Martes, Setyembre 17, 2013

- MISFORTUNES IN MADRID (1890-91)

6 (mga) komento:

The blog all in all was gramatically correct (no worries about that). I think it's also very informative. Here are the points of improvement on the other hand: As a fellow blogger, I believe that the presentation of information is prime to the actual matter itself. I think the format such as the font, font size, theme and all could still be improved (if this is not the required format). There are so many beautiful things you want to say that it looks to crowded making the readers feel discouraged about reading it. Also, I hope you could give it more of a personal touch because it sounds too scholarly, I hope you would write it in such a way that you want your readers to feel close to you is all I want to say.

Can you please give me a reaction about this. Urgent

Maybe you could do a timeline with pictures (with captions) or videos so that it won't be too wordy to look at.

This is very helpful. Thanks :)

Salamat ������

- Blog Archives

- RIZAL’S VISIT TO THE UNITED STATES (1888) · April 28, 1888- the steamer Belgic, with Rizal on board, docked at San Francisco on Saturday morning · May 4, 1888- Friday afternoon, th...

- RIZAL’S GRAND TOUR OF EUROPE WITH VIOLA (1887) · May 11, 1887- Rizal and Viola left Berlin by train · Dresden- one of the best cities in Germany · Prometheus Bound-painting wherein Riza...

- IN SUNNY SPAIN (1882-1885) -After finishing the 4th year of the medical course in the University of Santo Tomas, Rizal decided to complete his studies in Spain -Asid...

Mga Kabuuang Pageview

Blog archive.

- SECOND HOMECOMING AND THE LIGA FILIPINA

- DECISION TO RETURN TO MANILA

- WRITINGS IN HONG KONG

- BORNEO COLONIZATION PROJECT

- OPHTHALMIC SURGEON IN HONG KONG (1891-1892)

- COMPARISON BETWEEN NOLI ME TANGERE and EL FILIBUST...

- EL FILIBUSTERISMO PUBLISHED IN GHENT (1891)

- BIARRITZ VACATION

- IN BELGIAN BRUSSELS (1890)

- ANNOTATED EDITION OF MORGA PUBLISHED

- RIZAL’S SECOND SOJOURN IN PARIS AND THE UNIVERSAL ...

- WRITINGS IN LONDON

- RIZAL AND THE LA SOLIDARIDAD NEWSPAPER

- RIZAL’S VISIT TO THE UNITED STATES (1888)

- ROMANTIC INTERLUDE IN JAPAN (1888)

- IN HONGKONG AND MACAO (1888)

- STORM OVER THE NOLI ME TANGERE

- FIRST HOMECOMING (1887-1888)

- RIZAL IN ITALY

- RIZAL’S GRAND TOUR OF EUROPE WITH VIOLA (1887)

- NOLI ME TANGERE PUBLISHED IN BERLIN (1887)

- PARIS TO BERLIN (1885-1887)

- FIRST VISIT TO PARIS (1883)

- LIFE IN MADRID

- IN SUNNY SPAIN (1882-1885)

- ► Hulyo (6)

Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture

Madrid on the Move: Feeling Modern and Visually Aware in the Nineteenth Century by Vanesa Rodríguez-Galindo

M. Elizabeth Boone Professor, History of Art, Design, and Visual Culture University of Alberta Email the author: betsy.boone[at]ualberta.ca

Citation: M. Elizabeth Boone, book review of Madrid on the Move: Feeling Modern and Visually Aware in the Nineteenth Century by Vanesa Rodríguez-Galindo, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 3 (Autumn 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.3.14 .

Vanesa Rodríguez-Galindo, Madrid on the Move: Feeling Modern and Visually Aware in the Nineteenth Century . Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021. 312 pp.; 70 b&w illus.; notes; bibliography; index. £85.00 (hardcover) ISBN: 978–1526144362

The title of the new book by Vanesa Rodríguez-Galindo, Madrid on the Move: Feeling Modern and Visually Aware in the Nineteenth Century , aptly points to a number of key issues for historians of art and visual culture in the late nineteenth century: mobility, modernity, and visuality. In this thoroughly researched and well-argued text, Rodríguez-Galindo uses her deep knowledge of the illustrated press to decenter our thinking about modernity and encourage us to look at the capital city of Madrid. In this regard, Madrid on the Move seeks to deepen recent attempts by scholars to understand the modern in parts of the world beyond Paris. Eschewing the use of adjectives that qualify modernity or expand it from the singular to multiple modernities, Rodríguez-Galindo “aims to strip the concept of modernity of the historiographic baggage that hinders productive thinking about cities that lie outside the canonical narrative of modernity, and, ultimately, aims to dislocate the concept altogether” (4). Spain is a particularly exciting place from which to promote this goal as the cultural intellectuals who sought to explain Spain’s loss of empire after the War of 1898 placed much of the blame on what they considered their country’s failure to modernize.

Rodríguez-Galindo signals her transnational approach to the subject of modern print culture in the introduction, which begins with the heated discussion engendered in Spain by the publication in 1871 by the New York journal Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of a view of Madrid’s main square, the Puerta del Sol. The editor of Madrid’s main illustrated journal, La Ilustración Española y Americana , criticized this image and its accompanying text for failing to convey the modernity of the city and casting the square and its inhabitants as out-dated and unsophisticated. She continues the introduction by providing the reader with a dense overview of the themes to be explored in the book: the unstable nature of the words and language used to define the modern; the power of images and their relationship to text; the prevalence in Spain of genre painting, or more precisely costumbrismo , which is usually defined as the painting of people’s customs; and “the slipperiness of the concept of modernity” (6). Rodríguez-Galindo is determined to reframe modernity not as a rupture, but as a negotiation, between the past and the present and between the local and the global. Tradition, she points out, does not have to be expunged to be modern. She is also eager to explore the ways that seeing, representing, and responding to the city were mutually constitutive processes. The evidence for these assertions is drawn from illustrated newspapers and satirical reviews published in Madrid between the 1860s and the mid-1890s.

Chapter 1, “Seeing the City,” considers how nineteenth-century madrileños (residents of Madrid) both saw the city and saw in the city. Arguing that how we can and cannot see is a question that produces self-reflexivity, Rodríguez-Galindo introduces several images—drawings and photographs—of blind men navigating the streets. She also provides an overview of the burgeoning illustrated press, new press laws that loosened restrictions on publishers in Spain, and the interplay of words and images as vehicles of visual communication. Her analysis of an advertising page from the newspaper La Iberia deftly demonstrates how British, French, Cuban, and Spanish businesses and products could jostle one another for the reader’s attention. Both words and images provide information to aid the imagination, and just as text and image interact with one another, so too do photographs and drawings. Several of the images she includes, such as an illustration depicting a woman viewing an installation mounted by La Ilustración Española y Americana at an 1885 exhibition (48), depict the subject in the act of seeing. The reader of the magazine sees the woman, and the woman is looking at the display cases mounted by the journal. The interactive nature of the image is further reinforced when the woman in the magazine looks back and acknowledges the reader’s gaze. Rodríguez-Galindo ends this chapter with a discussion of guidebooks and maps, using Henri Lefebvre and Michel de Certeau to link lived space to movement through the streets, memory, and the preoccupation with vision in the modern city of Madrid.

While chapter 1 functions as an overview, chapter 2, “Making Modernity,” tackles the way foreign words and pastimes were brought into, altered by, and integrated into the life of Madrid. Here, Rodríguez-Galindo makes a strong case for the importance of thinking through modernity by studying cities outside Paris, London, and New York:

The visual culture of a so-called peripheral city like Madrid . . . brings to the fore the shortcomings of [an] account of modernity as break, while also exposing how historical awareness and consciousness of change worked. When notions like break and rupture are replaced by the less restrictive terms of dialogue and negotiation, we can see that references to the past or extant aesthetic conventions were an integral part of modernisation (79).

Words such as modernidad (modernity), modernización (modernization), and modernizer (to modernize) were not commonly used in nineteenth-century Spain, and Rodríguez-Galindo notes that the word modernizer was not accepted by the Real Academia Española until 1925. Interestingly enough, the word had first appeared some fifty years earlier in illustrated journals aimed at women, such as La Moda Elegante . Rodríguez-Galindo has also mined the comic press for cartoons making fun of new language expressions and their fluidity of meaning. A few of the images, such as figure 2.3, Manuel Luque’s Modismos del lenguaje , [1] are reproduced at such a small size that the reader can only appreciate their humor with a magnifying glass and (for those who don’t read Spanish) a dictionary, which might have been remedied by the author with a more explicit discussion of their contents. Others however, such as 2.4, George du Maurier’s A Choice of Idioms , [2] are larger and, because the joke is in English, used to make a similar point. This chapter ends with a discussion of images depicting one of Madrid’s newest fads—roller skating—and a regularly occurring event: the demolition of old buildings to make room for the new. The point, Rodríguez-Galindo makes clear in the final pages of this section, is that foreign words, modes of entertainment, and changes in city planning were not simply imported imitations embraced by the public in Spain. They were “mediated in conjunction with local concerns and pre-existing tropes” (111). The “implications of urbanisation for lived experience can only be coherently understood in conjunction with memory and affect” (115).

Chapter 3, “Strolling in the City: The Flâneur Interrupted,” shows how the Spanish social tradition of walking outdoors redefines the modern notion of the solitary observer à la Baudelaire. Rodríguez-Galindo once again demonstrates her love of words in a fascinating section on the various verbs, both native (for example, callejear , vaguear , pasear [roam the streets, wander about, stroll]) and borrowed ( flanear ), employed to describe the Spanish pastime of walking with a friend and seeing acquaintances on the street. Illustrations in the popular press depict both women and men meeting up to exchange news, engage in small talk, and create community. This chapter focuses on sociability in Madrid’s main square, the Puerta del Sol, which serves as the geographic center of Spain. From here, kilometer zero, the six national roads radiate outward to the provinces; these are the highways that allow people to move into and out of the capital. A map of the city would have been useful here (one does appear in chapter 1 and a second in chapter 4), and a discussion of a paseo (promenade) through the Puerta del Sol in comparison to strolling along the Prado might have deepened this discussion. Readers who wish to take up this challenge should begin with Eugenia Afinoguénova’s excellent book on Spanish culture and leisure, The Prado . [3] Her discussion of the paseo on the Prado, site of the city’s famous museum of the same name, is a likewise enriching introduction to Spanish tradition and modernity.

Rodríguez-Galindo turns in the next chapter from hybrid versions of the flâneur that “show the fluidity between perceptions of localness and foreignness” (156) to a consideration of nineteenth-century costumbrismo in the context of memory, nostalgia, and tradition. Costumbrismo is a difficult term to define in English; the Real Academia defines the word costumbre as a “manera habitual de actuar y compartarse,” or a “habitual manner to act and comport oneself.” [4] Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century costumbrista images usually depict single individuals on a blank page wearing regional clothing or holding the traditional tools of their trade, whereas late nineteenth-century images are more often multi-figured scenes of diverse people engaged in the activities of everyday life. Rodríguez-Galindo, who notes the humor and social commentary embedded in these images, does not see the continued popularity of this genre in Spain as old-fashioned or anti-modern. Concepts like nostalgia, she points out, may at first glance “seem to contradict that of modernisation, and indeed this paradox yielded some of the binary divides that have characterised the literature of modernity: tradition/newness, past/present.” But “recollection and nostalgia were inherent features of the modernising process, both in Spain and abroad” (186). Old “types” ( costumbrista images never depict identifiable individuals) were updated and new ones were introduced. The water carrier, the seamstress, the waiter, and the tram passenger are among just a few of those discussed. She ends chapter 4, entitled “Sketching Social Types,” with a discussion of the tren botijo , the popular excursion train used by the jug-toting masses (the botijo is a water jug carried aboard the train to provide refreshment during the sweltering journey) who sought escape from the city during the hot summer holidays.

The fifth and final chapter of Madrid on the Move , “Creating Hybrid Surfaces,” further explores costumbrismo , caricature, and photography in the intertextual context of the illustrated journal, which brings image, caption, and text together into a mutually reinforcing dialogue. Rodríguez-Galindo returns in this chapter to the notion of self-reflectivity, pointing in a convincing manner to the way periodical images can “break the fourth wall” and open up the dialogue to the viewing reader. The question of whether costumbrismo is a conservative or modern mode of representing the city and its residents is likewise revisited, with the author forcefully rejecting either/or answers that close down rather than open up the meanings of modernity. And she concludes the chapter with a consideration of truth—and realism—noting how often both photographs and drawings were captioned del natural , or taken from life. As with the other binaries that are tackled in this text, “the interconnections between sketches and photography . . . suggest that rupture between the two media was not abrupt, whether in conceptual, temporal, or material terms” (244). “Feeling modern and visually aware,” the subtitle of this fascinating book, entails acknowledging the messiness of contemporary life.

Madrid on the Move is Rodríguez-Galindo’s first book, and she pleased this reader by including all her textual citations in Spanish and English. The frequent use of word play, double entendre, and colloquial phrasing in her primary source material made the presence of the Spanish originals and English translations edifying and entertaining. I rarely questioned her word choices. The absence of color images was missed only once, when the juxtaposition of colors on a mid-century map marking the layering of temporal changes to buildings on the Puerta del Sol was completely imperceptible in the black-and-white illustration (fig. 4.11). This book is theoretically informed—the author makes use of a broad range of interdisciplinary thinkers, including Walter Benjamin (of course!), Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Maurice Halbwachs, and Georg Simmel in addition to Lefebvre and Certeau, without being pedantic—and was a pleasure to read. I look forward to the next.

[1] Manuel Luque, “Modismos del lenguaje,” El Mundo Cómico , no. 77 (April 19, 1874): 4–5.

[2] George du Maurier, “A Choice of Idioms,” Punch’s Almanack for 1888 (December 8, 1887).

[3] Eugenia Afinoguénova, The Prado: Spanish Culture and Leisure, 1819–1939 (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2019).

[4] Real Academia Española: Diccionario de la lengua española , 23rd ed. [version 23.5 online], https://dle.rae.es . My translation.

CHAPTER 18:DISAPPOINTMENTS IN MADRID, 1890 - 91

Sep 24, 2014

360 likes | 4.93k Views

CHAPTER 18:DISAPPOINTMENTS IN MADRID, 1890 - 91.

Share Presentation

- rizal attended

- leonor rivera

- henry kipping

- 1890 rizal attended

- april 1891 rizal returned

Presentation Transcript

CHAPTER 18:DISAPPOINTMENTS IN MADRID, 1890 - 91 • Early in August, 1890 – Rizal arrived in Madrid. He tried all legal means to seek justice for his family and the Calamba tenants, but to no avail. He almost fought to duels – one with Antonio Luna and the other to Wenceslao E. Retana. Leonor Rivera married a British Engineer (Henry Kipping) • Rizal’s Misfortunes in Madrid: - FAILURE TO GET JUSTICE FOR FAMILY Asociacion Hispano – FilipinaLiberal Spanish newspapers (La Justicia, El Globo, La Republica, El resumen, etc).M. H. Del Pilar – acted as his lawyer.Dr. Dominador Gomez – secretary of Asociacion Hispano – Filipina.Minister of Colonies (SeñorFabie)Gen. ValerioWeyler & Dominicans

- MORE TERRIBLE NEWS REACHED RIZAL IN MADRID From Silvestre Ubaldo, he received a copy of the ejectment order by the Dominicans against Francisco Rizal and other Calamba tenants. From Saturnina, he learned of the deportation of Paciano, Antonio Lopez, Silvestre Ubaldo, Teong, and Dandoy to Mindoro. His parents were forcibly ejected from their home and were then living in the house of Narcisa. -RIZAL’S EULOGY TO PANGANIBAN Jose Ma. Panganiban – his friend and his talented co-worker in the propaganda.August 19, 1890 – date of the death of Jose Ma. Panganiban because of a lingering illness.

JOSE MA. PANGANIBAN - Itinago ang tunay na pangalan sailalim ng sagisag na JOMAPA - Kilala sa pagkakaroon ng “MEMORIA FOTOGRAFICA” - Kabilang sa mga Kilusang Makabayan MGA AKDA NI JOMAPA: • ANG LUPANG TINUBUAN • SA AKING BUHAY • SU PLAN DE ESTUDIO • EL PENSAMIENTO

ABORTED DUEL WITH ANTONIO LUNA End of August, 1890 – Rizal attended a social reunion of the Filipinos in Madrid. Antonio Luna became drunk. Luna was bitter because of his frustrated romance with Nellie Boustead. He was blaming Rizal for his failure. Luna uttered certain unsavory remarks for Nellie. Rizal heard him and challenge for a duel. The Filipinos were shocked of the incident. They tried to pacify Rizal and Luna, pointing out to both that such a duel would damage their cause in Spain. Luna, when he became sober, realized that he had made a fool and he apologized to Rizal.

RIZAL CHALLENGES RETANA TO DUEL Wenceslao E. Retana , the bitter enemy of Rizal in pen. Attacked Filipinos including Rizal, in various newspaper in Madrid La Epoca – an anti- Filipino newspaper . He insulted Rizal’s family, so Rizal challenged to a duel. Retana at once published a Retraction and apology in the newspaper. The incident silenced Retana’s pen against Rizal. Later on he write the biography of the greatest Filipino hero, whose talents he came to recognize and whose martyrdom he glorified.

INFIDELITY OF LEONOR RIVERA Teatro Apollo Rizal attended a play together with his friends and he lost his locket containing the picture of Leonor December, 1890 Rizal received a letter from Leonor, announcing her coming married with an Englishman (Henry Kipping) February 15, 1891 Blumentritt replied to the letter of Rizal and comforted Rizal when Rizal confide to him about his agony and broken heart.

- RIZAL – DEL PILAR RIVALRY 1890 There arise an unfortunate rivalry between Rizal and del Pilar for supremacy. January 1, 1891 (New Year’s Day) the Filipinos of Madrid met to reorganize the Asociacion Hispano – Filipina Responsable - a new leader who would act as a spokesman of the Filipino cause in Europe2/3 votes needed to be declared as Responsible. - RIZAL ABDICATES HIS LEADERSHIP February 1891 – (1st week) election starts Filipinos were divided into two rival camps: Rizalistas - Pilaristas. Paterno appealed to the members so that Rizal won the position.

Ilustrados in Madrid

BACK TO BRUSSELS (February 1891) - Left Madrid and proceeded to Biarritz, where he was a welcomed guest of the Boustead at their Villa Eliada. - He wrote to Jose Ma. Basa, expressing his wish to live in Hongkong and practice medicine. - Middle of April 1891 – Rizal returned to Brussels for one reason, to finish his second novel. Jose Alejandrino, Rizal's roommate in Belgium and the first person who cleverly read the El Filibusterismo.

- More by User

Quantity Take Off

Quantity Take Off. Applied Science University. Dr. Ayman A. Abu Hammad. Topical Overview. Chapter 1: Site Preparation Chapter 2: Soil and Site Exploration Chapter 3: Excavation Chapter 4: Foundations Work Chapter 5: Wood Formwork Chapter 6: Steel Rebar Chapter 7: Concrete

1.14k views • 25 slides

CHAPTER 21 Progressivism from the Grass Roots to the White House 1890 1916

Grassroots Progressivism Civilizing the City Settlement House Movement Jane Addams

1.32k views • 18 slides

Progressivism 1890-1920

Progressivism 1890-1920. Chapter 21. Progressive Reformers. Progressive beliefs / conservative direction - the array of disgust/ need for change Progressive reformers - muckraker- reporters - “robber barons” & “ghettos” Increase in newspaper and magazine circulation.

981 views • 18 slides

Chapter One

Chapter One. How did the man help the dog?. Chapter One. What did the man have setting on his mantle?. Chapter One. Where do you think the dog was going when he left the man?. Chapter Two. What terrible disease did the young boy have in this chapter?. Chapter Two.

1.39k views • 27 slides

THE PROGRESSIVE MOVEMENT 1890-1919 Chapter 13

THE PROGRESSIVE MOVEMENT 1890-1919 Chapter 13. Industrialization changed American society…. Cities were crowded with new immigrants, working conditions were often bad, and the old political system was breaking down. These conditions gave rise to the Progressive movement.

1.03k views • 63 slides

Chapter 23: XML

Chapter 23: XML. Database System Concepts. Chapter 1: Introduction Part 1: Relational databases Chapter 2: Introduction to the Relational Model Chapter 3: Introduction to SQL Chapter 4: Intermediate SQL Chapter 5: Advanced SQL Chapter 6: Formal Relational Query Languages

1.65k views • 92 slides

Practicals on Security – Infosys -- WMS

Practicals on Security – Infosys -- WMS. GILDA Tutors INFN EELA Tutorial Madrid, 23.02.2006. Access to the User Interface. Login [email protected] where XX=01,..40. Passwd : GridMADXX XX=01,..,40. PEM PASSPHRASE : MADRID. Practicals on VOMS and MyProxy.

1k views • 82 slides

The Progressive Era 1890-1920

The Progressive Era 1890-1920. “What were the causes and effects of the Progressive Movement?”.

1.5k views • 101 slides

Ch. 11: The Progressive Reform Era (1890-1920)

Ch. 11: The Progressive Reform Era (1890-1920). Section 1: Origins of Progressivism. The early 20 th century brought a series of domestic reforms, known as progressivism. Roots of 20 th Century Reform. Populism: William Jennings Bryan Social Gospel Movement Prohibition Electoral reforms

1.18k views • 85 slides

2D anisotropic fluids: phase behaviour and defects in small planar cavities

2D anisotropic fluids: phase behaviour and defects in small planar cavities. D. de las Heras 1 , Y. Martínez-Ratón 2 , S. Varga 3 and E. Velasco 1 1 Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain 2 Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain 3 University of Pannonia, Veszprem, Hungary. MODEL SYSTEM

1.07k views • 85 slides

APUSH II: Unit 1 Chapter 18: Conquest and Survival of the West, 1860 - 1900

APUSH II: Unit 1 Chapter 18: Conquest and Survival of the West, 1860 - 1900. Essential Question : What economic, political, & migratory factors led to the end of the western frontier by 1890?. What is the “West”?.

1.1k views • 72 slides

Biochemistry

Biochemistry. Chapter 13: Enzymes Chapter 14: Mechanisms of enzyme action Chapter 15: Enzyme regulation Chapter 17: Metabolism- An overview Chapter 18: Glycolysis Chapter 19: The tricarboxylic acid cycle Chapter 20: Electron transport & oxidative phosphorylation Chapter 21: Photosynthesis

3.47k views • 86 slides

Chapter 27 Empire and Expansion

Chapter 27 Empire and Expansion. 1890-1909. Summary.

896 views • 73 slides

Chapter 9 . Drugs and Toxicology (PBS-secrets of dead –executed by error -56 min). A bottle of Bayer's 'Heroin'. Between 1890 and 1910 heroin was sold as a non-addictive substitute for morphine. It was also used to treat children suffering with a strong cough.

1.32k views • 105 slides

Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Madrid

Backstage and collection highlights from Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week in Madrid.

2.02k views • 34 slides

- Member Login

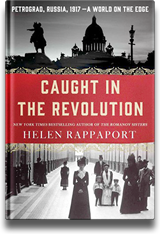

An Englishman in Madrid

Written by Eduardo Mendoza Nick Caistor (trans.) Review by Sarah Bower

In the spring of 1936, art historian Anthony Whitelands is sent to Madrid to advise the Duke of La Igualada on the value of paintings he wishes to sell abroad in order to support his family in the event of their having to go into exile as a consequence of the political upheavals in Spain. The paintings turn out to be worthless, the Duke’s family more involved in politics than they appear to be, and the hapless Anthony finds himself drawn into intrigues both political and romantic for which he is completely unprepared. And that is before the small matter of the missing Velasquez in the Duke’s basement.

From a leisurely beginning, Mendoza’s Planeta Prize-winning novel unfolds into a black comic adventure of an Englishman abroad in the tradition of Evelyn Waugh. While delivering an astute, erudite and damning indictment of the Spanish establishment, blundering into civil war out of idleness, irresponsibility and apathy, it is a quietly hilarious farce, stuffed with double agents, enigmatic diplomats, charlatans, girls hidden in wardrobes and a convoluted sleight of hand surrounding the missing Velasquez so impossible to explain there is no danger of plot spoilers from this reviewer.

An Englishman in Madrid is not a light or easy read, although Caistor’s translation is fluent and elegant. It requires some concentration to keep abreast of the complexities of the political situation as well as the many misadventures which befall Anthony. The different plot strands sometimes seem a little awkward in their meshing, yet I was sorry to finish the book and was left with the sense of having experienced something both erudite and delightful when I closed it for the last time.

APPEARED IN

REVIEW FORMAT

Share Book Reviews

Latest articles

Dive deeper into your favourite books, eras and themes:

Here are six of our latest Editor’s Choices:

Browse articles by tag

Browse articles by author, browse reviews by genre, browse reviews by period, browse reviews by century, browse reviews by publisher, browse reviews by magazine., browse members by letter, search members..

- Search by display name *

COMMENTS

MISFORTUNES IN MADRID (1890-91) 6:17 AM 6 comments. -Early in August, 1890, Rizal arrived in Madrid. -Upon arrival in Madrid, Rizal immediately sought help of the Filipino colony, The Asociacion Hispano-Filipina, and the liberal Spanish newspaper in securing justice for the oppressed Calamba tenants. · El Resumen- a Madrid newspaper which ...

due to Luna's jealousy, wc his alcohol-befogged mind could not control, he uttered certain unsavory remarks about Nellie. rizal could not tolerate Luna's words so he challenged Luna to a ... Chapter 17 Misfortunes in Madrid (1890-91) early in ... rizal arrived in Madrid. Click the card to flip 👆. August 1890. Click the card to flip 👆.

Misfortunes in madrid (1890 91) ... • Years afterwards he wrote the first book length biography of the greatest Filipino hero. 11. • One night in the autumn of 1890, Rizal and some friends attended the play at theater Apollo and lost his gold watch chain with a locket containing the picture of Leonor Rivera. • The lost of the locket ...

1. CHAPTER 17 Misfortunes in Madrid (1890-91) 2. Failure to Get Justice for the Family • Asociacion Hispano- Filipina Sought • Liberal Spanish help newspapers • La Justicia, El Globo, La Republica, El Resumen, etc. •Secure justice Why? •For oppressed Calamba tenants & family. 3.

La Epoca - an anti-Filipino newspaper in Madrid.He insulted Rizal's family. Because he believed that discretion is the better part of valor, and more to save his own skin. Retana at once published a retraction and an apology in the newspapers,

Early in August 1890, Rizal arrived in Madrid. He tried all legal means to seek justice for his family and the Calamba tenants, but to no avail. Disappointment after disappointment piled on him, until the cross he bore seemed insuperable to carry. He almost fought two duels - one with Antonio Luna and the other with Wenceslao E. Retana.

Chapter 17 Misfortunes in Madrid (1890-91) 1 FAILURE TO GET JUSTICE FOR HIS FAMILY: When Rizal arrived in Madrid, he implored help from Asociacion Hispano-Filipina and other liberal Spanish newspapers to secure those Calamba tenantsand his family. Marcelo H. del Pilar - lawyer Dr.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like 1. Failure to Get Justice for his family 2. Almost fought duels with Antonio Luna and Wenceslao Retana 3. Marriage of Leonor Rivera to a British man as per the choice of her mother, 1. Filipino Colony 2. Asociacion Hispano-Filipina 3. Liberal newspapers (La Justicia, El Globo, La Republica, El Resumen), Marcelo H. del Pilar and more.

17_Misfortunes_in_Madrid_(1890-1891) - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Rizal faced many setbacks and misfortunes in Madrid between 1890-1891 as he sought justice for the oppressed Calamba tenants. He tried to get help from Spanish liberal newspapers and politicians but failed. The Calamba tenants received an ejectment order and some were deported.

The evidence for these assertions is drawn from illustrated newspapers and satirical reviews published in Madrid between the 1860s and the mid-1890s. Chapter 1, "Seeing the City," considers how nineteenth-century madrileños (residents of Madrid) both saw the city and saw in the city. Arguing that how we can and cannot see is a question ...

Chapter 17: Misfortunes in Madrid (1890-91) Failure to Get Justice for Family M. del Pilar - acted as Rizal's lawyer Dr. Dominador Gomez - secretary of the Asociacion Hispano-Filipina) El Resumen - a Madrid newspaper which sympathized with the Filipino cause. ... a "work of the head" and a "book of the thought". >Contains ...

This is my report about the following misfortunes experienced by the national hero of the Philippines Dr. José Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda .I...

MISFORTUNES IN MADRID ( 1890-1891 ) Upon the arrival in Madrid, Rizal sought the help of the : Filipino Colony - the Asosacion Hispano - Filipina and the. Liberal Spanish Newspapers ( La Justicia, El Globo, La Republica, El Resumen, etc. ) M.H. del Pilar - acted as the lawyer of Dr. Jose Rizal. Dr. Dominador Gomez - secretary of the Asosacion ...

Misfortunes in Madrid (1890-1891) misfortunes in madrid august, 1890, rizal arrived in madrid. upon arrival in madrid, rizal immediately sought help of the ... August 6, 1891-the printing of his book had to be suspended because Rizal could no longer give the necessary funds to the printer. Valentin Ventura- the savior of the Fili, when he ...

Make a book review about "In Madrid, 1890-91" by answering the questions bellow: ONLINE BOOK REVIEW Date of reviewing: Name of Reviewer: Title: A brief synopsis: Introduce the lesson: Tell about the lesson, but don't give away the ending: Tell about your favorite part of the lesson/story or make a connection: Give a recommendation ( e.g.

CHAPTER 17 MISFORTUNES IN MADRID (1890-1891) Rizal arrived in Madrid at the beginning of August 1890. He attempted all legal means to seek justice for his family and the tenants of Calamba, but to no avail. ... Reviews. 5 (1) View all. 140 Points. Download. Report document. Bath Spa University History. 11 Pages. 1. 2019/2020.

He developed a great admiration for the latter, and years afterward he wrote the first book-lenght biography of the greatest Filipino hero, whoose talents he came to recognize and whose martyrdom he glorified. Infidelity of leonor Rivera. In the autumn of 1890 Rizal was feeling bitter at so many disappointments he encountered in Madrid.

Dyanne Kuin Gevero. Rizal encountered many hardships during his time in Madrid from 1890-1891. He almost fought two duels, one with Antonio Luna and another with Wenceslao Retana. Additionally, the infidelity of his love Leonor Rivera broke his heart. Rizal also faced rivalry with Marcelo H. del Pilar for leadership of the Propaganda Movement.

Misfortunes In Madrid (1890-91) Uploaded by: Isza Marie N. Socorin. October 2021. PDF. Bookmark. Download. This document was uploaded by user and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this DMCA report form. Report DMCA.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like "Chapter 16 In Belgian Brussels (1890)", · January 28, 1890, Þ the cost of living in Paris was very high because of the Universal Exposition Þ the gay social life of the city hampered his literary works, especially the writing of his second novel El Filibusterismo. and more.

Presentation Transcript. CHAPTER 18:DISAPPOINTMENTS IN MADRID, 1890 - 91 • Early in August, 1890 - Rizal arrived in Madrid. He tried all legal means to seek justice for his family and the Calamba tenants, but to no avail. He almost fought to duels - one with Antonio Luna and the other to Wenceslao E. Retana.

An Englishman in Madrid. Written by Eduardo Mendoza Nick Caistor (trans.) Review by Sarah Bower. In the spring of 1936, art historian Anthony Whitelands is sent to Madrid to advise the Duke of La Igualada on the value of paintings he wishes to sell abroad in order to support his family in the event of their having to go into exile as a consequence of the political upheavals in Spain.

Nagpaalab sa damdamin ni Antonio Luna. Agosto 1890. dumalo si Rizal sa isang salu-salo ng mga Pilipino sa Madrid. Ang nabigong pag-ibig nito kay. Ngunit ang huli'y magaling sa eskrimahan. Nellie Boustead. Muling pagbangon ng puso ni Rizal mula sa pagkabigo kay Leonor Rivera. Anak ng tinuluyan ni Rizal.