18 Qualitative Research Examples

Qualitative research is an approach to scientific research that involves using observation to gather and analyze non-numerical, in-depth, and well-contextualized datasets.

It serves as an integral part of academic, professional, and even daily decision-making processes (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

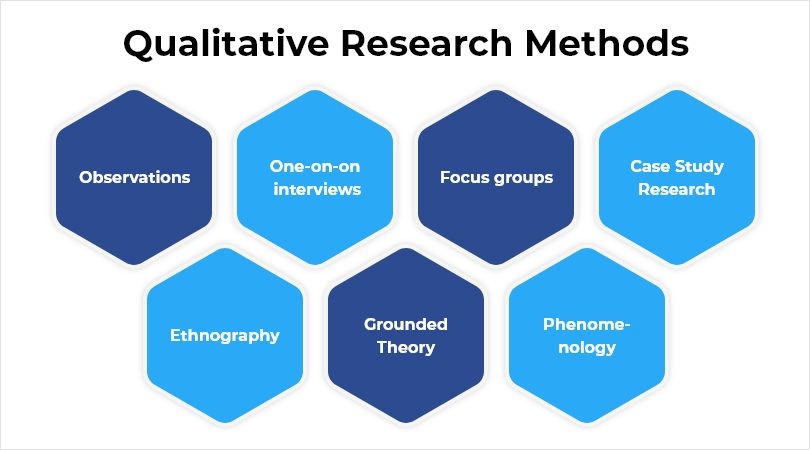

Methods of qualitative research encompass a wide range of techniques, from in-depth personal encounters, like ethnographies (studying cultures in-depth) and autoethnographies (examining one’s own cultural experiences), to collection of diverse perspectives on topics through methods like interviewing focus groups (gatherings of individuals to discuss specific topics).

Qualitative Research Examples

1. ethnography.

Definition: Ethnography is a qualitative research design aimed at exploring cultural phenomena. Rooted in the discipline of anthropology , this research approach investigates the social interactions, behaviors, and perceptions within groups, communities, or organizations.

Ethnographic research is characterized by extended observation of the group, often through direct participation, in the participants’ environment. An ethnographer typically lives with the study group for extended periods, intricately observing their everyday lives (Khan, 2014).

It aims to present a complete, detailed and accurate picture of the observed social life, rituals, symbols, and values from the perspective of the study group.

Example of Ethnographic Research

Title: “ The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity “

Citation: Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Overview: This study by Evans (2010) provides a rich narrative of young adult male identity as experienced in everyday life. The author immersed himself among a group of young men, participating in their activities and cultivating a deep understanding of their lifestyle, values, and motivations. This research exemplified the ethnographic approach, revealing complexities of the subjects’ identities and societal roles, which could hardly be accessed through other qualitative research designs.

Read my Full Guide on Ethnography Here

2. Autoethnography

Definition: Autoethnography is an approach to qualitative research where the researcher uses their own personal experiences to extend the understanding of a certain group, culture, or setting. Essentially, it allows for the exploration of self within the context of social phenomena.

Unlike traditional ethnography, which focuses on the study of others, autoethnography turns the ethnographic gaze inward, allowing the researcher to use their personal experiences within a culture as rich qualitative data (Durham, 2019).

The objective is to critically appraise one’s personal experiences as they navigate and negotiate cultural, political, and social meanings. The researcher becomes both the observer and the participant, intertwining personal and cultural experiences in the research.

Example of Autoethnographic Research

Title: “ A Day In The Life Of An NHS Nurse “

Citation: Osben, J. (2019). A day in the life of a NHS nurse in 21st Century Britain: An auto-ethnography. The Journal of Autoethnography for Health & Social Care. 1(1).

Overview: This study presents an autoethnography of a day in the life of an NHS nurse (who, of course, is also the researcher). The author uses the research to achieve reflexivity, with the researcher concluding: “Scrutinising my practice and situating it within a wider contextual backdrop has compelled me to significantly increase my level of scrutiny into the driving forces that influence my practice.”

Read my Full Guide on Autoethnography Here

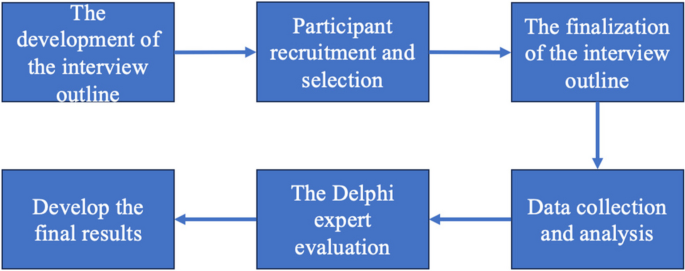

3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Definition: Semi-structured interviews stand as one of the most frequently used methods in qualitative research. These interviews are planned and utilize a set of pre-established questions, but also allow for the interviewer to steer the conversation in other directions based on the responses given by the interviewee.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer prepares a guide that outlines the focal points of the discussion. However, the interview is flexible, allowing for more in-depth probing if the interviewer deems it necessary (Qu, & Dumay, 2011). This style of interviewing strikes a balance between structured ones which might limit the discussion, and unstructured ones, which could lack focus.

Example of Semi-Structured Interview Research

Title: “ Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review “

Citation: Puts, M., et al. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Overview: Puts et al. (2014) executed an extensive systematic review in which they conducted semi-structured interviews with older adults suffering from cancer to examine the factors influencing their adherence to cancer treatment. The findings suggested that various factors, including side effects, faith in healthcare professionals, and social support have substantial impacts on treatment adherence. This research demonstrates how semi-structured interviews can provide rich and profound insights into the subjective experiences of patients.

4. Focus Groups

Definition: Focus groups are a qualitative research method that involves organized discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain their perspectives on a specific concept, product, or phenomenon. Typically, these discussions are guided by a moderator.

During a focus group session, the moderator has a list of questions or topics to discuss, and participants are encouraged to interact with each other (Morgan, 2010). This interactivity can stimulate more information and provide a broader understanding of the issue under scrutiny. The open format allows participants to ask questions and respond freely, offering invaluable insights into attitudes, experiences, and group norms.

Example of Focus Group Research

Title: “ Perspectives of Older Adults on Aging Well: A Focus Group Study “

Citation: Halaweh, H., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., Svantesson, U., & Willén, C. (2018). Perspectives of older adults on aging well: a focus group study. Journal of aging research .

Overview: This study aimed to explore what older adults (aged 60 years and older) perceived to be ‘aging well’. The researchers identified three major themes from their focus group interviews: a sense of well-being, having good physical health, and preserving good mental health. The findings highlight the importance of factors such as positive emotions, social engagement, physical activity, healthy eating habits, and maintaining independence in promoting aging well among older adults.

5. Phenomenology

Definition: Phenomenology, a qualitative research method, involves the examination of lived experiences to gain an in-depth understanding of the essence or underlying meanings of a phenomenon.

The focus of phenomenology lies in meticulously describing participants’ conscious experiences related to the chosen phenomenon (Padilla-Díaz, 2015).

In a phenomenological study, the researcher collects detailed, first-hand perspectives of the participants, typically via in-depth interviews, and then uses various strategies to interpret and structure these experiences, ultimately revealing essential themes (Creswell, 2013). This approach focuses on the perspective of individuals experiencing the phenomenon, seeking to explore, clarify, and understand the meanings they attach to those experiences.

Example of Phenomenology Research

Title: “ A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: current state, promise, and future directions for research ”

Citation: Cilesiz, S. (2011). A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: Current state, promise, and future directions for research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59 , 487-510.

Overview: A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology by Sebnem Cilesiz represents a good starting point for formulating a phenomenological study. With its focus on the ‘essence of experience’, this piece presents methodological, reliability, validity, and data analysis techniques that phenomenologists use to explain how people experience technology in their everyday lives.

6. Grounded Theory

Definition: Grounded theory is a systematic methodology in qualitative research that typically applies inductive reasoning . The primary aim is to develop a theoretical explanation or framework for a process, action, or interaction grounded in, and arising from, empirical data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In grounded theory, data collection and analysis work together in a recursive process. The researcher collects data, analyses it, and then collects more data based on the evolving understanding of the research context. This ongoing process continues until a comprehensive theory that represents the data and the associated phenomenon emerges – a point known as theoretical saturation (Charmaz, 2014).

Example of Grounded Theory Research

Title: “ Student Engagement in High School Classrooms from the Perspective of Flow Theory “

Citation: Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158–176.

Overview: Shernoff and colleagues (2003) used grounded theory to explore student engagement in high school classrooms. The researchers collected data through student self-reports, interviews, and observations. Key findings revealed that academic challenge, student autonomy, and teacher support emerged as the most significant factors influencing students’ engagement, demonstrating how grounded theory can illuminate complex dynamics within real-world contexts.

7. Narrative Research

Definition: Narrative research is a qualitative research method dedicated to storytelling and understanding how individuals experience the world. It focuses on studying an individual’s life and experiences as narrated by that individual (Polkinghorne, 2013).

In narrative research, the researcher collects data through methods such as interviews, observations , and document analysis. The emphasis is on the stories told by participants – narratives that reflect their experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

These stories are then interpreted by the researcher, who attempts to understand the meaning the participant attributes to these experiences (Josselson, 2011).

Example of Narrative Research

Title: “Narrative Structures and the Language of the Self”

Citation: McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative . American Psychological Association.

Overview: In this innovative study, McAdams et al. (2006) employed narrative research to explore how individuals construct their identities through the stories they tell about themselves. By examining personal narratives, the researchers discerned patterns associated with characters, motivations, conflicts, and resolutions, contributing valuable insights about the relationship between narrative and individual identity.

8. Case Study Research

Definition: Case study research is a qualitative research method that involves an in-depth investigation of a single instance or event: a case. These ‘cases’ can range from individuals, groups, or entities to specific projects, programs, or strategies (Creswell, 2013).

The case study method typically uses multiple sources of information for comprehensive contextual analysis. It aims to explore and understand the complexity and uniqueness of a particular case in a real-world context (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). This investigation could result in a detailed description of the case, a process for its development, or an exploration of a related issue or problem.

Example of Case Study Research

Title: “ Teacher’s Role in Fostering Preschoolers’ Computational Thinking: An Exploratory Case Study “

Citation: Wang, X. C., Choi, Y., Benson, K., Eggleston, C., & Weber, D. (2021). Teacher’s role in fostering preschoolers’ computational thinking: An exploratory case study. Early Education and Development , 32 (1), 26-48.

Overview: This study investigates the role of teachers in promoting computational thinking skills in preschoolers. The study utilized a qualitative case study methodology to examine the computational thinking scaffolding strategies employed by a teacher interacting with three preschoolers in a small group setting. The findings highlight the importance of teachers’ guidance in fostering computational thinking practices such as problem reformulation/decomposition, systematic testing, and debugging.

Read about some Famous Case Studies in Psychology Here

9. Participant Observation

Definition: Participant observation has the researcher immerse themselves in a group or community setting to observe the behavior of its members. It is similar to ethnography, but generally, the researcher isn’t embedded for a long period of time.

The researcher, being a participant, engages in daily activities, interactions, and events as a way of conducting a detailed study of a particular social phenomenon (Kawulich, 2005).

The method involves long-term engagement in the field, maintaining detailed records of observed events, informal interviews, direct participation, and reflexivity. This approach allows for a holistic view of the participants’ lived experiences, behaviours, and interactions within their everyday environment (Dewalt, 2011).

Example of Participant Observation Research

Title: Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics

Citation: Heemskerk, E. M., Heemskerk, K., & Wats, M. M. (2017). Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics. Journal of Management & Governance , 21 , 233-263.

Overview: This study examined how conflicts within corporate boards affect their performance. The researchers used a participant observation method, where they actively engaged with 11 supervisory boards and observed their dynamics. They found that having a shared understanding of the board’s role called a common framework, improved performance by reducing relationship conflicts, encouraging task conflicts, and minimizing conflicts between the board and CEO.

10. Non-Participant Observation

Definition: Non-participant observation is a qualitative research method in which the researcher observes the phenomena of interest without actively participating in the situation, setting, or community being studied.

This method allows the researcher to maintain a position of distance, as they are solely an observer and not a participant in the activities being observed (Kawulich, 2005).

During non-participant observation, the researcher typically records field notes on the actions, interactions, and behaviors observed , focusing on specific aspects of the situation deemed relevant to the research question.

This could include verbal and nonverbal communication , activities, interactions, and environmental contexts (Angrosino, 2007). They could also use video or audio recordings or other methods to collect data.

Example of Non-Participant Observation Research

Title: Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non-participant observation study

Citation: Sreeram, A., Cross, W. M., & Townsin, L. (2023). Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery‐oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non‐participant observation study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing .

Overview: This study investigated the attitudes of mental health nurses towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units. The researchers used a non-participant observation method, meaning they observed the nurses without directly participating in their activities. The findings shed light on the nurses’ perspectives and behaviors, providing valuable insights into their attitudes toward mental health and recovery-focused care in these settings.

11. Content Analysis

Definition: Content Analysis involves scrutinizing textual, visual, or spoken content to categorize and quantify information. The goal is to identify patterns, themes, biases, or other characteristics (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Content Analysis is widely used in various disciplines for a multitude of purposes. Researchers typically use this method to distill large amounts of unstructured data, like interview transcripts, newspaper articles, or social media posts, into manageable and meaningful chunks.

When wielded appropriately, Content Analysis can illuminate the density and frequency of certain themes within a dataset, provide insights into how specific terms or concepts are applied contextually, and offer inferences about the meanings of their content and use (Duriau, Reger, & Pfarrer, 2007).

Example of Content Analysis

Title: Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news .

Citation: Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50 (2), 93-109.

Overview: This study analyzed press and television news articles about European politics using a method called content analysis. The researchers examined the prevalence of different “frames” in the news, which are ways of presenting information to shape audience perceptions. They found that the most common frames were attribution of responsibility, conflict, economic consequences, human interest, and morality.

Read my Full Guide on Content Analysis Here

12. Discourse Analysis

Definition: Discourse Analysis, a qualitative research method, interprets the meanings, functions, and coherence of certain languages in context.

Discourse analysis is typically understood through social constructionism, critical theory , and poststructuralism and used for understanding how language constructs social concepts (Cheek, 2004).

Discourse Analysis offers great breadth, providing tools to examine spoken or written language, often beyond the level of the sentence. It enables researchers to scrutinize how text and talk articulate social and political interactions and hierarchies.

Insight can be garnered from different conversations, institutional text, and media coverage to understand how topics are addressed or framed within a specific social context (Jorgensen & Phillips, 2002).

Example of Discourse Analysis

Title: The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis

Citation: Thomas, S. (2005). The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis. Critical Studies in Education, 46 (2), 25-44.

Overview: The author examines how an education policy in one state of Australia positions teacher professionalism and teacher identities. While there are competing discourses about professional identity, the policy framework privileges a narrative that frames the ‘good’ teacher as one that accepts ever-tightening control and regulation over their professional practice.

Read my Full Guide on Discourse Analysis Here

13. Action Research

Definition: Action Research is a qualitative research technique that is employed to bring about change while simultaneously studying the process and results of that change.

This method involves a cyclical process of fact-finding, action, evaluation, and reflection (Greenwood & Levin, 2016).

Typically, Action Research is used in the fields of education, social sciences , and community development. The process isn’t just about resolving an issue but also developing knowledge that can be used in the future to address similar or related problems.

The researcher plays an active role in the research process, which is normally broken down into four steps:

- developing a plan to improve what is currently being done

- implementing the plan

- observing the effects of the plan, and

- reflecting upon these effects (Smith, 2010).

Example of Action Research

Title: Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing

Citation: Ellison, M., & Drew, C. (2020). Using digital sandbox gaming to improve creativity within boys’ writing. Journal of Research in Childhood Education , 34 (2), 277-287.

Overview: This was a research study one of my research students completed in his own classroom under my supervision. He implemented a digital game-based approach to literacy teaching with boys and interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience.

Read my Full Guide on Action Research Here

14. Semiotic Analysis

Definition: Semiotic Analysis is a qualitative method of research that interprets signs and symbols in communication to understand sociocultural phenomena. It stems from semiotics, the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation (Chandler, 2017).

In a Semiotic Analysis, signs (anything that represents something else) are interpreted based on their significance and the role they play in representing ideas.

This type of research often involves the examination of images, sounds, and word choice to uncover the embedded sociocultural meanings. For example, an advertisement for a car might be studied to learn more about societal views on masculinity or success (Berger, 2010).

Example of Semiotic Research

Title: Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia

Citation: Symes, C. (2023). Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia. Semiotica , 2023 (250), 167-190.

Overview: This study examines school badges in New South Wales, Australia, and explores their significance through a semiotic analysis. The badges, which are part of the school’s visual identity, are seen as symbolic representations that convey meanings. The analysis reveals that these badges often draw on heraldic models, incorporating elements like colors, names, motifs, and mottoes that reflect local culture and history, thus connecting students to their national identity. Additionally, the study highlights how some schools have shifted from traditional badges to modern logos and slogans, reflecting a more business-oriented approach.

15. Qualitative Longitudinal Studies

Definition: Qualitative Longitudinal Studies are a research method that involves repeated observation of the same items over an extended period of time.

Unlike a snapshot perspective, this method aims to piece together individual histories and examine the influences and impacts of change (Neale, 2019).

Qualitative Longitudinal Studies provide an in-depth understanding of change as it happens, including changes in people’s lives, their perceptions, and their behaviors.

For instance, this method could be used to follow a group of students through their schooling years to understand the evolution of their learning behaviors and attitudes towards education (Saldaña, 2003).

Example of Qualitative Longitudinal Research

Title: Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study

Citation: Hackett, J., Godfrey, M., & Bennett, M. I. (2016). Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliative medicine , 30 (8), 711-719.

Overview: This article examines how patients and their caregivers manage pain in advanced cancer through a qualitative longitudinal study. The researchers interviewed patients and caregivers at two different time points and collected audio diaries to gain insights into their experiences, making this study longitudinal.

Read my Full Guide on Longitudinal Research Here

16. Open-Ended Surveys

Definition: Open-Ended Surveys are a type of qualitative research method where respondents provide answers in their own words. Unlike closed-ended surveys, which limit responses to predefined options, open-ended surveys allow for expansive and unsolicited explanations (Fink, 2013).

Open-ended surveys are commonly used in a range of fields, from market research to social studies. As they don’t force respondents into predefined response categories, these surveys help to draw out rich, detailed data that might uncover new variables or ideas.

For example, an open-ended survey might be used to understand customer opinions about a new product or service (Lavrakas, 2008).

Contrast this to a quantitative closed-ended survey, like a Likert scale, which could theoretically help us to come up with generalizable data but is restricted by the questions on the questionnaire, meaning new and surprising data and insights can’t emerge from the survey results in the same way.

Example of Open-Ended Survey Research

Title: Advantages and disadvantages of technology in relationships: Findings from an open-ended survey

Citation: Hertlein, K. M., & Ancheta, K. (2014). Advantages and disadvantages of technology in relationships: Findings from an open-ended survey. The Qualitative Report , 19 (11), 1-11.

Overview: This article examines the advantages and disadvantages of technology in couple relationships through an open-ended survey method. Researchers analyzed responses from 410 undergraduate students to understand how technology affects relationships. They found that technology can contribute to relationship development, management, and enhancement, but it can also create challenges such as distancing, lack of clarity, and impaired trust.

17. Naturalistic Observation

Definition: Naturalistic Observation is a type of qualitative research method that involves observing individuals in their natural environments without interference or manipulation by the researcher.

Naturalistic observation is often used when conducting research on behaviors that cannot be controlled or manipulated in a laboratory setting (Kawulich, 2005).

It is frequently used in the fields of psychology, sociology, and anthropology. For instance, to understand the social dynamics in a schoolyard, a researcher could spend time observing the children interact during their recess, noting their behaviors, interactions, and conflicts without imposing their presence on the children’s activities (Forsyth, 2010).

Example of Naturalistic Observation Research

Title: Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study

Citation: Kaplan, D. M., Raison, C. L., Milek, A., Tackman, A. M., Pace, T. W., & Mehl, M. R. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study. PloS one , 13 (11), e0206029.

Overview: In this study, researchers conducted two studies: one exploring assumptions about mindfulness and behavior, and the other using naturalistic observation to examine actual behavioral manifestations of mindfulness. They found that trait mindfulness is associated with a heightened perceptual focus in conversations, suggesting that being mindful is expressed primarily through sharpened attention rather than observable behavioral or social differences.

Read my Full Guide on Naturalistic Observation Here

18. Photo-Elicitation

Definition: Photo-elicitation utilizes photographs as a means to trigger discussions and evoke responses during interviews. This strategy aids in bringing out topics of discussion that may not emerge through verbal prompting alone (Harper, 2002).

Traditionally, Photo-Elicitation has been useful in various fields such as education, psychology, and sociology. The method involves the researcher or participants taking photographs, which are then used as prompts for discussion.

For instance, a researcher studying urban environmental issues might invite participants to photograph areas in their neighborhood that they perceive as environmentally detrimental, and then discuss each photo in depth (Clark-Ibáñez, 2004).

Example of Photo-Elicitation Research

Title: Early adolescent food routines: A photo-elicitation study

Citation: Green, E. M., Spivak, C., & Dollahite, J. S. (2021). Early adolescent food routines: A photo-elicitation study. Appetite, 158 .

Overview: This study focused on early adolescents (ages 10-14) and their food routines. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews using a photo-elicitation approach, where participants took photos related to their food choices and experiences. Through analysis, the study identified various routines and three main themes: family, settings, and meals/foods consumed, revealing how early adolescents view and are influenced by their eating routines.

Features of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a research method focused on understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013).

Some key features of this method include:

- Naturalistic Inquiry: Qualitative research happens in the natural setting of the phenomena, aiming to understand “real world” situations (Patton, 2015). This immersion in the field or subject allows the researcher to gather a deep understanding of the subject matter.

- Emphasis on Process: It aims to understand how events unfold over time rather than focusing solely on outcomes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). The process-oriented nature of qualitative research allows researchers to investigate sequences, timing, and changes.

- Interpretive: It involves interpreting and making sense of phenomena in terms of the meanings people assign to them (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). This interpretive element allows for rich, nuanced insights into human behavior and experiences.

- Holistic Perspective: Qualitative research seeks to understand the whole phenomenon rather than focusing on individual components (Creswell, 2013). It emphasizes the complex interplay of factors, providing a richer, more nuanced view of the research subject.

- Prioritizes Depth over Breadth: Qualitative research favors depth of understanding over breadth, typically involving a smaller but more focused sample size (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2020). This enables detailed exploration of the phenomena of interest, often leading to rich and complex data.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

Qualitative research centers on exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013).

It involves an in-depth approach to the subject matter, aiming to capture the richness and complexity of human experience.

Examples include conducting interviews, observing behaviors, or analyzing text and images.

There are strengths inherent in this approach. In its focus on understanding subjective experiences and interpretations, qualitative research can yield rich and detailed data that quantitative research may overlook (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011).

Additionally, qualitative research is adaptive, allowing the researcher to respond to new directions and insights as they emerge during the research process.

However, there are also limitations. Because of the interpretive nature of this research, findings may not be generalizable to a broader population (Marshall & Rossman, 2014). Well-designed quantitative research, on the other hand, can be generalizable.

Moreover, the reliability and validity of qualitative data can be challenging to establish due to its subjective nature, unlike quantitative research, which is ideally more objective.

Compare Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methodologies in This Guide Here

In conclusion, qualitative research methods provide distinctive ways to explore social phenomena and understand nuances that quantitative approaches might overlook. Each method, from Ethnography to Photo-Elicitation, presents its strengths and weaknesses but they all offer valuable means of investigating complex, real-world situations. The goal for the researcher is not to find a definitive tool, but to employ the method best suited for their research questions and the context at hand (Almalki, 2016). Above all, these methods underscore the richness of human experience and deepen our understanding of the world around us.

Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing ethnographic and observational research. Sage Publications.

Areni, C. S., & Kim, D. (1994). The influence of in-store lighting on consumers’ examination of merchandise in a wine store. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 11 (2), 117-125.

Barker, C., Pistrang, N., & Elliott, R. (2016). Research Methods in Clinical Psychology: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. John Wiley & Sons.

Baxter, P. & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13 (4), 544-559.

Berger, A. A. (2010). The Objects of Affection: Semiotics and Consumer Culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bevan, M. T. (2014). A method of phenomenological interviewing. Qualitative health research, 24 (1), 136-144.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage Publications.

Bryman, A. (2015) . The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications.

Chandler, D. (2017). Semiotics: The Basics. Routledge.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

Cheek, J. (2004). At the margins? Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 14(8), 1140-1150.

Clark-Ibáñez, M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1507-1527.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(100), 1-9.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Dewalt, K. M., & Dewalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Rowman Altamira.

Doody, O., Slevin, E., & Taggart, L. (2013). Focus group interviews in nursing research: part 1. British Journal of Nursing, 22(1), 16-19.

Durham, A. (2019). Autoethnography. In P. Atkinson (Ed.), Qualitative Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

Duriau, V. J., Reger, R. K., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2007). A content analysis of the content analysis literature in organization studies: Research themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 5-34.

Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Farrall, S. (2006). What is qualitative longitudinal research? Papers in Social Research Methods, Qualitative Series, No.11, London School of Economics, Methodology Institute.

Fielding, J., & Fielding, N. (2008). Synergy and synthesis: integrating qualitative and quantitative data. The SAGE handbook of social research methods, 555-571.

Fink, A. (2013). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide . SAGE.

Forsyth, D. R. (2010). Group Dynamics . Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Fugard, A. J. B., & Potts, H. W. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18 (6), 669–684.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

Gray, J. R., Grove, S. K., & Sutherland, S. (2017). Burns and Grove’s the Practice of Nursing Research E-Book: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Greenwood, D. J., & Levin, M. (2016). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change. SAGE.

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17 (1), 13-26.

Heinonen, T. (2012). Making Sense of the Social: Human Sciences and the Narrative Turn. Rozenberg Publishers.

Heisley, D. D., & Levy, S. J. (1991). Autodriving: A photoelicitation technique. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (3), 257-272.

Hennink, M. M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative Research Methods . SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15 (9), 1277–1288.

Jorgensen, D. L. (2015). Participant Observation. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jorgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method . SAGE.

Josselson, R. (2011). Narrative research: Constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing story. In Five ways of doing qualitative analysis . Guilford Press.

Kawulich, B. B. (2005). Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6 (2).

Khan, S. (2014). Qualitative Research Method: Grounded Theory. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5 (4), 86-88.

Koshy, E., Koshy, V., & Waterman, H. (2010). Action Research in Healthcare . SAGE.

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. SAGE.

Lannon, J., & Cooper, P. (2012). Humanistic Advertising: A Holistic Cultural Perspective. International Journal of Advertising, 15 (2), 97–111.

Lavrakas, P. J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods. SAGE Publications.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (2008). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and interpretation. Sage Publications.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2015). Second language research: Methodology and design. Routledge.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2014). Designing qualitative research. Sage publications.

McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. American Psychological Association.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Mick, D. G. (1986). Consumer Research and Semiotics: Exploring the Morphology of Signs, Symbols, and Significance. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (2), 196-213.

Morgan, D. L. (2010). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Mulhall, A. (2003). In the field: notes on observation in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41 (3), 306-313.

Neale, B. (2019). What is Qualitative Longitudinal Research? Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nolan, L. B., & Renderos, T. B. (2012). A focus group study on the influence of fatalism and religiosity on cancer risk perceptions in rural, eastern North Carolina. Journal of religion and health, 51 (1), 91-104.

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in educational qualitative research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science? International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1 (2), 101-110.

Parker, I. (2014). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology . Routledge.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage Publications.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2013). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. In Life history and narrative. Routledge.

Puts, M. T., Tapscott, B., Fitch, M., Howell, D., Monette, J., Wan-Chow-Wah, D., Krzyzanowska, M., Leighl, N. B., Springall, E., & Alibhai, S. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview . Qualitative research in accounting & management.

Ali, J., & Bhaskar, S. B. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 662–669.

Rosenbaum, M. S. (2017). Exploring the social supportive role of third places in consumers’ lives. Journal of Service Research, 20 (1), 26-42.

Saldaña, J. (2003). Longitudinal Qualitative Research: Analyzing Change Through Time . AltaMira Press.

Saldaña, J. (2014). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. SAGE.

Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158-176.

Smith, J. A. (2015). Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods . Sage Publications.

Smith, M. K. (2010). Action Research. The encyclopedia of informal education.

Sue, V. M., & Ritter, L. A. (2012). Conducting online surveys . SAGE Publications.

Van Auken, P. M., Frisvoll, S. J., & Stewart, S. I. (2010). Visualising community: using participant-driven photo-elicitation for research and application. Local Environment, 15 (4), 373-388.

Van Voorhis, F. L., & Morgan, B. L. (2007). Understanding Power and Rules of Thumb for Determining Sample Sizes. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3 (2), 43–50.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2015). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis . SAGE.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2018). Action research for developing educational theories and practices . Routledge.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Qualitative Research Methods: Types, Analysis + Examples

Qualitative research is based on the disciplines of social sciences like psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Therefore, the qualitative research methods allow for in-depth and further probing and questioning of respondents based on their responses. The interviewer/researcher also tries to understand their motivation and feelings. Understanding how your audience makes decisions can help derive conclusions in market research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as a market research method that focuses on obtaining data through open-ended and conversational communication .

This method is about “what” people think and “why” they think so. For example, consider a convenience store looking to improve its patronage. A systematic observation concludes that more men are visiting this store. One good method to determine why women were not visiting the store is conducting an in-depth interview method with potential customers.

For example, after successfully interviewing female customers and visiting nearby stores and malls, the researchers selected participants through random sampling . As a result, it was discovered that the store didn’t have enough items for women.

So fewer women were visiting the store, which was understood only by personally interacting with them and understanding why they didn’t visit the store because there were more male products than female ones.

Gather research insights

Types of qualitative research methods with examples

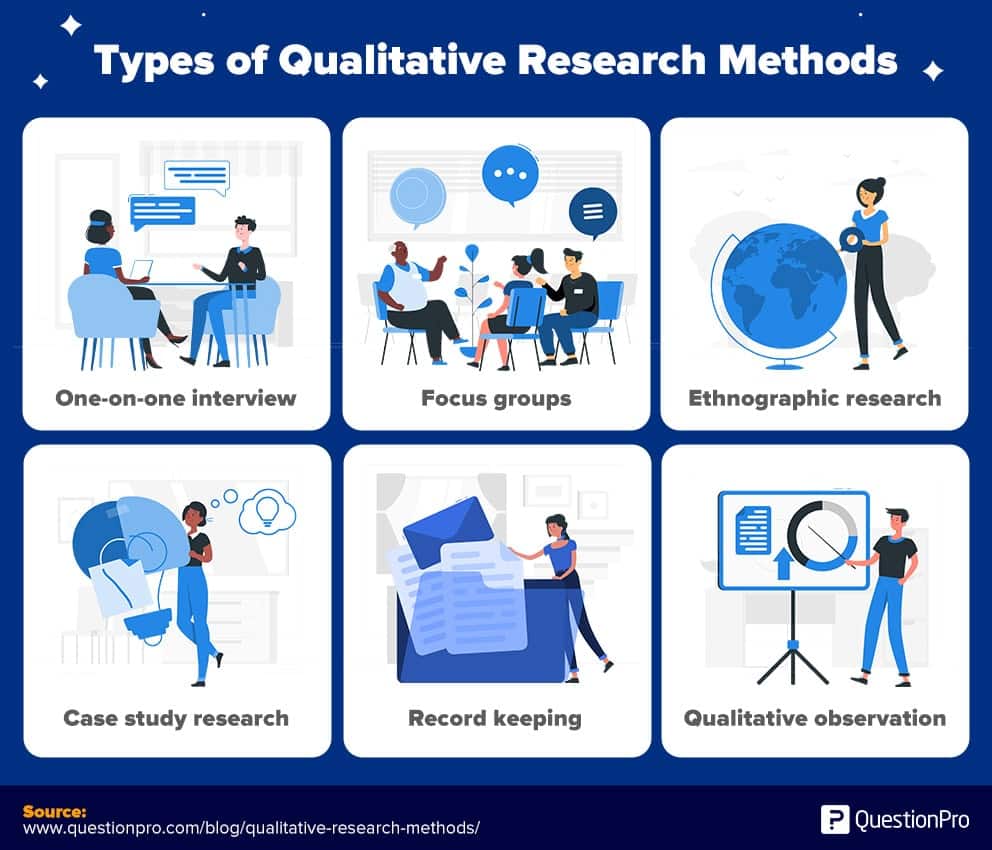

Qualitative research methods are designed in a manner that helps reveal the behavior and perception of a target audience with reference to a particular topic. There are different types of qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, ethnographic research, content analysis, and case study research that are usually used.

The results of qualitative methods are more descriptive, and the inferences can be drawn quite easily from the obtained data .

Qualitative research methods originated in the social and behavioral research sciences. Today, our world is more complicated, and it is difficult to understand what people think and perceive. Online research methods make it easier to understand that as it is a more communicative and descriptive analysis .

The following are the qualitative research methods that are frequently used. Also, read about qualitative research examples :

1. One-on-one interview

Conducting in-depth interviews is one of the most common qualitative research methods. It is a personal interview that is carried out with one respondent at a time. This is purely a conversational method and invites opportunities to get details in depth from the respondent.

One of the advantages of this method is that it provides a great opportunity to gather precise data about what people believe and their motivations . If the researcher is well experienced, asking the right questions can help him/her collect meaningful data. If they should need more information, the researchers should ask such follow-up questions that will help them collect more information.

These interviews can be performed face-to-face or on the phone and usually can last between half an hour to two hours or even more. When the in-depth interview is conducted face to face, it gives a better opportunity to read the respondents’ body language and match the responses.

2. Focus groups

A focus group is also a commonly used qualitative research method used in data collection. A focus group usually includes a limited number of respondents (6-10) from within your target market.

The main aim of the focus group is to find answers to the “why, ” “what,” and “how” questions. One advantage of focus groups is you don’t necessarily need to interact with the group in person. Nowadays, focus groups can be sent an online survey on various devices, and responses can be collected at the click of a button.

Focus groups are an expensive method as compared to other online qualitative research methods. Typically, they are used to explain complex processes. This method is very useful for market research on new products and testing new concepts.

3. Ethnographic research

Ethnographic research is the most in-depth observational research method that studies people in their naturally occurring environment.

This method requires the researchers to adapt to the target audiences’ environments, which could be anywhere from an organization to a city or any remote location. Here, geographical constraints can be an issue while collecting data.

This research design aims to understand the cultures, challenges, motivations, and settings that occur. Instead of relying on interviews and discussions, you experience the natural settings firsthand.

This type of research method can last from a few days to a few years, as it involves in-depth observation and collecting data on those grounds. It’s a challenging and time-consuming method and solely depends on the researcher’s expertise to analyze, observe, and infer the data.

4. Case study research

T he case study method has evolved over the past few years and developed into a valuable quality research method. As the name suggests, it is used for explaining an organization or an entity.

This type of research method is used within a number of areas like education, social sciences, and similar. This method may look difficult to operate; however , it is one of the simplest ways of conducting research as it involves a deep dive and thorough understanding of the data collection methods and inferring the data.

5. Record keeping

This method makes use of the already existing reliable documents and similar sources of information as the data source. This data can be used in new research. This is similar to going to a library. There, one can go over books and other reference material to collect relevant data that can likely be used in the research.

6. Process of observation

Qualitative Observation is a process of research that uses subjective methodologies to gather systematic information or data. Since the focus on qualitative observation is the research process of using subjective methodologies to gather information or data. Qualitative observation is primarily used to equate quality differences.

Qualitative observation deals with the 5 major sensory organs and their functioning – sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing. This doesn’t involve measurements or numbers but instead characteristics.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research: data collection and analysis

A. qualitative data collection.

Qualitative data collection allows collecting data that is non-numeric and helps us to explore how decisions are made and provide us with detailed insight. For reaching such conclusions the data that is collected should be holistic, rich, and nuanced and findings to emerge through careful analysis.

- Whatever method a researcher chooses for collecting qualitative data, one aspect is very clear the process will generate a large amount of data. In addition to the variety of methods available, there are also different methods of collecting and recording the data.

For example, if the qualitative data is collected through a focus group or one-to-one discussion, there will be handwritten notes or video recorded tapes. If there are recording they should be transcribed and before the process of data analysis can begin.

- As a rough guide, it can take a seasoned researcher 8-10 hours to transcribe the recordings of an interview, which can generate roughly 20-30 pages of dialogues. Many researchers also like to maintain separate folders to maintain the recording collected from the different focus group. This helps them compartmentalize the data collected.

- In case there are running notes taken, which are also known as field notes, they are helpful in maintaining comments, environmental contexts, environmental analysis , nonverbal cues etc. These filed notes are helpful and can be compared while transcribing audio recorded data. Such notes are usually informal but should be secured in a similar manner as the video recordings or the audio tapes.

B. Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative data analysis such as notes, videos, audio recordings images, and text documents. One of the most used methods for qualitative data analysis is text analysis.

Text analysis is a data analysis method that is distinctly different from all other qualitative research methods, where researchers analyze the social life of the participants in the research study and decode the words, actions, etc.

There are images also that are used in this research study and the researchers analyze the context in which the images are used and draw inferences from them. In the last decade, text analysis through what is shared on social media platforms has gained supreme popularity.

Characteristics of qualitative research methods

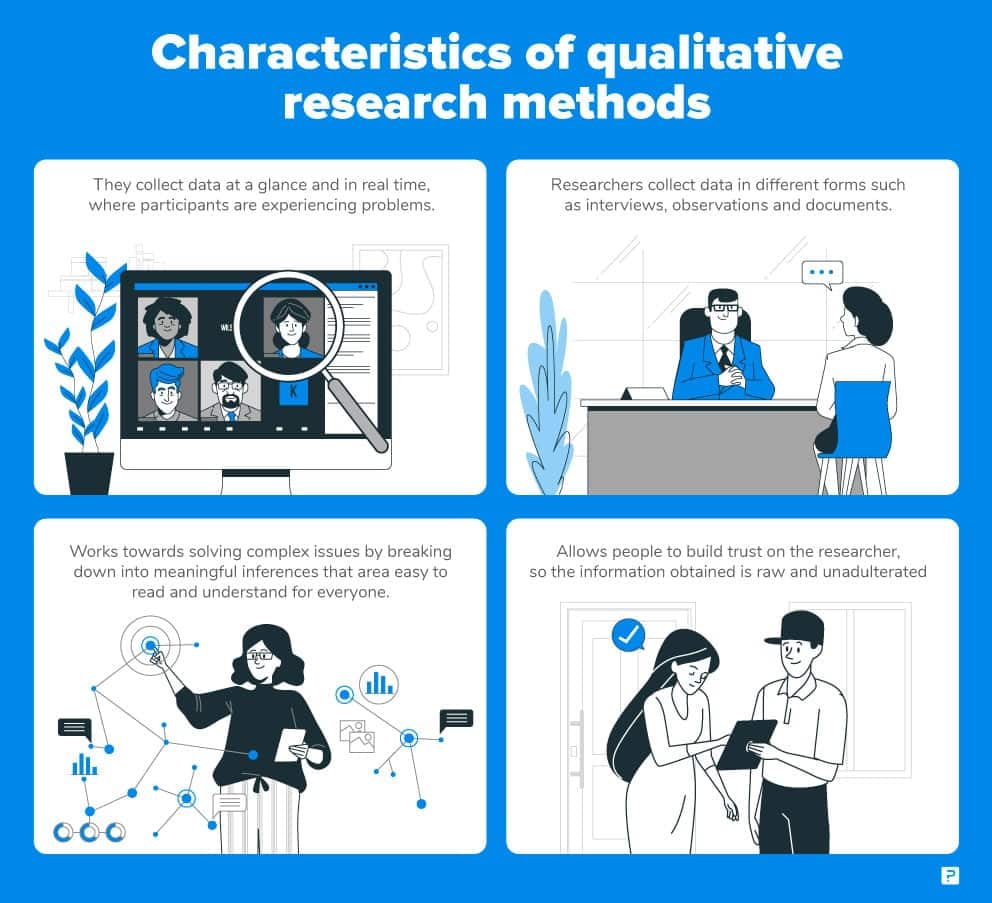

- Qualitative research methods usually collect data at the sight, where the participants are experiencing issues or research problems . These are real-time data and rarely bring the participants out of the geographic locations to collect information.

- Qualitative researchers typically gather multiple forms of data, such as interviews, observations, and documents, rather than rely on a single data source .

- This type of research method works towards solving complex issues by breaking down into meaningful inferences, that is easily readable and understood by all.

- Since it’s a more communicative method, people can build their trust on the researcher and the information thus obtained is raw and unadulterated.

Qualitative research method case study

Let’s take the example of a bookstore owner who is looking for ways to improve their sales and customer outreach. An online community of members who were loyal patrons of the bookstore were interviewed and related questions were asked and the questions were answered by them.

At the end of the interview, it was realized that most of the books in the stores were suitable for adults and there were not enough options for children or teenagers.

By conducting this qualitative research the bookstore owner realized what the shortcomings were and what were the feelings of the readers. Through this research now the bookstore owner can now keep books for different age categories and can improve his sales and customer outreach.

Such qualitative research method examples can serve as the basis to indulge in further quantitative research , which provides remedies.

When to use qualitative research

Researchers make use of qualitative research techniques when they need to capture accurate, in-depth insights. It is very useful to capture “factual data”. Here are some examples of when to use qualitative research.

- Developing a new product or generating an idea.

- Studying your product/brand or service to strengthen your marketing strategy.

- To understand your strengths and weaknesses.

- Understanding purchase behavior.

- To study the reactions of your audience to marketing campaigns and other communications.

- Exploring market demographics, segments, and customer care groups.

- Gathering perception data of a brand, company, or product.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research methods vs quantitative research methods

The basic differences between qualitative research methods and quantitative research methods are simple and straightforward. They differ in:

- Their analytical objectives

- Types of questions asked

- Types of data collection instruments

- Forms of data they produce

- Degree of flexibility

LEARN MORE ABOUR OUR SOFTWARE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

21 Best Customer Advocacy Software for Customers in 2024

Apr 19, 2024

10 Quantitative Data Analysis Software for Every Data Scientist

Apr 18, 2024

11 Best Enterprise Feedback Management Software in 2024

17 Best Online Reputation Management Software in 2024

Apr 17, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Qualitative research: methods and examples

Last updated

13 April 2023

Reviewed by

Qualitative research involves gathering and evaluating non-numerical information to comprehend concepts, perspectives, and experiences. It’s also helpful for obtaining in-depth insights into a certain subject or generating new research ideas.

As a result, qualitative research is practical if you want to try anything new or produce new ideas.

There are various ways you can conduct qualitative research. In this article, you'll learn more about qualitative research methodologies, including when you should use them.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a broad term describing various research types that rely on asking open-ended questions. Qualitative research investigates “how” or “why” certain phenomena occur. It is about discovering the inherent nature of something.

The primary objective of qualitative research is to understand an individual's ideas, points of view, and feelings. In this way, collecting in-depth knowledge of a specific topic is possible. Knowing your audience's feelings about a particular subject is important for making reasonable research conclusions.

Unlike quantitative research , this approach does not involve collecting numerical, objective data for statistical analysis. Qualitative research is used extensively in education, sociology, health science, history, and anthropology.

- Types of qualitative research methodology

Typically, qualitative research aims at uncovering the attitudes and behavior of the target audience concerning a specific topic. For example, “How would you describe your experience as a new Dovetail user?”

Some of the methods for conducting qualitative analysis include:

Focus groups

Hosting a focus group is a popular qualitative research method. It involves obtaining qualitative data from a limited sample of participants. In a moderated version of a focus group, the moderator asks participants a series of predefined questions. They aim to interact and build a group discussion that reveals their preferences, candid thoughts, and experiences.

Unmoderated, online focus groups are increasingly popular because they eliminate the need to interact with people face to face.

Focus groups can be more cost-effective than 1:1 interviews or studying a group in a natural setting and reporting one’s observations.

Focus groups make it possible to gather multiple points of view quickly and efficiently, making them an excellent choice for testing new concepts or conducting market research on a new product.

However, there are some potential drawbacks to this method. It may be unsuitable for sensitive or controversial topics. Participants might be reluctant to disclose their true feelings or respond falsely to conform to what they believe is the socially acceptable answer (known as response bias).

Case study research

A case study is an in-depth evaluation of a specific person, incident, organization, or society. This type of qualitative research has evolved into a broadly applied research method in education, law, business, and the social sciences.

Even though case study research may appear challenging to implement, it is one of the most direct research methods. It requires detailed analysis, broad-ranging data collection methodologies, and a degree of existing knowledge about the subject area under investigation.

Historical model

The historical approach is a distinct research method that deeply examines previous events to better understand the present and forecast future occurrences of the same phenomena. Its primary goal is to evaluate the impacts of history on the present and hence discover comparable patterns in the present to predict future outcomes.

Oral history

This qualitative data collection method involves gathering verbal testimonials from individuals about their personal experiences. It is widely used in historical disciplines to offer counterpoints to established historical facts and narratives. The most common methods of gathering oral history are audio recordings, analysis of auto-biographical text, videos, and interviews.

Qualitative observation

One of the most fundamental, oldest research methods, qualitative observation , is the process through which a researcher collects data using their senses of sight, smell, hearing, etc. It is used to observe the properties of the subject being studied. For example, “What does it look like?” As research methods go, it is subjective and depends on researchers’ first-hand experiences to obtain information, so it is prone to bias. However, it is an excellent way to start a broad line of inquiry like, “What is going on here?”

Record keeping and review

Record keeping uses existing documents and relevant data sources that can be employed for future studies. It is equivalent to visiting the library and going through publications or any other reference material to gather important facts that will likely be used in the research.

Grounded theory approach

The grounded theory approach is a commonly used research method employed across a variety of different studies. It offers a unique way to gather, interpret, and analyze. With this approach, data is gathered and analyzed simultaneously. Existing analysis frames and codes are disregarded, and data is analyzed inductively, with new codes and frames generated from the research.

Ethnographic research

Ethnography is a descriptive form of a qualitative study of people and their cultures. Its primary goal is to study people's behavior in their natural environment. This method necessitates that the researcher adapts to their target audience's setting.

Thereby, you will be able to understand their motivation, lifestyle, ambitions, traditions, and culture in situ. But, the researcher must be prepared to deal with geographical constraints while collecting data i.e., audiences can’t be studied in a laboratory or research facility.

This study can last from a couple of days to several years. Thus, it is time-consuming and complicated, requiring you to have both the time to gather the relevant data as well as the expertise in analyzing, observing, and interpreting data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Narrative framework

A narrative framework is a qualitative research approach that relies on people's written text or visual images. It entails people analyzing these events or narratives to determine certain topics or issues. With this approach, you can understand how people represent themselves and their experiences to a larger audience.

Phenomenological approach

The phenomenological study seeks to investigate the experiences of a particular phenomenon within a group of individuals or communities. It analyzes a certain event through interviews with persons who have witnessed it to determine the connections between their views. Even though this method relies heavily on interviews, other data sources (recorded notes), and observations could be employed to enhance the findings.

- Qualitative research methods (tools)

Some of the instruments involved in qualitative research include:

Document research: Also known as document analysis because it involves evaluating written documents. These can include personal and non-personal materials like archives, policy publications, yearly reports, diaries, or letters.

Focus groups: This is where a researcher poses questions and generates conversation among a group of people. The major goal of focus groups is to examine participants' experiences and knowledge, including research into how and why individuals act in various ways.

Secondary study: Involves acquiring existing information from texts, images, audio, or video recordings.

Observations: This requires thorough field notes on everything you see, hear, or experience. Compared to reported conduct or opinion, this study method can assist you in getting insights into a specific situation and observable behaviors.

Structured interviews : In this approach, you will directly engage people one-on-one. Interviews are ideal for learning about a person's subjective beliefs, motivations, and encounters.

Surveys: This is when you distribute questionnaires containing open-ended questions

- What are common examples of qualitative research?

Everyday examples of qualitative research include:

Conducting a demographic analysis of a business

For instance, suppose you own a business such as a grocery store (or any store) and believe it caters to a broad customer base, but after conducting a demographic analysis, you discover that most of your customers are men.

You could do 1:1 interviews with female customers to learn why they don't shop at your store.

In this case, interviewing potential female customers should clarify why they don't find your shop appealing. It could be because of the products you sell or a need for greater brand awareness, among other possible reasons.

Launching or testing a new product

Suppose you are the product manager at a SaaS company looking to introduce a new product. Focus groups can be an excellent way to determine whether your product is marketable.

In this instance, you could hold a focus group with a sample group drawn from your intended audience. The group will explore the product based on its new features while you ensure adequate data on how users react to the new features. The data you collect will be key to making sales and marketing decisions.

Conducting studies to explain buyers' behaviors

You can also use qualitative research to understand existing buyer behavior better. Marketers analyze historical information linked to their businesses and industries to see when purchasers buy more.

Qualitative research can help you determine when to target new clients and peak seasons to boost sales by investigating the reason behind these behaviors.

- Qualitative research: data collection

Data collection is gathering information on predetermined variables to gain appropriate answers, test hypotheses, and analyze results. Researchers will collect non-numerical data for qualitative data collection to obtain detailed explanations and draw conclusions.

To get valid findings and achieve a conclusion in qualitative research, researchers must collect comprehensive and multifaceted data.

Qualitative data is usually gathered through interviews or focus groups with videotapes or handwritten notes. If there are recordings, they are transcribed before the data analysis process. Researchers keep separate folders for the recordings acquired from each focus group when collecting qualitative research data to categorize the data.

- Qualitative research: data analysis

Qualitative data analysis is organizing, examining, and interpreting qualitative data. Its main objective is identifying trends and patterns, responding to research questions, and recommending actions based on the findings. Textual analysis is a popular method for analyzing qualitative data.

Textual analysis differs from other qualitative research approaches in that researchers consider the social circumstances of study participants to decode their words, behaviors, and broader meaning.

Learn more about qualitative research data analysis software

- When to use qualitative research

Qualitative research is helpful in various situations, particularly when a researcher wants to capture accurate, in-depth insights.

Here are some instances when qualitative research can be valuable:

Examining your product or service to improve your marketing approach

When researching market segments, demographics, and customer service teams

Identifying client language when you want to design a quantitative survey

When attempting to comprehend your or someone else's strengths and weaknesses

Assessing feelings and beliefs about societal and public policy matters

Collecting information about a business or product's perception

Analyzing your target audience's reactions to marketing efforts

When launching a new product or coming up with a new idea

When seeking to evaluate buyers' purchasing patterns

- Qualitative research methods vs. quantitative research methods

Qualitative research examines people's ideas and what influences their perception, whereas quantitative research draws conclusions based on numbers and measurements.

Qualitative research is descriptive, and its primary goal is to comprehensively understand people's attitudes, behaviors, and ideas.

In contrast, quantitative research is more restrictive because it relies on numerical data and analyzes statistical data to make decisions. This research method assists researchers in gaining an initial grasp of the subject, which deals with numbers. For instance, the number of customers likely to purchase your products or use your services.

What is the most important feature of qualitative research?

A distinguishing feature of qualitative research is that it’s conducted in a real-world setting instead of a simulated environment. The researcher is examining actual phenomena instead of experimenting with different variables to see what outcomes (data) might result.

Can I use qualitative and quantitative approaches together in a study?

Yes, combining qualitative and quantitative research approaches happens all the time and is known as mixed methods research. For example, you could study individuals’ perceived risk in a certain scenario, such as how people rate the safety or riskiness of a given neighborhood. Simultaneously, you could analyze historical data objectively, indicating how safe or dangerous that area has been in the last year. To get the most out of mixed-method research, it’s important to understand the pros and cons of each methodology, so you can create a thoughtfully designed study that will yield compelling results.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

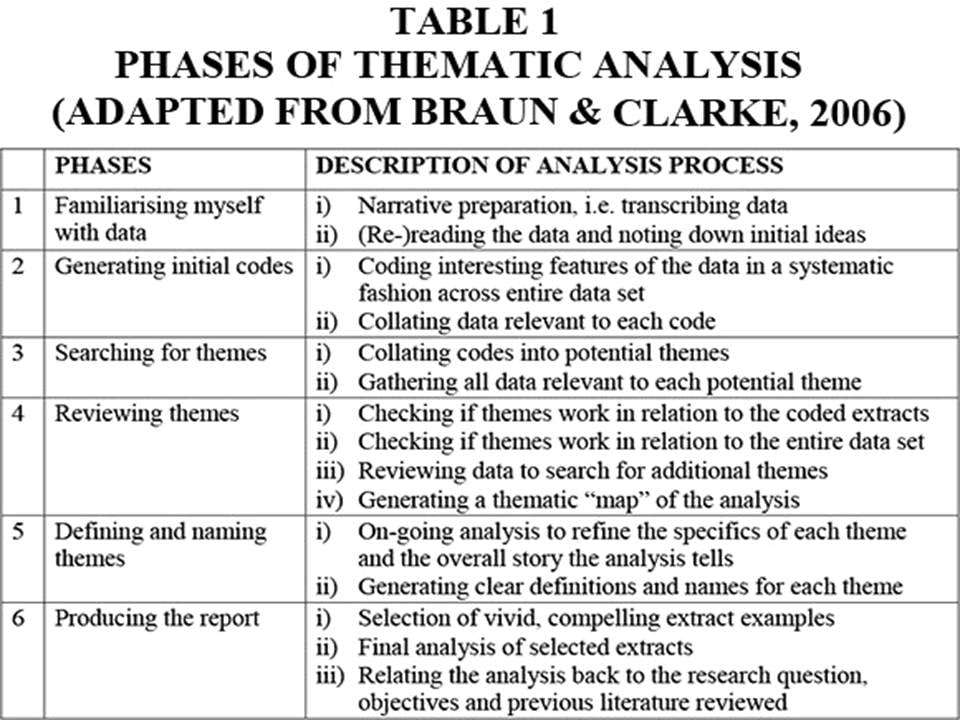

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis