- Most accessed

Apiospora arundinis, a panoply of carbohydrate-active enzymes and secondary metabolites

Authors: Trine Sørensen, Celine Petersen, Asmus T. Muurmann, Johan V. Christiansen, Mathias L. Brundtø, Christina K. Overgaard, Anders T. Boysen, Rasmus D. Wollenberg, Thomas O. Larsen, Jens L. Sørensen, Kåre L. Nielsen and Teis E. Sondergaard

Quantitative integrative taxonomy informs species delimitation in Teloschistaceae (lichenized Ascomycota ): the genus Wetmoreana as a case study

Authors: Karina Wilk and Robert Lücking

New insights into the stipitate hydnoid fungi Sarcodon , Hydnellum , and the formerly informally defined Neosarcodon , with emphasis on the edible species marketed in Southwest China

Authors: Di Wang, Hui Feng, Jie Zhou, Tian-Hai Liu, Zhi-Yuan Zhang, Ying-Yin Xu, Jie Tang, Wei-Hong Peng and Xiao-Lan He

Singleton-based species names and fungal rarity: Does the number really matter?

Authors: Jonathan Cazabonne, Allison K. Walker, Jonathan Lesven and Danny Haelewaters

H3K4 methylation regulates development, DNA repair, and virulence in Mucorales

Authors: Macario Osorio-Concepción, Carlos Lax, Damaris Lorenzo-Gutiérrez, José Tomás Cánovas-Márquez, Ghizlane Tahiri, Eusebio Navarro, Ulrike Binder, Francisco Esteban Nicolás and Victoriano Garre

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

Unambiguous identification of fungi: where do we stand and how accurate and precise is fungal DNA barcoding?

Authors: Robert Lücking, M. Catherine Aime, Barbara Robbertse, Andrew N. Miller, Hiran A. Ariyawansa, Takayuki Aoki, Gianluigi Cardinali, Pedro W. Crous, Irina S. Druzhinina, David M. Geiser, David L. Hawksworth, Kevin D. Hyde, Laszlo Irinyi, Rajesh Jeewon, Peter R. Johnston, Paul M. Kirk…

Setting scientific names at all taxonomic ranks in italics facilitates their quick recognition in scientific papers

Authors: Marco Thines, Takayuki Aoki, Pedro W. Crous, Kevin D. Hyde, Robert Lücking, Elaine Malosso, Tom W. May, Andrew N. Miller, Scott A. Redhead, Andrey M. Yurkov and David L. Hawksworth

Identification, prevalence and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose of Capsicum annuum in Asia

Authors: Dilani D. de Silva, Johannes Z. Groenewald, Pedro W. Crous, Peter K. Ades, Andi Nasruddin, Orarat Mongkolporn and Paul W. J. Taylor

How to publish a new fungal species, or name, version 3.0

Authors: M. Catherine Aime, Andrew N. Miller, Takayuki Aoki, Konstanze Bensch, Lei Cai, Pedro W. Crous, David L. Hawksworth, Kevin D. Hyde, Paul M. Kirk, Robert Lücking, Tom W. May, Elaine Malosso, Scott A. Redhead, Amy Y. Rossman, Marc Stadler, Marco Thines…

Funga and fungarium

Authors: David L. Hawksworth

Most accessed articles RSS

Mycology research on the front line of environmental and health challenges

Mycology crucially contributes to the understanding of the raising threat that fungi present for humans, plants and animals, as well as their role in ecology and environment diversity. David Hawksworth, Editor-in-Chief, and Wieland Meyer, President of the International Mycological Association, tell us more in interview blog .

Dark fungi: discovery and recognition of unseen fungal diversity

This topical collection, compiled by Robert Lücking and David Hawksworth, flags papers that in some way relate to dark fungi taxonomy and nomenclature, including methodological approaches, nomenclature, and associated topics such as important resources, the extent of unknown fungal diversity, or aspects of species concepts in lineages only known from sequence data.

Mycology at Springer Nature

At Springer Nature, we are committed to raising the quality of academic research across Microbiology. We've now created a new page, highlighting our mycology journals and mycology content.

Aims and scope

IMA Fungus , founded in 2010, is the flagship journal of the International Mycological Association (IMA). The IMA represents the interests of mycology and mycologists worldwide, through a series of regional and national organizations, and is responsible for the now four-yearly International Mycological Congresses (IMCs). The journal considers contributions from all areas of mycology expected to be of interest to the wider mycological community, from basic research to applications. It also includes editorials, news, correspondence, reports of mycological meetings, information on awards and mycologists, and book reviews. IMA Fungus is mandated as the journal in which formal proposals relating to the rules on the naming of fungi or protected lists of names are to be published.

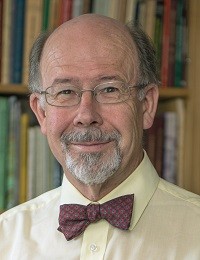

Editor-in-Chief

David Hawksworth

David has wide interests in the systematics, diversity, and ecology of fungi, especially ascomycetes (including lichen fungi), but also their overall classification and improvements in nomenclatural systems. Amongst other things, he pioneered the use of lichens as bioindication or air pollutants, showed what a rich source lichens were for associated fungi, demonstrated how species-rich a single site could be for fungi by field-work over several decades, and established the use of fungi in forensic investigations. He was involved in preparing three editions of the Dictionary of the Fungi, and is well-known as an editor of scientific journals and texts . David was the last Director of the International Mycological Institute, and now holds honorary research positions at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, and The Natural History Museum London.

Senior Editors

Paola Bonfante

Paola has spent much of her scientific career studying the intimate interactions between fungi and plants, also between bacteria and fungi, using cellular and molecular approaches. She first described how plant cells accommodate mycorrhizal fungi following penetration, and by applying DNA technologies, has enhanced our knowledge of mycorrhizal diversity in nature and in cultivated soils, and discovered endobacteria inside mycorrhizal fungi which may modulate traits of their fungal hosts. She contributes to international projects focused to the genome sequencing of diverse mycorrhizal fungi, and is renowned for her expertise on cellular and molecular biology of plant/fungal interactions and the dynamics of fungal populations. Many of her PhD students are now active in researching related fields, and she is currently Professor Emerita of Plant Biology in the University of Turin in Italy.

Matthew Fisher

Matthew researches emerging pathogenic fungi, using an evolutionary framework to investigate the factors driving emerging fungal diseases across human, wildlife, and plant species. Wildlife and their environments play a key role in emerging human infectious disease (EID) by providing a 'zoonotic pool' from which previously unknown pathogens emerge. Human action also impacts on patterns of fungal disease via the perturbation of natural systems, the introduction of pathogenic fungi into new environments, and rapid natural selection for phenotypes – including ones resistant to antimicrobial drugs. Matthew heads a research group at the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, St Mary's Hospital, Imperial College London, focused on developing genomic, epidemiological and experimental models to uncover the factors driving these EIDs, and to attempt to develop new methods of diagnosis and control.

Robert Lücking

Robert’s research focuses on the biodiversity, evolution, ecology, biogeography, systematics, and uses of lichenized and other fungi, in particular tropical lineages, including molecular phylogenetic and genomic approaches. He has a special interest in the discovery of novel fungal lineages known only from environmental sequence data, and pioneered the use of foliicolous communities as indicators of habitat disturbance in the tropics. Robert has extensive field experience in Central and South America, is on the Fulbright Specialist Roster, and a member of the IUCN Lichen Specialist Group. He was formerly based at the Field Museum, Chicago, but in 2015 was appointed Curator (Kustos) for Lichens, Fungi and Bryophytes at the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum (BGBM) of the Freie Universität in Berlin, Germany.

Wieland Meyer

Wieland’s research focuses on the evolution, phylogeny, speciation, population genetics, genomics, molecular epidemiology, genotyping, and molecular identification of human pathogenic fungi, and the understanding of fungal pathogenesis on a molecular level. He is leading an international research team investigating the global epidemiology of the Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex, and an international consortium of microbiology reference laboratories establishing a quality controlled fungal DNA barcode database as a basis for precision-based diagnosis and personalized medicine. In July 2023, he was appointed as the new director of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, an institute of the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Marcio L. Rodrigues

Marcio L. Rodrigues has been working on fungal physiology and cell biology for the last few years. His primary interest is fungal secretion, especially extracellular vesicles. He is also interested in discussing international collaboration mechanisms, reasonable policies for publication charges, raising funds for neglected diseases and using scientific metrics as a tool for decision making.

Brenda Wingfield

Brenda’s research has focussed on the global movement and evolution of fungal pathogens, particularly those on trees. She has been responsible for several major advances in fungal taxonomy and phylogeny, including the introduction of DNA-based research tools in South Africa. Her research group is one of the foremost in the study of distribution and population dynamics of tree pathogens using DNA markers. In addition, she pioneered fungal genomics in southern Africa and was responsible for the first fungal genome sequencing in Africa. Brenda is one of the founding members of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute of the University of Pretoria, now a key world centre for investigations into tree diseases worldwide, and where she holds the DST-NRF SARChI research professorship in fungal genomics.

- Editorial Board

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

IMA Fungus is the official journal of the International Mycological Association .

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 5.4 - 2-year Impact Factor 5.6 - 5-year Impact Factor 2.067 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 1.616 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 17 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 194 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 411,171 downloads 375 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

ISSN: 2210-6359

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Topical and device-based treatments for fungal infections of the toenails

Affiliations.

- 1 Mediprobe Research Inc., 645 Windermere Road, London, ON, Canada, N5X 2P1.

- 2 Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Department of Public Health, 111 Ren'ai Road, Dushu Lake Higher Education Town, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China.

- 3 Campbell Collaboration, New Delhi, India.

- PMID: 31978269

- PMCID: PMC6984586

- DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012093.pub2

Background: Onychomycosis refers to fungal infections of the nail apparatus that may cause pain, discomfort, and disfigurement. This is an update of a Cochrane Review published in 2007; a substantial amount of new research warrants a review exclusively on toenails.

Objectives: To assess the clinical and mycological effects of topical drugs and device-based therapies for toenail onychomycosis.

Search methods: We searched the following databases up to May 2019: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and LILACS. We also searched five trials registers, and checked the reference lists of included and excluded studies for further references to relevant randomised controlled trials.

Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials of topical and device-based therapies for onychomycosis in participants with toenail onychomycosis, confirmed by positive cultures, direct microscopy, or histological nail examination. Eligible comparators were placebo, vehicle, no treatment, or an active topical or device-based treatment.

Data collection and analysis: We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Primary outcomes were complete cure rate (normal-looking nail plus fungus elimination, determined with laboratory methods) and number of participants reporting treatment-related adverse events.

Main results: We included 56 studies (12,501 participants, average age: 27 to 68 years), with mainly mild-to-moderate onychomycosis without matrix involvement (where reported). Participants had more than one toenail affected. Most studies lasted 48 to 52 weeks; 23% reported disease duration (variable). Thirty-five studies specifically examined dermatophyte-caused onychomycosis. Forty-three studies were carried out in outpatient settings. Most studies assessed topical treatments, 9% devices, and 11% both. We rated three studies at low risk of bias across all domains. The most common high-risk domain was performance bias. We present results for key comparisons, where treatment duration was 36 or 48 weeks, and clinical outcomes were measured at 40 to 52 weeks. Based on two studies (460 participants), compared with vehicle, ciclopirox 8% lacquer may be more effective in achieving complete cure (risk ratio (RR) 9.29, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.72 to 50.14; low-quality evidence) and is probably more effective in achieving mycological cure (RR 3.15, 95% CI 1.93 to 5.12; moderate-quality evidence). Ciclopirox lacquer may lead to increased adverse events, commonly application reactions, rashes, and nail alteration (e.g. colour, shape). However, the 95% CI indicates that ciclopirox lacquer may actually make little or no difference (RR 1.61, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.92; low-quality evidence). Efinaconazole 10% solution is more effective than vehicle in achieving complete cure (RR 3.54, 95% CI 2.24 to 5.60; 3 studies, 1716 participants) and clinical cure (RR 3.07, 95% CI 2.08 to 4.53; 2 studies, 1655 participants) (both high-quality evidence) and is probably more effective in achieving mycological cure (RR 2.31, 95% CI 1.08 to 4.94; 3 studies, 1716 participants; moderate-quality evidence). Risk of adverse events (such as dermatitis and vesicles) was slightly higher with efinaconazole (RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.20; 3 studies, 1701 participants; high-quality evidence). No other key comparison measured clinical cure. Based on two studies, compared with vehicle, tavaborole 5% solution is probably more effective in achieving complete cure (RR 7.40, 95% CI 2.71 to 20.24; 1198 participants), but probably has a higher risk of adverse events (application site reactions were most commonly reported) (RR 3.82, 95% CI 1.65 to 8.85; 1186 participants (both moderate-quality evidence)). Tavaborole improves mycological cure (RR 3.40, 95% CI 2.34 to 4.93; 1198 participants; high-quality evidence). Moderate-quality evidence from two studies (490 participants) indicates that P-3051 (ciclopirox 8% hydrolacquer) is probably more effective than the comparators ciclopirox 8% lacquer or amorolfine 5% in achieving complete cure (RR 2.43, 95% CI 1.32 to 4.48), but there is probably little or no difference between the treatments in achieving mycological cure (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.37). We found no difference in the risk of adverse events (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.92; 2 studies, 487 participants; low-quality evidence). The most common events were erythema, rash, and burning. Three studies (112 participants) compared 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser to no treatment or sham treatment. We are uncertain if there is a difference in adverse events (very low-quality evidence) (two studies; 85 participants). There may be little or no difference in mycological cure at 52 weeks (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.85; 2 studies, 85 participants; low-quality evidence). Complete cure was not measured. One study (293 participants) compared luliconazole 5% solution to vehicle. We are uncertain whether luliconazole leads to higher rates of complete cure (very low-quality evidence). Low-quality evidence indicates there may be little or no difference in adverse events (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.16) and there may be increased mycological cure with luliconazole; however, the 95% CI indicates that luliconazole may make little or no difference to mycological cure (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.97). Commonly-reported adverse events were dry skin, paronychia, eczema, and hyperkeratosis, which improved or resolved post-treatment.

Authors' conclusions: Assessing complete cure, high-quality evidence supports the effectiveness of efinaconazole, moderate-quality evidence supports P-3051 (ciclopirox 8% hydrolacquer) and tavaborole, and low-quality evidence supports ciclopirox 8% lacquer. We are uncertain whether luliconazole 5% solution leads to complete cure (very low-quality evidence); this outcome was not measured by the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser comparison. Although evidence supports topical treatments, complete cure rates with topical treatments are relatively low. We are uncertain if 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser increases adverse events compared with no treatment or sham treatment (very low-quality evidence). Low-quality evidence indicates that there is no difference in adverse events between P-3051 (ciclopirox hydrolacquer), luliconazole 5% solution, and their comparators. Ciclopirox 8% lacquer may increase adverse events (low-quality evidence). High- to moderate-quality evidence suggests increased adverse events with efinaconazole 10% solution or tavaborole 5% solution. We downgraded evidence for heterogeneity, lack of blinding, and small sample sizes. There is uncertainty about the effectiveness of device-based treatments, which were under-represented; 80% of studies assessed topical treatments, but we were unable to evaluate all of the currently relevant topical treatments. Future studies of topical and device-based therapies should be blinded, with patient-centred outcomes and an adequate sample size. They should specify the causative organism and directly compare treatments.

Copyright © 2020 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Publication types

- Meta-Analysis

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Systematic Review

- Administration, Topical

- Antifungal Agents / administration & dosage

- Antifungal Agents / therapeutic use*

- Middle Aged

- Onychomycosis / drug therapy*

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

- Treatment Outcome

- Antifungal Agents

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 02 May 2023

Address the growing urgency of fungal disease in crops

- Eva Stukenbrock 0 &

- Sarah Gurr 1

Eva Stukenbrock is a professor and head of the Environmental Genomics group at Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel, Germany, and fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR).

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Sarah Gurr is a professor and the chair in Food Security at the University of Exeter, UK, a visiting professor at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands, and a fellow of the CIFAR.

Clouds of dust caused by a fungus engulf a crop field. Credit: Darren Hauck/Reuters

In October 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) published its first list of fungal pathogens that infect humans, and warned that certain increasingly abundant disease-causing fungal strains have acquired resistance to known antifungals 1 . Even though more than 1.5 million people die each year from fungal diseases, the WHO’s list is the first global effort to systematically prioritize surveillance, research and development, and public-health interventions for fungal pathogens.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 617 , 31-34 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01465-4

Fisher, M. C. & Denning, D. W. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 21 , 211–212 (2023).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Steinberg, G. & Gurr, S. J. Fungal Genet. Biol. 144 , 103476 (2020).

Fisher, M. C. et al. Nature 484 , 186–194 (2012).

Bebber, D. P., Ramotowski, M. A. T. & Gurr, S. J. Nature Clim. Change 3 , 985–988 (2013).

Article Google Scholar

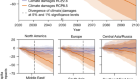

Chaloner, T. M., Gurr, S. J. & Bebber, D. P. Nature Clim. Change 11 , 710–715 (2021).

Savary, S. et al. Nature Ecol. Evol. 3 , 430–439 (2019).

Fones, H. & Gurr, S. Fungal Genet. Biol. 79 , 3–7 (2015).

Brown, J. K. M. & Hovmøller, M. S. Science 297 , 537–541 (2002).

Möller, M. & Stukenbrock, E. H. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 15 , 756–771 (2017).

Oliver, R. P. & Hewitt, H. G. Fungicides in Crop Protection (CABI, 2014).

Google Scholar

Karasov, T. L., Chae, E., Herman, J. J. & Bergelson, J. Plant Cell 29 , 666–680 (2017).

Mesny, F. et al. Nature Commun. 12 , 7227 (2021).

Garcia-Solache, M. A. & Casadevall, A. mBio 1 , e00061-10 (2010).

Steinberg, G. et al. Nature Commun. 11 , 1608 (2020).

Cannon, S. et al. PLoS Pathog. 18 , e1010860 (2022).

Orellana-Torrejon, C., Vidal, T., Saint-Jean, S. & Suffert, F. Plant Pathol . 71 , 1537–1549 (2022).

Balesdent, M.-H. et al. Phytopathology 112 , 2126–2137 (2022).

Lahlali, R. et al. Microorganisms 10 , 596 (2022).

Weiberg, A. et al. Science 342 , 118–123 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. Nature Plants 2 , 16151 (2016).

Wang, M. & Jin, H. Trends Microbiol. 25 , 4–6 (2017).

Niu, D. et al. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 70 , 204–212 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Climate change

- Plant sciences

Nearly half of China’s major cities are sinking — some ‘rapidly’

News 18 APR 24

The economic commitment of climate change

Article 17 APR 24

Use game theory for climate models that really help reach net zero goals

Correspondence 16 APR 24

Deadly diseases and inflatable suits: how I found my niche in virology research

Spotlight 17 APR 24

Obesity drugs aren’t always forever. What happens when you quit?

News Feature 16 APR 24

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

News Feature 10 APR 24

The complex polyploid genome architecture of sugarcane

Article 27 MAR 24

The ‘Mother Tree’ idea is everywhere — but how much of it is real?

News Feature 26 MAR 24

Estella Bergere Leopold (1927–2024), passionate environmentalist who traced changing ecosystems

Obituary 26 MAR 24

Head of Biology, Bio-island

Head of Biology to lead the discovery biology group.

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

BeiGene Ltd.

Research Postdoctoral Fellow - MD (Cardiac Surgery)

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Director of Mass Spectrometry

Loyola University Chicago, Stritch School of Medicine (SSOM) seeks applicants for a full-time Director of Mass Spectrometry.

Chicago, Illinois

Loyola University of Chicago - Cell and Molecular Physiology Department

Associate or Senior Editor, Nature Biomedical Engineering

Associate Editor or Senior Editor, Nature Biomedical Engineering Location: London, Shanghai and Madrid — Hybrid office and remote working Deadline:...

London (Central), London (Greater) (GB)

Springer Nature Ltd

FACULTY POSITION IN PATHOLOGY RESEARCH

Dallas, Texas (US)

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern Medical Center)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Biostatistics Graduate Program

Yeji ko is first author of annals of epidemiology paper.

Posted by duthip1 on Thursday, April 18, 2024 in News .

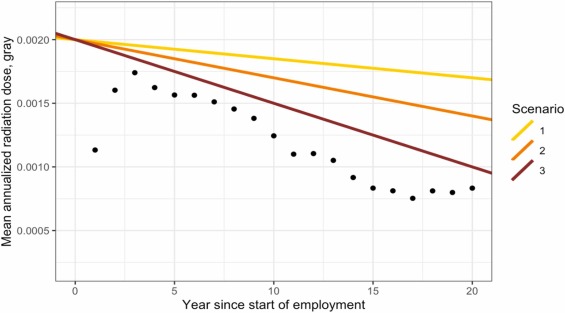

Congratulations to PhD student Yeji Ko on the publication of Adjustment for duration of employment in occupational epidemiology in the June 2024 issue of Annals of Epidemiology (appearing online ahead of print this week). Professor Ben French , who was r ecently elected to the National Council for Radiation Protection and Measurements , is the paper’s corresponding author. Ko, French, and colleagues at Oak Ridge Associated Universities examined the healthy worker survivor effect in relation to radiation risk among nuclear workers, using simulation studies to arrive at reliable results and conclude that “it is crucial to flexibly adjust for duration of employment to account for confounding arising from the healthy worker survivor effect in occupational epidemiology.” The work was made possible by the Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) Directed Research and Development Grant, which promotes collaborations between universities and ORAU scientists for foundational research efforts.

Tags: publications

Leave a Response

You must be logged in to post a comment

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

“Keep Cool—Process Promptly”

How a bit of exceedingly clever packaging explains a subculture..

This piece was originally published by the MIT Press Reader and has been republished here with permission.

The image that follows is not of actual Kodak film but rather of a clever and gently satiric stealth packaging for underground LSD made by the New Yorker Eric Ghost—aka Eric Brown—in 1968. Ghost first took LSD in the Lower East Side around 1965, after a peripatetic life of military service, armed robbery, and prison. He swallowed nearly 4,000 micrograms, or mics, of pure Sandoz smeared across a sugar cube, and the thermonuclear revelation occasioned by this enormous dose convinced him to co-found the Psychedelicatessen, a legendary though short-lived head shop that opened on 164 Avenue A in 1966. Like many acid people at the time, Ghost was messianic about the molecule and its potential to improve people and the world. Once LSD was banned, he decided to start cooking and distributing the material himself.

In contrast to today, when psychedelics are imagined to be medicines, party favors, or Indigenous sacraments, many LSD users in the 1960s imagined their favorite substance as a kind of media. Like the increasingly technological media of the postwar world, LSD filters, transforms, and amplifies non-drug phenomena. Ghost played with this association by disguising his acid as film stock promising “brilliant color.” Each sheet was wrapped inside Mylar, which not only protected the acid from damaging UV light but also discouraged suspicious parties from opening the package on a whim, potentially destroying unexposed film. This “medium is the message” idea permeated acid discourse and marketing. Other examples include “Window pane,” “Clearlist,” and some of the first printed LSD blotters, which featured electric lightbulbs.

Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium

By Erik Davis. MIT Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Ghost’s stealth packaging contained a novel and significant development in LSD distribution: the first mechanically produced examples of blotter paper dosed with drops of LSD. Liquid LSD had been placed on actual blotting paper and other paper products before, but these transfers would occur one drop at a time, using a pipette or eyedropper. Ghost and a colleague accelerated this process by designing and building the Mark I, a device that allowed 100 pins to be dipped simultaneously into a pan of LSD in solution, and then moved as a single unit and impressed simultaneously onto a single absorbent piece of paper. The pins, and the dosed paper that resulted, followed a compact grid, which took the form of five tight rows of 20 columns each—the “5-20” pattern slyly referred to above. Each one of Ghost’s drops contained a hefty 1,000 mics of LSD, which were left to the distributor or client to manually cut into four smaller hits, each packing a still-solid 250-mic punch. This arrangement—the “four-way”—would recur throughout the history of blotter.

Opening Ghost’s package, purchasers would discover a handy information sheet that today gives us a sense of how some underground purveyors understood and promoted their wares. Rather than hippie mysticism or revolutionary cant, Ghost’s text presents LSD as a scientific product of a modern research lab run by a pharmaceutical corporation. Though LSD was related to an organic material—the ergot fungus on rye—part of the drug’s curious profile emerged from its origins at the heart of European technological modernity. Though some of Ghost’s information is off (LSD is not chemically similar to mescaline), it demonstrates the nerdy fascination that was always part of modern psychedelic culture.

The most dominant and consistent idea in postwar psychedelic culture and research, still widely used today, is the role of “set and setting” in influencing the experience. Though trumpeted by Timothy Leary and his co-authors in the 1964 book The Psychedelic Experience , the notion that LSD reflects and amplifies internal attitudes and environment cues had been recognized by researchers and users in the 1950s. This recursive effect helps explain the wide variety and plasticity of psychedelic effects, as well as the importance of the cultural stories that surround these compounds—expanded consciousness in the 1960s; cluster headaches and PTSD today. Even in those hedonistic and experimental eras, though, the important role of the guide was recognized.

Today’s clinical and therapeutic promoters of the “psychedelic renaissance” often present themselves as novel pioneers. Ghost’s text reminds us that the 1960s research community had already explored many clinical applications of LSD—for alcoholism, pain and anxiety among cancer patients, psychological repression, and even the challenges of autism. At the same time, the mention of LSD as a possible “cure” for homosexuality—something that was explored earlier in the 1960s by Leary and Richard Alpert, who later embraced his gay identity—reminds us of the distortion inherent in such research agendas, as well as LSD’s darker legacy as an agent of behavioral modification.

April 17, 2024

A Dengue Fever Outbreak Is Setting Records in the Americas

At least 2.1 million cases of dengue fever have been reported in North and South America, and this year 1,800 people have died from the mosquito-borne disease

By Francisco "A.J." Camacho & E&E News

A worker fumigates a house against the Aedes aegypti mosquito to prevent the spread of dengue fever in a neighborhood in Piura, northern Peru.

Ernesto Benavides/AFP via Getty Images

CLIMATEWIRE | At least 2.1 million people in North and South America have been infected this year with dengue — a record-setting figure that scientists attribute in part to climate change.

The Pan American Health Organization says there have been about 2.1 million confirmed cases of the potentially fatal disease in the Americas since January. That’s already more than the record-setting mark of 2 million confirmed cases for all of 2023.

And this year’s figure could be much higher. As many as 5.1 million people may have been infected in North and South America, according to the Pan American Health Organization, the United Nations agency in charge of international health cooperation in the Americas.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The outbreak has pushed Puerto Rico, Peru and nine of Brazil’s 26 states to declare states of emergency. More than 1,800 people in the Americas have died this year from dengue.

“We already have a large number of cases this year, not only in Brazil but also Paraguay and Argentina and other countries — even Uruguay and areas where there has been no transmission of dengue for a century,” said Pan American Health Organization director Jarbas Barbosa in a March press briefing.

Dengue typically causes short-term symptoms such as rashes and joint pain but the disease can be life-threatening in severe cases.

Mosquito bites spread the disease to humans, and public health experts say that warmer winters that don’t kill enough mosquitoes are one cause contributing to dengue outbreaks.

A compounding factor this year has been El Niño, a natural, temporary, and occasional warming of part of the Pacific that generates higher precipitation in much of the Americas.

Those elements — higher temperatures and more rain — are foundational for dengue outbreaks because they create the perfect breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

Barbosa, in his March briefing, cited a “combination of climate change and El Niño” as key factors of this year’s outbreak.

The number of dengue cases in North and South America has exploded over the past several decades. Dengue cases in the Americas are roughly five times higher in the 2020s than in the late 1990s.

A March study published in the journal Nature found that mosquito reproduction speed is “strongly influenced” by temperature and rainfall because mosquitoes die off in colder weather and precipitation makes puddles for mosquitoes to lay eggs.

“Every heat wave is a push that builds up dengue transmission,” said Christovam Barcellos, co-author of the Nature paper and senior researcher at Brazil-based Fiocruz research foundation. “There are more heat wave incidents in central Brazil, and that is the zone most affected by dengue now.”

Barcellos said heat waves mean not only more mosquitoes: “People change their behavior when a heat wave comes, they go out on the streets more” which increases their exposure to disease-carrying insects.

“It’s a complementary phenomenon,” he said.

While the United States often sees thousands of dengue cases annually, only about 6 percent are locally acquired while most are picked up during travel, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But this year, health experts worry dengue could hit the lower 48 hard.

“If a series of heat waves also come to the U.S., it can augment transmission,” Barcellos said.

Kacey Ernst, chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Arizona, shares Barcellos’ concern.

“We have had sporadic cases of locally acquired dengue in Florida and Texas for years now, and Arizona saw its first locally acquired case in 2022, so the potential is there,” Ernst said.

“I don’t often use words like explosion of transmission,” Ernst said. “But it seems to be an accurate description of dengue transmission this year.”

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2024. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.

Paper: To understand cognition—and its dysfunction—neuroscientists must learn its rhythms

Thought emerges and is controlled in the brain via the rhythmically and spatially coordinated activity of millions of neurons, scientists argue in a new article. Understanding cognition and its disorders requires studying it at that level.

It could be very informative to observe the pixels on your phone under a microscope, but not if your goal is to understand what a whole video on the screen shows. Cognition is much the same kind of emergent property in the brain . It can only be understood by observing how millions of cells act in coordination, argues a trio of MIT neuroscientists. In a new article , they lay out a framework for understanding how thought arises from the coordination of neural activity driven by oscillating electric fields—also known as brain “waves” or “rhythms.”

Historically dismissed solely as byproducts of neural activity, brain rhythms are actually critical for organizing it, write Picower Professor Earl Miller and research scientists Scott Brincat and Jefferson Roy in Current Opinion in Behavioral Science . And while neuroscientists have gained tremendous knowledge from studying how individual brain cells connect and how and when they emit “spikes” to send impulses through specific circuits, there is also a need to appreciate and apply new concepts at the brain rhythm scale, which can span individual, or even multiple, brain regions.

“Spiking and anatomy are important but there is more going on in the brain above and beyond that,” said senior author Miller, a faculty member in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. “There’s a whole lot of functionality taking place at a higher level, especially cognition.”

The stakes of studying the brain at that scale, the authors write, might not only include understanding healthy higher-level function but also how those functions become disrupted in disease.

“Many neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, epilepsy and Parkinson’s involve disruption of emergent properties like neural synchrony,” they write. “We anticipate that understanding how to interpret and interface with these emergent properties will be critical for developing effective treatments as well as understanding cognition.”

The emergence of thoughts

The bridge between the scale of individual neurons and the broader-scale coordination of many cells is founded on electric fields, the researchers write. Via a phenomenon called “ephaptic coupling,” the electrical field generated by the activity of a neuron can influence the voltage of neighboring neurons, creating an alignment among them. In this way, electric fields both reflect neural activity but also influence it. In a paper in 2022 , Miller and colleagues showed via experiments and computational modeling that the information encoded in the electric fields generated by ensembles of neurons can be read out more reliably than the information encoded by the spikes of individual cells. In 2023 Miller’s lab provided evidence that rhythmic electrical fields may coordinate memories between regions.

At this larger scale, in which rhythmic electric fields carry information between brain regions, Miller’s lab has published numerous studies showing that lower-frequency rhythms in the so-called “beta” band originate in deeper layers of the brain’s cortex and appear to regulate the power of faster-frequency “gamma” rhythms in more superficial layers. By recording neural activity in the brains of animals engaged in working memory games the lab has shown that beta rhythms carry “top down” signals to control when and where gamma rhythms can encode sensory information, such as the images that the animals need to remember in the game.

Some of the lab’s latest evidence suggests that beta rhythms apply this control of cognitive processes to physical patches of the cortex, essentially acting like stencils that pattern where and when gamma can encode sensory information into memory, or retrieve it. According to this theory, which Miller calls “ Spatial Computing ,” beta can thereby establish the general rules of a task (for instance, the back and forth turns required to open a combination lock), even as the specific information content may change (for instance, new numbers when the combination changes). More generally, this structure also enables neurons to flexibly encode more than one kind of information at a time, the authors write, a widely observed neural property called “mixed selectivity.” For instance, a neuron encoding a number of the lock combination can also be assigned, based on which beta-stenciled patch it is in, the particular step of the unlocking process that the number matters for.

In the new study Miller, Brincat and Roy suggest another advantage consistent with cognitive control being based on an interplay of large-scale coordinated rhythmic activity: “Subspace coding.” This idea postulates that brain rhythms organize the otherwise massive number of possible outcomes that could result from, say, 1,000 neurons engaging in independent spiking activity. Instead of all the many combinatorial possibilities, many fewer “subspaces” of activity actually arise, because neurons are coordinated, rather than independent. It is as if the spiking of neurons is like a flock of birds coordinating their movements. Different phases and frequencies of brain rhythms provide this coordination, aligned to amplify each other, or offset to prevent interference. For instance, if a piece of sensory information needs to be remembered, neural activity representing it can be protected from interference when new sensory information is perceived.

“Thus the organization of neural responses into subspaces can both segregate and integrate information,” the authors write.

The power of brain rhythms to coordinate and organize information processing in the brain is what enables functional cognition to emerge at that scale, the authors write. Understanding cognition in the brain, therefore, requires studying rhythms.

“Studying individual neural components in isolation—individual neurons and synapses—has made enormous contributions to our understanding of the brain and remains important,” the authors conclude. “However, it’s becoming increasingly clear that, to fully capture the brain’s complexity, those components must be analyzed in concert to identify, study, and relate their emergent properties.”

Related Articles

Study reveals a universal pattern of brain wave frequencies.

Anesthesia blocks sensation by cutting off communication within the cortex

Anesthesia technology precisely controls unconsciousness in animal tests

A multifunctional tool for cognitive neuroscience

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computation and Language

Title: leave no context behind: efficient infinite context transformers with infini-attention.

Abstract: This work introduces an efficient method to scale Transformer-based Large Language Models (LLMs) to infinitely long inputs with bounded memory and computation. A key component in our proposed approach is a new attention technique dubbed Infini-attention. The Infini-attention incorporates a compressive memory into the vanilla attention mechanism and builds in both masked local attention and long-term linear attention mechanisms in a single Transformer block. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach on long-context language modeling benchmarks, 1M sequence length passkey context block retrieval and 500K length book summarization tasks with 1B and 8B LLMs. Our approach introduces minimal bounded memory parameters and enables fast streaming inference for LLMs.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

About 1 in 4 U.S. teachers say their school went into a gun-related lockdown in the last school year

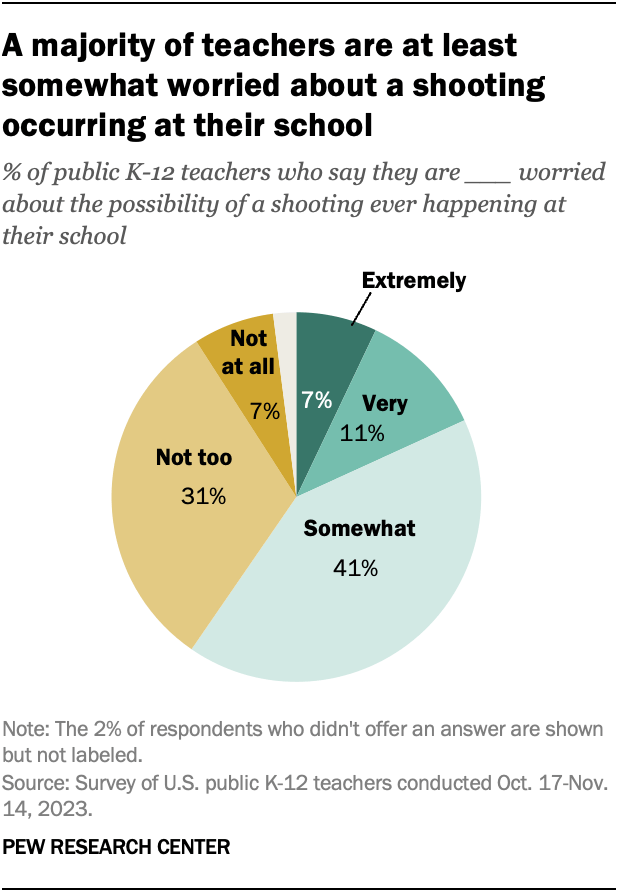

Twenty-five years after the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado , a majority of public K-12 teachers (59%) say they are at least somewhat worried about the possibility of a shooting ever happening at their school. This includes 18% who say they’re extremely or very worried, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to better understand public K-12 teachers’ views on school shootings, how prepared they feel for a potential active shooter, and how they feel about policies that could help prevent future shootings.

To do this, we surveyed 2,531 U.S. public K-12 teachers from Oct. 17 to Nov. 14, 2023. The teachers are members of RAND’s American Teacher Panel, a nationally representative panel of public school K-12 teachers recruited through MDR Education. Survey data is weighted to state and national teacher characteristics to account for differences in sampling and response to ensure they are representative of the target population.

We also used data from our 2022 survey of U.S. parents. For that project, we surveyed 3,757 U.S. parents with at least one child younger than 18 from Sept. 20 to Oct. 2, 2022. Find more details about the survey of parents here .

Here are the questions used for this analysis , along with responses, and the survey methodology .

Another 31% of teachers say they are not too worried about a shooting occurring at their school. Only 7% of teachers say they are not at all worried.

This survey comes at a time when school shootings are at a record high (82 in 2023) and gun safety continues to be a topic in 2024 election campaigns .

Teachers’ experiences with lockdowns

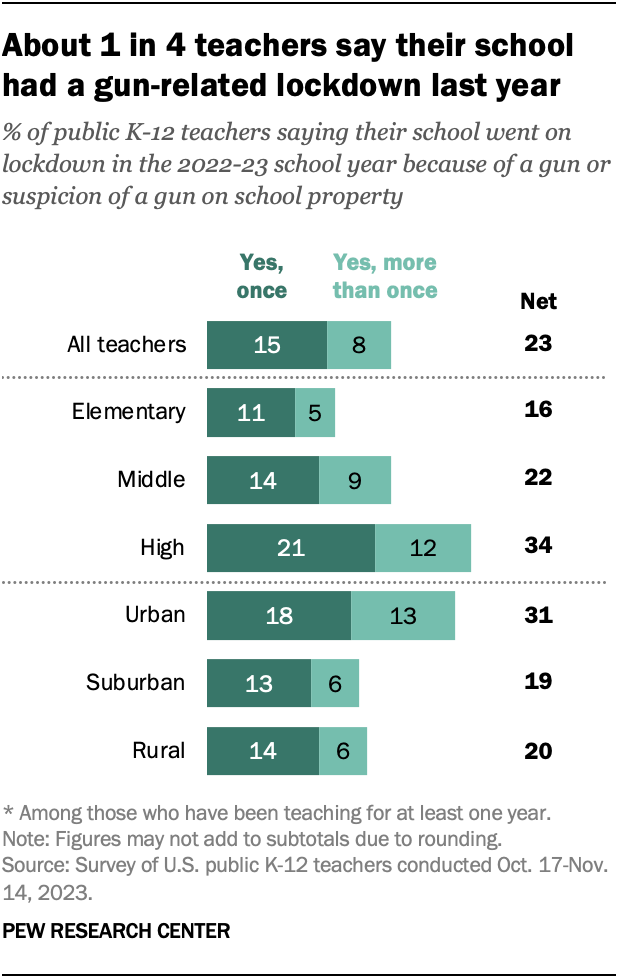

About a quarter of teachers (23%) say they experienced a lockdown in the 2022-23 school year because of a gun or suspicion of a gun at their school. Some 15% say this happened once during the year, and 8% say this happened more than once.

High school teachers are most likely to report experiencing these lockdowns: 34% say their school went on at least one gun-related lockdown in the last school year. This compares with 22% of middle school teachers and 16% of elementary school teachers.

Teachers in urban schools are also more likely to say that their school had a gun-related lockdown. About a third of these teachers (31%) say this, compared with 19% of teachers in suburban schools and 20% in rural schools.

Do teachers feel their school has prepared them for an active shooter?

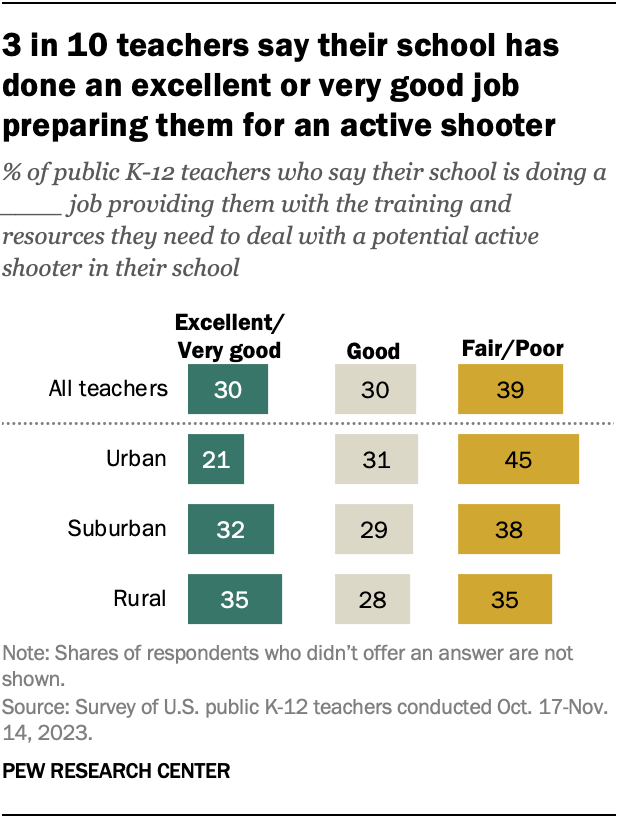

About four-in-ten teachers (39%) say their school has done a fair or poor job providing them with the training and resources they need to deal with a potential active shooter.

A smaller share (30%) give their school an excellent or very good rating, and another 30% say their school has done a good job preparing them.

Teachers in urban schools are the least likely to say their school has done an excellent or very good job preparing them for a potential active shooter. About one-in-five (21%) say this, compared with 32% of teachers in suburban schools and 35% in rural schools.

Teachers who have police officers or armed security stationed in their school are more likely than those who don’t to say their school has done an excellent or very good job preparing them for a potential active shooter (36% vs. 22%).

Overall, 56% of teachers say they have police officers or armed security stationed at their school. Majorities in rural schools (64%) and suburban schools (56%) say this, compared with 48% in urban schools.

Only 3% of teachers say teachers and administrators at their school are allowed to carry guns in school. This is slightly more common in school districts where a majority of voters cast ballots for Donald Trump in 2020 than in school districts where a majority of voters cast ballots for Joe Biden (5% vs. 1%).

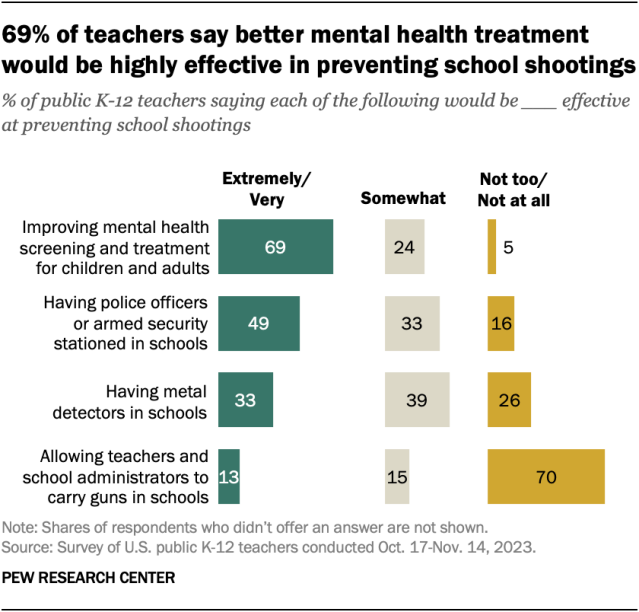

What strategies do teachers think could help prevent school shootings?

The survey also asked teachers how effective some measures would be at preventing school shootings.

Most teachers (69%) say improving mental health screening and treatment for children and adults would be extremely or very effective.

About half (49%) say having police officers or armed security in schools would be highly effective, while 33% say the same about metal detectors in schools.

Just 13% say allowing teachers and school administrators to carry guns in schools would be extremely or very effective at preventing school shootings. Seven-in-ten teachers say this would be not too or not at all effective.

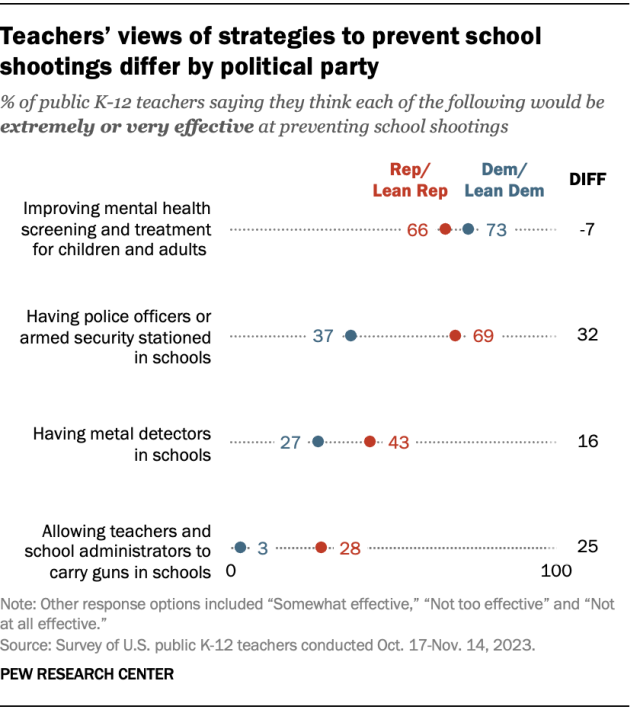

How teachers’ views differ by party

Republican and Republican-leaning teachers are more likely than Democratic and Democratic-leaning teachers to say each of the following would be highly effective:

- Having police officers or armed security in schools (69% vs. 37%)

- Having metal detectors in schools (43% vs. 27%)

- Allowing teachers and school administrators to carry guns in schools (28% vs. 3%)

And while majorities in both parties say improving mental health screening and treatment would be highly effective at preventing school shootings, Democratic teachers are more likely than Republican teachers to say this (73% vs. 66%).

Parents’ views on school shootings and prevention strategies

In fall 2022, we asked parents a similar set of questions about school shootings.

Roughly a third of parents with K-12 students (32%) said they were extremely or very worried about a shooting ever happening at their child’s school. An additional 37% said they were somewhat worried.

As is the case among teachers, improving mental health screening and treatment was the only strategy most parents (63%) said would be extremely or very effective at preventing school shootings. And allowing teachers and school administrators to carry guns in schools was seen as the least effective – in fact, half of parents said this would be not too or not at all effective. This question was asked of all parents with a child younger than 18, regardless of whether they have a child in K-12 schools.

Like teachers, parents’ views on strategies for preventing school shootings differed by party.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis , along with responses, and the survey methodology .

About half of Americans say public K-12 education is going in the wrong direction

What public k-12 teachers want americans to know about teaching, what’s it like to be a teacher in america today, race and lgbtq issues in k-12 schools, from businesses and banks to colleges and churches: americans’ views of u.s. institutions, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Conversation With …

She Dreams of Pink Planets and Alien Dinosaurs

Lisa Kaltenegger, director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, hunts for aliens in space by studying Earth across time.

By Becky Ferreira

Have dinosaurs evolved on other worlds? Could we spot a planet of glowing organisms ? What nearby star systems are positioned to observe Earth passing in front of the sun?

These are just a few of the questions that Lisa Kaltenegger has joyfully tackled. As the founding director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, she has pioneered interdisciplinary work on the origins of life on Earth and the hunt for signs of life, or biosignatures, elsewhere in the universe.

Dr. Kaltenegger’s new book, “Alien Earths: The New Science of Planet Hunting in the Cosmos,” to be published on April 16 , chronicles her insights and adventures spanning an idyllic childhood in Austria to her Cornell office, which previously belonged to the astronomer Carl Sagan. She spoke with The New York Times about the intense public interest in aliens, the wisdom of trying to contact intelligent civilizations, and the weirdest creatures she’s grown in her lab. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You look for real aliens in the observable universe. How much is the diversity of opinion and emotion from people around the search for extraterrestrial life top-of-mind in your research? Or are U.F.O.s and sci-fi E.T.s something you have to tune out?

For me, it’s inspirational that so many people are excited. The other part of that coin is that we are so close, because we have the James Webb Space Telescope now being able to look at these small planets that could potentially be like Earth. We don’t have to go with dubious or hard-to-interpret evidence anymore.

I wrote this book because I think a lot of people might not be so aware of where we are right now, and that they are living in this momentous time in history. We can all be a part of it.

How should people prepare for a potential detection of signs of something living in a distant planet’s atmosphere that’s not like you see in the movies, that’s maybe less satisfying?

If we were to find signs of life — any signs that we can’t explain with anything else but life — then that just means we live in a universe teeming with life, because we’re just at the verge of being able to find it. And it’s so hard, even with the best telescopes, so if we find anything, that means there’s so much more to find out there. I’ll celebrate, whatever it is.

The title “Alien Earths” refers to alien worlds, but also the past and future versions of Earth that are alien to us. What is a moment in Earth’s history that you would want to go to?

The moment and place when life started. Because it is such a mystery. You don’t need the whole planet to have conditions to get life started. It could be a niche somewhere. It could be an asteroid that hit just with the right speed and energy and mixed the chemicals on Earth up the right way. It could have been on an ice shell, or in a shallow pond.

There is an overlap between the pioneers of the search for alien civilization and the development of nuclear weapons. Do you think that kind of complicated heritage has shaped expectations about the longevity of intelligent civilizations?

Absolutely. I think in our search for life is buried the hope that if we find life everywhere, on planets older than us, that we will make it. By definition, to be able to travel the stars fast or with propulsion that can get you very far, that same technology can destroy the world you live on and everyone on it.

The question that always comes, and I think it’s a normal question, is: Will you have the wisdom to use this power for good or evil? That’s usually the story. Will you have the wisdom to survive this capability, and this technology?

There is a heated debate over whether we should be actively trying to contact alien life, or if we should just be passively looking for signs of it. Where do you come down on that question?

I was at a Vatican Observatory conference and I was actually the speaker after Stephen Hawking. Oh my god, right? Amazing. But it’s really interesting because he was one of the people who cautioned very much against this.

We are two billion years too late to worry about it. Anybody who would have looked at us for two billion years would know that there’s life on this planet. Basically, the cat’s out of the bag.

But I think it is a very valid concern in terms of social science or sociology, because we don’t want to do anything to scare people. It is worth asking the question to ourselves, too: Are we at the point, all of us, where we’d actually like to communicate with other civilizations? And what would we want to ask?

What inspired you to create the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell?

I’m an astronomer by training, and I worked on the design of a mission to find signs of life in the universe. We were only looking at carbon copies of modern Earth. But we know that Earth has changed, so if we only look at this tiny part of the history of Earth, compared to its 4.6 billion years, we are going to miss young and future Earths.

To actually answer the question of how our planet works, you need a network of many different departments and many different ways of life. The more diverse background you can get, the more ideas you can get and the more complicated problems you can solve.

You have a lab where you’re growing microbes to inform the search for life. What’s the weirdest thing you’ve grown?

A pink fungus. You have to be very careful about fungi because they spread like crazy. This is why I’m working with microbiologists. One of my team’s microbiologists is like, “I’m not touching this and contaminating all of Cornell with pink fungus.” Imagine that.

So you had to take special precautions to make sure that this alien didn’t invade.

I just imagine a world overgrown with pink fungi.

You have published a stud y that simulated conditions analogous to the age of dinosaurs on other worlds. How can we specifically search for alien dinosaurs? Because I want to find alien dinosaurs.

During the age of the dinosaurs, there was more oxygen and also more methane, and that allowed for these huge creatures. At least that’s the idea , right? More oxygen can actually make creatures bigger, thus huge dinosaurs.

The fun part when I talked about this with my teammate, geologist Rebecca Payne, is that actually it could be much easier to find a dinosaur planet, to find “Jurassic World.”

Now the question is, of course: Does it have to be dinosaurs? They could be really funky different kinds of organisms that don’t look like dinosaurs.

The realities of probability tell me that dinosaurs can probably exist only once and yet my heart will not believe it.

We have 200 billion stars in our galaxy alone, and there are billions of galaxies. We have billions and billions of possibilities.

Let’s say that we are optimists and we say where life could start, it does start. That’s a hypothesis: We have no idea if that’s true. But maybe dinosaurs twice is actually an option.

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

Scientists may have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, a mysterious cosmic force . That could be good news for the fate of the universe.

A new set of computer simulations, which take into account the effects of stars moving past our solar system, has effectively made it harder to predict Earth’s future and reconstruct its past.

Dante Lauretta, the planetary scientist who led the OSIRIS-REx mission to retrieve a handful of space dust , discusses his next final frontier.

A nova named T Coronae Borealis lit up the night about 80 years ago. Astronomers say it’s expected to put on another show in the coming months.

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Fungi (Basel)

Recent Approaches towards Control of Fungal Diseases in Plants: An Updated Review

Associated data.

Data is contained within the article.

Recent research demonstrates that the number of virulent phytopathogenic fungi continually grows, which leads to significant economic losses worldwide. Various procedures are currently available for the rapid detection and control of phytopathogenic fungi. Since 1940, chemical and synthetic fungicides were typically used to control phytopathogenic fungi. However, the substantial increase in development of fungal resistance to these fungicides in addition to negative effects caused by synthetic fungicides on the health of animals, human beings, and the environment results in the exploration of various new approaches and green strategies of fungal control by scientists from all over the world. In this review, the development of new approaches for controlling fungal diseases in plants is discussed. We argue that an effort should be made to bring these recent technologies to the farmer level.

1. Introduction

The vast majority of known fungal species are strict saprophytes; only very few species (less than 10% of identified fungi) can colonize plants. Phytopathogenic fungi represent an even smaller fraction of these plant colonizers. Yet, phytopathogenic fungi are the key causative agent among phytopathogens for devastating crop plant epidemics, besides causing persistent and substantial losses in crop yield annually. Thus, phytopathogenic fungi are battled by scientists, plant breeders, and farmers equally due to these economic factors [ 1 , 2 ].

Commercial agriculture depends mainly on the application of chemical fungicides to protect crop plants against fungal pathogens by destroying and inhibiting their cells and spores. However, their easy application and low cost result in their overuse or repeated applications [ 3 ]. This overuse or misuse of fungicides has led to toxic effects on beneficial living systems, human and animal health, and the environment. Moreover, the emergence of resistant strains of fungal phytopathogens makes plant fungal diseases become increasingly challenging to treat. Accordingly, development of healthy, non-toxic, and eco-friendly alternate approaches (green strategies of fungal control) to chemical and synthetic fungicides is very helpful in the control of plant fungal infections [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. These safe and effective alternative control means against plant fungal diseases include biological control of phytopathogenic fungi [ 7 ], microbial fungicides [ 7 , 8 ], botanical fungicides [ 9 ], agronanotechnology [ 10 , 11 ], and fungal cell deactivation and evacuation using ghost techniques [ 12 ].

In this article, we reviewed biocontrol, biofungicides, microbial fungicides, botanical fungicides, agronanotechnology, and fungal cell deactivation and evacuation using ghost techniques that represent recent, safe, and effective alternative control means (green strategies of fungal control) against plant fungal diseases that have been reported in the scientific literature but have not yet been properly introduced to farmers.

2. Biological Control of Phytopathogenic Fungi

2.1. biofumigation (biological soil disinfection).

This control method is based on fresh organic material incorporation in the soil and then its plastic tarping [ 13 ]. It employs organic material fermentation in soil under plastic cover to produce anaerobic conditions and toxic metabolites leading to inactivation of phytopathogenic fungi. The technique was further developed and classified by Lamers et al. (2004) [ 14 ] to biofumigation using distinctive plant species comprising well-known toxic molecules, and biodisinfection by organic substances that produce anaerobic conditions for inactivation of phytopathogenic fungi.

Plant species of the Alliaceae (onion) family produce toxic molecules that directly or indirectly affect fungal plant pathogens. For example, garlic and onion tissues degradation leads to sulfur volatiles’ (zwiebelanes and thiosulfinates) release, which are then converted into biocidal disulfides against phytopathogenic fungi [ 15 ].

Blok et al. (2000) [ 13 ] reported the control of soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi ( Fusarium oxysporum and Rhizoctonia solani ) by integrating fresh organic matter such as cabbage or ryegrass in soil followed by plastic tarping. These methods represent promising substitutes for banned methyl bromide disinfection, which harms the human respiratory and central nervous.

A recent laboratory and greenhouse study was carried out in Egypt which involved use of biofumigation with Indian mustard ( Brassica juncea ) to control Rhizoctonia solani infection of the common bean. They used Brassica juncea as fresh and dry plants, methanol extract, or seed powder and meal [ 16 ].

2.2. The Use of Antagonistic Microorganisms in Suppressive Soils

Phytopathogenic fungi can be controlled by adding suppressive soil that comprises antagonistic microorganisms (microbes antagonistic to phytopathogenic fungi) to natural pathogen-conducive soil. This added suppressive soil results in fungal pathogen and plant fungal disease suppression [ 17 ]. Various antagonistic microorganisms were identified in suppressive soils, but fungi were the dominant microbes among them that have the ability to suppress pathogens and diseases. For instance, to control papaya root rot caused by Phytophthora palmivora, papaya seedlings were planted in suppressive virgin soil and added to holes in the infected plantation soil [ 7 ]. This control protocol was followed for protecting papaya roots during early stages of growth (seedlings), because papaya roots are susceptible to Phytophthora palmivora only when the plant is young. Virgin soil used was collected soil from land that had never been used for growing papaya, and thus was generally free from Phytophthora palmivora infection, which occurs only in replanting fields. About 42% of papaya seedlings planted in holes in the infected plantation soil without virgin soil died three months after planting, while all of those planted in holes in the infected plantation soil with virgin soil survived. Another example is control of the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum that causes wilt disease using suppressive soils [ 18 ]. Other studies involved analysis of Fusarium wilt suppressive soils from Chateaurenard and identified new bacterial and fungal genera in these soils that play a key role in suppression of Fusarium wilt [ 19 ].

In some cases, only monocultures of the same crop in a pathogen-conducive soil will reduce plant fungal disease after years of severe infection, as antagonistic microflora to the fungal pathogen will increase with passing time [ 20 ]. An example of this is monoculture of cucumber or wheat that reduces infections of cucumber damping-off and wheat take-all, respectively, caused by Rhizoctonia [ 7 ]. Other studies argue that intercropping or the simultaneous cultivation of various species of crops exceeds monocropping in disease control [ 21 , 22 ].

A third example of the use of soil suppressiveness in controlling phytopathogenic fungi is cultivation of proper crops as soil amendments [ 23 , 24 ]. These crops (mostly cruciferous vegetables) offer resident antagonistic microflora in the soil for biocontrol of pathogens. For instance, biocontrol of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum that causes lettuce drop was achieved by broccoli incorporation in the soil [ 25 ].

2.3. Microbial Control of Phytopathogenic Fungi

The governmental reviews of the safety of chemical synthetic fungicides result in special interest in microbial fungicide development and use. There are two comprehensive types of microbial fungicides used for biocontrol of plant fungal diseases. The first type directly interacts with the target fungal plant pathogens via various mechanisms such as parasitism, antibiotics production against target pathogens, or even competition with soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi for food, water or space because they are occupying the same ecological niche. The second type indirectly affects target fungal plant pathogens by inducing plant resistance against virulent pathogens. This inducer type can be a low virulent plant-pathogen strain, another microbial species, or their natural products.

In general, microbial antagonists used for biocontrol of plant fungal diseases have multiple mechanisms involved in their action. Trichoderma species, for example, act against soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi through parasitism, production of antibiotics and enzymes that degrade the fungal cell wall, competition for nitrogen or carbon, and also by producing auxin-like compounds causing plant growth promotion [ 26 , 27 ].

Various microbial antagonists have been developed and commercialized to be used against soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi that cause diseases in the above-ground plant parts. Species of Trichoderma , for example Trichoderma harzianum , are one of the most widely used microbial antagonists for biocontrol of plant fungal diseases caused by Fusarium, Rhizoctonia , and many soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi [ 28 ]. Another microbial fungicide is Coniothyrium minitans , which is used for biocontrol of infections of lettuce, oilseed rape, brassicas, beans, and carrots caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum [ 29 ]. The bacterium Paenibacillus jamilae HS-26 was reported to have potent antagonistic effects (inhibiting mycelial growth of fungi) on multiple soil-borne fungal pathogens via releasing extracellular antifungal metabolites and the synthesis of hydrolytic enzymes [ 30 ]. Formulations of Streptomyces cellulosae Actino 48 that produces chitinase were reported to control Sclerotium rolfsii causing peanut soil-borne diseases [ 31 ].

Formulations of microbial fungicides include liquid suspensions, granules, or dusts, which are applied in the soil just before cultivation or directly to plant roots. They can also be formulated as conventional sprays and applied on harvested fruits, plant stems, or leaves. Moreover, unique application methods have been developed such as honey bees’ delivery during pollination [ 32 ]. Bees usually carry Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi (a phytopathogenic fungus that causes mummy blueberry disease) between the flowers of blueberry during pollination. At the same time, the bees can act as ‘flying doctors’ and deliver the bacterial fungicide Bacillus subtilis to the flowers of blueberry to suppress the disease [ 33 ]. Additionally, the endophytic bacterium Bacillus mojavensis was reported to be fungicidal against various phytopathogenic fungi including F. oxysporum , R. solani , and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum [ 34 ].

2.4. Botanical Fungicides

Many published studies reported that plant extracts exhibit significant antifungal activities in vitro . Unfortunately, agar diffusion assays were unsuitably used to detect these activities of plant extracts, while several antifungal compounds found in plant extracts are relatively non-polar and consequently do not diffuse well in agar [ 35 ]. The obtained results were also highly variable from one laboratory to another due to the variation in factors that affect agar diffusion.

Numerous essential oils of plants have the ability to suppress fungal infections that initiate and develop during and after crop harvest and thus extend the shelf-life of stored vegetables and fruits [ 36 , 37 ]. They can also inhibit production of mycotoxins by some species of fungi that cause postharvest decay of stored fruits [ 38 ].

Some plants are able to produce various antimicrobial agents (natural or botanical fungicides) to protect themselves against several plant fungal diseases [ 39 ]. These natural fungicides, such as phytoanticipins and phytoalexins differ in their structure, molecular weight, functions, and classification [ 40 ]. Secondary metabolites produced by plants which can act as natural fungicides for control of phytopathogenic fungi include phenolics, fatty acids, flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, terpenoids, and tannins.

Plant extracts usually have the advantage of comprising various chemicals (antifungal compounds) mixed together, and possibly will work in a synergistic manner against phytopathogenic fungi [ 41 ]. Additionally, diverse mechanisms of antifungal activity employed by these mixtures of compounds could result in a decrease in the resistance of fungal phytopathogens. The following are some examples of commercially available botanical fungicides besides several metabolites produced by plants that displayed effective antifungal activities against fungal phytopathogens in vivo.

2.4.1. Milsana

Milsana is a botanical fungicide extracted from the Reynoutria sachalinensis plant with ethanol to be used for the reduction of some infections that affect greenhouse-grown plants, principally powdery mildew [ 42 ]. It is mostly applied as a preventative agent rather than a treatment. The control mechanisms that Milsana employs to suppress powdery mildew disease of wheat include its antifungal activity as well as inducing resistance of the plant. To effectively reduce powdery mildew that affects young seedlings in glasshouses by about 97%, this botanical fungicide should be applied as spray to run-off once at 48 h before planting [ 43 , 44 ]. Milsana stimulates resistance and the natural immune system of the plant via acting as a natural elicitor of phytoalexins, which are antimicrobial compounds synthesized and accumulated by plants in hypersensitive tissues as a response to pathogen infection [ 45 ].

2.4.2. Jojoba Oil

This vegetable oil has been extracted from the bean of jojoba. It can effectively control powdery mildew fungal disease in grapes and ornamental plants [ 45 , 46 ]. Moreover, its stability, even at elevated temperatures, presents jojoba oil as a broadly functional fungicide in approximately all climatic conditions [ 45 , 46 ]. This botanical fungicide is sprayed at a final concentration of about 1% [ 45 ].

2.4.3. Plant Essential Oils

Plant essential oils are concentrated liquids comprised of volatile chemical compounds from plants. They can be referred to as volatile oils or simply as the oil of the plant from which they were extracted. They are generally extracted by distillation, expression, solvent extraction, or resin tapping. They have many applications, such as flavoring foods and drinks, their use in cosmetics, perfumes, soaps, etc. and aromatherapy (alternative medicine) in which healing effects are attributed to aromatic compounds [ 47 ].

Edris and Farrag [ 48 ] evidenced that essential oils from sweet basil and peppermint in addition to their key aroma constituents (menthol in case of essential oil of peppermint and linalool/eugenol in case of basil oil) have antifungal abilities against some phtopathogenic fungi, including Rhizopus stolonifer , and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum .

Additionally, Calocedrus macrolepis essential oil and its components was reported to have an antifungal effect on fFusarium oxysporum, Fusarium solani, Rhizoctonia solani, Pestalotiopsis funerea, and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [ 49 ].

In another study, essential oils extracted from twenty five different medicinal plant species were confirmed to have inhibitory effects (inhibiting mycelial growth of fungi) on six vital toxinogenic and pathogenic species of fungi ( Fusarium verticillioides, Fusarium oxysporum , Aspergillus fumigatus , Aspergillus flavus, Penicillium brevicompactum, and Penicillium expansum ) [ 50 ].

Elgorban et al. (2015) [ 51 ] demonstrated that essential oils extracted from Eucalyptus globulus Labill , Nigella sativa L., and Allium cepa L. have antifungal activity against Rhizoctonia solani, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum , Fusarium oxysporum , Fusarium verticillioides , and Fusarium solani ).

Elshafie et al. (2016) [ 52 ] characterized the chemical composition of three essential oils extracted from Majorana hortensis , Verbena officinalis , and Salvia officinalis , and their antifungal activity was confirmed against Colletotrichum acutatum and Botrytis cinerea. The chemical structure of studied essential oils was mostly composed of monoterpene compounds and all oils belonging to the chemotype carvacrol/thymol. A more recent work has been conducted by Elshafie et al. (2019) [ 53 ] to study the fungicide effect of essential oil from Solidago canadensis L. and its effect on some postharvest phytopathogenic fungi such as Aspergillus niger , Botrytis cinerea , Monilinia fructicola , and Penicillium expansum was confirmed. Two essential oils derived from Origanum heracleoticum L. and O. majorana L. were reported to have in vitro antifungal activity against some postharvest phytopathogens ( Aspergillus niger, Penicillium expansum , Botrytis cinerea , and Monilinia fructicola ) [ 54 ].