- Criminal Justice

- Study Guides

- Functions of Criminal Law

- The Process of Criminal Justice

- The Politics of Criminal Justice

- Which Model Crime Control or Due Process

- The Structure of Criminal Justice

- Racial Disparities

- Is the Criminal Justice System Racist?

- Citizen Participation

- Rights Consciousness and Civil Liberties

- Part I Offenses

- Drugs and Crime

- Guns and Crime

- Does Gun Control Reduce Crime?

- Definitions of Crime

- Types of Crime

- Sources of Criminal Law

- The Nature of Criminal Law

- Legal Elements of a Crime

- Legal Defenses, Justifications for Crimes

- The Limits of Criminal Law

- Should Drugs Be Legalized?

- Developing the New Police

- Frontier Justice

- Progressive Police Reform

- Crime Control Decades (1919–1959)

- Policing the Social Crises of the 1960s

- Crime Control Revisited (1970s–1990s)

- Policing Colonial America

- Law Enforcement Goes High‐Tech

- Should Police Take DNA Samples?

- Police Systems

- Police Organization

- Police Strategies

- Does Community Policing Prevent Crime?

- The Nature of Police Work

- The Exclusionary Rule

- Fifth Amendment: Right to Remain Silent

- Citizens' Rights: A Barrier to Justice?

- Criminal Procedure and the Constitution

- The Right to Privacy

- Police Brutality

- Deadly Force

- Police Corruption

- Employment Discrimination

- Affirmative Action: A Tool for Justice?

- Police Perjury

- Federal Courts

- Heavy Caseloads and Delay

- Remove Judges Who Are “Soft on Crime”

- State Courts

- The Posttrial Process

- Should Plea Bargaining Be Abolished?

- Introducing Defendants' Rights

- The Pretrial Process

- The Trial Process

- Prosecutorial Discretion

- Important Relationships for Prosecutors

- Case‐Management Policies

- Prosecutorial Misconduct

- Headhunting: Effective in Organized-Crime Combat?

- Introducing the Prosecutors

- Types of Prosecutors

- Defense Strategies

- Ineffective Assistance of Counsel

- Do Most Defense Attorneys Distort Truth?

- Introducing the Defense Attorneys

- The Adversary Justice System

- Types of Defense

- Sentencing Statutes and Guidelines

- Should the Death Penalty Be Abolished?

- Theories of Punishment

- Types of Sentences

- Prisoners' Rights

- Can Imprisoning More Criminals Cut Crime?

- A Separate System for Juveniles

- Minorities in Juvenile Justice

- Myths About Juvenile Justice

- Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults?

- Juveniles' Responsibilities and Rights

Criminal law serves several purposes and benefits society in the following ways:

- Maintaining order . Criminal law provides predictability, letting people know what to expect from others. Without criminal law, there would be chaos and uncertainty.

Resolving disputes . The law makes it possible to resolve conflicts and disputes between quarreling citizens. It provides a peaceful, orderly way to handle grievances.

Protecting individuals and property . Criminal law protects citizens from criminals who would inflict physical harm on others or take their worldly goods. Because of the importance of property in capitalist America, many criminal laws are intended to punish those who steal.

Providing for smooth functioning of society . Criminal law enables the government to collect taxes, control pollution, and accomplish other socially beneficial tasks.

Safeguarding civil liberties . Criminal law protects individual rights.

Previous The Nature of Criminal Law

Next Legal Elements of a Crime

What Is Criminal Law and How to Write Criminal Law Essay

Sign up now.

A criminal law essay is a research paper or report based on a comprehensive review of criminal law regulations. Criminal law is a challenging field to specialize in with so many aspects: the state, court hearings, criminal records, rights of criminals, facts and figures. And on top of everything, writing criminal law essays with perfection is like fighting a case before becoming a lawyer. Students must go through a complete cycle of the process to finish their law degree.

A criminal law essay examines specific cases in which a legislative controversy arises. Criminal law, in particular, is an operational branch of state law that aids in the preservation of society’s safety and confidence. A significant amount of crime and violence threatens the balance and comfort of people’s lives in today’s world. Criminal lawyers are the people who take up such cases to regulate the sphere.

The variety of punishments demonstrates the negative consequences of illegal behaviors and how necessary it is for maintaining discipline and safety. Therefore, it is crucial to consider criminal law as a fundamental foundation for modernization and the provision of security and stability to the country’s citizens.

Law students are frequently asked to write essays, either on topics that have been assigned to them or on issues that they have chosen or in response to specific questions. Mainly in a law degree, the exam includes an essay section, meaning a student has to prepare for both the exam and the essay. In addition, they have to learn about the types of crime, criminal behavior, punishment and sentence period. Therefore, criminal law essay assignments are proposed to ensure students are familiar with their states and country’s laws and know how to apply them in a criminal case.

Even though law students are highly qualified and trained to take on any challenge, they sometimes need help with their studies. Unfortunately, students are left alone to fight the academic pressure which leads to a lot of stress. If you are in the same boat, you can reach out to us for law essay help and avail of professional service.

However, if the student wants to build a law essay from scratch, there will be different requirements depending on the university, and the type of essay students are writing. The first thing to constitute a first-class law essay is to gather all the information. Students must understand the differences between criminal law, criminology, legislation and the different types of criminal law. So, let’s learn about the types and what it takes to structure a criminal law essay.

Types of Criminal Law

Criminal law covers all sorts of crimes, but the crimes are mainly divided into two following types:

- Misdemeanor

Criminal Law – Felony

Severe criminal cases are recorded under this type of criminal law. The punishment for severely offensive cases, types of crimes and criminals is imprisonment for a lifetime or execution. Felony crimes include murder, arson, manslaughter, burglary, tax evasion, aggravated assault, kidnapping, fraud, blackmail, obstruction of justice, forgery, treason, etc.

Criminal Law – Misdemeanor

Misdemeanor type of criminal law looks after less serious crimes, and the punishment for misdemeanor crimes is lesser than a felony. The sentence or punishment such criminals have to face comes in terms of a fine or 6 months to a year in prison. Misdemeanor crimes include reckless driving, public intoxication, property destruction, petty theft, disorderly conduct, trespassing, etc.

Moreover, criminal law is divided into five other categories to recognize the crimes effectively.

Private or Individual Crimes such crimes are recorded when an individual harms another person on a personal level.

Immature Crimes are such criminal acts in which the nearest suspect only helped the criminal in the crime or offensive acts that were never accomplished.

Property Crimes are criminal cases involving interfering with another’s property.

Constitutional Crimes are the acts banned by the states, for example, drugs, alcohol, playing poker, or other societal issues.

Finance Crimes are also known as “white-collar” crimes. It mostly includes transferring illegal money to foreign bank accounts, frauds, embezzlement, tax evasion, blackmail, etc.

We’ve talked about the types and categories of crimes and criminal law. So, let’s jump into the depth of the law of crime and learn how we can structure a criminal law essay.

The Criminal Law Essay Structure

The structure of a simple criminal law essay is similar to another type of essay. However, the essay aims to influence individuals on a particular plan, and the paper helps the legislation regulate social behavior or limit whatever is threatening society. We are sure your professor must’ve taught you how to write a good persuasive essay . To help law students, we’ve penned down some guidelines to help you write a great criminal law essay. Also, you can hire a professional to help you with your criminal law essay. After all, your grades matter the most, don’t they?

· Start Early on the Essay

It is crucial to start as early as possible because writing a criminal law essay is not an essay game. Waiting until the submission date only adds unnecessary stress and drama to your academic life. The more you’ll delay your essay, the less time you’ll have to write your essay. This will reflect in the completed work and will cost you your grades. So, start early and make sure you have time to add references to your essay and perfect your work with proofreading and editing.

· Read, Analyze and then Deconstruct the Question

Do not start with your criminal law essay until you completely understand the question being asked. Instead, take some time to break the question down into sections and seek advice from your professors and professionals for law essay help. Again, it will be very helpful for you to have an expert by your side to guide you through the writing process.

· Research and Investigate

Case or subject investigation is the most important and difficult part of writing a criminal law essay. The data you are taking to support your paper must come from a known and relevant source. The references should be up-to-date and reliable if you want to produce a first-class essay. The more authoritative a source is, the higher your score will be. When possible, choose primary over secondary materials.

· Write an Effective Essay Introduction

An introduction is something that impresses the audience and makes them read your entire paper. If you have a loose introduction and the paper’s outline is not well-written, your readers will lose their interest. So, provide the readers with a statement, an answer to the problem, and a map that explains your essay’s motives. Your introduction should be detailed, not lengthy, meaning it should simply define the object of your paper but in simple language.

· Counter-Argument to Your Statement

This will demonstrate that you have a broad understanding of the subject. The counter-arguments list the claims of other authors and explains why your paper is better and how your paper solves a social issue.

· Conclude Your Criminal Law Essay

Mention all of the main points you’ve made in a few sentences. In your conclusion, reaffirm your answer to the law essay question to ensure that your statement is processed clearly.

We hope you have a fair understanding of criminal law essays and how it is constructed. But we still have some more information for you. So, let us talk about some topics and what it takes to come up with good criminal law essays if your professors don’t assign you a topic.

How to Come Up With Interesting Criminal Law Essay Topic Ideas

Choosing the right topic is the first step toward writing a criminal law essay because it determines the scope of the research. Usually, the professor or instructor provides students with the topic or argument statement as these essays are much more detailed than regular papers. However, if the professor allows you to choose your topic or argument statement, make sure you don’t just pick any topic.

You will have an opportunity to describe your point of view on something you strongly believe in, and your essay is one way to do so. The most effective criminal law essay writing tip for selecting a topic is considering its current relevance and your interest. First and foremost, you should review the entire course and highlight the most interesting criminal law areas and criminal cases studied during the period.

Going through the course and other research will assist you in narrowing your field of interest and selecting a topic. Your essay topic allows you to enrich or practice skills in specific areas. Also, it helps you consider the issue’s importance on a social level and its current status. Furthermore, the topic should either analyze current events, view case studies or look into the implementation of existing national legislation.

Moreover, if you’re having trouble deciding on a topic for your criminal law essay, you can pick one from the list below

- Human Rights Violations

- The Origins of Capital Punishment

- Distributive Justice and Criminal Justice

- Has Identity Theft Reached Its Peak?

- Witness Protection Program

- What Motivates People to Commit Crimes

- Aggravating and Mitigating Factors in Criminal Sentencing

- Types of Bail; Bail and Bonds

- Amendments for Crime Victims

- Receiving Protection for Testimony in a Criminal Case

smith - AUTHOR

Recent post.

June 13, 2022 June 13, 2022

11 Tips to Enhance Your Legal Writing Skills

May 13, 2022 June 15, 2022

Facts about Law School Degrees You Won’t Hear Anywhere

May 6, 2022 May 9, 2022

Useful Steps to Write A Law Research Proposal

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Purposes of Criminal Laws, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 749

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

This paper addresses the purposes of criminal laws, in the context of Criminal Justice. The paper is divided into three distinct parts (i) Introduction and Background (ii) The purpose of Criminal law, with emphasis on deterrence, punishment and retribution (iii) Concluding remarks considering how effective criminal law is in the US constitution. The paper addresses the important question of – how effective are criminal laws in terms of applying measures of justice in the USA?

Introduction and Background

Criminal law may be considered as the foundation of the criminal justice legal system in the USA. But all is important because it defines the legal steps that the police must follow, leading to an arrest. Further, it defines the trial procedures in court and the subsequent penalties that may follow. Although most people associate criminal law with violent crime like murder, robbery, rape, assault etc. nevertheless, each state has a different interpretation of this. For example in Florida. It is illegal to light in the ignited tobacco product in an elevator. Alabama makes a wrestling unlawful. In Louisiana, you risk 10 years in prison for stealing an alligator. Despite the humorous overtones, this is a serious business in the criminal justice system is essential for the well-being of all US citizens. The nature of “criminal law is such that a crime is whatever the Lord declares to be a criminal offense and publishers with a penalty.” (Lippman, 2006).

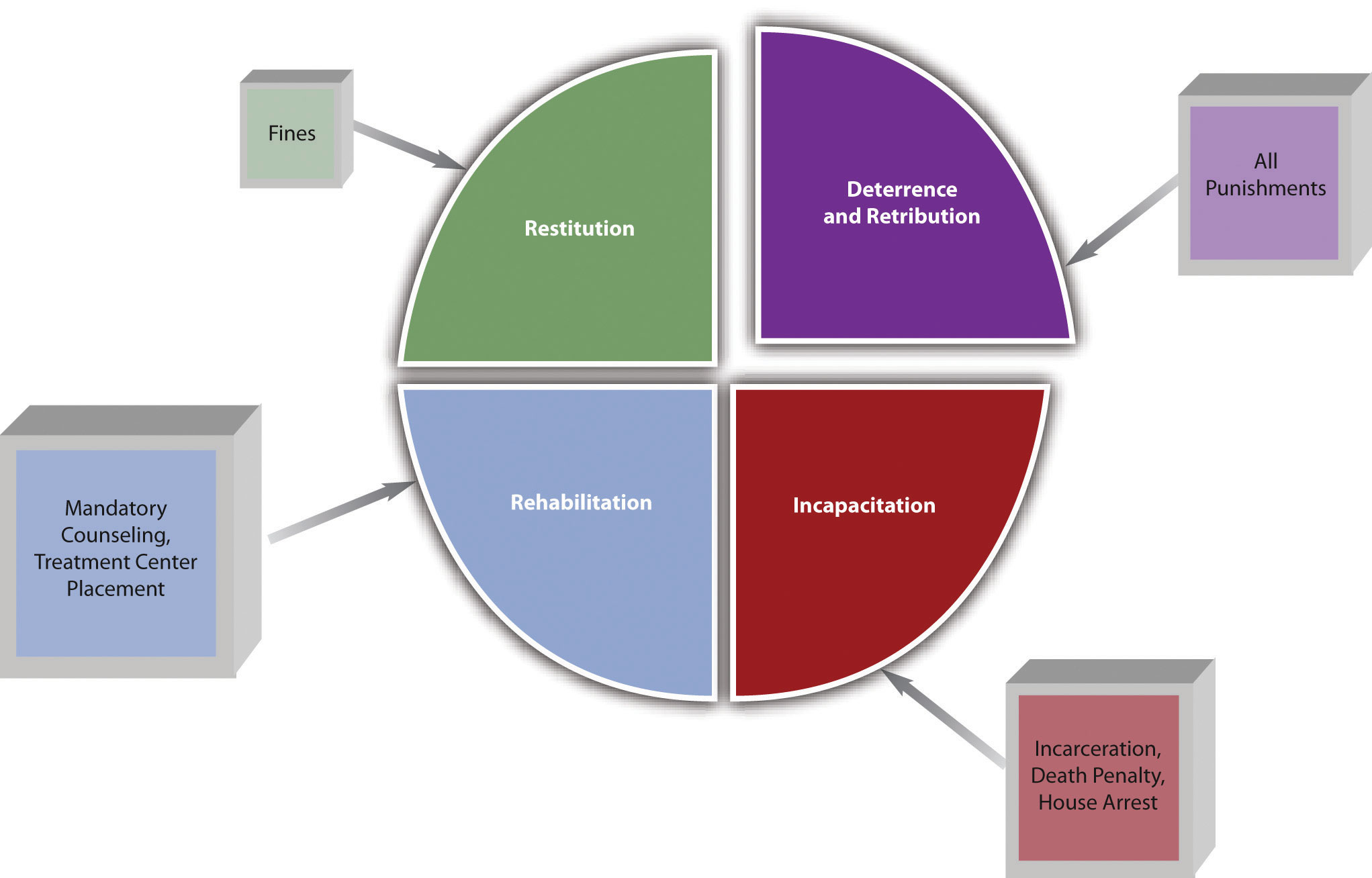

HG World-wide legal directory defines Criminal law as being ” Criminal Law or penal law, involves prosecution by the government of a person for an act that has been classified as a crime. It is the body of statutory and common law that deals with crime and the legal punishment of criminal offenses. There are four theories of criminal justice: punishment, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation. It is believed that by imposing sanctions for the crime, society can achieve justice and a peaceable social order.” (HG.org, 2010).

The purpose of criminal law

The main purposes of criminal laws are to protect and serve its citizens. Essentially there are two main functions: [1] to provide a means that expresses human or society morality and [2] to teach social boundaries that we all must live within and to punish those offenders who resort to criminal behaviour and reject these rules. These procedures both safeguard and protect the Bill of Rights and the American Constitution.

Four theories of Criminal Justice Punishment

There are essentially four theories of Criminal Justice punishment:

- Punishment : Punishment is essentially placed into two different classifications. The first of these being utilitarian or the means to deter or dissuade those from future wrong doings and the second retributive where it seeks to exact a suitable punishment for the crime committed.

- Deterrence : May be considered a utilitarian punishment. ” Specific deterrence means that the punishment should prevent the same person from committing crimes. Specific deterrence works in two ways. First, an offender may be put in jail or prison to physically prevent her from committing another crime for a specified period. Second, this incapacitation is designed to be so unpleasant that it will discourage the offender from repeating her criminal behaviour” (Legal Dictionary, 2010).

- Incapacitation : Relates to the concept of imprisonment of the offender and removing them from society where they cannot repeat the offense to society. It is a means of protecting society from the Criminal

- Rehabilitation : Relates to changing the behavioural pattern of the detainee whilst in prison. The aim being to change the behaviour of the prisoner such that the offender may be released back into Society and continue to make a useful and meaningful contribution without reverting to criminal behaviour.

Concluding remarks

The criminal justice system in the USA is an essential part of the legal apparatus for maintaining law and order in society. It is necessary to have a set of legal standards and regulations to protect the majority of citizens from the minority that seek to disrupt and displaying violent and criminal behaviour to other members of society. In addition, it also provides a means of transforming such criminal elements into law-abiding citizens and prevent the moral decline of society into a state of anarchy, where only the strong survive.

Works Cited

HG.org. (2010). Criminal Law – Guide to Criminal and Penal Law . Retrieved 7 8, 2010, from HG.org: http://www.hg.org/crime.html

Legal Dictionary. (2010). punishment . Retrieved 7 8, 2010, from Legal Dictionary: http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Punishment,+Criminal

Lippman. (2006). The nature purpose and constitutional context pf criminal law. In Lippman, The nature purpose and constitutional context pf criminal law (pp. 1-23). New York: Sage Publications.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Global Sustainable Energy Markets, Term Paper Example

Sociological Definitions, Dissertation - Discussion Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.5 The Purposes of Punishment

Learning objective.

- Ascertain the effects of specific and general deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, retribution, and restitution.

Punishment has five recognized purposes: deterrence , incapacitation , rehabilitation , retribution , and restitution .

Specific and General Deterrence

Deterrence prevents future crime by frightening the defendant or the public . The two types of deterrence are specific and general deterrence . Specific deterrence applies to an individual defendant . When the government punishes an individual defendant, he or she is theoretically less likely to commit another crime because of fear of another similar or worse punishment. General deterrence applies to the public at large. When the public learns of an individual defendant’s punishment, the public is theoretically less likely to commit a crime because of fear of the punishment the defendant experienced. When the public learns, for example, that an individual defendant was severely punished by a sentence of life in prison or the death penalty, this knowledge can inspire a deep fear of criminal prosecution.

Incapacitation

Incapacitation prevents future crime by removing the defendant from society. Examples of incapacitation are incarceration, house arrest, or execution pursuant to the death penalty.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation prevents future crime by altering a defendant’s behavior. Examples of rehabilitation include educational and vocational programs, treatment center placement, and counseling. The court can combine rehabilitation with incarceration or with probation or parole. In some states, for example, nonviolent drug offenders must participate in rehabilitation in combination with probation, rather than submitting to incarceration (Ariz. Rev. Stat., 2010). This lightens the load of jails and prisons while lowering recidivism , which means reoffending.

Retribution

Retribution prevents future crime by removing the desire for personal avengement (in the form of assault, battery, and criminal homicide, for example) against the defendant. When victims or society discover that the defendant has been adequately punished for a crime, they achieve a certain satisfaction that our criminal procedure is working effectively, which enhances faith in law enforcement and our government.

Restitution

Restitution prevents future crime by punishing the defendant financially . Restitution is when the court orders the criminal defendant to pay the victim for any harm and resembles a civil litigation damages award. Restitution can be for physical injuries, loss of property or money, and rarely, emotional distress. It can also be a fine that covers some of the costs of the criminal prosecution and punishment.

Figure 1.4 Different Punishments and Their Purpose

Key Takeaways

- Specific deterrence prevents crime by frightening an individual defendant with punishment. General deterrence prevents crime by frightening the public with the punishment of an individual defendant.

- Incapacitation prevents crime by removing a defendant from society.

- Rehabilitation prevents crime by altering a defendant’s behavior.

- Retribution prevents crime by giving victims or society a feeling of avengement.

- Restitution prevents crime by punishing the defendant financially.

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- What is one difference between criminal victims’ restitution and civil damages?

- Read Campbell v. State , 5 S.W.3d 693 (1999). Why did the defendant in this case claim that the restitution award was too high? Did the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals agree with the defendant’s claim? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11316909200521760089&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr .

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-901.01, accessed February 15, 2010, http://law.justia.com/arizona/codes/title13/00901-01.html .

Criminal Law Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 Motive and Criminal Liability

Author Webpage

- Published: March 2010

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Contrary to conventional wisdom, this chapter argues that the motive of the defendant is and ought to be relevant to his criminal liability. It attempts to show that motives are important to liability according to any philosophically plausible conception of the nature of motives. It discusses several respects in which motives are relevant to the substantive criminal law and traces some normative implications of the author's thesis.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Did you Miss the Free Art of Test Taking Lecture? That's okay, get your free mug anyway. Click here

Use Code and Save: $25WWFlash - Exam Writing Workshop - Attend Live in OC (or stream live) Sat. & Sun. April 6/7, 2024 9:30AM PT - 5PM PT

Item added to your cart

Whodunit solving the mystery of writing a first-rate criminal law essay exam.

I was leaving the post office one day and I saw a license plate that was an acronym for Nancy Drew. I stopped to admire the plate because it immediately took me back to when I was young and would voraciously read Nancy Drew mystery novels. It reminded me that reading the books taught me how to solve mysteries. As a civil litigation attorney, I regularly apply that skill in my practice because, as I go from one case to the next, I solve one mystery at a time.

Normally, the mystery is the extent of the wrongdoing by the opposing party. However, sometimes it is discovering the relevant facts that my client conveniently failed to share with me. Tapping into your inner sleuth will assist you with learning to write first-rate Criminal Law exam answers as well as answers in any other type of law school exam you may encounter.

Prepare to Solve Your Mystery

Preparation is essential to solving the mystery of writing a Criminal Law exam. As a law student, your preparation commences with reading and briefing all the assigned cases. This teaches you the law and how to reason. Further, it assists with preparing your study outline for the class. It also teaches you the discipline of IRAC, which is fundamental to law exam writing.

Fleming’s is in a powerful position to assist with your law school exam preparation - as demonstrated by one of our law students receiving the only known perfect score on a Criminal Law Bar exam. The student who wrote the answer implemented what Fleming’s teaches when answering a Criminal Law exam, and the Bar Examiners rewarded him with a perfect 100 score for his presentation.

So that you can see Fleming’s law exam methods and techniques at work for yourself, I recommend reading our recent article about this student’s impressive accomplishment:

Bar Examiners Give Fleming’s Law Student a Perfect Score on His Essay Exam Answer

The question, along with the student’s perfectly scored answer, is appended at the end of the article. You, too, can achieve this result with Fleming’s at your side.

Every Sleuth Needs a Partner

As Nancy Drew had her Bess Marvin, every sleuth needs a partner. For law students, legal study supplements are your Bess Marvin sidekick. Fleming’s has a wide array of supplements that can assist law students with course substantive law outlines as well as fail-safe methods and techniques for law exam writing .

I highly recommend Fleming’s Sail Through Law School with The Exam Solution® for Criminal Law because it provides a four-hour substantive law lecture, a substantive law outline, and three essay exams with sample California Bar exam answers. This is all you need to tie together everything about the subject that you are learning in the classroom. Reviewing Bar exam answers is invaluable because they assist with how to format, weigh issues, and write persuasive analysis. One of my former students conveyed that the resources from this series really helped her prepare for her recent midterms.

Identify the Suspects

Now that you are ready to commence your law exam writing, you must start with identifying your suspects. Therefore, the first thing you do is read the call of the question. Read it at least twice because it is imperative to understand the scope of your investigation. You must headnote and write on each call of the question separately because failure to do so will result in a failing grade.

Examine the Crime Scene

The next step of your investigation is to examine the crime scene, which is the fact pattern for the exam. Read it twice – concentrate solely on the facts. Read it again to prepare your issue outline as outlining is imperative to your success on the exam. It tells you how many issues you have to write on, which ones are major and minor, and how to allocate your writing time so you do not run short in finishing before time is called.

Map Out the Scope of Your Investigation

When writing law school or California Bar exam answers, you must write on the issues in the order that they are spotted in the fact pattern. You strategize this when outlining the exam, which is why outlining is so crucial to your success.

When drafting your outline make four columns, one for each part of IRAC, to ensure that you write your answer in an orderly manner - including all the required crimes and defenses.

The first column is for the issue, the next for the rule, then the facts for your analysis/application, and the last column for the conclusion. You should abbreviate whenever possible to keep your outline time between 15 – 20 minutes.

The example below for outlining the issue of robbery is taken from Fleming’s Writing Workbook p. 43.

Now that you have examined the crime scene and created your outline, you are ready to write your essay answer. Think about what you want to say before beginning to write. This will help you formulate your thoughts and prevent you from rambling once you get started.

Write Your Investigation Report

A successful answer applies the relevant facts to each element of the rule to persuade the reader as to why the crime or defense succeeds or fails. What you are trying to do is answer the “why” or “why not” regarding each element of the rule, using the facts from the exam.

As an initial matter, you must weigh the issues to ensure you have enough time for major issues such as homicide. A classic Criminal Law California Bar exam will contain a number of crimes and a homicide at the end. Generally, when there is a homicide, you will need 15 – 20 minutes to write on it because you must write on each required issue/subpart. If you run out of time to write a full homicide analysis, you will likely fail the exam because it is a heavily weighted issue.

A superior answer will analyze the arguments of each party. You want to argue on behalf of the State first because it is prosecuting the case. Then you write the counterarguments for the defendant.

Writing both sides will set you apart and increase your score because the majority of students only write on behalf of the prosecution. Developing this skill is essential as an attorney because you must always anticipate the arguments of the opposing party.

There are certain issues that require writing on the common law rule as well as the modern rule or Model Penal Code. Burglary is a classic example. You must analyze common law burglary as well as the modern law distinctions because the burden of proof is lower. When writing on the insanity issue, you must always write on all four insanity excuses.

You must write a one-sentence conclusion regarding each issue on the exam as well as an overall conclusion if required by the call of the question.

Justice Is Served

Writing a first-rate Criminal Law exam takes hard work and discipline. This can be achieved by stepping into the exam to spot and solve each mystery of whether or not the crime or defense succeeds or fails.

Justice will be served when you write a first-class answer and receive your desired passing score. This will put you one step closer to going from law student to lawyer.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.

MIA > Archive > Pashukanis

Evgeny Pashukanis

Marksistskaia teoriia gosudarstva i prava , pp.9-44 in E. B. Pashukanis (ed.), Uchenie o gosudarstve i prave (1932), Partiinoe Izd., Moscow. From Evgeny Pashukanis, Selected Writings on Marxism and Law (eds. P. Beirne & R. Sharlet), London & New York 1980, pp.273-301. Translated by Peter B. Maggs . Copyright © Peter B. Maggs. Published here by kind permission of the translator. Downloaded from home.law.uiuc.edu/~pmaggs/pashukanis.htm Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive .

Introductory Note

In the winter of 1929-1930, during the first Five Year Plan, the national economy of the USSR underwent dramatic and violent ruptures with the inauguration of forced collectivization and rapid heavy industrialization. Concomitantly, it seemed, the Party insisted on the reconstruction and realignment of the appropriate superstructures in conformity with the effectuation of these new social relations of production. In this spirit Pashukanis was no longer criticized but now overtly attacked in the struggle on the “legal front”. In common with important figures in other intellectual disciplines, such as history, in late 1930 Pashukanis undertook a major self-criticism which was qualitatively different from the incremental changes to his work that he had produced earlier. During the following year, 1931, Pashukanis outlined this theoretical reconstruction in his speech to the first conference of Marxist jurists, a speech entitled Towards a Marxist-Leninist Theory of Law . The first results appeared a year later in a collective volume The Doctrine of State and Law .

Chapter I of this collective work is translated below, The Marxist Theory of State and Law , and was written by Pashukanis himself It should be noted that this volume exemplifies the formal transformations which occurred in Soviet legal scholarship during this heated period. Earlier, Pashukanis and other jurists had authored their own monographs; the trend was now towards a collective scholarship which promised to maximize individual safety. The source of authority for much of the work that ensued increasingly became the many expressions of Stalin’s interpretation of Bolshevik history, class struggle and revisionism, most notably his Problems of Leninism . Last, but not least, the language and vocabulary of academic discourse in the 1920s had been rich, open-ended and diverse, and varied tremendously with the personal preferences of the individual author; this gave way to a standardized and simplified style of prose devoid of nuance and ambiguity, and which was very much in keeping with the new theoretical content which comprised official textbooks on the theory of state and law. The reader will perhaps discover that The Marxist Theory of State and Law is a text imbued with these tensions. Pashukanis’ radical reconceptualization of the unity of form and content, and of the ultimate primacy of the relations of production, is without doubt to be preferred to his previous notions. But this is a preference guided by the advantages of editorial hindsight, and we feel that we cannot now distinguish between those reconceptualizations which Pashukanis may actually have intended and those which were produced by the external pressures of political opportunism.

CHAPTER I Socio-economic Formations, State, and Law

1. the doctrine of socio-economic formations as a basis for the marxist theory of state and law.

The doctrine of state and law is part of a broader whole, namely, the complex of sciences which study human society. The development of these sciences is in turn determined by the history of society itself, i.e. by the history of class struggle.

It has long since been noted that the most powerful and fruitful catalysts which foster the study of social phenomena are connected with revolutions. The English Revolution of the seventeenth century gave birth to the basic directions of bourgeois social thought, and forcibly advanced the scientific, i.e. materialist, understanding of social phenomena.

It suffices to mention such a work as Oceana – by the English writer Harrington, and which appeared soon after the English Revolution of the seventeenth century – in which changes in political structure are related to the changing distribution of landed property. It suffices to mention the work of Barnave – one of the architects of the great French Revolution – who in the same way sought explanations of political struggle and the political order in property relations. In studying bourgeois revolutions, French restorationist historians – Guizot, Mineaux and Thierry – concluded that the leitmotif of these revolutions was the class struggle between the third estate (i.e. the bourgeoisie) and the privileged estates of feudalism and their monarch. This is why Marx, in his well-known letter to Weydemeyer, indicates that the theory of the class struggle was known before him. “As far as I am concerned”, he wrote,

no credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society, or the struggle between them. Long before me bourgeois historians had described the historical development of this class struggle, and bourgeois economists the economic anatomy of the classes.

What I did that was new was to prove: (1) that the existence of classes is only bound up with particular historical forms of struggle in the development of production ...; (2) that the class struggle inevitably leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat; (3) that this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and the establishment of a classless society. [1]

[ Section 2 omitted – eds. ]

Top of the page

3. The class type of state and the form of government

The doctrine of socio-economic formations is particularly important to Marx’s theory of state and law, because it provides the basis for the precise and scientific delineation of the different types of state and the different systems of law.

Bourgeois political and juridical theorists attempt to establish a classification of political and legal forms without scientific criteria; not from the class essence of the forms, but from more or less external characteristics. Bourgeois theorists of the state, assiduously avoiding the question of the class nature of the state, propose every type of artificial and scholastic definition and conceptual distinction. For instance, in the past, textbooks on the state divided the state into three “elements”: territory, population and power.

Some scholars go further. Kellen – one of the most recent Swedish theorists of the state – distinguishes five elements or phenomena of the state: territory, people, economy, society and, finally, the state as the formal legal subject of power. All these definitions and distinctions of elements, or aspects of the state, are no more than a scholastic game of empty concepts since the main point is absent: the division of society into classes, and class domination. Of course, the state cannot exist without population, or territory, or economy, or society. This is an incontrovertible truth. But, at the same time, it is true that all these “elements” existed at that stage of development when there was no state. Equally, classless communist society – having territory, population and an economy – will do without the state since the necessity of class suppression will disappear.

The feature of power, or coercive power, also tells one exactly nothing. Lenin, in his polemic of the 1890s with Struve asserted that: “he most incorrectly sees the distinguishing feature of the state as coercive power. Coercive power exists in every human society – both in the tribal structure and in the family, but there was no state.” And further, Lenin concludes: “The distinguishing feature of the state is the existence of a separate class of people in whose hands power is concentrated. Obviously, no one could use the term ‘State’ in reference to a community in which the ‘organization of order’ is administered in turn by all of its members.” [2]

Struve’s position, according to which the distinguishing feature of a state is coercive power, was not without reason termed “professorial” by Lenin. Every bourgeois science of the state is full of conclusions on the essence of this coercive power. Disguising the class character of the state, bourgeois scholars interpret this coercion in a purely psychological sense. “For power and subordination”, wrote one of the Russian bourgeois jurists (Lazarevsky), “two elements are necessary: the consciousness of those exercising power that they have the right to obedience, and the consciousness of the subordinates that they must obey.”

From this, Lazarevsky and other bourgeois jurists reached the following conclusion: state power is based upon the general conviction of citizens that a specific state has the right to issue its decrees and laws. Thus, the real fact-concentration of the means of force and coercion in the hands of a particular class-is concealed and masked by the ideology of the bourgeoisie. While the feudal landowning state sanctified its power by the authority of religion, the bourgeoisie uses the fetishes of statute and law. In connection with this, we also find the theory of bourgeois jurists-which now has been adopted in its entirety by the Social Democrats whereby the state is viewed as an agency acting in the interests of the whole society. “If the source of state power derives from class”, wrote another of the bourgeois jurists (Magaziner), “then to fulfil its tasks it must stand above the class struggle. Formally, it is the arbiter of the class struggle, and even more than that: it develops the rules of this struggle.”

It is precisely this false theory of the supra-class nature of the state that is used for the justification of the treacherous policy of the Social Democrats. In the name “of the general interest”, Social Democrats deprive the unemployed of their welfare payments, help in reducing wages, and encourage shooting at workers’ demonstrations.

Not wishing to recognize the basic fact, i.e. that states differ according to their class basis, bourgeois theorists of the state concentrate all their attention on various forms of government. But this difference by itself is worthless. Thus, for instance, in ancient Greece and ancient Rome we have the most varied forms of government. But all the transitions from monarchy to republic, from aristocracy to democracy, which we observe there, do not destroy the basic fact that these states, regardless of their different forms, were slave-owning states. The apparatus of coercion, however it was organized, belong to the slave-owners and assured their mastery over the slaves with the help of armed force, assured the right of the slave-owners to dispose of the labour and personality of the slaves, to exploit them, to commit any desired act of violence against them.

Distinguishing between the form of rule and the class essence of the state is particularly important for the correct strategy of the working class in its struggle with capitalism. Proceeding from this distinction, we establish that to the extent that private property and the power of capital remain untouchable, to this extent the democratic form of government does not change the essence of the matter. Democracy with the preservation of capitalist exploitation will always be democracy for the minority, democracy for the propertied; it will always mean the exploitation and subjugation of the great mass of the working people. Therefore theorists of the Second International such as Kautsky, who contrast “democracy” in general with “dictatorship”, entirely refuse to consider their class nature. They replace Marxism with vulgar legal dogmatism, and act as the scholarly champions and lackeys of capitalism.

The different forms of rule had already arisen in slave-owning society. Basically, they consist of the following types: the monarchic state with an hereditary head, and the republic where power is elective and where there are no offices which pass by inheritance. In addition, aristocracy, or the power of a minority (i.e. a state where participation in the administration of the state is limited by law to a definite and rather narrow circle of privileged persons) is distinguished from democracy (or, literally, the rule of the people), i.e. a state where by law all take part in deciding public affairs either directly or through elected representatives. The distinction between monarchy, aristocracy and democracy had already been established by the Greek philosopher Aristotle in the fourth century. All the modern bourgeois theories of the state could add little to this classification.

Actually the significance of one form or another can be gleaned only by taking into account the concrete historical conditions under which it arose and existed, and only in the context of the class nature of a specific state. Attempts to establish any general abstract laws of the movement of state forms – with which bourgeois theorists of the state have often been occupied – have nothing in common with science.

In particular, the change of the form of government depends on concrete historical conditions, on the condition of the class struggle, and on how relationships are formed between the ruling class and the subordinate class, and also within the ruling class itself

The forms of government may change although the class nature of the state remains the same. France, in the course of the nineteenth century, and after the revolution of 1830 until the present time, was a constitutional monarchy, an empire and a republic, and the rule of the bourgeois capitalist state was maintained in all three of these forms. Conversely, the same form of government (for instance a democratic republic) which was encountered in antiquity as one of the variations of the slave-owning state, is in our time one of the forms of capitalist domination.

Therefore, in studying any state, it is very important primarily to examine not its external form but its internal class content, placing the concrete historical conditions of the class struggle at the very basis of scrutiny.

The question of the relationship between the class type of the state and the form of government is still very little developed. In the bourgeois theory of the state this question not only could not be developed, but could not even be correctly posed, because bourgeois science always tries to disguise the class nature of all states, and in particular the class nature of the capitalist state. Often therefore, bourgeois theorists of the state, without analysis, conflate characteristics relating to the form of government and characteristics relating to the class nature of the state.

As an example one may adduce the classification which is proposed in one of the newest German encyclopaedias of legal science.