- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A New Model for Ethical Leadership

- Max H. Bazerman

Rather than try to follow a set of simple rules (“Don’t lie.” “Don’t cheat.”), leaders and managers seeking to be more ethical should focus on creating the most value for society. This utilitarian view, Bazerman argues, blends philosophical thought with business school pragmatism and can inform a wide variety of managerial decisions in areas including hiring, negotiations, and even time management. Creating value requires that managers confront and overcome the cognitive barriers that prevent them from being as ethical as they would like to be. Just as we rely on System 1 (intuitive) and System 2 (deliberative) thinking, he says, we have parallel systems for ethical decision-making. He proposes strategies for engaging the deliberative one in order to make more-ethical choices. Managers who care about the value they create can influence others throughout the organization by means of the norms and decision-making environment they create.

Create more value for society.

Idea in Brief

The challenge.

Systematic cognitive barriers can blind us to our own unethical behaviors and decisions, hampering our ability to maximize the value we create in the world.

The Solution

We have both an intuitive system for ethical decision-making and a more deliberative one; relying on the former leads to less-ethical choices. We need to consciously engage the latter.

In Practice

To make more-ethical decisions, compare options rather than evaluate them singly; disregard how decisions would affect you personally; make trade-offs that create more value for all parties in negotiations; and allocate time wisely.

Autonomous vehicles will soon take over the road. This new technology will save lives by reducing driver error, yet accidents will still happen. The cars’ computers will have to make difficult decisions: When a crash is unavoidable, should the car save its single occupant or five pedestrians? Should the car prioritize saving older people or younger people? What about a pregnant woman—should she count as two people? Automobile manufacturers need to reckon with such difficult questions in advance and program their cars to respond accordingly.

- MB Max H. Bazerman is the Jesse Isidor Straus Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and the author (with Don A. Moore) of Decision Leadership: Empowering Others to Make Better Choices (Yale University Press, 2022) and Better, Not Perfect: A Realist’s Guide to Maximum Sustainable Goodness (Harper Business, 2020).

Partner Center

Leadership and Organisational Effectiveness Post-COVID-19 pp 147–167 Cite as

Leadership and Sustainability Development Goals: The Role of Ethics and Equity in Leadership in the Next Normal

- Okechukwu E. Amah 3 &

- Marvel Ogah 3

- First Online: 11 June 2023

192 Accesses

This book chapter continued the search for the future of leadership. However, the chapter emphasises how ethical leadership is understood, conceptualised, and evaluated. The review concluded that ethical leadership must be viewed from multiple dimensions, which must be jointly used to determine whether a leader is ethical. Ethical leaders must be ethical persons and managers by holding themselves and others responsible for an ethical violation. They must do this across situations and individuals. The chapter highlighted the challenges in using externally imposed ethical laws to make people ethical but instead advocated that ethics must be internally driven through personal values and virtues. This is the only way to sustain ethics and for ethical culture to outlive the leader.

- Ethical leadership

- Ethical person and manager

- Ethical culture

- Virtue ethics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Amah, O.E. 2022a. Linking the Covid-19 Work Experience of SMEs Employees to Post-Covid-19 Superior Productivity of SMEs. Journal of the International Council for Small Business 4 (2): 128–142.

Google Scholar

———. 2022b. The Relationship Between Political Will and Organizational, Political Behavior: The Moderating Roles of Political Prudence and Political Skill. Journal of Business Ethics 176: 341–355.

Article Google Scholar

Arjoon, S. 2000. Virtue Theory as a Dynamic Theory of Business. Journal of Business Ethics 28: 159–178.

Bazerman, M. 2020. A New Model for Ethical Leadership. Harvard Business Review 98 (5): 90–97.

Boddy, C.R.P., R. Ladyssherwsky, and P. Galvin. 2010. Leaders without Ethics in Global Business: Corporate Psychopaths. Journal of Public Affairs 10 (3): 121–138.

Brown, M.E., L.K. Treviño, and D.A. Harrison. 2005. Ethical Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective for Construct Development and Testing. Organizational Behavior Human Decision Process 97: 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002 .

Carlson, D.S., and P.L. Perrewe. 1995. Institutionalization of Organizational Ethics Through Transformational Leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 14: 829–838.

Chonko, L. n.d. Ethical Theories. DSEF . https://www.dsef.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/EthicalTheories.pdf .

CIPD 2017. Technical Report, 2017, Purposeful Leadership: What Is it, What Causes it, and Does it Matter?” www.cipd.co.uk/Images/purposeful-leadership_2017-technical-report_tcm18-24076.pdf .

Ciulla, J.B. 2004. Ethics and Leadership Effectiveness. In The Nature of Leadership , ed. J. Antonakis, A.T. Cianciolo, and R.J. Sternberg, 302–327. Sage Publications, Inc.

———. 2005. The State of Leadership Ethics and the Work That Lies Before Us. Business Ethics: A European Review 14 (4): 323–335.

———. 2018. Ethics and Effectiveness: The Nature of Good Leadership. In The Nature of Leadership , ed. J. Antonakis and D. David, 3rd ed., 438–469. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ciulla, J.B., and D.R. Forsyth. 2011. Leadership Ethics. In The SAGE Handbook of Leadership , ed. A. Bryman, D.L. Collinson, and K. Grint, 230. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Cullen, J.B., K.P. Parboteeah, and B.I. Victor. 2003. The Effects of Ethical Climates on Organizational Commitment: A Two-study Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 46 (2): 127–141.

Cumbo, L.J. 2009. Ethical Leadership: The Quest for Character, Civility, and Community. Current Reviews for Academic Libraries 47 (4): 726–726.

Darcy, K.T. 2010. Ethical Leadership: The Past, Present, and Future. International Journal of Disclosure & Governance 7 (3): 198–212.

Deloitte Report. 2021. How Business Leaders Can Build a More Equitable Workforce. Harvard Business Review . https://hbr.org/sponsored/2021/05/how-business-leaders-can-build-a-more-equitable-workforce .

Dunn, J. 2005. Leadership and Ethics: The Relationship of Leadership Style in Maintaining Organizational Ethical and Moral Behavior. Athabasca University MBA-ITM. http://dtpr.lib.athabascau.ca/action/download.php?filename=mba-06%2Fopen%2FDanielNorthamProject.pdf .

Edelman. 2022. Societal Leadership Is Now a Core Function of the Business. https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2022-01/2022%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20FINAL_Jan25.pdf .

Fowers, B.J., and A.C. Tjeltveit. 2003. Introduction: Virtue Obscured and Retrieved: Character, Community, and Practice in Behavioral Sciences. American Behavioral Scientist 47: 387–394.

Frank, D.G. 2002. Meeting the Ethical Challenges of Leadership. Journal of Academic Librarianship 28 (1/2): 81.

Gardner, J.W. 1990. On Leadership . New York: The Free Press.

Gentry, L., and J.W. Fleshman. 2020. Leadership and Ethics: Virtue Ethics as a Model for Leadership Development. Clinic in Colon Rectal Surgery 33 (4): 217–220. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-17094370 .

Greenleaf, R.K. 1977. Essentials of Servant Leadership. In Focus on Leadership: Servant-Leadership for the 21st Century , ed. L.C. Spears and M. Lawrence, 3rd ed., 19–25. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Harvard Business Review: Analytical Services. 2019. Creating a Culture of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: Real Progress Requires Sustained Commitment. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-andforecasting/researchandsurveys/Documents/DEI%20Metrics%20Full%20Report.pdf .

Holcombe, E., Adrianna, K., Dizon, J. P. M., Vigil, D., and N. Ueda. 2022. Organizing shared equity leadership: Four approaches to structuring the work . Washington, DC: American Council on Education; Los Angeles: University of Southern California, Pullias Center for Higher Education.

Hood, J.N. 2003. The Relationship of Leadership Style and CEO Values to Ethical Practices in Organizations. Journal of Business Ethics 43 (4): 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023085713600 .

Johnson, C. 2003. Enron’s Ethical Collapse: Lessons for Leadership Educators. Journal of Leadership Education 2 (1): 45–56.

Kaptein, M. 2011. Understanding Unethical Behavior by Unraveling Ethical Culture. Human Relations 64 (6): 843–869. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710390536 .

Kezar, A.J., and E.M. Holcombe. 2017. Shared Leadership in Higher Education: Important Lessons from Research and Practice . Washington, DC.

Kirkpatrick, S.A., and E.A. Locke. 1991. Leadership: Do Traits Matter? Academy of Management Executive 5 (2): 48–60.

Laker, B. 2021. Leaders Need to Establish More Equity: Here’s How. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/benjaminlaker/2021/01/26/leaders-need-to-establish-more-equity-heres-how/?sh=4d31aeb534ff .

Lencioni, P. 2020. The Motive: Why Do So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important Responsibilities . John Wiley & Sons.

Mackie, J.E., A.D. Taylor, D.L. Finegold, A.S. Daar, and P.A. Singer. 2006. Lessons on Ethical Decision Making from the Bioscience Industry. PLoS Medicine 3 (4): e129-0610.

Marshall, A., D. Baden, and M. Guidi. 2013. Can an Ethical Revival of Prudence within Prudential Regulation Tackle Corporate Psychopathy? Journal of Business Ethics 117: 559–568.

Martinez-Saenz, M.A. 2009. Ethical Communication: Moral Stances in Human Dialogue. Current Reviews for Academic Libraries 47 (4): 693–693.

Marzano, M. 2012. Éloge de la Confiance . Paris: Pluriel.

Mathooko, J.M. 2013. Leadership and Organizational Ethics: The Three-Dimensional African Perspectives. BMC Medical Ethics 14 (1): 1–14. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6939/14/S1/S2 .

Monahan, K. 2012. A Review of the Literature Concerning Ethical Leadership in Organizations. Emerging Leadership Journeys 5 (1): 56–66.

Munchus, G., III. 1983. Employer-Employee Based Quality Circles in Japan: Human Resource Policy Implications for American Firms. The Academy of Management Review 8 (2): 255–261.

Pastin, M. 1986. The Hard Problems of Management: Gaining the Ethics Edge . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pellegrino, E.D., and D.C. Thomasma. 1993. The Virtues in Medical Practice . New York: Oxford University Press.

Plinio, A.J. 2009. Ethics and Leadership. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 6 (4): 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1057/jdg.2009.20 .

Plinio, A.J., J.M. Young, and L.M. Lavery. 2010. The State of Ethics in Our Society: A Clear Call for Action. International Journal of Disclosure & Governance 7 (3): 172–197.

Randall, D.M., and A.M. Gibson. 1990. Methodology in Business Ethics: A Review and Critical Assessment. Journal of Business Ethics 9: 457–471.

Roque, A., J.M. Moreira, J.D. Figueiredo, R. Albuquerque, and H. Gonçalves. 2020. Ethics Beyond Leadership: Can Ethics Survive Bad Leadership? Journal of Global Responsibility 11 (3): 275–294.

Ross, W. D. 1930. The Right and the Good . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sandel, M.J. 2009. Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? New York: Farra, Straus and Giroux.

Schwartz, M.S. 2013. Developing and Sustaining an Ethical Corporate Culture: The Core Elements. Business Horizons 56 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2012.09.002 .

———. 2016. Ethical Decision-Making Theory: An Integrated Approach. Journal of Business Ethics 139: 755–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2886-8 .

Schwartz, M.S., and A. Carroll. 2003. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Three-Domain Approach. Business Ethics Quarterly 13 (4): 503–530.

Scordis, N.A. 2011. The Morality of Risk Modeling. Journal of Business Ethics 103 (1): 7–16.

Singer, M.S. 1996. The Role of Moral Intensity and Fairness Perception in Judgments of Ethicality: A Comparison of Managerial Professionals and the General Public. Journal of Business Ethics 15: 469–474.

Skovira, R., and K. Harman. 2006. An Ethical Ecology of a Corporate Leader: Modeling the Ethical Frame of Corporate Leadership. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge & Management 1: 159–170.

Tullberg, J. 2009. Moral Compliance and the Concealed Charm of Prudence. Journal of Business Ethics 89: 599–612.

Villirilli, G. 2021. The Importance of Being an Ethical Leader and How to Become One. BetterUp. https://www.betterup.com/blog/the-importance-of-an-ethical-leader .

Waggoner, J. 2010. Ethics and Leadership: How Personal Ethics Produce Effective Leaders. CMC Senior Theses. Paper 26. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/26 .

Winters, M. 2020. Equity and Inclusion: The Roots of Organizational Well-being. Stanford Social Innovation Review October 14. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/equity_and_inclusion_the_roots_of_organizational_well_being .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos Business School, Lekki, Nigeria

Okechukwu E. Amah & Marvel Ogah

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Amah, O.E., Ogah, M. (2023). Leadership and Sustainability Development Goals: The Role of Ethics and Equity in Leadership in the Next Normal. In: Leadership and Organisational Effectiveness Post-COVID-19. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32763-6_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32763-6_9

Published : 11 June 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-32762-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-32763-6

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2024

A collaborative endeavour to integrate leadership and person-centred ethics: a focus group study on experiences from developing and realising an educational programme to support the transition towards person-centred care

- Qarin Lood 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Eric Carlström 2 , 5 , 6 ,

- Charlotte Klinga 2 , 7 , 8 &

- Emmelie Barenfeld 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 395 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

53 Accesses

Metrics details

Ensuring the transition towards person-centred care is a growing focus in health and social care systems globally. Presented as an ethical framework for health and social care professionals, such a transition requires strong leadership and organisational changes. However, there is limited guidance available on how to assist health and social care leaders in promoting person-centred practices. In response to this, the Swedish Association of Health Professionals and the University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care collaborated to develop an educational programme on person-centred leadership targeting health and social care leaders to support the transition towards person-centred care in Sweden. The aim with this study was to explore programme management members’ experiences from the development and realisation of the programme.

Focus group discussions were conducted, involving 12 members of the programme management team. Data from the discussions were analysed using a structured approach with emphasis the collaborative generation of knowledge through participant interaction.

The analysis visualises the preparations and actions involved in programme development and realisation as a collaborative endeavour, aimed at integrating leadership and person-centred ethics in a joint learning process. Participants described the programme as an ongoing exploration, extending beyond its formal duration. Leadership was thoughtfully interwoven with person-centred ethics throughout the programme, encompassing both the pedagogical approach and programme curriculum, to provide leaders with tangible tools for their daily use.

Conclusions

According to our analysis, we conclude that a person-centred approach to both development and realisation of educational initiatives to support person-centred leadership is essential for programme enhancement and daily implementation of person-centred leadership. Our main message is that educational initiatives on the application of person-centred ethics is an ongoing and collaborative process, characterised by an exchange of ideas and collective efforts.

Peer Review reports

There is a growing emphasis on endeavours to establish health and social care systems, procedures, and practices that prioritise the importance of persons [ 1 ]. This indicates a need to delve into how to promote the principles of person-centred care (PCC). Conceptualised as an ethical framework that directs healthcare professionals in their daily responsibilities, PCC serves as a core care philosophy necessitating strong leadership and substantial structural and organisational adjustments [ 2 ]. As such, the implementation of PCC has been described as complex and challenging [ 3 , 4 ], requiring collective efforts and partnerships between health and social care stakeholders [ 5 ]. Health and social care leaders have been described as key stakeholders in the implementation of PCC [ 6 , 7 , 8 ], but there is little guidance on how to educate leaders to take on the role of leading towards PCC.

According to Swedish law [ 9 ], the design and execution of health and social care interventions should be person-centred in terms of being determined in partnership with the person in need of care as far as possible. Nevertheless, there are challenges in determining how person-centred ethics can be seamlessly incorporated into routine care practices [ 10 ]. Even in countries known to practice PCC, like the United Kingdom and Sweden, there seem to be barriers for the implementation of PCC. For instance, Moore et al. [ 10 ] describe adverse consequences of organisational norms and role expectations, recommending the need for robust leadership and adaptive strategies to support the implementation process. It is therefore argued that a person-centred approach should permeate leaders’ and, managers’ actions and their way of being when leading towards PCC to achieve the change in organisational culture required for implementation of PCC [ 7 , 11 , 12 ]. Hereafter, this leadership approach is referred to as person-centred leadership, described previously as an intricate, relational, and dynamic context-based approach to leadership, aspiring to empower both co-workers and leaders [ 13 ]. Person-centred leadership is portrayed as translating the ethics of PCC into everyday leadership practice, promoting a person-centred atmosphere by establishing trust and responsibility, encouraging innovation, and potentiating cultural bearers among co-workers [ 12 ]. Moreover, person-centred leadership includes making use of relational competencies to facilitate a workplace culture based on partnerships in decision-making and collaboration between leaders, co-workers, and persons in need of care [ 8 ]. Establishing prerequisites to enable PCC is also raised as an essential element of person-centred leadership [ 12 , 14 ]. Still, health and social care leaders have limited resources when it comes to leading in a person-centred way, and past research has recommended the development of educational curricula that emphasise person-centred leadership [ 6 , 7 , 10 ]. Previous educational programmes on PCC have mainly targeted health and social care professionals [ 4 ], and little is known on how educational curricula should be developed to promote a person-centred culture throughout health and social care organisations.

The University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-centred Care (GPCC) has developed three routines to facilitate the translation of person-centred ethics to healthcare practice: (1) Initiating a partnership—patient narrative, (2) working in partnership—shared decision-making, (3) safeguarding the partnership—documenting the narrative [ 15 ]. These routines have been evaluated in healthcare research, indicating effectiveness on individual as well as organisational levels [ 7 ]. What is not yet known is how these routines can be applied on leadership to facilitate the transition towards PCC in different health and social care contexts. In 2015, the Swedish Association of Health Professionals (SAHP, a trade union for registered nurses, midwives, radiographers, and biomedical scientists) and GPCC therefore decided to initiate the development of an educational programme on person-centred leadership, targeting health and social care leaders who are members of the SAHP. The programme has later been revised to adhere to societal changes and the needs and preferences of health and social care leaders. As one part of the scientific exploration of this programme (assessments of effects and significance will be reported in separate studies), the aim with the study was thus to explore programme management members’ experiences from the development and realisation of an educational programme on person-centred leadership. More specifically, we sought answers to the following research question: what preparations and actions were involved in developing and realising an educational programme to support leadership directed towards PCC?

With the aim to explore programme management members’ experiences, this study had a social constructivist design, applying focus group methodology [ 16 , 17 ]. This means that the study was built on a view that knowledge is co-created in interaction between participants who share their views and experiences in focus group discussions. More specifically, this meant that the participants in the study were encouraged to stimulate each other in discussions, to explore their shared experiences from developing and realising the educational programme. This approach to focus group research is suitable to uncover knowledge that is concealed but understood by participants [ 18 ] (e.g., tacit knowledge on pedagogical approach and leadership skills in programme development and realisation). Moreover, as described in the literature [ 16 , 17 ], shared experiences are a powerful tool for expressing both positive and negative aspects of what is being studied, which is why focus groups were considered an appropriate method for the study, rather than individual interviews. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the study (dnr. 2022-04052-01) and the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [ 19 ] were utilised when writing this report.

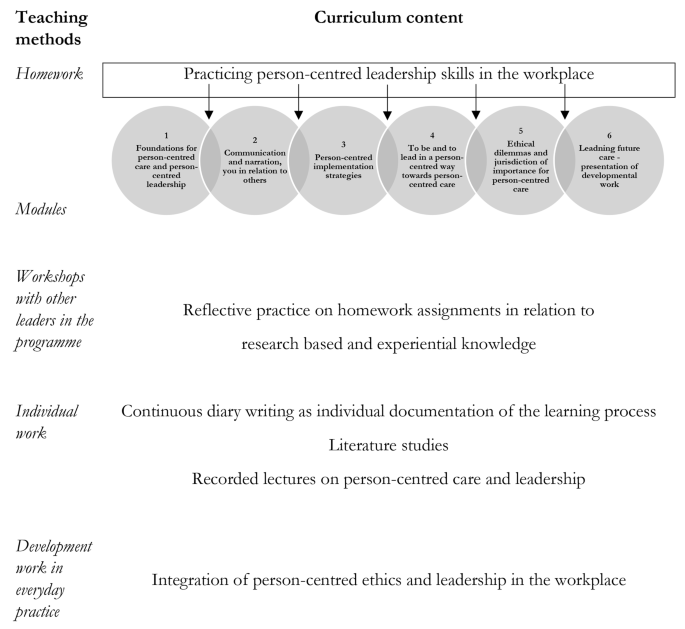

The curriculum for the educational programme under exploration has been developed and revised in collaboration between researchers from GPCC and educators from SAHP, forming the programme management, to support the realisation of person-centred ethics in leadership across different health and social care organisations in Sweden. Admitting 40 health and social care leaders per year, the programme was initially provided between 2015 and 2019. After being put on hold between 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the programme was revised to a more digital format in 2022, admitting 80 leaders per year. To be admitted to the programme, leaders had to be responsible for units or care activities targeting people in need of health or social care. Most leaders in the programme have been middle managers, but there have also been leaders with other leading positions within the Swedish health and social care system.

Incorporating blended learning, the programme illuminates person-centred ethics and leadership from various perspectives over a six-month period to support leaders in achieving the following learning outcomes:

Knowledge and understanding

Summarise key foundational principles relevant to person-centred care and person-centred leadership.

Explain what characterises a person-centred leadership and employee perspective within the own organisation, supported by course literature and proven experience.

Competence and skills

Discover and define opportunities and areas of development regarding how person-centred ethics is expressed in current practice.

Create a proposal for an action plan for a change process towards person-centred care or person-centred leadership.

Apply person-centred principles during the implementation of a change process.

Judgement and approach

Critically discuss how organisation, culture/structure within different contexts influence the conditions for person-centred care.

From a leadership perspective, assess the implementation, results of the change process, as well as the need for further actions.

Discuss central assumptions within person-centred ethics in relation to sustainable development.

The programme corresponds to 7.5 higher education credits, divided into five digital modules (module 1, 3–6) and one physical module (module 2). Each module focuses on different aspects of person-centred leadership and person-centred ethics as follows: (1) Foundations for PCC and person-centred leadership, (2) communication and narration, you in relation to others, (3) person-centred implementation strategies, (4) to be and to lead in a person-centred way towards PCC, (5) ethical dilemmas and jurisdiction of importance for PCC, (6) leading future care—presentation of developmental work. Practical home-assignments to practice work in partnership were performed between the learning modules in both the original and revised programme. For an overview of the educational curriculum, please see Fig. 1 .

Overview of the educational curriculum

Participants

The participants were researchers with experience from studying PCC ( n = 4) or leadership ( n = 1) and educators from the SAHP ( n = 7), all with experience of either developing and/or realising the programme. They were 11 females and one male, and they had been involved in different stages of the programme development and realisation between year 2015–2022. A total of four focus groups with three to four participants per group were conducted digitally with the participants taking part from their homes or offices during working hours. In line with the focus group methodology [ 16 , 17 ], both homogeneity and heterogeneity were considered when selecting participants and putting together the groups. Homogeneity concerns having similar experiences and is important to generate discussion. In this study, homogeneity within each group was ensured by inviting persons with shared experiences of programme development phase and assignment. Heterogeneity concerns diversity within the target group and in this study, diversity was ensured by mixing participants with different work experience and roles in the development and realisation of the programme. Due to their roles in the development and realisation of the programme, two of the participants have been involved as co-authors (CK and EB), providing an insider perspective of the programme teaching methods and curriculum content that could not have been captured without their involvement. To ensure credibility of the findings they have not been involved in the primary analysis. Four persons in the programme management participated in two focus group discussions, with the aim to capture experiences from both the original development and realisation of the programme, and from the revision of the programme to a digital format. See Table 1 for details on participant roles. The names of participants referred to in this context are fictious to safeguard personal integrity and adhere to Swedish data protection regulations.

Potential participants were invited via email, with a participant information statement and consent form attached. The statement comprised information on the aim of the study and what participation would require of participants should they choose to participate. All persons except one (who did not reply) consented to participate and were scheduled in for a digital focus group discussion using their preferred software (Microsoft Teams or Zoom). All focus groups were moderated by the second author and observed by a research amanuensis (group 1) or the first author (group 2–4) who took notes on the interaction between participants as well as each person’s engagement in the discussions.

Each focus group started with a confirmation of consent and a reminder to send the informed consent form to the researchers, followed by a short presentation of the participants and the researchers, including the participants’ current work role and their role in the development of the programme. Then, the moderator (second author) initiated the discussion by posing key questions developed by the research team involved in this study (see Supplementary file 1 ), starting with a question on why a leadership programme with focus on person-centred care was developed. Follow-up questions were posed to deepen the understanding of the participants’ experiences from the development and realisation of the programme. An important role for the moderator and the observer was to ensure that all participants were given an opportunity to speak, and to identify common elements in the discussions. The focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription firm. Video was only used to stimulate interaction between participants and was not used in the analysis. Interaction was further facilitated by the moderator who encouraged participants to discuss their experiences with each other. The focus groups lasted between 57 and 100 min and were performed during 2022 and 2023.

Data analysis

Krueger and Casey’s [ 20 ] systematic method for data analysis was used to analyse the audio recordings and transcriptions iteratively. This meant that the first author started the analysis procedure by listening to all focus group recordings and reading the transcripts and field notes carefully, making notes on content in relation to the study aim, to identify preliminary themes that were discussed with the other authors. Then, the first author started coding the transcribed data by sorting it according to the study aim and coding each response. To describe the content of the focus groups, the first author then prepared a summary statement that was discussed with all authors. The next step involved a formulation of themes. The summary statement was compared with the transcribed data and the field notes to identify internal consistency and the participants’ expressed experiences of importance of each question in terms of frequency, extensiveness, intensity, and specificity. This step resulted in revised themes and sub-themes that were discussed with all authors to reach a final interpretation of the meaning of the focus group discussions. The analysis was conducted in Swedish until the final formulation of themes and sub-themes was reached. The results were then translated to English.

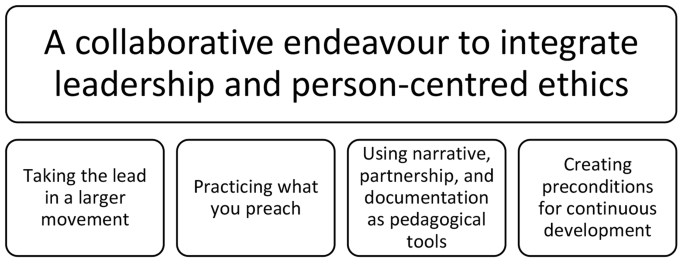

The participants’ experiences from the development and realisation of the educational programme are described in the overarching theme “A collaborative endeavour to integrate leadership and person-centred ethics”, visualising a person-centred approach as essential in both preparations and actions involved in the development and realisation of the programme. These experiences are further described in four themes: (1) Taking the lead in a larger movement, (2) Practicing what you preach, (3) Using narrative, partnership, and documentation as pedagogical tools , and (4) Creating preconditions for continuous development , as visualised in Fig. 2 and described in detail below.

Overview of the thematical structure

A collaborative endeavour to integrate leadership and person-centred ethics

The overarching theme visualises the development and realisation of the educational programme as a dynamic and continuous process marked by collective efforts and an atmosphere of free exchange of ideas to allow for refinements of programme structure and content. Drawing from their experiences from academia, healthcare practice and leadership, the participants described how they developed the programme in partnership, to integrate knowledge on leadership and person-centred ethics. Used as both goals and means, person-centred ethics were thus experienced to have permeated the whole programme from development to realisation, with focus on joint learning among programme management as well as participating leaders. Dialogues between programme management and participating leaders were described as a pivotal element, allowing for joint discussions and reflections as a contrast to one-way communication through lectures. This was further described to foster partnerships between programme management and the participating leaders, which meant that the unique competencies and experiences of each person were harnessed to generate synergy effects during programme development, realisation and beyond.

Taking the lead in a larger movement

With the goal to contribute to a deeper understanding of both what person-centred ethics entail, and how they can be integrated into leadership to change everyday care practice, the development of the programme was experienced to lead the way in the larger movement towards PCC in Sweden. The participants strove to be at the forefront of the larger movement, for example by admitting more leaders from different parts of the country in the revised, more digital version of the programme. Although there were some technical issues with the digital format, the benefits of reaching out geographically were experienced as facilitators for making it a joint course to lead Swedish health and social care organisations towards becoming more person-centred. Continuous reflection and openness to different persons’ perspectives during programme development and realisation were experienced as a support for both the participants’ own, as well as the leaders’, learning on how to facilitate the transition towards PCC. The participants also described how they came to realise that theoretical knowledge was not enough, practical knowledge on how to lead in a person-centred way was also needed. Practical exercises on who the leaders are and how they view themselves in relation to others were therefore created to deepen the participating leaders’ understanding of the significance of mutual respect and clarity around roles. These exercises were developed to assist leaders in pioneering person-centred practices for a broad spectrum of health and social care professionals, as envisioned in the quote from focus group one:

Moderator: Well, the first question must be: Why a leadership education in person-centredness? Maria:…the initial standpoint is that the Swedish Association of Health Professionals wants to take a leading role in the development of person-centred care… We want to contribute to the development of managers and leaders in healthcare, enabling them to work with person-centred approaches and also with more person-centred leadership… By investing in managers, a tremendous number of people will have the opportunity to benefit from this and will also be involved in the development and transformation towards more person-centred care. Emma:…I think that we have seen that managers need support in this. There is a great interest in person-centred care, but how should it be implemented? How can one feel confident in person-centred care? What steps should be taken to make it a reality in the organisations? So, I believe it was a natural step to start with our managers and leaders. Selma: What I find so exciting when looking at this question from sort of another perspective is that, from a research standpoint, we know that leadership is crucial for achieving implementation and sustainability in person-centred care. So, it feels, yes, so exciting and important that you have had and continue to have this education.

Practicing what you preach

During programme realisation, the participants described how they became aware of the need to practice what they preached in terms of having a person-centred approach towards leaders participating in the programme. Both knowing what PCC is, and being able to practice it through the programme’s pedagogical approach were described as important to facilitate each person’s learning process, illustrated by a quotation from focus group four:

Lena: The actual pedagogy in the education was also about viewing them as persons. As you said Rakel,” What resources do you have?”. To also be very genuine in the person-ce(ntred) approach, it was not just knowledge that needed to be conveyed, it was also an… truly an attitude that needed to be embraced by those leading the programme. Frida: Exactly. And I think that’s very… the pedagogical aspect of embodying— of also conveying…not necessarily living as one preaches, but also, what is a person-centred approach when you apply it to your own… where you stand? I believe… that was probably the challenging aspect to convey later in this bridge because it wasn’t explicitly stated that this would also be the task for those who became the carriers of culture from GPCC afterward.

Practicing what you preach was further described in relation to the experienced need for transparency from programme management regarding programme organisation and pedagogical approach, i.e., putting words on what was done and how and why they were done, to clarify the thoughts and reasons behind it. Still, there were challenges described with the pedagogical approach, in striving to see each leader as a person and support their learning by listening to their narratives and acknowledging their individual resources and needs. As such, flexibility was a virtue emphasised as essential during programme realisation, allowing for different pedagogical methods, for plans to shift, goals to evolve, and perspectives to change.

Using narrative, partnership, and documentation as pedagogical tools

This theme describes how the core concepts of GPCC’s model for PCC [ 15 ], i.e., narrative, partnership , and documentation , became key pedagogical tools to bridge experienced challenges with conveying how person-centred ethics could be applied in day-to-day leadership. The participants described how using narratives seemed to have sparked the leaders’ awareness of how they lead, which role they have within their organisation, and who they are in relation to other people. Partnership was experienced as a tool for leaders to understand how their relationships with co-workers had evolved by listening to, and acknowledging, them as persons. Practical exercises and examples were experienced to support the leaders in how narratives can be used to build partnerships with co-workers and come to shared decisions that are jointly documented. Documentation was also experienced as a pedagogical tool for joint reflection and learning among the participating leaders, through presenting and discussing their documented plans for how to integrate person-centred ethics with their leadership within their organisations. We have chosen a quotation from focus group two to visualise how GPCC’s model was used as a pedagogical tool during the programme.

Selma: We have discussed partnerships based on the model you (the moderator) just described. We have provided practical examples throughout the entire education on how to work in partnership and how to use narratives and dialogue. How we arrive at shared decision-making, documentation. This is something we have integrated into the entire education that is present during each session. And to emphasise that it should be a mutuality in this partnership, where we see each other as persons with unique resources and abilities. But where we, at the same time, know that humans have a vulnerability, and that’s what allows us to open up to each other in a partnership. Maria: That’s one part, I think. But it’s also… just as you said (moderator’s name), it is… being a manager also means having certain expectations placed on oneself that you should… So it’s… What should I say? This respect we have, the mutual respect we have for each other, understanding each other’s roles as well, I believe, is an important part of this person-centred leadership and partnership, making it clear to everyone what roles we have. And then it’s this with the competence and the person one is, with one’s entire life history in some way, that can be valuable to the organisation one is part of. And so I agree with what you are saying, Selma. But we also incorporate… Because Lisa has also talked about the fact that one needs… One needs a role where one needs to take on a different responsibility than what the employees may need as a manager.

Creating preconditions for continuous development

Supporting the collaborative endeavour towards PCC, the participants experienced a need for creating preconditions for continuous development of person-centred leadership after the programme has ended. One way of doing this was to cultivate a sense of shared purpose to leave an indelible mark on the leaders when it comes to person-centred ethics and becoming person-centred in their leadership. Even so, there was an experienced risk of leaders going back to working as before, without sustainable changes. To support leaders to go from knowledge to action, practical homework exercises were developed to provide the leaders with tools on a day-to-day basis, as described in previous themes. Fulfilling the expectation of participating leaders to take a leading role in the movement towards PCC, national networking also became part of the programme, to contribute to a sense of community and opportunities for continuous reflection and development. National networks of leaders and managers who have completed the programme were developed to provide an arena for sharing positive examples and mutual learning on how leadership and person-centred ethics can be integrated. Nevertheless, as many health and social care leaders have other professions than SAHP’s members, the participants expressed a need for continuous development of the programme to include all healthcare professions in the programme, to allow for a sharing of knowledge across professional boundaries. The importance of networks is described in the quotation from focus group three below.

Tanja: The third (purpose of the programme) was to form networks within it. I mean, to create networks within this group and for ongoing work. So, you, you got, well, let’s put it this way, a national network of colleagues… whom I know continue to exchange thoughts and ideas with each other. I’ve met several of these participants now in… over the years and in my new assignments. And since there are 200 people, I can’t remember exactly which course. But they remember precisely. And they talk about how they have continued. And also that it has inspired them to take leadership positions in the transition towards integrated care. Eva-Britt: Yes, I know that… think that last part is really important to emphasise as well, that you form networks and that it’s not just… just as you said, that it is the components, Tanja. You gain knowledge and abilities to find your motivations and so on. And it’s also part of that… that “I set the ball in motion both at home and the contacts I have across the country and so on.” It’s truly an active education that aims to bring about change in healthcare towards person-centredness.

This study aimed to explore programme management members’ experiences from the development and realisation of an educational programme on person-centred leadership. Our main finding is the illustration of how person-centred ethics permeated the whole programme, from development to realisation. The participants highlighted the importance of dialogues and continuous reflection during programme development, to allow for innovative collaboration, mutual support, and a commitment to support leaders to go from knowledge to action. Overcoming challenges with communicating person-centred ethics, the participants further provided examples of how to apply GPCC’s routines for PCC (narratives, partnership and documentation) [ 15 ] as pedagogical tools to support a person-centred leadership. This knowledge can be used to develop educational curricula to support health and social care leaders in leading towards PCC.

To the best of our knowledge, there is a limited presence of educational curricula that genuinely embrace a person-centred pedagogical approach or are designed to educate health and social care leaders with a person-centred focus [ 21 ]. Previous research has highlighted that educational curricula should be characterised by innovation, not only in their preparation of practitioners but also in their proactive development of healthcare practice environments and cultures that promote PCC [ 22 ]. Björkman et al. [ 23 ] further describe the implementation of PCC in Swedish higher education of healthcare professionals as an ongoing and fragmented process, primarily led by persons with particular interests. Highlighting uncertainty and ambiguity concerning the significance and worth of PCC, as well as the methods for effective implementation, they suggest further research on the fundamental essence of PCC as an educational subject, alongside the development of suitable didactic strategies aimed at guiding students to become proficient in person-centred practice [ 23 ]. Our findings answer to this call for research and are especially relevant in the light of the paucity of research concerning the practical implementation of values within health and social care organisations, particularly in the realm of person-centred leadership [ 8 ]. A novel discovery from our study involves outlining factors to consider when creating person-centred curricula for leaders in health and social care. We recommend adopting a person-centred pedagogical approach, which utilises narratives, partnership, and documentation as tools for leaders to employ a person-centred approach in their leadership roles. Visualising person-centred ethics both as goals and means, the participants described the employment of a person-centred approach as an iterative learning process, facilitated by partnerships between programme management, participating leaders, and co-workers within the leaders’ organisations. This finding is supported by a recent international education initiative [ 24 ], illustrating the need for person-centred curricula to be both philosophically and methodologically aligned with person-centred principles. In agreement with this initiative, our findings suggest that person-centred curricula are needed to capture the intricacies of implementing PCC in contemporary healthcare organisations.

The interconnectedness between PCC and person-centred leadership has been described in previous literature [ 8 ], and implementation of PCC can be seen as a strategic healthcare system change. Such system changes can be very difficult [ 25 ] with contextual aspects shaping the change process in complex ways [ 26 , 27 ]. For instance, change may be affected by the complex integration of local cultures, professional attitudes, communication patterns and leadership styles [ 28 ]. The studied programme was specifically developed to take the lead in the ongoing transition towards PCC in Sweden. Practical homework assignments were combined with theoretical lectures, literature studies and reflective practice to support the leaders’ learning process and provide them with everyday tools for person-centred leadership. The homework assignments were developed to allow leaders to experience person-centredness in their leadership roles. Put in relation to the existing literature on learning [ 29 ], this could be understood as second-degree learning, denoting a profound form of learning where collective values undergo transformation to the extent that they impact the person’s actual work. As described by Binns [ 30 ], leadership at the level of everyday practice is fundamentally relational and somewhat removed from management and hierarchical position [ 30 ]. Viewed from this perspective, second-degree learning is a crucial requirement for successful integration of person-centred ethics and leadership. Allowing leaders to experience person-centredness in actual encounters with co-workers, the homework exercises in the studied programme provided a sense of authenticity. However, planning suitable and effective homework exercises poses a significant challenge for educators, especially when the goal is to enhance preparedness for collectively addressing the complexity of implementing PCC. Consequently, the development of person-centred curricula for health and social care leaders has a key-role in bridging challenges to implementation and supporting the realisation of PCC in everyday practice.

The power of healthcare systems has been demonstrated in shaping the implementation of new working methods [ 25 ], such as PCC. For example, health and social care professionals might exhibit resistance to reforms that are seen as altering established work routines. This mirrors the influence of professionals and the strategies employed by them. As reflected in our findings, educational programmes on person-centred ethics could provide guidance for leaders to enact essential changes among co-workers within their organisations. McCormack et al. [ 31 ] further describe the need for ongoing support of a learning culture within healthcare systems to facilitate PCC [ 31 ]. The continuous development described in our findings could be seen as such a support, incorporating learning environments for healthcare leaders to cultivate collaborative practices. Person-centred leadership can be regarded a collaborative practice, rooted in caring for co-workers. The modules in the educational programme under exploration were developed to support leaders in their learning process, to recognise and acknowledge the resources of both them and co-workers. In combination with the fostering of national networks of peers, the educational programme was described as a safe environment for reflection on person-centred ethics in the hierarchical environments which healthcare leaders often find themselves in. This was believed to enable leaders to act in a person-centred way and maintain authenticity in their leadership roles, but the nature of this study does not allow for such conclusions. We therefore suggest and plan for further evaluations of the programme’s impact on participating leaders.

Finally, regarding the practical implications of our findings, we suggest continuous development and refinements of educational curricula to fully embrace person-centred ethics as both the goals and means. Notably, dialogues played a crucial role in promoting such development. Inclusive discussions and joint reflection are needed for both programme development and realisation, to support second-degree learning on how to integrate person-centred ethics and leadership on a day-to-day basis. The person-centred approach to both pedagogics and leadership in the educational programme fostered a strong partnership between programme management and leaders and was described as a foundation for partnerships between leaders and co-workers. In management research, there are indications that organisations are characterised by workplace partnerships that may impact practice. For instance, Ferris et al. [ 32 ] delineate leaders as persons with proficiency in effectively comprehending co-workers and leveraging this understanding to motivate them to align with organisational goals. This is corroborated by our findings, which illustrate the need for educational curricula to recognise the practicalities of how change is put to action, namely, through collaborative efforts in everyday practice.

Methodological considerations

Social constructivist focus groups are particularly useful for generating rich, context-specific data. They allow participants to interact with one another, building upon each other’s responses and providing nuanced insights that might be missed in individual interviews or surveys [ 17 ]. This epistemological foundation for the study was thoroughly considered in relation to the involvement of two of the participants as co-authors of this manuscript (CK and EB). The risk of biased interpretations of the findings was carefully reflected upon in relation to the benefits of utilising their insider perspective from being part of the programme development and realisation for both describing the programme and for translating the findings to practical implications. Furthermore, as Krueger and Casey’s [ 20 ] method is built upon understanding collective understanding, rather than focusing on individual participants’ voices, the risk of biased interpretation was minimised.

To avoid the development of excessive uniformity within the groups, we took great care in composing the groups, aiming to strike a balance between heterogeneity and homogeneity [ 20 ]. What bound the participants in our study together (homogeneity) was their mutual involvement in the programme development. Considering group dynamics, we also attuned to power imbalances and divided participants according to their roles in programme development. Past research has demonstrated that when people with shared experiences come together, they can engage in discussions with a sense of companionship, knowing that others can relate to their experiences, thus promoting a spirit of sharing [ 16 ]. There is, however, always a risk in focus group studies, that one or a few participants dominate the discussion, while others remain silent. This may skew the results and prevent a full exploration of diverse viewpoints. During the focus groups we therefore attuned to dominant voices and encouraged everyone to interact to positively impact the authenticity of the responses.

Since our focus groups were conducted digitally to enable participants from all over Sweden to participate, we were careful to compose the focus groups with people who already knew each other to establish rapport and trust among participants. In contrast to limitations highlighted in the literature [ 33 ] we encountered no technical problems during conduct, and the digital context was not experienced as a disruption in the participants’ sharing of experiences. Nevertheless, digital platforms may limit the ability to observe non-verbal cues such as body language, which can provide valuable context and depth to responses in traditional face-to-face focus groups [ 34 ]. What we observed in our study was a limited fluidity of conversation, possibly due to the digital context. The moderator strove to create a comfortable and non-judgemental atmosphere to encourage interaction, but due to the digital platform, participants were not able to engage in spontaneous exchanges and took turns rather than sharing their experiences freely.

It is important to note that each focus group in our study had a limited number of participants.

However, methodological literature [ 17 , 20 ] indicates that small groups of three to six participants are typically very dynamic, and that the quality of discussions are more influenced by participant engagement that the sheer number of participants. Despite issues with spontaneous exchanges described above, the participants in our study seemed to value the opportunity to participate in focus groups, leading to rich discussions where they openly shared their perspectives. It is also important to remember that findings from focus groups are context-specific, and even if we involved all eligible persons but one, the participants may not represent the diversity of perspectives within a larger population. With the aim to understand the participants’ shared experiences and provide insight into their articulation of knowledge [ 17 ], our findings thus provide insight into the perspectives of the specific participants involved.

In the context of implementing PCC through leadership, our findings advocate for an integration of person-centred ethics and leadership through a person-centred approach throughout programme development and realisation. The person-centred approach nurtured strong partnerships between programme management and leaders, forming the basis for leaders to build partnerships with co-workers within their organisations. Our findings further support continuous development and refinement of educational curricula, with meaningful dialogues being described as essential for both programme enhancement and the daily realisation of person-centred leadership. By recognising and harnessing the distinct competencies and experiences of each person involved, the development and realisation of the programme were experienced to yield synergistic outcomes, both during and after its completion. In essence, the person-centred approach aimed to create a dynamic and supportive environment for both programme management and participating leaders, to successfully integrate person-centred ethics with leadership in an educational curriculum for person-centred leadership.

Data availability

The data generated and analysed during this study are not publicly available due to the information provided to the involved persons when obtaining their informed consent, stating that all attempts would be made to maintain their confidentiality. De-identified data are available are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request to enable review and will be stored for 10 years from publication at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. All data are covered by the Swedish Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act and a confidentiality assessment will be performed at each individual request.

Abbreviations

- Person-centred care

University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care

The Swedish Association of Health Professionals

Phelan A, McCormack B, Dewing J, Brown D, Cardiff S, Cook N, et al. Review of developments in person-centred healthcare. Int Pract Dev J. 2020;10:1–29.

Article Google Scholar

Naldemirci Ö, Wolf A, Elam M, Lydahl D, Moore L, Britten N. Deliberate and emergent strategies for implementing person-centred care: a qualitative interview study with researchers, professionals and patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:527.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gyllensten H, Björkman I, Jakobsson Ung E, Ekman I, Jakobsson S. A national research centre for the evaluation and implementation of person-centred care: content from the first interventional studies. Health Expect. 2020;23(5):1362–75.

Dellenborg L, Wikström E, Andersson Erichsen A. Factors that may promote the learning of person-centred care: an ethnographic study of an implementation programme for healthcare professionals in a medical emergency ward in Sweden. Adv Health Sci Education: Theory Pract. 2019;24(2):353–81.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fridberg H, Wallin L, Tistad M. Tracking, naming, specifying, and comparing implementation strategies for person-centred care in a real-world setting: a case study with seven embedded units. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:1409.

Backman A, Lövheim H, Lindkvist M, Sjögren K, Edvardsson D. The significance of nursing home managers’ leadership - longitudinal changes, characteristics and qualifications for perceived leadership, person-centredness and climate. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31(9–10):1377–88.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Britten N, Ekman I, Naldemirci Ö, Javinger M, Hedman H, Wolf A. Learning from Gothenburg model of person centred healthcare. BMJ. 2020;370.

Eide T, Cardiff S. Leadership research: a person-centred agenda. In: McCormack B, van Dulmen S, Eide H, Skovdahl K, Eide T, editors. Person-centred Health care research. Hoboken; NJ.: Wiley; 2017.

Google Scholar

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (Socialdepartementet). Patient law (2014:821). (Patientlag 2014:821. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/patientlag-2014821_sfs-2014-821/ #K5 Accessed 16 Feb 2024.

Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, Naldemirci Ö, Elam M, Wolf A. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31(4):662–73.

Ekman I. Practising the ethics of person-centred care balancing ethical conviction and moral obligations. Nurs Philos. 2022;23:e12382.

Backman A, Ahnlund P, Sjögren K, Lövheim H, McGilton K, Edvardsson D. Embodying person-centred being and doing: leading towards person-centred care in nursing homes as narrated by managers. J Clin Nurs. 2019;29(1–2):172–83.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cardiff S, Phil D, McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred leadership: a relational approach to leadership derived through action research. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(15–16):3056–69.

Rosengren K, Buttigieg S, Badanta B, Carlstrom E. Diffusion of person-centred care within 27 European countries—interviews with managers, officials, and researchers at the micro, meso, and macro levels. J Health Organ Manag. 2022;37(1):17–34.

Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink E, et al. Person-centered care–ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–51.

Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Hultberg J. Understanding the multiple realities of everyday life: basic assumptions in focus-group methodology. Scand J Occup Ther. 2006;13(2):125–32.

Kitzinger J. The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol Health Illn. 1994;16:103–21.

Ryan KE, Gandha T, Culbertson J, Carlson C. Focus group evidence: implications for design and analysis. Am J Evaluation. 2014;35(3):328–45.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Krueger R, Casey M. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.; 2015.

Fields L, Trostian B, Moroney T, Dean B. Active learning pedagogy transformation: a whole-of-school approach to person-centred teaching and nursing graduates. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;53:103051.

Dickson C, van Lieshout F, Kmetec S, McCormack B, Skovdahl K, Phelan A, et al. Developing philosophical and pedagogical principles for a pan-european person-centred curriculum framework. Int Pract Dev J. 2020;10:1–20.

Björkman I, Feldthusen C, Forsgren E, Jonnergård A, Lindström Kjellberg I, Wallengren Gustafsson C, et al. Person-centred care on the move - an interview study with programme directors in Swedish higher education. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:589.

O’Donnell D, Dickson C, Phelan A, Brown D, Byrne G, Cardiff S, et al. A mixed methods approach to the development of a person-centred curriculum framework: surfacing person-centred principles and practices. Int Pract Dev J. 2022;12:1–14.

Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis SJ, Saul J, Carroll S, Bitz J. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q. 2012;90(3):421–56.

Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

Turner S, Ramsay A, Perry C, Boaden R, McKevitt C, Morris S, et al. Lessons for major system change: centralization of stroke services in two metropolitan areas of England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;21(3):156–65.

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long J, Ellis L, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):63.

Stein J. How institutions learn:a socio-cognitive perspective. J Econ Issues. 1997;31(3):729–40.

Binns J. The ethics of relational leading: gender matters. Gend Work Organ. 2008;15:600–20.

McCormack B, van Dulmen S, Eide H, Skovdahl K, Eide T. In: McCormack S, van Dulmen S, Eide H, Skovdahl K, Eide T, editors. Person-centredness in healthcare policy, practice and research. Person-centred healthcare research: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2017.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ferris G, Treadway D, Perrewé P, Brouer R, Douglas C, Lux S. Political skill in organizations. J Manag. 2007;33(3):290–320.

Stewart D, Shamdasani P. Online focus groups. J Advertising. 2017;46(1):48–60.

Gamhewage G, Mahmoud M, Tokar A, Attias M, Mylonas C, Canna S, et al. Digital transformation of face-to-face focus group methodology: engaging a globally dispersed audience to manage institutional change at the World Health Organization. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(5):e28911.

Download references

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to thank the persons who agreed to participate in the focus group discussions. We would also like to thank the research amanuensis Noah Löfqvist for acting as the observer of focus group one, and the Swedish Association of Health Professionals and the University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care for developing and organising the programme.

The study was financed through funding from the University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care (Dnr. GU 2021/995). The funding body had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results, or in writing the manuscript. Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health and Rehabilitation, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Box 455, SE-40530, Gothenburg, Sweden

Qarin Lood & Emmelie Barenfeld

Centre for Person‑Centred Care (GPCC), University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Qarin Lood, Eric Carlström, Charlotte Klinga & Emmelie Barenfeld

Centre for Ageing and Health—AgeCap, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

School of Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Box 457, SE-40530, Gothenburg, Sweden

Eric Carlström

School of Business, Campus Vestfold, University of South-Eastern Norway, Kongsberg, Norway

Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Medical Management Centre, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Charlotte Klinga

Research and Development Unit for Older Persons (FOU nu), Stockholm Health Care Services, Stockholm, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EC and EB were responsible for the conception and design of the study. EC and QL were responsible for the data collection. QL was responsible for data analysis and interpretation, and all authors were involved in the final interpretations and formulation of themes. QL and EB drafted the manuscript, which was revised critically by EC and CK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Qarin Lood .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr. 2022-04052-01). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lood, Q., Carlström, E., Klinga, C. et al. A collaborative endeavour to integrate leadership and person-centred ethics: a focus group study on experiences from developing and realising an educational programme to support the transition towards person-centred care. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 395 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10793-8

Download citation

Received : 16 November 2023

Accepted : 27 February 2024

Published : 29 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10793-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Person-centredness

- Person-centred ethics

- Social care

- Curriculum development

- Implementation

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Transformational Leadership, Ethical Leadership, and Participative Leadership in Predicting Counterproductive Work Behaviors: Evidence From Financial Technology Firms

Stanley y. b. huang.

1 Master Program of Financial Technology, School of Financial Technology, Ming Chuan University, Taipei City, Taiwan

Ming-Way Li

2 Department of Marketing and Logistics Management, College of Business Management, Chihlee University of Technology, New Taipei City, Taiwan

Tai-Wei Chang

3 Graduate School of Resources Management and Decision Science, National Defense University, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Counterproductive work behaviors are a crucial issue for practice and academic because it influences employees’ job performance and career development. The present research conceptualizes Kahn’s employee engagement theory and employs transformational leadership, ethical leadership, and participative leadership as its antecedents to predict counterproductive work behaviors through a latent growth model. The present research collected empirical data of 505 employees of fintech businesses in Great China at three waves over 6 months. The findings revealed that as employees perceived higher transformational leadership, ethical leadership, and participative leadership at the first time point, they may demonstrate more positive growths in employee engagement development behavior, which in turn, caused more negative growths in counterproductive work behaviors. The present research stresses a dynamic model of the three leaderships that can alleviate counterproductive work behaviors through the mediating role of employee engagement over time.

Introduction

Previous empirical studies on the antecedents that can mitigate negative work behaviors in Greater China lack sufficient research ( Lee and Huang, 2019 ; Wen et al., 2020 ; Zeng et al., 2020 ; Lan et al., 2021 ), thereby indicating the importance of exploring key antecedents of counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs) ( Baloch et al., 2017 ; Chen et al., 2017 ; Tziner et al., 2020 ; Yan et al., 2020 ). Moreover, CWBs are an important concept, because CWBs may cause lost productivity and withdrawal. In particular, the employees of fintech firms in Greater China have high levels of pressure in recent decades, because Greater China has become one of the most onerous countries for fintech business ( Dai and Taube, 2019 ). For example, the world’s top one, top three, and top six fintech firms are, respectively, Ant Financial, JD Digits, and Du Xiaoman Financial in Greater China ( KPMG, 2019 ). Therefore, it is crucial to understand which organizational management mechanisms (e.g., leadership) can effectively deal with the CWBs. CWBs denote an employee behavior that harms colleagues or company to respond to strain and give vent to an emotion of disagreement ( Hollinger and Clark, 1983 ). Previous studies have almost examined the antecedents of CWBs using personal variables (e.g., Zhou et al., 2014 ; Bowling and Lyons, 2015 ; Fida et al., 2018 ), so it lacks a complete complementary theory to predict CWBs ( Lasson and Bass, 1997 ). Therefore, the present research borrows from Kahn’s (1990) engagement theory as a theoretical basis to predict CWBs. Employee engagement (EE) denotes that an employee putting all resources into self-concept toward a job role to achieve a high level of performance ( Kahn, 1990 ). The EE is also gradually received the attention of Greater China scholars ( Lan et al., 2020 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Lyu, 2020 ). In addition, Kahn’s (1990) theory has detected three psychological antecedents that can drive an individual to show EE, and the present research suggests transformational leadership (TL), ethical leadership (EL), and participative leadership (PL) as Kahn’s (1990) three psychological antecedents. In particular, the TL, EL, and PL are three leadership styles in different domains. For example, the three leadership styles ( Bass, 1985 ; Brown et al., 2005 ; Somech, 2006 ) are involved employees’ different implementation of TL (e.g., adaptability, new ideas, and job performance), EL (e.g., honesty, fairness, trust, and consideration), and PL (openness, authorization, and autonomy). Although EL has been found it is correlated to the idealized consideration dimension of TL ( Brown et al., 2005 ), the correlation coefficient is trivial (0.19), thereby indicating a significant difference between the TL and EL.

In sum, the present research proposes the theoretical model that higher levels of TL, EL, and PL at the first time point will cause more positive growths in the EE, and more positive growths in the EE will cause more negative growths in CWBs over time. The present research employs the latent growth curve modeling (LGCM) and longitudinal data at three-time points in 6 months to verify the theoretical model of the present research based on Kahn’s (1990) theory, which can also complement past knowledge gaps.

Theory Development and Hypotheses

Kahn’s theory.

EE denotes “simultaneous employment and expression of a person’s preferred self in task behaviors that promote connections to work, others, personal presence (physical, cognitive, and emotional) and full performances” ( Kahn, 1990 , p. 700). That is to say, EE denotes that an employee’s emotional, cognitive, and physical resources into a job to achieve high levels of job performance ( Basinska and Dåderman, 2019 ; Holmberg et al., 2020 ).

Antecedents of EE

In Kahn’s (1990) survey, three psychological states were found to influence an individual’s decision whether to perform EE, containing availability, safety, and meaningfulness. The meaningfulness denotes whether an employee’s self-worth is consistent with the company. Safety denotes whether an employee’s working environment is trustworthy and safe. The availability denotes whether an employee has confidence enough to perform the work. The present research employs TL, EL, and PL as drivers of meaningfulness, safety, and availability.