- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

56 New Media and Political Campaigns

Diana Owen (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Madison) is Associate Professor of Political Science and Director of American Studies at Georgetown University, and teaches in the Communication, Culture, and Technology graduate program. She is the author of American Government and Politics in the Information Age with David Paletz and Timothy E. Cook (Flatworld, 2011), New Media and American Politics with Richard Davis (Oxford, 1998) and Media Messages in American Presidential Elections (Greenwood, 1991), and editor of The Internet and Politics: Citizens, Voters, and Activists, with Sarah Oates and Rachel Gibson (Routledge, 2006), and editor of Making a Difference: The Internet and Elections in Comparative Perspective, with Richard Davis, Stephen Ward, and David Taras (Lexington, 2009).

- Published: 01 May 2014

- This version: January 2018

Updated in this version:

Additional citations and brief discussion.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

New media have been playing an increasingly central role in American elections since they first appeared in 1992. While television remains the main source of election information for a majority of voters, digital communication platforms have become prominent. New media have triggered changes in the campaign strategies of political parties, candidates, and political organizations; reshaped election media coverage; and influenced voter engagement. This chapter examines the stages in the development of new media in elections from the use of rudimentary websites to the rise sophisticated social media. It discusses the ways in which new media differ from traditional media in terms of their form, function, and content; identifies the audiences for new election media; and examines the effects on voter interest, knowledge, engagement, and turnout. Going forward, scholars need to employ creative research methodologies to catalogue and analyze new campaign media as they emerge and develop.

The 1992 presidential election ushered in a new era of campaign media. Candidates turned to entertainment venues to circumvent the mainstream press’s stranglehold on the campaign agenda. This development was marked by the signature moments of businessman Ross Perot launching his third party presidential bid on Larry King Live and Democratic nominee Bill Clinton donning dark shades and playing the saxophone on the Arsenio Hall Show . At the same time, voters became more visibly engaged with campaign media, especially through call-in radio and television programs. Communication researchers speculated about the dawn of a new era of campaign media, alternately praising its populist tendencies and lamenting its degradation of political discourse. These forms of new media primarily made use of traditional print, radio, and television media platforms.

In the years since, new technologies have transformed the campaign media system and in the process altered the ways in which campaigns are waged by candidates, reported on by journalists, and experienced by voters. New campaign media have proliferated and become increasingly prominent with each passing election. Social media platforms that facilitate interaction and collaboration in the production, dissemination, and exchange of content have become campaign mainstays. Candidates employ complex media strategies incorporating an ever-changing menu of innovations in conjunction with traditional media management techniques. Campaign reporting is no longer the exclusive province of professional journalists, as bloggers and average citizens cover events and provide commentary that is widely available. Voters look to new media as primary sources of information and participate actively in campaigns through digital platforms.

The New Media Campaign Environment

A multilayered communication environment exists for election campaigns. The media system is transitioning from a broadcast model associated with traditional media where general-interest news items are disseminated to the mass public through a narrowcasting model where carefully crafted messages target discrete audience segments. On the one hand, the mainstream press maintains an identifiable presence. Much original and investigative campaign reporting is conducted by professional journalists, even as financial pressures have forced the industry to reduce their numbers drastically. Mainstream media still validate information disseminated via new media platforms, such as blogs and Twitter feeds. At the same time, the proliferation of new media has increased the diversification and fragmentation of the communication environment. Media are more politically polarized, as niche sources associated with extreme ideological positions appeal to growing sections of the audience. The abundance of new sources makes it possible for voters to tailor their media consumption to conform to their personal tastes ( Sunstein, 2000 ; Jamieson and Cappella, 2008 ; Stroud, 2011 ; Levendusky, 2013 ).

The evolution of campaign communication in the new media era can be construed as three distinct yet overlapping phases, as depicted in Figure 56.1 .

Old Media, New Politics

During the “old media, new politics” phase, candidates used established nonpolitical and entertainment media to bypass mainstream press gatekeepers, who reduced their messages to eight-second sound bites sandwiched between extensive commentary. Candidates sought to reach voters who were less attentive to print and television news through personal appeals in the media venues they frequented. “Old media, new politics” thrives in the current era, as candidates seek the favorable and widespread coverage they can garner from a cover story in People Weekly and appearances on the talk and comedy show circuit ( Baum, 2005 ). This type of election media laid the foundation for the personalized soft news coverage that permeates twenty-first-century new media campaigns. While rudimentary websites, or “brochureware,”—defined as web versions of traditional print campaign flyers—that served as digital repositories of campaign documents first appeared in 1992 ( Davis, 1999 ), old media technologies remained dominant during this phase.

New Media, New Politics 1.0

The second phase—“new media, new politics 1.0”—witnessed the introduction of novel election communication platforms made possible by technological innovations. By the year 2000 election, all major and many minor candidates had basic websites that were heavily text-based ( Bimber and Davis, 2003 ). Campaign websites incorporating interactive elements—including features that allowed users to engage in discussions, donate to candidates, and volunteer—became standard in the 2004 election. Election-related blogs also proliferated, offering voters an alternative to corporate news products ( Cornfield, 2004 ; Foot and Schneider, 2006 ). Internet use in midterm elections lagged somewhat behind presidential campaign applications. Many congressional candidates had basic websites in 2006, but few included blogs, fundraising tools, or volunteer-building applications ( The Bivings Group, 2006 ).

New Media, New Politics 2.0

The 2008 presidential election marked the beginning of the third phase in the evolution of election media—“new media, new politics 2.0.” This period is distinguished by innovations in digital election communication that facilitate networking, collaboration and community building as well as active engagement. Campaign websites became full-service multimedia platforms where voters could find extensive information about the candidates as well as election logistics, access and share videos and ads, blog, and provide commentary, donate, and take part in volunteer activities. The most notable development in 2008 was the use of social media, such as Facebook, and video sharing sites, like YouTube, for peer-to-peer exchange of election information, campaign organizing, and election participation. Mainstream media organizations kept pace with these developments by incorporating social media and video sharing features into their digital platforms. These new media innovations were amplified in the 2010 midterm elections, with Twitter and microblogging sites featured more prominently in the election media mix, and have continued to evolve in subsequent contests. Another important development is campaigns’ use of “big data”—large, detailed data sets compiled from voter files, social media analytics, and consumer data—to target voters with specific messages based on their preferences. Big data also are employed by campaigns and opinion organizations to make predictions about voter behavior and election outcomes ( Nickerson and Rogers, 2014 ).

The Importance of New Media in Elections

The new media’s influence on elections has been substantial. Campaigns provide a laboratory for the development of political applications that carry over to postelection politics and establish new norms for media politics in subsequent contests. The social media innovations that rose to prominence in the 2008 presidential contest became standard practice in the 2010 midterm elections and set the stage for the more prolific development of political applications for handheld devices than was the case in 2004, when the Bush campaign used handheld devices to show campaign ads door to door. As technology continues to advance and the number of social media platforms proliferates, the election media environment has become more diversified, specialized, and fragmented. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have been joined by a host of platforms, such as Reddit, Pinterest, Snapchat, and Vine, that support campaign activities.

Campaign Organizations, Parties, and Grassroots Movements

Candidates have incorporated new media into their organizational strategies for informing, contacting, and mobilizing voters. Candidate websites have come a long way from the days of brochureware and provide users with the opportunity for an individualized experience that can range from simply access biographical information to networking with supporters from across the country. Campaigns have also developed advanced microtargeting methods, including the use of focused text messages to reach specific constituencies, such as ethnic group members and issue constituencies ( Hillygus and Shields, 2008 ; Hendricks and Schill, 2014 ).

The Democratic and Republican parties have developed digital media strategies for enhancing personal outreach to voters. Their websites have become social media hubs that can engage voters during and after elections. The dominant function of the two major parties’ new media strategy is fundraising, and the “donate” button features prominently on all of their platforms. The parties’ outreach to voters continues between elections, especially through the use of regular email and text messages to supporters, which has revitalized parties’ electoral role.

Grassroots political movements have employed new media as a means of getting their message out and mobilizing supporters. In the 2010 midterm elections, the Tea Party movement used websites, blogs, social media, and email to bring national attention to state and local candidates and to promote its antigovernment taxing and spending message ( Lepore, 2010 ). Mainstream and new media coverage of the Tea Party was substantial and resulted in increased public awareness of and momentum behind little-known candidates ( Project for Excellence in Journalism, 2010 ). At the same time, new media strategies can backfire when the mainstream press publicizes unflattering or embarrassing information about candidates. Christine O’Donnell, an unsuccessful Tea Party‒backed candidate for the Senate in Delaware in 2010, received extensive national press coverage for statements about witchcraft she had once made that helped to derail her campaign.

Virtual third-party movements and nonpartisan social media–based platforms for electoral engagement gained traction in the 2012 presidential election. Americans Elect, the most visible and well-financed of these organizations, was unsuccessful in its bid to field a bipartisan presidential ticket through an online nomination process, but managed to get laws passed in more than thirty states that would allow candidates nominated through online processes to get on the ballot, setting the stage for future online presidential candidate recruitment efforts ( Owen, 2015 ).

Campaigns have had to adapt to a more negative and volatile electoral environment. Candidates are subject to constant scrutiny, as their words and actions are closely recorded. Reporters and average citizens can compile information and disseminate it using inexpensive technologies that link easily to networks, where rumors can be spread instantaneously. New media can sustain rumors well after an election. Rumors promulgated by the “birther movement”—that Barack Obama was not qualified to be president because he was not born in the United States—continued to circulate long after he took office.

Media Organizations

The relationship between traditional and new media has gone from adversarial to symbiotic, as new media have become sources of campaign information for professional journalists. Average citizens have become prolific providers of election-related content ranging from short reactions to campaign stories to lengthy firsthand accounts of campaigns events. Mainstream media have integrated new media features into their digital platforms, which have become delivery systems for content that originates from websites, Twitter feeds, blogs, and citizen-produced videos. As a result, messages originating in new media increasingly set the campaign agenda ( Pavlik, 2008 ). Still, established media organizations remain prominent hosts of public election discourse ( Gans, 2010 ).

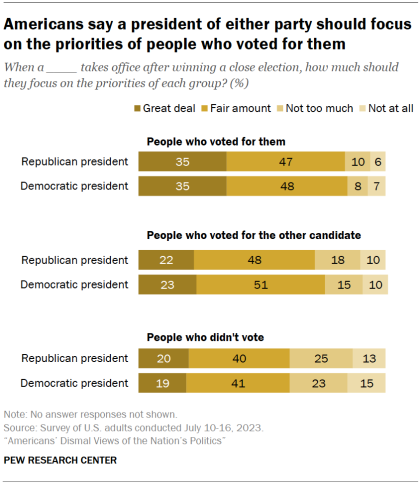

New media constitute an abundant source of election information for an increasing number of voters. While television remains the main source of election news for a majority of people, online sources are gaining popularity ( Smith, 2011 ). The Internet has gone from a supplementary resource for election information to a main source of news for more than a third of voters during presidential campaigns and a quarter of voters during midterm elections. The use of the Internet as a main source in presidential elections has climbed from 3% in 1996 to 47% in 2012. Mainstream television news exposure and hardcopy print newspaper use has dropped markedly over time. Radio’s popularity as a resource for information on presidential elections has increased slightly since the 1980s and early 1990s, largely due to talk radio’s popularity (Table 56.1 ).

Note : Respondents could volunteer more than one main source. The option changed from “newspaper” to “print” in 2014, and magazines were not included as a source.

The Electorate

The role of the new media in fostering a more active electorate is perhaps their most consequential contribution to campaigns. The low barrier to entry allows more voters from diverse constituencies to participate ( Farrar-Myers and Vaughn, 2015 ). Voters use new media to participate in campaigns in traditional and novel ways, such as producing and distributing campaign content, including news stories, short observations, opinion pieces, audio and video accounts, and independent ads. Citizens can not only access and share information through peer-to-peer networks using email and an ever-increasing array of digital platforms but also engage in structured activities organized digitally by campaign organizations, parties, and interest groups; or they can organize campaign events on their own using social media.

Major Research Questions and Findings

A research tradition begun in the 1992 presidential campaign has addressed both macro-level issues about the importance of new media for democratic participation and also more specific questions about the form, content, role, audiences, and effects of new media in particular campaigns. Since the new media’s influence in elections has been dynamic, research findings should be considered within the context of the phases of new media development. As new media have matured, they have become more integral to the electoral process, and their effects are more pronounced.

Form, Function, and Content of New Election Media

In order to address issues dealing with the form, function, and content of new election media, researchers have asked: What distinguishes new media from traditional media in campaigns? Studies examining the characteristics of new media in elections have provided snapshots of new media developments in specific elections and tracked their evolution over time. Dominant traits that set new media apart from traditional ones are interactivity, network connectivity, and the ability to dynamically engage audience members in elections. New media are also flexible and adaptable, as they can accommodate a wide range of campaign applications. Some, such as fundraising, have offline counterparts, while others, like voter-produced election ads, are unique to the digital realm.

Research on candidate websites provides an illustration of research on the form, function, and content of new election media. Studies have traced the rising sophistication of websites across election cycles and analyzed their changing strategic value in campaigns ( Bimber and Davis, 2003 ; Cornfield, 2004 ; Davis, 1999 ; Druckman, Hennessy, Kifer, and Parkin, 2010 ; Druckman, Kifer, and Parkin, 2007 , 2010 ; Foot and Schneider, 2006 ; Stromer-Galley, 2000 ).

Despite the apparent boundary lines of the phases noted earlier, it has become increasingly difficult to draw clear-cut distinctions between traditional and new media. Technology enables the convergence of communication platforms and the formation of hybrid digital media. Convergence refers to the trend of different communication technologies performing similar functions ( Jenkins, 2006 ). Video sharing platforms, like YouTube, have converged with television in elections as they host campaign ads ( Burgess and Green, 2009 ; Pauwels and Hellriegel, 2009 ). As standard formats take on new media elements, hybrid media have evolved. For example, online versions of print newspapers that originally looked similar to their offline counterparts have come to resemble high-level blogs in style and function. Online newspapers have not only become less formal and more entertainment-focused but now also include mechanisms for interactive engagement and accommodate significant multimedia and user-generated content. Research examining the influence of convergence and hybridity on campaign communication has not kept pace with developments that have important consequences for elections.

Campaign Strategy

Scholars have addressed the ways in which candidates, campaign organizations, and political parties incorporate new media into their strategies. Successful political organizations employ multitiered strategies that integrate traditional and new media tactics. As they take into account the audiences for particular media forms, the strategies of candidates and political parties have become more specialized. A strong majority of senior voters rely primarily on traditional print and electronic sources for campaign data, while younger voters are inclined to consume such information on their smart phones. Digital media have made it possible for campaigns to gather data on voters ranging from their voting history and political leanings to their consumer product preferences. They can also take stock of the electorate’s pulse through a wide range of digital polling tools ( Howard, 2005 ).

The question of how much control candidates have over their campaign messaging in the new media environment has also been raised. Some candidacies are better suited to new media strategies than others ( Davis and Owen, 1999 ). Presidential candidates Bill Clinton and Barack Obama were able to negotiate old and new media comfortably. Others such as George H. W. Bush in 1992 and John McCain in 2008, had greater difficulty adapting to the less formal, more relational style of new media. Candidates’ increasing use of social media has influenced media coverage of campaigns but has had less of an influence on the public’s attention to and perceptions of candidates ( Hong and Nadler, 2012 ; Solo, 2014 ).

The growth in the number of actors who can actively participate in the media campaign in the new media era has created challenges for candidates seeking to control their message. Political organizations such as 527 groups, which are not subject to campaign contribution and spending limits, can run campaign ads and mobilize voters online as long as they do not coordinate with a candidate’s campaign committee. The ads they disseminate can complicate messaging strategies even for candidates they are meant to help.

New Media Audiences

Another body of research focuses on the audiences for new media in elections. Here the most basic question is: Who makes up the audiences for new election media? The answer has changed as Internet penetration has become more widespread and people adopt new forms of digital technology. Early political Internet users were younger, male, and educated. However, as the audiences for new election media have expanded exponentially, they increasingly resemble the general population ( Zickuhr, 2010 ).

Fifty-five percent of voters in the 2010 midterm contests used Internet media for some election-relevant purpose ( Smith, 2011 ); increasing to sixty-six percent in 2014 ( Pew Research Center, 2015 ). Still, younger and more educated people are the most inclined to use the most pioneering platforms. Enthusiasm over new media developments in campaigns can at times overshadow the reality that the audiences for all but a few political media sites are generally small ( Hindman, 2009 ) and use of the most innovative campaign applications can be slight (Owen 2011a , b ).

Related research examines the extent to which new outlets supplement or supplant mainstream media for voters. The dynamics underlying audience media use differ for presidential and midterm elections. Voters are gravitating from traditional television and print sources and moving to the Internet for presidential campaign news ( Owen and Davis, 2008 ). Rather than abandoning traditional sources entirely, many people are adding Internet media as a new source of information during midterm elections ( Smith, 2011 ). Local television news, in particular, remains important for midterm election voters ( Owen, 2011b ). Young people, however, are inclined to use online sources to the exclusion of television and print newspapers in both types of campaigns.

Audience use of campaign media is a research focus that raises a key question: What motivates voters to use new election media? Attempts to address this issue have employed uses and gratifications frameworks to examine the motivations underpinning voters’ media use. Many of these studies rely heavily on lists of media motivations and uses that were developed in the pre‒new media era (see Blumler, 1979 ; Owen, 1991 ). Studies adopting these frameworks reveal that voters use new campaign media for guidance, surveillance/information seeking, entertainment, and social utility ( Kaye and Johnson, 2002 ) as well as to reinforce their voting decisions ( Mutz and Martin, 2001 ).

These standard uses and gratifications have been supplemented by campaign media motivations and uses that take into account digital media’s interactivity, networkability, collaborative possibilities, ability to foster engagement ( Ruggiero, 2000 ), and convenience. New media use involves experiences that are more active and goal-directed than those associated with traditional media. These include problem solving, persuading others, relationship maintenance, status seeking, personal insight, and time consumption. Scholars have also identified uses and gratifications that are linked to specific aspects of new election media use ( Johnson and Kaye, 2008 ). Gratifications are derived from participating in virtual communities, as by establishing a peer identity ( LaRose and Eastin, 2004 ). The use of social media fulfills needs including enhancing social connectedness, self-expression, sharing problems, sociability, relationship maintenance, and self-actualization ( Quan-Haase and Young, 2010 ; Shao, 2009 ). Social media also provide a venue for “political mavericks” to express themselves in new ways ( Hendricks and Schill, 2014 ).

New Media Effects in Elections

Researchers have also investigated the relationship between voters’ use of new media and their levels of political attentiveness, knowledge, attitudes, orientations, and engagement. Early studies of the effects of new media on voters’ acquisition of campaign knowledge produced mixed results, while newer research reveals more consistent evidence of information gain ( Bimber, 2001 ; Drew and Weaver, 2006 ; Norris, 2000 ; Prior, 2005 ; Weaver and Drew, 2001 ; Wei and Lo, 2008 ; Semiatin, 2013 ; Hendricks and Schill, 2014 ; Denton, 2014 ). Scholars have also examined the influence of the use of new election media on the development of political attitudes and orientations, such as efficacy and trust ( Johnson, Braima, and Sothirajah, 1999 ; Kenski and Stroud, 2006 , Wang, 2007 ; Zhang, Johnson, Seltzer, and Bichard, 2010 ).

Some studies have found a positive connection between exposure to online media and higher levels of electoral engagement and turnout ( Gueorguieva, 2008 ; Gulati and Williams, 2010 ; Johnson and Kaye, 2003 ; Tolbert and Mcneal, 2003 ; Wang, 2007 ; Bond et al., 2012 ). However, the effects may not be overwhelming ( Boulianne, 2009 ). The online environment may be most relevant for people who are already predisposed toward political engagement (Park and Perry, 2008 , 2009 ). The use of social media does not necessarily increase electoral participation, although it has a positive influence on civic engagement, such as community volunteerism ( Baumgartner and Morris, 2010 ; Zhang, Johnson, Seltzer, and Bichard, 2010 ).

Young Voters

Young voters, those under age 30, came of political age during the Internet era. Unlike older citizens, who established their campaign media habits in the print and television age, this generation has embraced the election online from the outset. A growing body of literature focuses on the ways in which young voters are using new election media and their effects. Studies indicate that this demographic group is out front in terms of using new media for accessing information ( Lupia and Philpot, 2005 ; Shah, McLeod, and Yoon, 2001 ); indeed, many ignore traditional print and broadcast media and rely exclusively on digital sources ( Owen, 2011b ). Young people are also at the forefront of new election media innovation and participation ( Owen, 2008‒2009; Baumgartner and Morris, 2010 ; Gainous and Wagner, 2014 ). However, young voters’ domination of the digital campaign has been dissipating over time, as the “Internet generation” ages and older citizens gain facility with communication technologies.

Unanswered Questions and New Directions

Research to date has established useful baselines for understanding new media and elections. However, many of the questions that guided early work remain contested or only partially addressed. Much of the existing scholarship has employed well-worn theoretical frameworks that are not entirely appropriate for the new media age and have relied on orthodox methodological approaches, such as survey research and content analysis. In order to track new developments and voters’ use of campaign media innovations, theories explaining the new media’s role in elections should be refined or recast. Creative research methodologies such as the use of time gliders to catalogue the emergence and development of new campaign media should be employed, as well as network analysis that captures the dynamics of social media engagement. Political scientists and communication researchers should collaborate with computer science and technology scholars.

Going forward, scholars should critically and creatively address the basic question: How can new media’s influence in elections be identified, measured, assessed, and explained in the current environment? Since the new media environment is changeable, and tracking developments is difficult, this is a challenging proposition. New media applications are introduced and modified, and they sometimes disappear quickly. Audiences’ new media tastes shift, and their engagement with particular platforms can be mercurial. Candidates, parties, media organizations, and average citizens experiment with new media and introduce new scenarios in virtually every campaign.

Theoretical frameworks should be tested for their capacity to accommodate the unique characteristics of new media, with their inherent multipath interactivity, flexibility, unpredictability, and opportunities for more active engagement. Theories should elucidate the challenges new media present to entrenched media and political hierarchies. They also should address the manner in which new media are influencing campaign logistics and strategies. To address the effects of complex audience dynamics, scholars need to develop analytical categories beyond demographics and basic political orientations. Much excitement has been generated by the prospect of using new media for electoral engagement, but the substance and significance of these forms of activation are barely understood. Studies might more deeply assess whether or not this engagement constitutes meaningful and effective political activation.

Standard methodological approaches should be updated for the new media age or used in conjunction with cutting edge methods. Some of the very same tools that are employed by users of digital media can be used by scholars to collect and analyze data. Electronic sources—such as blogs, discussion forums, and email—can function as archives of material that can be automatically searched, retrieved, extracted, and examined using digital tools. Big data can be employed to examine voter orientations and preferences, with the caveat that their objectivity, reliability, and accuracy are suspect. Research strategies might blend big data analysis and traditional survey research ( Metaxas and Mustafaraj, 2012 ; Groves, 2013 ). Audience analysis also can benefit from fresh methodological approaches. People do not consume news online in the same linear fashion that they read the morning newspaper. Instead, they explore news offerings by following a series of links to particular content. Web crawler techniques can be used to examine online election communities. Digital utilities, such as online timeline creators, visually chart the development of new election media and serve as research tools ( Owen, 2011a ). Journals that can handle digital scholarship using multimedia graphics, and interactive exhibits are being developed.

Baum, M. A. 2005 . Talking the vote: Why presidential candidates hit the talk show circuit. American Journal of Political Science , 49(2), 213–234.

Google Scholar

Baumgartner, J. C. , and J. Morris . 2010 . MyFaceTube politics: Social networking websites and political engagement of young people. Social Science Computer Review , 28(1), 24–44.

Bimber, B. 2001 . Information and Political Engagement in America: The Search for Effects of Information Technology at the Individual Level. Political Research Quarterly , 54(1), 53–67.

Bimber, B. , and R. Davis . 2003 . Campaigning online: The Internet in U.S. elections . New York: Oxford University Press.

Google Preview

The Bivings Group. 2006 . The Internet’s role in political campaigns. Research report. Washington, DC: The Bivings Group.

Blumler, J. G. 1979 . The role of theory in uses and gratifications studies. Communication Research , 8(1), 9–36.

Boulianne, S. 2009 . Does Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research. Political Communication , 26(2), 193–211.

Bond, R. M. , C. J. Fariss , J. J., Jones , A. D. I. Kramer , C. Marlow , J. E. Settle , and J. H. Fowler . 2012 . A 61 million-person in social influence and political mobilization. Nature , 489(7415), 295–298.

Burgess, J. , and J. Green . 2009 . YouTube: Online video and participatory culture . Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Cornfield, M. 2004 . Politics moves online: Campaigning and the Internet . New York: The Century Foundation.

Davis, R. 1999 . The web of politics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Davis, R. , and D. Owen . 1999 . New media and American politics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Denton, R., Jr. , ed. 2014 . Studies of communication in the 2012 presidential election . New York: Lexington Books.

Drew, D. , and D. Weaver . 2006 . Voter learning in the 2004 presidential election: Did the media matter? Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly , 68(1), 27–37.

Druckman, J. N. , C. L. Hennessy , M. J. Kifer , and M. Parkin . 2010 . Issue engagement on congressional candidate web sites, 2002–2006. Social Science Computer Review , 28(1), 3–23.

Druckman, J. N. , M. J. Kifer , and M. Parkin . 2007 . The technological development of congressional candidate web sites. Social Science Computer Review , 25(4), 425–442.

Druckman, J. N. , M. J. Kifer , and M. Parkin . 2010 . Timeless strategy meets new medium: Going negative on congressional campaign web sites, 2002–2006. Political Communication , 27(1), 88–103.

Farrar-Myers, V. A. , and J. S. Vaughn . 2015 . Controlling the message . New York: New York University Press.

Foot, K. A. , and S. M. Schneider . 2006 . Web campaigning . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gainous, J. , and K. M. Wagner . 2014 . Tweeting to power: The social media revolution in American politics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Gans, H. 2010 . News & the news media in the digital age: implications for democracy. Daedalus , 139(2), 8–17.

Groves, R. 2013. Can’t live with them; can’t live without them. Paper presented at the Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics, Washington, D.C., March 1.

Gueorguieva, V. 2008 . Voters, MySpace, and YouTube: The impact of alternative communication channels on the 2006 election cycle and beyond. Social Science Computer Review , 26(3), 288–300.

Gulati, G. J. “Jeff,” and C. B. Williams . 2010 . “ Congressional candidates’ use of You Tube in 2008: Its frequency and rationale. Journal of Information Technology and Politics , 7(2), 93–109.

Hendricks, J. A. , and D. Schill (Eds.). 2014 . Presidential campaigning and social media: An analysis of the 2012 campaign . New York: Oxford University Press.

Hillygus, D. S. , and T. G. Shields . 2008 . The persuadable voter . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hindman, M. 2009 . The myth of digital democracy . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hong, S. , and D. Nadler . 2012 . Which candidates do the public discuss online during an election campaign? The use of social media by 2012 presidential candidates and its impact on candidate salience. Government Information Quarterly , 29(4), 455–461.

Howard, P. N. 2005 . Deep democracy, thin citizenship: The impact of digital media in political campaign strategy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 597, 153–170.

Jamieson, K. H. , and J. N. Cappella . 2008 . Echo chamber . New York: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, H. 2006 . Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide . New York: New York University Press.

Johnson, T. J. , M. A. M. Braima , and J. Sothirajah . 1999 . Doing the traditional media sidestep: Comparing the effects of the Internet and other nontraditional media with traditional media in the 1996 presidential campaign. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly , 76(1), 99–123.

Johnson, T. J. , and B. K. Kaye . 2003 . A boost or bust for democracy? How the web influenced political behaviors in the 1996 and 2000 presidential elections. The International Journal of Press/Politics , 8(3), 9–34.

Johnson, T. J. , and B. K. Kaye . 2008 . In blog we trust? deciphering credibility of components of the Internet among politically interested Internet users. Computers in Human Behavior , 25(1), 175–182.

Kaye, B. K. , and T. J. Johnson . 2002 . Online and in the know: Uses and gratifications of the Web for political information. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media , 46(2), 54–71.

Kenski, K. , and N. J. Stroud . 2006 . Connections between Internet use and political efficacy, knowledge, and participation. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media , 50(2), 173–192.

LaRose, R. , and M. S. Eastin . 2004 . A social cognitive theory of Internet uses and gratifications: Toward a new model of media attendance. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media , 48(3), 358–377.

Lepore, J. 2010 . The whites of their eyes . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Levendusky, M. 2013 . How partisan media polarize America . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lupia, A. , and T. S. Philpot . 2005 . Views from inside the net: How websites affect young adults’ political interest. Journal of Politics , 67(4), 1122–1142.

Metaxas, T. , and W. Mustafaraj . 2012 . Social media and the elections. Science , 338(6106), 472–473.

Mutz, D. C. , and P. S. Martin . 2001 . Facilitating communication across lines of political difference: The role of mass media. American Political Science Review , 95(1), 97–114.

Nickerson, D. W. , and T. Rogers . 2014 . Political campaigns and big data. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 28(2), 51–74.

Norris, P. 2000 . A virtuous circle? Political communications in post-industrial democracies . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, D. 1991 . Media messages in American presidential elections . Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Owen, D. 2008– 2009 . Election media and youth political engagement. Journal of Social Science Education , 38(2), 14–25.

Owen, D. 2011 a. Media: The complex interplay of old and new forms. In S. K. Medvic (Ed.), New directions in campaigns and elections (pp. 145–162). New York: Routledge.

Owen, D. 2011b. The Internet and voter decision-making. Paper presented at the conference on Internet, Voting, and Democracy, Center for the Study of Democracy, University of California, Irvine, and the European University Institute, Florence, Laguna Beach, CA, May 14–15.

Owen, D. 2015 . The political culture of American elections. In G. Banita and S. Pohlmann (Eds.), Electoral cultures: American democracy and choice (pp. 205–224). Heidelberg: Universitatsverlag, Publications of the Bavarian American Academy.

Owen, D. , and R. Davis . 2008 . United States: Internet and elections. In S. Ward , D. Owen , R. Davis , and D. Taras (Eds.), Making a difference: A comparative view of the role of the Internet in election politics (pp. 93–112). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Park, H. M. , and J. L. Perry . 2008 . Do campaign web sites really matter in electoral civic engagement? Social Science Computer Review , 26(2), 190–212.

Park, H. M. , and J. L. Perry . 2009 . Do campaign websites really matter in electoral civic engagement? Empirical evidence from the 2004 and 2006 Internet tracking survey. In C. Panagopoulos (Ed.), Politicking online (pp. 101–124). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Pauwels, L. , and P. Hellriegel . 2009 . Strategic and tactical uses of Internet design and infrastructure: The case of YouTube. Journal of Visual Literacy , 28(1), 51–69.

Pavlik, J. V. 2008 . Media in the digital age . New York: Columbia University Press.

Pew Research Center. 2012. “Internet Gains Most as Campaign News Source but Cable TV Still Leads.” Research Report. October 25. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. http://www.journalism.org/2012/10/25/social-media-doubles-remains-limited/

Pew Research Center. 2014. “Political Polarization & Media Habits.” Research Report. October 21. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. http://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/

Pew Research Center. 2015. Politics fact sheet. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/politics-fact-sheet/ (Accessed December 1, 2015).

Prior, M. 2005 . News vs. entertainment: How increasing media choice widens gaps in political knowledge and turnout. American Journal of Political Science , 49(3), 577–592.

Project for Excellence in Journalism. 2010. Parsing election day media—How the midterm message varied by platform. Research report. Washington, DC, November 5. Available at: http://www.journalism.org/analysis_report/blogs_%E2%80%93_commentary_and_conspiracies (Accessed May 11, 2011).

Quan-Haase, A. , and A. L. Young . 2010 . Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bulletin of Science and Technology , 30(5), 350–361.

Ruggiero, T. E. 2000 . Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication and Society , 3(1), 3–37.

Semiatin, R. , ed. 2013 . Campaigns on the cutting edge (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Shah, D. , D. M. McLeod , and So-Hyang Yoon . 2001 . Communication, context, and community: An exploration of print, broadcast, and Internet influences. Communication Research , 28(4), 464–506.

Shao, G. 2009 . Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Research , 19(1), 7–25.

Smith, A. 2011 . The Internet in campaign 2010. Research report. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project.

Solo, A. M. G. 2014 . Political campaigning in the information age . Hershey, PA: Information Science References.

Stromer-Galley, J. 2000 . On-line interaction and why candidates avoid it. Journal of Communication , 50(4), 111–132.

Stroud, N. J. 2011 . Niche news . New York: Oxford University Press.

Sunstein, C. R. 2000 . Republic.com . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tolbert, C. J. , and R. S. Mcneal . 2003 . Unraveling the effects of the Internet on political participation. Political Research Quarterly , 56(2), 175–185.

Wang, Song-In. 2007 . Political use of the Internet, political attitudes, and political participation. Asian Journal of Communication , 17(4), 381–395.

Weaver, D. , and D. Drew . 2001 . Voter learning and interest in the 2000 presidential election: Did the media matter? Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly , 78(4), 41–65.

Wei, R. , and Ven-hwei Lo . 2008 . News media use and knowledge about the 2006 U.S. midterm elections: Why exposure matters in voter learning. International Journal of Public Opinion Research , 20(3), 347–362.

Zhang, W. , T. J. Johnson , T. Seltzer , and S. L. Bichard . 2010 . The revolution will be networked: The influence of social network sites on political attitudes and behavior. Social Science Computer Review , 28(1), 75–92.

Zickuhr, K. Generations 2010. Research report. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Study of Election Campaigning

Cite this chapter.

- Shaun Bowler &

- David M. Farrell

Part of the book series: Contemporary Political Studies ((CONTPOLSTUD))

186 Accesses

6 Citations

Election campaigns attract great attention from voters, media and academics alike. The academics, however, tend to focus their research on the electoral result and on societal and long-term political factors influencing that result. The election campaign — the event of great interest, which has at least some role to play in affecting the result — is usually passed over or at most receives minimal attention. It is generally left to the journalists and pundits to give their insights into the campaign; scanning every television programme and newspaper for the latest news or gossip, scrutinising every campaign development — whether an initiative or gaffe — for its potential effect on the result. These are ‘the boys on the bus,’ the campaign journalists who, emulating Theodore White (1961), provide fascinating accounts of the nitty-gritty of election campaigning. 1 But such studies emphasise the short-term and the ephemeral, rather than the underlying process to any campaign. They necessarily stress the unique rather than the general and as such promote the view of campaigns and campaigning as behaviour specific to each election, indeed to each party.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Abrams, M. (1964), ‘Opinion Polls and Party Propaganda’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 28, pp. 13–29.

Article Google Scholar

Agranoff, R. (ed.) (1976a), The New Style in Election Campaigns , 2nd edn (Boston: Halbrook Press).

Google Scholar

Agranoff, R. (ed.) (1976b), The Management of Election Campaigns (New York: Halbrook Press).

Alexander, H. (ed.), (1989a), Comparative Political Finance in the 1980s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Book Google Scholar

Alexander, H. (ed.), (1989b), ‘Money and Politics: Rethinking a Conceptual Framework’, in H. Alexander (ed.), Comparative Political Finance in the 1980s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Chapter Google Scholar

Arndt, J. (1978), ‘How Broad Should the Marketing-Concept Be?’, Journal of Marketing , 43, pp. 101–3.

Atkinson, M. (1984), Our Masters’ Voices: The Language and Body Language of Politics (London: Methuen).

Bartels, R. (1974) ‘The Identity Crisis in Marketing’, Journal of Marketing , 38, pp. 73–6.

Bernays, E. (ed.), (1955), The Engineering of Consent (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Bochel, J.M. and Denver, D. (1971), ‘Canvassing, Turnout and Party Support: An Experiment’, British Journal of Political Science , 1, pp. 257–69.

Boim, D. (1984), ‘The Telemarketing Center: Nucleus of a Modem Campaign’, Campaigns and Elections , 5, pp. 73–8.

Bowler, S. (1990a), ‘Consistency and Inconsistency in Canadian Party Identifications: Towards an Institutional Approach’, Electoral Studies , 9, pp. 133–47.

Bowler, S. (1990b), ‘Voter Perceptions and Party Strategies: An Empirical Approach’, Comparative Politics , 23, pp. 61–83.

Budge, I. and Farlie, D. (1983), Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-Three Democracies (London: George Allen & Unwin).

Butler, D. and Kavanagh, D. (1988), The British General Election of 1987 (London: Macmillan).

Carman, J. (1973), ‘On the Universality of Marketing’, Journal of Contemporary Business , 2, p. 14.

Chagall, D. (1981), The New King-Makers (New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich).

Chartrand, R. (1972), Computers and Political Campaigning (New York: Spartan Books).

Clark, E. (1981), ‘The Lists Business Boom’, Marketing , (December) pp. 25–8.

Cockerell, M., Hennessy, P. and Walker, D. (1984), Sources Close to the Prime Minister: Inside the Hidden World of the News Manipulators (London: Macmillan).

Crewe, I. and Harrop, M. (eds) (1986), Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1983 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Crewe, I. and Harrop, M. (eds) (1989), Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1987 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Crotty, W. L. (1971), ‘Party Effort and its Impact on the Vote’, American Political Science Review , 65, pp. 439–50.

Crouse, T. (1972), The Boys on the Bus (New York: Random House).

Curtis, G. (1988), The Japanese Way of Politics (New York: Columbia University Press).

Cuthright, P. (1963), ‘Measuring the Impact of Local Party Activity on the General Election Vote’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 27, pp. 372–86.

Dalton, R., Flanagan, S. and Beck, P. (eds) (1984), Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? (Princeton: University Press).

Diamond, E. and Bates, S. (1984), The Spot: The Rise of Political Advertising on Television (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press).

Diamond, E. and Bates, S. (1985), ‘The Ads’, Public Opinion , 7 55–7, 64.

Downs, A. (1957), An Economic Theory of Democracy (New York: Harper & Row).

Eldersveld, S.J. (1956), ‘Experimental Propaganda Techniques and Voting Behavior’, American Political Science Review , 50, pp. 154–65.

Elklit, J. (1991), ‘Sub-National Election Campaigns: The Danish Local Elections of November 1989’, Scandinavian Political Studies , 14, pp. 219–39.

Eriksson, E.M. (1937), ‘President Jackson’s Propaganda Agencies’, Pacific Historical Review 6, pp. 47–57.

Farrell, D. (1986), ‘The Strategy to Market Fine Gael in 1981’, Irish Political Studies , 1, pp. 1–14.

Farrell, D. (1989), ‘Changes in the European Electoral Process: A Trend Towards ‘Americanization’?’, Manchester Papers in Politics , no.6/89.

Farrell, D. and Wortmann, M. (1987), ‘Party Strategies in the Electoral Market: Political Marketing in West Germany, Britain, and Ireland’, European Journal of Political Research , 15, pp. 297–318.

Gosnell, H. (1927), Getting out the Vote: An Experiment in the Stimulation of Voting (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Graham, R. (1984), Spain: Change of a Nation (London: Michael Joseph).

Haggerty, B. (1979), ‘Direct Mail Political Fund Raising’, Public Relations Journal , 35, pp. 10–13.

Harris, P.C. (1982), ‘Politics by Mail: A New Platform’, The Wharton Magazine (Fall), pp. 16–19.

Harrop, M. and Miller, W. L. (1987), Elections and Voters: A Comparative Introduction (Basingstoke: Macmillan).

Hiebert, R., Jones, R., d’Arc Lorenz, J. and Lotito, E. (eds) (1975), The Political Image Merchants: Strategies for the Seventies (Washington: Acropolis Books).

Hofstetter, C. R. and Zukin, C. (1979), ‘TV Network Political News and Advertising in the Nixon and McGovern Campaigns’, Journalism Quarterly , 56, pp. 106–15, 152.

Irvine, W. (1987), ‘Canada, 1945–1980: Party Platforms and Campaign Strategies’, in I. Budge et al., Ideology, Strategy and Party Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Jamieson, K. H. (1984), Packaging the Presidency: A History and Criticism of Presidential Campaign Advertising (Oxford: University Press).

Katz, D. and Eldersveld, S. (1961), ‘The Impact of Local Party Activity upon the Electorate’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 25, pp. 1–24.

Katz, R. (1980), A Theory of Parties and Electoral Systems (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press).

Kelley, S. (1956), Professional Public Relations and Political Power (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press).

Kirchheimer, O. (1966), ‘The Transformation of Western European Party Systems’, in J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner (eds), Political Parties and Political Development (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Kotler, P. (1972), ‘A Generic Concept of Marketing’, Journal of Marketing 36, pp. 46–54.

Kotler, P. (1975), ‘Political Candidate Marketing’, in P. Kotler (ed.), Marketing for Non-Profit Organizations (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall).

Kotler, P. (1980), Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning and Control , 4th edn (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall).

Kotler, P. and Levy, S. J. (1969a), ‘Broadening the Concept of Marketing’, Journal of Marketing , 33, pp. 10–15.

Kotler, P. and Levy, S. J. (1969b), ‘A New Form of Marketing Myopia: Rejoinder to Prof. Luck’, Journal of Marketing , 33, pp. 55–7.

Kramer, G. (1970), ‘The Effects of Precinct-Level Canvassing on Voter Behavior’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 34, pp. 560–72.

Kurjian, D. (1984), ‘Expressions Win Elections’, Campaigns and Elections , 5, pp. 6–11.

Lindon, D. (1976), Marketing Politique et Social (Paris: Dalloz).

Luck, D. J. (1969), ‘Broadening the Concept of Marketing — Too Far’, Journal of Marketing , 33, pp. 53–5.

Luck, D. J. (1974), ‘Social Marketing: Confusion Compounded’, Journal of Marketing , 38, p. 70.

Luntz, F. (1988), Candidates, Consultants and Campaigns (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Lupfer, M. and Price, D. (1972), ‘On the Merits of Face-to-Face Campaigning’, Social Science Quarterly , 55, pp. 534–43.

Mannelli, G. and Cheli, E. (1986), L’immagine del potere: Comportmaneti, atteggiamenti e strategie d’immagine dei leader politici italiani (Milano: Franco Angeli Libri.)

Martel, M. (1983), Political Campaign Debates: Images, Strategies and Tactics (New York: Longman).

Mauser, G. (1983), Political Marketing: An Approach to Campaign Strategy (New York: Praeger).

Mintz, E. (1985), ‘Election Campaign Tours in Canada’, Political Geography Quarterly , 4, pp. 47–54.

Napolitan, J. (1972), The Election Game (New York: Doubleday).

Nimmo, D. (1970), The Political Persuaders: The Techniques of Modern Election Campaigns (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall).

O’Shaughnessy, N.J. (1990), The Phenomenon of Political Marketing (Basingstoke: Macmillan).

O’Shaughnessy, N.J. and G. Peele (1985), ‘Money, Mail and Markets: Reflections on Direct Mail in American Politics’, Electoral Studies , 4, pp. 115–24.

Pedersen, M. (1983), ‘Changing Patterns of Electoral Volatility in European Party Systems, 1948–1977: Explorations in Explanation’, in H. Daalder and P. Mair (eds), West European Party Systems (Beverly Hills: Sage).

Peele, G. (1982), ‘Campaign Consultants’, Electoral Studies , 1, pp. 355–62.

Pitchell, R. J. (1958), ‘Influence of Professional Campaign Management Firms in Partisan Elections in California’, Western Political Quarterly , 11, pp. 278–300.

Poguntke, T. (1989), ‘The ‘New Politics Dimension’ in European Green Parties’, in F. Müller-Rommel (ed.), New Politics in Western Europe: The Rise and Success of Green Parties and Alternative Lists (Boulder, Co.: Westview Press).