- School of Thought Blog

Biden’s FY 2022 Budget—And What It Means for Education Funding

Late last week, President Joe Biden released his administration’s proposed FY 2022 budget . NASSP applauded this proposal, as it contains the robust funding that so many federal educational programs need. Below, we break down some of the highlights of the president’s proposal and walk through what happens next.

- Overall Proposed Funding Level: The president’s FY 2022 budget proposal asks for $102.8 billion for the nation’s K–12 schools during the 2022–23 school year. This robust request would provide schools with the reliable funding they require to continue meeting the needs of each student. It is promising to see such a proposal containing significant investments in our nation’s students and schools, particularly with increased funding and resources to hire school counselors, nurses, and mental health professionals.

- School Leader Recruitment and Support Program Funding: The president’s proposal reinvigorates the School Leader Recruitment and Support program and recommends that it be funded at $30 million for FY 2022—a huge win for principals and assistant principals. The School Leader Recruitment and Support program, which NASSP worked to have Congress include in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), provides competitive grants to local education agencies, state education agencies, the Bureau of Indian Education, or related consortia to improve the recruitment, preparation, placement, support, and retention of effective principals or other school leaders in high-need schools. The funds suggested in the president’s proposal would support grants for high-quality professional development for principals and other school leaders and high-quality training for aspiring principals and school leaders.

- Title I Funding: Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) provides formula grants to states and, in turn, to districts to support academic success for disadvantaged children. The Biden administration’s FY 2022 proposal asks for $36.5 billion in funding for Title I, which is a $20 billion increase over FY 2021 levels, and creates a new Title I equity grant program that encourages states to rethink how they provide equitable funding to schools.

- Title II Funding: Title II of the ESEA provides formula grants to states to increase academic achievement by improving teacher and principal quality. This program also helps districts and schools invest in principal residencies, job-embedded and cohort-based professional learning, and mentorship opportunities for aspiring principals. The Biden administration’s FY 2022 proposal asks for $2.148 billion for Title II, which is a $5 million increase from the FY 2021 allocated level of $2.143 billion.

- Title IV Funding: Title IV of the ESEA is a flexible block grant program that allows for investments in safe and healthy schools, a well-rounded education, and investments in the effective use of technology. The Biden administration’s FY 2022 proposal asks for level funding of Title IV at the same level as FY 2021, which was $1.22 billion.

- Funding for Other Important Programs: The Biden administration’s FY 2022 proposal asks for $15.5 billion for IDEA funding, which is a $2.6 billion increase over FY 2021. The budget also requested level funding of $192 million for the Comprehensive Literacy State Development grants program, which helps advance the reading and writing skills of students from birth through grade 12. This includes English-language learners and students with disabilities. The Career and Technical Education (CTE) State Grants program, which provides support for states and communities to implement high-quality CTE programs to meet the demands of the 21st-century economy and workforce, also receives a boost. The president’s FY 2022 budget proposes that the CTE State Grants receive a $20 million increase over last year, to a total $1.355 billion for FY 2022.

What Happens Next

You may have noticed that throughout this post we have referred to the administration’s FY 2022 budget as a “proposal.” Why is this not a final budget, only a proposed one? That’s because, under the U.S. Constitution , Congress has the “power of the purse.” What this means in practice is that the president’s proposal will be taken under consideration by Congress, and that the pertinent committees that decide how to appropriate federal funds will also debate their own spending proposals. All of these proposals ideally will be debated over the summer, and wrapped up before the end of the current fiscal year on September 30, 2021.

However, in recent years, Congress has been unable to come to a bipartisan agreement on increased funding levels for all federal agencies, and has as a result passed what are known as “ continuing resolutions ,” or “CRs” in Washington parlance. CRs are not ideal because they are stopgap measures to prevent the federal government from running out of money and do not actually adjust funding to reflect the latest needs of federal agencies and our country. NASSP remains hopeful that this year’s spending discussions will not result in another CR, but we will engage with representatives, senators, and the administration to advocate for the federal funding needs of school leaders, educators, and students no matter what course the funding discussion takes. Stay tuned for updates from NASSP over the summer and opportunities for your voice to be heard as Congress finalizes the education spending bills.

Good Morning, Will there be any discussion regarding making an increase in teacher salaries? The level of compensation “We” receive for the important job that “We” do, doesn’t reflect the level of effort put into our daily tasks, and responsibility “We” have for purchasing supplies.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- More Networks

Your Education Road Map

Politics k-12®.

ESSA. Congress. State chiefs. School spending. Elections. Education Week reporters keep watch on education policy and politics in the nation’s capital and in the states. Read more from this blog.

Biden Pitches 41 Percent Spending Increase for Education Next Year on Top of COVID-19 Aid

- Share article

President Joe Biden is proposing major spending increases for the U.S. Department of Education in the next fiscal year—including major boosts for disadvantaged students, special education, and wraparound services at community schools—and said the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on students and educators has made additional funding more urgent.

An overview of the president’s fiscal 2022 spending proposal that the Biden administration released Friday includes $102.8 billion in discretionary aid for the Education Department. That’s an increase of nearly $30 billion, or approximately 41 percent, from the agency’s current discretionary budget of about $73 billion that lawmakers approved late last year.

Congress often ignores presidents’ annual spending requests, including high-profile proposals and major increases or decreases in spending on established programs. However, Biden might find a somewhat friendlier audience for his ideas in this Congress, which Democrats control, than other presidents.

Biden wants the following notable increases at the Education Department and elsewhere:

- $36.5 billion for Title I aid to disadvantaged students, an increase of $20 billion over current funding.

- $15.5 billion in Individuals with Disabilities Education Act grants to states, a $2.6 billion increase.

- $1 billion for K-12 schools to use to hire more counselors, nurses, and mental health professionals.

- $11.9 billion for Head Start early-education program at the Department of Health and Human Services, a $1.2 billion bump.

- $100 million in a new grant program to foster increased diversity in schools. That seems to pick up where the Obama administration left off .

The proposal also has a big increase for full-service community schools, which provide wraparound services, although just how big that increase would be isn’t clear. Right now, federal grants to community schools total $30 million; the spending request at one point says the president wants $430 million for those schools, yet in a different section, that request is for $443 million. The White House and the Education Department did not immediately respond to requests for clarification about how much Biden wants for those grants.

Message to Congress: ‘More work remains’

Biden’s spending pitch comes nearly a month after he signed the American Rescue Plan, a $1.9 trillion aid package that includes nearly $130 billion for K-12 education. Combined with two previous COVID-19 relief deals, schools have received nearly $200 billion in emergency federal aid for K-12, representing an unprecedented infusion of money from Washington that will impact schools for years to come.

Noting that the American Rescue Plan provides “essential” resources but that “more work remains” to help people recover from the pandemic, the Biden spending plan goes on to say that, “The discretionary request includes proposals that would contribute to a stronger, more inclusive economy over the long term by investing in children and young people, advancing economic security, opportunity, and fairness for all Americans.” (Discretionary spending is money appropriated annually by Congress.)

“President Biden’s discretionary budget request is the welcome news that educators and students deserve after a very difficult last year,” said Anna Maria Chávez, the executive director and CEO of the National School Boards Association, in a statement.

Unsurprisingly, the request is very different from former President Donald Trump’s budget blueprints for the Education Department.

In Trump’s fiscal 2021 spending plan released early last year, for example, he sought to roll 29 programs into a block grant, as part of an overall plan to reduce the department’s budget . Trump also sought cuts to the department’s overall budget in previous fiscal years, although Congress rejected that and approved relatively small increases to Title I and other big-ticket programs throughout Trump’s presidency, including when Republicans controlled the House and Senate.

During his presidential campaign, Biden promised to triple Title I funding , as did other Democratic candidates. His new spending blueprint for fiscal 2022 falls short of that pledge, although the bulk of the American Rescue Plan’s K-12 aid is being allocated to local schools through the Title I formula. (Biden made that pledge before the coronavirus pandemic began.)

The overview released by the White House Friday doesn’t outline his plans for every line item in the Education Department’s budget. It doesn’t specifically mention charter schools, for example. Funding for the Charter Schools Program, which is designed to support the creation of high-quality charters, has become more controversial in recent years. The program is getting $440 million in fiscal 2021, the same as it got in the previous fiscal year.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- India Today

- Business Today

- Reader’s Digest

- Harper's Bazaar

- Brides Today

- Cosmopolitan

- Aaj Tak Campus

- India Today Hindi

Education Budget 2022 increases by 11.86%: Major areas of union budget allocation, schemes covered, new plans

The education budget 2022 was announced today as part of the union budget 2022 and it has increased by 11.86% from the previous year. here are the major areas of education budget allocation, major schemes covered and new plans for education development..

Listen to Story

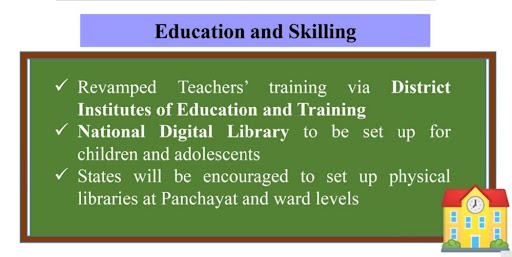

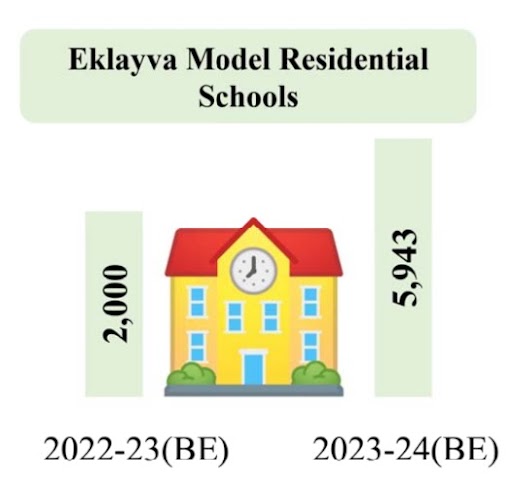

The Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the Budget 2022 today and the education budget focused mainly on digital education, the creation of a digital university, job creation, agricultural universities, skill development of programmers, etc.

The education budget 2022 has been allotted Rs 1,04,278 crore -- a rise of Rs 11,054 crore from the previous year. The education budget allocation for 2021-22 was Rs. 93,223 crores, which was reduced by 6% as compared to the year before. The revised estimate was Rs 88,002 crore.

Education budget 2022 nowhere near 6% of GDP

The National Education Policy, 2020 (NEP) calls for public investment on education to 6% of GDP. India’s education budget has never touched this number yet.

- 2019-20: 2.8%

- 2020-21: 3.1% (as per the revised estimate)

- 2021-22: 3.1% (as per the budget estimate)

Education Budget 2022: Main areas of budget allocation

- Scheme allocation: Rs 51,052.37 crores

- Non-Scheme allocation: Rs. 12,397 crores

- Scheme allocation: Rs 7454.97 crores

- Non-Scheme allocation: Rs. 33,373.38 crores

Focus on skill development and vocational education

The education budget 2022 is focusing a lot on skilling programmes which is a boon for the nation as the Covid-19 pandemic has caused a major hit in this field.

- The Skill Hub Initiative of MoE and MSDE will be launched in 5000 skill centres during the next year.

- ITIs will start courses on skilling.

- The Digital Ecosystem for Skilling and Livelihood DESH-Stack e-portal will be launched for the skilling, upskilling and reskilling of the youth.

- The e-portal will also provide API-based trusted skill credentials, payment and discovery layers to find relevant jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities

- The skill sector is to be reoriented to promote continuous skilling avenues, sustainability, and employability, and the National Skill Qualification Framework (NSQF) will be aligned with dynamic industry needs.

- 750 virtual labs will be created in science and mathematics.

- 75 skilling e-labs will be created for simulated learning environments.

E-learning in regional languages

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a major learning loss for Indian students. Approximately 1.5 million schools and 1.4 million ECD/Anganwadi centres were closed during this period.

Through pandemic waves since last year, most schools closed and re-opened several times. Consequently nearly 247 million children could not go to school for more than a year.

- The ‘One class, one TV channel' programme of PM eVIDYA will be expanded from 12 to 200 TV channels for all states to be able to provide supplementary education in regional languages for Classes 1 to 12 to make up for the loss of formal education due to Covid-19 pandemic, especially for students from rural areas, weaker sections and SC-ST communities.

- Teachers will be encouraged to develop quality e-content in different languages and different subjects so that any teacher or student can access the content from anywhere and get benefitted. A competitive mechanism to promote development of quality e-content by the teachers will be created to ensure empowered teachers and curious students.

- The concept of digital teachers in all spoken languages will be developed. Learner facing e-content will be developed in innovative teaching formats such that all content can be made simultaneously available through different mediums like online, on TV and on radio.

Job creation

Unemployment issues have been weighing heavy on India’s youth.

- Nirmala Sitharaman said the government was targeting the creation of 60 lakh jobs in 14 sectors through PM Gati Shakti and the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme for achieving Aatmanirbhar Bharat.

- Sectors of animation, gaming, and comics could bring in an employment boom. An animation, visual effects, gaming, and comic (AVGC) promotion task force will be set up to realize the potential of this sector is also a very welcome step. This will also aid in experiential learning.

- Startups will be promoted to facilitate ‘Drone Shakti’ and for Drone-As-A-Service which will create employment opportunities.

Focus on specialised learning in higher education

Certain sectors like the agriculture industry and the urban planning industries in India are being given more focus for better higher education.

- States will be encouraged to revise the syllabi of agricultural universities to meet the needs of natural, zero-budget, and organic farming, and modern-day agriculture.

- Five existing academic institutions in different regions will be developed in centres of excellence in urban planning. These centres will be provided endowment funds of Rs 250 crore each for developing India-specific knowledge in urban planning and design.

- AICTE will take the lead to improve syllabi, quality and access of urban planning courses in other institutions.

- World-class foreign universities and institutions will be allowed in the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City or GIFT City to offer courses in various subjects like Financial Management, FinTech, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.

Mental health of students

- The programme will include a network of 23 tele mental health centres of excellence.

- “NIMHANS will be the nodal centre, and IIIT Bangalore will provide technological support for the mental health programme,” Nirmala Sitharaman said.

“The E-Health Research Center at IIITB has been working with NIMHANS, National Health Mission, Govt of Karnataka, on e-Manas, a first of its kind, software platform for mental health management," explains Prof TK Srikanth, Head of E-Health Research Center, IIIT Bangalore.

"This has been deployed by the Govt of Karnataka and is being extended to the monitoring of the DMHP programme as well as psychiatric rehabilitative services. Now, IIITB will help integrate eManas with tele-health services, thus providing a comprehensive platform for mental health care that can scale up nationally," he adds.

Read: Did the education budget 2022-23 satisfy the expectations of teachers?

Read: Education Budget 2022: From better digital infrastructure to better education loans, here's what experts want

Read: Budget 2022: Key updates for the education sector

Refine Results By

The federal budget in fiscal year 2022: an infographic.

The federal deficit in 2022 was $1.4 trillion, equal to 5.5 percent of gross domestic product, almost 2 percentage points greater than the average over the past 50 years.

Related Publications

- CBO Releases Infographics About the Federal Budget in Fiscal Year 2022 March 28, 2023

- Discretionary Spending in Fiscal Year 2022: An Infographic March 28, 2023

- Mandatory Spending in Fiscal Year 2022: An Infographic March 28, 2023

- Revenues in Fiscal Year 2022: An Infographic March 28, 2023

What’s in Biden’s budget proposal

The Biden administration is seeking massive funding increases toward education, health and the environment, while maintaining current spending levels on defense and homeland security, according to a budget request unveiled Friday. The release begins the annual negotiation process between the president and Congress to determine how funds should be distributed across the government.

Proposed changes to base discretionary funding in Biden’s budget

President Biden’s budget would increase spending by more than 10 percent in 11 of the 15 Cabinet departments. This is a dramatic change from President Donald Trump’s proposals , which often sought to cut spending. Included in most departments’ spending increases is money to address climate change.

[ Biden seeks huge funding increases for education, health care and environmental protection in first budget request to Congress ]

The budget document includes an array of proposals specifically aimed at helping vulnerable populations, including resources for high-poverty schools, vouchers to reduce homelessness and money to combat the opioid epidemic.

The budget plan includes discretionary spending only — the portion of government spending that is set by annual appropriation acts. Excluded is mandatory spending, such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Biden is expected to release a full budget later this spring.

Don’t expect this exact budget proposal to become reality. While Democrats control both the Senate and the House, their margins are slim, so there’s sure to be debate and compromise about where to spend the money and how much the government should grow.

[ Biden budget seeks to flip script on Trump administration’s spending priorities ]

Biden’s plan is not just a departure from the cuts that Trump sought. For many departments, it also represents a much larger spending increase than what Obama sought for most of his presidency.

For some notable departments, here’s how the past 13 presidential budgets compared in proposed vs. enacted spending.

For Defense, Biden’s ask is below both Obama’s and Trump’s, while for international funding and the EPA he falls short of the monumental requests that Obama made in his first budget.

Here are more details about what’s in each agency’s proposal.

Jump to department

The Biden administration’s proposal for the USDA places heavy focus on rural communities, with increased funding for broadband initiatives, water infrastructure, clean energy and initiatives to address rural poverty.

[ Read the full Biden budget proposal ]

The proposal also includes a $1 billion increase in nutritional safety net programs, additional funding for initiatives in the March stimulus bill and money toward some of the priorities laid out in the American Jobs Plan.

Key proposed changes

- Proposes funds for infrastructure priorities such as rural broadband access, safe drinking water and addressing orphan oil and gas wells.

- Increases funding for food assistance programs by more than $1 billion.

- Expands funding for rural clean energy development by $1.4 billion.

- Establishes an equity commission to review current farm programs and increases funding for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights at the USDA.

The big increase in spending for the Commerce Department would be spread across a number of programs, including research into climate change.

The White House wants a large increase for Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to go toward climate research and helping regional and local leaders with “climate data and tools.”

It also seeks to boost Commerce’s ability to help U.S. companies develop semiconductors and other items that the White House believes are of strategic national importance. And there’s a large proposed increase in a program that aims to assist minority-owned businesses.

The proposal for the Pentagon actually represents a slight decrease of about 0.4 percent when adjusted for inflation. The proposal is likely to draw barbs from Republicans, who want increases of 3 to 5 percent annually to upgrade the military, citing the U.S. military competition with China.

Liberal Democrats had called for cuts of at least 10 percent in defense spending, while the Trump administration had forecast spending $722 billion on defense if Donald Trump were reelected.

- The Biden team cites concerns about China in its defense budget request. Priorities include continued investments in building up the Navy, which the Biden administration said is “critical to reassuring allies and signaling U.S. resolve to potential adversaries.” It also includes investment in long-range missiles, which are seen as key to any conflict in the Pacific.

- The budget documents signal a process called “divest legacy systems,” the elimination of some older military equipment. Those kinds of cuts have run into trouble with Congress in the past as they can affect jobs and spending in the home districts of lawmakers.

- The Pentagon during the Biden administration will prioritize climate change, with money set aside to make military installations more resilient.

The increase of $20 billion for the Title I program represents a historic increase for a program that funnels federal dollars to schools serving a significant number of children in poverty. The proposal would more than double funding for the program, to $36.5 billion. That falls short of Biden’s campaign promise to triple spending on the program. Still, it would represent a huge increase, particularly because it comes on top of the rescue act, which just pumped $122 billion to K-12 schools, most of it allocated by the Title I formula.

On higher education, Biden had promised to double Pell Grants, which help low- and moderate-income students pay for college. His proposal for a $400 increase to the maximum award, now at $6,495, falls far short of that. But it would increase spending on the program, now at about $30 billion, by $3 billion. He also would make “dreamers,” who came to the country illegally as children, eligible for the program.

- Proposes $2.6 billion more for special education services to students with disabilities over last year’s allocation. That would bring the total federal contribution to $15.6 billion, about 15 percent of the total costs, and about even with current funding when emergency spending is included. Biden has said he will put the government on a path to funding 40 percent of the total within 10 years.

- Significantly ramps up funding for community schools, which provide comprehensive services to students and their families, and creates a new $100 million grant program to promote racial and economic desegregation.

The White House wants to boost resources for the department with a sprawling portfolio that includes conducting physics experiments, running supercomputers and researching alternative forms of producing energy. But the bulk of the department’s budget goes to maintaining the nation’s nuclear weapon arsenal.

- Spends more than $8 billion, amounting to an increase of at least 27 percent, on the next generation of nuclear reactors, electric vehicles and other alternatives to burning fossil fuels.

- Provides $1 billion to two start-up incubators meant to fund technological breakthroughs in combating climate change.

- Gives $7.4 billion, or a $400 million boost, to the Office of Science, which leads government research into physics, chemistry and other basic science at national laboratories across the country.

Biden is proposing a big funding increase to the agency that will be at the center of his administration’s fight against climate change and the disproportionate impact pollution has on poor and minority communities.

The boost stands in contrast to the deep budget cuts proposed under Trump, who tried unsuccessfully to eliminate several dozen agency programs altogether. Yet even under President Barack Obama, the EPA’s budget remained stagnant as gridlock gripped Congress.

- Adds $48 million in funding for the agency’s Office of Air and Radiation to hire back staff lost under Trump and write new rules combating climate change and stopping the formation of smog in cities.

- Provides $3.6 billion for water infrastructure, a $625 million boost above last year, to replace lead water lines, repair septic systems and make other improvements.

- Spends $936 million on a new environmental justice initiative meant to improve air quality and ramp up environmental enforcement in cities and rural areas traditionally overburdened with pollution.

Biden has argued that the coronavirus outbreak has demonstrated the need to robustly fund the nation’s public health response.

The administration would make new investments to fight the opioid epidemic after drug-related overdose deaths spiked during the pandemic and to ramp up the response to ongoing public health challenges like HIV/AIDS.

The budget also calls for new investments in programs to address racial disparities in health care, reduce the risks of childbirth and support survivors of domestic violence.

Biden also vowed to launch new research into the health effects of gun violence and climate change.

- Adds $1.6 billion in funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the biggest annual jump in nearly 20 years, positioned as an investment to head off the next pandemic and restore the embattled agency's luster.

- Adds $9 billion in funding for the National Institutes of Health, including $6.5 billion to establish the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), which would initially focus on cancer and diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

- Adds $3.9 billion in funding targeting the opioid crisis through new grants and resources for states, researchers and other responders. HHS also is proposing to expand the workforce of behavioral health specialists.

- Adds $2.2 billion for the Indian Health Service and proposes other changes to create more predictable funding for the program, responding to complaints from public health experts that efforts to provide care for Native Americans and Alaska Natives have been chronically underfunded.

Biden is proposing a large increase in funding to expand access to affordable housing, address homelessness, modernize deteriorating infrastructure in historically marginalized communities, boost homeownership and enforce laws against housing discrimination.

Biden’s proposal for HUD signals a new era for the embattled agency, whose funding and mission to serve America’s poor was consistently threatened under the Trump administration.

HUD Secretary Marcia L. Fudge said Biden’s funding request “turns the page on years of inadequate and harmful spending requests and instead empowers HUD to meet the housing needs of families and communities across the country.”

- Adds $5.4 billion (for a total of $30.4 billion) to expand federal housing vouchers to help 200,000 additional low-income families, including those at risk of homelessness or people fleeing domestic violence, rent in the private market. The vouchers will also help families who live in racially segregated, poor neighborhoods move to communities with better access to work, transit and educational opportunities.

- Provides $3.5 billion, an increase of $500 million, to prevent and reduce homelessness. The Homeless Assistance Grants would support more than 100,000 additional households, including survivors of domestic violence and homeless youths.

- Provides $1.9 billion, including a $500 million increase, to boost affordable housing supply with new construction and rehabilitation of rental housing.

The administration’s proposal — nearly $5 billion more than Trump’s last proposal — marks a clear about-face from how the previous administration managed the nation’s land.

It provides more money for liberal priorities: more climate science, increased education and law enforcement on tribal lands and an expansion of access to national parks, as well as historical sites, for racial minorities to tell the story of civil rights and human rights struggles.

- Proposes $4 billion for tribal programs, an increase of $600 million from the amount Congress approved last year.

- Instead of increases provided for fossil fuel production under Trump, the current proposal more than doubles the budget to remediate or heal the land scarred by that activity to $450 million.

- Increases funds set aside for adaptations to climate change by $550 million and provides $200 million more for climate studies by agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey.

The Justice Department’s proposal reflects the Biden administration’s new priorities of tougher enforcement of civil rights laws, more federal agents and prosecutors assigned to pursue domestic terrorism cases, and an increase in grants to local law enforcement agencies to fight gun crime and reform police departments.

- Increases discretionary spending for the Civil Rights Division, Community Relations Service and other programs by $33 million for a total of $209 million.

- Spends an additional $101 million to address the growing threat of domestic terrorism. Nearly half of that money would go to the FBI, which has seen its number of domestic terrorism cases double in the past year, while $40 million would go to prosecutor offices to handle the growing workload.

The Biden administration is seeking a major budget increase for the State Department and other international programs in an effort to revitalize Washington’s diplomatic muscle after what it calls “four years of neglect” by the Trump administration.

The Trump White House sought deep cuts at the State Department every year, which Congress largely ignored.

- Proposes $1.2 billion toward helping developing countries reduce carbon emissions.

- Proposes $861 million in assistance to Central America in the hopes of lessening the root causes of migration.

- Proposes an additional $1 billion toward global health security designed to boost research to detect and stamp out future infectious-disease outbreaks “before they become pandemics.”

The administration proposes increasing Labor Department funding to restaff worker protection agencies, expand workforce development programs and address shortcomings in the unemployment system.

- Proposes $2.1 billion to worker protection agencies, an increase of $304 million.

- Increases funding to Registered Apprenticeships by more than 50 percent, requests $100 million to train a clean energy workforce and increases funding to employment services for laid-off workers, low-income adults and at-risk youths.

- Invests $100 million in information technology to address delays and inequities in state unemployment insurance programs.

The Biden administration is proposing new programs to spur rail trips between cities and promote equity in transportation, part of a budget request it described as a “down payment” on its broad aspirations for transforming the nation’s infrastructure to improve quality of life and address climate change.

It marks a major shift in emphasis from Trump administration proposals to cut discretionary spending and privatize transportation assets.

- Creates a new competitive passenger rail grant program, using $625 million to promote passenger rail as a “low-carbon option for intercity travel.”

- Increases funding for Amtrak by 35 percent, to $2.7 billion, providing an expansion along the busy Northeast Corridor and nationwide.

- Raises funding in a major transit grant program by 23 percent, to $2.5 billion, and more than doubles — to $250 million — a separate effort to increase purchases of buses with zero or low emissions.

The increase in Treasury’s budget would seek to allow the Internal Revenue Service to increase audits of tax returns for wealthier Americans and corporations and boost enforcement. Additional money would also be used to expand customer service, both over the phone and in person.

It would also seek to greatly increase funding for Community Development Financial Institutions, which aim to help develop affordable housing and neighborhood reinvestment programs.

The Department of Veterans Affairs would continue to receive spending increases the agency received during the Trump administration, this time with a major boost that includes new money for suicide prevention, women’s health, assistance to homeless veterans and research on toxic exposures.

Including mandatory spending, the total budget for VA would exceed $250 billion.

- Spending on suicide prevention programs, a priority for both the Biden and Trump administrations, would almost double to more than $540 million and include funding to increase the capacity of a crisis line for veterans.

- The agency’s research budget would grow by about 12 percent to almost $900 million. The budget request said the new money would “advance the Department’s understanding of the impact of traumatic brain injury and toxic exposure on long-term health outcomes while continuing to prioritize research focused on the needs of disabled veterans.”

Devlin Barrett , Dan Diamond , Darryl Fears , Peter Finn , Dino Grandoni , Tracy Jan , Dan Lamothe , Michael Laris , Laura Meckler , Damian Paletta and Lisa Rein contributed to this report.

Report | Budget, Taxes, and Public Investment

Public education funding in the U.S. needs an overhaul : How a larger federal role would boost equity and shield children from disinvestment during downturns

Report • By Sylvia Allegretto , Emma García , and Elaine Weiss • July 12, 2022

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

Summary

Education funding in the United States relies primarily on state and local resources, with just a tiny share of total revenues allotted by the federal government. Most analyses of the primary school finance metrics—equity, adequacy, effort, and sufficiency—raise serious questions about whether the existing system is living up to the ideal of providing a sound education equitably to all children at all times. Districts in high-poverty areas, which serve larger shares of students of color, get less funding per student than districts in low-poverty areas, which predominantly serve white students, highlighting the system’s inequity. School districts in general—but especially those in high-poverty areas—are not spending enough to achieve national average test scores, which is an established benchmark for assessing adequacy. Efforts states make to invest in education vary significantly. And the system is ill-prepared to adapt to unexpected emergencies.

These challenges are magnified during and after recessions. Following the Great Recession that began in December 2007, per-student education revenues plummeted and did not return to pre-recession levels for about eight years. The recovery in per-student revenues was even slower in high-poverty districts. This report combines new data on funding for states and for districts by school district poverty level, and over time, with evidence documenting the positive impacts of increasing investment in education to make a case for overhauling the school finance system. It calls for reforms that would ensure a larger role for the federal government to establish a robust, stable, and consistent school funding plan that channels sufficient additional resources to less affluent students in good times and bad. Furthermore, spending on public education should be retooled as an economic stabilizer, with increases automatically kicking in during recessions. Such a program would greatly mitigate cuts to public education as budgets are depleted, and also spur aggregate demand to give the economy a needed boost.

Following are key findings from the report:

Our current system for funding public schools shortchanges students, particularly low-income students. Education funding generally is inadequate and inequitable; It relies too heavily on state and local resources (particularly property tax revenues); the federal government plays a small and an insufficient role; funding levels vary widely across states; and high-poverty districts get less funding per student than low-poverty districts.

Those problems are magnified during and after recessions. Funding inadequacies and inequities tend to be aggravated when there is an economic downturn, which typically translates into problems that persist well after recovery is underway. After the 2007 onset of the Great Recession, for example, funding fell, and it took until 2015–2016, on average, to return to their pre-recession per-student revenue and spending levels. For high-poverty school districts, it took even longer—until 2016–2017—to rebound to their pre-recession revenue levels. And even after catching up with pre-recession levels, revenue levels in high-poverty districts lag behind the per-student funding in low-poverty districts. The general, long-standing funding inadequacies and inequities combined with the worsening of these problems during and in the aftermath of recessions have both short- and long-term repercussions that are costly for the students as well as for the country.

Increased federal spending on education after recessions helps mitigate funding shortfalls and inequities. Without increased federal education spending after recessions, school districts would suffer from an even greater decline in funding and even wider gaps between funding flowing to low-poverty and high-poverty districts.

Increased spending on education could help boost economic recovery. While Congress has enacted one-time education spending increases in difficult economic times, spending on public education should be considered one of the automatic stabilizers in our economic policy toolkit, designed to automatically increase and thus spur aggregate demand when private spending falls. Deployed this way, education spending becomes part of a set of large, broadly distributed programs that are countercyclical, i.e., designed to kick in when the economy overall is contracting and thus stave off or lessen the severity of a downturn. Along with other automatic stabilizers such as unemployment insurance, education spending thus would provide a stimulus to boost economic recovery.

We need an overhaul of the school finance system, with reforms ensuring a larger role for the federal government. In light of the concerns outlined in this report, policymakers must think differently both about school funding overall and about school funding during recessions. Public education is a public good, and as noted in this report, one that helps to stabilize the entire economy at critical points. Therefore, public spending on education should be treated as the public investment it is. While we leave it to policymakers to design specific reforms, we recommend an increased role for the federal government grounded in substantial, well targeted, consistent investment in the children who are our future, the professionals who help these children attain that future, and the environments in which they work. To establish a robust, stable, and consistent school funding plan that supports all children, investments need to be proportional to the size of the problems and to the societal and economic importance of the sector.

Introduction

The hope for the public education system in the United States is to provide a sound education equitably to all children regardless of where they live or into which families they are born. However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed four interrelated, long-standing realities of U.S. public education funding that have long made that excellent, equitable education system impossible to achieve. First, inadequate levels of funding leave too many students unable to reach established performance benchmarks. Second, school funding is inequitable, with low-income students often and communities of color consistently lacking resources they need to meet their needs. Third, the level of funding reflects an overall underinvestment in education—that is, the U.S. is not spending as much as it could afford to spend in normal times. Fourth, given that educational investments are not sufficient across many districts even during normal times, schools are unable to make preparations to cope with emergencies or other unexpected circumstances. An added, less known feature is that economic downturns make all four of these problems worse. Downturns exacerbate funding inadequacies, inequities, underinvestment, and unpreparedness, causing cumulative harm to students, communities, and the public education system, and clawing back any prior progress. The severity of these problems varies widely across states and districts, as do the strength of states’ and localities’ economic and social protection systems, which may either compensate for or compound the problems.

The pandemic-led recession made these four major financial barriers to an excellent, equitable education system more visible, leading to serious questions about the U.S. education-funding model, which relies heavily on local and state revenues and draws only a small share of funding from the federal government. While public education is one of our greatest ideals and achievements—a free, quality education for every child regardless of means and background—the U.S. educational system is in need of significant improvements.

As the report will show, the core barriers to delivering universally excellent U.S. public education for all children—funding inadequacies and inequities that are exacerbated during tough economic times—were present in the system from the very start. They are the outcomes of a funding system that is shaped by many layers of policies and legal decisions at the local, state, and federal levels, creating widespread disparities in school finance realities across the thousands of districts across the country in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This complex funding puzzle speaks to the need for a funding overhaul to attain meaningful and widely shared improvements.

In this report, we first provide an overview of the characteristics of the U.S. education funding system. We present data analyses on school finance indicators, such as equity, adequacy, and effort, that expose the shortcomings of funding policies and decisions across the country. We also discuss factors behind some of these shortcomings, such as the heavy reliance on local and state sources of funding.

Second, we illustrate that recessions exacerbate the funding challenges schools face. We parse a multitude of data to present trends in school finance indicators both during and after the Great Recession, demonstrating that the immediate effects of federally targeted funds helped schools navigate recession-induced budget cuts. We also look at the shortfalls and inequitable nature of those investments. We explore how increased federal investments—in good economic times and bad—could help address these long-standing problems. We argue that public education funding is not only an investment in our societal present and future, but also is a ready-made mechanism for countering economic downturns. Economic theory and evidence both demonstrate that large, broadly distributed programs providing public support serve as cushions during economic downturns: they spur overall spending and thus aggregate demand when private spending falls. As we note, there are strong arguments for placing public education spending within the broader category of effective fiscal responses to recessions that are countercyclical—designed to increase spending when spending in the economy overall is contracting and thus stave off or lessen the severity of a downturn. Increases in public education spending during downturns work as automatic stabilizers for schools and provide stimulus to boost economic recovery. We review existing research on the consequences of funding in general and of funding changes—evidence that supports a larger role for the federal government.

Third, we discuss the benefits of rethinking public education funding, along with the societal and economic advantages of a robust, stable, and consistent U.S. school funding plan, both generally and as a countercyclical policy. We show that federal investment that sustains school funding throughout recessions and recoveries would provide three major advantages: It would help boost educational instruction and standards, it would provide continued high-quality instruction for students and employment to the public education workforce, and it would stimulate economic recovery. Education funding, in particular, would blanket the country while also targeting areas with the most need, making the recovery more equitable.

We conclude the report with final thoughts and next steps.

This paper uses several terms to refer to investments in education and to define the U.S. school finance system. Below, we explain how these terms are used in the report:

Revenue indicates the dollar amounts that have been raised through various sources (at the local, state, and federal levels) to support elementary and secondary education. We distinguish between federal, state, and local revenue. Local revenue, in some of our charts, is further divided into local revenue from property taxes and from other sources.

Spending or expenditures indicates the dollar amount devoted to elementary and secondary education. Expenditures are typically divided by function and object (instruction, support services , and noninstructional education activities). We rely on data on current expenditures (instead of total expenditures; see footnotes 2 and 30).

Funding generically refers in this report to the educational investments or educational resources. Mostly, when we use funding we refer to revenue, i.e., to resources available or raised, but funding is also used to refer to the school finance system more broadly, and in that case it could be either referring to revenue or expenditures, depending on the context.

For more information on the list of components under each term, see the glossary in the Documentation for the NCES Common Core of Data School District Finance Survey (F-33), School Year 2017–18 (Fiscal Year 2018) (NCES CCD 2020).

A funding primer

The American education system relies heavily on state and local resources to fund public schools. In the U.S. education has long been a local- and state-level responsibility, with states typically concerned with administration and standards, and local districts charged with raising the bulk of the funds to carry those duties and standards out.

The Education Law Center notes that “states, under their respective constitutions, have the legal obligation to support and maintain systems of free public schools for all resident children. This means that the state is the unit of government in the U.S. legally responsible for operating our nation’s public school systems, which includes providing the funding to support and maintain those systems” (Farrie and Sciarra 2021). Bradbury (2021) explains that state constitutions assign responsibility for “adequate” (“sound,” “basic”) and/or “equitable” public education to the state government. Most state governments delegate responsibility for managing and (partially) funding public pre-K–12 education to local governments, but courts mandate that states remain responsible.

States meet this responsibility by funding their schools “through a statewide method or formula enacted by the state legislature. These school funding formulas or school finance systems determine the amount of revenue school districts are permitted to raise from local property and other taxes and the amount of funding or aid the state is expected to contribute from state taxes. In annual or biannual state budgets, legislatures also determine the actual amount of funding districts will receive to operate their schools” (Farrie and Sciarra 2020).

A quick note on data sources

Some of our analyses rely on district-level data, i.e., the revenues and expenditures use the district as the unit of analysis. We rely on metrics of per-student revenue or per-student spending, i.e., taking into consideration the number of students in the districts. Other analyses use data either by state or for the country, which are typically readily available from the Digest of Education Statistics online. Sometimes the variables of interest are total revenue or expenditures, whereas on other occasions we rely on per-student values. All data sources are explained under each figure and table, and some are also briefly explained in the Methodology.

The federal government seeks to use its limited but targeted funding to promote student achievement, foster educational excellence, and ensure equal access. The major federal agency channeling funding to school districts (sometimes through the states) is the U.S. Department of Education. 1

Figure A shows the percentage distribution of total revenue for U.S. public elementary and secondary schools for the 2017–2018 school year, on average. As illustrated, revenues collected from state and local sources are roughly equal (46.8% and 45.3%, respectively). Two other factors also stand out. First, revenue from property taxes accounts for more than one-third of total revenue (36.6 %). Second, federal funding plays a minimal role, providing less than 8% of total revenue (7.8%). As discussed later in the report, this heavy reliance on local funding is a major driver in the funding challenges districts face.

More than 90% of school funding comes from state and local sources : Revenues for public elementary and secondary schools by source of funds, 2017–2018

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020a).

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Key metrics reveal the four major financial barriers to an excellent, equitable education system

Fully comprehending how school funding works and how it contributes to systemic problems requires drawing on key metrics and characteristics that define the education investments or education funding. Understanding these metrics is the first step toward designing a comprehensive solution.

The adequacy metric tells us that funding is inadequate

Adequacy, one of the most widely used school finance indicators, measures whether the amount raised and spent per student is sufficient to achieve a certain level of output (typically a benchmark of student performance or an educational outcome).

We use the adequacy data provided by Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber (2020). These authors, who use the School Finance Indicators Database, compare current education spending by poverty quintile with spending levels required for students to achieve national average test scores—typically accepted as an educationally meaningful benchmark. The authors’ estimates account for factors that could affect the cost of providing education, including student characteristics, labor-market costs (differences in costs given the regional cost of living), and district characteristics (larger districts for example may enjoy economics of scale).

Figure B reveals that spending is not nearly enough, on average, to provide students with an adequate education. As this figure illustrates, relative to the wealthiest districts, the highest-poverty districts need more than twice as much spending per student to provide an adequate education. As the figure also shows, the gaps between what is spent on each student and what would be required for those students to achieve at the national level widen as the level of poverty increases. Medium- and high-poverty districts are spending, respectively, $700 and $3,078 per student less than what would be required. For the highest-poverty districts, that gap is $5,135, meaning districts there are spending about 30% less than what would be required to deliver an adequate level of education to their students. (Conversely, the two low-poverty quintiles are spending more than they need to reach that benchmark, another indication that funds are being poorly allocated.)

U.S. education spending is inadequate : Per-pupil spending compared with estimated spending required to achieve national average test scores, by poverty quintile of school district, 2017

Notes: District poverty is measured as the percentage of children (ages 5–17) living in the school district with family incomes below the federal poverty line, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The figure shows how much is spent in each of the five types of districts and how much they would need to spend for students to achieve national average test scores.

Source: Adapted from The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems , Second Edition (Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber 2020).

The equity metric tells us that funding is inequitable

An equitable funding system ensures that, all else being equal, schools serving students with greater needs—whether for extra academic, socioemotional, health, or other supports—receive more resources and spend more to meet those needs than schools with a lower concentration of disadvantaged students. Across districts, states, and the country as a whole, this means allocating relatively more funding to districts serving larger shares of high-poverty communities than to wealthier ones. While our funding system does allocate additional funds based on need (e.g., to students officially designated as eligible for “special education” services under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and to children from low-income families through the federal Title I program), in practice, more funding overall goes to lower-needs districts than to those with high levels of student needs.

Figure C compares districts’ per-student revenues and expenditures by poverty level, and shows gaps relative to low-poverty districts. The figure is based on data from what was, when this research was conducted, the most recent version of the Local Education Agency Finance Survey (known as the F-33) (NCES-LEAFS, various years). As shown in the figure, on average, per-student revenue and spending in school districts serving wealthier households exceed revenue and spending in all other districts. In low-poverty districts (i.e., districts with a poverty rate in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution), per-student revenues averaged $19,280 in the 2017–2018 school year, and per-student expenditures averaged $15,910. In the high-poverty districts (i.e., in the top fourth of the poverty distribution), per-student revenues were just $16,570, and per-student expenditures were $14,030. High-poverty districts raise $2,710 less in per-student revenue than the lowest–poverty school districts, reflecting a 14.1% revenue gap—meaning high-poverty districts receive 14.1% less in revenue. Per-student spending in high-poverty districts is $1,880 less than in low-poverty districts, an 11.8% gap. 2 In other words, rather than funding districts to address student needs, we are channeling fewer resources—about 14% less, per student—into districts with greater needs based on their student population.

Districts serving poorer students have less to spend on education than those serving wealthier students

: total per-student revenues by district poverty level, and revenue gaps relative to low-poverty districts, 2017–2018, : total per-student expenditures by district poverty level, and spending gaps relative to low-poverty districts, 2017–2018.

Notes: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars and rounded to the closest $10 and adjusted for each state’s cost of living. Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate is in the top fourth of the poverty distribution.

Extended notes: Sample includes districts serving elementary schools only, secondary schools only, or both; districts with nonmissing and nonzero numbers of students; and districts with nonmissing charter information. Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost of living using the historical Regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021). Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; medium-low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the second fourth of the poverty distribution; medium-high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate (for children ages 5 through 17) is in the third fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate is in the top fourth of the poverty distribution. Amounts are unweighted across districts.

Sources: Authors’ analysis of 2017–2018 Local Education Agency Finance Survey (F-33) microdata from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES-LEAFS 2021) and Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) data from the U.S. Census Bureau (Urban Institute 2021a).

Adequacy and equity are closely intertwined

In recent decades, researchers have explored challenges to both adequacy and equity in U.S. public education. For example, Baker and Corcoran (2012) analyzed the various policies that drive inequitable funding. Likewise, lawsuits that have challenged state funding systems have tended to focus on either the inadequacy or inequity of those schemes. 3

But in reality, especially given extensive variation across states and districts, the two are closely linked and interact with one another. At the state level, for example, apparently adequate levels of funding can mask disparities across districts that innately mean inadequate funding for many, or even most, districts within that state (Farrie and Schiarra 2021). 4

In addition, disparate levels of public investments in education are often made in a context that correlates positively with disparate levels of parents’ private investments in their children’s education and related support (Caucutt et al. 2020; Duncan and Murnane 2016; Kornrich 2016; Schneider, Hastings, and LaBriola 2018). Substantial research on income-based gaps in achievement demonstrates that large and growing wealth inequality plays a role. Parents at the top of the income or wealth ladders, who can and do pour extensive resources into their children’s human capital, constantly set a baseline of performance that can be hard for children and schools without such investment to attain (Reardon 2011; García and Weiss 2017). 5

The “effort” metric tells us that many states are underinvesting in education relative to their capacity

“Effort” describes how generously each state funds its schools relative to its capacity to do so. Researchers measuring effort determine capacity to spend based on state gross domestic product (GDP), which can vary widely (just as wealthier neighborhoods can raise more revenues even with lower tax rates, states with higher GDP and thus greater revenue-raising capacity can attain higher revenue with a lower effort, i.e., generate more resources at a lower cost). The map ( Figure D ), reproduced from Farrie and Sciarra 2021, shows state funding effort from the 2017–2018 school year.

School funding ‘effort’ varies widely across states : Pre-K through 12th grade education revenues as a percentage of state GDP, 2017–2018

This interactive feature is not supported in this browser.

Please use a modern browser such as Chrome or Firefox to view the map.

- Click here to download Google Chrome.

- Click here to download Firefox.

Click here to view a limited version of the map.

Note: “Effort is measured as total state and local [education] revenue (including [revenue for] capital outlay and debt service, excluding all federal funds) divided by the state’s gross domestic product. GDP is the value of all goods and services produced by each state’s economy and is used here to represent the state’s economic capacity to raise funds for schools” (Farrie and Sciarra 2020).

Source: Adapted from Making the Grade 2020: How Fair is School Funding in Your State? (Farrie and Sciarra 2020).

As Farrie and Sciarra (2021) note, states fall naturally into four groups:

- High-effort, high-capacity: States such as Alaska, Connecticut, New York, and Wyoming are high- capacity states with high per-capita GDP, and they are also high-effort states: They use a larger-than-average share of their overall GDP to support pre-K–12 education, which generates high funding levels.

- High-effort, low-capacity : States such as Arkansas, South Carolina, and West Virginia have lower-than-average capacity, with low GDP per-capita, but they are high-effort states. Even with above- average efforts, they yield only average or below-average funding levels.

- Low-effort, high-capacity : States such as California, Delaware, and Washington are high-capacity states that exert low effort toward funding schools. If these states increased their effort even to the national average, they could significantly increase funding levels.

- Low-effort, low-capacity : States such as Arizona, Florida, and Idaho are low-capacity states that also make lower-than-average efforts to fund schools, generating very low funding levels.

Evidence shows that districts and schools lack the resources to cope with emergencies

As the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear, our subpar level of preparation to cope with emergencies or other unexpected needs reflects another aspect of underinvestment. As García and Weiss (2020) not about the COVID-19 pandemic, “Our public education system was not built, nor prepared, to cope with a situation like this—we lack the structures to sustain effective teaching and learning during the shutdown and to provide the safety net supports that many children receive in school.”

Whether due to lack of resources, planning, or other factors, districts, schools, and educators struggled to adapt to the pandemic’s requirements for teaching. Schools were unprepared not only to support learning but also to deliver the supports and services they were accustomed to providing, which go far beyond instruction (García and Weiss 2020). This lack of preparation was the result of both a lack of contingency planning as well as a failure to build up resources to be ready “to adequately address emergency needs and to compensate for the resources drained during the emergencies, as well as to afford the provision of flexible learning approaches to continue education” (García and Weiss 2021).

A lack of established contingency plans to ensure the provision of education in emergency and post-emergency situations, whether caused by pandemics, other natural disasters, or conflicts and wars (as examined by the education-in-emergencies research), prevents countries from being able to mitigate the negative consequences of these emergencies on children’s development and learning. The lack of contingency plans also leaves systems unprepared to help children handle the trauma and stress that come from the most serious events. This body of literature has also shown that access to education and services—and an equitable and compensatory allocation of them—helps reduce the damage that students experience during the crisis and beyond, since such emergencies carry long-term consequences (Anderson 2020; Özek 2020).

Public education’s over-reliance on local funding is a key factor behind the troubling funding metrics

The heavy reliance on local funding described above is at the core of the school finance problems. Extensive research has exposed the challenges associated with this unique American system for funding public schools. 6 The myriad factors that drive school funding—politics and political affiliation, state legislative and judicial decisions, property values, tax rates, and effort, among others—vary substantially from one community to another. Thus, it is not surprising that this system has contributed to institutionalizing inequities, especially in the absence of a strong federal effort to counter them.

It is well understood that the local sources of revenues on which school districts heavily rely are often distributed in a highly inequitable way. Revenues from property taxes, which make up a hefty share of local education revenues, innately favor wealthier communities, as these areas have a much larger capacity to raise funds based on higher property values despite their lower tax rates. 7 These higher property-tax revenues in wealthier areas lead to greater revenues for their districts’ schools, since property-tax revenues account for such a significant share of the total.

State and federal funding are insufficient to compensate for these locally driven inequities

State funding of public education is the largest budget line item for most states. 8 Along with federal funding, state funding is expected to make up for local funding disparities and gaps. 9 Federal funding, in particular through Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), is specifically designed to compensate low-income schools and districts for their lack of sufficient revenues to meet their students’ needs. 10 Similarly, state funding is intended to offset some of the disparities caused by the dependence on local revenues. However, in reality, state and federal sources do not provide enough to less-wealthy school districts to make up for the gap in funding at the local level, as shown in Figure E .

As the figure shows, the U.S. systematically funds schools in wealthier areas at higher levels than those with higher rates of poverty, even after accounting for funding meant to remedy these gaps. On average, local property-tax funding per student is $5,260 lower in the poorest districts than in the wealthiest districts.

Federal and state revenues fail to offset the funding disparities caused by relying on local property tax revenues : How much more or less school districts of different poverty levels receive in revenues than low-poverty school districts receive, all and by revenue source, 2017–2018

Notes: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars, rounded to the closest $10, and adjusted for each state's cost of living. Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate for school-age children (children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution; high-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate is in the top fourth of the poverty distribution.

Extended notes: Sample includes districts serving elementary schools only, secondary schools only, or both; districts with nonmissing and nonzero numbers of students; and districts with nonmissing charter information. Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost-of living using the historical regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021). Low-poverty districts are districts whose poverty rate for school-age children (children ages 5 through 17) is in the bottom fourth of the poverty distribution for that group; medium-low-poverty districts are districts whose school-age children’s poverty rate is in the second fourth (25th–50th percentile); medium-high-poverty districts are districts whose school-age children’s poverty rate is in the third fourth (50th–75th percentile); in high-poverty districts, the rate is in the top fourth. Amounts are unweighted across districts.

Sources: 2017–2018 Local Education Agency Finance Survey (F-33) microdata from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES-LEAFS 2021) and Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) data from the U.S. Census Bureau (Urban Institute 2021a).

While state revenues are a significant portion of funding, they only modestly counter the large locally based inequities. And while federal funding, by far the smallest source of revenue, is being deployed as intended (to reduce inequities), it inevitably falls short of compensating for a system grounded in highly inequitable local revenues as its principal source of funding. As such, although states provide their highest-poverty districts with $1,550 more per student than to their lowest-poverty districts, and federal sources provide their highest-poverty districts with $2,080 more per student than to their lowest-poverty districts, states and the federal government jointly compensate for only about half of the revenue gap for high-poverty districts (which receive a per-student average of $6,330 less in property tax and other local revenues). That large gap in local funding leaves the highest-poverty districts still $2,710 short per student relative to the lowest-poverty districts, reflecting the 14.1% revenue gap shown in Figure C. Even though high-poverty districts get more in federal and state dollars, they get so much less in property taxes that it still puts them in the negative category overall.

Disparities shortchange states’ (and districts’) ability to access and allocate the resources needed for effective education

Given the heavy reliance on highly varied local funding, it is no surprise that there is similarly significant variation across states with respect to almost every aspect of funding discussed here. Table 1 reports federal, state, and local funding for each state and for the District of Columbia, with local funding broken down into three categories.

Revenues for public elementary and secondary schools, by source of funds and by state : Share of each source in total revenue, 2017–2018

Source: National Center for Education Statistics' Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020b).

Nationally, in 2017–2018, local and state sources accounted for 45.3% and 46.8% of total revenue, respectively; just 7.8% comes from the federal government. However, these averages mask substantial variation in the shares of revenue apportioned by each source across states. Local revenue, for example, ranges from just 3.7% of total public-school revenue in Vermont and 18.2% in New Mexico, on the lower end, to a high of 63.4% in New Hampshire. The same is true with respect to state revenue. The state that contributes the smallest share to its education budget is New Hampshire at 31.3%, with Vermont contributing the largest share (89.9%). There is also quite a bit of variation in the share represented by federal funds—from just 4.1% in New Jersey to 15.9% in Alaska. (The cited values are highlighted in the table. We omit the District of Columbia and Hawaii from these rankings because of the unusual composition of their funding streams, but we provide their values in the table.)

As shown earlier in the discussion of the map in Figure E, there are also large disparities in funding effort—how generously each state funds its schools relative to its capacity to do so, based on state GDP. High-effort, high-capacity s tates such as Alaska, Connecticut, New York, and Wyoming use a larger-than-average share of their overall GDP to support pre-K–12 education and they generate high funding levels.

As a result of funding and effort variability across states, the levels of inequity and inadequacy across states also vary substantially (Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber 2020; Farrie and Sciarra 2021). Notably, funding variability translates into significant disparities in overall per-student revenue and per-student spending levels, as shown in Figures F and G . In Wyoming, for example, where effort is relatively high (4.36%; see Figure E) and there is a higher-than-average contribution of state funds to total revenue and a lower-than-average contribution of local funds to total revenue (56.8% and 36.8%, respectively, versus 46.8% and 45.3% averages across the U.S.), per-student revenue is among the highest of any state, nearly $21,000. In contrast, Arizona and North Carolina—which are among the lowest in effort in the country (2.23% and 2.28%, respectively), but where state funds account for 47.1% and 62.1% of the state’s total public education revenues, respectively, and local funds account for 40.4% and only 27.0%, respectively—collect about half of what Wyoming collects per student. (Data accounts for differences in states’ cost of living; see the appendix for more details on our methodology.)

Public education revenues vary widely across states : Per-student revenues for public elementary and secondary schools, by state, 2017–2018

Note: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost-of living using the historical regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021).

Source: National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020b).

Public education expenditures vary widely across states : Per-student expenditures for public elementary and secondary schools, by state, 2017–2018

Note: Amounts are in 2019–2020 dollars using the consumer price index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS-CPI 2021) and rounded to the closest $10. Amounts are adjusted for each state’s cost-of living using the historical Regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2021).

Source: National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics (NCES 2020c).

These substantial disparities in all the school finance indicators, and in per-pupil spending and revenue across states, are mirrored in capacity and investment patterns across districts and, within them, individual schools.

As such, these systemic and persistent inequities play a decisive role in shaping children’s real school experiences. As Raikes and Darling-Hammond (2019) note, “As a country, we inadvertently instituted a school finance system similar to red-lining in its negative impact. Grow up in a rich neighborhood with a large property tax base? You get well-funded public schools. Grow up in a poor neighborhood? The opposite is true. The highest-spending districts in the United States spend nearly 10 times as much as the lowest-spending, with large differentials both across and within states (Raikes and Darling-Hammond 2019). In most states, children who live in low-income neighborhoods attend the most under-resourced schools” (see also Turner et al. 2016 for the underlying data). 11

These gaps in spending capacity touch every aspect of school functioning, including the capacity of teachers and staff to deliver effective instruction, and pose a huge barrier to the excellent school experience that each student should receive. In Pennsylvania, for example, where districts tend to rely heavily on local revenues to finance schools, per-pupil spending ranges dramatically. Indeed, in 2015, the U.S. Department of Education flagged the state as having the biggest school-spending gap of any state in the country (Behrman 2019). One illustrative example is in Allegheny County, on the western side of the state, where the suburban Wilkinsburg school district outside of Pittsburgh spent over $27,000 per student in the 2017–2018 school year, while the more rural South Allegheny school district spent just over $15,000, roughly 45% less.