Little Albert Experiment (Watson & Rayner)

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Watson and Rayner (1920) conducted the Little Albert Experiment to answer 3 questions:

Can an infant be conditioned to fear an animal that appears simultaneously with a loud, fear-arousing sound?

Would such fear transfer to other animals or inanimate objects?

How long would such fears persist?

Little Albert Experiment

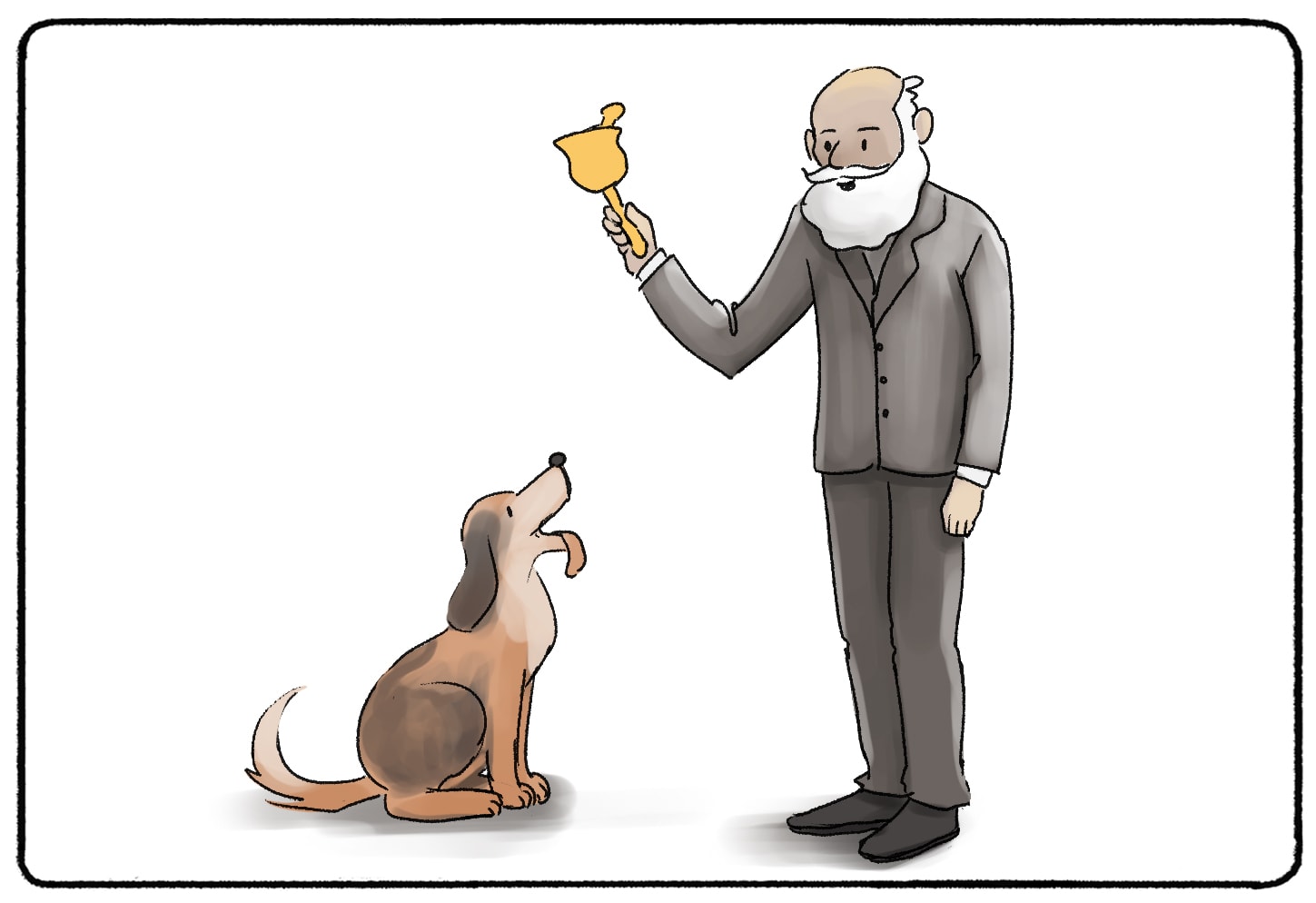

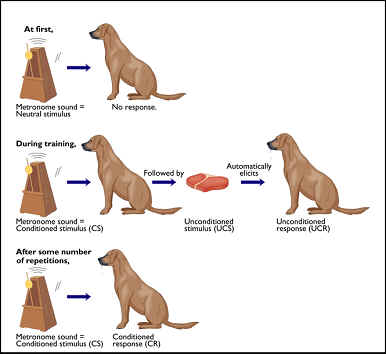

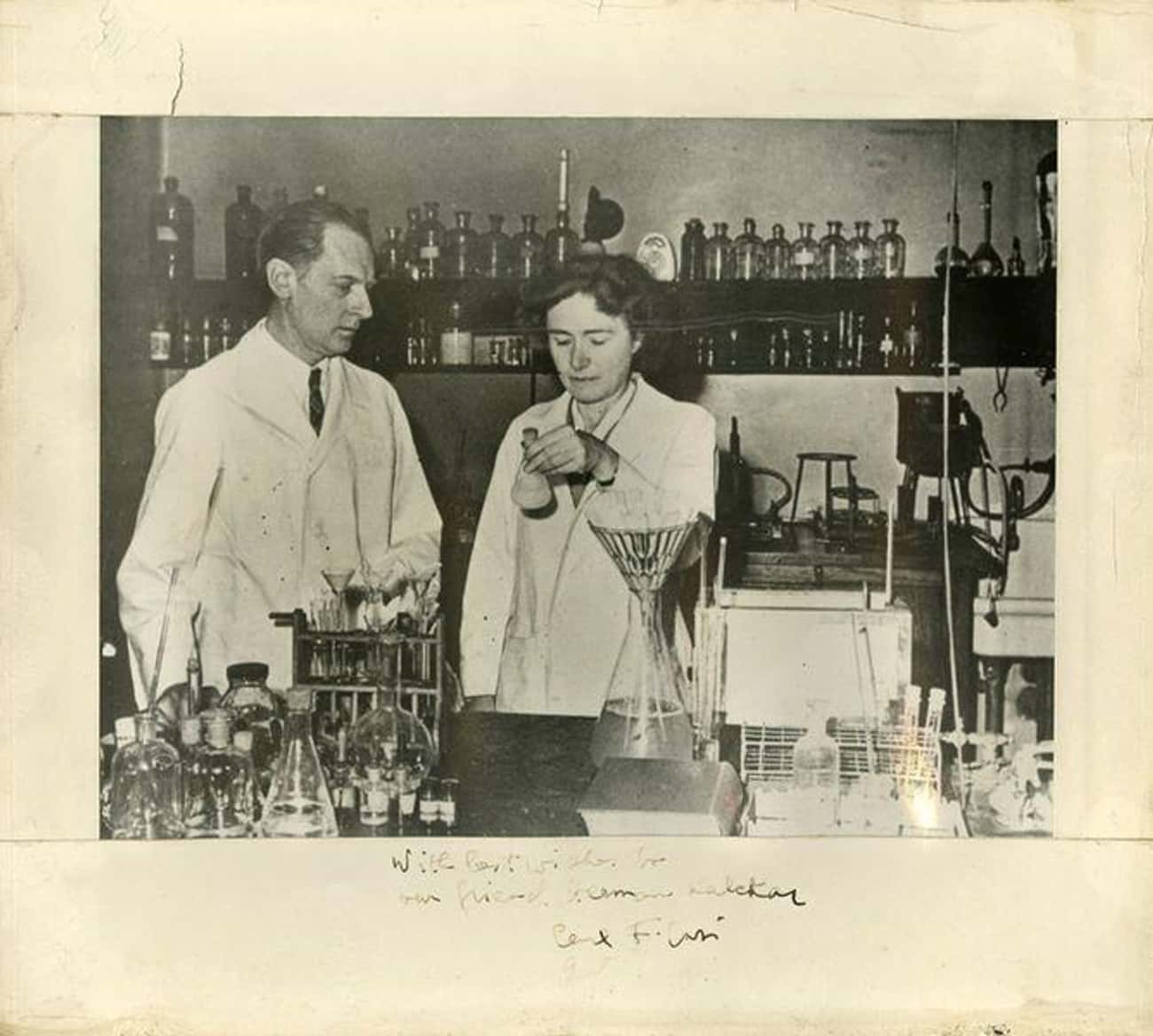

Ivan Pavlov showed that classical conditioning applied to animals. Did it also apply to humans? In a famous (though ethically dubious) experiment, John Watson and Rosalie Rayner showed it did.

Conducted at Johns Hopkins University between 1919 and 1920, the Little Albert experiment aimed to provide experimental evidence for classical conditioning of emotional responses in infants

At the study’s outset, Watson and Rayner encountered a nine-month-old boy named “Little Albert” (his real name was Albert Barger) – a remarkably fearless child, scared only by loud noises.

After gaining permission from Albert’s mother, the researchers decided to test the process of classical conditioning on a human subject – by inducing a further phobia in the child.

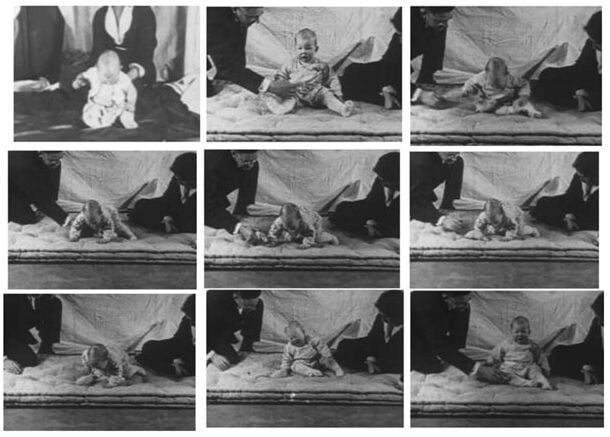

The baseline session occurred when Albert was approximately nine months old to test his reactions to neutral stimuli.

Albert was reportedly unafraid of any of the stimuli he was shown, which consisted of “a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, with [sic] masks with and without hair, cotton wool, burning newspapers, etc.” (Watson & Rayner, 1920, p. 2).

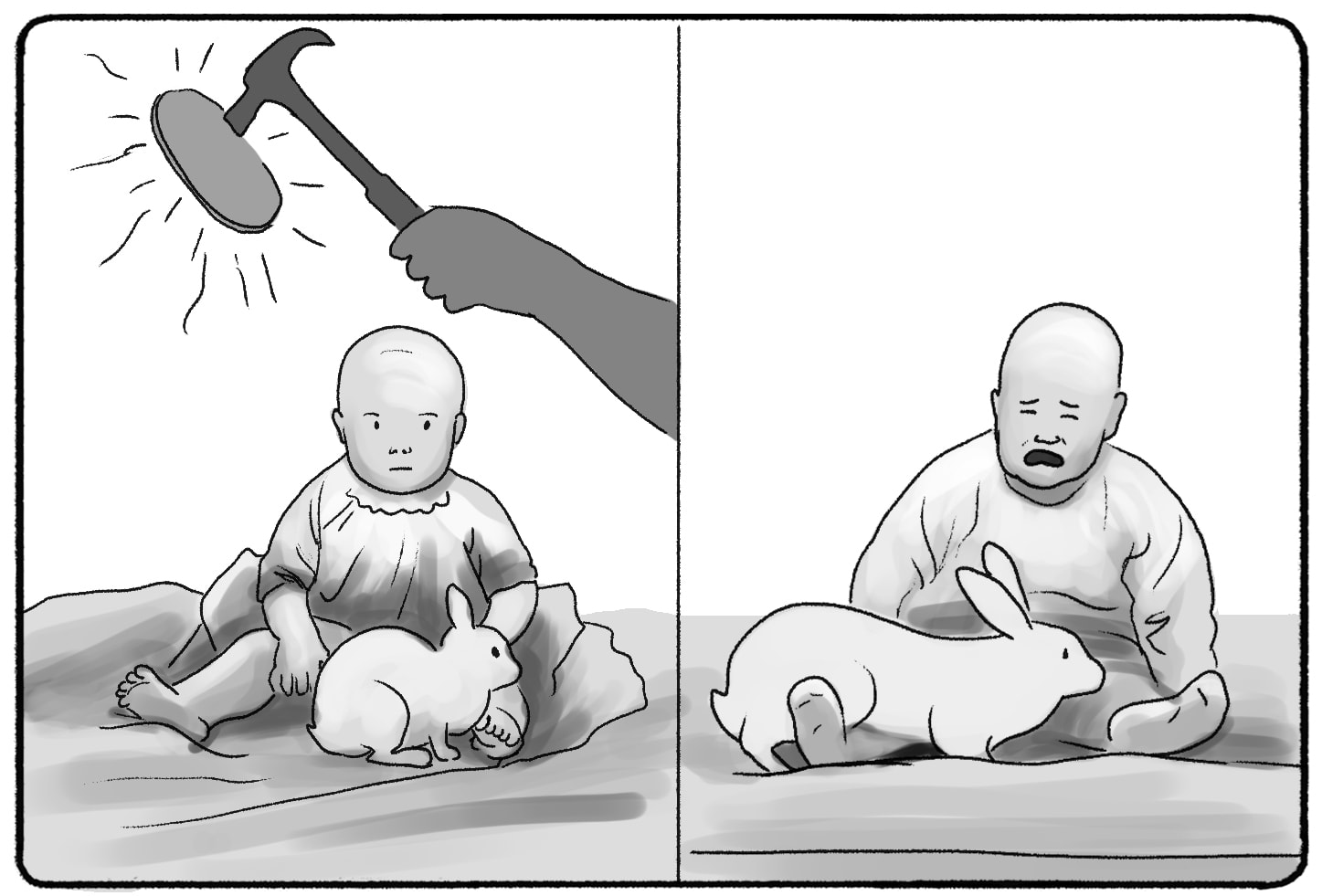

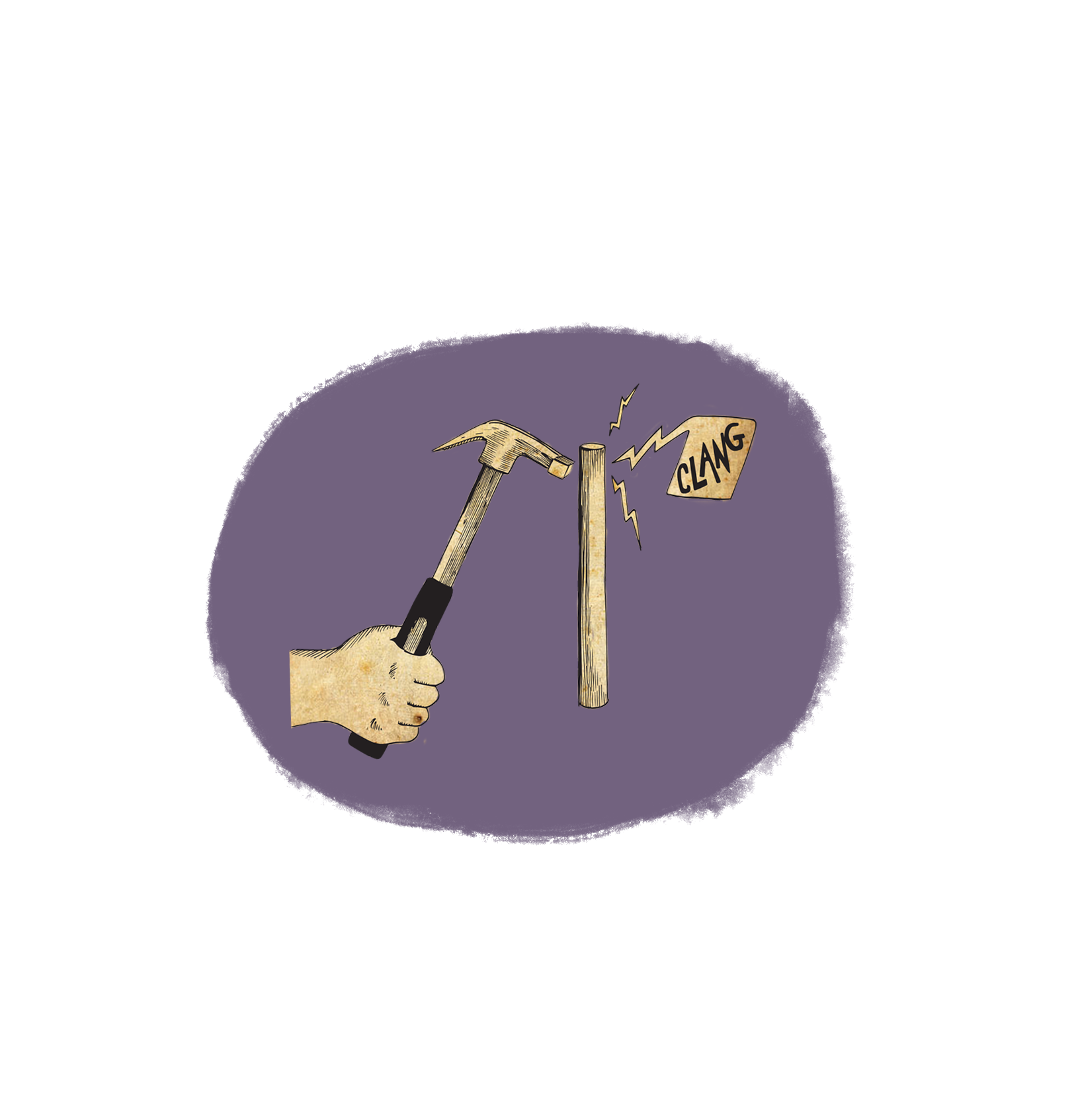

Approximately two months after the baseline session, Albert was subjected during two conditioning sessions spaced one week apart to a total of seven pairings of a white rat followed by the startling sound of a steel bar being struck with a hammer.

When Little Albert was just over 11 months old, the white rat was presented, and seconds later, the hammer was struck against the steel bar.

After seven pairings of the rat and noise (in two sessions, one week apart), Albert reacted with crying and avoidance when the rat was presented without the loud noise.

By the end of the second conditioning session, when Albert was shown the rat, he reportedly cried and “began to crawl away so rapidly that he was caught with difficulty before reaching the edge of the table” (p. 5). Watson and Rayner interpreted these reactions as evidence of fear conditioning.

By now, little Albert only had to see the rat and immediately showed every sign of fear. He would cry (whether or not the hammer was hit against the steel bar), and he would attempt to crawl away.

The two conditioning sessions were followed by three transfer sessions. During the first transfer session, Albert was shown the rat to assess maintained fear, as well as other furry objects to test generalization.

Complicating the experiment, however, the second transfer session also included two additional conditioning trials with the rat to “freshen up the reaction” (Watson & Rayner, 1920, p. 9), as well as conditioning trials in which a dog and a rabbit were, for the first time, also paired with the loud noise.

This fear began to fade as time went on, however, the association could be renewed by repeating the original procedure a few times.

Unlike prior weekly sessions, the final transfer session occurred after a month to test maintained fear. Immediately following the session, Albert and his mother left the hospital, preventing Watson and Rayner from carrying out their original intention of deconditioning the fear they have classically conditioned.

Experimental Procedure

Classical conditioning.

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): This is a stimulus that, before conditioning, does not naturally bring about the response of interest. In this case, the Neutral Stimulus was the white laboratory rat. Initially, Little Albert had no fear of the rat, he was interested in the rat and wanted to play with it.

- Unconditioned Stimulus (US): This is a stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without any learning. In the experiment, the unconditioned stimulus was the loud, frightening noise. This noise was produced by Watson and Rayner striking a steel bar with a hammer behind Albert’s back.

- Unconditioned Response (UR): This is the natural response that occurs when the Unconditioned Stimulus is presented. It is unlearned and occurs without previous conditioning. In this case, the Unconditioned Response was Albert’s fear response to the loud noise – crying and showing distress.

- Conditioning Process: Watson and Rayner then began the conditioning process. They presented the rat (NS) to Albert, and then, while he was interacting with the rat, they made a loud noise (US). This was done repeatedly, pairing the sight of the rat with the frightening noise. As a result, Albert started associating the rat with the fear he experienced due to the loud noise.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): After several pairings, the previously Neutral Stimulus (the rat) becomes the conditioned stimulus , as it now elicits the fear response even without the presence of the loud noise.

- Conditioned Response (CR): This is the learned response to the previously neutral stimulus, which is now the Conditioned Stimulus. In this case, the Conditioned Response was Albert’s fear of the rat. Even without the loud noise, he became upset and showed signs of fear whenever he saw the rat.

In this experiment, a previously unafraid baby was conditioned to become afraid of a rat. It also demonstrates two additional concepts, originally outlined by Pavlov .

- Extinction : Although a conditioned association can be incredibly strong initially, it begins to fade if not reinforced – until is disappears completely.

- Generalization : Conditioned associations can often widen beyond the specific stimuli presented. For instance, if a child develops a negative association with one teacher, this association might also be made with others.

Over the next few weeks and months, Little Albert was observed and ten days after conditioning his fear of the rat was much less marked. This dying out of a learned response is called extinction.

However, even after a full month, it was still evident, and the association could be renewed by repeating the original procedure a few times.

Unfortunately, Albert’s mother withdrew him from the experiment the day the last tests were made, and Watson and Rayner were unable to conduct further experiments to reverse the condition response.

- The Little Albert experiment was a controversial psychology experiment by John B. Watson and his graduate student, Rosalie Rayner, at Johns Hopkins University.

- The experiment was performed in 1920 and was a case study aimed at testing the principles of classical conditioning.

- Watson and Raynor presented Little Albert (a nine-month-old boy) with a white rat, and he showed no fear. Watson then presented the rat with a loud bang that startled Little Albert and made him cry.

- After the continuous association of the white rat and loud noise, Little Albert was classically conditioned to experience fear at the sight of the rat.

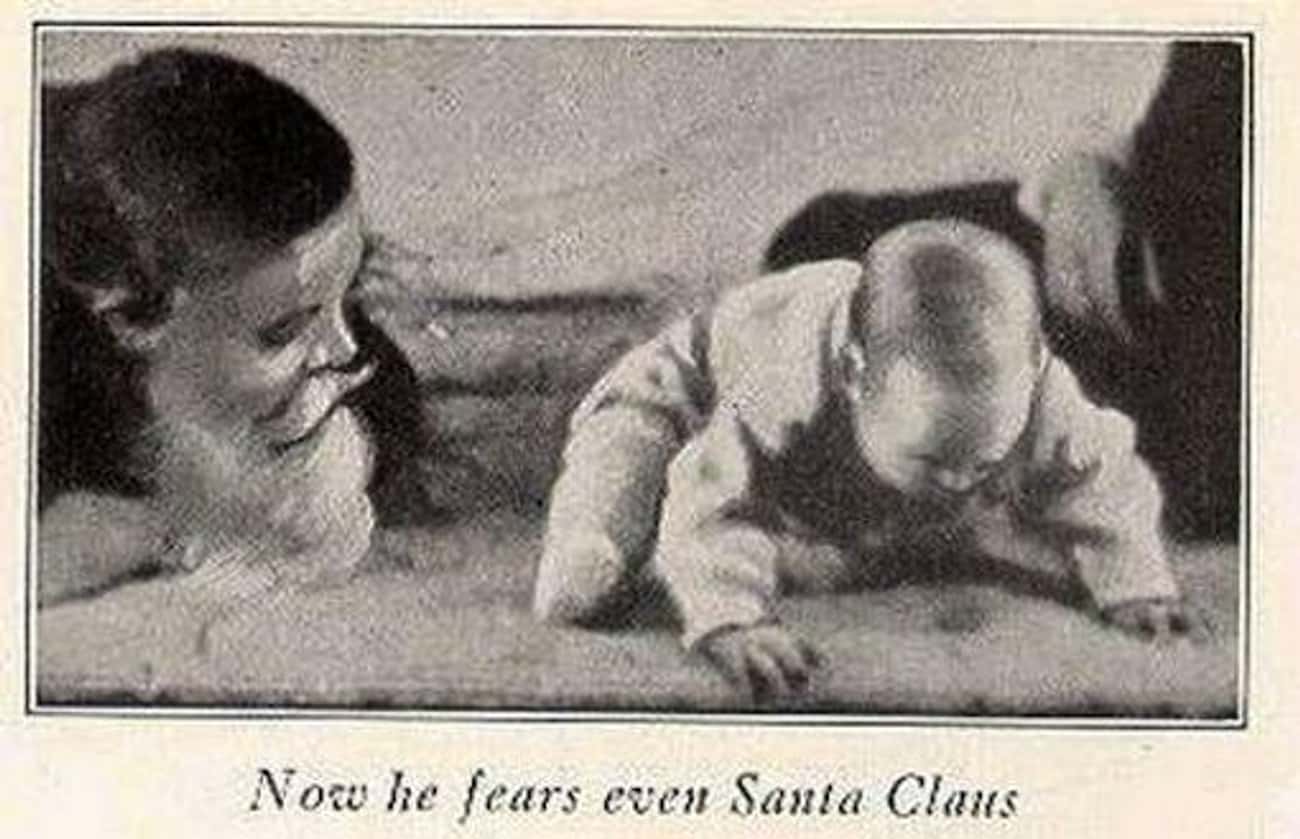

- Albert’s fear generalized to other stimuli that were similar to the rat, including a fur coat, some cotton wool, and a Santa mask.

Critical Evaluation

Methodological limitations.

The study is often cited as evidence that phobias can develop through classical conditioning. However, critics have questioned whether conditioning actually occurred due to methodological flaws (Powell & Schmaltz, 2022).

- The study didn’t control for pseudoconditioning – the loud noise may have simply sensitized Albert to be fearful of any novel stimulus.

- It didn’t control for maturation – Albert was 11 months old initially, but the final test was at 12 months. Fears emerge naturally over time in infants, so maturation could account for Albert’s reactions.

- Albert’s reactions were inconsistent and the conditioned fear weak – he showed little distress to the rat in later tests, suggesting the conditioning was not very effective or durable.

Other methodological criticisms include:

- The researchers confounded their own experiment by conditioning Little Albert using the same neutral stimuli as the generalized stimuli (rabbit and dog).

- Some doubts exist as to whether or not this fear response was actually a phobia. When Albert was allowed to suck his thumb he showed no response whatsoever. This stimulus made him forget about the loud sound. It took more than 30 times for Watson to finally take Albert’s thumb out to observe a fear response.

- Other limitations included no control subject and no objective measurement of the fear response in Little Albert (e.g., the dependent variable was not operationalized).

- As this was an experiment of one individual, the findings cannot be generalized to others (e.g., low external validity). Albert had been reared in a hospital environment from birth and he was unusual as he had never been seen to show fear or rage by staff. Therefore, Little Albert may have responded differently in this experiment to how other young children may have, these findings will therefore be unique to him.

Theoretical Limitations

The cognitive approach criticizes the behavioral model as it does not take mental processes into account. They argue that the thinking processes that occur between a stimulus and a response are responsible for the feeling component of the response.

Ignoring the role of cognition is problematic, as irrational thinking appears to be a key feature of phobias.

Tomarken et al. (1989) presented a series of slides of snakes and neutral images (e.g., trees) to phobic and non-phobic participants. The phobics tended to overestimate the number of snake images presented.

The Little Albert Film

Powell and Schmaltz (2022) examined film footage of the study for evidence of conditioning. Clips showed Albert’s reactions during baseline and final transfer tests but not the conditioning trials. Analysis of his reactions did not provide strong evidence of conditioning:

- With the rat, Albert was initially indifferent and tried to crawl over it. He only cried when the rat was placed on his hand, likely just startled.

- With the rabbit, dog, fur coat, and mask, his reactions could be explained by being startled, innate wariness of looming objects, and other factors. Reactions were inconsistent and mild.

Overall, Albert’s reactions seem well within the normal range for an infant and can be readily explained without conditioning. The footage provides little evidence he acquired conditioned fear.

The belief the film shows conditioning may stem from:

- Viewer expectation – titles state conditioning occurred and viewers expect to see it.

- A tendency to perceive stronger evidence of conditioning than actually exists.

- An ongoing perception of behaviorism as manipulative, making Watson’s conditioning of a “helpless” infant seem plausible.

Rather than an accurate depiction, the film may have been a promotional device for Watson’s research. He hoped to use it to attract funding for a facility to closely study child development.

This could explain anomalies like the lack of conditioning trials and rearrangement of test clips.

Ethical Issues

The Little Albert Experiment was conducted in 1920 before ethical guidelines were established for human experiments in psychology. When judged by today’s standards, the study has several concerning ethical issues:

- There was no informed consent obtained from Albert’s parents. They were misled about the true aims of the research and did not know their child would be intentionally frightened. This represents a lack of transparency and a violation of personal autonomy.

- Intentionally inducing a fear response in an infant is concerning from a nonmaleficence perspective, as it involved deliberate psychological harm. The distress exhibited by Albert suggests the conditioning procedure was unethical by today’s standards.

- Watson and Rayner did not attempt to decondition or desensitize Albert to the fear response before the study ended abruptly. This meant they did not remove the psychological trauma they had induced, violating the principle of beneficence. Albert was left in a state of fear, which could have long-lasting developmental effects. Watson also published no follow-up data on Albert’s later emotional development.

Learning Check

- Summarise the process of classical conditioning in Watson and Raynor’s study.

- Explain how Watson and Raynor’s methodology is an improvement on Pavlov’s.

- What happened during the transfer sessions? What did this demonstrate?

- Why is Albert’s reaction to similar furry objects important for the interpretation of the study?

- Comment on the ethics of Watson and Raynor’s study.

- Support the claim that in ignoring the internal processes of the human mind, behaviorism reduces people to mindless automata (robots).

Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 64 , 605–614.

Digdon, N., Powell, R. A., & Harris, B. (2014). Little Albert’s alleged neurological persist impairment: Watson, Rayner, and historical revision. History of Psychology , 17 , 312–324.

Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. (2012). Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child. History of Psychology , 15, 1–34.

Griggs, R. A. (2015). Psychology’s lost boy: Will the real Little Albert please stand up? Teaching of Psychology, 4 2, 14–18.

Harris, B. (1979). Whatever happened to little Alb ert? . American Psychologist, 34 (2), 151.

Harris, B. (2011). Letting go of Little Albert: Disciplinary memory, history, and the uses of myth. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 47 , 1–17.

Harris, B. (2020). Journals, referees and gatekeepers in the dispute over Little Albert, 2009–2014. History of Psychology, 23 , 103–121.

Powell, R. A., Digdon, N., Harris, B., & Smithson, C. (2014). Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as “psychology’s lost boy.” American Psychologist, 69 , 600–611.

Powell, R. A., & Schmaltz, R. M. (2021). Did Little Albert actually acquire a conditioned fear of furry animals? What the film evidence tells us. History of Psychology , 24 (2), 164.

Todd, J. T. (1994). What psychology has to say about John B. Watson: Classical behaviorism in psychology textbooks. In J. T. Todd & E. K. Morris (Eds.), Modern perspectives on John B. Watson and classical behaviorism (pp. 74–107). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Tomarken, A. J., Mineka, S., & Cook, M. (1989). Fear-relevant selective associations and covariation bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98 (4), 381.

Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review, 20 , 158-177.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions . Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 (1), 1.

Watson, J. B., & Watson, R. R. (1928). Psychological care of infant and child . New York, NY: Norton.

Further Information

- Finding Little Albert

- Mystery solved: We now know what happened to Little Albert

- Psychology’s lost boy: Will the real Little Albert please stand up?

- Journals, referees, and gatekeepers in the dispute over Little Albert, 2009-2014

- Griggs, R. A. (2014). The continuing saga of Little Albert in introductory psychology textbooks. Teaching of Psychology, 41(4), 309-317.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Little Albert Experiment

A Closer Look at the Famous Case of Little Albert

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

A Closer Look

Classical conditioning, stimulus generalization, criticism and ethical issues, what happened to little albert.

The Little Albert experiment was a famous psychology experiment conducted by behaviorist John B. Watson and graduate student Rosalie Rayner. Previously, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov had conducted experiments demonstrating the conditioning process in dogs . Watson took Pavlov's research a step further by showing that emotional reactions could be classically conditioned in people.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

The participant in the experiment was a child that Watson and Rayner called "Albert B." but is known popularly today as Little Albert. When Little Albert was 9 months old, Watson and Rayner exposed him to a series of stimuli including a white rat, a rabbit, a monkey, masks, and burning newspapers and observed the boy's reactions.

The boy initially showed no fear of any of the objects he was shown.

The next time Albert was exposed to the rat, Watson made a loud noise by hitting a metal pipe with a hammer. Naturally, the child began to cry after hearing the loud noise. After repeatedly pairing the white rat with the loud noise, Albert began to expect a frightening noise whenever he saw the white rate. Soon, Albert began to cry simply after seeing the rat.

Watson and Rayner wrote: "The instant the rat was shown, the baby began to cry. Almost instantly he turned sharply to the left, fell over on [his] left side, raised himself on all fours and began to crawl away so rapidly that he was caught with difficulty before reaching the edge of the table."

The Little Albert experiment presents an example of how classical conditioning can be used to condition an emotional response.

- Neutral Stimulus : A stimulus that does not initially elicit a response (the white rat).

- Unconditioned Stimulus : A stimulus that elicits a reflexive response (the loud noise).

- Unconditioned Response : A natural reaction to a given stimulus (fear).

- Conditioned Stimulus : A stimulus that elicits a response after repeatedly being paired with an unconditioned stimulus (the white rat).

- Conditioned Response : The response caused by the conditioned stimulus (fear).

In addition to demonstrating that emotional responses could be conditioned in humans, Watson and Rayner also observed that stimulus generalization had occurred. After conditioning, Albert feared not just the white rat, but a wide variety of similar white objects as well. His fear included other furry objects including Raynor's fur coat and Watson wearing a Santa Claus beard.

While the experiment is one of psychology's most famous and is included in nearly every introductory psychology course , it is widely criticized for several reasons. First, the experimental design and process were not carefully constructed. Watson and Rayner did not develop an objective means to evaluate Albert's reactions, instead of relying on their own subjective interpretations.

The experiment also raises many ethical concerns. Little Albert was harmed during this experiment—he left the experiment with a previously nonexistent fear. By today's standards, the Little Albert experiment would not be allowed.

The question of what happened to Little Albert has long been one of psychology's mysteries. Before Watson and Rayner could attempt to "cure" Little Albert, he and his mother moved away. Some envisioned the boy growing into a man with a strange phobia of white, furry objects.

Recently, the true identity and fate of the boy known as Little Albert was discovered. As reported in American Psychologist , a seven-year search led by psychologist Hall P. Beck led to the discovery. After tracking down and locating the original experiments and the real identity of the boy's mother, it was suggested that Little Albert was actually a boy named Douglas Merritte.

The story does not have a happy ending, however. Douglas died at the age of six on May 10, 1925, of hydrocephalus (a build-up of fluid in his brain), which he had suffered from since birth. "Our search of seven years was longer than the little boy’s life," Beck wrote of the discovery.

In 2012, Beck and Alan J. Fridlund reported that Douglas was not the healthy, normal child Watson described in his 1920 experiment. They presented convincing evidence that Watson knew about and deliberately concealed the boy's neurological condition. These findings not only cast a shadow over Watson's legacy, but they also deepened the ethical and moral issues of this well-known experiment.

In 2014, doubt was cast over Beck and Fridlund's findings when researchers presented evidence that a boy by the name of William Barger was the real Little Albert. Barger was born on the same day as Merritte to a wet-nurse who worked at the same hospital as Merritte's mother. While his first name was William, he was known his entire life by his middle name, Albert.

While experts continue to debate the true identity of the boy at the center of Watson's experiment, there is little doubt that Little Albert left a lasting impression on the field of psychology.

Beck HP, Levinson S, Irons G. Finding Little Albert: a journey to John B. Watson's infant laboratory . Am Psychol. 2009;64(7):605-14. doi:10.1037/a0017234

Van Meurs B. Maladaptive Behavioral Consequences of Conditioned Fear-Generalization: A Pronounced, Yet Sparsely Studied, Feature of Anxiety Pathology . Behav Res Ther. 2014;57:29–37.

Fridlund AJ, Beck HP, Goldie WD, Irons G. Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child . Hist Psychol. 2012;15(4):302-27. doi:10.1037/a0026720

Powell RA. Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as "psychology's lost boy" . Am Psychol. 2014;69(6):600-11.

- Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 2009;64(7): 605-614.

- Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child. History of Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0026720; 2012.

- Watson, John B. & Rayner, Rosalie. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1-14.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

The Little Albert Experiment

The Little Albert Experiment is a world-famous study in the worlds of both behaviorism and general psychology. Its fame doesn’t just come from astounding findings. The story of the Little Albert experiment is mysterious, dramatic, dark, and controversial.

The Little Albert Experiment was a study conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner in 1920, where they conditioned a 9-month-old infant named "Albert" to fear a white rat by pairing it with a loud noise. Albert later showed fear responses to the rat and other similar stimuli.

The Little Albert Experiment is one of the most well-known and controversial psychological experiments of the 20th century. In 1920, American psychologist John B. Watson and his graduate student, Rosalie Rayner, carried out a study. Their goal was to explore the concept of classical conditioning. This theory proposes that individuals can learn to link an emotionless stimulus with an emotional reaction through repeated pairings.

For their experiment, Watson and Rayner selected a 9-month-old infant named "Albert" and exposed him to a series of stimuli, including a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, and various masks. Initially, Albert showed no fear of any of these objects. However, when the researchers presented the rat to him and simultaneously struck a steel bar with a hammer behind his head, Albert began to cry and show signs of fear. After several repetitions of this procedure, Albert began to show a fear response to the rat alone, even when the loud noise was not present.

The experiment was controversial because of its unethical nature. Albert could not provide informed consent, and his fear response was deliberately induced and not treated. Additionally, the experiment lacked scientific rigor regarding experimental design, sample size, and ethical considerations. Despite these criticisms, the Little Albert Experiment has had a significant impact on the field of psychology, particularly in the areas of behaviorism and classical conditioning. It has also raised important questions about the ethics of research involving human subjects and the need for informed consent and ethical guidelines in scientific studies.

Let's learn who was behind this experiment...

Who Was John B. Watson?

John B. Watson is pivotal in psychology's annals, marked by acclaim and controversy. Often hailed as the "Father of Behaviorism," his contributions extend beyond the well-known Little Albert study. At Johns Hopkins University, where much of his groundbreaking work was conducted, he delivered the seminal lecture "Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It."

This speech laid the foundation for behaviorism, emphasizing observable and measurable behavior over introspective methods, a paradigm shift in how psychological studies were approached. Watson's insistence on studying only observable behaviors positioned psychology more closely with the natural sciences, reshaping the discipline. Although he achieved significant milestones at Johns Hopkins, Watson's tenure there ended in 1920 under controversial circumstances, a story we'll delve into shortly.

Classical Conditioning

John B. Watson was certainly influential in classical conditioning, but many credit the genesis of this field to another notable psychologist: Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov's groundbreaking work with dogs laid the foundation for understanding classical conditioning, cementing his reputation in the annals of psychological research.

Classical conditioning is the process wherein an organism learns to associate one stimulus with another, leading to a specific response. Pavlov's experiment is a quintessential example of this. Initially, Pavlov observed that dogs would naturally salivate in response to food. During his experiment, he introduced a neutral stimulus, a bell, which did not produce any specific response from the dogs.

However, Pavlov began to ring the bell just before presenting the dogs with food. After several repetitions, the dogs began to associate the sound of the bell with the forthcoming food. Remarkably, even without food, ringing the bell alone led the dogs to salivate in anticipation. This involuntary response was not a behavior the dogs were intentionally trained to perform; instead, it was a reflexive reaction resulting from the association they had formed between the bell and the food.

Pavlov's research was not just about dogs and bells; its significance lies in the broader implications for understanding how associative learning works, influencing various fields from psychology to education and even marketing.

Who Was Little Albert?

John B. Watson took an idea from this theory. What if...

- ...all of our behaviors were the result of classical conditioning?

- ...we salivated only after connecting certain events with getting food?

- ...we only became afraid of touching a stove after we first put our hand on a hot stove and felt pain?

- ...fear was something we learned?

These are the questions that Watson attempted to answer with Little Albert.

Little Albert was a nine-month-old baby. His mother was a nurse at Johns Hopkins University, where the experiment was conducted. The baby’s name wasn’t really Albert - it was just a pseudonym that Watson used for the study. Due to the baby’s young age, Watson thought it would be a good idea to use him to test his hypothesis about developing fear.

Here’s how he conducted his experiment, now known as the “Little Albert Experiment.”

Watson exposed Little Albert to a handful of different stimuli. The stimuli included a white rat, a monkey, a hairy mask, a dog, and a seal-skin coat. When Watson first observed Little Albert, he did not fear any stimuli, including the white rat.

Then, Watson began the conditioning.

He would introduce the white rat back to Albert. Whenever Little Albert touched the rat, Watson would smash a hammer against a steel bar behind Albert’s head. Naturally, this stimulus scared Albert, and he would begin to cry. This was the “bell” of Pavlov’s experiment, but you can already see that this experiment is far more cruel.

Like Pavlov’s dogs, Little Albert became conditioned. Whenever he saw the rat, he would cry and try to move away from the rat. Throughout the study, he exhibited the same behaviors when exposed to “hairy” stimuli. This process is called stimulus generalization.

What Happened to Little Albert?

The Little Albert study was conducted in 1920. Shortly after the findings were published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, Johns Hopkins gave Watson a 50% raise . However, the rise (and Watson’s position at the University) did not last long. At the end of 1920, Watson was fired.

Why? At first, the University claimed it was due to an affair. Watson conducted the Little Albert experiment with his graduate student, Rosalie Rayner. They fell in love, despite Watson’s marriage to Mary Ickes. Ickes was a member of a prominent family in the area, upon the discovery of the affair, Watson and Rayner’s love letters were published in a newspaper. John Hopkins claimed to fire Watson for “indecency.”

Years later, rumors emerged that Watson wasn’t fired simply for his divorce. Watson and Rayner were allegedly conducting behaviorist experiments concerning sex. Those rumors included claims that Watson, a movie star handsome then, had even hooked devices up to him and Rayner while they engaged in intercourse. These claims seem false, but they appeared in psychology textbooks for years.

There is so much to this story that is wild and unusual! Upon hearing this story, one of the biggest questions people ask is, “What happened to Little Albert?”

The True Story of the Little Albert Experiment

Well, this element of the story isn’t without uncertainty and rumor. In 2012, researchers claimed to uncover the true story of Little Albert. The boy’s real name was apparently Douglas Merritte, who died at the age of seven. Merritt had a serious condition of built-up fluid in the brain. This story element was significant - Watson claimed Little Albert was a healthy and normal child. If Merritte were Little Albert, then Watson’s lies about the child’s health would ruin his legacy.

And it did until questions about Merritte began to arise. Further research puts another candidate into the ring: William Albert Barger. Barger was born on the same day in the same hospital as Merritte. His mother was a wet nurse in the same hospital where Watson worked. Barger’s story is much more hopeful than Merritte’s - he died at 87. Researchers met with his niece, who claimed that her uncle was particularly loving toward dogs but showed no evidence of fear that would have been developed through the famous study.

The mystery lives on.

Criticisms of the Little Albert Experiment

This story is fascinating, but psychologists note it is not the most ethical study.

The claims about Douglas Merritte are just one example of how the study could (and definitely did) cross the lines of ethics. If Little Albert was not the healthy boy that Watson claimed - well, there’s not much to say about the findings. Plus, the experiment was only conducted on one child. Follow-up research about the child and his conditioning never occurred (but this is partially due to the scandalous life of Watson and Rayner.)

Behaviorism, the school of psychology founded partly by this study, is not as “hot” as it was in the 1920s. But no one can deny the power and legacy of the Little Albert study. It is certainly one of the more important studies to know in psychology, both for its scandal and its place in studying learned behaviors.

Other Controversial Studies in Psychology

The Little Albert Experiment is one of the most notorious experiments in the history of psychology, but it's not the only one. Psychologists throughout the past few decades have used many unethical or questionable means to test out (or prove) their hypotheses. If you haven't heard about the following experiments, you can read about them on my page!

The Robbers Cave Experiment

Have you ever read Lord of the Flies? The book details the shocking and deadly story of boys stranded on a desert island. When the boys try to govern themselves, lines are drawn in the sand, and chaos ensues. Would that actually happen in real life?

Muzafer Sherif wanted to find out the answer. He put together the Robbers Cave Experiment, which is now one of the most controversial experiments in psychology history. The experiment involved putting together two teams of young men at a summer camp. Teams were put through trials to see how they would handle conflict within their groups and with "opposing" groups. The experiment's results led to the creation of the Realistic Conflict Theory.

The experiment did not turn out like Lord of the Flies, but the results are no longer valid. Why? Sherif highly manipulated the experiment. Gina Perry's The Lost Boys: Inside Muzafer Sherif's Robbers Cave Experiment details where Sherif went wrong and how the legacy of this experiment doesn't reflect what actually happened.

Read more about the Robber's Cave Experiment .

The Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment looked similar to the Robbers Cave Experiment. Psychologist Phillip Zimbardo brought together groups of young men to see how they would interact with each other. These participants, however, weren't at summer camp. Zimbardo asked his participants to either be a "prison guard" or "prisoner." He intended to observe the groups for seven days, but the experiment was cut short.

Why? Violence ensued. The experiment got so out of hand that Zimbardo ended it early for the safety of the participants. Years later, sources question whether his involvement in the experiment encouraged some violence between prison guards and prisoners. You can learn more about the Stanford Prison Experiment on Netflix or by reading our article.

The Milgram Experiment

Why do people do terrible things? Are they evil people, or do they just do as they are told? Stanley Milgram wanted to answer these questions and created the Milgram experiment . In this experiment, he asked participants to "shock" another participant (who was really just an actor receiving no shocks at all.) The shocks ranged in intensity, with some said to be hurtful or even fatal to the actor.

The results were shocking - no pun intended! However, the experiment remains controversial due to the lasting impacts it could have had on the participants. Gina Perry also wrote a book about this experiment - Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments.

The Monster Study

In the 1930s, Dr. Wendell Johnson was keen on exploring the origins and potential treatments for stuttering in children. To this end, he turned to orphans in Iowa, unknowingly involving them in his experiment. Not all the participating children had a stutter. Those without speech impediments were treated and criticized as if they did have one, while some with actual stuttering were either praised or criticized. Johnson's aim was to observe if these varied treatments would either alleviate or induce stuttering based on the feedback given.

Unfortunately, the experiment's outcomes painted a bleak picture. Not only did the genuine stutterers fail to overcome their speech issues, but some of the previously fluent-speaking orphans began to stutter after experiencing the negative treatment. Even by the standards of the 1930s, before the world was fully aware of the inhumane experiments conducted by groups like the Nazis, Johnson's methods were deemed excessively harsh and unethical.

Read more about the Monster Study here .

How Do Psychologists Conduct Ethical Experiments?

To ensure participants' well-being and prevent causing trauma, the field of psychology has undergone a significant evolution in its approach to research ethics. Historically, some early psychological experiments lacked adequate consideration for participants' rights or well-being, leading to trauma and ethical dilemmas. Notable events, such as the revelations of the Milgram obedience experiments and the Stanford prison experiment, brought to light the pressing need for ethical guidelines in research.

As a result, strict rules and guidelines for ethical experimentation were established. One fundamental principle is informed consent: participants must know that they are part of an experiment and should understand its nature. This means they must be informed about the procedures, potential risks, and their rights to withdraw without penalty. Participants consent to participate only after this detailed disclosure, which must be documented.

Moreover, creating ethics review boards became commonplace in research institutions, ensuring research proposals uphold ethical standards and protect participants' rights. If you are ever invited to participate in a research study, it's crucial to thoroughly understand its scope, ask questions, and ensure your rights are protected before giving consent. The journey to establish these ethical norms reflects the discipline's commitment to balancing scientific advancement with the dignity and well-being of its study subjects.

Related posts:

- John B. Watson (Psychologist Biography)

- The Psychology of Long Distance Relationships

- Behavioral Psychology

- Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI Test)

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Operant Conditioning

Observational Learning

Latent Learning

Experiential Learning

The Little Albert Study

Bobo Doll Experiment

Spacing Effect

Von Restorff Effect

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

image/svg+xml

The undergraduate neuroscience journal, ethical history: a contemporary examination of the little albert experiment, sehar bokhari.

Read more posts by this author.

Micaela Bartunek

Sehar bokhari , micaela bartunek.

In 1917, two curious researchers looking to examine the effects of fear conditioning began a study at Johns Hopkins University that would later become one of the most controversial experiments in the field. John Watson and Rosalie Rayner sought to test the limits of fear conditioning by recruiting a small child to partake in their study. The nine month old infant, known simply as "Little Albert B," was selected for his developmental and emotional stability at such a young age [1]. Watson's Little Albert study, taught in countless Introduction to Psychology courses, helps to further illustrate the idea of classical conditioning most notably explained by Ivan Pavlov. However, what many courses fail to explore is the issue of ethics behind experiments like Watson's, and the effects studies like it have on the subsequent behavior and development of their participants. As a result of studies such as Watson's, universities have created Institutional Review Boards, ethical boards that seek to ensure humane practices and protect human life while concurrently advancing knowledge in research. Understanding Watson's Little Albert study not only illuminates an interesting aspect of behavioral psychology, but also brings up interesting questions about research ethics in studies involving human participants.

The Mechanics of Fear Conditioning

Watson's research centered around Albert's interactions with a variety of animals including white rabbits and mice. Watson and Rayner noted that initially, Albert's behavior towards these animals was curious and playful. To condition a fearful response in the child, Watson exposed Albert to each animal while simultaneously producing a loud, frightening noise by slamming a large hammer into a long metal pipe. At first, Albert reacted by withdrawing from the animal. Then his lips began to tremble. Upon the third blow, Albert began to cry and shake violently. It was the first time Albert exhibited any sort of fear repsonse within the study. It certainly wouldn't be the last [1].

Days later, Albert was presented with the same animals as previously described, only this time without any noise. Albert immediately withdrew from them, now fearing the animals themselves. Watson and Rayner had successfully taught a nine-month old child to fear something he initially loved, through interaction and classical conditioning [1].

Fear Generalization

As the study progressed, Watson questioned whether Albert's fear conditioning could be applied to other objects and animals similar in nature to a white rabbit. Albert was presented with a wool coat, a small dog, and even a Santa Claus mask with a beard fashioned out of cotton balls. Albert now exhibited signs of generalization–a phenomenon in which the original stimulus is not the only stimulus that elicits fear from the participant. In Albert's case, objects that looked visually similar to the objects he was originally conditioned to fear also elicited the same response–despite the fact that these objects were not conditioned in the first phase of the study.

Watson and Rayner concluded that Albert's conditioned fear response persisted for approximately one month. As Albert's fears spread, however, his mother abruptly removed him from the study. Because of his immediate and sudden departure, Watson and Rayner were never able to reverse the effects of Albert's fear conditioning through a process known as desensitization [1].

Desensitization utilizes a series of relaxation and imagination techniques in order to reverse the effects of fear conditioning [2]. If properly performed, extinction occurs when the subject is repeatedly exposed to the conditioned stimulus without the fear-conditioning stimulus--in Albert's case, the loud sound. Over time, the participant's fear fades due to repeated exposure to the conditioned stimulus without the negative consequence. The participant then substitutes the initial fear with that of a normal response [3]. However, new research on desensitization raises questions as to whether it fully reverses the effects of fear conditioning. Research suggests that even if desensitization works, it may not necessarily last, so the participant runs the risk of relapse [9]. Unfortunately, Albert was never even exposed to these methods, and as such, many have wondered what effects this study and lack of desensitization may have had throughout Albert's lifetime.

The Mystery of a Lifetime

Johns Hopkins University became the focus of the search for Albert. Watson left behind little evidence to suggest Little Albert's whereabouts following the study, though he did leave Albert's estimated date of birth, age at the same time of their research, and a grain film that documented the entirety of the study. One researcher, Hall Beck from Appalachian State University in North Carolina, was the first to provide an answer.

Beck used Albert's history to track down, a nurse at Johns Hopkins University's Hospital that he suspected to be Albert's mother. Beck discovered that the nurse had a son named Douglas Merrite who fit the proper description of Albert during the time of the study [4]. Merritte pased away at age six due to hydrocephamus that initiate the fear response. These responses are regulated by the nervous system which creates a startle response and simultaneously increase a person's heart rate, respiration rate, or blood pressure [6].

The human brain is a complicated system of neural structures and pathways, some of the which serve as conduits to fear and learning. These intricate systems in the brain can cause even nine month old children to fear for their lives. Even with desensitization techniques, it is still uncertain just how these sorts of experiments affect human beings. Today, Institutional Review Boards closely monitor modern studies to avoid repeating what happened to Little Albert and ensure that subjects are protected both mentally and physically.

IRBS & Ethics

As with many controversial experiments like Watson's, the question of the ethical boundaries in research is brought to the forefront. Is it morally acceptable to conduct an experiment on an infant? Many suggest that experimenters should find a strict balance between the importance of protecting those who participate in experiments, especially infants, and scientific advancement [7]. Regulations boards, known as Institutional Review Boards (or IRBs) now exist within federally funded research universities in order to protect such balances within proposed research studies [8]. Research proposals must explicitly state and explain the risk and benefits to participants within the study, as well as give participants the right to withdraw at any time if they wish to do so. Proper debriefing following experiments must also take place, ensuring that subjects are fully aware of the purpose of the study and how the experiments will be obtaining their results [2].

Perhaps as time goes on and new findings emerge, IRBs and researchers alike can learn to identify the line beyond which an experiment goes too far. Even if a study is considered ethical and approved by an IRB, it may still be controversial. Examining studies such as Little Albert's allow IRBs to recognize moral dilemmas and adapt their procedures regarding experimental proposals in order to ensure that these ethical complications do not reoccur. It may not be easy, but when an experiment builds itself around a strong ethical foundation, the results of the study, as well as the study itself, are preserved in honesty and integrity. As Dan McArthur, a Professor of Philosophy at York University, puts it, when we protect scientific integrity and respect our participants, "good ethics can sometimes mean better results" [10].

- Classics in the History of Psychology. (n.d.). Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm

- Systematic Desensitization | Simply Psychology. (n.d.). Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://www.simplypsychology.org/Systematic-Desensitisation.html

- Hermans, D., Graske, M., Mineka, S., & Lovibond, P. (2006). Extinction in Human Fear Conditioning. Retrieved November 19, 2015, from https://lirias.kuleuven.be/bitstream/123456789/125886/1/24.pdf

- The Search for Psychology's Lost Boy. (2014, June 1). Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://chronicle.com/interactives/littlealbert

- Limbic System: Amygdala (Section 4, Chapter 6) Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences | Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy - The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. (n.d.). Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://neuroscience.uth.tmc.edu/S4/chapter06.html

- Maren, S. (n.d.). Neurobiology of Pavlovian Fear Conditioning - Annual Review of Neuroscience. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://www.annualreviews.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897

- Diekema, D. (n.d.). Ethical Issues In Research Involving Infants. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://www.seminperinat.com/article/S0146-0005(09)00060-3/fulltext

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, A. (1995). Ethics in Psychological Research. In Research in psychology: Methods and design (7th ed., pp. 41-44). New York: Wiley.

- Vervliet, B., Craske, M. & Hermans, D. (n.d.). Fear Extinction and Relapse: State of the Art. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://www.annualreviews.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-clinp-sy-050212-185542

- Mcarthur, D. (2009). Good ethics can sometimes mean between science: Research ethics and the milgram experiments. Science and Engineering Ethics, 15(1), 69-79. doi: http://dx.doi.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/10.1007/S11948-008-9083-4

Psychologized

Psychology is Everywhere...

The Little Albert Experiment

Little Albert was the fictitious name given to an unknown child who was subjected to an experiment in classical conditioning by John Watson and Rosalie Raynor at John Hopkins University in the USA, in 1919. By today’s standards in psychology, the experiment would not be allowed because of ethical violations, namely the lack of informed consent from the subject or his parents and the prime principle of “do no harm”. The experimental method contained significant weaknesses including failure to develop adequate control conditions and the fact that there was only one subject. Despite the many short comings of the work, the results of the experiment are widely quoted in a range of psychology texts and also were a starting point for understanding phobias and the development of treatments for them.

What happened to Little Albert as he was known is unknown and several psychologists have tried in vain to definitively answer the question of: “what happened to Little Albert?”

What is classical conditioning?

Classical Conditioning Explained

Classical conditioning is a type of behaviourism first demonstrated by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in the 1890s.Through a series of experiments he demonstrated that dogs which normally salivated when presented with food could be conditioned to salivate in response to any stimulus in the absence of the original stimulus, food. He rang a bell every time a dog was about to be fed, and after a period of time the dog would salivate to the sound of the bell irrespective of food being presented.

What did Watson do to Little Albert?

Many people have illogical fears of animals. While it is logical to be frightened of a predator with the power to kill you, being afraid of a spider, a mouse or even cats and most dogs is not. To those of us who don’t suffer from phobias it is the funniest thing in the world to see a person standing on a stool, screaming because of a mouse. Phobias however are real, and for some people quite limiting and potentially damaging. Imagine suffering from agoraphobia – fear of open spaces or even being afraid of going to the dentist to the extent that your health suffered.

Now, while we know now that phobias can be learned from watching others who have a fear, for example our mother being afraid of spiders, known as social learning, Watson used the tools and knowledge he had available to him to investigate the potential causes of them ultimately, one supposes, to develop treatments for phobias.

John Watson endeavoured to repeat classical conditioning on a young emotionally stable child, with the objective of inducing phobias in the child. He was interested in trying to understand how children become afraid of animals.

Harris (1979) suggested: ‘Watson hypothesized that although infants do not naturally fear animals, if “one animal succeeds in arousing fear, any moving furry animal thereafter may arouse it”

Albert was 9 months old and taken from a hospital, subjected to a series of baseline tests and then a series of experiences to ‘condition’ him. Watson filmed his study on Little Albert and the recordings are accessible on Youtube.com.

A series of unethical experiments was conducted with Little Albert

Watson started by introducing Albert to a number of furry animals, including a dog, a rabbit and most importantly a white rat. Watson then made loud, unpleasant noises by clanging a metal bar with a hammer. The noise distressed Albert. Watson then paired the loud noise with the presentation of the rat to Albert. He repeated this many times. Very quickly Albert was conditioned to expect the frightening noise whenever the white rat was presented to him. Very soon the white rate alone could induce a fear response in Albert. What was interesting was that without need for further conditioning the fear was generalised to other animals and situations including a dog, rabbit and a white furry mask worn by Watson himself.

Watson and Raynor who knew all along the timescale by when Albert had to be returned to his mother, gave him back without informing her of the activities and conditioning that they had inflicted on Albert, and most worryingly not taking the time to counter condition or ‘curing’ him of the phobia they had induced.

What were the problems with this the way this study was done?

Both the American Psychological Association (APA) and the British Psychological Society (BPS) have well developed codes of ethics which any practicing psychologists have to adhere to. In addition, all places of higher learning and research have ethical committees to which research proposals have to be submitted for consideration. The core concern is to focus on the quality of research, the professional competence of the researchers and of greatest importance, the welfare of human and animal subjects. At the time of Watson and Raynor’s work, there were no such guidelines and committee. While to some extent, it is wrong to measure historical research by modern-day standards, this experiment is almost a case study in unethical research. The experiment broke the cardinal ethical rules for psychological research. Those being:

- Do no harm . Psychologists have to reduce or eliminate the potential that taking part in a study may cause harm to a participant during and afterwards. Little Albert was harmed during and would potentially have suffered life-long harm as a result.

- The participants’ right to withdraw. Nowadays, if you are involved as participant in any psychological or medical study you are given the right that you can withdraw at any stage during the study without consequence to you. Albert and his mother were given no-such rights.

- The principle of informed consent. Subjects have to be given as much information about the study as possible before the study begins so that they can make a decision about participating based on knowledge. If the research is such that giving information before the study may affect the outcome then an alternative is a thorough debrief at its conclusion. Neither of these conditions was satisfied by Watson’s treatment of Albert.

- Professional competence of the researcher. While it may seem presumptive to question the behaviour of the father of “behavioural psychology”, the method used in this study was not particularly good psychology. There was only one subject and the experiment lacks any form of control. Such criticism however, is a little post hoc since research in psychology at that time was in its infancy.

Besides the ethical issues with the experiment, as can be seen from the recordings, the environment was not controlled, the animals changed, and several appeared themselves to be in distress. The final act of Watson applying a mask was presented very closely to Albert, something that potentially would cause any child distress.

Watson could have ‘cured’ Albert of the phobia he had induced using a process known as systematic desensitisation but chose not to as he and Raynor wanted to continue with the experiment until the Albert’s mother came to collect him.

Watch a Recap of this experiment in this video:

Harris B (1979): Whatever happened to Little Albert ? American Psychologist, February 1979, pp 151-160

Code of Ethics:

http://www.bps.org.uk/what-we-do/ethics-standards/ethics-standards

About Alexander Burgemeester

2 Responses to “The Little Albert Experiment”

Read below or add a comment...

what are the laws of classical conditioning in this experiment

Wow, this entire article is full of inaccuracies. Firstly, they didn’t begin the conditioning experiments on Albert until he was 11 months and 3 days old. While the first few original reactions with the different animals did not need further conditioning, the steel rod was struck several times throughout the experiment to reinstate the fear response with the stimuli. Also, it is only speculated that Albert’s mother was unaware that these experiments were going on. You mention that the mask in which Watson wears at the ending of the video would distress any child, but before beginning the experiments, Watson and his crew tested several different stimuli on Albert and marked any emotional responses. The masks were part of this test and did not originally trigger a response. A fear response was present after Albert was conditioned to fear the white rat and things that were visually similar. The mask had white hair attached at the top. He had a similiar response to a paper bag of white cotton wool. Lastly, the fact that your entire article is written with a secondary source (written in 1979 no less) as your only source beside the video, and never even refers to Watson’s original journal publication (which is available for free online at http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm ) is even more of a reason to find this article flawed.

Leave A Comment... Cancel reply

Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science pp 4603–4606 Cite as

Little Albert

- Polyxeni Georgiadou 3

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

248 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Download reference work entry PDF

Conditioned emotional reactions ; Experiment ; Learning ; Watson

John Watson’s experiment on children’s conditioned emotional reactions

Introduction

In 1919, upon Watson’s return from the army, he decided to pursue research, along with Rosalie Rayner, on children’s emotional response and development based on conditioning processes. The first and only study that Watson and Rayner performed on this topic was the study with Albert B. or, most known, as Little Albert, at the laboratory of a hospital. This experiment became one of the most frequently cited in psychology books and magazines and is described as “one of the classic studies of twentieth-century psychology” (Todd 1994 , p. 82).

The Conditions Surrounding the Experiment

Watson’s academic career was built on examining animal learning. He was applying Pavlov’s principles of classical conditioning, where innate bodily reflexes are conditioned with new stimuli to create new learning by association. Thus, conditioning causes events or stimuli to be associated in time, and learning takes place from the associated (simultaneous) arrangement of stimuli and responses. Watson concluded that the trial ends when the animal chooses the correct response. The more often a response brings positive results, the higher the probability that it will be repeated by the animal (the law of frequency). Additionally, the animal will tend to repeat the most recent successful response (law of recency) (Hergenhahn 2000 ).

Upon his return from the army (1918) and before his abandonment of his academic career (1920), he decided to turn his attention to research on humans and especially on how conditioning processes influence human development. While teaching at Johns Hopkins University, he arranged to use a laboratory at Phipps Clinic (Moore 2017 ). Adjacent to Phipps Clinic was the Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children, a hospital connected to the Phipps Clinic with a corridor (Watson and Rayner 2000 ).

Watson’s interests centered on emotions; he considered emotions as mere physical responses, and he wanted to prove that emotional responses could be conditioned. For some (Rilling 2000 ) this was Watson’s major contribution to learning theory and an explanation of phobic reactions through behaviorism. He believed that, since birth, infant humans have three unlearned emotional reactions: fear, rage, and love. Fear is evoked by only two stimuli that are unconditioned: a sudden noise and the loss of physical support but those fear-provoking stimuli are learned. Fear in infants can be observed in crying, breathing rapidly, closing their eyes, or jumping suddenly (Watson and Rayner 2000 ).

The Experiment

It is estimated that in early December 1919, Watson and Rosalie Rayner, his research assistant and later his wife, conducted a series of baseline trials. They chose only one child, Albert B., a healthy, well-developed, stolid, and unemotional child who cried rarely. He was raised almost from birth at the “Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children” with his mother who was a wet nurse in the home. He had a normal life, and one of the main reasons he was chosen among other infants was that it was believed that the experiment could do relatively little harm to him. Different phases of the experiment were filmed. The experiment was conducted, with the approval of Albert’s mother, in a small, well-lighted dark room, and Albert was placed in a mattress, above a table (Watson and Rayner 2000 ).

Albert was assessed neurologically at around 9 months, in order to determine whether stimuli other than sharp noises and sudden removal of support can cause fear reactions. Thus, Albert was confronted suddenly with “a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, masks with and without hair, cotton wool, etc.” (Watson and Rayner 2000 , p. 313); he showed no fear, at any time. Independently of the above observations, the experimenters tested whether the child would react to loud sounds by striking with a hammer a suspended steel bar three-fourths of an inch thick and 4 ft long; he reacted with fear and crying. Upon receiving the above results, Watson and Rayner wanted to examine the following: (a) if they could condition fear of an animal under the condition of visual presentation of the animal and simultaneously striking a steel bar, (b) if the conditioned emotional response established can be transferred to other animals or objects, (c) if time has an effect on the conditioned response, and (d) if they can devise methods for the removal of such conditioned emotional responses (Watson and Rayner 2000 ).

The experimenters had no other interaction with Albert until he became 11 months and 3 days old. He was presented with a white rat, and as he was reaching with his left hand for the rat, the experimenters were striking hard the steel bar behind his head. In the first trial, Albert fell forward and buried his face in the mattress. In the second trial, he jumped violently and began to whimper. A week later, he was exposed to the rat without the sound. Initially he did not reach for it, and when he did start to approach it with his hand, he withdrew it before contact, which indicated that the two joint stimulations of the first week were still effective. Albert had positive reactions to other objects by picking them up. In the next trials of the same day, the rat was presented in association with the sound, and Albert’s reaction progressed from sudden bounce to turning away from the rat, then cringing his face and withdrawing his body to the left, and to falling to the right side and beginning to whimper and eventually violently crying. Watson concluded that the conditioned fear response was completed (Moore 2017 ; Watson and Rayner 2000 ).

When Albert was 11 months and 15 days old, they wanted to examine whether the conditioned emotional response can be transferred for another object. Thus, they first presented Albert with different objects, and they noticed that he was comfortably playing with them that indicated that there was no transfer to other objects. When the rat presented alone, the child immediately began to crawl away from it and whimpered. Then, they presented a rabbit, and Albert had the same reactions as with the rat. When a dog was presented, similar reactions were elicited but not from the beginning of the interaction. He had similar reactions to a fur coat, cotton wool, a Santa Claus mask, and Watson’s hair but not with other people’s hair. Intermediate of the presentations with the aforementioned objects, Albert was presented with blocks, neutral objects that he happily played with throughout the experiment.

A week later, the rat was presented alone to Albert; he was cautious and was following it with his eyes, but he did not cry. As the rod was struck, his reaction was violent initially, but on the next two presentations of the rat alone, his reactions were as strong as before but without crying (i.e., crawling away from it). The experimenters also wanted to present the rabbit and the dog consecutively in connection with the sound of the steel bar and wanted to test whether Albert’s reactions were similar in two different contexts, that is, the usual laboratory or a large, well-lighted lecture room. They found that the reactions were similar although less violent in the second room. From this phase of the experiment, they concluded that emotional transfer does take place (Watson and Rayner 2000 ).

At 1 year and 21 days old, upon Albert’s exposure to the phobic objects, the conditioned emotional reactions by transfer persisted, although with less intensity. In the last phase of the test, they observed that when the child was under stress, he would thrust his thumb into his mouth, and he would become impervious to the fear earlier produced by the different stimuli. They suggested that the love stimulation one seeks under the influence of harmful situations persists throughout life and could be described as a “compensatory” (and possibly conditioned) device, instead of the “expression of an original pleasure-seeking principle” as described by Freud (Watson and Rayner 2000 , p. 316) Watson and Rayner did not have the chance to test for the effect of time on the symptoms or whether they could remove them because Albert moved out of the hospital soon after the last trial, but they contended that the symptoms would persist and modify personality throughout life.

Who Was Albert B?

Different researchers tried to discover the true identity of Little Albert. Some researchers (Beck et al. 2009 ) supported that his real name was Douglas Merritte, son of Arvilla Merritte who was working at the hospital at the time as a wet nurse. Douglas contracted meningitis from his aunt, developed hydrocephalus, and died from it at the age of 6. Fridlund, Beck, Goldie, and Irons (2012, as cited in Digdona et al. 2014 ) reported findings that Douglas had been neurologically impaired as early as the time the experiment was conducted. The general reactions from the above were that, if this was the case, Watson and Rayner’s findings were challenged (Digdona et al. 2014 ). Other researchers (Digdona et al. 2014 ) concluded that the child was actually Albert Barger son of a 16-year-old mother by the name of Pearl Barger who was also a wet nurse working at the time at the hospital. One of the points for the defense of this opinion is that Watson typically used real names or initials of the infants he worked with; thus Albert B would be Albert Barger.

Ethical Concerns

Throughout the years, different publications challenged Watson’s ethical standards, and some characterize Little Albert as a “victim” (Todd 1994 , p. 85). Watson himself reported his hesitation in inflicting fear reactions to a child. His defense in continuing with the experiment was that Albert was a strong, composed, unemotional child. Additionally, “such attachments would arise anyway as soon as the child left the sheltered environment of the nursery” (Watson and Rayner, 2000 p. 314). At the time, the Little Albert experiment did not raise serious ethical questions, although Watson warned his readers that for the replication of the experiment, considerable training was needed (Todd 1994 ).

John Watson and Rosalie Rayner planned to examine conditioned emotional responses on children. Specifically, they wanted to test whether they can condition fear reactions of different animals and objects to a 9-month-old healthy infant. The results confirmed most of the hypotheses of the experimenters but stirred up different reactions by researchers and the press for the ethical repercussions of conducting such a study to a child especially without extinguishing the symptoms evoked on the child.

Despite the questionable ethics and its methodological limitations, the Little Albert study (in reprint on Watson & Rayner, 2000 ) on conditioning became a “landmark” in behavioral psychology and changed the way we examine behavior and the way we practice. Furthermore, the results on fear acquisition and generalization initiated the development of treatments for phobias (Field and Nightingale 2009; Wolpe 1958 as cited in Beck et al. 2009 ) and other behavioral problems (Masters and Rimm 1987; Rachman 1997 as cited in Beck et al. 2009 ).

Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert. A journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 64 (7), 605–614.

Article Google Scholar

Digdona, N., Powell, R. A., & Smithson, C. (2014). Watson’s alleged Little Albert scandal: Historical breakthrough or new Watson myth ? Revista de Historia de la Psicologia, 35 (1), 47–60.

Google Scholar

Hergenhahn, B. R. (2000). Introduction to the history of psychology . Belmont: Wadsworth.

Moore, J. (2017). John B. Watson’s classical S-R Behaviorism. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 38 (1), 1–34.

Rilling, M. (2000). How the challenge of explaining learning influenced the origins and development of John B. Watson’s behaviorism. American Journal of Psychology, 113 (2), 275–301.

Todd, J. T. (1994). What psychology has to say about John B. Watson: Classical behaviorism in psychology textbooks, 1920–1989. In J. T. Todd & E. K. Morris (Eds.), Modern perspectives on John B. Watson and classical behaviorism , Contributions in psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 75–107). Westport: Greenwood Press/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (2000). Conditioned emotional reactions. American Psychologist, 55 (3), 313–317, a reprint of Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. R. (1920). Journal of Experimental Psychology , 3 , 1–14.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Polyxeni Georgiadou

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Polyxeni Georgiadou .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd K Shackelford

Viviana A Weekes-Shackelford

Section Editor information

Menelaos Apostolou

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Georgiadou, P. (2021). Little Albert. In: Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1046

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1046

Published : 22 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-19649-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-19650-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Search site

What is the little albert experiment in behavioral science, what is the little albert experiment.

Definition: The Little Albert Experiment was a psychological study conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner in 1920. The experiment aimed to demonstrate classical conditioning, a form of associative learning, in humans. The researchers sought to show that a child could be conditioned to develop a fear response to a previously neutral stimulus.

What are findings of The Little Albert Experiment?

Conditioned fear response.

The first finding of the Little Albert Experiment was that a fear response could be induced in a previously unafraid infant through classical conditioning. The infant, referred to as “Little Albert,” was exposed to a loud noise (the unconditioned stimulus) whenever he reached for a white rat (the neutral stimulus), eventually causing him to associate the rat with the noise and develop a fear response to the rat (the conditioned stimulus).

Generalization

The 2nd finding of the Little Albert Experiment was that the conditioned fear response could generalize to other stimuli that shared similar characteristics with the original conditioned stimulus. Little Albert’s fear of the white rat extended to other white, furry objects, such as a rabbit, a dog, and a fur coat.

Emotional Reactions

The 3rd finding of the Little Albert Experiment was that emotional reactions could be conditioned, providing evidence for Watson’s behaviorist theory, which posited that emotions are learned behaviors that can be manipulated through conditioning.

Examples of The Little Albert Experiment

Original little albert study.

The first example of the Little Albert Experiment was the original study conducted by Watson and Rayner, in which they successfully conditioned an infant to develop a fear response to a white rat by pairing the rat with a loud noise.

Subsequent Research on Classical Conditioning

The 2nd example of the Little Albert Experiment is its lasting impact on subsequent research in classical conditioning, influencing the development of studies on conditioned emotional responses and phobias, as well as treatments for phobias and other anxiety disorders, such as systematic desensitization and exposure therapy.

Shortcomings and Criticisms of The Little Albert Experiment

Ethical concerns.

The first criticism of the Little Albert Experiment was its ethical implications. Deliberately inducing fear in an infant without consent and without attempts to reverse the conditioning is considered unethical by today’s standards and would not be permitted under current research guidelines.

Methodological Issues

The 2nd criticism of the Little Albert Experiment was methodological in nature. The small sample size (only one infant), lack of control group, and potential confounding variables limit the generalizability and validity of the study’s findings.

Incomplete Data

The 3rd criticism of the Little Albert Experiment was the incomplete data and lack of follow-up. The experiment did not address the long-term effects of the conditioning or explore possible methods of reversing the learned fear response, leaving many unanswered questions regarding the persistence and malleability of conditioned emotional responses.

Related Behavioral Science Terms

Belief perseverance, crystallized intelligence, extraneous variable, representative sample, factor analysis, egocentrism, stimulus generalization, reciprocal determinism, divergent thinking, convergent thinking, social environment, decision making, related articles.

Default Nudges: Fake Behavior Change

Here’s Why the Loop is Stupid

How behavioral science can be used to build the perfect brand

The Death Of Behavioral Economics

What is Psychology?

Answers to Your Psychology Questions

The Little Albert Experiment (Summary)

The Little Albert Experiment is a famous psychology study on the effects of behavioral conditioning. Conducted by John B. Watson and his assistant, graduate student, Rosalie Raynor, the experiment used the results from research carried out on dogs by Ivan Pavlov — and took it one step further.

What was the Little Albert Experiment?

Watson used Pavlov’s research and designed an experiment to see if emotional responses could be classically conditioned in humans.

Watson wanted to see if the fearful reaction he had previously observed when children were exposed to loud noises was something that could be conditioned in response to an unrelated stimulus; in other words, something the child would not normally fear.

Who Was Little Albert?

Little Albert was the subject of Watson’s experiment. Many of the facts of the experiment are somewhat sketchy and over the years there have been conflicting reports as to whom Little Albert actually was, but it is generally believed that he was a 9 month old baby boy born and raised in a home for Invalid Children.