- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

The biggest questions about gun violence that researchers would still like to see answered

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The biggest questions about gun violence that researchers would still like to see answered

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/49866299/shutterstock_204546301.0.0.jpg)

There are a few big things we know about gun violence in America: The US has way more guns per capita than any other country. It has far more gun homicides per capita than other wealthy countries. States with more guns have more gun deaths. And people with guns in their homes are more likely to be killed or to kill themselves with guns.

But just as importantly, there’s a lot that researchers still don't know. There’s frustratingly little evidence on what policies work best to reduce gun violence. (Australia saw a drop in homicides and suicides after confiscating everyone’s guns in the 1990s , but that would likely never happen here.) Experts still don’t have a great sense of what impact stricter background checks have, or how the "informal" gun trade operates, or even how people use guns in crimes.

"We have superficial knowledge of most gun violence topics," says Michael Nance, director of the Pediatric Trauma Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. And this ignorance has serious consequences. It’s awfully hard to stop gun violence if we can't even agree on basic facts about how and why it happens.

This ignorance is partly by design. Since the 1990s, Congress has prevented various federal agencies from gathering more detailed data on gun violence. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which has elaborate data gathering and monitoring programs for other public health crises like Ebola or heart disease, has been dissuaded from researching gun violence. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives can't distribute much of its trace data for research purposes. Obamacare limits doctors' ability to gather data on patients' gun use.

To get a sense of what we’re missing, I surveyed a number of researchers in the field and asked them about the most pressing questions about gun violence that they’d like to see answered. Here's what they said.

We still don’t know some very basic facts about gun violence in America

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6653635/149080269.jpg)

1) How are guns actually used? Tom Smith of NORC at the University of Chicago pointed out that "studying how guns are actually used in general" was a top research priority — including the question of how many people use guns for defensive purposes.

Other researchers pointed to related questions like: What percentage of gun owners even commit gun crimes? Why do gun accidents occur? Who's involved? Are criminals deterred by guns? These questions are a basic starting point.

2) Can we get better data on the victims of gun violence? Nance also pointed out that our data on the victims of gun violence leaves a lot to be desired. Researchers typically rely on death data ("one of the few known and reliable data points — you can’t hide the bodies," he says). But without more detailed data on who actually owns guns and who is exposed to guns, it can be hard to put these deaths in context.

And it would be good to have more detailed data on gun injuries that don't result in death. Daniel Webster, a professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says, "We still don’t know nearly enough about nonfatal gunshot wounds, including how often they occur." That makes it much harder to get a full picture of gun violence.

3) What state laws, if any, work best to reduce gun violence? Michael Siegel, a professor of public health at Boston University, pointed to these three (broad) topics as the most pressing unanswered questions:

1. What state laws, if any, are effective in reducing rates of firearm violence? 2. Is there a differential impact of state firearm-related laws on homicide rates among white vs. African-American persons? 3. Are higher gun ownership levels related to higher firearm homicide rates because of a causal relationship or because people respond to high homicide rates by purchasing firearms?

There has already been some research on state-level gun control policies. For example, after Connecticut passed a law requiring gun purchasers to first obtain a license, one study found that gun homicides fell by 40 percent . When Missouri repealed a similar law, gun homicides increased by 23 percent . But, in part because they are retrospective and it’s impossible to run controlled experiments, studies like these remain hotly debated.

And there are all sorts of related questions here that (other) researchers would love to know the answers to. Do limits on high-capacity magazines reduce deaths? Do restrictions on alcohol sales make any difference? What about policies that make concealed carry licenses easier to obtain?

To really dig in, researchers would have to study state policies in far more detail. But, says Siegel, that will require need much better data than is currently on offer. He’d like to see more detailed state-level data on household gun ownership, on firearm policies, and on how well (or not) those policies are actually enforced.

4) How do people who commit gun crimes actually get access to their guns? Cathy Barber, who directs the Means Matter Campaign at the Harvard School of Public Health's Injury Control Research Center, listed these as big unanswered questions:

Pretty much every gun starts out as a legal gun. Among the guns that are actually used in crimes, how did they get there? That is, how many are used by their initial legal purchaser and did that person pass a background check? If the gun was not used by the initial purchaser, how did it get to the person who used it in a crime? Straw purchase? Gun trafficking (buying in a state with lax laws and transporting for street sales in state with stricter laws)? Theft? (and what type of theft? Theft from individual homes or from gun shops or what? And if from people’s homes, do these tend to be unsecured guns kept for self-defense purchases – the gun in the bedside table?), etc., etc. I think that both gun rights people and gun control people would be interested in the very specific answers to these questions and figuring out ways that we all could prevent the sort of cross-overs from legal to illegal possession and use.

A couple of other researchers agreed with this line of inquiry. Here’s Nance: "We need to know how weapons move in society to know how to best limit movement in the wrong direction (to those unfit to own)." And here’s Smith: "Understanding the ‘informal' gun market, that is guns that are acquired from others than licenses firearms dealers and therefore without background checks."

5) Is there any way to predict gun suicides? Nearly 21,000 people in the United States use guns to kill themselves each year, accounting for about two-thirds of all gun deaths. "We need to know more about how to predict who will commit suicide using a firearm," says Webster, "and ways to prevent [it]."

Back in 2013, a report from the Institutes of Medicine added some related questions around this topic that needed answering: Does gun ownership affect whether people kill themselves? And what's the best way to restrict firearm access to those with severe mental illnesses?

6) Does media violence have any impact on actual violence? This question came from Brad Bushman, a professor of communication and psychology at Ohio State University:

My research focuses on media violence. We know that youth who see movie characters drink alcohol are more likely to drink alcohol themselves. Similarly, we know that youth who see movie characters smoke cigarettes are more likely to smoke themselves. What about the impact of youth seeing movie characters with guns? Does exposure to movie characters with guns influence youth attitudes and behaviors about guns (e.g., do they think guns are cooler? are they more willing to own or use a gun? do they think guns make males more masculine?)?

7) What do we know about stopping mass shootings? I’ll add one more question to the list, which was considered a pressing research topic in the 2013 Institutes of Medicine report: "What characteristics differentiate mass shootings that were prevented from those that were carried out?"

One big reason current research into US gun violence is so dismal

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6653641/GettyImages-456691988.jpg)

It’s fair to call gun violence a public health crisis: Some 32,383 Americans were killed by guns in 2013. And for other health crises, like Ebola or heart disease, the CDC usually springs into action, by funding studies and research that look into the best policies to deal with the problem.

But that’s not really the case here. Back in 1996, Congress worked with the National Rifle Association to enact a law banning the CDC from funding any research that would "advocate or promote gun control." Technically, this wasn’t a ban on all gun research (and the CDC wasn’t doing advocacy anyway). But the law seemed vague and menacing enough that the agency shied away from most gun violence research, period.

Funding for gun violence research by the CDC dropped 96 percent between 1996 and 2012. Today, federal agencies spend just $2 million annually on gun violence prevention — compared with, say, $21 million for the study of headaches . And the broader field has withered over that period: Gun studies as a percentage of peer-reviewed research dropped 60 percent since 1996. Today there are only about a dozen researchers in the country whose primary focus is on preventing gun violence.

Private foundations and universities, such as the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, have been partly able to pick up the slack , but private funders can rarely sustain the big, complicated data gathering and monitoring programs that the federal government can conduct. And that’s a problem because, as the researchers above noted, one of the biggest lacunae in gun research is data.

"If you look at other major public health issues, like Zika or Ebola or heart disease, the CDC is really a very authoritative source," says Andrew Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists. "Privately funded research can be helpful, but there’s no substitute for the CDC. They can do monitoring programs, long-term tracking, the stuff that’s hard to fund with a one-off grant from this or that foundation."

Siegel agrees: "The CDC has a critical role to play, so the first matter that needs to be resolved is restoring the CDC’s ability to conduct firearm-related research."

So will this situation ever change? After the Sandy Hook massacre in 2013, President Obama signed an executive order directing the CDC to start studying "the causes of gun violence." But very little has happened in the years since. The CDC didn’t actually budget. The problem, Rosenberg says, is that so long as that congressional amendment is in place, the CDC is unlikely to move forward.

Lately, there have been some calls to restore research. Republican Rep. Jay Dickey, who spearheaded the original CDC amendment, expressed remorse about the whole thing last year: "I wish we had started the proper research and kept it going all this time. I have regrets. … If we had somehow gotten the research going, we could have somehow found a solution to the gun violence without there being any restrictions on the Second Amendment."

Read more: What no politician wants to admit about gun control

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

In This Stream

Pulse gay nightclub shooting in orlando: the deadliest in us history.

- One map that puts America's gun violence epidemic in perspective

- The biggest questions that researchers still have about gun violence in America

- Try to scroll through this graphic and you’ll understand America’s gun problem

Next Up In Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Arizona’s ban spotlights the fraudulence of Trump’s “moderation” on abortion

One state’s big plan to fix the high cost of college

Does it matter if Carrie Bradshaw is the worst?

The Michigan school shooter’s parents face precedent-setting sentences

The Supreme Court will decide if states can ban lifesaving abortions

What’s behind the latest right-wing revolt against Mike Johnson

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An Examination of US School Mass Shootings, 2017–2022: Findings and Implications

Antonis katsiyannis.

1 Department of Education and Human Development, College of Education, Clemson University, 101 Gantt Circle, Room 407 C, Clemson, SC 29634 USA

Luke J. Rapa

2 Department of Education and Human Development, College of Education, Clemson University, 101 Gantt Circle, Room 409 F, Clemson, SC 29634 USA

Denise K. Whitford

3 Steven C. Beering Hall of Liberal Arts and Education, Purdue University, 100 N. University Street, BRNG 5154, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2098 USA

Samantha N. Scott

4 Department of Education and Human Development, College of Education, Clemson University, 101 Gantt Circle, Room G01A, Clemson, SC 29634 USA

Gun violence in the USA is a pressing social and public health issue. As rates of gun violence continue to rise, deaths resulting from such violence rise as well. School shootings, in particular, are at their highest recorded levels. In this study, we examined rates of intentional firearm deaths, mass shootings, and school mass shootings in the USA using data from the past 5 years, 2017–2022, to assess trends and reappraise prior examination of this issue.

Extant data regarding shooting deaths from 2017 through 2020 were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, the web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS), and, for school shootings in particular (2017–2022), from Everytown Research & Policy.

The number of intentional firearm deaths and the crude death rates increased from 2017 to 2020 in all age categories; crude death rates rose from 4.47 in 2017 to 5.88 in 2020. School shootings made a sharp decline in 2020—understandably so, given the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent government or locally mandated school shutdowns—but rose again sharply in 2021.

Conclusions

Recent data suggest continued upward trends in school shootings, school mass shootings, and related deaths over the past 5 years. Notably, gun violence disproportionately affects boys, especially Black boys, with much higher gun deaths per capita for this group than for any other group of youth. Implications for policy and practice are provided.

On May 24, 2022, an 18-year-old man killed 19 students and two teachers and wounded 17 individuals at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX, using an AR-15-style rifle. Outside the school, he fired shots for about 5 min before entering the school through an unlocked side door and locked himself inside two adjoining classrooms killing 19 students and two teachers. He was in the school for over an hour (78 min) before being shot dead by the US Border Patrol Tactical Unit, though police officers were on the school premises (Sandoval, 2022 ).

The Robb Elementary School mass shooting, the second deadliest school mass shooting in American history, is the latest calamity in a long list of tragedies occurring on public school campuses in the USA. Regrettably, these tragedies are both a reflection and an outgrowth of the broader reality of gun violence in this country. In 2021, gun violence claimed 45,027 lives (including 20,937 suicides), with 313 children aged 0–11 killed and 750 injured, along with 1247 youth aged 12–17 killed and 3385 injured (Gun Violence Archive, 2022a ). Mass shootings in the USA have steadily increased in recent years, rising from 269 in 2013 to 611 in 2020. Mass shootings are typically defined as incidents in which four or more people are killed (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a ). However, the Gun Violence Archive considers mass shootings to be incidents in which four or more people are injured (Gun Violence Archive, 2022b ). Regardless of these distinctions in definition, in 2020, there were 19,384 gun murders, representing a 34% increase from the year before, a 49% increase over a 5-year period, and a 75% increase over a 10-year period (Pew Research Center, 2022 ). Regarding school-based shootings, to date in 2022, there have been at least 95 incidents of gunfire on school premises, resulting in 40 deaths and 76 injuries (Everytown Research & Policy, 2022b ). Over the past few decades, school shootings in the USA have become relatively commonplace: there were more in 2021 than in any year since 1999, with the median age of perpetrators being 16 (Washington Post, 2022 ; see also, Katsiyannis et al., 2018a ). Additionally, analysis of Everytown’s Gunfire on School Grounds dataset and related studies point to several key observations to be considered in addressing this challenge. For example, 58% of perpetrators had a connection to the school, 70% were White males, 73 to 80% obtained guns from home or relatives or friends, and 100% exhibited warning signs or showed behavior that was of cause for concern; also, in 77% of school shootings, at least one person knew about the shooter’s plan before the shooting events occurred (Everytown Research & Policy, 2021a ).

The USA has had 57 times as many school shootings as all other major industrialized nations combined (Rowhani-Rahbar & Moe, 2019 ). Guns are the leading cause of death for children and teens in the USA, with children ages 5–14 being 21 times and adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 being 23 times more likely to be killed with guns compared to other high-income countries. Furthermore, Black children and teens are 14 times and Latinx children and teens are three times more likely than White children to die by guns (Everytown Research & Policy, 2021b ). Children exposed to violence, crime, and abuse face a host of adverse challenges, including abuse of drugs and alcohol, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, school failure, and involvement in criminal activity (Cabral et al., 2021 ; Everytown Research and Policy, 2022b ; Finkelhor et al., 2013 ).

Yet, despite gun violence being considered a pressing social and public health issue, federal legislation passed in 1996 has resulted in restricting funding for the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The law stated that no funding earmarked for injury prevention and control may be used to advocate or promote firearm control (Kellermann & Rivara, 2013 ). More recently, in June 2022, the US Supreme Court struck down legislation restricting gun possession and open carry rights (New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., Inc. v. Bruen, 2021 ), broadening gun rights and increasing the risk of gun violence in public spaces. Nonetheless, according to Everytown Research & Policy ( 2022a ), states with strong gun laws experience fewer deaths per capita. In the aggregate, states with weaker gun laws (i.e., laws that are more permissive) experience 20.0 gun deaths per 100,000 residents versus 7.4 per 100,000 in states with stronger laws. The association between gun law strength and per capita death is stark (see Table Table1 1 ).

Gun law strength and gun law deaths per 100,000 residents

Accounting for the top eight and the bottom eight states in gun law strength, gun law strength and gun deaths per 100,000 are correlated at r = − 0.85. Stronger gun laws are thus meaningfully linked with fewer deaths per capita. Data obtained from Everytown Research & Policy ( 2022a )

Notwithstanding the publicity involving gun shootings in schools, particularly mass shootings, violence in schools has been steadily declining. For example, in 2020, students aged 12–18 experienced 285,400 victimizations at school and 380,900 victimizations away from school; an annual decrease of 60% for school victimizations (from 2019 to 2020) (Irwin et al., 2022 ). Similarly, youth arrests in general in 2019 were at their lowest level since at least 1980; between 2010 and 2019, the number of juvenile arrests fell by 58%. Yet, arrests for murder increased by 10% (Puzzanchera, 2021 ).

In response to school violence in general, and school shootings in particular, schools have increasingly relied on increased security measures, school resource officers (SROs), and zero tolerance policies (including exclusionary and aversive measures) in their attempts to curb violence and enhance school safety. In 2019–2020, public schools reported controlled access (97%), the use of security cameras (91%), and badges or picture IDs (77%) to promote safety. In addition, high schools (84%), middle schools (81%), and elementary schools (55%) reported the presence of SROs (Irwin et al., 2022 ). Research, however, has indicated that the presence of SROs has not resulted in a reduction of school shooting severity, despite their increased prevalence. Rather, the type of firearm utilized in school shootings has been closely associated with the number of deaths and injuries (Lemieux, 2014 ; Livingston et al., 2019 ), suggesting implications for reconsideration of the kinds of firearms to which individuals have access.

Zero tolerance policies, though originally intended to curtail gun violence in schools, have expanded to cover a host of incidents (e.g., threats, bullying). Notwithstanding these intentions, these policies are generally ineffective in preventing school violence, including school shootings (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008 ; Losinski et al., 2014 ), and have exacerbated the prevalence of youths’ interactions with law enforcement in schools. From the 2015–2016 to the 2017–2018 school years, there was a 5% increase in school-related arrests and a 12% increase in referrals to law enforcement (U.S. Department of Education, 2021 ); in 2017–18, about 230,000 students were referred to law enforcement and over 50,000 were arrested (The Center for Public Integrity, 2021 ). Law enforcement referrals have been a persistent concern aiding the school-to-prison pipeline, often involving non-criminal offenses and disproportionally affecting students from non-White backgrounds as well as students with disabilities (Chan et al., 2021 ; The Center for Public Integrity, 2021 ).

The consequences of these policies are thus far-reaching, with not only legal ramifications, but social-emotional and academic ones as well. For example, in 2017–2018, students missed 11,205,797 school days due to out-of-school suspensions during that school year (U.S. Department of Education, 2021 ), there were 96,492 corporal punishment incidents, and 101,990 students were physically restrained, mechanically restrained, or secluded (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, 2020 ). Such exclusionary and punitive measures have long-lasting consequences for the involved students, including academic underachievement, dropout, delinquency, and post-traumatic stress (e.g., Cholewa et al., 2018 ). Moreover, these consequences disproportionally affect culturally and linguistically diverse students and students with disabilities (Skiba et al., 2014 ; U.S. General Accountability Office, 2018 ), often resulting in great societal costs (Rumberger & Losen, 2017 ).

In the USA, mass killings involving guns occur approximately every 2 weeks, while school shootings occur every 4 weeks (Towers et al., 2015 ). Given the apparent and continued rise in gun violence, mass shootings, and school mass shootings, we aimed in this paper to reexamine rates of intentional firearm deaths, mass shootings, and school mass shootings in the USA using data from the past 5 years, 2017–2022, reappraising our analyses given the time that had passed since our earlier examination of the issue (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a , b ).

As noted in Katsiyannis et al., ( 2018a , b ), gun violence, mass shootings, and school shootings have been a part of the American way of life for generations. Such shootings have grown exponentially in both frequency and mortality rate since the 1980s. Using the same criteria applied in our previous work (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a , b ), we evaluated the frequency of shootings, mass shootings, and school mass school shootings from January 2017 through mid-July 2022. Extant data regarding shooting deaths from 2017 through 2020 were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, utilizing the web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS), and for school shootings from 2017 to 2022 from Everytown Research & Policy ( https://everytownresearch.org ), an independent non-profit organization that researches and communicates with policymakers and the public about gun violence in the USA. Intentional firearm death data were classified by age, as outlined in Katsiyannis et al., ( 2018a , b ), and the crude rate was calculated by dividing the number of deaths times 100,000, by the total population for each individual category.

The number of intentional firearm deaths and the crude death rates increased from 2017 to 2020 in all age categories. In absolute terms, the number of deaths rose from 14,496 in 2017 to 19,308 in 2020. In accord with this rise in the absolute number of deaths, crude death rates rose from 4.47 in 2017 to 5.88 in 2020. Table Table2 2 provides the crude death rate in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, the most current years with data available. Figure 1 provides the raw number of deaths across the same time period.

Intentional firearm deaths across the USA (2017–2020)

Data obtained from WISQARS (2022)

Intentional firearm deaths across the USA (2017–2020). Note. Data obtained from WISQARS (2022)

As expected, in 2020, the number of fatal firearm injuries increased sharply from age 0–11 years, roughly elementary school age, to age 12–18 years, roughly middle school and high school age. Table Table3 3 provides the crude death rates of children in 2020 who die from firearms. Males outnumbered females in every category of firearm deaths, including homicide, police violence, suicide, and accidental shootings, as well as for undetermined reasons for firearm discharge. Black males drastically surpassed all other children in the number of firearm deaths (2.91 per 100,000 0–11-year-olds; 57.10 per 100,000 12–18-year-olds). Also, notable is the high number of Black children 12–18 years killed by guns (32.37 per 100,000), followed by American Indian and Alaska Native children (18.87 per 100,000), in comparison to White children (12.40 per 100,000 children), Hispanic/Latinx children (8.16 per 100,000), and Asian and Pacific Islander children (2.95 per 100,000). A disproportionate number of gun deaths were also seen for Black girls relative to other girls (1.52 per 100,000 0–11-year-olds; 7.01 per 100,000 12–18-year-olds).

Fatal firearm injuries for children age 0–18 across the USA in 2020

AN Alaska Native; – indicates 20 or fewer cases

Mass shootings and mass shooting deaths increased from 2017 to 2019, decreased in 2020, and then increased again in 2021. School shootings made a sharp decline in 2020—understandably so, given the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent government or locally mandated school shutdowns—but rose again sharply in 2021. Current rates reveal a continued increase, with numbers at the beginning of 2022 already exceeding those of 2017. School mass shooting counts were relatively low between 2017 through 2022, with four total during that time frame. Figure 2 provides raw numbers for mass shootings, school shootings, and school mass shootings from 2017 through 2022. Importantly, figures from the recent Uvalde, TX, school mass shooting at Robb Elementary School had not yet been recorded in the relevant databases at the time of this writing. With those deaths accounted for, 2022 is already the deadliest year for school mass shootings in the past 5 years.

Mass shootings, school shootings, and mass school shootings across the USA (2017–2022). Note. Data obtained from Everytown Research and Policy. Overlap present between all three categories

Gun violence in the USA, particularly mass shootings on the grounds of public schools, continues to be a pressing social and public health issue. Recent data suggest continued upward trends in school shootings, school mass shootings, and related deaths over the past 5 years—patterns that disturbingly mirror general gun violence and intentional shooting deaths in the USA across the same time period. The impacts on our nation’s youth are profound. Notably, gun violence disproportionately affects boys, especially Black boys, with much higher gun deaths per capita for this group than for any other group of youth. Likewise, Black girls are disproportionately affected compared to girls from other ethnic/racial groups. Moreover, while the COVID-19 pandemic and school shutdowns tempered gun violence in schools at least somewhat during the 2020 school year—including school shootings and school mass shootings—trend data show that gun violence rates are still continuing to rise. Indeed, gun violence deaths resulting from school shootings are at their highest recorded levels ever (Irwin et al., 2022 ).

Implications for Schools: Curbing School Violence

In recent years, the implementation of Multi-Tier Systems and Supports (MTSS), including Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Response to Intervention (RTI), has resulted in improved school climate and student engagement as well as improved academic and behavioral outcomes (Elrod et al., 2022 ; Santiago-Rosario et al., 2022 ; National Center for Learning Disabilities, n.d.). Such approaches have implications for reducing school violence as well. PBIS uses a tiered framework intended to improve student behavioral and academic outcomes; it creates positive learning environments through the implementation of evidence-based instructional and behavioral interventions, guided by data-based decision-making and allocation of students across three tiers. In Tier 1, schools provide universal supports to all students in a proactive manner; in Tier 2, supports are aimed to students who need additional academic, behavioral, or social-emotional intervention; and in Tier 3, supports are provided in an intensive and individualized manner (Lewis et al., 2010 ). The implementation of PBIS has resulted in an improved school climate, fewer office referrals, and reductions in out-of-school suspensions (Bradshaw et al., 2010 ; Elrod et al., 2010 , 2022 ; Gage et al., 2018a , 2018b ; Horner et al., 2010 ; Noltemeyer et al., 2019 ). Likewise, RTI aims to improve instructional outcomes through high-quality instruction and universal screening for students to identify learning challenges and similarly allocates students across three tiers. In Tier 1, schools implement high-quality classroom instruction, screening, and group interventions; in Tier 2, schools implement targeted interventions; and in Tier 3, schools implement intensive interventions and comprehensive evaluation (National Center for Learning Disabilities, n.d ). RTI implementation has resulted in improved academic outcomes (e.g., reading, writing) (Arrimada et al., 2022 ; Balu et al., 2015 ; Siegel, 2020 ) and enhanced school climate and student behavior.

In order to support students’ well-being, enhance school climate, and support reductions in behavioral issues and school violence, schools should consider the implementation of MTSS, reducing reliance on exclusionary and aversive measures such as zero tolerance policies, seclusion and restraints, corporal punishment, or school-based law enforcement referrals and arrests (see Gage et al., in press ). Such approaches and policies are less effective than the use of MTSS, exacerbate inequities and enhance disproportionality (particularly for youth of color and students with disabilities), and have not been shown to reduce violence in schools.

Implications for Students: Ensuring Physical Safety and Supporting Mental Health

Students should not have to attend school and fear becoming victims of violence in general, no less gun violence in particular. Schools must ensure the physical safety of their students. Yet, as the substantial number of school shootings continues to rise in the USA, so too does concern about the adverse impacts of violence and gun violence on students’ mental health and well-being. Students are frequently exposed to unavoidable and frightening images and stories of school violence (Child Development Institute, n.d. ) and are subject to active shooter drills that may not actually be effective and, in some cases, may actually induce trauma (Jetelina, 2022 ; National Association of School Psychologists & National Association of School Resources Officers, 2021 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). In turn, students struggle to process and understand why these events happen and, more importantly, how they can be prevented (National Association of School Psychologists, 2015 ). School personnel should be prepared to support the mental health needs of students, both in light of the prevalence of school gun violence and in the aftermath of school mass shootings.

Research provides evidence that traumatic events, such as school mass shootings, can and do have mental health consequences for victims and members of affected communities, leading to an increase in post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression, and other psychological systems (Lowe & Galea, 2017 ). At the same time, high media attention to such events indirectly exposes and heightens feelings of fear, anxiety, and vulnerability in students—even if they did not attend the school where the shooting occurred (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2020 ). Students of all ages may experience adjustment difficulties and engage in avoidance behaviors (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2020 ). As a result, school personnel may underestimate a student’s distress after a shooting and overestimate their resilience. In addition, an adult’s difficulty adjusting in the wake of trauma may also threaten a student’s sense of well-being because they may believe their teachers cannot provide them with the protection they need to remain safe in school (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2020 ).

These traumatic events have resounding consequences for youth development and well-being. However, schools continue to struggle to meet the demands of student mental health needs as they lack adequate funding for resources, student support services, and staff to provide the level of support needed for many students (Katsiyannis et al., 2018a ). Despite these limiting factors, children and youth continue to look to adults for information and guidance on how to react to adverse events. An effective response can significantly decrease the likelihood of further trauma; therefore, all school personnel must be prepared to talk with students about their fears, to help them feel safe and establish a sense of normalcy and security in the wake of tragedy (National Association of School Psychologists, 2016 ). Research suggests a number of strategies can be utilized by educators, school leaders, counselors, and other mental health professionals to support the students and staff they serve.

Recommendations for Educators

The National Association of School Psychologists ( 2016 ) recommends the following practices for educators to follow in response to school mass shootings. Although a complex topic to address, the issue needs to be acknowledged. In particular, educators should designate time to talk with their students about the event, and should reassure students that they are safe while validating their fears, feelings, and concerns. Recognizing and stressing to students that all feelings are okay when a tragedy occurs is essential. It is important to note that some students do not wish to express their emotions verbally. Other developmentally appropriate outlets, such as drawing, writing, reading books, and imaginative play, can be utilized. Educators should also provide developmentally appropriate explanations of the issue and events throughout their conversations. At the elementary level, students need brief, simple answers that are balanced with reassurances that schools are safe and that adults are there to protect them. In the secondary grades, students may be more vocal in asking questions about whether they are truly safe and what protocols are in place to protect them at school. To address these questions, educators can provide information related to the efforts of school and community leaders to ensure school safety. Educators should also review safety procedures and help students to identify at least one adult in the building to whom they can go if they feel threatened or at risk. Limiting exposure to media and social media is also important, as developmentally inappropriate information can cause anxiety or confusion. Educators should also maintain a normal routine by keeping a regular school schedule.

Recommendations for School Leaders

Superintendents, principals, and other school administrative personnel are looked upon to provide leadership and comfort to staff, students, and parents during a tragedy. Reassurance can be provided by reiterating safety measures and student supports that are in place in their district and school (The National Association of School Psychologists, 2015 ). The NASP recommends the following practices for school leaders regarding addressing student mental health needs directly. First, school leaders should be a visible, welcoming presence by greeting students and visiting classrooms. School leaders should also communicate with the school community, including parents and students, about their efforts to maintain safe and caring schools through clear behavioral expectations, positive behavior interventions and supports, and crisis planning preparedness. This can include the development of press releases for broad dissemination within the school community. School leaders should also provide crisis training and professional development for staff, based upon assessments of needs and targeted toward identified knowledge or skill gaps. They should also ensure the implementation of violence prevention programs and curricula in school and review school safety policies and procedures to ensure that all safety issues are adequately covered in current school crisis plans and emergency response procedures.

Recommendations for Counselors and Mental Health Professionals

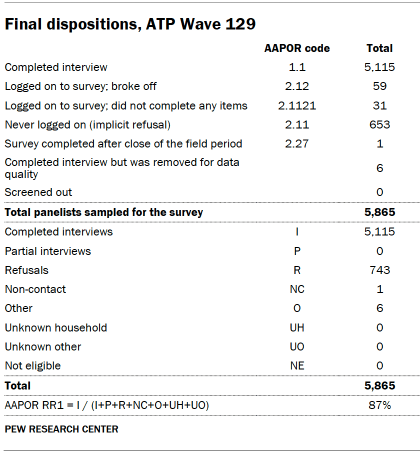

School counselors offer critical assistance to their buildings’ populations as they experience crises or respond to emergencies (American School Counselor Association, 2019 ; Brown, 2020 ). Two models that stand out in the literature utilized by counselors in the wake of violent events are the Preparation, Action, Recovery (PAR) model and the Prevent and prepare; Reaffirm; Evaluate; provide interventions and Respond (PREPaRE) model. PREPaRE is the only comprehensive, nationally available training curriculum created by educators for educators (The National Association of School Psychologists, n.d. ). Although beneficial, neither the PAR nor PREPaRE model directly addresses school counselors’ responses to school shootings when their school is directly affected (Brown, 2020 ). This led to the development of the School Counselor’s Response to School Shootings-Framework of Recommendations (SCRSS-FR) model, which includes six stages, each of which has corresponding components for school counselors who have lived through a school mass shooting. Each of these models provides the necessary training to school-employed mental health professionals on how to best fill the roles and responsibilities generated by their membership on school crisis response teams (The National Association of School Psychologists, n.d. ).

Other Implications: Federal and State Policy

Recent events at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX, prompted the US Congress to pass landmark legislation intended to curb gun violence, enhancing background checks for prospective gun buyers who are under 21 years of age as well as allowing examination of juvenile records beginning at age 16, including health records related to prospective gun buyers’ mental health. Additionally, this legislation provides funding that will allow states to implement “red flag laws” and other intervention programs while also strengthening laws related to the purchase and trafficking of guns (Cochrane, 2022 ). Yet, additional legislation reducing or eliminating access to assault rifles and other guns with large capacity magazines, weapons that might easily be deemed “weapons of mass destruction,” is still needed (Interdisciplinary Group on Preventing School & Community Violence, 2022 ; see also Flannery et al., 2021 ). In 2019, the US Congress started to appropriate research funding to support research on gun violence, with $25 million in equal shares provided on an annual basis from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health (Roubein, 2022 ; Wan, 2019 ). Additional research is, of course, still needed.

Despite legislative progress, and while advancements in gun legislation are meaningful and have the potential to aid in the reduction of gun violence in the USA, school shootings and school mass shootings are something schools and students will contend with in the months and years ahead. This reality has serious implications for schools and for students, points that need serious consideration. Therefore, it is imperative that gun violence is framed as a pressing national public health issue deserving attention, with drastic steps needed to curb access to assault rifles and guns with high-capacity magazines, based on extensive and targeted research. As noted, Congress, after many years of inaction, has started to appropriate funds to address this issue. However, the level of funding is still minimal in light of the pressing challenge that gun violence presents. Furthermore, the messaging of conservative media, the National Rifle Association (NRA) and republican legislators framing access to all and any weapons—including assault rifles—as a constitutional right under the second amendment bears scrutiny. Indeed, the second amendment denotes that “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Security of the nation is arguably the intent of the amendment, an intent that is clearly violated as evidenced in the ever-increasing death toll associated with gun violence in the USA.

Whereas federal legislation would be preferable, the possibility of banning assault weapons is remote (in light of recent Congressional action). Similarly, state action has been severely curtailed in light of the US Supreme Court’s decision regarding New York state law. However, data on gun fatalities and injuries, the correspondence of gun violence to laws regulating access across the world and states, and failed security measures such as armed guards posted in schools (e.g., Robb Elementary School) must be consistently emphasized. Additionally, the widespread sense of immunity for gun manufacturers should be tested in the same manner that tobacco manufacturers and opioid pharmaceuticals have been. The success against such tobacco and opioid manufacturers, once unthinkable, is a powerful precedent to consider for how the threat of gun violence against public health might be addressed.

Author Contribution

AK conceived of and designed the study and led the writing of the manuscript. LJR collaborated on the study design, contributed to the writing of the study, and contributed to the editing of the final manuscript. DKW analyzed the data and wrote up the results. SNS contributed to the writing of the study.

Declarations

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. The American Psychologist. 2008; 63 (9):852–862. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.63.9.852. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American School Counselor Association (2019). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th edn.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

- Arrimada M, Torrance M, Fidalgo R. Response to intervention in first-grade writing instruction: A large-scale feasibility study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2022; 35 (4):943–969. doi: 10.1007/s11145-021-10211-z. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balu, R., Zhu, P., Doolittle, F., Schiller, E., Jenkins, J., & Gersten, R. (2015). Evaluation of response to intervention practices for elementary school reading (NCEE 2016–4000). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Bradshaw CP, Mitchell MM, Leaf PJ. Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2010; 12 (3):133–148. doi: 10.1177/1098300709334798. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown CH. School counselors’ response to school shootings: Framework of recommendations. Journal of Educational Research and Practice. 2020; 10 (1):18. doi: 10.5590/jerap.2020.10.1.18. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cabral, M., Kim, B., Rossin-Slater, M., Schnell, M., & Schwandt, H. (2021). Trauma at school: The impacts of shootings on students’ human capital and economic outcomes. A working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w28311

- Chan P, Katsiyannis A, Yell M. Handcuffed in school: Legal and practice considerations. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2021; 5 (3):339–350. doi: 10.1007/s41252-021-00213-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Child Development Institute. (n.d.). How to talk to kids about violence. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://childdevelopmentinfo.com/how-to-be-a-parent/communication/talk-to-kids-violence/

- Cholewa B, Hull MF, Babcock CR, Smith AD. Predictors and academic outcomes associated with in-school suspension. School Psychology Quarterly. 2018; 33 (2):191–199. doi: 10.1037/spq0000213. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cochrane, E. (2022). Congress passes bipartisan gun legislation, clearing it for Biden. The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/us/politics/gun-control-bill-congress.html

- Elrod BG, Rice KG, Bradshaw CP, Mitchell MM, Leaf PJ. Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2010; 12 (3):133–148. doi: 10.1177/1098300709334798. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elrod BG, Rice KG, Meyers J. PBIS fidelity, school climate, and student discipline: A longitudinal study of secondary schools. Psychology in the Schools. 2022; 59 (2):376–397. doi: 10.1002/pits.22614. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2021a). Keeping our schools safe: A plan for preventing mass shootings and ending all gun violence in American schools. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/report/preventing-gun-violence-in-american-schools/

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2021b). The impact of gun violence on children and teens. Retrieved, June 21, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-impact-of-gun-violence-on-children-and-teens/

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2022a). Gun law rankings. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/rankings/

- Everytown Research & Policy. (2022b). Gunfire on school grounds in the United States. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://everytownresearch.org/maps/gunfire-on-school-grounds/

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck AM, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013; 167 (7):614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flannery, D. J., Fox, J. A., Wallace, L., Mulvey, E., & Modzeleski, W. (2021). Guns, school shooters, and school safety: What we know and directions for change. School Psychology Review, 50 (2-3), 237–253.

- Gage NA, Lee A, Grasley-Boy N, Peshak GH. The impact of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports on school suspensions: A statewide quasi-experimental analysis. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2018; 20 (4):217–226. doi: 10.1177/1098300718768204. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gage, N. A., Rapa, L. J., Whitford, D. K., & Katsiyannis, A. (Eds.) (in press). Disproportionality and social justice in education . Springer

- Gage N, Whitford DK, Katsiyannis A. A review of schoolwide positive behavior interventions and supports as a framework for reducing disciplinary exclusions. The Journal of Special Education. 2018; 52 :142–151. doi: 10.1272/74060629214686796178874678. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gun Violence Archive. (2022a). Gun violence archives 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/past-tolls

- Gun Violence Archive. (2022b). Charts and maps. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/

- Horner RH, Sugai G, Anderson CM. Examining the evidence base for schoolwide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptional Children. 2010; 42 (8):1–14. doi: 10.17161/fec.v42i18.6906. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Interdisciplinary Group on Preventing School and Community Violence. (2022). Call for action to prevent gun violence in the United States of America. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://www.dropbox.com/s/006naaah5be23qk/2022%20Call%20To%20Action%20Press%20Release%20and%20Statement%20COMBINED%205-27-22.pdf?dl=0

- Irwin, V., Wang, K., Cui, J., & Thompson, A. (2022). Report on indicators of school crime and safety: 2021 (NCES 2022–092/NCJ 304625). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, DC. Retrieved July 21, 2022 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2022092

- Jetelina, K. (2022). Firearms: What you can do right now. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://yourlocalepidemiologist.substack.com/p/firearms-what-you-can-do-right-now

- Katsiyannis A, Whitford D, Ennis R. Historical examination of United States school mass shootings in the 20 th and 21 st centuries: Implications for students, schools, and society. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018; 27 :2562–2573. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1096-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katsiyannis A, Whitford D, Ennis R. Firearm violence across the lifespan: Relevance and theoretical impact on child and adolescent educational prospects. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018; 27 :1748–1762. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1035-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kellermann AL, Rivara FP. Silencing the science on gun research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013; 309 (6):549–550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.208207. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lemieux F. Effect of gun culture and firearm laws on firearm violence and mass shootings in the United States: A multi-level quantitative analysis. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences. 2014; 9 (1):74–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis T, Jones S, Horner R, Sugai G. School-wide positive behavior support and students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Implications for prevention, identification and intervention. Exceptionality. 2010; 18 :82–93. doi: 10.1080/09362831003673168. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Livingston MD, Rossheim ME, Stidham-Hall K. A descriptive analysis of school and school shooter characteristics and the severity of school shootings in the United States, 1999–2018. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019; 64 (6):797–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Losinski M, Katsiyannis A, Ryan J, Baughan C. Weapons in schools and zero-tolerance policies. NASSP Bulletin. 2014; 98 (2):126–141. doi: 10.1177/0192636514528747. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lowe SR, Galea S. The mental health consequences of mass shootings. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2017; 18 (1):62–82. doi: 10.1177/1524838015591572. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Association of School Psychologists. (n.d.). About PREPaRE. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/professional-development/prepare-training-curriculum/aboutprepare#:~:text=Specifically%2C%20the%20PREPaRE,E%E2%80%94Evaluate%20psychological%20trauma%20risk

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2015). Responding to school violence: Tips for administrators. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis/school-violence-resources/school-violence-prevention/responding-to-school-violence-tips-for-administrators

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2016). Talking to children about violence: Tips for parents and teachers. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis/school-violence-resources/talking-to-children-about-violence-tips-for-parents-and-teachers

- National Association of School Psychologists & National Association of School Resource Officers (2021). Best practice considerations for armed assailant drills in schools. Bethesda, MD: Author. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis/systems-level-prevention/best-practice-considerations-for-armed-assailant-drills-in-schools

- National Center for Learning Disabilities. (n.d.). What is RTI? Retrieved July 21, 2022 from http://www.rtinetwork.org/learn/what/whatisrti

- New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., Inc. v. Bruen, 20–843. (United States Supreme Court, 2021). Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-843_7j80.pdf

- Noltemeyer A, Palmer K, James AG, Wiechman S. School-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (SWPBIS): A synthesis of existing research. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. 2019; 7 :253–262. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2018.1425169. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research Center. (2022). What the data says about gun deaths in the U.S. Retrieved June 21, 2022 from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/02/03/what-the-data-says-about-gun-deaths-in-the-u-s/

- Puzzanchera, C. (2021). Juvenile arrests, 2019 . U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. Juvenile Justice Statistics National Report Series Bulletin. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/publications/juvenile-arrests-2019.pdf

- Roubein, R. (2022). Now the government is funding gun violence research, but it’s years behind. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2022 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/05/26/now-government-is-funding-gun-violence-research-it-years-behind/

- Rowhani-Rahbar A, Moe C. School shootings in the U.S.: What is the state of evidence? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019; 64 (6):683–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.016. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rumberger, R. W., & Losen, D. J. (2017). The hidden costs of California’s harsh school discipline: And the localized economic benefits from suspending fewer high school students . California Dropout Research Project : The Civil Rights Project. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/summary-reports/the-hidden-cost-of-californias-harsh-discipline/CostofSuspensionReportFinal-corrected-030917.pdf

- Sandoval, E. (2022). Inside a Uvalde classroom: A taunting gunman and 78 minutes of terror. The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/10/us/uvalde-injured-teacher-reyes.html

- Santiago-Rosario, M. R., McIntosh, K., & Payno-Simmons, R. (2022). Centering equity within the PBIS framework: Overview and evidence of effectiveness. Center on PBIS, University of Oregon. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from www.pbis.org

- Schonfeld DJ, Demaria T. Supporting children after school shootings. Pediatric Clinics. 2020; 67 (2):397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skiba RJ, Arredondo MI, Williams NT. More than a metaphor: The contribution of exclusionary discipline to a school-to-prison pipeline. Equity & Excellence in Education. 2014; 47 (4):546–564. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2014.958965. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Siegel LS. Early identification and intervention to prevent reading failure: A response to Intervention (RTI) initiative. Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2020; 37 (2):140–146. doi: 10.1017/edp.2020.21. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The Center for Public Integrity. (2021). When schools call police on kids. Retrieved June 21, 2022 from https://publicintegrity.org/education/criminalizing-kids/police-in-schools-disparities/

- Towers S, Gomez-Lievano A, Khan M, Mubayi A, Castillo-Chavez C. Contagion in mass killings and school shootings. PLoS One. 2015; 10 (7):e0117259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117259. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U. S. Department of Education. (2021). An overview of exclusionary discipline practices in public schools for the 2017–18 school year . Civil Rights Data Collection. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://ocrdata.ed.gov/estimations/2017-2018

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. (2020). 2017–18 civil rights data collection: The use of restraint and seclusion in children with disabilities in K-12 schools. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/restraint-and-seclusion.pdf

- U.S. General Accountability Office (2018). K-12 education: Discipline disparities for Black students, boys, and students with disabilities (GAO-18–258). Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-258

- Wan, W. (2019). Congressional deal could fund gun violence research for first time since 1990s. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 17, 2022 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/12/16/congressional-deal-could-fund-gun-violence-research-first-time-since-s/

- Wang, K., Chen, Y., Zhang, J., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2020). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2019 (NCES 2020–063/NCJ 254485). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved July 27, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020063-temp.pdf

- Washington Post. (2022). The Washington Post’s database of school shootings. Retrieved June 21, 2022 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/local/school-shootings-database/

Center for Gun Violence Solutions

- Make a Gift

- Stay Up-To-Date

- Research & Reports

Research Drives Solutions to Save Lives

We conduct rigorous research and use advocacy to implement evidence-based, equitable policies and programs that will prevent gun violence in our communities.

We don’t have to live with gun violence as a normal part of American life

Our team at the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions includes highly experienced researchers and public health-trained advocates to address gun violence as an epidemic-level public health emergency. Because gun violence disproportionately impacts communities of color, we ground our work in equity and seek insights from those most impacted on appropriate solutions.

This approach combines evidence-based solutions and effective advocacy to save lives.

Stay Up-To-Date with the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions

New at the center.

Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions and Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance Launch ERPO.org: A Hub for Extreme Risk Protection Order Resources

ERPO.org is a first-of-its-kind resource and represents a significant step forward in the national effort to prevent gun violence and promote public safety.

Study of Fatal and Nonfatal Shootings by Police Reveals Racial Disparities, Dispatch Risks

The analysis, thought to be one of the first published studies that captures both fatal and nonfatal injurious shootings by police nationally, also highlights risks of well-being checks.

A Year of Achievements and Our Vision for a Safer 2024

As we step into a new year at the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, it's crucial to reflect on the milestones achieved in 2023 and the work that lies ahead for a safer 2024.

Questions and Answers on Firearm Purchaser Licensing

Frequently asked questions about firearm purchaser licensing as new laws are considered in several states across the country.

Preventing Armed Insurrection: Firearms in Political Spaces Threaten Public Health, Safety, and Democracy

New report highlights recommendations and policies to help prevent political violence

Study Finds That Dropping Training Requirement to Obtain Concealed Carry Permit Leads to Significant Increase in Gun Assaults

Study comes as last year’s Bruen Supreme Court decision forces several states to loosen concealed carry permitting laws.

VIEW ALL ARTICLES

The Geography of Gun Violence

Gun death rates vary widely across the United States due to differences in socio-economic factors, demographics, and, importantly, gun policies. In general, the states with the highest gun death rates tend to be states in the South or Mountain West, with weaker gun laws and higher levels of gun ownership, while gun death rates are lower in the Northeast, where gun violence prevention laws are stronger.

* The total number of gun homicide deaths in New Hampshire and Vermont were less than 10 and thus repressed by CDC. Gun homicide deaths are thus listed as “other gun death rate” for these two states. Additionally, “other intents” include legal intervention, unintentional, and unclassified.

Follow the Center for Gun Violence Solutions on social media and share our latest content.

View this profile on Instagram Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions (@ jhu_cgvs ) • Instagram photos and videos

Support Our Work

Life-saving solutions exist. We can make gun violence rare and abnormal. Join us.

MAKE A GIFT

Defending Democracy: Addressing the Dangers of Armed Insurrection

The report, Defending Democracy: Addressing the Dangers of Armed Insurrection , recounts that the January 6 insurrection in 2021 at the U.S. Capitol was part of a long line of events in which individuals have sought to justify political violence or threats of violence by invoking false claims that the U.S. Constitution protects citizens’ rights to insurrection and the unchecked carrying of firearms in public. The report argues that armed insurrection can be prevented with effective policies and practices at the local, state, and national levels focused on protecting the integrity of the nation’s democratic processes.

Defending Democracy: How Policy Makers Can Protect Free and Fair Elections

Recent U.S. elections have been marked by threats, armed intimidation and political violence. As the 2024 U.S. general election approaches the Center hosted a webinar to discuss solutions against political violence and the threat of armed insurrection. Expert panelists discussed the implications of these threats to our country, public perception, and steps our leaders must take to protect our democratic institutions laid out in the Center's report "Defending Democracy".

Center for Gun Violence Solutions

We address gun violence as a public health emergency and utilize objective, non-partisan research to develop solutions which inform, fuel and propel advocacy to measurably lower gun violence. The Center applies our unique blend of research and advocacy to advance five priority evidence-based gun violence prevention policies . Our research shows that, when enacted in combination, these policies have the potential to save thousands of lives.

The Public Health Approach to Prevent Gun Violence

A public health approach to prevent gun violence addresses both firearm access and the factors that contribute to and protect from gun violence. This multidisciplinary approach brings together a range of experts across sectors—including researchers, advocates, legislators, impacted communities, community-based organizations, and others—in a common effort to develop and implement equitable, evidence-based solutions.

A Successful Example of the Public Health Approach

The public health approach to tackling public health crises in America has been used over the last century to eradicate diseases like polio, reduce smoking deaths, and make cars safer. This public health approach has saved millions of lives. We can learn from the public health successes — like car safety — and apply these lessons to preventing gun violence.

Sources: National Traffic Highway Safety Administration (NTHSA). Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities and Fatality Rates, 1899-2017; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1968-2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database.

One of the greatest American public health successes is our nation's work to make cars safer. To reduce gun violence, we should apply this same time-tested public health approach.

Quick Facts From 2022 CDC Provisional Data

In 2022, 48,117 people died by guns, an average of one person every 11 minutes. 26,993 people died by gun suicide in 2022. Provisional data shows gun deaths are up 21% since 2019. Overall, the gun death rate decreases, and the number of gun suicides reaches an all-time high.

In the past decade (2013-2022), the gun death rate among children & teens has increased 87%. Guns were the leading cause of death for children and teens (ages 1-19) in the U.S. for the fifth straight year. Both gun homicides and suicides fueled the increase.

Black children & teens were 20x as likely to die by firearm homicide compared to their white counterparts, in 2022. The gun suicide rate among Black children & teens (age 10-19) surpassed the rate among white children & teens (age 10-19) for the first time on record.

The Center recommends 5 evidence-based solutions to prevent gun death and injury: Firearm purchaser licensing, Extreme Risk Protection Orders and Domestic Violence Protection Orders, safe and secure firearm storage practices, strong laws limiting public carry, and community violence intervention programs.

Firearm Violence

For each firearm death, many more people are shot and survive their injuries, are shot at but not physically injured, or witness firearm violence. Many experience firearm violence in other ways, by living in impacted communities with high levels of violence, losing loved ones to firearm violence, or being threatened with a firearm. Others are fearful to walk in their neighborhoods, attend events, or send their child to school. In short, firearm violence is public health epidemic that has lasting impacts on the health and well-being of everyone on this country.

GO IN DEPTH

The Center Resources

Subscribe to the center newsletter.

Stay up-to-date on the latest in gun violence and gun violence prevention updates from the Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

The only newsroom dedicated to covering gun violence.

Ask The Trace

What Do You Want to Know About Gun Violence in America? Ask The Trace.

Go beyond the headlines.

Never miss a big story. subscribe now..

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Email a link to this page

Is there something that just doesn’t make sense to you when it comes to guns and gun violence in the United States? A statistic you’ve been searching for, but haven’t been able to locate? Information about why gun violence is more pervasive than in other countries? The history behind the gun laws we have (or don’t have)?

We had a lot of questions of our own when we started The Trace. Now we want to do a better job of understanding yours, and how we can help to answer them.

That’s why we’re reviving Ask The Trace, a special project driven by the curiosity of readers like you. The first iteration of this series explored a host of topics, from the relationship between mental illness and violence to the number of assault weapons in civilian hands . You can read all the articles from the series here.

Submit your questions using the form below. Our reporters and editors will review them and publish articles exploring the answers. Thanks for reading our work!

The only newsroom dedicated to reporting on gun violence.

Your tax-deductible donation to The Trace will directly support nonprofit journalism on gun violence and its effects on our communities.

Do Gun Regulations Equal Fewer Shootings? Lessons From New England

Gun rights advocates often point to low rates of shootings in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont to argue that you don’t need strong gun laws to keep violence in check. Here’s what the data actually reveals.

Why Are Gun Ads So Uncommon?

How often are ar-style rifles used for self-defense, do armed guards prevent school shootings.

July 5, 2022

What Researchers Know about Gun Policies’ Effectiveness

Studies are “decades behind,” owing to a lack of funding, but research is picking up

By Lynne Peeples & Nature magazine

Gun sales in the United States have been on the rise.

Jon Cherry/Bloomberg via Getty Images

About 40% of the world’s civilian-owned firearms are in the United States, a country that has had some 1.4 million gun deaths in the past four decades. And yet, until recently, there has been almost no federal funding for research that could inform gun policy.

US gun violence is back in the spotlight after mass shootings this May in Buffalo, New York, and Uvalde, Texas. And after a decades-long stalemate on gun controls in the US Congress, lawmakers passed a bipartisan bill that places some restrictions on guns. President Joe Biden signed it into law on 25 June.

The law, which includes measures to enhance background checks and allows review of mental-health records for young people wanting to buy guns, represents the most significant federal action on the issue in decades. Gun-control activists argue that the rules are too weak, whereas advocates of gun rights say there is no evidence that most gun policies will be effective in curbing the rate of firearm-related deaths.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The latter position is disingenuous, says Cassandra Crifasi, deputy director of the Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Although some evidence, both from the United States and overseas, supports the effectiveness of gun policies, many more studies are needed. “The fact that we have a lot of unanswered questions is intentional,” she says.

The reason, Crifasi says, is mid-1990s legislation that restricted federal funding for gun-violence research and was backed by the US gun lobby — organizations led by the National Rifle Association (NRA) that aim to influence policy on firearms. Lars Dalseide, a spokesperson for the NRA, responds that the association “did support the Dickey Amendment, which prohibited the CDC [US Centers for Disease Prevention and Control] from using taxpayer dollars to conduct research with an exclusive goal to further a political agenda — gun control.” But he adds that the association has “never opposed legitimate research for studies into the dynamics of violent crime”.

Only in the past few years — after other major mass shootings, including those at schools in Newtown, Connecticut, and Parkland, Florida — has the research field begun to rebuild , owing to an infusion of dollars and the loosening of limitations. “So, our field is much, much smaller than it should be compared to the magnitude of the problem,” Crifasi says. “And we are decades behind where we would be otherwise in terms of being able to answer questions.”

Now, scientists are working to take stock of the data they have and what data they’ll need to evaluate the success of the new legislation and potentially guide stronger future policies.

Among the reforms missing from the new US law, according to gun-safety researchers, is raising the purchasing age for an assault rifle to 21 years. Both the Buffalo and Uvalde gunmen bought their rifles legally at age 18. But making the case for minimum-age policies has been difficult because there are few data to back it up, Crifasi says. “With the limited research dollars available, people were not focusing on them as a research question.”

Gun-violence research is also stymied by gaps in basic data. For example, information on firearm ownership hasn’t been collected by the US government since the mid-2000s, a result of the Tiahrt Amendments. These provisions to a 2003 appropriations bill prohibit the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from releasing firearm-tracing data. For researchers, this means not knowing the total number of guns in any scenario they might be studying. “If we want to understand the rate at which guns become crime guns, or the rate at which guns are used in suicide, and which kind of guns and where, then we have to have that denominator,” says John Roman, a senior fellow at NORC, an independent research institution at the University of Chicago, Illinois.

Accurate counts of gun-violence events — the numerators needed to calculate those rates — are hard to come by, too. The CDC provides solid estimates of gun deaths, researchers note, but the agency hasn’t historically provided important context, such as the kind of weapon used or the relationship between the shooter and victim. Now fully funded, the state-based National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) is beginning to fill in those details. Still, it remains difficult for researchers to study changes over time.

What’s more, most shootings do not result in death, but still have negative impacts on the people involved and should be tracked. Yet CDC data on non-fatal firearm injuries are limited to imperfect summary statistics and are not included in the NVDRS. If researchers were better able to examine shootings beyond firearm deaths, they could have much greater statistical power to evaluate the effects of state and federal laws, Crifasi says. Without enough data, a study might conclude that a gun policy is ineffective even if it actually does have an impact on violence.

“The CDC strives to provide the most timely, accurate data available — including data related to firearm injuries,” says Catherine Strawn, a spokesperson for the agency.

Another complicating factor is that primary sources of gun-violence data — hospitals and police departments — issue statistics that are incomplete and incompatible. Hospitals frequently report intentional gunshot injuries as accidents. “Folks in the ER are not criminal investigators, and they default to saying things are accidents unless they absolutely know for certain that it was an intentional shooting,” Roman says.

Data on gun-related hospital care — which are collected under an agreement between the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, states and industry — can also be difficult for researchers to access. Some states charge for access to their data. “To get the complete set is incredibly expensive for researchers, so no one uses it,” says Andrew Morral, director of the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research at the RAND Corporation in Washington DC. “The federal government could do better at aggregating data and making it available for research.”