Narrative Analysis 101

Everything you need to know to get started

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD)| Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to research, the host of qualitative analysis methods available to you can be a little overwhelming. In this post, we’ll unpack the sometimes slippery topic of narrative analysis . We’ll explain what it is, consider its strengths and weaknesses , and look at when and when not to use this analysis method.

Overview: Narrative Analysis

- What is narrative analysis (simple definition)

- The two overarching approaches

- The strengths & weaknesses of narrative analysis

- When (and when not) to use it

- Key takeaways

What Is Narrative Analysis?

Simply put, narrative analysis is a qualitative analysis method focused on interpreting human experiences and motivations by looking closely at the stories (the narratives) people tell in a particular context.

In other words, a narrative analysis interprets long-form participant responses or written stories as data, to uncover themes and meanings . That data could be taken from interviews, monologues, written stories, or even recordings. In other words, narrative analysis can be used on both primary and secondary data to provide evidence from the experiences described.

That’s all quite conceptual, so let’s look at an example of how narrative analysis could be used.

Let’s say you’re interested in researching the beliefs of a particular author on popular culture. In that case, you might identify the characters , plotlines , symbols and motifs used in their stories. You could then use narrative analysis to analyse these in combination and against the backdrop of the relevant context.

This would allow you to interpret the underlying meanings and implications in their writing, and what they reveal about the beliefs of the author. In other words, you’d look to understand the views of the author by analysing the narratives that run through their work.

The Two Overarching Approaches

Generally speaking, there are two approaches that one can take to narrative analysis. Specifically, an inductive approach or a deductive approach. Each one will have a meaningful impact on how you interpret your data and the conclusions you can draw, so it’s important that you understand the difference.

First up is the inductive approach to narrative analysis.

The inductive approach takes a bottom-up view , allowing the data to speak for itself, without the influence of any preconceived notions . With this approach, you begin by looking at the data and deriving patterns and themes that can be used to explain the story, as opposed to viewing the data through the lens of pre-existing hypotheses, theories or frameworks. In other words, the analysis is led by the data.

For example, with an inductive approach, you might notice patterns or themes in the way an author presents their characters or develops their plot. You’d then observe these patterns, develop an interpretation of what they might reveal in the context of the story, and draw conclusions relative to the aims of your research.

Contrasted to this is the deductive approach.

With the deductive approach to narrative analysis, you begin by using existing theories that a narrative can be tested against . Here, the analysis adopts particular theoretical assumptions and/or provides hypotheses, and then looks for evidence in a story that will either verify or disprove them.

For example, your analysis might begin with a theory that wealthy authors only tell stories to get the sympathy of their readers. A deductive analysis might then look at the narratives of wealthy authors for evidence that will substantiate (or refute) the theory and then draw conclusions about its accuracy, and suggest explanations for why that might or might not be the case.

Which approach you should take depends on your research aims, objectives and research questions . If these are more exploratory in nature, you’ll likely take an inductive approach. Conversely, if they are more confirmatory in nature, you’ll likely opt for the deductive approach.

Need a helping hand?

Strengths & Weaknesses

Now that we have a clearer view of what narrative analysis is and the two approaches to it, it’s important to understand its strengths and weaknesses , so that you can make the right choices in your research project.

A primary strength of narrative analysis is the rich insight it can generate by uncovering the underlying meanings and interpretations of human experience. The focus on an individual narrative highlights the nuances and complexities of their experience, revealing details that might be missed or considered insignificant by other methods.

Another strength of narrative analysis is the range of topics it can be used for. The focus on human experience means that a narrative analysis can democratise your data analysis, by revealing the value of individuals’ own interpretation of their experience in contrast to broader social, cultural, and political factors.

All that said, just like all analysis methods, narrative analysis has its weaknesses. It’s important to understand these so that you can choose the most appropriate method for your particular research project.

The first drawback of narrative analysis is the problem of subjectivity and interpretation . In other words, a drawback of the focus on stories and their details is that they’re open to being understood differently depending on who’s reading them. This means that a strong understanding of the author’s cultural context is crucial to developing your interpretation of the data. At the same time, it’s important that you remain open-minded in how you interpret your chosen narrative and avoid making any assumptions .

A second weakness of narrative analysis is the issue of reliability and generalisation . Since narrative analysis depends almost entirely on a subjective narrative and your interpretation, the findings and conclusions can’t usually be generalised or empirically verified. Although some conclusions can be drawn about the cultural context, they’re still based on what will almost always be anecdotal data and not suitable for the basis of a theory, for example.

Last but not least, the focus on long-form data expressed as stories means that narrative analysis can be very time-consuming . In addition to the source data itself, you will have to be well informed on the author’s cultural context as well as other interpretations of the narrative, where possible, to ensure you have a holistic view. So, if you’re going to undertake narrative analysis, make sure that you allocate a generous amount of time to work through the data.

When To Use Narrative Analysis

As a qualitative method focused on analysing and interpreting narratives describing human experiences, narrative analysis is usually most appropriate for research topics focused on social, personal, cultural , or even ideological events or phenomena and how they’re understood at an individual level.

For example, if you were interested in understanding the experiences and beliefs of individuals suffering social marginalisation, you could use narrative analysis to look at the narratives and stories told by people in marginalised groups to identify patterns , symbols , or motifs that shed light on how they rationalise their experiences.

In this example, narrative analysis presents a good natural fit as it’s focused on analysing people’s stories to understand their views and beliefs at an individual level. Conversely, if your research was geared towards understanding broader themes and patterns regarding an event or phenomena, analysis methods such as content analysis or thematic analysis may be better suited, depending on your research aim .

Let’s recap

In this post, we’ve explored the basics of narrative analysis in qualitative research. The key takeaways are:

- Narrative analysis is a qualitative analysis method focused on interpreting human experience in the form of stories or narratives .

- There are two overarching approaches to narrative analysis: the inductive (exploratory) approach and the deductive (confirmatory) approach.

- Like all analysis methods, narrative analysis has a particular set of strengths and weaknesses .

- Narrative analysis is generally most appropriate for research focused on interpreting individual, human experiences as expressed in detailed , long-form accounts.

If you’d like to learn more about narrative analysis and qualitative analysis methods in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog here . Alternatively, if you’re looking for hands-on help with your project, take a look at our 1-on-1 private coaching service .

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

Thanks. I need examples of narrative analysis

Here are some examples of research topics that could utilise narrative analysis:

Personal Narratives of Trauma: Analysing personal stories of individuals who have experienced trauma to understand the impact, coping mechanisms, and healing processes.

Identity Formation in Immigrant Communities: Examining the narratives of immigrants to explore how they construct and negotiate their identities in a new cultural context.

Media Representations of Gender: Analysing narratives in media texts (such as films, television shows, or advertisements) to investigate the portrayal of gender roles, stereotypes, and power dynamics.

Where can I find an example of a narrative analysis table ?

Please i need help with my project,

how can I cite this article in APA 7th style?

please mention the sources as well.

My research is mixed approach. I use interview,key_inforamt interview,FGD and document.so,which qualitative analysis is appropriate to analyze these data.Thanks

Which qualitative analysis methode is appropriate to analyze data obtain from intetview,key informant intetview,Focus group discussion and document.

I’ve finished my PhD. Now I need a “platform” that will help me objectively ascertain the tacit assumptions that are buried within a narrative. Can you help?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Narrative Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Narrative Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Narrative Analysis

Definition:

Narrative analysis is a qualitative research methodology that involves examining and interpreting the stories or narratives people tell in order to gain insights into the meanings, experiences, and perspectives that underlie them. Narrative analysis can be applied to various forms of communication, including written texts, oral interviews, and visual media.

In narrative analysis, researchers typically examine the structure, content, and context of the narratives they are studying, paying close attention to the language, themes, and symbols used by the storytellers. They may also look for patterns or recurring motifs within the narratives, and consider the cultural and social contexts in which they are situated.

Types of Narrative Analysis

Types of Narrative Analysis are as follows:

Content Analysis

This type of narrative analysis involves examining the content of a narrative in order to identify themes, motifs, and other patterns. Researchers may use coding schemes to identify specific themes or categories within the text, and then analyze how they are related to each other and to the overall narrative. Content analysis can be used to study various forms of communication, including written texts, oral interviews, and visual media.

Structural Analysis

This type of narrative analysis focuses on the formal structure of a narrative, including its plot, character development, and use of literary devices. Researchers may analyze the narrative arc, the relationship between the protagonist and antagonist, or the use of symbolism and metaphor. Structural analysis can be useful for understanding how a narrative is constructed and how it affects the reader or audience.

Discourse Analysis

This type of narrative analysis focuses on the language and discourse used in a narrative, including the social and cultural context in which it is situated. Researchers may analyze the use of specific words or phrases, the tone and style of the narrative, or the ways in which social and cultural norms are reflected in the narrative. Discourse analysis can be useful for understanding how narratives are influenced by larger social and cultural structures.

Phenomenological Analysis

This type of narrative analysis focuses on the subjective experience of the narrator, and how they interpret and make sense of their experiences. Researchers may analyze the language used to describe experiences, the emotions expressed in the narrative, or the ways in which the narrator constructs meaning from their experiences. Phenomenological analysis can be useful for understanding how people make sense of their own lives and experiences.

Critical Analysis

This type of narrative analysis involves examining the political, social, and ideological implications of a narrative, and questioning its underlying assumptions and values. Researchers may analyze the ways in which a narrative reflects or reinforces dominant power structures, or how it challenges or subverts those structures. Critical analysis can be useful for understanding the role that narratives play in shaping social and cultural norms.

Autoethnography

This type of narrative analysis involves using personal narratives to explore cultural experiences and identity formation. Researchers may use their own personal narratives to explore issues such as race, gender, or sexuality, and to understand how larger social and cultural structures shape individual experiences. Autoethnography can be useful for understanding how individuals negotiate and navigate complex cultural identities.

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying themes or patterns that emerge from the data, and then interpreting these themes in relation to the research question. Researchers may use a deductive approach, where they start with a pre-existing theoretical framework, or an inductive approach, where themes are generated from the data itself.

Narrative Analysis Conducting Guide

Here are some steps for conducting narrative analysis:

- Identify the research question: Narrative analysis begins with identifying the research question or topic of interest. Researchers may want to explore a particular social or cultural phenomenon, or gain a deeper understanding of a particular individual’s experience.

- Collect the narratives: Researchers then collect the narratives or stories that they will analyze. This can involve collecting written texts, conducting interviews, or analyzing visual media.

- Transcribe and code the narratives: Once the narratives have been collected, they are transcribed into a written format, and then coded in order to identify themes, motifs, or other patterns. Researchers may use a coding scheme that has been developed specifically for the study, or they may use an existing coding scheme.

- Analyze the narratives: Researchers then analyze the narratives, focusing on the themes, motifs, and other patterns that have emerged from the coding process. They may also analyze the formal structure of the narratives, the language used, and the social and cultural context in which they are situated.

- Interpret the findings: Finally, researchers interpret the findings of the narrative analysis, and draw conclusions about the meanings, experiences, and perspectives that underlie the narratives. They may use the findings to develop theories, make recommendations, or inform further research.

Applications of Narrative Analysis

Narrative analysis is a versatile qualitative research method that has applications across a wide range of fields, including psychology, sociology, anthropology, literature, and history. Here are some examples of how narrative analysis can be used:

- Understanding individuals’ experiences: Narrative analysis can be used to gain a deeper understanding of individuals’ experiences, including their thoughts, feelings, and perspectives. For example, psychologists might use narrative analysis to explore the stories that individuals tell about their experiences with mental illness.

- Exploring cultural and social phenomena: Narrative analysis can also be used to explore cultural and social phenomena, such as gender, race, and identity. Sociologists might use narrative analysis to examine how individuals understand and experience their gender identity.

- Analyzing historical events: Narrative analysis can be used to analyze historical events, including those that have been recorded in literary texts or personal accounts. Historians might use narrative analysis to explore the stories of survivors of historical traumas, such as war or genocide.

- Examining media representations: Narrative analysis can be used to examine media representations of social and cultural phenomena, such as news stories, films, or television shows. Communication scholars might use narrative analysis to examine how news media represent different social groups.

- Developing interventions: Narrative analysis can be used to develop interventions to address social and cultural problems. For example, social workers might use narrative analysis to understand the experiences of individuals who have experienced domestic violence, and then use that knowledge to develop more effective interventions.

Examples of Narrative Analysis

Here are some examples of how narrative analysis has been used in research:

- Personal narratives of illness: Researchers have used narrative analysis to examine the personal narratives of individuals living with chronic illness, to understand how they make sense of their experiences and construct their identities.

- Oral histories: Historians have used narrative analysis to analyze oral histories to gain insights into individuals’ experiences of historical events and social movements.

- Children’s stories: Researchers have used narrative analysis to analyze children’s stories to understand how they understand and make sense of the world around them.

- Personal diaries : Researchers have used narrative analysis to examine personal diaries to gain insights into individuals’ experiences of significant life events, such as the loss of a loved one or the transition to adulthood.

- Memoirs : Researchers have used narrative analysis to analyze memoirs to understand how individuals construct their life stories and make sense of their experiences.

- Life histories : Researchers have used narrative analysis to examine life histories to gain insights into individuals’ experiences of migration, displacement, or social exclusion.

Purpose of Narrative Analysis

The purpose of narrative analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of the stories that individuals tell about their experiences, identities, and beliefs. By analyzing the structure, content, and context of these stories, researchers can uncover patterns and themes that shed light on the ways in which individuals make sense of their lives and the world around them.

The primary purpose of narrative analysis is to explore the meanings that individuals attach to their experiences. This involves examining the different elements of a story, such as the plot, characters, setting, and themes, to identify the underlying values, beliefs, and attitudes that shape the story. By analyzing these elements, researchers can gain insights into the ways in which individuals construct their identities, understand their relationships with others, and make sense of the world.

Narrative analysis can also be used to identify patterns and themes across multiple stories. This involves comparing and contrasting the stories of different individuals or groups to identify commonalities and differences. By analyzing these patterns and themes, researchers can gain insights into broader cultural and social phenomena, such as gender, race, and identity.

In addition, narrative analysis can be used to develop interventions that address social and cultural problems. By understanding the stories that individuals tell about their experiences, researchers can develop interventions that are tailored to the unique needs of different individuals and groups.

Overall, the purpose of narrative analysis is to provide a rich, nuanced understanding of the ways in which individuals construct meaning and make sense of their lives. By analyzing the stories that individuals tell, researchers can gain insights into the complex and multifaceted nature of human experience.

When to use Narrative Analysis

Here are some situations where narrative analysis may be appropriate:

- Studying life stories: Narrative analysis can be useful in understanding how individuals construct their life stories, including the events, characters, and themes that are important to them.

- Analyzing cultural narratives: Narrative analysis can be used to analyze cultural narratives, such as myths, legends, and folktales, to understand their meanings and functions.

- Exploring organizational narratives: Narrative analysis can be helpful in examining the stories that organizations tell about themselves, their histories, and their values, to understand how they shape the culture and practices of the organization.

- Investigating media narratives: Narrative analysis can be used to analyze media narratives, such as news stories, films, and TV shows, to understand how they construct meaning and influence public perceptions.

- Examining policy narratives: Narrative analysis can be helpful in examining policy narratives, such as political speeches and policy documents, to understand how they construct ideas and justify policy decisions.

Characteristics of Narrative Analysis

Here are some key characteristics of narrative analysis:

- Focus on stories and narratives: Narrative analysis is concerned with analyzing the stories and narratives that people tell, whether they are oral or written, to understand how they shape and reflect individuals’ experiences and identities.

- Emphasis on context: Narrative analysis seeks to understand the context in which the narratives are produced and the social and cultural factors that shape them.

- Interpretive approach: Narrative analysis is an interpretive approach that seeks to identify patterns and themes in the stories and narratives and to understand the meaning that individuals and communities attach to them.

- Iterative process: Narrative analysis involves an iterative process of analysis, in which the researcher continually refines their understanding of the narratives as they examine more data.

- Attention to language and form : Narrative analysis pays close attention to the language and form of the narratives, including the use of metaphor, imagery, and narrative structure, to understand the meaning that individuals and communities attach to them.

- Reflexivity : Narrative analysis requires the researcher to reflect on their own assumptions and biases and to consider how their own positionality may shape their interpretation of the narratives.

- Qualitative approach: Narrative analysis is typically a qualitative research method that involves in-depth analysis of a small number of cases rather than large-scale quantitative studies.

Advantages of Narrative Analysis

Here are some advantages of narrative analysis:

- Rich and detailed data : Narrative analysis provides rich and detailed data that allows for a deep understanding of individuals’ experiences, emotions, and identities.

- Humanizing approach: Narrative analysis allows individuals to tell their own stories and express their own perspectives, which can help to humanize research and give voice to marginalized communities.

- Holistic understanding: Narrative analysis allows researchers to understand individuals’ experiences in their entirety, including the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they occur.

- Flexibility : Narrative analysis is a flexible research method that can be applied to a wide range of contexts and research questions.

- Interpretive insights: Narrative analysis provides interpretive insights into the meanings that individuals attach to their experiences and the ways in which they construct their identities.

- Appropriate for sensitive topics: Narrative analysis can be particularly useful in researching sensitive topics, such as trauma or mental health, as it allows individuals to express their experiences in their own words and on their own terms.

- Can lead to policy implications: Narrative analysis can provide insights that can inform policy decisions and interventions, particularly in areas such as health, education, and social policy.

Limitations of Narrative Analysis

Here are some of the limitations of narrative analysis:

- Subjectivity : Narrative analysis relies on the interpretation of researchers, which can be influenced by their own biases and assumptions.

- Limited generalizability: Narrative analysis typically involves in-depth analysis of a small number of cases, which limits its generalizability to broader populations.

- Ethical considerations: The process of eliciting and analyzing narratives can raise ethical concerns, particularly when sensitive topics such as trauma or abuse are involved.

- Limited control over data collection: Narrative analysis often relies on data that is already available, such as interviews, oral histories, or written texts, which can limit the control that researchers have over the quality and completeness of the data.

- Time-consuming: Narrative analysis can be a time-consuming research method, particularly when analyzing large amounts of data.

- Interpretation challenges: Narrative analysis requires researchers to make complex interpretations of data, which can be challenging and time-consuming.

- Limited statistical analysis: Narrative analysis is typically a qualitative research method that does not lend itself well to statistical analysis.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and...

ANOVA (Analysis of variance) – Formulas, Types...

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data

- Handling qualitative data

- Transcripts

- Field notes

- Survey data and responses

- Visual and audio data

- Data organization

- Data coding

- Coding frame

- Auto and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Qualitative data analysis

- Content analysis

Thematic analysis

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

- Introduction

Types of narrative research

Research methods for a narrative analysis, narrative analysis, considerations for narrative analysis.

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- Qualitative data interpretation

- Qualitative analysis software

Narrative analysis in research

Narrative analysis is an approach to qualitative research that involves the documentation of narratives both for the purpose of understanding events and phenomena and understanding how people communicate stories.

Let's look at the basics of narrative research, then examine the process of conducting a narrative inquiry and how ATLAS.ti can help you conduct a narrative analysis.

Qualitative researchers can employ various forms of narrative research, but all of these distinct approaches utilize perspectival data as the means for contributing to theory.

A biography is the most straightforward form of narrative research. Data collection for a biography generally involves summarizing the main points of an individual's life or at least the part of their history involved with events that a researcher wants to examine. Generally speaking, a biography aims to provide a more complete record of an individual person's life in a manner that might dispel any inaccuracies that exist in popular thought or provide a new perspective on that person’s history. Narrative researchers may also construct a new biography of someone who doesn’t have a public or online presence to delve deeper into that person’s history relating to the research topic.

The purpose of biographies as a function of narrative inquiry is to shed light on the lived experience of a particular person that a more casual examination of someone's life might overlook. Newspaper articles and online posts might give someone an overview of information about any individual. At the same time, a more involved survey or interview can provide sufficiently comprehensive knowledge about a person useful for narrative analysis and theoretical development.

Life history

This is probably the most involved form of narrative research as it requires capturing as much of the total human experience of an individual person as possible. While it involves elements of biographical research, constructing a life history also means collecting first-person knowledge from the subject through narrative interviews and observations while drawing on other forms of data , such as field notes and in-depth interviews with others.

Even a newspaper article or blog post about the person can contribute to the contextual meaning informing the life history. The objective of conducting a life history is to construct a complete picture of the person from past to present in a manner that gives your research audience the means to immerse themselves in the human experience of the person you are studying.

Oral history

While all forms of narrative research rely on narrative interviews with research participants, oral histories begin with and branch out from the individual's point of view as the driving force of data collection .

Major events like wars and natural disasters are often observed and described at scale, but a bird's eye view of such events may not provide a complete story. Oral history can assist researchers in providing a unique and perhaps unexplored perspective from in-depth interviews with a narrator's own words of what happened, how they experienced it, and what reasons they give for their actions. Researchers who collect this sort of information can then help fill in the gaps common knowledge may not have grasped.

The objective of an oral history is to provide a perspective built on personal experience. The unique viewpoint that personal narratives can provide has the potential to raise analytical insights that research methods at scale may overlook. Narrative analysis of oral histories can hence illuminate potential inquiries that can be addressed in future studies.

Whatever your research, get it done with ATLAS.ti.

From case study research to interviews, turn to ATLAS.ti for your qualitative research. Click here for a free trial.

To conduct narrative analysis, researchers need a narrative and research question . A narrative alone might make for an interesting story that instills information, but analyzing a narrative to generate knowledge requires ordering that information to identify patterns, intentions, and effects.

Narrative analysis presents a distinctive research approach among various methodologies , and it can pose significant challenges due to its inherent interpretative nature. Essentially, this method revolves around capturing and examining the verbal or written accounts and visual depictions shared by individuals. Narrative inquiry strives to unravel the essence of what is conveyed by closely observing the content and manner of expression.

Furthermore, narrative research assumes a dual role, serving both as a research technique and a subject of investigation. Regarded as "real-world measures," narrative methods provide valuable tools for exploring actual societal issues. The narrative approach encompasses an individual's life story and the profound significance embedded within their lived experiences. Typically, a composite of narratives is synthesized, intermingling and mutually influencing each other.

Designing a research inquiry

Sometimes, narrative research is less about the storyteller or the story they are telling than it is about generating knowledge that contributes to a greater understanding of social behavior and cultural practices. While it might be interesting or useful to hear a comedian tell a story that makes their audience laugh, a narrative analysis of that story can identify how the comedian constructs their narrative or what causes the audience to laugh.

As with all research, a narrative inquiry starts with a research question that is tied to existing relevant theory regarding the object of analysis (i.e., the person or event for which the narrative is constructed). If your research question involves studying racial inequalities in university contexts, for example, then the narrative analysis you are seeking might revolve around the lived experiences of students of color. If you are analyzing narratives from children's stories, then your research question might relate to identifying aspects of children's stories that grab the attention of young readers. The point is that researchers conducting a narrative inquiry do not do so merely to collect more information about their object of inquiry. Ultimately, narrative research is tied to developing a more contextualized or broader understanding of the social world.

Data collection

Having crafted the research questions and chosen the appropriate form of narrative research for your study, you can start to collect your data for the eventual narrative analysis.

Needless to say, the key point in narrative research is the narrative. The story is either the unit of analysis or the focal point from which researchers pursue other methods of research. Interviews and observations are great ways to collect narratives. Particularly with biographies and life histories, one of the best ways to study your object of inquiry is to interview them. If you are conducting narrative research for discourse analysis, then observing or recording narratives (e.g., storytelling, audiobooks, podcasts) is ideal for later narrative analysis.

Triangulating data

If you are collecting a life history or an oral history, then you will need to rely on collecting evidence from different sources to support the analysis of the narrative. In research, triangulation is the concept of drawing on multiple methods or sources of data to get a more comprehensive picture of your object of inquiry.

While a narrative inquiry is constructed around the story or its storyteller, assertions that can be made from an analysis of the story can benefit from supporting evidence (or lack thereof) collected by other means.

Even a lack of supporting evidence might be telling. For example, suppose your object of inquiry tells a story about working minimum wage jobs all throughout college to pay for their tuition. Looking for triangulation, in this case, means searching through records and other forms of information to support the claims being put forth. If it turns out that the storyteller's claims bear further warranting - maybe you discover that family or scholarships supported them during college - your analysis might uncover new inquiries as to why the story was presented the way it was. Perhaps they are trying to impress their audience or construct a narrative identity about themselves that reinforces their thinking about who they are. The important point here is that triangulation is a necessary component of narrative research to learn more about the object of inquiry from different angles.

Conduct data analysis for your narrative research with ATLAS.ti.

Dedicated research software like ATLAS.ti helps the researcher catalog, penetrate, and analyze the data generated in any qualitative research project. Start with a free trial today.

This brings us to the analysis part of narrative research. As explained above, a narrative can be viewed as a straightforward story to understand and internalize. As researchers, however, we have many different approaches available to us for analyzing narrative data depending on our research inquiry.

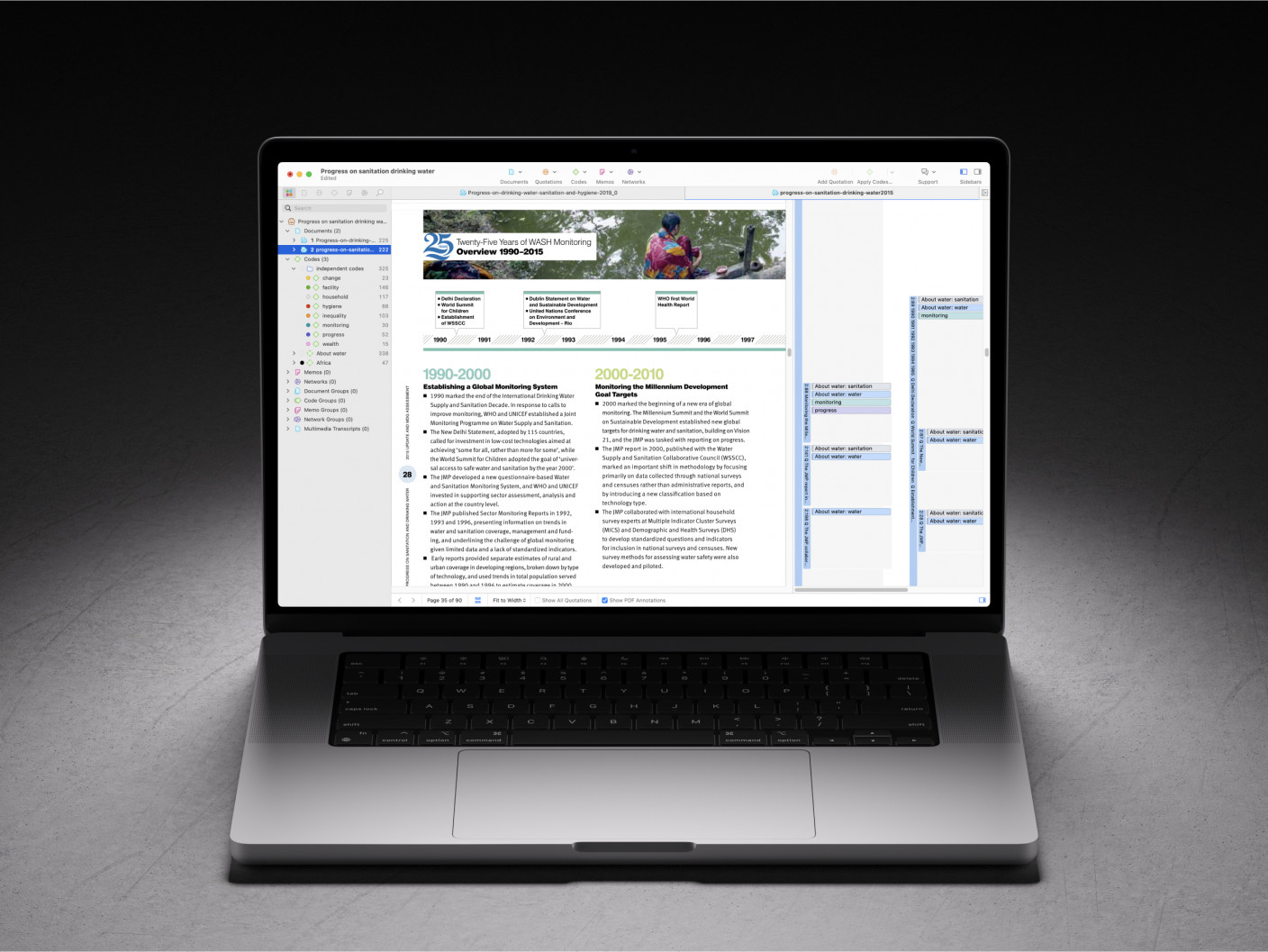

In this section, we will examine some of the most common forms of analysis while looking at how you can employ tools in ATLAS.ti to analyze your qualitative data .

Qualitative research often employs thematic analysis , which refers to a search for commonly occurring themes that appear in the data. The important point of thematic analysis in narrative research is that the themes arise from the data produced by the research participants. In other words, the themes in a narrative study are strongly based on how the research participants see them rather than focusing on how researchers or existing theory see them.

ATLAS.ti can be used for thematic analysis in any research field or discipline. Data in narrative research is summarized through the coding process , where the researcher codes large segments of data with short, descriptive labels that can succinctly describe the data thematically. The emerging patterns among occurring codes in the perspectival data thus inform the identification of themes that arise from the collected narratives.

Structural analysis

The search for structure in a narrative is less about what is conveyed in the narrative and more about how the narrative is told. The differences in narrative forms ultimately tell us something useful about the meaning-making epistemologies and values of the people telling them and the cultures they inhabit.

Just like in thematic analysis, codes in ATLAS.ti can be used to summarize data, except that in this case, codes could be created to specifically examine structure by identifying the particular parts or moves in a narrative (e.g., introduction, conflict, resolution). Code-Document Analysis in ATLAS.ti can then tell you which of your narratives (represented by discrete documents) contain which parts of a common narrative.

It may also be useful to conduct a content analysis of narratives to analyze them structurally. English has many signal words and phrases (e.g., "for example," "as a result," and "suddenly") to alert listeners and readers that they are coming to a new step in the narrative.

In this case, both the Text Search and Word Frequencies tools in ATLAS.ti can help you identify the various aspects of the narrative structure (including automatically identifying discrete parts of speech) and the frequency in which they occur across different narratives.

Functional analysis

Whereas a straightforward structural analysis identifies the particular parts of a narrative, a functional analysis looks at what the narrator is trying to accomplish through the content and structure of their narrative. For example, if a research participant telling their narrative asks the interviewer rhetorical questions, they might be doing so to make the interviewer think or adopt the participant's perspective.

A functional analysis often requires the researcher to take notes and reflect on their experiences while collecting data from research participants. ATLAS.ti offers a dedicated space for memos , which can serve to jot down useful contextual information that the researcher can refer to while coding and analyzing data.

Dialogic analysis

There is a nuanced difference between what a narrator tries to accomplish when telling a narrative and how the listener is affected by the narrative. There may be an overlap between the two, but the extent to which a narrative might resonate with people can give us useful insights about a culture or society.

The topic of humor is one such area that can benefit from dialogic analysis, considering that there are vast differences in how cultures perceive humor in terms of how a joke is constructed or what cultural references are required to understand a joke.

Imagine that you are analyzing a reading of a children's book in front of an audience of children at a library. If it is supposed to be funny, how do you determine what parts of the book are funny and why?

The coding process in ATLAS.ti can help with dialogic analysis of a transcript from that reading. In such an analysis, you can have two sets of codes, one for thematically summarizing the elements of the book reading and one for marking when the children laugh.

The Code Co-Occurrence Analysis tool can then tell you which codes occur during the times that there is laughter, giving you a sense of what parts of a children's narrative might be funny to its audience.

Narrative analysis and research hold immense significance within the realm of social science research, contributing a distinct and valuable approach. Whether employed as a component of a comprehensive presentation or pursued as an independent scholarly endeavor, narrative research merits recognition as a distinctive form of research and interpretation in its own right.

Subjectivity in narratives

It is crucial to acknowledge that every narrative is intricately intertwined with its cultural milieu and the subjective experiences of the storyteller. While the outcomes of research are undoubtedly influenced by the individual narratives involved, a conscientious adherence to narrative methodology and a critical reflection on one's research can foster transparent and rigorous investigations, minimizing the potential for misunderstandings.

Rather than striving to perceive narratives through an objective lens, it is imperative to contextualize them within their sociocultural fabric. By doing so, an analysis can embrace the diverse array of narratives and enable multiple perspectives to illuminate a phenomenon or story. Embracing such complexity, narrative methodologies find considerable application in social science research.

Connecting narratives to broader phenomena

In employing narrative analysis, researchers delve into the intricate tapestry of personal narratives, carefully considering the multifaceted interplay between individual experiences and broader societal dynamics.

This meticulous approach fosters a deeper understanding of the intricate web of meanings that shape the narratives under examination. Consequently, researchers can uncover rich insights and discern patterns that may have remained hidden otherwise. These can provide valuable contributions to both theory and practice.

In summary, narrative analysis occupies a vital position within social science research. By appreciating the cultural embeddedness of narratives, employing a thoughtful methodology, and critically reflecting on one's research, scholars can conduct robust investigations that shed light on the complexities of human experiences while avoiding potential pitfalls and fostering a nuanced understanding of the narratives explored.

Turn to ATLAS.ti for your narrative analysis.

Researchers can rely on ATLAS.ti for conducting qualitative research. See why with a free trial.

Narrative Analysis

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Nicole L. Sharp 2 ,

- Rosalind A. Bye 2 &

- Anne Cusick 3

3064 Accesses

12 Citations

Narrative inquiry methods have much to offer within health and social research. They have the capacity to reveal the complexity of human experience and to understand how people make sense of their lives within social, cultural, and historical contexts. There is no set approach to undertaking a narrative inquiry, and a number of scholars have offered interpretations of narrative inquiry approaches. Various combinations have also been employed successfully in the literature. There are, however, limited detailed accounts of the actual techniques and processes undertaken during the analysis phase of narrative inquiry. This can make it difficult for researchers to know where to start (and stop) when they come to do narrative analysis. This chapter describes in detail the practical steps that can be undertaken within narrative analysis. Drawing on the work of Polkinghorne (Int J Qual Stud Educ. 8(1):5–23, 1995), both narrative analysis and paradigmatic analysis of narrative techniques are explored, as they offer equally useful insights for different purposes. Narrative analysis procedures reveal the constructed story of an individual participant, while paradigmatic analysis of narratives uses both inductive and deductive means to identify common and contrasting themes between stories. These analysis methods can be used separately, or in combination, depending on the aims of the research. Details from narrative inquiries conducted by the authors to reveal the stories of emerging adults with cerebral palsy, and families of adolescents with acquired brain inquiry, are used throughout the chapter to provide practical examples of narrative analysis techniques.

- Narrative analysis

- Social constructionism

- Analysis procedures

- Paradigmatic analysis of narratives

- Story analyst

- Storytellers

- Narrative inquiry

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80.

Article Google Scholar

Arnett JJ. Presidential address: the emergence of emerging adulthood: a personal history. Emerg Adulthood. 2014;2(3):155–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814541096 .

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disability prevalence and trends. Canberra: Author; 2003.

Google Scholar

Bailey DM, Jackson JM. Qualitative data analysis: challenges and dilemmas related to theory and method. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(1):57–65.

Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 6th ed. Boston: Pearson Education; 2007.

Bernheimer LP, Gallimore R, Weisner TS. Ecocultural theory as a context for the individual family service plan. J Early Interv. 1990;14(3):219–33.

Bleakley A. Stories as data, data as stories: making sense of narrative inquiry in clinical education. Med Educ. 2005;39(5):534–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02126.x .

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa .

Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage; 2013.

Brown J, Addington-Hall J. How people with motor neurone disease talk about living with their illness: a narrative study. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(2):200–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04588.x .

Bruner J. Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1985.

Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1990.

Carson A, Chabot C, Greyson D, Shannon K, Duff P, Shoveller J. A narrative analysis of the birth stories of early-age mothers. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39(6):816–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12518 .

Chase SE. Narrative inquiry: still a field in the making. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The sage handbook of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011. p. 421–34.

Clandinin DJ, Connelly FM. Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000.

Clandinin DJ, Raymond H. Note on narrating disability. Equity Excell Educ. 2006;39(2):101–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680500541176 .

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2014.

Cussen A, Howie L, Imms C. Looking to the future: adolescents with cerebral palsy talk about their aspirations – a narrative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(24):2103–10. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.672540 .

Davies N, Crowe M, Whitehead L. Establishing routines to cope with the loneliness associated with widowhood: a narrative analysis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23(8):532–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12339 .

Edwards SL. Narrative analysis: how students learn from stories of practice. Nurse Res. 2016;23(3):18–25.

Elliott J. Using narrative in social research: qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage; 2005.

Book Google Scholar

Ennals P, Howie L. Narrative inquiry and health research. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 3rd ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 105–20.

Frank AW. The wounded storyteller: body, illness and ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995.

Gallimore R, Bernheimer LP, Weisner TS. Family life is more than managing crisis: broadening the agenda of research on families adapting to childhood disability. In: Gallimore R, Bernheimer LP, MacMillan DL, Speece DL, Vaughn S, editors. Developmental perspectives on children with high-incidence disabilities. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. p. 55–80.

Gergen KJ. Realities and relationships: soundings in social construction. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1994.

Gergen KJ. An invitation to social construction. London: Sage; 1999.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967.

Goodley D, Tregaskis C. Storying disability and impairment: retrospective accounts of disabled family life. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(5):630–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285840 .

Holloway I. Vulnerable story telling: narrative research in nursing. J Res Nurs. 2007;12(6):703–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987107084669 .

Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. The active interview. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995.

Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Introduction: establishing a balance. In: Holstein JA, Gubrium JF, editors. Varieties of narrative analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012a. p. 1–12.

Chapter Google Scholar

Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Varieties of narrative analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012b.

Khan F, Baguley IJ, Cameron ID. Rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Med J Aust. 2003;178:290–5.

Kramp MK. Exploring life and experience through narrative inquiry. In: deMarrais KB, Lapan SD, editors. Foundations of research: methods of inquiry in education and the social sciences. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. p. 103–22.

Liamputtong, P. Researching the vulnerable: a guide to sensitive research methods. London: Sage; 2007.

Liamputtong P. Qualitative research methods. 4th ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2013.

McCance TV, McKenna HP, Boore JRP. Exploring caring using narrative methodology: an analysis of the approach. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(3):350–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01671.x .

McCormack C. Storying stories: a narrative approach to in-depth interview conversations. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2004;7(3):219–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570210166382 .

Mishler EG. Research interviewing: context and narrative. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1986.

Mishler EG. Models of narrative analysis: a typology. J Narrat Life Hist. 1995;5(2):87–123. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.5.2.01mod .

Overcash JA. Narrative research: a review of methodology and relevance to clinical practice. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48:179–84.

Papathomas A, Smith B, Lavallee D. Family experiences of living with an eating disorder: a narrative analysis. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(3):313–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314566608 .

Polkinghorne DE. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. New York: State University of New York Press; 1988.

Polkinghorne DE. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 1995;8(1):5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103 .

Reissman CK. Narrative analysis. Newbury Park: Sage; 1993.

Reissman CK. A short story about long stories. J Narrat Life Hist. 1997;7(1–4):155–8.

Reissman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008.

Schwandt T. The Sage dictionary of qualitative inquiry. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2007.

Serry T, Liamputtong P. Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS). In: Liamputtong P, editor. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 3rd ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 437–50.

Smith B, Sparkes AC. Narrative and its potential contribution to disability studies. Disabil Soc. 2008;23(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701725542 .

Smith B, Sparkes AC. Narrative analysis and sport and exercise psychology: understanding lives in diverse ways. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2009;10(2):279–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.07.012 .

Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990.

Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998.

Weisner TS. Ecocultural understanding of children’s developmental pathways. Hum Dev. 2002;45(4):275–81.

World Health Organisation. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

Ylijoki O-H. Master’s thesis writing from a narrative approach. Stud High Educ. 2001;26(1):21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070020030698 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, NSW, Australia

Nicole L. Sharp & Rosalind A. Bye

Faculty of Health Sciences, Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

Anne Cusick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicole L. Sharp .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Sharp, N.L., Bye, R.A., Cusick, A. (2019). Narrative Analysis. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_106

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_106

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Using narrative analysis in qualitative research

Last updated

7 March 2023

Reviewed by

Jean Kaluza

After spending considerable time and effort interviewing persons for research, you want to ensure you get the most out of the data you gathered. One method that gives you an excellent opportunity to connect with your data on a very human and personal level is a narrative analysis in qualitative research.

Master narrative analysis

Analyze your qualitative data faster and surface more actionable insights

- What is narrative analysis?

Narrative analysis is a type of qualitative data analysis that focuses on interpreting the core narratives from a study group's personal stories. Using first-person narrative, data is acquired and organized to allow the researcher to understand how the individuals experienced something.

Instead of focusing on just the actual words used during an interview, the narrative analysis also allows for a compilation of data on how the person expressed themselves, what language they used when describing a particular event or feeling, and the thoughts and motivations they experienced. A narrative analysis will also consider how the research participants constructed their narratives.

From the interview to coding , you should strive to keep the entire individual narrative together, so that the information shared during the interview remains intact.

Is narrative analysis qualitative or quantitative?

Narrative analysis is a qualitative research method.

Is narrative analysis a method or methodology?

A method describes the tools or processes used to understand your data; methodology describes the overall framework used to support the methods chosen. By this definition, narrative analysis can be both a method used to understand data and a methodology appropriate for approaching data that comes primarily from first-person stories.

- Do you need to perform narrative research to conduct a narrative analysis?

A narrative analysis will give the best answers about the data if you begin with conducting narrative research. Narrative research explores an entire story with a research participant to understand their personal story.

What are the characteristics of narrative research?

Narrative research always includes data from individuals that tell the story of their experiences. This is captured using loosely structured interviews . These can be a single interview or a series of long interviews over a period of time. Narrative research focuses on the construct and expressions of the story as experienced by the research participant.

- Examples of types of narratives

Narrative data is based on narratives. Your data may include the entire life story or a complete personal narrative, giving a comprehensive account of someone's life, depending on the researched subject. Alternatively, a topical story can provide context around one specific moment in the research participant's life.

Personal narratives can be single or multiple sessions, encompassing more than topical stories but not entire life stories of the individuals.

- What is the objective of narrative analysis?

The narrative analysis seeks to organize the overall experience of a group of research participants' stories. The goal is to turn people's individual narratives into data that can be coded and organized so that researchers can easily understand the impact of a certain event, feeling, or decision on the involved persons. At the end of a narrative analysis, researchers can identify certain core narratives that capture the human experience.

What is the difference between content analysis and narrative analysis?

Content analysis is a research method that determines how often certain words, concepts, or themes appear inside a sampling of qualitative data . The narrative analysis focuses on the overall story and organizing the constructs and features of a narrative.

What is the difference between narrative analysis and case study in qualitative research?

A case study focuses on one particular event. A narrative analysis draws from a larger amount of data surrounding the entire narrative, including the thoughts that led up to a decision and the personal conclusion of the research participant.

A case study, therefore, is any specific topic studied in depth, whereas narrative analysis explores single or multi-faceted experiences across time.

What is the difference between narrative analysis and thematic analysis?

A thematic analysis will appear as researchers review the available qualitative data and note any recurring themes. Unlike narrative analysis, which describes an entire method of evaluating data to find a conclusion, a thematic analysis only describes reviewing and categorizing the data.

- Capturing narrative data

Because narrative data relies heavily on allowing a research participant to describe their experience, it is best to allow for a less structured interview. Allowing the participant to explore tangents or analyze their personal narrative will result in more complete data.

When collecting narrative data, always allow the participant the time and space needed to complete their narrative.

- Methods of transcribing narrative data

A narrative analysis requires that the researchers have access to the entire verbatim narrative of the participant, including not just the word they use but the pauses, the verbal tics, and verbal crutches, such as "um" and "hmm."

As the entire way the story is expressed is part of the data, a verbatim transcription should be created before attempting to code the narrative analysis.

Video and audio transcription templates

- How to code narrative analysis

Coding narrative analysis has two natural start points, either using a deductive coding system or an inductive coding system. Regardless of your chosen method, it's crucial not to lose valuable data during the organization process.

When coding, expect to see more information in the code snippets.

- Types of narrative analysis

After coding is complete, you should expect your data to look like large blocks of text organized by the parts of the story. You will also see where individual narratives compare and diverge.

Inductive method

Using an inductive narrative method treats the entire narrative as one datum or one set of information. An inductive narrative method will encourage the research participant to organize their own story.

To make sense of how a story begins and ends, you must rely on cues from the participant. These may take the form of entrance and exit talks.

Participants may not always provide clear indicators of where their narratives start and end. However, you can anticipate that their stories will contain elements of a beginning, middle, and end. By analyzing these components through coding, you can identify emerging patterns in the data.

Taking cues from entrance and exit talk

Entrance talk is when the participant begins a particular set of narratives. You may hear expressions such as, "I remember when…," "It first occurred to me when…," or "Here's an example…."

Exit talk allows you to see when the story is wrapping up, and you might expect to hear a phrase like, "…and that's how we decided", "after that, we moved on," or "that's pretty much it."

Deductive method

Regardless of your chosen method, using a deductive method can help preserve the overall storyline while coding. Starting with a deductive method allows for the separation of narrative pieces without compromising the story's integrity.

Hybrid inductive and deductive narrative analysis

Using both methods together gives you a comprehensive understanding of the data. You can start by coding the entire story using the inductive method. Then, you can better analyze and interpret the data by applying deductive codes to individual parts of the story.

- How to analyze data after coding using narrative analysis

A narrative analysis aims to take all relevant interviews and organize them down to a few core narratives. After reviewing the coding, these core narratives may appear through a repeated moment of decision occurring before the climax or a key feeling that affected the participant's outcome.

You may see these core narratives diverge early on, or you may learn that a particular moment after introspection reveals the core narrative for each participant. Either way, researchers can now quickly express and understand the data you acquired.

- A step-by-step approach to narrative analysis and finding core narratives

Narrative analysis may look slightly different to each research group, but we will walk through the process using the Delve method for this article.

Step 1 – Code narrative blocks

Organize your narrative blocks using inductive coding to organize stories by a life event.

Example: Narrative interviews are conducted with homeowners asking them to describe how they bought their first home.

Step 2 – Group and read by live-event

You begin your data analysis by reading through each of the narratives coded with the same life event.

Example: You read through each homeowner's experience of buying their first home and notice that some common themes begin to appear, such as "we were tired of renting," "our family expanded to the point that we needed a larger space," and "we had finally saved enough for a downpayment."

Step 3 – Create a nested story structure

As these common narratives develop throughout the participant's interviews, create and nest code according to your narrative analysis framework. Use your coding to break down the narrative into pieces that can be analyzed together.

Example: During your interviews, you find that the beginning of the narrative usually includes the pressures faced before buying a home that pushes the research participants to consider homeownership. The middle of the narrative often includes challenges that come up during the decision-making process. The end of the narrative usually includes perspectives about the excitement, stress, or consequences of home ownership that has finally taken place.

Step 4 – Delve into the story structure

Once the narratives are organized into their pieces, you begin to notice how participants structure their own stories and where similarities and differences emerge.

Example: You find in your research that many people who choose to buy homes had the desire to buy a home before their circumstances allowed them to. You notice that almost all the stories begin with the feeling of some sort of outside pressure.

Step 5 – Compare across story structure

While breaking down narratives into smaller pieces is necessary for analysis, it's important not to lose sight of the overall story. To keep the big picture in mind, take breaks to step back and reread the entire narrative of a code block. This will help you remember how participants expressed themselves and ensure that the core narrative remains the focus of the analysis.

Example: By carefully examining the similarities across the beginnings of participants' narratives, you find the similarities in pressures. Considering the overall narrative, you notice how these pressures lead to similar decisions despite the challenges faced.

Divergence in feelings towards homeownership can be linked to positive or negative pressures. Individuals who received positive pressure, such as family support or excitement, may view homeownership more favorably. Meanwhile, negative pressures like high rent or peer pressure may cause individuals to have a more negative attitude toward homeownership.

These factors can contribute to the initial divergence in feelings towards homeownership.

Step 6 – Tell the core narrative

After carefully analyzing the data, you have found how the narratives relate and diverge. You may be able to create a theory about why the narratives diverge and can create one or two core narratives that explain the way the story was experienced.

Example: You can now construct a core narrative on how a person's initial feelings toward buying a house affect their feelings after purchasing and living in their first home.

Narrative analysis in qualitative research is an invaluable tool to understand how people's stories and ability to self-narrate reflect the human experience. Qualitative data analysis can be improved through coding and organizing complete narratives. By doing so, researchers can conclude how humans process and move through decisions and life events.

Learn more about qualitative transcription software

Get started today.

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Research Design Review

A discussion of qualitative & quantitative research design, navigating narrative research & the depths of the lived experience.

The following is a modified excerpt from Applied Qualitative Research Design: A Total Quality Framework Approach (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015, pp. 298-300).

The belief in narrative research is that it is the narrated story—whether told orally, via some form of text or documents, and/or through the use of visual data (e.g., photographs, video, drawings)—that allows researchers to learn about individuals, society, and history, and that, indeed, “narrative inquiry [is] the study of experience as story” (Clandinin, Pushor, & Orr, 2007, p. 22).

For the most part, there are three (not mutually exclusive) ways to consider narrative inquiry, by the type of:

- Narrative being studied: for example, life history, life story, biography, autobiography, or autoethnography.

- Analytical approach used by the researcher: for example, thematic, structural, dialogical/performance, or visual (Riessman, 2008).

- Scholarly discipline applied to the research: for example, psychology, sociology, or education.

The variations of narrative research across fields of study demonstrate that there is no one way to think about narrative inquiry and, indeed, the three delineated types of approaches—narrative, analytical, and discipline—are often co-mingled. For example, various factions of psychology have embraced the use of narrative: with heroin addicts to understand “how individuals phenomenologically wrestle with decisions at crucial transition points in their lives” (Singer, 2013, p. 46); in identity research, by which people’s life stories can be analyzed from multiple perspectives, including the “small stories” within the “big stories” (Bamberg & Georgakopoulou, 2008), as well as the conditions that shape their stories and how the stories shape their life experiences (Esteban-Guitart, 2012); and to explore the connection between social stigma (e.g., not being accepted, being the target of discrimination) and intimacy in same-sex relationships (Frost, 2013).

Sociologists such as Cederberg (2014) have considered the biographical narratives of migrants and how public discourse potentially molds these narratives of their lived experiences. And Luttrell (2003), also a sociologist, elicited visual and performance narratives from pregnant teenagers who were better able to express their life stories in these less structured approaches than in response to conventional narrative interviews, explaining that “the more I stayed out of their way, the more the girls would talk and free associate while doing these self-representations activities. For me, this meant giving up my more immediate desire to ask questions, make sense of, or put order into the girls’ creative expression or their conversations” (p. 150).

Scholars from many other disciplines are also using narrative research. For example, educational researchers such as Clandinin and Connelly (1998) used “narrative histories” to study school reform by investigating the school as a “living place” where “teachers and the principal come to the landscape living and telling a complex set of interwoven stories of themselves as teachers, of children in this school, of the community” (p. 160). Austin and Carpenter (2008) used narrative research with mothers of children who are “disruptive” in the classroom (i.e., who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) to explore the “harsh and judgmental treatment” these mothers experience “from medical professionals, teachers, friends and family” (p. 379).

Examples of the anthropological uses of narrative include such work as the analysis of the narrative elements in Eskimo folktales (Colby, 1973), and the use of historical narratives as “cultural tools” to examine the presentation of events in post-Soviet Russian textbooks (Wertsch, 2000). Communication and health care researchers have explored “illness narratives” by way of online conversations among people suffering from drug addiction in order to understand their life experiences and the effectiveness of online support (Jodlowski, Sharf, Nguyen, Haidet, & Woodard, 2007). Scholars in social work have demonstrated the challenges and benefits of conducting narrative research with marginalized segments of the population, such as teenage mothers (Harlow, 2009), young people from the child welfare system (Martin, 1998), and heterosexual serodiscordant couples (Poindexter, 2003). And, social scientists engaged in performance studies, such as Madison (2003), have used the performing arts to communicate the stories of significant political moments in history.

Navigating the waters of narrative research is a rewarding experience that takes the researcher into the uncharted depths of human behavior and attitudes to exact meaning and bring about change for the social good.

* The critical role that storytelling plays in research methods is also discussed in this Research Design Review article.

Austin, H., & Carpenter, L. (2008). Troubled, troublesome, troubling mothers: The dilemma of difference in women’s personal motherhood narratives. Narrative Inquiry , 18 (2), 378–392.

Bamberg, M., & Georgakopoulou, A. (2008). Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. Text & Talk , 28 (3), 377–396.

Cederberg, M. (2014). Public discourses and migrant stories of integration and inequality: Language and power in biographical narratives. Sociology , 48 (1), 133–149.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1998). Stories to live by: Narrative understandings of school reform. Curriculum Inquiry , 28 (2), 149–164.

Clandinin, D. J., Pushor, D., & Orr, A. M. (2007). Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education , 58 (1), 21–35.

Colby, B. N. (1973). A partial grammar of Eskimo folktales. American Anthropologist , 75 (3), 645–662.

Esteban-Guitart, M. (2012). Towards a multimethodological approach to identification of funds of identity, small stories and master narratives. Narrative Inquiry , 22 (1), 173–180.

Frost, D. M. (2013). Stigma and intimacy in same-sex relationships: A narrative approach. Qualitative Psychology , 1 (S), 49–61.

Harlow, E. (2009). Eliciting narratives of teenage pregnancy in the UK: Reflexively exploring some of the methodological challenges. Qualitative Social Work , 8 (2), 211–228.

Jodlowski, D., Sharf, B. F., Nguyen, L. C., Haidet, P., & Woodard, L. D. (2007). “Screwed for life”: Examining identification and division in addiction narratives. Communication & Medicine , 4 (1), 15–26.

Luttrell, W. (2003). Pregnant bodies, fertile minds: Gender, race and the schooling of pregnant teens . New York: Routledge.

Madison, D. S. (2003). Performance, personal narratives, and the politics of possibility. In Y. S. Lincoln & N. K. Denzin (Eds.), Turning points in qualitative research: Tying knots in a handkerchief (Vol. 3, pp. 469–486). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Martin, F. E. (1998). Tales of transition: Self-narrative and direct scribing in exploring care-leaving. Child & Family Social Work , 3 (1), 1–12.

Poindexter, C. C. (2003). Sex, drugs, and love among the middle aged: A case study of a serodiscordant heterosexual couple coping with HIV. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions , 3 (2), 57–83.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Singer, J. A. (2013). Living in the amber cloud: A life story analysis of a heroin addict. Qualitative Psychology , 1 (S), 33–48.

Wertsch, J. V. (2000). Narratives as cultural tools in sociocultural analysis: Official history in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia. Ethos , 28 (4), 511–533.

Image captured from: http://compasscrossingdigitalmarketing.blogspot.com/2016/05/odds-are-pretty-good-that-if-youve-got.html

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: A Multi-method Approach in Qualitative Research | Research Design Review

- Pingback: The In-depth Interview Method: 12 Articles on Design & Implementation | Research Design Review

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed