- Privacy Policy

Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Validity refers to the extent to which a concept, measure, or study accurately represents the intended meaning or reality it is intended to capture. It is a fundamental concept in research and assessment that assesses the soundness and appropriateness of the conclusions, inferences, or interpretations made based on the data or evidence collected.

Research Validity

Research validity refers to the degree to which a study accurately measures or reflects what it claims to measure. In other words, research validity concerns whether the conclusions drawn from a study are based on accurate, reliable and relevant data.

Validity is a concept used in logic and research methodology to assess the strength of an argument or the quality of a research study. It refers to the extent to which a conclusion or result is supported by evidence and reasoning.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several steps and considerations throughout the research process. Here are some key strategies to help maintain research validity:

Clearly Define Research Objectives and Questions

Start by clearly defining your research objectives and formulating specific research questions. This helps focus your study and ensures that you are addressing relevant and meaningful research topics.

Use appropriate research design

Select a research design that aligns with your research objectives and questions. Different types of studies, such as experimental, observational, qualitative, or quantitative, have specific strengths and limitations. Choose the design that best suits your research goals.

Use reliable and valid measurement instruments

If you are measuring variables or constructs, ensure that the measurement instruments you use are reliable and valid. This involves using established and well-tested tools or developing your own instruments through rigorous validation processes.

Ensure a representative sample

When selecting participants or subjects for your study, aim for a sample that is representative of the population you want to generalize to. Consider factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and other relevant demographics to ensure your findings can be generalized appropriately.

Address potential confounding factors

Identify potential confounding variables or biases that could impact your results. Implement strategies such as randomization, matching, or statistical control to minimize the influence of confounding factors and increase internal validity.

Minimize measurement and response biases

Be aware of measurement biases and response biases that can occur during data collection. Use standardized protocols, clear instructions, and trained data collectors to minimize these biases. Employ techniques like blinding or double-blinding in experimental studies to reduce bias.

Conduct appropriate statistical analyses

Ensure that the statistical analyses you employ are appropriate for your research design and data type. Select statistical tests that are relevant to your research questions and use robust analytical techniques to draw accurate conclusions from your data.

Consider external validity

While it may not always be possible to achieve high external validity, be mindful of the generalizability of your findings. Clearly describe your sample and study context to help readers understand the scope and limitations of your research.

Peer review and replication

Submit your research for peer review by experts in your field. Peer review helps identify potential flaws, biases, or methodological issues that can impact validity. Additionally, encourage replication studies by other researchers to validate your findings and enhance the overall reliability of the research.

Transparent reporting

Clearly and transparently report your research methods, procedures, data collection, and analysis techniques. Provide sufficient details for others to evaluate the validity of your study and replicate your work if needed.

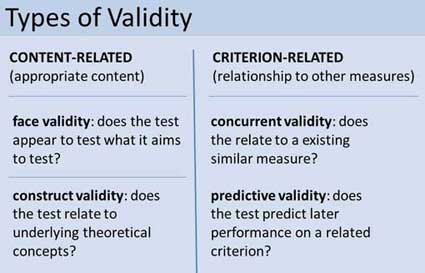

Types of Validity

There are several types of validity that researchers consider when designing and evaluating studies. Here are some common types of validity:

Internal Validity

Internal validity relates to the degree to which a study accurately identifies causal relationships between variables. It addresses whether the observed effects can be attributed to the manipulated independent variable rather than confounding factors. Threats to internal validity include selection bias, history effects, maturation of participants, and instrumentation issues.

External Validity

External validity concerns the generalizability of research findings to the broader population or real-world settings. It assesses the extent to which the results can be applied to other individuals, contexts, or timeframes. Factors that can limit external validity include sample characteristics, research settings, and the specific conditions under which the study was conducted.

Construct Validity

Construct validity examines whether a study adequately measures the intended theoretical constructs or concepts. It focuses on the alignment between the operational definitions used in the study and the underlying theoretical constructs. Construct validity can be threatened by issues such as poor measurement tools, inadequate operational definitions, or a lack of clarity in the conceptual framework.

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the degree to which a measurement instrument or test adequately covers the entire range of the construct being measured. It assesses whether the items or questions included in the measurement tool represent the full scope of the construct. Content validity is often evaluated through expert judgment, reviewing the relevance and representativeness of the items.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity determines the extent to which a measure or test is related to an external criterion or standard. It assesses whether the results obtained from a measurement instrument align with other established measures or outcomes. Criterion validity can be divided into two subtypes: concurrent validity, which examines the relationship between the measure and the criterion at the same time, and predictive validity, which investigates the measure’s ability to predict future outcomes.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the degree to which a measurement or test appears, on the surface, to measure what it intends to measure. It is a subjective assessment based on whether the items seem relevant and appropriate to the construct being measured. Face validity is often used as an initial evaluation before conducting more rigorous validity assessments.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial in research for several reasons:

- Accurate Measurement: Validity ensures that the measurements or observations in a study accurately represent the intended constructs or variables. Without validity, researchers cannot be confident that their results truly reflect the phenomena they are studying. Validity allows researchers to draw accurate conclusions and make meaningful inferences based on their findings.

- Credibility and Trustworthiness: Validity enhances the credibility and trustworthiness of research. When a study demonstrates high validity, it indicates that the researchers have taken appropriate measures to ensure the accuracy and integrity of their work. This strengthens the confidence of other researchers, peers, and the wider scientific community in the study’s results and conclusions.

- Generalizability: Validity helps determine the extent to which research findings can be generalized beyond the specific sample and context of the study. By addressing external validity, researchers can assess whether their results can be applied to other populations, settings, or situations. This information is valuable for making informed decisions, implementing interventions, or developing policies based on research findings.

- Sound Decision-Making: Validity supports informed decision-making in various fields, such as medicine, psychology, education, and social sciences. When validity is established, policymakers, practitioners, and professionals can rely on research findings to guide their actions and interventions. Validity ensures that decisions are based on accurate and trustworthy information, which can lead to better outcomes and more effective practices.

- Avoiding Errors and Bias: Validity helps researchers identify and mitigate potential errors and biases in their studies. By addressing internal validity, researchers can minimize confounding factors and alternative explanations, ensuring that the observed effects are genuinely attributable to the manipulated variables. Validity assessments also highlight measurement errors or shortcomings, enabling researchers to improve their measurement tools and procedures.

- Progress of Scientific Knowledge: Validity is essential for the advancement of scientific knowledge. Valid research contributes to the accumulation of reliable and valid evidence, which forms the foundation for building theories, developing models, and refining existing knowledge. Validity allows researchers to build upon previous findings, replicate studies, and establish a cumulative body of knowledge in various disciplines. Without validity, the scientific community would struggle to make meaningful progress and establish a solid understanding of the phenomena under investigation.

- Ethical Considerations: Validity is closely linked to ethical considerations in research. Conducting valid research ensures that participants’ time, effort, and data are not wasted on flawed or invalid studies. It upholds the principle of respect for participants’ autonomy and promotes responsible research practices. Validity is also important when making claims or drawing conclusions that may have real-world implications, as misleading or invalid findings can have adverse effects on individuals, organizations, or society as a whole.

Examples of Validity

Here are some examples of validity in different contexts:

- Example 1: All men are mortal. John is a man. Therefore, John is mortal. This argument is logically valid because the conclusion follows logically from the premises.

- Example 2: If it is raining, then the ground is wet. The ground is wet. Therefore, it is raining. This argument is not logically valid because there could be other reasons for the ground being wet, such as watering the plants.

- Example 1: In a study examining the relationship between caffeine consumption and alertness, the researchers use established measures of both variables, ensuring that they are accurately capturing the concepts they intend to measure. This demonstrates construct validity.

- Example 2: A researcher develops a new questionnaire to measure anxiety levels. They administer the questionnaire to a group of participants and find that it correlates highly with other established anxiety measures. This indicates good construct validity for the new questionnaire.

- Example 1: A study on the effects of a particular teaching method is conducted in a controlled laboratory setting. The findings of the study may lack external validity because the conditions in the lab may not accurately reflect real-world classroom settings.

- Example 2: A research study on the effects of a new medication includes participants from diverse backgrounds and age groups, increasing the external validity of the findings to a broader population.

- Example 1: In an experiment, a researcher manipulates the independent variable (e.g., a new drug) and controls for other variables to ensure that any observed effects on the dependent variable (e.g., symptom reduction) are indeed due to the manipulation. This establishes internal validity.

- Example 2: A researcher conducts a study examining the relationship between exercise and mood by administering questionnaires to participants. However, the study lacks internal validity because it does not control for other potential factors that could influence mood, such as diet or stress levels.

- Example 1: A teacher develops a new test to assess students’ knowledge of a particular subject. The items on the test appear to be relevant to the topic at hand and align with what one would expect to find on such a test. This suggests face validity, as the test appears to measure what it intends to measure.

- Example 2: A company develops a new customer satisfaction survey. The questions included in the survey seem to address key aspects of the customer experience and capture the relevant information. This indicates face validity, as the survey seems appropriate for assessing customer satisfaction.

- Example 1: A team of experts reviews a comprehensive curriculum for a high school biology course. They evaluate the curriculum to ensure that it covers all the essential topics and concepts necessary for students to gain a thorough understanding of biology. This demonstrates content validity, as the curriculum is representative of the domain it intends to cover.

- Example 2: A researcher develops a questionnaire to assess career satisfaction. The questions in the questionnaire encompass various dimensions of job satisfaction, such as salary, work-life balance, and career growth. This indicates content validity, as the questionnaire adequately represents the different aspects of career satisfaction.

- Example 1: A company wants to evaluate the effectiveness of a new employee selection test. They administer the test to a group of job applicants and later assess the job performance of those who were hired. If there is a strong correlation between the test scores and subsequent job performance, it suggests criterion validity, indicating that the test is predictive of job success.

- Example 2: A researcher wants to determine if a new medical diagnostic tool accurately identifies a specific disease. They compare the results of the diagnostic tool with the gold standard diagnostic method and find a high level of agreement. This demonstrates criterion validity, indicating that the new tool is valid in accurately diagnosing the disease.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, discussions related to validity are typically included in the methodology and results sections. Here are some specific places where you can address validity within your thesis:

Research Design and Methodology

In the methodology section, provide a clear and detailed description of the measures, instruments, or data collection methods used in your study. Discuss the steps taken to establish or assess the validity of these measures. Explain the rationale behind the selection of specific validity types relevant to your study, such as content validity, criterion validity, or construct validity. Discuss any modifications or adaptations made to existing measures and their potential impact on validity.

Measurement Procedures

In the methodology section, elaborate on the procedures implemented to ensure the validity of measurements. Describe how potential biases or confounding factors were addressed, controlled, or accounted for to enhance internal validity. Provide details on how you ensured that the measurement process accurately captures the intended constructs or variables of interest.

Data Collection

In the methodology section, discuss the steps taken to collect data and ensure data validity. Explain any measures implemented to minimize errors or biases during data collection, such as training of data collectors, standardized protocols, or quality control procedures. Address any potential limitations or threats to validity related to the data collection process.

Data Analysis and Results

In the results section, present the analysis and findings related to validity. Report any statistical tests, correlations, or other measures used to assess validity. Provide interpretations and explanations of the results obtained. Discuss the implications of the validity findings for the overall reliability and credibility of your study.

Limitations and Future Directions

In the discussion or conclusion section, reflect on the limitations of your study, including limitations related to validity. Acknowledge any potential threats or weaknesses to validity that you encountered during your research. Discuss how these limitations may have influenced the interpretation of your findings and suggest avenues for future research that could address these validity concerns.

Applications of Validity

Validity is applicable in various areas and contexts where research and measurement play a role. Here are some common applications of validity:

Psychological and Behavioral Research

Validity is crucial in psychology and behavioral research to ensure that measurement instruments accurately capture constructs such as personality traits, intelligence, attitudes, emotions, or psychological disorders. Validity assessments help researchers determine if their measures are truly measuring the intended psychological constructs and if the results can be generalized to broader populations or real-world settings.

Educational Assessment

Validity is essential in educational assessment to determine if tests, exams, or assessments accurately measure students’ knowledge, skills, or abilities. It ensures that the assessment aligns with the educational objectives and provides reliable information about student performance. Validity assessments help identify if the assessment is valid for all students, regardless of their demographic characteristics, language proficiency, or cultural background.

Program Evaluation

Validity plays a crucial role in program evaluation, where researchers assess the effectiveness and impact of interventions, policies, or programs. By establishing validity, evaluators can determine if the observed outcomes are genuinely attributable to the program being evaluated rather than extraneous factors. Validity assessments also help ensure that the evaluation findings are applicable to different populations, contexts, or timeframes.

Medical and Health Research

Validity is essential in medical and health research to ensure the accuracy and reliability of diagnostic tools, measurement instruments, and clinical assessments. Validity assessments help determine if a measurement accurately identifies the presence or absence of a medical condition, measures the effectiveness of a treatment, or predicts patient outcomes. Validity is crucial for establishing evidence-based medicine and informing medical decision-making.

Social Science Research

Validity is relevant in various social science disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, economics, and political science. Researchers use validity to ensure that their measures and methods accurately capture social phenomena, such as social attitudes, behaviors, social structures, or economic indicators. Validity assessments support the reliability and credibility of social science research findings.

Market Research and Surveys

Validity is important in market research and survey studies to ensure that the survey questions effectively measure consumer preferences, buying behaviors, or attitudes towards products or services. Validity assessments help researchers determine if the survey instrument is accurately capturing the desired information and if the results can be generalized to the target population.

Limitations of Validity

Here are some limitations of validity:

- Construct Validity: Limitations of construct validity include the potential for measurement error, inadequate operational definitions of constructs, or the failure to capture all aspects of a complex construct.

- Internal Validity: Limitations of internal validity may arise from confounding variables, selection bias, or the presence of extraneous factors that could influence the study outcomes, making it difficult to attribute causality accurately.

- External Validity: Limitations of external validity can occur when the study sample does not represent the broader population, when the research setting differs significantly from real-world conditions, or when the study lacks ecological validity, i.e., the findings do not reflect real-world complexities.

- Measurement Validity: Limitations of measurement validity can arise from measurement error, inadequately designed or flawed measurement scales, or limitations inherent in self-report measures, such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

- Statistical Conclusion Validity: Limitations in statistical conclusion validity can occur due to sampling errors, inadequate sample sizes, or improper statistical analysis techniques, leading to incorrect conclusions or generalizations.

- Temporal Validity: Limitations of temporal validity arise when the study results become outdated due to changes in the studied phenomena, interventions, or contextual factors.

- Researcher Bias: Researcher bias can affect the validity of a study. Biases can emerge through the researcher’s subjective interpretation, influence of personal beliefs, or preconceived notions, leading to unintentional distortion of findings or failure to consider alternative explanations.

- Ethical Validity: Limitations can arise if the study design or methods involve ethical concerns, such as the use of deceptive practices, inadequate informed consent, or potential harm to participants.

Also see Reliability Vs Validity

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Alternate Forms Reliability – Methods, Examples...

Construct Validity – Types, Threats and Examples

Internal Validity – Threats, Examples and Guide

Reliability Vs Validity

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Split-Half Reliability – Methods, Examples and...

Validity In Psychology Research: Types & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology research, validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement tool accurately measures what it’s intended to measure. It ensures that the research findings are genuine and not due to extraneous factors.

Validity can be categorized into different types based on internal and external validity .

The concept of validity was formulated by Kelly (1927, p. 14), who stated that a test is valid if it measures what it claims to measure. For example, a test of intelligence should measure intelligence and not something else (such as memory).

Internal and External Validity In Research

Internal validity refers to whether the effects observed in a study are due to the manipulation of the independent variable and not some other confounding factor.

In other words, there is a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables .

Internal validity can be improved by controlling extraneous variables, using standardized instructions, counterbalancing, and eliminating demand characteristics and investigator effects.

External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other settings (ecological validity), other people (population validity), and over time (historical validity).

External validity can be improved by setting experiments more naturally and using random sampling to select participants.

Types of Validity In Psychology

Two main categories of validity are used to assess the validity of the test (i.e., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.): Content and criterion.

- Content validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement represents all aspects of the intended content domain. It assesses whether the test items adequately cover the topic or concept.

- Criterion validity assesses the performance of a test based on its correlation with a known external criterion or outcome. It can be further divided into concurrent (measured at the same time) and predictive (measuring future performance) validity.

Face Validity

Face validity is simply whether the test appears (at face value) to measure what it claims to. This is the least sophisticated measure of content-related validity, and is a superficial and subjective assessment based on appearance.

Tests wherein the purpose is clear, even to naïve respondents, are said to have high face validity. Accordingly, tests wherein the purpose is unclear have low face validity (Nevo, 1985).

A direct measurement of face validity is obtained by asking people to rate the validity of a test as it appears to them. This rater could use a Likert scale to assess face validity.

For example:

- The test is extremely suitable for a given purpose

- The test is very suitable for that purpose;

- The test is adequate

- The test is inadequate

- The test is irrelevant and, therefore, unsuitable

It is important to select suitable people to rate a test (e.g., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.). For example, individuals who actually take the test would be well placed to judge its face validity.

Also, people who work with the test could offer their opinion (e.g., employers, university administrators, employers). Finally, the researcher could use members of the general public with an interest in the test (e.g., parents of testees, politicians, teachers, etc.).

The face validity of a test can be considered a robust construct only if a reasonable level of agreement exists among raters.

It should be noted that the term face validity should be avoided when the rating is done by an “expert,” as content validity is more appropriate.

Having face validity does not mean that a test really measures what the researcher intends to measure, but only in the judgment of raters that it appears to do so. Consequently, it is a crude and basic measure of validity.

A test item such as “ I have recently thought of killing myself ” has obvious face validity as an item measuring suicidal cognitions and may be useful when measuring symptoms of depression.

However, the implication of items on tests with clear face validity is that they are more vulnerable to social desirability bias. Individuals may manipulate their responses to deny or hide problems or exaggerate behaviors to present a positive image of themselves.

It is possible for a test item to lack face validity but still have general validity and measure what it claims to measure. This is good because it reduces demand characteristics and makes it harder for respondents to manipulate their answers.

For example, the test item “ I believe in the second coming of Christ ” would lack face validity as a measure of depression (as the purpose of the item is unclear).

This item appeared on the first version of The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and loaded on the depression scale.

Because most of the original normative sample of the MMPI were good Christians, only a depressed Christian would think Christ is not coming back. Thus, for this particular religious sample, the item does have general validity but not face validity.

Construct Validity

Construct validity assesses how well a test or measure represents and captures an abstract theoretical concept, known as a construct. It indicates the degree to which the test accurately reflects the construct it intends to measure, often evaluated through relationships with other variables and measures theoretically connected to the construct.

Construct validity was invented by Cronbach and Meehl (1955). This type of content-related validity refers to the extent to which a test captures a specific theoretical construct or trait, and it overlaps with some of the other aspects of validity

Construct validity does not concern the simple, factual question of whether a test measures an attribute.

Instead, it is about the complex question of whether test score interpretations are consistent with a nomological network involving theoretical and observational terms (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955).

To test for construct validity, it must be demonstrated that the phenomenon being measured actually exists. So, the construct validity of a test for intelligence, for example, depends on a model or theory of intelligence .

Construct validity entails demonstrating the power of such a construct to explain a network of research findings and to predict further relationships.

The more evidence a researcher can demonstrate for a test’s construct validity, the better. However, there is no single method of determining the construct validity of a test.

Instead, different methods and approaches are combined to present the overall construct validity of a test. For example, factor analysis and correlational methods can be used.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity is a subtype of construct validity. It assesses the degree to which two measures that theoretically should be related are related.

It demonstrates that measures of similar constructs are highly correlated. It helps confirm that a test accurately measures the intended construct by showing its alignment with other tests designed to measure the same or similar constructs.

For example, suppose there are two different scales used to measure self-esteem:

Scale A and Scale B. If both scales effectively measure self-esteem, then individuals who score high on Scale A should also score high on Scale B, and those who score low on Scale A should score similarly low on Scale B.

If the scores from these two scales show a strong positive correlation, then this provides evidence for convergent validity because it indicates that both scales seem to measure the same underlying construct of self-esteem.

Concurrent Validity (i.e., occurring at the same time)

Concurrent validity evaluates how well a test’s results correlate with the results of a previously established and accepted measure, when both are administered at the same time.

It helps in determining whether a new measure is a good reflection of an established one without waiting to observe outcomes in the future.

If the new test is validated by comparison with a currently existing criterion, we have concurrent validity.

Very often, a new IQ or personality test might be compared with an older but similar test known to have good validity already.

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity assesses how well a test predicts a criterion that will occur in the future. It measures the test’s ability to foresee the performance of an individual on a related criterion measured at a later point in time. It gauges the test’s effectiveness in predicting subsequent real-world outcomes or results.

For example, a prediction may be made on the basis of a new intelligence test that high scorers at age 12 will be more likely to obtain university degrees several years later. If the prediction is born out, then the test has predictive validity.

Cronbach, L. J., and Meehl, P. E. (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin , 52, 281-302.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1943). Manual for the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory . New York: Psychological Corporation.

Kelley, T. L. (1927). Interpretation of educational measurements. New York : Macmillan.

Nevo, B. (1985). Face validity revisited . Journal of Educational Measurement , 22(4), 287-293.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on 10 October 2022.

In quantitative research , you have to consider the reliability and validity of your methods and measurements.

Validity tells you how accurately a method measures something. If a method measures what it claims to measure, and the results closely correspond to real-world values, then it can be considered valid. There are four main types of validity:

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

- Content validity : Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure?

- Face validity : Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims?

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

Note that this article deals with types of test validity, which determine the accuracy of the actual components of a measure. If you are doing experimental research, you also need to consider internal and external validity , which deal with the experimental design and the generalisability of results.

Table of contents

Construct validity, content validity, face validity, criterion validity.

Construct validity evaluates whether a measurement tool really represents the thing we are interested in measuring. It’s central to establishing the overall validity of a method.

What is a construct?

A construct refers to a concept or characteristic that can’t be directly observed but can be measured by observing other indicators that are associated with it.

Constructs can be characteristics of individuals, such as intelligence, obesity, job satisfaction, or depression; they can also be broader concepts applied to organisations or social groups, such as gender equality, corporate social responsibility, or freedom of speech.

What is construct validity?

Construct validity is about ensuring that the method of measurement matches the construct you want to measure. If you develop a questionnaire to diagnose depression, you need to know: does the questionnaire really measure the construct of depression? Or is it actually measuring the respondent’s mood, self-esteem, or some other construct?

To achieve construct validity, you have to ensure that your indicators and measurements are carefully developed based on relevant existing knowledge. The questionnaire must include only relevant questions that measure known indicators of depression.

The other types of validity described below can all be considered as forms of evidence for construct validity.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Content validity assesses whether a test is representative of all aspects of the construct.

To produce valid results, the content of a test, survey, or measurement method must cover all relevant parts of the subject it aims to measure. If some aspects are missing from the measurement (or if irrelevant aspects are included), the validity is threatened.

Face validity considers how suitable the content of a test seems to be on the surface. It’s similar to content validity, but face validity is a more informal and subjective assessment.

As face validity is a subjective measure, it’s often considered the weakest form of validity. However, it can be useful in the initial stages of developing a method.

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test can predict a concrete outcome, or how well the results of your test approximate the results of another test.

What is a criterion variable?

A criterion variable is an established and effective measurement that is widely considered valid, sometimes referred to as a ‘gold standard’ measurement. Criterion variables can be very difficult to find.

What is criterion validity?

To evaluate criterion validity, you calculate the correlation between the results of your measurement and the results of the criterion measurement. If there is a high correlation, this gives a good indication that your test is measuring what it intends to measure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Middleton, F. (2022, October 10). The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/validity-types/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, what is qualitative research | methods & examples.

Validity in research: a guide to measuring the right things

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Validity is necessary for all types of studies ranging from market validation of a business or product idea to the effectiveness of medical trials and procedures. So, how can you determine whether your research is valid? This guide can help you understand what validity is, the types of validity in research, and the factors that affect research validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is validity?

In the most basic sense, validity is the quality of being based on truth or reason. Valid research strives to eliminate the effects of unrelated information and the circumstances under which evidence is collected.

Validity in research is the ability to conduct an accurate study with the right tools and conditions to yield acceptable and reliable data that can be reproduced. Researchers rely on carefully calibrated tools for precise measurements. However, collecting accurate information can be more of a challenge.

Studies must be conducted in environments that don't sway the results to achieve and maintain validity. They can be compromised by asking the wrong questions or relying on limited data.

Why is validity important in research?

Research is used to improve life for humans. Every product and discovery, from innovative medical breakthroughs to advanced new products, depends on accurate research to be dependable. Without it, the results couldn't be trusted, and products would likely fail. Businesses would lose money, and patients couldn't rely on medical treatments.

While wasting money on a lousy product is a concern, lack of validity paints a much grimmer picture in the medical field or producing automobiles and airplanes, for example. Whether you're launching an exciting new product or conducting scientific research, validity can determine success and failure.

- What is reliability?

Reliability is the ability of a method to yield consistency. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same method to measure something, the measurement method is said to be reliable. For example, a thermometer that shows the same temperatures each time in a controlled environment is reliable.

While high reliability is a part of measuring validity, it's only part of the puzzle. If the reliable thermometer hasn't been properly calibrated and reliably measures temperatures two degrees too high, it doesn't provide a valid (accurate) measure of temperature.

Similarly, if a researcher uses a thermometer to measure weight, the results won't be accurate because it's the wrong tool for the job.

- How are reliability and validity assessed?

While measuring reliability is a part of measuring validity, there are distinct ways to assess both measurements for accuracy.

How is reliability measured?

These measures of consistency and stability help assess reliability, including:

Consistency and stability of the same measure when repeated multiple times and conditions

Consistency and stability of the measure across different test subjects

Consistency and stability of results from different parts of a test designed to measure the same thing

How is validity measured?

Since validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure, it can be difficult to assess the accuracy. Validity can be estimated by comparing research results to other relevant data or theories.

The adherence of a measure to existing knowledge of how the concept is measured

The ability to cover all aspects of the concept being measured

The relation of the result in comparison with other valid measures of the same concept

- What are the types of validity in a research design?

Research validity is broadly gathered into two groups: internal and external. Yet, this grouping doesn't clearly define the different types of validity. Research validity can be divided into seven distinct groups.

Face validity : A test that appears valid simply because of the appropriateness or relativity of the testing method, included information, or tools used.

Content validity : The determination that the measure used in research covers the full domain of the content.

Construct validity : The assessment of the suitability of the measurement tool to measure the activity being studied.

Internal validity : The assessment of how your research environment affects measurement results. This is where other factors can’t explain the extent of an observed cause-and-effect response.

External validity : The extent to which the study will be accurate beyond the sample and the level to which it can be generalized in other settings, populations, and measures.

Statistical conclusion validity: The determination of whether a relationship exists between procedures and outcomes (appropriate sampling and measuring procedures along with appropriate statistical tests).

Criterion-related validity : A measurement of the quality of your testing methods against a criterion measure (like a “gold standard” test) that is measured at the same time.

- Examples of validity

Like different types of research and the various ways to measure validity, examples of validity can vary widely. These include:

A questionnaire may be considered valid because each question addresses specific and relevant aspects of the study subject.

In a brand assessment study, researchers can use comparison testing to verify the results of an initial study. For example, the results from a focus group response about brand perception are considered more valid when the results match that of a questionnaire answered by current and potential customers.

A test to measure a class of students' understanding of the English language contains reading, writing, listening, and speaking components to cover the full scope of how language is used.

- Factors that affect research validity

Certain factors can affect research validity in both positive and negative ways. By understanding the factors that improve validity and those that threaten it, you can enhance the validity of your study. These include:

Random selection of participants vs. the selection of participants that are representative of your study criteria

Blinding with interventions the participants are unaware of (like the use of placebos)

Manipulating the experiment by inserting a variable that will change the results

Randomly assigning participants to treatment and control groups to avoid bias

Following specific procedures during the study to avoid unintended effects

Conducting a study in the field instead of a laboratory for more accurate results

Replicating the study with different factors or settings to compare results

Using statistical methods to adjust for inconclusive data

What are the common validity threats in research, and how can their effects be minimized or nullified?

Research validity can be difficult to achieve because of internal and external threats that produce inaccurate results. These factors can jeopardize validity.

History: Events that occur between an early and later measurement

Maturation: The passage of time in a study can include data on actions that would have naturally occurred outside of the settings of the study

Repeated testing: The outcome of repeated tests can change the outcome of followed tests

Selection of subjects: Unconscious bias which can result in the selection of uniform comparison groups

Statistical regression: Choosing subjects based on extremes doesn't yield an accurate outcome for the majority of individuals

Attrition: When the sample group is diminished significantly during the course of the study

Maturation: When subjects mature during the study, and natural maturation is awarded to the effects of the study

While some validity threats can be minimized or wholly nullified, removing all threats from a study is impossible. For example, random selection can remove unconscious bias and statistical regression.

Researchers can even hope to avoid attrition by using smaller study groups. Yet, smaller study groups could potentially affect the research in other ways. The best practice for researchers to prevent validity threats is through careful environmental planning and t reliable data-gathering methods.

- How to ensure validity in your research

Researchers should be mindful of the importance of validity in the early planning stages of any study to avoid inaccurate results. Researchers must take the time to consider tools and methods as well as how the testing environment matches closely with the natural environment in which results will be used.

The following steps can be used to ensure validity in research:

Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Use appropriate sampling to choose test subjects

Create an accurate testing environment

How do you maintain validity in research?

Accurate research is usually conducted over a period of time with different test subjects. To maintain validity across an entire study, you must take specific steps to ensure that gathered data has the same levels of accuracy.

Consistency is crucial for maintaining validity in research. When researchers apply methods consistently and standardize the circumstances under which data is collected, validity can be maintained across the entire study.

Is there a need for validation of the research instrument before its implementation?

An essential part of validity is choosing the right research instrument or method for accurate results. Consider the thermometer that is reliable but still produces inaccurate results. You're unlikely to achieve research validity without activities like calibration, content, and construct validity.

- Understanding research validity for more accurate results

Without validity, research can't provide the accuracy necessary to deliver a useful study. By getting a clear understanding of validity in research, you can take steps to improve your research skills and achieve more accurate results.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

What is the Significance of Validity in Research?

Introduction

- What is validity in simple terms?

Internal validity vs. external validity in research

Uncovering different types of research validity, factors that improve research validity.

In qualitative research , validity refers to an evaluation metric for the trustworthiness of study findings. Within the expansive landscape of research methodologies , the qualitative approach, with its rich, narrative-driven investigations, demands unique criteria for ensuring validity.

Unlike its quantitative counterpart, which often leans on numerical robustness and statistical veracity, the essence of validity in qualitative research delves deep into the realms of credibility, dependability, and the richness of the data .

The importance of validity in qualitative research cannot be overstated. Establishing validity refers to ensuring that the research findings genuinely reflect the phenomena they are intended to represent. It reinforces the researcher's responsibility to present an authentic representation of study participants' experiences and insights.

This article will examine validity in qualitative research, exploring its characteristics, techniques to bolster it, and the challenges that researchers might face in establishing validity.

At its core, validity in research speaks to the degree to which a study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure or understand. It's about ensuring that the study investigates what it purports to investigate. While this seems like a straightforward idea, the way validity is approached can vary greatly between qualitative and quantitative research .

Quantitative research often hinges on numerical, measurable data. In this paradigm, validity might refer to whether a specific tool or method measures the correct variable, without interference from other variables. It's about numbers, scales, and objective measurements. For instance, if one is studying personalities by administering surveys, a valid instrument could be a survey that has been rigorously developed and tested to verify that the survey questions are referring to personality characteristics and not other similar concepts, such as moods, opinions, or social norms.

Conversely, qualitative research is more concerned with understanding human behavior and the reasons that govern such behavior. It's less about measuring in the strictest sense and more about interpreting the phenomenon that is being studied. The questions become: "Are these interpretations true representations of the human experience being studied?" and "Do they authentically convey participants' perspectives and contexts?"

Differentiating between qualitative and quantitative validity is crucial because the research methods to ensure validity differ between these research paradigms. In quantitative realms, validity might involve test-retest reliability or examining the internal consistency of a test.

In the qualitative sphere, however, the focus shifts to ensuring that the researcher's interpretations align with the actual experiences and perspectives of their subjects.

This distinction is fundamental because it impacts how researchers engage in research design , gather data , and draw conclusions . Ensuring validity in qualitative research is like weaving a tapestry: every strand of data must be carefully interwoven with the interpretive threads of the researcher, creating a cohesive and faithful representation of the studied experience.

While often terms associated more closely with quantitative research, internal and external validity can still be relevant concepts to understand within the context of qualitative inquiries. Grasping these notions can help qualitative researchers better navigate the challenges of ensuring their findings are both credible and applicable in wider contexts.

Internal validity

Internal validity refers to the authenticity and truthfulness of the findings within the study itself. In qualitative research , this might involve asking: Do the conclusions drawn genuinely reflect the perspectives and experiences of the study's participants?

Internal validity revolves around the depth of understanding, ensuring that the researcher's interpretations are grounded in participants' realities. Techniques like member checking , where participants review and verify the researcher's interpretations , can bolster internal validity.

External validity

External validity refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be generalized or applied to other settings or groups. For qualitative researchers, the emphasis isn't on statistical generalizability, as often seen in quantitative studies. Instead, it's about transferability.

It becomes a matter of determining how and where the insights gathered might be relevant in other contexts. This doesn't mean that every qualitative study's findings will apply universally, but qualitative researchers should provide enough detail (through rich, thick descriptions) to allow readers or other researchers to determine the potential for transfer to other contexts.

Try out a free trial of ATLAS.ti today

See how you can turn your data into critical research findings with our intuitive interface.

Looking deeper into the realm of validity, it's crucial to recognize and understand its various types. Each type offers distinct criteria and methods of evaluation, ensuring that research remains robust and genuine. Here's an exploration of some of these types.

Construct validity

Construct validity is a cornerstone in research methodology . It pertains to ensuring that the tools or methods used in a research study genuinely capture the intended theoretical constructs.

In qualitative research , the challenge lies in the abstract nature of many constructs. For example, if one were to investigate "emotional intelligence" or "social cohesion," the definitions might vary, making them hard to pin down.

To bolster construct validity, it is important to clearly and transparently define the concepts being studied. In addition, researchers may triangulate data from multiple sources , ensuring that different viewpoints converge towards a shared understanding of the construct. Furthermore, they might delve into iterative rounds of data collection, refining their methods with each cycle to better align with the conceptual essence of their focus.

Content validity

Content validity's emphasis is on the breadth and depth of the content being assessed. In other words, content validity refers to capturing all relevant facets of the phenomenon being studied. Within qualitative paradigms, ensuring comprehensive representation is paramount. If, for instance, a researcher is using interview protocols to understand community perceptions of a local policy, it's crucial that the questions encompass all relevant aspects of that policy. This could range from its implementation and impact to public awareness and opinion variations across demographic groups.

Enhancing content validity can involve expert reviews where subject matter experts evaluate tools or methods for comprehensiveness. Another strategy might involve pilot studies , where preliminary data collection reveals gaps or overlooked aspects that can be addressed in the main study.

Ecological validity

Ecological validity refers to the genuine reflection of real-world situations in research findings. For qualitative researchers, this means their observations , interpretations , and conclusions should resonate with the participants and context being studied.

If a study explores classroom dynamics, for example, studying students and teachers in a controlled research setting would have lower ecological validity than studying real classroom settings. Ecological validity is important to consider because it helps ensure the research is relevant to the people being studied. Individuals might behave entirely different in a controlled environment as opposed to their everyday natural settings.

Ecological validity tends to be stronger in qualitative research compared to quantitative research , because qualitative researchers are typically immersed in their study context and explore participants' subjective perceptions and experiences. Quantitative research, in contrast, can sometimes be more artificial if behavior is being observed in a lab or participants have to choose from predetermined options to answer survey questions.

Qualitative researchers can further bolster ecological validity through immersive fieldwork, where researchers spend extended periods in the studied environment. This immersion helps them capture the nuances and intricacies that might be missed in brief or superficial engagements.

Face validity

Face validity, while seemingly straightforward, holds significant weight in the preliminary stages of research. It serves as a litmus test, gauging the apparent appropriateness and relevance of a tool or method. If a researcher is developing a new interview guide to gauge employee satisfaction, for instance, a quick assessment from colleagues or a focus group can reveal if the questions intuitively seem fit for the purpose.

While face validity is more subjective and lacks the depth of other validity types, it's a crucial initial step, ensuring that the research starts on the right foot.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity evaluates how well the results obtained from one method correlate with those from another, more established method. In many research scenarios, establishing high criterion validity involves using statistical methods to measure validity. For instance, a researcher might utilize the appropriate statistical tests to determine the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two sets of data.

If a new measurement tool or method is being introduced, its validity might be established by statistically correlating its outcomes with those of a gold standard or previously validated tool. Correlational statistics can estimate the strength of the relationship between the new instrument and the previously established instrument, and regression analyses can also be useful to predict outcomes based on established criteria.

While these methods are traditionally aligned with quantitative research, qualitative researchers, particularly those using mixed methods , may also find value in these statistical approaches, especially when wanting to quantify certain aspects of their data for comparative purposes. More broadly, qualitative researchers could compare their operationalizations and findings to other similar qualitative studies to assess that they are indeed examining what they intend to study.

In the realm of qualitative research , the role of the researcher is not just that of an observer but often as an active participant in the meaning-making process. This unique positioning means the researcher's perspectives and interactions can significantly influence the data collected and its interpretation . Here's a deep dive into the researcher's pivotal role in upholding validity.

Reflexivity

A key concept in qualitative research, reflexivity requires researchers to continually reflect on their worldviews, beliefs, and potential influence on the data. By maintaining a reflexive journal or engaging in regular introspection, researchers can identify and address their own biases , ensuring a more genuine interpretation of participant narratives.

Building rapport

The depth and authenticity of information shared by participants often hinge on the rapport and trust established with the researcher. By cultivating genuine, non-judgmental, and empathetic relationships with participants, researchers can enhance the validity of the data collected.

Positionality

Every researcher brings to the study their own background, including their culture, education, socioeconomic status, and more. Recognizing how this positionality might influence interpretations and interactions is crucial. By acknowledging and transparently sharing their positionality, researchers can offer context to their findings and interpretations.

Active listening

The ability to listen without imposing one's own judgments or interpretations is vital. Active listening ensures that researchers capture the participants' experiences and emotions without distortion, enhancing the validity of the findings.

Transparency in methods

To ensure validity, researchers should be transparent about every step of their process. From how participants were selected to how data was analyzed , a clear documentation offers others a chance to understand and evaluate the research's authenticity and rigor .

Member checking

Once data is collected and interpreted, revisiting participants to confirm the researcher's interpretations can be invaluable. This process, known as member checking , ensures that the researcher's understanding aligns with the participants' intended meanings, bolstering validity.

Embracing ambiguity

Qualitative data can be complex and sometimes contradictory. Instead of trying to fit data into preconceived notions or frameworks, researchers must embrace ambiguity, acknowledging areas of uncertainty or multiple interpretations.

Make the most of your research study with ATLAS.ti

From study design to data analysis, let ATLAS.ti guide you through the research process. Download a free trial today.

Validity & Reliability In Research

A Plain-Language Explanation (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | September 2023

Validity and reliability are two related but distinctly different concepts within research. Understanding what they are and how to achieve them is critically important to any research project. In this post, we’ll unpack these two concepts as simply as possible.

This post is based on our popular online course, Research Methodology Bootcamp . In the course, we unpack the basics of methodology using straightfoward language and loads of examples. If you’re new to academic research, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Validity & Reliability

- The big picture

- Validity 101

- Reliability 101

- Key takeaways

First, The Basics…

First, let’s start with a big-picture view and then we can zoom in to the finer details.

Validity and reliability are two incredibly important concepts in research, especially within the social sciences. Both validity and reliability have to do with the measurement of variables and/or constructs – for example, job satisfaction, intelligence, productivity, etc. When undertaking research, you’ll often want to measure these types of constructs and variables and, at the simplest level, validity and reliability are about ensuring the quality and accuracy of those measurements .

As you can probably imagine, if your measurements aren’t accurate or there are quality issues at play when you’re collecting your data, your entire study will be at risk. Therefore, validity and reliability are very important concepts to understand (and to get right). So, let’s unpack each of them.

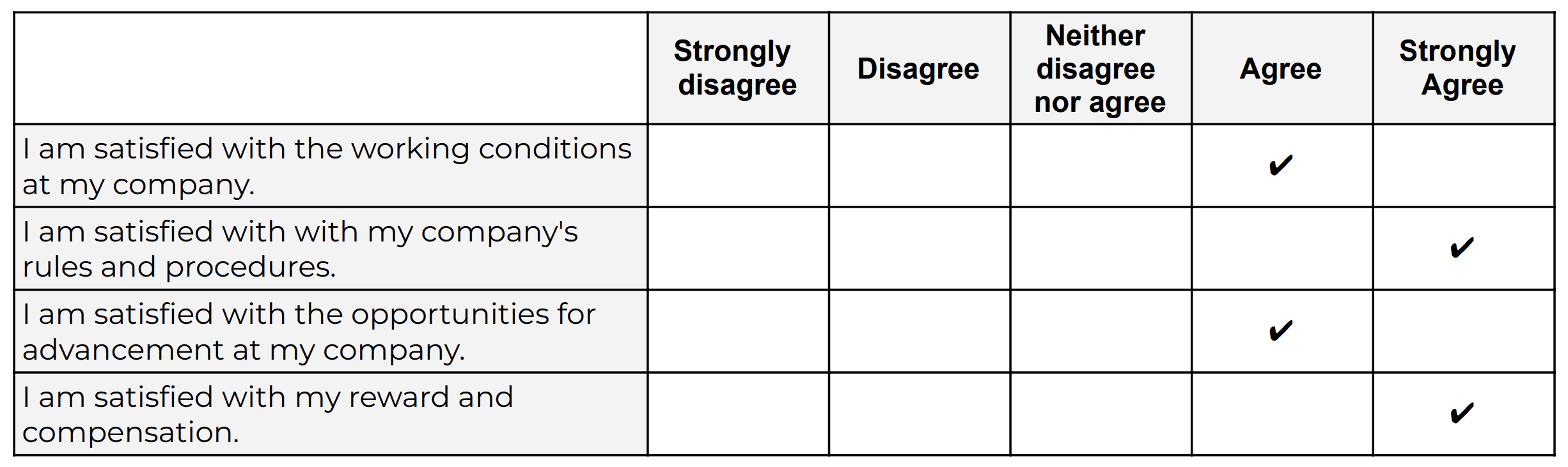

What Is Validity?

In simple terms, validity (also called “construct validity”) is all about whether a research instrument accurately measures what it’s supposed to measure .

For example, let’s say you have a set of Likert scales that are supposed to quantify someone’s level of overall job satisfaction. If this set of scales focused purely on only one dimension of job satisfaction, say pay satisfaction, this would not be a valid measurement, as it only captures one aspect of the multidimensional construct. In other words, pay satisfaction alone is only one contributing factor toward overall job satisfaction, and therefore it’s not a valid way to measure someone’s job satisfaction.

Oftentimes in quantitative studies, the way in which the researcher or survey designer interprets a question or statement can differ from how the study participants interpret it . Given that respondents don’t have the opportunity to ask clarifying questions when taking a survey, it’s easy for these sorts of misunderstandings to crop up. Naturally, if the respondents are interpreting the question in the wrong way, the data they provide will be pretty useless . Therefore, ensuring that a study’s measurement instruments are valid – in other words, that they are measuring what they intend to measure – is incredibly important.

There are various types of validity and we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole in this post, but it’s worth quickly highlighting the importance of making sure that your research instrument is tightly aligned with the theoretical construct you’re trying to measure . In other words, you need to pay careful attention to how the key theories within your study define the thing you’re trying to measure – and then make sure that your survey presents it in the same way.

For example, sticking with the “job satisfaction” construct we looked at earlier, you’d need to clearly define what you mean by job satisfaction within your study (and this definition would of course need to be underpinned by the relevant theory). You’d then need to make sure that your chosen definition is reflected in the types of questions or scales you’re using in your survey . Simply put, you need to make sure that your survey respondents are perceiving your key constructs in the same way you are. Or, even if they’re not, that your measurement instrument is capturing the necessary information that reflects your definition of the construct at hand.

If all of this talk about constructs sounds a bit fluffy, be sure to check out Research Methodology Bootcamp , which will provide you with a rock-solid foundational understanding of all things methodology-related. Remember, you can take advantage of our 60% discount offer using this link.

Need a helping hand?

What Is Reliability?

As with validity, reliability is an attribute of a measurement instrument – for example, a survey, a weight scale or even a blood pressure monitor. But while validity is concerned with whether the instrument is measuring the “thing” it’s supposed to be measuring, reliability is concerned with consistency and stability . In other words, reliability reflects the degree to which a measurement instrument produces consistent results when applied repeatedly to the same phenomenon , under the same conditions .

As you can probably imagine, a measurement instrument that achieves a high level of consistency is naturally more dependable (or reliable) than one that doesn’t – in other words, it can be trusted to provide consistent measurements . And that, of course, is what you want when undertaking empirical research. If you think about it within a more domestic context, just imagine if you found that your bathroom scale gave you a different number every time you hopped on and off of it – you wouldn’t feel too confident in its ability to measure the variable that is your body weight 🙂

It’s worth mentioning that reliability also extends to the person using the measurement instrument . For example, if two researchers use the same instrument (let’s say a measuring tape) and they get different measurements, there’s likely an issue in terms of how one (or both) of them are using the measuring tape. So, when you think about reliability, consider both the instrument and the researcher as part of the equation.

As with validity, there are various types of reliability and various tests that can be used to assess the reliability of an instrument. A popular one that you’ll likely come across for survey instruments is Cronbach’s alpha , which is a statistical measure that quantifies the degree to which items within an instrument (for example, a set of Likert scales) measure the same underlying construct . In other words, Cronbach’s alpha indicates how closely related the items are and whether they consistently capture the same concept .

Recap: Key Takeaways

Alright, let’s quickly recap to cement your understanding of validity and reliability:

- Validity is concerned with whether an instrument (e.g., a set of Likert scales) is measuring what it’s supposed to measure

- Reliability is concerned with whether that measurement is consistent and stable when measuring the same phenomenon under the same conditions.

In short, validity and reliability are both essential to ensuring that your data collection efforts deliver high-quality, accurate data that help you answer your research questions . So, be sure to always pay careful attention to the validity and reliability of your measurement instruments when collecting and analysing data. As the adage goes, “rubbish in, rubbish out” – make sure that your data inputs are rock-solid.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Methodology Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS.

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS AND I HAVE GREATLY BENEFITED FROM THE CONTENT.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Validity of Research and Measurements

Chris nickson.

- Nov 3, 2020

In general terms, validity is “the quality of being true or correct”, it refers to the strength of results and how accurately they reflect the real world. Thus ‘validity’ can have quite different meanings depending on the context!

- Reliability is distinct from validity, in that it refers to the consistency or repeatability of results

- internal validity

- external validity

- Validity applies to an outcome or measurement, not the instrument used to obtain it and is based on ‘validity evidence’

INTERNAL VALIDITY

- The extent to which the design and conduct of the trial eliminate the possibility of bias, such that observed effects can be attributed to the independent variable

- refers to the accuracy of a trial

- a study that lacks internal validity should not applied to any clinical setting

- power calculation

- details of study context and intervention

- avoid loss of follow up

- standardised treatment conditions

- control groups

- objectivity from blinding and data handling

- Clinical research can be internally valid despite poor external validity

EXTERNAL VALIDITY

- The extent to which the results of a trial provide a correct basis for generalizations to other circumstances

- Also called “generalizability or “applicability”

- Studies can only be applied to clinical settings the same, or similar, to those used in the study

- population validity – how well the study sample can be extrapolated to the population as a whole (based on randomized sampling)

- ecological validity – the extent to which the study environment influences results (can the study be replicated in other contexts?)

- internal/ construct validity – verified relationships between dependent and independent variables

- Research findings cannot have external validity without being internally valid

FACTORS THAT AFFECT EXTERNAL VALIDITY OF CLINICAL RESEARCH (Rothwell, 2006)

Setting of the trial

- healthcare system

- recruitment from primary, secondary or tertiary care

- selection of participating centers

- selection of participating clinicians

Selection of patients

- methods of pre-randomisation diagnosis and investigation

- eligibility criteria

- exclusion criteria

- placebo run-in period

- treatment run-in period

- “enrichment” strategies

- ratio of randomised patients to eligible non-randomised patients in participating centers

- proportion of patients who decline randomisation

Characteristics of randomised patients

- baseline clinical characteristics

- racial group

- uniformity of underlying pathology

- stage in the natural history of disease

- severity of disease

- comorbidity

- absolute risk of a poor outcome in the control group

Differences between trial protocol and routine practice

- trial intervention

- timing of treatment

- appropriateness/ relevance of control intervention

- adequacy of nontrial treatment – both intended and actual

- prohibition of certain non-trial treatments

- Therapeutic or diagnostic advances since trial was performed

Outcome measures and follow up

- clinical relevance of surrogate outcomes

- clinical relevance, validity, and reproducibility of complex scales

- effect of intervention on most relevant components of composite outcomes

- identification of who measured outcome

- use of patient outcomes

- frequency of follow up

- adequacy of length of follow-up

Adverse effects of treatment

- completeness of reporting of relevant adverse effects

- rate of discontinuation of treatment

- selection of trial centers on the basis of skill or experience

- exclusion of patients at risk of complications

- exclusion of patients who experienced adverse events during a run in period

- intensity of trial safety procedures

MEASUREMENT VALIDITY (Downing & Yudkowsky, 2009)

Validity refers to the evidence presented to support or to refute the meaning or interpretation assigned to assessment data or results. It relates to whether a test, tool, instrument or device actually measures what it intends to measure.

Traditionally validity was viewed as a trinatarian concept based on:

- degree to which the the test measures what it is meant to be measuring

- e.g. the ideal depression score would include different variants of depression and be able to distinguish depression from stress and anxiety

- Concurrent validity – compares measurements with an outcome at the same time (e.g. a concurrent “gold standard” test result)

- Predictive validity – compares measurements with an outcome at the same time (e.g. do high exam marks predict subsequent incomes?)

- the degree to which the content of an instrument is an adequate reflection of all the components of the construct

- e.g. a schizophrenia score would need to include both positive and negative symptoms

According to current validity theory in psychometrics, validity is a unitary concept and thus construct validity is the only form of validity. For instance in health professions education, validity evidence for assessments comes from (:

- relationship between test content and the construct of interest

- theory; hypothesis about content

- independent assessment of match between content sampled and domain of interest

- solid, scientific, quantitative evidence

- analysis of individual responses to stimuli

- debriefing of examinees

- process studies aimed at understanding what is measured and the soundness of intended score interpretations

- quality assurance and quality control of assessment data

- data internal to assessments such as: reliability or reproducibility of scores; inter-item correlations; statistical characteristics of items; statistical analysis of item option function; factor studies of dimensionality; Differential Item Functioning (DIF) studies

- a. Convergent and discriminant evidence: relationships between similar and different measures

- b. Test-criterion evidence: relationships between test and criterion measure(s)

- c. Validity generalization: can the validity evidence be generalized? Evidence that the validity studies may generalize to other settings.

- intended and unintended consequences of test use

- differential consequences of test use

- impact of assessment on students, instructors, schools, society

- impact of assessments on curriculum; cost/benefit analysis with respect to tradeoff between instructional time and assessment time.

- Note that strictly speaking we cannot comment on the validity of a test, tool, instrument, or device, only on the measurement that is obtained. This is because the the same test used in a different context (different operator, different subjects, different circumstances, at a different time) may not be valid. In other words, validity evidence applies to the data generated by an instrument, not the instrument itself.

- Validity can be equated with accuracy, and reliability with precision

- Face validity is a term commonly used as an indicator of validity – it is essential worthless! It means at ‘face value’, in other words, the degree to which the measure subjectively looks like what it is intended to measure.

- The higher the stakes of measurement (e.g. test result), the higher the need for validity evidence.

- You can never have too much validity evidence, but the minimum required varies with purpose (e.g. high stakes fellowship exam versus one of many progress tests)

References and Links

Journal articles and Textbooks

- Downing SM, Yudkowsky R. (2009) Assessment in health professions education, Routledge, New York.

- Rothwell PM. Factors that can affect the external validity of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006 May;1(1):e9. [ pubmed ] [ article ]

- Shankar-Hari M, Bertolini G, Brunkhorst FM, et al. Judging quality of current septic shock definitions and criteria. Critical care. 19(1):445. 2015. [ pubmed ] [ article ]

Critical Care