A Review of Culture Shock: Attitudes, Effects and the Experience of International Students

Article sidebar.

- How to Cite

In light of increasing globalization and the rising trend of international study, this paper reviews prominent literature as well as benchmark studies on culture shock, focusing on the experience of international students. First, it takes a look at concepts of the phenomenon, both negative and positive. This is followed by a discussion of the physical and psychosocial effects of culture shock, prior to detailed discussion of international students and their cultural adjustment problems. A number of suggestions are provided for educational institutions as well as international students regarding how best to manage and overcome culture shock.

Full text article

Adler, S.P. (1975). The transitional experience: An alternative view of culture shock. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 15(4): 13-23. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/002216787501500403

Andrade, S.M. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2): 131-154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240906065589

Ayyoub, M., S. Khan & A. Riaz (2019). Qualitative analysis of cultural adjustment issues in Austria. New Horizons, 13(1): 31-50.

Befus, P.C. (1988). A multilevel treatment approach for culture shock experienced by sojourners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 12(1): 381-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(88)90032-6

Bochner, S. (2003). Culture shock due to contact with unfamiliar cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture(1): 1-12.

Church, T.A. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3): 540-572. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540

David, H. K. (1971). Culture shock and the development of self-awareness. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 4(1): 44-48. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/BF02110274

Egenes, J.K. (2012). Health care delivery through a different lens: The lived experience of culture shock while participating in an international educational program. Nurse Education Today, 32(1): 760-764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.011

Furnham, A. (1984). Tourism and culture shock. Annals of Tourism Research, 11(1): 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(84)90095-1

Furnham, A. (2010). Culture shock: Literature review, personal statement and relevance for the South Pacific. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 4(2): 87-94. https://doi.org/10.1375/prp.4.2.87

Garza-Guerrero, A. C. (1974). Culture shock: Its mourning and the vicissitudes of identity. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 22(2): 408-429. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F000306517402200213

Hailu, T.E., and H. Ku (2014). The adaptation of the Horn of Africa immigrant students in higher education. The Qualitative Report, 19(28): 1-19. Retrieved 20 May 2022 from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss28/1

Kelly, P., J. Moores & Y. Moogan (2012). Culture shock and higher education performance: Implications for teaching. Higher Education Quarterly, 66(1): 24-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2011.00505.x

Levy, D. (2000). The shock of the strange, the shock of the familiar: Learning from study abroad. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 4(1): 75-83.

Lombard, A.C. (2014). Coping with anxiety and rebuilding identity: A psychosynthesis approach to culture shock. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(2): 174-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.875887

Mahmud, Z., S. Amat, S. Rahman & M.N. Ishak (2010). Challenges for international students in Malaysia: Culture, climate and care. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7: 289-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.10.040

Marsh, L. (2012). Unheard Stories: Narrative Enquiry of the Cross-cultural Adaptation Experiences of Refugee Women in Metro Vancouver [Master’s thesis]. Colwood, BC, Canada: Royal Roads University. Retrieved 20 May 2022 from https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=TC-BRC-511&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=1032911558

Martin, N.J. (1986). The relationship between student sojourner perceptions of intercultural competencies and previous sojourn experience. Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association, USA, November 1986 [oral presentation]. Retrieved 20 May 2022 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED280089.pdf

Mesidor, K.J. & F.K. Sly (2016). Factors that contribute to the adjustment of international students. Journal of International Students, 6(1): 262-282.

Oberg, K. (1954). Culture shock. Women’s Club of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [oral presentation]. Retrieved 20 May 2022 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.461.5459&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Oberg, K. (1960). Cultural shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments. Curare, 29(2): 142-146. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F009182966000700405

Pandian, A. (2008). Multiculturalism in higher education: A case study of Middle Eastern students’ perceptions and experiences in a Malaysian University. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 4(1): 33-59.

Pantelidou, S. & K.J.T. Craig (2006). Culture shock and social support: A survey in Greek migrant students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(1): 777-781. Retrieved 20 May 2022 from https://rdcu.be/cNXZi

Popadiuk, N. & N. and Arthur (2004). Counseling international students in Canadian schools. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 26(2): 125-145. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ADCO.0000027426.05819.44

Samovar, A.L., E.R. Porter, R.E. McDaniel & S.C. Roy (2013). Communication between Cultures (8th Edition). Boston: Cengage.

Stewart, L. & A.P. Legga (1998). Culture shock and travelers. Journal of Travel Medicine,5(1): 84-88.

Ward, A.C., S. Bochner & A. Furnham (2001). The Psychology of Culture Shock. Routledge.

Winkelman, M. (1994). Cultural shock and adaptation. Journal of Counseling and Development, 73(1): 121-126. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb01723.x

Xiaoqiong, H. (2008). The culture shock that Asian students experience in immersion education. Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education, 15(1): 101-105. https://doi.org/0.1080/13586840701825378

Xue, F. (2018). Factors that Contribute to Acculturative Stress of Chinese International Students [unpublished manuscript]. Retrieved 20 May 2022 from https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=major-papers

Yan, K. & C.D. Berliner (2011). Chinese international students in the United States: Demographic trends, motivations, acculturation features and adjustment challenges. Asia Pacific Education Review, 12(2): 173-184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-010-9117-x

Zapf, K.M. (1991). Cross-cultural transitions and wellness: Dealing with culture shock. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 14(1): 105-119. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117730

van der Zee, K. & P.J. van Oudenhoven (2013). Culture shock or challenge? The role of personality as a determinant of intercultural competence. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(6): 928-940. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022022113493138

Zhou, Y., D. Jindal-Snape, K. Topping & J. Todman (2008). Theoretical models of culture shock and adaptation in international students in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 33(1): 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701794833

Yusra Mustafa, 620 Ferguson Rd. Milton, Ontario, Canada

Yusra Mustafa is a linguist and dedicated ELT professional with seven years' experience teaching English and linguistics. She was first in her master's class (English), going on to enroll in an MPhil program (English linguistics), which she completed in 2019. Yusra has publications in Critical Discourse Analysis, ELT and sociolinguistics, but her main areas of interest are cross-cultural communication and education-abroad programs. The former is the topic of her MPhil dissertation. She has presented her papers in international conferences. As part of her current job as lecturer at COSTI, she is among the frontline workers who help newcomers adjust to life in Canada.

Copyright (c) 2022 Journal of Intercultural Communication

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Copyright / Open Access Policy: This journal provides immediate free open access and is distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . This is an open-access journal, which means readers can access it freely. Readers may read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles for any lawful purpose without seeking prior permission from the publisher or author. This is consistent with the Budapest Open Access Initiative's (BOAI) definition of open access.

Article Details

Similar Articles

- Mohammed Juma Alkharusi, Reynaldo Gacho Segumpan, I wish that I could have friends: The Intercultural Friendship Experience of Omani Students at US Universities , Journal of Intercultural Communication: Vol. 24 No. 1 (2024)

- Ming Xie , Chin-Chung Chao, The Interplay between Social Media and Cultural Adjustment: Analysis of the Subjective Well-Being, Social Support, and Social Media Use of Asian International Students in the U.S. , Journal of Intercultural Communication: Vol. 22 No. 2 (2022)

- Elena V. Chudnovskaya, Diane M. Millette, Understanding Intercultural Experiences of Chinese Graduate Students at U.S. Universities: Analysis of Cross-Cultural Dimensions , Journal of Intercultural Communication: Vol. 23 No. 1 (2023)

- Hui Wen Sun, Zhenyi Li , Norliana Hashim, Jen Sern Tham , Rosmiza Bidin , Superficial Causes of AUM Theory Affect Uncertainty and Anxiety among Students in a High-Context Culture , Journal of Intercultural Communication: Vol. 23 No. 4 (2023)

- Tzu Yiu Chen, The Chinese Intercultural Competence Scale and the External Factors of Spanish as a Foreign Language , Journal of Intercultural Communication: Vol. 23 No. 3 (2023)

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this article.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ann Glob Health

- v.87(1); 2021

Resiliency, Stress, and Culture Shock: Findings from a Global Health Service Partnership Educator Cohort

Dr. kiran mitha.

1 Seed Global Health, Boston, MA, US

2 David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, US

Sadath Ali Sayeed

3 Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA, US

Maria Lopez

4 Formerly affiliated with Seed Global Health, US

Associated Data

Background:.

Global health field assignments for medical and nursing professionals include a wide variety of opportunities. Many placements often involve individuals practicing in settings very different from their home environments, relying on their professional experience to help bridge cultural and clinical divides.

Objectives:

There is limited information about the individual factors that might lead to successful longer-term global health experiences in non-disaster settings. In this paper, we report on one cohort of health professionals’ experiences of culture shock, stress, and resiliency as volunteers within the Global Health Service Partnership (GHSP), a public-private collaboration between Seed Global Health, the US Peace Corps, and the US Presidents Plan for Emergency Aids Relief (PEPFAR) that placed American medical and nursing educators in five African countries facing a shortage of health professionals.

Using the tools of Project PRIME (Psychosocial Response to International Medical Electives) as a basis, we created the GHSP Educator Support Survey to measure resiliency, stress, and culture shock levels in a cohort of GHSP volunteers during their year of service.

In our sample, participants were likely to experience lower levels of resiliency during initial quarters of global health placements compared to later timepoints. However, they were likely to experience similar stress and culture shock levels across quarters. Levels of preparedness and resources available, and medical needs in the community where the volunteer was placed played a role in the levels of resiliency, stress, and culture shock reported throughout the year.

Conclusion:

The GHSP Educator Support Survey represented a novel attempt to evaluate the longitudinal mental well-being of medical and nursing volunteers engaged in intense, long-term global health placements in high acuity, low resource clinical and teaching settings. Our findings highlight the need for additional research in this critical area of global health.

Introduction

Global health field assignments for medical and nursing professionals include a wide variety of opportunities. Many placements often involve individuals practicing in settings very different from their home environments, relying on their professional knowledge to help naturally bridge cultural and clinical divides. Academic institutions and non-governmental organizations have increasingly invested resources in preparing healthcare professionals for the demands of working internationally, yet many of these resources are geared toward trainees in short-term immersion experiences, rather than professionals embedded in local communities for prolonged periods of time [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. A robust body of literature has previously described the negative mental health outcomes of individuals working long-term in disaster relief settings such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Few studies, however, have evaluated individual factors that might lead to successful long-term global health experiences in non-disaster settings.

Culture shock is a term often used to encompass the feelings of anxiety or discomfort a person experiences in an unfamiliar social environment [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. The “stage theory” of culture shock includes a five-stage model: honeymoon, frustration, adjustment, acceptance, and reentry. A study of culture shock in social workers placed within rural communities in Canada determined the temporal progression through the five stages and demonstrated a curvilinear relationship between lack of well-being (culture shock) and time, with the lowest well-being at month 6 of placement and return to baseline well-being at month 12 [ 13 ]. While culture shock is commonly reported during global health placements [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ], this curvilinear relationship has not been documented in long-term medical volunteers.

In addition to stress from cultural unfamiliarity, healthcare providers experience work-related stress that can significantly impact their well-being. Stress may lead to negative clinical consequences, such as medical errors, compassion fatigue, and unprofessionalism [ 20 ]. Stress can also lead to negative personal consequences, such as chronic fatigue, substance abuse, mental distress, and suicidal ideation [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. This can be particularly heightened in settings where individuals are physically separated from their usual sources of support – friends, family, and community in their home countries.

A growing body of literature has evaluated the ability of resilience to counterbalance stress and burnout among healthcare workers. Resilience refers to an individual’s ability to overcome adversity and is a multifactorial construct that varies based on characteristics such as age, gender, time, and context [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Two areas previously identified as particularly challenging for healthcare workers are working in areas of resource deprivation and working in remote or rural areas, both of which apply to many settings where international healthcare workers are deployed [ 28 ]. Importantly, resilience is not a static internal quality but can be improved or worsened by environment. Studies of disaster relief workers have shown that contextual factors that improve resiliency may include pre-departure training, team-building efforts, in-country support and recognition, and formal re-entry assistance [ 29 ].

In this paper, we report on one cohort of health professionals’ experiences of culture shock, stress, and resiliency as volunteers within the Global Health Service Partnership (GHSP). GHSP was a public-private collaboration between Seed Global Health, the US Peace Corps, and the US Presidents Plan for Emergency Aids Relief (PEPFAR) that placed American medical and nursing educators in five African countries facing a shortage of health professionals between 2013–2018. Characteristics of the Global Health Service Partnership (GHSP) program included immersion into moderate to high acuity clinical settings, responsibilities of caring for a high volume of patients while providing trainee education, language differences, frequent limitations in available medical and human resources, diagnostic unfamiliarity with local diseases, and different hierarchical structures for clinical personnel.

During the initial years of the GHSP program, multiple survey tools were developed to understand areas of needed programmatic support and quality improvement for the unique circumstances of practicing medical and nursing educators. In 2016, we aimed to combine these tools with validated questionnaires to specifically assess resiliency, stress, and culture shock. Based on pilot survey data and internal consensus, we chose to evaluate individual pre-departure preparation, previous clinical and teaching experience in both underserved domestic and international settings, familial circumstances, and resource variability across placements as unique factors of the GHSP experience.

Concurrently, an ongoing multi-institutional study called Project PRIME (Psychosocial Response to International Medical Electives) was developed by the Midwest Consortium of Global Child Health Educators in 2015 to evaluate medical trainee experiences during short-term global health electives around readiness, stress, and culture shock [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. It included previously validated tools—the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10) to measure resiliency, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) to measure stress, and a modified version of the “Culture Shock Profile” questionnaire to evaluate culture shock. With permission, we adapted the validated tools from the PRIME protocol with our existing GHSP questionnaires and formulated the GHSP Educator Support Survey.

In July 2016, 70 educators were deployed to partner sites in Liberia, Malawi, Swaziland, Tanzania, or Uganda for a period of one year and all were initially invited to participate in this study. The GHSP Educator Support Survey consisted of five surveys shared with GHSP educators before, during, and after their service. The first survey (pre-service) was administered to educators during their orientation week in Washington DC, with the following three surveys (Q1, Q2, Q3) administered quarterly to volunteers during their in-country placements. The final survey (post-service) was administered 3 months after completing their service ( Figure 1 ). Quarterly surveys were selected in order to capture multiple points in the year-long placement and progression through the stages of culture shock without putting undue survey burden on GHSP educators. Surveys were administered electronically, and all data was de-identified. Quarterly response rates varied from 54–69%, with the exception of the post-service survey, which had a response rate of 39% ( Figure 1 ). Data was cleaned and analyzed using SPSS.

Survey timeline and participant responses.

Although frequencies and means are reported for all survey responses, statistical analyses were conducted only for individuals who completed all five surveys (n = 12) and who had scores for the Resiliency, Stress, and Culture Shock Profile scales for all timepoints.

Sample demographics and professional characteristics

The majority of respondents to all five surveys were nurses (67%), similar to the breakdown between nurse and physician educators in the overall GHSP cohort. In addition, half of respondents were married or partnered volunteers (50%), with the majority of spouses/partners accompanying educators to their country of service (67%). Members of the sample group were more likely to have children above the age of 18 (58%), with 8% of respondents with children under 18, and 33% of respondents without children. Most were not immigrants or children of immigrants to the US and spoke only one language. The majority had not previously visited their country of placement and did not know the local language spoken at their sites ( Table 1 ).

Key sample and overall cohort demographics.

* n = 6. ^ n = 16. ** n = 46.

In their last position before becoming a GHSP educator, the majority of participants (58%) worked in high acuity settings (inpatient or emergency) and were responsible for clinical and/or classroom teaching (75%). Most participants had previous experience working in low-resource settings domestically (83%), although a smaller percentage had clinical experience in an international setting (25%) ( Table 1 ).

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10) consisted of a series of ten statements measuring agreement on areas such as ability to adapt to changes, coping with stress, staying focused and being able to handle life’s difficulties. Possible agreement options range from 0 (Not true at all) to 3 (Often true). Answers were then summed to generate a resiliency score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 30 points. Participants with higher scores are said to have higher resiliency. Participant’s resiliency levels were assessed across all five surveys.

For the subset of participants who completed all five surveys, resiliency score averages stayed mostly the same during service, dipping slightly in Q1, but increasing steadily thereafter, with the highest resiliency scores being reported during the post-test ( Figure 2 ).

Average resiliency scores across time, sample group.

For this group, however, there were statistically significant differences across medians for resiliency ( Figure 3 ). Resiliency scores in Q1 (Mdn = 27) were statistically significantly lower than in Q3 (Mdn = 28, Z = –2.063, p = 0.039) and in the post-departure timepoint (Mdn = 28.5, Z = –2.541, p = 0.011). In addition, Q2 Resiliency scores (Mdn = 26) were statistically significantly lower than Post Resiliency scores (Mdn = 28) ( Z = –2.162, p = 0.031).

Resiliency score medians across time, sample group.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) consisted of a series of ten questions, assessing how often participants have felt able to cope effectively with stress in the recent past. Agreement options range from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very often). Answers are then summed to generate a stress score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher stress levels. Participant’s stress levels were assessed across all five surveys.

Overall, the average stress score across timepoints for the subset of participants who completed all five surveys was 11.66 out of 40. Stress levels for GHSP educators peaked in Q1, and decreased to below average levels in both Q3 and post-service ( Figure 4 ).

Average stress scores across time, sample group.

For this group, no statistically significant differences across assessment time points were found.

Culture shock

The Culture Shock Profile Questionnaire measured the intensity with which participants experienced a series of 33 positive and negative feelings. The intensity of the feeling was measured from 0 (None) to 3 (Great). Answers were then summed to generate a culture shock score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 99. The higher the scores, the more culture shock the participants experienced. Culture shock was measured every quarter once participants were in their placement (Q1–Q3) and once participants finished their service and left their service site (post) to assess for reverse culture shock.

Overall, culture shock score averages for the subset of participants who completed all five surveys were highest in Q2, decreasing in Q3 and increasing slightly again during the post-service survey ( Figure 5 ).

Average culture shock scores across time, sample group.

For this group, however, no statistically significant differences were found across the assessment time points.

On sub-analysis, significant differences in the levels of culture shock were found by participants during Q1, based on self-reported levels of feelings of preparedness for their teaching role during their GHSP year during the pre-test survey (χ2(2) = 6.317, p = 0.042). The median Q1 culture shock score for the group that reported feeling somewhat prepared was 27, while the median culture shock score for the group that reported feeling very prepared was 11.

Associations

Correlation analyses were conducted using data from the subset of participants who completed all five surveys to determine if there were any significant associations between educator characteristics and other variables such as resiliency and culture shock scores.

Self-reported levels of preparedness at the predeparture timepoint correlated with resiliency in multiple quarters (Q2 and Q3). Low levels of preparedness at the predeparture timepoint correlated with high levels of culture shock throughout the year and even after their return to the US. Respondents who felt overwhelmed by the medical needs in their community reported higher levels of stress and culture shock across quarters (Q1 and Q3) as well as lower levels of resiliency (Q1, Q2, post). Educators with sufficient teaching resources felt higher levels of stress to provide adequate education to their students across quarters (Q1–Q3) compared to educators without sufficient teaching resources. Higher resiliency levels across the year correlated with respondents feeling fully reintegrated in their home culture on their return to the US ( Table 2 ).

Correlation analyses results, sample group.

The GHSP Educator Support Survey represented a novel attempt to evaluate the longitudinal mental well-being of medical and nursing volunteers engaged in intense, long-term global health placements in high acuity, low resource clinical and teaching settings. Given the competing professional demands of work and challenges around internet connectivity, our response rate for completing all 5 surveys was low (12 out of 70 participants). Thus, our results must be interpreted with caution. Those educators who may have been experiencing higher levels of stress or culture shock may have been less likely to respond to all 5 surveys, leading to disproportionately positive results in our response sample.

In our sample, participants were likely to experience similar resiliency, stress, and culture shock levels across quarters. This may be due to the limited sample size of the respondents, where average scores may not be reflective of individual variations. The median resiliency scores did decrease during the initial quarters of service, likely reflecting the period of adjustment of individuals to their new professional roles and environment. There may also be robustness of these parameters in the global health volunteer population, which may indicate a potential value of using these tools to assess baseline levels of stress and resiliency as part of the selection process for global health placements. Respondents in our sample had overall high levels of resiliency across timepoints (average 26.4 out of 30), low levels of stress (average 11.66 out of 40), and low levels of culture shock (23.2 out of 99).

Another possible signal from our study suggests the value of adequate self-preparation prior to embarking on long-term global health placements. Resiliency positively correlated to self-reported level of preparedness at the pre-service survey timepoint. Self-preparation was, in addition to the formal 1-month orientation included as part of the GHSP program. This suggests that those individuals with high levels of self-motivation to engage in self-study may fare better during their global health deployments.

Respondents who felt overwhelmed by the medical needs in their community reported higher levels of stress and culture shock across quarters as well as lower levels of resiliency. Although global health placements often prioritize settings with high medical need, additional research needs to be done to determine what factors in the medical setting may specifically impact resiliency. Interestingly, those individuals with sufficient teaching resources also reported increased stress to provide medical education, potentially implying that in settings where educational resources have been prioritized, there is added pressure for educators to perform at a high level.

Lastly, global health programs may benefit from an intentional process for professional reintegration on the completion of deployment, particularly for those individuals who struggle during their placement. Higher resiliency levels across the year correlated with respondents feeling fully reintegrated in their home culture on their return to the US, potentially implying that those with lower resiliency did not reintegrate fully on return to the US.

Our findings highlight the need for further structured study on how global health experiences impact the mental well-being of medical and nursing professionals. Future efforts should also be directed toward better understanding factors that best support healthcare workers in settings that can be anticipated to generate culture shock, stress, and test professional and personal resiliency.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Appendix 1.

Table 3. Additional statistically significant Pearson correlations.

Appendix 2.

Survey tools.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people for their instrumental contributions and support as we developed this study: Elizabeth Cunningham (Massachusetts General Hospital), Katelyn Fleming (Ariadne Labs), Clelia Anna Mannino (Seed Global Health), and Laura Foradori (Health Resources and Services Administration, Health and Human Services). The authors would also like to thank the members of the Midwest Consortium of Global Child Health Educators ( sugarprep.org ) and affiliates who developed and shared their research protocol and assessment tools currently being used for their ongoing Project PRIME study involving medical trainees (Psychosocial Response to International Medical Electives). The Project PRIME protocol and assessment tools were directly adapted for use in our study. The Project PRIME principal investigator is Nicole St Clair (University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health), and other study site leads include the following people: Denise Bothe (Case Western Reserve University), Chuck Schubert and Stephen Warrick (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center), Jennifer Watts (Children’s Mercy Hospitals & Clinics), Megan McHenry (Indiana University School of Medicine), Stephen Merry (Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science), Vanessa McFadden and Samantha Wilson (Medical College of Wisconsin), Mike Pitt, Stephanie Lauden, and Risha Moskalewicz (University of Minnesota), James Conway and Sabrina Butteris (University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health) and Elizabeth Groothuis (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine), all accompanied by additional site collaborators. For questions related to the ongoing Project PRIME study involving medical trainees, please email [email protected] .

The Global Health Service Partnership has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Peace Corps under the terms of Award No. PC-12-05-001. Additional funding has been provided by Seed Global Health. The author(s) in this publication is/are solely responsible for the analysis reflected in this publication.

Funding Statement

The Global Health Service Partnership has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Peace Corps under the terms of Award No. PC-12-05-001. Additional funding has been provided by Seed Global Health.

Funding Information

Competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

All authors had access to the data used in this research study. All authors had a role in analyzing the data collected and in writing this manuscript. The authors in this publication are solely responsible for the analysis reflected in this publication.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Essay on Culture Shock.pdf

People travel abroad for various reasons, mostly as tourists or looking for a job. However, when people stay in a foreign place long enough, their stay is embellished with a little concept called culture shock. This paper explores the phases of culture shock most people go through and how to cope with them.

Related Papers

solid plus62

Prakash Upadhyay

Ethos shock or culture shock comprising its variety of symptoms and outcomes is a completely normal physical and psychological reaction to foreign environments and a part of a successful adaptation process-the best and maybe even the only means to experience and understand foreign cultures. This article argues that the anxiety and stress related to the adaptation process are shocking but the extent of adjustment does not depend on whether the negative symptoms of culture shock are experienced, but how they are coped with. Adaptation in hosts cultures can be made through different learning processes rather than single learning process that can have positive outcomes in the end, by serving as a hint that something is not right and therefore motivating thinking about how to adjust that can help reduce ethnocentrism and increase acceptance of cultural diversity and appreciation of cultural integrity relating to the challenges of an unfamiliar environment. It is important for spoon-fed theoretically nurtured Nepalese students to grow through this discomfort in order to understand them better and to gain new sensitivities that encourages personal and intercultural competency developments, positive learning experiences leading to increased self-awareness and personal growth in a comparatively developed pragmatic host culture.

Adrian Furnham

Crossing cultures can be a stimulating and rewarding adventure. It can also be a stressful and bewildering experience. This thoroughly revised and updated edition of Furnham and Bochner's classic Culture Shock (1986) examines the psychological and social processes involved in intercultural contact, including learning new culture specific skills, managing stress and coping with an unfamiliar environment, changing cultural identities and enhancing intergroup relations.

What is it like being a sojourner in a foreign country? Do 'foreigners' do as well as 'natives'? How well do they cope with the culture of the country in which they are studying? Is there much evidence of psychological distress among sojourners, be they businessmen, diplomats, missionaries, the military or students? Foreign and exchange students have been the topic of academic research for a very long time (Bock, 1970; Brislin, 1979; Byrnes, 1966; Furnham & Tresize, 1983; Tornbiorn, 1982; Zwingmann & Gunn, 1963).

European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management

Diana Petkova

Experiencing culture shock in a foreign culture is not a weakness or negative indication of future international success. Culture shock including its variety of symptoms and outcomes is a completely normal physical and psychological reaction to foreign environments and a part of successful adaptation process-the best and may be even the only means to experience and understand foreign cultures. The anxiety and stress related to the adaptation process are shocking but the extent of adjustment does not depend on whether the negative symptoms of culture shock are experienced, but how they are coped with. Adaptation in the culture of hosts can be made through different learning processes rather than single learning process that can have positive outcomes in the end, by serving as a hint that something is not right and therefore motivating thinking about how to adjust that can help reduce ethnocentrism and increase acceptance of cultural diversity and appreciation of cultural integrity relating to the challenges of an unfamiliar environment. It is important for spoon-fed theoretically nurtured Nepalese students to grow through this discomfort in order to understand them better and to gain new sensitivities that encourages personal and intercultural competency developments, positive learning experiences leading to increased self-awareness and personal growth in a comparatively developed pragmatic host culture.

Romanian Economic and Business Review

Ana Mihaela Istrate

In a multicultural world, where students and professionals have numerous opportunities to travel for business and academic reasons, a set of skills for coping with culture shock is absolutelymandatory. Starting from an understanding of Hofstede's definition of culture as "the collective programming of the human mind", and continuing with Lysgaard"s U-curve of Culture Shock, the present study offers solutions for coping with adaptation problems in a new cultural environment. Based on a set of interviews with international students that experienced the U curve and the W-curve of culture shock, during their international study programs, we will be able to offer better solutions for the problems encountered while being away from the cultural comfort zone.

Howell Madelo

Julio Noyola

Archives of Business Research

Rini Susanti , Indawan Syahri, University of Muhammadiyah Palembang , Diah Ayu Rafika

The purpose of this study is to investigate various aspects of culture shock experienced by foreign workers and how they deal with culture shock. The study further documented various aspects of culture shock such as language, environment, friends at work, food, dress etc., and also how to deal with it. The data were collected from 4 subjects through a semi-structured interviews via WhatsApp with Indonesian who worked in various countries (Lebanon, Australia, Malaysia, and Japan). One of the major findings of this study is that Indonesian foreign workers who worked overseas experienced cultural shock both in similar and different aspects of culture shock. Six aspects among the ten were experienced by all of the four subjects. Meanwhile, the rest four aspects were only experienced by some of them. This study documented ten different categories of culture shock aspects that can be experienced by people while they are working in foreign countries.

RELATED PAPERS

Kimberly Gabriela

Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Nobuhito Yagi

British Journal of Surgery

Willem Bemelman

Niculescu Titu

Adriana Rybicka

zubair afzal IYI

Cuadernos de Herpetología

Jorge Williams

Revista Palmas

Edison Steve Daza

Nelson Sturtz

Saintika Medika

Caesar Ensang Timuda

International Journal of Telerehabilitation

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science

esty kurniawati

Moha Yacoubi

Psychological Reports

Ricardo Burg Ceccim

francesco girelli

Alergia e Imunologia: abordagens clínicas e prevenções

maria eduarda

Clinical Infectious Diseases

Motiur Rahman

International Journal of Research in Engineering and Innovation

Editor IJREI

American University of International Law Review

Carter Dillard

Henry Brandhorst

Juan A Módenes Cabrerizo

Pamela J I M É N E Z Draguicevic

Dialogues d'histoire ancienne

Emma Gonzalez Gonzalez

Grant Webby

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Culture Shock

Learning objectives.

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- define ethnocentrism, culture shock and cultural relativism

- understand the causes of culture shock

- describe the stages of cultural adaptation

- recognize common symptoms of culture shock

- critique the standard U-shaped model of cultural adaptation and the term “culture shock”

Ethnocentrism, Culture Shock, and Cultural Relativism

Information in this section has been adapted from Chapter 3.1: What is Culture in Introduction to Sociology – 2nd Canadian Edition by William Little [1] , which is made available by OpenStax College and BCcampus Open Education under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Despite how much humans have in common, cultural differences are far more prevalent than cultural universals. For example, while all cultures have language, analysis of particular language structures and conversational etiquette reveals tremendous differences. In some Middle Eastern cultures, it is common to stand close to others in conversation. North Americans keep more distance, maintaining a large personal space. Even something as simple as eating and drinking varies greatly from culture to culture. If your professor comes into an early morning class holding a mug of liquid, what do you assume she is drinking? In Canada, it’s most likely filled with coffee, not Earl Grey tea, a favourite in England, or yak butter tea, a staple in Tibet.

The way cuisines vary across cultures fascinates many people. Some travellers, like celebrated food writer Anthony Bourdain, pride themselves on their willingness to try unfamiliar foods, while others return home expressing gratitude for their native culture’s cusine. Canadians might express disgust at other cultures’ cuisine, thinking it is gross to eat meat from a dog or guinea pig for example, while they do not question their own habit of eating cows or pigs. Such attitudes are an example of ethnocentrism , or evaluating and judging another culture based on how it compares to one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism, as sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) described the term, involves a belief or attitude that one’s own culture is better than all others (1906). Almost everyone is a little bit ethnocentric. For example, Canadians tend to say that people from England drive on the “wrong” side of the road, rather than the “other” side. Someone from a country where dogs are considered dirty and unhygienic might find it off-putting to see a dog in a French restaurant.

A high level of appreciation for one’s own culture can be healthy; a shared sense of community pride, for example, connects people in a society. But ethnocentrism can lead to disdain or dislike for other cultures, causing misunderstanding and conflict. People with the best intentions sometimes travel to a society to “help” its people, seeing them as uneducated or backward, essentially inferior. In reality, these travellers are guilty of cultural imperialism — the deliberate imposition of one’s own cultural values on another culture. Europe’s colonial expansion, begun in the 16th century, was often accompanied by a severe cultural imperialism. European colonizers often viewed the people in the lands they colonized as uncultured savages who were in need of European governance, dress, religion, and other cultural practices. On the West Coast of Canada, the Aboriginal potlatch (gift-giving) ceremony was made illegal in 1885 because it was thought to prevent Aboriginal peoples from acquiring the proper industriousness and respect for material goods required by civilization. A more modern example of cultural imperialism may include the work of international aid agencies who introduce modern technological agricultural methods and plant species from developed countries while overlooking indigenous varieties and agricultural approaches that are better suited to the particular region.

Culture shock may appear because people are not always expecting cultural differences. Anthropologist Ken Barger discovered this when conducting participatory observation in an Inuit community in the Canadian Arctic (1971). Originally from Indiana, Barger hesitated when invited to join a local snowshoe race. He knew he’d never hold his own against these experts. Sure enough, he finished last, to his mortification. But the tribal members congratulated him, saying, “You really tried!” In Barger’s own culture, he had learned to value victory. To the Inuit people winning was enjoyable, but their culture valued survival skills essential to their environment: How hard someone tried could mean the difference between life and death. Over the course of his stay, Barger participated in caribou hunts, learned how to take shelter in winter storms, and sometimes went days with little or no food to share among tribal members. Trying hard and working together, two nonmaterial values, were indeed much more important than winning.

During his time with the Inuit, Barger learned to engage in cultural relativism. Cultural relativism is the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards rather than viewing it through the lens of one’s own culture. The anthropologist Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) argued that each culture has an internally consistent pattern of thought and action, which alone could be the basis for judging the merits and morality of the culture’s practices. Cultural relativism requires an open mind and a willingness to consider, and even adapt to, new values and norms. The logic of cultural relativism is at the basis of contemporary policies of multiculturalism. However, indiscriminately embracing everything about a new culture is not always possible. Even the most culturally relativist people from egalitarian societies, such as Canada — societies in which women have political rights and control over their own bodies — would question whether the widespread practice of female genital circumcision in countries such as Ethiopia and Sudan should be accepted as a part of a cultural tradition.

Sometimes when people attempt to rectify feelings of ethnocentrism and develop cultural relativism, they swing too far to the other end of the spectrum. Xenocentrism is the opposite of ethnocentrism, and refers to the belief that another culture is superior to one’s own. (The Greek root word xeno , pronounced “ZEE-no,” means “stranger” or “foreign guest.”) An exchange student who goes home after a semester abroad or a sociologist who returns from the field may find it difficult to associate with the values of their own culture after having experienced what they deem a more upright or nobler way of living.

Sociologists attempting to engage in cultural relativism may struggle to reconcile aspects of their own culture with aspects of a culture they are studying. Pride in one’s own culture does not have to lead to imposing its values on others. Nor does an appreciation for another culture preclude individuals from studying it with a critical eye. In the case of female genital circumcision, a universal right to life and liberty of the person conflicts with the neutral stance of cultural relativism. It is not necessarily ethnocentric to be critical of practices that violate universal standards of human dignity that are contained in the cultural codes of all cultures, (while not necessarily followed in practice). Not every practice can be regarded as culturally relative. Cultural traditions are not immune from power imbalances and liberation movements that seek to correct them.

Culture Shock

Culture shock occurs when an individual confronts another culture. Culture shock is a perfectly normal, emotional reaction that may include feelings of depression, anxiety, or disorientation and that may even manifest itself physically by affecting an individual’s health or their sleeping or eating habits.

The U-Shape Model of Culture Shock

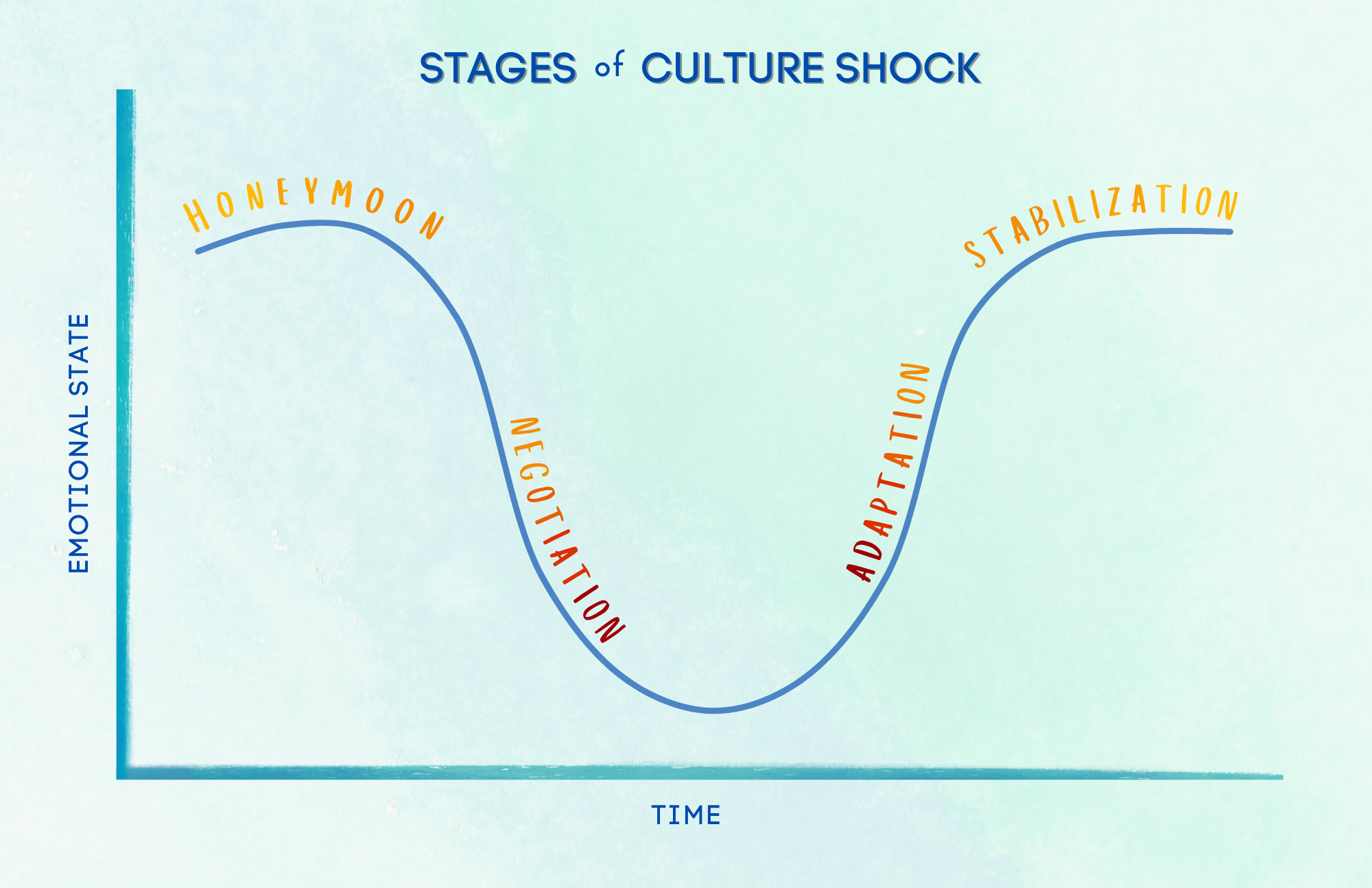

Many people have seen diagrams of culture shock that look like this [2] :

In the initial honeymoon stage, the cultural newcomer is in love with their new surroundings. The host culture seems ideal. Every interaction and experience in the host culture is exciting and interesting.

In stage two, reality sets in. In the negotiation (or “slump”) stage, the cultural newcomer starts to experience difficulties in the host culture. They may compare the host culture with their home culture and may judge the new culture harshly. This is the stage we most commonly associate with the term “culture shock”. Culture shock can manifest itself in both physically and psychologically. People suffering from culture shock may experience general and unexplained exhaustion. They may sleep far more than what is normal for them, or they may have insomnia and be unable to sleep. They may overeat or eat much less than they normally would and might gain or lose weight as a result. They might overindulge in alcohol or experiment with other risky behaviour that is out of the ordinary for them. They may be more concerned than usual about getting ill and may notice minor aches, pains and cold symptoms more than they normally would and may in fact experience more colds and stomach aches than normal. They may experience feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression. They may withdraw from social events and feel lonely and homesick.

In stage three, the adjustment or realization stage, the newcomer starts to adapt to the new culture. They begin to gain a deeper understanding of the host culture and become more competent at performing basic tasks, like getting groceries and using public transportation, and start to feel more at home in the new culture.

The final stage in this model, the stabilization or adaptation stage, assumes that the cultural newcomer becomes fully acculturated to the host culture. The cultural newcomer has fully adapted to the host culture.

This short video [3] describes each stage in more detail and provides tips on how to achieve cultural adaptation:

Issues with the U-Shaped Model

Some researchers argue that the U-shaped model is deeply flawed and overly simplistic. The concept of the “adjustment” phase is especially problematic.

Hofstede [4] , notes that the fourth stage is not the same for everyone. While some cultural newcomers will stabilize, or adapt, to the host cultures, some will reject the host culture and some will assimilate to the host culture.

If a cultural newcomer adapts, they have achieved a kind of cultural hybridity. They are bicultural in that they have developed a new cultural identity in addition to their original cultural identity, and they can access these different identities to function in different cultural situations.

If a newcomer rejects the host culture, they have failed to adapt. They may spend most of their time with people of their own culture and will avoid interacting with locals and experiencing local food or other customs. They have no desire to “fit in” with the host culture. They may feel quite negatively toward the host culture and may choose to return home.

On the other hand, the newcomer may completely assimilate to the host culture. In this case, they feel themselves to be a member of the host culture and this new cultural identity almost supersedes their original cultural identity. They can speak the language and have adopted local mannerisms. They may even feel disdain for their home culture and may feel superior to other cultural newcomers.

Other researchers [5] complain the term “culture shock” has become a bit of a meaningless buzzword. These researchers prefer the term “ transition stress ” as it reinforces the idea that there are a variety of ways that adjustment challenges may present themselves when an individual has moved from their home culture to a host culture. These adjustment challenges may result in stress not simply because the individual has encountered a new culture; rather, because of the experience of the culture, the individual may be experiencing identify shifts, role changes, small difficulties and confusion in completing normal daily tasks, competing emotions of excitement and trepidation, an inability to understand the actions and viewpoints of others, and a mentally draining re-evaluation of existing values, behaviours and worldviews.

To learn more about “transition stress,” read this short article in Psychology Today : https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/between-cultures/201603/understanding-transition-stress

The level of stress and types of stress triggers will depend on why the individual has changed cultures; for example, if a person has relocated for employment, they may experience stress related to acclimating to a new work environment and may also need to manage conflicting loyalties to their home office and their new office. Students may experience difficulties adjusting to different academic standards and workloads and may also have additional emotional challenges as they strive to maintain relationships with friends and family in their home country while simultaneously trying to become part of a new social circle. The U-shaped model also does not consider other important factors, including gender, age, situational differences, or the length of the sojourn. Certainly a tourist, a refugee and an international student will all have different experiences of culture shock.

The other issue with the U-Shaped model is that does not explain how or why adjustment challenges occur, and it seems to assume a correlation between adjustment and emotional happiness.

Consider what you’ve learned about culture shock.

- How might you identify if a classmate has culture shock?

- If you think you or someone you know is suffering from culture shock, what should you do?

- How can you avoid, or at least alleviate, some of the negative aspects of culture shock?

- Which “transition” in your move abroad will be the most difficult for you to cope with?

Cultural Adaptation

In this presentation [6] , an Indian student studying in Finland describes her acculturation journey:

How has this student’s experiences been similar to or different from your own?

Additional Resources

As cited by Little:

Barger, K. (2008). “Ethnocentrism.” Indiana University . Retrieved from http://www.iupui.edu/~anthkb/ethnocen.htm.

Barthes, R. (1977). “Rhetoric of the image.” In, Image, music, text (pp. 32-51). New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

Berger, P. (1967). The sacred canopy: Elements of a theory of religion . New York, NY: Doubleday.

Darwin, C. R. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex . London, UK: John Murray.

DuBois, C. (1951, November 28). Culture shock [Presentation to panel discussion at the First Midwest Regional Meeting of the Institute of International Education. Also presented to the Women’s Club of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, August 3, 1954].

Fritz, T., Jentschke, S., Gosselin, N., Sammler, D., Peretz, I., Turner, R., . . . Koelsch, S. (2009). Universal recognition of three basic emotions in music. Current Biology, 19(7). doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.058.

Kymlicka, W. (2012). Multiculturalism: Success, failure, and the future. [PDF] Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.upf.edu/dcpis/_pdf/2011-2012/forum/kymlicka.pdf.

Murdock, G. P. (1949). Social structure . New York, NY: Macmillan.

Oberg, K. (1960). Cultural shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments. Practical Anthropology, 7, 177–182.

Smith, D. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology . Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals. New York, NY: Ginn and Co.

Suggestions for additional reading:

Gilmore, K. (2016, November 3). Why we need to embrace culture shock – Kistofer Gilmour – TEDxTownsville [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGSD6jduFJg .

Grothe, T. (2022, May 17). 6.2: Managing culture shock. In Exploring intercultural communication . LibreTexts Project. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Butte_College/Exploring_Intercultural_Communication_(Grothe)/06%3A_Culture_Shock/6.02%3A_Managing_Culture_Shock

Saphiere, D. H. (2014, August 12). The nasty (and noble) truth about culture shock – and ten tips for alleviating it. Cultural Detective Blog . https://blog.culturaldetective.com/2014/08/12/the-nasty-and-noble-truth-about-culture-shock/ .

- Little, W. (2016, October 5). Chapter 3: Culture. In Introduction to sociology (2nd Canadian ed.). BCcampus Open Education. https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology2ndedition/chapter/chapter-3-culture /↵ ↵

- Veillieux, H. (2022, April 12). StagesOfCultureShock-graph_v2 [Digital Image]. Confederation College. https://bit.ly/3jylwLF . CC BY 4.0 . ↵

- The Global Society. (2019, August 27). Culture shock and the cultural adaptation cycle: What it is and what to do about it [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-ef-xhC_bU . ↵

- Hofstede, Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations : Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ↵

- Berardo, K., & Deardorff, D. K. (2012). Building cultural competence : Innovative activities and models . Stylus Pub. ↵

- Student Talks. (2017, November 13). The process of cultural adaptation - Priyanka Banerjee [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=diPmFgSNENY . ↵

Intercultural Business Communication Copyright © 2021 by Confederation College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Culture Shock?

Understanding culture shock, the 4 stages of culture shock, how to overcome culture shock.

- Culture Shock FAQs

The Bottom Line

- Business Essentials

Culture Shock Meaning, Stages, and How to Overcome

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/troypic__troy_segal-5bfc2629c9e77c005142f6d9.jpg)

Investopedia / Ryan Oakley

Culture shock refers to feelings of uncertainty, confusion, or anxiety that people may experience when moving to a new country or experiencing a new culture or surroundings. This cultural adjustment is normal and is the result of being in an unfamiliar environment.

Culture shock can occur when people move to another city or country, such as when retiring abroad . Culture shock can also occur when people go on vacation, travel in retirement or for business, or study abroad for school. For example, international students studying abroad for a semester in another country may experience a cultural adjustment due to an unfamiliarity with the weather, local customs, language, food, and values.

Although the timing of each person's adjustment process can be different, there are specific phases that most people go through before they adjust to their new environment. Culture shock can be quite stressful and lead to anxiety. However, it's possible to overcome it and grow as a result.

Key Takeaways

- Culture shock refers to feelings of uncertainty, confusion, or anxiety that people may experience when moving to a new country or surroundings.

- Culture shock can occur when people move to a new city or country, go on vacation, travel abroad, or study abroad for school.

- A cultural adjustment is normal and is the result of being in an unfamiliar environment.

- Culture shock is typically divided into four stages: the honeymoon, frustration, adaptation, and acceptance stage.

- Over time, people can become familiar with their new surroundings as they make new friends and learn the customs, leading to an appreciation of the culture.

Culture shock occurs when an individual leaves the comfort of their home and familiar surroundings and moves to an unfamiliar environment. The adjustment period can be fairly intense, particularly if the two locations are completely different, such as going from a small rural area to a large metropolis or moving to another country. People can also experience culture shock when moving from one place to another within the same country.

Typically, no single event causes culture shock, nor does it occur suddenly or without reason. Instead, it gradually builds from a series of incidents, and culture shock can be difficult to identify while struggling with it.

The feeling is particularly intense at the beginning and can be tough to overcome. It's important to remember that the cultural adjustment usually dissipates over time as a person becomes more familiar with a place, the people, customs, food, and language. As a result, navigation of surroundings gets easier, friends are made, and everything becomes more comfortable.

The adjustment process due to culture shock can get better over time, leading to growth and an appreciation of the new environment.

Symptoms of Culture Shock

Culture shock can produce a range of symptoms, which can vary greatly from person to person in terms of scope and intensity. These may include:

- Being homesick

- Feeling helpless

- Feeling isolated

- Disorientation

- Lack of concentration

- Irritability

- Sleep or eating disturbances

People who experience culture shock may go through four phases that are explained below.

The Honeymoon Stage

The first stage is commonly referred to as the honeymoon phase. That's because people are thrilled to be in their new environment. They often see it as an adventure. If someone is on a short stay, this initial excitement may define the entire experience. However, the honeymoon phase for those on a longer-term move eventually ends, even though people expect it to last.

The Frustration Stage

People may become increasingly irritated and disoriented as the initial glee of being in a new environment wears off. Fatigue may gradually set in, which can result from misunderstanding other people's actions, conversations, and ways of doing things.

As a result, people can feel overwhelmed by a new culture at this stage, particularly if there is a language barrier. Local habits can also become increasingly challenging, and previously easy tasks can take longer to accomplish, leading to exhaustion.

Some of the symptoms of culture shock can include:

- Frustration

- Homesickness

- Feeling lost and out of place

The inability to effectively communicate—interpreting what others mean and making oneself understood—is usually the prime source of frustration. This stage can be the most difficult period of cultural adjustment as some people may feel the urge to withdraw.

For example, international students adjusting to life in the United States during study abroad programs can feel angry and anxious, leading to withdrawal from new friends. Some experience eating and sleeping disorders during this stage and may contemplate going home early.

The Adaptation Stage

The adaptation stage is often gradual as people feel more at home in their new surroundings. The feelings from the frustration stage begin to subside as people adjust to their new environment. Although they may still not understand certain cultural cues, people will become more familiar—at least to the point that interpreting them becomes much easier.

The Acceptance Stage

During the acceptance or recovery stage, people are better able to experience and enjoy their new home. Typically, beliefs and attitudes toward their new surroundings improve, leading to increased self-confidence and a return of their sense of humor.

The obstacles and misunderstandings from the frustration stage have usually been resolved, allowing people to become more relaxed and happier. At this stage, most people experience growth and may change their old behaviors and adopt manners from their new culture.

During this stage, the new culture, beliefs, and attitudes may not be completely understood. Still, the realization may set in that complete understanding isn’t necessary to function and thrive in the new surroundings.

A specific event doesn't cause culture shock. Instead, it can result from encountering different ways of doing things, being cut off from behavioral cues, having your own values brought into question, and feeling you don't know the rules.

Time and habit help deal with culture shock, but individuals can minimize the impact and speed the recovery from culture shock.

- Be open-minded and learn about the new country or culture to understand the reasons for cultural differences.

- Don't indulge in thoughts of home, constantly comparing it to the new surroundings.

- Write a journal of your experience, including the positive aspects of the new culture.

- Don't seal yourself off—be active and socialize with the locals.

- Be honest, in a judicious way, about feeling disoriented and confused. Ask for advice and help.

- Talk about and share your cultural background—communication runs both ways.

What Is the Definition of Culture Shock?

Culture shock or adjustment occurs when someone is cut off from familiar surroundings and culture after moving or traveling to a new environment. Culture shock can lead to a flurry of emotions, including excitement, anxiety, confusion, and uncertainty.

Is Culture Shock Good or Bad?

Although it may have a seemingly negative connotation, culture shock is a normal experience that many people go through when moving or traveling. While it can be challenging, those who can resolve their feelings and adjust to their new environment often overcome culture shock. As a result, cultural adjustment can lead to personal growth and a favorable experience.

What Is an Example of Culture Shock?

For example, international students that have come to the United States for a study abroad semester can experience culture shock. Language barriers and unfamiliar customs can make it challenging to adjust, leading some students to feel angry and anxious. As a result, students can withdraw from social activities and experience minor health problems such as trouble sleeping.

Over time, students become more familiar with their new surroundings as they make new friends and learn social cues. The result can lead to growth and a new appreciation of the culture for the study abroad student as well as the friends from the host country as both learn about each other's culture.

What Are the Types of Culture Shock?

Culture shock is typically divided into four stages: the honeymoon, frustration, adaptation, and acceptance stage. These periods are characterized by feelings of excitement, anger, homesickness, adjustment, and acceptance. Note that some people might not go through all four phases and might not reach the acceptance phase. They might experience difficulties adjusting, which could create permanent introversion or other forms of social and behavioral reactions.

If you've travelled abroad for a while or moved overseas , you may have experienced a bout of culture shock. Things that people in other places take for granted or habits and customs that they practice may be so foreign to you that they "shock" your system. While this could put an initial damper on your international travels, remember that culture shock can be overcome by being open-minded and accustomed to the way things are done that differ from back home.

Bureau Of Educational And Cultural Affairs. " Exchange Programs ."

Brown University. " Office of International Programs, Culture Shock ."

University of the Pacific. " Common Reactions to Culture Shock ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1922468884-7f210a12d45c4440a744715d8a3f0801.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Finished Papers

Constant customer Assistance

Jam Operasional (09.00-17.00)

+62 813-1717-0136 (Corporate) +62 812-4458-4482 (Recruitment)

How can I be sure you will write my paper, and it is not a scam?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Ioana Cupsa. Culture shock involves a powerful, transformative process that takes place at both the individual and societal levels as important cultural forces are clashing. This article provides an account of the impact that culture shock has on individual identity and invites reflection on the social implications of culturally diverse ...

credited with coining the term " culture shock ", defines it as "the anxiety that results from. losing all our familiar signs and symbols of social intercourse.". This review analyzes ...

Acculturation, Culture Shock, and Identity Transformation A Thesis Proposal Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International and Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in International & Multicultural Education by Lai Yan Vivyan Lam December 2017

The Journal of Intercultural Communication (JICC) is an international, double-blind peer-reviewed, open-access journal focused on the study of linguistic and cultural communication in a globalized world. Covering areas such as business, military, science, education, media, and tourism, JICC aims to foster constructive communication across diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

The Culture Shock Profile Questionnaire measured the intensity with which participants experienced a series of 33 positive and negative feelings. The intensity of the feeling was measured from 0 (None) to 3 (Great). Answers were then summed to generate a culture shock score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 99.

values such as these after experiencing culture shock is a common one that has really affected the way that Cofer chooses who she wants to be identified as. Although Cofer seems to have her mind set on American culture, this decision seems to be out of anger, which makes it temperamental verses permanent. There are many moments

Essay on Culture Shock.pdf. Snezana Djuric. People travel abroad for various reasons, mostly as tourists or looking for a job. However, when people stay in a foreign place long enough, their stay is embellished with a little concept called culture shock. This paper explores the phases of culture shock most people go through and how to cope with ...

A sense of loss and feelings of deprivation in regard to friends, status, profession and possessions. Being rejected by/and or rejecting members of the new culture. Confusion in role, role expectations, values. Surprise, anxiety, even disgust and indignation after becoming aware of cultural differences.

The most influential and widely known theory is Reverse Culture Shock, also known as the W-curve theory (Gullahorn & Gullahorn, 1963). It is a theoretical addition to the initially developed ...

CULTURE SHOCK AND ADAPTATION TO THE U.S. CULTURE by Stefanie Theresia Baier Thesis Submitted to the Teacher Education Department Eastern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Educational Psychology with a concentration in Personality Development Thesis Committee:

1. I NTRODUCTION. The goal of the project was to study the effects of culture shock and reverse culture. shock on students and workers from various countries. We decided to do the study by ...

In stage two, reality sets in. In the negotiation (or "slump") stage, the cultural newcomer starts to experience difficulties in the host culture. They may compare the host culture with their home culture and may judge the new culture harshly. This is the stage we most commonly associate with the term "culture shock".

Key Areas to Describe. Culture shock academic essays provide detailed examples of emotional reactions, surprises, challenges, and cultural learning across aspects of the new environment, like: Communication dynamics such as language barriers, sociology, etiquette and non-verbal styles. Societal customs, norms, taboos, and etiquette in areas ...

Culture Shock: A feeling of uncertainty, confusion or anxiety that people experience when visiting, doing business in or living in a society that is different from their own. Culture shock can ...

many books, journal, etc. To cope with the problems regarding culture shock, people need to enrich their knowledge about new culture and use some strategies or important way to deal it. Culture shock definitions . Nowadays, there are many related definitions of culture shock but they nearly convey a similar meaning. Culture shock was introduced ...

Thesis Statement: There are many positive effects of culture shock, such as meeting new people, knowing about personality and increasing the knowledge. Body: 1. Meeting new people a. Public places b. Help to know about new country and culture 2. Knowing about personality a. Be independent b. Own abilities.

Based on the two causes of culture shock showed by international students. above, it was coherence with Ernofalina's (2017) studi ed that different language. barrier, learning styles and methods ...

This term expresses the lack of direction, the feeling of not knowing what to do or how to do things in a new environment, and not knowing what is appropriate or inappropriate. The feeling of culture shock can usually set in after the first few weeks of arriving in a new country. Personally, I have experienced a language culture shock when I ...

Thesis Statement Culture Shock - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. thesis statement culture shock

Thesis Statement: Culture shock is a significant psychological and emotional experience that affects individuals when they encounter a new culture. Understanding the causes and consequences of culture shock is important for individuals who are relocating to a new country or region. ... In conclusion, culture shock is a complex and challenging ...

Thesis Statement: There are many positive effects of culture shock, such as meeting new people, knowing about personality and increasing the knowledge. Body: 1. Meeting new people a. Public places b. Help to know about new country and culture 2. Knowing about personality a. Be independent b. Own abilities.

One of the major findings of this study is those Indonesian foreign workers who worked overseas experienced cultural shock both in similar and different aspects of culture shock. Six aspects of ...

Getting an essay writing help in less than 60 seconds. 132. Customer Reviews. Jam Operasional (09.00-17.00) +62 813-1717-0136 (Corporate) +62 812-4458-4482 (Recruitment) Essay, Research paper, Coursework, Term paper, Questions-Answers, Research proposal, Discussion Board Post, Powerpoint Presentation, Case Study, Book Report, Rewriting ...