Putting the Theory Back in 'Music Theory'

Jeremy Day-O'Connell

Music Department, Skidmore College

E-mail: [email protected]

Received June 2019

Peer Reviewed by: Gretchen Foley, Jennifer Shafer

Accepted for publication September 2019

Published September 2, 2020

https://doi.org/10.18061/es.v7i0.7368

What is music theory? This foundational question is scarcely even broached in textbooks and classrooms, and that fact has allowed naive views to persist among students and teachers alike. This state of affairs has also perpetuated an unfortunate disconnectedness in institutional and disciplinary conceptions of music theory, including through the devaluing of music theory "fundamentals." In this essay, I argue for a purposeful centering of theory as an intellectual enterprise; I describe a subtle reformulation of elementary music theory that celebrates its epistemological essence and methodological complexities; and I identify meta-theoretical issues that can be seamlessly introduced early in the music theory curriculum without compromising the delivery of content itself. I begin by describing a classroom discussion prompt that motivates a working definition of "theory" in general, which in turn can be leveraged throughout the music theory curriculum. I then describe several interactive lessons that highlight the theoretical underpinnings of certain venerable topics in tonal music. The study of music theory, even from the very first rudiments, is thus transformed from a stern rite of passage mired in dry technicalities, into an expansive intellectual endeavor—reminding students that they themselves are theorists, both in class and in life.

Keywords: music theory, pedagogy, epistemology, intervals, harmony, rhythm and meter

Introduction: theories of theory

What is theory.

What is music theory, and why is it important? In my experience, these core philosophical questions are seldom addressed by teachers of music theory, who, after all, must attend to a daunting body of content and skills. Admittedly, the latter question—the "why" of music theory—might occasionally inspire meaningful, albeit limited and too often private, pedagogical reflection. But oddly, the more foundational first question—the "what" of music theory, and consequently the "how"—is scarcely even broached in music theory textbooks and classrooms.

This disinclination to consider the foundations of music theory has allowed naive views to persist among students and teachers alike. For many students (and even teachers), "theory" connotes only the most uninspiring and technical necessities of musical study, such as notation, scales, chords, and other fundamentals. On the other hand, for many professional music theorists, "theory" comprises only the most advanced, rigorous, and sophisticated topics, such as Schenkerian, neo-Riemannian, or pitch-class theories. They are both wrong.

I offer this essay as a corrective to such widespread and small-minded conceptions. I will describe a subtle pedagogical reformulation of elementary "music theory" that celebrates its true theoretical essence and methodological complexities. I will resituate music theory as a bona fide epistemological enterprise akin to other sorts of theory, thereby buttressing curricular efforts aimed at the integration of knowledge across the disciplines. Importantly, this approach easily supplements the content of a traditional "theory" curriculum without compromising the teaching of that content itself: indeed, I will describe opportunities to engage with numerous venerable topics in tonal music while centering the theoretical underpinnings of each. Such an enterprise not only fosters a more realistic, reflective, and accurate understanding of music theory as a discipline but also enriches students' appreciation of music theory and its resonance with other fields. The study of music theory—even from the very first rudiments—is thus transformed from a stern rite of passage mired in rules and technicalities, into an expansive intellectual endeavor, adding yet another educational component to music theory's manifold musical benefits (which I will also briefly enumerate at the end of this essay).

An illustrative tale: the case of the hidden theory

To motivate this recontextualization of theory, I begin by offering my students the following tale—part allegory, part shaggy-dog story.

Sally Sophomore returns to campus after a weekend away and finds that the laptop she left in her dorm room won't boot up. She is puzzled, as the computer worked just fine before she left campus. After a moment's thought, she develops a theory: perhaps her roommate had carelessly run down the battery. But upon further investigation, Sally finds that the computer is plugged in and appears to be fully charged. A moment later another theory occurs to her: maybe a virus is to blame. But her attempts to boot in "safe mode" are similarly unsuccessful, so she rules out that idea as well. Finally, Sally becomes aware of a large sticky spill across the keyboard and the unmistakable smell of Cherry Garcia ice cream. Just as she begins to make sense of this, her roommate rushes in with a package under her arms:

"Sally, I'm so sorry! I can explain: we had a party while you were gone, and things got a little out of hand. Before we knew it, a pint of ice cream had melted all over your laptop and wrecked it. I should have kept a better eye on things. I'm really sorry." Presenting the package, she adds, "But don't worry: I just bought you a new computer—the next higher model, actually—and I had all of your files transferred. It's all OK now. I hope you can forgive me."

Sally is relieved, and touched—her roommate didn't have to go to all that trouble and expense to rectify such an innocent mistake. "It's just like her," Sally muses, affectionately: "She's a middle child!" And the two happily embrace, before settling down to work on their music theory homework.

The moral: theory versus hypothesis

Where is "theory" in this tale? Did you spot it? I like to lead students in an in-class discussion, exploring the difference between the casual, popular use of the word "theory" and the strict, more formal use of that word. Students will easily identify two examples of the former: Sally's "theories" that the computer had a dead battery or was stricken by a virus. Such ideas are more properly called "hypotheses"—guesses about a particular state of affairs. A proper theory, on the other hand, may be defined as a conceptual framework that helps make sense of some broad set of phenomena. A hypothesis will prove to be either true or false; a theory, on the other hand, is a way of seeing, for which truth and falsehood are largely beside the point.

Students can be pressed to discern the proper "theory" in the tale above, but it is one that had nothing to do with solving the mystery: the concept of "middle child." This "birth order" theory of personality emerged in the early twentieth century and was popularized more recently by Kevin Leman, whose The Birth Order Book (2009) contains a telling subtitle: "Why you are the way you are." Sally might have said of her roommate, "It's just like her: she's a Libra." That too is a theory of personality, even if its theoretical primitives are very different: instead of "eldest child," "middle child," and "youngest child," astrological theory postulates personality categories based on the month of one's birth.

From here, students can be encouraged to brainstorm and/or research other theories. And in each case, the theory can be shown to have certain basic elements: at the very least, a scope of study and a set of theoretical concepts and categories. Economic theory, for instance, studies the behavior of agents in a market economy, and to that end it invokes such concepts as supply, demand, choice, utility, etc. Likewise for countless other theories, such as various psychological theories, political theory, feminist theory, game theory, aesthetic theory, and of course a multitude of scientific theories—including, notably, obsolete scientific theories like Aristotelian physics or medieval alchemy, each of which were simply the best means of conceptualizing physical phenomena until they were replaced by ones with more explanatory power. Non-majors, double-majors, students in liberal-arts institutions, and broad-minded musicians of all stripes, will happily furnish examples of theories from other disciplines and fields of inquiry. (And some students may be inspired to delve deeper into meta-theory, via such seminal works as Popper 1935/2002 , Kuhn 1962/2012 , or Thagard 1992 .) Music students who breezily speak of "theory class" or "theory homework" rarely consider that music theory, too, is such an example.

A well constructed theory is a powerful thing; where there is understanding, a theory is surely at play. As Leonard Meyer wrote, "Like air, theories may be unsubstantial; but, as with air, we can't live and act without them" ( Meyer, 1998 , p. 18 n. 45). In the case of music theory, it might seem that intervals, scales, chords, meter, form, and other basic elements are uncontroversial, even self-evident, "facts" to be memorized. But students should learn that even the most seemingly obvious music-theoretical constructs are laden with abstraction and artifice. True theory (unlike the hypotheses of a clever fictional detective) needn't be surprising or esoteric. And by the same token, students should recognize that some portions of their "theory" studies fall strictly outside the realm of true theory: for instance, reading clefs and deciphering transposing instruments, however valuable and challenging they may be, are matters of mere notation, not theory.

What follows are some specific ways of leveraging these initial explorations, to help students put the theory back in "theory."

Theorizing in the theory classroom

I will now focus on four meta-theoretical issues that can be seamlessly introduced early in the music theory curriculum: explanatory power, listening as theorizing, theory-building , and symbolic representation . I will discuss these with an emphasis on their relevance to familiar elementary musical topics, each one furnished with musical illustrations. The issues have been chosen both for their general epistemological applicability and for their practicality as touchstones throughout a student's musical studies.

Explanatory power: measuring intervals

Since theory is, as I wrote earlier, "a way of seeing, for which truth and falsehood are largely beside the point," a theory should be judged according to its explanatory power —its efficacy in coherently describing its subject and facilitating fresh insight. The classic tradeoff between theoretical simplicity and explanatory power is well illustrated by a heavily theorized (it would seem, even excessively theorized) elementary musical concept: interval. The concept of interval also offers a perfect opportunity for a "devil's advocate" approach that helps our students dig deeper as they begin to imagine themselves as theorists.

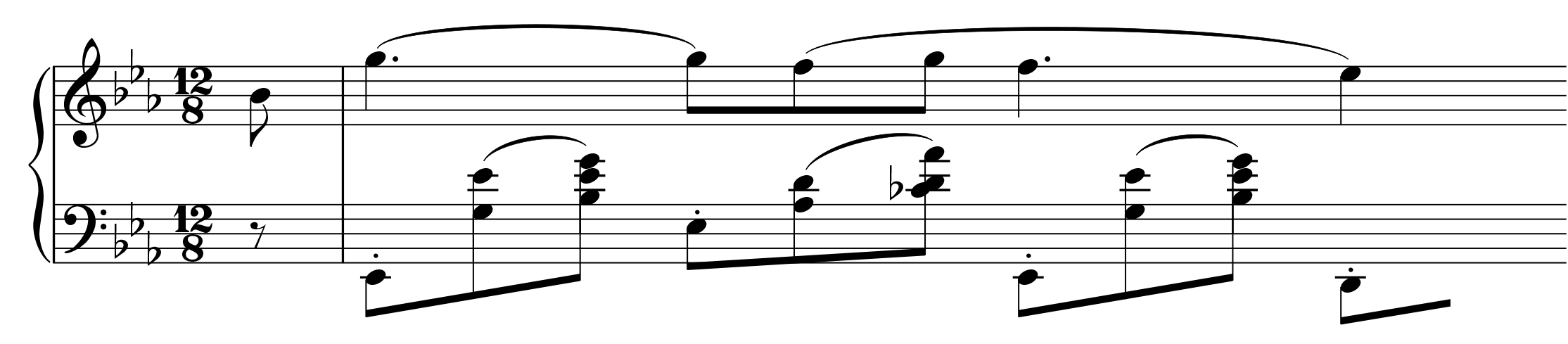

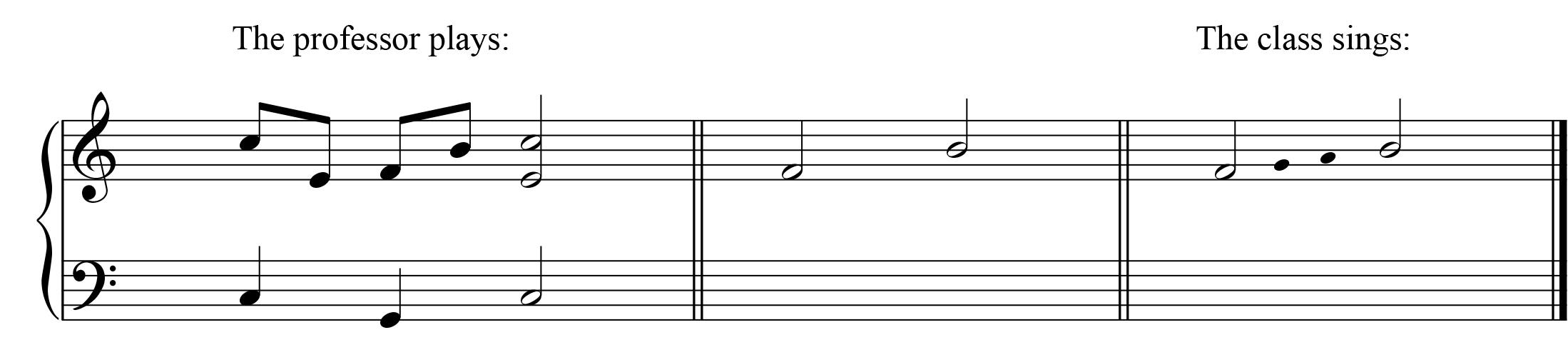

The theory of interval in tonal music postulates categories of distance (second, third, fourth, etc.) that are modified by categories of quality (major, minor, perfect, augmented, diminished). As soon as I introduce this system, I (disingenuously) encourage my students to bristle against such an apparent theoretical contortion and to long for the abundantly straightforward, one-dimensional metric of semitone distance. I lead them to confront the question, Why is semitone distance alone insufficient to fully describe musical space? To answer that question, I invoke the curious reality of musical context, in the form of two simple melodies (Figure 1): the opening of Chopin's Nocturne in E♭, op. 9 no. 2 (Figure 1a), and a subsidiary theme from Haydn's Symphony no. 104 Finale (Figure 1b). I isolate the interval B♭–G (having established a suitable E♭-major context, per the first excerpt) and then its enharmonic equivalent A♯–G (having established an alternate B-minor context, per the second excerpt), easily illustrating at the piano the very different sounds of these two intervals. Students discover that the tempting but theoretically naive conceptualization of semitone distance—9 semitones in either case—elides what is most musically essential about the two situations. By contrast, our theoretically sophisticated concept of interval precisely captures the crucial distinction between a major sixth and a diminished seventh—the one harmonious and unexceptional, the other dissonant and striking.

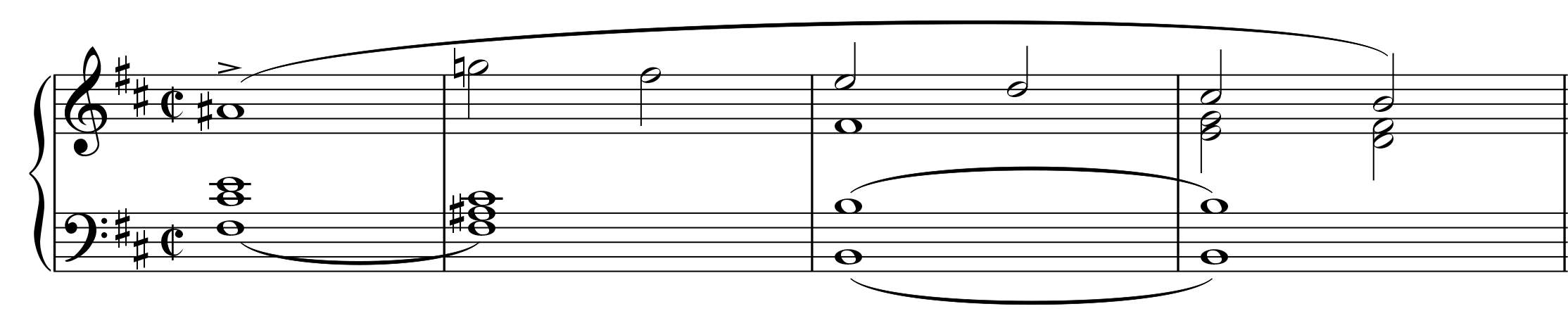

I then invite the students to sing the two intervals in question, in each case vocally tracing a stepwise path from note to note (Figure 2). Given sufficient tonal context, students will naturally sing B♭–C–D–E♭–F–G in the first case (six notes, hence a "sixth," Figure 2a) and A♯–B–C♯–D–E–F♯–G in the other case (seven notes, hence a "seventh," Figure 2b). The difference between the two intervals, which can otherwise strike some students as senselessly pedantic or doctrinaire, becomes "real," even embodied. A similar aural trick involving ambiguous tritones is perhaps even more compelling—see Figure 3. In contrast to the dispassionate yardstick of semitone distance, the theoretical contrivance of "interval" proves to be robust and human, a triumph of "sense-making." Explanatory power must always prevail.

Figure 1. Two excerpts illustrating the enharmonically equivalent interval (B♭–G versus A♯–G).

(a) Chopin, Nocturne in E♭, op. 9 no. 2

(b) Haydn, Symphony no. 104, Finale , m. 84

Figure 2. A directed "sung analysis" of the intervals in Figure 1.

(a) Major 6th, after Figure 1a.

(b) Diminished 7th, after Figure 1b.

Figure 3. An analogous "sung analysis" of a chameleonic tritone (F–B versus F–C♭).

(a) Augmented 4th.

(b) Diminished 5th.

Listening as theorizing: hearing rhythm and meter

In the prior illustration, and ideally throughout the music theory curriculum, theory is tested against the listener's real-time experience of music. Such aural verification underscores the crucial truth that successful theorizing mirrors human cognition itself. And indeed, some theorizing even happens automatically: to operate in a culture is to subscribe to existing theories, most of which are acquired without effort or even awareness. It could be said that music theory's raison d'être is to make plain the implicit conceptualizations that any competent listener brings to the act of listening. The enharmonic interval demonstration makes that point vividly (and for many students, astonishingly): not only is the difference between a major sixth and a diminished seventh real, but it's a difference that the ears knew even before the mind was taught. "Your ears are smarter than you thought they were," I tell my students at such moments. Rhythm and meter provide further exquisite demonstrations of the psychological inescapability of such structured (i.e., theory-driven) hearing— listening as theorizing .

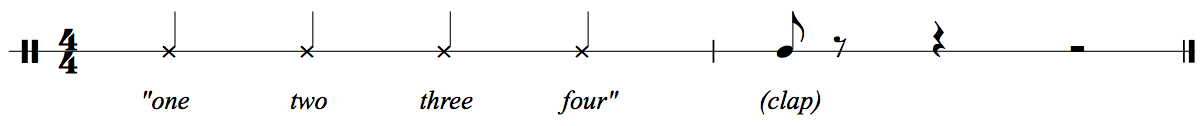

Even the simplest musical stimulus—a lone hand-clap—inevitably acquires meaning through the structures assumed by a listener. The difference between Figures 4a and 4b arises not from the stimulus itself (the "music") but from the existence of conceptual categories—an implicit theory of meter. In this case, the listener infers "beat" versus "off-beat" through a real-time application of those categories—which is to say, through implicit musical analysis. As Goethe insisted, "With every intent glance at the world, we theorize." ( Goethe 1810 , Vorwort; thus quoted, prominently, in Schenker [1935] 2001 , p. 3)

Students must also confront the limits of such theorizing, as when they come to terms with musical situations that are rhythmically challenging, under-determined, and/or unfamiliar. I like to ask students to tap their toes to the opening of Leila Pinheiro's " Chega de Saudate "; it is a task that many students find difficult or impossible, but repeated and directed listening can help them to orient their rhythmic understanding to the stylistically idiosyncratic metrical framework. Even more challenging and ear-opening is the rhapsodic 7/8 of Karolina Goceva's " Mojot svet " (Macedonia's 2007 Eurovision song entry): students who have a hard time finding the down-beat will marvel at an informal live performance during which an audience of (possibly inebriated) amateurs spontaneously entrain to the non-isochronous meter through participatory clapping.

Figure 4. The same rhythmic stimulus (a hand-clap) in two contexts.

Such seemingly rudimentary concepts as beat, off-beat, and down-beat, often dispensed with unceremoniously in the first weeks of a theory curriculum, should instead be honored as the cognitive miracles that they are—profoundly meaningful and profoundly constructed.

Theory-building: confronting anomalies in harmonic analysis

As a tool for understanding, theory must be responsive to the full range of specimens under its purview. For that reason, successful theories are not ordained but rather developed: theory-building is a dialectic process of testing and refining a theoretical system in light of a fulsome set of data. The earlier enharmonic demonstration hinted at this process (as did the beat-finding exercises, in a different sort of way); here I will more explicitly invite my students to partake in theory-building, in the course of a pedagogical turn from chordal identification to full-fledged harmonic analysis.

Tonal harmonic theory postulates a very limited set of harmonic entities—a handful of triads and seventh chords—that are easily learned. (Compare the systematic completeness of pc-set theory; the difference between these two theories reflects the differing demands of the respective repertories.) In an early exercise in chord identification, I present my students with a homophonic choral texture from Mozart's Requiem , the Hostias , which provides abundant examples of various chord roots, qualities, and inversions. My instructions are simple: "On every beat, indicate the chord using 'fakebook' notation. When the chord fails to conform to our inventory of chord-types, simply place an X."

There are indeed plenty of pesky X's, which would seem to besmirch what are some of the most sonically appealing moments in the passage. I used to avoid such inconvenient distractions by micro-managing my choice of repertoire—or else by summarily dismissing them ("Never mind … we'll get to that later"). But in the context of a "theory-aware" pedagogy, I have come to embrace these moments as important teaching tools. I find it stimulating (and fun) to feign exasperation: "Our theory of chords isn't all that good, is it? It has nothing useful to say about many simultaneities in this apparently straightforward piece of music!" A closer look—and listen—will suggest satisfying ways of accounting for those anomalous simultaneities, of course, and thus will emerge the concept of the non-harmonic tone. As my students and I work our way toward a richer understanding of harmony and counterpoint—figure and ground, structure and elaboration, tension and resolution—theory-building comes to the fore.

Symbolic representation: data compression and theoretical priorities in chord shorthand

Finally, it behooves us to consider another common metatheoretical issue: the use of symbolic representation and notation . Theory necessarily simplifies our world, and that simplification often goes hand in hand with exigencies of notation. Chord shorthand is a case in point, and a telling one.

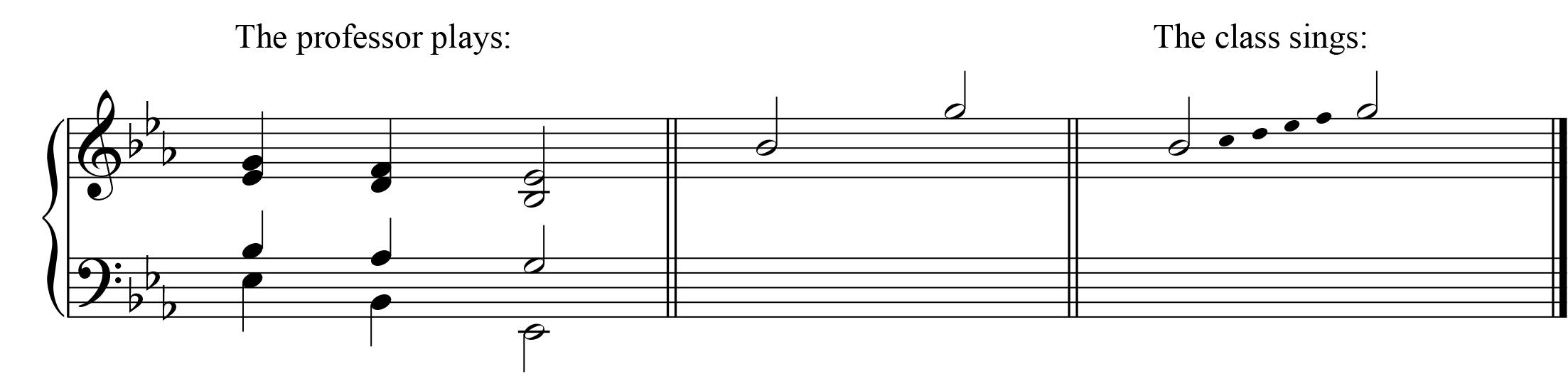

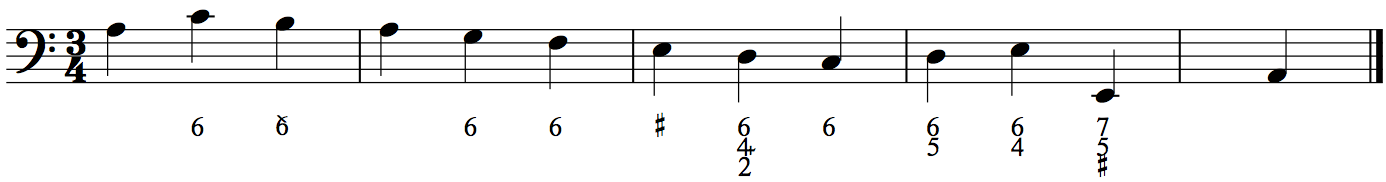

Students find it provocative to learn that an 18th-century keyboardist or fretboardist would have faced a decoding challenge analogous to that faced by a modern-day reader of a jazz or pop "fakebook." The specifics of those two notational traditions, however, reveal how particular theoretical priorities and affordances shape symbolic systems. Students can compare the "native" chordal shorthand schemes for an early-18th-century solo sonata and a mid-20th-century popular ballad, discovering the conceptual traces embodied in each (Figure 5). Baroque figured bass emphasizes intervals and voice-leading within a particular key signature (Figure 5a), whereas modern fakebook notation, agnostic with respect to key, emphasizes instead chord structures in isolation (Figure 5b). These systems consequently elicit very different cognitive work from the performer. (Indeed, the most adept musician of three hundred years ago would have scarcely had a concept of chord root, the 'bread and butter' of even the most casual dorm-room guitarist today.)

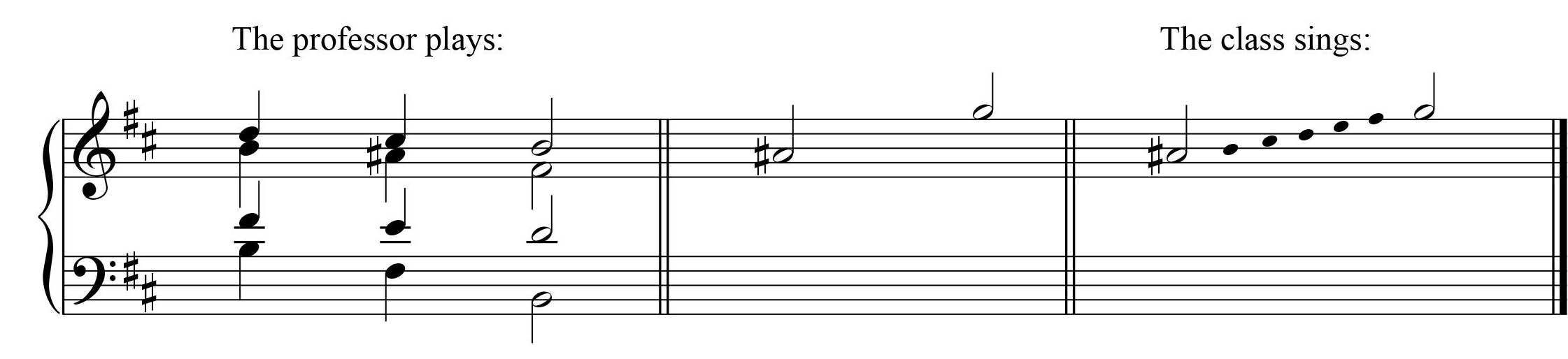

An anachronistic swapping of those notational systems helps to recover otherwise hidden elements of the harmonic picture: a hypothetical fakebook to the sonata, for instance (Figure 6a), immediately reveals chord roots and qualities undisclosed by the figured bass, while a figured bass to the ballad (Figure 6b) immediately foregrounds the salient out-of-key chord in m. 4, inconspicuous in the fakebook notation.

Figure 5. Two notational traditions of chordal shorthand.

(a) Figured bass for Handel Sonata op. 1 no. 7, iii, mm. 1-5.

(b) Fakebook chords for "What a Wonderful World" (Thiele/Weiss), mm. 1-4.

Figure 6. Hypothetical anachronistic chordal shorthand for Figures 5a and 5b.

(a) Fakebook chords for Handel Sonata op. 1 no. 7, iii, mm. 1-5.

(b) Figured bass for "What a Wonderful World" (Thiele/Weiss), mm. 1-4.

Those two symbolic systems correspond to "prescriptive" realms of harmonic theory. By contrast, Roman numerals generally represent tonal harmonic structures with a more "descriptive" purpose in mind. Here too, much is at stake as we develop our notational details and decisions. The explanatory power of the nomenclature "V/V," for instance, points to very different structural aspects of that chord than does the more tempting and straightforward "II ♯ ". Similarly, nomenclature looms large with respect to that familiar pedagogical bugbear, the cadential six-four chord: whatever may be a teacher's stance on the question (of the chord's function as tonic versus dominant), s/he would be remiss not to draw attention to the ways that one's theoretical commitments shape (and are shaped by) choices of analytical notation (" I 4 6 – V " versus " V [ 4–3 6–5 ] "). And in reflecting on their own intuitions about the cadential six-four, students will see that this descriptive nomenclature (no less than prescriptive nomenclature) ultimately represents a compromise in an attempt to capture the fullness of musical meaning.

Conclusion: learning goals in the theory classroom

I began this essay with the question, "What is theory, and why is it important?" Having explored some approaches to the first half of that question, I will conclude with a brief discussion of the second half, affirming the many and varied educational benefits of music theory. The study of music theory, needless to say, helps students to better understand the mechanics of music and the construction of musical works. It enables students to cogently talk about and write about music while exposing them to a large body of repertoire. By fostering intimacy with the details of musical construction, it leads to a deeper appreciation of the artistry of composers and performers—an insight into great minds. Music theory also offers many frankly practical benefits to musicians, in the form of musicianship: it facilitates the learning and memorization of new pieces; it is indispensable to the conductor or, indeed, to any ensemble musician; it informs composition and can be applied to the art of improvisation; and it shapes a performer's interpretation of a piece. More generally, music theory stands to foster a broader disposition of attentiveness: in a world marked by passivity and saturated by distraction, music's great gift is that it invites us to engage with pure sound, and theory's great gift is that it helps us to engage.

Note, however, that this prodigious list of educational payoffs relates to the categories of analysis and musicianship . In the course of those essential and deeply rewarding educational experiences, I find it valuable to also remind students of the intellectual marvel that theory is unto itself, and to remind students that they themselves are theorists, both in class and in life. Reclaiming the theory in what we do as teachers and students will only add a unique layer of richness to students' musical formation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sarah Day-O'Connell, Gretchen Foley, and Jennifer Shafer for their careful reading and helpful suggestions.

Bibliography

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. 1810. Zur Farbenlehre. Tübingen: Cotta. https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.414424.39088007009129

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 2012. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions . 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (First edition published 1962.)

- Leman, K. 2009. The Birth Order Book: Why You Are the Way You Are . 2nd ed., rev. Grand Rapids: Revell.

- Meyer, L. B. 1998. "A Universe of Universals," Journal of Musicology , 16(1): 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.1998.16.1.03a00010

- Popper, Karl. 2002. The Logic of Scientific Discovery . New York: Routledge. (First German edition published 1935.)

- Schenker, H. [1935] 2001. Free Composition (Der freie Satz) , trans. and ed. Ernst Oster. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon.

- Thagard, Paul. 1992. Conceptual Revolutions . Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691186672

Return to Top of Page

About the Journal

Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy presents short essays on the subject of student-centered learning, and serves as an open-access, web-based resource for those teaching college-level classes in music.

Make a Submission

Beginning with Volume 7 (2019), Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license unless otherwise indicated.

Volumes 1 (2013) – 6 (2018) were published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License unless otherwise indicated.

Volumes 1–6 are openly available here .

Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy is published by The Ohio State University Libraries.

If you encounter problems with the site or have comments to offer, including any access difficulty due to incompatibility with adaptive technology, please contact [email protected] .

ISSN: 2689‐2871

Open Music Theory - Version 2

(2 reviews)

Mark Gotham

Kyle Gullings

Chelsey Hamm

Publisher: Oklahoma State University

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Judith Ofcarcik, Assistant Professor, James Madison University on 11/20/23

This book can be used for a traditional theory curriculum but also covers pop music, jazz, and orchestration. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This book can be used for a traditional theory curriculum but also covers pop music, jazz, and orchestration.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book has been prepared by a team of teacher-scholars who are all experts in the subject.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The text incorporates current trends in music theory pedagogy, including the incorporation of examples by underrepresented composers, but not in a faddish way.

Clarity rating: 5

The text of the book is very clear and the examples are well-marked.

Consistency rating: 5

Even though it was written by multiple authors, the chapters are consistent and work well together.

Modularity rating: 5

We use this book in a modular way, and it works very well.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Organization is clear, and the table of contents makes for quick navigation to relevant chapters.

Interface rating: 5

Both I and my students find this book very easy to read.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

All of the writing is grammatical.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The book is not culturally insensitive, and it also includes helpful hints for German and French speakers who might be reading it using an automatic translation tool.

This book is extremely comprehensive--it could easily support an entire undergraduate music theory curriculum. Not only does it have a huge amount of content (both text and examples), it also contains worksheets that can be used in and out of class. It is the only online-only music theory textbook that can compete with traditional print texts. We have used it at my institution for several years and it has been a fantastic textbook for instructors, undergrads, and grad students looking to review specific topics.

Reviewed by William O'Hara, Assistant Professor, Gettysburg College on 11/5/22

OMT2 offers thorough coverage of current topics in music theory, and can easily serve as a textbook for fundamentals courses, standard undergraduate theory sequences, and introductions to post-tonal theory. Not all of its chapters are complete... read more

OMT2 offers thorough coverage of current topics in music theory, and can easily serve as a textbook for fundamentals courses, standard undergraduate theory sequences, and introductions to post-tonal theory. Not all of its chapters are complete (some are short, or lack sample homework assignments), but the authors promise continued revision and expansion, and the book is probably the most extensive OER currently available in music theory. It offers very little material for sight-singing/ear training, but instructors can easily supplement with other free resources (such as freemusicdictations.net) or paid ear training books.

The book seems to be high quality and without errors.

OMT2 combines a variety of current approaches to the field: a traditional (yet relevant and modern) course in diatonic and chromatic harmony, up-to-date research on counterpoint and form, and a digestible introductions to post-tonal and twelve-tone theory. It also includes units on popular music and jazz. The book takes diversity and inclusion seriously, incorporating both canonical names and historically marginalized composers throughout its chapters, workbook, and anthology.

The book is clear and accessible, and flows in a logical and conversational style. It is also full of musical examples, many of which can be clicked on and listened to for immediate clarification and reinforcement. As in any music theory textbook, there is a great deal of technical terminology, but mouse-over links on many terms produce pop-up windows with glossary entries, making the jargon easy to understand.

Where relevant, the book uses terminology clearly and consistently throughout, although its sections are written by multiple authors, and address topics that are separate enough that vocabulary does not always overlap.

The book is broken into short, digestible chapters, which instructors could easily assign and re-order as necessary.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

OMT2 includes all the resources necessary to teach a fundamentals course in music theory, as well as common undergraduate courses in tonal theory (including basic diatonic harmony, modulation, and chromatic techniques), and post-tonal theory. The content is organized in broad topics (diatonic harmony, chromatic harmony, form, popular music, jazz), and many instructors will find themselves mixing and matching sections from these different units as they assemble their syllabus: a little bit of harmony, some basic formal archetypes, some popular music, back to diatonic harmony, and so forth.

Interface rating: 4

OMT2 comes in numerous forms, both online and PDF/EPUB formats. I highly recommend the html, web-based forms, which use an expandable table of contents and section directories. The book's interactive resources, musical examples, YouTube videos, and other pieces of media are best experienced online. Its pdf/print versions are somewhat lacking in layout and visual style, and they unfortunately omit the media resources that students will find the most useful and engaging.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

OMT2 is well-written and well-edited, though contains the occasional typo.

OMT2 makes a strong effort to prominently include musical examples by women and composers of color, and features them prominently in its structure rather than including them as afterthoughts. The book also includes chapters on popular music and jazz, making its content and coverage a bit more accessible and relevant to students. There is still more that could be incorporated (topics in world music analysis are absent, for instance), but the book clearly strives for accessibility and inclusion, and will help students and instructors to engage with current discussions in the field of music theory.

The original Open Music Theory (https://github.com/openmusictheory) appeared in 2014. A collaborative effort by music theorists Bryn Hughes, Brian Moseley, and Kris Shaffer, the book brought the idea of open educational resources to prominence within the discipline of music theory. Open Music Theory Version 2, which features significant contributions by more than half a dozen scholars, builds on the original text with a mountain of new content, moving beyond the “prose-y lecture notes” of the original to offer a resource that is nearly ready to serve as the core of an undergraduate music theory curriculum. Among the most notable additions are extensive annotated musical examples (which were sparse in the original), even more interactive demonstrations and practice modules, an accompanying workbook, and a growing set of annotated links that function as a distributed score anthology.

At its best moments, OMT2 is a fully fledged textbook, easily able to take its place alongside (or, as is often the goal of OERs, to more affordably replace) any of the field’s canonical undergraduate books. It includes content that is appropriate for introductory “Fundamentals” classes, for the three- or four-semester-long sequence of tonal theory classes offered by most institutions, and for the post-tonal theory courses that often end such sequences, or serve as advanced electives. The book also offers some resources that would be useful in advanced counterpoint or analysis courses, though it does not offer enough content to serve as a sole textbook for those topics. Beyond traditional theory and the Classical repertoire, the book offers an excellent chapters on pop-rock harmony (which turn the original OMT’s already-useful unit into a thorough and well-developed resource) and a new chapter on jazz theory. In recent years, such units have appeared (in some form) more and more often in undergraduate courses, and OMT2 might provide the resources necessary to convince interested instructors to take the leap and incorporate them into their own teaching. The book also emphasizes diversity and inclusion, offering strong representation of historically marginalized composers, both in its main body chapters and particularly in its supplemental materials.

The “Fundamentals” section is highly detailed and well-illustrated, offering an accessible introduction to staff notation, rhythm and meter, scales and chords, and other basic topics. It also includes a series of YouTube videos by the chapter author (Chelsey Hamm), helping it to stand as a self-study resource for students who may be preparing for a music theory entrance exam. OMT2 also offers chapters on diatonic harmony (including harmonic function and prolongation, embellishing tones, up through tonicization and modulation) and chromatic techniques that run the gamut from basic chromatic chords (Neapolitans, augmented sixths) through altered dominants, Neo-Riemannian progressions, and fully diminished sevenths). The counterpoint chapter includes not only traditional species instruction and some resources (though not a complete manual) for imitation and fugue, but also more current approaches based on galant schema theory—most notably a concise and very useful guide to common schemas, categorized by their function (opening gambits, sequences, and so forth).

The “Form” chapter might be the best exemplar of OMT2’s ecumenical and modern approach to its reference material. The chapter covers basic concepts such as motive and subphrase, up through periods and sentences, and on to full-movement forms like sonata and rondo. Sensibly, the authors draw from both of the discipline’s most popular recent treatises on form, William Caplin’s Classical Form (1998) and James Hepokoski & Warren Darcy’s Elements of Sonata Theory (2006). OMT2 draws on the strengths of each book, building a theory of phrases up through Caplin’s writings, and then offering a clear and useful digest of Sonata Theory when the time comes to study complete movements. Gathering these resources together without trying to hew to a single approach or reinvent the wheel leads to a chapter which closely resembles how many professional theorists think and talk about form amongst themselves, and offers undergraduates a window onto the current state of the field rather than attempting to distill the parts of the sonata into some simpler form, or attempting to construct a single formal system that can accommodate all levels of phrase and form.

Open Music Theory 2 comes in multiple formats, including EPUB (for e-readers such as the Kindle), a digital-first PDF, and a PDF intended for printing. Perhaps its best and most useful format, however, is simply the HTML format on the text’s website. Online, OMT2 benefits from hyperlinks between chapters and mouse-over glossary entries that quickly introduce or clarify technical terms. Introductory chapters abound with examples in interactive notation (powered by MuseScore), which students can click on and listen to. Later chapters embed PDF scores for perusal, and most of the book’s sections end with links to the book’s own harmony anthology, its workbook, and resources from around the internet. Compared to this, the PDF format leaves out much of OMT2’s dynamic appeal. The PDF versions exclude media examples and interactive modules, replacing them with nondescript boxes that instruct readers to look online. While some instructors who use OERs have them printed and bound for students, I would caution against this approach with OMT2. In its PDF form, the book is nearly 1100 pages, and is laid out much more like a printed website (with large, double-spaced text and mile-wide margins) than a typeset book. While its prose passages wind up the perfect size when printed two pages per sheet, side by side, many of the illustrations end up unreadably small. So while it might be useful for a student or an instructor to have an archival pdf to which they can refer when internet access is unavailable, Open Music Theory Version 2 is best experienced on its website, in HTML format. This format honors the authors’ intentions toward accessibility too; the foreword notes that the text is meant to be legible to screenreaders, and the online version is undoubtedly the best way to take advantage of that commitment.

Another interesting aspect of OMT2 is the book’s “Harmony Anthology,” a resource based on contributing author Mark Gotham’s Open Score Lieder Corpus. As its name suggests, the collection is based on a broad body of art songs, mostly from the nineteenth century. The collection is extensive and diverse, presenting music by Johannes Brahms, Cecile Chaminade, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Fanny Hensel, Johanna Kinkel, Franz Schubert, Clara and Robert Schumann, and others. It makes use of links to the Internet Score Library Project (IMSLP) to provide complete scores for the included works, and often points to multiple examples of a given concept within the same work. Unfortunately, the Harmony Anthology is somewhat limited: like some other aspects of the book, it is incomplete, and it tends towards the kinds of advanced topics that might be encountered in a third-semester theory class (including augmented sixth chords, augmented triads, mode mixture, and Neapolitan chords). Unlike some anthologies of musical examples, however, the noted phenomenon is clearly identified by measure number, making it ideal for instructors who want to collect potential examples quickly. If and when it is eventually made more comprehensive, OMT2’s harmony anthology will be a truly exceptional resource. A parallel anthology of rhythmic and metric examples is similarly promising, though even less complete, serving only as a collection of interesting and suggestive examples for analysis.

OMT2 is explicitly a work in progress, and its team of authors promise continued updates (though not, notably, during the school year when the book might be in active classroom use). While many sections are complete, others are less developed; towards the second half of some units, assignments are marked “coming soon,” and there is a varied collection of chapters marked “in development” at the end of the book. These promise greater coverage of sight-singing; new topics that are often addressed in undergraduate theory but not always present in textbooks (like hypermeter); and more advanced topics that might be suitable for form & analysis or a proseminar setting (such as “metrical dissonance”). It already offers strong coverage of commonly taught music theoretical topics, and an extensive resource of example that serves as a useful supplement to other resources already available in print and online. As its authors continue to develop and revise it, OMT2 will continue to become ever more useful, and even more attractive, for both instructors and students.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- Statement on Spotify Usage

- Instructor Resources

- Für Deutschsprachige

- I. Fundamentals

- II. Counterpoint and Galant tSchemas

- IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation

- V. Chromaticism

- VII. Popular Music

- VIII. 20th-and 21st-Century Techniques

- IX. Twelve-Tone Music

- X. Orchestration

- Chapter in Development

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Open Music Theory Version 2 (OMT2) is an open educational resource intended to serve as the primary text and workbook for undergraduate music theory curricula. As an open and natively-online resource, OMT2 is substantially different from other commercially-published music theory textbooks, though it still provides the same content that teachers expect from a music theory text.

OMT2 has been designed inclusively. For us, this means broadening our topics beyond the standard harmony and atonal theory topics to include fundamentals, musical form, jazz, pop, and orchestration. And within those traditional sections of harmony and atonal theory, the authors have deliberately chosen composers who represent diverse genders and races. The book is accessible. And perhaps most importantly, the book is completely free and always will be.

The text of the book is augmented with several different media: video lessons, audio, interactive notated scores with playback, and small quizzes are embedded directly into each chapter for easy access.

OMT2 introduces a full workbook to accompany the text. Almost every chapter offers at least one worksheet on that topic. Some chapters, especially in the Fundamentals section, also collect additional assignments that can be found on other websites.

Version 2 of this textbook is collaboratively authored and edited by Mark Gotham, Kyle Gullings, Chelsey Hamm, Bryn Hughes, Brian Jarvis, Megan Lavengood, and John Peterson.

About the Contributors

Contribute to this page.

Modal and Chromatic Harmony

This category explores alternative harmonic systems beyond the traditional major and minor keys. It covers modal harmony, such as Dorian and Mixolydian, as well as chromaticism and extended chord structures.

Modal and Chromatic Harmony Essay Topics

- The Evolution of Modal Harmony in Western Music: Tracing the historical development and transformations of modal harmony from ancient Greek music to contemporary compositions.

- Chromaticism as a Catalyst for Musical Innovation: Examining how the introduction of chromatic harmonies revolutionized Western music and led to new compositional techniques and expressive possibilities.

- Modal Interchange: Exploring the concept of modal interchange and its application in creating rich harmonic textures and tonal ambiguity in various musical genres.

- Chromaticism in the Romantic Era: Analyzing the prominent use of chromatic harmonies in the Romantic period and its impact on emotional expression and tonal exploration.

- Modal Harmonies in Folk Music Traditions: Investigating the modal harmonies and tonal characteristics in folk music from different cultures and regions around the world.

- Chromatic Voice Leading in Jazz Harmony: Exploring advanced chromatic voice leading techniques and substitutions used in jazz harmony and improvisation.

- Modal Harmony in Contemporary World Music Fusion: Analyzing the integration of modal harmonies from different cultural traditions in contemporary world music fusion, highlighting the blending of tonalities.

- Chromaticism and Expression in the Music of Debussy: Examining the use of chromatic harmonies and tonal ambiguity in the compositions of Claude Debussy and their contribution to the Impressionist movement.

- Modal Chord Progressions in Rock Music: Investigating the use of modal chord progressions in rock music, exploring their role in creating unique tonal colors and moods.

- Chromatic Harmony in the Music of the Second Viennese School: Analyzing the highly chromatic and dissonant harmonies in the compositions of Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern.

- Modal Harmony in Sacred Choral Music: Examining the modal harmonies and tonalities in sacred choral compositions, such as Gregorian chant and Renaissance motets.

- Chromaticism and the Blues: Analyzing the use of chromatic harmonies and "blue notes" in the blues genre, exploring their expressive qualities and influence on subsequent musical styles.

- Modal Harmony in Film Music: Investigating the use of modal harmonies and tonalities in film scores to evoke specific moods, settings, and cultural contexts.

- Chromatic Voice Leading in Baroque Counterpoint: Exploring the intricate chromatic voice leading techniques employed in Baroque contrapuntal compositions, including fugues and canons.

- Modal Jazz: Analyzing the modal harmonies and improvisational approaches in modal jazz compositions, with a focus on modal jazz pioneers like Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

- Chromaticism in Post-Romanticism: Examining the heightened chromaticism and harmonic complexity in post-Romantic compositions, such as those by Gustav Mahler or Richard Strauss.

- Modal Harmonies in Traditional Indian Classical Music: Investigating the modal harmonies and raga systems in traditional Indian classical music and their role in improvisation and composition.

- Chromatic Harmony in Contemporary Pop Music: Analyzing the use of chromatic harmonies, chord progressions, and modulation techniques in contemporary pop music, exploring their impact on catchy melodies and emotional impact.

- Modal Implications in Minimalist Music: Exploring the modal implications and tonal centers in minimalist compositions, focusing on the repetitive structures and tonal ambiguity.

- Chromaticism and Symbolism in 20th-Century Music: Examining the use of chromatic harmonies and tonal symbolism in 20th-century compositions, exploring the connection between harmony and emotional or philosophical concepts.

- Modal Harmony in Jazz Fusion: Analyzing the fusion of modal harmonies with jazz improvisation and other musical genres in jazz fusion compositions.

- Chromatic Voice Leading in Contemporary Classical Music: Investigating the use of complex chromatic voice leading techniques in contemporary classical compositions, highlighting their role in harmonic exploration.

- Modal Harmonies in Indigenous Music Traditions: Exploring the modal harmonies and tonal systems in indigenous music traditions, emphasizing their cultural significance and musical expression.

- Chromaticism in Experimental Music: Analyzing the use of extreme chromaticism, microtonal intervals, and unconventional harmonic structures in experimental music compositions.

- Modal and Chromatic Elements in Cross-Cultural Musical Exchange: Investigating how modal and chromatic harmonies are integrated in cross-cultural musical exchanges, examining the fusion of different tonal systems and harmonic languages.

Contemporary Music Techniques

This category focuses on modern and avant-garde approaches to composition. It covers techniques such as serialism, aleatory (chance) music, electronic music, and spectralism, providing insight into innovative musical practices.

Contemporary Music Techniques Essay Topics

- Extended Techniques in Contemporary Instrumental Music: Exploring the use of unconventional playing techniques and sounds on traditional instruments in contemporary compositions.

- Sampling and Collage Techniques in Electronic Music: Analyzing the manipulation and recontextualization of sampled sounds and musical fragments in contemporary electronic music production.

- Microtonality in Contemporary Music: Investigating the use of microtonal intervals and alternative tuning systems in contemporary compositions, and their impact on harmonic and melodic expression.

- Live Electronics and Interactive Performance: Examining the integration of electronic instruments, real-time processing, and interactive technologies in contemporary live performances.

- Algorithmic Composition: Analyzing the use of algorithms and computer programming in the creation of musical structures, melodies, and harmonies in contemporary compositions.

- Minimalism and Repetitive Structures: Exploring the minimalist movement and its emphasis on repetitive musical structures, gradual transformations, and rhythmic patterns in contemporary music.

- Noise and Sound Art: Investigating the exploration of noise, unconventional sounds, and the blurring of boundaries between music and sound art in contemporary compositions.

- Graphic Notation and Indeterminacy: Analyzing the use of graphic notation and indeterminate elements in contemporary compositions, allowing performers to interpret and shape the music within certain parameters.

- Electroacoustic Music: Examining the combination of electronic sounds and acoustical instruments, as well as the manipulation of recorded sounds, in contemporary electroacoustic compositions.

- Spectralism: Investigating the spectralist movement and its focus on the analysis and manipulation of sound spectra in contemporary compositions.

- Vocal Techniques in Contemporary Choral Music: Analyzing extended vocal techniques, vocal improvisation, and experimental approaches to choral music in contemporary compositions.

- Live Coding and Algorithmic Improvisation: Exploring the practice of live coding, where performers code and manipulate algorithms in real-time to generate and shape musical material during live improvisations.

- Indeterminacy and Chance Operations: Examining the incorporation of chance procedures and indeterminate elements in composition, allowing for aleatoric and unpredictable outcomes in contemporary music.

- New Notation Systems: Analyzing innovative notation systems and graphical representations used in contemporary compositions, expanding traditional musical notation to capture new musical ideas.

- Hybrid Genres and Fusion: Investigating the blending of musical styles, genres, and cultural influences in contemporary compositions, such as jazz fusion, world music fusion, or classical crossover.

- Spatialization and Surround Sound: Exploring the use of multi-channel audio systems and spatialization techniques to create immersive sonic experiences in contemporary music performances and installations.

- Post-Minimalism and Eclecticism: Analyzing the post-minimalist movement and its incorporation of diverse musical elements, styles, and techniques in contemporary compositions.

- Timbral Exploration and Extended Instrumental Techniques: Investigating the exploration of timbre, sound textures, and unconventional instrumental techniques in contemporary compositions.

- Live Performance and Interactive Multimedia: Examining the integration of live performance with interactive multimedia elements, such as video projections, motion tracking, or sensor-based technologies.

- Hybrid Instrumentation and Ensemble Configurations: Analyzing the use of hybrid instrumental setups and unconventional ensemble configurations in contemporary compositions, expanding the sonic possibilities and instrumental interactions.

- Soundscapes and Environmental Music: Investigating the composition of soundscapes and environmental music, using field recordings and ambient sounds to create sonic narratives and immersive experiences.

- Improvisation and Structured Improvisation: Examining the role of improvisation and structured improvisational frameworks in contemporary music, allowing performers to actively shape the music in real-time.

- Interdisciplinary Collaborations: Exploring collaborations between composers, musicians, visual artists, dancers, and other disciplines in creating integrated multimedia performances and installations.

- Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Music: Analyzing the use of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies to enhance musical experiences, creating interactive and immersive virtual environments.

- Conceptual and Process-Based Composition: Investigating conceptual approaches to composition, where the emphasis is placed on the underlying ideas, processes, and conceptual frameworks driving the musical creation.

Analysis of Music History and Styles

This category examines music theory within the context of different historical periods and musical styles. It explores the theoretical principles and characteristics of various genres, such as Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and 20th-century music.

Analysis of Music History and Styles Essay Topics

- The Evolution of Western Classical Music: A comprehensive analysis of the major stylistic periods and developments in Western classical music, from medieval to contemporary.

- Comparative Analysis of Baroque and Classical Music Styles: Contrasting the characteristics, forms, and aesthetics of the Baroque and Classical periods in music history.

- Nationalism in Music: Analyzing the influence of national identity and cultural heritage on the development of musical styles and compositions in different countries and regions.

- The Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Music: Exploring the socio-cultural changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution and their influence on musical styles, instruments, and performance practices.

- Analysis of the Romantic Period: Examining the characteristics, themes, and innovations of the Romantic era in music, focusing on composers such as Beethoven, Chopin, and Wagner.

- The Development of Jazz Styles: Tracing the evolution of jazz music from its roots in African-American communities to the various subgenres and styles that emerged throughout the 20th century.

- Modernism and Avant-Garde in Music: Analyzing the experimental and boundary-pushing tendencies of modernist and avant-garde composers, exploring their innovative approaches to harmony, form, and notation.

- Analysis of Impressionist Music: Investigating the unique qualities, techniques, and impressionistic aesthetics in the compositions of Debussy, Ravel, and other impressionist composers.

- The Influence of Folk Music on Classical Compositions: Examining how folk music traditions and melodies have influenced classical composers and shaped their compositional styles.

- Analysis of the Expressionist Movement in Music: Exploring the emotional intensity, dissonance, and unconventional harmonies in the compositions of expressionist composers, such as Schoenberg and Berg.

- The Influence of African and African-American Music on Popular Music Styles: Analyzing the impact of African and African-American musical traditions on the development of popular music genres, including blues, rock, and hip-hop.

- Analysis of Minimalist Music: Examining the repetitive structures, gradual transformations, and minimalist aesthetics in the compositions of minimalist composers like Steve Reich and Philip Glass.

- The Development of Opera Styles: Tracing the evolution of opera styles from Baroque opera seria to the innovations of the Romantic and modern periods, analyzing key composers and their contributions.

- The Influence of World Music on Contemporary Compositions: Investigating the incorporation of world music elements and styles in contemporary compositions, highlighting the cross-cultural influences and musical fusion.

- Analysis of Film Music Styles: Examining the evolution of film music styles and techniques, from the early silent film era to the diverse soundtracks of contemporary cinema.

- The Impact of Technology on Music Production and Styles: Analyzing the influence of technological advancements, such as recording techniques, synthesizers, and digital production tools, on the creation and evolution of musical styles.

- Analysis of Pop Music Styles: Exploring the characteristics, trends, and innovations in popular music genres and subgenres, including pop, rock, R&B, and electronic dance music (EDM).

- The Development of Ballet Music: Tracing the history and stylistic evolution of ballet music, from the Baroque court ballets to the collaborative works of composers and choreographers in the 20th century.

- Analysis of Nationalistic Movements in Music: Examining the emergence of nationalistic music movements and the exploration of national identity in compositions from different countries, such as Russian, Czech, or Finnish music.

- The Influence of Latin American Music on Global Styles: Analyzing the impact of Latin American musical genres, rhythms, and instruments on global music styles, including salsa, bossa nova, and tango.

- Analysis of Contemporary Art Music: Examining the diverse approaches, techniques, and philosophies in contemporary art music compositions, including aleatoric music, spectralism, and post-minimalism.

- The Development of Sacred Music: Tracing the evolution of sacred music styles and genres, from Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony to contemporary sacred compositions.

- Analysis of Electronic Music Styles: Exploring the characteristics and subgenres of electronic music, including techno, house, ambient, and experimental electronic compositions.

- The Influence of Eastern Musical Traditions on Western Music: Investigating the impact of Eastern musical traditions, such as Indian classical music or Japanese traditional music, on Western compositions and styles.

- Analysis of Protest Songs and Political Music: Examining the role of music as a vehicle for social and political commentary, analyzing protest songs and politically charged compositions throughout history.

Music theory serves as a vital foundation for musicians, composers, and enthusiasts alike, offering a rich tapestry of knowledge and understanding. By delving into the fundamentals of music theory, exploring the intricacies of harmony, melody, counterpoint, form, orchestration, analysis, counterpoint and fugue, modal and chromatic harmony, contemporary techniques, and the vast expanse of music history and styles, we gain deeper insights into the language of music. Through these 25 essay topics, we have uncovered a myriad of possibilities for further exploration and research. Whether you are a student, a musician, or simply an appreciator of music, may this article inspire you to dive deeper into the fascinating realm of music theory and its profound impact on the creation and interpretation of music throughout history and across genres.

- Advertisers

- Agents and Vendors

- Book Authors and Editors

- Booksellers / Media / Review Copies

- Librarians and Consortia

- Journal Authors and Editors

- Licensing and Subsidiary Rights

- Mathematics Authors and Editors

- Prospective Journals

- Scholarly Publishing Collective

- Explore Subjects

- Authors and Editors

- Society Members and Officers

- Prospective Societies

- Open Access

- Job Opportunities

- Conferences

Journal of Music Theory

- For Authors

For information on how to submit an article, visit submission guidelines .

Academic Editor: Richard Cohn

Founded by David Kraehenbuehl at Yale University in 1957, the Journal of Music Theory is the oldest music-theory journal published in the United States and has been a cornerstone in music theory’s emergence as a research field in North America since the 1960s. The journal is edited by a consortium of music-theory faculty at Yale, where it is housed in the Department of Music. The Journal of Music Theory fosters conceptual and technical innovations in abstract, systematic musical thought and cultivates the historical study of musical concepts and compositional techniques. The journal publishes research with important and broad applications in the analysis of music and the history of music theory as well as theoretical or metatheoretical work that engages and stimulates ongoing discourse in the field. While remaining true to its original structuralist outlook, the journal also addresses the influences of philosophy, mathematics, computer science, cognitive sciences, and anthropology on music theory.

Read Online

Subscribers and institutions with electronic access can read the journal online.

- Buy an Issue

- Related Sites

- Abstractors & Indexers

- Advertising

- Online Access

- Institutional Pricing

- Additional Information

Music and Dance (65:1)

Journal of Music Theory 56:2 (56:2)

Journal of Music Theory 56:1 (56:1)

Journal of Music Theory 55:2 (55:2)

Journal of Music Theory 55:1 (55:1)

Journal of Music Theory 54:2 (54:2)

Cavell's "Music Decomposed" at 40 (54:1)

Journal of Music Theory 53:2 (53:2)

Journal of Music Theory 53:1 (53:1)

Journal of Music Theory 52:2 (52:2)

Essays in Honor of Sarah Fuller (52:1)

Partimenti (51:1)

Journal of Music Theory 50:2 (50:2)

Fiftieth Anniversary Issue (50:1)

- Go to read.dukeupress.edu/my-account/register . (Please ignore the message "Already have a Duke University Press account?" if your previous account was created before November 20, 2017.)

- Complete the form to activate your access. Enter your customer number. You can find your customer number on the mailing label of the journal or on the renewal notice. If you are unable to find your customer number, please contact Customer Service .

- Click “Register.” You should now have access to your journal.

More advertising information can be found on our Information for Advertisers page . To reserve an ad or to submit artwork, email [email protected] . No insertion is required. Please specify in which Duke University Press journal your ad should appear.

- Also Viewed

- Also Purchased

A Kiss across the Ocean

Making Value

Together, Somehow

Old Town Road

Get Shown the Light

Black Diamond Queens

Modern Language Quarterly

Public Culture

The Philosophical Review

An Analysis of Music Theory Synthesis Essay

The theory of Music analysis starts in two major dimensions- the “five levels” and across the “three main domains”. According to Hanninen (7), sonic, contextual and structural are the three domains in musical theory.

A domain, as used in music theory and analysis, is an area of musical discourse, experience or activity about a certain piece of music. It also refers to a number of musical ideas or phenomena being studied. Thus, there are three domains in this category- the contextual domain, the sonic and the structural domains.

To begin with, the Sonic domain is denoted as “S” and includes all the psychoacoustic facets of a given music piece. In this case, each note is conceived as a bundle of attributes of “S”. In this way, it allows the analyst to track down the activities of a multiple “S” dimension independent of each other and in a concurrent manner.

The organization of “S” in individual musical segments progress towards larger units and is indicated by differences as well as disjunctions. For instance, where there is a large difference in attribute values such as pitch and timbre, greater disjunctions and stronger boundaries are likely to be created between units of a musical piece.

According to Hanninen (31), organization of “S”, structural organization and associative organization make the three basic facets of musical organization in musical theory.

Secondly, the domain contextual, denoted as “C”, is used to recognize the workings of such features of music as association, repetition and categorization of a piece of music. Contextual domain, as the name suggests, describes the importance of a context of music in the formation of an object as well as its identity.

For instance, it provides an indication of the segments (objects) of music that are permeable and immersed through interaction with contexts. In domain “C”, the theory shifts its focus from isolation of segments to a new concept in which segments are grouped into associations. In addition, it focuses on the identification of a number of contexts that encroach into the objects of music in order to shape the sound in a given manner.

In “C” domain, repetition is considered as a non-static aspect and an active force in the process of forming the object. Thus, Hanninen (23) argues that association of units is the rationale behind segmentation. This mechanism focuses mainly on association between groups of notes, although it invokes some attributes of the “S” domain of individual notes.

Thirdly, the theory emphasises on the structural domain, denoted as “T”, which provides an indication of active reference to the theory of musical syntax (structure). The musical analyst has a role of choosing or developing the “H”.

It recommends the guides as well as segments in addition to conferring how musical events are interpreted. Hanninen (52) has shown that the theory has two major components- theoretical entities (HE) and frameworks (HF). They are drawn from other musical theories such as the “12-tone” theory and Schenkerian theory.

In conclusion, the three domains of musical theory (“S”, “C” and “T”) are important in the analysis of musical pieces. For instance, the “S” and “C” domains are active, although domain “C” is virtually active.

Thus, they show a complementation of strategies in human cognition. On the other hand, the “T” domain is different from the first two domains in that it can be activated or deactivated according to the analyst’s interest and the piece of music being analyzed.

Works Cited

Hanninen, Dora . A Theory of Music Analysis . Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2004. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, July 4). An Analysis of Music Theory. https://ivypanda.com/essays/an-analysis-of-music-theory/

"An Analysis of Music Theory." IvyPanda , 4 July 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/an-analysis-of-music-theory/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'An Analysis of Music Theory'. 4 July.

IvyPanda . 2019. "An Analysis of Music Theory." July 4, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/an-analysis-of-music-theory/.

1. IvyPanda . "An Analysis of Music Theory." July 4, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/an-analysis-of-music-theory/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "An Analysis of Music Theory." July 4, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/an-analysis-of-music-theory/.

- Sound and Space: Sonic Experience

- Starbucks and Sonic Corporations Expansion Strategies

- Sonic Slippage Project: Experimental Films

- Sonic Drive-in: Customer Service Communication

- Sonic Automotive and Starbucks Companies' Service Marketing

- Ultra-Sonic Engineering Corporation's Organisational Design

- Advertising Creative: Design Your Own Advertising Creative

- McDonald's Company Acquisitions and Mergers

- The Role of the Senses in Religious Practice

- Classical and Rock Music Genres

- The Grounds of popularity of Jepsen’s Song "Call Me, May Be?"

- Brahms: Clarinet Sonatas and Clarinet Quintet

- Baritone Voice as Primo Uomo in Mozart’s Operas

- The song "Simple Gifts"

- How Folk Songs Change the Idea of America

- Welcome to Eastman

- Mission and Vision

- Eastman Strategic Plan

- Community Engagement

- Awards and Recognition

- Equity and Inclusion

- Offices & Services

- Undergraduate

- Contact Admissions

- Faculty Listing

- Faculty Resources

- Chamber Music

- Composition

- Conducting & Ensembles

- Jazz Studies & Contemporary Media

- Music Teaching and Learning

- Music Theory

- Organ, Sacred Music & Historical Keyboards

- Strings, Harp, & Guitar

- Voice, Opera & Vocal Coaching

- Woodwinds, Brass & Percussion

- Beal Institute

- Early Music

- Piano Accompanying

- Degrees and Certificates

- Graduate Studies

- Undergraduate Studies

- Academic Affairs

- Eastman Community Music School

- Eastman Performing Arts Medicine

- George Walker Center for Equity and Inclusion in Music

- Institute for Music Leadership

- Sibley Music Library

- Summer@Eastman

- Residential Life

- Student Activities

- Concert Office

- Events Calendar

- Eastman Theatre Box Office

- Performance Halls

- Research and Recent Dissertations

About Eastman Research

The Eastman theory faculty pursues a broad range of research interests, including Schenkerian theory, studies in the theory and analysis of 20th-century music, history of music theory, musical perception and cognition, computing and music, and jazz and other popular music. An annual lecture series serves to expand research horizons still further. Guest lecturers have included David Huron, Philip Ewell, Joseph Straus, Mark Spicer, Ellie Hisama, Robert Hatten, Jocelyn Neal, Daniel Harrison, Yayoi Uno Everett, Michael Klein, Danny Jenkins, and John Roeder. Student-organized theory symposia provide opportunities for students to present papers and share research in progress. Graduate students present their work at regional and national conferences, as active contributors to the discipline. They also edit and publish, with the assistance of an editorial board of prominent music theorists, a juried music theory journal entitled Intégral .

Technological support for theoretical research is provided by the Music Research and Music Cognition Lab, which gives students the chance to learn and develop software for in-house and Internet use. The lab includes computers, seminar space, and a sound-proof booth for running music-cognitive experiments. Vital support for theory scholarship also is provided by the Sibley Music Library , which houses an extraordinary collection of historical treatises on music theory, manuscript letters, and first editions, and maintains active subscriptions to more than 650 periodicals.

Music Theory graduates join distinguished alumni from Eastman’s other PhD-granting disciplines—Musicology, Composition, and Music Education—many of whom are teaching and leading at musical institutions and schools around the world. This list offers a sample, rotating list of 50 PhD alumni from the past 30 years who are helping to shape the field of music through their work in a wide variety of colleges, universities, music schools, and other institutions.

Student Research Assistance Fund (SRAF)

Due to generous faculty and alumni donations to a new fund in support of student research, applications are invited from music theory students for grants to support specific research projects. Grants will typically be made in amounts of $300 or less.

Awards will be made by a committee consisting of the chair of music theory, plus one tenured and one untenured member of the theory department, each of whom serves for not less than one academic year.

Applications must be for an individual expenditure that is essential to the development or completion of a music theory research project. Examples include cost of specialized software for research, travel to present research at a conference, preparing music examples for a publication, or visiting an archive overseas, etc.

Students are expected to utilize funding sources already available to them (e.g., Professional Development Funds) prior to applying for SRAF funding.

E-mail Department Chair for more information on how to apply.

Recent Dissertations

Quick links.

- Theory Main

- Audition Repertoire

- Bachelor of Music in Theory

- Graduate Pedagogy

- Current Students

- Music Cognition

- Theory Colloquium

- Photo Highlights

- Departments Main

A Music Theory Curriculum for the 99%

- Trevor de Clercq Department of Recording Industry, Middle Tennessee State University

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2020 Trevor de Clercq

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

About the Journal

Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy presents short essays on the subject of student-centered learning, and serves as an open-access, web-based resource for those teaching college-level classes in music.

Make a Submission

Beginning with Volume 7 (2019), Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license unless otherwise indicated.

Volumes 1 (2013) – 6 (2018) were published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License unless otherwise indicated.

Volumes 1–6 are openly available here .

Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy is published by The Ohio State University Libraries.

If you encounter problems with the site or have comments to offer, including any access difficulty due to incompatibility with adaptive technology, please contact [email protected] .

ISSN: 2689‐2871

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Theories of Creativity in Music: Students' Theory Appraisal and Argumentation

Associated data.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset includes qualitative case descriptions, with information that could reveal the identity of the participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to [email protected] .

Most research on people's conceptions regarding creativity has concerned informal beliefs instead of more complex belief systems represented in scholarly theories of creativity. The relevance of general theories of creativity to the creative domain of music may also be unclear because of the mixed responses these theories have received from music researchers. The aim of the present study was to gain a better comparative understanding of theories of creativity as accounts of musical creativity by allowing students to assess them from a musical perspective. In the study, higher-education music students rated 10 well-known theories of creativity as accounts of four musical target activities—composition, improvisation, performance, and ideation—and argued for the “best theoretical perspectives” in written essays. The results showed that students' theory appraisals were significantly affected by the target activities, but also by the participants' prior musical experiences. Students' argumentative strategies also differed between theories, especially regarding justifications by personal experiences and values. Moreover, theories were most typically problematized when discussing improvisation. The students most often chose to defend the Four-Stage Model, Divergent Thinking, and Systems Theory, while theories emphasizing strategic choices or Darwinian selection mechanisms were rarely found appealing. Overall, students tended toward moderate theory eclecticism, and their theory appraisals were seen to be pragmatic and example-based, instead of aiming for such virtues as broad scope or consistency. The theories were often used as definitions for identifying some phenomena of interest rather than for making stronger explanatory claims about such phenomena. Students' theory appraisals point to some challenges for creativity research, especially regarding the problems of accounting for improvisation, and concerning the significance of theories that find no support in these musically well-informed adults' reasoning.

Introduction

Theories and informal conceptions regarding creativity.