Problem of Sleep Deprivation Cause and Effect Essay

Introduction.

- What is Sleep Deprivation?

Causes of Sleep Deprivation

- Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Managing Sleep Deprivation

Works cited.

The functioning of the human body is influenced by a number of factors, which are mainly determined by the health status of an individual. Oftentimes, people seek medication when the body deviates from its normal and usual functioning mechanisms. Through different activities and processes, the body is able to use energy and replenish itself. Sleeping is one of the activities that has a direct effect on the functioning of the body.

This sleep deprivation essay explores how the functioning of the human body is influenced by various factors, primarily determined by an individual’s health status. While most people do not understand the implications of sleep, human effectiveness solely depends on the amount of time dedicated to sleeping. However, for various reasons, people fail to get enough sleep daily, weekly, or on a regular basis.

What Is Sleep Deprivation?

This cause and effect of sleep deprivation essay defines sleep deprivation as a condition occurring among human beings when they fail to get enough sleep. Sleep deprivation is defined as a condition that occurs when human beings fail to get enough sleep. Many experts argue that sleep deficiency is widespread even though most people do not consider it to be a serious issue, which affects their (Gaine et al.). Sleep deprivation has become a major problem in the United States, with almost 47 million suffering from the condition (Wang and Xiaomin). This lack of sleep can lead to a variety of physical and mental health issues, impacting daily functioning and quality of life.

The present essay about sleep deprivation defines sleep deprivation as a condition that occurs among human beings when they fail to get enough sleep. Many experts argue that sleep deficiency is widespread even though most people do not consider it to be a serious issue that affects their lives. Sleep deprivation has become a major problem in the United States, with almost forty-seven million suffering from the condition (Wang and Xiaomin). Among other reasons, one may get insufficient sleep in a day as a result of various factors. Some people sleep at the wrong time due to busy daily schedules, while others have sleep disorders, which affect their sleeping patterns. The following segment of the paper discusses the causes of deprivation.

Sleep deprivation may occur as a result of factors that are not known to the patients. This is based on the fact that sleep deprivation may go beyond the number of hours one spends in bed. In some cases, the quality of sleep matters in determining the level of deprivation.

In this context, it is possible for one to be in bed for more than eight hours but suffer from the negative effects of sleep deprivation. Whilst this is the case, there are people who wake every morning feeling tired despite having spent a recommended number of hours in bed (Griggs et al.14367).

Sleep deprivation can be caused by medical conditions, which may include but are not limited to asthma, arthritis, muscle cramps, allergies, and muscular pain. These conditions have been classified by researchers as common medical conditions that largely contribute to most of the cases of sleep deprivation being witnessed in the United States.

Similarly, these medical conditions have a direct impact on not only the quality but also the time one takes in bed sleeping. It is worth noting that sometimes people are usually unconscious to realize that their sleep is not deep enough (Wang and Xiaomin). This also explains the reason why it is not easy for a person to recall any moment in life when he or she moved closer to waking up.

Treatment of cases like sleep apnea is important because it affects the quality of sleep without necessarily awakening the victim. This is because medical surveys have revealed fatal effects of sleep apnea, especially on the cardiovascular system. Besides these, one is likely to experience breathing difficulties caused by insufficient oxygen.

Even though the treatment of sleep deprivation is important, it has been found that some drugs used to treat patients may worsen the case or lead to poor quality of sleep. It is, therefore, necessary for the doctor to determine the best drugs to use. Discussions between doctors and victims are imperative in order to understand patients’ responses (Conroy et al. 185).

Sleep deprivation is also caused by sleep cycle disruptions, which interfere with the fourth stage of sleep. Oftentimes, these disruptions are described as night terrors, sleepwalking, and nightmares.

Though these disorders are known not to awaken a person completely, it is vital to note that they may disrupt the order of sleep cycles, forcing a person to move from the fourth stage to the first one. Victims of these disruptions require attention in order to take corrective measures.

In addition, there are known environmental factors which contribute to several cases of sleep deprivation. However, doctors argue that the impact on the environment is sometimes too minimal to be recognized by people who are affected by sleep deficiency (Gaine et al.). In other words, these factors affect the quality of sleep without necessarily arousing a person from sleep.

Common examples include extreme weather conditions, like high temperatures, noise, and poor quality of the mattress. As a result, they may contribute to a person’s awakening, depending on the intensity when one is sleeping.

Moreover, the impact of these factors may develop with time, thus affecting one’s quality of sleep. In addition, most of the environmental factors that contribute to sleep deprivation can be fixed easily without medical or professional skills. Nevertheless, the challenge is usually how to become aware of their existence.

Lastly, sleep deprivation is caused by stress and depression, which have been linked to other health disorders and complications. Together with some lifestyles in America, these factors are heavily contributing to sleep deficiency in most parts of the world. Even though they might not be acute enough to awaken an individual, their cumulative effects usually become significant.

There are countless stressors in the world that affect youths and adults. While young people could be concerned with passing exams, adults are normally preoccupied with pressure to attain certain goals in life. These conditions create a disturbed mind, which may affect a person’s ability to enjoy quality sleep.

Sleep deprivation has a host of negative effects which affect people of all ages. The commonest effect is stress. Most people who suffer from sleep deficiency are likely to experience depression frequently as compared to their counterparts who enjoy quality sleep (Conroy et al. 188). As a result, stress may lead to poor performance among students at school.

Research has revealed that students who spend very few hours in bed or experience disruptions during sleep are likely to register poor performance in their class assignments and final exams. Additionally, sleep deprivation causes inefficiency among employees.

For instance, drivers who experience this disorder are more likely to cause accidents as compared to those who are free from it (Griggs et al.14367). This is based on the fact that un-refreshed people have poor concentration and low mastery of their skills.

Besides stress and anxiety, sleep deprivation has a wide-range of health-related effects. For instance, medical experts argue that people who spend less than six hours in bed are likely to suffer from high blood pressure. Quality sleep gives the body an opportunity to rest by slowing down the rate at which it pumps blood to the rest of the body (Wang and Xiaomin).

Inadequate sleep implies that the heart has to work without its normal and recommended rest. Additionally, sleep deprivation is known to affect the immune system. People who experience this disorder end up with a weakened immune system, leaving the body prone to most illnesses. This reduced immune response accumulates and may become fatal with time.

Sleep paralysis is also a common effect of inadequate sleep. This is due to disruption of the sleep cycle. It primarily occurs when the body is aroused during the fourth stage of the sleep cycle. In this case, the body is left immobile as the mind regains consciousness. Due to this conflict, one may experience pain and hallucinations.

Based on the negative effects of sleep deprivation, there is a need to manage this disorder among Americans. Firstly, it is necessary for people to seek medical advice concerning certain factors which could be contributing to this condition, like stress and infections (Wang and Xiaomin).

Proper counseling is also vital in stabilizing a person’s mental capacity. Physical exercises are also known to relieve a person from stressful conditions, contributing to sleep deficiency. Lastly, it is essential to ensure that the environment is free from noise and has regulated weather conditions.

Sleep deprivation remains a major problem in America, affecting millions of people. As discussed above, sleep deprivation is caused by a host of factors, ranging from environmental to health-related issues. Moreover, sleep deficiency has countless effects, most of which may become fatal in cases where the disorder is chronic.

Conroy, Deirdre A., et al. “ The Effects of COVID-19 Stay-at-home Order on Sleep, Health, and Working Patterns: A Survey Study of US Health Care Workers. ” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine , vol. 17, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 185–91.

Gaine, Marie E., et al. “ Altered Hippocampal Transcriptome Dynamics Following Sleep Deprivation. ” Molecular Brain, vol. 14, no. 1, Aug. 2021.

Griggs, Stephanie, et al. “ Socioeconomic Deprivation, Sleep Duration, and Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. ” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 21, Nov. 2022, p. 14367.

Wang, Jun, and Xiaomin Ren. “ Association Between Sleep Duration and Sleep Disorder Data From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and Stroke Among Adults in the United States .” Medical Science Monitor , vol. 28, June 2022.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 3). Problem of Sleep Deprivation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation/

"Problem of Sleep Deprivation." IvyPanda , 3 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Problem of Sleep Deprivation'. 3 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Problem of Sleep Deprivation." February 3, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Problem of Sleep Deprivation." February 3, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Problem of Sleep Deprivation." February 3, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation/.

- The Influence of Sleep Deprivation on Human Body

- Sleep Deprivation and Specific Emotions

- How Sleep Deprivation Affects College Students’ Academic Performance

- Sleep Deprivation and Learning at University

- Effects of Sleeping Disorders on Human

- Sleep Deprivation and Insomnia: Study Sources

- Sleep Deprivation: Biopsychology and Health Psychology

- The Issue of Chronic Sleep Deprivation

- Sleep Deprivation: Research Methods

- How the Brain Learns: Neuro-Scientific Research and Recent Discoveries

- Parkinson's Disease Treatment Approaches

- Concepts of Batten Disease

- Dyslexia: Definition, Causes, Characteristics

- How Dysphagia Disorder (Swallowing Disorder) is Caused in Parkinson’s Disease

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Among teens, sleep deprivation an epidemic

Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts.

October 8, 2015 - By Ruthann Richter

The most recent national poll shows that more than 87 percent of U.S. high school students get far less than the recommended eight to 10 hours of sleep each night. Christopher Silas Neal

Carolyn Walworth, 17, often reaches a breaking point around 11 p.m., when she collapses in tears. For 10 minutes or so, she just sits at her desk and cries, overwhelmed by unrelenting school demands. She is desperately tired and longs for sleep. But she knows she must move through it, because more assignments in physics, calculus or French await her. She finally crawls into bed around midnight or 12:30 a.m.

The next morning, she fights to stay awake in her first-period U.S. history class, which begins at 8:15. She is unable to focus on what’s being taught, and her mind drifts. “You feel tired and exhausted, but you think you just need to get through the day so you can go home and sleep,” said the Palo Alto, California, teen. But that night, she will have to try to catch up on what she missed in class. And the cycle begins again.

“It’s an insane system. … The whole essence of learning is lost,” she said.

Walworth is among a generation of teens growing up chronically sleep-deprived. According to a 2006 National Sleep Foundation poll, the organization’s most recent survey of teen sleep, more than 87 percent of high school students in the United States get far less than the recommended eight to 10 hours, and the amount of time they sleep is decreasing — a serious threat to their health, safety and academic success. Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts. It’s a problem that knows no economic boundaries.

While studies show that both adults and teens in industrialized nations are becoming more sleep deprived, the problem is most acute among teens, said Nanci Yuan , MD, director of the Stanford Children’s Health Sleep Center . In a detailed 2014 report, the American Academy of Pediatrics called the problem of tired teens a public health epidemic.

“I think high school is the real danger spot in terms of sleep deprivation,” said William Dement , MD, PhD, founder of the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic , the first of its kind in the world. “It’s a huge problem. What it means is that nobody performs at the level they could perform,” whether it’s in school, on the roadways, on the sports field or in terms of physical and emotional health.

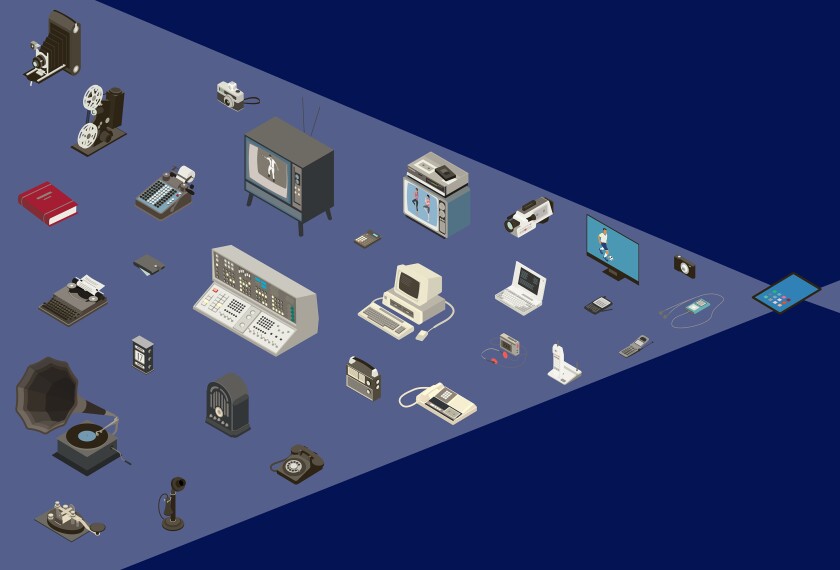

Social and cultural factors, as well as the advent of technology, all have collided with the biology of the adolescent to prevent teens from getting enough rest. Since the early 1990s, it’s been established that teens have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later — as much as two hours later — than their younger counterparts.

Yet when they enter their high school years, they find themselves at schools that typically start the day at a relatively early hour. So their time for sleep is compressed, and many are jolted out of bed before they are physically or mentally ready. In the process, they not only lose precious hours of rest, but their natural rhythm is disrupted, as they are being robbed of the dream-rich, rapid-eye-movement stage of sleep, some of the deepest, most productive sleep time, said pediatric sleep specialist Rafael Pelayo , MD, with the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic.

“When teens wake up earlier, it cuts off their dreams,” said Pelayo, a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “We’re not giving them a chance to dream.”

Teens have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later, yet many high schools start the day at a relatively early hour, disrupting their natural rhythym. Monkey Business/Fotolia

Understanding teen sleep

On a sunny June afternoon, Dement maneuvered his golf cart, nicknamed the Sleep and Dreams Shuttle, through the Stanford University campus to Jerry House, a sprawling, Mediterranean-style dormitory where he and his colleagues conducted some of the early, seminal work on sleep, including teen sleep.

Beginning in 1975, the researchers recruited a few dozen local youngsters between the ages of 10 and 12 who were willing to participate in a unique sleep camp. During the day, the young volunteers would play volleyball in the backyard, which faces a now-barren Lake Lagunita, all the while sporting a nest of electrodes on their heads.

At night, they dozed in a dorm while researchers in a nearby room monitored their brain waves on 6-foot electroencephalogram machines, old-fashioned polygraphs that spit out wave patterns of their sleep.

One of Dement’s colleagues at the time was Mary Carskadon, PhD, then a graduate student at Stanford. They studied the youngsters over the course of several summers, observing their sleep habits as they entered puberty and beyond.

Dement and Carskadon had expected to find that as the participants grew older, they would need less sleep. But to their surprise, their sleep needs remained the same — roughly nine hours a night — through their teen years. “We thought, ‘Oh, wow, this is interesting,’” said Carskadon, now a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University and a nationally recognized expert on teen sleep.

Moreover, the researchers made a number of other key observations that would plant the seed for what is now accepted dogma in the sleep field. For one, they noticed that when older adolescents were restricted to just five hours of sleep a night, they would become progressively sleepier during the course of the week. The loss was cumulative, accounting for what is now commonly known as sleep debt.

“The concept of sleep debt had yet to be developed,” said Dement, the Lowell W. and Josephine Q. Berry Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. It’s since become the basis for his ongoing campaign against drowsy driving among adults and teens. “That’s why you have these terrible accidents on the road,” he said. “People carry a large sleep debt, which they don’t understand and cannot evaluate.”

The researchers also noticed that as the kids got older, they were naturally inclined to go to bed later. By the early 1990s, Carskadon established what has become a widely recognized phenomenon — that teens experience a so-called sleep-phase delay. Their circadian rhythm — their internal biological clock — shifts to a later time, making it more difficult for them to fall asleep before 11 p.m.

Teens are also biologically disposed to a later sleep time because of a shift in the system that governs the natural sleep-wake cycle. Among older teens, the push to fall asleep builds more slowly during the day, signaling them to be more alert in the evening.

“It’s as if the brain is giving them permission, or making it easier, to stay awake longer,” Carskadon said. “So you add that to the phase delay, and it’s hard to fight against it.”

Pressures not to sleep

After an evening with four or five hours of homework, Walworth turns to her cellphone for relief. She texts or talks to friends and surfs the Web. “It’s nice to stay up and talk to your friends or watch a funny YouTube video,” she said. “There are plenty of online distractions.”

While teens are biologically programmed to stay up late, many social and cultural forces further limit their time for sleep. For one, the pressure on teens to succeed is intense, and they must compete with a growing number of peers for college slots that have largely remained constant. In high-achieving communities like Palo Alto, that translates into students who are overwhelmed by additional homework for Advanced Placement classes, outside activities such as sports or social service projects, and in some cases, part-time jobs, as well as peer, parental and community pressures to excel.

William Dement

At the same time, today’s teens are maturing in an era of ubiquitous electronic media, and they are fervent participants. Some 92 percent of U.S. teens have smartphones, and 24 percent report being online “constantly,” according to a 2015 report by the Pew Research Center. Teens have access to multiple electronic devices they use simultaneously, often at night. Some 72 percent bring cellphones into their bedrooms and use them when they are trying to go to sleep, and 28 percent leave their phones on while sleeping, only to be awakened at night by texts, calls or emails, according to a 2011 National Sleep Foundation poll on electronic use. In addition, some 64 percent use electronic music devices, 60 percent use laptops and 23 percent play video games in the hour before they went to sleep, the poll found. More than half reported texting in the hour before they went to sleep, and these media fans were less likely to report getting a good night’s sleep and feeling refreshed in the morning. They were also more likely to drive when drowsy, the poll found.

The problem of sleep-phase delay is exacerbated when teens are exposed late at night to lit screens, which send a message via the retina to the portion of the brain that controls the body’s circadian clock. The message: It’s not nighttime yet.

Yuan, a clinical associate professor of pediatrics, said she routinely sees young patients in her clinic who fall asleep at night with cellphones in hand.

“With academic demands and extracurricular activities, the kids are going nonstop until they fall asleep exhausted at night. There is not an emphasis on the importance of sleep, as there is with nutrition and exercise,” she said. “They say they are tired, but they don’t realize they are actually sleep-deprived. And if you ask kids to remove an activity, they would rather not. They would rather give up sleep than an activity.”

The role of parents

Adolescents are also entering a period in which they are striving for autonomy and want to make their own decisions, including when to go to sleep. But studies suggest adolescents do better in terms of mood and fatigue levels if parents set the bedtime — and choose a time that is realistic for the child’s needs. According to a 2010 study published in the journal Sleep , children are more likely to be depressed and to entertain thoughts of suicide if a parent sets a late bedtime of midnight or beyond.

In families where parents set the time for sleep, the teens’ happier, better-rested state “may be a sign of an organized family life, not simply a matter of bedtime,” Carskadon said. “On the other hand, the growing child and growing teens still benefit from someone who will help set the structure for their lives. And they aren’t good at making good decisions.”

They say they are tired, but they don’t realize they are actually sleep-deprived. And if you ask kids to remove an activity, they would rather not. They would rather give up sleep than an activity.

According to the 2011 sleep poll, by the time U.S. students reach their senior year in high school, they are sleeping an average of 6.9 hours a night, down from an average of 8.4 hours in the sixth grade. The poll included teens from across the country from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

American teens aren’t the worst off when it comes to sleep, however; South Korean adolescents have that distinction, sleeping on average 4.9 hours a night, according to a 2012 study in Sleep by South Korean researchers. These Asian teens routinely begin school between 7 and 8:30 a.m., and most sign up for additional evening classes that may keep them up as late as midnight. South Korean adolescents also have relatively high suicide rates (10.7 per 100,000 a year), and the researchers speculate that chronic sleep deprivation is a contributor to this disturbing phenomenon.

By contrast, Australian teens are among those who do particularly well when it comes to sleep time, averaging about nine hours a night, possibly because schools there usually start later.

Regardless of where they live, most teens follow a pattern of sleeping less during the week and sleeping in on the weekends to compensate. But many accumulate such a backlog of sleep debt that they don’t sufficiently recover on the weekend and still wake up fatigued when Monday comes around.

Moreover, the shifting sleep patterns on the weekend — late nights with friends, followed by late mornings in bed — are out of sync with their weekday rhythm. Carskadon refers to this as “social jet lag.”

“Every day we teach our internal circadian timing system what time it is — is it day or night? — and if that message is substantially different every day, then the clock isn’t able to set things appropriately in motion,” she said. “In the last few years, we have learned there is a master clock in the brain, but there are other clocks in other organs, like liver or kidneys or lungs, so the master clock is the coxswain, trying to get everybody to work together to improve efficiency and health. So if the coxswain is changing the pace, all the crew become disorganized and don’t function well.”

This disrupted rhythm, as well as the shortage of sleep, can have far-reaching effects on adolescent health and well-being, she said.

“It certainly plays into learning and memory. It plays into appetite and metabolism and weight gain. It plays into mood and emotion, which are already heightened at that age. It also plays into risk behaviors — taking risks while driving, taking risks with substances, taking risks maybe with sexual activity. So the more we look outside, the more we’re learning about the core role that sleep plays,” Carskadon said.

Many studies show students who sleep less suffer academically, as chronic sleep loss impairs the ability to remember, concentrate, think abstractly and solve problems. In one of many studies on sleep and academic performance, Carskadon and her colleagues surveyed 3,000 high school students and found that those with higher grades reported sleeping more, going to bed earlier on school nights and sleeping in less on weekends than students who had lower grades.

Sleep is believed to reinforce learning and memory, with studies showing that people perform better on mental tasks when they are well-rested. “We hypothesize that when teens sleep, the brain is going through processes of consolidation — learning of experiences or making memories,” Yuan said. “It’s like your brain is filtering itself — consolidating the important things and filtering out those unimportant things.” When the brain is deprived of that opportunity, cognitive function suffers, along with the capacity to learn.

“It impacts academic performance. It’s harder to take tests and answer questions if you are sleep-deprived,” she said.

That’s why cramming, at the expense of sleep, is counterproductive, said Pelayo, who advises students: Don’t lose sleep to study, or you’ll lose out in the end.

The panic attack

Chloe Mauvais, 16, hit her breaking point at the end of a very challenging sophomore year when she reached “the depths of frustration and anxiety.” After months of late nights spent studying to keep up with academic demands, she suffered a panic attack one evening at home.

“I sat in the living room in our house on the ground, crying and having horrible breathing problems,” said the senior at Menlo-Atherton High School. “It was so scary. I think it was from the accumulated stress, the fear over my grades, the lack of sleep and the crushing sense of responsibility. High school is a very hard place to be.”

We hypothesize that when teens sleep, the brain is going through processes of consolidation — learning of experiences or making memories. It’s like your brain is filtering itself.

Where she once had good sleep habits, she had drifted into an unhealthy pattern of staying up late, sometimes until 3 a.m., researching and writing papers for her AP European history class and prepping for tests.

“I have difficulty remembering events of that year, and I think it’s because I didn’t get enough sleep,” she said. “The lack of sleep rendered me emotionally useless. I couldn’t address the stress because I had no coherent thoughts. I couldn’t step back and have perspective. … You could probably talk to any teen and find they reach their breaking point. You’ve pushed yourself so much and not slept enough and you just lose it.”

The experience was a kind of wake-up call, as she recognized the need to return to a more balanced life and a better sleep pattern, she said. But for some teens, this toxic mix of sleep deprivation, stress and anxiety, together with other external pressures, can tip their thinking toward dire solutions.

Research has shown that sleep problems among adolescents are a major risk factor for suicidal thoughts and death by suicide, which ranks as the third-leading cause of fatalities among 15- to 24-year-olds. And this link between sleep and suicidal thoughts remains strong, independent of whether the teen is depressed or has drug and alcohol issues, according to some studies.

“Sleep, especially deep sleep, is like a balm for the brain,” said Shashank Joshi, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford. “The better your sleep, the more clearly you can think while awake, and it may enable you to seek help when a problem arises. You have your faculties with you. You may think, ‘I have 16 things to do, but I know where to start.’ Sleep deprivation can make it hard to remember what you need to do for your busy teen life. It takes away the support, the infrastructure.”

Sleep is believed to help regulate emotions, and its deprivation is an underlying component of many mood disorders, such as anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder. For students who are prone to these disorders, better sleep can help serve as a buffer and help prevent a downhill slide, Joshi said.

Rebecca Bernert, PhD, who directs the Suicide Prevention Research Lab at Stanford, said sleep may affect the way in which teens process emotions. Her work with civilians and military veterans indicates that lack of sleep can make people more receptive to negative emotional information, which they might shrug off if they were fully rested, she said.

“Based on prior research, we have theorized that sleep disturbances may result in difficulty regulating emotional information, and this may lower the threshold for suicidal behaviors among at-risk individuals,” said Bernert, an instructor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. Now she’s studying whether a brief nondrug treatment for insomnia reduces depression and risk for suicide.

Sleep deprivation also has been shown to lower inhibitions among both adults and teens. In the teen brain, the frontal lobe, which helps restrain impulsivity, isn’t fully developed, so teens are naturally prone to impulsive behavior. “When you throw into the mix sleep deprivation, which can also be disinhibiting, mood problems and the normal impulsivity of adolescence, then you have a potentially dangerous situation,” Joshi said.

Some schools shift

Given the health risks associated with sleep problems, school districts around the country have been looking at one issue over which they have some control: when school starts in the morning. The trend was set by the town of Edina, Minnesota, a well-to-do suburb of Minneapolis, which conducted a landmark experiment in student sleep in the late 1990s. It shifted the high school’s start time from 7:20 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. and then asked University of Minnesota researchers to look at the impact of the change. The researchers found some surprising results: Students reported feeling less depressed and less sleepy during the day and more empowered to succeed. There was no comparable improvement in student well-being in surrounding school districts where start times remained the same.

With these findings in hand, the entire Minneapolis Public School District shifted start times for 57,000 students at all of its schools in 1997 and found similarly positive results. Attendance rates rose, and students reported getting an hour’s more sleep each school night — or a total of five more hours of sleep a week — countering skeptics who argued that the students would respond by just going to bed later.

For the health and well-being of the nation, we should all be taking better care of our sleep, and we certainly should be taking better care of the sleep of our youth.

Other studies have reinforced the link between later start times and positive health benefits. One 2010 study at an independent high school in Rhode Island found that after delaying the start time by just 30 minutes, students slept more and showed significant improvements in alertness and mood. And a 2014 study in two counties in Virginia found that teens were much less likely to be involved in car crashes in a county where start times were later, compared with a county with an earlier start time.

Bolstered by the evidence, the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2014 issued a strong policy statement encouraging middle and high school districts across the country to start school no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to help preserve the health of the nation’s youth. Some districts have heeded the call, though the decisions have been hugely contentious, as many consider school schedules sacrosanct and cite practical issues, such as bus schedules, as obstacles.

In Fairfax County, Virginia, it took a decade of debate before the school board voted in 2014 to push back the opening school bell for its 57,000 students. And in Palo Alto, where a recent cluster of suicides has caused much communitywide soul-searching, the district superintendent issued a decision in the spring, over the strenuous objections of some teachers, students and administrators, to eliminate “zero period” for academic classes — an optional period that begins at 7:20 a.m. and is generally offered for advanced studies.

Certainly, changing school start times is only part of the solution, experts say. More widespread education about sleep and more resources for students are needed. Parents and teachers need to trim back their expectations and minimize pressures that interfere with teen sleep. And there needs to be a cultural shift, including a move to discourage late-night use of electronic devices, to help youngsters gain much-needed rest.

“At some point, we are going to have to confront this as a society,” Carskadon said. “For the health and well-being of the nation, we should all be taking better care of our sleep, and we certainly should be taking better care of the sleep of our youth.”

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Artificial intelligence

Exploring ways AI is applied to health care

- 2021-25 Strategic Plan

- President's Message

- Diversity Initiatives

- Annual Report

- 2019 Leadership Institute

- 2018 Leadership Institute

- 2017 Leadership Institute

- 2016 Leadership Institute

- Monica Baskin Diversity Institute for Emerging Leaders

- Early Career Researcher Mentoring Program

- Sci Comm Toolkit

- Fellow Criteria

- Affiliate Membership

- Reach Your Target Audience with SBM

- Virginia Commonwealth University: Postdoctoral Fellow

- Cancer Health Equity & Career Development Program: Post-doctoral & Predoctoral Research Fellowships

- University of Kansas Medical Center: Professor- Population Health (Implementation Science)

- University of Alabama at Birmingham: Strategic Recruitment in Addiction and Pain

- University of Virginia: Postdoctoral Associate Position

- University of Mississippi Medical Center: Open Rank Faculty

- University of Vermont Cancer Center: Health Services and Cancer Research Position

- Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey: Pediatric Population Scientist

- Brown University: Postdoctoral Research Associate

- Baylor University: Postdoctoral Research Associate

- University of Virginia: Research Specialist Intermediate

- University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences: Chair, Health Behavior and Health Education

- The University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center: Faculty (Open Rank)

- University of South Carolina: DEAN OF THE ARNOLD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

- University of Illinois at Chicago: Open-Rank, Tenure-Track Position Exercise Physiology

- University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health: Professor or Associate Professor

- Dartmouth Health: Senior Clinician Investigator in Intervention, Services Delivery

- Open Rank Faculty Positions in Public Health Sciences

- Assistant/Associate Professor, Department of Kinesiology

- Senior Research Leader, Associate or Full Professor, Tenure Track Regular Title Series

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Child and Family Health

- Climate Change and Health

- Digital Health

- Evidence-Based Behavioral Medicine

- Health Decision Making and Communication

- Health Equity

- HIV and Sexual Health

- Integrated Primary Care

- Integrative Health and Spirituality

- Military and Veterans' Health

- Multiple Health Behavior Change and Multi-Morbidities

- Obesity and Eating Disorders

- Optimization of Behavioral and Biobehavioral Interventions

- Palliative Care

- Physical Activity

- Population Health Sciences

- Theories and Techniques of Behavior Change Interventions

- Violence and Trauma

- Women's Health

- Consultation Program

- Sign-Ons and Endorsements

- Annals of Behavioral Medicine

- Translational Behavioral Medicine

- Awards and Inclusions

- The Buzz in Behavioral Medicine

- Healthy Living

- Stride for Science 5k

- Bridging the Gap Research Award Recipients

- Sustaining Donor Club

- Battle of the SIGs

- Industry Partners

Quick Links

- Annual Meeting

- Terms of Use

SBM Members

- Login & Security

Connect with us

Sleep Better, Feel Better: Preventing Sleep Deprivation in College Students

Benjamin T. Ladd, BA, The Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center, The Miriam Hospital; and Carly M. Goldstein, PhD FAACVPR, The Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University

Though many people struggle to fall or stay asleep, college students are particularly vulnerable to environment-driven sleep deprivation. As many as 60% of undergraduates have poor sleep quality and 25% experience insomnia symptoms.

Decreased sleep increases vulnerability to problematic health behaviors including decreased exercise, poor eating habits, and smoking. Fortunately, you can improve your sleep quality with a few proven strategies.

Preventing Sleep Deprivation as a College Student

Manage nighttime noise..

College students living in communal living spaces face challenges like noisy neighbors. Assertively communicate with others in your space about limiting noise around bedtime. Earplugs, noise-cancelling headphones, a loud fan, or a white noise machine can block out disruptive nighttime sounds. As a last resort, try reaching out to the residential life office at your school.

Keep your surroundings cool and dark.

The optimal sleep temperature is between 60-67 degrees Fahrenheit. Turn down your thermostat before bed or open a window. You can also try cooling pillows and bedding. Minimize ambient light in your sleep space by using blackout curtains or a sleep mask.

Try to address anxiety during the daytime.

Anxious people sleep less and spend less time in REM sleep, leading to difficulties concentrating, daytime sleepiness, and poor memory. Schedule and plan your many commitments. Engage in meaningful activities that you enjoy, especially ones that are just for fun.

When we are stressed and anxious, we tend to cut out the fun activities first. Fun and joyful activities are central to maintaining your mental health. Similarly, continue to invest in your relationships with family and friends. A strong support network can help you tackle stressful events and get through difficult periods of your life. Remember that the people in your life care about you and want to help.

Try to incorporate exercise into your week and consider therapy. Your university may have resources available for no- or low-cost support.

Finally, when anxious thoughts run through your head in bed, try writing them down and quickly laying back down to sleep. Get in the habit of telling yourself that you will deal with those issues tomorrow. This can be difficult at first but can be learned with practice.

Meditate before bedtime.

You can do this on your own or through an app. Individuals who engage in nighttime mindfulness have fewer insomnia symptoms and less anxiety, stress, depression, and daytime fatigue interference and severity. These improvements exceed those when practicing sleep hygiene alone. Consider joining a meditation club at your college to build and support the habit.

Maintain a regular nighttime sleep schedule.

Try to be in bed at the same time each night and set your alarm for the same time each morning; fight the urge to sleep in! Waking at the same time every morning, even on weekends, establishes a regular sleep rhythm.

Your schedule may vary significantly, posing a challenge for maintaining a consistent sleep schedule. For sleep purposes, it may hurt your sleep to wake up for class at 7 am one day each week and wake up much later every other day. In this case, try to wake up early every day. Use that morning time to exercise, meditate, do homework, or engage in a meaningful hobby.

Avoid doing homework directly before bedtime. Instead, develop a consistent and short routine before bed that helps you wind down, like reading a book, meditating, or listening to relaxing music. Avoid screens because the blue light waves from the screen may inhibit production of melatonin, the hormone that induces sleep.

Moderate or reduce alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana, especially around bedtime.

Alcohol can reduce sleep duration, time spent in REM sleep, and sleep schedule variability. Many college students use marijuana to fall asleep. This often results in reduced time spent in REM sleep causing worse sleep efficiency, daytime sleepiness and dysfunction, and negatively affects academic performance.

If you use nicotine, avoid nicotine-based substances 4 hours before bedtime. Nicotine has stimulant properties that are associated with sleep disruptions and disorders.

Reduce and be strategic about naps.

If you nap, aim for 20-30 minutes before 2pm. To fall asleep, your body uses a circadian rhythm (knowing day versus night) and sleep pressure, which builds throughout the day. Napping midday reduces sleep pressure, so nap early enough that your body has time to build up your sleep pressure again before bedtime. Remember that there are alternatives to naps, such as exercise or resting in a quiet place.

If nothing works after lying in bed for 20 minutes, don’t force the issue. Get out of bed and do a quiet, relaxing screen-free activity, and only return to bed when you can’t resist falling asleep.

If these strategies don’t work for you, seek out a behavioral sleep medicine specialist (a psychologist who specializes in sleep), a health psychologist, a board-certified sleep medicine doctor, or your primary care provider for more guidance or targeted interventions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is an evidence-based technique used to effectively address sleep-related issues. Evidence-based workbooks are also a great option that can work well such as this option or this one .

Before that, try 1 or 2 of the above tips and see how it affects your sleep. While some of these habits can be difficult to start, they’re a great way to take charge of your sleep and improve your well-being.

More Articles

How Can Primary Care Teams Address Insomnia in the Context of Persistent Pain?

Insomnia can be caused be a number of medical conditions, including chronic pain. Learn how behavioral health professionals can help treat insomnia without sleep medication.

Insomnia in Older Adults: Tips to Master Sleep as We Age

How we sleep and how we can sleep better changes as we age. Check out these tips for older adults with poor sleep or insomnia.

Helping Kids Get the Sleep They Need

Parents often worry that their children are not getting enough sleep and busy schedules make it hard to prioritize sleep. Luckily, there are many strategies that parents can use to help their kid sleep.

« Back to Healthy Living

- STFM Journals

- Family Medicine

- Annals of Family Medicine

- About PRiMER

LEARNER RESEARCH

An educational intervention to improve the sleep behavior and well-being of high school students, alexandra colt, ba | jo marie reilly, md, mph.

PRiMER. 2019;3:21.

Published: 9/26/2019 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2019.871017

Objective: The objective of this study was to determine whether a sleep education intervention improves knowledge of sleep, sleep behaviors, and depression in high school freshmen.

Methods: We recruited student volunteers at a single magnet high school in Los Angeles, California through their health class. Twenty-four freshmen participated and 18 students (17 female, 1 male) completed pre- and postsurveys. Curriculum consisted of 4 hours of after-school interactive lectures emphasizing sleep physiology, benefits of sleep, what impacts sleep, and methods to improve sleep, followed by a 9-week sleep behavior change journal. Pre- and postsurveys measuring both sleep behaviors and knowledge, and a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression screening were administered to participants prior to and after the intervention. We used t tests and χ 2 tests to analyze knowledge and behavior change.

Results: Subjects improved in average sleep hours per night (preintervention 6.9 hours to postintervention 7.8 hours, P =.0134), and average weekend night bedtime (11:36 pm to 10:54 pm, P =.0307).

Conclusions: This school sleep behavior intervention demonstrated students’ average sleep hours per night and weekend bedtime improved after the lecture and sleep journal intervention. This suggests a sleep education intervention may benefit this population. Further studies are needed to demonstrate effectiveness of this education over time, across sexes, and in high-risk students.

Introduction

Teenage students, especially those in competitive academics, are at risk for sleep deprivation. 1 This can harm health, mood, and academics. 2 The current recommendation from the National Sleep Foundation is 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night for adolescents. 3 Further, adolescents’ melatonin—the “sleep hormone”—often does not release until late at night and peaks in the early morning. 4 This causes them to be more awake later in the day and more tired when they need to get up for school. The shift in circadian rhythm makes it difficult for teens to adapt their sleep schedule to a normal school day and to get the recommended 8-10 hours of sleep per night. The biological change in sleep, coupled with academic pressure to get homework done, often influences students to stay up later. The net effect is that students are sleepy at school. 1 Weekend catch-up sleep is problematic, too, as it forces adolescents out of their circadian rhythm. 5

In addition to considering the biological and schedule factors that impact adolescent sleep, it is also important to consider the impacts of bedtime autonomy, caffeine, physical activity, friends, homework, electronics, noise, and responsibilities at home. Researchers in the field of adolescent sleep have highlighted the importance of sleep education and encouragement to make healthy sleep choices, 6,7 especially regarding electronics usage that cause sleep difficulties. Additionally, electronics usage has been linked to depressive symptoms. 8

The sleep deficit in this population is significant enough that the United States government initiative, Healthy People 2020, includes “increase the proportion of students in grades 9 through 12 who get sufficient sleep” as one of its four sleep health objectives. Healthy People 2020 reports that in 2009, only 30.9% of students in these grades got sufficient sleep. 9 As screen time has suddenly increased and the duration of other distracting behaviors has remained relatively stable, the percentage of adolescents sleeping 7 hours per night or less has also increased, suggesting an impact of electronics usage on sleep behaviors. 10,11

Although this population often has knowledge of the importance of sleep, they are still sleep deprived, due to lack of knowledge of sleep-improving tactics and corresponding sleep-preserving behaviors. Sleep also determines whether electronics usage affects depression in this age group as electronics usage only correlates with depression when subjects are also low on sleep or have problems sleeping 12 ; and s leep problems from adolescence have been found to persist into adulthood, 13 highlighting the need for early intervention in sleep education.

Lack of sleep had been identified by students as a problem at Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School by after-school program leaders. In response, a course was created to educate students about sleep behavior and physiology. We hypothesized that after an educational sleep intervention, subjects would report increased sleep time per night, decreased depression, 14 and improved knowledge regarding sleep behavior and physiology.

The institutional review board at the University of Southern California approved this study (HS-16-00715), and parents/guardians provided consent using a standard consent form in English and Spanish.

The assistant principal at Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet School in Los Angeles, California recruited high school freshmen through their freshman health class. Student participants were given community service hour credit for each hour of participation; these hours are required for graduation. Freshmen were chosen so the intervention could have the longest possible impact on their high school careers. Twenty-four subjects participated in the intervention, and 18 completed the presurvey, lecture, journal, and postsurvey and were included in the data analysis. The average age of participants was 14 years.

Sleep Intervention

The sleep intervention consisted of one 2-hour and two 1-hour after-school courses created and taught by the principal investigator. The curriculum was designed to teach subjects about sleep physiology and its importance, its impact on health, and methods to improve sleep hygiene and sleep behaviors. The teaching consisted of interactive lectures with PowerPoint slides. The first 2-hour class included information about basic sleep physiology (ie, functions of melatonin, caffeine, neurotransmitters) and sleep recommendations by age. 15 At the end of the first class, subjects were asked to write down what they would like to learn in the course, and their answers were the focus of the second class.

Topics for the second module included strategies for time management, sleeping through the night, sleeping when not tired, and sleeping more hours. 16 Between the second and third class, the subjects were given sleep behavior change journals to complete over 9 weeks. The sleep behavior change journal asked subjects to record how many hours they slept each night. It also asked them to set a personal behavior change goal and write each week about how they adhered to their goal, what made it difficult, what they could do to improve, and what their mood was like that week. Suggestions of goals for subjects to choose included (1) keep a sleep schedule (same time to bed and to awaken), (2) do something relaxing (nonelectronic, eg, reading or meditation) before bed, (3) turn off electronics 1 hour before bed, (4) exercise regularly, (5) avoid caffeine, (6) make room darker and temperature cooler, and (7) keep the bed just for sleep. 17 Subjects were also asked to compare their sleep behavior to that of the previous weeks and note any changes they had made. The course and journal times and durations were selected to best match the school’s and subjects’ schedules.

Survey Instrument

We used a pre- and postintervention sleep survey to record students’ sleep behavior. 18 The survey asked about sleep hours per night, school night and weekend night bed times, reasons for not sleeping more, hours spent on homework, sleep and wake aids, whether there was competition regarding sleep among friends and at school, whether subjects and their families thought they slept enough, use of technology prior to bedtime, and whether they were worried about their sleep. These topics were included to gather basic sleep statistics about the cohort and to assess students' basic knowledge about sleep hygiene pre- and postintervention.

The pre- and postsurveys also evaluated students’ knowledge about adolescent sleep behavior and physiology. These questions asked about (1) how many hours teenagers should sleep, (2) how sleep affects academic performance, risk-taking, obesity, mood, and caffeine intake, (3) electronics usage, (4) food consumption and physical activity, and (5) depression and anxiety and their impact on sleep. The preintervention survey also asked what subjects would like to see included in the course. The postintervention survey asked if subjects believed the course would affect their long-term behavior, what did and did not work about the course, what they would like to see changed in future iterations of the course, and the top three things they learned from the course. The survey instrument included a depression screening (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9], a validated depression screening instrument).

Statistical Analysis

The principal investigator collected and analyzed all data and was blinded to subject survey responses. Of the 24 subjects recruited, 18 (17 female, 1 male) completed the preintervention survey, lecture, journal, and postintervention survey and were included in the data analysis. The remining six students were unable to complete all parts of the course due to scheduling conflicts. We used t tests and χ 2 tests to analyze pre- to posttest change.

Sleep Behavior Change

Subjects reported an increase in average sleep hours per school night (preintervention 6.9 hours to postintervention 7.8 hours, P =.0134; Figure 1, with 50% of students reporting an increase in average hours slept per night) and in average weekend night bedtime (11:36pm to 10:54pm, P =.0307; Figure 2, with 44% of students reporting an earlier average bedtime).

There was no statistically significant pre- to postintervention change in night-before-survey sleep hours, school night bedtime, weekend sleep hours, school night homework hours, or sleep hours desired.

In a postintervention discussion led by the principal investigator, the cohort also reported increased use of a consistent bedtime, both on school and weekend nights, a key teaching point. There was an increase—although not statistically significant—in the proportion of subjects who thought they slept enough before the course: 33% (6 subjects), compared to the proportion of subjects 61% (11) who thought so after course completion. At the end of the course, 89% (16) thought the course would affect their long-term sleep behavior.

Sleep Knowledge

The understanding of the number of hours teenagers should sleep (8-10 hours per night) decreased, as the number of students who corretly answered the multiple-choice question about the number of hours teenagers should sleep (8-10 per night) decreased (13 to 7, P =.0442).

There was no statistically significant change pre- to postintervention in the percentage of correct multiple-choice answers to the following survey questions 18 : (1) How does sleep affect academic performance? (2) How does sleep time affect risk-taking behavior? (3) How does sleep time affect obesity? (4) How does caffeine affect sleep? (5) How does using technology affect sleep? (6) How does food affect sleep? (7) How does physical activity affect sleep? (8) How does depressed or anxious mood affect sleep? (9) How does sleep affect mood?

Those who scored ≥10 (moderate or more severe depression) on the PHQ-9, or indicated suicidal ideation, were reidentified and referred to the school psychologist for immediate mental health intervention (six subjects preintervention, two subjects postintervention). PHQ-9 scores decreased over the course of the intervention, but not in a statistically significant way. The change in percentage of subjects with moderate or more severe depression preintervention to postintervention decreased, but was not statistically significant either.

Adolescent sleep hygiene is an area of importance to health care providers, as it impacts adolescent health, well-being, and academic performance. Developing tools that can improve sleep hygiene is important to improving the overall well-being of this population. This pilot study used a sleep behavior and physiology course and a sleep journal in an effort to improve adolescent sleep knowledge, behavior, and overall well-being. Enrolled subjects were interested in learning about and improving their sleep.

The study resulted in statistically significant improvements in average sleep hours and average weekend night bedtimes, suggesting adolescent understanding of the need for more sleep and the need for consistent bed times every night, including weekends. However, there was a decrease in understanding of the number of hours teenagers should sleep (8-10 hours per night). This may indicate the need to further emphasize this point. Subjects identified the sleep behavior change journals as an important factor in their ability to improve their sleep habits, suggesting that sleep knowledge is most likely not enough to achieve behavior change, rather, an interactive task was instrumental in habit improvement.

Many subjects identified electronics as a reason for not sleeping more, and use of electronics was the most common area in which students hoped to change behavior in the future. Although electronics are an important part of an adolescent’s life, teens are motivated to change their relationship with electronics in order to improve their sleep. In fact, the most common goal for change after this course was no electronics usage before bed (six subjects). Increased screening tools, education, and intervention regarding the use of electronics and their impact on sleep may be necessary.

Most participant reviews of the course were favorable. Subjects identified the most favorable aspects of the course as sleep behavior information/recommendations (11 subjects), learning sleep physiology/the effects of sleep (5), and the sleep behavior change journal helping subjects stick to their goals (4 subjects). The teens identified the most difficult things about the course as: difficulty sticking to the goals subjects set for themselves during the behavior change project (3), only having three course sessions (3), and the length of the 9-week sleep behavior change project and journal (1). When asked the top three things students learned from the course, subjects reported: caffeine physiology (10), sleep’s effect on academics (8), electronics’ effect on sleep (7), melatonin/internal clock function (6), and teen sleep physiology (4). These reviews will help inform and improve future iterations of teen sleep studies.

Limitations of this study include sample size (18), subject gender (17 female, 1 male), and self-report survey method. It would be ideal to have a larger sample size and retain a larger portion of subjects, as the six subjects who were not included in the statistical analysis were unable to finish one or more of the parts of the course. A longitudinal follow-up survey would inform whether the lessons and effects of this course persist.

Other limitations of this study include intrinsic and extrinsic bias in the pre- and postsurveys, sleep journal reporting, and data collection. Specifically, on the latter, the principal investigator handled all elements of the course and data analysis. In future studies, another investigator should assess subjects in order to avoid bias in subject responses. Additionally, those students who did not complete all parts of the study may have had a lower survey response. Eliminating them from the data analysis may have skewed the study results.

Future studies should include (1) a larger sample size with an even sex ratio, (2) varying the amount of teaching hours to see whether subjects’ degree of improvement in sleep behaviors is dose-dependent, and (3) investigation into the effects on sleep of bedtime autonomy, physical activity, noise, and responsibilities at home. A follow-up study could also include a sleep-tracking application (to minimize the subjectivity of self-report mechanisms) and monitoring of smartphone usage hours (to examine usage effect on sleep).

Adolescents appear to be receptive to sleep education and sleep behavior change. These changes may also improve their sleep knowledge and well-being. Those in the adolescent medicine, sleep medicine, and school health fields should consider the importance of sleep behavior and physiology education in their counseling of adolescents.

- Carskadon MA. Patterns of sleep and sleepiness in adolescents. Pediatrician. 1990;17(1):5-12.

- Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Jun;1021:276-91. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1308.032

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health. 2015;1(4):233-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004

- Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Richardson GS, Tate BA, Seifer R. An approach to studying circadian rhythms of adolescent humans. J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12(3):278-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/074873049701200309

- Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007 Sep;8(6):602-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2006.12.002

- Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.003 .

- Owens J; Adolescent Sleep Working Group; Committee on Adolescence. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e921-e932. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1696

- Lemola S, Perkinson-Gloor N, Brand S, Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Grob A. Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(2):405-418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0176-x

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Sleep Health, Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=38 . Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Twenge JM, Krizan Z, Hisler G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among US adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med. 2017;39:47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.013

- Hysing M, Pallesen S, Stormark KM, Jakobsen R, Lundervold AJ, Sivertsen B. Sleep and use of electronic devices in adolescence: results from a large population-based study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006748. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006748

- Li X, Buxton OM, Lee S, Chang AM, Berger LM, Hale L. Sleep mediates the association between adolescent screen time and depressive symptoms. Sleep Med. 2019;57:51-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.029

- Fatima Y, Doi SAR, Najman JM, Al Mamun A. Continuity of sleep problems from adolescence to young adulthood: results from a longitudinal study. Sleep Health. 2017;3(4):290-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2017.04.004

- Berger AT, Wahlstrom KL, Widome R. Relationships between sleep duration and adolescent depression: a conceptual replication. Sleep Health. 2019;5(2):175-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.12.003

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep. www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Understanding-Sleep . Updated February 8, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2019.

- Garey, Juliann. How to Help Teenagers Get More Sleep. Child Mind Institute Topics A-Z. https://childmind.org/article/help-teenagers-get-sleep/ . Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Adopt Good Sleep Habits. Get Sleep; 2008. https://www.healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/need-sleep/what-can-you-do/good-sleep-habits . Accessed September 16, 2019.

- Colt A, Reilly JM. Sleep Course Pre- and Post-Intervention Surveys. STFM Resource Library; April 12, 2019. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/sleep-course-pre-intervention-surve?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments . Accessed September 16, 2019.

Lead Author

Alexandra Colt, BA

Affiliations: Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Jo Marie Reilly, MD, MPH - Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Corresponding Author

Correspondence: Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, 1975 Zonal Avenue, KAM B29, Los Angeles, CA 90033.

Email: [email protected]

There are no comments for this article.

Downloads & info, related content.

- Community/Academic Partnerships

- Health Behavior Change

- Mental Health, Adolescents

Colt A, Reilly JM. An Educational Intervention to Improve the Sleep Behavior and Well-Being of High School Students. PRiMER. 2019;3:21. https://doi.org/10.22454/PRiMER.2019.871017

Citation files in RIS format are importable by EndNote, ProCite, RefWorks, Mendeley, and Reference Manager.

- RIS (EndNote, Reference Manager, ProCite, Mendeley, RefWorks)

- BibTex (JabRef, BibDesk, LaTeX)

Search Results

Contact STFM

2024 © Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. All Rights Reserved.

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Sleep Deprivation in College Students: How to Cope

Updated: September 19, 2023

Published: July 17, 2019

Did you know that 37% of people ages 20-39 report lack of sleep? Sleep deprivation in college students is a common occurrence because it takes a lot to manage balancing work, life, and school. When it comes to sleep, it is recommended that adults get 7-9 hours of sleep a night because sleep promotes proper mental, physical and psychological well being.

Often times, college students are either too stressed or too busy to get the proper amount of sleep. This is especially true when it comes to medical-related majors as compared to humanities. But, regardless of what you are studying, sleep is extremely important.

We will explore the importance of sleep, the detrimental side effects of sleep deprivation, and methods to manage both time and stress in order to get adequate sleep.

Why Sleep Matters So Much: Consequences

What happens to your body during sleep? During sleep, your body is rejuvenated. Your body’s cells are reenergized, your muscles relax, waste is removed from your brain and both learning and memory receive support.

When you don’t get enough sleep, the detrimental side effects include:

- Lowered ability to focus, which can negatively impact grades

- Overall wellbeing is decreased: you feel more stressed, are more likely to gain weight and may feel unbalanced

- Brain development is impaired

- You have poor coordination and are more likely to get hurt or in an accident

- Increased levels of anxiety and likelihood of depression

- Negative feelings increase

Research shows that with lack of sleep, you are more likely to develop diseases of the heart, diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity.

Source: Unsplash

Why sleep matters: benefits.

With adequate sleep, you become a better student for many reasons, including:

1. Learning and Memory:

Sleep consolidates memory which improves learning and retaining information. Additionally, lack of sleep means less focus making it harder to learn.

2. Improved Grades:

With the ability to study and stay more focused, you can improve your grades.

3. Improved Mood:

Sleep helps to balance your hormones so that you can maintain your mood rather than suffer from mood swings due to feeling tired.

4. Improved Health:

Since your cells are re-energized during sleep, your immune system can stay healthy and strong, which means you’ll be less likely to get sick.

Reasons for Sleep Deprivation

It’s all too common to suffer from sleep deprivation, especially if you are a student. Many of the following aspects can cause you to lose sleep, but for each, you can adjust your outlook or activities to better manage your sleep/wake cycles.

- Part-time jobs

- All nighters to cram

- Distractions like TV and social media

- Sleeping disorders

- Stress, drugs, alcohol

- Energy drinks and caffeine

- Fear of missing out

How to Overcome Sleep Deprivation

Rather than suffering from the negative consequences of lacking sleep, try the following tips:

1. Keep routine:

Go to bed early and at the same time every night.

2. Use bed only for sleep:

Set aside a different location to read or do your work/study. This is especially important if you attend school online. When you take classes online, at universities like University of the People , you have the flexibility to study whenever and wherever you choose. However, you’ll want to create a designated study area outside of your bed so that your brain associates your bed with sleep rather than work/stress/active thinking.

3. Weekend routine:

Even though it’s so tempting to sleep in during the weekend, if you are able to, you should try to wake up around the same time as you do during the week. That way, your sleep/wake cycle remains on a consistent schedule which can then regulate itself.

4. Avoid/limit caffeine and alcohol:

Caffeine is a stimulant, which not only increases anxiety, but it also speeds up your heart rate and makes it harder to relax and get shut eye. With similar negative effects on your sleep, alcohol is a depressant that affects your sleep wave patterns and can affect your breathing patterns during sleep. It also makes bathroom trips during the night more likely as your body tries to expel the toxins from your body.

5. Wind down:

Before bed, create a routine to wind down. This could include going for a short walk, reading a book, turning off your phone, practicing meditation, journaling, or drinking chamomile tea. All of these will help to ease your mind and put you in a state of relaxation before bed.

6. Schedule meals:

Because your body uses energy to digest, it’s best practice to stop eating at least two hours before going to sleep.

7. Create a bedtime ritual:

Like a morning routine, practice your wind down routine every night so that it becomes a habit. As mentioned before, try to turn phones and electronic devices off with adequate time before bed (consider keeping your phone in a different room or using do not disturb/airplane mode). Also, make sure the room is dark enough by limiting the lights from electronic machines and TVs.

8. Limit daytime naps:

If you nap too much during the day, you won’t be tired at night. Try to take power naps no longer than 30 minutes.

9. Exercise:

Get moving! This will help boost/expend energy during the day and tire you out for bedtime.

10. Learn to say no:

If you’re too tired and your friends invite you out, it’s ok to say no. The fear of missing out can tempt you to push yourself beyond your limits, but listen to your body and know that there will be more opportunities to socialize.

How to Recognize if You are Sleep Deprived

Not sure if you fit into the category of a sleep-deprived college student? Here are some symptoms to be aware of:

- Forgetfulness

- Low motivation

- Increased carbohydrate cravings

- Reduced sex drive

- Irritability

Using medication as a last resource, you can try other techniques and resources to help you sleep. Here are a few ideas:

- Headspace – Meditation App

- Relaxation Exercise

- Mindfulness Yoga

The Bottom Line

More than 70% of college students are lacking the sleep needed to properly function. Whether you are attending an online university or traditional on-campus school, time management and adequate self-care are necessary to get the sleep you need to optimize your potential.

Prioritize your sleep and practice the aforementioned techniques so that you can do better in school, as well as take care of your health!

Related Articles

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat

Sleep problems in university students – an intervention

Angelika anita schlarb.

Faculty of Psychology and Sports, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany

Anja Friedrich

Merle claßen, introduction.

Up to 60% of all college students suffer from a poor sleep quality, and 7.7% meet all criteria of an insomnia disorder. Sleep problems have a great impact on the students’ daily life, for example, the grade point average. Due to irregular daytime routines, chronotype changes, side jobs and exam periods, they need specialized treatments for improving sleep. “Studieren wie im Schlaf” (SWIS; (studying in your sleep)) is a multicomponent sleep training that combines Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia and Hypnotherapy for Insomnia to improve students’ sleep, insomnia symptoms and nightmares. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the acceptance, feasibility and the first effects of SWIS.

Twenty-seven students (mean =24.24, standard deviation =3.57) participated in a study of pre–post design. The acceptance and feasibility were measured with questionnaires. In addition, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), sleep logs and actigraphy were implemented. Further variables encompassed daytime sleepiness, sleep-related personality traits and cognitions about sleep.

Seventy-four percent of the participants reported symptoms of an insomnia disorder, and 51.9% fulfilled all criteria of an insomnia disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition). Correspondingly, the students suffered from clinically relevant sleep problems according to the PSQI. The SWIS sleep training is a well-accepted and feasible program. Significant improvements were observed in the subjective sleep quality and sleep-related personality traits, as well as clinical improvements in objective sleep measures.

Findings showed that SWIS is a feasible program for the treatment of sleep problems in college and university students due to its various effects on sleep and cognitive outcomes. Further evaluation of follow-up measurements and additional variables, that is, cognitive performance and mental health, is needed.

Video abstract

Download video file. (94M, avi)

Students experience several important developments when starting at university. They have to cope with “leaving home, increased independence, changes in peer groups, new social situations, maintenance of academic responsibilities and increased access to alcohol or drugs”. 1 About 90% of university students have roommates, and among them, 41% wake up at night due to the noise of others. Bed- and risetimes on weekdays and weekends often differ in the range of more than 1 to 2 hours. These challenges and special circumstances faced by university students are associated with sleep disturbances. 2 About 60% suffer from a poor sleep quality according to the PSQI. 3 Gaultney revealed that 27% of all university students are at a risk of at least one sleep disorder. 4 Furthermore, previous findings reported that a minimum 7.7% of students suffer from insomnia and 24.3% from nightmares. 5 , 6

Sleep problems and sleep disorders severely impair university students’ academic success. In a study conducted by Buboltz et al, 31% of all students suffered from morning tiredness. 2 In another study, poor sleepers reported reduced daytime functioning. 7 Shorter sleep duration and an irregular sleep–wake schedule significantly correlated with a lower GPA. 4 Regarding sleep habits, the wake-up times explained significant amounts of GPA variance. 8 A clinical review provided evidence that sleep problems correlated with impeded learning, especially poorer declarative and procedural learning, neurocognitive performance and academic success. 9