- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

There is more to war poetry than mud, wire and slaughter

Poems about the first world war have defined the genre for decades. It is time to hear from new voices that reflect a wider view of conflicts

W hen we say “war poetry” today, the sort of writing that comes to mind is a conglomeration of Wilfred Owen , Siegfried Sassoon and the other great writers of the first world war. It means descriptions of mud, wire and slaughter on a horrific scale. It includes accusations that the top brass prolonged hostilities for no good reason and that people at home supported the cause in ignorance. It involves fierce protest as well as intense sympathy. It issues a warning.

Because poetry of this sort has been drip-fed into British schools for several generations (interestingly, the process did not start as soon as the war ended, but only began in earnest during the 1960s), it has settled in the public mind at an extraordinary depth. There are large benefits, of course. The best poetry of the first world war is exceptionally powerful – not just the lyrics of Owen and others, but the more complex and modernistic narrative of In Parenthesis by David Jones (which still has some claim to be considered a neglected masterpiece). Furthermore, by rubbing its readers’ noses in the brutal facts of conflict and suffering, it possibly creates a social value as well – by helping to educate people in the human cost of war, and in the process discouraging them from starting or supporting another one.

At the same time, maybe there are disadvantages. Perhaps by placing such an emphasis on war poetry in the school curriculum, we don’t actually put people off the idea of fighting, but inculcate the idea that it is somehow normal for the British to take up arms? Perhaps it solidifies the idea of us as a war-like nation? There is a literary consequence to the classroom focus too. By concentrating on the poetry of one conflict, which to an important extent is shaped by its particular circumstances, it directs attention away from the poetry of other wars.

Not just the poetry of other wars, in fact, but other kinds of war poetry. “I am the enemy you killed, my friend,” says the dead soldier encountered in Owen’s “Strange Meeting”: “I parried; but my hands were loath and cold”. This summarises the whole circumstance of first world war poetry: it often involved hand-to-hand fighting; it was intimate. The second world war, by contrast, was for many soldiers a more distanced affair. Keith Douglas when taking aim in his poem “How to Kill”, says: “Now in my dial of glass appears / the soldier who is going to die”. He still thinks of him as a fellow creature (the soldier “moves about in ways / his mother knows, habits of his”) but also feels a crucial separation – a gap that exists as a physical space, and proves the conflict has frozen or exterminated a part of the speaker’s own humanity.

The difference between these two poems is shorthand for the differences between two periods and two kinds of war poetry. It is also an opportunity to point out that while the Owen poem has been read by millions of schoolchildren in the last 50-odd years, the Douglas poem (which is just as good, if not better) has been read by a handful. By not conforming to the pattern of war poetry laid down between 1914 and 1918 (actually between about 1916 and 1918), it has been sidelined.

The point here is not to discredit poetry of the first world war. As a collective act of witness, made at an extraordinary level of technical skill and with equally extraordinary emotional power, it is in its terrible way magnificent. The point, rather, is to say that our definition of “war poetry” has become too narrow to be accurate or fair. By extending it we are not only able to make a large literary gain – by admiring a much wider range of expertise, thoughtfulness and compassion – but also to appreciate in even more varied and detailed ways the effects of war.

This applies to the first world war itself, if we look away from the frontline and move to the home-front poetry of men in uniform such as Edward Thomas , or women waiting for them such as Eleanor Farjeon . Or to the extraordinary reports by nurses and other volunteers such as Helen Mackay, May Wedderburn Cannan and Margaret Postgate Cole . Or to the visceral and proto-existentialist poems and songs and chants of “Anonymous” (“I don’t want a bayonet up my arsehole, / I don’t want my bollocks shot away”).

A glance across the landscape of war poetry written after 1918 gives an even more dramatic sense of variety. The frontline (in north Africa, then France) brilliantly evoked by Douglas – in his poetry as well as his memoir Alamein to Zem Zem – is just a part of the large picture in which also appears Alun Lewis writing about soldierly boredom and nervous waiting during the second world war, and Dylan Thomas writing about the blitz – and, around them, international voices speaking with and through and over them: Nelly Sachs , Paul Celan , Anna Akhmatova and Tadeusz Różewicz .

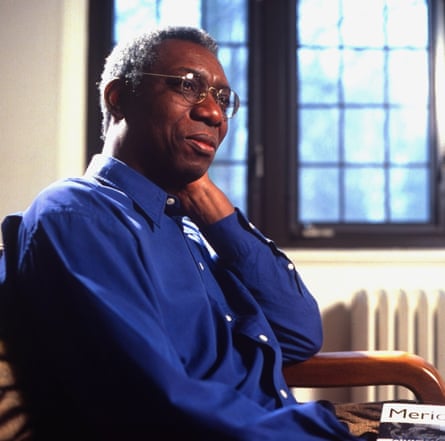

As we come towards the present day, our sense of dilation becomes even greater. Not just in the sense that poets have made far-flung wars visible at home ( Yusef Komunyakaa writing about Vietnam, for instance, or Brian Turner about Iraq), but also because the reporting of wars in the media has encouraged non-combatants to address the subject in greater numbers than ever before. This is a difficult business, since it is all too easy to get caught grandstanding, or parading sensitivities, or seeming to aggrandise oneself by associating with a grand subject. But when it is done well it produces poems that earn the right to sit besides those written by people in uniform: Tony Harrison ’s “A Cold Coming” , for example, or James Fenton ’s “Dead Soldiers”.

Before the first world war, war poetry since time immemorial ( The Iliad ) had been largely concerned to celebrate, commend, remember and, yes, grieve. Think of Lord Byron ’s Assyrian, coming down like a wolf on the fold, or Sir John Moore in Charles Wolfe’s poem about the battle of Corunna . Since 1918, like war itself, the poetry of conflict has become a thing of infinite variety, describing apparently infinite tragedy. Yet for all this – which deserves more acknowledgment than it gets – something has stayed the same. The something Owen meant when he spoke about “the pity”.

- Point of view

- First world war

- Second world war

Most viewed

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.4: The War Poets

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 134628

Learning Objectives

- Understand the effects of World War I on Britain and on the development of Modern literature.

- Recognize the cognitive dissonance caused by accounts of the achievements and victories of the British military and the firsthand accounts of returning individuals and of writers such as the war poets.

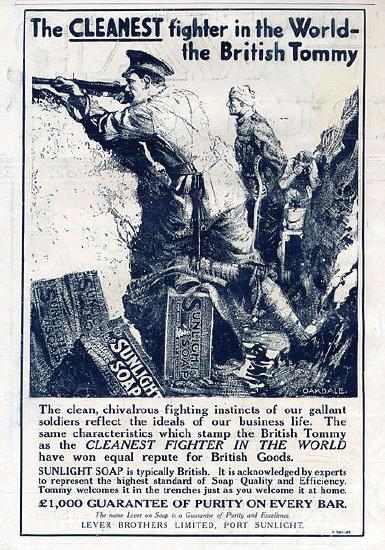

No words could describe the general public’s perception of World War I better than the photo essay at the Modern American Poetry website (Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). In the photo essay note the first pictures of men going off to war, women cheering them on, both sides confident in their abilities and confident that the war would be over within a few months followed by increasingly somber pictures of the reality. The ad pictured here capitalized on the widespread belief that British troops, because they were honorable, chivalrous, gallant, would soon march home in victory. The work of soldier poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Rupert Brooke informed the British public of the realities of war as much as, perhaps more than, the censored journalistic reports that reached British newspapers and magazines. The brutalities of outdated military tactics used against modern weapons resulted in incomparable British losses . The war poets painted vivid pictures of the realities of war.

The BBC provides extensive information about World War I , including virtual tours of the trenches and excerpts from oral histories, diaries, and letters.

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

Wilfred Owen was born in Shropshire, a rural area of England. He was interested in poetry, particularly Keats and other Romantic poets, and wrote poetry in his teens. When he failed to be admitted to college, he moved to France to work as an English language tutor. After World War I began, he moved back to England to enlist. In 1917, he was diagnosed with what was then called shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital in Scotland for treatment. There he met Siegfried Sassoon. Both poets wrote some of their most well-known poetry while there. Owen returned to the front in the fall of 1918, won the Military Cross, and just days before the war ended was killed in battle. His family received the news of his death in the midst of celebrations on November 11, Armistice Day, 1918.

“Dulce et Decorum Est”

The Latin phrase from a work by Homer may be translated “It is sweet and right to die for one’s country.” Juxtaposed against the illusion of war as a glorious adventure, Owen paints the horrors of war’s reality.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori .

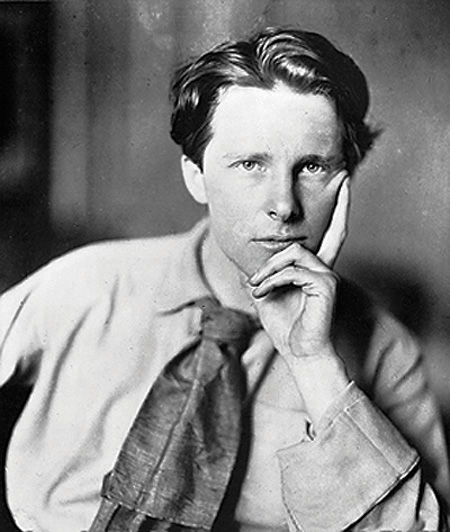

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

Rupert Brooke also was fond of the works of the Romantic poets. He attended Cambridge University where he met and befriended members of the Bloomsbury Group whose literature was an important piece of British modernism. Brooke was commissioned into the Royal Navy, but in 1915 he died of sepsis onboard a hospital ship. He is buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

Rupert Brooke’s grave.

“The Soldier”

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

Although Sassoon grew up in a family divided by religious differences, his father was Jewish, his mother Roman Catholic, his background provided him enough wealth to live comfortably. He attended Cambridge University for a while, without taking a degree, preferring to live the life of a country gentlemen playing cricket and writing. Sassoon joined the British Army at the beginning of World War I; he was sent home from the front twice, once when he contracted a fever and once for shell shock, this being the occasion when he met Wilfred Owen. Sassoon survived World War I and continued writing until his death.

By George Charles Beresford, 1915

“Glory of Women”

Glory of women.

You love us when we’re heroes, home on leave,

Or wounded in a mentionable place.

You worship decorations; you believe

That chivalry redeems the war’s disgrace.

You make us shells. You listen with delight,

By tales of dirt and danger fondly thrilled.

You crown our distant ardours while we fight,

And mourn our laurelled memories when we’re killed.

You can’t believe that British troops “retire”

When hell’s last horror breaks them, and they run,

Trampling the terrible corpses—blind with blood.

_O German mother dreaming by the fire,

While you are knitting socks to send your son

His face is trodden deeper in the mud._

In the last three lines, the speaker turns from addressing the people back home in England to speak to the imagined mother of a German soldier. His comment has the effect of humanizing the political enemy.

Key Takeaways

- The staggering casualties and the horrors of modern warfare contributed to the modernist sense that the world lacks a stable, centralizing force and that life lacks ultimate purpose—that the world we live in is, in the words of Thomas Hardy’s character Tess, a “blighted one.”

- The work of the war poets helped enlighten the public about the nature of the war experience.

- In “Dulce Et Decorum Est” the last stanza is directed to people back at home. What is the purpose of this stanza?

- Read this brief description of the mustard gas used in World War I. Does Owen’s description seem realistic? Which account seems more emotionally based? Which might have had a more profound effect on the people at home away from the war?

- Brooke’s poem “The Soldier” seems brighter in mood and tone than the other two poems, and yet it describes a soldier’s death. What makes the poem less horrific than “Dulce Et Decorum Est”?

- How would you describe the mood of the speaker in “The Soldier”?

- The speaker of “Glory of Women” expresses disillusionment with the supposed glory of war. How would you describe his attitude toward the women back at home?

- In “Glory of Women,” although the Germans are the enemy of the British, what common human trait does the poet reveal?

General Information

- Anthem for Doomed Youth: Writers and Literature of The Great War, 1914–1918. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- The First World War Poetry Digital Archive . University of Oxford and JISC [Joint Information Systems Committee]. text (including biographies, primary texts, background information), images (including portraits, digital images of manuscripts, photos of World War I, images from the Imperial War Museum); audio; video (including a Second Life Virtual Simulation from the Imperial War Museum and a YouTube video introduction , over 150 video clips, film clips), and an interactive timeline.

- “ Home Front: World War One .” British History. BBC.

- “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Wilfred Owen’s ‘ Dulce et Decorum Est .’” Online Gallery. British Library. image of handwritten manuscript and information about Owen and World War I.

- “ World War One .” World Wars. BBC History .

- Poems by Wilfred Owen with an Introduction by Siegfried Sassoon . A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Pennsylvania State University.

- “ Rupert Brooke, 1887–1915 .” “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Rupert Brooke (1887–1915) .” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “ Rupert Chawner Brooke .” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “ Siegfried Sassoon .” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “ Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) .” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “ Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) .” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “ Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) .” “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Wilfred Edward Salter Owen .” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “ 1914 V. The Soldier “ by Rupert Brooke. Representative Poetry Online . Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “ Anthem for Doomed Youth .” by Wilfred Owen. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. text and a digital image of the original handwritten manuscript.

- “ Dulce et Decorum Est .” by Wilfred Owen . Paul Halsall, Fordham University. Internet Modern History Sourcebook .

- “ Dulce et Decorum Est .” by Wilfred Owen. “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Glory of Women .” by Siegfred Sassoon. Counter-Attack and Other Poems . 1918. Bartleby.com .

- “ Glory of Women .” The War Poems of Siegfried Sassoon . Project Gutenberg .

- “ Sonnet V. The Soldier .” by Rupert Brooke. “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Wilfred Owen’s ‘ Dulce et Decorum Est .’” Online Gallery. British Library.

- “ World War I Photo Essay .” Modern American Poetry . Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- “ Dulce et Decorum Est .” by Wilfred Owen. LibriVox .

- Extract from a letter by Wilfred Owen, July 1918 . “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Siegfried Sassoon 1886–1967 ). A Recording Owned by Mrs. Olga Ironside Wood. 1 January 1967. BBC.

- “ The Soldier .” by Rupert Brooke. LibriVox .

- “ Wilfred Owen Audio Gallery .” Dominic Hibberd. World Wars. BBC History .

An Introduction to English War Poetry

The poet’s career doesn’t end once he dies. The soldier’s career arguably does. The poet-soldier, then, has died physically, but what remains of him is his art. Both Edward Thomas and Francis Ledwidge managed to create something that transcended their persons and lasted long after being killed in war.

One of the greatest contributions to modern English poetry came through the works that described World War I, in great part because of WWI’s significance on human history. Poetry written by soldiers is one of the best ways to approach literature on the subject, and it will be the focus of this essay to introduce two war poets, one Englishman and one Irishman, who conveyed the sense of being a soldier in the Great War and, in turn, were transformed by this event. Edward Thomas and Francis Ledwidge were two such poets whose pieces drew upon elements of nature to communicate a soldier’s isolation and his acceptance, even embrace, of imminent death. These two poets were common men, and sometimes within the canon of English and Western literature we may forget that there were talented writers of value even if they did not reach international renown. Many times, it is only through the art of small men that we can understand the impact of the forces that we create and that envelop us as they grow out of control.

Edward Thomas was an English poet born in 1878. He enlisted as a soldier at the age of thirty-seven in 1915 and was killed, after two years of training, on the first day of battle in Arras, France in 1917.[1] Francis Ledwidge, born in 1887, enlisted as a soldier in 1914 at the young age of twenty-seven and was killed three years later in Boezinge, Belgium.[2] Though both of these men wrote several poems inspired by their experiences fighting during the Great War, they were not concerned with the war as a political or controversial topic. In fact, those familiar with war poetry might wonder why I don’t mention better-known WWI poets, like Wilfred Owen. All soldiers were diverse people who understood war differently. Owen had one of the most explicit critiques of war, and I think most of his fame came from that political statement. Take his most famous poem, “Dulce et Decorum Est,” the message of which can be understood from a first reading:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs, And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots, But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time, But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.— Dim through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin; If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,— My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori .

The poem is moving, no doubt, because it is a true depiction of war. Even in his blunt description of battle, Owen manages to describe death in beautiful verse, “Dim through the misty panes and thick green light / As under a green sea, I saw him drowning” (13-14), followed by a nightmarish description of the image that haunts him in his sleep. The moral of the story? It is a lie, that it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country. Owen’s message resonated with many anti-war activists, and this statement is not meant to detract from what is an exceptional poem with intricate literary devices (just read the first two lines out loud! Alliteration, assonance, almost onomatopoeic, making the sound of soldiers marching—amazing). But I do think Owen’s political message has influenced his appreciation as a poet as being more for his message, not for his poetry .

What I prefer about the lesser-known war poets is the humility of their voice, which is more preoccupied with coming to terms with themselves as soldiers, as the helpless victims of circumstance, rather than criticizing the world for what’s happened to them. What Thomas and Ledwidge seemed to understand was that during times of war wherein a soldier found himself lost and alone, it was man’s relationship with himself that took priority over everything else. While the spirit of the soldier who sacrifices himself for others is revered, I do believe that, internally, what took place in the minds of these soldiers was a necessary form of isolation that turned into self-reflection. This excerpt of a letter from Ledwidge to a woman named Katherine conveys a similar sentiment to Owen’s poem, but in a very different tone:

If I survive the war, I have great hopes of writing something that will live. If not, I trust to be remembered in my own land for one or two things which its long sorrow inspired… You ask me what I am doing. I am a unit in the Great War, doing and suffering… I may be dead before this reaches you, but I will have done my part… I am always homesick. I hear the roads calling, and the hills, and the rivers wondering where I am. It is terrible to always be homesick. —Francis Ledwidge, Letter to Katherine Tynan, dated 6 January 1917 .[3]

It is not poetry, of course, but it was written by a poet. Notice how Ledwidge says that if he “survives,” he wants to write something that will “live.” He does not use the word “live” for himself, although we usually say, “if I live.” It is almost as though Ledwidge is recognizing that he’s already lost a part of himself. Ledwidge viewed himself as a “unit,” just going through the motions of what needed to be done. It was not on the battlefield or while doing his duty as a soldier, then, that the individual fighter contemplated himself. Their relationship with the self, then, was the solution to their loneliness and feeling of insignificance.

The machinery used during the Great War meant that infantry combat was only a secondary resource in battle, and this change in weaponry prevented the individual soldier from playing a direct part in this industrialized war.[4] People’s belief in a heroic image of one body of men fighting arm in arm was shattered upon realizing that soldiers were dying undignified and by the thousands. The question then became, what was a singular man’s place amidst such mass destruction? Truly, his identity was overcome by an agglomerate of soldiers who were treated as objects. What “greater” sense of himself could the soldier contribute to a cause devoid of greatness?

For Edward Thomas and Francis Ledwidge, the way that they contemplated their place and themselves was through their poetry, and nature was an integral part of this relationship because it was a direct way for them to envision home. Since home was seldom in proximity for the soldier, it can be deduced that he often resorted to his immediate surroundings to find comfort and reassurance. Both Thomas and Ledwidge developed this sort of companionship with nature.

Nature’s characteristic as an ongoing duality between life and death, the beauty of creation and destruction, bore resemblance to what they were experiencing on a daily basis, and they perceived it, therefore, as a reflection of their own lives. Thomas and Ledwidge did not solely use nature in their poetry to recount their personal experiences, however, but they also used it to create a space of recognition for the individual faceless soldier as a method of remembrance. They used the symbol of a grave to manifest this sentiment.

The Grave Symbolic for Death and Life

Since there were no number of graves that would suffice for the number of casualties in the Great War, the grave as it was used by these two poets is a symbol for what it represents. In the case of Edward Thomas, the grave as a symbol of remembrance was more important than the physical tombstone. He did not mention graves in his poems, nor did he describe or reference them. Thomas’ focus on the grave was on the writings that would commonly go on the tombstone, and he replicated them in lyrical structure and form in his verses. This elegiac form, often meant for epitaphs, is common in several of his poems.[5] Thomas saw a contrast with epitaphs since they represented what was fixed but also what was transcendent, and he even attributed a literary value to them.[6] An example of such a poem is titled, “In Memoriam (Easter 1915)”:

The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood This Eastertide call into mind the men, Now far from home, who, with their sweethearts, should Have gathered them and will never do again. (1-4)

This poem, written in iambic pentameter with an alternating end-rhyme, is typical of an elegiac stanza, which is a fitting style based on the content of Thomas’ piece since it is a poem of remembrance for the men who left for war and did not return. Nature is immediately invoked when Thomas mentions the flowers “left thick at nightfall in the wood” (1) that should have been gathered by the young soldiers and their sweethearts. Thomas acknowledges that seeing the life of the flowers that have not been picked calls to mind the death of the soldiers: the presence of one thing represents the absence of another.

Thomas used the flower as a symbol of both remembrance and impermanence to recall the past, note the present, and contemplate the future. The importance of nature in the poem might be further stressed upon considering that Thomas used un-plucked flowers in the woods as the main subject. It is only upon seeing the flowers that he is reminded of the dead soldiers. Rather than addressing the dead soldiers directly, Thomas prefers to invoke them through nature even though the poem, as the title expresses, is meant to be an elegy or epitaph of some sort for the men who died in war.

Another poem that expresses this notion of the grave as a point of convergence for death and life is “A Soldier’s Grave” by Francis Ledwidge. It bears some similarity to “In Memoriam (Easter 1915)” since flowers are also mentioned and used as a symbol of remembrance, but the flowers are only secondary to the greater symbol that is the actual earth-grave, which is the main subject of the poem. Here, however, the grave is one with nature, or, rather, the grave is a platform for nature:

And where the earth was soft for flowers we made A grave for him that he might better rest. So, Spring shall come and leave it sweet arrayed, And there the lark shall turn her dewy nest (5-8)

Spring is personified to depict a regenerating force that will decorate the soldier’s grave with different forms of life. A grave was made where “the earth was soft” (5), and spring will use this ground as its stage to grow new flowers and attract birds to lay their nests (8). In the context of this poem, death relieves the soldier from his burdens and even results in beauty and harmony as nature pushes the cycle forward, thus demonstrating that time continues to pass as one life ends by turning the soldier’s resting place into a display of new life. Both poets console the horrors of war with the beauty of nature and portray nature as playing an active role in death and life. By attributing these characteristics to nature, Thomas and Ledwidge are displaying self-awareness in their role as a soldier. They hint, likewise, at their acceptance of death since their poems display a similar disposition towards mortality, where the thought of dying comes no longer as a fear, but as a part of nature.

The Notion of “Passing” as Nature

Francis Ledwidge was able to depict nature as serene and personify it as a force of aid for the dying soldier. We can further analyze his poem “A Soldier’s Grave” and look at the first stanza to corroborate this point:

Then in the lull of midnight, gentle arms Lifted him slowly down the slopes of death Lest he should hear again the mad alarms Of battle, dying moans, and painful breath (1-4)

With his opening line, Ledwidge immediately assumes a narrative tone, which serves to calm the reader since the poet sounds like he is telling a pleasant story that is taking place in a tranquil setting, “the lull of midnight” (1). The simple alternating end-rhyme scheme enhances this emotion as each stanza concludes in such a way that sounds complete, and the word-choice (lull, gentle, lifted, slowly) reassures the reader that what is happening to the soldier is a good thing rather than a negative one. In terms of the story that Ledwidge is telling, an unknown entity is introduced whose role is to ease the soldier’s passing and carry him peacefully towards death: But the reader is not told who or what it is; it is simply described as “gentle arms” (1). Though it might be difficult to infer who or what the gentle arms refer to, Ledwidge seems to imply that the entity is a gracious and sympathetic one since it is taking the soldier away from “the mad alarms of battle, dying moans, and painful breath” (3-4).

Francis Ledwidge briefly mentioned the journey from life towards death in “A Soldier’s Grave” when he describes the soldier being lifted down death’s slopes (2). Edward Thomas elaborated on this journey to a greater extent in “Lights Out,” which was written by Thomas in 1916 just before going to war.[7] The poem is about the process of dying, and he describes this gradual passing, which he calls a sleep, by relating it to walking in a forest. The presence of nature here plays a distinct role: It is no longer a kind and sympathetic force as Ledwidge portrayed in his poem; rather, Thomas depicts it as intense and inescapable:

I have come to the borders of sleep, The unfathomable deep Forest where all must lose Their way, however straight, Or winding, soon or late; They cannot choose.

Many a road and track That, since the dawn’s first crack, Up to the forest brink, Deceived the travelers, Suddenly now blurs, And in they sink. (1-12)

Nature, here in the form of a forest, is bottomless; if sleep were a land, Thomas describes the borders of this realm as abysmal since he chooses to break the sentence at a moment where the sentence reads, “I have come to the borders of sleep / The unfathomable deep…” (1-2) It is only after continuing the poem that Thomas reveals a forest that is inevitable; “where all must lose their way, however straight or winding, soon or late; they cannot choose” (3-6). Considering the conditions and timing under which Thomas wrote this poem, prior to going to war and a year before his death, we can assume that Thomas used sleep to refer to death and the forest as a metaphor for the passing. The two symbols of sleep and the forest combined emphasize the inevitability of death since Thomas explains that everyone will eventually succumb to this sleep regardless of the path they take. All the roads and tracks that “deceived” travelers, perhaps into thinking death would not come for them, blur at the forest brink. That forest is a whole wherein they sink: A deep sleep.

Nature, in this respect, has tricked and captured the traveler wandering through the forest, which might cause the reader to view nature as a negative force. The subsequent stanzas, however, rectify this false assumption as Thomas defends the forest as being a neutral place where all emotion is distilled and where the traveler can rid himself of all earthly cares:

Here love ends, Despair, ambition ends; All pleasure and all trouble, Although most sweet or bitter, Here ends in sleep that is sweeter Than tasks most noble.

There is not any book Or face of dearest look That I would not turn from now To go into the unknown I must enter, and leave, alone, I know now how. (13-24)

It is interesting to note that Thomas describes death as neither good nor bad: both pleasure and trouble end, both love and despair (1-3). The fourth stanza in the poem indicates a type of personal relief in death that is incomparable to any worldly joy. “Face” (20) in this context represents any family or friend that would normally keep Thomas from dying, while “book” (19) might be a symbol for any moral, intellectual, or philosophical code of ethics that might make a man believe that it is better to continue living. Alternatively, it could be a metaphorical representation of literature and of Thomas’ potential career as a literary figure, since he was a well-reputed writer and book reviewer before he enlisted in the army. Thomas determines, nonetheless, that neither will stop him from entering the unknown.

In the fifth and final stanza of the poem, Thomas returns to his nature imagery and completes a cycle not only in the mechanical structure of the poem as he brings back the image of the forest, but also in a metaphorical sense since he concludes by expressing the embrace of death as a release from the self and a unification with nature:

The tall forest towers; Its cloudy foliage lowers Ahead, shelf above shelf; Its silence I hear and obey That I may lose my way And myself. (25-30)

There is a clear contradiction when Thomas states that he is able to “hear” (28) the forest’s silence and that this absence of sound is what persuades him to obey it. It is as though the forest did not need to do anything to convince Thomas to comply; rather, the impulse to follow it comes intuitively and subconsciously. While the forest seems to overpower Thomas as “its cloudy foliage lowers” (26) over him and beckons him to venture deeper, Thomas simultaneously displays free will and choice by acknowledging the fact that in so doing he will lose his path in the forest and ultimately himself (30). The facts that Thomas senses an invitation from the forest, that he understands what he must do without the need for an audible command or signal, and that he is well aware of the consequences, serve to support the idea that he views passing to be almost instinctive and part of nature.

By placing such an emphasis on dying while concurrently using nature as a metaphor and analogy to describe the process, Thomas and Ledwidge affirm an instinctual connection between their deaths and their environment. For both of these poets, the transience of nature was a way to understand and justify their role as a soldier likely to die at any moment. Thomas’ poem opens the important subject of English WWI poetry: the self.

The “Self” and Individual Life

Although the previous poems might insinuate that Thomas and Ledwidge had accepting dispositions towards death, they wrote other poems on the matter that conflicted with the notion of them having one view of death. The thought of death might have served as alleviation for these poets, but it did not resolve many questions in regard to their place amidst the Great War, after all. Their poetry was the attempt to validate the life and death of the soldier more than it was an outward critique on war. Thomas and Ledwidge placed a heavy importance on the “self” and the individual life of the soldier as he lived and suffered the war, for this experience tremendously affected his perception of the world, of life, and of death. From the traumatizing events that they endured, an existential question correspondingly arose and troubled the soldier’s mind: were his efforts and his death justified? Would he ever have recompense for his efforts, even after death? Francis Ledwidge addressed these questions in one of his most famous poems, “Lament for Thomas MacDonagh.” MacDonagh was a revolutionary leader during the 1916 Easter Rising who was executed by the British Army.[8] Ledwidge wrote a poem in his honor where he revealed his thoughts on the individual who sacrificed his life and died for a greater cause:

He shall not hear the bittern cry In the wild sky where he is lain Nor voices of the sweeter birds Above the wailing of the rain

Nor shall he know when loud March blows Thro’ slanting snows his fanfare shrill Blowing to flame the golden cup Of many an upset daffodil (1-8)

The opening stanza bears some resemblance to Thomas’ poem, “Lights Out” in the sense that Ledwidge is describing death indifferently as a state of neither pain nor happiness: Ledwidge states that MacDonagh will hear neither “the bittern cry” (1) nor the sounds of “the sweeter birds” (3). MacDonagh, moreover, will not be able to witness the winter: “Nor shall he know when loud March blows / Thro’ slanting snows his fanfare shrill” (5-6). Ledwidge strengthens this sentiment by using words like “wild” (2) to describe the sky, and the winter and the rain as cacophonous with their “wailing” (4) and “shrill” (6). This desolate landscape depicts nature as harsh, destructive, and violent as the winter “blows to flame” (7) the golden cups of daffodils.

The first two stanzas paint a bleak landscape to reflect how Ledwidge feels about the death of Thomas MacDonagh as he uses words such as “upset” (8) and “bittern” (1) to further emphasize his discontent. Through these statements, Ledwidge addresses the existential question of the life and soul of a man after death, but he seems to lean towards the opinion that MacDonagh is completely gone. It isn’t until the third stanza that Ledwidge introduces a hesitation, providing an optimistic and alternative view to MacDonagh’s untimely death:

But when the Dark Cow leaves the moor And pastures poor with greedy weeds Perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn Lifting her horns in pleasant meads (8-12)

Ledwidge continues to describe the landscape in a negative form, “pastures poor with greedy weeds” (9). This adjective choice for the weeds implies that there is some sort of corruption occurring on this field, which perhaps is a reference to the political instability occurring in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rebellion, since it was during this event that MacDonagh died (again, history is vital for good poetry writing and study). This negative landscape is reconciled once Ledwidge inserts an important shift by introducing the Dark Cow leaving this field. The “Dark Cow” (8) that Ledwidge foresees eventually leaving the moor is turned into a proper noun, which supports the idea that the cow is a metaphor for his country and Ledwidge’s way of optimistically expressing the possibility of Ireland overcoming its tumultuous state.

The most important lines in the poem are the final two where Ledwidge readdresses the question of MacDonagh’s death by considering the possibility that, if and once Ireland overcomes its strife, MacDonagh will be able to see (even from beyond the grave) his country prosper once again. Ledwidge achieves this optimistic shift by using the key word “perhaps” (11) to state that MacDonagh will be able to hear the Dark Cow (that is, Ireland) and see her “lifting her horns in pleasant meads” (12), an image of triumph and pride. This gesture that Ledwidge attributes to the cow not only reveals his hopes for Ireland, but also his feelings towards MacDonagh’s death: By being able to hear the cow upon lifting her horns, MacDonagh’s senses are restored and his memory, therefore, brought back to life.

Ledwidge’s interest in the soul of Thomas MacDonagh reveals his own personal curiosity regarding the soul of the individual before and after death. Edward Thomas also addressed this issue in his poem, “Rain,” by questioning this same subject and placing emphasis on the senses to express the possibility of the self ceasing to exist after death:

Rain, midnight rain, nothing but the wild rain On this bleak hut, and solitude, and me Remembering again that I shall die And neither hear the rain nor give it thanks For washing me cleaner than I have been Since I was born into solitude. (1-6)

The prominence and repetition of the word “rain” in the first line replicates the rhythm of raindrops, which implies that Thomas is actively listening to the rain and is therefore in a state of deep contemplation. The third line of the poem reveals that Thomas is thinking about his death; yet, it is not his death that is troubling him, but rather the notion of losing his senses and, therefore, of losing himself.

Francis Ledwidge wrote a similar poem titled “Soliloquy,” in which he assesses the importance of being a soldier and the probability of dying. The poem opens with a reflection on his youth and progresses chronologically with him through the years. The third stanza is the break in the poem where his thoughts come back to the present moment:

And now I’m drinking wine in France, The helpless child of circumstance. Tomorrow will be loud with war, How will I be accounted for? (15-18)

By questioning what will happen if he dies, Ledwidge acknowledges the risk he runs of potentially being killed; yet, in the last stanza of his poem, he seems to dispose of this worry by glorifying himself as a soldier:

It is too late now to retrieve A fallen dream, too late to grieve A name unmade, but not too late To thank the gods for what is great; A keen-edged sword, a soldier’s heart, Is greater than a poet’s art. And greater than a poet’s fame A little grave that has no name. (19-26)

Ledwidge refers to himself indirectly when he states, “A keen-edged sword, a soldier’s heart / Is greater than a poet’s art” (23-24). He adds, “And greater than a poet’s fame” (25) is “a little grave that has no name” (26). This statement seems to contradict the aforementioned letter he sent to Katherine Tynan expressing how he hoped to live and become a great poet. Is he being sarcastic? It is difficult to say.

Within these poems, Thomas and Ledwidge make clear that their words are more than a mere expression of observations and recounting of events as soldiers in the Great War. Their quest was more profound, directed inwards towards themselves and less directed towards their audience.

The Great Grave

The poet’s career doesn’t end once he dies. The soldier’s career arguably does. The poet-soldier, then, has died physically, but what remains of him (as Ledwidge noted in his letter) is his art. There was, however, a certain inhumanity about the way soldiers’ deaths were regarded.

Since both poets managed to create something that transcended their persons and lasted long after being killed in war, their absence was not necessarily detrimental to the poetry itself. But what of that part of them that was a mere soldier, a unit in the war? The day that Ledwidge was killed, for example, the chaplain recorded his death as follows:

Crowds at Holy Communion. Arrange for service but washed out by rain and fatigues. Walk in rain with dogs. Ledwidge killed, blown to bits; at Confession yesterday and Mass and Holy Communion this morning. R.I.P.[9]

Ledwidge’s collection of poems titled “Songs of Peace” was published in September 1916, three months after his death, under the description of a “Soldier Poet Fallen in the War.”[10] This image rendered him as an epitome of the brave soldier, and it seems that the soldier brand stuck with him more than the poet part. But although this image was a kind way of portraying him to a greater cause—the fallen soldier—it set aside Francis Ledwidge’s identity as an individual who experienced the world (or which war was the last part). A contemporary poet at the time, John Drinkwater, was one of the few who refuted how Ledwidge’s death was portrayed to people, which he believed to be insulting. In regards to Ledwidge’s death, he wrote:

The continual insistence, not that his devotion is splendid, but that it is upon us that his devotion may splendidly bestow itself, is contemptible… his poetry exults me, while not so his death. And it is well for us to keep our minds fixed on this plain fact, that when he died, a poet was not transfigured, but killed, and his poetry was not magnified, but blasted in its first flowering.[11]

As Drinkwater observed, death, despite being a source of influence for many of his poems, managed to abruptly halt what would have been a promising career for Ledwidge. This is a problem that is difficult to overcome: What role does strife play for the artist? Pain and suffering may help him develop his art, but at what cost? Although he enlisted voluntarily, the setting in which he died was artificially created; the way his death was recorded, almost absurd.

There are only some of the questions that come to me when I read war poetry, but it is a great genre in poetry that merits more study beyond this (very short) introduction. The most fitting way to conclude this essay is with one more poem by Ledwidge. The bucolic poem, “Behind The Closed Eye,” describes what Ledwidge understood to be his personal encounter with death: A return home, to Ireland.

I walk the old frequented ways That wind around the tangled braes, I live again the sunny days Ere I the city knew.

And scenes of old again are born, The woodbine lassoing the thorn, And drooping Ruth-like in the corn The poppies weep the dew.

Above me in their hundred schools The magpies bend their young to rules, And like an apron full of jewels The dewy cobweb swings.

And frisking in the stream below The troutlets make the circles flow, And the hungry crane doth watch them grow As a smoker does his rings.

Above me smokes the little town, With its whitewashed walls and roofs of brown And its octagon spire toned smoothly down As the holy minds within.

And wondrous impudently sweet, Half of him passion, half conceit, The blackbird calls adown the street Like the piper of Hamelin.

I hear him, and I feel the lure Drawing me back to the homely moor, I’ll go and close the mountains’ door On the city’s strife and din.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now .

1 Biography of Edward Thomas by Poets.org .

2 Francis Ledwidge Museum .

3 Alice Curtayne, Francis Ledwidge, A Life of the Poet , (Dublin: New Island Books, 1998.) 170.

4 Helen B. McCartney, “The First World War Soldier and his contemporary image in Britain,” International Affairs , Feb. 2014: 299.

5 Move Him Into the Sun .

6 Judy Kendall, Edward Thomas: Origins of His Poetry (LLandybïe: University of Wales Press, 2012), 57.

7 Wojciech Klepuszewski, “ ‘Lights Out’: Edward Thomas on the Way to War ,” Revue LISA/LISA e-journal , Mar. 2012, 69-82.

8 Thomas Macdonagh Heritage Centre

9 Alice Curtayne, Francis Ledwidge, A Life of the Poet (Dublin: New Island Books, 1998) 188.

10 Ibid. 190.

11 Ibid. 191.

Editor’s note: The featured image is a battle scene which depicts the bravery of Alvin C. York, one of the most decorated United States Army soldiers of World War I, (1919 ) by Frank Schoonover (1877-1972), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons .

All comments are moderated and must be civil, concise, and constructive to the conversation. Comments that are critical of an essay may be approved, but comments containing ad hominem criticism of the author will not be published. Also, comments containing web links or block quotations are unlikely to be approved. Keep in mind that essays represent the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Imaginative Conservative or its editor or publisher.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: nayeli riano.

Related Posts

Resurrection in Narnia

Tolkien’s Easter Joy in “The Lord of the Rings”

Easter Wings

A Sonnet for Easter Dawn

Good Friday: The First 12 Stations of the Cross

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Great War Poems

From antiquity through the nuclear age, poets respond to human conflict

Apic / Getty Images

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Jackie-Craven-ThoughtCo-58eeac613df78cd3fc7a495c.jpg)

- Doctor of Arts, University of Albany, SUNY

- M.S., Literacy Education, University of Albany, SUNY

- B.A., English, Virginia Commonwealth University

War poems capture the darkest moments in human history, and also the most luminous. From ancient texts to modern free verse, war poetry explores a range of experiences, celebrating victories, honoring the fallen, mourning losses, reporting atrocities, and rebelling against those who turn a blind eye.

The most famous war poems are memorized by school children, recited at military events, and set to music. However, great war poetry reaches far beyond the ceremonial. Some of the most remarkable war poems defy expectations of what a poem "ought" to be. The war poems listed here include the familiar, the surprising, and the disturbing. These poems are remembered for their lyricism, their insights, their power to inspire, and their role chronicling historic events.

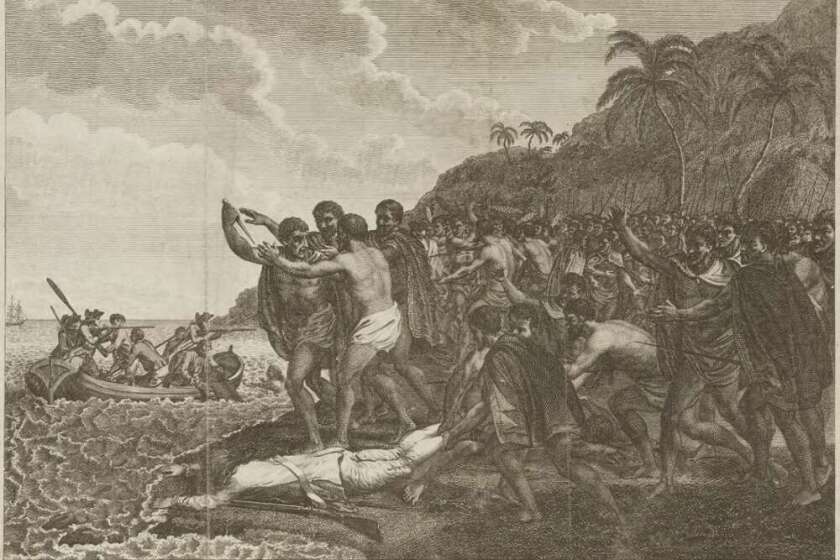

War Poems from Ancient Times

British Museum Collection. CM Dixon / Print Collector / Getty Images

The earliest recorded war poetry is thought to be by Enheduanna, a priestess from Sumer, the ancient land that is now Iraq. In about 2300 BCE, she riled against war, writing:

You are blood rushing down a mountain, Spirit of hate, greed and anger, dominator of heaven and earth!

At least a millennium later, the Greek poet (or group of poets) known as Homer composed The Illiad , an epic poem about a war that destroyed "great fighters' souls" and "made their bodies carrion, / feasts for the dogs and birds."

The celebrated Chinese poet Li Po (also known as Rihaku, Li Bai, Li Pai, Li T’ai-po, and Li T’ai-pai) raged against battles he viewed as brutal and absurd. " Nefarious War ," written in 750 AD, reads like a modern-day protest poem:

men are scattered and smeared over the desert grass, And the generals have accomplished nothing.

Writing in Old English , an unknown Anglo Saxon poet described warriors brandishing swords and clashing shields in the " Battle of Maldon ," which chronicled a war fought 991 AD. The poem articulated a code of heroism and nationalist spirit that dominated war literature in the Western world for a thousand years.

Even during the enormous global wars of the 20th century, many poets echoed medieval ideals, celebrating military triumphs and glorifying fallen soldiers.

Patriotic War Poems

When soldiers head to war or return home victorious, they march to a rousing beat. With decisive meter and stirring refrains, patriotic war poems are designed to celebrate and inspire.

“ The Charge of the Light Brigade ” by English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892) bounces with the unforgettable chant, “Half a league, half a league, / Half a league onward.”

American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) wrote " Concord Hymn " for an Independence Day celebration. A choir sang his rousing lines about "the shot heard round the world” to the popular tune "Old Hundredth."

Melodic and rhythmic war poems are often the basis for songs and anthems. " Rule, Britannia! ” began as a poem by James Thomson (1700–1748). Thomson ended each stanza with the spirited cry, "Rule, Britannia, rule the waves; / Britons never will be slaves." Sung to music by Thomas Arne, the poem became standard fare at British military celebrations.

American poet Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910) filled her Civil War poem, “ Battle Hymn of the Republic ,” with heart-thumping cadences and Biblical references. The Union army sang the words to the tune of the song, “John Brown’s Body.” Howe wrote many other poems, but the Battle-Hymn made her famous.

Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) was an attorney and amateur poet who penned the words that became the United States national anthem. “The Star-Spangled Banner” does not have the hand clapping rhythm of Howe’s “Battle-Hymn,” but Key expressed soaring emotions as he observed a brutal battle during the War of 1812 . With lines that end with rising inflection (making the lyrics notoriously difficult to sing), the poem describes “bombs bursting in air” and celebrates America’s victory over British forces.

Originally titled “The Defence of Fort McHenry,” the words (shown above) were set to a variety of tunes. Congress adopted an official version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as America's anthem in 1931.

Soldier Poets

Historically, poets were not soldiers. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Butler Yeats, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thomas Hardy, and Rudyard Kipling suffered losses, but never participated in armed conflict themselves. With very few exceptions, the most memorable war poems in the English language were composed by classically-trained writers who observed war from a position of safety.

However, World War I brought a flood of new poetry by soldiers who wrote from the trenches. Enormous in scope, the global conflict stirred a tidal wave of patriotism and an unprecedented call to arms.Talented and well-read young people from all walks of life went to the front lines.

Some World War I soldier poets romanticized their lives on the battlefield, writing poems so touching they were set to music. Before he sickened and died on a navy ship, English poet Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) wrote tender sonnets like " The Soldier ." The words became the song, "If I Should Die":

If I should die, think only this of me: That there’s some corner of a foreign field That is for ever England.

American poet Alan Seeger (1888–1916), who was killed in action serving the French Foreign Legion, imagined a metaphorical “ Rendezvous with Death ”:

I have a rendezvous with Death At some disputed barricade, When Spring comes back with rustling shade And apple-blossoms fill the air—

Canadian John McCrae (1872–1918) commemorated the war dead and called for survivors to continue the fight. His poem, In Flanders Fields , concludes:

If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.

Other soldier poets rejected romanticism . The early 20th century brought the Modernism movement when many writers broke from traditional forms. Poets experimented with plain-spoken language, gritty realism, and imagism .

British poet Wilfred Owen (1893-1918), who died in battle at age 25, did not spare the shocking details. In his poem, “ Dulce et Decorum Est ,” soldiers trudge through sludge after a gas attack. A body is flung onto a cart, “white eyes writhing in his face.”

“My subject is War, and the pity of War,” Owen wrote in the preface to his collection.“The Poetry is in the pity.”

Another British soldier, Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), wrote angrily and often satirically about War War I and those who supported it. His poem “ Attack ” opens with a rhyming couplet:

At dawn the ridge emerges massed and dun In the wild purple of the glow'ring sun, and concludes with the outburst: O Jesus, make it stop!

Whether glorifying war or reviling it, soldier poets often discovered their voices in the trenches. Struggling with mental illness, British composer Ivor Gurney (1890-1937) believed that World War I and camaraderie with fellow soldiers made him a poet. In " Photographs ," as in many of his poems, the tone is both grim and exultant:

Lying in dug-outs, hearing the great shells slow Sailing mile-high, the heart mounts higher and sings.

The soldier poets of World War I changed the literary landscape and established war poetry as a new genre for the modern era. Combining personal narrative with free verse and vernacular language, veterans of World War II, the Korean War, and other 20th century battles and wars continued to report on trauma and unbearable losses.

To explore the enormous body of work by soldier poets, visit the War Poets Association and the The First World War Poetry Digital Archive .

Poetry of Witness

Fototeca Storica Nazionale / Gilardi / Getty Images

American poet Carolyn Forché (b. 1950) coined the term poetry of witness to describe painful writings by men and women who endured war, imprisonment, exile, repression, and human rights violations. Poetry of witness focuses on human anguish rather than national pride. These poems are apolitical, yet deeply concerned with social causes.

While traveling with Amnesty International, Forché witnessed the outbreak of civil war in El Salvador . Her prose poem, " The Colonel ," draws a surreal picture of a real encounter:

He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there.

Although the term “poetry of witness” has recently stirred keen interest, the concept is not new. Plato wrote that it is the poet's obligation to bear witness, and there have always been poets who recorded their personal perspectives on war.

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) documented horrifying details from the American Civil War, where he served as a nurse to more than 80,000 sick and wounded. In " The Wound-Dresser " from his collection, Drum-Taps, Whitman wrote:

From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand, I undo the clotted lint, remove the slough, wash off the matter and blood…

Traveling as a diplomat and an exile, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904-1973) became known for his gruesome yet lyrical poetry about the "pus and pestilence" of the Civil War in Spain.

Prisoners in Nazi concentration camps documented their experiences on scraps that were later found and published in journals and anthologies.The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum maintains an exhaustive index of resources for reading poems by holocaust victims .

Poetry of witness knows no boundaries. Born in Hiroshima, Japan, Shoda Shinoe (1910-1965) wrote poems about the devastation of the atomic bomb. Croatian poet Mario Susko (1941- ) draws images from the war in his native Bosnia. In " The Iraqi Nights ," poet Dunya Mikhail (1965- ) personifies war as an individual who moves through life stages.

Websites like Voices in Wartime and the War Poetry Website have an outpouring of first-hand accounts from many other writers, including poets impacted by war in Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Kosovo, and Palestine.

Anti-War Poetry

John Bashian / Getty Images

When soldiers, veterans, and war victims expose disturbing realities, their poetry becomes a social movement and an outcry against military conflicts. War poetry and poetry of witness move into the realm of anti -war poetry.

The Vietnam War and military action in Iraq were widely protested in the United States. A group of American veterans wrote candid reports of unimaginable horrors. In his poem, " Camouflaging the Chimera ," Yusef Komunyakaa (1947- ) depicted a nightmarish scene of jungle warfare:

In our way station of shadows rock apes tried to blow our cover, throwing stones at the sunset. Chameleons crawled our spines, changing from day to night: green to gold, gold to black. But we waited till the moon touched metal...

Brian Turner's (1967- ) poem " The Hurt Locker " chronicled chilling lessons from Iraq:

Nothing but hurt left here. Nothing but bullets and pain... Believe it when you see it. Believe it when a twelve-year-old rolls a grenade into the room.

Vietnam veteran Ilya Kaminsky (1977- ) wrote a scathing indictment of American apathy in " We Lived Happily During the War ":

And when they bombed other people’s houses, we protested but not enough, we opposed them but not enough. I was in my bed, around my bed America was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house.

During the 1960s, the prominent feminist poets Denise Levertov (1923-1997) and Muriel Rukeyser (1913-1980) mobilized top-name artists and writers for exhibitions and proclamations against the Vietnam War. Poets Robert Bly (1926- ) and David Ray (1932- ) organized anti-war rallies and events that drew Allen Ginsberg , Adrienne Rich , Grace Paley , and many other famous writers.

Protesting American actions in Iraq, Poets Against the War launched in 2003 with a poetry reading at the White House gates. The event inspired a global movement that included poetry recitations, a documentary film, and a website with writing by more than 13,000 poets.

Unlike historical poetry of protest and revolution , contemporary anti-war poetry embraces writers from a broad spectrum of cultural, religious, educational, and ethnic backgrounds. Poems and video recordings posted on social media provide multiple perspectives on the experience and impact of war. By responding to war with unflinching detail and raw emotion, poets around the world find strength in their collective voices.

Sources and Further Reading

- Barrett, Faith. To Fight Aloud Is Very Brave : American Poetry and the Civil War. University of Massachusetts Press. Oct. 2012.

- Deutsch, Abigail. “100 Years of Poetry: The Magazine and War.” Poetry magazine. 11 Dec. 2012. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69902/100-years-of-poetry-the-magazine-and-war

- Duffy, Carol Ann. “Exit wounds.” The Guardian . 24 Jul 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/jul/25/war-poetry-carol-ann-duffy

- Emily Dickinson Museum. “Emily Dickinson and the Civil War.” https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/civil_war

- Forché, Carolyn. “Not Persuasion, But Transport: The Poetry of Witness.” The Blaney Lecture, presented at Poets Forum in New York City. 25 Oct. 2013. https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/not-persuasion-transport-poetry-witness

- Forché, Carolyn and Duncan Wu, editors. Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500 – 2001. W. W. Norton & Company; 1st edition. 27 Jan. 2014.

- Gutman, Huck. "Drum-Taps," essay in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia . J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings, eds. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998. https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_83.html

- Hamill, Sam; Sally Anderson; et. al., editors. Poets Against the War . Nation Books. First Edition. 1 May 2003.

- King, Rick, et. al. Voices in Wartime . Documentary Film: http://voicesinwartime.org/ Print anthology: http://voicesinwartime.org/voices-wartime-anthology

- Melicharova, Margaret. "Century of Poetry and War." Peace Pledge Union. http://www.ppu.org.uk/learn/poetry/

- Poets and War . http://www.poetsandwar.com/

- Richards, Anthony. "How First World War poetry painted a truer picture." The Telegraph . 28 Feb 2014. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-one/inside-first-world-war/part-seven/10667204/first-world-war-poetry-sassoon.html

- Roberts, David, Editor. War “Poems and Poets of Today.” The War Poetry Website. 1999. http://www.warpoetry.co.uk/modernwarpoetry.htm

- Stallworthy, Jon. The New Oxford Book of War Poetry . Oxford University Press; 2nd edition. 4 Feb. 2016.

- University of Oxford. The First World War Poetry Digital Archive. http://ww1lit.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/

- War Poets Association. http://www.warpoets.org/

FAST FACTS: 45 Great Poems About War

- All the Dead Soldiers by Thomas McGrath (1916–1990)

- Armistice by Sophie Jewett (1861–1909)

- Attack by Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967)

- Battle Hymn of the Republic (original published version) by Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910)

- Battle of Maldon by anonymous, written in Old English and translated by Jonathan A. Glenn

- Beat! Beat! Drums! by Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

- Camouflaging the Chimera by Yusef Komunyakaa (1947- )

- The Charge of the Light Brigade by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)

- City That Does Not Sleep by Federico García Lorca (1898–1936), translated by Robert Bly

- The Colonel by Carolyn Forché (1950- )

- Concord Hymn by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882)

- The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner by Randall Jarrell (1914-1965)

- The Dictators by Pablo Neruda (1904-1973), translated by Ben Belitt

- Driving through Minnesota during the Hanoi Bombings by Robert Bly (1926- )

- Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold (1822–1888)

- Dulce et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen (1893-1918)

- Elegy for a Cave Full of Bones by John Ciardi (1916–1986)

- Facing It by Yusef Komunyakaa (1947- )

- First They Came For The Jews by Martin Niemöller

- The Hurt Locker by Brian Turner (1967- )

- I Have a Rendezvous with Death by Alan Seeger (1888–1916)

- The Iliad by Homer (circa 9th or 8th century BCE), translated by Samuel Butler

- In Flanders Fields by John McCrae (1872-1918)

- The Iraqi Nights by Dunya Mikhail (1965- ), translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid

- An Irish Airman foresees his Death by William Butler Yeats (1865–1939)

- I Sit and Sew by Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson (1875–1935)

- It Feels A Shame To Be Alive by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

- July 4th by May Swenson (1913–1989)

- The Kill School by Frances Richey (1950- )

- Lament to the Spirit of War by Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE)

- LAMENTA: 423 by Myung Mi Kim (1957- )

- The Last Evening by Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), translated by Walter Kaschner

- Life at War by Denise Levertov (1923–1997)

- MCMXIV by Philip Larkin (1922-1985)

- Mother and Poet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

- Nefarious War by Li Po (701–762), translated by Shigeyoshi Obata

- A Piece of Sky Without Bombs by Lam Thi My Da (1949- ), translated by Ngo Vinh Hai and Kevin Bowen

- Rule, Britannia! by James Thomson (1700–1748)

- The Soldier by Rupert Brooke (1887-1915)

- The Star-Spangled Banner by Francis Scott Key (1779-1843)

- Tankas by Shoda Shinoe (1910-1965)

- We Lived Happily During the War by Ilya Kaminsky (1977- )

- Weep by George Moses Horton (1798–1883)

- The Wound-Dresser from Drum-Taps by Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

- What the End Is For by Jorie Graham (1950- )

- Biography of Walt Whitman, American Poet

- Walt Whitman and the Civil War

- Patriotic Poems for Independence Day

- A Classic Collection of Bird Poems

- Biography of Wilfred Owen, a Poet in Wartime

- Biography of Hilda Doolittle, Poet, Translator, and Memoirist

- Rupert Brooke: Poet-Soldier

- Feminist Poetry Movement of the 1960s

- 15 Classic Poems for the New Year

- Julia Ward Howe Biography

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- What Is Poetry, and How Is It Different?

- Poems of War and Remembrance

- 14 Classic Poems Everyone Should Know

- Poems of Protest and Revolution

Literary Matters

The Literary Magazine of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers

War Poetry, Political Poetry, and The Invisible Powers

- Text message

- Facebook Messenger

- Facebook Messenger (Mobile)

“The problem for a poet in writing about modern war is that, while he can only deal with events of which he has first hand knowledge—invention, however imaginative, is bound to be fake—his poems must somehow transcend mere journalistic reportage. In a work of art, the single event must be seen as an element in a universally significant pattern: the area of the pattern actually illuminated by the artist’s vision is always, more or less limited, but one is aware of its extending beyond what we see far into time and space.”

–W.H.Auden, preface to the first edition of Lincoln Kirstein’s Rhymes of a Pfc.

“The proper subjects for poetry are love, virtue, and war.”

–Dante Alighieri, De Eloquentia Vulgari , 1304

“Now you are in a new world, the world of invisible powers, the world of literature, of poem and story.”

–Mona Van Duyn, “Matters of Poetry”, (1993)

One day in Hanoi, where our Nôm Foundation was working at the National Library to digitize its several thousand ancient texts, I took a day off to visit the ancient Temple of Literature, founded in 1076 after the Vietnamese had finally driven out their Chinese overlords. Until 1919 when the Temple’s function ended under the French, this was the academy where Vietnam trained its governing elite in poetry, history, and philosophy, selecting gifted students from all social classes in the belief that a mind trained and tested in such subjects is a quick, sharp, and careful mind, and that such minds are important resources to the nation.

One enters the Temple grounds through a large stone gate topped with recoiling dragons indicating royal rule and its mandate from heaven. One then proceeds past gardens and ponds through another large gateway under a tile-roofed balcony where, over the centuries, new graduates declaimed their poetry. Perhaps the most striking thing one then sees are rows of 6-foot stone blocks standing on the backs of massive stone turtles. On these blocks are carved the names of those who graduated from the Temple and entered Vietnam’s civil service. Even today, hundreds of years after these graduates served the nation, one can see their descendants lighting incense sticks and placing them before those stone blocks in familial veneration.

Further on, in a room inside the Temple itself, there is a square stone carved in Chinese characters and next to it translations into modern Vietnamese and in English, which read as follows:

Virtuous and talented men are state sustaining elements. The strength and prosperity of a state depend on it[s] stable vitality and it becomes weaker as such vitality fails. That is why all the saint emperors and clear-sighted kings didn’t fail in seeing to the formation of men of talent and the employment of literati to develop this vitality.

–Examination Stele, Đai Bảo Dynasty, Third Year (1442).

Literati? Literary people as “state sustaining elements”? How on earth, we Americans might ask, can citizens trained in literary skills be “state-sustaining elements”? Why would the Vietnamese royal court set up a university for its best and brightest, regardless of class or wealth, and then train them largely in poetry, history, and philosophy?

If that seems a little far-fetched, consider this: Confucius, the Chinese philosopher to whom the Vietnamese Temple of Literature is dedicated along with the Duke of Chou (this after the Chinese were finally driven out) was once asked the perennial philosophic question of 4th century China—as it was the perennial question for Socrates in Plato’s The Republic —“what would you first do if allowed to rule a kingdom?” Confucius’ reply, as recorded in his Analects , was: “to correct language.” Because, he said, if language is not precise, “then what is meant cannot be effected. If what is meant cannot be effected, society falls apart.”

The useful application of the Confucian reply to our affairs today must be obvious. Here is the exchange from Book XIII of the Analects , written around 400 BC.

Tzu-lu said, “If the prince of Wei were waiting for you to come and administer his country for him, what would be your first measure?”

The Master said, “It would certainly be to correct language.”

Tzu-Lu said, “Did I hear you right? Surely what you say has nothing to do with the matter. Why should language be corrected?” 1

The Master said, “Lu! How simple you are! A gentleman, when things he does not understand are mentioned, should maintain an attitude of reserve. If language is incorrect, then what is said does not concord with what was meant; and if what is said does not concord with what was meant, what is to be done cannot be effected. If what is to be done cannot be effected, then society falls apart.”

Such precision in the use of words is of course a lifelong pleasure in-and-of itself, but it has immense practical value as well. Without such precision in the way we communicate with ourselves, with ourselves as a society, and with the world beyond, our private and public affairs falter and fall apart. Precision in the use of words is the talent which lends all other professions and skills their usefulness. It is a skill which goes beyond utilitarian technology. Such precision in speech, writing, and the reading of complex works of the human imagination brings to its practitioners and to their societies a more enriched sense of self and an inevitable moral expansion.

This skill, most notably found in poetry, is indeed “a state-sustaining endeavor.” It is no mere curiosity that from Vietnam’s earliest nationhood its rulers and foreign emissaries were always known poets. The 18th century ambassador to China, Nguyễn Du, decorated by his emperor as a “pillar of the nation,” is also Vietnam’s most famous poet. In modern times, Ho Chi Minh wrote quite good poetry in Vietnamese and in Chinese. The North Vietnamese Head of Delegation to the 1973 Paris Peace Talks was Xuân Thủy, known first as a poet.

Traditionally, the chief poetic vehicle for study and composition, was the “regulated” lü-shih verse form made classic by the Chinese master Tu Fu in the 8th century, and called th ơ đ ườ ng lu ậ t in Vietnamese. It is always eight lines, seven syllables to a line, rhyming usually on the first, second, fourth, sixth, and eighth lines, and requiring syntactic parallel structure in the middle four. For several East Asian societies it became the main lyric vehicle for centuries, serving them in the way the sonnet served the West. This form—whether written in Vietnamese or in Chinese—streamed with history and culture in generations of individuals possessing “bright mind.” As the stone tablet suggests, the strength and prosperity of a state depend on its stable vitality created by men and women who are trained to inquire, sharpen their minds, and expand their souls by an active engagement, we would say, with “the best words in the best order,” as Coleridge defined poetry in 1835 in his Table Talk .

This notion of poetry’s affecting voice resulting in moral action, is increasingly foreign to us. The idea that a poem can change political events probably seems to us quaint if not preposterous. Yet, even today, Vietnamese will gamble on a person’s ability to aptly end a poem, and political debates can be won by an appropriate poetic quotation. Indeed, legend has it that a Chinese invasion was once turned back by the poem below, supposedly painted on banana leaves and eaten by ants, the resulting poem causing panic in the invading troops. Whether this really happened isn’t as significant as the legend itself and its existence in popular belief:

南 國 山 河 南 帝 居 Our mountains and rivers belong to the Southern Ruler.

截 然 定 分 在 天 書 This is written in the Celestial Book.

如 何 逆 虜 來 侵 犯 Those who try to conquer this land

汝 等 行 看 取 敗 虚 Will surely suffer defeat.

–Marshall Lý Thường Kiệt (1019-1105)