UW-Madison Libraries Teaching & Learning

Additional options.

- smartphone Call / Text

- voice_chat Consultation Appointment

- place Visit

- email Email

Chat with a Specific library

- Business Library Offline

- College Library (Undergraduate) Offline

- Ebling Library (Health Sciences) Offline

- Gender and Women's Studies Librarian Offline

- Information School Library (Information Studies) Offline

- Law Library (Law) Offline

- Memorial Library (Humanities & Social Sciences) Offline

- MERIT Library (Education) Offline

- Steenbock Library (Agricultural & Life Sciences, Engineering) Offline

- Ask a Librarian Hours & Policy

- Library Research Tutorials

Search the for Website expand_more Articles Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more Catalog Explore books, music, movies, and more Databases Locate databases by title and description Journals Find journal titles UWDC Discover digital collections, images, sound recordings, and more Website Find information on spaces, staff, services, and more

Language website search.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

- ASK a Librarian

- Library by Appointment

- Locations & Hours

- Resources by Subject

book Catalog Search

Search the physical and online collections at UW-Madison, UW System libraries, and the Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Available Online

- Print/Physical Items

- Limit to UW-Madison

- Advanced Search

- Browse by...

collections_bookmark Database Search

Find databases subscribed to by UW-Madison Libraries, searchable by title and description.

- Browse by Subject/Type

- Introductory Databases

- Top 10 Databases

article Journal Search

Find journal titles available online and in print.

- Browse by Subject / Title

- Citation Search

description Article Search

Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more.

- Scholarly (peer-reviewed)

- Open Access

- Library Databases

collections UW-Digital Collections Search

Discover digital objects and collections curated by the UW-Digital Collections Center .

- Browse Collections

- Browse UWDC Items

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- Email/Calendar

- Google Apps

- Loans & Requests

- Poster Printing

- Account Details

- Archives and Special Collections Requests

- Library Room Reservations

- Lesson 3: Fundamental Writing Skills

Literature Reviews in the Sciences

- Introduction

- Lesson 1: What is a Literature Review

- Lesson 2: Fundamental Research Skills

- Lesson 4: Resources

Composing the Review

It’s a common misconception that researching and writing a literature review is a straightforward process that starts with research and ends with writing. The reality is that research and writing are intertwined, often with one process informing and reinforcing the other. This chapter of the micro-course provides some guidance in how to approach writing as a recursive and integrated process that most effectively (and efficiently!) occurs along with your research.

A helpful analogy for thinking about the interconnected activities of researching and writing is that of a band performing music. While individual musicians in a band will sometimes play louder, and some musicians may stop playing their instruments during a song, the musicians all remain on stage together, building on and responding to one another. Similarly, while you may conduct more research or more writing at different points during your literature review process, the two activities are very much interrelated, building on each other and responding to each other. To try to conduct your research and write completely separately would be like playing only one instrument in a band at a time–it wouldn’t sound very cohesive.

Analogy: Literature Reviews as Playing in a Band

Open Band Analogy in a new window

Read sample literature reviews rhetorically

As you conduct your research, you will likely read many sources that model the same kind of literature review that you yourself are researching and writing. While your original intent in reading those sources is likely to learn from the studies’ content (e.g. their results and discussion), it will benefit you to re-read these articles rhetorically.

Reading rhetorically means paying attention to how a text is written—how it has been structured, how it presents its claims and analyses, how it employs transitional words and phrases to move from one idea to the next. You might also pay attention to an author’s stylistic choices, like the use of first-person pronouns, active and passive voice, or technical terminology.

Consider this notion: Reading sample literature reviews rhetorically constitutes a form of writing. It does! When you read to write you are likely composing thoughts and experimenting with organization in your head. That cognitive activity is crucial to building familiarity with the nebulous literature review genre, and it also helps to build an effective and efficient writing process that works for you.

Write informally along the way

Writing can (and should!) be folded into your research process. It’s not only a strategy for getting the writing process started earlier, but a means of deepening your thinking about your project.

You might, for instance, incorporate informal writing activities into your data collection and management by writing short summaries or critiques of sources as you read them (you may know this strategy as creating an “annotated bibliography”). Alternatively, you might fill out pre-made templates for your sources to ensure you record all the most important information (e.g. experimental methods used, populations studied), or you might annotate your sources directly by hand or electronically.

Click on the following headings to learn more about each of these informal writing strategies.

Informal Writing Strategies

How this strategy works:

In addition to tracking citation information for all your selected sources, an annotated bibliography collects short descriptions of each source in one space. In a document, spreadsheet, notebook, or citation manager , keep a running list of all the sources you intend to incorporate into your review. For each source, set aside some space to write a brief summary after you have read the source carefully. Your summary might be simply informative (i.e. identify the main argument or hypothesis, methods, major findings, and/or conclusions), or it might be evaluative as well (i.e. state why the source is interesting or useful for your review, or why it is not).

Why this strategy might be useful:

Taking the time to write short informative and/or evaluative summaries of your sources while you are researching can help you transition into the drafting stage later on. By making a record of your sources’ contents and your reactions to them, you make it less likely that you will need to go back and re-read many sources while drafting, and you might also start to gain a clearer idea of the overarching shape of your review.

You can find this information (and more!) in the Writing Center’s online Writer’s Handbook section on Annotated Bibliographies .

This strategy might be used by itself or in combination with writing summaries. To create a template, consider what will be the most important information for you to glean from your sources as you read them. Then, write short prompts for yourself in a document, spreadsheet, or notebook that will remind you to gather that information. Copy these prompts for each source, and write short responses to each prompt as you read. Here are some sample prompts you might incorporate into a note-taking template:

- Bibliographic information (author(s), title, journal, etc.):

- Purpose or aims of the study:

- Major claims, hypothesis, or argument:

- Main findings and issues raised in discussion (i.e. the major take-aways):

- What’s especially valuable about it? What are its limitations? How is it relevant to your project?

A note-taking template can help ensure that you gather information consistently across all the sources you collect, and can serve as a self-reminder to evaluate the usefulness and relevance of sources as your project progresses.

Annotating sources refers to the process of writing notes directly on your reading material (e.g. articles, patents, etc.). This might be done digitally, as when adding comments to a PDF document , or manually, as when writing on a print copy. Annotating a source is often used in combination with highlighting or other means of visually drawing attention to specific content. Importantly, annotations reflect your own ideas and reactions to the content of a source (as opposed to simply repeating what already appears in the text).

Annotating a source while reading it can deepen your engagement with its content—its ideas, arguments, methods, and findings. Be sure to consider whether digital or hard copy will be more accessible for you (e.g. is managing screen fatigue a priority for you?), as well as how you would like to be able search for and find your annotations at a later date.

Once you have done enough research that you feel you’re in a good position to begin drafting in earnest, it will be important to consider what the overall structure of your literature review will look like. As you know from previous lessons, the type and form of your review will dictate to a large degree the structure of your final product.

It will be important for you to find example literature reviews of the same type and form that you are writing so that you can get a sense of the specific expectations of that kind of review. If possible, you might look at specific examples that also target the same audience and pursue the same purposes as your own literature review. For example, you might find sample dissertation chapters written by peers with the same adviser as you; or you might find reviews published in the same journal that you’re submitting to.

With a clear sense of what the final product should look like, you might begin drafting your literature review in a number of ways. Some writers like to begin by outlining the different sections of the review, either in broad strokes or in specific detail. Other writers like to begin with a mind map of all their collected sources to help them envision relationships among them. Yet other writers like to begin with freewriting , which allows them to get ideas onto the page and deal with organization later.

Click on the following headings to learn more about each of these drafting strategies.

Drafting Strategies

Take the sources, ideas and connections you’ve generated and write them out in the order you might address first, second, third, etc. Use subpoints to create hierarchies of logic through which you might introduce specific groups or categories of sources. Maybe you want to identify specific conclusions or methodologies within the sources you might use. Maybe you want to keep your outline elements general. Do whatever is most useful to help you think through the sequence of your ideas. Remember that outlines can and should be revised as you continue to develop and refine the flow of your review.

Outlines emphasize the sequence and hierarchy of ideas—your main points and subpoints as represented by the sources you’ve selected. If you have identified several key ideas emerging from the literature you have reviewed, outlining can help you consider how to best guide your readers through these ideas. What do your readers need to understand first? Where might certain studies fit most naturally? These are the kinds of questions that an outline can clarify.

You can find this information (and more!) in the Writing Center’s online Writer’s Handbook section on Outlining .

This technique is a form of brainstorming that lets you visualize how your ideas function and relate. To get started, you might find a blank sheet of unlined paper or, for a larger work area, a whiteboard. You could also download software that lets you easily manipulate and group text, images, and shapes (like Coggle , FreeMind , or MindMaple ). Write down a central idea, then identify associated concepts, features, or questions around that idea. If some of those thoughts need expanding, continue this map, cluster, or web in whatever direction makes sense to you. Make lines attaching various ideas, or arrows to signify directional relationships. Add and rearrange individual elements or whole subsets as necessary. Use different shapes, sizes, or colors to indicate commonalities, sequences, or relative importance.

This drafting technique allows you to generate ideas while thinking visually about how they function together. As you follow lines of thought, you can see which ideas can be connected, where certain pathways lead, and what the scope of your project might look like. Additionally, by drawing out a map you may be able to see what elements of your review are underdeveloped and may benefit from more focused attention. It’s important to note that not all of the ideas or sources in your mind map would necessarily appear in the final draft.

You can find this information (and more!) in the Writing Center’s online Writer’s Handbook section on Mind Mapping .

Sit down and write without stopping for a set amount of time (i.e., 5-10 minutes). The goal is to generate a continuous, forward-moving flow of text, to track down all of your thoughts about each source, as if you are thinking on the page. Even if all you can think is, “I don’t know what to write,” or, “Is this important?” write that down and keep on writing. Repeat the same word or phrase over again if you need to. Write in full sentences or in phrases, whatever helps keep your thoughts flowing. Through this process, don’t worry about errors of any kind or gaps in logic. Don’t stop to reread or revise what you wrote. Let your words follow your thought process wherever it takes you.

The purpose of this technique is to open yourself up to the possibilities of your ideas while establishing a record of what those ideas are. Through the unhindered nature of this open process, you are freed to stumble into interesting options you might not have previously considered.

You can find this information (and more!) in the Writing Center’s online Writer’s Handbook section on Freewriting .

Depending on the kind of literature review you’re writing, the overarching structure can look quite different. For the purposes of this introductory micro-course though, let’s walk through a fairly common structure for narrative reviews—that is, reviews that typically feature a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

Each of these three sections has a specific rhetorical purpose. In other words, they are meant to do certain things:

Introduction

- Define the general topic, issue, or area

- Point out overall trends, conflicts, and gaps in the published literature

- Establish your point of view and the line of inquiry you’ll be pursuing

- Provide a “road map” of how your review will proceed

- Group studies according to common themes

- Paraphrase study findings and elaborate on their significance according to their relative importance

- Provide strong umbrella sentences, effective transitions, and brief “so what” summaries

Conclusion

- Summarize major contributions of significant studies to the body of knowledge under review

- Evaluate the current “state of the art” of the knowledge reviewed, noting flaws, gaps, inconsistencies, and areas for future study

- Provide some insight into the relationship between your central topic and a larger area of study

While you’re drafting, try to keep in mind the purpose of each section, and plan on spending a significant amount of time revising your document to ensure that each of these purposes is met.

As you might imagine, drafting and revising the body can be particularly labor-intensive! Consider breaking this component of your drafting into smaller, less intimidating tasks. For example:

- Develop categories for the sources you plan to include in your review

- Determine the order in which you’ll discuss your selected sources

- Background information 🡪 specific information

- Areas of consensus 🡪 areas of controversy

- Add section headings

- Include summative sentences at the conclusion of paragraphs (that is, clearly state why the sources addressed are important to your study)

Above all, allow yourself to engage in drafting as an ongoing (and often messy!) process. There is no one “correct” way to draft a literature review, and you may find that using different strategies at different stages will help you make progress toward the final product you’re aiming for.

Remember, writing is a cognitive process, so allow yourself to use the drafting process as a means of deepening and organizing your own thinking about your research. Revision, on the other hand, presents an opportunity to transform your writing from a thinking tool to a communication tool. In other words, revising is a process for considering how your target audience will experience your writing through its relative clarity and cohesion.

Just like drafting, there are multiple revising strategies you might explore, but generally speaking revision is most effective when it moves intentionally from global concerns to local concerns. Global concerns are whole-text issues that impact a reader’s overall experience of your piece. For example: Does it have a clear focus? Is it effectively organized? Local concerns are paragraph- or sentence-specific issues that impact a reader’s experience in particular areas. For example: Are there clear transitions? Could word choice be more precise? Are there proofreading errors?

Global concerns:

- Focus and relevance

- Unity and cohesion

- Clarity and organization

Local concerns:

- Paragraph-level (transitions, topic sentences)

- Sentence-level (tone and style, punctuation)

- Word-level (diction, spelling, grammar)

Once you’ve addressed the major global concerns in your draft and considered how your readers might experience navigating the document, you might take a final pass through your language—sentence by sentence—to fine-tune your style.

Some stylistic considerations:

- Objective tone

- Appropriately qualified language

- Limited quotations

- Appropriate use of active/passive voice

- No leisurely sentence openers

Click on the following headings to learn more about each revision strategy.

Revision Strategies

How this strategy works :

Reverse outlining is a process whereby you take away all of the supporting writing and are left with a paper’s main points or main ideas, sometimes represented by your paper’s topic sentences. Your reverse outline provides a bullet-point view of your literature review’s structure because you are looking only at the main points of the review in its current state.

Reverse outlining allows you to read a condensed version of what you wrote, and provides one good way to examine and produce a successful review. This strategy is particularly useful for large-scale revisions that tackle global concerns. It can help you determine if your literature review meets its goals, discover places to expand on your discussion of sources, and see where readers might be confused by your organization or structure.

You can find this information (and more!) in the Writing Center’s online Writer’s Handbook section on Reverse Outlining .

Editing for clarity and concision occurs most effectively toward the end of your writing process, after you have addressed any global concerns in the literature review. This requires re-reading each paragraph and each sentence carefully, considering how your language might communicate your ideas most effectively to your readers.

Every writer has quirks and inconsistencies in their writing, so the specific edits you make in your review will look different from other writers’ edits. The UW-Madison Writing Center’s online Writer’s Handbook features a section on improving your writing style that can guide you through a variety of editing procedures. For example, how to use active voice and how to avoid vague nouns .

Your literature review will undergo many drafts and revisions along the way, and this might easily lead to some chopped sentences, confusing grammar, and gaps in transitions. Editing—especially with the help of outside readers – can help ensure that you are communicating your ideas as clearly and effectively as possible.

Finally, don’t forget that talking about your writing with knowledgeable, engaged readers is an effective way to gain new perspectives, learn new strategies, and make progress toward your goals. Lesson 4 provides a list of resources (including outside readers like Writing Center instructors!) to support you in your research and writing.

Tips for Grads: Adding structure and avoiding time wasters in literature reviews

By Emily Azevedo-Casey, PhD student

Picking up from where we left off last week on the subtle essentials of research paper writing , let’s dive into writing literature reviews. It can be easy to get lost in the ocean of literature and stressful to both synthesize and critique scholarship, especially when you’re short on time. Here are some essential tips to help you avoid time wasters and provide structure so you can be proud of your next literature review.

- Clarify your purpose. Literature reviews generally explore the state of knowledge of a given field or topic. They put ideas in conversation with each other and ask researchers to add their perspective. Consider your purpose as you dive in and get support from your professors, mentors, and advisors for help in choosing a topic.

- Select your criteria. Choose about 10 keywords to search on your favorite literature database . Narrow your search results by adjusting the order of keywords you use and sorting results by time, relevance, and citations. Use citation managers to organize, store, and format your sources.

- Actively read to outline. Read with a pen in hand. Try strategies like annotating as you go and writing critical summaries. Next, organize how the scholarship fits with your topic based on time, events, or themes. This part of the process can be the most fun, so find ways to enjoy it or get creative. Use mindmaps to help develop your argument by connecting similar and different ideas to the main points you want to make. Following that, your outline practically organizes itself!

- Write then edit. If you struggle with constant revising during the early drafting stages like me, try setting specific time aside to revise after you write a complete idea or for a set amount of time. Use resources like The Writing Center or having a friend look at your work. You can also use course rubrics to grade yourself!

There are so many resources out there to help you complete your literature review so do your research and take advantage. This piece drew from the UW-Libraries mini-course on writing literature reviews in the sciences , this article with samples from The Writing Center’s handbook, and a great Youtuber Dr. Amina Yonis who has several videos on the subject.

Tips for Grads is a professional and academic advice column written by graduate students for graduate students at UW–Madison. It is published in the student newsletter, GradConnections Weekly.

- Facebook Logo

- Twitter Logo

- Linkedin Logo

– For Students

The University of Wisconsin-Madison offers a variety of writing support for students of all ages and writing levels — not only undergraduates and graduate students, but also K-12 students. Below is a guide to some of the services offered by our core CTRW programs and our affiliate programs.

Graduate Students

Graduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have a lot of writing in their lives, and the CTRW is here to help. Whether it’s getting your research in line, or maybe some writing in your course, or for something else in your life, or maybe you want to get involved with writing in your discipline/community, there are opportunities to do so, including some of the following:

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Writing Center

The world-renown, award-winning Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison supports undergraduate students working on all kinds of writing projects. Below are some quick links to program resources:

- Schedule in-person or remote appointments with consultants

- Get written feedback on your writing , register for in-person and asynchronous workshops

- Find online and in-person writing once- or bi-weekly mentorships

- Connect with writing groups

- Review the UW-Madison Writer’s Handbook

- Find a writing event

- Contact a writing specialist

English as a Second Language (ESL) Program

The English as a Second Language (ESL) Program is here to help international students. We have developed several teacher training programs for ESL teachers in Italy, China, Korea and Turkey, and the ESL program has also collaborated with Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan and Universidad Tecnológica in Uruguay to develop a writing program for their undergraduate students. Our highly talented and dedicated instructors have many years of teaching experience here and abroad, and our teaching faculty help run the many programs and courses that we offer.

- International graduate students with a TOEFL score below 93 on the iBt or below 580 on the paper-based TOEFL must take the Madison ESL Assessment Test (MSN-ESLAT) upon arrival. Some departments require the MSN-ESLAT regardless of TOEFL score. Graduate students should enroll in the recommended ESL course in their first semester based on the recommendation determined by their MSN-ESLAT test. Taking the recommended course will fulfill the ESL requirement for most students. Students may wish to work further on their English. People who want to enroll in ESL 344 (Graduate Academic Presentations), 345 (Pronunciation for International Grad Students, 349 (Writing for International Grad Students) or 350 (Professional and Academic Writing Skills) may do so without taking the MSN-ESLAT. See Course Descriptions for Academic Classes to find out if one of these classes meets your needs.

- Find out about placement

- Read more about ESL courses offered and course learning outcomes

- Finding testing information (MSN-ESLAT, SPEAK, IELTS, TOEFL)

- Read about our teaching faculty

- Read about our senior lecturers

- Find a tutor

- Become a teacher (TESOL certification)

- Read frequently asked questions

- Visit the virtual front desk on Zoom

- Contact the program

"Who We Are - Voices in Our Community" Program

The Who We Are – Voices in Our Community Program is award-winning program brings together children and youth experiencing homelessness with local educators and University of Wisconsin-Madison students to support the young people in sharing their stories in a supportive and caring environment.

Language Institute and Second Language Acquisition (SLA) Programs

Our affiliate program, the Language Institute maintains Languages at UW-Madison , a website devoted to undergraduate language study. The site provides information on languages that UW-Madison student can study, publicizes news and events of interest to undergraduate language students, hosts a growing set of alumni profiles, and illustrates the many ways that language study can enrich every student’s Wisconsin Experience.

The Language Institute also administers the Doctoral Program in Second Language Acquisition (SLA), an interdisciplinary program that prepares students to research and teach in a rapidly growing field that investigates second language learning and acquisition, bi- and multilingualism, second and foreign language teaching, and the relationship among language, culture, identity and thought in diverse social contexts.

Research Fellowships

Researchers should check out our CTRW fellowship opportunities .

Teaching Assistantships

Interested in teaching writing at the university? Contact us .

Undergraduates Students

Undergraduates students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison do a lot of writing, and the CTRW wants to make sure undergrads are connected with all the support and resources that they need and that available to them at the university. We aim to help writers of all types. Fulfill a writing requirements (Communication-A or -B requirement, Madison ESL Assessment Test, or other). Get professional eyes on some writing from another class (like an essay, report, or paper of some type). Talk to some about whatever writing for life (like an letter, application, résumé, etc.). Get involved with writing communities (disciplinary, professional, social, and/or other). And more. Regardless of how you relate to writing, there are a variety of programs at the university that offer opportunities to fulfill your writing goals and objectives, including some of the following CTRW-supported programs.

- Schedule in-person or remote appointments with consultants (see also E100 and ESL programs for consulting services)

English 100 Program (Comm-A)

English 100 program.

The English 100 Program (E100) offers students an introduction to college composition that helps them prepare for the demands of writing at UW-Madison and also helps them think about writing beyond the classroom. The course satisfies the Communication-A general education requirement for undergraduates.

- E100 is designed to build rhetorical awareness in both written and oral communication. Assignments engage questions of audience, purpose, genre, discourse conventions, and research methods. Students use narrative strategies to explore abstract concepts; summarize and synthesize information; engage in conversations with the ideas of others; and construct arguments through original research. The course views writing as an act of inquiry, a means of communication, and a process. With this in mind, instructors emphasize drafting, revising, and editing as critical practices.

- If you’re an E100 student, you have access to the E100 Tutorial Program .

- If you’re interested in publishing your writing, there are occasional opportunities for students to publish on the E100 CompPost Blog .

- For more in-depth information on E100, see also the open-access E100 Course Readings , which include not only a comprehensive description of E100, but also provide examples of award-winning writing from professionals and students alike.

English 201 Program (Comm-B)

English 201 program.

The English 201 Program (E201) is a an intermediate-level writing course that satisfies the university’s Communication-B requirement for enhancing students’ literacy skills. Enrollment in E201 assumes that a student has successfully completed or been exempted from the Communication-A requirement.

- This course is couched at an intermediate skill level and has more experienced students (not being open to freshmen and requiring 3 credits of introductory literature as a prerequisite) and more challenging assignments, typically involving sophisticated readings, complex writing tasks, and very high expectations for student inquiry.

- Each section of the course treats a single issue, problem, or theme (or set of issues, problems, or themes) in depth, giving students the opportunity not just to work on general processes of reading and writing but to be initiated into the complex discursive practices of a particular literate community struggling with particular intellectual, cultural, and practical problems.

- E201 sections will vary from teacher to teacher.

Writing Fellows Program

Do you have a passion for writing in your discipline? Are you interested in helping others with their writing? Thinking of getting into teaching and learning about pedagogy? The Writing Fellows Program might be a great fit for you. Writing Fellows represent a wide range of majors, including sociology, political science, English, philosophy, molecular biology, physics, and history, and the program is always on the lookout for fellows.

Writing Fellows enroll in English 403, a three-credit honors seminar in the fall semester on tutoring writing across the curriculum taught. In the course, Fellows study writing in both practical and theoretical terms, not just as a way of thinking, but also as a means of communicating with others and as a practice that varies across disciplines and across social and cultural conditions.

- Read more about the program

- Apply to become a Writing Fellow

- Find all the info you need to get started

- Most new and transferring international undergrads are required to take the Madison ESL Assessment Test (MSN-ESLAT) and enroll in the recommended ESL courses until they have completed English 118. English 118 fulfills the Communication-A requirement for undergraduates. After a student has taken an ESL course, instructors re-evaluate the student’s English language proficiency and recommend further ESL courses as needed. It is not necessary to take all the courses in the ESL sequence of 114, 115, 116, 117 and 118. Students may move from 115 directly to 117, for example.

Language Institute and Second Language Acquisition (SLA) Program

Our affiliate program, the Language Institute maintains Languages at UW-Madison , a website devoted to undergraduate language study. The site provides information on languages that UW-Madison student can study, publicizes news and events of interest to undergraduate language students, hosts a growing set of alumni profiles, and illustrates the many ways that language study can enrich every student’s Wisconsin Experience. There is also programming and academic and career advising for bi/multilingual students on campus to support them in connecting their language abilities with their personal, academic, and career goals

Business Communication Program

If you’re a majoring in business, our affiliate program, the Wisconsin School of Business has communication classes specifically devoted to professional communication:

- General Business 360 – Workplace Writing and Communication: GenBus360, a required course in communication for all BBA students; fulfills UW’s General Education Communication B requirement. Students in GenBus 360 learn general workplace communication skills and explore specific communication practices in their future careers through individual research. Students develop their writing skills during the semester through a workshop process, which provides opportunities for students to develop skills in giving, receiving, and incorporating constructive criticism, while continuously revising their own written work. Additionally, students receive guidance and practice developing listening skills throughout the course and deliver formal and informal presentations. Instructors collaborate on designing assignments, developing activities, and improving all aspects of the course. Sections share common assignments, course policies, major due dates, and learning outcomes, and use common rubrics. At the end of the semester, one third of each student’s final grade is determined through a blind grading process, where instructors grade portfolios submitted by students they did not teach. Blind portfolio grading mimics a common workplace situation where the ultimate audience for written work may be unknown. In addition, blind grading ensures that students are evaluated only on the basis of the assignment criteria. In general, blind grading is recognized as a fair process used extensively in U.S. law schools.

- General Business 320 – Intercultural Communication in Business: GenBus320, a popular elective focused on cross-cultural communication. Students in Intercultural Communication in Business develop stronger cultural competence by applying models of cross-cultural communication theory. This theory helps them become flexible, reflective, and strategic communicators who can work effectively with diverse groups and individuals. The course structure emphasizes case studies, simulations, written reflections, structured discussion and dialogue, short lectures, practical research assignments, and student-led presentations.

Technical Communication Program

Our affiliate program, the Instructors in Technical Communication Program teaches the major communication courses for undergraduate students in the College of Engineering. The Engineering Communication course (InterEGR 397) meets the University’s General Education (Comm-B) requirement and several engineering departmental requirements. A second course in Technical Presentations (EPD 275) is required by some undergraduate programs. Beyond these requirements, engineering and other undergraduate students from all disciplines may choose to earn the Technical Communication Certificate, which functions like a minor and further enhances their professional communication skills. The mission and learning objectives for the full Technical Communication program may be found here.

K-12 students

Whether you’re a budding novelist, a promising young journalist, a future scientist, or something else entirely, the Greater Madison Writing Project (GMWP) likely has something for you! Below are some of what the GMWP offers:

Young Writers Camps

Young Writers Camps are creative, inspiring, and supportive summer camps for young writers entering grades 3-8. Participants write daily led by GMWP Fellows and experienced teachers of writing. Camp ends with a celebration of writing!

High School Writers Camps

High School Writers Camps are four-day camps for high school writers that support a creative and engaging writing experience. Engage in the writing process, meet guest writers, and contribute a group anthology! Camp ends with a celebration of writing for family and friends.

Graphic Novel Camp

KaBOOM!!! If you love graphic novels — and are a motivated artist who wants to draw all week— then Graphic Novel Camp is for you! BAM!!! Draw your own characters that tell compelling stories with images to create your own graphic novel. OH YEAH, ZAP!!

Rise Up & Write

Rise Up & Write is a youth advocacy writing summer camp for high school students. Rise Up & Write provides youth with the opportunity to use writing as a way to raise awareness and create change.

Youth Press Corps

Calling all future journalists! Join the Youth Press Corps to learn from experienced journalists, cover issues that matter to you, and publish your story!

UW-Madison Libraries

Next available on Sunday 2–10 p.m.

Additional Options

- smartphone Call / Text

- voice_chat Consultation Appointment

- place Visit

- email Email

Chat with a Specific library

- Business Library Business Library Chat is Offline

- College Library (Undergraduate) College Library Chat is Offline

- Ebling Library (Health Sciences) Ebling Library Chat is Offline

- Gender and Women's Studies Librarian GWS Library Chat is Offline

- Information School Library (Information Studies) iSchool Library Chat is Offline

- Law Library (Law) Law Library Chat is Offline

- Memorial Library (Humanities & Social Sciences) Memorial Library Chat is Offline

- MERIT Library (Education) MERIT Library Chat is Offline

- Steenbock Library (Agricultural & Life Sciences, Engineering) Steenbock Library Chat is Offline

- Ask a Librarian Hours & Policy

- Library Research Tutorials

Search the for Website expand_more Articles Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more Catalog Explore books, music, movies, and more Databases Locate databases by title and description Journals Find journal titles UWDC Discover digital collections, images, sound recordings, and more Website Find information on spaces, staff, services, and more

Language website search.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

- ASK a Librarian

- Library by Appointment

- Locations & Hours

- Resources by Subject

book Catalog Search

Search the physical and online collections at UW-Madison, UW System libraries, and the Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Available Online

- Print/Physical Items

- Limit to UW-Madison

- Advanced Search

- Browse by...

collections_bookmark Database Search

Find databases subscribed to by UW-Madison Libraries, searchable by title and description.

- Browse by Subject/Type

- Introductory Databases

- Top 10 Databases

article Journal Search

Find journal titles available online and in print.

- Browse by Subject / Title

- Citation Search

description Article Search

Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more.

- Scholarly (peer-reviewed)

- Open Access

- Library Databases

collections UW Digital Collections Search

Discover digital objects and collections curated by the UW-Digital Collections Center .

- Browse Collections

- Browse UWDC Items

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- Email/Calendar

- Google Apps

- Loans & Requests

- Poster Printing

- Account Details

- Archives and Special Collections Requests

- Library Room Reservations

Literature Reviews in the Sciences Micro-course

The Science & Engineering Libraries, in collaboration with The Writing Center, developed an asynchronous, interactive micro-course based on the content of a highly attended in-person workshop, co-taught between the UW Libraries and the UW Writing Center.

This micro-course enables residential and online students to access the content whenever and wherever it is convenient for them to engage, or re-engage, with the topic. Access to this instruction is no longer limited to when the librarian and writing instructor are able to coordinate schedules. This micro-course explores the skills and tools necessary to research and write a literature review in the sciences, including planning, organization, disciplinary-based source exploration, drafting, and revision. The content for this micro-course was developed by Barb Sisolak (on behalf of the Libraries) and Angela Zito (on behalf of the UW-Madison Writing Center), with Jules Arendsdorf (Teaching & Learning Programs E-Learning Team) assisting with instructional design. Additional contact: Angela Zito, UW Writing Center ( [email protected] )

- Value: Empowerment/Encourage experimentation and creativity

- Value: Empowerment/Allow for flexibility in how staff and managers work

- Value: Collaboration/Leverage the expertise of library staff

Strategic Directions

- Experiment with instructional models

- Strengthen the online student experience

- Collaboration

- Empowerment

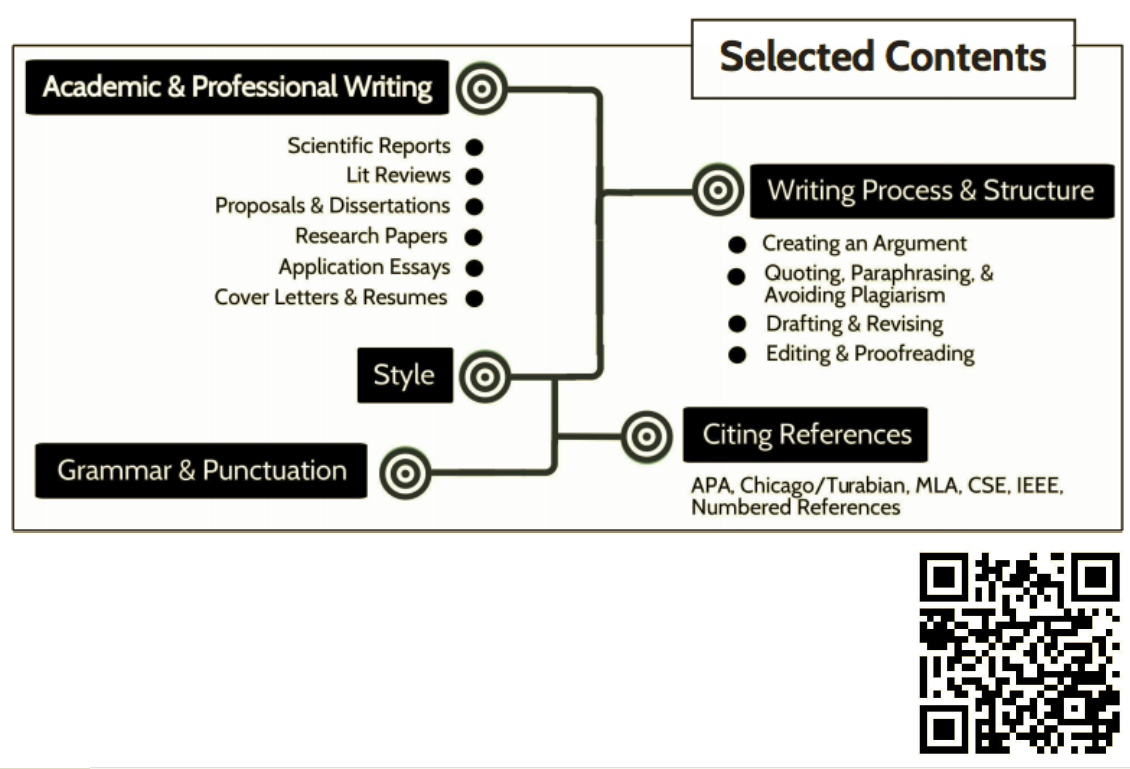

THE UW-MADISON WRITING CENTER’S ONLINE HANDBOOK

Available through the UW–Madison Writing Center’s website, the UW–Madison Writer’s Handbook is a reference guide designed for academic and professional writing. Drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors every month, the Writer’s Handbook provides over 100 pages of high-quality instructional material for undergraduate and graduate students in all disciplines.

The Writing Center hopes that these materials can help you integrate writing instruction tailored to particular assignments in your courses. With information about a number of common genres of writing and expert advice for approaching various stages of the writing process, these resource materials offer writers at all levels general guidelines, sample papers, and recommended strategies for approaching the writing process.

If you have ideas or requests for new topics to add to the Writer’s Handbook, please feel free to suggest those to the Director of the Writing Center, Brad Hughes, [email protected].

The Madison Review

The Madison Review is an independent literary arts journal published through the University of Wisconsin–Madison Creative Writing Department. Published semiannually, each issue of The Madison Review contains previously unpublished fiction, poetry, and art as well as interviews with well-known writers. The Madison Review is also committed to bringing literary arts to the community by hosting readings, discussions and other events. Contributors to The Madison Review have included I.B. Singer, Stephen Dunn, Lisel Mueller, May Sarton, Charles Baxter, Roberto Fernandez, and C.K. Williams. The Madison Review has also had the privilege of interviewing such literary figures as Joe Meno, Billy Collins, Maurice Manning, Bret Easton Ellis, Chuck Palahniuk, David Sedaris, Lorrie Moore, Dean Young, Ira Glass, Nathan Englander, Heather Swan, and Amy Quan Barry.

Founded in the early 1970s by students from the university’s creative writing program, The Madison Review remains a student-run journal to this day. The staff—including editors—is composed entirely of undergraduates from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since the staff changes frequently, each issue attempts to showcase the distinct aesthetics of that year’s reviewing panel. Professor Ron Kuka has acted as the faculty advisor for The Madison Review since 1990.

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

Library Science: Lit Review

- Evaluating Sources

- Choose a Topic

- Gov Docs This link opens in a new window

- Careers in LIS

- APA Citation

Literature Reviews

You may be asked to write a literature review as part of your Library Science coursework.

On this page, you will find:

- Tutorial videos on the topic of literature review (left column)

- A definition of a literature review (right column)

- Links to helpful tools to help you write a lit review (right column)

- Outline of a basic literature review (right column)

The Literature Review

This tutorial from NCSU gives a good overview of the process of the literature review.

Types of Literature Reviews

Completing Literature Reviews

What is a Literature Review (Lit Review)?

A Literature Review is an integrated summary of existing research on a particular topic. In it, you identify sources, summarize their points, and then critically evaluate them as they relate to each other. You also need to establish that the existing research has not yet covered the aspect of the topic that you are or will be researching. Aspects of the topic that need further research or which are controversial should be identified, as well.

Links to Further Help You...

- Purdue Online Writing Lab Social Work Literature Review Guidelines (Not only for Social Work!)

- UW-Madison Writing Center Learn How to Write a Review of Literature

- Mindmap The Literature Review in Under 5 Minutes

Basic Outline

Detailed literature reviews typically include the following:

- Introduction : Explain how you will organize your literature review (e.g. thematic or chronological) and your thesis (argument).

- Body : Summarize, compare, contrast, etc. the various sources and their arguments. Discuss your thesis in relation to the existing research. Identify the gaps that led to your thesis and those that remain.

- Implications : State how your research impacts the field.

- << Previous: Gov Docs

- Next: Careers in LIS >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2023 1:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/library_science

Next available on Sunday 2–10 p.m.

Additional Options

- smartphone Call / Text

- voice_chat Consultation Appointment

- place Visit

- email Email

Chat with a Specific library

- Business Library Offline

- College Library (Undergraduate) Offline

- Ebling Library (Health Sciences) Offline

- Gender and Women's Studies Librarian Offline

- Information School Library (Information Studies) Offline

- Law Library (Law) Offline

- Memorial Library (Humanities & Social Sciences) Offline

- MERIT Library (Education) Offline

- Steenbock Library (Agricultural & Life Sciences, Engineering) Offline

- Ask a Librarian Hours & Policy

- Library Research Tutorials

Search the for Website expand_more Articles Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more Catalog Explore books, music, movies, and more Databases Locate databases by title and description Journals Find journal titles UWDC Discover digital collections, images, sound recordings, and more Website Find information on spaces, staff, services, and more

Language website search.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

- ASK a Librarian

- Library by Appointment

- Locations & Hours

- Resources by Subject

book Catalog Search

Search the physical and online collections at UW-Madison, UW System libraries, and the Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Available Online

- Print/Physical Items

- Limit to UW-Madison

- Advanced Search

- Browse by...

collections_bookmark Database Search

Find databases subscribed to by UW-Madison Libraries, searchable by title and description.

- Browse by Subject/Type

- Introductory Databases

- Top 10 Databases

article Journal Search

Find journal titles available online and in print.

- Browse by Subject / Title

- Citation Search

description Article Search

Find articles in journals, magazines, newspapers, and more.

- Scholarly (peer-reviewed)

- Open Access

- Library Databases

collections UW Digital Collections Search

Discover digital objects and collections curated by the UW Digital Collections Center .

- Browse Collections

- Browse UWDC Items

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- Email/Calendar

- Google Apps

- Loans & Requests

- Poster Printing

- Account Details

- Archives and Special Collections Requests

- Library Room Reservations

Search the UW-Madison Libraries

Catalog search.

Writing literature reviews : a guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

- language View Online

- format_quote Citation

Publication Details

- Galvan, Melisa C

- 7th edition

- New York : Taylor and Francis, 2017

- 1 online resource (xix, 288 pages)

- Description based upon print version of record.

- Step 4: Organize Yourself before Reading the Articles

- Includes bibliographical references and index.

- Cover; Title Page; Copyright Page; Dedication; Table of Contents; Preface; Audiences; Unique Features; New to This Edition; Ancillaries; Notes to the Instructor; Special Acknowledgment; Acknowledgments; Notes; Part I: Managing the Literature Search; 1 Writing Reviews of Academic Literature: An Overview; An Introduction to Reviewing Primary Sources; Empirical Research Reports; Theoretical Articles; Literature Review Articles; Anecdotal Reports; Reports on Professional Practices and Standards; The Writing Process; Finding Your 'Writer's Voice': Writing for a Specific Purpose

- Writing a Literature Review as a Term Paper for a ClassWriting a Literature Review Chapter for a Thesis or Dissertation; Writing a Literature Review for a Research Article; The Parts of this Text; Managing the Literature Search-Part I; Analyzing the Relevant Literature-Part II; Writing the First Draft of Your Literature Review-Part III; Editing and Preparing the Final Draft of Your Review-Part IV; Activities for Chapter 1; Notes; 2 Learn to Navigate the Electronic Resources in Your University's Library; Step 1: Formalize Your Institutional Affiliation with Your University Library

- Step 2: Set Up Your Online Access Credentials and/or Proxy ServerStep 3: Inquire about University Library Research Workshops; Step 4: Select a Search Engine that Best Suits Your Needs; Step 5: Familiarize Yourself with How Online Databases Function; Step 6: Experiment with the "Advanced Search" Feature; Step 7: Identify an Array of Subject Keywords to Locate Your Sources; Step 8: Learn How You Can Access the Articles You Choose; Step 9: Identify Additional Databases that May Be Useful for Your Field of Study; Step 10: Repeat the Search Procedures with Other Databases; Activities for Chapter 2

- Note3 Selecting a Topic for Your Review; Step 1: Define Your General Topic; Step 2: Familiarize Yourself with the Basic Organization of Your Selected Online Database; Step 3: Begin Your Search with a General Keyword, then Limit the Output; Step 4: Identify Narrower Topic Areas If Your Initial List of Search Results Is Too Long; Step 5: Increase the Size of Your Reference List, If Necessary; Step 6: Consider Searching for Unpublished Studies; Step 7: Start with the Most Current Research, and Work Backward; Step 8: Search for Theoretical Articles on Your Topic; Step 9: Look for Review Articles

- Step 10: Identify the Landmark or Classic Studies and TheoristsStep 11: Assemble the Collection of Sources You Plan to Include in Your Review; Step 12: Write the First Draft of Your Topic Statement; Step 13: Redefine Your Topic More Narrowly; Step 14: Ask for Feedback from Your Instructor or Advisor; Activities for Chapter 3; Notes; 4 Organizing Yourself to Begin the Selection of Relevant Titles; Step 1: Scan the Articles to Get an Overview of Each One; Step 2: Based on Your Prereading of the Articles, Group Them by Category; Step 3: Conduct a More Focused Literature Search if Gaps Appear

Additional Information

Information from the web, library staff details, keyboard shortcuts, available anywhere, available in search results.

Communication-B & Writing-Intensive Criteria and Courses

Requirements for Writing-Intensive Courses

Guidelines for writing-intensive courses.

Writing-Intensive (WI) courses in the College of Letters and Science incorporate frequent writing assignments in ways that help students learn both the subject matter of the courses and discipline-specific ways of thinking and writing. Generally, WI courses are at the intermediate or advanced level and are designed specifically for majors. Please note that writing-intensive courses are in L&S departments only, and that writing-intensive courses are different from the Bascom or Communication-B courses which will satisfy Part B of the university-wide general education communication requirements. For more information about Communication-B courses, please contact the chair of the implementation committee for those courses: Professor Nancy Westphal-Johnson, [email protected].

In most semesters, there are between 70 and 100 courses in over 30 different L&S departments designated as writing-intensive. In October 1999, the L&S Faculty Senate passed legislation recommending that all L&S departments develop enough writing-intensive courses so that all of their majors would take at least one as part of their undergraduate studies. Both the L&S curriculum committee and Faculty Senate felt strongly that the writing skills students learn in Communication-A and -B courses should be further developed, nurtured, and practiced in subsequent, more advanced writing-intensive courses.

The procedure for designating a course as writing-intensive is simple. As long as you feel that the course will meet the writing-intensive guidelines outlined below, please go ahead and list it as writing-intensive.

All you need to do is:

- Ask the person in your department responsible for preparing the Timetable to add a footnote to your course listing. Standard Note Number 0003 is for a “Writing-Intensive Course.”

- Send Brad Hughes, the director of the L&S Program in Writing Across the Curriculum, a note or email message (English Department, Helen C. White Hall, [email protected]) letting him know which course you’re designating as writing-intensive.

- If you have questions about writing-intensive courses or would like advice about designing assignments and a syllabus for a WI course, please contact Brad Hughes, director of the L&S Program in Writing Across the Curriculum (3-3823, [email protected]). Please also explore the sample syllabi and assignments available in this sourcebook.

Strong Recommendations

- Departments may wish to limit enrollment to 30 or fewer students per instructor.

- The course syllabus should explain the writing-intensive nature of the course and should contain a schedule for writing assignments and revisions.

- Assignments should follow a logical sequence and should match the learning goals for the course. Among the many options: assignments can move from more basic to more sophisticated kinds of thinking about course material; assignments can move from clearly defined problems toward more ill-defined problems for students to solve; assignments can move from familiar to new perspectives on course material; assignments can give students repeated practice that builds particular thinking and writing skills; complex assignments can be sequenced–students write proposals for research, write drafts, receive feedback on drafts, and then revise their papers.

- Assignments should include time for students to prepare to write and time for them to reflect on their writing. Courses should include some informal, ungraded writing (such as journals, freewriting, reading logs, questions, proposals, response papers . . .) in order to encourage regular practice with writing, to help students reflect on and synthesize course material, and to provide opportunities for students to discover promising ideas for formal papers.

- Students should receive detailed written instructions for each writing assignment, including an explanation of the goals and specific evaluation criteria for that assignment.

- Instructors should require students to keep all of their writing in portfolios and to submit their past writing with new papers, so that instructors can gauge and guide students’ improvement as writers.

- Instructors should hold at least one individual conference with each student.

- Instructors should have students complete midterm and final evaluations of the writing component of the course.

- Instructors should consult with the staff of the L&S Program in Writing Across the Curriculum about the design of the writing component of their courses.

Models to Illustrate Number of Assignments and Number of Pages of Writing in Writing-Intensive Courses

- one 3-page paper, with draft and revision

- one longer paper, c. 10 pages, with a proposal, draft, and revision

- one 3-page paper

- two 2-page papers, one of which is revised

- two 6-page papers, one of which is revised

- two 8-page papers, each with a draft and revision

- five 1-page response papers

- one 10-page paper, with a draft; developed from one of the response papers

- two 5-page papers, one revised

- a graded journal

- one 5 or 6-page paper, which is revised

- one 5-page take-home midterm

- one 5 or 6-page paper

- two 2-page papers

- one 5-page group project report

- one 5-page paper, with draft and revision

- one 20-25-page paper, with proposal, draft, and revision

UW-Madison WAC Sourcebook 2020 Copyright © by UW-Madison Writing Across the Curriculum Program. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

University Library

Robert S. Swanson Library and Learning Center

Graduate Student Library Guide: Literature Review

- Introduction

- Find Dissertations

- Theses@Stout

- Thesis Only Grads

Literature Review

- Research Methods

- Data Analysis

- Writing and Citing

- Citation Builders

- Library Access for Alumni This link opens in a new window

- LibKey: Easy Access to Library Articles This link opens in a new window

Graduate Student Library Guide

Literature review description.

1. Introduction

Not to be confused with a book review, a literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources (e.g. dissertations, conference proceedings) relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, providing a description, summary, and critical evaluation of each work. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

2. Components

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Literature reviews should comprise the following elements:

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review

- Division of works under review into categories (e.g. those in support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative theses entirely)

- Explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

In assessing each piece, consideration should be given to:

- Provenance—What are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity—Is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness—Which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value—Are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

3. Definition and Use/Purpose

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

The literature review itself, however, does not present new primary scholarship.

4. Examples of Literature Reviews

An annotated example of a literature review may be found:

https://writingcenter.ashford.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Sample%20Literature%20Review_0.pdf

Find a published, peer-reviewed literature review by searching Search @UW for the following:

Raheel, H., Karim, M. S., Saleem, S., & Bharwani, S. (2012). Information and Communication Technology Use and Economic Growth. Plos ONE, 7 (11), 1-7.

5. For more information:

The University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center. (2009). Writer's Handbook: Common Writing Assignments: Review of Literature . Madison, Wisconsin: Author. Retrieved 20th of February 2020 from the World Wide Web: https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/reviewofliterature/

- Find a Database for Articles By name, subject or vendor (i.e. Ebsco, ProQuest)

- Research Guides Databases and resources organized by subject disciplines. Advise students to begin research here. Request resources or links be added to a specific guide - contact Laura Tomcik.

- Statistical and Demographic Resources Guide with resources for finding statistics and demographics.

- << Previous: Thesis Only Grads

- Next: Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://library.uwstout.edu/GradResearch

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A review is a required part of grant and research proposals and often a chapter in theses and dissertations. Generally, the purpose of a review is to analyze critically a segment of a published body of knowledge through summary, classification, and comparison of prior research studies, reviews of literature, and theoretical articles.

To write a good critical review, you will have to engage in the mental processes of analyzing (taking apart) the work-deciding what its major components are and determining how these parts (i.e., paragraphs, sections, or chapters) contribute to the work as a whole. Analyzing the work will help you focus on how and why the author makes certain ...

It's a common misconception that researching and writing a literature review is a straightforward process that starts with research and ends with writing. The reality is that research and writing are intertwined, often with one process informing and reinforcing the other. ... The UW-Madison Writing Center's online Writer's Handbook ...

This piece drew from the UW-Libraries mini-course on writing literature reviews in the sciences, this article with samples from The Writing Center's handbook, and a great Youtuber Dr. Amina Yonis who has several videos on the subject.

Writing Center. The world-renown, award-winning Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison supports undergraduate students working on all kinds of writing projects. Below are some quick links to program resources: Schedule in-person or remote appointments with consultants. Get written feedback on your writing, register for in-person ...

This micro-course explores the skills and tools necessary to research and write a literature review in the sciences, including planning, organization, disciplinary-based source exploration, drafting, and revision. ... (on behalf of the UW-Madison Writing Center), with Jules Arendsdorf (Teaching & Learning Programs E-Learning Team) assisting ...

Posted on July 23, 2019. Available through the UW-Madison Writing Center's website, the UW-Madison Writer's Handbook is a reference guide designed for academic and professional writing. Drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors every month, the Writer's Handbook provides over 100 pages of high-quality instructional material for ...

The UW-Madison Writing Center, which opened in 1969, has a staff of approximately 110, including ... literature reviews, Peace Corps application essays, Teach-for-America applications, blogs, cover letters for academic positions, writing with Scrivener. . . .

by The University of Wisconsin @ Madison Writing Center and is a section of their Writing Handbook. Gives detailed steps for writing a literature review -- introduction, writing the body and conclusion. The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting It.

The Madison Review is an independent literary arts journal published through the University of Wisconsin-Madison Creative Writing Department. Published semiannually, each issue of The Madison Review contains previously unpublished fiction, poetry, and art as well as interviews with well-known writers. The Madison Review is also committed to bringing literary arts to the community by hosting…

_Review of Literature_ UW-Madison Writing Center Writer's Handbook - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. _Review of Literature_ UW-Madison Writing Center Writer's Handbook

Online—reference materials and podcasts about academic writing; about short student drafts; online consultations using skype and google docs For more information . . . Tour our website—writing.wisc.edu/ Contact our co-director— Emily Hall [email protected], 608.263.3823 The Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

The Literature Review in Under 5 Minutes. Introduction: Explain how you will organize your literature review (e.g. thematic or chronological) and your thesis (argument). Body: Summarize, compare, contrast, etc. the various sources and their arguments. Discuss your thesis in relation to the existing research. Identify the gaps that led to your ...

Search the physical and online collections at UW-Madison, UW System libraries, and the Wisconsin Historical Society. ... Discover digital objects and collections curated by the UW Digital Collections Center. keyboard_arrow_down. Submit. Browse Collections ... Writing a Literature Review as a Term Paper for a ClassWriting a Literature Review ...

Brad Hughes Director, Writing Across the Curriculum Director, Writing Center Department of English 6187F H. C. White Hall 600 North Park St. Elisabeth Miller Assistant Director, WAC Department of English 600 North Park St. [email protected]. 608.263.3823 [email protected].

University of Wisconsin - Madison. Search. Menu. For Students. Make a Writing Appointment; Workshops ... Writing Literature Reviews of Published Research. Writing Literature Reviews of Published Research. ... Writing Center 6172 Helen C White Hall 600 North Park Street, Madison, WI 53706 ...

Strong Recommendations. Departments may wish to limit enrollment to 30 or fewer students per instructor. The course syllabus should explain the writing-intensive nature of the course and should contain a schedule for writing assignments and revisions. Assignments should follow a logical sequence and should match the learning goals for the course.

Robert S. Swanson Library and Learning Center. Textbooks Archives. Today's Hours: Library; ... The University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center. (2009). Writer's Handbook: Common Writing Assignments: Review of Literature. Madison, Wisconsin: Author. Retrieved 20th of February 2020 from the World Wide Web: https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook ...