Mozambique case study shows that poverty is about much more than income

Research Fellow, World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), United Nations University

Anthropologist and senior researcher, Chr. Michelsen Institute

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

United Nations University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

What does it mean to be poor? On the face of it, this may not sound like a very difficult question. In developed countries, almost all official and everyday definitions refer to poverty in income terms. In this sense, low consumption power (income) and poverty are essentially synonymous.

Outside of developed countries, a similar view of poverty frequently gets headlines. In its global comparisons, the World Bank has adopted the (in)famous poverty line of US$1.90 a day . So, people with daily real incomes below this amount form part of the global poor – thankfully, now a diminishing group.

One might dispute exactly how and where such a poverty line should be set. But the idea that being poor means not having an adequate income often seems uncontroversial.

Of course, among academics things are rarely so settled. Between economists, there is disagreement about whether poverty should be measured only in monetary terms. In other areas of social science, there is a tradition of scepticism that suggests standard quantitative definitions of poverty can be misleading .

Representing poverty as a kind of well-defined objective condition, like an infectious disease, focuses attention on the symptoms and immediate consequences of poverty. It risks diverting attention away from the underlying structural causes and diverse experiences of the poor.

Challenging official narratives

In a recent paper we explore contrasting views of well-being in Mozambique. Our interest reflects the country’s controversial track record. From the early 1990s until recently, Mozambique achieved one of the strongest sustained periods of aggregate economic growth of any country. Yet some argue this growth has largely not trickled down, leaving many behind.

Official poverty estimates undertaken by the government are of the classic quantitative or economic kind. Here a set of basic needs is identified and costed. Households consuming goods worth less than the cost of a minimal basket are deemed to be “poor”. Applying this definition, data from national surveys shows consumption poverty has declined over the past two decades at a steady, but not especially rapid, pace.

Today, almost half of all Mozambicans continue to live in absolute poverty. There are also large spatial gaps in well-being. For example, there is much lower poverty in the south of the country, around the capital city, reflecting widening levels of consumption inequality.

To provide perspective on this official narrative, a range of bottom-up studies of poverty , including our own, have been conducted by anthropologists in different parts of the country. These diverge in both form and content from the economic approach.

Indeed, the very starting point of this research has been distinctive. The intention was not to apply a pre-given or conceptually static definition of poverty, from which a count of the poor could proceed. Instead it was to probe local perspectives on well-being, the diverse forms of disadvantage, and the kinds of social relations in which disadvantage arises.

A main finding that emerges from the anthropological work is that we cannot see the poor without seeing the better-off. Local grammars of poverty – namely, the terms used to describe who are better- or worse-off – consistently distinguish between socially marginalised individuals and those with strong local social connections.

Perceptions of deprivation do highlight material deficiencies, such as a lack of food or clothes. But social relationships are vital to cope with vulnerability (shocks) and to facilitate social mobility. Being poor is intimately connected to one’s perceived “position” in a wider society and, through this, one’s scope for upward movement.

Self-reinforcing disadvantage

The anthropological view highlights the complex and often fairly localised ways in which the powerful, sometimes politically-connected, hoard opportunities for development. This reinforces existing divides and limits the social and economic mobility of the most disadvantaged.

For instance, the National District Development Fund in Niassa, Mozambique’s northern province, was seen as a main source of money for investment in (rural) economic activities. Formally, in allocating the funds, priority was to be given to agriculture rather than businesses, women rather than men, and associations rather than individuals.

But we found that the funds had been systematically co-opted by local influentes . These included traditional authorities, male entrepreneurs and the governing party elite through an intricate system of social relations of exclusion and bribes.

Other vignettes from the lives of the poor point to the diverse mechanisms through which disadvantage is reproduced. This is often linked to specific cultural practices that empower certain groups above others. They also point to the self-reinforcing nature of social and economic disadvantage.

For example, we met a single mother who had lost large parts of her harvest to drought two years in a row. She had struggled hard to put all her three children to school, but with no crops to sell and no well-placed family to support her, she could no longer pay the bribes necessary for her children to move up classes. We also encountered instances where people cut themselves off from vital relationships to avoid exposing themselves to the embarrassment of having failed and so as to preserve their dignity.

Making sense of disciplinary divides

How can we make sense of different disciplinary perspectives on poverty? On the one hand, it is tempting to seek some reconciliation. Surely, metrics of social capital or even subjective well-being can be added to existing measures of consumption power to provide a more complete characterisation of the poor? Or perhaps qualitative follow-ups among the consumption poor could be used to add local context?

Certainly, combined qualitative-quantitative approaches to poverty research have become popular and often yield richer insights than any one method on its own. Yet, as we elaborate in our paper, this somewhat misses the point.

There are fundamental philosophical differences between standard quantitative (economic) and qualitative (anthropological) traditions, which do not admit any easy fusion. These include differences in understandings about the form of social reality, what can be known about poverty, and how poverty is produced and reproduced.

For this reason, it is vital to allow separate and diverse perspectives on poverty to flourish. Each methodological approach has distinct strengths, limitations and policy uses.

The economic approach is essential to track economic progress over time on a consistent basis and identify households at greatest risk of consumption poverty (for example, to target social policy). But to uncover – and even resist – the inherently relational and often political ways in which poverty emerges and is reproduced requires a deeper, local, ethnographic touch.

Bringing these different perspectives into a meaningful dialogue with each other remains the next challenge.

- Southern Africa

- Peacebuilding

- Poverty2021

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Younger votes still lean toward Biden — but it’s complicated

Posting your opinion on social media won’t save democracy, but this might

Environmental law expert voices warning over Supreme Court

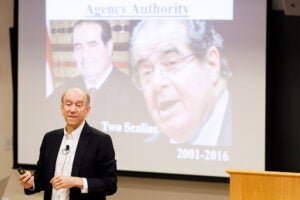

Robert Sampson, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, is one of the researchers studying the link between poverty and social mobility.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Unpacking the power of poverty

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Study picks out key indicators like lead exposure, violence, and incarceration that impact children’s later success

Social scientists have long understood that a child’s environment — in particular growing up in poverty — can have long-lasting effects on their success later in life. What’s less well understood is exactly how.

A new Harvard study is beginning to pry open that black box.

Conducted by Robert Sampson, the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, and Robert Manduca, a doctoral student in sociology and social policy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the study points to a handful of key indicators, including exposure to high levels of lead, violence, and incarceration as key predictors of children’s later success. The study is described in an April paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“What this paper is trying to do, in a sense, is move beyond the traditional neighborhood indicators people use, like poverty,” Sampson said. “For decades, people have shown poverty to be important … but it doesn’t necessarily tell us what the mechanisms are, and how growing up in poor neighborhoods affects children’s outcomes.”

To explore potential pathways, Manduca and Sampson turned to the income tax records of parents and approximately 230,000 children who lived in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, compiled by Harvard’s Opportunity Atlas project. They integrated these records with survey data collected by the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, measures of violence and incarceration, census indicators, and blood-lead levels for the city’s neighborhoods in the 1990s.

They found that the greater the extent to which poor black male children were exposed to harsh environments, the higher their chances of being incarcerated in adulthood and the lower their adult incomes, measured in their 30s. A similar income pattern also emerged for whites.

Among both black and white girls, the data showed that increased exposure to harsh environments predicted higher rates of teen pregnancy.

Despite the similarity of results along racial lines, Chicago’s segregation means that far more black children were exposed to harsh environments — in terms of toxicity, violence, and incarceration — harmful to their mental and physical health.

“The least-exposed majority-black neighborhoods still had levels of harshness and toxicity greater than the most-exposed majority-white neighborhoods, which plausibly accounts for a substantial portion of the racial disparities in outcomes,” Manduca said.

“It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.” Robert Sampson

“What this paper shows … is the independent predictive power of harsh environments on top of standard variables,” Sampson said. “It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.”

More like this

Cities’ wealth gap is growing, too

Racial and economic disparities intertwined, study finds

The study isn’t solely focused on the mechanisms of how poverty impacts children; it also challenges traditional notions of what remedies might be available.

“This has [various] policy implications,” Sampson said. “Because when you talk about the effects of poverty, that leads to a particular kind of thinking, which has to do with blocked opportunities and the lack of resources in a neighborhood.

“That doesn’t mean resources are unimportant,” he continued, “but what this study suggests is that environmental policy and criminal justice reform can be thought of as social mobility policy. I think that’s provocative, because that’s different than saying it’s just about poverty itself and childhood education and human capital investment, which has traditionally been the conversation.”

The study did suggest that some factors — like community cohesion, social ties, and friendship networks — could act as bulwarks against harsh environments. Many researchers, including Sampson himself, have shown that community cohesion and local organizations can help reduce violence. But Sampson said their ability to do so is limited.

“One of the positive ways to interpret this is that violence is falling in society,” he said. “Research has shown that community organizations are responsible for a good chunk of the drop. But when it comes to what’s affecting the kids themselves, it’s the homicide that happens on the corner, it’s the lead in their environment, it’s the incarceration of their parents that’s having the more proximate, direct influence.”

Going forward, Sampson said he hopes the study will spur similar research in other cities and expand to include other environmental contamination, including so-called brownfield sites.

Ultimately, Sampson said he hopes the study can reveal the myriad ways in which poverty shapes not only the resources that are available for children, but the very world in which they find themselves growing up.

“Poverty is sort of a catchall term,” he said. “The idea here is to peel things back and ask, What does it mean to grow up in a poor white neighborhood? What does it mean to grow up in a poor black neighborhood? What do kids actually experience?

“What it means for a black child on the south side of Chicago is much higher rates of exposure to violence and lead and incarceration, and this has intergenerational consequences,” he continued. “This is particularly important because it provides a way to think about potentially intervening in the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. We don’t typically think about criminal justice reform or environmental policy as social mobility policy. But maybe we should.”

This research was supported with funding from the Project on Race, Class & Cumulative Adversity at Harvard University, the Ford Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation.

Share this article

You might like.

New IOP poll shows they still plan to show up to vote but are subject to ‘seismic mood swings’ over specific issues

Tanner Lectures explore models of engaged citizenry from ancient agoras to modern megachurches

Richard Lazarus sees conservative majority as threat to protections developed over past half century

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

Poverty Reduction: Concept, Approaches, and Case Studies

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 10 January 2020

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Yakubu Aliyu Bununu 7

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

251 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Craig D, Porter D (2003) Poverty reduction strategy papers: a new convergence. World Dev 31(1):53–69

Article Google Scholar

Crawford G, Abdulai A-G (2009) The World Bank and Ghana’s poverty reduction strategies: strengthening the state or consolidating neoliberalism? Labour Cap Soc 42(1 & 2):82

Google Scholar

Cuesta J (2007) Political space, pro-poor growth, and poverty reduction strategy in Honduras: a story of missed opportunities. J Lat Am Stud 39:329–354

Dijkstra G (2005) The PRSP approach and the illusion of improved aid effectiveness: lessons from Bolivia, Honduras and Nicaragua. Dev Policy Rev 23(4): 443–464

Gottschalk R (2005) The macro content of PRSPs: assessing the need for a more flexible macroeconomic framework. Dev Policy Rev 23(4):419–443

IMF (2006) Cambodia: poverty reduction strategy paper. International Monetary Fund country report no. 06/266. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

IMF (2010) Nicaragua: poverty reduction strategy paper. International Monetary Fund country report no. 10/108. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

International Development Association (IDA) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2000a) Decision point document for the enhanced heavily indebted poor country initiative: Nicaragua. World Bank, Washington, DC

International Development Association (IDA) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2000b) Decision Point document for the enhanced heavily indebted poor country (HIPC) initiative: Honduras. World Bank, Washington, DC

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge/New York

Kingdom of Cambodia (2004) Cambodia National Poverty Reduction Strategy progress report. International Monetary Fund Country Report No. 06/266. International Monetary Fund Publication Services, Washington DC

Liu Q, Yu M, Wang X (2015) Poverty reduction within the framework of SDGs and post-2015 development agenda. Adv Clim Chang Res 6(2015):67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2015.09.004

National Social Investment Office (NSIO) (2018) Investing in our people: a brief on the National Social Investment Programmes in Nigeria. National Social Investment Office, The Presidency, Abuja

OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2014) Poverty and climate change: reducing the vulnerability of the poor through adaptation. http://www.oecd.org/environment/cc/2502872.pdf

Ogwumike FO (1987) Poverty and basic needs: an approach to development in Nigeria. Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Economics, University of Ibadan

Ogwumike FO (1995) The effects of macro-level government policies on rural development and poverty alleviation in Nigeria. Ib J Soc Sci 1(1):85–101

Ogwumike FO (1998) Poverty alleviation strategies in Nigeria. In: Measuring and monitoring poverty in Nigeria, Proceedings of the seventh annual conference of the Zonal Research Units of the Central Bank of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

Ogwumike FO (2001) An appraisal of poverty reduction strategies in Nigeria. Cent Bank Nigeria Econ Financ Rev 39(4):45–71. Central Bank of Nigeria

Ogwumike FO, Aromolaran AB (2000) Poverty dynamics in Nigeria. In: Proceedings of the seventh annual conference of the Zonal Research Units of the Central Bank of Nigeria. Central Bank of Nigeria, Abuja

Oladeji SI, Abiola AG (1998) Poverty alleviation with economic growth strategy: prospects and challenges in contemporary Nigeria. Niger J Econ Soc Stud 40(1):19–33

Oxford Poverty and Human Development Index (OPHI) (2019) Policy – a multidimensional approach – what is multidimensional poverty? https://ophi.org.uk/policy/multidimensional-poverty-index/ . Accessed 22 Aug 2019

Peck J, Theodore N (2010) Recombinant workfare across the Americas. Geoforum 41(1):195

Ruckert A (2007) Producing neoliberal hegemony? A neo-Gramscian analysis of the poverty reduction strategy in Nicaragua. Stud Polit Econ 79(Spring):91–118

Ruckert A (2009) A decade of poverty reduction strategies in Latin America: empowering or disciplining the poor? Labour Cap Soc 42(1 & 2):56. JSTOR 2009

Sumner A (2006) In search of the Post-Washington (dis)consensus: the missing content of PRSPs. Third World Q 27(8):1401–1412

UN (United Nations) (2012) The future we want. Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. http://www.un.org/en/sustainablefuture/

UN (United Nations) (2013) A new global partnership: eradicate poverty and transform economics through sustainable development. United Nations Publication, New York. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/8932013-05%20%20HLP%20Report%20%20A%20New%20Global%20Partnership.pdf

UN (United Nations) (2014a) Report of the open working group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals. A/68/970. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol¼A/68/970

UN (United Nations) (2014b) The road to dignity by 2030: ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet. A/69/700. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol¼A/69/700&%3bamp%3bLang¼E

UNDESA (2018) World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision. United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html

World Bank (2000) World development report 2000/2000: attacking poverty. World Bank, Washington, DC

Book Google Scholar

World Bank, IMF (2005) The poverty reduction strategy initiative: findings from 10 country case studies of World Bank and IMF support. World Bank Operations and Evaluation Department and IMF Independent Evaluation Office. The World Bank, Washington DC

World Poverty Clock (2018) The percentage of Nigerians living in extreme poverty could increase by 2030. World Data Lab. https://worldpoverty.io/blog/index.php?r=12 . Retrieved 03/02/2019

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Yakubu Aliyu Bununu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yakubu Aliyu Bununu .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience & Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

Istinye University, Istanbul, Turkey

Pinar Gökcin Özuyar

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

School of Sustainability Arizona State University, Tempe, USA

Rimjhim M Aggarwal

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Bununu, Y.A. (2020). Poverty Reduction: Concept, Approaches, and Case Studies. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T. (eds) Decent Work and Economic Growth. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71058-7_31-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71058-7_31-1

Received : 23 August 2019

Accepted : 08 September 2019

Published : 10 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-71058-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-71058-7

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Case Studies Shed Light on Poverty in America

A new report from the Community Affairs offices of the Federal Reserve System and the Brookings Institution examines the issue of concentrated poverty.

The Enduring Challenge of Concentrated Poverty in America: Case Studies from Communities Across the U.S. profiles 16 high-poverty communities, including immigrant gateway, Native American, urban and rural communities.

One of the case studies focuses on Holmes County, Miss., located in the district served by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. With a poverty rate that stood at more than 41 percent in 2000, Holmes County is both geographically and economically isolated. It has lost many jobs during past decades—and continues to do so.

The information collected on all the communities in this report contributes to an understanding of the dynamics of poor people living in poor communities and the policies that will be needed to bring both into the economic mainstream.

The report is available at www.stlouisfed.org/community_development/ .

Related Topics

Bridges is a regular review of regional community and economic development issues. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other community development questions

Poverty and Social Exclusion

Defining, measuring and tackling poverty, latest articles, home page featured articles, buenos aires 2017.

A recent report form the city of Buenos Aires measuring multi-dimensional poverty, using the consensual method, has found that in 2019, 15.3% of households were multi-dimensionally poor, rising to 25.7% for households with children under 18 years of age. The method established will be used to measure nu,ti-dimensional poverty on an ongoing basis.

6th Townsend poverty conference ad

We are now delighted to offer you the presentation slides and video recordings of sessions across the three days, featuring formal presentations, interactive Q&As, networking opportunities and much more.

Child deprivation in EU member states, 2018

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Steering Group on Measuring Poverty and Inequality has been tasked with producing a guide on Measuring Social Exclusion which references a lot of our PSE work.

Households in poverty: five case studies

Find out what it really means to miss out on what others take for granted and the deep impact this has on lives and opportunities. The PSE team have filmed with five families living in London, north-east England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Between them, they represent each of the following key groups vulnerable to poverty:

- single parents on benefits

- the young unemployed

- low-paid workers supporting a family

- adults who are disabled

- single pensioners .

All lack a range of the necessities selected by the public as essential for a minimum living standard in the UK today (see the full list of child and adult necessities in explore the data ). They are all also living on a low income. Using the consensual method for defining poverty that underpins the PSE: UK research, each household is living in poverty.

The following series of short films were recorded between late 2011 and early 2012. The PSE team is very grateful to all the families who are sharing their experiences with us.

Living in poverty featured articles

Featured case studies, the johnsons story.

Renée is 40 and works long hours for low pay to try to provide for her four children, aged 3 to 14, and her 80-year-old mother.

Jennie's story

Jennie is 39 and unemployed. She lives with her three sons, all of whom have disabilities, in Redbridge, outer London.

Marc's Story

Marc is 19 and lives in Redcar in north-east England, a town where there are twelve times as many people claiming job seeker’s allowance as there a

The burden of the downturn that followed the 2008 economic crash was borne by those on the lowest incomes (see Burden of economic downturn taken by the low paid ). In addition, the Coalition government’s austerity measures and changes to the tax and benefit system will impact heavily on those on lowest incomes. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the net effect will be a rise in both child and adult poverty levels (see UK poverty set to rise in next three years ). The government’s plans include cuts of £18 billion to the welfare budget between 2011 and 2014. While the introduction of Universal Credit should, in principle, increase the benefit entitlements of some households, these improvements are more than offset by other changes to personal taxes and state benefits, such as linking benefits to the Consumer Price Index rather than to the Retail Price Index (see Child and adult poverty set to rise by 2015 ). In addition, Universal Credit risks making certain groups significantly worse off, in particular single working mothers (see Welfare reforms could push 250,000 children deeper into poverty ).

Tweet this page

System Publications

The Enduring Challenge of Concentrated Poverty in America: Case Studies from Communities Across the U.S.

by The Federal Reserve System and the Brookings Metropolitan Policy program .

In 2006, the Community Affairs Offices of the Federal Reserve System partnered with the Brookings Institution to examine the issue of concentrated poverty. The resulting report, The Enduring Challenge of Concentrated Poverty in America: Case Studies from Communities Across the U.S. , profiles 16 high-poverty communities from across the country, including immigrant gateway, Native American, urban, and rural communities. Through these case studies, the report contributes to our understanding of the dynamics of poor people living in poor communities, and the policies that will be needed to bring both into the economic mainstream.

In the Richmond Fed District, this special report looks at the factors that give rise to high-poverty neighborhoods in West Greenville, NC and McDowell County, WV and the challenges they face.

Poverty data highlights include:

West Greenville, N.C.:

- The neighborhood poverty rate was more than 40 percent, twice as high as the poverty rate for the Greenville MSA.

- One in five households was headed by a single parent.

- Nearly 60 percent of children lived in poor households.

McDowell County, W.Va.:

- The poverty rate was 38 percent.

- One in every three residents aged 18 to 64 does not have health insurance – the lowest rate of coverage in West Virginia.

- Of the county’s working-age population, 40 percent claimed a disability of some kind.

Additional Resources

The Enduring Challenge of Concentrated Poverty in America

Phone Icon Contact Us

- Getting Published

- Open Research

- Communicating Research

- Life in Research

- For Editors

- For Peer Reviewers

- Research Integrity

China and SDG1: Efforts to alleviate poverty – a case study

Author: guest contributor.

Professor Xiaolin Wang, dean and professor at Fudan University, explores how China can be used as a case study for poverty alleviation efforts elsewhere and working towards achieving the aims of SDG1.

Could you share a brief overview of your book series? What were you hoping to achieve?

After attending the Rio+20 Conference (refer to United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development) in 2012, I realized there were still various challenges that need to be overcome before achieving the Millennium Development Goals, and that poverty and inequality continue to be the main issues developing countries need and have to face. Although the development experience from developed countries is precious, the new challenges of the current era caused by climate change, new technological revolution etc., are tremendous. Thus, it is difficult to solve the poverty problem in developing countries by following the experience of developed countries. China, as the largest developing country in the world, has made many new attempts and strategies in poverty reduction. Hopefully, these practical experiences could add value to other developing countries on poverty reduction.

How have you worked directly to address SDG1: No Poverty and how do this series contribute to this goal?

I believe that the quality of a country’s economic growth is one of the most crucial things for addressing SDG1. That’s why the theme of the first book of this series is about the quality of the economic growth and poverty reduction of China.

In my perspective, in fact, there are three pillars to promote poverty reduction in one country: the pro-poor economic growth, the inclusiveness of social development and multidimensional poverty alleviation and development. Relying only on income support plans cannot achieve the goal of poverty eradication. The public policy should promote this kind of growth, this is first pillar. The impoverished population benefits from economic growth above the average level of society, which is known as pro-poor economic growth. Meanwhile, poor people have more equitable access to public services, such as, education, health, and employment. The second pillar therefore, is inclusive social development. The third pillar is the delivery of multi-dimension targeted poverty alleviation.

The framework for integrating this book series is based on the above three pillars of public policies for poverty reduction. Under this framework, this book series includes the practice of targeted poverty alleviation in China.

I hope this book series could pass on a relatively logical and theoretical framework of the poverty governance knowledge system, which have been tested practically in China.

What is your motivation to focus your research and edit a book series on this particular topic? Is there a personal or professional reason that raised your interest?

This book series reflects my working experience for the last 25 years. The first time I realized a huge knowledge gap in poverty alleviation was at the age of 28 when I took charge of the investment estimation work for Western China’s poverty alleviation project by the World Bank. At that time, I was keen on finding well-edited poverty reduction books that combined theories, methods and practical operations. Unfortunately, there were minimal materials that could fit my requirements. Thus, I started to think about why I did not do poverty reduction-related research by myself and then edited such a book.

When the time came to 2006, I joined the Social Policy Division of UNICEF China Office and started researching child development and the national financial budget. In 2009, I went on a research visit on multidimensional poverty measure approach to the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), where I read a lot of poverty related literature, including professor Amartya Sen’s great works, whose theory of welfare economics greatly expanded my understanding of poverty. Between 2009 to 2017, I worked at the International Poverty Reduction Center in China (IPRCC) and the State Council Poverty Alleviation and Development Office of China for 8 years, participating in the formulation of some poverty reduction policies by the Chinese government.

Could you share your thoughts on the future of poverty reduction efforts both in China and on a global scale? What trends or developments do you anticipate in this field in the coming years?

China has worked hard to alleviate absolute poverty and aims to alleviate relative poverty and narrow the uneven development by implementing national rural revitalization and regional balanced development strategies. There are of course numerous challenges we have to face in alleviating poverty globally, with conflict, the digital divide, platform monopoly, climate change, etc., which may lead to large-scale poverty returning for human society.

In your perspective, how can we contribute to addressing real-world issues like poverty in the Global South, and how has your series and its books aimed to bridge the gap between research and practical solutions?

To address real-world issues and achieve the goals of SDGs, there are three necessary things that need to be done. First, governments should consolidate consensus on addressing global poverty and other development goals of SDGs. Secondly, it should establish more inclusive partnerships and thus raise funds for the development goal. Lastly, guiding digital technology and digital platforms to become more inclusive and encouraging the digital technology to promote inclusive solutions.

It is essential for the Global South to build unique knowledge systems based on their national conditions and international development experience. Secondly, it is necessary for countries belonging to the Global South to strengthen their relationship by sharing experience and knowledge, especially on the aspect of poverty reduction and development. Last but not least, as this book series is an open series, we hope it could include more research and information on poverty reduction from Africa, South Asia, Latin America etc., in the near future.

Why did you choose to publish this book series with Springer Nature? What did you enjoy the most when you work with Springer Nature?

The main reason for choosing Springer is due to its power of international influence and communication. This book series focuses on global poverty reduction, so I hope it could be shared in various countries worldwide. I believe this book series could be helpful for government officers, NGOs, universities and research institutions in low and middle-income countries.

About the author

Dr WANG Xiaolin is the Deputy Dean and professor of the Institute for Six-sector Economy, Fudan University, professor of the School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Fudan University. He is the Executive Director of Shanghai (Fudan University) Institute for Cooperation and Development, a member of the Shanghai Municipal Government Cooperation and Exchange Expert Committee, Deputy Secretary-General of the China Soft Science Research Association, executive director of China Rural Development Research Association, and special expert of Shaanxi Province. He also serves as an advisory expert for the United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation, the United Nations World Food Programme and other international organizations. He was a former member of the Expert Advisory Committee of the Leading Group on Poverty Alleviation and Development of the State Council, P. R. China.

Guest Contributors include Springer Nature staff and authors, industry experts, society partners, and many others. If you are interested in being a Guest Contributor, please contact us via email: [email protected] .

- SN SDG Programme

- Tools & Services

- Account Development

- Sales and account contacts

- Professional

- Press office

- Locations & Contact

We are a world leading research, educational and professional publisher. Visit our main website for more information.

- © 2023 Springer Nature

- General terms and conditions

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Your Privacy Choices / Manage Cookies

- Accessibility

- Legal notice

- Help us to improve this site, send feedback.

Latest at Reach

News News , Podcast

Empowering Voices, Inspiring Change: Celebrating International Women’s Month

The reach alliance.

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at the University of Toronto

1 Devonshire Place, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7 Canada

General Inquiries

reachalliance.munk@utoronto.ca

Case Studies

The Reach Alliance is committed to being a prominent hub of inclusive knowledge production. We prioritize knowledge, knowers, and ways of knowing that have been traditionally disengaged and marginalized from ‘legitimate’ academic knowledge. We work with research collaborators to share findings with the global insight community, project implementers, those that contributed to the research, and those that can benefit from the research directly. We do so in ways that amplify the perspectives of those who have historically been left out or silenced in these discussions.

Academic Partner

Research Status

Research year.

Case Study India

Cutting Through the Grass Ceiling: Supporting Women Smallholder Farmers with the Collective Power of Community, Participatory Learning, and Trust

SDG 1 SDG 3 SDG 5 SDG 13

Case Study Rwanda

Increasing Meaningful Financial Inclusion in Rwanda: Community-Based Savings and Credit Co-operative Societies

SDG 10 SDG 1 SDG 8

Case Study Mexico

The “Kolombia Regia”: Social Vindication in the Face of Stigma and Violence in Monterrey

SDG 1 SDG 10 SDG 16 SDG 5

Struggle and Resilience of Migrant Indigenous Communities in Irregular Settlements in Mexico

SDG 1 SDG 8 SDG 10 SDG 11

Expanding Access to Justice Through Community-Based Paralegals in New Delhi and Assam

SDG 1 SDG 5 SDG 8 SDG 10 SDG 16

Case Study Thailand

M Fund – a migrant micro insurance program

SDG 1 SDG 3 SDG 10

Case Study Kenya

Left Behind: The Socioeconomic Barriers to Last-Mile Mobile Money Access in Kenya

SDG 1 SDG 8 SDG 10

Providing Urban Amenities to Rural Areas: Addressing Rural Poverty in India

SDG 1 SDG 10

Case Study Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme: Addressing Food Insecurity with Food and Cash Transfers

SDG 1 SDG 2 SDG 10

Case Study Jordan

UNHCR Jordan’s Biometric Cash Assistance Program for Syrian Refugees

Aadhaar Identification Program: Providing Proof of Identity to a Billion

SDG 1 SDG 16

Case Study South Africa

Reaching the Hard to Reach: A Case Study of Birth Registration in South Africa

SDG 1 SDG 3 SDG 16

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Social Consequences of Poverty: An Empirical Test on Longitudinal Data

Carina mood.

Institute for Futures Studies, Box 591, 101 31 Stockholm, Sweden

Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Jan O. Jonsson

Nuffield College, OX1 1NF Oxford, England, UK

Poverty is commonly defined as a lack of economic resources that has negative social consequences, but surprisingly little is known about the importance of economic hardship for social outcomes. This article offers an empirical investigation into this issue. We apply panel data methods on longitudinal data from the Swedish Level-of-Living Survey 2000 and 2010 (n = 3089) to study whether poverty affects four social outcomes—close social relations (social support), other social relations (friends and relatives), political participation, and activity in organizations. We also compare these effects across five different poverty indicators. Our main conclusion is that poverty in general has negative effects on social life. It has more harmful effects for relations with friends and relatives than for social support; and more for political participation than organizational activity. The poverty indicator that shows the greatest impact is material deprivation (lack of cash margin), while the most prevalent poverty indicators—absolute income poverty, and especially relative income poverty—appear to have the least effect on social outcomes.

Introduction

According to the most influential definitions, poverty is seen as a lack of economic resources that have negative social consequences—this is in fact a view that dominates current theories of poverty (Townsend 1979 ; Sen 1983 ; UN 1995 ), and also has a long heritage (Smith 1776 /1976). The idea is that even when people have food, clothes, and shelter, economic problems lead to a deterioration of social relations and participation. Being poor is about not being able to partake in society on equal terms with others, and therefore in the long run being excluded by fellow citizens or withdrawing from social and civic life because of a lack of economic resources, typically in combination with the concomitant shame of not being able to live a life like them (e.g., Sen 1983 ). Economic hardship affects the standard of life, consumption patterns, and leisure time activities, and this is directly or indirectly related to the possibility of making or maintaining friends or acquaintances: poverty is revealed by not having appropriate clothes, or a car; by not being able to afford vacation trips, visits to the restaurant, or hosting dinner parties (e.g., Mack and Lansley 1985 ; Callan et al. 1993 )—in short, low incomes prevent the poor from living a life in “decency” (Galbraith 1958 ).

The relational nature of poverty is also central to the social exclusion literature, which puts poverty in a larger perspective of multiple disadvantages and their interrelationships (Hills et al. 2002 , Rodgers et al. 1995 ; Room 1995 ). While there are different definitions of the social exclusion concept, the literature is characterized by a move from distributional to relational concerns (Gore 1995 ) and by an emphasis on the importance of social integration and active participation in public life. The inability of living a decent or “ordinary” social life may in this perspective erode social networks, social relations, and social participation, potentially setting off a downward spiral of misfortune (Paugam 1995 ) reinforcing disadvantages in several domains of life. This perspective on poverty and social exclusion is essentially sociological: the playing field of the private economy is social. It is ultimately about individuals’ relations with other people—not only primary social relations, with kin and friends, but extending to secondary relations reflected by participation in the wider community, such as in organizations and in political life (UN 1995 ).

Despite the fact that the social consequences of limited economic resources are central to modern perspectives on poverty and marginalization, this relation is surprisingly seldom studied empirically. Qualitative research on the poor give interesting examples on how the negative effects of poverty works, and portray the way that economic problems are transformed into social ones (Ridge and Millar 2011 ; Attree 2006 ). Such studies, however, have too small sample sizes to generalize to the population, and they cannot tell us much about the range of the problem. The (relatively few) studies that have addressed the association between poverty and social outcomes on larger scale tend to verify that the poor have worse social relations (Böhnke 2008 ; Jonsson and Östberg 2004 ; Levitas 2006 ), but Barnes et al. ( 2002 ) did not find any noteworthy association between poverty (measured as relative income poverty, using the 60 %-limit) and social relations or social isolation. Dahl et al. ( 2008 ) found no relation between poverty and friendships, but report less participation in civic organizations among the poor. All these studies have however been limited to cross-sectional data or hampered by methodological shortcomings, and therefore have not been able to address the separation of selection effects from potentially causal ones.

Our aim in this study is to make good these omissions. We use longitudinal data from the Swedish Level of Living Surveys (LNU) 2000 and 2010 to study how falling into poverty, or rising from it, is associated with outcomes in terms of primary and secondary social relations, including participation in civil society. These panel data make it possible to generalize the results to the Swedish adult population (19–65 in 2000; 29–75 in 2010), to address the issue of causality, and to estimate how strong the relation between economic vulnerability and social outcomes is. Because the data provide us with the possibility of measuring poverty in several ways, we are also able to address the question using different—alternative or complementary—indicators. Poverty is measured as economic deprivation (lack of cash margin, self-reported economic problems), income poverty (absolute and relative), and long-term poverty, respectively. The primary, or core, social outcomes are indicated by having social support if needed, and by social relations with friends and relatives. We expand our analysis to secondary, or fringe, social outcomes in terms of participation in social life at large, such as in civil society: our indicators here include the participation in organizations and in political life.

Different Dimensions/Definitions of Poverty

In modern welfare states, the normal take on the issue of poverty is to regard it as the relative lack of economic resources, that is, to define the poor in relation to their fellow citizens in the same country at the same time. Three approaches dominate the scholarly literature today. The first takes as a point of departure the income deemed necessary for living a life on par with others, or that makes possible an “acceptable” living standard—defined as the goods and services judged necessary, often on the basis of consumer or household budget studies. This usage of a poverty threshold is often (somewhat confusingly) called absolute income poverty , and is most common in North America (cf. Corak 2006 for a review), although most countries have poverty lines defined for different kinds of social benefits. In Europe and in the OECD, the convention is instead to use versions of relative income poverty , defining as poor those whose incomes fall well behind the median income in the country in question (European Union using 60 % and OECD 50 % of the median as the threshold). As an alternative to using purchasing power (as in the “absolute” measure), this relative measure defines poverty by income inequality in the bottom half of the income distribution (Atkinson et al. 2002 ; OECD 2008 ).

The third approach argues that income measures are too indirect; poverty should instead be indicated directly by the lack of consumer products and services that are necessary for an acceptable living standard (Mack and Lansley 1985 ; Ringen 1988 ; Townsend 1979 ). This approach often involves listing a number of possessions and conditions, such as having a car, washing machine, modern kitchen; and being able to dine out sometimes, to have the home adequately heated and mended, to have sufficient insurances, and so on. An elaborate version includes information on what people in general see as necessities, what is often termed “consensual” poverty (e.g., Mack and Lansley 1985 ; Gordon et al. 2000 ; Halleröd 1995 ; van den Bosch 2001 ). Other direct indicators include the ability to cover unforeseen costs (cash margin) and subjective definitions of poverty (e.g., van den Bosch 2001 ). The direct approach to poverty has gained in popularity and measures of economic/material deprivation and consensual poverty are used in several recent and contemporary comparative surveys such as ECHP (Whelan et al. 2003 ) and EU-SILC (e.g., UNICEF 2012 ; Nolan and Whelan 2011 ).

It is often pointed out that, due to the often quite volatile income careers of households, the majority of poverty episodes are short term and the group that is identified as poor in the cross-section therefore tends to be rather diluted (Bane and Ellwood 1986 ; Duncan et al. 1993 ). Those who suffer most from the downsides of poverty are, it could be argued, instead the long-term, persistent, or chronically poor, and there is empirical evidence that those who experience more years in poverty also are more deprived of a “common lifestyle” (Whelan et al. 2003 ). Poverty persistence has been defined in several ways, such as having spent a given number of years below a poverty threshold, or having an average income over a number of years that falls under the poverty line (e.g., Duncan and Rodgers 1991 ; Rodgers and Rodgers 1993 ). The persistently poor can only be detected with any precision in longitudinal studies, and typically on the basis of low incomes, as data covering repeated measures of material deprivation are uncommon.

For the purposes of this study, it is not essential to nominate the best or most appropriate poverty measure. The measures outlined above, while each having some disadvantage, all provide plausible theoretical grounds for predicting negative social outcomes. Low incomes, either in “absolute” or relative terms, may inhibit social activities and participation because these are costly (e.g., having decent housing, needing a car, paying membership fees, entrance tickets, or new clothes). Economic deprivation, often indicated by items or habits that are directly relevant to social life, is also a valid representation of a lack of resources. Lastly, to be in long-term poverty is no doubt a worse condition than being in shorter-term poverty.

It is worth underlining that we see different measures of poverty as relevant indicators despite the fact that the overlap between them often is surprisingly small (Bradshaw and Finch 2003 ). The lack of overlap is not necessarily a problem, as different people may have different configurations of economic problems but share in common many of the experiences of poverty—experiences, we argue, that are (in theory at least) all likely to lead to adverse social outcomes. Whether this is the case or not is one of the questions that we address, but if previous studies on child poverty are of any guidance, different definitions of poverty may show surprisingly similar associations with a number of outcomes (Jonsson and Östberg 2004 ).

What are the Likely Social Consequences of Poverty?

We have concluded that poverty is, according to most influential poverty definitions, manifested in the social sphere. This connects with the idea of Veblen ( 1899 ) of the relation between consumption and social status. What you buy and consume—clothes, furniture, vacation trips—in part define who you are, which group you aspire to belong to, and what view others will have of you. Inclusion into and exclusion from status groups and social circles are, in this view, dependent on economic resources as reflected in consumption patterns. While Veblen was mostly concerned about the rich and their conspicuous consumption, it is not difficult to transfer these ideas to the less fortunate: the poor are under risk of exclusion, of losing their social status and identity, and perhaps also, therefore, their friends. It is however likely that this is a process that differs according to outcome, with an unknown time-lag.

If, as outlined above, we can speak of primary and secondary social consequences, the former should include socializing with friends, but also more intimate relations. Our conjecture is that the closer the relation, the less affected is it by poverty, simply because intimate social bonds are characterized by more unconditional personal relations, typically not requiring costs to uphold.

When it comes to the secondary social consequences, we move outside the realm of closer interpersonal relations to acquaintances and the wider social network, and to the (sometimes relatively anonymous) participation in civil or political life. This dimension of poverty lies at the heart of the social exclusion perspective, which strongly emphasizes the broader issues of societal participation and civic engagement, vital to democratic societies. It is also reflected in the United Nation’s definition, following the Copenhagen summit in 1995, where “overall poverty” in addition to lack of economic resources is said to be “…characterized by lack of participation in decision-making and in civil, social, and cultural life” (UN 1995 , p. 57). Poverty may bring about secondary social consequences because such participation is costly—as in the examples of travel, need for special equipment, or membership fees—but also because of psychological mechanisms, such as lowered self-esteem triggering disbelief in civic and political activities, and a general passivity leading to decreased organizational and social activities overall. If processes like these exist there is a risk of a “downward spiral of social exclusion” where unemployment leads to poverty and social isolation, which in turn reduce the chances of re-gaining a footing in the labour market (Paugam 1995 ).

What theories of poverty and social exclusion postulate is, in conclusion, that both what we have called primary and secondary social relations will be negatively affected by economic hardship—the latter supposedly more than the former. Our strategy in the following is to test this basic hypothesis by applying multivariate panel-data analyses on longitudinal data. In this way, we believe that we can come further than previous studies towards estimating causal effects, although, as is the case in social sciences, the causal relation must remain preliminary due to the nature of observational data.

Data and Definitions

We use the two most recent waves of the Swedish Level-of-living Survey, conducted in 2000 and 2010 on random (1/1000) samples of adult Swedes, aged 18–75. 1 The attrition rate is low, with 84 % of panel respondents remaining from 2000 to 2010. This is one of the few data sets from which we can get over-time measures of both poverty and social outcomes for a panel that is representative of the adult population (at the first time point, t 0 )—in addition, there is annual income information from register data between the waves. The panel feature obviously restricts the age-groups slightly (ages 19–65 in 2000; 29–75 in 2010), the final number of analyzed cases being between 2995 and 3144, depending on the number of missing cases on the respective poverty measure and social outcome variable. For ease of interpretation and comparison of effect sizes, we have constructed all social outcome variables and poverty variables to be dichotomous (0/1). 2

In constructing poverty variables, we must balance theoretical validity with the need to have group sizes large enough for statistical analysis. For example, we expand the absolute poverty measure to include those who received social assistance any time during the year. As social assistance recipients receive this benefit based on having an income below a poverty line that is similar to the one we use, this seems justifiable. In other cases, however, group sizes are small but we find no theoretically reasonable way of making the variables more inclusive, meaning that some analyses cannot be carried out in full detail.

Our income poverty measures are based on register data and are thus free from recall error or misreporting, but—as the proponents of deprivation measures point out—income poverty measures are indirect measures of hardship. The deprivation measure is more direct, but self-reporting always carries a risk of subjectivity in the assessment. To the extent that changes in one’s judgment of the economic situation depend on changes in non-economic factors that are also related to social relations, the deprivation measure will give upwardly biased estimates. 3 As there is no general agreement about whether income or deprivation definitions are superior, our use of several definitions is a strength because the results will give an overall picture that is not sensitive to potential limitations in any one measure. In addition, we are able to see whether results vary systematically across commonly used definitions.

Poverty Measures

- Cash margin whether the respondent can raise a given sum of money in a week, if necessary (in 2000, the sum was 12,000 SEK; in 2010, 14,000 SEK, the latter sum corresponding to approximately 1600 Euro, 2200 USD, or 1400 GBP in 2013 currency rates). For those who answer in the affirmative, there is a follow-up question of how this can be done: by (a) own/household resources, (b) borrowing.

- Economic crisis Those who claim that they have had problems meeting costs for rent, food, bills, etc. during the last 12 months (responded “yes” to a yes/no alternative).

- Absolute poverty is defined as either (a) having a disposable family income below a poverty threshold or (b) receiving social assistance, both assessed in 1999 (for the survey 2000) or 2009 (for the survey 2010). The poverty line varies by family type/composition according to a commonly used calculation of household necessities (Jansson 2000 ). This “basket” of goods and services is intended to define an acceptable living standard, and was originally constructed for calculating an income threshold for social assistance, with addition of estimated costs for housing and transport. The threshold is adjusted for changes in the Consumer Price Index, using 2010 as the base year. In order to get analyzable group sizes, we classify anyone with an income below 1.25 times this threshold as poor. Self-employed are excluded because their nominal incomes are often a poor indicator of their economic standard.

- Deprived and income poor A combination of the indicator of economic deprivation and the indicator of absolute poverty. The poor are defined as those who are economically deprived and in addition are either absolute income-poor or have had social assistance some time during the last calendar year.

- Long - term poor are defined as those interviewed in 2010 (2000) who had an equivalized disposable income that fell below the 1.25 absolute poverty threshold (excluding self-employed) or who received social assistance in 2009 (1999), and who were in this situation for at least two of the years 2000–2008 (1990–1998). The long-term poor (coded 1) are contrasted to the non-poor (coded 0), excluding the short-term poor (coded missing) in order to distinguish whether long-term poverty is particularly detrimental (as compared to absolute poverty in general).

- Relative poverty is defined, according to the EU standard, as having a disposable equivalized income that is lower than 60 % of the median income in Sweden the year in question (EU 2005). 4 As for absolute poverty, this variable is based on incomes the year prior to the survey year. Self-employed are excluded.

Social and Participation Outcomes

Primary (core) social relations.

- Social support The value 1 (has support) is given to those who have answered in the positive to three questions about whether one has a close friend who can help if one (a) gets sick, (b) needs someone to talk to about troubles, or (c) needs company. Those who lack support in at least one of these respects are coded 0 (lack of support).

- Frequent social relations This variable is based on four questions about how often one meets (a) relatives and (b) friends, either (i) at ones’ home or (ii) at the home of those one meets, with the response set being “yes, often”, “sometimes”, and “no, never”. Respondents are defined as having frequent relations (1) if they have at least one “often” of the four possible and no “never”, 5 and 0 otherwise.

Secondary (fringe) Social Relations/Participation

- Political participation : Coded 1 (yes) if one during the last 12 months actively participated (held an elected position or was at a meeting) in a trade union or a political party, and 0 (no) otherwise. 6

- Organizational activity : Coded 1 (yes) if one is a member of an organization and actively participate in its activities at least once in a year, and 0 (no) otherwise.

Control Variables

- Age (in years)

- Educational qualifications in 2010 (five levels according to a standard schema used by Statistics Sweden (1985), entered as dummy variables)

- Civil status distinguishes between single and cohabiting/married persons, and is used as a time-varying covariate (TVC) where we register any changes from couple to single and vice versa.

- Immigrant origin is coded 1 if both parents were born in any country outside Sweden, 0 otherwise.

- Labour market status is also used as a TVC, with four values indicating labour market participation (yes/no) in 2000 and 2010, respectively.

- Global self - rated health in 2000, with three response alternatives: Good, bad, or in between. 7

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the 2 years we study, 2000 and 2010 (percentages in the upper panel; averages, standard deviations, max and min values in the lower panel). Recall that the sample is longitudinal with the same respondents appearing in both years. This means, naturally, that the sample ages 10 years between the waves, the upper age limit being pushed up from 65 to 75. Both the change over years and the ageing of the sample have repercussions for their conditions: somewhat more have poor health, for example, fewer lack social support but more lack frequent social relations, and more are single in 2010 (where widows are a growing category). The group has however improved their economic conditions, with a sizeable reduction in poverty rates. Most of the changes are in fact period effects, and it is particularly obvious for the change in poverty—in 2000 people still suffered from the deep recession in Sweden that begun in 1991 and started to turn in 1996/97 (Jonsson et al. 2010 ), while the most recent international recession (starting in 2008/09) did not affect Sweden that much.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables in the LNU panel

N for variables used as change variables pertains to non-missing observations in both 2000 and 2010

The overall decrease in poverty masks changes that our respondents experienced between 2000 and 2010: Table 2 reveals these for the measure of economic deprivation, showing the outflow (row) percentages and the total percentages (and the number of respondents in parentheses). It is evident that there was quite a lot of mobility out of poverty between the years (61 % left), but also a very strong relative risk of being found in poverty in 2010 among those who were poor in 2000 (39 vs. 5 % of those who were non-poor in 2000). Of all our respondents, the most common situation was to be non-poor both years (81 %), while few were poor on both occasions (6 %). Table 2 also demonstrates some small cell numbers: 13.3 % of the panel (9.4 % + 3.9 %), or a good 400 cases, changed poverty status, and these cases are crucial for identifying our models. As in many panel studies based on survey data, this will inevitably lead to some problems with large standard errors and difficulties in arriving at statistically significant and precise estimates; but to preview the findings, our results are surprisingly consistent all the same.

Table 2

Mobility in poverty (measured as economic deprivation) in Sweden between 2000 and 2010

Outflow percentage (row %), total percentage, and number of cases (in parentheses). LNU panel 2000–2010

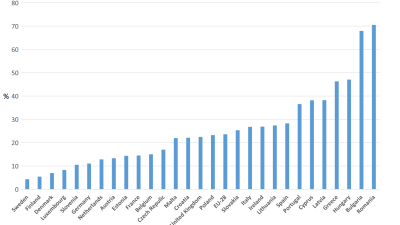

We begin with showing descriptive results of how poverty is associated with our outcome variables, using the economic deprivation measure of poverty. 8 Figure 1 confirms that those who are poor have worse social relationships and participate less in political life and in organizations. Poverty is thus connected with both primary and secondary social relations.

The relation between poverty (measured as economic deprivation) and social relations/participation in Sweden, LNU 2010. N = 5271

The descriptive picture in Fig. 1 does not tell us anything about the causal nature of the relation between poverty and social outcomes, only that such a relation exists, and that it is in the predicted direction: poor people have weaker social relations, less support, and lower levels of political and civic participation. Our task now is to apply more stringent statistical models to test whether the relation we have uncovered is likely to be of a causal nature. This means that we must try to rid the association of both the risk for reverse causality—that, for example, a weaker social network leads to poverty—and the risk that there is a common underlying cause of both poverty and social outcomes, such as poor health or singlehood.

The Change Model

First, as we have panel data, we can study the difference in change across two time-points T (called t 0 and t 1 , respectively) in an outcome variable (e.g., social relations), between groups (i.e. those who changed poverty status versus those who did not). The respondents are assigned to either of these groups on the grounds of entering or leaving poverty; in the first case, one group is non-poor at t 0 but experiences poverty at t 1 , and the change in this group is compared to the group consisting of those who are non-poor both at t 0 and t 1 . The question in focus then is: Do social relations in the group entering poverty worsen in relation to the corresponding change in social relations in the group who remains non-poor? Because we have symmetric hypotheses of the effect of poverty on social outcomes—assuming leaving poverty has positive consequences similar to the negative consequences of entering poverty—we also study whether those who exit poverty improve their social outcomes as compared to those remaining poor. We ask, that is, not only what damage falling into poverty might have for social outcomes, but also what “social gains” could be expected for someone who climbs out of poverty.

Thus, in our analyses we use two different “change groups”, poverty leavers and poverty entrants , and two “comparison groups”, constantly poor and never poor , respectively. 9 The setup comparing the change in social outcomes for those who change poverty status and those who do not is analogous to a so-called difference-in-difference design, but as the allocation of respondents to comparison groups and change groups in our data cannot be assumed to be random (as with control groups and treatment groups in experimental designs), we take further measures to approach causal interpretations.

Accounting for the Starting Value of the Dependent Variable

An important indication of the non-randomness of the allocation to the change and comparison groups is that their average values of the social outcomes (i.e. the dependent variable) at t 0 differ systematically: Those who become poor between 2000 and 2010 have on average worse social outcomes already in 2000 than those who stay out of poverty. Similarly, those who stay in poverty both years have on average worse social outcomes than those who have exited poverty in 2010. In order to further reduce the impact of unobserved variables, we therefore make all comparisons of changes in social outcomes between t 0 and t 1 for fixed t 0 values of both social outcome and poverty status.

As we use dichotomous outcome variables, we get eight combinations of poverty and outcome states (2 × 2 × 2 = 8), and four direct strategic comparisons:

- Poverty leavers versus constantly poor, positive social outcome in 2000 , showing if those who exit poverty have a higher chance of maintaining the positive social outcome than those who stay in poverty

- Poverty leavers versus constantly poor, negative social outcome in 2000 , showing if those who exit poverty have a higher chance of improvement in the social outcome than those who stay in poverty

- Poverty entrants versus never poor, positive social outcome in 2000 , showing if those who enter poverty have a higher risk of deterioration in the social outcome than those who stay out of poverty, and

- Poverty entrants versus never poor, negative social outcome in 2000 , showing if those who enter poverty have a lower chance of improvement in the social outcome.

Thus, we hold the initial social situation and poverty status fixed, letting only the poverty in 2010 vary. 10 The analytical strategy is set out in Table 3 , showing estimates of the probability to have frequent social relations in 2010, for poverty defined (as in Table 2 and Fig. 1 above) as economic deprivation.

Table 3

Per cent with frequent social relations in “comparison” and “change” groups in 2000 and 2010, according to initial value on social relations in 2000 and poverty (measured as economic deprivation) in 2000 and 2010

LNU panel 2000–2010. N = 3083

The figures in Table 3 should be read like this: 0.59 in the upper left cell means that among those who were poor neither in 2000 nor in 2010 (“never poor”, or 0–0), and who had non-frequent social relations to begin with, 59 % had frequent social relations in 2010. Among those never poor who instead started out with more frequent social relations, 90 per cent had frequent social relations in 2010. This difference (59 vs. 90) tells us either that the initial conditions were important (weak social relations can be inherently difficult to improve) or that there is heterogeneity within the group of never poor people, such as some having (to us perhaps unobserved) characteristics that support relation building while others have not.

Because our strategy is to condition on the initial situation in order to minimize the impact of initial conditions and unobserved heterogeneity, we focus on the comparisons across columns. If we follow each column downwards, that is, for a given initial social outcome (weak or not weak social relations, respectively) it is apparent that the outcome is worse for the “poverty entrants” in comparison with the “never poor” (upper three lines). Comparing the change group [those who became poor (0–1)] with the comparison group [never poor (0–0)] for those who started out with weak social relations (left column), the estimated probability of frequent social relations in 2010 is 7 % points lower for those who became poor. Among those who started out with frequent relations, those who became poor have a 17 % points lower probability of frequent relations in 2010 than those who stayed out of poverty.

If we move down Table 3 , to the three bottom lines, the change and comparison groups are now different. The comparison group is the “constantly poor” (1–1), and the change group are “poverty leavers” (1–0). Again following the columns downwards, we can see that the change group improved their social relations in comparison with the constantly poor; and this is true whether they started out with weak social relations or not. In fact, the chance of improvement for those who started off with non-frequent social relations is the most noteworthy, being 33 % units higher for those who escaped poverty than for those who did not. In sum, Table 3 suggests that becoming poor appears to be bad for social relations whereas escaping poverty is beneficial.

Expanding the Model

The model exemplified in Table 3 is a panel model that studies change across time within the same individuals, conditioning on their initial state. It does away with time-constant effects of observed and unobserved respondent characteristics, and although this is far superior to a cross-sectional model (such as the one underlying Fig. 1 ) there are still threats to causal interpretations. It is possible (if probably unusual) that permanent characteristics may trigger a change over time in both the dependent and independent variables; or, put in another way, whether a person stays in or exits poverty may be partly caused by a variable that also predicts change in the outcome (what is sometimes referred to as a violation of the “common trend assumption”). In our case, we can for example imagine that health problems in 2000 can affect who becomes poor in 2010, at t 1 , and that the same health problems can lead to a deterioration of social relations between 2000 and 2010, so even conditioning on the social relations at t 0 will not be enough. This we handle by adding control variables, attempting to condition the comparison of poor and non-poor also on sex, age, highest level of education (in 2010), immigrant status, and health (in 2000). 11

Given the set-up of our data—with 10 years between the two data-points and with no information on the precise time ordering of poverty and social outcomes at t 1 , the model can be further improved by including change in some of the control variables. It is possible, for example, that a non-poor and married respondent in 2000 divorced before 2010, triggering both poverty and reduced social relations at the time of the interview in 2010. 12 There are two major events that in this way may bias our results, divorce/separation and unemployment (because each can lead to poverty, and possibly also affect social outcomes). We handle this by controlling for variables combining civil status and unemployment in 2000 as well as in 2010. To the extent that these factors are a consequence of becoming poor, there is a risk of biasing our estimates downwards (e.g., if becoming poor increases the risk of divorce). However, as there is no way to distinguish empirically whether control variables (divorce, unemployment) or poverty changed first we prefer to report conservative estimates. 13

Throughout, we use logistic regression to estimate our models (one model for each social outcome and poverty definition). We create a dummy variable for each of the combinations of poverty in 2000, poverty in 2010 and the social outcome in 2000, and alternate the reference category in order to get the four strategic comparisons described above. Coefficients do thus express the distance between the relevant change and comparison groups. The coefficients reported are average marginal effects (AME) for a one-unit change in the respective poverty variable (i.e. going from non-poor to poor and vice versa), which are straightforwardly interpretable as percentage unit differences and (unlike odds ratios or log odds ratios) comparable across models and outcomes (Mood 2010 ).

Regression Results

As detailed above, we use changes over time in poverty and social outcomes to estimate the effects of interest. The effect of poverty is allowed to be heterogeneous, and is assessed through four comparisons of the social outcome in 2010 (Y 1 ):

- Those entering poverty relative to those in constant non-poverty (P 01 = 0,1 vs. P 01 = 0,0) when both have favourable social outcomes at t 0 (Y 0 = 1)