- Homework Help

- Essay Examples

- Citation Generator

Writing Guides

- Essay Title Generator

- Essay Topic Generator

- Essay Outline Generator

- Flashcard Generator

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Introduction Generator

- Literature Review Generator

- Hypothesis Generator

Writing Guides / 15 Abstract Examples: A Comprehensive Guide

15 Abstract Examples: A Comprehensive Guide

Demystifying Abstract Writing

An abstract represents a concise, well-articulated summary of an academic piece or research. But writing an abstract goes beyond merely creating a summary. In this piece, we’ll delve into examples of abstracts to illuminate what they truly are, along with the necessary tone, style, and word counts.

You’ll also see how diverse abstract writing can be, tailored according to the subject area. For instance, an abstract for empirical research in the sciences contrasts greatly from that of a humanities article.

View 120,000+ High Quality Essay Examples

Learn-by-example to improve your academic writing

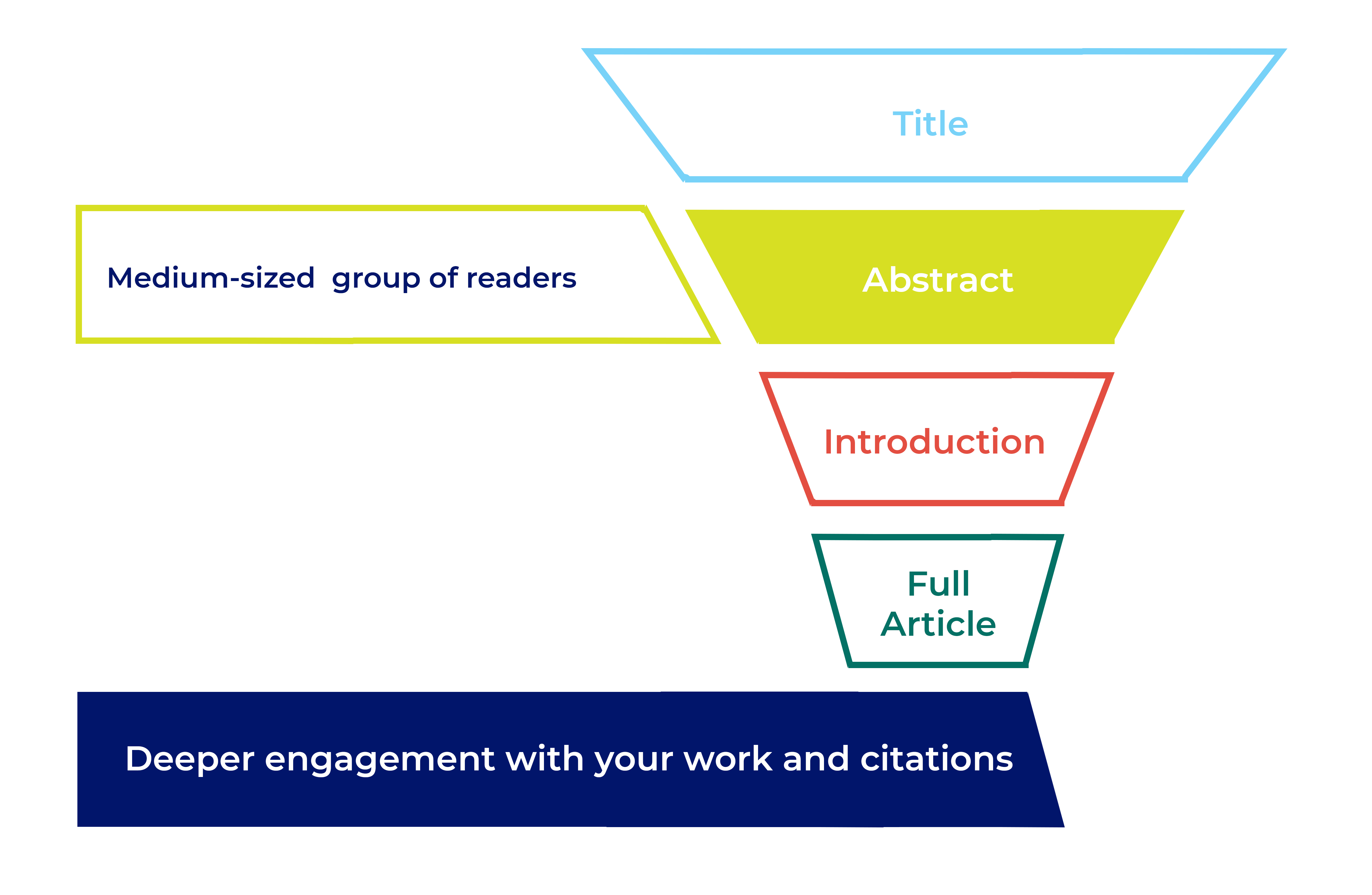

The Importance of Abstracts: Why Do We Write Them?

Every abstract you encounter, including our abstract writing example, has a few core characteristics. The primary role of an abstract is to encapsulate the essential points of a research article, much like a book’s back cover. The back jacket often influences whether you buy the book or not.

Similarly, academic papers are often behind paywalls, and the abstract assists readers in deciding if they should purchase the article. If you’re a student or researcher, the abstract helps you gauge whether the article is worth your time.

Furthermore, abstracts promote ongoing research in your field by incorporating keywords that allow others to locate your work. Knowing how to write a good abstract contributes to your professionalism, especially crucial for graduate-level studies. This skill might be vital when submitting your research to peer-reviewed journals or soliciting grant funding.

Breaking Down an Abstract: What’s Inside?

The contents of an abstract heavily rely on the type of study, research design, and subject area. An abstract may contain a succinct background statement highlighting the research’s significance, a problem statement, the methodologies used, a synopsis of the results, and the conclusions drawn.

When it comes to writing an abstract for a research paper, striking a balance between consciousness and informative detail is essential. Our examples of abstracts will help you grasp this balance better.

Moreover, you’ll learn how to format abstracts variably, matching the requirements of your degree program or publication guidelines.

Key Elements to Include in Your Abstract

- Brief Background: Introduce the importance of the research from your point of view.

- Problem Statement: Define the issue your research addresses, commonly referred to as the thesis statement.

- Methodology: Describe the research methods you employed.

- Synopsis: This should include a summary of your results and conclusions.

- Keywords: Implement terms that others will use to find your article.

Types of Abstracts

- Descriptive Abstracts: These give an overview of the source material without delving into results and conclusions.

- Informative Abstracts: These offer a more detailed look into your research, including the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Always write your abstract in the present tense.

- Keep track of word counts to maintain brevity.

- The original text should guide your abstract.

- Always provide a good synopsis in your abstract.

- If needed, use your abstract to draft a compelling query letter.

- Consider providing a literature review abstract if your research involves an extensive review of existing literature.

Types of Abstract

According to the Purdue Online Writing Lab resource, there are two different types of abstract: informational and descriptive.

Although informative and descriptive abstracts seem similar, they are different in a few key ways.

An informative abstract contains all the information related to the research, including the results and the conclusion.

A descriptive abstract is typically much shorter, and does not provide as much information. Rather, the descriptive abstract just tells the reader what the research or the article is about and not much more.

The descriptive abstract is more of a tagline or a teaser, whereas the informative abstract is more like a summary.

You will find both types of abstracts in the examples below.

Abstract Examples

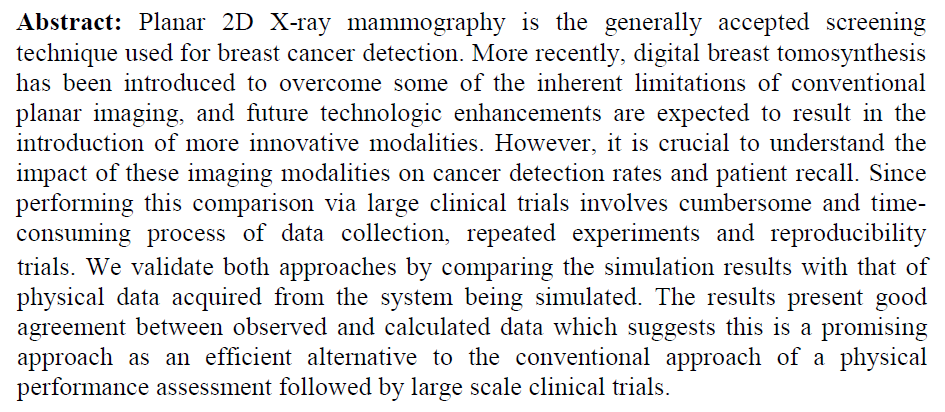

Informative abstract example 1.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) has been correlated with leadership effectiveness in organizations. Using a mixed-methods approach, this study assesses the importance of emotional intelligence on academic performance at the high school level.

The Emotional Intelligence rating scale was used, as well as semi-structured interviews with teachers. Participant grades were collected. Emotional intelligence was found to correlate positively with academic success. Implications for pedagogical practice are discussed.

Explanation

This is a typical informative abstract for empirical social sciences research. Most informative abstracts proceed in a logical fashion to reflect the organization of the main paper: with sections on the background, methods, results, and conclusions.

Informative Abstract Example 2

Social learning takes place through observations of others within a community. In diverse urban landscapes and through digital media, social learning may be qualitatively different from the social learning that takes place within families and tightly-knit social circles.

This study examines the differences between social learning that takes place in the home versus social learning that takes place from watching celebrities and other role models online. Results show that social learning takes place with equal efficacy. These results show that social learning does not just take place within known social circles, and that observations of others can lead to multiple types of learning.

This is a typical informative abstract for empirical social science research. After the background statement, the author discusses the problem statement or research question, followed by the results and the conclusions.

Informative Abstract Example 3

Few studies have examined the connection between visual imagery and emotional reactions to news media consumption. This study addresses the gap in the literature via the use of content analysis. Content analysis methods were used to analyze five news media television sites over the course of six months.

Using the Yolanda Metrics method, the researchers ascertained ten main words that were used throughout each of the news media sites. Implications and suggestions for future research are included.

This abstract provides an informative synopsis of a quantitative study on content analysis. The author provides the background information, addresses the methods, and also outlines the conclusions of the research.

Informative Abstract Example 4

This study explores the relationship between nurse educator theoretical viewpoints and nursing outcomes. Using a qualitative descriptive study, the researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with nursing students and nurse educators. The results show that nurse educator theoretical viewpoints had a direct bearing on nurse self-concept. Nurse educators should be cognizant of their biases and theoretical viewpoints when instructing students.

This example showcases how to write an abstract for a qualitative study. Qualitative studies also have clearly defined research methods. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind the general principles of informative abstract writing. Always begin with the research question or problem statement, and proceed to offer a one-sentence description of study methods and results.

Informative Abstract Example 5

Aboriginal people have poorer health outcomes versus their counterparts from other ethnic groups. In this study, public health researchers conducted an epidemiological data analysis using results from the Transcultural Health Report. Using a chi-square test, the researchers found that there is a direct correlation between ethnicity and health status. Policymakers should consider introducing methods for reducing health disparities among minority groups.

This informative abstract details the methods used in the report. As with other informative abstracts, it is written in the past tense. The abstract provides the reader with a summary of the research that has already been conducted.

Informative Abstract Example 6

We examine the contradictions of decolonization as official state policy. Using themes related to decolonization from the literature, we discuss how oppressed people develop cogent policies that create new systems of power. Intersectionality is also discussed.

Through a historical analysis, it was found that decolonization and political identity construction take place not as reactionary pathways but as deliberate means of regaining access to power and privilege. The cultivation of new political and social identities promotes social cohesion in formerly colonized nation-states, paving the way for future means of identity construction.

This abstract is informative but because it does not involve a unique empirical research design, it is written in a different manner from other informative abstracts. The researchers use tone, style, and diction that parallels that which takes place within the body of the text. The main themes are elucidated.

Informative Abstract Example 7

The implementation of a nationwide mandatory vaccination program against influenza in the country of Maconda was designed to lower rates of preventable illnesses. This study was designed to measure the cost-effectiveness of the mandatory vaccination program.

This is a cohort study designed to assess the rates of new influenza cases among both children (age > 8 years) and adults (age > 18 years). Using the National Reference Data Report of Maconda, the researchers compiled new case data (n = 2034) from 2014 to 2018.

A total of 45 new cases were reported during the years of 2014 and 2015, and after that, the number of new cases dropped by 74%.

The significant decrease in new influenza cases can be attributed to the introduction of mandatory vaccination.

Interpretation

The mandatory vaccination program proves cost-effective given its efficacy in controlling the disease.

This method of writing an informative abstract divides the content into respective subject headers. This style makes the abstract easier for some readers to scan quickly.

Informative Abstract Example 8

Mindfulness-based meditation and mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques have been shown to reduce burnout and improve employee engagement. Using a pretest/posttest design, the researchers randomly assigned nurses (n = 136) to the control and experimental groups. The Kabat-Zinn mindfulness-based stress reduction technique was used as the primary intervention for the experimental group.

Quantitative findings revealed significant improvements on self-report scales for depression and anxiety. Nurse leaders and administrators should consider implementing a mindfulness-based stress reduction program to reduce burnout and improve overall nurse performance.

This abstract contains all the necessary information you would need to make an assessment of whether the research was pertinent to your study. When you are writing an informative abstract, consider taking one sentence from each of the sections in your research (introduction/background, methods, results, and conclusion).

Descriptive Abstract Example 1

What inspires individuals to become members of a new religious movement, or a “cult”? This review of the literature offers some suggestions as to the psychological and sociological motivations for joining a new religious movement, offering suggestions for future research.

Unlike informative abstracts, descriptive abstracts simply alert the reader of the main gist of the article. Reading this abstract does not tell you exactly what the researchers found out about their subject, but it does let the reader know what the overall subject matter was and the methods used to conduct the research.

Descriptive Abstract Example 2

With few remaining survivors of the Holocaust, it becomes critical for historians to gather as much data that can contribute to an overall understanding of the ways trauma has been incorporated into identity. Interviews with five Holocaust survivors reveal new information about the role that art and music played in self-healing and community healing.

This descriptive abstract does not give too much information away, simply telling the reader that the researcher used interviews and a case study research design. Although it is a brief description of the study, the researchers succinctly summarize the contents and results.

Descriptive Abstract Example 3

Absurdist theater and literature have had a strong influence on playwrights in France and England. This analysis of absurdist theater addresses the primary symbols being used in absurdist literature and traces the evolution of those symbols as they parallel historical events.

As with most descriptive abstracts, this example is short. You can use descriptive abstracts to provide the reader with a summary of non-empirical research such as literary criticism.

Descriptive Abstract Example 4

The architecture of Oscar Niemeyer reflects socialist sensibilities in the urban planning of Brasilia. This research explores the philosophical underpinnings of Niemeyer’s design through an analysis of several of the main elements of the National Congress of Brazil. Implications and influences of Niemeyer’s work are also discussed.

Note how with the descriptive abstract, you are writing about the research in a more abstract and detached way than when you write an informative abstract.

Descriptive Abstract Example 5

Jacques Derrida has written extensively on the symbolism and the metonymy of September 11. In this research, we critique Derrida’s position, on the grounds that terrorism is better understood from within a neo-realist framework. Derrida’s analysis lacks coherence, is pompous and verbose, and is unnecessarily abstract when considering the need for a cogent counterterrorism strategy.

Like most descriptive abstracts, this encapsulates the main idea of the research but does not necessarily follow the same format as you might use in an informative abstract. Whereas an informative abstract follows the chronological format used in the paper you present, with introduction, methods, findings, and conclusion, a descriptive abstract only focuses on the main idea.

Descriptive Abstract Example 6

The Five Factor model of personality has been well established in the literature and is one of the most reliable and valid methods of assessing success. In this study, we use the Five Factor model to show when the qualities of neuroticism and introversion, which have been typically linked with low rates of success, are actually correlated with achievement in certain job sectors. Implications and suggestions for clinicians are discussed.

This descriptive abstract does not discuss the methodology used in the research, which is what differentiates it from an informative abstract. However, the description does include the basic elements contained in the report.

Descriptive Abstract Example 7

This is a case study of a medium-sized company, analyzing the competencies required for entering into the Indian retail market. Focusing on Mumbai and Bangalore, the expansion into these markets reveals potential challenges for European firms. A comparison case with a failed expansion into Wuhan, China is given, offering an explanation for how there are no global cross-cultural competencies that can be applied in all cases.

While this descriptive abstract shows the reader what the paper addresses, the methods and results are omitted. A descriptive abstract is shorter than an informative abstract.

Which Type of Abstract Should I Use?

Check with your professors or academic advisors, or with the editor of the peer-reviewed journal before determining which type of abstract is right for you.

If you have conducted original empirical research in the social sciences, you will most likely want to use an informative abstract.

However, when you are writing about the arts or humanities, a descriptive abstract might work best.

What Information Should I Include in An Abstract?

The information you include in the abstract will depend on the substantive content of your report.

Consider breaking down your abstract into five separate components, corresponding roughly with the structure of your original research.

You can write one or two sentences on each of these sections:

For Original Empirical Research

1. Background/Introductory Sentence

If you have conducted, or are going to conduct, an original research, then consider the following elements for your abstract:

What was your hypothesis?

What has the previous literature said about your subject?

What was the gap in the literature you are filling with your research?

What are the research questions?

What problem are you trying to solve?

What theoretical viewpoint or approach did you take?

What was your research design (qualitative, quantitative, multi-factorial, mixed-methods)?

What was the setting? Did you conduct a clinical analysis? Or did you conduct a systematic review of literature or a meta-analysis of data?

How many subjects were there?

How did you collect data?

How did you analyze the data?

What methodological weaknesses need to be mentioned?

III. Results

If this was a qualitative study, what were the major findings?

If this was a quantitative study, what were the major findings? Was there an alpha coefficient? What was the standard deviation?

Were the results statistically significant?

1. Discussion

Did the results prove or disprove the hypothesis ?

Were the results significant enough to inform future research?

How do your results link up with previous research? Does your research confirm or go beyond prior literature?

1. Conclusions/Recommendations

What do your results say about the research question or problem statement?

If you had to make a policy recommendation or offer suggestions to other scholars, what would you say?

Are there any concluding thoughts or overarching impressions?

Writing Abstracts for Literary Criticism and Humanities Research

Writing abstracts for research that is not empirical in nature does not involve the same steps as you might use when composing an abstract for the sciences or social sciences.

When writing an abstract for the arts and humanities, consider the following outline, writing one or two sentences for each section:

1. Background/Introduction

What other scholars have said before.

Why you agree or disagree.

Why this is important to study.

1. Your methods or approach

How did you conduct your research?

Did you analyze a specific text, case study, or work of art?

Are you comparing and contrasting?

What philosophical or theoretical model did you use?

III. Findings

What did you discover in the course of your research?

1. Discussion/Conclusion

How are your findings meaningful?

What new discoveries have you made?

How does your work contribute to the discourse?

General Tips for Writing Abstracts

The best way to improve your abstract writing skills is to read more abstracts. When you read other abstracts, you will understand more about what is expected, and what you should include or leave out from the abstract.

Reading abstracts helps you become more familiar with the tone and style, as well as the structure of abstracts.

Write your abstract after you have completed your research.

Many successful abstracts actually take the first sentence from each section of your research, such as the introduction/background, review of literature, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion.

Although it is a good idea to write the results of your original research, avoid giving too much detail. Instead, focus on what really matters.

A good abstract is like an elevator pitch.

While there is no absolute rule for how long an abstract should be, a general rule of thumb is around 100-150 words. However, some descriptive abstracts may be shorter than that, and some informative abstracts could be longer.

How to Write a Synopsis

Writing a synopsis involves summarizing a work’s key elements, including the narrative arc, major plot points, character development, rising action, and plot twists. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to create a compelling synopsis.

- Outline the Narrative Arc: Start by defining your story’s beginning, middle, and end. This includes the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

- Identify Major Plot Points: Major plot points are crucial events that propel your story forward. Identify these critical moments and explain how they contribute to the narrative arc.

- Discuss Character Development: Characters are the backbone of your story. Describe your characters at the start of the story and demonstrate how they evolve by the end.

- Illustrate Rising Action: The rising action is a series of events that lead to the climax of your story. Ensure to discuss these events and how they build suspense and momentum.

- Include Plot Twists: If your story has unexpected turns or surprises, highlight these plot twists in your synopsis. However, ensure these twists aren’t revealed too abruptly.

Remember, a synopsis should provide a complete overview of your story. It’s different from a teaser or back cover blurb — your objective isn’t to create suspense, but to succinctly present the whole narrative.

How Long Should a Summary Be

The length of a summary varies based on the complexity and length of the original work. However, as a rule of thumb, a summary should ideally be no more than 10-15% of the original text’s word count. This ensures you cover the significant plot points, character development, narrative arc, rising action, and plot twists without going into excessive detail.

For instance, if you’re summarizing a 300-page novel, your summary may be about 30 pages. If you’re summarizing a short 5-page article, a half-page to one-page summary should suffice.

Remember, the goal of a summary is to condense the source material, maintaining the core ideas and crucial information while trimming unnecessary details. Always aim for brevity and clarity in your summaries.

Abstracts are even shorter versions of executive summaries. Although abstracts are brief and seem relatively easy, they can be challenging to write. If you are struggling to write your abstract, just consider the main ideas of your original research paper and pretend that you are summarizing that research for a friend.

If you would like more examples of strong abstracts in your field of research, or need help composing your abstract or conducting research, call a writing tutor.

“Abstracts,” (n.d.). The Writing Center. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/abstracts/

Koopman, P. (1997). How to write an abstract. https://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/essays/abstract.html

University of Massachusetts, Amherst (n.d.). Writing an abstract.

“Writing Report Abstracts,” (n.d.). Purdue Online Writing Lab. https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/656/1/

Take the first step to becoming a better academic writer.

Writing tools.

- How to write a research proposal 2021 guide

- Guide to citing in MLA

- Guide to citing in APA format

- Chicago style citation guide

- Harvard referencing and citing guide

- How to complete an informative essay outline

How to Write a Synthesis Essay: Tips and Techniques

Why Using Chat-GPT for Writing Your College Essays is Not Smart

The Importance of an Outline in Writing a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

A Guide to Choosing the Perfect Compare and Contrast Essay Topic

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write an Abstract (With Examples)

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is an abstract in a paper, how long should an abstract be, 5 steps for writing an abstract, examples of an abstract, how prowritingaid can help you write an abstract.

If you are writing a scientific research paper or a book proposal, you need to know how to write an abstract, which summarizes the contents of the paper or book.

When researchers are looking for peer-reviewed papers to use in their studies, the first place they will check is the abstract to see if it applies to their work. Therefore, your abstract is one of the most important parts of your entire paper.

In this article, we’ll explain what an abstract is, what it should include, and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of the details within a report. Some abstracts give more details than others, but the main things you’ll be talking about are why you conducted the research, what you did, and what the results show.

When a reader is deciding whether to read your paper completely, they will first look at the abstract. You need to be concise in your abstract and give the reader the most important information so they can determine if they want to read the whole paper.

Remember that an abstract is the last thing you’ll want to write for the research paper because it directly references parts of the report. If you haven’t written the report, you won’t know what to include in your abstract.

If you are writing a paper for a journal or an assignment, the publication or academic institution might have specific formatting rules for how long your abstract should be. However, if they don’t, most abstracts are between 150 and 300 words long.

A short word count means your writing has to be precise and without filler words or phrases. Once you’ve written a first draft, you can always use an editing tool, such as ProWritingAid, to identify areas where you can reduce words and increase readability.

If your abstract is over the word limit, and you’ve edited it but still can’t figure out how to reduce it further, your abstract might include some things that aren’t needed. Here’s a list of three elements you can remove from your abstract:

Discussion : You don’t need to go into detail about the findings of your research because your reader will find your discussion within the paper.

Definition of terms : Your readers are interested the field you are writing about, so they are likely to understand the terms you are using. If not, they can always look them up. Your readers do not expect you to give a definition of terms in your abstract.

References and citations : You can mention there have been studies that support or have inspired your research, but you do not need to give details as the reader will find them in your bibliography.

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

If you’ve never written an abstract before, and you’re wondering how to write an abstract, we’ve got some steps for you to follow. It’s best to start with planning your abstract, so we’ve outlined the details you need to include in your plan before you write.

Remember to consider your audience when you’re planning and writing your abstract. They are likely to skim read your abstract, so you want to be sure your abstract delivers all the information they’re expecting to see at key points.

1. What Should an Abstract Include?

Abstracts have a lot of information to cover in a short number of words, so it’s important to know what to include. There are three elements that need to be present in your abstract:

Your context is the background for where your research sits within your field of study. You should briefly mention any previous scientific papers or experiments that have led to your hypothesis and how research develops in those studies.

Your hypothesis is your prediction of what your study will show. As you are writing your abstract after you have conducted your research, you should still include your hypothesis in your abstract because it shows the motivation for your paper.

Throughout your abstract, you also need to include keywords and phrases that will help researchers to find your article in the databases they’re searching. Make sure the keywords are specific to your field of study and the subject you’re reporting on, otherwise your article might not reach the relevant audience.

2. Can You Use First Person in an Abstract?

You might think that first person is too informal for a research paper, but it’s not. Historically, writers of academic reports avoided writing in first person to uphold the formality standards of the time. However, first person is more accepted in research papers in modern times.

If you’re still unsure whether to write in first person for your abstract, refer to any style guide rules imposed by the journal you’re writing for or your teachers if you are writing an assignment.

3. Abstract Structure

Some scientific journals have strict rules on how to structure an abstract, so it’s best to check those first. If you don’t have any style rules to follow, try using the IMRaD structure, which stands for Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion.

Following the IMRaD structure, start with an introduction. The amount of background information you should include depends on your specific research area. Adding a broad overview gives you less room to include other details. Remember to include your hypothesis in this section.

The next part of your abstract should cover your methodology. Try to include the following details if they apply to your study:

What type of research was conducted?

How were the test subjects sampled?

What were the sample sizes?

What was done to each group?

How long was the experiment?

How was data recorded and interpreted?

Following the methodology, include a sentence or two about the results, which is where your reader will determine if your research supports or contradicts their own investigations.

The results are also where most people will want to find out what your outcomes were, even if they are just mildly interested in your research area. You should be specific about all the details but as concise as possible.

The last few sentences are your conclusion. It needs to explain how your findings affect the context and whether your hypothesis was correct. Include the primary take-home message, additional findings of importance, and perspective. Also explain whether there is scope for further research into the subject of your report.

Your conclusion should be honest and give the reader the ultimate message that your research shows. Readers trust the conclusion, so make sure you’re not fabricating the results of your research. Some readers won’t read your entire paper, but this section will tell them if it’s worth them referencing it in their own study.

4. How to Start an Abstract

The first line of your abstract should give your reader the context of your report by providing background information. You can use this sentence to imply the motivation for your research.

You don’t need to use a hook phrase or device in your first sentence to grab the reader’s attention. Your reader will look to establish relevance quickly, so readability and clarity are more important than trying to persuade the reader to read on.

5. How to Format an Abstract

Most abstracts use the same formatting rules, which help the reader identify the abstract so they know where to look for it.

Here’s a list of formatting guidelines for writing an abstract:

Stick to one paragraph

Use block formatting with no indentation at the beginning

Put your abstract straight after the title and acknowledgements pages

Use present or past tense, not future tense

There are two primary types of abstract you could write for your paper—descriptive and informative.

An informative abstract is the most common, and they follow the structure mentioned previously. They are longer than descriptive abstracts because they cover more details.

Descriptive abstracts differ from informative abstracts, as they don’t include as much discussion or detail. The word count for a descriptive abstract is between 50 and 150 words.

Here is an example of an informative abstract:

A growing trend exists for authors to employ a more informal writing style that uses “we” in academic writing to acknowledge one’s stance and engagement. However, few studies have compared the ways in which the first-person pronoun “we” is used in the abstracts and conclusions of empirical papers. To address this lacuna in the literature, this study conducted a systematic corpus analysis of the use of “we” in the abstracts and conclusions of 400 articles collected from eight leading electrical and electronic (EE) engineering journals. The abstracts and conclusions were extracted to form two subcorpora, and an integrated framework was applied to analyze and seek to explain how we-clusters and we-collocations were employed. Results revealed whether authors’ use of first-person pronouns partially depends on a journal policy. The trend of using “we” showed that a yearly increase occurred in the frequency of “we” in EE journal papers, as well as the existence of three “we-use” types in the article conclusions and abstracts: exclusive, inclusive, and ambiguous. Other possible “we-use” alternatives such as “I” and other personal pronouns were used very rarely—if at all—in either section. These findings also suggest that the present tense was used more in article abstracts, but the present perfect tense was the most preferred tense in article conclusions. Both research and pedagogical implications are proffered and critically discussed.

Wang, S., Tseng, W.-T., & Johanson, R. (2021). To We or Not to We: Corpus-Based Research on First-Person Pronoun Use in Abstracts and Conclusions. SAGE Open, 11(2).

Here is an example of a descriptive abstract:

From the 1850s to the present, considerable criminological attention has focused on the development of theoretically-significant systems for classifying crime. This article reviews and attempts to evaluate a number of these efforts, and we conclude that further work on this basic task is needed. The latter part of the article explicates a conceptual foundation for a crime pattern classification system, and offers a preliminary taxonomy of crime.

Farr, K. A., & Gibbons, D. C. (1990). Observations on the Development of Crime Categories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(3), 223–237.

If you want to ensure your abstract is grammatically correct and easy to read, you can use ProWritingAid to edit it. The software integrates with Microsoft Word, Google Docs, and most web browsers, so you can make the most of it wherever you’re writing your paper.

Before you edit with ProWritingAid, make sure the suggestions you are seeing are relevant for your document by changing the document type to “Abstract” within the Academic writing style section.

You can use the Readability report to check your abstract for places to improve the clarity of your writing. Some suggestions might show you where to remove words, which is great if you’re over your word count.

We hope the five steps and examples we’ve provided help you write a great abstract for your research paper.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![abstract examples for essays “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![abstract examples for essays “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![abstract examples for essays “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Abstract Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide With Tips & Examples

Table of Contents

Introduction

Abstracts of research papers have always played an essential role in describing your research concisely and clearly to researchers and editors of journals, enticing them to continue reading. However, with the widespread availability of scientific databases, the need to write a convincing abstract is more crucial now than during the time of paper-bound manuscripts.

Abstracts serve to "sell" your research and can be compared with your "executive outline" of a resume or, rather, a formal summary of the critical aspects of your work. Also, it can be the "gist" of your study. Since most educational research is done online, it's a sign that you have a shorter time for impressing your readers, and have more competition from other abstracts that are available to be read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) articulates 12 issues or points considered during the final approval process for conferences & journals and emphasises the importance of writing an abstract that checks all these boxes (12 points). Since it's the only opportunity you have to captivate your readers, you must invest time and effort in creating an abstract that accurately reflects the critical points of your research.

With that in mind, let’s head over to understand and discover the core concept and guidelines to create a substantial abstract. Also, learn how to organise the ideas or plots into an effective abstract that will be awe-inspiring to the readers you want to reach.

What is Abstract? Definition and Overview

The word "Abstract' is derived from Latin abstractus meaning "drawn off." This etymological meaning also applies to art movements as well as music, like abstract expressionism. In this context, it refers to the revealing of the artist's intention.

Based on this, you can determine the meaning of an abstract: A condensed research summary. It must be self-contained and independent of the body of the research. However, it should outline the subject, the strategies used to study the problem, and the methods implemented to attain the outcomes. The specific elements of the study differ based on the area of study; however, together, it must be a succinct summary of the entire research paper.

Abstracts are typically written at the end of the paper, even though it serves as a prologue. In general, the abstract must be in a position to:

- Describe the paper.

- Identify the problem or the issue at hand.

- Explain to the reader the research process, the results you came up with, and what conclusion you've reached using these results.

- Include keywords to guide your strategy and the content.

Furthermore, the abstract you submit should not reflect upon any of the following elements:

- Examine, analyse or defend the paper or your opinion.

- What you want to study, achieve or discover.

- Be redundant or irrelevant.

After reading an abstract, your audience should understand the reason - what the research was about in the first place, what the study has revealed and how it can be utilised or can be used to benefit others. You can understand the importance of abstract by knowing the fact that the abstract is the most frequently read portion of any research paper. In simpler terms, it should contain all the main points of the research paper.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

Abstracts are typically an essential requirement for research papers; however, it's not an obligation to preserve traditional reasons without any purpose. Abstracts allow readers to scan the text to determine whether it is relevant to their research or studies. The abstract allows other researchers to decide if your research paper can provide them with some additional information. A good abstract paves the interest of the audience to pore through your entire paper to find the content or context they're searching for.

Abstract writing is essential for indexing, as well. The Digital Repository of academic papers makes use of abstracts to index the entire content of academic research papers. Like meta descriptions in the regular Google outcomes, abstracts must include keywords that help researchers locate what they seek.

Types of Abstract

Informative and Descriptive are two kinds of abstracts often used in scientific writing.

A descriptive abstract gives readers an outline of the author's main points in their study. The reader can determine if they want to stick to the research work, based on their interest in the topic. An abstract that is descriptive is similar to the contents table of books, however, the format of an abstract depicts complete sentences encapsulated in one paragraph. It is unfortunate that the abstract can't be used as a substitute for reading a piece of writing because it's just an overview, which omits readers from getting an entire view. Also, it cannot be a way to fill in the gaps the reader may have after reading this kind of abstract since it does not contain crucial information needed to evaluate the article.

To conclude, a descriptive abstract is:

- A simple summary of the task, just summarises the work, but some researchers think it is much more of an outline

- Typically, the length is approximately 100 words. It is too short when compared to an informative abstract.

- A brief explanation but doesn't provide the reader with the complete information they need;

- An overview that omits conclusions and results

An informative abstract is a comprehensive outline of the research. There are times when people rely on the abstract as an information source. And the reason is why it is crucial to provide entire data of particular research. A well-written, informative abstract could be a good substitute for the remainder of the paper on its own.

A well-written abstract typically follows a particular style. The author begins by providing the identifying information, backed by citations and other identifiers of the papers. Then, the major elements are summarised to make the reader aware of the study. It is followed by the methodology and all-important findings from the study. The conclusion then presents study results and ends the abstract with a comprehensive summary.

In a nutshell, an informative abstract:

- Has a length that can vary, based on the subject, but is not longer than 300 words.

- Contains all the content-like methods and intentions

- Offers evidence and possible recommendations.

Informative Abstracts are more frequent than descriptive abstracts because of their extensive content and linkage to the topic specifically. You should select different types of abstracts to papers based on their length: informative abstracts for extended and more complex abstracts and descriptive ones for simpler and shorter research papers.

What are the Characteristics of a Good Abstract?

- A good abstract clearly defines the goals and purposes of the study.

- It should clearly describe the research methodology with a primary focus on data gathering, processing, and subsequent analysis.

- A good abstract should provide specific research findings.

- It presents the principal conclusions of the systematic study.

- It should be concise, clear, and relevant to the field of study.

- A well-designed abstract should be unifying and coherent.

- It is easy to grasp and free of technical jargon.

- It is written impartially and objectively.

What are the various sections of an ideal Abstract?

By now, you must have gained some concrete idea of the essential elements that your abstract needs to convey . Accordingly, the information is broken down into six key sections of the abstract, which include:

An Introduction or Background

Research methodology, objectives and goals, limitations.

Let's go over them in detail.

The introduction, also known as background, is the most concise part of your abstract. Ideally, it comprises a couple of sentences. Some researchers only write one sentence to introduce their abstract. The idea behind this is to guide readers through the key factors that led to your study.

It's understandable that this information might seem difficult to explain in a couple of sentences. For example, think about the following two questions like the background of your study:

- What is currently available about the subject with respect to the paper being discussed?

- What isn't understood about this issue? (This is the subject of your research)

While writing the abstract’s introduction, make sure that it is not lengthy. Because if it crosses the word limit, it may eat up the words meant to be used for providing other key information.

Research methodology is where you describe the theories and techniques you used in your research. It is recommended that you describe what you have done and the method you used to get your thorough investigation results. Certainly, it is the second-longest paragraph in the abstract.

In the research methodology section, it is essential to mention the kind of research you conducted; for instance, qualitative research or quantitative research (this will guide your research methodology too) . If you've conducted quantitative research, your abstract should contain information like the sample size, data collection method, sampling techniques, and duration of the study. Likewise, your abstract should reflect observational data, opinions, questionnaires (especially the non-numerical data) if you work on qualitative research.

The research objectives and goals speak about what you intend to accomplish with your research. The majority of research projects focus on the long-term effects of a project, and the goals focus on the immediate, short-term outcomes of the research. It is possible to summarise both in just multiple sentences.

In stating your objectives and goals, you give readers a picture of the scope of the study, its depth and the direction your research ultimately follows. Your readers can evaluate the results of your research against the goals and stated objectives to determine if you have achieved the goal of your research.

In the end, your readers are more attracted by the results you've obtained through your study. Therefore, you must take the time to explain each relevant result and explain how they impact your research. The results section exists as the longest in your abstract, and nothing should diminish its reach or quality.

One of the most important things you should adhere to is to spell out details and figures on the results of your research.

Instead of making a vague assertion such as, "We noticed that response rates varied greatly between respondents with high incomes and those with low incomes", Try these: "The response rate was higher for high-income respondents than those with lower incomes (59 30 percent vs. 30 percent in both cases; P<0.01)."

You're likely to encounter certain obstacles during your research. It could have been during data collection or even during conducting the sample . Whatever the issue, it's essential to inform your readers about them and their effects on the research.

Research limitations offer an opportunity to suggest further and deep research. If, for instance, you were forced to change for convenient sampling and snowball samples because of difficulties in reaching well-suited research participants, then you should mention this reason when you write your research abstract. In addition, a lack of prior studies on the subject could hinder your research.

Your conclusion should include the same number of sentences to wrap the abstract as the introduction. The majority of researchers offer an idea of the consequences of their research in this case.

Your conclusion should include three essential components:

- A significant take-home message.

- Corresponding important findings.

- The Interpretation.

Even though the conclusion of your abstract needs to be brief, it can have an enormous influence on the way that readers view your research. Therefore, make use of this section to reinforce the central message from your research. Be sure that your statements reflect the actual results and the methods you used to conduct your research.

Good Abstract Examples

Abstract example #1.

Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies.

The abstract:

"Almost all research into the effects of brand placements on children has focused on the brand's attitudes or behavior intentions. Based on the significant differences between attitudes and behavioral intentions on one hand and actual behavior on the other hand, this study examines the impact of placements by brands on children's eating habits. Children aged 6-14 years old were shown an excerpt from the popular film Alvin and the Chipmunks and were shown places for the item Cheese Balls. Three different versions were developed with no placements, one with moderately frequent placements and the third with the highest frequency of placement. The results revealed that exposure to high-frequency places had a profound effect on snack consumption, however, there was no impact on consumer attitudes towards brands or products. The effects were not dependent on the age of the children. These findings are of major importance to researchers studying consumer behavior as well as nutrition experts as well as policy regulators."

Abstract Example #2

Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. The abstract:

"The research conducted in this study investigated the effects of Facebook use on women's moods and body image if the effects are different from an internet-based fashion journal and if the appearance comparison tendencies moderate one or more of these effects. Participants who were female ( N = 112) were randomly allocated to spend 10 minutes exploring their Facebook account or a magazine's website or an appearance neutral control website prior to completing state assessments of body dissatisfaction, mood, and differences in appearance (weight-related and facial hair, face, and skin). Participants also completed a test of the tendency to compare appearances. The participants who used Facebook were reported to be more depressed than those who stayed on the control site. In addition, women who have the tendency to compare appearances reported more facial, hair and skin-related issues following Facebook exposure than when they were exposed to the control site. Due to its popularity it is imperative to conduct more research to understand the effect that Facebook affects the way people view themselves."

Abstract Example #3

The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students

"The cellphone is always present on campuses of colleges and is often utilised in situations in which learning takes place. The study examined the connection between the use of cell phones and the actual grades point average (GPA) after adjusting for predictors that are known to be a factor. In the end 536 students in the undergraduate program from 82 self-reported majors of an enormous, public institution were studied. Hierarchical analysis ( R 2 = .449) showed that use of mobile phones is significantly ( p < .001) and negative (b equal to -.164) connected to the actual college GPA, after taking into account factors such as demographics, self-efficacy in self-regulated learning, self-efficacy to improve academic performance, and the actual high school GPA that were all important predictors ( p < .05). Therefore, after adjusting for other known predictors increasing cell phone usage was associated with lower academic performance. While more research is required to determine the mechanisms behind these results, they suggest the need to educate teachers and students to the possible academic risks that are associated with high-frequency mobile phone usage."

Quick tips on writing a good abstract

There exists a common dilemma among early age researchers whether to write the abstract at first or last? However, it's recommended to compose your abstract when you've completed the research since you'll have all the information to give to your readers. You can, however, write a draft at the beginning of your research and add in any gaps later.

If you find abstract writing a herculean task, here are the few tips to help you with it:

1. Always develop a framework to support your abstract

Before writing, ensure you create a clear outline for your abstract. Divide it into sections and draw the primary and supporting elements in each one. You can include keywords and a few sentences that convey the essence of your message.

2. Review Other Abstracts

Abstracts are among the most frequently used research documents, and thousands of them were written in the past. Therefore, prior to writing yours, take a look at some examples from other abstracts. There are plenty of examples of abstracts for dissertations in the dissertation and thesis databases.

3. Avoid Jargon To the Maximum

When you write your abstract, focus on simplicity over formality. You should write in simple language, and avoid excessive filler words or ambiguous sentences. Keep in mind that your abstract must be readable to those who aren't acquainted with your subject.

4. Focus on Your Research

It's a given fact that the abstract you write should be about your research and the findings you've made. It is not the right time to mention secondary and primary data sources unless it's absolutely required.

Conclusion: How to Structure an Interesting Abstract?

Abstracts are a short outline of your essay. However, it's among the most important, if not the most important. The process of writing an abstract is not straightforward. A few early-age researchers tend to begin by writing it, thinking they are doing it to "tease" the next step (the document itself). However, it is better to treat it as a spoiler.

The simple, concise style of the abstract lends itself to a well-written and well-investigated study. If your research paper doesn't provide definitive results, or the goal of your research is questioned, so will the abstract. Thus, only write your abstract after witnessing your findings and put your findings in the context of a larger scenario.

The process of writing an abstract can be daunting, but with these guidelines, you will succeed. The most efficient method of writing an excellent abstract is to centre the primary points of your abstract, including the research question and goals methods, as well as key results.

Interested in learning more about dedicated research solutions? Go to the SciSpace product page to find out how our suite of products can help you simplify your research workflows so you can focus on advancing science.

The best-in-class solution is equipped with features such as literature search and discovery, profile management, research writing and formatting, and so much more.

But before you go,

You might also like.

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

How to Write an Abstract

An abstract of a work, usually of an essay, is a concise summary of its main points. It is meant to concentrate the argument of a work, presenting it as clearly as possible.

The abstract often appears after the title and before the main body of an essay. If you are writing an abstract as part of an assignment, you should check with your instructor about where to place it.

Here are a few guidelines to follow when composing an abstract:

- In general, avoid too much copying and pasting directly from your essay, especially from the first paragraph. An abstract is often presented directly before an essay, and it will often be the first thing readers consult after your title. You wouldn’t repeat your ideas verbatim in the body of your essay, so why would you do that in an abstract? Consider the abstract part of the work itself.

- Start off strong. An abstract should be a mini essay, so it should begin with a clear statement of your argument. This should be the first sentence or two.

- Abstracts vary in length. But a good rule is to aim for five to seven sentences. The bulk of the abstract will review the evidence for your claim and summarize your findings.

- Avoid complicated syntax. Long sentences and intricate phrasing have their place in essays, but the abstract should be concise. It is not the place for ambitious grammar.

- The last sentence or two should point to any conclusions reached and the direction future research might take. Like the first sentence, the last should be provocative and direct. Leave your readers wanting to read your essay.

In what follows, the authors have written an effective abstract that adheres to the basic principles above:

Literary critics have long imagined that T. S. Eliot’s The Sacred Wood (1920) shaped the canon and methods of countless twentieth-century classrooms. This essay turns instead to the classroom that made The Sacred Wood : the Modern English Literature extension school tutorial that Eliot taught to working-class adults between 1916 and 1919. Contextualizing Eliot’s tutorial within the extension school movement shows how the ethos and practices of the Workers’ Educational Association shaped his teaching. Over the course of three years, Eliot and his students reimagined canonical literature as writing by working poets for working people—a model of literary history that fully informed his canon reformation in The Sacred Wood . This example demonstrates how attention to teaching changes the history of English literary study. It further reveals how all kinds of institutions, not just elite universities, have shaped the discipline’s methods and canons. (Buurma and Heffernan)

This abstract uses the first two sentences to establish the essay’s place in its field of study and to suggest how it intervenes in existing scholarship. The syntax is direct and simple. The third sentence begins to outline how the authors will support their argument. They aim to demonstrate the relevance of Eliot’s teaching to his ideas about literature, and so they move next to discuss some of the details of that teaching. Finally, the abstract concludes by telling us about the consequences of this argument. The conclusion both points to new directions for research and tells us why we should read the essay.

Buurma, Rachel Sagner, and Laura Heffernan. Abstract of “The Classroom in the Canon: T. S. Eliot’s Modern English Literature Extension Course for Working People and The Sacred Wood. ” PMLA , vol. 133, no. 2, Mar. 2018, p. 463.

Estate Best 18 July 2021 AT 05:07 AM

Please how will I write an abstract for my own poem collections?

Your e-mail address will not be published

Marc Simoes 01 April 2022 AT 04:04 PM

I am teaching students how to format and write an abstract, but I find no precise guidelines in the MLA Handbook. Should the first word of the abstract body text begin with the word "Abstract" followed by a period or colon and then the abstract content? Should the word "Abstract" be underlined? Over the years, I was taught both of these ways by different instructors, but I haven't found any definitive instructions, and now my students are asking me the correct format. Please help! Thank you!

Joseph Wallace 12 April 2022 AT 01:04 PM

Although publishers like the MLA will use their own house style guidelines for abstracts in published material, there is no one correct way for students to format their abstracts. Instructors should decide what works best for their classes and assignments.

Lorraine Belo 17 April 2022 AT 10:04 PM

Can you write a brief abstract about your MLA writing

Subrata Biswas 13 July 2023 AT 10:07 AM

Generally, the abstract is written in Italics. Is there any rule as such?

Joseph Wallace 31 July 2023 AT 10:07 AM

Thanks for your question. There is no rule saying that abstracts need to be written in italics. Some publications use italics for abstracts and some do not.

Dhan 07 January 2024 AT 12:01 PM

Should I write key words at the end of the abstract of Phd dissertation?

Join the Conversation