- Print This Page

- Text Size

- Scroll To Top

Information Aquí

Our Golden Anniversary!

Coming together to help peruvians in need.

PAMS Medical Missions to Perú

Peruvian American Medical Society

- International Opportunities

- Global Medical Education

Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH)

SBU Advisor: Luis A Marcos, MD International Site Coordinator: Andres (Willy) Lescano, PhD

The Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia is the most notable site in Peru for training in medicine, tropical medicine and public health. in 2016, Stony Brook signed an MOU with UPCH, which was facilitated by Dr. Luis A Marcos from the Department of Medicine's Division of Infectious Diseases at the Renaissance School of Medicine, where he carries out a variety of studies in tropical and other communicable diseases. There are opportunities for both clinical and research electives under the direction of Dr. Marcos.

- Research note

- Open access

- Published: 20 August 2020

Perception of medical students about courses based on peer-assisted learning in five Peruvian universities

- Anderson N. Soriano-Moreno ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5535-811X 1 ,

- Jose E. Delgado-Raygada 2 ,

- C. Ichiro Peralta 3 ,

- Estefania S. Serrano-Díaz 4 ,

- Jaquelin M. Canaza-Apaza 1 &

- Carlos J. Toro-Huamanchumo 5 , 6

BMC Research Notes volume 13 , Article number: 391 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2801 Accesses

2 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Peer-assisted learning (PAL) is a supportive strategy in medical education. In Peru, this method has been implemented by few universities. However, there are no consistent studies evaluating their acceptability by medical students. The objective of this study was to evaluate the perception of medical students about PAL in five Peruvian universities.

A total of 79 medical students were included in the study. The mean age was 20.1 ± 1.9 years, 54% were female, and 87% were in the first 4 years of study. Most of the students were satisfied with classes and peer teachers. Similarly, most of the students agreed with the interest in developing teaching skills. It was also observed that 97% of students approved to implement PAL in medical education programs.

Introduction

Peer-assisted learning (PAL) is a supportive strategy that consists of students helping their peers to learn while they are involved in the learning process by teaching [ 1 ]. Over the years, PAL has become part of medical education programs in different countries and has been identified as an enriching and effective learning method [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ].

In the United States, 76% of medical schools have implemented this methodology as a complementary activity of regular career courses [ 6 ]. In Latin America, PAL has been recently developed as part of educational reforms to improve teaching quality [ 7 ].

This innovative method has demonstrated benefits for both peer teachers and learners. Some of the benefits for peer teachers are the development of complex teaching skills, leadership skills, communicative skills, a gain in self-confidence and learning consolidation [ 1 , 3 , 4 , 8 , 9 ]. The most important advantages for peer learners are the reinforcement of clinical knowledge, the facilitation of the learning process and the enhancement of their academic level [ 1 , 3 , 9 , 10 ].

In Peru, the Academic Standing Committee, part of the Sociedad Cientifica Medico Estudiantil Peruana (SOCIMEP), has been promoting the implementation of academic tools with innovative and highly effective methods in many affiliated medical schools. Among these tools, activities using PAL seemed to have achieved high acceptance by medical students. However, there is a lack of objective measurements about the real effectiveness of PAL, as well as its impact on the students’ satisfaction. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the perception of medical students about PAL in five Peruvian universities.

Study design

We conducted a survey-based study to evaluate the participants’ perception of reinforcement courses developed with the PAL method in five Peruvian medical schools, from January to March 2018.

Sample size and sampling methods

The surveys were applied to the entire target population in a period of 7 days.

Eligibility criteria

At the beginning of the year, universities that planned to take courses based on PAL were invited to participate in the study. A total of five universities were included since they developed this activity between January and March.

Format of the courses

PAL-based courses covered different topics related to basic medical sciences. All of them followed the recommendations provided by the Association of Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) guidelines for proper planning and implementation of PAL in medical schools [ 11 ].

Selection of peer teachers

Selection of peer teachers was conducted in each university and prior to course planning. Initially, an announcement was published for the recruitment of students interested in teaching. The students went through an evaluation process, which consisted of making a ten-minute model class. Those who reached subject knowledge, conveyed clearly the information, followed a teaching method and used interactive materials (e.g., slides, videos, or board) were finally selected.

We used a questionnaire to collect data from our participants. Because there was no validated tool, we designed an instrument based on items from published papers and recommendations given in the literature [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The questionnaire was reviewed by a professor with expertise in medical education who led the initiation of PAL in one of the universities included in the study. Also, a Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire in a sample of twenty medical students, resulting in acceptable reliability for the first and second subsection (0.78 and 0.73 respectively), good reliability for the third and fourth (0.84 and 0.87 respectively) and good reliability for all the questionnaire (0.86, 95% CI 0.75–0.93).

The questionnaire had a three-section structure. Section A compressed sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex and study year). Section B compressed 28-Likert scale questions divided into four subsections (satisfaction with the course, satisfaction with the teacher’s performance, motivation to develop teaching skills and preference to implement PAL in the medical school curriculum). Section C compressed three open questions (What did you like the most about the courses? What could be improved? How was the experience of learning from another student?) that complemented the answers from section B (Additional file 1 : Appendix S1).

Analysis and presentation of data

Results were introduced into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and then exported to Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LLC, TX, USA). Descriptive analysis was used for the sociodemographic characteristics, and mean scores for each Likert-scale item were expressed in tables using means and medians. The answers from open questions were reviewed and categorized into common-word groups.

The Institutional Review Board of the Universidad Peruana Union approved the study with resolution No. 2018-101. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Through the participation and completion of the questionnaire, the students authorized their inclusion in the study.

A total of 79 medical students were included in the study (response rate: ~ 80%). The mean age was 20.1 ± 1.9 years, 54.4% were female, and 87.3% were in the first 4 years of study (Additional file 2 : Appendix S2 (Table S1)).

Perception of medical students about PAL

In the first subsection of section B, nine statements related to positive facts in the class had an average score higher than 3.99 and medians between 4 (Agree) and 5 (Strongly agree). Negative statements were answered with low scores. Statements “I would have preferred classes to be done by a teacher” and “Only a doctor should teach these subjects” obtained a median of 3 (Neutral) and 2 (Disagree), respectively (Table 1 ).

Regarding the satisfaction with the peer teachers, positive results were observed. In all the positive statements, scores greater than 4 (Agree) were obtained. Only in the negative statement “There were questions that the peer-teacher could not answer” the median obtained was 3 (Neutral) (Table 2 ).

Regarding the motivation of the participants to be peer teachers in the future and to develop teaching skills, 78.5% (62/79), 93.7% (74/79) and 89.9% (71/79) scored higher than 4 (Agree) the statements “The course encouraged me to practice teaching in the future”, “The practice of undergraduate teaching would be very beneficial for my professional development” and “I would like to attend to a session to learn teaching skills” (Table 3 ).

In the subsection of participants’ interest to implement PAL in medical schools, we found that 98.7% (78/79) scored higher than 4 (Agree) the statement “I would like to see classes implemented through PAL in summer”. Also, 97.4% (77/79) rated the statement “It would be useful to implement PAL-based courses in the university curriculum” with scores higher than 4 (Table 3 ).

Answers to open questions

The most frequently observed response regarding what the students liked the most about the course was the “teaching and didactic of the peer-teacher” (32.9%). The method and structure of the course were also considered of high value by 14 participants (17.7%). When participants were asked about what could be improved about PAL-based courses, 18 (22.8%) students answered “nothing”, 11 (14.1%) said that longer courses are needed, and 11 (14.1%) indicated that other educational resources should be used. Finally, in the question that assessed what students think about learning from another student, 35 answers (44.3%) were observed with the words “Very good, good, and incredible” and another 15 (18.9%) related with the peer teacher’s empathy and the confidence that they provided (Additional file 2 : Appendix S2 (Table S2)).

We evaluated the perception of medical students about courses using the PAL strategy in five medical schools in Peru. We observed that students had positive perceptions about the program, peer teacher, motivation to be a peer teacher, and interest to implement this approach into the regular curriculum. These results are a good approach to the benefits of developing PAL, being consistent with previous reports [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 14 ]. However, systematic reviews have not shown enough evidence to demonstrate its efficacy in some aspects [ 3 , 15 ].

PAL-based courses promote the social congruence between the peer teacher and the learner in a comfortable interaction environment [ 1 , 3 , 4 ]. This could explain why students often feel satisfied with this strategy, as we presented in our study. Another possible explanation might be that the peer teacher and the students share a similar academic background. It was observed that students valued the learning from peer teachers because they understand the students’ struggles in medical school and the shared experiences are valuable assets [ 1 ].

We also found that participants had a positive attitude towards becoming peer teachers. Previous studies have reported the advantages of achieving this, which include a better understanding of the topic being taught and leadership development [ 1 , 16 ]. Therefore, it should be considered as an opportunity for self-improvement. Our study showed that after the PAL-based sessions, the participants were motivated to learn teaching skills and considered that this would be a benefit for their professional development. Similar results have been reported in previous studies, and the awareness of the benefits of PAL among medical students probably encourages their training to become peer-teachers [ 1 , 17 , 18 ].

Participants also agreed with the implementation of PAL in their regular curriculum. This might be a reflection of the need to use novel medical teaching methods in highly difficult courses to improve academic performance [ 19 ]. These could include learning support interventions, implementation of small working groups, training in coping strategies and learning styles, and a constant evaluation of acquired knowledge. In addition, peer teachers could be more prepared than faculty professors to teach review classes. They have a better perception of academic pitfalls and, since both the peer teacher and learners had probably experienced the same academic challenges, a more empathic learning environment could be achieved.

In our study, medical students had a positive perception of PAL. The quality of classes and the peer teachers' performance were relevant for the results. Moreover, we present the first study about PAL as a strategy to overcome crucial deficiencies in medical education in Peru. A study with a better sample size would be necessary to verify our results. However, we suggest that PAL should be implemented in Peruvian medical schools as part of their curriculum.

Limitations

First, we did not find an adequate instrument that assessed all our variables of interest; hence, we designed and developed a questionnaire instead of using a previously validated instrument. However, we tested the reliability of the survey questions, obtaining good values for Cronbach’s alphas. Second, the small sample size was also a limitation.

Availability of data and materials

Although all the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript, the datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Peer-assisted learning

Sociedad Científica Médico Estudiantil Peruana

Association of Medical Education in Europe

Standard deviation

Herrmann-Werner A, Gramer R, Erschens R, Nikendei C, Wosnik A, Griewatz J, et al. Peer-assisted learning (PAL) in undergraduate medical education: an overview. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen. 2017;121:74–81.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Furmedge DS, Iwata K, Gill D. Peer-assisted learning—beyond teaching: how can medical students contribute to the undergraduate curriculum? Med Teach. 2014;36(9):812–7.

Yu TC, Wilson NC, Singh PP, Lemanu DP, Hawken SJ, Hill AG. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:157.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Agius A, Calleja N, Camenzuli C, Sultana R, Pullicino R, Zammit C, et al. Perceptions of first-year medical students towards learning anatomy using cadaveric specimens through peer teaching. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(4):346–57.

Shah I, Mahboob U, Shah S. Effectiveness of horizontal Peer-Assisted Learning in physical examination performance. J Ayub Med College Abbottabad JAMC. 2017;29(4):559–65.

Google Scholar

Soriano RP, Blatt B, Coplit L, Cichoski-Kelly E, Kosowicz L, Newman L, et al. Teaching medical students how to teach: a national survey of students-as-teachers programs in US medical schools. Acad Med. 2010;85(11):1725–31.

Barbosa-Herrera J, Barbosa-Chacon J. La tutoria entre pares. Una mirada al contexto universitario en Latinoamerica. Rev Espacios. 2019;40(15):30.

Cobos-Aguilar H, Perez-Cortes P, Bracho-Vela LA, Garza-Garza MA, Davila-Rodriguez G, Lopez-Juarez DO, et al. Habilidades docentes en alumnos tutores en lectura critica de investigacion medica durante el internado de pregrado. Investigacion en educacion medica. 2014;3(10):92–9.

Article Google Scholar

Mills JK, Dalleywater WJ, Tischler V. An assessment of student satisfaction with peer teaching of clinical communication skills. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):217.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Keifenheim KE, Petzold ER, Junne F, Erschens RS, Speiser N, Herrmann-Werner A, et al. Peer-assisted history-taking groups: a subjective assessment of their impact upon medical students’ interview skills. GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(3):1–15.

Robinson Z, Hazelgrove-Planel E, Edwards Z, Siassakos D. Peer-assisted learning: a planning and implementation framework. Guide supplement 30.7–practical application. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):e366-8.

Field M, Burke JM, McAllister D, Lloyd DM. Peer-assisted learning: a novel approach to clinical skills learning for medical students. Med Educ. 2007;41(4):411–8.

Glynn LG, MacFarlane A, Kelly M, Cantillon P, Murphy AW. Helping each other to learn–a process evaluation of peer assisted learning. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(1):18.

Knobe M, Münker R, Sellei RM, Holschen M, Mooij SC, Schmidt-Rohlfing B, et al. Peer teaching: a randomised controlled trial using student-teachers to teach musculoskeletal ultrasound. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):148–55.

Burgess A, McGregor D, Mellis C. Medical students as peer tutors: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):115.

Erlich DR, Shaughnessy AF. Student–teacher education programme (STEP) by step: transforming medical students into competent, confident teachers. Med Teach. 2014;36(4):322–32.

Cate OT, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591–9.

Moore K, Vaughan B. Students today… educators tomorrow. Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):325–9.

Wong JG, Waldrep TD, Smith TG. Formal peer-teaching in medical school improves academic performance: the MUSC supplemental instructor program. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):216–20.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This study was self-funded.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sociedad Científica de Estudiantes de Medicina de la Universidad Peruana Unión, Universidad Peruana Unión, Lima, Peru

Anderson N. Soriano-Moreno & Jaquelin M. Canaza-Apaza

Sociedad Científica de Estudiantes de Medicina de la Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, Lima, Peru

Jose E. Delgado-Raygada

Sociedad Científica de Estudiantes de Medicina Villarrealinos, Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal, Lima, Peru

C. Ichiro Peralta

Sociedad Científica de Estudiantes de Medicina de la Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Trujillo, Peru

Estefania S. Serrano-Díaz

Clínica Avendaño, Lima, Peru

Carlos J. Toro-Huamanchumo

ASME, Association for the Study of Medical Education, Edinburgh, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ANS-M, JED-R, CIP, ESS-D, JMC-A and CJT-H conceived the idea, conceptualized the study design, performed and reviewed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anderson N. Soriano-Moreno .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: appendix s1..

Questionnaire developed for this study.

Additional file 2: Appendix S2.

Extra results tables. Contains the Table S1. General characteristics of the students surveyed and the Table S2. Summary of the most common free-text responses.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Soriano-Moreno, A.N., Delgado-Raygada, J.E., Peralta, C.I. et al. Perception of medical students about courses based on peer-assisted learning in five Peruvian universities. BMC Res Notes 13 , 391 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05237-5

Download citation

Received : 07 November 2019

Accepted : 17 August 2020

Published : 20 August 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05237-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical students

- Medical education

BMC Research Notes

ISSN: 1756-0500

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Register Now

- Classic Service Learning Trips

- High School Service Learning Trips

- Dental Service Learning Trips

- Nursing Service Learning Trips

- Custom Educational Trips

- Virtual Service Learning Trips

- Reduce Trip Costs

- Volunteer Resources Guide

- Volunteer Safety

- Testimonials

- COVID-19 Response

- Development

- Our Approach

- Cusco, Peru

- Riobamba, Ecuador

- Tena, Ecuador

- Tamarindo, Costa Rica

- San Jose, Costa Rica

- Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

- Antigua, Guatemala

- Meet Our Team

- Partners & Grants

- Join or Start A Chapter

- Refer a Friend

- Organize a Service Trip

- Leadership & Career Opportunities

- Fundraise for Moving Mountains

- Get MEDLIFE Merch

- Contact MEDLIFE

- Sign Up For A Service Learning Trip

The Healthcare Landscape in Peru: Challenges and Progress

By Mary Bourke

The healthcare landscape in Peru faces numerous challenges, despite the nation’s rich cultural heritage and stunning natural beauty. The Peruvian government, acknowledging these hurdles, has embarked on a journey to enhance healthcare access and foster public health initiatives. Understanding these challenges and initiatives is pivotal in grasively the complexity of Peru’s healthcare system.

Ensuring Access to Healthcare

A significant challenge within Peru’s healthcare landscape is the equitable distribution of healthcare services, particularly in rural and remote regions. While urban centers boast well-equipped medical facilities, rural areas often grapple with limited healthcare access, contributing to uneven health outcomes nationwide. Consequently, addressing this disparity remains a critical task for improving the nation’s health standards.

Promoting Public Health Initiatives

In response to the urgent need for preventive care, Peru has launched several public health initiatives aimed at disease prevention, health education, and vaccination drives to combat infectious diseases. These efforts focus on vital areas like maternal and child health, nutrition, and sanitation, underscoring their importance in enhancing the population’s overall health and well-being.

Expanding Health Insurance Coverage

The Peruvian government’s Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS) plays a crucial role in the healthcare landscape, offering essential services to those without formal employment or private insurance. Furthermore, the Social Security system extends coverage to the formally employed, broadening healthcare access for numerous Peruvians.

Strengthening Infrastructure and Resources

To bridge the infrastructure gap, Peru is investing in the expansion of healthcare facilities and medical infrastructure, particularly in underserved regions. This endeavor aims to make medical services more accessible to remote communities and addresses the need to augment the healthcare workforce, especially in rural locales.

Addressing Persistent Health Challenges

Despite progress, Peru continues to confront health challenges like infectious diseases and chronic conditions, which demand sustained prevention efforts, educational initiatives, and enhanced healthcare access to mitigate their impact.

While there are evident strides in Peru’s healthcare system, with improved access and robust public health measures, the journey towards a comprehensive healthcare solution continues, especially in diminishing the urban-rural divide and tackling prevalent health issues.

MEDLIFE is committed to this journey, striving to deliver comprehensive healthcare services to Peru’s rural areas. We invite you to join us in this endeavor, offering a chance to contribute to healthcare accessibility while gaining invaluable patient care experience. Visit our website to discover how you can participate in an upcoming Service Learning Trip !

Recent Posts

- How To Improve Leadership Skills: MEDLIFE’s Global Perspective Leadership Workshop

- How To Travel on a Budget For Your Service Learning Trip

- Essential Tips For Transitioning From High School To College

- World Water Day: A Call to Action for Students

- How MEDLIFE Enhances Your College Experience

- Chapters & Students (112)

- Community Profiles (31)

- Global Topics (54)

- Educational Workshops (15)

- Fuel Efficient Stoves Projects (1)

- Healthy Homes Projects (3)

- Home Construction Projects (17)

- Sanitation Projects (14)

- School Construction Projects (18)

- Stair Construction Projects (24)

- Patient Stories (111)

- Service Learning Trips (57)

- Intern Journal (86)

- Meet Us (56)

- Smiles Movement (1)

Take Global Action

Learn how you can make a difference.

Website Design & Development © 2024 Links Web Design, Bangor, Maine | Sitemap

Website Content Copyright © 2024 MEDLIFE

20 Best Medical schools in Peru

Updated: February 29, 2024

- Art & Design

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- Environmental Science

- Liberal Arts & Social Sciences

- Mathematics

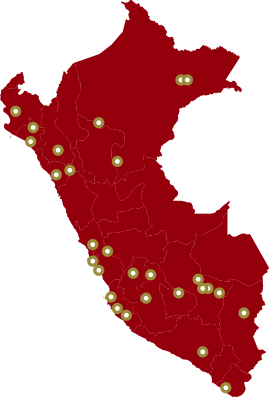

Below is a list of best universities in Peru ranked based on their research performance in Medicine. A graph of 310K citations received by 29.3K academic papers made by 20 universities in Peru was used to calculate publications' ratings, which then were adjusted for release dates and added to final scores.

We don't distinguish between undergraduate and graduate programs nor do we adjust for current majors offered. You can find information about granted degrees on a university page but always double-check with the university website.

1. Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University

For Medicine

2. National Major San Marcos University

3. Peruvian University of Applied Sciences

4. University of San Martin de Porres

5. Pontifical Catholic University of Peru

6. Scientific University of the South

7. Saint Ignatius of Loyola University

8. Agrarian National University

9. Cesar Vallejo University

10. Federico Villarreal National University

11. University of Lima

12. Saint John the Baptist Private University

13. Private University of the North

14. National University of Cajamarca

15. National University of Engineering, Peru

16. University of the Pacific - Peru

17. University of Piura

18. Alas Peruanas University

19. Los Andes Peruvian University

20. ESAN University

The best cities to study Medicine in Peru based on the number of universities and their ranks are Lima , La Molina , Trujillo , and San Miguel .

Medicine subfields in Peru

- Open access

- Published: 16 November 2023

Self-perceived competence in managing obstetric emergencies among recently graduated physicians from Lima, Peru

- Wendy Nieto-Gutierrez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8758-0463 1 &

- Alvaro Taype-Rondan 2 , 3

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 876 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

506 Accesses

Metrics details

This study aimed to examine the self-perception of competencies in obstetric emergencies among recently graduated physicians from universities in Lima, Peru; and to identify its associated factors.

An analytical study was conducted, with the study population comprising newly graduated doctors who attended the “VI SERUMS National Convention” in 2017. We used Poisson regressions to assess the factors associated with the self-perception of competencies in obstetric emergencies, calculating prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

We analyzed a population of 463 newly graduated physicians (mean age: 25.9 years), of which 33.3% reported feeling competent in obstetric emergencies. In the adjusted analyses, we found that having a previous health career (PR: 1.77, 95% CI: 1.12—2.81), having completed the internship in EsSalud hospitals (PR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.31—1.68), and completing a university externship (PR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.34—1.96) were associated with a higher prevalence of self-perceived competence in obstetric emergencies.

Our findings suggest that certain academic factors, such as completing an externship and internship in specific hospital settings, may enhance the competencies or competence self-perception of recently graduated physicians in obstetric emergencies. Further studies are needed to confirm these results and identify other factors that may impact physicians’ competencies in this field.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The medical education landscape has undergone significant changes in recent years [ 1 ], with a shift towards competency-based learning [ 2 , 3 ], which could oscillate depending on the necessity of each country. In underdeveloped countries such as Peru, there is a pressing need to develop a broader range of skills for general physicians, particularly in the area of obstetrics, due to a shortage of multidisciplinary teams, especially in rural areas [ 4 ], where the physician can be the only healthcare professional available to provide emergency care [ 5 ], with obstetric emergencies being a frequent occurrence [ 6 ].

Much like in other Latin American countries, in Peru, obstetric emergencies are a prominent contributor to both mortality and morbidity rates, with primary care serving as the initial point of reference for these cases [ 7 ], particularly in rural areas [ 8 ]. These emergencies are estimated to contribute to nearly 25% of deaths in the referenced cases, and this percentage could potentially be even higher if the initial management is not executed with precision [ 9 ]. Given this scenario, it is imperative that primary care general physicians (that most of them are recently graduated), possess the necessary skills for the primary management and support of obstetric emergencies [ 6 ]. Despite this, reports suggest that they are not adequately equipped to effectively address such critical situations [ 5 , 10 ], which has become an additional gap to an already deficient health system.

Thus, the objective of this study was to describe the self-perceived competence in managing obstetric emergencies among recently graduated physicians from Lima, Peru; and evaluate its associated factors.

Study design and population

In this cross-sectional study, we performed a secondary analysis of the previously collected database that aimed to assess the self-perceived competence of medical competencies, as published elsewhere [ 11 ].

The primary study encompassed a population of physicians who participated in the “VI National SERUMS Convention” organized by the “Colegio Médico del Perú,” held in Lima in April 2017. This convention aimed to gather all physicians who had recently graduated from medical schools in Lima and were preparing to commence the “Servicio Rural Urbano Marginal” (SERUMS), a mandatory healthcare service for newly graduated physicians in rural and underserved areas of Peru, with a duration of 12 months [ 12 ].

Out of the 693 physicians who registered for the SERUMS convention, 520 (75%) were included in the primary study, which represents approximately 14% of all physicians who started SERUMS in 2017 [ 5 ].

This secondary analysis only considered physicians who had completed their undergraduate studies at a university located in Lima, Peru, finished their gynecology-obstetrics internship at a hospital in Lima, Peru, completed their medical internship in 2016, and had a complete data for the outcome variable.

Questionary

The data collection for the primary study was done using a self-administered structured questionnaire that was validated by expert judgment from methodologists and gynecologist experts, as well as through a pilot study with five newly graduated physicians who did not attend the convention. The questionnaire consisted of six sections: 1) sociodemographic data of the participant and hospital sites, 2) perception of the medical internship, 3) competencies in general medicine, 4) competencies in obstetric care, 5) competencies in gynecology, and 6) skills in mental health. In this secondary analysis, only sections 1, 2, and 4 were used (Supplementary 1 ).

Before administering the questionnaire, a succinct study overview and procedural guideline for the questionnaire were presented at the outset of the event, ensuring participants’ accurate engagement with the survey. Participants were given opportunities to complete the survey before the event’s start and during breaks. In order to address any participant queries, two researchers were available throughout the survey administration. The data underwent a dual-entry process conducted by separate researchers to ensure accuracy. An additional researcher, not previously involved in this stage, conducted a cross-validation of the double-entered data. In instances where inconsistencies were identified, a comprehensive review of the surveys was conducted to rectify any errors.

Outcome: self-perception of obstetric emergency competence

The outcome was evaluated through the obstetric competence section of the questionnaire. The obstetric emergencies included were preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, and sepsis; which were considered the most frequent obstetric emergencies [ 13 ] and the most critical for a physician’s successful performance in their SERUMS work environment [ 6 ].

For each obstetric emergency, the questionnaire included questions about the basic procedures for managing the emergency at the primary level of health care. These procedures were based on minimum competencies and standards for accreditation of medical schools in Peru as proposed by the “Comisión para la Acreditación de Facultades o Escuelas de Medicina Humana” (CAFME 2013) [ 14 ], the national clinical practice guideline for obstetric emergency care in Peru [ 15 ], and the core clinical competencies in obstetrics and gynecology for undergraduate students in Australia and Canada [ 16 , 17 ].

The physician’s perception of their competence in managing the emergency was evaluated through the question: “I have the appropriate skills to perform these procedures during the SERUMS…”, with responses scored on a Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

To calculate the score for each emergency (preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, and sepsis), the scores obtained for each of the basic procedures were averaged. The final average was then categorized as “non-competent” (score less than four) or “competent” (score greater than or equal to four). The “self-perception of obstetric emergency competence” was obtained by averaging the scores for each individual emergency topic (preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, and sepsis) and was categorized as “not competent” (< 4 points) or “competent” (≥ 4 points).

Other variables

Other assessed variables were sex, age, marital status, previous health career, university, satisfaction of teaching during the gynecology/obstetrics internship rotation (thought the question: Was the clinical teaching [during medical visits, academic activities, shift changes, etc.] in the Gynecology-Obstetrics rotation excellent?), institution where the internship was held, and externship.

The externship is a one-year university program completed prior to the medical internship. Its objective is to integrate the knowledge of the four basic areas of medicine (medicine, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, and pediatrics) through hospital practices [ 18 ]. To construct this variable, we reviewed the university curricula for 2016 from each of the medical schools in Lima. Based on this information, we created a variable with two categories: those without externship and those with externship.

Statistical analysis

We used Stata v.15 software for statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed using absolute and relative frequency measures. To evaluate factors associated with self-self-perceived competencies in obstetric emergencies we used Poisson regression models, taking into account the university where participants graduated as a cluster. This enabled us to obtain prevalence ratios (PR) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). To construct the adjusted model, we identified potential confounders by analyzing causal diagrams.

We evaluated a total of 520 physicians, of which we excluded 41 who did not complete their medical studies at a university in Lima and 16 who did not complete their internship in 2016. Finally, we analyzed 463 recently graduated physicians, of whom 55.1% were male and 36.8% were aged between 25 and 26 years old, and 73.0% completed their medical studies at private universities. During their internship, 67.4% of the physicians worked in a hospital under the Ministry of Health in Peru, and 67.4% reported being satisfied with the teaching during their obstetrics and gynecology rotation. Only 20.48% of the included physicians completed the externship. Although 33.3% of the physician perceived themselves competent in the management of obstetric emergencies, when we evaluated for individual emergencies, 64.1%, 54.1%, and 35.0% of the physician perceived themselves competent with the management of sepsis, postpartum hemorrhage, and preeclampsia, respectively Table 1 .

In the crude model, we observed that the prevalence of self-perceived competence in managing obstetric emergencies was higher in the group that completed an externship (PR: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.15–1.79). This finding was also observed in the adjusted model (PR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.34–1.96). Furthermore, in the adjusted model, we found significant associations between self-perception of obstetric emergency competence and having completed a previous career in health (PR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.12–2.81), as well as having completed the gynecology and obstetrics internship rotation in EsSalud (PR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.31–1.68) Table 2 .

When we evaluated each of the obstetric emergencies, we found that for physicians who completed externships, the prevalence of self-perceived competence in managing preeclampsia (PR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.01–1.08) was higher compared to the group that did not complete an externship. This finding was consistent in the adjusted model (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.28–1.32). Similarly, we observed a statistically significant association between completing an externship and self-perceived competence in managing sepsis, but only in the adjusted model (OR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.03–1.33). However, we did not find a consistent significant association between completing an externship and self-perceived competence in managing postpartum hemorrhage Table 3 .

Competencies in obstetric emergencies

In Peru, the majority of recently graduated physicians begin their careers by participating in SERUMS at the primary level of care [ 5 , 19 ] in regions characterized by high vulnerability and a shortage of multidisciplinary staff [ 5 ]. As a result, these physicians need to possess the necessary knowledge and competencies to effectively manage prevalent conditions, including obstetric emergencies [ 8 ].

Our study identified that approximately one-third of recent medical graduates perceived themselves as lacking competence in managing obstetric emergencies. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Chile, where 60% of physicians self-perceived as a non-competent in obstetric management [ 20 ]. The high percentage of self-perception is likely due to shortcomings in medical education in Peru, where there is a disconnect between the primary care competencies taught in universities and the competencies needed for the workforce as postulated by the Ministry of Health [ 19 ]. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge that medical education has predominantly focused on inpatient settings, despite the fact that the practice of medicine primarily occurs in outpatient settings [ 21 ], especially at the beginning of the work career. This circumstance, compounded by restricted resources and logistical hurdles, results in physicians gaining their initial clinical experience in the most intricate and fast-paced healthcare environments, which presents a heightened level of challenge [ 21 ].

In Peru, the essential training for emergency management competence also primarily occurs within hospital settings [ 22 ]. This educational approach might have been impacted by the proliferation of medical colleges and the subsequent rise in number of students [ 23 ]. Consequently, a heightened concentration of students within healthcare institutions leads to a shortage of clinical settings for procedural training, a deficiency in available instructors, and constrained instructional hours [ 24 ]. This is a concerning situation, as practical healthcare training typically necessitates a maximum of one student per patient in emergency care scenarios [ 25 ]. With the notable growth of medical colleges, particularly in Lima, over the past decade [ 23 ] coupled with the substantial number of medical students present in clinical areas [ 26 ], there is a possibility that this established standard is not being upheld.

When we evaluated self-perceived competencies for each topic, we found that more than half of the participants perceived themselves as non-competent in postpartum hemorrhage management. This outcome is likely attributed to the fact that effective management of postpartum hemorrhage entails both pharmacological intervention and the accurate execution of maneuvers for placental removal [ 27 ]. These aspects can present increased challenges and demand more comprehensive training. Furthermore, given that postpartum hemorrhage demands prompt intervention due to its potential for rapid hemodynamic instability and maternal mortality [ 28 ]; certain healthcare facilities might not afford students the chance to manage this type of condition, consequently leading to a deficit in practical experience.

International experiences suggest that for the development of emergency competencies, students need clinical training with real cases supervised by experienced instructors [ 22 ]; Nevertheless, it’s equally vital to integrate simulation exercises, including hands-on practice of procedures like placental removal using models, virtual programs, and other educational tool [ 22 , 29 ], to increase the clinical practice and minimize the risk of poor results in obstetric emergency management. Inclusive, this teaching class can also be offered as an elective course at the beginning of the medical career, allowing students the opportunity to enroll in a quarter-long course focused on teaching and practicing common obstetric emergency procedures in the early stages of their careers, as reported in a previous study [ 30 ].

Associated factors

A higher proportion of physicians that self-perceived competent in general emergencies have done a university externships. Probably it is because the externship inserts the medical students in a clinical environment, entailing them to get competencies in real practice and direct observation [ 31 ]. This was corroborated by previous studies that reported results about the favorable impact of direct observation in the formation of procedural competencies [ 32 ] with good acceptance from students and teachers [ 33 , 34 ].

Although our study found a significant association between completing a university externship and self-perceived competencies in managing obstetric emergencies, it’s important to note that in the sub-analysis examining individual pathologies, this association was not observed in the context of postpartum hemorrhage management. This is probably because postpartum hemorrhage involves complex management [ 28 ], making it challenging to attain an optimal self-perception level for this competence even with a university externship. This result also suggests that obstetric competencies should be assessed individually, encouraging tailored learning strategies for each topic based on the disease’s characteristics and its management [ 35 ].

To ensure effective learning during university externships or internships, it’s essential to take into account the type of institution in which they are conducted, as each institution provides distinct clinical opportunities. This can result in an imbalance of the knowledge acquired between institutions. For instance, students who participate in externships at specialized obstetric institutions are likely to receive more focused teaching on this topic, with greater opportunities for obstetric procedural learning. This has been reported in studies conducted in the United States [ 22 ] and Iran [ 36 ], which recommend prioritizing clinical practices in specialized rooms or centers to enhance opportunities for patient attention and emergency procedures. Therefore, it is crucial to link externship implementation to continuous monitoring by the university, establishing indicators to evaluate procedural learning in each student (number of processes completed in each topic by each student) and designating a specified time for learning each basic competency in obstetrics.

Our study found that physicians who had previously completed a career in health had a higher prevalence of perceiving themselves as competent. This is not surprising as self-perception of competencies is closely linked to confidence [ 37 ] and therefore professionals with prior knowledge and experience would likely have greater confidence in managing diseases and subsequently a better self-perception of their abilities.

Additionally, our study revealed that the type of institution where the medical internship was completed was associated with self-perception of competencies. Previous studies conducted in Peru [ 38 ] and Brazil [ 39 ] have also reported the fundamental role of internships in the acquisition of skills in obstetrics and gynecology. However, our study only found a higher prevalence of physicians who perceived themselves as competent when they completed their medical internship at an EsSalud hospital. In Peru, internship institutions display notable disparities in logistic resources (such as teaching resources), clinical areas, and patient demand [ 40 ]. Our results are as expected, given the renowned reputation of EsSalud hospitals for their exceptional teaching performance, especially in the procedural aspects of obstetrics and gynecology [ 41 ]. Additionally, in Peru, gaining an internship placement at an EsSalud institution necessitates passing a knowledge examination and maintaining acceptable performance during undergraduate studies [ 42 ]. This requirement may contribute to students having a stronger knowledge base and, consequently, a heightened self-perception of their competencies.

It is important to note that self-perception of competencies may not necessarily reflect actual competencies, and therefore continuous monitoring and evaluation of skills acquisition through objective measures is crucial for ensuring quality medical education.

Limitations and strengths

Some limitations of our study must be taken into account. First, the sample was gathered through a non-probabilistic method, encompassing physicians who participated in a Peruvian national convention. This introduces a selection bias, potentially leading to a greater likelihood of including participants with a more positive self-perception and, consequently, an overestimation of the results. Nonetheless, our findings align consistently with prior studies conducted in comparable contexts in other countries [ 20 , 43 , 44 , 45 ] bolstering the certainty of the evidence.

Additionally, our evaluation of obstetric competencies relied on self-perception rather than direct assessment of clinical skills. While self-perception has shown to be a useful measure of self-efficacy, it may not necessarily reflect actual competence levels [ 46 ], which could potentially affect our results [ 37 ]. However, we believe that our findings remain informative, as self-perception is linked to both real knowledge and the interest to learn and improve one’s skills [ 47 , 48 ].

On the other hand, our study is among the first in the region to examine self-perceived competencies among physicians managing obstetric emergencies, providing important insights into the skills and knowledge levels of physicians in this field. Our findings highlight the need for interventions to improve obstetric emergency management, particularly given the high mortality rate associated with this condition in our context.

Our study found that having a previous health career, having performed the internship in EsSalud hospitals, and completing a university externship, were associated with a higher prevalence of self-perceived competence in obstetric emergencies among recently graduated physicians. These findings suggest that certain academic factors during the last years of study can be critical to improve the competencies or competence self-perception in physicians. Further studies are needed to confirm these results and identify other factors that may impact physicians’ competencies in this field.

Availability of data and materials

https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Database_BMC/22280695 .

Crosby J, Harden R. AMEE Guide No 20: the good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):334–47.

Article Google Scholar

New england journal of medicine. Massachusetts: NEJM Knowledge+ Team; c2017. What is competency-based medical education? Available from: https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/what-is-competency-based-medical-education/ . Citado 15 Abril 2019.

New england journal of medicine. Massachusetts: NEJM Knowledge+ Team; c2019. Exploring the ACGME core competencies: medical knowledge. Available from: https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/acgme-core-competencies-medical-knowledge/ . Cit 10 Abril 2019.

Mayca J, Palacios-Flores E, Medina A, Velásquez JE, Castañeda D. Percepciones del personal de salud y la comunidad sobre la adecuación cultural de los servicios materno perinatales en zonas rurales andinas y amazónicas de la región Huánuco. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2009;26(2):145–60.

Google Scholar

Ministerio de Salud. Evaluación de competencias a los profesionales médicos, obstetras y enfermeros del Servicio Rural y Urbano Marginal en Salud SERUMS. In: CONADIS, editor. Peru: MINSA; 2018. Available from: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/495952/442896876217965586520200124-18375-1azxgan.pdf?v=1579897968 .

Reyes E. «Allá es clínicamente así: saber llegar». De la formación a la práctica profesional médica. El Servicio Rural Urbano Marginal en Salud (SERUMS). 2011.

Ministerio de Salud del Perú. Estudio epidemiológico de distribución y frecuencia de atenciones de emergencia a nivel nacional 2010 - 2013. Perú: MINSA; 2013. Available from: https://repositorio.sis.gob.pe/handle/SIS/46 .

Quispe Chuizo M, Sánchez Mantilla RC. Manejo de las referencias y contrarreferencias de las pacientes obstétricas atendidas en el Centro de Salud de Urubamba, Cusco 2014. 2016.

Ministerio de Salud del Perú. Boletín Epidemiológico (Lima-Perú). In: Dirección General de Epidemiología, editor. Perú: MINSA; 2016. Available from: https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/boletines/2016/03.pdf .

Risco de Domínguez G. Diseño e implementación de un currículo por competencias para la formación de médicos. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2014;31:572–81.

Zafra-Tanaka JH, Hurtado-Villanueva ME, Saenz-Naranjo MDP, Taype-Rondan A. Self-perceived competence in early diagnosis of cervical cancer among recently graduated physicians from Lima, Peru. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0203778.

Dirección Regional de Salud Cusco. Cusco: MINSA; c2016. SERUMS. Available from: http://www.diresacusco.gob.pe/administracion/serums/serums.htm . Cit 11 Abril 2019.

Fescina R. DMB, Ortiz E, Jarquin D. Guías para la atención de las principlaes emergencias obstétricas. In: Centro Latinoamericano de Perinatología Salud de la Mujer y Reproductiva, editor. Uruguay: OPS; 2012. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/51029/9789275320884-spa.pdf .

Comisión de Acreditación de las Facultades y Escuelas de Medicina. Estándares mínimos para acreditación para facultades o escuelas de medicina. In: CAFME, editor. Perú: CAFME; 2003. Available from: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/3387194/Acreditación%20de%20facultades%20o%20escuelas%20de%20medicina%3A%20Ley%2C%20reglamento%2C%20estándares%20mínimos%20de%20acreditación%20y%20manual%20de%20procedimientos.pdf .

Ministerio de Salud del Perú. Guías de práctica clínica para la atención de emergencias obstétricas según nivel de capacidad resolutiva. In: MINSA, editor. Perú: MINSA; 2007. Available from: http://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/IMP/852_IMP198.pdf .

Pierides K, Duggan P, Chur-Hansen A, Gilson A. Medical student self-reported confidence in obstetrics and gynaecology: development of a core clinical competencies document. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:62.

Caccia N, Nakajima A, Scheele F, Kent N. Competency-based medical education: developing a framework for obstetrics and gynaecology. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2015;37(12):1104–12.

Gutiérrez Sierra M, Llosa Isenrich MPL. El programa de medicina en la Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2014;31:582–7.

Jimenez MM, Bui AL, Mantilla E, Miranda JJ. Human resources for health in Peru: recent trends (2007–2013) in the labour market for physicians, nurses and midwives. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):69.

Millan KT, Ercolano FM, Perez AM, Fuentes FC. Self perception of clinical competences declared by recently graduated physicians of the University of Chile. Rev Med Chile. 2007;135(11):1479–86.

Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:48–58.

Coates WC. An educator’s guide to teaching emergency medicine to medical students. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):300–6.

Nieto-Gutierrez W, Fernández-Chinguel JE, Taype-Rondan A, Pacheco-Mendoza J, Mayta-Tristán P. Incentivos por publicación científica en universidades peruanas que cuentan con escuelas de medicina, 2017. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2018;35:354–6.

Alva J, Verastegui G, Velasquez E, Pastor R, Moscoso B. Oferta y demanda de campos de práctica clínica para la formación de pregrado de estudiantes de ciencias de la salud en el Perú, 2005–2009. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2011;28:194–201.

Brando Moreno CR, Castellanos Ramírez JC. Aproximaciones a un estimativo de la capacidad para formar el talento humano en el campo de la salud en un centro médico académico. Universitas Medica. 2017;58(3). ISSN: 0041-9095 / 2011-0839.

Montenegro-Idrogo JJ, Montañez-Valverde R, Sánchez-Tonohuye J. Sobredemanda del campo clínico para estudiantes de medicina. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2012;29(1):155–7.

Ajenifuja KO, Adepiti CA, Ogunniyi SO. Post partum haemorrhage in a teaching hospital in Nigeria: a 5-year experience. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10(1):71–4.

Snelgrove JW. Postpartum haemorrhage in the developing world a review of clinical management strategies. Mcgill J Med. 2009;12(2):61.

Lima MFG, Pequeno AMC, Rodrigues DP, Carneiro C, Morais APP, Negreiros F. Developing skills learning in obstetric nursing: approaches between theory and practice. Rev Bras Enferm. 2017;70(5):1054–60.

van der Vlugt TM, Harter PM. Teaching procedural skills to medical students: one institution’s experience with an emergency procedures course. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(1):41–9.

Fagel BG. Medical student externship as an opportunity to expand the base of medical education. The viewpoint of the Student American Medical Association. JAMA. 1970;213(12):2059–61.

Erfani Khanghahi M, Ebadi Fard Azar F. Direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS) evaluation method: systematic review of evidence. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2018;32:45.

Shahgheibi S, Pooladi A, BahramRezaie M, Farhadifar F, Khatibi R. Evaluation of the effects of Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) on clinical externship students’ learning level in obstetrics ward of Kurdistan university of medical sciences. J Med Educ. 2009;13(1, 2):29.

Caughey JL Jr. The medical student externship: the viewpoint of the medical educator. JAMA. 1970;213(12):2061–2.

Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. UPCH: Perú; 2020. Malla Curricular 2020. Available from: https://famed.cayetano.edu.pe/medicina/malla-curricular?view=article&id=284&catid=32 . Citado 9 Nov 2020.

Akhlaghi MR, Vafamehr V, Dadgostarnia M, Dehghani A. Integrated surgical emergency training plan in the internship: a step toward improving the quality of training and emergency center management. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:60.

Bandura A. Self‐efficacy. In: The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. 2010. p. 1–3.

Nieto-Gutierrez W, Taype-Rondan A, Bastidas F, Casiano-Celestino R, Inga-Berrospi F. Percepción de médicos recién egresados sobre el internado médico en Lima, Perú 2014. Acta Med Peru. 2016;33:105–10.

Linhares JJ, Dutra BdAL, Ponte MFd, Tofoli LFFd, Távora PC, Macedo FSd, et al. Construction of a competence-based curriculum for internship in obstetrics and gynecology within the medical course at the Federal University of Ceará (Sobral campus). Sao Paulo Med J. 2015;133:264–70.

Alcalde-Rabanal JE, Lazo-González O, Nigenda G. Sistema de salud de Perú. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(suppl 2):s243–54.

Taype-Rondán Á, Tataje Rengifo G, Arizabal A, Alegría HS. Percepción de médicos de una universidad de Lima sobre su capacitación en procedimientos médicos durante el internado. An Facultad Med. 2016;77:31–8.

EsSalud. Perú: EsSalud; 2019. Internado Médico EsSalud. Available from: http://www.essalud.gob.pe/programa-de-internado-medico/ . Citado 02 Nov 2019.

Ceballos Morales A, Ibañez Gracia P, Pérez Villalobos C. Seguridad y destreza autoreportadas en la formación de competencias clínicas obstétricas en estudiantes de obstetricia. Rev Cuba de Educ Med Super. 2016;30(2):2.

Traore M, Arsenault C, Schoemaker-Marcotte C, Coulibaly A, Huchon C, Dumont A, et al. Obstetric competence among primary healthcare workers in Mali. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126(1):50–5.

Huchon C, Arsenault C, Tourigny C, Coulibaly A, Traore M, Dumont A, et al. Obstetric competence among referral healthcare providers in Mali. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126(1):56–9.

Dunning D. Chapter five - The Dunning-Kruger effect: on being ignorant of one’s own ignorance. In: Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 44. USA: Academic Press; 2011. p. 247–96.

Kaduszkiewicz H, Wiese B, van den Bussche H. Self-reported competence, attitude and approach of physicians towards patients with dementia in ambulatory care: results of a postal survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:54.

Galli N. How self-perceived knowledge, actual knowledge and interest in drugs are related. J Drug Educ. 1978;8(3):197–202.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Cesar Ugarte-Gil for its help during the writing of this paper.

This study was self-founded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Peru

Wendy Nieto-Gutierrez

Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Unidad de Investigación para la Generación y Síntesis de Evidencias en Salud, Lima, Peru

Alvaro Taype-Rondan

EviSalud – Evidencias en Salud, Lima, Peru

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All of the author participated in the recollection of the data, analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript, and contributed significantly to the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wendy Nieto-Gutierrez .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The primary study of the database was approved by the “Comité Institucional de Ética en Investigación del Hospital Nacional Docente Madre-Niño – HONADOMANI” (RCEI-40). Also, this secondary analysis was approved by the “Comité de Ética de la Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia” (CIE-UPCH).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

WNG and ATR have completed undergraduate studies at Universidad de San Martín de Porres. All of the authors have completed postgraduate studies at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nieto-Gutierrez, W., Taype-Rondan, A. Self-perceived competence in managing obstetric emergencies among recently graduated physicians from Lima, Peru. BMC Med Educ 23 , 876 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04854-5

Download citation

Received : 04 March 2023

Accepted : 07 November 2023

Published : 16 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04854-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Education, Medical

- Education, Medical, Undergraduate

- Internship, Nonmedical

- Pregnancy Complications (source: MeSH)

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Best Global Universities for Clinical Medicine in Peru

These are the top universities in Peru for clinical medicine, based on their reputation and research in the field. Read the methodology »

To unlock more data and access tools to help you get into your dream school, sign up for the U.S. News College Compass !

Here are the best global universities for clinical medicine in Peru

Universidad peruana cayetano heredia.

See the full rankings

- Clear Filters

- # 535 in Best Universities for Clinical Medicine (tie)

- # 948 in Best Global Universities (tie)

Dates & Pricing

The earlier you book, the more choice of available dates you'll have. Prices are based on double occupancy.

Trips include: All transfers, all lodging, guided trek, and most meals.

Trips do not include: Flights to and from Peru. We will book the flight for our clients on Day 9 from Cusco to Puerto Maldonado, which will be billed prior to the final payment and should be between $100 - $150 per person.

October 6 - 16, 2024

$6,250 per person

$789 Optional CME Cost (16 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™)

Available - Filling Quickly

October 5 - 15, 2025

Price per person coming soon!

Questions? Ready to reserve your spot? Speak to an expert at Bio Bio Expeditions - the award winning outfitter of this trip 1-800-246-7238

A few of the publications Bio Bio Expeditions has been featured in:

Testimonials From Your Colleagues

"This was a trip of a lifetime - excellent combination of medical education and education regarding the history, politics and culture of the region, botany and architecture. The hiking was superb, the food on the trail an unexpected pleasure, and the guides managed our time on the Inca Trail in such a way that we felt we were the only hikers on any given day."

Heidi Green, MD

"Absolutely the best meeting I have ever attended. Extremely useful information for any physician regardless of the ¬specialty. The talks were inspirational and motivating, and the ¬activities were icing on the cake."

John McAnulty, MD, Madison, WI.

"The CME trip to Peru was fantastic. Everything went smoothly. Piero (the head guide) is a superstar! He really looked out for the health and safety of everyone on the trip. This was definitely 5 star "first class" adventure travel."

Robert Derlet, MD

Faculty for the Inca Trail, Machu Picchu, & Amazon Rainforest

October 6-16, 2024.

David M. Fiore, MD

University of Nevada Reno, School of Medicine faculty since 1992. Lead faculty for the wilderness medicine program, including student resident wilderness medicine tracks and a wilderness medicine fellowship. Especially active in the worlds of whitewater and backcountry skiing, Board of Directors for the Sierra Avalanche Center since 2010. Multiple national and international publications and professional presentations on wilderness medicine. Physician and physician educator in Saipan, Myanmar and Bhutan.

COURSE CONTENT INCLUDES

- Altitude Illness

- Hypothermia

- Frostbite and Other Cold Injuries

- Environmental Heat Illness

- Traveler's Diarrhea, Giardia & Other Waterborne Wilderness Infections

- Surviving the Unexpected Night Out

- Lightning Injuries

- Improvised Medical and Trauma Care

- Management of Fractures and Dislocations

- Preparing for Foreign Travel

- Backcountry Medical Kits

- Wilderness Wound Management

- Patient Assessment in Wilderness Settings

- Wilderness Dermatology

- Marine Hazards & Envenomations

- Snake Envenomation

CME ACCREDITATION INFORMATION

"This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint providership of the Center for Emergency Medical Education and Wilderness and Travel Medicine. The Center for Emergency Medical Education is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians."

The Center for Emergency Medical Education designates this live activity for a maximum of 16 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits TM .

Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

This trip is planned, outfitted and conducted by Bio Bio Expeditions, or subcontractors arranged by Bio Bio Expeditions. Please note that Wilderness and Travel Medicine, LLC is responsible for the CME Educational content only. Wilderness and Travel Medicine reserves the right to change or substitute the faculty for any CME course without advance or prior notice to participants.

For more information or to register for this trip please call

Bio Bio Expeditions at 1-800-246-7238

Stay Informed

Email updates about exciting new CME locations, dates, conference, & specials. You’re free to opt out at any time.

Contact Wilderness Medicine

The National Conferences on Wilderness Medicine Phone: 1-844-945-3263 or 1-971-236-8088 Email: [email protected]

Adventure CME Destinations Contact Bio Bio Expeditions Phone: 1-800-246-7238 or 1-530-582-6865 Email: [email protected]

Follow Wilderness Medicine

Upcoming cme destinations by date.

Apr 1 - 11, 2024

Apr 25 - May 12, 2024

May 29 - June 2, 2024

June 8- 14, 2024

July 27 - July 31, 2024

July 29 - Aug 8, 2024

Sept 1 - 6, 2024

Sept 1 - 11, 2024

Sept 5 - 15, 2024

Sept 11 - 21, 2024

Sept 12 - 23, 2024

Sept 19 - 27, 2024

Oct 6 - 16, 2024

Oct 6 - 20, 2024

Oct 13 - 24, 2024

Oct 21 - Nov 3, 2024

Jan 27 - Feb 4, 2025

Jan 25 - Feb 1, 2025

Jan 29 - Feb 9, 2025

Feb 2 - 8, 2025

Mar 15 - 22, 2025

Apr 20 - 30, 2025

April 23 - May 10, 2025

Apr 25 - May 5, 2025

June 7 - 13, 2025

June 8 - 13, 2025

Aug 16 - 26, 2025

Aug 31 - Sept 10, 2025

Sept 10 - 20, 2025

Sept 28 - Oct 9, 2025

Oct 5 - 15, 2025

Oct 12 - 17, 2025

Oct 25 - Nov 7, 2025

[Perception of the gastroenterologist about the needs of continuing medical education in Peru]

Affiliations.

- 1 Departamento de Aparato Digestivo del HNERM - EsSalud. Lima, Perú.

- 2 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Lima, Perú.

- 3 Departamento de Aparato Digestivo del HNERM - EsSalud. Lima, Perú; Profesor, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Lima, Perú; Profesor, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Peruana Ciencias Aplicadas. Lima, Perú.

- 4 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Lima, Perú; Médico gastroenterólogo, Clínica El Golf - SANNA. Lima, Perú.

- PMID: 30860507

Objective: To determine the perception of the gastroenterologist about the needs of continuing medical education (CME) in Peru.

Material and methods: Cross-sectional and descriptive study. The sample was not probabilistic. A survey was applied to the gastroenterologists members of the Society of Gastroenterology of Peru. The questionnaire was developed based on the "Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Educational Needs Assessment Report" with a Likert scale of 5 points (1 = not necessary and 5 = indispensable). The average of the scores obtained in each of the 33 items of the clinical, endoscopic and learning methods areas was determined.

Results: There were 75 participants and the average age was 43.40 years (SD ± 10.22 years). The place of work was mainly Lima (68%) and the majority (50.67%) had a service time of less than 5 years. The perception of educational needs in the clinical area was higher for gastric cancer (4.37 ± 0.87) and colon cancer (4.37 ± 0.83); in the endoscopic area were polypectomy (4.15 ± 0.95) and emergency techniques (4.13 ± 0.99). The main learning methods for gastroenterologists were attendance at congresses (4.29 ± 0.83) and endoscopic workshops (4.19 ± 1.06).

Conclusions: The perception of the gastroenterologist surveyed on the needs of CME was mainly on gastric and colon cancer issues. Most of them considered congress attendance as the main learning method.

- Attitude of Health Personnel*

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Education, Medical, Continuing*

- Gastroenterology / education*

- Middle Aged

- Needs Assessment

- Self Report

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Barbara Fraser reports. Efforts to set more rigorous standards for licensing physicians in Peru have been left in limbo by administrative and legal challenges, while the future of the country's new medical school licensing body is also uncertain. The issues have come to the fore following a 2021 study, which found that 43% of medical school ...

PAMS unites Peruvian and American volunteers and organizations to offer quality healthcare to underserved people in Peru and enhance the education for Peruvian medical students and doctors. ... Your donation helps support medical missions and medical education in Perú. PAMS is a volunteer organization that relies on the generosity of people ...

In Peru, medical school programs typically last 7 years. The first two or three years cover basic sciences, while the following years focus on clinical sciences. ... Accreditation drives teaching: evidence-based medicine and medical education standards. BMJ Evid.-Based Med., 26 (2021), pp. 216-218, 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111491.

Peru", said Giuston Mendoza-Chuctaya, the lead author of the study. In 2018, the Medical College of Peru (Colegio Médico) reached an agreement with the Peruvian Association of Medical Schools to make a pass grade on the examination a condition for licensing doctors to practice in Peru. Before that, a medical school diploma was sufficient.

Lima, Peru. SBU Advisor: Luis A Marcos, MD ... For Graduate Medical Education (Residency and Fellowship Programs) (631) 216-9094. Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. 101 Nicolls Road Health Sciences Center, Level 4 Stony Brook, NY 11794-8434. Students Admissions

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on medical care and medical education in Peru. In response, the Peruvian American Medical Society (PAMS), a charitable medical organization based in ...

In Peru, medical students' study for 7 years, thus the study period of the population included went from 2010 to 2016. Persons that finish high school are able to start medical school regardless their age. It is not needed that medical students publish papers for medical licensing. ... clinical, public health/epidemiology, medical education). ...

Expanding Medical Education for Local Health Promoters Among Remote Communities of the Peruvian Amazon: An Exploratory Study of an Innovative Program Model. ... we evaluated the development and community utilization of a CHW training program in the Loreto province of Peru. Additionally, a community-oriented training model was designed to ...

Objectives Peer-assisted learning (PAL) is a supportive strategy in medical education. In Peru, this method has been implemented by few universities. However, there are no consistent studies evaluating their acceptability by medical students. The objective of this study was to evaluate the perception of medical students about PAL in five Peruvian universities. Results A total of 79 medical ...

Abstract. Medical education aims at excellence in the training of health professionals. Thus, virtual education arises from the difficulty of access of many students to educational centers ...

Cender U. Quispe-Juli & Carlos Jesús Aragón-Ayala Health informatics in medical education in Peru: are we ready for digital health? An Fac med. 2022;83(4):369-370 370

Peru faces various health challenges, including high rates of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, dengue fever, and malaria. Chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, also pose significant health burdens. Addressing these challenges requires ongoing efforts in disease prevention, healthcare education, and improved ...

Radiology and Nuclear medicine 9. Sports Medicine 2. Surgery 12. Urology 3. Veterinary 4. Virology 12. Below is the list of 20 best universities for Medicine in Peru ranked based on their research performance: a graph of 310K citations received by 29.3K academic papers made by these universities was used to calculate ratings and create the top.

For Peruvian medical students, this review will give them a locus of control on what they can improve in regard to ENAM scores: mainly self-regulated learning strategies, using high-utility study techniques, and focusing more on undergraduate medical education as it is the main predictor of ENAM scores.

The medical education landscape has undergone significant changes in recent years [], with a shift towards competency-based learning [2, 3], which could oscillate depending on the necessity of each country.In underdeveloped countries such as Peru, there is a pressing need to develop a broader range of skills for general physicians, particularly in the area of obstetrics, due to a shortage of ...

Germany. India. Italy. Japan. Netherlands. See the US News rankings for Clinical Medicine among the top universities in Peru. Compare the academic programs at the world's best universities.

The unmet neurosurgical need has remained patent in developing countries, including Peru. However, continuous efforts to overcome the lack of affordable care have been achieved, being neurosurgical missions one of the main strategies. We chronicle the humanitarian labor of organizations from high-income countries during their visit to Peru, the ...

disease 20 19 ( COVID- 1 9) is a highly c ontagious disease that represen ts an emergency worldwide. On May. 22, 2020 w e counted 4,99 3,47 0 con rmed cases and 3 27 ,738 deaths among 188 c ...