Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework

A Stanford researcher found that students in high-achieving communities who spend too much time on homework experience more stress, physical health problems, a lack of balance and even alienation from society. More than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive, according to the study.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

• Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

• Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

• Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Using CO₂ and biomass, researchers find path to more environmentally friendly recyclable plastics

10 hours ago

Precision agriculture research identifies gene that controls production of flowers and fruits in pea plants

Long-term forest study shows tornado's effects linger 25 years later

A new coating method in mRNA engineering points the way to advanced therapies

ATLAS provides first measurement of the W-boson width at the LHC

12 hours ago

Smart vest turns fish into underwater spies, providing a glimpse into aquatic life like never before

Ants in Colorado are on the move due to climate change

Caterpillar 'noses' are surprisingly sophisticated, researchers find

Building footprints could help identify neighborhood sociodemographic traits

13 hours ago

Fossilized dinosaur eggshells can preserve amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, over millions of years

14 hours ago

Relevant PhysicsForums posts

Motivating high school physics students with popcorn physics.

Apr 3, 2024

How is Physics taught without Calculus?

Mar 29, 2024

Why are Physicists so informal with mathematics?

Mar 24, 2024

The changing physics curriculum in 1961

Suggestions for using math puzzles to stimulate my math students.

Mar 21, 2024

The New California Math Framework: Another Step Backwards?

Mar 14, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

Earth, the sun and a bike wheel: Why your high-school textbook was wrong about the shape of Earth's orbit

Apr 8, 2024

Touchibo, a robot that fosters inclusion in education through touch

Apr 5, 2024

More than money, family and community bonds prep teens for college success: Study

Research reveals significant effects of onscreen instructors during video classes in aiding student learning

Mar 25, 2024

Prestigious journals make it hard for scientists who don't speak English to get published, study finds

Mar 23, 2024

Using Twitter/X to promote research findings found to have little impact on number of citations

Mar 22, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Second Opinion

- Research & Innovation

- Patients & Families

- Health Professionals

- Recently Visited

- Segunda opinión

- Refer a patient

- MyChart Login

Healthier, Happy Lives Blog

Sort articles by..., sort by category.

- Celebrating Volunteers

- Community Outreach

- Construction Updates

- Family-Centered Care

- Healthy Eating

- Heart Center

- Interesting Things

- Mental Health

- Patient Stories

- Research and Innovation

- Safety Tips

- Sustainability

- World-Class Care

About Our Blog

- Back-to-School

- Pediatric Technology

Latest Posts

- NICU Sims Set Stage for Lifesaving Care

- How a Social Media Post Led a Teen to Find a ‘Kidney Buddy’ for Life

- Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder in Young Children

- New Liver Gives a Toddler a Renewed Chance at Life

- Family Turns Newborn’s Rare Diagnosis Into Something Beautiful

Health Hazards of Homework

March 18, 2014 | Julie Greicius Pediatrics .

A new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education and colleagues found that students in high-performing schools who did excessive hours of homework “experienced greater behavioral engagement in school but also more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives.”

Those health problems ranged from stress, headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems, to psycho-social effects like dropping activities, not seeing friends or family, and not pursuing hobbies they enjoy.

In the Stanford Report story about the research, Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Experimental Education , says, “Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good.”

The study was based on survey data from a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in California communities in which median household income exceeded $90,000. Of the students surveyed, homework volume averaged about 3.1 hours each night.

“It is time to re-evaluate how the school environment is preparing our high school student for today’s workplace,” says Neville Golden, MD , chief of adolescent medicine at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and a professor at the School of Medicine. “This landmark study shows that excessive homework is counterproductive, leading to sleep deprivation, school stress and other health problems. Parents can best support their children in these demanding academic environments by advocating for them through direct communication with teachers and school administrators about homework load.”

Related Posts

Top-ranked group group in Los Gatos, Calif., is now a part of one of the…

The Stanford Medicine Children’s Health network continues to grow with our newest addition, Town and…

- Julie Greicius

- more by this author...

Connect with us:

Download our App:

ABOUT STANFORD MEDICINE CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Get Involved

- Volunteering Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

- Our Hospital

- Send a Greeting Card

- New Hospital

- Refer a Patient

- Pay Your Bill

Also Find Us on:

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Code of Conduct

- Price Transparency

- Stanford Medicine

- Stanford University

- Stanford Health Care

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

Is Homework Necessary? Education Inequity and Its Impact on Students

The Problem with Homework: It Highlights Inequalities

How much homework is too much homework, when does homework actually help, negative effects of homework for students, how teachers can help.

Schools are getting rid of homework from Essex, Mass., to Los Angeles, Calif. Although the no-homework trend may sound alarming, especially to parents dreaming of their child’s acceptance to Harvard, Stanford or Yale, there is mounting evidence that eliminating homework in grade school may actually have great benefits , especially with regard to educational equity.

In fact, while the push to eliminate homework may come as a surprise to many adults, the debate is not new . Parents and educators have been talking about this subject for the last century, so that the educational pendulum continues to swing back and forth between the need for homework and the need to eliminate homework.

One of the most pressing talking points around homework is how it disproportionately affects students from less affluent families. The American Psychological Association (APA) explained:

“Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs.”

[RELATED] How to Advance Your Career: A Guide for Educators >>

While students growing up in more affluent areas are likely playing sports, participating in other recreational activities after school, or receiving additional tutoring, children in disadvantaged areas are more likely headed to work after school, taking care of siblings while their parents work or dealing with an unstable home life. Adding homework into the mix is one more thing to deal with — and if the student is struggling, the task of completing homework can be too much to consider at the end of an already long school day.

While all students may groan at the mention of homework, it may be more than just a nuisance for poor and disadvantaged children, instead becoming another burden to carry and contend with.

Beyond the logistical issues, homework can negatively impact physical health and stress — and once again this may be a more significant problem among economically disadvantaged youth who typically already have a higher stress level than peers from more financially stable families .

Yet, today, it is not just the disadvantaged who suffer from the stressors that homework inflicts. A 2014 CNN article, “Is Homework Making Your Child Sick?” , covered the issue of extreme pressure placed on children of the affluent. The article looked at the results of a study surveying more than 4,300 students from 10 high-performing public and private high schools in upper-middle-class California communities.

“Their findings were troubling: Research showed that excessive homework is associated with high stress levels, physical health problems and lack of balance in children’s lives; 56% of the students in the study cited homework as a primary stressor in their lives,” according to the CNN story. “That children growing up in poverty are at-risk for a number of ailments is both intuitive and well-supported by research. More difficult to believe is the growing consensus that children on the other end of the spectrum, children raised in affluence, may also be at risk.”

When it comes to health and stress it is clear that excessive homework, for children at both ends of the spectrum, can be damaging. Which begs the question, how much homework is too much?

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association recommend that students spend 10 minutes per grade level per night on homework . That means that first graders should spend 10 minutes on homework, second graders 20 minutes and so on. But a study published by The American Journal of Family Therapy found that students are getting much more than that.

While 10 minutes per day doesn’t sound like much, that quickly adds up to an hour per night by sixth grade. The National Center for Education Statistics found that high school students get an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, a figure that is much too high according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It is also to be noted that this figure does not take into consideration the needs of underprivileged student populations.

In a study conducted by the OECD it was found that “after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance .” That means that by asking our children to put in an hour or more per day of dedicated homework time, we are not only not helping them, but — according to the aforementioned studies — we are hurting them, both physically and emotionally.

What’s more is that homework is, as the name implies, to be completed at home, after a full day of learning that is typically six to seven hours long with breaks and lunch included. However, a study by the APA on how people develop expertise found that elite musicians, scientists and athletes do their most productive work for about only four hours per day. Similarly, companies like Tower Paddle Boards are experimenting with a five-hour workday, under the assumption that people are not able to be truly productive for much longer than that. CEO Stephan Aarstol told CNBC that he believes most Americans only get about two to three hours of work done in an eight-hour day.

In the scope of world history, homework is a fairly new construct in the U.S. Students of all ages have been receiving work to complete at home for centuries, but it was educational reformer Horace Mann who first brought the concept to America from Prussia.

Since then, homework’s popularity has ebbed and flowed in the court of public opinion. In the 1930s, it was considered child labor (as, ironically, it compromised children’s ability to do chores at home). Then, in the 1950s, implementing mandatory homework was hailed as a way to ensure America’s youth were always one step ahead of Soviet children during the Cold War. Homework was formally mandated as a tool for boosting educational quality in 1986 by the U.S. Department of Education, and has remained in common practice ever since.

School work assigned and completed outside of school hours is not without its benefits. Numerous studies have shown that regular homework has a hand in improving student performance and connecting students to their learning. When reviewing these studies, take them with a grain of salt; there are strong arguments for both sides, and only you will know which solution is best for your students or school.

Homework improves student achievement.

- Source: The High School Journal, “ When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math ,” 2012.

- Source: IZA.org, “ Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement? ,” 2014. **Note: Study sample comprised only high school boys.

Homework helps reinforce classroom learning.

- Source: “ Debunk This: People Remember 10 Percent of What They Read ,” 2015.

Homework helps students develop good study habits and life skills.

- Sources: The Repository @ St. Cloud State, “ Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement ,” 2017; Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

- Source: Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

Homework allows parents to be involved with their children’s learning.

- Parents can see what their children are learning and working on in school every day.

- Parents can participate in their children’s learning by guiding them through homework assignments and reinforcing positive study and research habits.

- Homework observation and participation can help parents understand their children’s academic strengths and weaknesses, and even identify possible learning difficulties.

- Source: Phys.org, “ Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework ,” 2018.

While some amount of homework may help students connect to their learning and enhance their in-class performance, too much homework can have damaging effects.

Students with too much homework have elevated stress levels.

- Source: USA Today, “ Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In ,” 2021.

- Source: Stanford University, “ Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework ,” 2014.

Students with too much homework may be tempted to cheat.

- Source: The Chronicle of Higher Education, “ High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame ,” 2010.

- Source: The American Journal of Family Therapy, “ Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background ,” 2015.

Homework highlights digital inequity.

- Sources: NEAToday.org, “ The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’ ,” 2016; CNET.com, “ The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind ,” 2021.

- Source: Investopedia, “ Digital Divide ,” 2022; International Journal of Education and Social Science, “ Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework ,” 2015.

- Source: World Economic Forum, “ COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it ,” 2021.

Homework does not help younger students.

- Source: Review of Educational Research, “ Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003 ,” 2006.

To help students find the right balance and succeed, teachers and educators must start the homework conversation, both internally at their school and with parents. But in order to successfully advocate on behalf of students, teachers must be well educated on the subject, fully understanding the research and the outcomes that can be achieved by eliminating or reducing the homework burden. There is a plethora of research and writing on the subject for those interested in self-study.

For teachers looking for a more in-depth approach or for educators with a keen interest in educational equity, formal education may be the best route. If this latter option sounds appealing, there are now many reputable schools offering online master of education degree programs to help educators balance the demands of work and family life while furthering their education in the quest to help others.

YOU’RE INVITED! Watch Free Webinar on USD’s Online MEd Program >>

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Top 11 Reasons to get Your Master of Education Degree

Free 22-page Book

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Advertisement

Academic dishonesty when doing homework: How digital technologies are put to bad use in secondary schools

- Open access

- Published: 23 July 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 1251–1271, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Juliette C. Désiron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3074-9018 1 &

- Dominik Petko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1569-1302 1

5763 Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The growth in digital technologies in recent decades has offered many opportunities to support students’ learning and homework completion. However, it has also contributed to expanding the field of possibilities concerning homework avoidance. Although studies have investigated the factors of academic dishonesty, the focus has often been on college students and formal assessments. The present study aimed to determine what predicts homework avoidance using digital resources and whether engaging in these practices is another predictor of test performance. To address these questions, we analyzed data from the Program for International Student Assessment 2018 survey, which contained additional questionnaires addressing this issue, for the Swiss students. The results showed that about half of the students engaged in one kind or another of digitally-supported practices for homework avoidance at least once or twice a week. Students who were more likely to use digital resources to engage in dishonest practices were males who did not put much effort into their homework and were enrolled in non-higher education-oriented school programs. Further, we found that digitally-supported homework avoidance was a significant negative predictor of test performance when considering information and communication technology predictors. Thus, the present study not only expands the knowledge regarding the predictors of academic dishonesty with digital resources, but also confirms the negative impact of such practices on learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of smartphone use on learning effectiveness: A case study of primary school students

Jen Chun Wang, Chia-Yen Hsieh & Shih-Hao Kung

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

Geofrey Kansiime & Marjorie Sarah Kabuye Batiibwe

Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning

Jamal Abdul Nasir Ansari & Nawab Ali Khan

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Academic dishonesty is a widespread and perpetual issue for teachers made even more easier to perpetrate with the rise of digital technologies (Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017 ; Ma et al., 2008 ). Definitions vary but overall an academically dishonest practices correspond to learners engaging in unauthorized practice such as cheating and plagiarism. Differences in engaging in those two types of practices mainly resides in students’ perception that plagiarism is worse than cheating (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; McCabe, 2005 ). Plagiarism is usually defined as the unethical act of copying part or all of someone else’s work, with or without editing it, while cheating is more about sharing practices (Krou et al., 2021 ). As a result, most students do report cheating in an exam or for homework (Ma et al., 2008 ). To note, other research follow a different distinction for those practices and consider that plagiarism is a specific – and common – type of cheating (Waltzer & Dahl, 2022 ). Digital technologies have contributed to opening possibilities of homework avoidance and technology-related distraction (Ma et al., 2008 ; Xu, 2015 ).

The question of whether the use of digital resources hinders or enhances homework has often been investigated in large-scale studies, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). While most of the early large-scale studies showed positive overall correlations between the use of digital technologies for learning at home and test scores in language, mathematics, and science (e.g., OECD, 2015 ; Petko et al., 2017 ; Skryabin et al., 2015 ), there have been more recent studies reporting negative associations as well (Agasisti et al., 2020 ; Odell et al., 2020 ). One reason for these inconclusive findings is certainly the complex interplay of related factors, which include diverse ways of measuring homework, gender, socioeconomic status, personality traits, learning goals, academic abilities, learning strategies, motivation, and effort, as well as support from teachers and parents. Despite this complexity, it needs to be acknowledged that doing homework digitally does not automatically lead to productive learning activities, and it might even be associated with counter-productive practices such as digital distraction or academic dishonesty. Digitally enhanced academic dishonesty has mostly been investigated regarding formal assessment-related examinations (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; Ma et al., 2008 ); however, it might be equally important to investigate its effects regarding learning-related assignments such as homework. Although a large body of research exists on digital academic dishonesty regarding assignments in higher education, relatively few studies have investigated this topic on K12 homework. To investigate this issue, we integrated questionnaire items on homework engagement and digital homework avoidance in a national add-on to PISA 2018 in Switzerland. Data from the Swiss sample can serve as a case study for further research with a wider cultural background. This study provides an overview of the descriptive results and tries to identify predictors of the use of digital technology for academic dishonesty when completing homework.

1.1 Prevalence and factors of digital academic dishonesty in schools

According to Pavela’s ( 1997 ) framework, four different types of academic dishonesty can be distinguished: cheating by using unauthorized materials, plagiarism by copying the work of others, fabrication of invented evidence, and facilitation by helping others in their attempts at academic dishonesty. Academic dishonesty can happen in assessment situations, as well as in learning situations. In formal assessments, academic dishonesty usually serves the purpose of passing a test or getting a better grade despite lacking the proper abilities or knowledge. In learning-related situations such as homework, where assignments are mandatory, cheating practices equally qualify as academic dishonesty. For perpetrators, these practices can be seen as shortcuts in which the willingness to invest the proper time and effort into learning is missing (Chow, 2021; Waltzer & Dahl, 2022 ). The interviews by Waltzer & Dahl ( 2022 ) reveal that students do perceive cheating as being wrong but this does not prevent them from engaging in at least one type of dishonest practice. While academic dishonesty is not a new phenomenon, it has been changing together with the development of new digital technologies (Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Ercegovac & Richardson, 2004 ). With the rapid growth in technologies, new forms of homework avoidance, such as copying and plagiarism, are developing (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; Ma et al., 2008 ) summarized the findings of the 2006 U.S. surveys of the Josephson Institute of Ethics with the conclusion that the internet has led to a deterioration of ethics among students. In 2006, one-third of high school students had copied an internet document in the past 12 months, and 60% had cheated on a test. In 2012, these numbers were updated to 32% and 51%, respectively (Josephson Institute of Ethics, 2012 ). Further, 75% reported having copied another’s homework. Surprisingly, only a few studies have provided more recent evidence on the prevalence of academic dishonesty in middle and high schools. The results from colleges and universities are hardly comparable, and until now, this topic has not been addressed in international large-scale studies on schooling and school performance.

Despite the lack of representative studies, research has identified many factors in smaller and non-representative samples that might explain why some students engage in dishonest practices and others do not. These include male gender (Whitley et al., 1999 ), the “dark triad” of personality traits in contrast to conscientiousness and agreeableness (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2021 ; Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015 ), extrinsic motivation and performance/avoidance goals in contrast to intrinsic motivation and mastery goals (e.g., Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Krou et al., 2021 ), self-efficacy and achievement scores (e.g., Nora & Zhang, 2010 ; Yaniv et al., 2017 ), unethical attitudes, and low fear of being caught (e.g., Cheng et al., 2021 ; Kam et al., 2018 ), influenced by the moral norms of peers and the conditions of the educational context (e.g., Isakov & Tripathy, 2017 ; Kapoor & Kaufman, 2021 ). Similar factors have been reported regarding research on the causes of plagiarism (Husain et al., 2017 ; Moss et al., 2018 ). Further, the systematic review from Chiang et al. ( 2022 ) focused on factors of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. The analyses, based on the six-components behavior engineering, showed that the most prominent factors were environmental (effect of incentives) and individual (effect of motivation). Despite these intensive research efforts, there is still no overarching model that can comprehensively explain the interplay of these factors.

1.2 Effects of homework engagement and digital dishonesty on school performance

In meta-analyses of schools, small but significant positive effects of homework have been found regarding learning and achievement (e.g., Baş et al., 2017 ; Chen & Chen, 2014 ; Fan et al., 2017 ). In their review, Fan et al. ( 2017 ) found lower effect sizes for studies focusing on the time or frequency of homework than for studies investigating homework completion, homework grades, or homework effort. In large surveys, such as PISA, homework measurement by estimating after-school working hours has been customary practice. However, this measure could hide some other variables, such as whether teachers even give homework, whether there are school or state policies regarding homework, where the homework is done, whether it is done alone, etc. (e.g., Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 , 2017 ). Trautwein ( 2007 ) and Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) repeatedly showed that homework effort rather than the frequency or the time spent on homework can be considered a better predictor for academic achievement Effort and engagement can be seen as closely interrelated. Martin et al. ( 2017 ) defined engagement as the expressed behavior corresponding to students’ motivation. This has been more recently expanded by the notion of the quality of homework completion (Rosário et al., 2018 ; Xu et al., 2021 ). Therefore, it is a plausible assumption that academic dishonesty when doing homework is closely related to low homework effort and a low quality of homework completion, which in turn affects academic achievement. However, almost no studies exist on the effects of homework avoidance or academic dishonesty on academic achievement. Studies investigating the relationship between academic dishonesty and academic achievement typically use academic achievement as a predictor of academic dishonesty, not the other way around (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2019 ; McCabe et al., 2001 ). The results of these studies show that low-performing students tend to engage in dishonest practices more often. However, high-performing students also seem to be prone to cheating in highly competitive situations (Yaniv et al., 2017 ).

1.3 Present study and hypotheses

The present study serves three combined purposes.

First, based on the additional questionnaires integrated into the Program for International Student Assessment 2018 (PISA 2018) data collection in Switzerland, we provide descriptive figures on the frequency of homework effort and the various forms of digitally-supported homework avoidance practices.

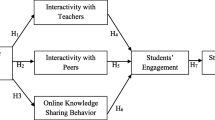

Second, the data were used to identify possible factors that explain higher levels of digitally-supported homework avoidance practices. Based on our review of the literature presented in Section 1.1 , we hypothesized (Hypothesis 1 – H1) that these factors include homework effort, age, gender, socio-economic status, and study program.

Finally, we tested whether digitally-supported homework avoidance practices were a significant predictor of test score performance. We expected (Hypothesis 2 – H2) that technology-related factors influencing test scores include not only those reported by Petko et al. ( 2017 ) but also self-reported engagement in digital dishonesty practices. .

2.1 Participants

Our analyses were based on data collected for PISA 2018 in Switzerland, made available in June 2021 (Erzinger et al., 2021 ). The target sample of PISA was 15-year-old students, with a two-phase sampling: schools and then students (Erzinger et al., 2019 , p.7–8, OECD, 2019a ). A total of 228 schools were selected for Switzerland, with an original sample of 5822 students. Based on the PISA 2018 technical report (OECD, 2019a ), only participants with a minimum of three valid responses to each scale used in the statistical analyses were included (see Section 2.2 ). A final sample of 4771 responses (48% female) was used for statistical analyses. The mean age was 15 years and 9 months ( SD = 3 months). As Switzerland is a multilingual country, 60% of the respondents completed the questionnaires in German, 23% in French, and 17% in Italian.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 digital dishonesty in homework scale.

This six-item digital dishonesty for homework scale assesses the use of digital technology for homework avoidance and copying (IC801 C01 to C06), is intended to work as a single overall scale for digital homework dishonesty practice constructed to include items corresponding to two types of dishonest practices from Pavela ( 1997 ), namely cheating and plagiarism (see Table 1 ). Three items target individual digital practices to avoid homework, which can be referred to as plagiarism (items 1, 2 and 5). Two focus more on social digital practices, for which students are cheating together with peers (items 4 and 6). One item target cheating as peer authorized plagiarism. Response options are based on questions on the productive use of digital technologies for homework in the common PISA survey (IC010), with an additional distinction for the lowest frequency option (6-point Likert scale). The scale was not tested prior to its integration into the PISA questionnaire, as it was newly developed for the purposes of this study.

2.2.2 Homework engagement scale

The scale, originally developed by Trautwein et al. (Trautwein, 2007 ; Trautwein et al., 2006 ), measures homework engagement (IC800 C01 to C06) and can be subdivided into two sub-scales: homework compliance and homework effort. The reliability of the scale was tested and established in different variants, both in Germany (Trautwein et al., 2006 ; Trautwein & Köller, 2003 ) and in Switzerland (Schnyder et al., 2008 ; Schynder Godel, 2015 ). In the adaptation used in the PISA 2018 survey, four items were positively poled (items 1, 2, 4, and 6), and two items were negatively poled (items 3 and 5) and presented with a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Does not apply at all” to “Applies absolutely.” This adaptation showed acceptable reliability in previous studies in Switzerland (α = 0.73 and α = 0.78). The present study focused on homework effort, and thus only data from the corresponding sub-scale was analyzed (items 2 [I always try to do all of my homework], 4 [When it comes to homework, I do my best], and 6 [On the whole, I think I do my homework more conscientiously than my classmates]).

2.2.3 Demographics

Previous studies showed that demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status, could impact learning outcomes (Jacobs et al., 2002 ) and intention to use digital tools for learning (Tarhini et al., 2014 ). Gender is a dummy variable (ST004), with 1 for female and 2 for male. Socioeconomic status was analyzed based on the PISA 2018 index of economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS). It is computed from three other indices (OECD, 2019b , Annex A1): parents’ highest level of education (PARED), parents’ highest occupational status (HISEI), and home possessions (HOMEPOS). The final ESCS score is transformed so that 0 corresponds to an average OECD student. More details can be found in Annex A1 from PISA 2018 Results Volume 3 (OECD, 2019b ).

2.2.4 Study program

Although large-scale studies on schools have accounted for the differences between schools, the study program can also be a factor that directly affects digital homework dishonesty practices. In Switzerland, 15-year-old students from the PISA sampling pool can be part of at least six main study programs, which greatly differ in terms of learning content. In this study, study programs distinguished both level and type of study: lower secondary education (gymnasial – n = 798, basic requirements – n = 897, advanced requirements – n = 1235), vocational education (classic – n = 571, with baccalaureate – n = 275), and university entrance preparation ( n = 745). An “other” category was also included ( n = 250). This 6-level ordinal variable was dummy coded based on the available CNTSCHID variable.

2.2.5 Technologies and schools

The PISA 2015 ICT (Information and Communication Technology) familiarity questionnaire included most of the technology-related variables tested by Petko et al. ( 2017 ): ENTUSE (frequency of computer use at home for entertainment purposes), HOMESCH (frequency of computer use for school-related purposes at home), and USESCH (frequency of computer use at school). However, the measure of student’s attitudes toward ICT in the 2015 survey was different from that of the 2012 dataset. Based on previous studies (Arpacı et al., 2021 ; Kunina-Habenicht & Goldhammer, 2020 ), we thus included INICT (Student’s ICT interest), COMPICT (Students’ perceived ICT competence), AUTICT (Students’ perceived autonomy related to ICT use), and SOIACICT (Students’ ICT as a topic in social interaction) instead of the variable ICTATTPOS of the 2012 survey.

2.2.6 Test scores

The PISA science, mathematics, and reading test scores were used as dependent variables to test our second hypothesis. Following Aparicio et al. ( 2021 ), the mean scores from plausible values were computed for each test score and used in the test score analysis.

2.3 Data analyses

Our hypotheses aim to assess the factors explaining student digital homework dishonesty practices (H1) and test score performance (H2). At the student level, we used multilevel regression analyses to decompose the variance and estimate associations. As we used data for Switzerland, in which differences between school systems exist at the level of provinces (within and between), we also considered differences across schools (based on the variable CNTSCHID).

Data were downloaded from the main PISA repository, and additional data for Switzerland were available on forscenter.ch (Erzinger et al., 2021 ). Analyses were computed with Jamovi (v.1.8 for Microsoft Windows) statistics and R packages (GAMLj, lavaan).

3.1 Additional scales for Switzerland

3.1.1 digital dishonesty in homework practices.

The digital homework dishonesty scale (6 items), computed with the six items IC801, was found to be of very good reliability overall (α = 0.91, ω = 0.91). After checking for reliability, a mean score was computed for the overall scale. The confirmatory factor analysis for the one-dimensional model reached an adequate fit, with three modifications using residual covariances between single items χ 2 (6) = 220, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.969, CFI = 0.988, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.086, SRMR = 0.016).

On the one hand, the practice that was the least reported was copying something from the internet and presenting it as their own (51% never did). On the other hand, students were more likely to partially copy content from the internet and modify it to present as their own (47% did it at least once a month). Copying answers shared by friends was rather common, with 62% of the students reporting that they engaged in such practices at least once a month.

When all surveyed practices were taken together, 7.6% of the students reported that they had never engaged in digitally dishonest practices for homework, while 30.6% reported cheating once or twice a week, 12.1% almost every day, and 6.9% every day (Table 1 ).

3.1.2 Homework effort

The overall homework engagement scale consisted of six items (IC800), and it was found to be acceptably reliable (α = 0.76, ω = 0.79). Items 3 and 5 were reversed for this analysis. The homework compliance sub-scale had a low reliability (α = 0.58, ω = 0.64), whereas the homework effort sub-scale had an acceptable reliability (α = 0.78, ω = 0.79). Based on our rationale, the following statistical analyses used only the homework effort sub-scale. Furthermore, this focus is justified by the fact that the homework compliance scale might be statistically confounded with the digital dishonesty in homework scale.

Descriptive weighted statistics per item (Table 2 ) showed that while most students (80%) tried to complete all of their homework, only half of the students reported doing those diligently (53.3%). Most students also reported that they believed they put more effort into their homework than their peers (77.7%). The overall mean score of the composite scale was 2.81 ( SD = 0.69).

3.2 Multilevel regression analysis: Predictors of digital dishonesty in homework (H1)

Mixed multilevel modeling was used to analyze predictors of digital homework avoidance while considering the effect of school (random component). Based on our first hypothesis, we compared several models by progressively including the following fixed effects: homework effort and personal traits (age, gender) (Model 2), then socio-economic status (Model 3), and finally, study program (Model 4). The results are presented in Table 3 . Except for the digital homework dishonesty and homework efforts scales, all other scales were based upon the scores computed according to the PISA technical report (OECD, 2019a ).

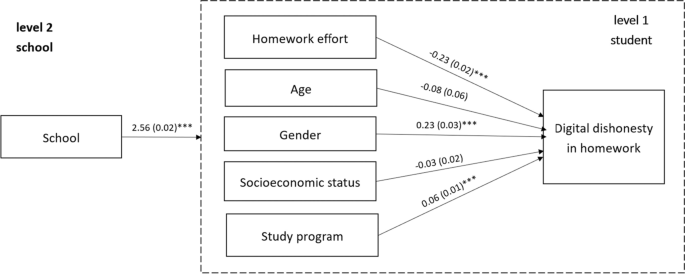

We first compared variance components. Variance was decomposed into student and school levels. Model 1 provides estimates of the variance component without any covariates. The intraclass coefficient (ICC) indicated that about 6.6% of the total variance was associated with schools. The parameter (b = 2.56, SE b = 0.025 ) falls within the 95% confidence interval. Further, CI is above 0 and thus we can reject the null hypothesis. Comparing the empty model to models with covariates, we found that Models 2, 3 and 4 showed an increase in total explained variance to 10%. Variance explained by the covariates was about 3% in Models 2 and 3, and about 4% in Model 4. Interestingly, in our models, student socio-economic status, measured by the PISA index, never accounted for variance in digitally-supported dishonest practices to complete homework.

Summary of the two-steps Model 4 (estimates - β, with standard errors and significance levels, *** p < 0.001)

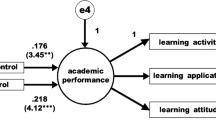

Further, model comparison based on AIC indicates that Model 4, including homework effort, personal traits, socio-economic status, and study program, was the better fit for the data. In Model 4 (Table 3 ; Fig. 1 ), we observed that homework effort and gender were negatively associated with digital dishonesty. Male students who invested less effort in their homework were more prone to engage in digital dishonesty. The study program was positively but weakly associated with digital dishonesty. Students in programs that target higher education were less likely to engage in digital dishonesty when completing homework.

3.3 Multilevel regression analysis: Cheating and test scores (H2)

Our first hypothesis aimed to provide insights into characteristics of students reporting that they regularly use digital resources dishonestly when completing homework. Our second hypothesis focused on whether digitally-supported homework avoidance practices was linked to results of test scores. Mixed multilevel modeling was used to analyze predictors of test scores while considering the effect of school (random component). Based on the study by Petko et al. ( 2017 ), we compared several models by progressively including the following fixed effects ICT use (three measures) (Model 2), then attitude toward ICT (four measures) (Model 3), and finally, digital dishonesty in homework (single measure) (Model 4). The results are presented in Table 4 for science, Table 5 for mathematics, and Table 6 for reading.

Variance components were decomposed into student and school level. ICC for Model 1 indicated that 37.9% of the variance component without covariates was associated with schools.

Taking Model 1 as a reference, we observed an increase in total explained variance to 40.5% with factors related to ICT use (Model 2), to 40.8% with factors related to attitude toward ICT (Model 3), and to 41.1% with the single digital dishonesty factor. It is interesting to note that we obtained different results from those reported by Petko et al. ( 2017 ). In their study, they found significant effects on the explained variances of ENTUSE, USESCH, and ICTATTPOS but not of HOMESCH for Switzerland. In the present study (Model 3), HOMESCH and USESCH were significant predictors but not ENTUSE, and for attitude toward ICT, all but INTICT were significant predictors of the variance. However, factors corresponding to ICT use were negatively associated with test performance, as in the study by Petko et al. ( 2017 ). Similarly, all components of attitude toward ICT positively affected science test scores, except for students’ ICT as a topic in social interaction.

Based on the AIC values, Model 4, including ICT use, attitude toward ICT, and digital dishonesty, was the better fit for the data. The parameter ( b = 498.00, SE b = 3.550) shows that our sample falls within the 95% confidence interval and that we can reject the null hypothesis. In this model, all factors except the use of ICT outside of school for leisure were significant predictors of explained variance in science test scores. These results are consistent with those reported by Petko et al. ( 2017 ), in which more frequent use of ICT negatively affected science test scores, with an overall positive effect of positive attitude toward ICT. Further, we observed that homework avoidance with digital resources strongly negatively affected performance, with lower performance associated with students reporting a higher frequency of engagement in digital dishonesty practices.

For mathematics test scores, results from Models 2 and 3 showed a similar pattern than those for science, and Model 4 also explained the highest variance (41.2%). The results from Model 4 contrast with those found by Petko et al. ( 2017 ), as in this study, HOMESCH was the only significant variable of ICT use. Regarding attitudes toward ICT, only two measures (COMPICT and AUTICT) were significant positive factors in Model 4. As for science test scores, digital dishonesty practices were a significantly strong negative predictor. Students who reported cheating more frequently were more likely to perform poorly on mathematics tests.

The analyses of PISA test scores for reading in Model 2 was similar to that of science and mathematics, with ENTUSE being a non-significant predictor when we included only measures of ICT use as predictors. In Model 3, contrary to the science and mathematics test scores models, in which INICT was non-significant, all measures of attitude toward ICT were positively significant predictors. Nevertheless, as for science and mathematics, Model 4, which included digital dishonesty, explained the greater variance in reading test scores (42.2%). We observed that for reading, all predictors were significant in Model 4, with an overall negative effect of ICT use, a positive effect of attitude toward ICT—except for SOIAICT, and a negative effect of digital dishonesty on test scores. Interestingly, the detrimental effect of using digital resources to engage in dishonest homework completion was the strongest in reading test scores.

4 Discussion

In this study, we were able to provide descriptive statistics on the prevalence of digital dishonesty among secondary students in the Swiss sample of PISA 2018. Students from this country were selected because they received additional questions targeting both homework effort and the frequency with which they engaged in digital dishonesty when doing homework. Descriptive statistics indicated that fairly high numbers of students engage in dishonest homework practices, with 49.6% reporting digital dishonesty at least once or twice a week. The most frequently reported practice was copying answers from friends, which was undertaken at least once a month by more than two-thirds of respondents. Interestingly, the most infamous form of digital dishonesty, that is plagiarism by copy-pasting something from the internet (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ), was admitted to by close to half of the students (49%). These results for homework avoidance are close to those obtained by previous research on digital academic plagiarism (e.g., McCabe et al., 2001 ).

We then investigated what makes a cheater, based on students’ demographics and effort put in doing their homework (H1), before looking at digital dishonesty as an additional ICT predictor of PISA test scores (mathematics, reading, and science) (H2).

The goal of our first research hypothesis was to determine student-related factors that may predict digital homework avoidance practices. Here, we focused on factors linked to students’ personal characteristics and study programs. Our multilevel model explained about 10% of the variance overall. Our analysis of which students are more likely to digital resources to avoid homework revealed an increased probability for male students who did not put much effort into doing their homework and who were studying in a program that was not oriented toward higher education. Thus, our findings tend to support results from previous research that stresses the importance of gender and motivational factors for academic dishonesty (e.g., Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Krou et al., 2021 ). Yet, as our model only explained little variance and more research is needed to provide an accurate representation of the factors that lead to digital dishonesty. Future research could include more aspects that are linked to learning, such as peer-related or teaching-related factors. Possibly, how closely homework is embedded in the teaching and learning culture may play a key role in digital dishonesty. Additional factors might be linked to the overall availability and use of digital tools. For example, the report combining factors from the PISA 2018 school and student questionnaires showed that the higher the computer–student ratio, the lower students scored in the general tests (OECD, 2020b ). A positive association with reading disappeared when socio-economic background was considered. This is even more interesting when considering previous research indicating that while internet access is not a source of divide among youths, the quality of use is still different based on gender or socioeconomic status (Livingstone & Helsper, 2007 ). Thus, investigating the usage-related “digital divide” as a potential source of digital dishonesty is an interesting avenue for future research (Dolan, 2016 ).

Our second hypothesis considered that digital dishonesty in homework completion can be regarded as an additional ICT-related trait and thus could be included in models targeting the influence of traditional ICT on PISA test scores, such as Petko et al. ( 2017 ) study. Overall, our results on the influence of ICT use and attitudes toward ICT on test scores are in line with those reported by Petko et al. ( 2017 ). Digital dishonesty was found to negatively influence test scores, with a higher frequency of cheating leading to lower performance in all major PISA test domains, and particularly so for reading. For each subject, the combined models explained about 40% of the total variance.

4.1 Conclusions and recommendations

Our results have several practical implications. First, the amount of cheating on homework observed calls for new strategies for raising homework engagement, as this was found to be a clear predictor of digital dishonesty. This can be achieved by better explaining the goals and benefits of homework, the adverse effects of cheating on homework, and by providing adequate feedback on homework that was done properly. Second, teachers might consider new forms of homework that are less prone to cheating, such as doing homework in non-digital formats that are less easy to copy digitally or in proctored digital formats that allow for the monitoring of the process of homework completion, or by using plagiarism software to check homework. Sometimes, it might even be possible to give homework and explicitly encourage strategies that might be considered cheating, for example, by working together or using internet sources. As collaboration is one of the 21st century skills that students are expected to develop (Bray et al., 2020 ), this can be used to turn cheating into positive practice. There is already research showing the beneficial impact of computer-supported collaborative learning (e.g., Janssen et al., 2012 ). Zhang et al. ( 2011 ) compared three homework assignment (creation of a homepage) conditions: individually, in groups with specific instructions, and in groups with general instructions. Their results showed that computer supported collaborative homework led to better performance than individual settings, only when the instructions were general. Thus, promoting digital collaborative homework could support the development of students’ digital and collaborative skills.

Further, digital dishonesty in homework needs to be considered different from cheating in assessments. In research on assessment-related dishonesty, cheating is perceived as a reprehensible practice because grades obtained are a misrepresentation of student knowledge, and cheating “implies that efficient cheaters are good students, since they get good grades” (Bouville, 2010 , p. 69). However, regarding homework, this view is too restrictive. Indeed, not all homework is graded, and we cannot know for sure whether students answered this questionnaire while considering homework as a whole or only graded homework (assessments). Our study did not include questions about whether students displayed the same attitudes and practices toward assessments (graded) and practice exercises (non-graded), nor did it include questions on how assessments and homework were related. By cheating on ungraded practice exercises, students will primarily hamper their own learning process. Future research could investigate in more depth the kinds of homework students cheat on and why.

Finally, the question of how to foster engaging homework with digital tools becomes even more important in pandemic situations. Numerous studies following the switch to home schooling at the beginning of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic have investigated the difficulties for parents in supporting their children (Bol, 2020 ; Parczewska, 2021 ); however, the question of digital homework has not been specifically addressed. It is unknown whether the increase in digital schooling paired with discrepancies in access to digital tools has led to an increase in digital dishonesty practices. Data from the PISA 2018 student questionnaires (OECD, 2020a ) indicated that about 90% of students have a computer for schoolwork (OECD average), but the availability per student remains unknown. Digital homework can be perceived as yet another factor of social differences (see for example Auxier & Anderson, 2020 ; Thorn & Vincent-Lancrin, 2022 ).

4.2 Limitations and directions

The limitations of the study include the format of the data collected, with the accuracy of self-reports to mirror actual practices restricted, as these measures are particularly likely to trigger response bias, such as social desirability. More objective data on digital dishonesty in homework-related purposes could, for example, be obtained by analyzing students’ homework with plagiarism software. Further, additional measures that provide a more complete landscape of contributing factors are necessary. For example, in considering digital homework as an alternative to traditional homework, parents’ involvement in homework and their attitudes toward ICT are factors that have not been considered in this study (Amzalag, 2021 ). Although our results are in line with studies on academic digital dishonesty, their scope is limited to the Swiss context. Moreover, our analyses focused on secondary students. Results might be different with a sample of younger students. As an example, Kiss and Teller ( 2022 ) measured primary students cheating practices and found that individual characteristics were not a stable predictor of cheating between age groups. Further, our models included school as a random component, yet other group variables, such as class and peer groups, may well affect digital homework avoidance strategies.

The findings of this study suggest that academic dishonesty when doing homework needs to be addressed in schools. One way, as suggested by Chow et al. ( 2021 ) and Djokovic et al. ( 2022 ), is to build on students’ practices to explain which need to be considered cheating. This recommendation for institutions to take preventive actions and explicit to students the punishment faced in case of digital academic behavior was also raised by Chiang et al. ( 2022 ). Another is that teachers may consider developing homework formats that discourage cheating and shortcuts (e.g., creating multimedia documents instead of text-based documents, using platforms where answers cannot be copied and pasted, or using advanced forms of online proctoring). It may also be possible to change homework formats toward more open formats, where today’s cheating practices are allowed when they are made transparent (open-book homework, collaborative homework). Further, experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic have stressed the importance of understanding the factors related to the successful integration of digital homework and the need to minimize the digital “homework gap” (Auxier & Anderson, 2020 ; Donnelly & Patrinos, 2021 ). Given that homework engagement is a core predictor of academic dishonesty, students should receive meaningful homework in preparation for upcoming lessons or for practicing what was learned in past lessons. Raising student’s awareness of the meaning and significance of homework might be an important piece of the puzzle to honesty in learning.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in SISS base at https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-1285-1 , reference number 1285.

Agasisti, T., Gil-Izquierdo, M., & Han, S. W. (2020). ICT Use at home for school-related tasks: What is the effect on a student’s achievement? Empirical evidence from OECD PISA data. Education Economics, 28 (6), 601–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2020.1822787

Article Google Scholar

Amzalag, M. (2021). Parent attitudes towards the integration of digital learning games as an alternative to traditional homework. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 17 (3), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.20210701.oa10

Anderman, E. M., & Koenka, A. C. (2017). The relation between academic motivation and cheating. Theory into Practice, 56 (2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1308172

Aparicio, J., Cordero, J. M., & Ortiz, L. (2021). Efficiency analysis with educational data: How to deal with plausible values from international large-scale assessments. Mathematics, 9 (13), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9131579

Arpacı, S., Mercan, F., & Arıkan, S. (2021). The differential relationships between PISA 2015 science performance and, ICT availability, ICT use and attitudes toward ICT across regions: evidence from 35 countries. Education and Information Technologies, 26 (5), 6299–6318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10576-2

Auxier, B., & Anderson, M. (2020, March 16). As schools close due to the coronavirus, some U.S. students face a digital “homework gap”. Pew Research Center, 1–8. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/19/5-charts-on-global-views-of-china/ . Retrieved November 29th, 2021

Baş, G., Şentürk, C., & Ciğerci, F. M. (2017). Homework and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Issues in Educational Research, 27 (1), 31–50.

Google Scholar

Blau, I., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2017). The ethical dissonance in digital and non-digital learning environments: Does technology promotes cheating among middle school students? Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.074

Bol, T. (2020). Inequality in homeschooling during the Corona crisis in the Netherlands. First results from the LISS Panel. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hf32q

Bouville, M. (2010). Why is cheating wrong? Studies in Philosophy and Education, 29 (1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-009-9148-0

Bray, A., Byrne, P., & O’Kelly, M. (2020). A short instrument for measuring students’ confidence with ‘key skills’ (SICKS): Development, validation and initial results. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37 (June), 100700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100700

Chen, C. M., & Chen, F. Y. (2014). Enhancing digital reading performance with a collaborative reading annotation system. Computers and Education, 77, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.04.010

Cheng, Y. C., Hung, F. C., & Hsu, H. M. (2021). The relationship between academic dishonesty, ethical attitude and ethical climate: The evidence from Taiwan. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13 (21), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111615

Chiang, F. K., Zhu, D., & Yu, W. (2022). A systematic review of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning , 907–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12656