Cookies on our website

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We'd like to set additional cookies to understand how you use our site. And we'd like to serve you some cookies set by other services to show you relevant content.

Case studies

The csc case study template: corruption case studies.

- Download the CSC Case Study Template for use in your own research or study [PDF 797 KB]

- Book of Case Studies: Understanding Corruption. Order from the UK.

- Book of Case Studies: Understanding Corruption. Order from the US.

The faculty at the Centre for the Study of Corruption (CSC) have developed the CSC Case Study Template for use in teaching and research. It has been extensively field-tested amongst students and forms the basis for an entire module of our online MA in Corruption & Governance.

Case studies are a widely used tool in campaigning and policy-making, both in relation to corruption and other subjects. In an educational context, they are perhaps most frequently and systematically used in business schools, with the Harvard format being widely recognised as an effective device for practical analysis. The CSC Case Study Template is designed to allow a systematic analysis of a case; a judgement to be made as to whether it is or is not a case of corruption; and the presentation of information in a readable form that has multiple end-uses, including policy-making, advocacy, campaigning and education.

We believe the CSC Case Study template offers a useful approach to anti-corruption problem-solving. The theory behind this approach is simple: if you have a good understanding or diagnosis of the problem, you are more likely to find a solution; and the diagnosis needs to examine a case from angles that include the harm, the benefits, the enabling environment, systems failures and the effectiveness of penalties. The CSC Case Study Template is designed to give such a description of a corruption problem, combining a concise narrative with a rigorous analysis from all angles, including the problem of how it came to happen.

The template:

- Provides a systematic analysis of a case of corruption

- Describes and analyses the case in a manner that can be used for campaigning, educating, advocacy or policymaking

- Draws out key insights

- Combines practical and academic approaches

- Gives students and researchers a tool they can use to analyse any case of corruption – including determining whether it is actually a case of corruption.

Case Studies:

- Petty Bribery in the UK [PDF 0.99MB]

Understanding Corruption: how corruption works in practice

Barrington, r., dávid-barrett, e., power, s., hough, d. (2022). understanding corruption: how corruption works in practice . newcastle upon tyne: agenda publishing., order your copy now.

Corruption is known to be a complex problem, and understanding corruption in its many forms and global reach is the work of many years. This books tells the story of how corruption happens in practice, illustrated through detailed case studies of the many different types of corruption that span the globe.

Written by an expert team, each case study follows a tried and tested analytical approach to understand the different forms of corruption (bribery, political corruption, kleptocracy and corrupt capital) and how to tackle them.

With an emphasis on the harm such corruption causes, its victims, and where it has been tackled successfully, the authors draw lessons from the case studies to build a picture of the global threat that corruption poses and the responses that have been most effective.

You might also be interested in:

- Corruption and Governance MA

- Corruption and Governance MA (online)

- Our Research

Understanding corruption in the twenty-first century: towards a new constructivist research agenda

- Review Article

- Published: 12 January 2021

- Volume 19 , pages 82–102, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Sofia Wickberg 1

784 Accesses

3 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

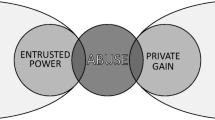

The search for a universally acceptable definition of corruption has been a central element of scholarship on corruption over the last decades, without it ever reaching a consensus in academic circles. Moreover, it is far from certain that citizens share the same understanding of what should be labelled as ‘corruption’ across time, space and social groups. This article traces the journey from the classical conception of corruption, centred around the notions of morals and decay, to the modern understanding of the term focussing on individual actions and practices. It provides an overview of the scholarly struggle over meaning-making and shows how the definition of corruption as the ‘abuse of public/entrusted power for private gain’ became dominant, as corruption was constructed as a global problem by international organizations. Lastly, it advocates for bringing back a more constructivist perspective on the study of corruption which takes the ambiguity and political dimensions of corruption seriously. The article suggests new avenues of research to understand corruption in the changing context of the twenty-first century.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Approaches to Corruption: a Synthesis of the Scholarship

Monica Prasad, Mariana Borges Martins da Silva & Andre Nickow

Corruption, Crisis, and Change: Use and Misuse of an Empty Signifier

The abuse of entrusted power for private gain: meaning, nature and theoretical evolution

Joseph Pozsgai-Alvarez

Author’s own translation.

Interestingly, in French, ‘corruption’ also refers to the sexual abuse of youth, reflecting the original polysemy.

Professor of History, Technische Universität Darmstadt (INTEX1). Interview, with author. November 17th 2016.

Abbott, K. 2001. Rule-making in the WTO: Lessons from the Ce of Bribery and Corruption. Journal of International Economic Law 4(2): 275–296.

Article Google Scholar

Affaire Penelope Fillon: Plusieurs centaines de manifestants à Paris “contre la corruption des élus” Europe 1, February 19th 2017. https://www.europe1.fr/societe/affaire-penelope-fillon-plusieurs-centaines-de-manifestants-a-paris-contre-la-corruption-des-elus-2982434 . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Alatas, H.S. 1968. The Sociology of Corruption: The Nature, Function, Causes and Prevention of Corruption . Singapore: D. Moore Press.

Google Scholar

Andreas, P., and K.M. Greenhill. 2010. Sex, Drugs, and Body counts: The Politics of Numbers in Global Crime and Conflict . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Atkinson, M.M., and M. Mancuso. 1985. Do we Need a Code of Conduct for Politicians? The Search for an Elite Political Culture of Corruption in Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science 18(3): 459–480.

Barnes, B. 2018. Women Politicians, Institutions, and Perceptions of Corruption. Comparative Political Studies 52(1): 134–167.

Bauhr, M., and N. Charron. 2020. Do Men and Women Perceive Corruption Differently? Gender Differences in Perception of Need and Greed Corruption. Politics and Governance 8(2): 92–102.

Becker G. S. 1974. Essays in the Economics of Crime and Punishment . New York: National Bureau of Economic Research: distributed by Columbia University Press.

Belouezzane, S. 2020. Affaire Fillon: Les Républicains «choqués»par les déclarations de l’ex-chef du Parquet national financier. Le Monde, June 22, 2020. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2020/06/22/les-republicains-choques-par-les-declarations-de-l-ex-cheffe-du-parquet-national-financier-sur-l-affaire-fillon_6043676_823448.html . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Berti, C., R. Bratu, and S. Wickberg. 2020. Corruption and the Media. In A Research Agenda for Studies of Corruption , ed. A. Mungiu-Pippidi and P. Heywood. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Best, J. 2008. Ambiguity, Uncertainty, and Risk: Rethinking Indeterminacy. International Political Sociology 2(4): 355–374.

Boccon-Gibod, T. Forthcoming. De la corruption des régimes à la confusion des intérêts: pour une histoire politique de la corruption. Revue française d’administration publique 145.

Bratu, R., and I. Kažoka. 2018. Metaphors of Corruption in the News Media Coverage of Seven European Countries. European Journal of Communication 33(1): 57–72.

Buchan, B., and L. Hill. 2014. An Intellectual History of Political Corruption . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Book Google Scholar

Bukovansky, M. 2006. The Hollowness of Anti-corruption Discourse. Review of International Political Economy 13(2): 181–209.

Centre national des ressources textuelles et lexicales. n.d. Corruption. https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/corruption . Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Clarke, J. 2006. What’s Culture Got to Do with It? Deconstructing Welfare, State and Nation . Working Paper n° 136-06, Centre for Cultural Research, University of Aarhus.

Clarke, N., W. Jennings, J. Moss, and G. Stoker. 2018. The Good Politician: Folk Theories, Political Interaction, and the Rise of Anti-politics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooley, A., and J. Snyder (eds.). 2015. Ranking the World: Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Craig, M. 2015. Post-2008 British Industrial Policy and Constructivist Political Economy: New Directions and New Tensions. New Political Economy 20(1): 107–125.

Eggers, V. 2018. Corruption, Accountability, and Gender: Do Female Politicians Face Higher Standards in Public Life? The Journal of politics 80(1): 321–326.

Engler, S. 2020. “Fighting Corruption” or “Fighting the Corrupt Elite”? Politicizing Corruption Within and Beyond the Populist Divide. Democratization 27(4): 643–661.

Europe 1. Affaire Penelope Fillon: Plusieurs centaines de manifestants à Paris “contre la corruption des élus”. February 19th 2017. Online, available at: https://www.europe1.fr/societe/affaire-penelope-fillon-plusieurs-centaines-de-manifestants-a-paris-contre-la-corruption-des-elus-2982434 Accessed 3 Jan 2021.

Fawcett, P., M. Flinders, C. Hay, and M. Wood (eds.). 2017. Anti-politics, Depoliticisation and Governance . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friedrich, C. 1972. The Pathology of Politics: Violence, Betrayal, Corruption, Secrecy and Propaganda . New York: Harper and Row.

Friedrich, C. 2002. Corruption Concepts in Historical Perspective. In Political Corruption: Concepts & Contexts . 3rd ed, ed. A.J. Heidenheimer and M. Johnston. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Gallie, W. B. 1956. IX.—Essentially Contested Concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 56(1): 167–198.

Gardiner, J.A. 1970. The Politics of Corruption. Organised Crime in an American City . New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Gebel, A.C. 2012. Human Nature and Morality in the Anti-corruption Discourse of Transparency International. Public Administration and Development 32: 109–128.

Génaux, M. 2002. Les mots de la corruption: la déviance publique dans les dictionnaires d’Ancien Régime. Histoire, économie et société 21(4): 513–530.

Génaux, M. 2004. Social Sciences and the Evolving Concept of Corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change 42(13): 13–24.

Gledhill, J. 2004. Corruption as the Mirror of the State in Latin America. In Between Morality and the Law: Corruption, Anthropology and Comparative Society , ed. I. Pardo. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Glynn, P., S.J. Kobrin, and M. Naìm. 1997. The Globalization of Corruption. In Corruption and the Global Economy , ed. K.A. Elliott. Washington, D.C: Institute of International Economics.

Graaf, G. 2007. Causes of Corruption: Towards a Contextual Theory of Corruption. Public administration quarterly 31(1/2): 39–86.

Gregg, B. 2011. Human Rights as Social Construction . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guilhot, N. 2005. The Democracy Makers: Human Rights and International Order . New York: Columbia University Press.

Habermas, J. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Harrison, E. 2006. Unpacking the Anti-corruption Agenda: Dilemmas for Anthropologists. Oxford Development Studies 34(1): 15–29.

Hay, C. 2007. Why We Hate Politics . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hay, C. 2016. Good in a Crisis: The Ontological Institutionalism of Social Constructivism. New Political Economy 21(6): 520–535.

Heeks, R., and H. Mathisen. 2012. Understanding Success and Failure of Anti-corruption Initiatives. Journal of Crime, Law and Social Change 58(5): 533–549.

Heidenheimer, A.J. 1970. Political Corruption: Readings in Comparative Analysis . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Heidenheimer, Arnold J., and Michael Johnston. 2002. Political Corruption: Concepts & Contexts . 3rd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Heidenheimer, A.J., M. Johnston, and V.T. Levine (eds.). 1989. Handbook of Corruption . New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Hellman, O. 2019. The Visual Politics of Corruption. Third World Quarterly 40(12): 2129–2152.

Heywood, P. 2015. Introduction Scale and Focus in the Study of Corruption. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption , ed. P. Heywood. Abingdon: Routledge.

Heywood, P. 2017. Rethinking Corruption. Hocus–Pocus, Locus and Focus. The Slavonic and East European Review 95(1): 21–48.

Heywood, P. 2019. 7—Paul Heywood on Which Questions to Ask to Gain New Insights into the Wicked Problem of Corruption. Kickback the Global Anticorruption Podcast . https://soundcloud.com/kickback-gap/7-episode-paul-heywood . Accessed 5 Nov 2020.

Heywood, P., and J. Rose. 2014. “Close But No Cigar”: The Measurement of Corruption. Journal of Public Policy 34(3): 507–529.

Hirsch, M. 2010. Pour en finir: avec les conflits d’intérêt . Paris: Stock.

Hirschman, A.O. 1997. The Passions and the Interests Political Arguments for Capitalism Before its Triumph . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hough, D. 2013. Corruption, Anti-corruption and Governance . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Huss, O. 2018. Corruption, Crisis, and Change: Use and Misuse of an Empty Signifier. In Crisis and Change in Post-Cold War Global Politics , ed. E. Resende, D. Budrytė, and D. Buhari-Gulmez. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Institutet mot mutor. n.d. Brottsbalken . Official website. https://www.institutetmotmutor.se/regelverk/det-svenska-regelverket/brottsbalken/ . Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

Jakobi, A.P. 2013. The Changing Global norm of Anti-corruption: From Bad Business to Bad Government. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 7(1): 243–264.

Jankowski, P. 2008. Shades of Indignation: Political Scandals in France, Past and Present . New York: Berghahn Books.

Johnston, M. 1996. The Search for Definitions: The Vitality of Politics and the Issue of Corruption. International Social Science Journal 48(149): 321–335.

Johnston, M. 2014. Corruption, Contention, and Reform . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnston, M. 2015. Reflection and Reassessment. The Emerging Agenda of Corruption Research. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption , ed. P. Heywood. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kalniņš, V. 2014. Anti-corruption Policies Revisited: D3.2.8. Background paper on Latvia. In Corruption and Governance Improvement in Global and Continental Perspectives , ed. A. Mungiu-Pippidi. Gothenburg: ANTICORRP.

Katzarova, E. 2019. The Social Construction of Global Corruption: from Utopia to Neoliberalism . Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelley, J.G. 2017. Scorecard Diplomacy Grading States to Influence Their Reputation and Behavior . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klein, N. 2014. This Changes Everything . New York City: Simon & Schuster.

Klitgaard, R. 1998. International Cooperation Against Corruption. Finance & Development 35(1): 3–6.

Knights, M. 2018. Explaining Away Corruption in Pre-modern Britain. Social Philosophy and Policy 35(2): 94–117.

Koechlin, L. 2013. Corruption as an Empty Signifier. Politics and Political Order in Africa . Leiden: Brill.

Krastev, I. 2004. Shifting Obsessions: Three Essays on the Politics of Anticorruption . New York: Central European University Press.

Kroeze, R. 2016. The Rediscovery of Corruption in Western Democracies. In Corruption and Governmental Legitimacy: A Twenty-First Century Perspective , ed. J. Mendilow and I. Peleg. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Kroeze, R., A. Vitória, and G. Geltner (eds.). 2018. Anticorruption in History: From Antiquity to the Modern era . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kubbe, I., and A. Engelbert (eds.). 2017. Corruption and Norms: Why Informal Rules Matter . London: Palgrave Macmillan Political Corruption and Governance Series.

Kubbe, I., and A. Varraich (eds.). 2019. Corruption and Informal Practices in the Middle East and North Africa . Abingdon, New York: Routledge Corruption and Anti-Corruption Studies.

Kurer, O. 2015. Definitions of Corruption. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption , ed. P. Heywood. Abingdon: Routledge.

Lascoumes, P. 2010. Favoritisme et corruption à la française Petits arrangements avec la probité . Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Ledeneva, Alena. 2008. Blat and Guanxi: Informal Practices in Russia and China. Comparative Studies in Society and History 50(1): 118–144.

Lefebvre, B. 2017. Rétro 2017. Fillon, une campagne placée sous le signe de la corruption. NPA Revolution permanente, December 28th 2017. https://www.revolutionpermanente.fr/Retro-2017-Fillon-une-campagne-placee-sous-le-signe-de-la-corruption . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Loli, M., and I. Kubbe. Forthcoming. Add Women and Stir? The Myths About the Gendered Dimension of Anti-corruption. European Journal of Gender Politics .

Marquette, H., and C. Peiffer. 2018. Grappling with the “Real Politics” of Systemic Corruption: Theoretical Debates Versus “Real-World” Functions. Governance 31: 499–514.

Mason, P. 2020. Twenty Years with Anticorruption. Part 4 Evidence on Anti-corruption—The Struggle to Understand What Works. U4 Practitioner Experience Note 2020:4 . Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Mazur, A.G. 2020. Feminist Approaches to Concepts and Conceptualization Toward Better Science and Policy. In Handbook of Feminist Philosophy of Science , ed. S. Crasnow and K. Intemann. Oxford: Routledge.

Mendilow, J., and E. Phélippeau (eds.). 2019. Political corruption in a world in transition . Wilmington, Delaware: Vernon Press.

Mény, Y. 2013. De la confusion des intérêts au conflit d’intérêts. Pouvoirs 147: 5–15.

Merry, S.E., K.E. Davis, and B. Kingsbury. 2015. The Quiet Power of Indicators: Measuring Governance, Corruption, and the Rule of Law . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Monier, F. 2016. La corruption, fille de la modernité politique? Revue internationale et stratégique 1(101): 63–75.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A., and P. Heywood (eds.). 2020. A Research Agenda for Studies of Corruption . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Naìm, M. 1995. The Corruption Eruption. The Brown Journal of World Affairs 2(2): 245–261.

Navot, D., and I. Beeri. 2018. The Public’s Conception of Political Corruption: A New Measurement Tool and Preliminary Findings. European Political Science 17(1): 1–18.

Nay, O. 2014. International Organisations and the Production of Hegemonic Knowledge: How the World Bank and the OECD Helped Invent the Fragile State Concept. Third World Quarterly 35(2): 210–231.

Nye, J. 1967. Corruption and Political Development: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. The American Political Science Review 61(2): 417–427.

OECD. 2017. Terrorism, Corruption and the Criminal Exploitation of Natural Resources . Paris: OECD Publishing.

Oren, I. 2002. Our Enemies and US: America’s Rivalries and the Making of Political Science . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Pearson, Z. 2013. An International Human Rights Approach to Corruption. In Corruption and Anti-Corruption , ed. P. Larmour and N. Wolanin. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press.

Pecnard, J. 2017. Présidentielle: rechute de complotisme aigu dans l’équipe Fillon. L’Express, March 23rd 2017. https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/politique/elections/presidentielle-rechute-de-complotisme-aigu-dans-l-equipe-fillon_1891811.html . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Persson, A., B. Rothstein, and J. Teorell. 2013. Why Anticorruption Reforms Fail: Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem. Governance 26(3): 449–471.

Peters, J.G., and S. Welch. 1978. Political Corruption in America: A Search for Definitions and a Theory, or If Political Corruption is in the Mainstream of American Politics Why is it Not in the Mainstream of American Politics Research? The American Political Science Review 72(3): 972–984.

Philp, M. 1997. Defining Political Corruption. Political Studies 45(3): 436–462.

Philp, M. 2015. The Definition of Political Corruption. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption , ed. P. Heywood. Oxford: Routledge.

Philp, M., and E. David-Barrett. 2015. Realism About Political Corruption. Annual Review of Political Science 18: 387–402.

Quah, Jon S.T. 2008. Curbing Corruption in India: An Impossible Dream? Asian Journal of Political Science 16(3): 240–259.

Rittel, H.W.J., and M.M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in the General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences 4: 155–169.

Rose, J. 2018. The Meaning of Corruption: Testing the Coherence and Adequacy of Corruption Definitions. Public Integrity 20(3): 220–233.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1978. The Economics of Corruption: A Study in Political Economy . New York: Academic Press.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1999. Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (ed.). 2006. International Handbook on the Economics of Corruption . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Rothstein, B., and D. Torsello. 2014. Bribery in Preindustrial Societies: Understanding the Universalism-Particularism Puzzle. Journal of Anthropological Research 70(2): 263–284.

Rothstein, B., and A. Varraich. 2017. Making Sense of Corruption . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roux, A. 2016. La corruption internationale: essai sur la répression d’un phénomène transnational . Ph.D. thesis defended on December 7th 2016 at the University of Aix-Marseille.

Schaffer, F.C. 2016. Elucidating Social Science Concepts: An Interpretivist Guide . New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Sineau, M. 2010. Chapitre 6/Genre et corruption: des perceptions différenciées. In Favoritisme et corruption à la française. Petits arrangements avec la probité , ed. P. Lascoumes, 187–198. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Chapter Google Scholar

Soroos, M.S. 1990. A Theoretical Framework for Global Policy Studies. International Political Science Review 11(3): 309–322.

Sousa, L., P. Larmour, and B. Hindess. 2009. Governments, NGOs and Anti-corruption: The New Integrity Warriors . New York, NY: Routledge.

Steingrüber, S., M. Kirya, D. Jackson, and S. Mullard. 2020. Corruption in the Time of COVID-19: A Double-Threat for Low Income Countries. U4 Brief 2020:6 . Bergen: Michelsen Institute.

Stone, D. 2013. Knowledge Actors and Transnational Governance . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tänzler D., Maras, K. 2012. The Social Construction of Corruption in Europe . Farnham Burlington, Vt: Ashgate.

Thompson, D.F. 1993. Mediated Corruption: The Case of the Keating Five. American Political Science Review 8(2): 369–381.

Torgler, V. 2010. Gender and Public Attitudes Toward Corruption and Tax Evasion. Contemporary Economic Policy 28(4): 554–568.

Transparency International. n.d. How Do You Define Corruption? Official website. https://www.transparency.org/what-is-corruption#define . Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Transparency International Sverige. n.d. Vad är korruption? Official website. https://www.transparency.se/korruption . Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

United Nations. 2010. Travaux Préparatoires of the negotiations for the elaboration of the United Nations Convention against Corruption . Vienna: United Nations Office.

United Nations. 2020. Covid - 19: l’ONU appelle à combattre la corruption qui prend de nouvelles forms. ONU Info. https://news.un.org/fr/story/2020/10/1079882 . Accessed 10 Nov 2020.

Vlassis, D. 2004. The United Nations Convention Against Corruption: Origins and Negotiation Process. Resource Material Series 66: 126–131.

Voltolini, B., M. Natorski, and C. Hay. 2020. Introduction: The Politicisation of Permanent Crisis in Europe. Journal of European Integration 42(5): 609–624.

Wang, H., and J.N. Rosenau. 2001. Transparency International and Corruption as an Issue of Global Governance. Global Governance 7(1): 25–49.

Warren, M.E. 2015. The Meaning of Corruption in Democracies. In Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption , ed. P. Heywood. Oxford: Routledge.

Wedel, J.R. 2012. Rethinking Corruption in an Age of Ambiguity. The Annual Review of Law and Social Science 8(1): 453–498.

Wickberg, S. 2018. Corruption. In Dictionnaire d’économie politique , ed. A. Smith and C. Hay. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Wickberg, S. 2020. Global Instruments, Local Practices. Understanding the ‘Divergent Convergence’ of Anti - corruption Policy in Europe . Ph.D. Thesis, defended on July 2d 2020. Paris: Sciences Po.

Williams, R. (ed.). 2000. The Politics of Corruption 1, Explaining Corruption . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

World Bank. 1997. Helping Countries Combat Corruption The Role of the World Bank . Poverty Reduction and Economic Management. Washington DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2020. Combating Corruption. Official Website. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance/brief/anti-corruption . Accessed 10 Nov 2020.

Zaretysky, R. 2017. Why is France so Corrupt? Foreign Policy, February 1st 2017. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/02/01/why-is-france-so-corrupt-fillon-macron-le-pen/ . Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sciences Po, Centre d’études européennes et de politique comparée, Paris, France

Sofia Wickberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sofia Wickberg .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wickberg, S. Understanding corruption in the twenty-first century: towards a new constructivist research agenda. Fr Polit 19 , 82–102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00144-4

Download citation

Accepted : 18 December 2020

Published : 12 January 2021

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00144-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Political concept

- Constructivism

- Political analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Corruption: Unethical practices of corporate executives- A case study of Tyco International

Related Papers

Melba G. Sanchez

SSRN Electronic Journal

Tara Shawver

Cary Cooper

Cindy Schipani

Frank S . Perri JD, CPA, CFE

ASCENT International Conference Proceedings - Accounting and Business Management (IJABM), 11-12 April 2013

Muhammad Said

Applied Economics

Liz David-Barrett

We investigate why top-down directives aimed at eradicating corruption are ineffective at altering on-the-ground practices for organizations that have adopted industry-wide “gold standards” to prevent bribery and corruption. Using interview and focus group data collected from leading multinational pharmaceutical firms, we unearth antecedents contributing to organizations’ systemic failure to embed their anticorruption policies in business practice. We identify two tensions that contribute to this disconnect: a culture clash between global and local norms, especially in emerging markets and a similar disconnect between the compliance and commercial functions. To overcome these tensions, we suggest that organizations are likely to find it easier to implement a no gifts policy if they cease to rely on local agents embedded in local norms and that there needs to be strong evidence of board- level commitment to antibribery programs, innovative ways of incentivizing compliant behavior, and a fundamental rethinking of organizations’ business model and remuneration practices.

Workplace Ethics, Small Businesses, and Good Economic Times: A Predictive Study

Lorraine Ginader

In 2007 – 2010 the United States experienced the worst economic crisis since the 1930’s Great Depression. At the core of the Great Recession was the financial crisis also coined the sub-prime mortgage crisis whose causation is directly linked to an aweless financial industry paradigm. The Great Recession followed a decade of exposed corporate corruptions, significantly diminishing public trust. Due to the Great Recession approximately thirty million United States citizens were out of work. Unemployment for many individuals exceeded nine-months, depleting savings and causing extreme hardships on US households. The depth and broad sweep of fraud and ethical professional negligence found in the wake of the crisis was seen as contributing to a wide spread internalization of public distrust and an unwilling tolerance for unethical conduct. When faced with significant financial stressors and high unemployment people are more incline to tolerate unethical workplace conduct as a coping mechanism in order to keep their jobs. The recession and financial crisis adverse effects were more severe in small businesses due to small business dependency on bank credit, at a time when small business lending decline of $116 billion or almost 18%. This online, mixed-method, nationally distributed, survey will investigate the phenomenon of unethical tolerance within small business workforces post-Great Recession and contribute to the literature on crisis management and organizational leadership.

Catholic University Journal

Mario P Urbieta

Regional integration is a process that, despite of not evolve as it would have expected in most scenarios, it has been strengthening around the world in last decades. In South America, notwithstanding that probably the fact that the Mercosur has not developed as it would have expected in the improvement of political and commercial integration of its members, is still the most developed regional integration process in Paraguay

RELATED PAPERS

Daniela Szymańska

Pedro Sequeira

Cristian Cristea

Erwin A J M Bente

Hubungi WA 0813 3096 1051 Magang Jurusan Multimedia SMK Ampelgading Malang

Fatkhan Akbar

Australian Journal of Business and Management Research

Maxwell Hsu

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences

Niken Paramita

Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms

Romanian Economic Business Review

Mihai BERINDE

Revista de Ciências Humanas

Cibele da Silveira

Journal of Perinatal Medicine

Ritsuko Pooh

Revista de Ensino de Ciências e Matemática

Ben Sebitosi

Revista da Faculdade Mineira de Direito

Cristiane Cabral

yazid Saif alkosa

Didier Fouarge

Meir Benayahu ז״ל

Ismael Garcia

Neurosurgery

Leandro Flores

Diagnostics

Rogier Hopstaken

Estudios Avanzados

carmen gloria fuentealba pérez

Emerging Trends of Advanced Composite Materials in Structural Applications

Shuvendu Narayan Patel

Frontiers in Earth Science

Mario Gimenez

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 What Can We Learn about Corruption from Historical Case Studies?

Mark Knights is Professor of History at the University of Warwick where he has directed its Early Modern and Eighteenth Century Centre. He has published many works on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain, and his book Trust and Distrust: Corruption in Office in Britain and its Empire, 1600-1850 will be published by Oxford University Press.

- Published: 14 July 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The chapter shows how a historical approach can offer a productive and useful dataset and tools to understand corruption and anticorruption. Since corruption has existed across time and space, and is multifaceted, involving politics, economics, law, administration, social, and cultural attitudes, it can best be studied in a multidisciplinary way that includes the study of the past as well as the present. A historical approach offers ways of thinking about change and continuity, and hence also about how and why reform processes occur and are successful. Historical case studies can test and challenge social science models but also offer different, more qualitative, evidence that can help us to reconstruct the mentalities of those who refused to accept that their behavior constituted “corruption,” as well as the motives of those bringing the prosecution or making allegations. Historical sources, often offering multiple perspectives of different participants, can also enable us to form a more holistic view of corruption scandals and of the important role of public discussion in shaping quality of government.

This chapter will argue that history can offer something important to the study of corruption and quality of government—and of course can in turn learn from other disciplines. This may seem a surprising claim when quantitative studies, based on large datasets from opinion surveys, such as the various indices that are routinely subjected to mathematically informed interrogation, are simply not available for the past. But what may seem like an obstacle to cross-disciplinary conversation may actually be an advantage, since the historian is freed from sometimes dubious datasets, correlations, and abstractions; is able to test some of the models and conclusions put forward in other disciplines; and can offer vital contextual analysis. Indeed, history offers a mass, and many different types, of data—press reports, legal cases, legislative debates, diaries, correspondence, and governmental inquiries, to name but a few—that are seldom explored by social scientists because they do not easily lend themselves to treatment by some of their methodologies and perhaps because the past is conceived of as “not relevant” to the present. But historians have studied quality of government and corruption, albeit in a somewhat patchy way, and there are always echoes and resonances of their themes across time as well as space ( Aylmer 1980 ; Burns and Innes 2007 ; Dirks 2006 ; Geltner, Kroeze, and Vitoria 2017 ; Graham 2015 ; Harling 1996 ; Harling and Mandler 1993 ; Hellmuth 1999 ; Hurstfield 1967 , 1973 ; Kramnick 1994 ; Kreike and Jordan 2004 ; Marshall 1976 ; Peck 1990 ). If we accept that concerns about good government, and corruption in particular, are not just a “modern” phenomenon, history offers a huge array of data to help us explore which reform processes worked, which didn’t and why. History offers the scholar and the policymaker another important and useful tool. So this chapter is a plea for a multidisciplinary approach that includes history far more than at present, though it is not an argument for the superiority of that discipline over others.

The discussion that follows seeks to set out how a historical approach based on the collection and analysis of empirical, archival data can be useful. The focus will be on corruption as a quality of government issue, though quality of government more generally generated a vast and useful pre-modern literature, as numerous treatises and pamphlets were written as advice and counsel to rulers, primarily to monarchs but also to assemblies, republican regimes, and the wider public. Political theory considers works by Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and others but these writers were part of a much larger public discussion about good kingship and good government that penetrated far down the social scale, not least because the Reformation in church government, as well as rebellions and revolutions in Britain and across Europe, and participation in both local government and imperial ventures, required many to take a position about whether government was working well, needed reform, or had to be overturned. Analysis of this extensive public debate would merit a book in its own right, so the subtheme here of corruption will be used to illustrate some broader themes.

The chapter’s brief is to explain the methodology of the historian— how we can learn about corruption through historical case studies and why we should embrace them—rather than the conclusions of what particular lessons history might suggest, though some of the latter will nevertheless surface and more are available in a freely downloadable report written for Transparency International ( Knights 2016a ). Both the latter and subsequent observations in this chapter are informed by my work on corruption and office-holding in Britain between 1600 and 1850 (Knights, forthcoming, 2021b). During that time there were some very significant changes in the way that corruption was conceptualized, how it proliferated, and how it was reformed (for the wider evolution of the concept see Rothstein and Varraich 2017 , chapter 3 ). Corruption shifted from what was primarily a religious concept to one concerned with politics, economic, and the state; opportunities for corruption expanded as the state and empire expanded; and reforms abolished the sale of office, curbed gift-giving and embezzlement, defined what constituted public money, and introduced an actionable concept of “abuse of trust.” In other words the “early modern” period, as it is known, was a key one in the evolution of about the evolution of corruption and anticorruption and therefore worthy of study for what it can tell us about the development of good government.

The Importance of Case Studies and Context

History is a broad discipline with a range of different methodologies, ideologies, and concepts (for overviews of history and its methods see Tosh 2008 , 2015 , 2018 ; Jordanova 2006 , 2012 ). Nevertheless, most historians use archival material that is often generated by institutions or individuals, enabling historians to marshal evidence and create or test theories through compilations of case studies. Some in the social sciences may find this approach problematic and overly concerned with a particular moment in the past at the expense of broader conclusions. Case studies can indeed be unhelpful when the love of telling a particular story or the detail of reconstructing the past obscures the wider point that such evidence can illuminate or when the compilation of evidence becomes an end in itself, with little analytical framework to guide the reader or draw out more general conclusions; but the latter is simply poor history rather than a reason to avoid history altogether. A good case study will, in fact, highlight the importance of context for understanding the challenges facing government, something that anticorruption studies are gradually accepting as more and more important ( Heywood and Johnson 2017 ; Heywood 2018 ; Johnston 2006 , 2012 ; Nicoletti 2017 ). Indeed, there has been something of a “historical turn” to the study of corruption, a recognition that the past has important things to tell us about what has or has not worked, why they did or did not succeed, and what conditions needed to prevail for reform to be successful. Different legal, economic, religious, and moral as well as political and social cultures all shape government and attitudes to corruption. It matters, for example, if a country has a tradition of fiduciary law: the legal concept and practice of a “trust” by which a principal entrusts property or powers to an agent to act as a “trustee.” A trust thus carries legal duties and responsibilities for which the agent can be held accountable but also much more discretion than a contract. Without that notion or framework, the idea of “entrusted power” is unlikely to take firm root. Britain and Spain, which developed legal histories along different lines, thus had different anticorruption trajectories.

An effective case study—or even a microhistory—can also explore the role and beliefs of individuals within the macro data often studied by social scientists, adding an important layer of analysis that examines the behavior of agents within the game being played ( Ginzburg 1993 ; Center for Microhistorical Research. http://www.microhistory.org/ ). By drilling down into detail, a case study’s particular spatial or temporal focus can help us better understand the factors driving or preventing reform; and global and transnational case studies (for example, the study of transnational corporations, such as the European East India Companies) can explore processes of interaction and points of comparison. Cumulatively, case studies provide data from which generalizations are possible even if they are contextually colored.

If social scientists appreciate the value of the notion of path dependency, they will necessarily have to engage with the history that helped to shape it ( Hellmann 2017 ). And that requires a recognition of the role of contingency and local circumstance. Britain’s history of pre-modern anticorruption was thus fundamentally shaped by its religious reformation; parliamentary tradition; acquisition of empire; legal and print culture; and its process of socioeconomic transformation. But none of these factors was a fixed determinant. Each of them was vigorously contested and hence fluid: history suggests that there were often multiple paths that might have been taken and that the path pursued reflected a complex of contingent and contested factors. Venality of office, for example, was removed in Britain by a protracted legal and legislative process; but in France it took a relatively swift revolution. Path dependency does not mean historical inevitability, since both the direction and nature of the pathways were often bitterly fought over—the direction of the reformation, the triumph of parliamentary sovereignty, the freedom of the press, an increasingly independent judiciary, and economic liberalism were all deeply controversial and disputed. So the particular context matters. And this applies to peoples as well as institutions and structures. People are themselves conditioned by their historical context. And the choices made at one time shaped the mentalities of the next generation(s) because individuals are partly conditioned by their historical environment: “different historical circumstances make different kinds of actors” ( Little 2017 , 324). That means that there is no one single, universal, timeless right path but rather a variety of different strategies that have worked (or not) in different contexts. If the problems of government were the same over time and space, universal laws and practices would surely have been developed by now to prevent it.

A historical understanding of change thus challenges “one-size-fits-all” solutions. A good deal of research and international policy in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries assumed that corruption is universal and that universal remedies are therefore appropriate. A historical view, which involves reconstructing different ways of thinking about and tackling corruption in the past, challenges this and suggests that corruption and anticorruption evolved according to local contexts, and that these contingent factors should be taken into account by modern policymakers if they want to be successful.

The reconstruction of the past requires imagination—and imagining ourselves back into past lives and contexts helps us appreciate that although basic emotional responses of fear, love, hatred, and greed have always existed, their expression and form have always been constructs, the result of pressures from society, culture, religion, law, the economy, and the state (for the history of emotions see Plamper 2017 ; Reddy 2001 ; Rosenwein 2006 ). The universal, rationally calculating, self-interested actor beloved by some economists would be hard to find in history: such a view of human nature is itself a construct. Understanding the different mindsets of the past should thus be of interest to policymakers because they challenge current assumptions.

Change and Continuity

One obvious area that history can help with is change and continuity over time. A “long view” can correct any assumption that corruption and anticorruption are, as has sometimes been claimed, very recent phenomena and intrinsically connected either with “modernity” ( Engels 2017 ) or with the wave of NGO policies developed from the late 1990s onwards. Corruption and anticorruption have existed throughout history, even if the types and even concept of corruption have themselves changed over time ( Geltner, Kroeze, and Vitoria 2017 ; Buchan and Hill 2014 ). One way of charting this evolution is through historical discourse analysis ( Brett 2002 ; de Bolla 2013 ; Pocock 1987 ; Skinner 2002 ). Increasing quantities of historical, printed material have been digitized and are now searchable in interesting (though not always unproblematic) ways. History can thus help chart the evolution of the terms and concepts in which we are all interested and suggest that although the discourse of “corruption” does similar work across time—giving a moral and often political charge to accusations that something has decayed from its original or ideal purity—its specificity was given to it by its context. What was once described or conceptualized as corrupt in the past (charging interest on money, for example, which was known as usury) are now no longer seen as such or hold much less sway, in many countries at least ( Fontaine 2014 ; Hawkes 2010 ; Nelson 1969 ).

Another important aspect of the historical study of change and continuity has to do with causality and processes of reform and innovation—essential features of any anticorruption strategy or policy for the improvement of government. Given that there is now a general awareness that modern corruption policies may not have been as swiftly effective as their designers hoped, understanding the speed and nature of change is clearly central to current policy formation. By looking at the past we can suggest how, and in what conditions, reform processes came about and flourished; and, more generally, how transformations of government have worked. Historians, together with social scientists and political thinkers such as Weber and Marx, have developed a large range of theories to help explain different types of change and reform processes (for overviews see Kramer and Maza 2002 ; Little 2000 ; 2007 ). Indeed, the word “reform” is itself one with a deep history, a contraction of the word “reformation,” the term applied to the major changes brought about by the birth and development of the protestant church when it broke away in the sixteenth century ( Innes 2007 ). It is therefore instructive to reflect briefly on how historians have explained and characterized the fundamental shift of views, practices and institutions during the Reformation—not least since “corruption” was a term most frequently applied in the pre-modern British context to religious belief to denote original sin or sins of the body and mind and because corruption has always had a moral connotation. Historians have had, of course, more than one interpretation of the Reformation: it used to be seen as a rapid process, dictated from above, but the growing consensus is now that although there were some early adopters it was generally a slow process, burning from below and taking several centuries to complete—not least because belief was embedded in social and cultural practices that shaped mind-sets and often proved stubbornly resistant to reform ( Clark 2000 ; Haigh 1990 ; Ryrie 2013 ; Shagan 2003 ; Tyacke 1998 , 2007 ). So a study of the Reformation will caution against thinking that a major set of reforms can ever be achieved simply by dictat or legislative frameworks, necessary though those may be: changing cultural values takes time. There was a “big bang” of legislative change in the 1530s, both in terms of religion and administration, but this took far longer to be implemented at the local, parish level; and historians increasingly talk of a “long reformation” that, for some, lasted from the early sixteenth until the eighteenth century.

Thinking about how big shifts in institutional and individual culture come about is thus an essential part of the historian’s remit but is also the task of those seeking to escape the collective action problem of a prevalent culture of corruption. So another interesting model to “think with” is provided by historical sociologist/philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn’s ideas about the “Scientific Revolution” ( Kuhn 2012 ). He argued that a fundamental change in basic concepts and practices of scientific discipline could constitute a paradigmatic shift. This occurred when practitioners encountered anomalies that could no longer be explained by the universally accepted paradigm, which was not just a way of understanding science but a complete worldview in which that understanding operated: “science” was not a single strand of activity but one embedded in much larger worldviews. When enough anomalies had been accumulated, the study of science was thrown into a crisis in which new ideas were tried out—though this process involved a series of protracted attacks before a new paradigm prevailed. The term “revolution” may imply quick and sudden change, but in reality the process was more protracted, involved social and intellectual change, and was messy. Kuhn’s ideas are now contested—the history of science has generally seen apparently-conflicting ideas as far more able to coexist than Kuhn allowed ( Toulmin 1972 ; Iliffe 2017 )—but the question of what leads to paradigmatic change is still a relevant one. In the context of quality of government, we might talk of a paradigmatic shift in the notion of office-holding, for example, during the period 1600–1850 in Britain. This involved a series of scandals and contests that cumulatively chipped away at the old paradigm of office as either a piece of personal property or as something responsible only to the monarch, making that paradigm ultimately untenable ( Johnston 1991 ; Knights forthcoming 2021b). During this process there were rival and contested versions of what should be the right paradigm. Rather than a single factor or set of policies explaining all change, a complex of factors was at play. And even once a paradigmatic shift had been achieved, remnants of the old paradigm still prevailed: in Britain, administrative reform did not remove some of the social attributes of corruption—such as securing jobs for friends and cronies or for members of a similar class and background. Even Charles Trevelyan, the man most associated with civil service reform in mid-nineteenth century Britain and who hated patronage as a fundamentally corrupting phenomenon, argued that his plans for a more professional and efficient civil service were designed to bolster the strength of the educated social elite. In a private memorandum he asked,

Who are so successful in carrying off the prizes at competing scholar ships, fellowships, &c. as the most expensively educated young men? Almost invariably, the sons of gentlemen, or those who by force of cultivation, good-training and good society have acquired the feelings and habits of gentlemen. The tendency of the measure will, I am confident, be decidedly aristocratic ( Hughes 1949 , 72).

History can thus highlight how and why some things remain stubbornly resistant to change (even whilst other elements are reformed), and governmental powers embedded in social hierarchies would be one of them. Another might be imperial exploitation: some (though not all) historians argue that anticorruption may actually have served to legitimize colonial rule ( Dirks 2006 ; Epstein 2012 ).