clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

The fight for the future of transgender athletes

A group of influential women’s sports advocates say their proposals are about fairness. but lgbt activists say their plans would endanger transgender rights — and transgender lives..

The women timed their announcement carefully, holding it the day before National Girls and Women in Sports Day, created three decades ago to promote female athletes.

Among them were trailblazers: Donna de Varona, the Olympic swimmer who lobbied for Title IX’s passage in 1972; Donna Lopiano, the former chief executive of the Women’s Sports Foundation; and Nancy Hogshead-Makar, Olympic swimmer and law professor who wrote a book on Title IX.

Before that day in early February, they were universally respected as pioneers in the long fight for women’s equality in sports. Then they unveiled their project: changing the way transgender girls and women participate in women’s sports. Almost immediately, their proposal drew bitter criticism in the fraught debate over transgender rights.

For starters, they said, they planned to lobby for federal legislation requiring transgender girls and women, in high school sports and above, to suppress testosterone for at least one year before competing against other girls and women, making universal a policy already in place in some states and some higher levels of sports. For transgender girls in high school who do not suppress testosterone, they suggested “accommodations,” such as separate races, podiums or teams.

They called themselves the Women’s Sports Policy Working Group .

“To give girls and women an equal opportunity to participate in sports, they need their own team. Why? Because of the biological differences between males and females,” said Hogshead-Makar, CEO of Champion Women, a women’s sports advocacy organization.

They portrayed their proposals as a science-based compromise between two extremes: right-wing politicians seeking wholesale bans of transgender athletes and transgender activists who argue for full inclusion — and who even dispute what some view as settled science about the relationship between testosterone and athleticism. They quickly drew fierce backlash, illustrating how the issue of transgender athletes has become the most vexing, emotionally charged debate in global sports and why it may prove impossible for schools and sports organizations to craft policies that are both fair to all female athletes and fully inclusive of transgender girls and women.

Transgender and women’s equality activists denounced their proposals as transphobic and accused the women of having a myopic focus on sports at a critical time for the transgender equality movement — as the Biden administration fights to expand federal anti-discrimination protections for transgender people and as conservative lawmakers push bills in more than 20 states seeking to ban transgender athletes and criminalize gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender youth.

Critics also pointed to members of the working group with reputations of engaging in anti-trans rhetoric, including Martina Navratilova, the tennis champion whose commentary on transgender athletes has stoked outrage, and a Duke law professor whose work calling transgender girls and women “biological males” is cited in anti-transgender legislation.

Inside the world of sports — where careers are built on split-second wins and governed by rules that measure testosterone by the nanomole — these women’s proposals have gained some surprising voices of support. They have drawn endorsements from the first openly transgender Division I cross-country runner in NCAA history as well as a leading transgender scientist researching the effects of hormone therapy on athleticism. With enduring credibility in the sports world and on Capitol Hill, they have begun meeting with state and federal lawmakers grappling with this issue.

But even advocates who view their proposed policies as sensible for collegiate and professional athletes wonder whether these women have truly grappled with the impact their policies would have on the lives of hundreds, perhaps thousands of transgender girls across the country.

“The folks who are pushing these anti-trans bills … they don’t believe transgender people exist. They think they’re faking it for an advantage in sports,” said Cathryn Oakley, state legislative director at the Human Rights Campaign. “I don’t know how you find a middle ground between a hate group and people pushing for equality.”

A patchwork of policies

Before 2010, few college or high school athletic associations had policies on transgender athletes, according to a report published that year by the Women’s Sports Foundation and the National Center for Lesbian Rights.

Noting that “an increasing number of high school and college-aged young people are identifying as transgender,” the report proposed a set of policies: In college sports, transgender women should undergo one year of hormone therapy before competing against other women, a rule rooted in scientific research that suggested such an approach would mitigate any athletic benefits. The NCAA quickly adopted the policy.

For high schools, the report recommended letting transgender girls compete in sports as soon as they transition socially and begin dressing and acting in accordance with their gender identity. Requiring hormone therapy for adolescents is potentially harmful, experts said in interviews, because not all transgender teens have supportive families or access to gender clinics. Ones who do may not want to undergo hormone therapy, which for transgender girls typically involves puberty blockers that pause developmental changes followed by a combination of testosterone suppressors and estrogen.

According to information compiled by transathlete.com and the ACLU , 10 states let transgender girls compete in high school sports after undergoing some treatment. Twelve states prohibit them entirely, including four that passed new laws and executive orders this year. Nine states have no policies at all. And 19 states, as well as the District of Columbia, let them compete regardless of testosterone level.

For the past decade, this policy patchwork has developed largely without controversy. Transgender youth are a very small minority of the U.S. population — 1.8 percent of high school students, according to a 2019 CDC report — and the number of those transgender girls likely to play sports and compete at an elite level is even smaller.

But then, a few years ago, a transgender runner took the Connecticut track scene by storm, catching the attention of politicians, pundits and advocates — including Lopiano, a Connecticut resident and Title IX champion.

Running on the boys’ team as a ninth-grader in suburban Hartford, Terry Miller was an average track athlete, online records show, failing to qualify for any postseason events. But in 2018, Miller came out as a transgender girl. In her first season running against other girls, as a sophomore, Miller dominated. She won five state championships and two titles at the New England championships, beating the fastest girls from six states.

The next fall, as a junior, Miller won another four state titles and two more all-New England titles. In several races, she was followed closely by Andraya Yearwood, another transgender girl who had also won three state titles.

In interviews, Miller and her supporters discussed how important track was for her confidence and stability as she transitioned.

“Track helps me forget about everything, and I love it,” Miller said in a 2019 story on DyeStat, a website that covers high school track and field. (Miller and her parents declined an interview request for this story.)

Support for Miller, however, was not unanimous. Girls who lost to her and their coaches complained that she had an unfair advantage. Parents of other girls started online petitions demanding state high school officials add a testosterone suppression requirement for transgender girls.

I’m not saying transgender girls are going to take over women’s sports. I’m saying that the law protects girls and women, and they shouldn’t have to compete against someone who has an immutable testosterone-based advantage. — Donna Lopiano, Title IX advocate

A lawyer representing a few mothers contacted Lopiano and asked for help. Believing Connecticut’s policy violated Title IX, Lopiano met with state officials and attempted to broker a compromise that would allow the results of transgender runners not to affect the results of cisgender girls.

Title IX doesn’t define what it means to be a girl or a woman. But Lopiano argues Congress intended to restrict female sports to girls and women who haven’t gone through male puberty, when testosterone in boys surges to between four and 10 times the levels found in girls and women.

She points to the 1975 testimony of Bernice Sandler, an activist known as “the godmother of Title IX,” who told Congress that, because of physical advantages men acquire during puberty, any effort to integrate sports between the sexes “would effectively eliminate opportunities for women.”

“I’m not saying transgender girls are going to take over women’s sports,” Lopiano said. “I’m saying that the law protects girls and women and they shouldn’t have to compete against someone who has an immutable testosterone-based advantage.”

Lopiano’s compromise never materialized. The mothers decided instead to work with the Alliance Defending Freedom, an Arizona-based conservative Christian advocacy organization that supports anti-trans lawsuits and legislation across the country. The Alliance helped three girls who lost races to Miller and Yearwood sue Connecticut high school authorities, arguing their policy on transgender athletes violated Title IX. The case is pending in U.S. District Court in Connecticut.

The ACLU has intervened on behalf of the transgender runners. In an interview, Chase Strangio, deputy director for transgender justice at the ACLU, said courts already have found Title IX protections apply to transgender girls and women in cases involving access to women’s restrooms. He views restrictions on transgender athletes in high school, such as hormone requirements, as discriminatory and probably a violation of the law.

Miller did not begin suppressing testosterone until her junior year, Strangio acknowledged, but Yearwood was on hormone therapy throughout high school. Regardless, Strangio emphasized that his clients didn’t win every race they competed in and they quit the sport after high school.

“Their careers were sabotaged by the rhetoric and the attacks on them,” Strangio said.

In early 2019, Lopiano began meeting regularly with de Varona and Hogshead-Makar to discuss what they believe are looming collisions between the transgender equality movement and Title IX. To them, the Connecticut controversy illustrated what they view as the two extreme positions between which they are trying to navigate.

The Alliance Defending Freedom argues that transgender girls and women always have physiological advantages in sports, even if they have suppressed testosterone. Their advocacy has inspired a wave of legislation across the country targeting transgender athletes since 2019.

“You can’t change a person’s biological sex,” said Christiana Holcomb, an Alliance lawyer working on the Connecticut case. “Nothing can undo the physiological advantages that come from being born biologically male.”

Strangio and the ACLU dispute whether transgender girls and women have advantages in sports, even if they’re not suppressing testosterone. Other prominent transgender activists, making this same argument, have called for the NCAA to remove its testosterone suppression requirement.

“The truth is, transgender women and girls have been competing in sports at all levels for years, and there is no research supporting the claim that they maintain a competitive advantage,” a 2019 ACLU article noted.

“Athleticism is complex,” Strangio said. Referring to Lopiano and her colleagues, he added, “I’m not a scientist, and neither are any of them.”

A growing research field

Benjamin Levine, a professor of cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, is one of the world’s leading experts on the science of athletic performance. The founder and director of the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, one of the largest institutes of its kind in the world, Levine has published hundreds of peer-reviewed papers and consulted for the NCAA, the NFL, World Athletics and NASA.

In an interview, Levine said he understands why this topic stirs intense emotions. But, he said, there is no debate over whether post-pubescent transgender teenage girls and women have advantages in sports until they suppress testosterone.

Regardless of gender identity, Levine said, people who go through puberty with male levels of testosterone, on average, will grow taller and stronger than cisgender girls and women, with more muscle mass, larger hearts and advantages in several other physiological factors that affect athleticism. Puberty in boys typically begins by 12 and ends by 18.

“This is why, for every single record that you see in athletic competitions, boys and girls before puberty are about the same, and then everything diverges afterward,” said Levine, whose scientific research is cited by the women’s policy group.

Transgender advocates dismiss Levine’s research as irrelevant because he studies cisgender athletes. But several small-scale studies have found transgender women do have physiological advantages until they suppress their testosterone for at least one year.

The first was published in 2004 by Louis Gooren , a Dutch endocrinologist and founder of the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria in Amsterdam, one of the largest transgender health clinics in the world. “Testosterone exposure has profound effects on muscle mass and strength,” wrote Gooren, who reported that as he gave more testosterone to 19 transgender men, they saw marked increases in muscle growth, as well as hemoglobin and insulinlike growth factor levels, both relevant in athletic performance. As he suppressed testosterone in 17 transgender women, the opposite occurred: Their muscles shrank, and their hemoglobin and IGF levels dropped.

Gooren’s findings were essentially replicated in November by a study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine examining how 29 transgender men and 46 transgender women in the Air Force performed on routine fitness tests — push-ups, sit-ups and a 1½-mile run — as they transitioned hormonally.

After a year of treatment, transgender men were performing better and the transgender women worse. The transgender women were still running slightly faster than cisgender women, however, so the authors concluded elite sports organizations might need to lengthen testosterone suppression requirements beyond one year. In interviews, two of the study’s authors cautioned against drawing conclusions about high school athletes because their research subjects were all 18 or older.

Other recent research has been conducted by a transgender athlete herself: Joanna Harper, a medical physicist and runner. In 2015, Harper published an analysis of what happened to her and seven other transgender women runners as they transitioned hormonally. Seven of the eight women, including Harper, saw their times slow considerably.

After that, Harper left her job in Portland, Ore., and moved to England to research the effects of hormone treatment on transgender athletes at Loughborough University.

In February, she published a systematic review of 24 studies of the effects of hormone treatment on transgender women. Harper found some athletic benefits — such as higher hemoglobin levels, vital in endurance sports — dissipated after only four months of suppressing testosterone. But other advantages, such as increased muscle area and strength, remained even after 36 months.

Harper has consulted for the International Olympic Committee, World Athletics and other elite sports organizations, where she advocates for allowing transgender girls and women to compete after one year of hormone therapy. She also has signed on as a public supporter of the women’s policy group.

In a recent interview, Harper said she has been called both “the destroyer of women’s sport” and “a traitor to transgender people.”

“My agenda is to pull people toward the middle,” Harper said. “The science leads me there.”

My agenda is to pull people toward the middle. The science leads me there. — Joanna Harper, transgender athlete and researcher

When asked for experts to support his belief that it’s unclear whether transgender girls and women have competitive advantages in sports, the ACLU’s Strangio mentioned two people: Katrina Karkazis and Joshua Safer.

Karkazis is a cultural anthropologist and bioethicist. She has not conducted original research on testosterone and athleticism, but she has written extensively on the subject, including the book, “Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography.”

In an interview, Karkazis emphasized many complexities in scientific research of testosterone and athleticism — testosterone alone doesn’t build a better athlete, researchers have found — but did not dispute that transgender girls and women who do not suppress testosterone have advantages in sports.

“Yes, on average … there will be performance differences that will be better,” she said when pressed on this point. “Whether that’s an advantage or not … I actually think that’s a normative statement that involves a value judgment about what is advantaged.”

Safer is an endocrinologist and the director of a transgender health clinic who has served as an expert witness for the ACLU. In court filings, Safer has acknowledged transgender girls and women with higher levels of testosterone will have advantages in sports. But, he has noted, these advantages are less pronounced in high school.

“Testosterone begins to affect athletic performance at the start of puberty, and those effects increase each year until about age 18,” Safer wrote in a statement challenging a law barring transgender athletes in Idaho. “As a result, testosterone provides less of an impact for a 14-, 15- or 16-year-old than it does for a 17- or 18-year-old.”

In an interview, Safer emphasized that, despite the advantages conferred by testosterone, the list of known examples of transgender girls and women succeeding in sports, at any level, is vanishingly short.

There has never been an openly transgender athlete in the Olympics ; the first three, all women, could compete this summer in Tokyo. There has been one openly transgender woman champion in the history of NCAA: CeCe Telfer, a Franklin Pierce University runner who won the Division II 400-meter hurdles in 2019. On the high school level, there are just Miller and Yearwood in Connecticut.

Said Safer, “The important thing to consider here, as it relates to high school sports and teenagers, is are we addressing a problem that actually exists, or are we simply addressing a fear?”

‘Sports does discriminate’

At their opening news conference, Lopiano spoke first and stressed that the group’s proposals represented “respectful inclusion” of transgender athletes.

“These are our kids. And we have to take care of all of them,” she said.

A few minutes later, the women turned the news conference over to one of their lesser-known colleagues: Doriane Lambelet Coleman, a Duke law professor and former elite runner who, in the late 1970s, was one of the first women to receive a track scholarship to Villanova University.

Over the past few years, Coleman has published law review articles and essays defending the preservation of girls’ and women’s sports for athletes with female levels of testosterone.

“I’ve tried to make clear that I support a science-based approach to inclusion, not categorical exclusion,” she said.

But as the debate moves beyond sports and into mainstream politics, more people have begun to see “science-based inclusion” as a form of exclusion. Which is why, to her dismay, her writings are routinely cited by right-wing politicians promoting wholesale bans of transgender athletes. It’s also why some transgender advocates say her and her colleague’s proposals are not only unfair but dangerous.

Research shows that transgender youth struggle with alarmingly high rates of anxiety, depression and suicidality. Emerging research has suggested affirmative transgender care — letting children transition socially for a period of time and then, if prescribed, start hormone therapy — can significantly reduce those mental health problems. A key to affirmative care, experts said, is to avoid situations where a transgender child is treated in any way that invalidates their gender identity.

When briefed on the women’s policy group’s proposals, several experts sharply criticized the idea of transgender-specific sports teams or events as stigmatizing.

“They have to go through so many obstacles just to recognize they are transgender, and for a lot of them, sports is the turning point. … You’d just end up exiling transgender girls from sports,” said Helen Carroll, former director of the Sports Project of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, who co-wrote the NCAA’s policy on transgender athletes.

And even if they do have physiological advantages, some experts argued, transgender teens face a minefield of challenges, including higher rates of bullying, rejection by their families and homelessness.

“The deck is stacked against them in every single way, so, to me, it seems silly to … look at this physiological advantage but not consider all the other substantial disadvantages these kids face,” said Jack Turban, fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine.

De Varona and her peers conceded that their concerns about high school sports are mostly hypothetical. As the legal and social climate for transgender people improves, they believe, more situations similar to what happened in Connecticut may arise.

But when asked to describe the harms that occurred to the girls who lost to the transgender athletes in Connecticut, they struggled to come up with anything concrete. Neither Miller nor Yearwood, the transgender girls, received track scholarships to college, and the women concede they are unaware of any cisgender girls who missed out on a scholarship opportunity as a result of Miller’s and Yearwood’s success.

There was other harm, the women argued, pointing to dozens of girls who lost races or opportunities to advance to postseason meets because they finished behind the transgender girls. Research has shown, they emphasized, that when girls succeed in sports, they’re more likely to go to college and have successful careers.

“Everybody here … has worked their entire lives to make sure that girls and women have equal opportunities in competitive sports,” Hogshead-Makar said.

And in those moments, these women tacitly conceded that, despite their talk of inclusion, they view transgender girls and women as different from the girls and women to whom they have devoted their careers — at least when they’re on the playing field.

“Yes, it’s important for everyone to have that opportunity in athletics,” de Varona said. “But sports does discriminate.”

From the field to the courts

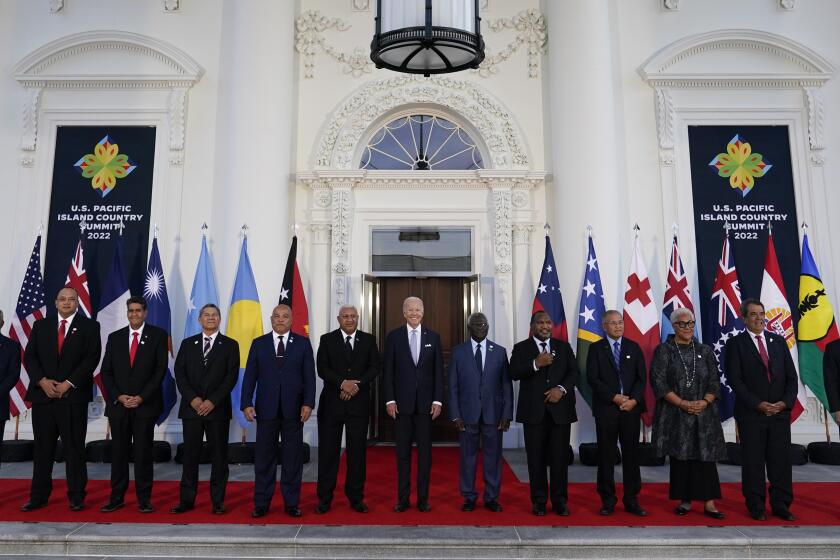

The IOC is revising its guidelines on transgender athletes and is expected to announce them after this summer’s Tokyo Games. The NCAA also is examining its guidelines after hearing concerns from transgender advocates last fall.

The battle over transgender athletes in America’s high schools is likely to be settled, at least in part, in the courts. The ACLU is challenging an Idaho law that banned transgender athletes from competing in any public school, including colleges. The Connecticut lawsuit challenging that state’s policy also must be resolved.

Since its February news conference, the women’s policy group has had conversations with several members of the House and Senate, on both Judiciary Committees, according to Coleman, but they declined to specify whom or how many.

They also acquired a prominent supporter: Juniper Eastwood, one of the first openly transgender women to compete in NCAA Division I sports and the first cross-country runner.

There’s no way it would have been fair. My testosterone levels were so much higher than any of the girls I would’ve been running against. — Juniper Eastwood, the first openly transgender cross-country athlete in NCAA Division I history

In an interview, Eastwood said she never would have competed against girls or women without suppressing her testosterone. In high school, she set a Montana state record in the 800 meters that, had she been running on the girls’ team, would have broken the women’s world record.

“There’s no way it would have been fair,” she said. “My testosterone levels were so much higher than any of the girls I would’ve been running against.”

A closer examination of Eastwood’s personal story, however, spotlights the ramifications of policies that would separate transgender youth from sports.

Eastwood always planned to transition after she finished her track career because she knew she would attract unwanted attention as a transgender runner. But in her sophomore year at the University of Montana, Eastwood got hurt and had to sit out the season. Running had always been her way of coping with gender dysphoria. Without it, Eastwood began drinking excessively and struggled with depression.

Eastwood decided to transition and then continue running track on the women’s team. As she had expected, she got considerably slower as she suppressed her testosterone. And, as she had dreaded, her performances were closely analyzed by right-wing news sites, track and field obsessives and transgender activists.

Eastwood’s senior track season ended abruptly because of the coronavirus . She’s in graduate school at Montana, studying environmental philosophy, and would like to work somewhere outdoors. Even though she feels a little out of shape lately, Eastwood said, she enjoys running now more than she ever did in high school or college.

She lives not far from several secluded trails where she can run for miles without seeing another person. When she runs now, she said, she feels free from the worry about what someone will write online the next day about her performance.

“It’s just me, the trails and no one else,” Eastwood said. “And I can just run.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article described Juniper Eastwood as the first openly transgender athlete in NCAA Division I sports history. Eastwood is o ne of the first openly transgender women to compete in Division I sports and the first to run cross-country. The story has been corrected.

Read more about sports and social issues

“But while Osaka Inc. is thriving, Naomi, the woman, is hurting. Tennis doesn’t seem to be helping. And she doesn’t owe it to anyone to keep trying — not her sponsors, not her fans and not the game.” Read Candace Buckner on Naomi Osaka .

“I can’t escape into sports. Nor should I. I don’t even want to try, even during this most absorbing stretch of the sports calendar. March Madness for me is no competition for the real madness that, while overseas this time, seems oh so close.” Read Kevin B. Blackistone on the war in Ukraine .

“It was all true. The members of the women’s team had been wronged. For years, they had to play more, and win bigger, to be paid anything close to their male counterparts. They got less pay for better work.” Read Sally Jenkins on the USWNT settlement with U.S. Soccer .

“Who’s lying here? Probably, to some degree, both sides. The NFL expecting Snyder to stop lying, covering up, blocking and bullying is a little bit like expecting a poisonous cobra not to bite you. You are who you are.” Read John Feinstein on Daniel Snyder and the NFL .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

I’m Transgender. Here’s How Playing Sports Saved My Life

By Shane Diamond

It would not be an exaggeration to say that sports saved my life.

I grew up in a small town in the American Southwest known as an offbeat refuge for artists and skiers. Locally, the area had a reputation for heroin overdoses, drunk driving fatalities, and high school drop-outs. But after school and on the weekends, my friends and I all played youth sports like soccer and basketball together. Athletics kept us occupied, supervised, and generally out of trouble. We also learned lifelong lessons about accountability, hard work, and time management.

When soccer season ended and the boys started playing ice hockey, I was one of the only girls who was eager to join them; I wanted to do what my friends did. Throughout my youth and into high school, I was often the only girl on the ice, and one of only a handful statewide, but I was welcomed and accepted by both my team and the league. Looking back, it makes sense that I was “one of the boys” because I was a boy, but we didn’t have language or resources to support transgender youth in the early ’90s the way we do today.

After high school, I played varsity women’s ice hockey at Bowdoin College in Maine. I can’t tell you what our record was during my four years of playing college hockey, which team won the league championship, or how many goals I scored, but I can say with absolute assurance that my hockey teammates are still some of my best friends. And that didn’t change after I came out as transgender in 2016 and started transitioning.

We’ve supported each other during marriage and divorce, while caring for ill parents and starting families, and through experiences of racism and discrimination. During the pandemic, we have remained connected online and debated whether or not we’re going to wear pants with elastic waists forever. We share a bond that can only be forged through long hours at the rink and grueling lifting schedules at the gym. We all remember the collective joy of celebrating a win and the shared grief after a loss.

As a kid who didn’t quite fit in, I always found safety and stability among my teammates. When the weight of the outside world felt like it was too heavy for a teenager struggling with identity, I knew that for an hour each day, I could leave it all outside the rink and just play hockey. Then in my 30s, while fighting for sobriety and battling depression, outreach from my college teammates saved my life: They made overt gestures, like flying to Maine when I was approaching rock bottom just so we could lie in a hotel bed, eat Thai food, and watch trashy reality TV. They messaged me on the daily group text where we offer support and accountability.

Only a person who has spent years working out with you can call you up and say, “I love you but you’re being an idiot,” with the sort of bluntness that you know comes from a place of love.

I’m not alone in my experiences. For transgender youth, having access to sports is quite literally life-saving; according to a study recently published by the Center for American Progress, the mere existence of transgender-insluive sports policies lowers the risk of poor mental health and suicidality for trans youth. Even if trans youth don’t participate in sports, the fact that they are able to reduces their risk of depression and attempted suicide. As a community, we need the mental health benefits that sport can offer. The largest survey of transgender people, the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality, reports that transgender people are nine times more likely to attempt suicide over our lifetime than our cisgender peers. And almost 75% of transgender people who attempt suicide are under the age of 18. Even without harmful and invasive laws, it is dangerous to be a young trans person .

But lawmakers in 31 states are preying on this already vulnerable population by trying to pass laws to ban trans kids from playing sports . Politicians are targeting young children who are already coping with trauma after a year of wearing masks and only seeing their classmates on Zoom. They are going after teenagers who, like each of us, miss spending time with their friends without being afraid for the future. They are harming college students who are preparing to enter an economy grappling with unemployment and low wages.

It’s important to note that the majority of these attacks are not coming from cisgender athletes. They overwhelmingly welcome their transgender teammates. Earlier this month, over 550 current student athletes from over 85 U.S. colleges and universities recently — and for the second time — sent a letter to the NCAA in support of transgender student athletes. They know that trans athletes just want to be included. I played hockey as a kid because that’s what my friends were doing and I didn’t want to be left out. These laws and policies don’t just leave out trans kids, they intentionally exclude us.

Transgender athletes are not a new trend: the NCAA has allowed transgender athletes to participate since 2011 and the International Olympic Committee since 2004. But trans kids are still facing pushback. In 2018, transgender Texas wrestler Mack Beggs was forced to compete against girls despite wishing he could wrestle with other boys. The story of his fight to participate and show up as himself, along with the stories of Connecticut runner Andraya Yearwood and New Hampshire skier Sarah Huckman, are featured in the documentary film Changing the Game , for which I am the Impact Change Coordinator. Their stories are powerful examples of what happens when we let kids be themselves, participate fully as students, athletes, friends, and family members. Trans athletes aren’t asking for special treatment, nor do we want to be stigmatized for our transness. We simply want the opportunity to play.

Because of the wave of anti-transgender legislation sweeping the country, trans youth are hearing consistently false and harmful messages about themselves: that our inherent identities are deceptive and unfair, that there’s not enough room for us, that we don’t belong. But I am living proof that there is no better lifeline for trans kids than ensuring they are able to play sports with their peers. We owe it to kids, transgender and cisgender alike, to make sure they have the same opportunities to participate in, fall in love with, and be saved by sports the way so many of us have.

James Factora

Abby Monteil

Call your local schools’ athletic directors and demand that athletic policies allow trans youth to participate as themselves, contact legislators in these 31 states — many of whom have never met a trans person — and tell them why this matters to you and your family. Every young person deserves the chance to learn and grow through the transformative power of sports. Many of these bills and laws will likely make their way to the Supreme Court and hopefully be ruled unconstitutional, but the damage being caused to trans kids in the process will have lasting effects.

When I say that I don’t know where I’d be without sports, I mean it quite literally; without the support networks that have lasted well beyond my time on the ice, I would likely have joined too many of my transgender siblings who felt isolated and excluded enough to end their lives. Trans youth need our support now, loud and proud and in unison, before it’s too late to fight for them.

Shane Diamond is a media and communications maverick. Previously the communications manager at TLDEF, he is now the impact campaign coordinator for the film Changing the Game, a transgender advocate, and former college athlete.

Get the best of what’s queer. Sign up for them.'s weekly newsletter here.

By Jules Gill-Peterson

By Rachel Crandall-Crocker

By Wren Sanders

By James Factora

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Sport and Transgender People: A Systematic Review of the Literature Relating to Sport Participation and Competitive Sport Policies

Bethany alice jones.

1 Nottingham Centre for Gender Dysphoria, 3 Oxford Street, Nottingham, NG1 5BH UK

2 School of Sport, Exercise, and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK

Jon Arcelus

3 Division of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Walter Pierre Bouman

Emma haycraft.

Whether transgender people should be able to compete in sport in accordance with their gender identity is a widely contested question within the literature and among sport organisations, fellow competitors and spectators. Owing to concerns surrounding transgender people (especially transgender female individuals) having an athletic advantage, several sport organisations place restrictions on transgender competitors (e.g. must have undergone gender-confirming surgery). In addition, some transgender people who engage in sport, both competitively and for leisure, report discrimination and victimisation.

To the authors’ knowledge, there has been no systematic review of the literature pertaining to sport participation or competitive sport policies in transgender people. Therefore, this review aimed to address this gap in the literature.

Eight research articles and 31 sport policies were reviewed.

In relation to sport-related physical activity, this review found the lack of inclusive and comfortable environments to be the primary barrier to participation for transgender people. This review also found transgender people had a mostly negative experience in competitive sports because of the restrictions the sport’s policy placed on them. The majority of transgender competitive sport policies that were reviewed were not evidence based.

Currently, there is no direct or consistent research suggesting transgender female individuals (or male individuals) have an athletic advantage at any stage of their transition (e.g. cross-sex hormones, gender-confirming surgery) and, therefore, competitive sport policies that place restrictions on transgender people need to be considered and potentially revised.

Introduction

Transgender people are those who experience incongruence between the gender that they were assigned at birth (based on the appearance of their genitals) and their gender identity/experienced gender. Gender identity, or experienced gender, can be defined as a person’s internal sense of gender, whether this be male, female, neither or somewhere along the gender continuum. Some transgender people, but not all, will choose to affirm their gender identity by socially transitioning (i.e. living as their experienced gender socially, at work or at an educational institution, with friends and family, outside the home) and some, in addition, will choose to medically transition with cross-sex hormones and gender-confirming surgeries [ 1 , 2 ]. Although over time various different terms have been used, the term ‘transgender female individual’ will be used to describe individuals assigned male at birth, based on their genital appearance, but who later identify as female. ‘Transgender male individual’ will be used to describe people who are assigned female at birth, based on their genital appearance, but later identify as male. ‘Cisgender’ will be used to describe people who do not experience incongruence between their gender assigned at birth and their gender identity.

Recent reports indicate that the number of transgender individuals who attend transgender health services has increased substantially over the years in many European countries [ 3 – 5 ]. There has also been a significant increase in the number of people who self-identify as transgender and do not necessarily attend transgender health services [ 6 ]. For example, Kuyper and Wijsen [ 6 ] found that 4.6 % of people who were assigned male at birth and 3.2 % of people who were assigned female at birth in their Dutch population sample reported an ambivalent gender identity (equal identification with the other gender as with the gender they were assigned at birth). The authors also reported that 1.1 % of the people who were assigned male at birth and 0.8 % of the people who were assigned female at birth identified as transgender. It remains unknown how many of these people will seek treatment through a transgender health service. The increase in people who identify as transgender may be at least partly explained by the increase in visibility of transgender people within Western society [ 4 , 5 ]. For example, Caitlin Jenner, a former athlete and current television personality, recently came out as transgender during a television interview that was viewed all over the world [ 7 ]. Increases in visibility may have prompted some people to reflect and question their gender identity [ 8 ].

Some transgender people experience stigma, transphobia, prejudice, discrimination and violence as a consequence of their gender identity [ 9 – 11 ]. Ellis et al. [ 12 ] found that transgender people were more likely to avoid situations when they were afraid of being harassed, identified as transgender or ‘outed’, such as in clothes shops, public toilets and gyms. Gyms are a popular outlet to engage in sport-related physical activities (i.e. gym fitness exercises) and therefore it is important to create an inclusive environment given the established mental and physical health benefits of physical activity and sport [ 13 , 14 ]. This is particularly important for transgender people as they have been found to report a high prevalence of depression and anxiety [ 15 , 16 ], which could be managed with physical activity. Furthermore, physical activity and sport can also contribute towards maintaining the appropriate weight necessary to undergo gender-confirming surgery, acknowledging that not every transgender person will wish to do so [ 1 , 2 , 17 ].

The premise of competitive sport is fairness (i.e. inclusion in the absence of advantage) and, owing to fears surrounding the perceived athletic advantage of transgender people, the question of whether transgender people should be permitted to compete in accordance with their gender identity has been raised and greatly contested within the literature, among sport organisations, fellow competitors and spectators. It is a commonly held belief that androgenic hormones (especially testosterone) confer an athletic advantage in competitive sport. Therefore transgender female individuals, because of high endogenous testosterone levels, are perceived to hold an advantage in sport (when testosterone has not been blocked to a cisgender female level). Transgender men are not thought to possess an athletic advantage, despite being injected with testosterone if they chose to medically transition with cross-sex hormones. However, there has been a paucity of research that has directly explored how androgenic hormone levels are associated with athletic competence in both cisgender and transgender populations (e.g. running time).

To facilitate the inclusion of transgender competitors, in 2004, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) [ 18 ] announced that transgender people could participate in all future Olympic games providing they had fully medically transitioned (i.e. had been prescribed cross-sex hormone treatment for 2 years and undergone gender-confirming surgery). Although the requirements of this policy appear to concur with the commonly held belief that transgender people hold an athletic advantage, they have been criticised for not being underpinned by an evidence-based rationale [ 19 ]. The IOC [ 20 ] has recently updated its policy to be more inclusive of transgender athletes (i.e. fewer restrictions); however, the 2004 policy has been extremely influential on other sport organisations’ policy development. The new (2016) IOC policy will be considered in Sect. 3 .

In an attempt to draw a consensus as to whether transgender people should be able to compete in accordance with their gender identity, in 2005 Reeser [ 21 ] conducted a review of the literature pertaining to gender identity issues in competitive (elite) sport. Reeser paid particular attention to the evolution of gender verification in competitive sport and whether current competitive sport policies for transgender people are fair. He concluded that, while gender verification has made significant advances, there is a lack of physiological performance-related data in transgender people. This is preventing an overall consensus from being made as to whether transgender sport policies are fair or not (i.e. fairness in the absence of advantage). Reeser’s review, although important, has some limitations. He did not adopt a systematic methodology and therefore did not include the majority of transgender sport policies. Additionally, Reeser only considered the implications of such policies in relation to elite competitive sport and did not consider the experiences of transgender people who engage in sport or sport-related physical activity for leisure or fitness (e.g. gym fitness activities, jogging).

With the intention of addressing the limitations of the previous literature review, this systematic review has two aims. First, to systematically analyse and critically review the available literature regarding transgender people’s experiences in relation to competitive sport (elite and recreational) and sport-related physical activity participation (e.g. jogging, gym fitness activities). Second, to systematically review the available transgender competitive sport policies with regard to their fairness (i.e. competition in the absence of advantage). It is hoped that this systematic review will further enhance the understanding of sport participation and competition amongst transgender people. It may be expected that as more people define themselves as transgender, the issues that transgender people experience in competitive sport and sport-related physical activity will become more pronounced. It is therefore important that those who work to facilitate and promote sport and develop policies for their own sport organisations (e.g. sport medicine specialists, sport policymakers) are informed about the issues that this vulnerable population face. This will allow for a non-discriminatory atmosphere in sport, whilst ensuring a fair system for all participants and competitors (regardless of their gender identity).

Search Strategy

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were followed to undertake this systematic review [ 22 ]. To obtain relevant peer-reviewed articles, an electronic search of literature published between January 1966 and August 2015 was conducted using the following search engines: ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Scopus and PubMed. Within each search engine, the following search terms were entered: gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, trans people, trans individual, transgender and transsexual. These terms were combined with three terms relating to sport (physical activity, exercise and sport) using the “AND” operator. The reference lists of eligible papers were searched for potentially relevant publications. Sport policies were obtained through a Google search using the above search terms with the addition of “policy” at the end of all sport-related terms.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To address the first aim, articles that were selected were concerned with the experiences and issues surrounding physical activity and sport participation for transgender people. This systematic review only considered articles eligible if they were research articles, as opposed to discussion papers. Case studies were also considered eligible, as research articles were limited. Peer-reviewed articles that were written in English only were included. For the second aim, all available national and international policies on competitive sport in transgender people were selected and reviewed.

Study Selection

Thirty-one research articles were considered potentially relevant to the remit of this review. The search also identified 31 competitive sport policies for transgender people. After screening the abstracts, ten research articles were excluded as six were concerned with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender sport, one was a Scottish non-academic survey, one was a book chapter, one was concerned with an irrelevant topic and another focused on cisgender participants. The remaining 21 articles were downloaded for full-text review and 13 papers were excluded as they were discussion papers, as opposed to research articles. Therefore, eight research articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were consequently included within this systematic review (Fig. 1 ). All 31 competitive sport policies for transgender people were reviewed and included within this systematic review.

Process of identifying eligible research articles. LGBT : lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender

This section presents the findings from the research articles and sport policies included within this systematic review. First, the findings from the research articles that explored participation in sports (both elite and recreational standards) and sport-related physical activities (i.e. gym fitness activities, jogging) are provided. Second, findings from the reviewed competitive sport policies relating to transgender inclusion are given.

Transgender People and Sport Participation

Characteristics of the eligible research studies.

The oldest research article included was published in 2004 [ 23 ] and the most recent publication was from 2015 [ 24 ]. The majority of the studies were qualitative in nature, all of which employed interviews [ 24 – 29 ]. The remaining two research articles included an experimental study [ 23 ] and a cross-sectional survey [ 30 ]. Most of the studies were concerned with transgender people who participated in sport competitively, at an elite or recreational level [ 21 , 23 , 25 – 29 ]. Some authors focused on a specific sport; ice hockey, netball and softball [ 26 , 28 , 29 ] while others were concerned with transgender people engaging in any sport [ 25 , 27 , 29 ]. Broadly, across all sports, Gooren and Bunck [ 23 ] explored whether transgender athletes have a physiological advantage in competitive sport. One study explored participation in competitive sports and sport-related physical activity [ 24 ] and another study discussed participation in sport-related physical activity only [ 30 ]. Details of all of the research articles included within this systematic review can be found in Table 1 .

Table 1

Study characteristics of research articles included within the review

Review of Transgender People and Competitive Sport Participation (Elite and Recreational): Research Articles

The same data were extracted from all research articles reviewed (Table 1 ). Below, we provide the most prominent findings in relation to competitive sport participation from each of these articles. Six research articles were concerned with competitive sport participation within this systematic review [ 23 , 25 – 29 ]. The only experimental study was by Gooren and Bunck [ 23 ] who aimed to explore whether transgender people taking cross-sex hormone treatment can fairly compete in sport. The authors measured transgender people’s muscle mass (via magnetic resonance imaging) and hormone levels (via urine and blood analyses) before and 1 year after cross-sex hormone treatment. They found that 1 year after transgender male individuals had been administered cross-sex hormone treatment, testosterone levels significantly increased and these levels were within a cisgender male range. They also found that 1 year after cross-sex hormone treatment, transgender male individuals’ muscle mass had increased and was within the same range as transgender female individuals (assigned male at birth) who had not been prescribed cross-sex hormone treatment. In relation to transgender female individuals, Gooren and Bunck found testosterone levels had significantly reduced to castration levels after 1 year of cross-sex hormone treatment. Muscle mass had also reduced after 1 year of cross-sex hormone treatment. However, muscle mass remained significantly greater than in transgender male individuals (assigned female at birth) who had not been prescribed cross-sex hormone treatment.

Therefore, Gooren and Bunck concluded that transgender male individuals are likely to be able to compete without an athletic advantage 1-year post-cross-sex hormone treatment. To a certain extent this also applies to transgender female individuals; however, there still remains a level of uncertainty owing to a large muscle mass 1-year post-cross-sex hormones. While this study was the first to explore, experimentally, whether transgender people can compete fairly, the sample size was relatively small ( n = 36). Additionally, they did not explore the role of testosterone blockers and did not directly measure the effect cross-sex hormones had on athletic performance (e.g. running time). Many, but not all, transgender female individuals are prescribed testosterone blockers to help them to reach cisgender female testosterone levels, when administration of oestrogen alone is not enough to reduce testosterone levels. This is particularly important if the person aims to undergo gender-confirming surgery, as 6 months of testosterone suppression is a requirement for such procedures. However, if a transgender woman does not wish to undergo surgery or does not wish to have their testosterone blocked to cisgender female levels (e.g. as they wish to use their penis), their testosterone levels will be above cisgender female levels. Differentiating not only between those taking cross-sex hormones and not taking cross-sex hormones, but also transgender female individuals taking testosterone blockers, may be necessary when discussing an athletic advantage.

The remaining studies considered within this section are qualitative, and although they have provided insight into the experiences of transgender people participating in competitive sport, the findings cannot be generalised. Semerjian and Cohen’s [ 27 ] narrative account provides a good overview of how diverse and individual the issues and experiences of transgender people participating in competitive sport can be. Some participants felt anxious when engaging in sport because they felt their genitals may be revealed (e.g. when changing). In contrast, one participant used sport as a safe space to escape from the harassment he received at school. It must be considered though, that participants within the study engaged in different sports and their experiences could therefore be associated with the specific sport (i.e. some sports could be more inclusive then others).

Three qualitative studies described the implications that sport policies had on the experiences of transgender people who engaged in sport [ 26 , 28 , 29 ]. Cohen and Semerjian [ 26 ] published a case study about a transgender woman (pre-gender-confirming surgery) who was playing in the women’s national ice hockey tournament, but who was eventually banned from playing in the tournament because it was felt she had an athletic advantage. She described how she felt under constant surveillance when she was playing and at times felt ambivalent about what gendered team she should play on. It was apparent that although teammates were supportive, the issues she experienced in relation to inclusion in the tournament were primarily related to constraints put in place by competitive sport policies. Similarly, the discussions held by two former New Zealand transgender female netball players in Tagg’s [ 28 ] study gave the impression that although transgender sport policies were supposedly implemented to increase the inclusivity of transgender people, this was not always the case. They discussed how policy would allow a pre-gender-confirming surgery transgender woman to compete in a male or mixed-gender netball team only and they must obey male dress codes. However, the participants in this study were former netball players and therefore their discussions may not have been based on the current state of netball in relation to transgender participation. In contrast to the previously mentioned studies, the majority of participants ( n = 12) in Travers and Deri’s [ 29 ] study discussed the positive experiences they had in relation to transgender participation in competitive sport. However, some of the transgender men did discuss how they had hostile experiences (e.g. incorrect pronoun use). Several of the participants in this study also felt that testosterone gave transgender women (endogenous) and men (when injected) an athletic advantage.

For the two young transgender male individuals in Caudwell’s [ 25 ] study, the stage of transition appeared to be instrumental in disengagement from participation in competitive sport. The discussion held by the participants highlighted how accessing sport during their transitional period was difficult as they would not be accepted or feel comfortable on either a male or female team during this period. However, this study again discussed sport very broadly and therefore it is unknown whether the participants’ experiences were associated with specific sports or whether they are generalisable across other sports.

In summary, there is limited research from which to draw any conclusion about whether transgender people have an athletic advantage in competitive sport or not. The limited physiological research conducted to date has informed the development of transgender sport policies that are implemented by sporting organisations all over the world. It is these sport policies that appear to be instrumental in transgender people’s experiences with competitive sport, most of which are negative.

Review of Transgender People and Sport-Related Physical Activities: Research Articles

Within this systematic review, only two studies explored sport-related physical activities [ 24 , 30 ]. Muchicko et al. [ 30 ] set out to quantitatively explore the relationship between gender identity and physical activity. They compared levels of physical activity between cisgender and transgender people. The study found that self-identified transgender participants ( n = 33) reported engaging in less physical activity than cisgender participants ( n = 47). Social support and self-perception were found to mediate the relationship between gender identity and physical activity. The authors suggested that their study highlights how leisure centres need to be more inclusive, and transgender people need to be given more social support to encourage physical activity. However, this study was limited by the sampling methods employed. The cisgender participants were recruited from a university campus where they potentially had more opportunity to walk around campus, and opportunity for discounted gym memberships, whereas the transgender participants were recruited from a support group for transgender people and were not associated with the university.

As with transgender people who engage in sport at a competitive level, transgender people who engage in sport-related physical activity also appear to experience a range of different barriers. Hargie et al. [ 24 ] found in their qualitative study that transgender people prefer to engage in individual, as opposed to group, sport-related physical activities. This was reportedly owing to their fear of being ‘outed’. Regardless of whether sport-related physical activities are engaged in individually or in a group, changing rooms appeared to be a significant barrier. Being excluded from sport-related physical activities was distressing for participants, as they could not maintain physical fitness, which they felt was important in preparation for gender-confirming surgery. Despite these interesting findings, the study is limited by the lack of sociodemographic information provided about participants. Within qualitative research, because of the small sample size, it is often desirable to provide a large amount of sociodemographic detail about participants so that the findings can be interpreted in relation to this information. For instance, in the context of sport-related physical activities, the stage of transition may be an important factor when interpreting the individuals’ current experiences of sport-related physical activities.

The limited research studies concerned with sport-related physical activities suggest that inclusive environments are not created for transgender people engaging in such activities, which may deter engagement.

Transgender-Inclusive Sport Policies

Characteristics of the eligible sport policies.

Of the 31 transgender inclusive policies reviewed, 13 were from the USA [ 31 – 43 ]. Ten of the policies reviewed were from the UK [ 44 – 53 ]. One policy was from Australia [ 54 ]. The rest of the policies ( n = 7) were international [ 18 , 20 , 55 – 59 ]. Details of all of the sport policies included within this review can be found in Table 2 .

Table 2

Transgender-inclusive sport policies included within this systematic review

GCS gender-confirming surgery, CHT cross-sex hormone therapy, IOC International Olympic Committee, TUE therapeutic use exemption, n.d. no date

a Gender dysphoria is the diagnostic name included within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders , Fifth Edition, for people who experience an incongruence between their gender assigned at birth and gender identity [ 60 ]

Review of the Sport Policies

Policies within this section were systematically reviewed in relation to their inclusiveness of transgender competitors (i.e. maintaining fairness in the absence of advantage for all competitors). The fairness of the policy requirements was judged against the available physiological research that has explored athletic advantage. The time restrictions associated with each requirement were also reviewed (e.g. cross-sex hormones must have been administered for at least 2 years prior to competition). The requirements from each policy are summarised within Table 2 and the most salient points of these policies are then presented in the section that follows.

In 2004, the IOC [ 18 ] announced that transgender people who transition after puberty are permitted to compete in sport in line with their experienced gender identity providing they have had gender-confirming surgery, can provide legal recognition of their gender, have been prescribed cross-sex hormone treatment for at least 2 years and have lived in their experienced gender for the same amount of time [ 18 ]. Additionally, transgender people who had undergone gender-confirming surgery pre-puberty are eligible to compete in sport in line with their experienced gender identity [ 18 ]. This is an international policy and has been adopted by sport organisations all over the world.

While the 2004 IOC [ 18 ] policy has been praised for its efforts to address the inclusion of transgender athletes [ 61 ], several flaws have been identified [ 61 ]. First, the policy excludes transgender people who choose not to have gender-confirming surgery owing to a lack of genital dysphoria (distress), medical reasons, fears about risk during operations, and/or because of other personal reasons [ 28 , 62 , 63 ]. The 2004 IOC [ 18 ] policy also excludes transgender people who are in the process of transitioning. For instance, a transgender athlete may be prescribed cross-sex hormone treatment, but be yet to undergo gender-confirming surgery. The 2004 IOC policy [ 18 ] therefore adopts a very narrow definition and excludes a large proportion of transgender people [ 19 ]. In addition to this, the policy appears to have been developed with only transgender female individuals in mind, possibly as transgender male individuals are not thought to possess athletic advantages in the majority of sports, and therefore the policy discriminates against transgender male individuals [ 21 ]. Moreover, the 2004 IOC [ 18 ] policy fails to take into consideration the regional, national and international differences in accessing cross-sex hormone treatment and gender-confirming surgery [ 18 , 63 – 65 ]. Within this policy, there also appears a lack of an evidence-based rationale as to why a period of 2 years was chosen as the length of time cross-sex hormone treatment must be administered prior to sport competition and why individual differences in blood hormone levels are not considered [ 66 ]. As mentioned previously, the role of testosterone blockers in transgender women is also not considered. Although the rationale for the 2-year time period is not made explicit, it may be related to the fact that this time period was imposed by the IOC in 2004, when banning athletes from competitive sport to discipline them for doping violations. The evidence-based rationale for gender-confirming surgery is also not clear [ 61 ]; whether an athlete has a penis or vagina appears irrelevant, as this will not change the physiology of the body or the physiological advantage of the person [ 63 ].

Approximately 200 days before the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, the IOC announced changes to their competitive sport policy for transgender people. The new 2016 IOC [ 20 ] policy suggests that transgender male athletes are able to compete in a male category without any restrictions. Transgender female athletes may compete in a female category if they have declared their gender as female for at least 4 years and their blood testosterone levels are below 10 nmol/L for at least 12 months prior to competition. However, the latter requirement is a general guideline, and each case will be reviewed individually to determine whether 12 months is a sufficient amount of time to suppress testosterone levels to an appropriate level. If transgender female athletes do not meet these requirements, they will be able to compete in a male category. This is a great improvement in sport policy, which considers gender assigned at birth and individual difference in relation to bloody hormone levels and moves away from the requirement of surgery to compete in their experienced gender category. However, we could not find any evidence to support the requirement for testosterone levels to be below 10 nmol/L for at least 12 months.

Despite its flaws, the 2004 IOC policy [ 18 ] has been adopted by several other sport organisations. Within this systematic review, 11 sport organisations adopted the policy outlined by the IOC in 2004 [ 33 , 36 , 38 – 40 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 51 , 57 ]. All but one (the International Tennis Federation) of these sport organisation policies are employed at a national level. Not only is it problematic that other sport organisations adopted the 2004 IOC policy, but elements of the 2004 IOC policy concerning children pre-puberty are not applicable to sport organisations in the UK and many other countries. Within the UK (and many other countries), children presenting with gender incongruence cannot undergo gender-confirming surgery before the age of 18 years, by which time puberty has usually started.

Three policies stated that it is only necessary to provide legal recognition of gender and to be prescribed cross-sex hormone treatment for a ‘sufficient amount of time’ (international policy) [ 56 ] or so that hormone blood levels are within cisgender female or male ranges (national policy) [ 44 , 52 ]. Policies from the National Collegiate Athletic Association [ 32 ] and British Rowing [ 50 ] also state that only cross-sex hormone treatment is required; however, the specifics of this requirement differ for both transgender male and female individuals. With both of these policies, transgender female individuals have to provide more evidence of cross-sex hormone treatment and their blood hormone levels in comparison to transgender male individuals. Similarly, the Association of Boxing Commissions [ 31 ] in its national policy has different cross-sex hormone treatment requirements depending on gender assigned at birth and how the athlete identifies themselves (transgender or transsexual). The language used within the Association of Boxing Commissions’ policy [ 31 ] may be seen as offensive by some transgender people and the difference between “transsexuals” and “transgender” people remains unclear. Policies held by the Ladies Professional Golf Association (international policy) [ 43 ] and the International Association of Athletics Federations [ 55 ] differ dramatically in relation to gender and gender-confirming surgery as a requirement. In both cases, it is necessary for transgender female individuals to have undergone this procedure, but not for transgender male individuals. Although some of the requirements of these policies are unreasonable and not evidence based (e.g. gender-confirming surgery), the gender difference in relation to the amount of evidence that is required about their gender change seems acceptable considering that only transgender female individuals (and not transgender male individuals) are currently seen to potentially have an athletic advantage [ 23 ].

The more inclusive sport policies reviewed here only required legal or medical recognition or do not ask for any evidence of gender; thus they encourage competition in line with the experienced gender (five were national policies and two were international) [ 34 , 35 , 41 , 42 , 53 , 54 , 59 ]. The Fédération Internationale de Volleyball [ 58 ] had the most invasive policy considered within this systematic review; they ask players to provide a birth certificate to verify gender. Additionally, female players may be asked to provide a gender certificate or submit themselves to a medical examination if the medical evidence is not sufficient. Both British Universities & Colleges Sport [ 47 ] and USA Triathlon [ 37 ] do not have their own policies, but suggest the adoption of other policies (i.e. those relevant to the sport in question or guidelines of the US Anti-Doping Agency, respectively).

Currently, the majority of sport policies unfairly exclude transgender people from competitive sport, as the requirements they place on them are not underpinned by evidence-based medicine. Until (and if) there is consistent and direct evidence to demonstrate transgender people have an athletic advantage, it seems unreasonable to exclude them on any basis.

The first aim of this systematic review was to explore the experiences of transgender people in relation to competitive sport participation (elite and recreational) and sport-related physical activity. The majority of the studies within this body of literature are qualitative in nature, which may be at least partly a reflection of the low numbers of transgender people in the general population. It is therefore difficult to draw any definite conclusions because of the lack of quantitative research. By its very nature, the findings from qualitative research cannot be generalised but the findings can be used to form a platform from which generalisations can be made. The research articles reviewed here described a generally negative experience of sport participation and sport-related physical activity for transgender individuals. It was evident from these studies that transgender people are facing barriers when engaging in competitive sport and sport-related physical activity. In relation to sport-related physical activity, lack of accessibility to an inclusive and comfortable environment appeared to be the primary barrier to participation. Charities and support organisations working with transgender people should consider developing campaigns to raise awareness about different gender identities. Leisure centres should also be made more aware of potential gender differences (i.e. via training and greater information provision) and be given advice on how to make such environments more inclusive of transgender people (e.g. gender neutral changing facilities with cubicles). In relation to competitive sport participation, the findings from this systematic review suggest that the requirements that transgender competitive sport policies place on competitors were instrumental in transgender athletes’ negative experiences.

While a distinction needs to be made between the issues and experiences transgender people have with regard to participation in sport and competitive sport, it also needs to be acknowledged that there is an overlap. Transgender male and female individuals have anecdotally discussed that access to sport participation (such as becoming part of the local football team) is restricted as even community and local sport organisations who play at a recreational level implement transgender competitive sport policies.

The second aim was to review the available sport policies regarding the fairness for transgender people in competitive sport (i.e. fairness in the absence of advantage). Owing to overinterpretation and fear of the athletic advantage in transgender athletes, the majority of the policies reviewed were discriminatory against transgender people, especially transgender male individuals (i.e. exclusion in the absence of advantage). Although the updated IOC policy may be perceived as more inclusive then the 2004 version, there are still flaws. The requirement for a transgender female individual to have declared their gender as female for at least 4 years is excessive. In the UK and many other countries, once a transgender person has accessed a transgender health service, it is likely to be less than 4 years before a person legally changes their name, undergoes irreversible treatments and, hence, fully commits to their experienced gender. There appears to be a lack of rationale regarding the 4-year time period for transgender athletes, although this time restriction is consistent with the current disciplinary action for cisgender athletes when a doping incident occurs [ 67 ]. The 2016 IOC policy [ 20 ] also states that to avoid discrimination against transgender female individuals, they are allowed to complete in a male category if they do not meet the requirements for transgender female athletes. For most transgender female individuals, competing in a male category, when their experienced gender is female, would be distressing and may deter engagement in competitive sport altogether. This particular requirement may be promoting exclusion of transgender female individuals in competitive sport, rather than avoiding discrimination.

Several sport policies, including the recently updated IOC 2016 [ 20 ] policy, have based their requirements for transgender competitors on indirect, inconsistent and unambiguous evidence. Physiological research involving cisgender people has shown that testosterone deficiency in young men is associated with a decrease in muscle strength [ 68 ] and testosterone injections in cisgender men are associated with an increase in some aspects of muscle strength [ 69 ]. However, this research did not determine whether these decreases and increases in muscle mass are within ranges for cisgender female and male individuals and the time required to reach cisgender male or female levels. Elbers et al. [ 70 ] expanded on this research by exploring the effects of oestrogen supplements and androgen deprivation on fat distribution and thigh muscle mass (by using magnetic resonance imaging) in 20 transgender female individuals. They found that 12 months after cross-sex hormone treatment, transgender female individuals had a more feminine pattern of adiposity and their thigh muscles had decreased. Other research has found that transgender female athletes who have hormonally and surgically transitioned have reported feeling weaker and their testosterone levels tend to be lower than average compared with cisgender women [ 19 , 71 ]. However, this research does not tell us anything about the relationship between androgenic hormones and athletic ability.

To date, Harper’s study [ 72 ] is the only one to directly explore androgenic hormones and athletic ability. The aim of the study was to explore the long-distance (5–42 km) running times of eight transgender female individuals pre- and post-testosterone suppression. It was found that post-testosterone suppression running times were significantly slower in comparison to pre-testosterone suppression. Harper stated that owing to reductions in testosterone and haemoglobin, transgender female individuals post-transition would have the same endurance capabilities as a cisgender female individual. However, the sample size was very small ( n = 8) and participants were asked to self-report their race times, which might have been subject to recall or social desirability bias.

On average, men perform better than women in sport; however, no empirical research has identified the specific reason(s) why. Based mainly on indirect research with cisgender people, it is commonly believed that androgenic hormones (specifically high testosterone levels) confer an advantage in competitive sports (i.e. enhance endurance, increase muscle mass) and, while this belief has informed several sporting policies, testosterone may not be the primary, or even a helpful, marker in determining athletic advantage [ 73 ]. Karkazis et al. [ 73 ] have argued that there is no evidence to suggest that endogenous testosterone levels are predictive of athletic performance (apart from doping), as there is variation in how bodies make and respond to the hormone. Testosterone is only one part of a person’s physiology and there are other important factors (both biological and environmental) that should be considered if fairness (the absence of advantage) is the aim in competitive sport. For instance, having large hands is key for manipulation in some sports (e.g. basketball), but this is not seen as an unfair advantage. Establishing what an athletic advantage is in competitive sport would facilitate inclusion of all athletes (regardless of their gender identity) on the premise of fairness.