Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved March 31, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Importance of Education — The Arguments Why Education Should Be Free For Everyone

The Arguments Why Education Should Be Free for Everyone

- Categories: College Tuition Importance of Education

About this sample

Words: 854 |

Published: Mar 18, 2021

Words: 854 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Works Cited:

- Alpha History. (n.d.). Nationalism as a cause of World War I.

- Bernhardi, F. von. (1914). Germany and the Next War. London: Edward Arnold.

- Cawley, J. (n.d.). Nationalism as the cause of European competitiveness that led to World War I.

- History Home. (n.d.). The causes of World War One. Retrieved from https://www.historyhome.co.uk/europe/causeww1.htm

- Rosenthal, L. (2016). The great war, nationalism and the decline of the West. Retrieved from https://lawrencerosenthal.net/2016/05/16/the-great-war-nationalism-and-the-decline-of-the-west/

- Bloy, M. (n.d.). Nationalism in the 19th century. Retrieved from https://www.historyhome.co.uk/europe/natquest.htm

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 700 words

2 pages / 1082 words

3 pages / 1370 words

2 pages / 795 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Importance of Education

Civic education is integral to the development of responsible and engaged citizens in modern society. It is the process through which individuals learn about their rights, responsibilities, and duties towards their communities [...]

High school is a critical phase in a student's academic journey, laying the foundation for future endeavors. Achieving success during this period requires a combination of effective strategies that can be applied to both [...]

Continuing education is a pathway to personal growth, professional advancement, and a more fulfilling life. In this essay, I will explore the reasons why I want to continue my education, analyzing how it can contribute to my [...]

Education is not the key to success—a statement that challenges conventional wisdom and invites a nuanced exploration of the factors that contribute to achievement and fulfillment in today's complex world. While education [...]

Education as a gateway to the future The value of education Importance of discussing education in life Contribution to societal development Utilization of technology in education Technology's impact on [...]

Under current circumstances, students are always overwhelmed by unity and test. From Preliminary English Test (PET) in elementary school to SAT and GRE in universities, our life is “polished” by all those standardized scores [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

114 Good Argumentative Essay Topics for Students in 2023

April 25, 2023

The skill of writing an excellent argumentative essay is a crucial one for every high school or college student to master. Argumentative essays teach students how to organize their thoughts logically and present them in a convincing way. This skill is helpful not only for those pursuing degrees in law , international relations , or public policy , but for any student who wishes to develop their critical thinking faculties. In this article, we’ll cover what makes a good argument essay and offer several argumentative essay topics for high school and college students. Let’s begin!

What is an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses research to present a reasoned argument on a particular subject . As with the persuasive essay , the purpose of this essay is to sway the reader to the writer’s position. A strong persuasive essay makes its point through diligent research, evidence, and logical reasoning skills.

Argumentative Essay Format

A strong argumentative essay will be based on facts, not feelings. Each of these facts should be supported by clear evidence from credible sources . Furthermore, a good argumentative essay will have an easy-to-follow structure. When organizing your argumentative essay, use this format as a guide: introduction, supporting body paragraphs, paragraphs addressing common counterarguments, and conclusion.

In the introduction , the writer presents their position and thesis statement —a sentence that summarizes the paper’s main points. The body paragraphs then draw upon supporting evidence to back up this initial statement, with each paragraph focusing on its own point. In the counterargument paragraph , the writer acknowledges and refutes opposing viewpoints. Finally, in the conclusion , the writer restates the main argument made in the thesis statement and summarizes the points of the essay. Additionally, the conclusion may offer a final proposal to persuade the reader of the essay’s position.

For more tips and tricks on formatting an argumentative essay, check out this useful guide from Khan Academy.

How to Write an Effective Argumentative Essay, Step by Step

- Choose your topic. Use the list below to help you pick a topic. Ideally, the topic you choose will be meaningful to you.

- Once you’ve selected your topic, it’s time to sit down and get to work! Use the library, the web, and any other resources to gather information about your argumentative essay topic. Research widely but smartly. As you go, take organized notes, marking the source of every quote and where it may fit in the scheme of your larger essay. Remember to look for possible counterarguments.

- Outline . Using the argumentative essay format above, create an outline for your essay. Brainstorm a thesis statement covering your argument’s main points, and begin to put together the pieces of the essay, focusing on logical flow.

- Write . Draw on your research and outline to create a solid first draft. Remember, your first draft doesn’t need to be perfect. (As Voltaire says, “Perfect is the enemy of good.”) For now, focus on getting the words down on paper.

- Edit . Be your own critical eye. Read what you’ve written back to yourself. Does it make sense? Where can you improve? What can you cut?

Argumentative Essay Topics for Middle School, High School, and College Students

Family argumentative essay topics.

- Should the government provide financial incentives for families to have children to address the declining birth rate?

- Should we require parents to provide their children with a certain level of nutrition and physical activity to prevent childhood obesity?

- Should parents implement limits on how much time their children spend playing video games?

- Should cellphones be banned from family/holiday gatherings?

- Should we hold parents legally responsible for their children’s actions?

- Should children have the right to sue their parents for neglect?

- Should parents have the right to choose their child’s religion?

- Are spanking and other forms of physical punishment an effective method of discipline?

- Should courts allow children to choose where they live in cases of divorce?

- Should parents have the right to monitor teens’ activity on social media?

- Should parents control their child’s medical treatment, even if it goes against the child’s wishes?

Education Argument Essay Topics

- Should schools ban the use of technology like ChatGPT?

- Are zoos unethical, or necessary for conservation and education?

- To what degree should we hold parents responsible in the event of a school shooting?

- Should schools offer students a set number of mental health days?

- Should school science curriculums offer a course on combating climate change?

- Should public libraries be allowed to ban certain books?

- What role, if any, should prayer play in public schools?

- Should schools push to abolish homework?

- Are gifted and talented programs in schools more harmful than beneficial due to their exclusionary nature?

- Should universities do away with Greek life?

- Should schools remove artwork, such as murals, that some perceive as offensive?

- Should the government grant parents the right to choose alternative education options for their children and use taxpayer funds to support these options?

- Is homeschooling better than traditional schooling for children’s academic and social development?

- Should we require schools to teach sex education to reduce teen pregnancy rates?

- Should we require schools to provide comprehensive sex education that includes information about both homosexual and heterosexual relationships?

- Should colleges use affirmative action and other race-conscious policies to address diversity on campus?

- Should the government fund public universities to make higher education more accessible to low-income students?

- Should the government fund universal preschool to improve children’s readiness for kindergarten?

Government Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should the U.S. decriminalize prostitution?

- Should the U.S. issue migration visas to all eligible applicants?

- Should the federal government cancel all student loan debt?

- Should we lower the minimum voting age? If so, to what?

- Should the federal government abolish all laws penalizing drug production and use?

- Should the U.S. use its military power to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan?

- Should the U.S. supply Ukraine with further military intelligence and supplies?

- Should the North and South of the U.S. split up into two regions?

- Should Americans hold up nationalism as a critical value?

- Should we permit Supreme Court justices to hold their positions indefinitely?

- Should Supreme Court justices be democratically elected?

- Is the Electoral College still a productive approach to electing the U.S. president?

- Should the U.S. implement a national firearm registry?

- Is it ethical for countries like China and Israel to mandate compulsory military service for all citizens?

- Should the U.S. government implement a ranked-choice voting system?

- Should institutions that benefited from slavery be required to provide reparations?

- Based on the 1619 project, should history classes change how they teach about the founding of the U.S.?

Bioethics Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should the U.S. government offer its own healthcare plan?

- In the case of highly infectious pandemics, should we focus on individual freedoms or public safety when implementing policies to control the spread?

- Should we legally require parents to vaccinate their children to protect public health?

- Is it ethical for parents to use genetic engineering to create “designer babies” with specific physical and intellectual traits?

- Should the government fund research on embryonic stem cells for medical treatments?

- Should the government legalize assisted suicide for terminally ill patients?

Social Media Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should the federal government increase its efforts to minimize the negative impact of social media?

- Do social media and smartphones strengthen one’s relationships?

- Should antitrust regulators take action to limit the size of big tech companies?

- Should social media platforms ban political advertisements?

- Should the federal government hold social media companies accountable for instances of hate speech discovered on their platforms?

- Do apps such as TikTok and Instagram ultimately worsen the mental well-being of teenagers?

- Should governments oversee how social media platforms manage their users’ data?

- Should social media platforms like Facebook enforce a minimum age requirement for users?

- Should social media companies be held responsible for cases of cyberbullying?

- Should the United States ban TikTok?

Religion Argument Essay Topics

- Should religious institutions be tax-exempt?

- Should religious symbols such as the hijab or crucifix be allowed in public spaces?

- Should religious freedoms be protected, even when they conflict with secular laws?

- Should the government regulate religious practices?

- Should we allow churches to engage in political activities?

- Religion: a force for good or evil in the world?

- Should the government provide funding for religious schools?

- Is it ethical for healthcare providers to deny abortions based on religious beliefs?

- Should religious organizations be allowed to discriminate in their hiring practices?

- Should we allow people to opt out of medical treatments based on their religious beliefs?

- Should the U.S. government hold religious organizations accountable for cases of sexual abuse within their community?

- Should religious beliefs be exempt from anti-discrimination laws?

- Should religious individuals be allowed to refuse services to others based on their beliefs or lifestyles? (As in this famous case .)

Science Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should the world eliminate nuclear weapons?

- Should scientists bring back extinct animals?

- Should we hold companies fiscally responsible for their carbon footprint?

- Should we ban pesticides in favor of organic farming methods?

- Is it ethical to clone animals for scientific purposes?

- Should the federal government ban all fossil fuels, despite the potential economic impact on specific industries and communities?

- What renewable energy source should the U.S. invest more money in?

- Should the FDA outlaw GMOs?

- Would the world be safe if we got rid of all nuclear weapons?

- Should we worry about artificial intelligence surpassing human intelligence?

Sports Argument Essay Topics

- Should colleges compensate student-athletes?

- How should sports teams and leagues address the gender pay gap?

- Should youth sports teams do away with scorekeeping?

- Should we ban aggressive contact sports like boxing and MMA?

- Should professional sports associations mandate that athletes stand during the national anthem?

- Should high schools require their student-athletes to maintain a certain GPA?

- Should transgender athletes compete in sports according to their gender identity?

- Should schools ban football due to the inherent danger it poses to players?

Technology Argumentative Essay Topics

- Should sites like DALL-E compensate the artists whose work it was trained on?

- Is social media harmful to children?

- Should the federal government make human exploration of space a more significant priority?

- Is it ethical for the government to use surveillance technology to monitor citizens?

- Should websites require proof of age from their users?

- Should we consider A.I.-generated images and text pieces of art?

- Does the use of facial recognition technology violate individuals’ privacy?

Business Argument Essay Topics

- Should the U.S. government phase out the use of paper money in favor of a fully digital currency system?

- Should the federal government abolish its patent and copyright laws?

- Should we replace the Federal Reserve with free-market institutions?

- Is free-market ideology responsible for the U.S. economy’s poor performance over the past decade?

- Will cryptocurrencies overtake natural resources like gold and silver?

- Is capitalism the best economic system? What system would be better?

- Should the U.S. government enact a universal basic income?

- Should we require companies to provide paid parental leave to their employees?

- Should the government raise the minimum wage?

- Should antitrust regulators break up large companies to promote competition?

- Is it ethical for companies to prioritize profits over social responsibility?

- Should gig-economy workers like Uber and Lyft drivers be considered employees or independent contractors?

- Should the federal government regulate the gig economy to ensure fair treatment of workers?

- Should the government require companies to disclose the environmental impact of their products?

In Conclusion – Argument Essay Topics

Using the tips above, you can effectively structure and pen a compelling argumentative essay that will wow your instructor and classmates. Remember to craft a thesis statement that offers readers a roadmap through your essay, draw on your sources wisely to back up any claims, and read through your paper several times before it’s due to catch any last-minute proofreading errors. With time, diligence, and patience, your essay will be the most outstanding assignment you’ve ever turned in…until the next one rolls around.

Looking for more fresh and engaging topics for use in the classroom? Also check out our 85 Good Debate Topics for High School Students .

- High School Success

Lauren Green

With a Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing from Columbia University and an MFA in Fiction from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin, Lauren has been a professional writer for over a decade. She is the author of the chapbook A Great Dark House (Poetry Society of America, 2023) and a forthcoming novel (Viking/Penguin).

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Sign Up Now

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Argumentative Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Modes of Discourse—Exposition, Description, Narration, Argumentation (EDNA)—are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these approaches and students’ need to understand and produce them.

What is an argumentative essay?

The argumentative essay is a genre of writing that requires the student to investigate a topic; collect, generate, and evaluate evidence; and establish a position on the topic in a concise manner.

Please note : Some confusion may occur between the argumentative essay and the expository essay. These two genres are similar, but the argumentative essay differs from the expository essay in the amount of pre-writing (invention) and research involved. The argumentative essay is commonly assigned as a capstone or final project in first year writing or advanced composition courses and involves lengthy, detailed research. Expository essays involve less research and are shorter in length. Expository essays are often used for in-class writing exercises or tests, such as the GED or GRE.

Argumentative essay assignments generally call for extensive research of literature or previously published material. Argumentative assignments may also require empirical research where the student collects data through interviews, surveys, observations, or experiments. Detailed research allows the student to learn about the topic and to understand different points of view regarding the topic so that she/he may choose a position and support it with the evidence collected during research. Regardless of the amount or type of research involved, argumentative essays must establish a clear thesis and follow sound reasoning.

The structure of the argumentative essay is held together by the following.

- A clear, concise, and defined thesis statement that occurs in the first paragraph of the essay.

In the first paragraph of an argument essay, students should set the context by reviewing the topic in a general way. Next the author should explain why the topic is important ( exigence ) or why readers should care about the issue. Lastly, students should present the thesis statement. It is essential that this thesis statement be appropriately narrowed to follow the guidelines set forth in the assignment. If the student does not master this portion of the essay, it will be quite difficult to compose an effective or persuasive essay.

- Clear and logical transitions between the introduction, body, and conclusion.

Transitions are the mortar that holds the foundation of the essay together. Without logical progression of thought, the reader is unable to follow the essay’s argument, and the structure will collapse. Transitions should wrap up the idea from the previous section and introduce the idea that is to follow in the next section.

- Body paragraphs that include evidential support.

Each paragraph should be limited to the discussion of one general idea. This will allow for clarity and direction throughout the essay. In addition, such conciseness creates an ease of readability for one’s audience. It is important to note that each paragraph in the body of the essay must have some logical connection to the thesis statement in the opening paragraph. Some paragraphs will directly support the thesis statement with evidence collected during research. It is also important to explain how and why the evidence supports the thesis ( warrant ).

However, argumentative essays should also consider and explain differing points of view regarding the topic. Depending on the length of the assignment, students should dedicate one or two paragraphs of an argumentative essay to discussing conflicting opinions on the topic. Rather than explaining how these differing opinions are wrong outright, students should note how opinions that do not align with their thesis might not be well informed or how they might be out of date.

- Evidential support (whether factual, logical, statistical, or anecdotal).

The argumentative essay requires well-researched, accurate, detailed, and current information to support the thesis statement and consider other points of view. Some factual, logical, statistical, or anecdotal evidence should support the thesis. However, students must consider multiple points of view when collecting evidence. As noted in the paragraph above, a successful and well-rounded argumentative essay will also discuss opinions not aligning with the thesis. It is unethical to exclude evidence that may not support the thesis. It is not the student’s job to point out how other positions are wrong outright, but rather to explain how other positions may not be well informed or up to date on the topic.

- A conclusion that does not simply restate the thesis, but readdresses it in light of the evidence provided.

It is at this point of the essay that students may begin to struggle. This is the portion of the essay that will leave the most immediate impression on the mind of the reader. Therefore, it must be effective and logical. Do not introduce any new information into the conclusion; rather, synthesize the information presented in the body of the essay. Restate why the topic is important, review the main points, and review your thesis. You may also want to include a short discussion of more research that should be completed in light of your work.

A complete argument

Perhaps it is helpful to think of an essay in terms of a conversation or debate with a classmate. If I were to discuss the cause of World War II and its current effect on those who lived through the tumultuous time, there would be a beginning, middle, and end to the conversation. In fact, if I were to end the argument in the middle of my second point, questions would arise concerning the current effects on those who lived through the conflict. Therefore, the argumentative essay must be complete, and logically so, leaving no doubt as to its intent or argument.

The five-paragraph essay

A common method for writing an argumentative essay is the five-paragraph approach. This is, however, by no means the only formula for writing such essays. If it sounds straightforward, that is because it is; in fact, the method consists of (a) an introductory paragraph (b) three evidentiary body paragraphs that may include discussion of opposing views and (c) a conclusion.

Longer argumentative essays

Complex issues and detailed research call for complex and detailed essays. Argumentative essays discussing a number of research sources or empirical research will most certainly be longer than five paragraphs. Authors may have to discuss the context surrounding the topic, sources of information and their credibility, as well as a number of different opinions on the issue before concluding the essay. Many of these factors will be determined by the assignment.

255 Education Argumentative Essay Topics & Ideas

18 January 2024

last updated

Education, a cornerstone of societal development, is a fertile field for writing papers. In this case, education argumentative essay topics can range widely, from debates over traditional vs. digital classrooms, the effectiveness of standardized testing, and the necessity of college education in the 21st century to the balance between academics and character development. Arguments can consider whether current school curriculums cater adequately to the needs of all students or primarily reinforce societal inequalities. Examining education policies at the local, national, or international levels can provide further insights. In turn, exploring the role of educational institutions in preparing students for the future workforce, including discussions on vocational training and entrepreneurial education, is another promising direction for developing argumentative essay topics in education.

Best Education Argumentative Essay Topics

- Balancing School Curriculum: Is Art Education as Important as Science?

- Roles of Technology in Enhancing Educational Outcomes

- The Ethics of Using Animals for School Biology Experiments

- Parental Influence on a Child’s Academic Success

- University Tuition Fees: Necessary Expense or Excessive Burden?

- Should Physical Education Be Mandatory in Schools?

- Importance of Teaching Life Skills alongside Traditional Subjects

- Grading System: Helping Students Learn or Adding Undue Pressure?

- Incorporating Meditation in Schools for Improved Mental Health

- Homeschooling vs. Traditional Schooling: Which Prepares Students Better?

- Examining the Role of Sex Education in Preventing Teenage Pregnancy

- Importance of Introducing Multicultural Education in Schools

- Mandatory Community Service as Part of the Curriculum: Pros and Cons

- Cyberbullying: Should Schools Take Responsibility?

- Unraveling the Effects of School Uniforms on Student Behavior

- Gender-Separated Classes: Beneficial or Discriminatory?

- Are College Degrees Worth the Financial Investment?

- The Role of Teachers’ Salaries in Ensuring Quality Education

- Digital Textbooks vs. Traditional Books: Which Is More Effective?

- Evaluating the Effectiveness of Homework in Enhancing Learning

- The Pros and Cons of Year-Round Schooling

- Roles of Parent-Teacher Communication in Enhancing Students’ Performance

- Effectiveness of Distance Learning: Is It Comparable to Traditional Learning?

- Should Controversial Topics Be Discussed in School?

Easy Education Essay Topics

- Exploring the Impact of School Lunch Programs on Student Health

- Is Cursive Writing Necessary in Today’s Digital Age?

- Teaching Consent in Schools: A Necessity or Overstepping Bounds?

- Gifted Programs: Are They Unfair to Other Students?

- Bilingual Education: Key to Global Competency or Detrimental to Native Culture?

- Implementing Zero Tolerance Policies in Schools: Beneficial or Harmful?

- Should Teachers Be Allowed to Carry Firearms for Classroom Protection?

- Influence of School Infrastructure on Student Learning Outcomes

- Incorporating Climate Change Education in School Curriculums

- Should Students Be Grouped by Ability in Classrooms?

- Effectiveness of Anti-Bullying Campaigns in Schools

- The Right to Privacy: Should Schools Monitor Student’s Online Activities?

- Evaluating the Role of Extracurricular Activities in Student Development

- The Need for Financial Literacy Education in Schools

- Freedom of Speech: Should Students Be Allowed to Express Controversial Opinions in School?

- Potential Benefits of Single-Sex Schools

- Relevance of History Education in Modern Times

- The Influence of Religious Beliefs on Education

- Foreign Language Requirements: Necessity or Unnecessary Burden?

- Are Teachers’ Unions Beneficial or Detrimental to Education Quality?

- Impacts of Parental Educational Background on Children’s Academic Achievement

- Does Grade Inflation Devalue a College Degree?

- Does Early Childhood Education Have Long-Term Benefits?

- Are College Admissions Processes Fair?

Interesting Education Essay Topics

- The Consequences of Educational Budget Cuts

- Exploring the Role of Sports in Academic Achievement

- Effects of Teacher Burnout on Student Learning

- Is Educational Equality Achievable in a Capitalist Society?

- Are Private Schools Necessarily Better than Public Schools?

- Role of Social Media in Education: Distraction or Useful Tool?

- Is Traditional Discipline Effective in Modern Schools?

- Examining the Effectiveness of Montessori Education

- Are Standardized Curriculum Frameworks Limiting Teachers’ Creativity?

- Is There a Place for Character Education in Today’s Schools?

- Importance of Critical Thinking Skills in the Curriculum

- Do Student Evaluations of Teachers Improve Teaching Quality?

- Music Education’s Influence on Academic Performance

- Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Academic Achievement

- Should Children Be Taught Entrepreneurship in Schools?

- Educational Benefits of Field Trips in Curriculum

- Does School Counseling Effectively Address Students’ Mental Health Needs?

- The Role of Games in Enhancing Math Education

- Is the Current Emphasis on STEM Education Justified?

- The Influence of Family Structure on Children’s Educational Outcomes

- Does Multitasking with Technology Hinder Learning?

- Should Political Education Be Mandatory in Schools?

- Effects of Classroom Diversity on Student Learning and Empathy

Education Essay Topics for High School

- Does Standardized Testing Accurately Reflect a Student’s Knowledge?

- Should Schools Invest More in Arts Education?

- Is a Year-Round School Calendar Beneficial for Learning?

- Are School Uniforms Necessary for a Conducive Learning Environment?

- Does Homework Actually Benefit Students?

- Should Advanced Courses Be Made Available to All High School Students?

- Can Online Learning Replace Traditional Classroom Teaching?

- How Is Essential Sex Education in High School Curriculum?

- The Impact of School Infrastructure on Quality of Education

- Are School Sports Essential for Student Development?

- Does Bilingual Education Enhance Cognitive Skills?

- Does Parental Involvement Improve Academic Performance?

- Is There a Need to Reinvent School Discipline Policies?

- How Does the Use of Technology in Schools Affect Learning?

- The Role of Schools in Promoting Healthy Eating Habits

- Are School Field Trips Essential for Practical Learning?

- Should Schools Introduce Personal Finance Classes?

- Physical Education Classes: Necessity or Luxury?

- Effect of Bullying on Academic Performance

- The Influence of Peer Pressure on Students’ Performance

- Should We Teach Entrepreneurship in High Schools?

- Does a Longer School Day Improve Learning Outcomes?

- Roles of Moral Education in Character Building

Education Essay Topics for College Students

- Incorporating Technology in Classrooms: Necessity or Distraction?

- Standardized Testing: An Effective Evaluation Tool or a Hindrance to Creativity?

- University Degrees: Essential for Success or Overrated?

- Pros and Cons of Single-Sex Education: A Deep Dive

- Private vs. Public Schools: Who Provides a Better Education?

- Traditional Education vs. Online Learning: Comparing Effectiveness

- Impact of Extracurricular Activities on Academic Performance

- Bilingual Education: Potential Benefits and Challenges

- Vocational Training: Does It Deserve More Emphasis in the Curriculum?

- Effects of Class Size on Student Learning Outcomes

- Homeschooling vs. Traditional Schooling: Weighing the Outcomes

- Mandatory Physical Education: A Boon or Bane?

- College Athletes: Should They Be Paid?

- Education in Rural vs. Urban Settings: Exploring Disparities

- Funding: How Does It Impact the Quality of Education?

- Role of Sex Education in Schools: Analyzing the Importance

- Uniforms in Schools: Do They Promote Equality?

- Plagiarism Policies: Are They Too Strict or Not Enough?

- Art Education: Is It Being Neglected in Schools?

- Teaching Soft Skills: Should It Be Mandatory in Schools?

- Tuition Fees: Do They Restrict Access to Higher Education?

- Inclusion of Students With Disabilities: Analyzing Best Practices

Education Argumentative Essay Topics for University

- Cyberbullying: Should Schools Have a Greater Responsibility?

- STEM vs. Liberal Arts: Which Provides a Better Future?

- Impacts of Mental Health Services in Schools

- Grade Inflation: Does It Devalue a Degree?

- Diversity in Schools: Does It Enhance Learning?

- Gap Year: Does It Help or Hinder Students?

- Recess: Is It Necessary for Students’ Well-Being?

- Early Childhood Education: Does It Contribute to Later Success?

- Parental Involvement: How Does It Influence Student Performance?

- Value of Internships in Higher Education

- Curriculum: Is It Outdated in Today’s Fast-Paced World?

- Digital Textbooks vs. Paper Textbooks: Evaluating the Differences

- Learning a Second Language: Should It Be Mandatory?

- Censorship in School Libraries: Freedom or Protection?

- Life Skills Education: Is It Missing From Our Curriculum?

- Teachers’ Pay: Does It Reflect Their Value in Society?

- College Rankings: Do They Truly Reflect Educational Quality?

- Corporal Punishment: Does It Have a Place in Modern Education?

- Student Loans: Are They Creating a Debt Crisis?

- Learning Styles: Myth or Real Educational Framework?

- Grading System: Is It the Best Measure of Students’ Abilities?

Academic Topics Essay

- Fostering Creativity: Should Schools Prioritize the Arts?

- Student Debt: Consequences and Possible Solutions

- Bullying Policies in Schools: Are They Effective?

- Teaching Ethics and Values: Whose Responsibility?

- Distance Learning: The New Normal Post-Pandemic?

- School Censorship: Are There Limits to Freedom of Speech?

- College Admissions: Is the Process Fair?

- Standardizing Multilingual Education: A Possibility?

- Learning Disabilities: How Can Schools Provide Better Support?

- Does Class Size Impact the Quality of Education?

- Integrating Technology: Are There Potential Risks?

- Affirmative Action in College Admissions: Fair or Biased?

- The Role of Private Tuition: Supplemental Help or Unfair Advantage?

- Military-Style Discipline in Schools: Effective or Harmful?

- Should Schools Implement Mental Health Curriculums?

- Early Education: Does It Pave the Way for Success?

- Grading System: Is it an Accurate Measure of Student Ability?

- Career Counseling in Schools: Should It be Mandatory?

- Addressing Racial Bias in Educational Materials

- The Debate Over Prayer in Schools: Freedom of Religion or Church-State Separation?

- The Impact of Zero-Tolerance Policies on the School Environment

- Education Funding: The Pros and Cons of School Vouchers

- University Rankings: Helpful Guide or Harmful Pressure?

- Personal Finance Education: Should It Be Included in the Curriculum?

Argumentative Essay Topics on Education

- Impacts of Standardized Testing on Students’ Creativity

- Digital Learning Platforms vs. Traditional Classroom Teaching

- Effectiveness of the Montessori Education System

- Mandatory Foreign Language Education: A Necessity or Luxury?

- Single-Sex Schools’ Role in Modern Society

- Teachers’ Salaries: A Reflection of Their Value in Society?

- Technological Devices in Classrooms: A Boon or Bane?

- Inclusion of Life Skills in the Curriculum

- Ethical Education: Its Significance and Implementation

- Educating Children About Climate Change and Sustainability

- Homeschooling vs. Traditional Schooling: Which Yields Better Results?

- School Uniforms: Do They Encourage Uniformity Over Individuality?

- The Role of Extracurricular Activities in Holistic Education

- Importance of Critical Thinking in the Curriculum

- Corporate Sponsorship in Schools: Ethical Considerations

- Increasing Parental Involvement in Children’s Education

- Vocational Training in High School: Is It Necessary?

- The Merits and Demerits of Charter Schools

- Prioritizing Health Education in the School Curriculum

- Diversifying History Lessons: The Impact on Cultural Understanding

- Gifted and Talented Programs: Unfair Advantage or Necessary Support?

- Implementing Mindfulness Training in Schools

- Mandatory Physical Education: Is It Vital for Health?

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Year-Round Schooling

- The Potential of Virtual Reality in Education

Education Persuasive Essay Topics

- Enhancing Creativity: The Importance of Art Education in Schools

- Mandatory Coding Lessons: Preparing Students for the Digital Future

- Bilingual Education: Encouraging Multilingualism From an Early Age

- Parental Involvement: Crucial for Academic Success or an Invasion of Privacy?

- Cyberbullying Awareness: Should It Be Part of the School Curriculum?

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education: Boon or Bane?

- Sex Education: Essential for Reducing Teen Pregnancy and STD Rates

- Standardized Tests: Accurate Measure of a Student’s Capabilities or Outdated Practice?

- Religious Studies: The Necessity of Teaching World Religions in Public Schools

- Homework Overload: Assessing the True Impact on Students’ Mental Health

- School Uniforms: Encouraging Discipline or Suppressing Individuality?

- Inclusion in Classrooms: The Benefits of Educating Special Needs Students Alongside Their Peers

- Teacher Salaries: The Need for Higher Pay to Attract Quality Educators

- Educational Video Games: Revolutionizing Learning or Distraction From Studying?

- Student Athletes: Balancing Academics and Sports Participation

- Year-Round Schooling: Improving Learning Retention or Overloading Students?

- Early Education: The Benefits of Pre-School Programs

- Social Media: Its Role in Modern Education

- Field Trips: Enhancing Learning Outside the Classroom

- Classroom Size: The Impact on Learning and Engagement

- Vocational Training: Essential for Preparing Students for the Workforce

- Distance Learning: Exploring its Advantages and Disadvantages

Education Research Paper Topics

- Extracurricular Activities: The Importance in Students’ Holistic Development

- Multiple Intelligence Theory: Implementing Diverse Teaching Strategies

- Classroom Decor: Its Influence on Student Engagement and Learning

- Mindfulness Practices: Promoting Emotional Health in Schools

- Sustainability Education: Fostering Environmentally-Conscious Citizens

- Cultural Diversity: Promoting Inclusion and Acceptance in Schools

- Physical Education: Addressing Childhood Obesity through School Programs

- Gifted and Talented Programs: Benefits and Drawbacks

- Homeschooling: Advantages Over Traditional Schooling

- Alternative Assessment Methods: Moving Beyond Exams and Grades

- Bullying Prevention: The Role of Schools and Teachers

- College Admissions: The Controversy Around Legacy Preferences

- Ethics Education: Instilling Moral Values in Students

- Student Loans: The Crisis and Its Impact on Higher Education

- Nutrition Education: Promoting Healthy Eating Habits in Schools

- Digital Literacy: Essential Skills for the 21st Century

- Grade Inflation: The Deterioration of Academic Standards in Higher Education

- Climate Change Education: Teaching the Next Generation About Global Warming

- Character Education: Building Integrity and Responsibility in Students

- Music Education: Its Influence on Cognitive Development

- Literacy Programs: Overcoming Reading and Writing Challenges

- Mentorship Programs: Enhancing Student Success and Confidence

- Financial Literacy: Preparing Students for Real-World Money Management

Strong Education Argumentative Essay Topics

- Is Censorship Justified in School Libraries?

- The Benefits and Drawbacks of Single-Sex Schools

- Is College Preparation in High School Adequate?

- Are Teachers’ Salaries Commensurate With Their Job Responsibilities?

- Cyberbullying: Should Schools Intervene?

- The Importance of Cultural Diversity in Education

- Should Mental Health Education Be Mandatory in Schools?

- Do School Rankings Reflect the Quality of Education?

- The Relevance of Cursive Writing in Today’s Digital World

- Should Religious Studies Be Part of the School Curriculum?

- Are Students Overburdened with Excessive Schoolwork?

- The Implications of Zero Tolerance Policies in Schools

- School Safety: Responsibility of Schools or Parents?

- Does Grade Inflation Diminish the Value of Education?

- Are Life Skills Education Necessary in Schools?

- The Debate on Home Schooling vs. Traditional Schooling

- Is it Necessary to Teach World Religions in High Schools?

- Does a School’s Location Affect the Quality of Education?

- The Argument for Teaching Emotional Intelligence in Schools

- Should Attendance Be Mandatory in High School?

- Could Meditation and Mindfulness Improve Students’ Concentration?

- The Role of Music Education in Student Development

- Do Students Learn More From Books or Computers?

- The Need for Environmental Sustainability Education in Schools

To Learn More, Read Relevant Articles

787 sports argumentative essay topics & persuasive speech ideas, 551 technology argumentative essay topics & ideas.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Argumentative Essay Example

Higher Education Argumentative Essays Samples For Students

42 samples of this type

Do you feel the need to examine some previously written Argumentative Essays on Higher Education before you begin writing an own piece? In this open-access collection of Higher Education Argumentative Essay examples, you are provided with a fascinating opportunity to explore meaningful topics, content structuring techniques, text flow, formatting styles, and other academically acclaimed writing practices. Adopting them while composing your own Higher Education Argumentative Essay will surely allow you to finalize the piece faster.

Presenting high-quality samples isn't the only way our free essays service can aid students in their writing ventures – our authors can also compose from point zero a fully customized Argumentative Essay on Higher Education that would make a solid foundation for your own academic work.

Free Argumentative Essay On Vocational And Liberal Aims In Higher Education

Good value of higher education in a changing economy argumentative essay example, good should america adopt an educational system more like europe argumentative essay example.

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your argumentative essay done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

The Value Of College Education Argumentative Essays Examples

Argumentative essay on is college worth it, introduction, example of argumentative essay on subsidized higher education, higher education and income does it pay off argumentative essay examples, higher education losing its way/civic responsibility argumentative essay sample, example of just say yes to college argumentative essay, education student retention and dropout rates in higher education argumentative essay example, argumentative essay on impact of globalisation and internationalisation on educational contexts, argumentative essay on education system in saudi arabia, argumentative essay on classdate, the factors that drive college tuition fees, should college education be free to all argumentative essay to use for practical writing help, example of domestic abuse argumentative essay, free argumentative essay on classic english literature, how important is college or university education argumentative essays example.

In relation to good education, there is always a need to measure situations especially when it comes determining the practicality of its application. It is because of this matter that the real value of college education at present is being examined accordingly. In the discussion that follows, the determination of such value shall be given proper attention to, this making a definite impact on how the society accepts the value of tertiary education at present.

Rising Cost Of College Tuition In US Argumentative Essay Sample

Every segment of the American economy is under pressure and college education has not been left behind. The cost of college education has risen sharply in the recent past and a big percentage of American College students risk being left out of college education if the cost rises further. The increase in costs has come forth in spite of the excruciating cost-cutting done by colleges on every activity in the institutions. The increase in tuition fee actually outperformed the overall inflation rate.

Argumentative Essay On Chinese Parents Should Send Their Children Abroad

- Introduction

Background Information

Study skills managing time as an adult learner argumentative essay example, free everyone should be required to undertake a university education argumentative essay example, thesis statement: everyone should be required to undertake a university education to promote sustainable economic development and growth., sample argumentative essay on description and feasibility of solution to in the inheritors, good example of should division 1 college athletes be paid argumentative essay, free argumentative essay on is the college tuition cost too high, value-neutral history/background of the college curriculum and the rise in the tuition cost, example of plagiarism argumentative essay, example of argumentative essay on two years are better than four, accessibility of higher education in gulf states argumentative essay example, the problem of cultural literacy in adult learning argumentative essays examples, free these entry barriers uncover, in fact, deeper socioeconomic inequalities not only rampant among black students but also historical. argumentative essay sample, responsibility to carry firearms: example argumentative essay by an expert writer to follow, stasis argument argumentative essays example, argument explanation, good example of stasis argument argumentative essay, contemporary education argumentative essay sample, the cost of college argumentative essay samples, online courses argumentative essay samples, the positive effects of social media on students outweigh the negative argumentative essay sample, example of standardized testing: detrimental to todays american students argumentative essay, how technological dependence enhances students academic performance argumentative essay examples, example of why do women earn less on average than men do argumentative essay, what is the purpose of college education argumentative essay, language policy gaelic uk argumentative essay examples, argumentative essay on the negative impacts of higher education cost.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the challenge of position-taking in novice higher education students’ argumentative writing.

- Centre for University Teaching and Learning, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

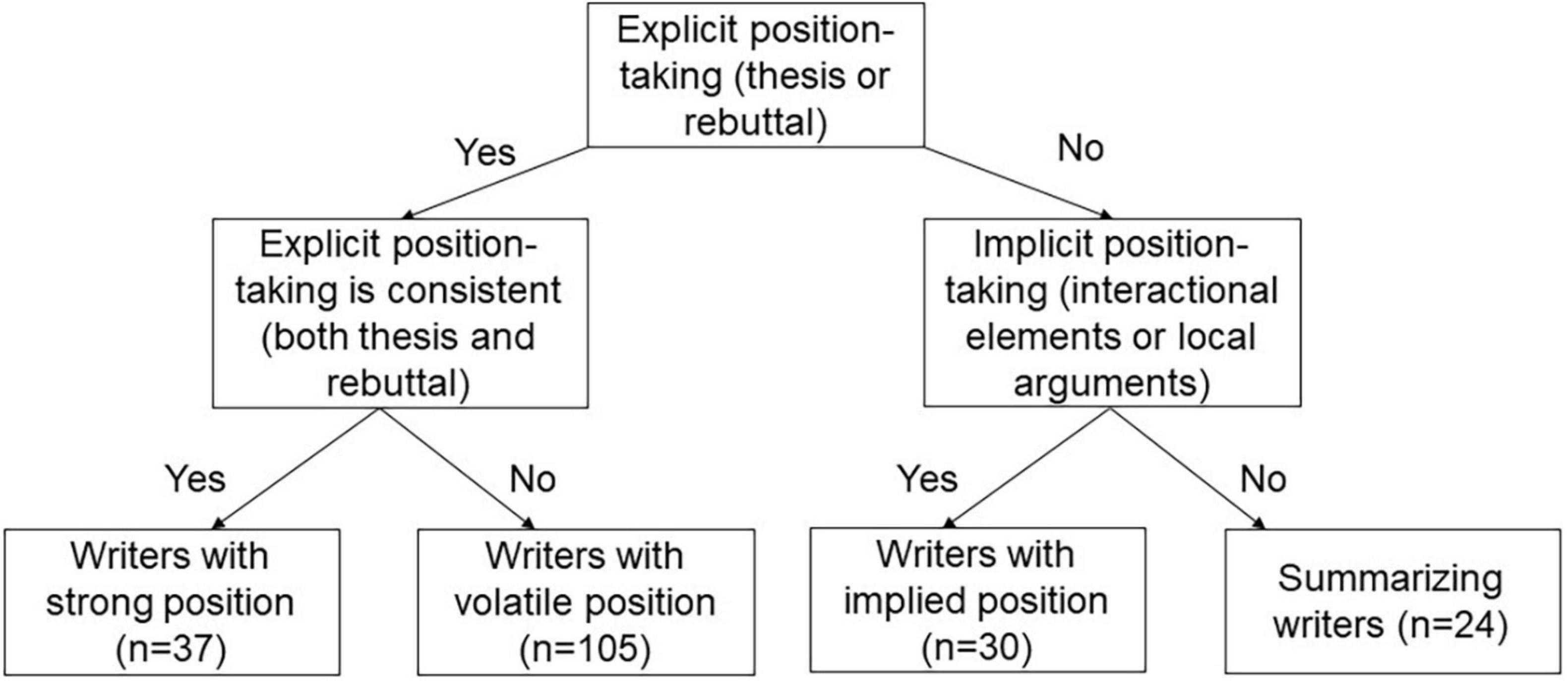

Argumentative writing is the central generic skill in higher education studies. However, students have difficulties in basic argumentation skills. Novice students do not necessarily receive adequate guidance, and their prior education may not have supported the requirements of higher education writing. Position-taking is at the core of argumentation, but students are often hesitant to make their point. Furthermore, they may have an incorrect and one-sided perception about an argument, leading them to avoid alternative positions in their argumentative writing. The study aims to explore starting level skills of novice students’ argumentative writing, namely their position-taking. The participants were 196 first-year students from diverse fields of study in two Finnish higher education institutions. They were required to solve a problem and write an argumentative essay based on five documents that were given to them. The essays were analyzed using qualitative content analysis applying abductive approach. Substantial variation was detected in students’ position-taking. We identified four groups of writers based on their position-taking. First two groups were more or less explicit in their position-taking. Most of the students (72%) belonged to these two groups. However, a minority of them were consistent in their position-taking. Writers in the third group (15%) implied their position, and writers in the fourth group (12%) stuck to summarizing sources without position-taking. The findings invite teachers to support novice students in their basic argumentation. Co-operation between faculty teachers and writing teachers is encouraged.

Introduction

Generic skills have been considered vital for success in higher education studies ( Barrie, 2006 ; Shavelson, 2010 ; Hyytinen et al., 2019 ). They are universal expert skills, such as communication, problem solving and argumentation, and they are equally important in all fields, enabling learning discipline-specific skills and knowledge ( Hyytinen et al., 2021a ). The central generic skill is argumentation ( Andrews, 2009 ; Mäntynen, 2009 ; Wolfe, 2011 ; Wingate, 2012 ). Argumentation, and more specifically argumentative writing, is required of the students from the moment they apply and enter a higher education institution, until graduation, in the form of essays, examinations, and dissertations (see Wolfe, 2011 ; Wingate, 2012 ). Even more important, it is not just a technical skill, to pull through assignments, but argumentation also facilitates learning ( Asterhan and Schwarz, 2016 ; Iordanou et al., 2019 ; Kuhn, 2019 ). Research on generic skills often focuses on clusters of skills, their importance, and students’ experiences of them (e.g., Barrie, 2006 ; Tuononen et al., 2019 ; Virtanen and Tynjälä, 2019 ). However, such an approach offers few practical insights for higher education teachers who often struggle between teaching discipline-specific knowledge and supporting students in their generic skills. Instead, gaining a more detailed understanding of students’ strengths and weaknesses in each generic skill, such as argumentation, will help in developing tools for teachers.

Several studies show that even advanced higher education students have gaps in their basic argumentation skills, such as combining claims and evidence, or presenting diverse viewpoints ( Marttunen, 1994 ; Ivanič, 1998 ; Andrews et al., 2006 ; Laakso et al., 2016 ; Hyytinen et al., 2017 , 2021b ; Breivik, 2020 ). Students may be unsure about what an argument is ( Andrews, 2009 ; Wingate, 2012 ; Breivik, 2020 ). They may also have difficulties in identifying rhetoric situations and their expectations and adapting their writing for the requirements of each assignment ( Zimmerman and Risemberg, 1997 ; Johns, 2008 ; Roderick, 2019 ). It has been suggested that prior education does not provide sufficient argumentative skills, but students in higher education still feel that they do not receive adequate guidance or instructions on elements of argumentative writing ( Andrews, 2009 ). Teachers often assume that students either already master these skills or learn as they go. Surprisingly, even though argumentative writing has been thought to be the Achilles’ heel in the transition to higher education, little research has focused on actual novice students’ starting level skills. We know a lot more about advanced students’ or even senior scholars’ argumentative skills. The present study focuses on novice students’ basic skills in argumentative writing, namely describing the variation in the ways of their position-taking, which is viewed as the core of argumentation ( Andrews et al., 2006 ; Wingate, 2012 ).

Argumentation and Argumentative Writing in Higher Education

The objective of an argument is to support one’s claims and conclusions with reasons or evidence ( Toulmin, 2003 ; Halpern, 2014 ). In academic contexts, the claims and conclusions are backed with prior research and/or empirical data ( Swales, 1990 ; Wolfe, 2011 ). In argumentative guidebooks, an argument is often presented as a simple one or two sentence structure, but in practice it is often integrated in broader entities such as written essays or articles, or spoken addresses or debates (see Andrews, 2009 ). Most assignments that a higher education student—across disciplines—encounters during their studies require argumentative writing ( Wolfe, 2011 ). Assignments that require argumentation have also been considered a valuable tool for learning. Such assignments have been found to be a particularly advantageous method when learning about complex topics with diverse viewpoints and complex skills such as critical thinking ( Asterhan and Schwarz, 2016 ; Iordanou et al., 2019 ; Kuhn, 2019 ).

There is no template for constructing an argumentative text, but the writer must identify the requirements of the situation, and the best ways to fulfill those requirements (see Johns, 2008 ). A major decision in argumentative writing is related to choosing the placing of claims or conclusions and evidence. These rhetorical strategies are culture-specific to some degree; in other words, one strategy may be favored over another, across genres and communities. For instance, Finnish writers have been found to prefer to present all evidence and elements of uncertainty before their conclusion (final focus), in contrast to Anglo-American writers who prefer to present their inference first and then proceed to evidence (initial focus) ( Mauranen, 1993 ; Mikkonen, 2010 ; see also Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969 ).

In addition to variation across cultures, argumentative skills have also been suggested to be, at least in part, discipline-specific ( Andrews, 2009 , 2015 ). Accordingly, there are disciplinary differences in the epistemologies that influence how to evaluate an argument (e.g., Hetmanek et al., 2018 ). However, beyond the varying conventions of cultures and disciplines, arguments and argumentative texts have more generic features. This includes development and presentation of one’s position ( Andrews, 2009 ; Wingate, 2012 ), and micro- and macrostructures of argumentation, such as claim or conclusion and evidence, and introduction, counterarguments, and discussion ( Kuhn, 1991 ; Toulmin, 2003 ; Breivik, 2020 ). To learn the discipline-specific conventions of argumentation, it is necessary to master the generic features. Consequently, the ability to use generic features of argumentation is eminently important for novice students who are new to higher education. They are not yet integrated in their study program or academic writing community ( Swales, 1990 ; Donald, 2002 ). However, despite the lack of relevant skills, novice students receive little guidance in argumentative writing. In the absence of proper guidance to academic requirements, they are tapping into the skills they have learnt in their prior education ( Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987 ; Andrews et al., 2006 ). In Finland, it has been suggested that argumentation is not sufficiently emphasized in the upper secondary school, and its final exams, the Matriculation Examination ( Mäntynen, 2009 ; Komppa, 2012 ). However, evidence-based information about Finnish novice higher education students’ argumentative writing is scarce. While we know that they have some problems in consistency of their arguments ( Hyytinen et al., 2017 ), there is no research on more generic features in argumentative writing.

Position-Taking in Argumentative Writing

Taking a position is at the core of argumentation ( Andrews, 2009 ; Wingate, 2012 ). Typically, the position is seen as the viewpoint the writer intends to support, or the main point the writer intends to make. The position conveys the writer’s explicit presence in the text ( Mauranen, 1993 ; Hyland, 2005 ). Additionally, to strengthen the argument, the position can be challenged with alternative positions (see Andrews, 2009 ). Failing to take a position can lead to problems in higher education studies where argumentation skills are vital (e.g., Wolfe, 2011 ). Such problems often go hand in hand with problems in deep learning and meaning construction ( Biggs, 1988 ; see also Petrić, 2007 ).

In argumentative writing, the position is often expressed as a thesis, a holistic main claim that summarizes the writer’s point of view ( Kakkuri-Knuuttila and Halonen, 1998 ; Mikkonen, 2010 ; Wolfe, 2011 ). However, the position is not always expressed as explicitly as a thesis. Indeed, it has been found that higher education students have challenges in emphasizing their position, and instead, they may lean toward research sources, as well as summarizing, and attributing ( Lea and Street, 1998 ; Petrić, 2007 ; Mäntynen, 2009 ; McCulloch, 2012 ; Laakso et al., 2016 ; Lee et al., 2018 ). Consequently, they do not take a position, but they rather display their knowledge on the topic (see Petrić, 2007 ). Higher education students can feel inadequate for making a strong point ( Ivanič, 1998 ; Andrews, 2009 ; Mendoza et al., 2022 ). They may avoid making a holistic statement like a thesis by making so called local arguments. These are claims that encompass a short proportion of the text, and do not summarize the point of view of the entire text ( Mauranen, 1993 ; Wolfe, 2011 ). However, writers may also imply their position in more subtle ways than stating an explicit thesis or even making local arguments. Linguists talk about interactional features, referring to elements that convey writer’s relation with their text ( Hyland and Tse, 2004 ; Hyland, 2005 ). Writers might withhold (hedge) or emphasize (boost) their commitment, express their affective attitudes (attitude marker), or use first-person forms to remind reader of their presence in the text (self-mention) ( Hyland, 2005 ).

Discussion of diverse viewpoints, i.e., alternative positions, is an important yet challenging part of argumentation ( Kuhn, 1991 ; Andrews, 2009 ; Wingate, 2012 ; Kuhn et al., 2016b ). In its strongest form, a rebuttal, an explicit position is taken against some evidence. Just as they may be hesitant in their position-taking, as discussed above, even advanced higher education students may have challenges in introducing alternative positions in their argumentation ( Laakso et al., 2016 ; Hyytinen et al., 2021b ; Kuhn and Modrek, 2021 ). Even acknowledgment of alternative positions is difficult for many, not to mention rebutting them ( Kuhn, 1991 ). This tendency has been called my-side bias, indicating an inability to see other alternatives ( Perkins, 1989 ). However, these challenges may not be about an inclination to emphasize one’s own opinion but instead they reflect the writer’s incorrect perception of an argument ( Wolfe and Britt, 2008 ; Wingate, 2012 ). Writers may see a good argument as a one-sided construction, and so they bring out all the supporting evidence, and leave out any contesting facts. The ability to develop rebuttals requires a basic understanding of position-taking, and usually, the presence of rebuttals is an indication of a higher overall quality of argumentation ( Wolfe et al., 2009 ; Kuhn et al., 2016a ).