” Bourgoin told me, at one point. “But I never raped or killed anybody.”

I asked what lies he was apologizing for.

“All the lies,” he said. But, he added, “there was mostly one important lie that I would do again.”

Bourgoin was referring to the Eileen story—the foundational lie upon which he had constructed his career. He admitted that he had invented her name, and the location of the murder. But, he insisted, he had really had a girlfriend who was murdered by a serial killer. “It was just a young girl that I met three times that I had sex with,” he said. Later, he was more explicit: “I invented that story because I was afraid that people would think that . . . I paid for a prostitute.”

Bourgoin didn’t want to give the woman’s name, even if I promised not to publish it. I asked if he could at least give me the identity of the woman in the photograph, but he claimed not to remember. “I think she was Spanish!” he added later.

The only time Bourgoin truly came alive was when he talked about the anonymous collective that had brought him down. We stood in his office, surrounded by fright masks and first editions, and he said that he was “quite happy it came out, but not the way that the 4ème Œil did it.” He asked me if I’d looked into the group’s membership. “You must have done some research on the people who accused me,” he said, suggesting that I get to work on a counter-investigation of his investigators.

Claude-Marie Dugué found out that her brother had been lying to her for half a century when the Paris Match article came out. She had never suspected it, but the news didn’t shock her. “Nothing surprises me in my family,” she said. Nor was she offended, on a personal level, by the breach of trust. “He didn’t really deceive me,” she said. “He let me into his world.”

Dugué’s son, Julien Cuny, told me that one quote from the article jumped out at him. “ Parfois, je me fais des films dans ma tête. J’ai toujours voulu qu’on m’aime ,” it read. “Sometimes I make films in my head. I’ve always wanted to be loved.” Cuny is an accomplished tech executive in Montreal, but he has always been daunted by his family’s distinction. To him, Bourgoin’s words were an almost inevitable response to an overwhelming mythology, “a phantasmagoric picture of distant family members (you almost never meet) who are always on an adventure somewhere.”

The first time Dugué and I exchanged e-mails, she told me something that I wasn’t expecting: she was the product of an extramarital relationship between Jean Bourgoin and her mother, Béatrice Pourchasse, as was her sister, who was born thirteen months before her. The girls lived with their mother in the Fourth Arrondissement. Jean Bourgoin lived with his family—Franziska and Stéphane—across town. Jean organized his parallel lives strictly, keeping them “watertight,” Dugué recalled, but she always felt loved by her father, who “followed and protected his liaison with my mother until the end,” providing money for the family, keeping track of the girls’ studies, and seeing them regularly. Even if he didn’t live with them, Dugué said, she felt immense pride “to be the daughter of such a man.”

One day, Dugué decided that she wanted to meet her younger brother. She was in her early twenties, and had known about him her entire life. He was maybe sixteen, a high schooler, and had no idea that she existed. “I posted myself discreetly inside the building where he lived, waiting for his return from the Lycée Carnot,” Dugué recalled. When he came home, she introduced herself: his secret sister. “He hardly believed me,” Dugué remembered. Nonetheless, they immediately got along. She remembered Bourgoin as a shy and serious boy with round glasses, adrift in a world of extravagantly accomplished adults. “How must Stéphane have perceived himself next to these two exceptional parents, crushed by so much strength and power?” she said. “He was happy to discover all at once that he had two sisters, and we started to communicate amongst ourselves.” They sent long letters between their father’s two households, written in violet ink.

The incident may have been Bourgoin’s initiation into the power of secret lives. “Back to my childhood I felt I didn’t do enough compared to my parents,” Bourgoin told me. “So I had always an inferiority complex.” Cuny echoed the sentiment. “I decided very early on that having a normal life means boring, and that would be the most horrible thing that could happen to me,” he told me. “My bet is Stéphane would prefer this outcome to being a local accountant who never left town.”

In “My Conversations with Killers,” Bourgoin wrote, “The immense majority of serial killers are inveterate liars from a very young age. Isolated, marginalized in their lives, they take refuge in the imaginary to construct a personality, far from the mediocre reality of their existence.” “ Parfois, je me fais des films dans ma tête. J’ai toujours voulu qu’on m’aime ,” Bourgoin said, as though he were performing a voice-over for his own life. “Sometimes I make films in my head. I’ve always wanted to be loved.” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

Why facts don’t change our minds .

The tricks rich people use to avoid taxes .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

How did polyamory get so popular ?

The ghostwriter who regrets working for Donald Trump .

Snoozers are, in fact, losers .

Fiction by Jamaica Kincaid: “Girl”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Amanda Petrusich

By David Remnick

By Dhruv Khullar

By Kyle Chayka

The science of serial killers is changing

In-depth analysis of murderers might help the rest of us, too.

By Kate Baggaley | Published Mar 8, 2019 1:30 AM EST

The wall of Sasha Reid’s office is covered with serial killers. The collection of black-and-white photographs of Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, and notable others is not, however, just an unusual choice of decoration.

“It’s very intentional,” says Reid. As a doctoral candidate in developmental psychology at the University of Toronto, she is trying to demystify the circumstances that lead people to commit multiple murders. That means poring over their own words from journals and media interviews. The viewpoints they express often share uncanny similarities, to the point where diary entries penned by different people begin to bleed together. On one occasion, Reid was brought up short by the words of Edmund Kemper (popularly known as the “Co-ed Killer” ). Kemper spoke often of domineering female relatives, and in one interview referred to “my grandmother who thought she had more balls than any man and was constantly emasculating me and my grandfather to prove it.” Lines like this reminded Reid powerfully of Gary Ridgway, ( the “Green River Killer” ), who had issues with his mother.

“I thought, ‘I literally just read this!’” she says. “Then I flipped over the page and I saw that actually this is somebody entirely different—but isn’t that interesting that they’re thinking the exact same thing.”

It was at that point that Reid decided to pin up the photographs. “Their individuality needed to be retained,” she says. Though the serial killers she studies think along very similar lines, Reid sees them as distinct people—people who are very poorly understood. Reid, who is due to finish her dissertation in May, has so far analyzed about 70 serial killers with her colleagues. Her hope is to reveal when their warped perspectives take root and how this kind of damage can be reversed when it shows up in children. “How can we help their development to unfold in a way that’s healthy as opposed to in a way that is completely catastrophic and harmful to society?” Reid says.

Little is actually known about how serial killers think and why they develop the way they do. Reid is among a small number of researchers who believe the time has come to probe their minds in exhaustive depth.

An unexpected case

The thought of six-dozen serial killers is an unsettling one. But for Reid, this sample is just the tip of the homicidal iceberg. She is creating a massive database filled with information on 6,000 serial killers from around the world. This involves searching for documentation about 600 different key details—such as being bullied or having a father with a history of criminal behavior—that may have influenced a person’s path to serial murder. She is also compiling a separate database of people who have gone missing in Canada. Her hope is to create a picture of who these people are and to understand who might have harmed them. On one memorable occasion, Reid unexpectedly found herself comparing her insights with the reality of an active serial killer.

It started when, one day in the summer of 2017, she noticed something bizarre. Three men with ties to the Church and Wellesley neighborhood of Toronto, also known as the city’s Gay Village, had disappeared several years previously. It’s not uncommon for clusters of people to disappear around the same time, often for reasons such as accidents, gang violence, overdoses, or becoming lost. But these men had gone missing under strikingly similar circumstances. All had vanished from a very small area, were men of color of similar ages, and had close ties to friends, family, or work that made an intentional vanishing act seem implausible. “It didn’t make sense, and that was the thing that united them the most,” Reid says. “My immediate thought was, ‘it’s probably a serial killer.’”

Reid consulted her database and used the patterns she observed in serial killers who targeted gay men to draw up a brief profile of the kind of person who might be responsible. She then called to share her findings with the police. As Reid expected, they did not end up using the information. However, in January 2018 the police arrested a 66-year-old landscaper named Bruce McArthur, who has since pleaded guilty to murdering eight men —including the three Reid had noticed.

The profile Reid created had erred on some details, such as the suspect’s age; given that most serial killers are under 40 years old, she had expected a man in his thirties. Other predictions were on the mark. Serial killers often bury their victims in sites over which they have control or easy access. And sure enough, the remains of multiple people were found in planters at a home where McArthur stored tools. Seeing the similarities between pieces of her analysis and the actual features of the crimes gave Reid reason to hope that her databases might have practical use in the future.

She is quick to point out that the widespread notion that police rely on profiles to solve cases is a romanticized one. “Police officers work on the foundation of forensic evidence, not Excel files,” Reid says. “But [the database] is something valuable to have on hand—especially as we start to develop it more and take the art out of it and make it more scientific.”

Embracing the art

Understanding serial killers, however, is as much an art as a science. “Experience is one thing, but the way in which those experiences are perceived across the lifetime is much more telling,” Reid says. “I’m kind of in both worlds, remove the art but embrace the art at the same time.”

Her particular focus is male serial killers whose crimes have a sexual element. While analyzing one of these people, Reid and a team of several other researchers each spend a week to a month digging through a trove of information. Among these sources are diary entries, home videos, interviews with the killer and people who knew him, police files, and medical or psychiatric records released into the public domain. The team looks for recurring themes and discusses the interpretations they each arrive at. Reid then tries to extrapolate a sense of how her subject sees the world and his place in it. “This can then give us a better indication of who they are victimizing, how, and why,” she says.

Reid and her team have honed in on a few core ways in which this group differs from most other people. Notably, serial killers feel they are constantly being pushed around, mistreated, and emasculated. “These people really go through their lives looking at everything that happens to them through the lens of a victim; they’re ultimate victims,” Reid says.

This is not to say that certain behaviors or cultural shifts are to blame for mass murder. Some serial killers did, in fact, survive horrific abuse as children. Others weathered much milder situations, but still believe their entire world is filled with abuse. For Gary Ridgway, one such intolerable experience was his mother’s command that he do his homework (Ridgway went on to murder at least 49 women in the state of Washington).

In fact, these people often yearn for connection with others. But in some cases love is not forthcoming, while in others they may be unable to understand or accept it as such. Often, these people misinterpret relatively gentle social cues as threats, and blame others for their problems.

“They fundamentally isolate themselves because they feel that they’re not accepted,” Reid says. “So they create these little worlds wherein they have ultimate power and control and authority.” But for people who believe the entire world is set against them, these fantasies can end up reinforcing unhealthy ways of engaging with others.

These tendencies are already well documented in serial killers. Reid, however, wants to reveal how such beliefs evolve over time. From what she’s observed so far, these elements seem to germinate during particular critical time periods, and may emerge in children as young as seven years old. By the age of 11 to 13, their violent fantasies begin to take on a life of their own, Reid says, becoming powerful and potent.

Each serial killer’s trajectory is unique; genetic predisposition may play a larger role for some, while life circumstances may be more important for others. However, none of these characteristics or experiences amount to destiny; development is a process that unfolds across the lifetime. Attributes such as resiliency and the ability to adapt to one’s circumstances are important as well.