- Open access

- Published: 08 October 2021

Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application

- Micah D. J. Peters 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Casey Marnie 1 ,

- Heather Colquhoun 4 , 5 ,

- Chantelle M. Garritty 6 ,

- Susanne Hempel 7 ,

- Tanya Horsley 8 ,

- Etienne V. Langlois 9 ,

- Erin Lillie 10 ,

- Kelly K. O’Brien 5 , 11 , 12 ,

- Ӧzge Tunçalp 13 ,

- Michael G. Wilson 14 , 15 , 16 ,

- Wasifa Zarin 17 &

- Andrea C. Tricco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4114-8971 17 , 18 , 19

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 263 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

160 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis with a growing suite of methodological guidance and resources to assist review authors with their planning, conduct and reporting. The latest guidance for scoping reviews includes the JBI methodology and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews. This paper provides readers with a brief update regarding ongoing work to enhance and improve the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews as well as information regarding the future steps in scoping review methods development. The purpose of this paper is to provide readers with a concise source of information regarding the difference between scoping reviews and other review types, the reasons for undertaking scoping reviews, and an update on methodological guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews.

Despite available guidance, some publications use the term ‘scoping review’ without clear consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardised use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the review’s objective(s) and question(s) are critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews.

Rigourous, high-quality scoping reviews should clearly follow up to date methodological guidance and reporting criteria. Stakeholder engagement is one area where further work could occur to enhance integration of consultation with the results of evidence syntheses and to support effective knowledge translation. Scoping review methodology is evolving as a policy and decision-making tool. Ensuring the integrity of scoping reviews by adherence to up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well-informed decision-making.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Given the readily increasing access to evidence and data, methods of identifying, charting and reporting on information must be driven by new, user-friendly approaches. Since 2005, when the first framework for scoping reviews was published, several more detailed approaches (both methodological guidance and a reporting guideline) have been developed. Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis which is very popular amongst end users [ 1 ]. Indeed, one scoping review of scoping reviews found that 53% (262/494) of scoping reviews had government authorities and policymakers as their target end-user audience [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews can provide end users with important insights into the characteristics of a body of evidence, the ways, concepts or terms have been used, and how a topic has been reported upon. Scoping reviews can provide overviews of either broad or specific research and policy fields, underpin research and policy agendas, highlight knowledge gaps and identify areas for subsequent evidence syntheses [ 3 ].

Despite or even potentially because of the range of different approaches to conducting and reporting scoping reviews that have emerged since Arksey and O’Malley’s first framework in 2005, it appears that lack of consistency in use of terminology, conduct and reporting persist [ 2 , 4 ]. There are many examples where manuscripts are titled ‘a scoping review’ without citing or appearing to follow any particular approach [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This is similar to how many reviews appear to misleadingly include ‘systematic’ in the title or purport to have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement without doing so. Despite the publication of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and other recent guidance [ 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], many scoping reviews continue to be conducted and published without apparent (i.e. cited) consideration of these tools or only cursory reference to Arksey and O’Malley’s original framework. We can only speculate at this stage why many authors appear to be either unaware of or unwilling to adopt more recent methodological guidance and reporting items in their work. It could be that some authors are more familiar and comfortable with the older, less prescriptive framework and see no reason to change. It could be that more recent methodologies such as JBI’s guidance and the PRISMA-ScR appear more complicated and onerous to comply with and so may possibly be unfit for purpose from the perspective of some authors. In their 2005 publication, Arksey and O’Malley themselves called for scoping review (then scoping study) methodology to continue to be advanced and built upon by subsequent authors, so it is interesting to note a persistent resistance or lack of awareness from some authors. Whatever the reason or reasons, we contend that transparency and reproducibility are key markers of high-quality reporting of scoping reviews and that reporting a review’s conduct and results clearly and consistently in line with a recognised methodology or checklist is more likely than not to enhance rigour and utility. Scoping reviews should not be used as a synonym for an exploratory search or general review of the literature. Instead, it is critical that potential authors recognise the purpose and methodology of scoping reviews. In this editorial, we discuss the definition of scoping reviews, introduce contemporary methodological guidance and address the circumstances where scoping reviews may be conducted. Finally, we briefly consider where ongoing advances in the methodology are occurring.

What is a scoping review and how is it different from other evidence syntheses?

A scoping review is a type of evidence synthesis that has the objective of identifying and mapping relevant evidence that meets pre-determined inclusion criteria regarding the topic, field, context, concept or issue under review. The review question guiding a scoping review is typically broader than that of a traditional systematic review. Scoping reviews may include multiple types of evidence (i.e. different research methodologies, primary research, reviews, non-empirical evidence). Because scoping reviews seek to develop a comprehensive overview of the evidence rather than a quantitative or qualitative synthesis of data, it is not usually necessary to undertake methodological appraisal/risk of bias assessment of the sources included in a scoping review. Scoping reviews systematically identify and chart relevant literature that meet predetermined inclusion criteria available on a given topic to address specified objective(s) and review question(s) in relation to key concepts, theories, data and evidence gaps. Scoping reviews are unlike ‘evidence maps’ which can be defined as the figural or graphical presentation of the results of a broad and systematic search to identify gaps in knowledge and/or future research needs often using a searchable database [ 15 ]. Evidence maps can be underpinned by a scoping review or be used to present the results of a scoping review. Scoping reviews are similar to but distinct from other well-known forms of evidence synthesis of which there are many [ 16 ]. Whilst this paper’s purpose is not to go into depth regarding the similarities and differences between scoping reviews and the diverse range of other evidence synthesis approaches, Munn and colleagues recently discussed the key differences between scoping reviews and other common review types [ 3 ]. Like integrative reviews and narrative literature reviews, scoping reviews can include both research (i.e. empirical) and non-research evidence (grey literature) such as policy documents and online media [ 17 , 18 ]. Scoping reviews also address broader questions beyond the effectiveness of a given intervention typical of ‘traditional’ (i.e. Cochrane) systematic reviews or peoples’ experience of a particular phenomenon of interest (i.e. JBI systematic review of qualitative evidence). Scoping reviews typically identify, present and describe relevant characteristics of included sources of evidence rather than seeking to combine statistical or qualitative data from different sources to develop synthesised results.

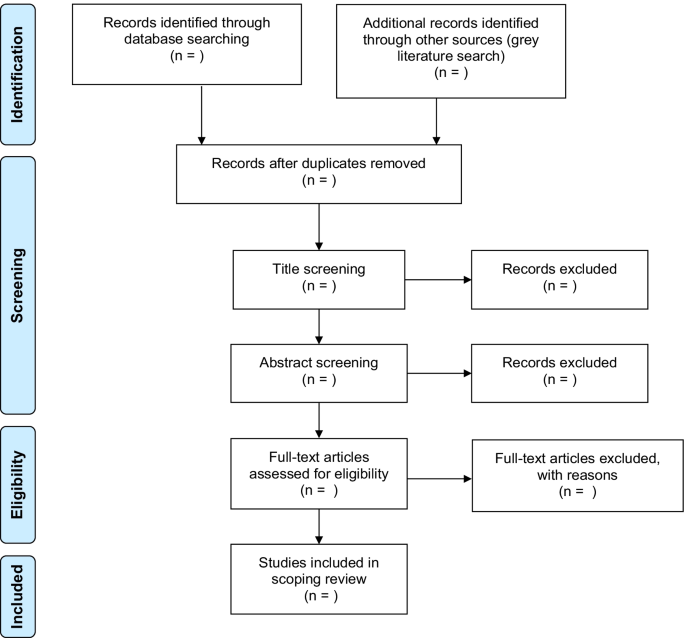

Similar to systematic reviews, the conduct of scoping reviews should be based on well-defined methodological guidance and reporting standards that include an a priori protocol, eligibility criteria and comprehensive search strategy [ 11 , 12 ]. Unlike systematic reviews, however, scoping reviews may be iterative and flexible and whilst any deviations from the protocol should be transparently reported, adjustments to the questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria and search may be made during the conduct of the review [ 4 , 14 ]. Unlike systematic reviews where implications or recommendations for practice are a key feature, scoping reviews are not designed to underpin clinical practice decisions; hence, assessment of methodological quality or risk of bias of included studies (which is critical when reporting effect size estimates) is not a mandatory step and often does not occur [ 10 , 12 ]. Rapid reviews are another popular review type, but as yet have no consistent, best practice methodology [ 19 ]. Rapid reviews can be understood to be streamlined forms of other review types (i.e. systematic, integrative and scoping reviews) [ 20 ].

Guidance to improve the quality of reporting of scoping reviews

Since the first 2005 framework for scoping reviews (then termed ‘scoping studies’) [ 13 ], the popularity of this approach has grown, with numbers doubling between 2014 and 2017 [ 2 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is the most up-to-date and advanced approach for reporting scoping reviews which is largely based on the popular PRISMA statement and checklist, the JBI methodological guidance and other approaches for undertaking scoping reviews [ 11 ]. Experts in evidence synthesis including authors of earlier guidance for scoping reviews developed the PRISMA-ScR checklist and explanation using a robust and comprehensive approach. Enhancing transparency and uniformity of reporting scoping reviews using the PRISMA-ScR can help to improve the quality and value of a scoping review to readers and end users [ 21 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is not a methodological guideline for review conduct, but rather a complementary checklist to support comprehensive reporting of methods and findings that can be used alongside other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. For this reason, authors who are more familiar with or prefer Arksey and O’Malley’s framework; Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s extension of that framework or JBI’s methodological guidance could each select their preferred methodological approach and report in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist.

Reasons for conducting a scoping review

Whilst systematic reviews sit at the top of the evidence hierarchy, the types of research questions they address are not suitable for every application [ 3 ]. Many indications more appropriately require a scoping review. For example, to explore the extent and nature of a body of literature, the development of evidence maps and summaries; to inform future research and reviews and to identify evidence gaps [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews are particularly useful where evidence is extensive and widely dispersed (i.e. many different types of evidence), or emerging and not yet amenable to questions of effectiveness [ 22 ]. Because scoping reviews are agnostic in terms of the types of evidence they can draw upon, they can be used to bring together and report upon heterogeneous literature—including both empirical and non-empirical evidence—across disciplines within and beyond health [ 23 , 24 , 25 ].

When deciding between whether to conduct a systematic review or a scoping review, authors should have a strong understanding of their differences and be able to clearly identify their review’s precise research objective(s) and/or question(s). Munn and colleagues noted that a systematic review is likely the most suitable approach if reviewers intend to address questions regarding the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness of a specified intervention [ 3 ]. There are also online resources for prospective authors [ 26 ]. A scoping review is probably best when research objectives or review questions involve exploring, identifying, mapping, reporting or discussing characteristics or concepts across a breadth of evidence sources.

Scoping reviews are increasingly used to respond to complex questions where comparing interventions may be neither relevant nor possible [ 27 ]. Often, cost, time, and resources are factors in decisions regarding review type. Whilst many scoping reviews can be quite large with numerous sources to screen and/or include, there is no expectation or possibility of statistical pooling, formal risk of bias rating, and quality of evidence assessment [ 28 , 29 ]. Topics where scoping reviews are necessary abound—for example, government organisations are often interested in the availability and applicability of tools to support health interventions, such as shared decision aids for pregnancy care [ 30 ]. Scoping reviews can also be applied to better understand complex issues related to the health workforce, such as how shift work impacts employee performance across diverse occupational sectors, which involves a diversity of evidence types as well as attention to knowledge gaps [ 31 ]. Another example is where more conceptual knowledge is required, for example, identifying and mapping existing tools [ 32 ]. Here, it is important to understand that scoping reviews are not the same as ‘realist reviews’ which can also be used to examine how interventions or programmes work. Realist reviews are typically designed to ellucide the theories that underpin a programme, examine evidence to reveal if and how those theories are relevant and explain how the given programme works (or not) [ 33 ].

Increased demand for scoping reviews to underpin high-quality knowledge translation across many disciplines within and beyond healthcare in turn fuels the need for consistency, clarity and rigour in reporting; hence, following recognised reporting guidelines is a streamlined and effective way of introducing these elements [ 34 ]. Standardisation and clarity of reporting (such as by using a published methodology and a reporting checklist—the PRISMA-ScR) can facilitate better understanding and uptake of the results of scoping reviews by end users who are able to more clearly understand the differences between systematic reviews, scoping reviews and literature reviews and how their findings can be applied to research, practice and policy.

Future directions in scoping reviews

The field of evidence synthesis is dynamic. Scoping review methodology continues to evolve to account for the changing needs and priorities of end users and the requirements of review authors for additional guidance regarding terminology, elements and steps of scoping reviews. Areas where ongoing research and development of scoping review guidance are occurring include inclusion of consultation with stakeholder groups such as end users and consumer representatives [ 35 ], clarity on when scoping reviews are the appropriate method over other synthesis approaches [ 3 ], approaches for mapping and presenting results in ways that clearly address the review’s research objective(s) and question(s) [ 29 ] and the assessment of the methodological quality of scoping reviews themselves [ 21 , 36 ]. The JBI Scoping Review Methodology group is currently working on this research agenda.

Consulting with end users, experts, or stakeholders has been a suggested but optional component of scoping reviews since 2005. Many of the subsequent approaches contained some reference to this useful activity. Stakeholder engagement is however often lost to the term ‘review’ in scoping reviews. Stakeholder engagement is important across all knowledge synthesis approaches to ensure relevance, contextualisation and uptake of research findings. In fact, it underlines the concept of integrated knowledge translation [ 37 , 38 ]. By including stakeholder consultation in the scoping review process, the utility and uptake of results may be enhanced making reviews more meaningful to end users. Stakeholder consultation can also support integrating knowledge translation efforts, facilitate identifying emerging priorities in the field not otherwise captured in the literature and may help build partnerships amongst stakeholder groups including consumers, researchers, funders and end users. Development in the field of evidence synthesis overall could be inspired by the incorporation of stakeholder consultation in scoping reviews and lead to better integration of consultation and engagement within projects utilising other synthesis methodologies. This highlights how further work could be conducted into establishing how and the extent to which scoping reviews have contributed to synthesising evidence and advancing scientific knowledge and understandings in a more general sense.

Currently, many methodological papers for scoping reviews are published in healthcare focussed journals and associated disciplines [ 6 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Another area where further work could also occur is to gain greater understanding on how scoping reviews and scoping review methodology is being used across disciplines beyond healthcare including how authors, reviewers and editors understand, recommend or utilise existing guidance for undertaking and reporting scoping reviews.

Whilst available guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping review has evolved over recent years, opportunities remain to further enhance and progress the methodology, uptake and application. Despite existing guidance, some publications using the term ‘scoping review’ continue to be conducted without apparent consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Because consistent and transparent reporting is widely recongised as important for supporting rigour, reproducibility and quality in research, we advocate for authors to use a stated scoping review methodology and to transparently report their conduct by using the PRISMA-ScR. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardising the use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the authors’ objective(s) and question(s) are also critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews. We contend that whilst the field of evidence synthesis and scoping reviews continues to evolve, use of the PRISMA-ScR is a valuable and practical tool for enhancing the quality of scoping reviews, particularly in combination with other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 44 ]. Scoping review methodology is developing as a policy and decision-making tool, and so ensuring the integrity of these reviews by adhering to the most up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well informed decision-making. As scoping review methodology continues to evolve alongside understandings regarding why authors do or do not use particular methodologies, we hope that future incarnations of scoping review methodology continues to provide useful, high-quality evidence to end users.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available upon request.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Article Google Scholar

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco A, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Paiva L, Dalmolin GL, Andolhe R, dos Santos W. Absenteeism of hospital health workers: scoping review. Av enferm. 2020;38(2):234–48.

Visonà MW, Plonsky L. Arabic as a heritage language: a scoping review. Int J Biling. 2019;24(4):599–615.

McKerricher L, Petrucka P. Maternal nutritional supplement delivery in developing countries: a scoping review. BMC Nutr. 2019;5(1):8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, De Micheli A, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:33–46.

Jowsey T, Foster G, Cooper-Ioelu P, Jacobs S. Blended learning via distance in pre-registration nursing education: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;44:102775.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: JBI; 2020.

Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):28.

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Inf Libr J. 2019;36(3):202–22.

Brady BR, De La Rosa JS, Nair US, Leischow SJ. Electronic cigarette policy recommendations: a scoping review. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):88–104.

Truman E, Elliott C. Identifying food marketing to teenagers: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):67.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. All in the family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):183.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Ghassemi M, et al. Same family, different species: methodological conduct and quality varies according to purpose for five types of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;96:133–42.

Barker M, Adelson P, Peters MDJ, Steen M. Probiotics and human lactational mastitis: a scoping review. Women Birth. 2020;33(6):e483–e491.

O’Donnell N, Kappen DL, Fitz-Walter Z, Deterding S, Nacke LE, Johnson D. How multidisciplinary is gamification research? Results from a scoping review. Extended abstracts publication of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play. Amsterdam: Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. p. 445–52.

O’Flaherty J, Phillips C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: a scoping review. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:85–95.

Di Pasquale V, Miranda S, Neumann WP. Ageing and human-system errors in manufacturing: a scoping review. Int J Prod Res. 2020;58(15):4716–40.

Knowledge Synthesis Team. What review is right for you? 2019. https://whatreviewisrightforyou.knowledgetranslation.net/

Lv M, Luo X, Estill J, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a scoping review. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(15):2000125.

Shemilt I, Simon A, Hollands GJ, et al. Pinpointing needles in giant haystacks: use of text mining to reduce impractical screening workload in extremely large scoping reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(1):31–49.

Khalil H, Bennett M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2020;18(1):95–100.

Kennedy K, Adelson P, Fleet J, et al. Shared decision aids in pregnancy care: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2020;81:102589.

Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:12–27.

Feo R, Conroy T, Wiechula R, Rasmussen P, Kitson A. Instruments measuring behavioural aspects of the nurse–patient relationship: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(11-12):1808–21.

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):33.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, et al. Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):31.

Cooper S, Cant R, Kelly M, et al. An evidence-based checklist for improving scoping review quality. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(3):230–240.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):208.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, Pham B, Straus SE, Langlois EV. Barriers, facilitators, strategies and outcomes to engaging policymakers, healthcare managers and policy analysts in knowledge synthesis: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013929.

Denton M, Borrego M. Funds of knowledge in STEM education: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;1(2):71–92.

Masta S, Secules S. When critical ethnography leaves the field and enters the engineering classroom: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;2(1):35–52.

Li Y, Marier-Bienvenue T, Perron-Brault A, Wang X, Pare G. Blockchain technology in business organizations: a scoping review. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii international conference on system sciences ; 2018. https://core.ac.uk/download/143481400.pdf

Houlihan M, Click A, Wiley C. Twenty years of business information literacy research: a scoping review. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2020;15(4):124–163.

Plug I, Stommel W, Lucassen P, Hartman T, Van Dulmen S, Das E. Do women and men use language differently in spoken face-to-face interaction? A scoping review. Rev Commun Res. 2021;9:43–79.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews - PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the other members of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) working group as well as Shazia Siddiqui, a research assistant in the Knowledge Synthesis Team in the Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto.

The authors declare that no specific funding was received for this work. Author ACT declares that she is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. KKO is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Episodic Disability and Rehabilitation with the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South Australia, UniSA Clinical and Health Sciences, Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre, Playford Building P4-27, City East Campus, North Terrace, Adelaide, 5000, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters & Casey Marnie

Adelaide Nursing School, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 101 Currie St, Adelaide, 5001, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters

The Centre for Evidence-based Practice South Australia (CEPSA): a Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 5006, Adelaide, South Australia

Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Terrence Donnelly Health Sciences Complex, 3359 Mississauga Rd, Toronto, Ontario, L5L 1C6, Canada

Heather Colquhoun

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute (RSI), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Heather Colquhoun & Kelly K. O’Brien

Knowledge Synthesis Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 1053 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1Y 4E9, Canada

Chantelle M. Garritty

Southern California Evidence Review Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, 90007, USA

Susanne Hempel

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 774 Echo Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5N8, Canada

Tanya Horsley

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Etienne V. Langlois

Sunnybrook Research Institute, 2075 Bayview Ave, Toronto, Ontario, M4N 3M5, Canada

Erin Lillie

Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Kelly K. O’Brien

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation (IHPME), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 155 College Street 4th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M6, Canada

UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Ӧzge Tunçalp

McMaster Health Forum, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Michael G. Wilson

Department of Health Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, 209 Victoria Street, East Building, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 1T8, Canada

Wasifa Zarin & Andrea C. Tricco

Epidemiology Division and Institute for Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College St, Room 500, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M7, Canada

Andrea C. Tricco

Queen’s Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, School of Nursing, Queen’s University, 99 University Ave, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 3N6, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MDJP, CM, HC, CMG, SH, TH, EVL, EL, KKO, OT, MGW, WZ and AT all made substantial contributions to the conception, design and drafting of the work. MDJP and CM prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrea C. Tricco .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Author ACT is an Associate Editor for the journal. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Peters, M.D.J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H. et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev 10 , 263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2021

Accepted : 27 September 2021

Published : 08 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scoping reviews

- Evidence synthesis

- Research methodology

- Reporting guidelines

- Methodological guidance

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 19 November 2018

Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach

- Zachary Munn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7091-5842 1 ,

- Micah D. J. Peters 1 ,

- Cindy Stern 1 ,

- Catalin Tufanaru 1 ,

- Alexa McArthur 1 &

- Edoardo Aromataris 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 18 , Article number: 143 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

816k Accesses

4310 Citations

721 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews are a relatively new approach to evidence synthesis and currently there exists little guidance regarding the decision to choose between a systematic review or scoping review approach when synthesising evidence. The purpose of this article is to clearly describe the differences in indications between scoping reviews and systematic reviews and to provide guidance for when a scoping review is (and is not) appropriate.

Researchers may conduct scoping reviews instead of systematic reviews where the purpose of the review is to identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature, clarify concepts or to investigate research conduct. While useful in their own right, scoping reviews may also be helpful precursors to systematic reviews and can be used to confirm the relevance of inclusion criteria and potential questions.

Conclusions

Scoping reviews are a useful tool in the ever increasing arsenal of evidence synthesis approaches. Although conducted for different purposes compared to systematic reviews, scoping reviews still require rigorous and transparent methods in their conduct to ensure that the results are trustworthy. Our hope is that with clear guidance available regarding whether to conduct a scoping review or a systematic review, there will be less scoping reviews being performed for inappropriate indications better served by a systematic review, and vice-versa.

Peer Review reports

Systematic reviews in healthcare began to appear in publication in the 1970s and 1980s [ 1 , 2 ]. With the emergence of groups such as Cochrane and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) in the 1990s [ 3 ], reviews have exploded in popularity both in terms of the number conducted [ 1 ], and their uptake to inform policy and practice. Today, systematic reviews are conducted for a wide range of purposes across diverse fields of inquiry, different evidence types and for different questions [ 4 ]. More recently, the field of evidence synthesis has seen the emergence of scoping reviews, which are similar to systematic reviews in that they follow a structured process, however they are performed for different reasons and have some key methodological differences [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Scoping reviews are now seen as a valid approach in those circumstances where systematic reviews are unable to meet the necessary objectives or requirements of knowledge users. There now exists clear guidance regarding the definition of scoping reviews, how to conduct scoping reviews and the steps involved in the scoping review process [ 6 , 8 ]. However, the guidance regarding the key indications or reasons why reviewers may choose to follow a scoping review approach is not as straightforward, with scoping reviews often conducted for purposes that do not align with the original indications as proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. As editors and peer reviewers for various journals we have noticed that there is inconsistency and confusion regarding the indications for scoping reviews and a lack of clarity for authors regarding when a scoping review should be performed as opposed to a systematic review. The purpose of this article is to provide practical guidance for reviewers on when to perform a systematic review or a scoping review, supported with some key examples.

Indications for systematic reviews

Systematic reviews can be broadly defined as a type of research synthesis that are conducted by review groups with specialized skills, who set out to identify and retrieve international evidence that is relevant to a particular question or questions and to appraise and synthesize the results of this search to inform practice, policy and in some cases, further research [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. According to the Cochrane handbook, a systematic review ‘uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made.’ [ 14 ] Systematic reviews follow a structured and pre-defined process that requires rigorous methods to ensure that the results are both reliable and meaningful to end users. These reviews may be considered the pillar of evidence-based healthcare [ 15 ] and are widely used to inform the development of trustworthy clinical guidelines [ 11 , 16 , 17 ].

A systematic review may be undertaken to confirm or refute whether or not current practice is based on relevant evidence, to establish the quality of that evidence, and to address any uncertainty or variation in practice that may be occurring. Such variations in practice may be due to conflicting evidence and undertaking a systematic review should (hopefully) resolve such conflicts. Conducting a systematic review may also identify gaps, deficiencies, and trends in the current evidence and can help underpin and inform future research in the area. Systematic reviews can be used to produce statements to guide clinical decision-making, the delivery of care, as well as policy development [ 12 ]. Broadly, indications for systematic reviews are as follows [ 4 ]:

Uncover the international evidence

Confirm current practice/ address any variation/ identify new practices

Identify and inform areas for future research

Identify and investigate conflicting results

Produce statements to guide decision-making

Despite the utility of systematic reviews to address the above indications, there are cases where systematic reviews are unable to meet the necessary objectives or requirements of knowledge users or where a methodologically robust and structured preliminary searching and scoping activity may be useful to inform the conduct of the systematic reviews. As such, scoping reviews (which are also sometimes called scoping exercises/scoping studies) [ 8 ] have emerged as a valid approach with rather different indications to those for systematic reviews. It is important to note here that other approaches to evidence synthesis have also emerged, including realist reviews, mixed methods reviews, concept analyses and others [ 4 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. This article focuses specifically on the choice between a systematic review or scoping review approach.

Indications for scoping reviews

True to their name, scoping reviews are an ideal tool to determine the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic and give clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available as well as an overview (broad or detailed) of its focus. Scoping reviews are useful for examining emerging evidence when it is still unclear what other, more specific questions can be posed and valuably addressed by a more precise systematic review [ 21 ]. They can report on the types of evidence that address and inform practice in the field and the way the research has been conducted.

The general purpose for conducting scoping reviews is to identify and map the available evidence [ 5 , 22 ]. Arskey and O’Malley, authors of the seminal paper describing a framework for scoping reviews, provided four specific reasons why a scoping review may be conducted [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 22 ]. Soon after, Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien further clarified and extended this original framework [ 7 ]. These authors acknowledged that at the time, there was no universally recognized definition of scoping reviews nor a commonly acknowledged purpose or indication for conducting them. In 2015, a methodological working group of the JBI produced formal guidance for conducting scoping reviews [ 6 ]. However, we have not previously addressed and expanded upon the indications for scoping reviews. Below, we build upon previously described indications and suggest the following purposes for conducting a scoping review:

To identify the types of available evidence in a given field

To clarify key concepts/ definitions in the literature

To examine how research is conducted on a certain topic or field

To identify key characteristics or factors related to a concept

As a precursor to a systematic review.

To identify and analyse knowledge gaps

Deciding between a systematic review and a scoping review approach

Authors deciding between the systematic review or scoping review approach should carefully consider the indications discussed above for each synthesis type and determine exactly what question they are asking and what purpose they are trying to achieve with their review. We propose that the most important consideration is whether or not the authors wish to use the results of their review to answer a clinically meaningful question or provide evidence to inform practice. If the authors have a question addressing the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness of a certain treatment or practice, then a systematic review is likely the most valid approach [ 11 , 23 ]. However, authors do not always wish to ask such single or precise questions, and may be more interested in the identification of certain characteristics/concepts in papers or studies, and in the mapping, reporting or discussion of these characteristics/concepts. In these cases, a scoping review is the better choice.

As scoping reviews do not aim to produce a critically appraised and synthesised result/answer to a particular question, and rather aim to provide an overview or map of the evidence. Due to this, an assessment of methodological limitations or risk of bias of the evidence included within a scoping review is generally not performed (unless there is a specific requirement due to the nature of the scoping review aim) [ 6 ]. Given this assessment of bias is not conducted, the implications for practice (from a clinical or policy making point of view) that arise from a scoping review are quite different compared to those of a systematic review. In some cases, there may be no need or impetus to make implications for practice and if there is a need to do so, these implications may be significantly limited in terms of providing concrete guidance from a clinical or policy making point of view. Conversely, when we compare this to systematic reviews, the provision of implications for practice is a key feature of systematic reviews and is recommended in reporting guidelines for systematic reviews [ 13 ].

Exemplars for different scoping review indications

In the following section, we elaborate on each of the indications listed for scoping reviews and provide a number of examples for authors considering a scoping review approach.

Scoping reviews that seek to identify the types of evidence in a given field share similarities with evidence mapping activities as explained by Bragge and colleagues in a paper on conducting scoping research in broad topic areas [ 24 ]. Chambers and colleagues [ 25 ] conducted a scoping review in order to identify current knowledge translation resources (and any evaluations of them) that use, adapt and present findings from systematic reviews to suit the needs of policy makers. Following a comprehensive search across a range of databases, organizational websites and conference abstract repositories based upon predetermined inclusion criteria, the authors identified 20 knowledge translation resources which they classified into three different types (overviews, summaries and policy briefs) as well as seven published and unpublished evaluations. The authors concluded that evidence synthesists produce a range of resources to assist policy makers to transfer and utilize the findings of systematic reviews and that focussed summaries are the most common. Similarly, a scoping review was conducted by Challen and colleagues [ 26 ] in order to determine the types of available evidence identifying the source and quality of publications and grey literature for emergency planning. A comprehensive set of databases and websites were investigated and 1603 relevant sources of evidence were identified mainly addressing emergency planning and response with fewer sources concerned with hazard analysis, mitigation and capability assessment. Based on the results of the review, the authors concluded that while there is a large body of evidence in the field, issues with its generalizability and validity are as yet largely unknown and that the exact type and form of evidence that would be valuable to knowledge users in the field is not yet understood.

To clarify key concepts/definitions in the literature

Scoping reviews are often performed to examine and clarify definitions that are used in the literature. A scoping review by Schaink and colleagues 27 was performed to investigate how the notion of “patient complexity” had been defined, classified, and understood in the existing literature. A systematic search of healthcare databases was conducted. Articles were assessed to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria and the findings of included articles were grouped into five health dimensions. An overview of how complexity has been described was presented, including the varying definitions and interpretations of the term. The results of the scoping review enabled the authors to then develop a complexity framework or model to assist in defining and understanding patient complexity [ 27 ].

Hines et al. [ 28 ] provide a further example where a scoping review has been conducted to define a concept, in this case the condition bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The authors revealed significant variation in how the condition was defined across the literature, prompting the authors to call for a ‘comprehensive and evidence-based definition’. [ 28 ]

To examine how research is conducted on a certain topic

Scoping reviews can be useful tools to investigate the design and conduct of research on a particular topic. A scoping review by Callary and colleagues 29 investigated the methodological design of studies assessing wear of a certain type of hip replacement (highly crosslinked polyethylene acetabular components) [ 29 ]. The aim of the scoping review was to survey the literature to determine how data pertinent to the measurement of hip replacement wear had been reported in primary studies and whether the methods were similar enough to allow for comparison across studies. The scoping review revealed that the methods to assess wear (radiostereometric analysis) varied significantly with many different approaches being employed amongst the investigators. The results of the scoping review led to the authors recommending enhanced standardization in measurements and methods for future research in this field [ 29 ].

There are other examples of scoping reviews investigating research methodology, with perhaps the most pertinent examples being two recent scoping reviews of scoping review methods [ 9 , 10 ]. Both of these scoping reviews investigated how scoping reviews had been reported and conducted, with both advocating for a need for clear guidance to improve standardization of methods [ 9 , 10 ]. Similarly, a scoping review investigating methodology was conducted by Tricco and colleagues 30 on rapid review methods that have been evaluated, compared, used or described in the literature. A variety of rapid review approaches were identified with many instances of poor reporting identified. The authors called for prospective studies to compare results presented by rapid reviews versus systematic reviews.

Scoping reviews can be conducted to identify and examine characteristics or factors related to a particular concept. Harfield and colleagues (2015) conducted a scoping review to identify the characteristics of indigenous primary healthcare service delivery models [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. A systematic search was conducted, followed by screening and study selection. Once relevant studies had been identified, a process of data extraction commenced to extract characteristics referred to in the included papers. Over 1000 findings were eventually grouped into eight key factors (accessible health services, community participation, culturally appropriate and skilled workforce, culture, continuous quality improvement, flexible approaches to care, holistic health care, self-determination and empowerment). The results of this scoping review have been able to inform a best practice model for indigenous primary healthcare services.

Scoping reviews conducted as precursors to systematic reviews may enable authors to identify the nature of a broad field of evidence so that ensuing reviews can be assured of locating adequate numbers of relevant studies for inclusion. They also enable the relevant outcomes and target group or population for example for a particular intervention to be identified. This can have particular practical benefits for review teams undertaking reviews on less familiar topics and can assist the team to avoid undertaking an “empty” review [ 33 ]. Scoping reviews of this kind may help reviewers to develop and confirm their a priori inclusion criteria and ensure that the questions to be posed by their subsequent systematic review are able to be answered by available, relevant evidence. In this way, systematic reviews are able to be underpinned by a preliminary and evidence-based scoping stage.

A scoping review commissioned by the United Kingdom Department for International Development was undertaken to determine the scope and nature of literature on people’s experiences of microfinance. The results of this scoping review were used to inform the development of targeted systematic review questions that focussed upon areas of particular interest [ 34 ].

In their recent scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews, Tricco and colleagues 10 reveal only 12% of scoping reviews contained recommendations for the development of ensuing systematic reviews, suggesting that the majority of scoping review authors do not conduct scoping reviews as a precursor to future systematic reviews.

To identify and analyze gaps in the knowledge base

Scoping reviews are rarely solely conducted to simply identify and analyze gaps present in a given knowledge base, as examination and presentation of what hasn’t been investigated or reported generally requires exhaustive examination of all of what is available. In any case, because scoping reviews tend to be a useful approach for reviewing evidence rapidly in emerging fields or topics, identification and analysis of knowledge gaps is a common and valuable indication for conducting a scoping review. A scoping review was recently conducted to review current research and identify knowledge gaps on the topic of “occupational balance”, or the balance of work, rest, sleep, and play [ 35 ]. Following a systematic search across a range of relevant databases, included studies were selected and in line with predetermined inclusion criteria, were described and mapped to provide both an overall picture of the current state of the evidence in the field and to identify and highlight knowledge gaps in the area. The results of the scoping review allowed the authors to illustrate several research ‘gaps’, including the absence of studies conducted outside of western societies, the lack of knowledge around peoples’ levels of occupational balance, as well as a dearth of evidence regarding how occupational balance may be enhanced. As with other scoping reviews focussed upon identifying and analyzing knowledge gaps, results such as these allow for the identification of future research initiatives.

Scoping reviews are now seen as a valid review approach for certain indications. A key difference between scoping reviews and systematic reviews is that in terms of a review question, a scoping review will have a broader “scope” than traditional systematic reviews with correspondingly more expansive inclusion criteria. In addition, scoping reviews differ from systematic reviews in their overriding purpose. We have previously recommended the use of the PCC mnemonic (Population, Concept and Context) to guide question development [ 36 ]. The importance of clearly defining the key questions and objectives of a scoping review has been discussed previously by one of the authors, as a lack of clarity can result in difficulties encountered later on in the review process [ 36 ].

Considering their differences from systematic reviews, scoping reviews should still not be confused with traditional literature reviews. Traditional literature reviews have been used as a means to summarise various publications or research on a particular topic for many years. In these traditional reviews, authors examine research reports in addition to conceptual or theoretical literature that focuses on the history, importance, and collective thinking around a topic, issue or concept. These types of reviews can be considered subjective, due to their substantial reliance on the author’s pre-exiting knowledge and experience and as they do not normally present an unbiased, exhaustive and systematic summary of a topic [ 12 ]. Regardless of some of these limitations, traditional literature reviews may still have some use in terms of providing an overview of a topic or issue. Scoping reviews provide a useful alternative to literature reviews when clarification around a concept or theory is required. If traditional literature reviews are contrasted with scoping reviews, the latter [ 6 ]:

Are informed by an a priori protocol

Are systematic and often include exhaustive searching for information

Aim to be transparent and reproducible

Include steps to reduce error and increase reliability (such as the inclusion of multiple reviewers)

Ensure data is extracted and presented in a structured way

Another approach to evidence synthesis that has emerged recently is the production of evidence maps [ 37 ]. The purpose of these evidence maps is similar to scoping reviews to identify and analyse gaps in the knowledge base [ 37 , 38 ]. In fact, most evidence mapping articles cite seminal scoping review guidance for their methods [ 38 ]. The two approaches therefore have many similarities, with perhaps the most prominent difference being the production of a visual database or schematic (i.e. map) which assists the user in interpreting where evidence exists and where there are gaps [ 38 ]. As Miake-Lye states, at this stage ‘it is difficult to determine where one method ends and the other begins.’ [ 38 ] Both approaches may be valid when the indication is for determining the extent of evidence on a particular topic, particularly when highlighting gaps in the research.

A further popular method to define and scope concepts, particularly in nursing, is through the conduct of a concept analysis [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Formal concept analysis is ‘a process whereby concepts are logically and systematically investigated to form clear and rigorously constructed conceptual definitions,’ [ 42 ] which is similar to scoping reviews where the indication is to clarify concepts in the literature. There is limited methodological guidance on how to conduct a concept analysis and recently they have been critiqued for having no impact on practice [ 39 ]. In our opinion, scoping reviews (where the purpose is to systematically investigate a concept in the literature) offer a methodologically rigorous alternative to concept analysis with their results perhaps being more useful to inform practice.

Comparing and contrasting the characteristics of traditional literature reviews, scoping reviews and systematic reviews may help clarify the true essence of these different types of reviews (see Table 1 ).

Rapid reviews are another emerging type of evidence synthesis and a substantial amount of literature have addressed these types of reviews [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. There are various definitions for rapid reviews, and for simplification purposes, we define these review types as ‘systematic reviews with shortcuts.’ In this paper, we have not discussed the choice between a rapid or systematic review approach as we are of the opinion that perhaps the major consideration for conducting a rapid review (as compared to a systematic or scoping review) is not the purpose/question itself, but the feasibility of conducting a full review given financial/resource limitations and time pressures. As such, a rapid review could potentially be conducted for any of the indications listed above for the scoping or systematic review, whilst shortening or skipping entirely some steps in the standard systematic or scoping review process.

There is some overlap across the six listed purposes for conducting a scoping review described in this paper. For example, it is logical to presume that if a review group were aiming to identify the types of available evidence in a field they would also be interested in identifying and analysing gaps in the knowledge base. Other combinations of purposes for scoping reviews would also make sense for certain questions/aims. However, we have chosen to list them as discrete reasons in this paper in an effort to provide some much needed clarity on the appropriate purposes for conducting scoping reviews. As such, scoping review authors should not interpret our list of indications as a discrete list where only one purpose can be identified.

It is important to mention some potential abuses of scoping reviews. Reviewers may conduct a scoping review as an alternative to a systematic review in order to avoid the critical appraisal stage of the review and expedite the process, thinking that a scoping review may be easier than a systematic review to conduct. Other reviewers may conduct a scoping review in order to ‘map’ the literature when there is no obvious need for ‘mapping’ in this particular subject area. Others may conduct a scoping review with very broad questions as an alternative to investing the time and effort required to craft the necessary specific questions required for undertaking a systematic review. In these cases, scoping reviews are not appropriate and authors should refer to our guidance regarding whether they should be conducting a systematic review instead.

This article provides some clarification on when to conduct a scoping review as compared to a systematic review and clear guidance on the purposes for conducting a scoping review. We hope that this paper will provide a useful addition to this evolving methodology and encourage others to review, modify and build upon these indications as the approach matures. Further work in scoping review methods is required, with perhaps the most important advancement being the recent development of an extension to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for scoping reviews [ 48 ] and the development of software and training programs to support these reviews [ 49 , 50 ]. As the methodology advances, guidance for scoping reviews (such as that included in the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual) will require revision, refining and updating.

Scoping reviews are a useful tool in the ever increasing arsenal of evidence synthesis approaches. Researchers may preference the conduct of a scoping review over a systematic review where the purpose of the review is to identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature, clarify concepts, investigate research conduct, or to inform a systematic review. Although conducted for different purposes compared to systematic reviews, scoping reviews still require rigorous and transparent methods in their conduct to ensure that the results are trustworthy. Our hope is that with clear guidance available regarding whether to conduct a scoping review or a systematic review, there will be less scoping reviews being performed for inappropriate indications better served by a systematic review, and vice-versa.

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326.

Article Google Scholar

Chalmers I, Hedges LV, Cooper H. A brief history of research synthesis. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25(1):12–37.

Jordan Z, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Lockwood C. Now that we're here, where are we? The JBI approach to evidence-based healthcare 20 years on. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):117–20.

Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):5.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15.

Pearson A. Balancing the evidence: incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews. JBI Reports. 2004;2:45–64.

Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2014;114(3):53–8.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;339:b2700.

Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. ed: The Cochrane Collaboration 2011.

Munn Z, Porritt K, Lockwood C, Aromataris E, Pearson A. Establishing confidence in the output of qualitative research synthesis: the ConQual approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:108.

Pearson A, Jordan Z, Munn Z. Translational science and evidence-based healthcare: a clarification and reconceptualization of how knowledge is generated and used in healthcare. Nursing research and practice. 2012;2012:792519.

Steinberg E, Greenfield S, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Graham R. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews. 2012;1:28.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Moher D. The art and science of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):11–20.

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–50.

Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2008;6(1):1.

Pearson A, Wiechula R, Court A, Lockwood C. The JBI model of evidence-based healthcare. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2005;3(8):207–15.

PubMed Google Scholar

Bragge P, Clavisi O, Turner T, Tavender E, Collie A, Gruen RL. The global evidence mapping initiative: scoping research in broad topic areas. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:92.

Chambers D, Wilson PM, Thompson CA, Hanbury A, Farley K, Light K. Maximizing the impact of systematic reviews in health care decision making: a systematic scoping review of knowledge-translation resources. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):131–56.

Challen K, Lee AC, Booth A, Gardois P, Woods HB, Goodacre SW. Where is the evidence for emergency planning: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:542.

Schaink AK, Kuluski K, Lyons RF, et al. A scoping review and thematic classification of patient complexity: offering a unifying framework. Journal of comorbidity. 2012;2(1):1–9.

Hines D, Modi N, Lee SK, Isayama T, Sjörs G, Gagliardi L, Lehtonen L, Vento M, Kusuda S, Bassler D, Mori R. Scoping review shows wide variation in the definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants and calls for a consensus. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(3):366–74.

Callary SA, Solomon LB, Holubowycz OT, Campbell DG, Munn Z, Howie DW. Wear of highly crosslinked polyethylene acetabular components. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(2):159–68.

Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):163.

Harfield S, Davy C, Kite E, et al. Characteristics of indigenous primary health care models of service delivery: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(11):43–51.

Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N. Characteristics of indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):12.

Peters MDJ LC, Munn Z, Moola S, Mishra RK (2015) , Protocol. Adelaide: the Joanna Briggs Institute UoA. What are people’s views and experiences of delivering and participating in microfinance interventions? A systematic review of qualitative evidence from South Asia.

Peters MDJ LC, Munn Z, Moola S, Mishra RK People’s views and experiences of participating in microfinance interventions: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. London: EPPI-Centre: social science research unit, UCL Institute of education, University College London; 2016.

Wagman P, Håkansson C, Jonsson H. Occupational balance: a scoping review of current research and identified knowledge gaps. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(2):160–9.

Peters MD. In no uncertain terms: the importance of a defined objective in scoping reviews. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(2):1–4.

Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Callahan P, Purcell R. Evidence mapping: illustrating an emerging methodology to improve evidence-based practice in youth mental health. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(6):1025–30.

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic reviews. 2016;5(1):1.

Draper P. A critique of concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(6):1207–8.

Gibson CH. A concept analysis of empowerment. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16(3):354–61.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Meeberg GA. Quality of life: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(1):32–8.

Ream E, Richardson A. Fatigue: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996;33(5):519–29.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224.

Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. 2010;5:56.

Harker J, Kleijnen J. What is a rapid review? A methodological exploration of rapid reviews in health technology assessments. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012;10(4):397–410.

Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10.

Munn Z, Lockwood C, Moola S. The development and use of evidence summaries for point of care information systems: a streamlined rapid review approach. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2015;12(3):131–8.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Munn Z, Aromataris E, Tufanaru C, Stern C, Porritt K, Farrow J, Lockwood C, Stephenson M, Moola S, Lizarondo L, McArthur A. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the Joanna Briggs institute system for the unified management, assessment and review of information (JBI SUMARI). Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2018. (in press)

Stern C, Munn Z, Porritt K, et al. An international educational training course for conducting systematic reviews in health care: the Joanna Briggs Institute's comprehensive systematic review training program. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2018;15(5):401–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

No funding was provided for this paper.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Joanna Briggs Institute, The University of Adelaide, 55 King William Road, North Adelaide, 5005, South Australia

Zachary Munn, Micah D. J. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur & Edoardo Aromataris

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZM: Led the development of this paper and conceptualised the idea for a paper on indications for scoping reviews. Provided final approval for submission. MP: Contributed conceptually to the paper and wrote sections of the paper. Provided final approval for submission. CS: Contributed conceptually to the paper and wrote sections of the paper. Provided final approval for submission. CT: Contributed conceptually to the paper and wrote sections of the paper. Provided final approval for submission. AM: Contributed conceptually to the paper and reviewed and provided feedback on all drafts. Provided final approval for submission. EA: Contributed conceptually to the paper and reviewed and provided feedback on all drafts. Provided approval and encouragement for the work to proceed. Provided final approval for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zachary Munn .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

All the authors are members of the Joanna Briggs Institute, an evidence-based healthcare research institute which provides formal guidance regarding evidence synthesis, transfer and implementation. Zachary Munn is a member of the editorial board of this journal. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C. et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18 , 143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Download citation

Received : 21 February 2018

Accepted : 06 November 2018

Published : 19 November 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

- Scoping review

- Evidence-based healthcare

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews

- Differentiating the Three Review Types

Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews: Differentiating the Three Review Types

- Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps

- Working with Keywords/Subject Headings

- Citing Research

The Differences in the Review Types

Grant, M.J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. H ealth Information & Libraries Journal , 26: 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x The objective of this study is to provide descriptive insight into the most common types of reviews, with illustrative examples from health and health information domains.

- What Type of Review is Right for you (Cornell University)

Literature Reviews

Literature Review: it is a product and a process.

As a product , it is a carefully written examination, interpretation, evaluation, and synthesis of the published literature related to your topic. It focuses on what is known about your topic and what methodologies, models, theories, and concepts have been applied to it by others.

The process is what is involved in conducting a review of the literature.

- It is ongoing

- It is iterative (repetitive)

- It involves searching for and finding relevant literature.

- It includes keeping track of your references and preparing and formatting them for the bibliography of your thesis

- Literature Reviews (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews are a " preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature . Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)." Grant and Booth (2009).

Scoping reviews are not mapping reviews: Scoping reviews are more topic based and mapping reviews are more question based.

- examining emerging evidence when specific questions are unclear - clarify definitions and conceptual boundaries

- identify and map the available evidence

- a scoping review is done prior to a systematic review

- to summarize and disseminate research findings in the research literature

- identify gaps with the intention of resolution by future publications

- Scoping review timeframe and limitations (Touro College of Pharmacy

Systematic Reviews

Many evidence-based disciplines use ‘systematic reviews," this type of review is a specific methodology that aims to comprehensively identify all relevant studies on a specific topic, and to select appropriate studies based on explicit criteria . ( https://cebma.org/faq/what-is-a-systematic-review/ )

- clearly defined search criteria

- an explicit reproducible methodology

- a systematic search of the literature with the defined criteria met

- assesses validity of the findings - no risk of bias

- a comprehensive report on the findings, apparent transparency in the results

- Better evidence for a better world Browsable collection of systematic reviews

- Systematic Reviews in the Health Sciences by Molly Maloney Last Updated Jan 8, 2024 360 views this year

- Next: Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps >>

What is a Scoping Review?

- Peer Review

Academic conferences often get overlooked when it comes to research promotion. They are a great way to show off your research through public speaking and visual graphs. Increase your citations by promoting your research at an academic conference.