IOE Writing Centre

- Writing a Critical Review

Writing a Critique

A critique (or critical review) is not to be mistaken for a literature review. A 'critical review', or 'critique', is a complete type of text (or genre), discussing one particular article or book in detail. In some instances, you may be asked to write a critique of two or three articles (e.g. a comparative critical review). In contrast, a 'literature review', which also needs to be 'critical', is a part of a larger type of text, such as a chapter of your dissertation.

Most importantly: Read your article / book as many times as possible, as this will make the critical review much easier.

1. Read and take notes 2. Organising your writing 3. Summary 4. Evaluation 5. Linguistic features of a critical review 6. Summary language 7. Evaluation language 8. Conclusion language 9. Example extracts from a critical review 10. Further resources

Read and Take Notes

To improve your reading confidence and efficiency, visit our pages on reading.

Further reading: Read Confidently

After you are familiar with the text, make notes on some of the following questions. Choose the questions which seem suitable:

- What kind of article is it (for example does it present data or does it present purely theoretical arguments)?

- What is the main area under discussion?

- What are the main findings?

- What are the stated limitations?

- Where does the author's data and evidence come from? Are they appropriate / sufficient?

- What are the main issues raised by the author?

- What questions are raised?

- How well are these questions addressed?

- What are the major points/interpretations made by the author in terms of the issues raised?

- Is the text balanced? Is it fair / biased?

- Does the author contradict herself?

- How does all this relate to other literature on this topic?

- How does all this relate to your own experience, ideas and views?

- What else has this author written? Do these build / complement this text?

- (Optional) Has anyone else reviewed this article? What did they say? Do I agree with them?

^ Back to top

Organising your writing

You first need to summarise the text that you have read. One reason to summarise the text is that the reader may not have read the text. In your summary, you will

- focus on points within the article that you think are interesting

- summarise the author(s) main ideas or argument

- explain how these ideas / argument have been constructed. (For example, is the author basing her arguments on data that they have collected? Are the main ideas / argument purely theoretical?)

In your summary you might answer the following questions: Why is this topic important? Where can this text be located? For example, does it address policy studies? What other prominent authors also write about this?

Evaluation is the most important part in a critical review.

Use the literature to support your views. You may also use your knowledge of conducting research, and your own experience. Evaluation can be explicit or implicit.

Explicit evaluation

Explicit evaluation involves stating directly (explicitly) how you intend to evaluate the text. e.g. "I will review this article by focusing on the following questions. First, I will examine the extent to which the authors contribute to current thought on Second Language Acquisition (SLA) pedagogy. After that, I will analyse whether the authors' propositions are feasible within overseas SLA classrooms."

Implicit evaluation

Implicit evaluation is less direct. The following section on Linguistic Features of Writing a Critical Review contains language that evaluates the text. A difficult part of evaluation of a published text (and a professional author) is how to do this as a student. There is nothing wrong with making your position as a student explicit and incorporating it into your evaluation. Examples of how you might do this can be found in the section on Linguistic Features of Writing a Critical Review. You need to remember to locate and analyse the author's argument when you are writing your critical review. For example, you need to locate the authors' view of classroom pedagogy as presented in the book / article and not present a critique of views of classroom pedagogy in general.

Linguistic features of a critical review

The following examples come from published critical reviews. Some of them have been adapted for student use.

Summary language

- This article / book is divided into two / three parts. First...

- While the title might suggest...

- The tone appears to be...

- Title is the first / second volume in the series Title, edited by...The books / articles in this series address...

- The second / third claim is based on...

- The author challenges the notion that...

- The author tries to find a more middle ground / make more modest claims...

- The article / book begins with a short historical overview of...

- Numerous authors have recently suggested that...(see Author, Year; Author, Year). Author would also be once such author. With his / her argument that...

- To refer to title as a...is not to say that it is...

- This book / article is aimed at... This intended readership...

- The author's book / article examines the...To do this, the author first...

- The author develops / suggests a theoretical / pedagogical model to…

- This book / article positions itself firmly within the field of...

- The author in a series of subtle arguments, indicates that he / she...

- The argument is therefore...

- The author asks "..."

- With a purely critical / postmodern take on...

- Topic, as the author points out, can be viewed as...

- In this recent contribution to the field of...this British author...

- As a leading author in the field of...

- This book / article nicely contributes to the field of...and complements other work by this author...

- The second / third part of...provides / questions / asks the reader...

- Title is intended to encourage students / researchers to...

- The approach taken by the author provides the opportunity to examine...in a qualitative / quantitative research framework that nicely complements...

- The author notes / claims that state support / a focus on pedagogy / the adoption of...remains vital if...

- According to Author (Year) teaching towards examinations is not as effective as it is in other areas of the curriculum. This is because, as Author (Year) claims that examinations have undue status within the curriculum.

- According to Author (Year)…is not as effective in some areas of the curriculum / syllabus as others. Therefore the author believes that this is a reason for some school's…

Evaluation language

- This argument is not entirely convincing, as...furthermore it commodifies / rationalises the...

- Over the last five / ten years the view of...has increasingly been viewed as 'complicated' (see Author, Year; Author, Year).

- However, through trying to integrate...with...the author...

- There are difficulties with such a position.

- Inevitably, several crucial questions are left unanswered / glossed over by this insightful / timely / interesting / stimulating book / article. Why should...

- It might have been more relevant for the author to have written this book / article as...

- This article / book is not without disappointment from those who would view...as...

- This chosen framework enlightens / clouds...

- This analysis intends to be...but falls a little short as...

- The authors rightly conclude that if...

- A detailed, well-written and rigorous account of...

- As a Korean student I feel that this article / book very clearly illustrates...

- The beginning of...provides an informative overview into...

- The tables / figures do little to help / greatly help the reader...

- The reaction by scholars who take a...approach might not be so favourable (e.g. Author, Year).

- This explanation has a few weaknesses that other researchers have pointed out (see Author, Year; Author, Year). The first is...

- On the other hand, the author wisely suggests / proposes that...By combining these two dimensions...

- The author's brief introduction to...may leave the intended reader confused as it fails to properly...

- Despite my inability to...I was greatly interested in...

- Even where this reader / I disagree(s), the author's effort to...

- The author thus combines...with...to argue...which seems quite improbable for a number of reasons. First...

- Perhaps this aversion to...would explain the author's reluctance to...

- As a second language student from ...I find it slightly ironic that such an anglo-centric view is...

- The reader is rewarded with...

- Less convincing is the broad-sweeping generalisation that...

- There is no denying the author's subject knowledge nor his / her...

- The author's prose is dense and littered with unnecessary jargon...

- The author's critique of...might seem harsh but is well supported within the literature (see Author, Year; Author, Year; Author, Year). Aligning herself with the author, Author (Year) states that...

- As it stands, the central focus of Title is well / poorly supported by its empirical findings...

- Given the hesitation to generalise to...the limitation of...does not seem problematic...

- For instance, the term...is never properly defined and the reader left to guess as to whether...

- Furthermore, to label...as...inadvertently misguides...

- In addition, this research proves to be timely / especially significant to... as recent government policy / proposals has / have been enacted to...

- On this well researched / documented basis the author emphasises / proposes that...

- Nonetheless, other research / scholarship / data tend to counter / contradict this possible trend / assumption...(see Author, Year; Author, Year).

- Without entering into detail of the..., it should be stated that Title should be read by...others will see little value in...

- As experimental conditions were not used in the study the word 'significant' misleads the reader.

- The article / book becomes repetitious in its assertion that...

- The thread of the author's argument becomes lost in an overuse of empirical data...

- Almost every argument presented in the final section is largely derivative, providing little to say about...

- She / he does not seem to take into consideration; however, that there are fundamental differences in the conditions of…

- As Author (Year) points out, however, it seems to be necessary to look at…

- This suggest that having low…does not necessarily indicate that…is ineffective.

- Therefore, the suggestion made by Author (Year)…is difficult to support.

- When considering all the data presented…it is not clear that the low scores of some students, indeed, reflects…

Conclusion language

- Overall this article / book is an analytical look at...which within the field of...is often overlooked.

- Despite its problems, Title offers valuable theoretical insights / interesting examples / a contribution to pedagogy and a starting point for students / researchers of...with an interest in...

- This detailed and rigorously argued...

- This first / second volume / book / article by...with an interest in...is highly informative...

Example extracts from a critical review

Writing critically.

If you have been told your writing is not critical enough, it probably means that your writing treats the knowledge claims as if they are true, well supported, and applicable in the context you are writing about. This may not always be the case.

In these two examples, the extracts refer to the same section of text. In each example, the section that refers to a source has been highlighted in bold. The note below the example then explains how the writer has used the source material.

There is a strong positive effect on students, both educationally and emotionally, when the instructors try to learn to say students' names without making pronunciation errors (Kiang, 2004).

Use of source material in example a:

This is a simple paraphrase with no critical comment. It looks like the writer agrees with Kiang. (This is not a good example for critical writing, as the writer has not made any critical comment).

Kiang (2004) gives various examples to support his claim that "the positive emotional and educational impact on students is clear" (p.210) when instructors try to pronounce students' names in the correct way. He quotes one student, Nguyet, as saying that he "felt surprised and happy" (p.211) when the tutor said his name clearly . The emotional effect claimed by Kiang is illustrated in quotes such as these, although the educational impact is supported more indirectly through the chapter. Overall, he provides more examples of students being negatively affected by incorrect pronunciation, and it is difficult to find examples within the text of a positive educational impact as such.

Use of source material in example b:

The writer describes Kiang's (2004) claim and the examples which he uses to try to support it. The writer then comments that the examples do not seem balanced and may not be enough to support the claims fully. This is a better example of writing which expresses criticality.

^Back to top

Further resources

You may also be interested in our page on criticality, which covers criticality in general, and includes more critical reading questions.

Further reading: Read and Write Critically

We recommend that you do not search for other university guidelines on critical reviews. This is because the expectations may be different at other institutions. Ask your tutor for more guidance or examples if you have further questions.

IOE Writing Centre Online

Self-access resources from the Academic Writing Centre at the UCL Institute of Education.

Anonymous Suggestions Box

Information for Staff

Academic Writing Centre

Academic Writing Centre, UCL Institute of Education [email protected] Twitter: @AWC_IOE Skype: awc.ioe

How to Critique an Article: Mastering the Article Evaluation Process

Did you know that approximately 4.6 billion pieces of content are produced every day? From news articles and blog posts to scholarly papers and social media updates, the digital landscape is flooded with information at an unprecedented rate. In this age of information overload, honing the skill of articles critique has never been more crucial. Whether you're seeking to bolster your academic prowess, stay well-informed, or improve your writing, mastering the art of article critique is a powerful tool to navigate the vast sea of information and discern the pearls of wisdom.

How to Critique an Article: Short Description

In this article, we will equip you with valuable tips and techniques to become an insightful evaluator of written content. We present a real-life article critique example to guide your learning process and help you develop your unique critique style. Additionally, we explore the key differences between critiquing scientific articles and journals. Whether you're a student, researcher, or avid reader, this guide will empower you to navigate the vast ocean of information with confidence and discernment. Still, have questions? Don't worry! We've got you covered with a helpful FAQ section to address any lingering doubts. Get ready to unleash your analytical prowess and uncover the true potential of every article that comes your way!

What Is an Article Critique: Understanding The Power of Evaluation

An article critique is a valuable skill that involves carefully analyzing and evaluating a written piece, such as a journal article, blog post, or news article. It goes beyond mere summarization and delves into the deeper layers of the content, examining its strengths, weaknesses, and overall effectiveness. Think of it as an engaging conversation with the author, where you provide constructive feedback and insights.

For instance, let's consider a scenario where you're critiquing a research paper on climate change. Instead of simply summarizing the findings, you would scrutinize the methodology, data interpretation, and potential biases, offering thoughtful observations to enrich the discussion. Through the process of writing an article critique, you develop a critical eye, honing your ability to appreciate well-crafted work while also identifying areas for improvement.

In the following sections, our ' write my paper ' experts will uncover valuable tips on and key points on how to write a stellar critique, so let's explore more!

Unveiling the Key Aims of Writing an Article Critique

Writing an article critique serves several essential purposes that go beyond a simple review or summary. When engaging in the art of critique, as when you learn how to write a review article , you embark on a journey of in-depth analysis, sharpening your critical thinking skills and contributing to the academic and intellectual discourse. Primarily, an article critique allows you to:

%20(3).webp)

- Evaluate the Content : By critiquing an article, you delve into its content, structure, and arguments, assessing its credibility and relevance.

- Strengthen Your Critical Thinking : This practice hones your ability to identify strengths and weaknesses in written works, fostering a deeper understanding of complex topics and critical evaluation skills.

- Engage in Scholarly Dialogue : Your critique contributes to the ongoing academic conversation, offering valuable insights and thoughtful observations to the existing body of knowledge.

- Enhance Writing Skills : By analyzing and providing feedback, you develop a keen eye for effective writing techniques, benefiting your own writing endeavors.

- Promote Continuous Learning : Through the writing process, you continually refine your analytical abilities, becoming an avid and astute learner in the pursuit of knowledge.

How to Critique an Article: Steps to Follow

The process of crafting an article critique may seem overwhelming, especially when dealing with intricate academic writing. However, fear not, for it is more straightforward than it appears! To excel in this art, all you require is a clear starting point and the skill to align your critique with the complexities of the content. To help you on your journey, follow these 3 simple steps and unlock the potential to provide insightful evaluations:

%20(4).webp)

Step 1: Read the Article

The first and most crucial step when wondering how to do an article critique is to thoroughly read and absorb its content. As you delve into the written piece, consider these valuable tips from our custom essay writer to make your reading process more effective:

- Take Notes : Keep a notebook or digital document handy while reading. Jot down key points, noteworthy arguments, and any questions or observations that arise.

- Annotate the Text : Underline or highlight significant passages, quotes, or sections that stand out to you. Use different colors to differentiate between positive aspects and areas that may need improvement.

- Consider the Author's Purpose : Reflect on the author's main critical point and the intended audience. Much like an explanatory essay , evaluate how effectively the article conveys its message to the target readership.

Now, let's say you are writing an article critique on climate change. While reading, you come across a compelling quote from a renowned environmental scientist highlighting the urgency of addressing global warming. By taking notes and underlining this impactful quote, you can later incorporate it into your critique as evidence of the article's effectiveness in conveying the severity of the issue.

Step 2: Take Notes/ Make sketches

Once you've thoroughly read the article, it's time to capture your thoughts and observations by taking comprehensive notes or creating sketches. This step plays a crucial role in organizing your critique and ensuring you don't miss any critical points. Here's how to make the most out of this process:

- Highlight Key Arguments : Identify the main arguments presented by the author and highlight them in your notes. This will help you focus on the core ideas that shape the article.

- Record Supporting Evidence : Take note of any evidence, examples, or data the author uses to support their arguments. Assess the credibility and effectiveness of this evidence in bolstering their claims.

- Examine Structure and Flow : Pay attention to the article's structure and how each section flows into the next. Analyze how well the author transitions between ideas and whether the organization enhances or hinders the reader's understanding.

- Create Visual Aids : If you're a visual learner, consider using sketches or diagrams to map out the article's key points and their relationships. Visual representations can aid in better grasping the content's structure and complexities.

Step 3: Format Your Paper

Once you've gathered your notes and insights, it's time to give structure to your article critique. Proper formatting ensures your critique is organized, coherent, and easy to follow. Here are essential tips for formatting an article critique effectively:

- Introduction : Begin with a clear and engaging introduction that provides context for the article you are critiquing. Include the article's title, author's name, publication details, and a brief overview of the main theme or thesis.

- Thesis Statement : Present a strong and concise thesis statement that conveys your overall assessment of the article. Your thesis should reflect whether you found the article compelling, convincing, or in need of improvement.

- Body Paragraphs : Organize your critique into well-structured body paragraphs. Each paragraph should address a specific point or aspect of the article, supported by evidence and examples from your notes.

- Use Evidence : Back up your critique with evidence from the article itself. Quote relevant passages, cite examples, and reference data to strengthen your analysis and demonstrate your understanding of the article's content.

- Conclusion : Conclude your critique by summarizing your main points and reiterating your overall evaluation. Avoid introducing new arguments in the conclusion and instead provide a concise and compelling closing statement.

- Citation Style : If required, adhere to the specific citation style guidelines (e.g., APA, MLA) for in-text citations and the reference list. Properly crediting the original article and any additional sources you use in your critique is essential.

How to Critique a Journal Article: Mastering the Steps

So, you've been assigned the task of critiquing a journal article, and not sure where to start? Worry not, as we've prepared a comprehensive guide with different steps to help you navigate this process with confidence. Journal articles are esteemed sources of scholarly knowledge, and effectively critiquing them requires a systematic approach. Let's dive into the steps to expertly evaluate and analyze a journal article:

Step 1: Understanding the Research Context

Begin by familiarizing yourself with the broader research context in which the journal article is situated. Learn about the field, the topic's significance, and any previous relevant research. This foundational knowledge will provide a valuable backdrop for your journal article critique example.

Step 2: Evaluating the Article's Structure

Assess the article's overall structure and organization. Examine how the introduction sets the stage for the research and how the discussion flows logically from the methodology and results. A well-structured article enhances readability and comprehension.

Step 3: Analyzing the Research Methodology

Dive into the research methodology section, which outlines the approach used to gather and analyze data. Scrutinize the study's design, data collection methods, sample size, and any potential biases or limitations. Understanding the research process will enable you to gauge the article's reliability.

Step 4: Assessing the Data and Results

Examine the presentation of data and results in the article. Are the findings clear and effectively communicated? Look for any discrepancies between the data presented and the interpretations made by the authors.

Step 5: Analyzing the Discussion and Conclusions

Evaluate the discussion section, where the authors interpret their findings and place them in the broader context. Assess the soundness of their conclusions, considering whether they are adequately supported by the data.

Step 6: Considering Ethical Considerations

Reflect on any ethical considerations raised by the research. Assess whether the study respects the rights and privacy of participants and adheres to ethical guidelines.

Step 7: Identifying Strengths and Weaknesses

Identify the article's strengths, such as well-designed experiments, comprehensive, relevant literature reviews, or innovative approaches. Also, pinpoint any weaknesses, like gaps in the research, unclear explanations, or insufficient evidence.

Step 8: Offering Constructive Feedback

Provide constructive feedback to the authors, highlighting both positive aspects and areas for improvement for future research. Suggest ways to enhance the research methods, data analysis, or discussion to bolster its overall quality.

Step 9: Presenting Your Critique

Organize your critique into a well-structured paper, starting with an introduction that outlines the article's context and purpose. Develop a clear and focused thesis statement that conveys your assessment. Support your points with evidence from the article and other credible sources.

By following these steps on how to critique a journal article, you'll be well-equipped to craft a thoughtful and insightful piece, contributing to the scholarly discourse in your field of study!

Got an Article that Needs Some Serious Critiquing?

Don't sweat it! Our critique maestros are armed with wit, wisdom, and a dash of magic to whip that piece into shape.

An Article Critique: Journal Vs. Research

In the realm of academic writing, the terms 'journal article' and 'research paper' are often used interchangeably, which can lead to confusion about their differences. Understanding the distinctions between critiquing a research article and a journal piece is essential. Let's delve into the key characteristics that set apart a journal article from a research paper and explore how the critique process may differ for each:

Publication Scope:

- Journal Article: Presents focused and concise research findings or new insights within a specific subject area.

- Research Paper: Explores a broader range of topics and can cover extensive research on a particular subject.

Format and Structure:

- Journal Article: Follows a standardized format with sections such as abstract, introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Research Paper: May not adhere to a specific format and allows flexibility in organizing content based on the research scope.

Depth of Analysis:

- Journal Article: Provides a more concise and targeted analysis of the research topic or findings.

- Research Paper: Offers a more comprehensive and in-depth analysis, often including extensive literature reviews and data analyses.

- Journal Article: Typically shorter in length, ranging from a few pages to around 10-15 pages.

- Research Paper: Tends to be longer, spanning from 20 to several hundred pages, depending on the research complexity.

Publication Type:

- Journal Article: Published in academic journals after undergoing rigorous peer review.

- Research Paper: May be published as a standalone work or as part of a thesis, dissertation, or academic report.

- Journal Article: Targeted at academics, researchers, and professionals within the specific field of study.

- Research Paper: Can cater to a broader audience, including students, researchers, policymakers, and the general public.

- Journal Article: Primarily aimed at sharing new research findings, contributing to academic discourse, and advancing knowledge in the field.

- Research Paper: Focuses on comprehensive exploration and analysis of a research topic, aiming to make a substantial contribution to the body of knowledge.

Appreciating these differences becomes paramount when engaging in the critique of these two forms of scholarly publications, as they each demand a unique approach and thoughtful consideration of their distinctive attributes. And if you find yourself desiring a flawlessly crafted research article critique example, entrusting the task to professional writers is always an excellent option – you can easily order essay that meets your needs.

Article Critique Example

Our collection of essay samples offers a comprehensive and practical illustration of the critique process, granting you access to valuable insights.

Tips on How to Critique an Article

Critiquing an article requires a keen eye, critical thinking, and a thoughtful approach to evaluating its content. To enhance your article critique skills and provide insightful analyses, consider incorporating these five original and practical tips into your process:

1. Analyze the Author's Bias : Be mindful of potential biases in the article, whether they are political, cultural, or personal. Consider how these biases may influence the author's perspective and the presentation of information. Evaluating the presence of bias enables you to discern the objectivity and credibility of the article's arguments.

2. Examine the Supporting Evidence : Scrutinize the quality and relevance of the evidence used to support the article's claims. Look for well-researched data, credible sources, and up-to-date statistics. Assess how effectively the author integrates evidence to build a compelling case for their arguments.

3. Consider the Audience's Perspective : Put yourself in the shoes of the intended audience and assess how well the article communicates its ideas. Consider whether the language, tone, and level of complexity are appropriate for the target readership. A well-tailored article is more likely to engage and resonate with its audience.

4. Investigate the Research Methodology : If the article involves research or empirical data, delve into the methodology used to gather and analyze the information. Evaluate the soundness of the study design, sample size, and data collection methods. Understanding the research process adds depth to your critique.

5. Discuss the Implications and Application : Consider the broader implications of the article's findings or arguments. Discuss how the insights presented in the article could impact the field of study or have practical applications in real-world scenarios. Identifying the potential consequences of the article's content strengthens your critique's depth and relevance.

Wrapping Up

In a nutshell, article critique is an essential skill that helps us grow as critical thinkers and active participants in academia. Embrace the opportunity to analyze and offer constructive feedback, contributing to a brighter future of knowledge and understanding. Remember, each critique is a chance to engage with new ideas and expand our horizons. So, keep honing your critique skills and enjoy the journey of discovery in the world of academic exploration!

Tired of Ordinary Critiques?

Brace yourself for an extraordinary experience! Our critique geniuses are on standby, ready to unleash their extraordinary skills on your article!

What Steps Need to Be Taken in Writing an Article Critique?

What is the recommended length for an article critique, related articles.

.webp)

- All eBooks & Audiobooks

- Academic eBook Collection

- Home Grown eBook Collection

- Off-Campus Access

- Literature Resource Center

- Opposing Viewpoints

- ProQuest Central

- Course Guides

- Citing Sources

- Library Research

- Websites by Topic

- Book-a-Librarian

- Research Tutorials

- Use the Catalog

- Use Databases

- Use Films on Demand

- Use Home Grown eBooks

- Use NC LIVE

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Make an Appointment

- Writing Tools

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing Center

Service Alert

Article Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing an article SUMMARY

- Writing an article REVIEW

Writing an article CRITIQUE

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- About RCC Library

Text: 336-308-8801

Email: [email protected]

Call: 336-633-0204

Schedule: Book-a-Librarian

Like us on Facebook

Links on this guide may go to external web sites not connected with Randolph Community College. Their inclusion is not an endorsement by Randolph Community College and the College is not responsible for the accuracy of their content or the security of their site.

A critique asks you to evaluate an article and the author’s argument. You will need to look critically at what the author is claiming, evaluate the research methods, and look for possible problems with, or applications of, the researcher’s claims.

Introduction

Give an overview of the author’s main points and how the author supports those points. Explain what the author found and describe the process they used to arrive at this conclusion.

Body Paragraphs

Interpret the information from the article:

- Does the author review previous studies? Is current and relevant research used?

- What type of research was used – empirical studies, anecdotal material, or personal observations?

- Was the sample too small to generalize from?

- Was the participant group lacking in diversity (race, gender, age, education, socioeconomic status, etc.)

- For instance, volunteers gathered at a health food store might have different attitudes about nutrition than the population at large.

- How useful does this work seem to you? How does the author suggest the findings could be applied and how do you believe they could be applied?

- How could the study have been improved in your opinion?

- Does the author appear to have any biases (related to gender, race, class, or politics)?

- Is the writing clear and easy to follow? Does the author’s tone add to or detract from the article?

- How useful are the visuals (such as tables, charts, maps, photographs) included, if any? How do they help to illustrate the argument? Are they confusing or hard to read?

- What further research might be conducted on this subject?

Try to synthesize the pieces of your critique to emphasize your own main points about the author’s work, relating the researcher’s work to your own knowledge or to topics being discussed in your course.

From the Center for Academic Excellence (opens in a new window), University of Saint Joseph Connecticut

Additional Resources

All links open in a new window.

Writing an Article Critique (from The University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center)

How to Critique an Article (from Essaypro.com)

How to Write an Article Critique (from EliteEditing.com.au)

- << Previous: Writing an article REVIEW

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://libguides.randolph.edu/summaries

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

How to Critique a Research Article

Published: 01 October 2023

Let's briefly examine some basic pointers on how to perform a literature review.

If you've managed to get your hands on peer-reviewed articles, then you may wonder why it is necessary for you to perform your own article critique. Surely the article will be of good quality if it has made it through the peer-review process?

Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Publication bias can occur when editors only accept manuscripts that have a bearing on the direction of their own research, or reject manuscripts with negative findings. Additionally, not all peer reviewers have expert knowledge on certain subject matters , which can introduce bias and sometimes a conflict of interest.

Performing your own critical analysis of an article allows you to consider its value to you and to your workplace.

Critical evaluation is defined as a systematic way of considering the truthfulness of a piece of research, its results and how relevant and applicable they are.

How to Critique

It can be a little overwhelming trying to critique an article when you're not sure where to start. Considering the article under the following headings may be of some use:

Title of Study/Research

You may be a better judge of this after reading the article, but the title should succinctly reflect the content of the work, stimulating readers' interest.

Three to six keywords that encapsulate the main topics of the research will have been drawn from the body of the article.

Introduction

This should include:

- Evidence of a literature review that is relevant and recent, critically appraising other works rather than merely describing them

- Background information on the study to orientate the reader to the problem

- Hypothesis or aims of the study

- Rationale for the study that justifies its need, i.e. to explore an un-investigated gap in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Similar to a recipe, the description of materials and methods will allow others to replicate the study elsewhere if needed. It should both contain and justify the exact specifications of selection criteria, sample size, response rate and any statistics used. This will demonstrate how the study is capable of achieving its aims. Things to consider in this section are:

- What sort of sampling technique and size was used?

- What proportion of the eligible sample participated? (e.g. '553 responded to a survey sent to 750 medical technologists'

- Were all eligible groups sampled? (e.g. was the survey sent only in English?)

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

- Were there threats to the reliability and validity of the study, and were these controlled for?

- Were there any obvious biases?

- If a trial was undertaken, was it randomised, case-controlled, blinded or double-blinded?

Results should be statistically analysed and presented in a way that an average reader of the journal will understand. Graphs and tables should be clear and promote clarity of the text. Consider whether:

- There were any major omissions in the results, which could indicate bias

- Percentages have been used to disguise small sample sizes

- The data generated is consistent with the data collected.

Negative results are just as relevant as research that produces positive results (but, as mentioned previously, may be omitted in publication due to editorial bias).

This should show insight into the meaning and significance of the research findings. It should not introduce any new material but should address how the aims of the study have been met. The discussion should use previous research work and theoretical concepts as the context in which the new study can be interpreted. Any limitations of the study, including bias, should be clearly presented. You will need to evaluate whether the author has clearly interpreted the results of the study, or whether the results could be interpreted another way.

Conclusions

These should be clearly stated and will only be valid if the study was reliable, valid and used a representative sample size. There may also be recommendations for further research.

These should be relevant to the study, be up-to-date, and should provide a comprehensive list of citations within the text.

Final Thoughts

Undertaking a critique of a research article may seem challenging at first, but will help you to evaluate whether the article has relevance to your own practice and workplace. Reading a single article can act as a springboard into researching the topic more widely, and aids in ensuring your nursing practice remains current and is supported by existing literature.

- Marshall, G 2005, ‘Critiquing a Research Article’, Radiography , vol. 11, no. 1, viewed 2 October 2023, https://www.radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(04)00119-1/fulltext

Sarah Vogel View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

A guide for critique of research articles

Following is the list of criteria to evaluate (critique) a research article. Please note that you should first summarize the paper and then evaluate different parts of it.

Most of the evaluation section should be devoted to evaluation of internal validity of the conclusions. Please add at the end a section entitled ''changes in the design/procedures if I want to replicate this study." Attach a copy of the original article to your paper.

Click here to see a an example (this is how you start) of a research critique.

Click here to see the original article.

The following list is a guide for you to organize your evaluation. It is recommended to organize your evaluation in this order. This is a long list of questions. You don’t have to address all questions. However, you should address highlighted questions . Some questions may not be relevant to your article.

Introduction

1. Is there a statement of the problem?

2. Is the problem “researchable”? That is, can it be investigated through the collection and analysis of data?

3. Is background information on the problem presented?

4. Is the educational significance of the problem discussed?

5. Does the problem statement indicate the variables of interest and the specific relationship between those variables which are investigated? When necessary, are variables directly or operationally defined?

Review of Related Literature

1. Is the review comprehensive?

2. Are all cited references relevant to the problem under investigation?

3. Are most of the sources primary, i.e., are there only a few or no secondary sources?

4. Have the references been critically analyzed and the results of various studies compared and contrasted, i.e., is the review more than a series of abstracts or annotations?

5. Does the review conclude with a brief summary of the literature and its implications for the problem investigated?

6. Do the implications discussed form an empirical or theoretical rationale for the hypotheses which follow?

1. Are specific questions to be answered listed or specific hypotheses to be tested stated?

2. Does each hypothesis state an expected relationship or difference?

3. If necessary, are variables directly or operationally defined?

4. Is each hypothesis testable?

Method Subjects

1. Are the size and major characteristics of the population studied described?

2. If a sample was selected, is the method of selecting the sample clearly described?

3. Is the method of sample selection described one that is likely to result in a representative, unbiased sample?

4. Did the researcher avoid the use of volunteers?

5. Are the size and major characteristics of the sample described?

6. Does the sample size meet the suggested guideline for minimum sample size appropriate for the method of research represented?

Instruments

1. Is the rationale given for the selection of the instruments (or measurements) used?

2. Is each instrument described in terms of purpose and content?

3. Are the instruments appropriate for measuring the intended variables?

4. Is evidence presented that indicates that each instrument is appropriate for the sample under study?

5. Is instrument validity discussed and coefficients given if appropriate?

6. Is reliability discussed in terms of type and size of reliability coefficients?

7. If appropriate, are subtest reliabilities given?

8. If an instrument was developed specifically for the study, are the procedures involved in its development and validation described?

9. If an instrument was developed specifically for the study, are administration, scoring or tabulating, and interpretation procedures fully described?

Design and Procedure

1. Is the design appropriate for answering the questions or testing the hypotheses of the study?

2. Are the procedures described in sufficient detail to permit them to be replicated by another researcher?

3. If a pilot study was conducted, are its execution and results described as well as its impact on the subsequent study?

4. Are the control procedures described?

5. Did the researcher discuss or account for any potentially confounding variables that he or she was unable to control for?

1. Are appropriate descriptive or inferential statistics presented?

2. Was the probability level, α, at which the results of the tests of significance were evaluated,

specified in advance of the data analyses?

3. If parametric tests were used, is there evidence that the researcher avoided violating the

required assumptions for parametric tests?

4. Are the tests of significance described appropriate, given the hypotheses and design of the

study?

5. Was every hypothesis tested?

6. Are the tests of significance interpreted using the appropriate degrees of freedom?

7. Are the results clearly presented?

8. Are the tables and figures (if any) well organized and easy to understand?

9. Are the data in each table and figure described in the text?

Discussion (Conclusions and Recommendation)

1. Is each result discussed in terms of the original hypothesis to which it relates?

2. Is each result discussed in terms of its agreement or disagreement with previous results

obtained by other researchers in other studies?

3. Are generalizations consistent with the results?

4. Are the possible effects of uncontrolled variables on the results discussed?

5. Are theoretical and practical implications of the findings discussed?

6. Are recommendations for future action made?

7. Are the suggestions for future action based on practical significance or on statistical

significance only, i.e., has the author avoided confusing practical and statistical

significance?

8. Are recommendations for future research made?

Additional general questions to be answered in your critique.

1. What is (are) the research question(s) (or hypothesis)?

2. Describe the sample used in this study.

3. Describe the reliability and validity of all the instruments used.

4. What type of research is this? Explain.

5. How was the data analyzed?

6. What is (are) the major finding(s)?

Writing a Critique

- About this Guide

- What Is a Critique?

- Getting Started

- Components of a Critique Essay

Examples of Critique

You can find critiques in DragonQuest by including the term "critique" in your search. Here are a few examples of articles that provide critiques:

Babb, A. M., Knudsen, D. C., & Robeson, S. M. (2019). A critique of the objective function utilized in calculating the Thrifty Food Plan. PLoS

ONE , 14 (7), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219895

Greene-Woods, A. (2020). The Efficacy of Signing Standard English for Increasing Reading Achievement: An Article Critique. American Annals of

the Deaf , 165 (4), 456–460.

Pochron, R. Scott. (2008). Article Review: Advanced Change Theory Revisited: An Article Critique. Integral Review , 4 (2), 125–132.

Schmidt, N. (2020). Beyond the Personal: The Systemic Critique of German Graphic Medicine. Seminar: A Journal of Germanic Studies , 56 (3–4).

- << Previous: Components of a Critique Essay

- Next: Get Help >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2023 10:46 AM

- URL: https://library.tiffin.edu/critique

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can Med Educ J

- v.12(3); 2021 Jun

Writing, reading, and critiquing reviews

Écrire, lire et revue critique, douglas archibald.

1 University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada;

Maria Athina Martimianakis

2 University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Why reviews matter

What do all authors of the CMEJ have in common? For that matter what do all health professions education scholars have in common? We all engage with literature. When you have an idea or question the first thing you do is find out what has been published on the topic of interest. Literature reviews are foundational to any study. They describe what is known about given topic and lead us to identify a knowledge gap to study. All reviews require authors to be able accurately summarize, synthesize, interpret and even critique the research literature. 1 , 2 In fact, for this editorial we have had to review the literature on reviews . Knowledge and evidence are expanding in our field of health professions education at an ever increasing rate and so to help keep pace, well written reviews are essential. Though reviews may be difficult to write, they will always be read. In this editorial we survey the various forms review articles can take. As well we want to provide authors and reviewers at CMEJ with some guidance and resources to be able write and/or review a review article.

What are the types of reviews conducted in Health Professions Education?

Health professions education attracts scholars from across disciplines and professions. For this reason, there are numerous ways to conduct reviews and it is important to familiarize oneself with these different forms to be able to effectively situate your work and write a compelling rationale for choosing your review methodology. 1 , 2 To do this, authors must contend with an ever-increasing lexicon of review type articles. In 2009 Grant and colleagues conducted a typology of reviews to aid readers makes sense of the different review types, listing fourteen different ways of conducting reviews, not all of which are mutually exclusive. 3 Interestingly, in their typology they did not include narrative reviews which are often used by authors in health professions education. In Table 1 , we offer a short description of three common types of review articles submitted to CMEJ.

Three common types of review articles submitted to CMEJ

More recently, authors such as Greenhalgh 4 have drawn attention to the perceived hierarchy of systematic reviews over scoping and narrative reviews. Like Greenhalgh, 4 we argue that systematic reviews are not to be seen as the gold standard of all reviews. Instead, it is important to align the method of review to what the authors hope to achieve, and pursue the review rigorously, according to the tenets of the chosen review type. Sometimes it is helpful to read part of the literature on your topic before deciding on a methodology for organizing and assessing its usefulness. Importantly, whether you are conducting a review or reading reviews, appreciating the differences between different types of reviews can also help you weigh the author’s interpretation of their findings.

In the next section we summarize some general tips for conducting successful reviews.

How to write and review a review article

In 2016 David Cook wrote an editorial for Medical Education on tips for a great review article. 13 These tips are excellent suggestions for all types of articles you are considering to submit to the CMEJ. First, start with a clear question: focused or more general depending on the type of review you are conducting. Systematic reviews tend to address very focused questions often summarizing the evidence of your topic. Other types of reviews tend to have broader questions and are more exploratory in nature.

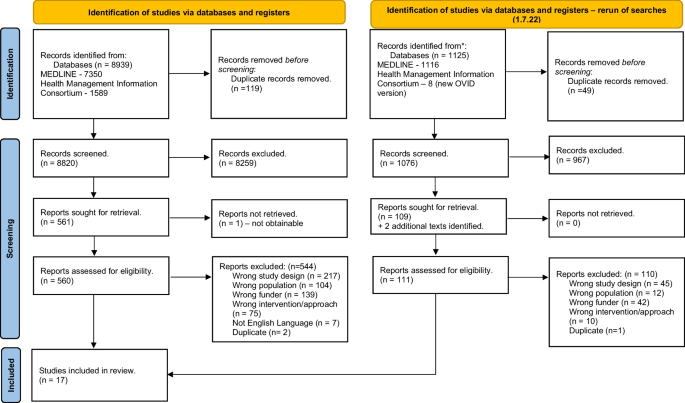

Following your question, choose an approach and plan your methods to match your question…just like you would for a research study. Fortunately, there are guidelines for many types of reviews. As Cook points out the most important consideration is to be sure that the methods you follow lead to a defensible answer to your review question. To help you prepare for a defensible answer there are many guides available. For systematic reviews consult PRISMA guidelines ; 13 for scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR ; 14 and SANRA 15 for narrative reviews. It is also important to explain to readers why you have chosen to conduct a review. You may be introducing a new way for addressing an old problem, drawing links across literatures, filling in gaps in our knowledge about a phenomenon or educational practice. Cook refers to this as setting the stage. Linking back to the literature is important. In systematic reviews for example, you must be clear in explaining how your review builds on existing literature and previous reviews. This is your opportunity to be critical. What are the gaps and limitations of previous reviews? So, how will your systematic review resolve the shortcomings of previous work? In other types of reviews, such as narrative reviews, its less about filling a specific knowledge gap, and more about generating new research topic areas, exposing blind spots in our thinking, or making creative new links across issues. Whatever, type of review paper you are working on, the next steps are ones that can be applied to any scholarly writing. Be clear and offer insight. What is your main message? A review is more than just listing studies or referencing literature on your topic. Lead your readers to a convincing message. Provide commentary and interpretation for the studies in your review that will help you to inform your conclusions. For systematic reviews, Cook’s final tip is most likely the most important– report completely. You need to explain all your methods and report enough detail that readers can verify the main findings of each study you review. The most common reasons CMEJ reviewers recommend to decline a review article is because authors do not follow these last tips. In these instances authors do not provide the readers with enough detail to substantiate their interpretations or the message is not clear. Our recommendation for writing a great review is to ensure you have followed the previous tips and to have colleagues read over your paper to ensure you have provided a clear, detailed description and interpretation.

Finally, we leave you with some resources to guide your review writing. 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 16 , 17 We look forward to seeing your future work. One thing is certain, a better appreciation of what different reviews provide to the field will contribute to more purposeful exploration of the literature and better manuscript writing in general.

In this issue we present many interesting and worthwhile papers, two of which are, in fact, reviews.

Major Contributions

A chance for reform: the environmental impact of travel for general surgery residency interviews by Fung et al. 18 estimated the CO 2 emissions associated with traveling for residency position interviews. Due to the high emissions levels (mean 1.82 tonnes per applicant), they called for the consideration of alternative options such as videoconference interviews.

Understanding community family medicine preceptors’ involvement in educational scholarship: perceptions, influencing factors and promising areas for action by Ward and team 19 identified barriers, enablers, and opportunities to grow educational scholarship at community-based teaching sites. They discovered a growing interest in educational scholarship among community-based family medicine preceptors and hope the identification of successful processes will be beneficial for other community-based Family Medicine preceptors.

Exploring the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: an international cross-sectional study of medical learners by Allison Brown and team 20 studied the impact of COVID-19 on medical learners around the world. There were different concerns depending on the levels of training, such as residents’ concerns with career timeline compared to trainees’ concerns with the quality of learning. Overall, the learners negatively perceived the disruption at all levels and geographic regions.

The impact of local health professions education grants: is it worth the investment? by Susan Humphrey-Murto and co-authors 21 considered factors that lead to the publication of studies supported by local medical education grants. They identified several factors associated with publication success, including previous oral or poster presentations. They hope their results will be valuable for Canadian centres with local grant programs.

Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical learner wellness: a needs assessment for the development of learner wellness interventions by Stephana Cherak and team 22 studied learner-wellness in various training environments disrupted by the pandemic. They reported a negative impact on learner wellness at all stages of training. Their results can benefit the development of future wellness interventions.

Program directors’ reflections on national policy change in medical education: insights on decision-making, accreditation, and the CanMEDS framework by Dore, Bogie, et al. 23 invited program directors to reflect on the introduction of the CanMEDS framework into Canadian postgraduate medical education programs. Their survey revealed that while program directors (PDs) recognized the necessity of the accreditation process, they did not feel they had a voice when the change occurred. The authors concluded that collaborations with PDs would lead to more successful outcomes.

Experiential learning, collaboration and reflection: key ingredients in longitudinal faculty development by Laura Farrell and team 24 stressed several elements for effective longitudinal faculty development (LFD) initiatives. They found that participants benefited from a supportive and collaborative environment while trying to learn a new skill or concept.

Brief Reports

The effect of COVID-19 on medical students’ education and wellbeing: a cross-sectional survey by Stephanie Thibaudeau and team 25 assessed the impact of COVID-19 on medical students. They reported an overall perceived negative impact, including increased depressive symptoms, increased anxiety, and reduced quality of education.

In Do PGY-1 residents in Emergency Medicine have enough experiences in resuscitations and other clinical procedures to meet the requirements of a Competence by Design curriculum? Meshkat and co-authors 26 recorded the number of adult medical resuscitations and clinical procedures completed by PGY1 Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in Emergency Medicine residents to compare them to the Competence by Design requirements. Their study underscored the importance of monitoring collection against pre-set targets. They concluded that residency program curricula should be regularly reviewed to allow for adequate clinical experiences.

Rehearsal simulation for antenatal consults by Anita Cheng and team 27 studied whether rehearsal simulation for antenatal consults helped residents prepare for difficult conversations with parents expecting complications with their baby before birth. They found that while rehearsal simulation improved residents’ confidence and communication techniques, it did not prepare them for unexpected parent responses.

Review Papers and Meta-Analyses

Peer support programs in the fields of medicine and nursing: a systematic search and narrative review by Haykal and co-authors 28 described and evaluated peer support programs in the medical field published in the literature. They found numerous diverse programs and concluded that including a variety of delivery methods to meet the needs of all participants is a key aspect for future peer-support initiatives.

Towards competency-based medical education in addictions psychiatry: a systematic review by Bahji et al. 6 identified addiction interventions to build competency for psychiatry residents and fellows. They found that current psychiatry entrustable professional activities need to be better identified and evaluated to ensure sustained competence in addictions.

Six ways to get a grip on leveraging the expertise of Instructional Design and Technology professionals by Chen and Kleinheksel 29 provided ways to improve technology implementation by clarifying the role that Instructional Design and Technology professionals can play in technology initiatives and technology-enhanced learning. They concluded that a strong collaboration is to the benefit of both the learners and their future patients.

In his article, Seven ways to get a grip on running a successful promotions process, 30 Simon Field provided guidelines for maximizing opportunities for successful promotion experiences. His seven tips included creating a rubric for both self-assessment of likeliness of success and adjudication by the committee.

Six ways to get a grip on your first health education leadership role by Stasiuk and Scott 31 provided tips for considering a health education leadership position. They advised readers to be intentional and methodical in accepting or rejecting positions.

Re-examining the value proposition for Competency-Based Medical Education by Dagnone and team 32 described the excitement and controversy surrounding the implementation of competency-based medical education (CBME) by Canadian postgraduate training programs. They proposed observing which elements of CBME had a positive impact on various outcomes.

You Should Try This

In their work, Interprofessional culinary education workshops at the University of Saskatchewan, Lieffers et al. 33 described the implementation of interprofessional culinary education workshops that were designed to provide health professions students with an experiential and cooperative learning experience while learning about important topics in nutrition. They reported an enthusiastic response and cooperation among students from different health professional programs.

In their article, Physiotherapist-led musculoskeletal education: an innovative approach to teach medical students musculoskeletal assessment techniques, Boulila and team 34 described the implementation of physiotherapist-led workshops, whether the workshops increased medical students’ musculoskeletal knowledge, and if they increased confidence in assessment techniques.

Instagram as a virtual art display for medical students by Karly Pippitt and team 35 used social media as a platform for showcasing artwork done by first-year medical students. They described this shift to online learning due to COVID-19. Using Instagram was cost-saving and widely accessible. They intend to continue with both online and in-person displays in the future.

Adapting clinical skills volunteer patient recruitment and retention during COVID-19 by Nazerali-Maitland et al. 36 proposed a SLIM-COVID framework as a solution to the problem of dwindling volunteer patients due to COVID-19. Their framework is intended to provide actionable solutions to recruit and engage volunteers in a challenging environment.

In Quick Response codes for virtual learner evaluation of teaching and attendance monitoring, Roxana Mo and co-authors 37 used Quick Response (QR) codes to monitor attendance and obtain evaluations for virtual teaching sessions. They found QR codes valuable for quick and simple feedback that could be used for many educational applications.

In Creation and implementation of the Ottawa Handbook of Emergency Medicine Kaitlin Endres and team 38 described the creation of a handbook they made as an academic resource for medical students as they shift to clerkship. It includes relevant content encountered in Emergency Medicine. While they intended it for medical students, they also see its value for nurses, paramedics, and other medical professionals.

Commentary and Opinions

The alarming situation of medical student mental health by D’Eon and team 39 appealed to medical education leaders to respond to the high numbers of mental health concerns among medical students. They urged leaders to address the underlying problems, such as the excessive demands of the curriculum.

In the shadows: medical student clinical observerships and career exploration in the face of COVID-19 by Law and co-authors 40 offered potential solutions to replace in-person shadowing that has been disrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They hope the alternatives such as virtual shadowing will close the gap in learning caused by the pandemic.

Letters to the Editor

Canadian Federation of Medical Students' response to “ The alarming situation of medical student mental health” King et al. 41 on behalf of the Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMS) responded to the commentary by D’Eon and team 39 on medical students' mental health. King called upon the medical education community to join the CFMS in its commitment to improving medical student wellbeing.

Re: “Development of a medical education podcast in obstetrics and gynecology” 42 was written by Kirubarajan in response to the article by Development of a medical education podcast in obstetrics and gynecology by Black and team. 43 Kirubarajan applauded the development of the podcast to meet a need in medical education, and suggested potential future topics such as interventions to prevent learner burnout.

Response to “First year medical student experiences with a clinical skills seminar emphasizing sexual and gender minority population complexity” by Kumar and Hassan 44 acknowledged the previously published article by Biro et al. 45 that explored limitations in medical training for the LGBTQ2S community. However, Kumar and Hassen advocated for further progress and reform for medical training to address the health requirements for sexual and gender minorities.

In her letter, Journey to the unknown: road closed!, 46 Rosemary Pawliuk responded to the article, Journey into the unknown: considering the international medical graduate perspective on the road to Canadian residency during the COVID-19 pandemic, by Gutman et al. 47 Pawliuk agreed that international medical students (IMGs) do not have adequate formal representation when it comes to residency training decisions. Therefore, Pawliuk challenged health organizations to make changes to give a voice in decision-making to the organizations representing IMGs.

In Connections, 48 Sara Guzman created a digital painting to portray her approach to learning. Her image of a hand touching a neuron showed her desire to physically see and touch an active neuron in order to further understand the brain and its connections.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write an Article Critique

Tips for Writing a Psychology Critique Paper

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Cultura RM / Gu Cultura / Getty Images

- Steps for Writing a Critique

Evaluating the Article

- How to Write It

- Helpful Tips

An article critique involves critically analyzing a written work to assess its strengths and flaws. If you need to write an article critique, you will need to describe the article, analyze its contents, interpret its meaning, and make an overall assessment of the importance of the work.

Critique papers require students to conduct a critical analysis of another piece of writing, often a book, journal article, or essay . No matter your major, you will probably be expected to write a critique paper at some point.

For psychology students, critiquing a professional paper is a great way to learn more about psychology articles, writing, and the research process itself. Students will analyze how researchers conduct experiments, interpret results, and discuss the impact of the results.

At a Glance

An article critique involves making a critical assessment of a single work. This is often an article, but it might also be a book or other written source. It summarizes the contents of the article and then evaluates both the strengths and weaknesses of the piece. Knowing how to write an article critique can help you learn how to evaluate sources with a discerning eye.

Steps for Writing an Effective Article Critique

While these tips are designed to help students write a psychology critique paper, many of the same principles apply to writing article critiques in other subject areas.

Your first step should always be a thorough read-through of the material you will be analyzing and critiquing. It needs to be more than just a casual skim read. It should be in-depth with an eye toward key elements.

To write an article critique, you should:

- Read the article , noting your first impressions, questions, thoughts, and observations

- Describe the contents of the article in your own words, focusing on the main themes or ideas

- Interpret the meaning of the article and its overall importance

- Critically evaluate the contents of the article, including any strong points as well as potential weaknesses

The following guidelines can help you assess the article you are reading and make better sense of the material.

Read the Introduction Section of the Article

Start by reading the introduction . Think about how this part of the article sets up the main body and how it helps you get a background on the topic.

- Is the hypothesis clearly stated?

- Is the necessary background information and previous research described in the introduction?

In addition to answering these basic questions, note other information provided in the introduction and any questions you have.

Read the Methods Section of the Article

Is the study procedure clearly outlined in the methods section ? Can you determine which variables the researchers are measuring?

Remember to jot down questions and thoughts that come to mind as you are reading. Once you have finished reading the paper, you can then refer back to your initial questions and see which ones remain unanswered.

Read the Results Section of the Article

Are all tables and graphs clearly labeled in the results section ? Do researchers provide enough statistical information? Did the researchers collect all of the data needed to measure the variables in question?

Make a note of any questions or information that does not seem to make sense. You can refer back to these questions later as you are writing your final critique.

Read the Discussion Section of the Article

Experts suggest that it is helpful to take notes while reading through sections of the paper you are evaluating. Ask yourself key questions:

- How do the researchers interpret the results of the study?

- Did the results support their hypothesis?

- Do the conclusions drawn by the researchers seem reasonable?

The discussion section offers students an excellent opportunity to take a position. If you agree with the researcher's conclusions, explain why. If you feel the researchers are incorrect or off-base, point out problems with the conclusions and suggest alternative explanations.

Another alternative is to point out questions the researchers failed to answer in the discussion section.

Begin Writing Your Own Critique of the Paper

Once you have read the article, compile your notes and develop an outline that you can follow as you write your psychology critique paper. Here's a guide that will walk you through how to structure your critique paper.

Introduction

Begin your paper by describing the journal article and authors you are critiquing. Provide the main hypothesis (or thesis) of the paper. Explain why you think the information is relevant.

Thesis Statement

The final part of your introduction should include your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the main idea of your critique. Your thesis should briefly sum up the main points of your critique.

Article Summary

Provide a brief summary of the article. Outline the main points, results, and discussion.

When describing the study or paper, experts suggest that you include a summary of the questions being addressed, study participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design.

Don't get bogged down by your summary. This section should highlight the main points of the article you are critiquing. Don't feel obligated to summarize each little detail of the main paper. Focus on giving the reader an overall idea of the article's content.

Your Analysis

In this section, you will provide your critique of the article. Describe any problems you had with the author's premise, methods, or conclusions. You might focus your critique on problems with the author's argument, presentation, information, and alternatives that have been overlooked.

When evaluating a study, summarize the main findings—including the strength of evidence for each main outcome—and consider their relevance to key demographic groups.

Organize your paper carefully. Be careful not to jump around from one argument to the next. Arguing one point at a time ensures that your paper flows well and is easy to read.

Your critique paper should end with an overview of the article's argument, your conclusions, and your reactions.

More Tips When Writing an Article Critique

- As you are editing your paper, utilize a style guide published by the American Psychological Association, such as the official Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association .

- Reading scientific articles can be challenging at first. Remember that this is a skill that takes time to learn but that your skills will become stronger the more that you read.

- Take a rough draft of your paper to your school's writing lab for additional feedback and use your university library's resources.

What This Means For You

Being able to write a solid article critique is a useful academic skill. While it can be challenging, start by breaking down the sections of the paper, noting your initial thoughts and questions. Then structure your own critique so that you present a summary followed by your evaluation. In your critique, include the strengths and the weaknesses of the article.

Archibald D, Martimianakis MA. Writing, reading, and critiquing reviews . Can Med Educ J . 2021;12(3):1-7. doi:10.36834/cmej.72945

Pautasso M. Ten simple rules for writing a literature review . PLoS Comput Biol . 2013;9(7):e1003149. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

Gülpınar Ö, Güçlü AG. How to write a review article? Turk J Urol . 2013;39(Suppl 1):44–48. doi:10.5152/tud.2013.054

Erol A. Basics of writing review articles . Noro Psikiyatr Ars . 2022;59(1):1-2. doi:10.29399/npa.28093

American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). Washington DC: The American Psychological Association; 2019.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Making sense of research: A guide for critiquing a paper

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Griffith University, Meadowbrook, Queensland.

- PMID: 16114192

- DOI: 10.5172/conu.14.1.38

Learning how to critique research articles is one of the fundamental skills of scholarship in any discipline. The range, quantity and quality of publications available today via print, electronic and Internet databases means it has become essential to equip students and practitioners with the prerequisites to judge the integrity and usefulness of published research. Finding, understanding and critiquing quality articles can be a difficult process. This article sets out some helpful indicators to assist the novice to make sense of research.

Publication types

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Research Design

- Review Literature as Topic

SPH Writing Support Services

- Appointment System

- ESL Conversation Group

- Mini-Courses

- Thesis/Dissertation Writing Group

- Career Writing

- Citing Sources

- Critiquing Research Articles