Neuropsychiatric manifestations of HIV infection and AIDS

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 16049567

- PMCID: PMC1160559

Abstract in English, French

As the life expectancy of people living with HIV infection has increased (through recent advances in antiretroviral therapy), clinicians have been more likely to encounter neuropsychiatric manifestations of the disease. Some patients present with cognitive deficits due to an HIV-triggered neurotoxic cascade in the central nervous system. However, more patients present with a depressive spectrum disorder during the course of their illness, the underlying pathogenesis of which is not as well understood. This category of psychiatric disorders presents diagnostic challenges because of the many neurovegetative confounding factors that are present in association with HIV illness. As quality of life becomes a more central consideration in the management of this chronic illness, better awareness of these neuropsychiatric manifestations is paramount. This article reviews these clinical issues and the available psychopharmacologic treatment options.

Comme l'espérance de vie des personnes vivant avec le VIH a augmenté (grâce aux progrès récents de la thérapie aux antirétroviraux), les cliniciens sont maintenant plus susceptibles de faire face à des manifestations neuropsychiatriques de la maladie. Certains patients se présentent avec des déficits de la cognition attribuables à une cascade neurotoxique déclenchée par le VIH dans le système nerveux central. Plus de patients se présentent toutefois avec un trouble du spectre dépressif pendant leur maladie, dont on ne comprend pas aussi bien la pathogénèse sous-jacente. Cette catégorie de troubles psychiatriques pose des défis diagnostiques en raison des nombreux facteurs confusionnels neurovégétatifs associés à l'infection par le VIH. Comme la qualité de vie devient un facteur plus central dans la prise en charge de cette maladie chronique, il est primordial d'être plus conscient de ses manifestations neuropsychiatriques. Dans cet article, les auteurs passent en revue ces enjeux cliniques et les traitements psychopharmacologiques possibles.

Publication types

- Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

- Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome / psychology*

- Antidepressive Agents / therapeutic use

- Antipsychotic Agents / therapeutic use

- Brain / physiopathology*

- Central Nervous System Stimulants / therapeutic use

- Cognition Disorders / diagnosis

- Cognition Disorders / etiology

- Cognition Disorders / physiopathology

- HIV Infections / psychology*

- Mental Disorders* / drug therapy

- Mental Disorders* / etiology

- Mental Disorders* / physiopathology

- Neuropsychological Tests

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors / therapeutic use

- Antidepressive Agents

- Antipsychotic Agents

- Central Nervous System Stimulants

- Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors

Advertisement

HIV and AIDS in Older Adults: Neuropsychiatric Changes

- Geriatric Disorders (JA Cheong, Section Editors)

- Published: 09 July 2022

- Volume 24 , pages 463–468, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Paroma Mitra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1947-3564 1 , 2 ,

- Ankit Jain 3 &

- Katherine Kim 1 , 2

685 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

Patients diagnosed with HIV can now survive well into their old age. Aging with HIV is not only associated with comorbid medical illnesses but also with neuropsychiatric conditions that can range from cognitive changes to severe behavioral manifestations. This paper reviews mood, anxiety, and cognitive changes in older patients with HIV, as well as some of the treatment challenges in this population.

Recent Findings

Most recent findings show that untreated HIV illness over a long period of time may further worsen both preexisting neuropsychiatric illness and may cause new onset behavioral and cognitive symptoms. HIV induces immune phenotypic changes that have been compared to accelerated aging Low CD 4 counts and high viral counts are indicative of poor prognosis.

Evaluation for potential HIV infections may be overlooked in older adults and require screening. Older adults experience accelerated CD4 cell loss. Older adults endorsing new onset mood or cognitive changes must be screened for HIV infection. New onset neurobehavioral symptoms should be carefully screened for and treated simultaneously in patients with HIV infection.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Mechanisms of Cognitive Aging in the HIV-Positive Adult

Asante Kamkwalala & Paul Newhouse

HIV effects on age-associated neurocognitive dysfunction: premature cognitive aging or neurodegenerative disease?

Ronald A Cohen, Talia R Seider & Bradford Navia

Aging, comorbidities, and the importance of finding biomarkers for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders

Jacqueline Rosenthal & William Tyor

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States 2014–2018. HIV Surveill Rep Suppl Rep [Internet]. 2020;25(No. 1). [cited 2021 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html .

CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveill Rep [Internet]. 2020;31. [cited 2021 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html .

Stoskopf CH, Kim YK, Glover SH. Dual diagnosis: HIV and mental illness, a population-based study. Community Ment Health J. 2001;37(6):469–79.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Steves CJ, Spector TD, Jackson SHD. Ageing, genes, environment and epigenetics: what twin studies tell us now, and in the future. Age Ageing. 2012;41(5):581–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Vasto S, Scapagnini G, Bulati M, Candore G, Castiglia L, Colonna-Romano G, et al. Biomarkes of aging. Front Biosci Sch Ed. 2010;1(2):392–402.

Google Scholar

•• Watkins CC, Treisman GJ. Neuropsychiatric complications of aging with HIV. J NeuroVirol. 2012;18. This is an important paper- given that it summarizes the impact of aging on persons with HIV and also summarizes impact on both psychiatric illness that preexisted before HIV was detected and after.

Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FM, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):542–53.

Havlik RJ, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Comorbidities and depression in older adults with HIV. Sex Health. 2011;8(4):551.

Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, Watters M, Poff P, Selnes O, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii aging with HIV-1 cohort. Neurology. 2004;63(5):822–7.

Balderson BH, Grothaus L, Harrison RG, McCoy K, Mahoney C, Catz S. Chronic illness burden and quality of life in an aging HIV population. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):451–8.

Kilbourne AM, Justice AC, Rabeneck L, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Weissman S. General medical and psychiatric comorbidity among HIV-infected veterans in the post-HAART era. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):S22–8.

Oursler KK, Goulet JL, Crystal S, Justice AC, Crothers K, Butt AA, et al. Association of age and comorbidity with physical function in HIV-infected and uninfected patients: results from the veterans aging cohort study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(1):13–20.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rodriguez-Penney AT, Iudicello JE, Riggs PK, Doyle K, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, et al. Co-morbidities in persons infected with HIV: increased burden with older age and negative effects on health-related quality of life. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(1):5–16.

Angelino AF, Treisman GJ. Issues in co-morbid severe mental illnesses in HIV infected individuals. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20(1):95–101.

Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(3):453–72.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62(1):141–55.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Siegel K, Bradley CJ, Lekas H-M. Causal attributions for fatigue among late middle-aged and older adults with HIV infection. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(3):211–24.

Penzak SR, Reddy YS, Grimsley SR. Depression in patients with HIV infection. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57(4):376–86.

Rabkin JG. HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5(4):163–71.

Kalichman SC, Heckman T, Kochman A, Sikkema K, Bergholte J. Depression and thoughts of suicide among middle-aged and older persons living with HIV-AIDS. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):903–7.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS: J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(10):662–70.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gutkovich Z, Rosenthal RN, Galynker I, Muran C, Batchelder S, Itskhoki E. Depression and demoralization among Russian-Jewish immigrants in primary care. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(2):117–25.

Clarke DM, Kissane DW. Demoralization: its phenomenology and importance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(6):733–42.

•• Leserman J. HIV disease progression: depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):295–306. This is an important paper as it is the first to detail the effect of HIV on depression as well as the neurobiology of the same.

Ammassari A, Antinori A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli L, et al. Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(5):394–402.

Lyketsos CG, Treisman GJ. Mood disorders in HIV infection. Psychiatr Ann. 2001;31(1):45–9.

Article Google Scholar

Cooperman NA, Simoni JM. Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide among women living with HIV/AIDS. J Behav Med. 2005;28(2):149–56.

Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Adams JL, Thielman NM, Heine AD, Mugavero MJ, et al. The effect of antidepressant treatment on HIV and depression outcomes: results from a randomized trial. AIDS. 2015;29(15):1975–86.

Stockton MA, Udedi M, Kulisewa K, Hosseinipour MC, Gaynes BN, Mphonda SM, et al. The impact of an integrated depression and HIV treatment program on mental health and HIV care outcomes among people newly initiating antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Torpey K, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0231872.

Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Hardy DJ, Farinpour R, Newton T, Singer E. Methylphenidate Improves HIV-1–associated cognitive slowing. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):248–54.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Musisi S, Kiwuwa Mpungu S, Katabira E. Clinical presentation of bipolar mania in HIV-positive patients in Uganda. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(4):325–30.

Lyketsos CG, Schwartz J, Fishman M, Treisman G. AIDS mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(2):277–9.

Marinho M, Marques J, Bragança M. Aids mania – is it a potential indicator to initiate HAART? Eur Psychiatry. 2016;33(S1):S526–7.

• Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Johnson JR, Bulto M. Factors associated with risk for HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(2):221–7. This is a relevant paper as it address the impact of HIV infection on persons with severe persistent mental illness.

Blank MB, Himelhoch S, Walkup J, Eisenberg MM. Treatment considerations for HIV-infected individuals with severe mental illness. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):371–9.

Nurutdinova D, Chrusciel T, Zeringue A, Scherrer JF, Al-Aly Z, McDonald JR, et al. Mental health disorders and the risk of AIDS-defining illness and death in HIV-infected veterans. AIDS. 2012;26(2):229–34.

Dolder CR, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. HIV, psychosis and aging: past, present and future. AIDS Lond Engl. 2004;1(18 Suppl 1):S35-42.

Hriso E, Kuhn T, Masdeu JC, Grundman M. Extrapyramidal symptoms due to dopamine-blocking agents in patients with AIDS encephalopathy. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(11):1558–61.

Brandt C, Zvolensky MJ, Woods SP, Gonzalez A, Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM. Anxiety symptoms and disorders among adults living with HIV and AIDS: a critical review and integrative synthesis of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:164–84.

Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have TT, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):789–96.

Mitra P, Sharman T. HIV neurocognitive disorders. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021. [cited 2021 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555954/.

Navia BA, Price RW. The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome dementia complex as the presenting or sole manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Neurol. 1987;44(1):65–9.

Stern Y. Factors associated with incident human immunodeficiency virus–dementia. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(3):473.

•• Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–99. This is an important paper that addresses the current breakdown of neurocognitive disorders in HIV with staging.

Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16.

Navia BA, Jordan BD, Price RW. The AIDS dementia complex: I. Clinical features Ann Neurol. 1986;19(6):517–24.

Eggers C, Arendt G, Hahn K, Husstedt IW, Maschke M, Neuen-Jacob E, et al. HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorder: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Neurol. 2017;264(8):1715–27.

Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, Trevelyan CM, Hampton T, Rayment D, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2021 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011145.pub2/full .

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment: MOCA: A brief screening tool for MCI. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. HIV dementia scale: a rapid screening test: J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8(3):273–8.

Tozzi V, Balestra P, Bellagamba R, Corpolongo A, Salvatori MF, Visco-Comandini U, et al. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits despite long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-related neurocognitive impairment: prevalence and risk factors. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(2):174–82.

Letendre S. Validation of the CNS penetration-effectiveness rank for quantifying antiretroviral penetration into the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(1):65.

•• The Mind Exchange Working Group, Antinori A, Arendt G, Grant I, Letendre S, Chair, et al. Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: a consensus report of the mind exchange program. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(7):1004–17. This is an important paper as this group continually works on neurocognitive symptoms seen in HIV and updates their information.

Levy BR, Ding L, Lakra D, Kosteas J, Niccolai L. Older persons’ exclusion from sexually transmitted disease risk-reduction clinical trials. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(8):541–4.

Levy JA, Ory MG, Crystal S. HIV/AIDS interventions for midlife and older adults: current status and challenges. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Sup 2):S59–67.

Deeks SG, Phillips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338(jan26 2):a3172–a3172.

•• Work Group for HIV and Aging Consensus Project. Summary report from the human immunodeficiency virus and aging consensus project: treatment strategies for clinicians managing older individuals with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):974–9. This is another group that continues to address the overall effect of HIV on older individuals and gives treatment guidelines.

Kenedi CA, Goforth HW. A systematic review of the psychiatric side-effects of efavirenz. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1803–18.

Lochet P, Peyriere H, Lotthe A, Mauboussin J, Delmas B, Reynes J. Long-term assessment of neuropsychiatric adverse reactions associated with efavirenz. HIV Med. 2003;4(1):62–6.

Gutiérrez-Valencia A. Stepped-Dose versus full-dose efavirenz for HIV infection and neuropsychiatric adverse events: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(3):149.

Hoffmann C, Llibre JM. Neuropsychiatric adverse events with dolutegravir and other integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Aids Rev. 2019;21(1):1768.

Thompson A, Silverman B, Dzeng L, Treisman G. Psychotropic medications and HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(9):1305–10.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City, NY, USA

Paroma Mitra & Katherine Kim

Bellevue Hospital Center, New York City, NY, USA

Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paroma Mitra .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Geriatric Disorders

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mitra, P., Jain, A. & Kim, K. HIV and AIDS in Older Adults: Neuropsychiatric Changes. Curr Psychiatry Rep 24 , 463–468 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01354-z

Download citation

Accepted : 08 June 2022

Published : 09 July 2022

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01354-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mood disorder

- Neurocognitive disorder

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Diseases & Diagnoses

Issue Index

- Case Reports

February 2011

CASE REPORT: Neurocognitive Presentation of HIV: HIV-associated Progressive Encephalopathy

A case report and review of the literature explores hiv presenting as a syndrome complex with cognitive, motor, and behavioral features..

Eva Pilcher, MD and Michael J. Schneck, MD

Acute HIV infection often involves neurological symptoms in which patients present with an encephalopathic syndrome with no clear history that might otherwise raise a high index of suspicion for HIV. These patients, during the initial infectious phase, may not have yet underwent seroconversion and so routine HIV antibody testing may not be positive leading to a lost opportunity for treatment as anti-retroviral therapy is most effective in this acute phase of HIV infection. The phenomenon has been previously well-described but remains an under-recognized and under-appreciated presentation of HIV infection.

Case Report A 60-year-old man was admitted to the Loyola University Medical Center in November 2009 because of headache, neck pain, and fever. One week before admission, the patient went on a ship cruise to Puerto Rico. On the first day of the trip, he became ill with development of a headache accompanied by fever and chills. He was evaluated by the cruise physician and prescribed azithromycin. He was also advised to take ibuprofen. The patient continued this treatment for five days without improvement; his fever continued, the headache worsened, and he developed neck pain. He became progressively fatigued, weak, and also developed mild confusion. He returned from the cruise and was brought to our emergency department by concerned family members.

The patient lived at home with his family in another state and was an owner of several restaurants. He had traveled to Chicago two weeks prior to join his family on the aforementioned cruise, and was planning on returning home after the vacation. The patient's admission medical history included borderline hypertension, and admission medications were only acetaminophen. He provided no history of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use. He denied any nausea, vomiting, vision changes, focal neurological symptoms, or loss of consciousness.

On initial examination the patient appeared in mild distress due to the headache. The axillary temperature was 37.1°C. The pulse was regular at 89 beats per minute, the blood pressure was 137/81mm Hg, and the respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute.

The general examination showed no abnormalities. On neurological examination, however, he was inattentive and distractible; he had difficulty following two-step commands and recalled 2/3 words at five minutes. His speech was fluent.

The cranial-nerve examination was normal. He had some difficulty cooperating with the motor examination due to neck pain, but strength and coordination were otherwise normal. He was not able to stand with both eyes closed, but his gait otherwise appeared to be steady. The sensory and reflex examinations were also normal. The Brudzinski sign was negative, but the Kerning sign was positive.

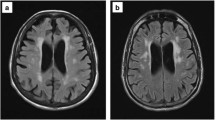

Laboratory investigations included a normal complete blood count and a complete metabolic panel. The C-reactive protein was elevated at 2.8, and the sedimentation rate was increased at 58. A chest radiograph was also normal except for an old clavicular fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, with special attention given to the temporal area, with and without gadolinium contrast, did not reveal any abnormalities. An electroencephalogram showed diffused slowing consistent with encephalopathy but no epileptiform activity. A lumbar puncture demonstrated mild lymphocytic pleocytosis: white blood cell count was 40 with 81 lymphocytes and elevated CSF protein at 63.

Because of the altered mental status and abnormal CSF findings, the possibility of viral encephalitis led to initiation of acyclovir 1000mg twice a day at admission. The HSV CSF titer drawn at admission was 3.01, and the patient was continued on acyclovir for a total of six days, until the HSHV PCR results came back negative. Multiple additional CSF studies were obtained, including West Nile Virus IgM, Varicella Zoster Virus, Cytomegalovirus, fungal cultures, CSF cultures, and Acid Fast Bacilli; these all returned negative.

Additional serum studies were sent for HIV 1 and 2 antibodies, influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus assay, blood cultures, Epstein Barr Virus and mononucleosis screen. All of these tests were also negative. A CT of the chest and thorax was obtained to investigate for any infectious or neoplastic process and was also normal.

Throughout the hospitalization, the patient continued to complain of neck pain that later developed into a back and shoulder discomfort, especially on the right side. It was thought that the discomfort might be attributable to muscle spasm, so a trial of cyclobenzaprine, and then low dose diazepam, was attempted without providing relief to the patient. Due to the continued significant pain in the neck, back, and shoulder, an MRI of the cervical spine and brachial plexus was obtained. The images from the initial MRI were suboptimal and the study was repeated again with sedation. The repeat study revealed no cervical spine or brachial plexus etiologies, but demonstrated a bursal surface tear of the right anterior supraspinatus tendon. Orthopedic consultants recommended conservative therapy and the patient was started on a flexor patch and a steroid taper for the rotator cuff injury.

Ultimately, the patient's family arrived from out of state and he was discharged with plan to travel back home and follow up with his primary care physician. It was not until two weeks after discharge that the HIV viral load returned at over 500,000 and the patient's primary physician was subsequently contacted, and retroviral therapy was initiated. Of note, neither the patient nor the family had ever provided a history of HIV risk factors.

Discussion Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has infected approximately 33 million individuals worldwide, and the virus is rapidly becoming a world pandemic. Initial presentation of an acute infection often involves neurological symptoms. These individuals present with an encephalopathic syndrome, but no prior suspicion for HIV diagnosis and insufficient HIV antibodies to produce a positive HIV enzyme immunoassay. They present at a crucial time: at initial phase of the infection, and prior to seroconversion, when antiretroviral therapy has been shown to be most effective in reducing mortality and morbidity. HIV infection of the CNS is especially problematic; it causes a barrier to management and eradication of the virus because of the incomplete impermeability to antiretroviral drugs, resulting in sub-therapeutic levels within the CNS. As a result, while the HIV infection goes undiagnosed, the CNS ends up being a reservoir for the virus, providing a safe environment where the virus can replicate and mutate. Early treatment with antiretroviral therapy targets the virus before it has the advantage of sequestration in the CNS. Considering the crucial importance of prompt and accurate diagnosis of an acute HIV infection, it is troublesome that guidelines for management of acute HIV aseptic meningitis are limited to case reports. The need for increased awareness of neurological presentation of acute HIV infection is evident.

On admission to the hospital, our patient was thought to have an acute change in mental status accompanied by headache, neck pain and fever along with CSF lymphocytosis and elevated CSF protein. In this patient, the absence of clinical and laboratory evidence of electrolyte or organ function abnormalities ruled out metabolic or toxicologic etiologies. Instead, given the abnormal cerecerebrospinal fluid findings, the focus was redirected at infectious causes of meningitis and encephalitis. While the patient was treated with an antiviral agent (acyclovir) because of appropriate concerns of HSV encephalitis, retroviral therapies were not initiated early in the course of therapy. All other tests for viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens were negative, and symptomatic treatment was ineffective except for a transient improvement in headache that may have been related to the administration of pain medications. It was not until after discharge that the HIV viral load was found to be significantly elevated; previously obtained HIV antibody testing was negative. As such, a missed opportunity for early intervention in HIV infection resulted.

In this context, the diagnostic evaluation was disappointingly inconclusive as to the etiology; it was not until after the patient had been discharged that an HIV viral load of over 500,000 was discovered. While the patient did not disclose any risk factors for HIV infection, his presentation was consistent with acute encephalitis likely due to a recent HIV infection. Unfortunately, it is often difficult to identify patients with primary HIV infection when they fail to disclose risk factors for acquiring the virus and there are no clinical findings indicative of immunosuppression. The presentation is depressingly common. Similarly, in other reports, patients with an underlying diagnosis of primary HIV infection were not initially identified, which resulted in a delay of diagnosis.

Successful identification of a primary HIV infection is fundamental; it offers the patient the opportunity to receive potent antiretroviral therapy prior to the time of virus seroconversion, when one can favorably affect the prognosis of the disease.

Neurological symptoms can occur before HIV diagnosis is suspected, before there are sufficient HIV antibodies to produce a positive HIV enzyme immunoassay. Neurological features of an acute HIV virus infection include aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis and encephalitis that can occur in up to 17 percent of patients. These individuals present with fever, headache, stiff neck, photophobia, CSF with mild lymphocytic pleocytosis and slightly elevated protein, but normal glucose. Approximately 40-90 percent of patients with an acute HIV infection present with physical symptoms similar to influenza or mononucleosis. Primary HIV infection is characterized by fever, lethargy, and headache and generalized flu-like symptoms. The HIV virus does not directly invade nerve cells, but rather causes inflammation. It is this persistent infection and inflammation that results in breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, neuronal and axonal injury, neurotoxicity, and clinical symptom such as confusion, forgetfulness, headache and even changes in behavior and cognition.

Unfortunately the management of acute HIV aseptic meningitis is limited to case reports. Our case is consistent with other reports in the literature. One case report described a patient that presented with mild confusion and was not able to follow commands. Another case described a patient that had been well until 13 days prior to presentation, at which time he began having bi-frontal headaches, low-grade fever and began experiencing changes in behavior. Interestingly, another very similar report described a 31 year-old male, which presented with one week of confusion and fever after having returned from a trip to the Caribbean; this patient's provisional diagnosis was viral encephalitis, based on lymphocytic fluid obtained via a lumbar puncture and he was treated with intravenous acyclovir.

It is evident that accurate diagnosis of HIV infection is crucial at time of acute onset. In acute presentation, when suspicion is high, the need for thorough history-taking cannot be forgotten. But patients can fail to disclose risk factors for HIV infection; hence, proper testing is crucial. It is important to remember that a viral load can detect the virus a few days after HIV infection, while a standard HIV antibody test can remain negative for months after the HIV infection.

While starting acyclovir in patients with a clinical picture of meningoencephalitis until an HSV PCR returns negative is an accepted clinical practice, a parallel approach is not considered for acute HIV infection. We suggest therefore, in cases of meningoencephalitis of unclear etiology, where the HIV antibodies are negative and the HIV viral load has been sent but remains pending, it may be reasonable to initiate a short course of retroviral drugs until return of the HIV viral load assay results. Thus, with awareness of the neurological presentations of an acute HIV infection, diligent history taking, proper laboratory testing, and rapid initiation of therapy, failure to identify primary infection can be minimized and crucial delays in antiretroviral therapy can be eliminated.

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests. An attempt was made to contact the patient, but this unsuccessful. However we have taken adequate steps to keep his identity safe and in no way have we revealed any personal information about the patient in the case report.

- Bruse James Brew. HIV Neurology. N Eng J Med 2001; 1713-1714.

- Hollander H, Schafer PW, Hedley-Whyte ET. Case 22-2005: An 81-Year-Old Man with Cough, Fever, and Altered Mental Status. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 287-95.

- José Biller. Practical Neurology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

- Newton PJ, Newsholme W, Brink NS, Manji H, William IG, Miller RF. Acute meningoencephalitis and meningitis due to primary HIV infection. BMJ 2002; 1225-1227.

- Ropper AH, Brown RH. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

- Scully RE, Mark EJ, McNeely WF, Ebeling SH, Phillips LD, Ellender SM. Case 10- 2000. Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital 200; 342: 957-965.

- Singer EJ, Valdes-Sueiras M, Commins D, Levine A. Neurological Presentation of AIDS. Neurological Clinics 2010; 253-275.

- Trancoso J, Rubio A, Fowler D. Essential Forensic Neuropathology. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wikins, 2009.

In The News

Editor's Message

Paul Winnington, Editorial Director

This Month's Issue

Jihad Yaqoob Ali AlKharbooshi, MD; Liju Yang, MD, PhD; and Adrian Budhram, MD

Fatma Ger Akarsu, MD; Andrea M. Kuczynski, MD, PhD; Gustavo Saponsik, MD, PhD; and Manav V. Vyas, MBBS, MSc, PhD, FRCPC

Raphael Schneider, MD, PhD, FRCPC, CIP

Sign up to receive new issue alerts and news updates from Practical Neurology®.

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV

Mar 17, 2013

400 likes | 817 Views

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV. University of Hawaii James Dilley, MD and Emily Leavitt, LCSW. Prevalence of MH Disorders among People with HIV/AIDS n = 1489. Vitiello et al. AJPsych 2003, 160:547-54 from “HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study—1996”. Depression in HIV.

Share Presentation

- toxic psychosis axis ii

- cognitive memory loss

- decreased libido

- vitiello et al

- metabolic disorders

Presentation Transcript

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV University of Hawaii James Dilley, MD and Emily Leavitt, LCSW

Prevalence of MH Disorders among People with HIV/AIDSn = 1489 Vitiello et al. AJPsych 2003, 160:547-54 from “HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study—1996”

Depression in HIV • Most common dx in outpt settings • Concern re: diagnosis in medically ill • Emphasize cognitive/affective vs. neurovegatative signs/sxs • Assoc with CD4, soc support and phys limitations and HIV sx • Excellent pharmacologic response • Give benefit of the doubt

Pharmacotherapy of Depression in HIV

Depression & Testosterone • 50% of men with Sx HIV/AIDS have deficiency and sx of hypogonadism: • Fatigue • Decreased libido • Decreased appetite • Decreased mood

Screening Tests • Total Serum Testosterone: <300-400ng/dl • Serum Free testosterone: <5-7 pcg/ml • Tx: depot IM injections q ii wks (100-200mg IM; max 400 mg/wk) • Patch (5-10mg; 1-2 times daily) • Gel (25-100 mg to skin daily) • Can see mood improvement

HIV produces at diff rates in CNS vs. plsma Diff phen/genotypes: esp later in disease All ARV’s not = in treating CNS cx May result in peripheral success (pVL) but central failure CNS: HIV’s Most Important Sanctuary Site

HIV Neuropathogenesis Early and continuous seeding Importance of Blood Brain Barrier

HAD: A Diagnosisof Exclusion • HIV antibody positive • No other treatable disorder known to be associated with mental status changes (e.g., no other CNS OI’s, trauma, metabolic disorders, etc.

Diagnosis Requires (continued): • “Clinical findings of disabling cognitive and /or motor dysfunction interfering with occupation or activities of daily living” • Neuropsychological testing often needed, especially in early cases-- • (1 SD below age/education adjusted norms on 2/8 tests) AND • Either impairment in lower ext or fine motor skills or selfreported depression interfering with function

Pseudo-Dementia • Depression in “dementia’s clothing” • Index of suspicion high if: • unremitting and detailed c/o memory pblms • “I don’t know” responses to cog questions: communicates distress/emphasizes disability • Behavior often incongruent w/level of complaint • In early stages of HIV disease • Frequently has past hx of psychiatric pblms

Cognitive Functions A. Memory Short-term vs. delayed B. Concentration, Calculation and Constructional Ability C. Personality Change: alteration or accentuation of pre-morbid traits D. Language E. Judgement “Reasonable plans”

Early Manifestations of HAD • Cognitive Memory Loss (names, historical details, etc.) Impaired Concentration (difficulty reading, loses track of conversation) Mental slowing (“not as quick,” less verbal) Confusion (time, especially)

Early Manifestations of HAD (continued) • Behavioral Apathy, withdrawal, “depression” Agitation, hallucination • Motor Unsteady gait Bilateral leg weakness Tremor Loss of fine motor coordination

Late Manifestations • Cognitive global dementia in all spheres confusion and distractability slow verbal responsiveness • Behavioral vacant stare disinhibition and restlessness organic psychosis

Late Manifestations (cont.) • Motor general slowing truncal ataxia weakness: legs > arms pyramidal tract signs: spasticity, hyperreflexia

Effect of HAART • Significant changes in the epidemiology of CNS disorders since HAART • In Sx illness • Studies are more consistent with subcortical dementia • In asx illness, NP findings are inconsistent • > Length of battery>NP deficits • Significance clinically is unclear

Pathological Findings in CNS of AIDS Patients at Autopsy N = 1597 1984-1987 (No therapy) 1988-1994 (monotherapy) 1995-1996 (dual comb. therapy) 1997-2000 (triple comb. therapy) Vago L., et al. AIDS 2002, 16:1925-28

Risk Factors for Cognitive Impairment in HIVCase Control: 90 HIV- ; 88 ASX; 94 SXCI = Scores of 2SD below the means of the control on 2 or more standard neuropsychological tests

HAART N 69 CD 4 254 UVL 42% NPI 22% Non-HAART 61 342 20% p<0.01 54% p<0.0001 HAART Use & NP FunctionN = 130; Avg Age = 41; 42% NW; 82% AIDS Ferrando et al., AIDS, 1998, 12F 65-70 NOTE: IMP = 25D in the impaired direction of age-matched population-based norms HAART= NRTI + Ritanavir, Indinavir or Nelfinavir

Median HIV RNA levels for brain (for all available brain regions) and peripheral tissues stratified by neurologic status: non-demented, mild, and moderate/severe McClernon D.R, et al. Neurology 2001, 57:1396-1401

P CSF < 200 >200 No No No Yes* No Yes No Yes* No No CSF NP Status < 200 >200 Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Correlation of Plasma VL to CSF VL Brew (Aus) Ellis (US) MacArthur (US) Dore (US) DiStephano (Italy) ___________________________ * Correlation exists in ASX state

Favorable CNS Characteristics of ARVs • % protein binding ( = better) • lipid solubility ( = better) • molecular weight ( = better) • inhibitory concentration ( = better)

Medical Rx of HAD 1. Aggressive ARV: neuroprotective 2. Use combinations of 3, 4 or more Should include: • AZT, D4T, 3TC, Abac-NRTI • Nevirapine, Efavirenz-NNRTI • Indinavir - PI (best BBB penetrance)

Factors Influencing Efficacy of ARV Rx: • Stage of HIV disease • Degree of CNS replication/resistance • Integrity of BBB • Specific treatment strategy/ARV choice

Some NeuroprotectiveDisappointments Nimodipene interaction with CAH Peptide T block gp-120 *Memantine NMDA antagonist/showing efficacy for ADV *Deprenyl Anti-oxidant/anti-poptotic Lexipafant PAF antagonist *some benefits

Case History - “JC” ID: 42 y/o GWM architect admitted for agitation, irritability, decreased sleep, and grandiose delusions. Brought in by lover of 7 yrs. HPI Two mos intermittent confusion/ hypomania (rapid speech, disorganized thinking over last 3 days; focus on spiritual issues. Felt friends were trying to harm him, stated he had been cured of AIDS; claimed he was a millionaire. PMH HIV infected x 10 years; current CD4 count = 70. No OI’s. No previous psych hx.

Case History - “JC” (cont.) MS: Alert, mildly agitated, unable to sit still. Speech: mildly pressured, loud, but interruptable. Thought process: overly inclusive, loose assns. Content: grandiose, “richest family in California,” had “cured himself of AIDS.” Some paranoia. Cognitive: 0 x 2. Memory: Imm = 4/4; 2/4 @ 5 mins. 3/4 with prompts. Attention: Serial 7’s = mult. Errors; WORLD backwards, “d-l-o-w.” Abstraction: Some concreteness. Construction: OK Insight: none Judgement: impaired

Case History - “JC” (cont.) Diff Dx: Axis 1: Delirium due to HIV disease (293.0). Dementia due to HIV disease (294.1) R/O BAD R/O Toxic Psychosis Axis II: Deferred Axis III: AIDS

Hospital Course LAB: MRI: Extensive cortical atrophy. LP: unremarkable Rx: Trilafon 2mg p.o. BID and 4 mg @ HS Valproic acid 250mg p.o. BID and 500 mg @ HS Ativan 0.5 mg p.o. BID and prn agitation

Psychotropic Medication Use NOTE: Use among Af-Am was significantly lower than White or Hispanic. Vitiello et al. AJPsych 2003, 160:547-54 from “HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study—1996”

Psychopharmacology in HIV Disease Consider geriatric dosing - “start low and go slow” Look for low-anticholinergic meds ConsiderPay special attention to Ritonavir (NORVIR - strong CYP3A4 inhibitor) Overall, anti-HIV meds are not problematic

Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders 1. “Reactive” Anxiety -Lorazepam 0.5 mg B/TID Max: 4 mg q 4 hrs 2. Panic Disorders with or without Agoraphobia Paroxetine (Paxil) 10-40 mg/D Lorazepam for breakthrough 3. GAD - Paroxetine;Buspirone (Buspar) 5-10 mg BID - 20 mg TID Note: Buspirone is the “does not” drug: cause tolerance, physical dependence or a withdrawal syndrome, have abuse potential (hypnotic, muscle relaxant activity), work right away

Ritonavir (Norvir)(Potent inhibitor of CP450, esp. 2D6 and 3A4) 1. AdjustAnti-depressants SSRI’s - initially by 1/2 TCA’s - initially by 1/2 to 1/3 Nefazodone and St. John’s Wort 2. Avoid Benzodiazepines Anti-psychotics Clonazepam (Klonopin) Clozapine Alprazolam (Xanax) Pimozide Diazepam (Valium) Flurazepam (Dalmane) Triazolam (Halcion) Zolpidem (Ambien) 2. Allow Temazepam (Restoril) Oxazepam (Serax) Lorazepam (Ativan) Bupropion (Wellbutrin)

Methadone • Ritonavir and Nevirapine (and likely Efavirenz) has been shown to lead to significant withdrawal symptoms in stable methadone users • Should follow serum meth levels before & after initiation; may need to increase by 25-30%

Other Pharm Issues • Sildenafil levels may be significantly raised by Ritonavir, Saquinavir and Indinavir--potentially serious CV effects (DNE 25mg) • Fatal case reports have been filed suggesting Ritonavir in combination with methamphetamine and Ecstasy (MDMA) was the cause of death • St. John’s Wort: may decrease PI’s

ARV Classes

- More by User

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Traumatic Brain Injury

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Traumatic Brain Injury. Jesse R. Fann, MD, MPH Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences University of Washington Seattle, Washington. Thursday, February 8, 2007 PRO FOOTBALL Expert Ties Ex-Player's Suicide To Brain Damage From Football

1.37k views • 56 slides

HIV Neuropsychiatric Issues

HIV Neuropsychiatric Issues. Warren Y.K. Ng, M.D. NYPH/ Harlem Hospital HIV Mental Health Training Project Columbia University. 28 th Year of AIDS World AIDS Day Dec 1, 2009. Twenty-Five year trends in HIV and AIDS cases 1984-2007. Good News and Bad News. Steven Deeks MD IAS-USA May 2009

870 views • 36 slides

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. Dr. Dallas Seitz MD FRCPC Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry Queen’s University. Objectives. 1 .) Understand the prevalence and importance of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of dementia

693 views • 43 slides

Clinical aspects of HIV

Clinical aspects of HIV. Dr. Amaj Saeed MB.CH.B MSc PhD Clinical virologist [email protected]. HIV – global impact. 4 th commonest cause of death 34.5 x 10 6 infections worldwide 24.5 x 10 6 in sub-Saharan Africa 33% 15 year olds infected in some African countries

404 views • 23 slides

NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS OF HIV CARE

NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS OF HIV CARE. Nurses at the Forefront of HIV Care 18-19 March 2010 Protea Court Yard Hotel . Entry points for raising nutritional issues in providing care and support. During post testing counseling. Part of voluntary counseling and testing programme. When

403 views • 22 slides

Biochemical bases of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders

Biochemical bases of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Jan ILLNER Jana Švarcová. Myasthenia gravis. Characterization: repetitive episodes of muscular weekness that is accented after physical load, ptosis, diplopia, troubles with speech

418 views • 21 slides

Clinical Aspects of HIV

Clinical Aspects of HIV. Rachel Gallen , Eduardo Cortez-Garcia, Kelli Chaviano , Amber Childers, James Barr April 5, 2012. Objectives. Discuss diagnosis of HIV Discuss screening infected individuals for other chronic infections

943 views • 50 slides

Neuropsychiatric Effects of Cocaine Use Disorders

By Shantanu Pisharoty and Omeshwari Devi Chudasama. Neuropsychiatric Effects of Cocaine Use Disorders. General effects of cocaine. Neuropsychiatric- suicidal behaviours , violent psychoses , strokes, seizures and encephalopathies . CVS

435 views • 14 slides

Aspects of HIV in Denmark

Aspects of HIV in Denmark. Jane Agergaard , MD, PhD Department of Infectious Diseases Aarhus University Hospital Skejby Denmark. Epidemiology. 250-300 new cases pr. year Constant during 10 years 70% men, <50% ethnic Danes MSM transmission in Denmark

169 views • 5 slides

Multi-Faceted Aspects of Acute HIV Infection Concluding remarks

Multi-Faceted Aspects of Acute HIV Infection Concluding remarks. Tony Kelleher Kirby Institute & St Vincent ’ s Centre for Applied Medical Research. Importance of primary HIV infection. Understanding transmission Determinants of outcome and set point Interventions that prevent progression

199 views • 7 slides

Clinical Aspects of HIV Disease

Clinical Aspects of HIV Disease. Kara Chew, M.D. Division of Infectious Diseases David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. Objectives. Part I: Overview of clinical aspects of HIV infection and associated clinical disease Acute infection HIV Basics

1.19k views • 77 slides

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of HIV

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of HIV. Thomas Newton, MD UCLA/Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center [email protected]. AIDS Education & Training Centers’ National Resources. Warmline: (800) 933 - 3413 PEPline: (888) 448 – 4911 (888) HIV - 4911

946 views • 68 slides

Paediatric aspects of adult HIV care

Paediatric aspects of adult HIV care.

327 views • 23 slides

Neurobehavioral and Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV/AIDS: An Update

Neurobehavioral and Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV/AIDS: An Update. Eileen Martin, PhD Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology University of Illinois at Chicago Supported by HHS DA R01 12828 and DA R01 13800. Objectives.

792 views • 55 slides

Unit 7: Operational Aspects Of The HIV Case Reporting System

Unit 7: Operational Aspects Of The HIV Case Reporting System. #6-0-1. Warm-Up Questions: Instructions. Take five minutes now to try the Unit 7 warm-up questions in your manual. Please do not compare answers with other participants. Your answers will not be collected or graded.

398 views • 31 slides

Neuropsychiatric Lupus

Neuropsychiatric Lupus. Seuli Bose Brill, MD Medicine AM Report 2/9/10. Historical perspective. Initially described by Mortiz Kaposi in 1870s (delirium) Further description by Osler in early 1903 Prior to this, lupus thought to be primarily cutaneous disease

321 views • 16 slides

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC LUPUS

By Prof. MEDHAT SHALABY Al- azhar university. NEUROPSYCHIATRIC LUPUS. NEUROPSYCHIATRIC LUPUS. INTRODUCTION EPIDEMIOLOGY PATHOGENESIS CLINICAL PERSENTATIONS MANAGEMENTS. CNS LUPUS.

545 views • 49 slides

Social and sensitive aspects of HIV prevention and male circumcision

Social and sensitive aspects of HIV prevention and male circumcision. Geoffrey Setswe DrPH, MPH Presentation at BMGF Male Circumcision Workshop held in Sandton 22 January 2010. Outline. HIV testing and male circumcision Women and male circumcision Neonates/children/minors and MC

137 views • 13 slides

Introduction to Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Introduction to Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Dr. eman abahussain Department of Psychiatry College of medicine King Saud University. Outline. Course and Prognosis How to differentiate between Delirium and Dementia Amnestic Disorder Diagnosis Etiology Management.

458 views • 20 slides

HIV / AIDS – dermatological aspects of this problem.

HIV / AIDS – dermatological aspects of this problem. Lector: Shkilna M. AIDS patients. Content. 1. Causative Agent 2. Modes of Transmission 3. Incubation period 4. Clinical features 5. Dermatological Manifestations of HIV-infection: Infectious coetaneous conditions.

470 views • 45 slides

Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Disorder

PCD Pharmau2019s treatment plans are individualized for each patient to complete their specific requirements, to reduce adverse effects while boosting efficacy.

64 views • 6 slides

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.151(3); 1989 Sep

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV Infection

Full text is available as a scanned copy of the original print version. Get a printable copy (PDF file) of the complete article (513K), or click on a page image below to browse page by page. Links to PubMed are also available for Selected References .

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Atkinson JH, Jr, Grant I, Kennedy CJ, Richman DD, Spector SA, McCutchan JA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Sep; 45 (9):859–864. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant I, Atkinson JH, Hesselink JR, Kennedy CJ, Richman DD, Spector SA, McCutchan JA. Evidence for early central nervous system involvement in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and other human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections. Studies with neuropsychologic testing and magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Dec; 107 (6):828–836. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Price RW, Brew B, Sidtis J, Rosenblum M, Scheck AC, Cleary P. The brain in AIDS: central nervous system HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia complex. Science. 1988 Feb 5; 239 (4840):586–592. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Neuropsychiatric care in HIV disease ranges from supportive psychotherapy for grief and loss issues to treatment of specific HIV-associated neuropsychiatric conditions (eg, HIV-associated dementia, minor cognitive motor disorder [MCMD], acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] mania), as well as management of unique clinical presentations of ...

Neuropsychiatric sequelae of HIV have been a primary focus of clinical research since the beginning of the epidemic. Depression has received a considerable amount of attention, owing in part to its high prevalence in HIV-positive individuals, ranging between 5.8 and 36.0% (Table DS1). ... Its presentation is variable, as it can often present ...

The neuropsychiatric effects of HIV can mimic idiopathic psychiatric disorders, delaying diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause. The differential diagnosis of behavioral disorders in HIV+ persons includes pre-existing psychiatric disease, infectious, and medication-related causes. ... The most common clinical presentation of HSVE ...

Abstract. As the life expectancy of people living with HIV infection has increased (through recent advances in antiretroviral therapy), clinicians have been more likely to encounter neuropsychiatric manifestations of the disease. Some patients present with cognitive deficits due to an HIV-triggered neurotoxic cascade in the central nervous system.

Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection have been noted to have various forms of neuropsychiatric illnesses. Neuropsychiatric illnesses include symptoms of both cognitive disorders as well as mood and anxiety symptoms.[1] In the past, before the advent of antiretroviral treatment, several neuropsychiatric disorders remained untreated, resulting in significant morbidity and ...

HIV infection or AIDS, and they all have side effects that can be severe. Because no vaccine for HIV is available, the only way to prevent infection is to avoid behaviours that put a person at risk of infection, such as sharing needles and unprotected sex. It is believed that neuropsychiatric disorders account for over 15% of the world s disease

Between 20% and 30% of patients with AIDS and 7% of asymptomatic HIV-1-infected patients have been reported to have a vitamin B12 deficiency. Further-more, vitamin B12 deficiency has previously been shown to be associated with depression and can occur in the absence of hematologic or neurologic signs (146).

Indeed, neuropsychiatric manifestations like HIV-associated dementia, motor/cognitive disorder, and secondary opportunistic infections may leave survivors feeling depressed, hopeless, and suicidal ...

Neuropsychiatric care in HIV disease ranges from supportive psychotherapy for grief and loss issues to treatment of specific HIV-associated neuropsychiatric conditions (eg, HIV-associated dementia, minor cognitive-motor disorder, acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS]-mania), as well as management of unique clinical presentations of other ...

Considerable progress has been made in the understanding of human immunodeficiency virus I (HIV I) infection during this decade since the initial description of the disorder (Gottlieb et al. 1981). While etiologic formulations for this disorder, now known as acquired...

HIV-associated deficits in episodic memory are readily observed on a variety of verbal (e.g., word lists and passages) and visual (e.g., simple and complex designs) tasks. Along with psychomotor slowing, deficits in episodic memory are arguably one of the most sensitive indicators of HAND (e.g., Carey et al. 2004 ).

Neuropsychiatric manifestations of HIV infection and AIDS. 2005 Jul;30 (4):237-46. As the life expectancy of people living with HIV infection has increased (through recent advances in antiretroviral therapy), clinicians have been more likely to encounter neuropsychiatric manifestations of the disease. Some patients present with cognitive ...

Older adults can also present with comorbid medical disorders which may confound the clinical presentation of HIV-related neuropsychiatric disorders. When patients with HIV have comorbid primary psychiatric disorders, it is important to note the drug interactions between ARV and psychotropic medications via the cytochrome system and adjust ...

UpToDate ... Why UpToDate?

The phenomenon has been previously well-described but remains an under-recognized and under-appreciated presentation of HIV infection. Case Report A 60-year-old man was admitted to the Loyola University Medical Center in November 2009 because of headache, neck pain, and fever. One week before admission, the patient went on a ship cruise to ...

Acute neuropsychiatric manifestations were reported in 6 children; namely drowsiness (5/12), seizures (4/12), sleep disturbances (2/12), personality changes (2/12), acute ataxia (1/12), and slurred speech (1/12). ... At presentation to the Neuro-HIV service, aged 8-9 years, she was stunted, underweight for age, and microcephalic. She had no ...

Presentation Transcript. Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV University of Hawaii James Dilley, MD and Emily Leavitt, LCSW. Prevalence of MH Disorders among People with HIV/AIDSn = 1489 Vitiello et al. AJPsych 2003, 160:547-54 from "HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study—1996". Depression in HIV • Most common dx in outpt settings ...

The 2023 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) featured new and impactful findings about neuropsychiatric complications in people with HIV and other infections. Reports included new evidence of (a) the importance of myeloid cells in the pathogenesis of HIV disease in the central nervous system, including as an HIV ...

DATA SYNTHESIS The clinical presentation and differential diagnosis of depressive symptoms in HIV illness and the role of HIV in the development of these conditions are reviewed. Management issues including suicide assessment and treatment options are then discussed, and potentially important pharmacokinetic interactions are reviewed.

UAB Department of Biostatistics 2024 Fineberg Award Presentations: DrPH Candidate: John Bassler Title: Redlining & HIV Suppression PhD Candidate: Li Zhang Title: Bayesian Models for Ordinal Response, powered by Concept3D Event Calendar Software ... HIV Suppression PhD Candidate: Li Zhang Title: Bayesian Models for Ordinal Response, powered by ...

Neuropsychiatric Aspects of HIV Infection - PMC. Journal List. West J Med. v.151 (3); 1989 Sep. PMC1026869. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health.