Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Connect with NIMH

- Digital Shareables

- Science Education

- Upcoming Observances and Related Events

Resources for Students and Educators

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) offers a variety of learning resources for students and teachers about mental health and the brain. Whether you want to understand mental health challenges, promote emotional well-being in the classroom, or simply learn how to take care of your own mental health, our resources cover a wide range of topics to foster a supportive and informed learning environment. Explore videos, coloring books, and hands-on quizzes and activities to empower yourself and others on the journey to mental well-being.

You can also find additional educational resources about mental health and other topics on NIH’s STEM Teaching Resources website .

Childhood Irritability : Learn about symptoms of irritability, why it's important to study irritability, NIMH-supported research in this area, and new treatments for severe irritability in youth.

Get to Know Your Brain: Your brain is an incredible and complex organ! It helps you think, learn, create, and feel emotions, and it controls every blink, breath, and heartbeat. Learn more about the parts of the brain and what each area helps control.

NIMH Deputy Director Dr. Shelli Avenevoli Discusses the Youth Mental Health Crisis: Learn about youth suicide, the effects of technology and the pandemic on the developing brain, and tips for supporting the mental health of youth.

Getting to Know Your Brain: Dealing with Stress: Test your knowledge about stress and the brain. Also learn how to create and use a “ stress catcher ” to practice strategies to deal with stress.

Coloring and activity books

Print or order these coloring and activity books to help teach kids about mental health, stress, and the brain. These are available in English and Spanish.

Get Excited About Mental Health Research!

This free coloring and activity book introduces kids to the exciting world of mental health research.

Stand Up to Stress!

This free coloring and activity book teaches children about stress and anxiety and offers tips for coping in a healthy way.

Get Excited About the Brain!

This free coloring and activity book for children ages 8-12 features exciting facts about the human brain and mental health.

Quizzes and activities

Use these fun, hands-on activities in the classroom or at home to teach kids about mental health.

Teen Depression Kahoot! Quiz

Engage students in fun and interactive competition as they learn about depression, stress and anxiety, self-care, and how to get help for themselves or others.

Stress Catcher

Life can get challenging sometimes, and it’s important for kids (and adults!) to develop strategies for coping with stress or anxiety. This printable stress catcher “fortune teller” offers some strategies children can practice and use to help manage stress and other difficult emotions.

Brochures and fact sheets

Below is a selection of NIMH brochures and fact sheets to help teach kids and parents about mental health and the brain. Additional publications are available for download or ordering in English and Spanish.

Children and Mental Health: Is This Just a Stage?

This fact sheet presents information on children’s mental health including assessing your child’s behavior, when to seek help, first steps for parents, treatment options, and factors to consider when choosing a mental health professional.

The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know

Learn about how the teen brain grows, matures, and adapts to the world.

Mental Health in Schools

Know the warning signs.

Learn the common signs of mental illness in adults and adolescents.

Mental health conditions

Learn more about common mental health conditions that affect millions.

Find Your Local NAMI

Call the NAMI Helpline at

800-950-6264

Or text "HelpLine" to 62640

Where We Stand

NAMI believes that public policies and practices should promote greater awareness and early identification of mental health conditions. NAMI supports public policies and laws that enable all schools, public and private, to increase access to appropriate mental health services.

Why We Care

One in six U.S. youth aged 6-17 experience a mental health disorder each year, and half of all mental health conditions begin by age 14. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), behavior problems, anxiety, and depression are the most commonly diagnosed mental disorders in children. Yet, about half of youth with mental health conditions received any kind of treatment in the past year.

Undiagnosed, untreated or inadequately treated mental illnesses can significantly interfere with a student’s ability to learn, grow and develop. Since children spend much of their productive time in educational settings, schools offer a unique opportunity for early identification, prevention, and interventions that serve students where they already are. Youth are almost as likely to receive mental health services in an education setting as they are to receive treatment from a specialty mental health provider — in 2019, 15% of adolescents aged 12-17 reported receiving mental health services at school, compared to 17% who saw a specialty provider.

School-based mental health services are delivered by trained mental health professionals who are employed by schools, such as school psychologists, school counselors, school social workers, and school nurses. By removing barriers such as transportation, scheduling conflicts and stigma, school-based mental health services can help students access needed services during the school-day. Children and youth with more serious mental health needs may require school-linked mental health services that connect youth and families to more intensive resources in the community.

Early identification and effective treatment for children and their families can make a difference in the lives of children with mental health conditions. We must take steps that enable all schools to increase access to appropriate mental health services. Policies should also consider reducing barriers to delivering mental health services in schools including difficulty with reimbursement, scaling effective treatments, and equitable access.

How We Talk About It

- Many mental health conditions first appear in youth and young adults, with 50% of all conditions beginning by age 14 and 75% by age 24.

- One in six youth have a mental health condition, like anxiety or depression, but only half receive any mental health services.

- Early treatment is effective and can help young people stay in school and on track to achieving their life goals. In fact, the earlier the treatment, the better the outcomes and lower the costs.

- Unfortunately, far too often, there are long delays before they children and youth get the help they need.

- Delays in treatment lead to worsened conditions that are harder — and costlier — to treat.

- For people between the ages of 15-40 years experiencing symptoms of psychosis, there is an average delay of 74 weeks (nearly 1.5 years) before getting treatment.

- Untreated or inadequately treated mental illness can lead to high rates of school dropout, unemployment, substance use, arrest, incarceration and early death.

- In fact, suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth ages 10-34.

- Schools can play an important role in helping children and youth get help early. School staff — and students — can learn to identify the warning signs of an emerging mental health condition and how to connect someone to care.

- Schools also play a vital role in providing or connecting children, youth, and families to services. School-based mental health services bring trained mental health professionals into schools and school-linked mental health services connect youth and families to more intensive resources in the community.

- School-based and school-linked mental health services reduce barriers to youth and families getting needed treatment and supports, especially for communities of color and other underserved communities.

- When we invest in children’s mental health to make sure they can get the right care at the right time, we improve the lives of children, youth and families — and our communities.

What We’ve Done

- NAMI letter of support for the Mental Health Services for Students Act (H.R. 1109), introduced by Reps. Napolitano and Katko

- NAMI letter of support for Mental Health Services for Students Act of 2019 (S. 1122) introduced by Senator Tina Smith

- NAMI Ending the Silence Presentation Program

Print this Page

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

12 templates

68 templates

el salvador

32 templates

41 templates

48 templates

33 templates

Reducing Mental Health Stigma in Schools

Reducing mental health stigma in schools presentation, free google slides theme and powerpoint template.

Mental health issues can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, or socio-economic status. Unfortunately, the stigma surrounding mental health problems can prevent many students from seeking the help they need. In order to reduce this stigma in schools, it is important to educate students, teachers, and staff about mental health and create a safe and supportive environment. Download our template and prepare a speech and its complementary slideshow. Be informative and thorough, and be sure to have nice slides so that everyone can follow everything that is being explained!

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 35 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

From evidence to impact: Joining our best school mental health practices with our best implementation strategies

There is substantial research evidence for the effectiveness of school mental health strategies across problem areas, developmental levels, and the prevention-intervention spectrum. At the same time, it is clear that the education and mental health fields continue to struggle to apply this evidence at any level of scale. This commentary reflects on ways in which education-specific applications of implementation science principles – and explicit consideration of determinants of implementation success – may guide more consistent use of evidence in school mental health. After reviewing implementation determinants and strategies across multiple levels of effect (i.e., the outer setting, inner setting, individual, and intervention levels), the commentary goes on to recommend specific areas of needed attention in school mental health implementation efforts and research. These include a need to adapt interventions to better fit the context of schools, streamlining school mental health programs and practices to make them more implementable, and recognizing the critical role of assessment and selection of evidence-based interventions by school leaders. The commentary concludes by reflecting on the substantial opportunity provided by the education sector to both apply and advance implementation science.

We live in an era in which mental health disorders in children are at historically high rates and rising (Houtrow et al., 2015; National Academies of Science, 2015), and yet only a small minority of youth who would benefit from mental health supports actually receive them (Costello, 2009; Costello et al., 2014 ). Given the opportunity presented by schools to identify and address youths’ social, emotional, and behavioral needs across tiers of prevention, early intervention, and targeted treatment, the field will benefit greatly from rigorous reviews of evidence about “what works.”

As such, this excellent special issue comes at a critical juncture. All the papers in this compendium make strong and compelling arguments about the importance of their respective problems, their relevance to public health and education, and the opportunities that exist for schools to address them. Moreover, each provides research-based, actionable information for the education and mental health sectors. As detailed in this special issue, evidence around effective strategies varies across problem areas, developmental levels, and the prevention-intervention spectrum. Nonetheless, it is clear that we have plenty of evidence for programs that are effective at addressing problems as diverse as aggression, anxiety, attention problems, and bullying.

At the same time, it is clear that the education and mental health fields continue to struggle to apply this evidence at any level of scale. Fabiano and Pyle (this issue), for example, observe that despite its high prevalence rate and a robust research base on school-based intervention strategies, there remains little in the way of a standardized outline of interventions or supports for students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A recent study illuminates the problem starkly: a review of individual education plans for 97 students with ADHD revealed that few included strategies with demonstrated effectiveness ( Spiel, Evans, & Langberg, 2014 ). As Fabiano and Pyle (this issue) conclude, “instead of the provision of effective interventions, children with ADHD are inconsistently supported in schools in a manner influenced by local custom” (p.XX). In sum, as noted by other authors in this special issue (e.g., Waschbush, Breaux, & Babinski), and in papers cited by these authors (e.g., Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 2002 ), failures of implementation are the norm in school-based mental health.

Viewing School Mental Health Interventions through an Implementation Lens

The problem of inadequate implementation support for research-based practices is, of course, not unique to schools. In healthcare, seminal work has documented that it takes 17 years for just 14% of original research to benefit practice ( Balas & Boren, 2000 ). Fortunately, in response to these issues, a transdisciplinary field focused on supporting effective implementation has emerged to address the persistent research-to-practice gap. Having identified and synthesized a range of factors across multiple levels that influence successful implementation ( Damschroder et al., 2009 ) and improve implementation outcomes ( Proctor et al., 2011 ), contemporary implementation science is now focused largely on developing and testing specific implementation strategies ( Cook et al., in press ; Lyon et al., under review ; Powell et al., 2015 ) that may hold promise for improving adherent uptake of research-based strategies, so we can consistently promote positive student outcomes. To do so, however, we must first take stock of the multiple levels of influence that may influence implementation success, and which can be targeted by implementation strategies.

Multilevel Influences on Implementation Success

As referenced in several the articles in this special issue, implementation is inherently a multilevel endeavor. Waschbush et al. (this issue) pay particular attention to the multilevel influences on successful implementation of school-based interventions, referencing four domains proposed by Gottfredson and Gottfredson (2002) in their influential paper on the quality of school-based prevention programs: Organizational capacity (e.g., staff morale, turnover); organizational support (e.g., availability of training and supervision, principal support to making these activities and other resources available); program features (such as curriculum elements and quality control mechanisms built into the intervention), and local integration (defined as the extent to which the program is built into everyday school routines).

In the years since Gottfredson and Gottfredson’s influential work, over 60 implementation frameworks have been described ( Tabak, et al., 2012 ), and mechanisms of action across elements of such frameworks are beginning to be identified ( Lewis et al., 2018 ; Williams, 2016 ). While many early heuristics referenced implementation determinants, implementation strategies, and implementation outcomes somewhat interchangeably, as shown in Figure 1 , implementation scientists now articulate each of these domains separately, as well as relationships across them, in an attempt to specify strategies that may address determinants and support successful implementation of research-based practices ( Lewis, 2017 ).

Causal model for applying implementation strategies to evidence-based programs (based on Lewis, 2017 ).

In another advance, frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroeder, 2009) have synthesized many overlapping perspectives about what determines implementation success. As a result, the field now has achieved reasonable consensus about the levels of influence in which implementation determinants operate – and thus, the levels where implementation strategies should be focused. These levels frequently include: (1) The outer setting, (2) the inner setting , (3) the individuals who will implement or enact the strategy, and (4) the intervention itself. Implementation processes often play out across each of these levels. Importantly, evidence suggests that implementation strategies that address more than one of these levels are frequently more effective than those targeting a single level ( Beidas & Kendall, 2010 ). Below, we review each of these levels, drawing examples from the special issue articles, and suggest candidate strategies that may improve implementation success.

Outer setting.

The outer setting reflects the larger political, social, and economic context in which implementation occurs. This includes norms, laws, and broader policies as well as inter-organizational linkages within a larger service system. In school mental health, the outer setting may be best defined at the level of the school district and beyond. Although the outer setting is commonly identified as critically important to implementation, it is notoriously difficult to change. Nevertheless, there are plenty of examples of outer setting strategies being employed to increase the availability of evidence-based practices (EBP) in mental health, often through policy and legislation (e.g., Powell et al., 2016 ; Trupin & Kerns, 2017 ).

Papers in the current special issue provide a number of relevant examples of the influence of the outer setting to school mental health. For example, in their recommendations for implementing anxiety interventions in schools, Jones et al. (this issue) detail the ideal timing of implementation and how it can best fit within the academic calendar, which is typically set at the district level. Singer and colleagues (this issue) discuss how outer setting determinants and strategies can manifest as training or professional development mandates, such as those for suicide-related gatekeeper training. As noted by Thomeer and colleagues (this issue) in their description of the work conducted by Locke et al. (2015) , funding availability – or, more commonly, lack of availability – is another critical state- and/or district-level determinant.

At the level of the outer context, many of the most relevant approaches for increasing the availability of EBP are actually dissemination strategies that involve the targeted distribution of information to specific audiences, such as legislators ( Purtle, Brownson, & Proctor, 2017 ; Purtle et al., 2018 ). Among educators seeking to develop a comprehensive, consistent, and sustainable continuum of supports for students’ social, emotional, and behavioral well-being, the policy and funding context – or outer setting – can be extraordinarily influential. For example, without accompanying funding, legislation focused on addressing one problem can impact implementation of other services – including implementation of school-based EBPs – in a way that is viewed as deleterious by local school officials. One study examined local education association officials’ perspectives on an array of such unfunded or underfunded mandates (New Jersey School Boards Association, 2016), including one aimed at reducing harassment, intimidation, and bullying (HIB). Seventy percent of districts reported needing to shift funds for other programs to comply with the requirements of the HIB legislation. As one superintendent put it, “we reallocated resources [to HIB] and lost time to support students with substance-abuse concerns” (p.7). The first recommendation from this report was to urge local boards of education “to adopt resolutions calling on state and federal officials to provide adequate funding of required programs” (p. 19).

Inner setting.

The inner setting is the immediate organizational context in which implementation occurs. Extensive research has supported the importance or inner setting organizational variables for successful implementation across service contexts ( Aarons et al., 2012 ; Beidas et al., 2013 , 2015 ; Bonham et al., 2014 ; Glisson, 2002). In schools, the inner setting is often defined at the building level, including principals, grade level leaders, and distributed leadership teams ( Lyon et al., 2018 ). Building-level leadership – and the continua of incentives and disincentives that leaders and leadership structures adopt and support – drives school climate and is critical to the adoption and sustainment of new practices.

Research has found that principal support is important to promoting implementation of SEL curricula (e.g., Brackett et al., 2012 ), school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS; e.g., McIntosh et al., 2016 ), and more intensive indicated interventions for mental health concerns (e.g., Forman & Barakat, 2011 ). Research on PBIS has also found that the fidelity with which PBIS is implemented, including composition and activities of school-level PBIS leadership teams, is associated with impacts on outcomes such as rates of student disciplinary actions (e.g., Flannery, Fenning, Kato, McGrath, & McIntosh, 2014 ). Given the high level of influence that “inner setting” variables such as building-level leadership plays in achieving both implementation outcomes and student outcomes, it is noteworthy that little attention in the current special issue is paid to research on the influence of such factors on the success of the various EBPs reviewed, or inner setting strategies for ensuring their successful implementation. Such a dearth of information on these critical implementation determinants may point to a need for further research and development. As research on determinants continues to support the importance of leadership to implementation in the education sector, strategies for promoting facilitative leadership practices are increasingly indicated. Some direction may be taken from research in other service sectors that has developed strategies for influencing inner setting constructs, such as implementation leadership and implementation climate ( Aarons, Ehrhart, Garahnak, & Hurlburt, 2015 ), that are related to the adoption of new interventions.

Individual.

Individual-level implementation factors include, but are not limited to, the characteristics and experiences of front-line service providers responsible for delivering the types of evidence-based programs and practices described in the current special issue. Relative to some other healthcare settings, the school context provides opportunities for the expansion of interventionists to include many different types of personnel with different training backgrounds, ranging from paraprofessionals, to teachers, to dedicated school-based clinicians ( Owens et al., 2014 ). In addition to roles, professional backgrounds, and education status, individual practitioner-level factors such as their attitudes, beliefs, and self-efficacy around applying research-based programs have been found to influence implementation success (e.g., Henggeler et al., 2008 ), giving rise to an array of measures of these individual-level constructs (see Lewis et al., 2015 ). Individual strategies for targeting key individual-level determinants – such as school-based professionals’ motivation to engage in training and implementation – are beginning to emerge. In one example, Cook, Lyon, Kubergovic, Browning Wright, & Zhang (2015) described a brief implementation strategy that leverages existing theory to target the attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceived social norms of front-line practitioners to improve implementation intentions and, ultimately, behaviors.

Perhaps most oft-cited among individual level implementation drivers, however, is workforce development. As pointed out by multiple authors in this issue (e.g., Fabiano & Pyle, this issue; Thomeer et al., this issue), training opportunities for educators are consistently suboptimal, resulting in persistent knowledge gaps among many front-line personnel. In addition to being the subjects of training, Nickerson and colleagues (this issue) also suggest that dedicated school mental health personnel may have a role in conducting schoolwide training efforts, at least in the domain of bullying prevention. This is a worthwhile suggestion to investigate provided that there are also accompanying opportunities for post-training supports. Indeed, it is perhaps the most robust and consistent finding in implementation research that one-time “train and hope” models of professional development are ineffective in producing practitioner behavior change ( Herschell et al., 2010 ; Joyce & Showers, 2002).

Intervention.

Contemporary implementation science tends to focus most on the inner setting and individual levels, despite consistent recognition that implementation outcomes are directly influenced by aspects of the interventions themselves ( Lyon & Bruns, in press ). Indeed, a recent systematic review of implementation science assessment instruments identified relatively few at the intervention level ( Lewis et al., 2015 ). Nevertheless, the characteristics of programs and interventions provide an array of implementation determinants, as well as untapped possibilities for corresponding intervention-level implementation strategies. For example, given that many school-based practices have been transported from other service settings ( Lyon et al., 2014 ), intervention-setting fit is particularly critical when implementing evidence-based practices in school mental health. The current special issue includes a wealth of reflections on the question of “goodness of fit” of the reviewed practices, including (1) questions about when interventions are “ready” to implement, based on evidence, and (2) aspects of intervention design and usability.

Intervention readiness for large scale implementation was referenced in multiple papers. Although the traditional view on intervention development and implementation is of a relatively linear, unidirectional path from developers and testers to eventual delivery in community contexts, this perspective has certainly contributed to the aforementioned “17-year gap” between initial development and broad-based application of research-based practices ( Balas & Boren, 2000 ). On the other hand, the development of evidence for interventions is often uneven, with robust evidence emerging for some applications of specific practices while other (often widespread) applications of the same practices remain unsupported by evidence.

As an example, Chafouleas et al. (this issue) indicate that, although there is strong evidence for some Tier 2 and 3 trauma interventions in schools, there is far less supporting evidence for Tier 1 trauma interventions. This is consistent with the results of a recent Campbell Collaboration systematic review that failed to find any studies of trauma-informed school approaches that were sufficiently rigorous to meet inclusion criteria ( Maynard et al., 2017 ). While we agree that there is a “critical need for rigorous research on implementation processes to identify cost-efficient and effective strategies for the adoption and implementation of trauma-informed approaches by schools” (p. XX), there is simultaneously a clear and present danger of leapfrogging to develop implementation strategies before the core practices are empirically substantiated. Similarly, Fabiano and Pyle (this issue) indicate that some practices such as functional behavioral assessments and daily report cards have good evidence at the elementary school level, but that evidence becomes much more limited when considered in secondary settings.

Other papers in this issue touch on the critically important topic of intervention design, including the complexity of evidence-based programs or practices and their design quality or packaging. For instance, one paper (Waschbusch et al., this issue) discussed reviews demonstrating that single-component interventions can be more effective than multicomponent interventions for aggression. Such evidence is encouraging given that intervention complexity is also a major barrier to evidence-based practice implementation ( Lyon & Koerner, 2016 ). Similarly, Fabiano and Pyle (this issue) point out that many interventions are multicomponent, and that “combining them all together may mask the effectiveness of some treatments and artificially inflate the effectiveness of others” (p. XX). Careful attention to the design quality and packaging of our best evidence-based programs and practices seems overdue if large-scale adoption and sustainment is the goal. User-focused intervention redesign is an underutilized implementation strategy for addressing intervention-level determinants improving design quality and contextual appropriateness ( Lyon & Bruns, in press ). Although relatively few implementation strategies explicitly target the intervention level, considerable direction may be taken from the field of user-centered design, which can supply new strategies geared toward ensuring compelling and usable interventions that demonstrate good fit to purpose ( Dopp, Parisi, Munson, & Lyon, in press ). The benefits of such redesign processes are discussed further below.

In sum, a wealth of evidence from research – as well as observations from authors of the papers in the current special issue – advise that evidence from controlled studies (where researchers are typically the intervention developers and conditions are optimally constructed to find positive effects) should only partially inform decision-making around intervention selection. Equally important, we must pay attention to the usability and feasibility of the interventions and strategies we choose to use in our schools.

In this commentary, we have aimed to complement an outstanding compilation of reviews of school-based interventions for common social, emotional, and behavioral problems with a discussion of factors at multiple levels that are likely to drive implementation success (or failure) of these programs. In reviewing the relative attention paid to the determinants of implementation success – in both the papers in the special issue and the commentary itself – several major themes are worth underscoring.

The first theme is that individuals championing the cause of supporting students’ social, emotional, and behavioral wellness (e.g., intervention developers, purveyors, and school leaders) may have particular control of factors at the intervention level, and as such, intervention-level determinants may warrant particular attention. For example, most psychosocial interventions in mental health are highly complex ( Comer & Barlow, 2014 ) and could benefit from streamlining ( Lyon & Koerner, 2016 ). This may be particularly critical in schools, given the demands on teachers, counselors, and other school helpers, the idiosyncrasies of the school calendar, and the primacy of the education mission over social-emotional wellness ( Bruns et al., in press ; Lyon et al., 2015; Owens et al., 2014 ). As such, we call upon those who develop, select, fund, and use school-based interventions to join into concerted action to ask how these programs – across all tiers of effort – can be simplified and streamlined.

At the intervention level, we also recommend against adhering too closely to mental models that emphasize “leaky pipelines” and/or “voltage drops” in implementation, whereby deviations from adherence to research-based protocols (often developed for settings other than schools) necessarily represent bad outcomes. Instead, we offer that deliberate adaptation in response to the prospective assessment of contextual needs is necessary for successful scale-up as well as beneficial evolution of our school-based strategies ( Chambers et al., 2013 ). Historically, implementation science has tended to see interventions as static protocols that, ideally, can be delivered with perfect reliability ( Lyon & Koerner, 2016 ). In reality, however, “there is no implementation without adaptation” ( Lyon & Bruns, in press ) and substantial improvements may be made to increase the usability and utility of interventions in the school context. Ideally, in addition to more successful local implementation of EBPs, such adaptations will be accompanied by evaluation of the incremental improvements in their usability and effectiveness ( Lyon, Koerner, & Chung, 2018 ), as well as improved iterations of school-based interventions that can be transported to other education settings. In such redesign scenarios, the effectiveness of interventions can be assured through measurement of an intervention’s proximal mechanisms ( Kazdin, 2007 ) (e.g., cognitive changes; skill uptake) that precede changes in symptoms or functioning.

Third, Chafouleas et al. (this issue) implore school mental health providers “to engage in direct and indirect assessment of key intervention usability factors, such as acceptability, feasibility, understanding, home-school collaboration, system climate, and system support.” We could not agree more. Although any such assessment of EBP feasibility, compatibility, and necessary support conditions will require additional efforts by already-overburdened school staff, such systematic assessment efforts hold promise of bearing fruit in the form of better implemented and more effective school mental health programming.

Fortunately, tools exist that can facilitate such assessment and selection. For example, the Hexagon Tool (Metz & Louison, 2018) provides an overarching heuristic framework for use by states, districts, and schools in evaluating the appropriateness of EBPs across six dimensions: Needs (how well the program or practice being implemented might meet identified needs); Fit (with local priorities, structures, support, and context); Resource availability (for training, staffing, data systems, and administration); Evidence (expected outcomes if the EBP is implemented as intended); Readiness for replication (including adequacy of operationalization and expert assistance available); and Capacity to implement on the part of the state, district, or school. In many ways, this tool provides a streamlined method of specifying categories of implementation determinants that may be relevant to schools.

To fully assess the organizational implementation context of schools, our research team has been working to adapt a suite of instruments measuring aspects of school leadership, climate, and employee citizenship behaviors that are most proximal to the implementation of evidence-based practices ( Locke et al., in press ; Lyon et al., 2018 ). Assessment of these constructs may aid in the determination of whether and when a school is ready to implement an EBP, as well as identification of key leverage points for shifting individuals and school systems to be more conducive to the introduction of new practices.

These variables represent key inner setting determinants of implementation outcomes, which – as discussed above – have increasingly been found to promote implementation. The tools provide one pathway through which to increase the attention paid to those variables in education sector research. Given emerging research that is evaluating how these determinants (e.g., implementation leadership, implementation climate) may also be malleable in response to targeted intervention at the organizational level (e.g., Aarons, Ehrhart, Moullin, Torres, & Green, 2017 ), such constructs also reflect potentially important implementation mechanisms ( Lewis et al,. 2018 ) for organizationally-focused implementation strategies in schools.

As demonstrated by the depth of content of the current special issue of School Mental Health, understanding and mobilizing the evidence base on school-based interventions for emotional and behavioral needs of students is a complex endeavor. To demand that we also apply an implementation lens to this effort may be critiqued as only serving to exponentially increase an already burdensome challenge. Indeed, a skeptic might complain that we are now asking not just that education leaders remodel a house, but to remodel a house that is changing its shape all the time and is also continually occupied by a very large family and all its pets. However, with an estimated two-thirds of EBP implementation efforts ending in failure (Damschroeder et al., 2009), it is incumbent that we seek guidance from sources such as implementation science, which provides a framework for accounting for the multiple and dynamic drivers of success, such as via the mechanisms proposed in Figure 1 .

Fortunately, the school setting provides a particularly hospitable environment for promoting systematic, data-driven approaches to implementing effective school mental health practices. Measurement is inherent to education, with variations of implementation determinants (e.g., school climate), implementation outcomes (e.g., teacher performance), and student outcomes (e.g., disciplinary actions, attendance, and achievement) just a few examples of data points that are regularly collected and used.

Moreover, frameworks such as multi-tiered systems of student supports (MTSS; Lane, Menzies, Ennis, & Bezdek, 2013 ) and positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS; Sugai & Horner, 2009 ) have gained widespread adoption, and provide a means to guide selection, organization, implementation, and evaluation of student support strategies and behavioral interventions across multiple tiers of effort. As detailed by authors such as Kincaid and Horner (2017) and Freeman, Miller, and Newcomer (2015), strategies promoted by the PBIS and MTSS frameworks align well with the conceptual framework provided by implementation science. PBIS strategies are also accompanied by well-operationalized procedures and tools that do not only support adherent implementation of PBIS, but that, in and of themselves, represent potentially fruitful enabling strategies that could support implementation of any EBP.

For example, in PBIS and MTSS, district-level leadership teams promote attention to fiscal, policy, and political factors at the outer setting . Meanwhile, district- and school-level teams undertake specific facilitative administration supports and provide leadership training to create hospitable conditions at the inner setting of the school. PBIS also promotes competency at the individual (staff) level via strategies such as staff selection protocols, layered training systems for all school roles, and data-driven coaching. Finally, at the intervention level, PBIS employs tools for strategic EBP selection and consistent data collection on the fidelity and impacts of both the overall PBIS process as well as individual EBPs (Freeman, Miller, & Newcomer, 2015; Sugai & Horner, 2009 ).

Thus, in the form of PBIS and MTSS, the education sector benefits from “operating systems” that are not only informed by implementation science, but that attempt to mobilize implementation science via an organized system of practical strategies. Since research has shown that PBIS can effectively promote a range of positive school climate and student behavioral outcomes (e.g., Bradshaw, Mitchell, & Leaf, 2010 ), that adherence to these strategies is associated with positive outcomes ( Kincaid & Horner, 2017 ), and that many of the core features of PBIS may also function as implementation strategies for carefully selected EBPs, one could argue that school mental health and positive behavioral support provides one of the most comprehensive examples currently available for the potential power of implementation science to promote evidence-based programs.

We look forward to seeing future articles and special issues of School Mental Health focused on efforts to explicate, implement, and evaluate implementation strategies for empirically supported school-based services. By joining our best programs to our best implementation strategies, we can meaningfully advance both the emerging field of implementation science and the social, emotional, and behavioral wellness of our students.

The authors received no funding to support this article.

Conflict of interest:

Aaron Lyon declares he has no conflicts of interest. Eric Bruns declares he has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by either of the authors.

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, & Hurlburt MS (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): a randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation . Implementation Science , 10 ( 1 ), 11. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Moullin JC, Torres EM, & Green AE (2017). Testing the leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI) intervention in substance abuse treatment: a cluster randomized trial study protocol . Implementation Science , 12 ( 1 ), 29. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aarons GA, & Sommerfeld DH (2012). Leadership, Innovation Climate, and Attitudes Toward Evidence-Based Practice During a Statewide Implementation . Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 51 ( 4 ), 423–431. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.018 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balas EA, & Boren SA (2000). Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement . Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient-Centered Systems . Retrieved from https://augusta.openrepository.com/augusta/handle/10675.2/617990 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beidas RS, Aarons G, Barg F, Evans A, Hadley T, Hoagwood K, … Mandell DS (2013). Policy to implementation: evidence-based practice in community mental health – study protocol . Implementation Science , 8 ( 1 ), 38 10.1186/1748-5908-8-38 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beidas RS, & Kendall PC (2010). Training Therapists in Evidence-Based Practice: A Critical Review of Studies From a Systems-Contextual Perspective . Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice , 17 ( 1 ), 1–30. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beidas RS, Marcus S, Aarons GA, Hoagwood KE, Schoenwald S, Evans AC, … Mandell DS (2015). Predictors of Community Therapists’ Use of Therapy Techniques in a Large Public Mental Health System . JAMA Pediatrics , 169 ( 4 ), 374–382. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3736 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bonham CA, Sommerfeld D, Willging C, & Aarons GA (2014). Organizational Factors Influencing Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices for Integrated Treatment in Behavioral Health Agencies . Psychiatry Journal . 10.1155/2014/802983 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brackett MA, Rivers SE, Reyes MR, & Salovey P (2012). Enhancing academic performance and social and emotional competence with the RULER feeling words curriculum . Learning and Individual Differences , 22 ( 2 ), 218–224. 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.10.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradshaw CP, Mitchell MM, & Leaf PJ (2010). Examining the Effects of Schoolwide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on Student Outcomes: Results From a Randomized Controlled Effectiveness Trial in Elementary Schools . Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions , 12 ( 3 ), 133–148. 10.1177/1098300709334798 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruns EB, Pullmann MD, Nicodimos S, Lyon AR, Ludwig K, Namkung N, & McCauley E (in press). Pilot test of an engagement, triage, and brief intervention strategy for school mental health . School Mental Health . [ Google Scholar ]

- Chambers DA, & Azrin ST (2013). Partnership: A Fundamental Component of Dissemination and Implementation Research . Psychiatric Services , 64 ( 6 ), 509–511. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300032 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Comer JS, & Barlow DH (2014). The occasional case against broad dissemination and implementation: Retaining a role for specialty care in the delivery of psychological treatments . American Psychologist , 69 ( 1 ), 1–18. 10.1037/a0033582 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cook CR, Lyon AR, Kubergovic D, Browning Wright D, & Zhang Y (2015). A Supportive Beliefs Intervention to Facilitate the Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices Within a Multi-Tiered System of Supports . School Mental Health , 7 ( 1 ), 49–60. 10.1007/s12310-014-9139-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cook CR, Lyon AR, Locke J, Waltz T, & Powell B (in press). Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice . Prevention Science . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Costello EJ, He J, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, & Merikangas KR (2014). Services for Adolescents With Psychiatric Disorders: 12-Month Data From the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent . Psychiatric Services , 65 ( 3 ), 359–366. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100518 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science . Implementation Science , 4 ( 1 ), 50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dopp AR, Parisi KE, Munson SA, & Lyon AR (in press). A glossary of user-centered design strategies for implementation experts . Translational Behavioral Medicine . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flannery KB, Fenning P, Kato MM, & McIntosh K (2014). Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports and fidelity of implementation on problem behavior in high schools . School Psychology Quarterly , 29 ( 2 ), 111–124. 10.1037/spq0000039 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Forman SG, & Barakat NM (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the schools: Bringing research to practice through effective implementation . Psychology in the Schools , 48 ( 3 ), 283–296. 10.1002/pits.20547 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottfredson DC, & Gottfredson GD (2002). Quality of school-based prevention programs: Results from a national survey . Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency , 39 ( 1 ), 3–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Henggeler SW, Chapman JE, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Randall J, Shackelford J, & Schoenwald SK (2008). Statewide adoption and initial implementation of contingency management for substance-abusing adolescents . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 76 ( 4 ), 556–567. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.556 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, & Davis AC (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations . Clinical Psychology Review , 30 ( 4 ), 448–466. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kazdin AE (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research . Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol , 3 , 1–27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kincaid D, & Horner R (2017). Changing systems to scale up an evidence-based educational intervention . Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention , 11 ( 3–4 ), 99–113. 10.1080/17489539.2017.1376383 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lane KL, Menzies HM, Ennis RP, & Bezdek J (2013). School-wide Systems to Promote Positive Behaviors and Facilitate Instruction . Journal of Curriculum and Instruction , 7 ( 1 ), 6–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis CC (2017, September). What are implementation mechanisms and why do they matter? Plenary presentation at the 2017 Conference of the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) . Seattle, WA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, & Martinez RG (2015). Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria . Implementation Science , 10 ( 1 ), 155 10.1186/s13012-015-0342-x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Nolen E, … Powell BJ (2018). An updated protocol for a systematic review of implementation-related measures . Systematic Reviews , 7 ( 1 ), 66 10.1186/s13643-018-0728-3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Locke J, Lee K, Cook CR, Frederick L, Vazquez-Colon C, Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA, Davis C, & Lyon AR (in press). Understanding the organizational implementation context of schools: A qualitative study of multiple stakeholders . School Mental Health . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Locke J, Olsen A, Wideman R, Downey MM, Kretzmann M, Kasari C, & Mandell DS (2015). A Tangled Web: The Challenges of Implementing an Evidence-Based Social Engagement Intervention for Children With Autism in Urban Public School Settings . Behavior Therapy , 46 ( 1 ), 54–67. 10.1016/j.beth.2014.05.001 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, & Bruns EJ (in press). User-centered redesign of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to enhance implementation—Hospitable soil or better seeds? JAMA Psychiatry . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, Cook CR, Brown EC, Locke J, Davis C, Ehrhart M, & Aarons GA (2018). Assessing organizational implementation context in the education sector: confirmatory factor analysis of measures of implementation leadership, climate, and citizenship . Implementation Science , 13 ( 1 ), 5 10.1186/s13012-017-0705-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, Cook CR, Locke J, Davis C, Powell BJ, & Waltz TJ (under review). Importance and feasibility of an adapted set of strategies for implementing evidence-based mental health practices in schools . [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, & Koerner K (2016). User-Centered Design for Psychosocial Intervention Development and Implementation. Clinical Psychology : Science and Practice , 23 ( 2 ), 180–200. 10.1111/cpsp.12154 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, Koerner K, & Chung J (2018, December). How Implementable is that Evidence-Based Practice? A Methodology for Assessing Complex Innovation Usability Paper presented a the 11th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation . Washington, DC. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, Lau AS, McCauley E, Vander Stoep A, & Chorpita BF (2014). A case for modular design: Implications for implementing evidence-based interventions with culturally diverse youth . Professional Psychology: Research and Practice , 45 ( 1 ), 57–66. 10.1037/a0035301 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, Ludwig K, Romano E, Koltracht J, Vander Stoep A, & McCauley E (2014). Using modular psychotherapy in school mental health: Provider perspectives on intervention-setting fit . Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology , 43 , 890–901. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon AR, Whitaker K, Locke J, Cook CR, King KM, Duong M, … Aarons GA (2018). The impact of inter-organizational alignment (IOA) on implementation outcomes: evaluating unique and shared organizational influences in education sector mental health . Implementation Science : IS , 13 10.1186/s13012-018-0721-1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maynard B, Farina A, & Dell N (2017). Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools . Downloaded October 6, 2018 from https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/library/effects-of-trauma-informed-approaches-in-schools.html . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- McIntosh K, Mercer SH, Nese RNT, Strickland-Cohen MK, & Hoselton R (2016). Predictors of Sustained Implementation of School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports . Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions , 18 ( 4 ), 209–218. 10.1177/1098300715599737 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Owens JS, Lyon AR, Brandt NE, Masia Warner C, Nadeem E, Spiel C, & Wagner M (2014). Implementation Science in School Mental Health: Key Constructs in a Developing Research Agenda . School Mental Health , 6 ( 2 ), 99–111. 10.1007/s12310-013-9115-3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Rubin RM, Stewart RE, Wolk CB, Matlin SL, … Mandell DS (2016). Applying the Policy Ecology Framework to Philadelphia’s Behavioral Health Transformation Efforts . Administration and Policy in Mental Health , 43 ( 6 ), 909–926. 10.1007/s10488-016-0733-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, … Kirchner JE (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project . Implementation Science , 10 ( 1 ), 21 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, … Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda . Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 38 ( 2 ), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pulcini CD, Perrin JM, Houtrow AJ, Sargent J, Shui A, & Kuhlthau K (2015). Examining Trends and Coexisting Conditions Among Children Qualifying for SSI Under ADHD, ASD, and ID . Academic Pediatrics , 15 ( 4 ), 439–443. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Purtle J, Brownson RC, & Proctor EK (2017). Infusing science into politics and policy: The importance of legislators as an audience in mental health policy dissemination research . Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 44 ( 2 ), 160–163. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Purtle J, Lê-Scherban F, Wang X, Shattuck PT, Proctor EK, & Brownson RC (2018). Audience segmentation to disseminate behavioral health evidence to legislators: an empirical clustering analysis . Implementation Science , 13 ( 1 ), 121. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spiel CF, Evans SW, & Langberg JM (2014). Evaluating the content of Individualized Education Programs and 504 Plans of young adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder . School Psychology Quarterly , 29 ( 4 ), 452–468. 10.1037/spq0000101 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sugai G, & Horner RH (2009). Responsiveness-to-Intervention and School-Wide Positive Behavior Supports: Integration of Multi-Tiered System Approaches . Exceptionality , 17 ( 4 ), 223–237. 10.1080/09362830903235375 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, & Brownson RC (2012). Bridging Research and Practice: Models for Dissemination and Implementation Research . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 43 ( 3 ), 337–350. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Trupin E, & Kerns S (2017). Introduction to the Special Issue: Legislation Related to Children’s Evidence-Based Practice . Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 44 ( 1 ), 1–5. 10.1007/s10488-015-0666-5 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, Rittmueller SE, Ludman EJ, Lapham GT, … Bradley KA (2016). Local Implementation of Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention at Five Veterans Health Administration Primary Care Clinics: Perspectives of Clinical and Administrative Staff . Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment , 60 , 27–35. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.07.011. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

More mental health support in schools makes sense – but some children may fall through gaps

Senior Fellow, Health Services Management Centre, School of Social Policy, University of Birmingham

Disclosure statement

Jo Ellins receives funding from the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

University of Birmingham provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Schools and colleges have a crucial role to play in supporting children’s mental health. They are places where young people’s mental health difficulties are identified and help is provided, and they can promote all pupils’ emotional wellbeing.

Most children spend more time in school than anywhere else other than home, and parents who are concerned about their child’s mental health turn to teachers and school staff for advice more than any other professionals. Investing more in schools-based mental health services makes good sense.

This is something the government has been doing in England through the creation of mental health support teams. These are teams of mental health practitioners who work with clusters of schools and colleges. Most are based within the NHS, although some are provided by voluntary sector organisations or local councils.

The first 58 mental health support teams went live in 2020, working in and with more than 1,000 schools and colleges. By 2025, more than 600 teams will have been created, serving around half the schools in England.

I led an early national evaluation of the first 58 teams . This study looked at how they were set up, what support they were providing and how they were progressing. Together with colleagues, I found that increasing mental health support in schools was well received, but that some young people still faced difficulties getting appropriate help.

Mental health support teams are intended to provide support to young people with “mild to moderate” mental health difficulties, such as anxiety and low mood. Their role also includes working with school staff to develop a positive culture focused on wellbeing, and giving schools and parents advice to help them access other types of support. This includes specialist mental health services for young people with more serious or complex problems.

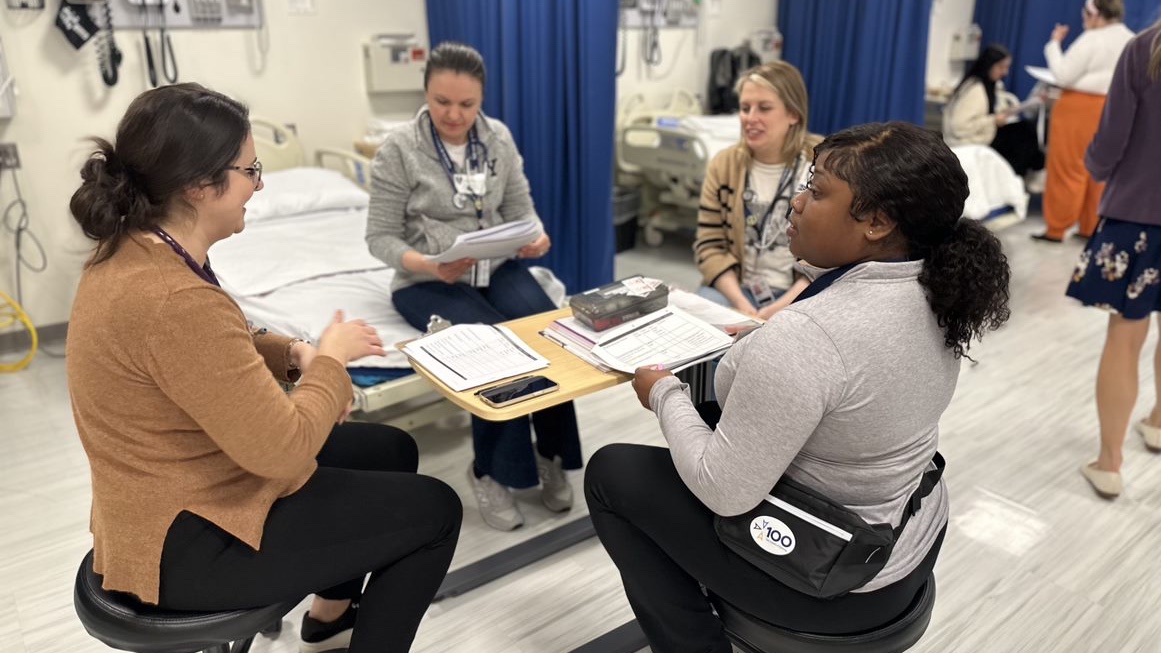

Much of the day-to-day work with young people and schools is delivered by education mental health practitioners . This is a new role in the mental health workforce, created specifically for mental health support teams.

Education mental health practitioners receive one year’s training with a focus on developing the skills to deliver cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to young people, either one-to-one or in small groups.

We heard from staff in the teams, schools and colleges, and those working in other local services supporting children’s mental health. We also spoke to young people at schools with mental health support teams.

Our study confirmed the importance of investing in schools-based mental health. School staff told us how valuable it was having ready access to advice when they were concerned about a pupil’s emotional wellbeing, and that they felt more knowledgeable and confident talking to young people about their mental health.

Having access to a team made it easier for some young people to get support at the right time. Timely access is crucial for many reasons, not least because more than half of young people experience a deterioration in their mental health while they are waiting for support.

Through the gaps

However, we also found that not all young people were benefiting from this investment. We heard that some young people were at risk of falling between gaps in provision. They had mental health problems that were neither “mild to moderate”, nor were they judged serious or urgent enough to meet the threshold for specialist NHS help.

There is evidence that thresholds for specialist NHS help are rising in response to growing demand, and so increasing numbers of young people may be falling into this gap between services.

Our early study was not designed to assess the effectiveness of the support that the teams were providing, but people we spoke to were keen to share their views about this. There were concerns from schools and colleges that the teams usually offered only one type of support, and that this was not suitable or beneficial for all young people.

The teams’ early experiences suggested that the CBT approaches that education mental health practitioners were trained to deliver didn’t work well for several groups. These included young people who had special education needs, or were neurodiverse, or whose mental health problems were related to traumatic circumstances or life events, such as poverty or domestic violence.

Wider research shows that CBT can be effective for these groups, but only when it is carefully tailored to their particular needs and circumstances, or is delivered in trauma-informed ways .

These findings offer valuable information about how well mental health support teams are working, but our study only looked at the first wave of teams. We don’t know if these experiences are the same for the teams that were set up later.

I am now co-leading a second, much larger, study of almost 400 mental health support teams, assessing their impact and cost-effectiveness. One of the main aims of our current study is to assess the impact of this support on young people’s mental health outcomes. As the study progresses, we will know more about how well this support works and who it works for.

- Young people

- Youth mental health

- Child wellbeing

- Keep me on trend

Psychiatrist - Multiple Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Mental Health in the Schools

Published by Alan Fleming Modified over 8 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Mental Health in the Schools"— Presentation transcript:

Improving Teen Mental Health

Understanding Depression

Sources: NIMH Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General Copyright © Notice: The materials are copyrighted © and trademarked ™ as the property of The.

All That Wiggles Is Not ADHD History, Assessment, and Diagnosis of ADHD Jodi A. Polaha, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Pediatrics Munroe-Meyer Institute, UNMC.

Attention-Deficit /Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention-Deficit/ Hyper Activity Disorder ( ADHD) By: Bianca Jimenez Period:5.

ADHD & ADD Understanding the Criteria for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Adapted from American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and.

West Mifflin Area High School Stand Together Committee presents… Stand Up to Stigma Week.

ADHD By Elizabeth Mihalick. What is ADHD? Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common childhood disorders and can continue.

Marlene B. Huff PhD, LCSW University of Kentucky Department of Pediatrics Division of Adolescent Medicine.

Constance J. Fournier. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and types of ADHD Basic interventions with ADHD ADHD and the typical comorbidity.

What is a mental health disorder? A mental disorder is a diagnosable illness that affects a person’s thoughts, emotions and behaviors. Someone with a.

Mental Health Health Day A / B. Definition Definition A state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the.

ADULT&child. National Research and Trends There are an estimated 4.5 to 6.3 million children and youth with mental health challenges in the United States.

Promoting Social Emotional Competence Individualized Intensive Interventions: Form & Function of Challenging Behavior.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Symptoms of ADHD The symptoms of ADHD include inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity. These are traits.

MARY MCCLURE, SOCIAL WORK FIELD PLACEMENT STUDENT Anxiety & Depression in School Age Children.

By: Rachel Tschudy. Background Types of ADHD Causes Signs and Symptoms Suspecting ADHD Diagnosis Tests Positive Effects Treatment Rights of Students in.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder Andrea, Janet, Liz and Sonia.

About us/ Why we are here The Right Solution Counseling Located in Eureka Over 15 years of experience in field of mental health Work with children and.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Mental Health in Schools

Sep 25, 2014

530 likes | 911 Views

Dr. Alan Brown, Chief Department of Psychiatry (HHS and JBMH) Medical Director Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Services (HHS). Mental Health in Schools. Overview . 1) Mental Health – Definition 2) Mental Illness – Inseparable from physical illness 3) Prevalence Rates

Share Presentation

- mental health

- mental illness

- anxiety disorders

- mental health disorders

- promoting students mental health

Presentation Transcript

Dr. Alan Brown, Chief Department of Psychiatry (HHS and JBMH) Medical Director Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Services (HHS) Mental Health in Schools

Overview 1) Mental Health – Definition 2) Mental Illness – Inseparable from physical illness 3) Prevalence Rates 4) Most Common – Anxiety, Depression, ADHD 5) Resilience 6) Treatment Resources

Mental Health Exists on a Continuum

Mental Disorder/Illness Mental Health Problem Mental Distress No Distress, Problem or Disorder The Inter-Relationship of Mental Health States

1 in 5 students will experience a mental health problem…. ONE in FIVE Every School…..Every Classroom

Mental Health is…. The ability to think, feel and act in ways that help us cope with life’s ups and downs, make good decisions and have meaningful relationships Balancing all parts of life is important to maintaining positive mental health and well-being

What are Mental Health Problems? Emotional, behavioural and brain-related disturbances that interfere with development, personal relationships, and functioning Disturbances that are severe and persistent enough to cause significant symptoms, distress, and impairment in one or more areas of daily life are termed mental health disorders/mental illness

Mental Health Problems include a Range of Difficulties Mental Health problems are characterized by many different signs and symptoms and present in various forms Some mental health problems manifest outwardly (externalizing) Students appear aggressive, impulsive, non-compliant Some mental health problems manifest inwardly (internalizing) Students appear withdrawn, lonely, anxious, depressed

Mental Illness is…. A medical condition that impacts functioning over a period of time Not result of a personal failure or weakness, but is caused by a social, psychological, genetic, physical, chemical or biological disturbance (often in combination)

What’s the Difference? Physiological differences in people who struggle with a mental health disorder Brain differences Driven by genetic, epigenetic effect (hereditability components to these disorders) Underlying genetic structure can be changed by environmental impacts suppressing or expressing genes Similar to other disorders i.e. diabetes

Mental Health Disorders are Physical Disorders Research (genetic, imaging, immunological) all show that mental health disorders are inflammatory disorders (redness, swelling, increased fluid secretion and diminished function in the brain) Not a choice or character flaw

The Good News Proven strategies and supports Psychosocial (talk therapy) and pharmacological (medications) treatments are most common, and are often used together While many mental disorders are chronic, we can help with coping Early identification and intervention improves prognosis

But Most Do Not Receive the Help They Need Up to 80% of children and youth who experience a mental health problem will not receive treatment Major barriers include: Lack of, difficulty accessing, or long waitlists for local services Stigma Misidentification or lack of identification of symptoms

Facts and Figures Causes – multiply determined (biological, life experiences, individual factors, early trauma) Onset – In 70% of cases, the onset of problems begins before age 18; with 50% of cases starting before age 14 Co morbidity – If have one disorder, other problems are also likely (75% have more than one mental health problem) Impact – disturbances to academic and social well-being, isolation, despair, anger; heightened risk of suicide Stage 1 versus stage 4 treatment: minimizing secondary impacts (reduce academic impact, social impact, identify formation in adolescence, sense of self)

Safe and Inclusive SchoolsHDSB Mental Health and Addiction Strategy Launched September 2013 Developed based on Resource Mapping and Needs Assessment Data Mental Health is the presence of physical, emotional, intellectual and social well-being. Our Mission: The Halton District School Board is committed to the mental health and well-being of every student. The Halton District School Board will inspire and support learning; create safe, health inclusive and engaging environments, provide opportunities for challenge and choice; and prepare students for success.

When Should I Be Concerned? Notice changes in behaviour See behaviour that are not age-appropriate Behaviours continue over a period of time Then: seek assistance from school supports (Teacher, Administration, SERT, PSSP)

Signs… Emotional/Behavioural Signs Academic Signs Communication/Social Skills Signs

Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Young People: Who is in your Classroom? Population Prevalence • Depression (4-6%) • Psychosis (0.5 – 1.0%) • Anxiety Disorders (6-10%) • ADHD (2-4%) • Anorexia Nervosa (0.1 -0.2 %) • Total (15-20%) • SUICIDE: 4-5/100,000 • ASD (1-4%) • Substance Abuse (10%) Translation to the “average” Classroom • Depression (1-2) • Psychosis (rare) • Anxiety Disorders (1-3) • ADHD (1) • Anorexia Nervosa (rare) • Total (3-5) • SUICIDE: 4-5/100,000 • ASD (1) • Substance Abuse (2-3)

Why Talk About It? Between 15%-25% of children/youth report at least one mental health problem or illness Suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death among Canadian adolescents Untreated youth mental health problems become adult mental health problems, 70% of adults with mental health issues reported problems started in childhood School difficulties may be a sign of emerging or unrecognized mental illness; these can impact a youth’s ability to be successful at school

What is an Anxiety Disorder? Feelings of excessive stress, fear, worry or nervousness over a prolonged period of time during situations where this response is not justified Interferes with daily activities and relationships Signs may include: school or task avoidance, worrying, frequent crying, isolation, easily frustrated, shyness, aggression, perfectionist behaviours

Types of Anxiety Disorders Generalized (over worry) Social (fear of negative judgement of others) Performance (pressure of situations) Anticipatory (too nervous before changes or transitions) Panic Attacks (provoked and unprovoked) Obsessive Compulsive Disorders

Normal Anxiety versus Anxiety Disorder ANXIETY BEHAVIOUR THOUGHTS PHYSICAL FEELINGS Anxiety is a normal emotion, it exists to help us survive, keep safe and perform better… It is time limited!

What is Depression? Normal to have feelings of sadness and disappointment Not simply having “the blues” A mood disorder causing a disruption in the way a person feels and experiences emotion and impacts daily functioning Clinical depression: low mood persists for at least 2 weeks and is accompanied by changes in physical, emotional and cognitive state

DEPRESSION IS A FLAW IN CHEMISTRY NOT CHARACTER

What Anxiety/Depression can look like at School Academic: poor concentration, forgetful, declining motivation, incomplete/late work, declining grades Emotional/Behavioural withdrawn, negative self talk, harmful coping styles, struggling with peers, teacher and family relationships, avoiding tests, school refusal, Day/Night reversal, nothing makes them happy

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Attentional: Difficulty focusing Sitting quietly, off task Hyperactive/Impulsive: Poor social behaviour and can impact peer relationships Impulsivity Taking turns may be challenging Completing tasks or attending to details

Dual Diagnosis Two or more diagnosed disorders ASD, MID, DD: May or may not have mental illness symptoms presenting as part of ASD diagnosis e.g. ASD and OCD, anxiety (social, performance, anticipatory, panic attacks) Students with ASD may have significant psychiatric challenges that can be treated to help these students function

Other Bi-Polar Mood Disorders 4% Schizophrenia 1% Schizo-Affective Disorder 0.5% Psychosis 1-2% Reactive-Attachment Disorder vs. Attachment Disorders Post Traumatic Stress Disorders

Factors Associated with Effective Mental Health Promotion (Resilience) Programs that focus on applying physical social emotional learning skills in daily life Using interactive classroom instruction with frequent opportunities to practice Culture of respectful supportive relationship among students, school staff, and families Multi-year, multi-component approaches Whole school, community-involved approaches Support physical fitness development Greenberg et al., 2003 Stewart-Brown, 2006

What Do All Child/Youth Students Need? A warm welcome A smile A connection to a caring adult, every day A chance to learn A safe place to risk Someone who notices when something is wrong Someone who reaches out when they notice Someone who listens, and tries to find help for them Someone who believes in them, and instils hope

Caring Adults… Know their children students Notice changes Listen attentively Don’t promise to keep secrets Reframe negative thinking and find ways to build hope Use humour Nurture strength as a lever to hope Know where to get help when problems are too big to manage alone

Caring Classrooms Build Skills We can be proactive by teaching students social emotional learning skills so they are prepared for life’s challenges Research suggests that social emotional skill building helps students both emotionally AND academically Five core skill areas have been identified: Self Awareness Social Awareness Self-Regulation Relationships Decision-making

Relationships are Key Empathy Positive Regard Respect Genuineness Specificity of Response Concrete

New release from the Ministry of Education – An Educator’s Guide to Promoting Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being

Resources School teachers, counsellors, social workers, CYC’s, administration Primary physicians and paediatricians ROCK – behavioural difficulties Woodview – behavioural difficulties Nelson Youth Centre – social skills Hospital Outpatient Services, Clinical Day treatment Services (HHS, JBMH) Emergency Department CAPIS (Child/Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Services) ADAPT (Alcohol and Drug Assessment Prevention and Treatment Services) Halton Support Services – Autism and Developmental Delay CAS (Children’s Aid Society) Websites e.g. CAMH, moodgym.com Private therapists/psychologist Bibliotherapy

- More by User

The Role of Schools in Improving Children’s Mental Health