What Wealth Inequality in America Looks Like: Key Facts & Figures

For an updated analysis of wealth inequality in the U.S., see U.S. Wealth Inequality: Gaps Remain Despite Widespread Wealth Gains , which was published Feb. 7, 2024.

The following charts help to illustrate the state of wealth inequality in America.

The St. Louis Fed’s Center for Household Financial Stability looks at the relationship between wealth and different demographic characteristics: race or ethnicity, education, and age or birth year. We believe this demographic lens is more informative than looking at wealth by income bands, because while income can (and frequently does) change from year to year, demographics are more stable.

We find that families who are thriving tend to be white, college-educated and/or older. We find that families who are struggling tend to have one or more of these characteristics: black or Hispanic; no four-year college degree; and/or younger.

We also find that many families across the board are striving for more economic security.

Using data from the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances, we discuss trends in a series of charts and discuss pathways toward building that security. Dollar values in all figures and text are adjusted with the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) to 2016 dollars (i.e., inflation-adjusted to represent comparable values or “real terms”).

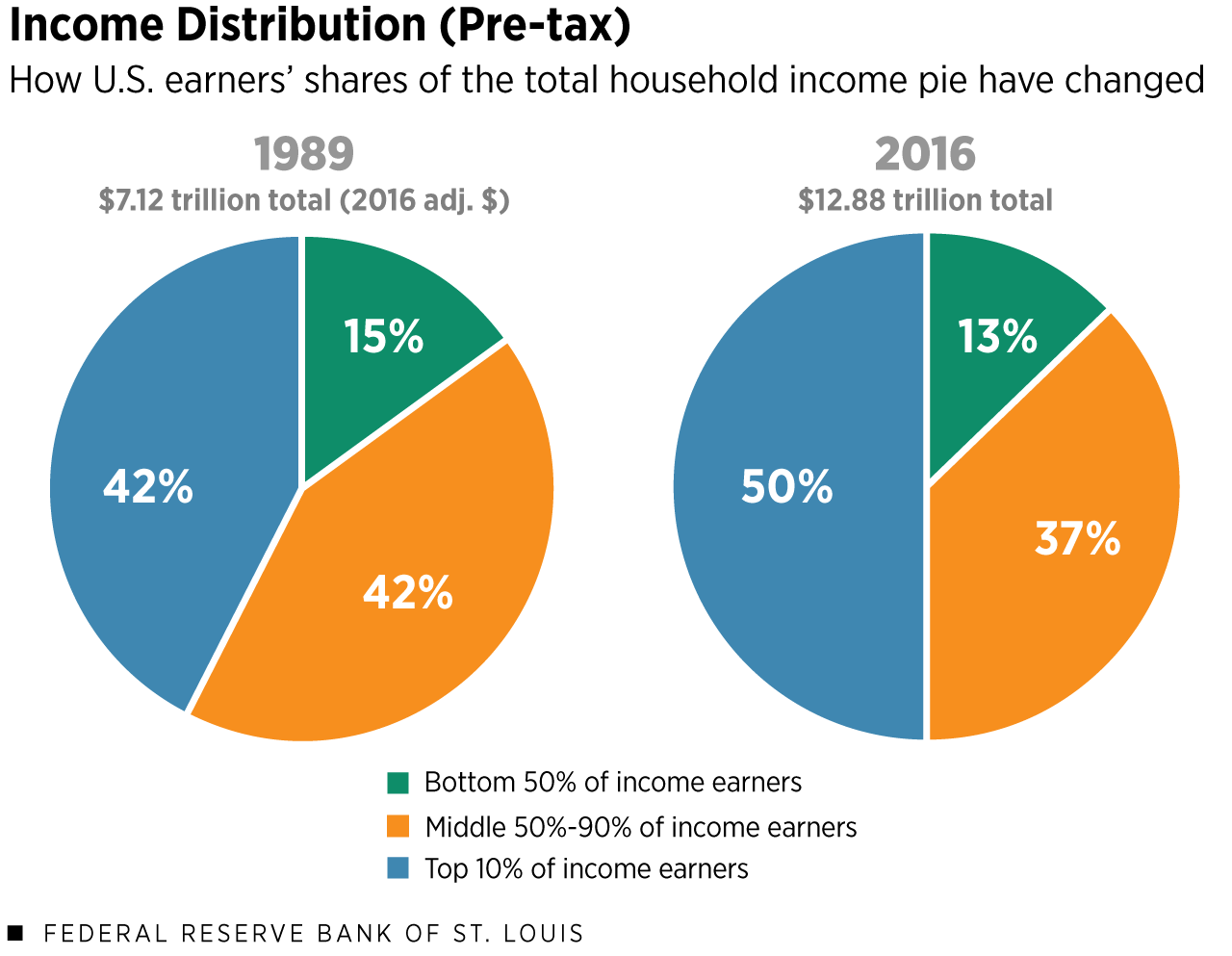

1) Income inequality has grown.

Income is a fairly common indicator of financial well-being. Let’s examine how income inequality has changed from 1989 to 2016, the earliest and latest years for which Survey of Consumer Finances data are available.

Notes: Totals may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Sources: Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances and authors’ calculations.

Description: This figure includes two pie charts. The chart on the left shows the 1989 share of total pre-tax income for the bottom 50% of income earners, the middle 50% to 90%, and the top 10% of income earners. The values are 15% share, 42% share and 42% share, respectively. The right pie chart shows the 2016 shares of those same groups: a 13% share for the bottom 50% of income earners; a 37% share for the middle group; and a 50% share for the top 10% of income earners.

The charts above show different groups of U.S. income earners:

- The bottom 50% — In 2016, households in the 0-50 th percentiles had incomes of $0 to $53,000.

- The middle 50%-90% — These households had incomes between $53,000 and $176,000.

- The top 10% — Households in the 90 th percentile had incomes of $176,000 or above.

Consider that the U.S. has a total “income pie.” Think of it as all of the pre-tax household income combined—including wages, interest, capital gains, food stamps, Social Security and all other sources of income.

That pie was worth $7.12 trillion in 1989 and grew to be worth $12.88 trillion in 2016.

How has each group’s share of the pie changed over the past three decades? The bottom 50% and middle 50%-90% of income earners have slightly smaller shares of the pie, while the share of the top 10% has grown to half the pie.

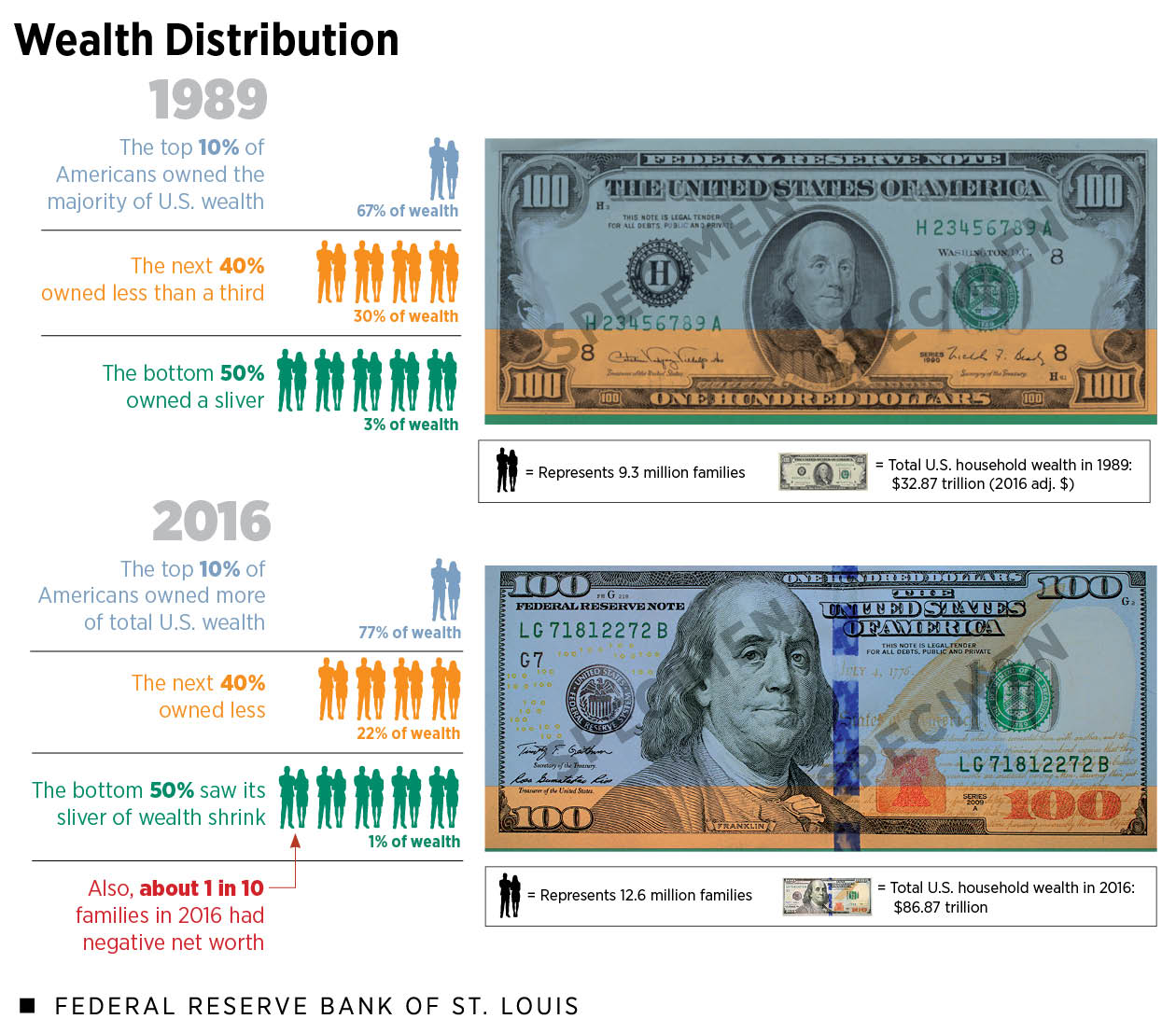

2) Wealth inequality is starker.

Income allows a family to get by; wealth allows a family to get ahead.

A family’s net worth, or wealth, is its assets—things like savings, 401(k)s and real estate—minus its debts—things like mortgages, credit card debt and student loans.

- In 1989, the total household wealth in the U.S. was $32.87 trillion (2016 adjusted dollars).

- In 2016, total U.S. household wealth amounted to $86.87 trillion.

Just like income, we can look at the changing distribution of wealth in the U.S.

Notes: Dollar values are CPI-U adjusted to 2016 dollars and rounded to the nearest $10 billion.

Description: This figure shows the distribution of total U.S. wealth in 1989 and 2016, with the shares of the top 10%, middle 50%-90% and bottom 50% of families ordered by household wealth. In 1989, these shares were 67%, 30% and 3%, respectively. In 2016, the shares were 77%, 22% and 1%, respectively. A callout indicates that roughly 1 in 10 families in 2016 had negative net worth; that’s up from about 7% of families in 1989. The 1989 population was approximately 93 million families, while the 2016 population was approximately 126 million families.

Wealth inequality in America has grown tremendously from 1989 to 2016, to the point where the top 10% of families ranked by household wealth (with at least $1.2 million in net worth) own 77% of the wealth “pie.” The bottom half of families ranked by household wealth (with $97,000 or less in net worth) own only 1% of the pie.

You read that correctly. If we rank everyone according to their family net worth and add up the wealth of the bottom 50%, which includes roughly 63 million families, that sum is only 1% of the total household wealth of the United States.

Moreover, we can compare how average wealth within each group has changed. These are not the same families being compared over time. Each survey year of the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances samples new families, and estimates are weighted to be representative of the entire U.S. population.

- In 2016, the average wealth of families in the top 10% was larger than that of families in the same group in 1989.

- The same goes for the average wealth of families in the middle 50 th to 90 th percentiles.

- The average wealth of the bottom 50% however, decreased from about $21,000 to $16,000.

So, even though the total wealth pie grew, this rising economic tide did not lift all boats. On average, the bottom half of Americans are getting left behind.

An additional sign of economic insecurity? In 2016, more than 10% of families had negative net worth, up from about 7% of families in 1989.

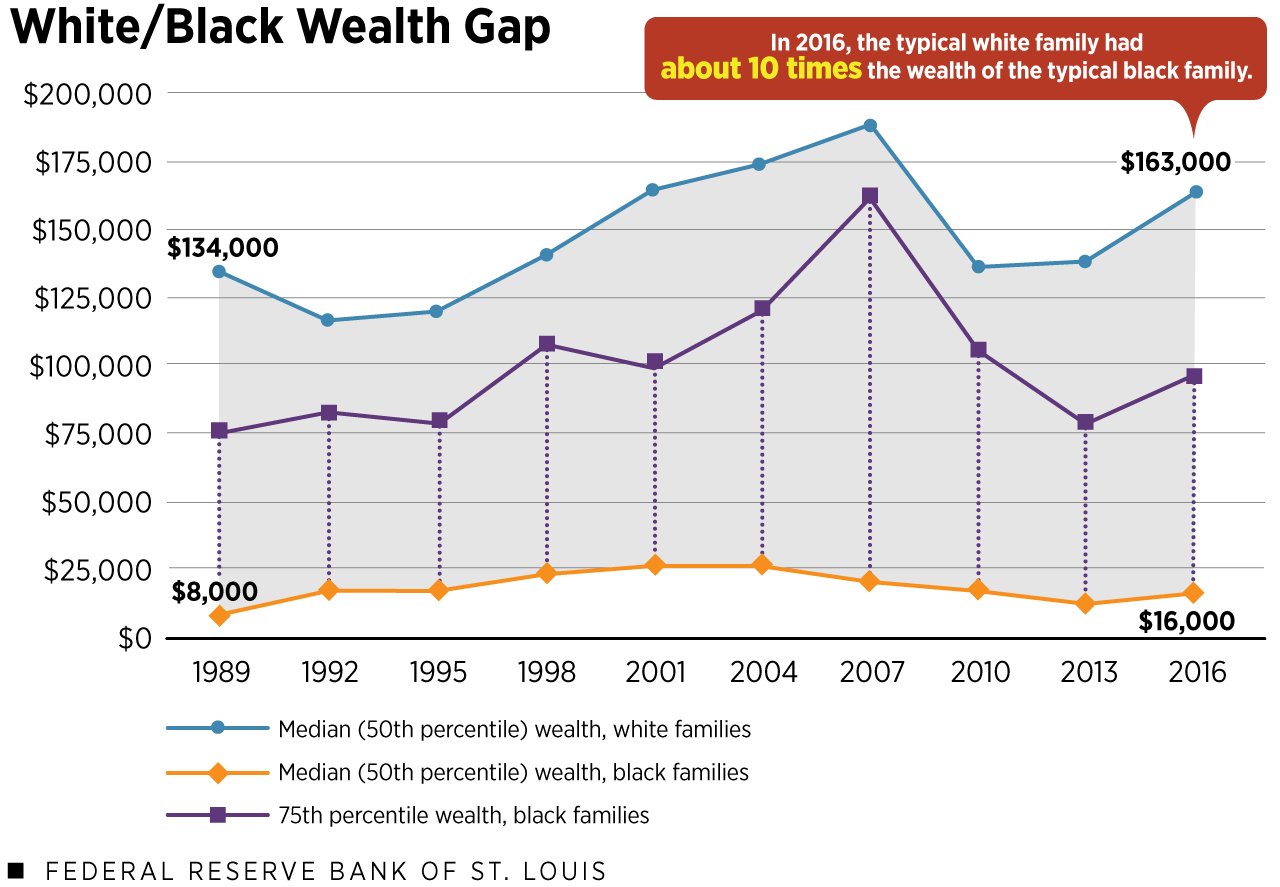

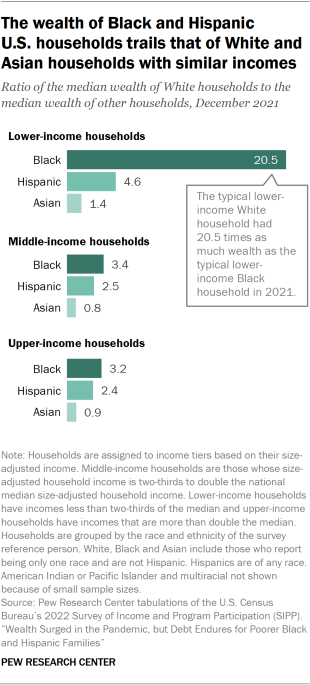

3) The racial wealth gap is largely unchanged.

Aggregate trends can mask financial weakness revealed when splitting groups demographically: for example, the racial and ethnic wealth gaps.

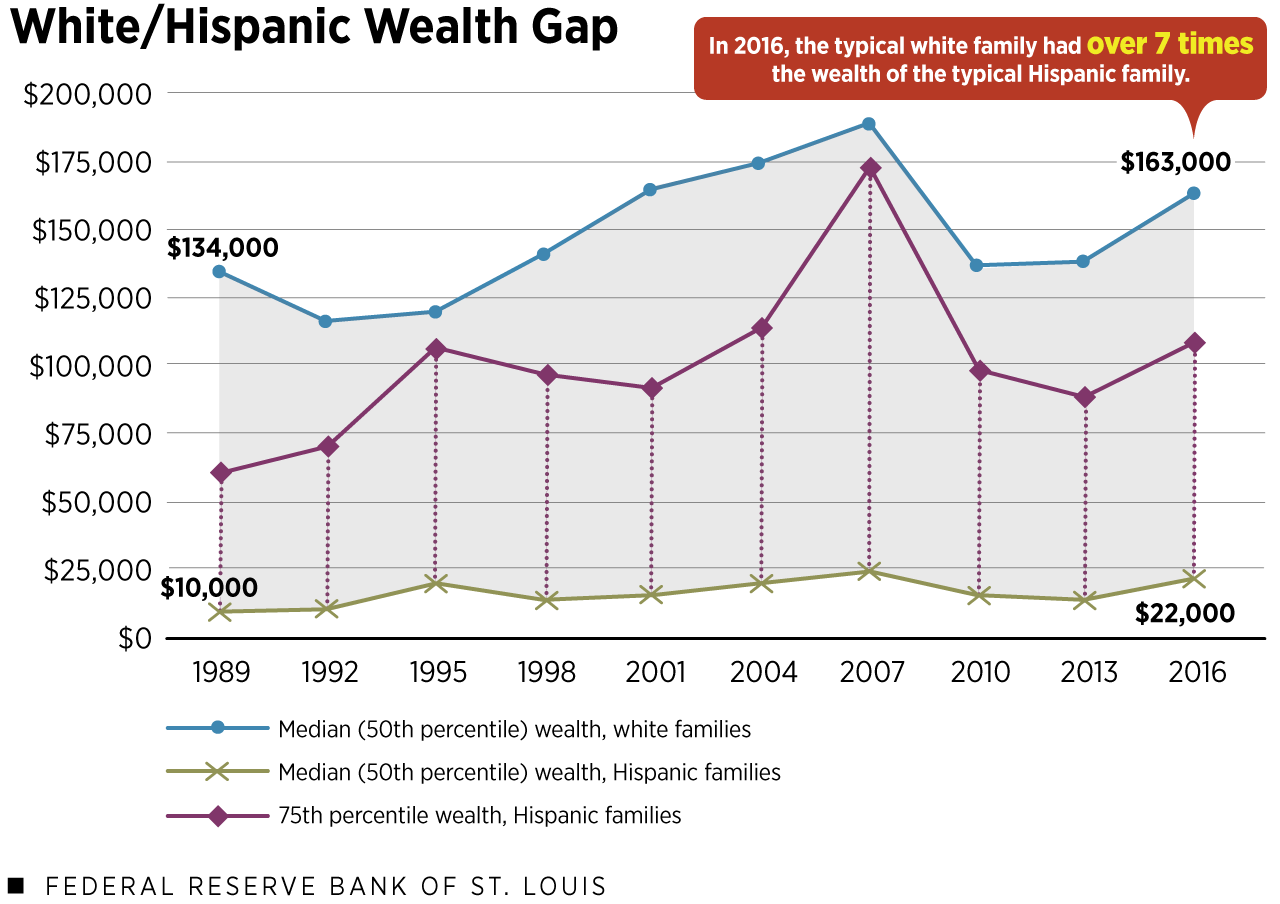

Despite some fluctuation, the large racial and ethnic wealth gaps remain essentially unchanged when looking at white/black and white/Hispanic families. (Note that families are grouped by the survey respondent’s primary racial/ethnic choice.)

In 2016, the typical white family had about 10 times the wealth of the typical black family and about 7.5 times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family.

Notes: Dollar values are CPI-U adjusted to 2016 dollars and rounded to the nearest $1,000.

Description: This line chart displays the white/black racial wealth gap from 1989 to 2016. The top horizontal line shows the median (50 th percentile) wealth of white families, which was $134,000 in 1989 and $163,000 in 2016. The bottom horizontal line shows the median (50 th percentile) wealth of black families, which was $8,000 in 1989 and $16,000 in 2016. The tops of the dotted vertical lines indicate the 75 th wealth percentile for black families; notably, these never reach the 50 th wealth percentile of white families.

Notes: Dollar values are CPI-U adjusted to 2016 dollars and rounded to the nearest $1,000. Comparative figures result from using unrounded numbers.

Description: This line chart displays the white/Hispanic ethnicity wealth gap from 1989 to 2016. The top horizontal line shows the median (50 th percentile) wealth of white families, which was $134,000 in 1989 and $163,000 in 2016. The bottom horizontal line shows the median wealth of Hispanic families, which was $10,000 in 1989 and $22,000 in 2016. The tops of the dotted vertical lines indicate the 75 th wealth percentile for Hispanic families; these never reach the 50 th wealth percentile of white families.

By “typical,” we mean a family at the middle or median; in other words, the 50 th percentile of the wealth distribution for that race or ethnicity. This middle wealth value is a useful approximation of the “typical” family’s experience because it is more resistant to extremely high- or low-wealth families than the average.

The figures above show that over a nearly three-decade period, the U.S. has seen very little progress in narrowing racial and ethnic wealth gaps.

In terms of the total wealth pie that we examined earlier—$86.87 trillion in 2016—white families in 2016 owned 89% of it, while black and Hispanic families owned a 3% sliver each.

This is especially troubling given the changing racial makeup of the population. More than 1 in 4 families are headed by a black or Hispanic person, up from 1 in 5 in 1989. Yet their slivers of the economic pie have barely budged, according to our research.

What might be particularly indicative of the magnitude of the racial wealth gap? In no survey year of the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances, 1989 to 2016, did the wealth of black or Hispanic families in the 75 th percentile reach the wealth level of white families at the 50 th percentile.

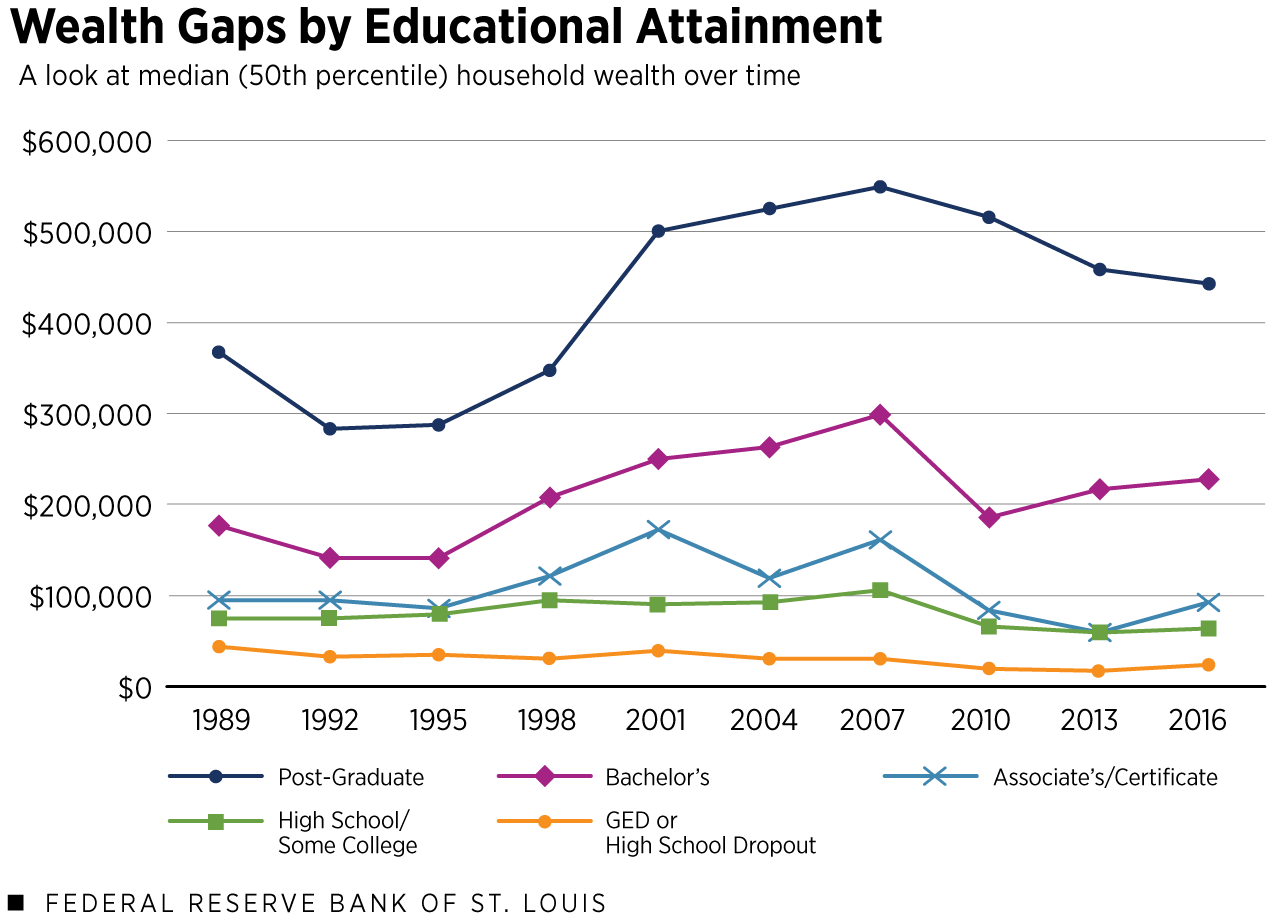

4) The educational wealth gap has grown.

Thirty-four percent of families were headed by someone with at least a four-year college degree in 2016, up from 23% in 1989. This may reflect a growing belief that college helps people get ahead financially.

Indeed, looking at the whole, we find that families with a four-year degree or higher are doing quite well; they had roughly three-quarters of the wealth pie in 2016, up from half in 1989. Four-year college graduates and postgraduates have also seen their median wealth grow in real terms (i.e., after adjusting for inflation).

Description: This line chart displays the educational wealth gap, 1989 to 2016. From top to bottom, the median household wealth values of five educational groups are shown: families headed by someone with a postgraduate degree; a bachelor’s degree; an associate’s degree or certificate; a high school degree or some college (but no degree); and a GED or a high school dropout. In 1989, the median wealth of each group of families was $367,000, $176,000, $94,000, $76,000 and $45,000, respectively. In 2016, the median wealth values were $443,000, $229,000, $93,000, $64,000 and $24,000, respectively. Dollar values are CPI-U adjusted to 2016 dollars and rounded to the nearest $1,000.

On the other end of the spectrum, families with less than a high school degree or at most a GED have about half as much wealth at the median than families with the same education level did in 1989.

The group of families with at most an on-time high school degree (including families with some college experience, but no degree) has also experienced wealth losses at the middle, relative to similar families in earlier survey years.

Meanwhile, the median wealth of families with at most a two-year college degree or certificate has fluctuated, but in 2016 it was very similar to the median wealth of 1989 families headed by someone who’d attained the same level of education.

Taken together, the wealth gap has grown between families who are headed by someone with a four-year degree and families who are not.

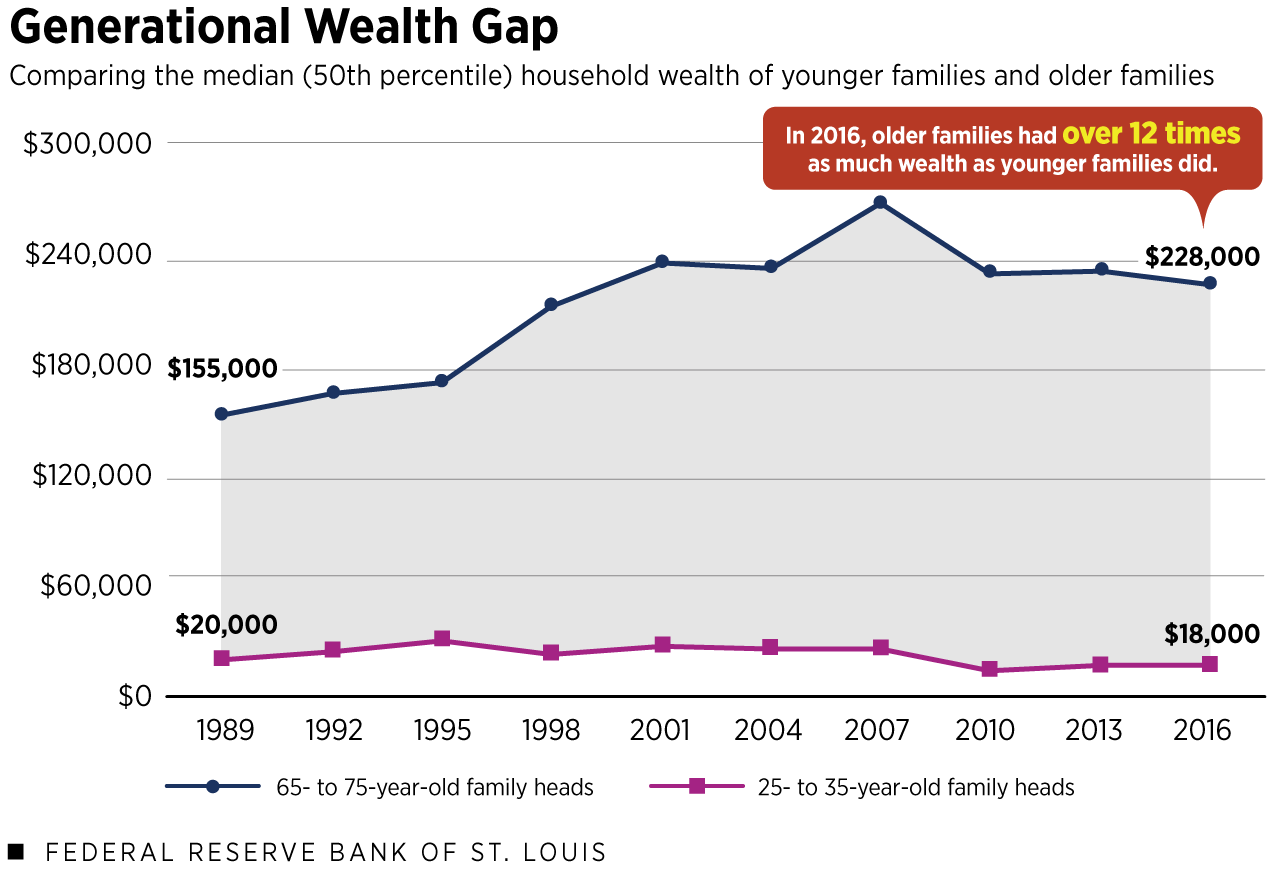

5) The generational wealth gap also has widened.

The generational wealth gap has grown, too.

For example, let’s compare a group of younger families headed by 25- to 35-year olds to a group of older families headed by 65- to 75-year olds.

Taking the median, or middle, wealth value of each of those age groups, we see that older families had more than seven times the wealth of younger families in 1989. By 2016, this generational wealth gap had grown: older families had more than 12 times the wealth of younger families.

Notes: Dollar values are CPI-U adjusted to 2016 dollars and are rounded to the nearest $1,000.

Description: This line chart displays the generational wealth gap from 1989 to 2016. The top line shows the median (50 th percentile) household wealth of families headed by 65- to 75-year olds, and the bottom line shows the median household wealth of families headed by 25- to 35-year olds. In 1989, these values were $155,000 and $20,000, respectively. In 2016, these values were $228,000 and $18,000, respectively.

Older families have more wealth than same-aged families did in years past, while younger families have less wealth. We find that age 60 is a demarcation point. Families headed by someone age 60 or older in 2016 had more wealth than similarly aged families in 1989. Meanwhile, families headed by someone younger than 60 had less wealth than similarly aged families.

My colleagues and I examine this in depth in our recent Demographics of Wealth series .

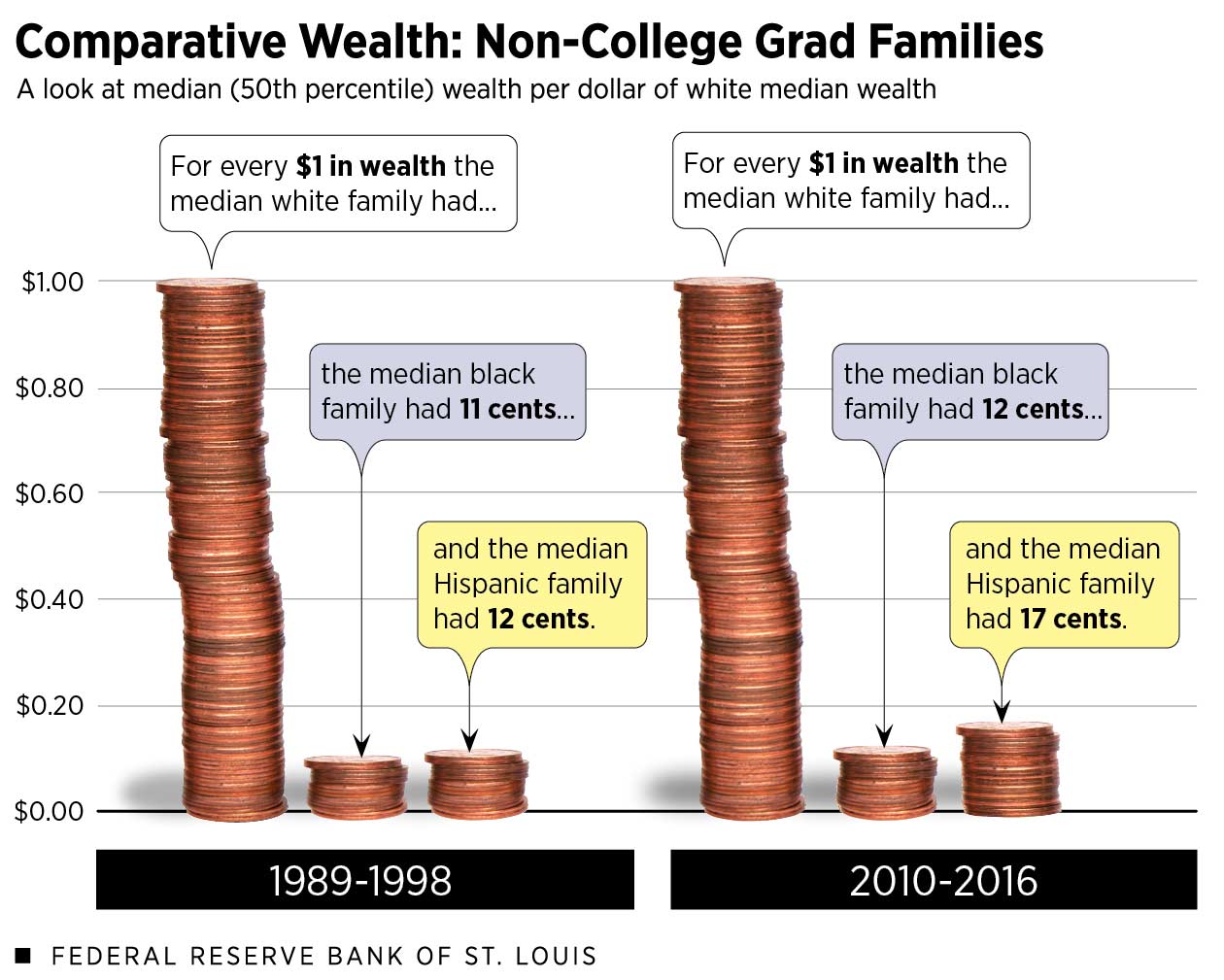

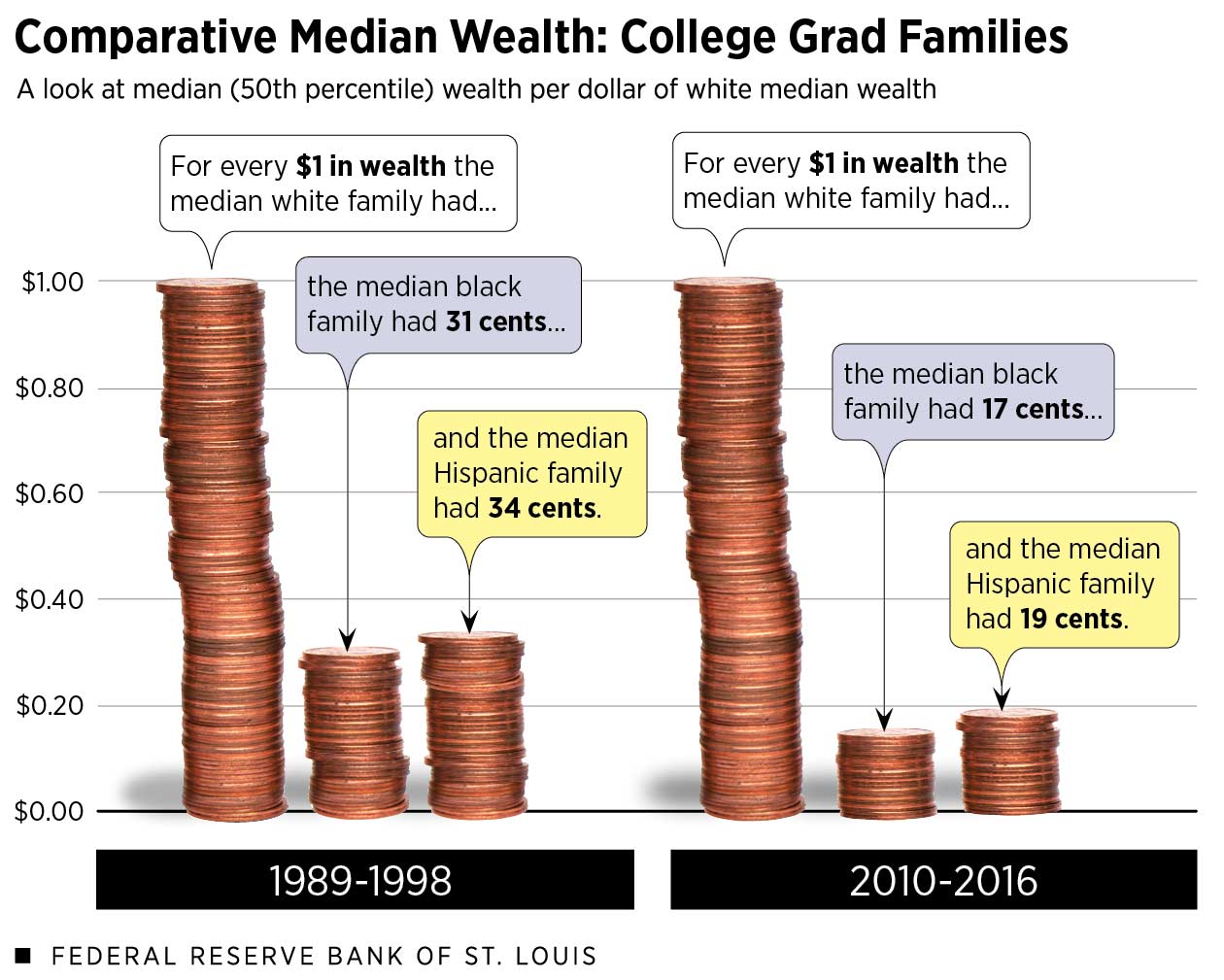

6) The racial wealth gap is large for college graduates and nongrads.

While college is touted as the great equalizer, the data show that large racial and ethnic wealth gaps remain.

To examine gaps, let’s look at the median wealth of white, black and Hispanic families with four-year college degrees. We’ll also look at the median wealth of white, black and Hispanic families without four-year degrees—from here on out, called “nongrads.” Taking this approach helps us to control for education. Because the sample size of black and Hispanic college graduates is very small in some survey waves, we grouped survey years into an earlier period (1989, 1992, 1995 and 1998) and a later period (2010, 2013 and 2016). This makes long-term trends easier to see. Each family’s wealth was standardized for each survey year and medians were calculated on these standardized wealth values for each period. See the Appendix in the third Demographics of Wealth essay for more detail.

“Nongrads” includes families with at most a two-year college degree, as their wealth outcomes more closely mirror the wealth of families with at most an on-time high school degree than the wealth of four-year college graduate families.

Notes: Dollar values are CPI-U adjusted to 2016 dollars.

Description: This figure shows the comparative median wealth of families headed by someone who has not attained a four-year degree. The left stack of pennies shows that for every dollar of white nongrad median wealth in the earlier period (1989-1998), black nongrad families owned 11 cents and Hispanic nongrad families owned 12 cents. The right stack of coins shows these values in the later period (2010-2016), standing at 12 cents for black families and 17 cents for Hispanic families.

Among nongrads, the white/black and white/Hispanic wealth gaps narrowed slightly between the earlier (1989-1998) and later (2010-2016) periods. This trend is largely due to the decline among white nongrads , whose median wealth shrank from $101,000 in the earlier period to $88,000 in the later period.

- At the median, black nongrad families had 11 cents per dollar of white nongrad wealth in the earlier period. By the later period, their wealth had grown to 12 cents per dollar of white wealth.

- For Hispanic nongrad families, their median wealth grew from 12 cents to 17 cents per dollar of white nongrad wealth between the earlier and later periods.

Among black and Hispanic families headed by someone with a four-year college degree, the racial wealth gaps were historically narrower than among nongrads.

However, the Great Recession hit them very hard , and in recent years the college boost has been depleted to the point where there is little difference in the racial and ethnic wealth gap among grads versus nongrads.

Description: This figure shows the comparative median wealth of families headed by someone who has attained at least a four-year degree. The left stack of pennies shows that for every dollar of white college grad median wealth in the earlier period (1989-1998), black grad families owned 31 cents and Hispanic grad families owned 34 cents. The right stack of coins shows these values in the later period (2010-2016), standing at 17 cents for black families and 19 cents for Hispanic families.

This is due in large part to the gains of white college graduates. In the later period, black grads had 17 cents per dollar of white grad median wealth, down from 31 cents in the earlier period. Hispanic graduates’ median wealth went from 34 cents to 19 cents per dollar of white wealth between these time periods.

Conclusions

This series of charts illustrates the wide range in wealth outcomes within the United States. Demographic cuts illuminate vast differences otherwise obscured by aggregate statistics.

Demography may not be economic destiny, but it is strongly related to financial outcomes. Ongoing structural and systemic barriers may make it difficult to narrow gaps for some racial and ethnic groups.

Based on past research, here are four recommendations that could help families build wealth.

Help families build a rainy-day fund.

Having cash on hand contributes to financial stability and greatly reduces risk of hardship . These funds can be built through employers, at tax time, through mobile apps, and through innovations such as “prize-linked savings.”

Promote early-in-life investments.

In particular, efforts can be made to expand early education and early savings, such as child savings accounts, which have positive financial and social outcomes . These early investments are likely to have the largest effect on longer-term outcomes, and investing early in children can pay for itself over time.

Examine college costs.

Address the rising cost of college and reduce the need for students to finance post-secondary education with loans. While not for everyone, innovations such as Income Share Agreements , income-driven repayments and College Savings Accounts should be considered.

Support all forms of housing.

Increase the supply of affordable rental housing while promoting paths to sustainable homeownership. Homeownership should be treated as a “capstone” financial event, not a first step; building a diversified balance sheet—with low levels of consumer debts and high levels of liquid savings—should precede and help sustain homeownership.

For an in-depth discussion and additional resources, see the Demographics of Wealth series . Dig deeper into structural and systemic barriers to wealth accumulation here (PDF).

Notes and References

- Dollar values in all figures and text are adjusted with the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) to 2016 dollars (i.e., inflation-adjusted to represent comparable values or “real terms”).

- These are not the same families being compared over time. Each survey year of the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances samples new families, and estimates are weighted to be representative of the entire U.S. population.

- Because the sample size of black and Hispanic college graduates is very small in some survey waves, we grouped survey years into an earlier period (1989, 1992, 1995 and 1998) and a later period (2010, 2013 and 2016). This makes long-term trends easier to see. Each family’s wealth was standardized for each survey year and medians were calculated on these standardized wealth values for each period. See the Appendix in the third Demographics of Wealth essay for more detail.

This blog post was updated Dec. 5, 2019, with additional authorship attribution.

Ana Hernández Kent is a senior researcher with the Institute for Economic Equity at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Her research interests include economic disparities and the role of systemic biases and historical factors in wealth outcomes. Read more about Ana’s research .

Lowell R. Ricketts is a data scientist for the Institute for Economic Equity at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. His research has covered topics including the racial wealth divide, growth in consumer debt, and the uneven financial returns on college educations. Read more about Lowell's research .

Ray Boshara is a former senior advisor and assistant vice president of the Institute for Economic Equity at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. He is also a senior fellow in the Financial Security Program at the Aspen Institute.

Related Topics

This blog explains everyday economics, consumer topics and the Fed. It also spotlights the people and programs that make the St. Louis Fed central to America’s economy. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other blog-related questions

We serve the public by pursuing a growing economy and stable financial system that work for all of us.

- Center for Indian Country Development

- Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute

Monetary Policy

- Banking Supervision

- Financial Services

- Community Development & Outreach

- Board of Directors

- Advisory Councils

Work With Us

- Internships

- Job Profiles

- Speakers Bureau

- Doing Business with the Minneapolis Fed

Overview & Mission

The ninth district, our history, diversity & inclusion, region & community.

We examine economic issues that deeply affect our communities.

- Request a Speaker

- Publications Archive

- Agriculture & Farming

- Community & Economic Development

- Early Childhood Development

- Employment & Labor Markets

- Indian Country

- K-12 Education

- Manufacturing

- Small Business

- Regional Economic Indicators

Community Development & Engagement

The bakken oil patch.

We conduct world-class research to inform and inspire policymakers and the public.

Research Groups

Economic research.

- Immigration

- Macroeconomics

- Minimum Wage

- Technology & Innovation

- Too Big To Fail

- Trade & Globalization

- Wages, Income, Wealth

Data & Reporting

- Income Distributions and Dynamics in America

- Minnesota Public Education Dashboard

- Inflation Calculator

- Recessions in Perspective

- Market-based Probabilities

We provide the banking community with timely information and useful guidance.

- Become a Member Bank

- Discount Window & Payments System Risk

- Appeals Procedures

- Mergers & Acquisitions (Regulatory Applications)

- Business Continuity

- Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility

- Financial Studies & Community Banking

- Market-Based Probabilities

- Statistical & Structure Reports

Banking Topics

- Credit & Financial Markets

- Borrowing & Lending

- Too Big to Fail

For Consumers

Large bank stress test tool, banking in the ninth archive.

We explore policy topics that are important for advancing prosperity across our region.

Policy Topics

- Labor Market Policies

- Public Policy

Racism & the Economy

How the racial wealth gap has evolved—and why it persists.

October 3, 2022

Article Highlights

- New dataset tracks evolution of racial wealth gap from 1860 to 2020

- Racial wealth gap today is legacy of vastly unequal wealth for Black and White Americans following Civil War

- Racial wealth gap has been stagnant for last 40 years due to differences in Black and White households’ wealth portfolios

— W. E. B. Du Bois , The Souls of Black Folk

The dawn of emancipation in the United States saw 4 million former slaves, 90 percent of the Black American population, gain their freedom. But they did so in poverty, as Du Bois describes: A few years prior, they had been counted as wealth, earning and owning nothing in their own name.

After emancipation, proposals to provide former slaves with land so they could survive economically were largely defeated . Thus in 1870, the wealth gap between Black and White Americans was a staggering 23 to 1 . That's equivalent to just $4 of wealth for Black Americans for every $100 for White Americans.

The mission of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute is to conduct and promote research that will increase economic opportunity and inclusive growth for all Americans and help the Federal Reserve achieve its maximum employment mandate. Connect with us to receive emails with Institute news, insights, and events.

Fast forward 150 years and that gap has narrowed to about 6 to 1—and yet, a significant gap remains: average per capita wealth of White Americans was $338,093 in 2019 but only $60,126 for Black Americans.

In the new Institute working paper “ Wealth of Two Nations: The U.S. Racial Wealth Gap, 1860–2020 ,” former Institute visiting scholar Ellora Derenoncourt and colleagues Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn, and Moritz Schularick study the evolution of the Black-White racial wealth gap to understand how it has changed and what forces drove those changes.

“We wanted to see if there was something to be learned for policy: Do we see that certain periods were particularly good, particularly bad in terms of convergence? What conclusions can we draw from that?” Kuhn said about one motivation the author team had for undertaking the research.

Drawing on numerous historical resources, the economists construct a new dataset that fills in around 100 years of missing wealth data, from the 1880s to the 1980s, when modern surveys of wealth began. They then use a model of wealth accumulation to investigate the sources of the wealth gap.

So where does wealth come from? Yesterday’s wealth, mostly. Unlike income, which can change quickly—lose a job, take a new job—wealth builds slowly from interest on previous wealth and new savings from income. For that reason, “it takes a lot of time to build wealth and to close an existing wealth gap, especially if the world around you is not stopping to accumulate wealth,” Kuhn said.

The economists’ analysis suggests that, more than 150 years after the end of slavery, today’s racial wealth gap is the legacy of very different wealth conditions after emancipation. While the White-Black income gap has narrowed over time, differences in Black and White Americans’ capital gains rates and savings rates throughout history have slowed the convergence (closing the gap) between Black and White wealth.

The result: An enduring wealth gap that shows no sign of resolving. “It was interesting for us to see how extremely persistent the racial wealth gap is. We saw a lot of things changing in the U.S. economy in the last 70 years, but the racial wealth gap seems to be pretty ignorant of all that,” Kuhn observed.

Evolution of the racial wealth gap

Tracing 150 years of the racial wealth gap 1 reveals rapid early progress followed by frustrating stagnation (Figure 1).

Dawn of emancipation: 1870 to 1900

The thirty years following emancipation saw rapid narrowing of the racial wealth gap, falling from a ratio of 56 to 1 in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War to 23 to 1 in 1870 following emancipation and 11 to 1 in 1900. (In 2019 dollars, that comes to average wealth of $34,000 for a White American and $3,100 for a Black American.) White slaveholders’ loss of slaves as “wealth” explains about a quarter of this convergence. The rest was due to a higher wealth accumulation rate for Black Americans than White Americans.

This convergence, however, is more a matter of statistics than reflection of meaningful economic or political change. Because Black Americans’ wealth was so low in 1870, even small gains translated to big percent increases in wealth and thus large reductions in the wealth gap, even though the difference in the amount of average wealth held by Black Americans and White Americans remained large.

Unfortunately, this period of rapid convergence was relatively short-lived. Proposals to redistribute property to former slaves, such as General William Sherman’s field order allowing freed slaves to establish 40-acre farms on federal land, ultimately failed to garner sufficient political support, and early enforcement of Black Americans’ rights were similarly reversed. By 1900, a racist economic and social order was largely restored.

Racist resurgence: 1900 to 1930

Between 1900 and 1930, the racial wealth gap narrowed tepidly, at a rate around 0.3 percent a year. During this period, Black Americans’ share of national wealth stayed fairly constant, at 1 percent (Figure 2).

“Barriers to Black economic progress were pervasive in the post-Reconstruction era,” the economists observe. For instance, Black Americans had limited access to financial institutions or credit ; they had little opportunity to purchase land; they experienced the violent destruction of their property; they faced widespread discrimination in education and the labor market. In the South, the vast majority of Black farmers were renters or sharecroppers in an economic system that hindered Black workers’ economic progress because White landlords were able to capture their tenants’ improvements to the land simply by not renewing the lease.

Global upheaval: 1930 to 1960

Wealth convergence picked back up modestly during this period, and by 1960 the gap was 8 to 1. (In 2019 dollars, that translates to average wealth of $76,000 for White Americans and $9,000 for Black Americans.) A closer look at the timing reveals this does not appear to be the result of New Deal economic relief or new social insurance policies, which tended to exclude sectors with large representations of Black workers. Rather, labor market dynamics around the time of World War II led to Black workers moving into higher-paying occupations, notably related to war production and defense, which reduced the racial income gap and led to greater gains in Black Americans’ wealth. This movement was facilitated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802 , which banned “discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

Civil rights: 1960 to 1980

The civil rights movement was responsible for the fastest period of racial wealth convergence since 1900. Tireless efforts by Black activists to demand equal rights and protections led to the passage of numerous laws that reduced social, political, and economic discrimination, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and expansions to the Fair Labor Standards Act, which sets federal minimum wage policies.

These legislations helped narrow the racial income gap, which in turn narrowed the wealth gap; it fell from 8 to 1 in 1960 to 5 to 1 in 1980. Figure 2 shows that Black Americans’ share of national wealth started increasing more rapidly in 1960 even as the total U.S. population of Black Americans was also increasing.

Stagnation: 1980 to 2020

And then—convergence stopped. In the 40 years between 1980 and 2020, the racial wealth gap actually increased by the equivalent of 0.1 percent a year. The reasons for this stagnation are discussed in the section “A widening gap: The role of capital gains” below.

Unequal initial wealth, unequal wealth accumulation

The next step in the economists' research is to analyze the causes of the racial wealth gap. To do this, they engage in a thought experiment: What if Black and White Americans started with the radically different levels of wealth in 1870 that they did in real life, but their wealth accumulation rates were identical after that? The resulting wealth gap in 2020 would be about 3 to 1 ($100 dollars of White wealth for every $33 dollars of Black wealth). That’s about half of what the actual wealth gap is today, suggesting that unequal levels of wealth in 1870 are a major source of today’s racial wealth gap.

The fact that today’s racial wealth gap is larger than it would be under this optimistic scenario is due to unequal wealth accumulation rates, which of course haven’t been identical for White and Black Americans, as the brief history above of political and economic exclusion makes plain.

Wealth accumulation can be described as a fairly straightforward equation. It starts with yesterday’s wealth and the interest earned on that wealth (capital gains rate). Add to that new savings from income, which is the product of yesterday’s income level, how much income has changed (income growth rate), and how much of that income is saved (savings rate).

While historical data on these rates is difficult to come by, since at least 1950, White Americans have enjoyed a higher average savings rate and capital gains rate than Black Americans (see Table 1).

What drove wealth convergence, then? The income growth rate. The economists estimate that the average annual income growth rate for Black Americans was larger than that of White Americans from 1870 to about 1980. At that point, income convergence stalled; over the last 40 years, the annual income growth rates for Black and White Americans have been essentially the same.

A widening gap: The role of capital gains

Now that income convergence has stalled, the difference in the capital gains rate experienced by Black and White households is the main factor pushing their wealth apart.

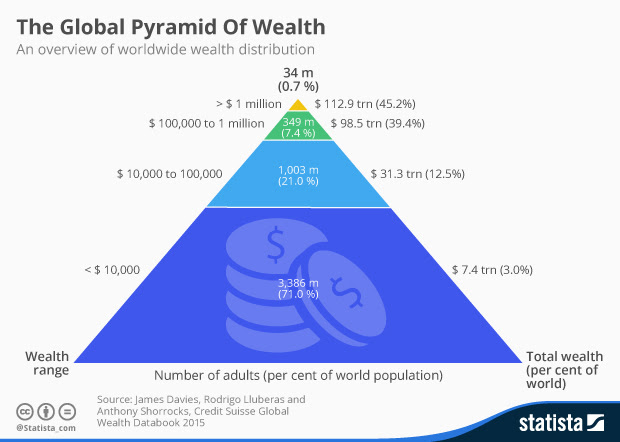

The role of capital gains is particularly important here. The high rate of return to capital holdings over the last 40 years—economic parlance for “stocks have really gone up a lot”—is a leading cause of the wealth dispersion in the United States today. According to analysis by economist Emmanuel Saez and others, wealth has become significantly more concentrated during this period: In 1980, the richest 0.1 percent of Americans—about 160,000 households—owned 7.7 percent of national wealth. In 2020, they owned 18.5 percent.

“Given that there are so few Black households at the top of the wealth distribution,” Derenoncourt and co-authors write, “faster growth in wealth at the top will lead to further increases in racial wealth inequality.”

And that’s what’s happening now. On average between 1950 and 2010, Black households held about 7 percent of their wealth in stock equity; among White households, it was 18 percent (Table 2). The portfolios of White households are also more diversified than Black households, which are concentrated in housing wealth. Housing has appreciated since the 1950s, but stock equity has appreciated five times as much.

“At a more general level,” Kuhn stated, “this research emphasizes how important portfolio choice and investment behavior is. It’s not only about putting money aside, but where you put it.”

Why wealth matters

The distribution of wealth in the United States comes under frequent scrutiny because of how skewed it is—and because wealth is a determinant of social and economic outcomes far beyond what someone can buy.

“Wealthier families are far better positioned to finance elite independent school and college education, access capital to start a business, finance expensive medical procedures, reside in higher amenity neighborhoods, lower health hazards, etc.; exert political influence through campaign financing; purchase better counsel if confronted with the legal system, leave a bequest, and/or withstand financial hardship resulting from any number of emergencies,” Institute advisor William Darity Jr. and Darrick Hamilton wrote in a 2010 article analyzing policies to address the wealth gap.

It matters a great deal, then, that White Americans hold 84 percent of total U.S. wealth but make up only 60 percent of the population—while Black Americans hold 4 percent of the wealth and make up 13 percent of the population. Put another way: The wealth of the richest 400 Americans is approximately equal to that of 43 million Black Americans.

The historical analysis and counterfactual simulations by Derenoncourt, Kim, Kuhn, and Schularick provide useful context for thinking about policies to address the racial wealth gap. Without redistribution, the wealth gap will likely persist for centuries. But redistribution alone, without attending to disparities in wealth accumulation, will see the gap reemerge. These approaches, the economists argue, are complimentary.

They are also necessary if the wealth gap is to meaningfully narrow before another 150 years slip by.

Suggested citation: Lisa Camner McKay, “How the Racial Wealth Gap Has Evolved—And Why It Persists,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, October 3, 2022, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/how-the-racial-wealth-gap-has-evolved-and-why-it-persists .

1 The economists actually compare Black wealth to non-Black wealth—that is, the average wealth among all groups except Black Americans—because the data does not allow them to separate out the wealth of other racial/ethnic groups. As a check, they compare their estimate of non-Black wealth to an estimate of White wealth in the periods 1860–1880 and 1960–2020; the estimates are very similar. Racial/ethnic groups other than White and Black were quite small in the United States prior to 1950. And because White Americans are the wealthiest racial/ethnic group in the United States, using “non-Black wealth” likely underestimates White wealth and therefore underestimates the Black-White wealth gap.

Lisa Camner McKay is a senior writer with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Minneapolis Fed. In this role, she creates content for diverse audiences in support of the Institute’s policy and research work.

Related Content

Wealth of Two Nations: The U.S. Racial Wealth Gap, 1860-2020

Yet another source of inequality: Property taxes

The wealth gap and the race between stocks and homes

Sign up for news and events.

The Reporter

Wealth Inequality in the United States

Much attention has focused in the last few years on the issue of inequality. With recent proposals for a direct wealth tax, particular attention has been given to wealth inequality. My work also focuses on this issue. Here, I summarize studies of four different aspects.

First, what are the general trends in wealth and wealth inequality over the last 60 years or so in the United States? I pay particular attention to the role of leverage and asset price movements in explaining these trends. Second, how has the racial wealth gap evolved over time, and what are the factors that account for its movement? Third, how does one account for the fact that certain assets like 401(k)s are tax-deferred? How does this affect the valuation of these assets and how does this impact measured inequality and wealth movements over time? Fourth, how might a direct tax on household wealth impact wealth inequality?

The Role of Leverage

In the first study, I examine wealth trends from 1962 to 2019. 1 My empirical work in this and the next three papers is based mainly on data from the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances. In terms of median wealth, the year 2007 stands out as a true high-water mark. Median net worth in constant dollars showed robust growth over 1962–2001, gaining 1.55 percent per year, and rose even faster over 2001–07, at 2.90 percent per year. Then the Great Recession hit like a tsunami and wiped out 40 years of gains. Over 2007–10, house prices fell 24.5 percent in real terms, stock prices declined 26.6 percent, and median wealth was reduced by a staggering 43.9 percent. By 2010, median wealth was at about the same level as in 1969.

However, between 2010 and 2019 asset prices recovered, and median wealth advanced by a robust 41.9 percent. Still, it was 20.4 percent below its 2007 peak. Mean wealth more than fully recovered by 2016 and by 2019 it was up 9.2 percent from its 2007 level.

Wealth grew more vigorously at the top of the wealth distribution than in the middle. Indeed, according to the Gini coefficient and top wealth shares, wealth inequality rose sharply from 1983 to 1989 (the Gini coefficient was up 0.029), remained relatively stable from 1989 to 2007, then showed a steep increase over 2007–10 (the Gini was up 0.032), and a more modest rise from 2010 to 2016. By 2016, the Gini coefficient and the share of the top percentile were at their highest levels of the 57 years of the study period, at 0.877 and 39.6 percent, respectively. However, from 2016 to 2019 there was actually a small decline in inequality, with the top percentile share down by 1.4 percentage points, the Gini coefficient down by 0.008, and the mean wealth of the top 1 percent down by 1.9 percent.

Another notable trend is the sharp increase in relative debt after 1983, with the debt-income and the debt-net worth ratios peaking in 2010 and then receding. The overall homeownership rate rose from 63.4 percent in 1983 to a peak of 69.1 percent in 2004, then fell off to 64.9 percent in 2019. The overall stock ownership rate — either directly or indirectly through mutual funds, trust funds, or pension plans — after rising briskly from 31.7 percent to a peak of 51.9 percent over 1989–2001, fell off to 46.1 percent in 2013. It rebounded to 49.6 percent in 2019, though it was still down from its peak.

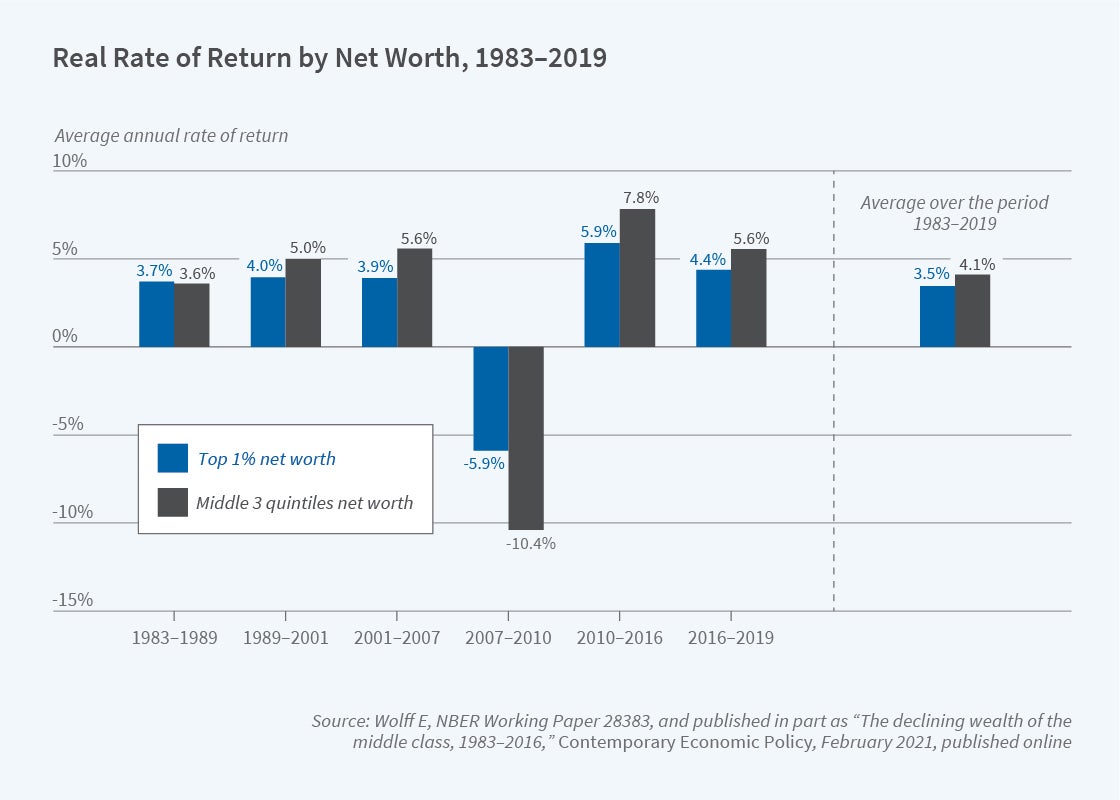

The key to understanding the plight of middle-class Americans in the years following the Great Recession is their high degree of leverage, the high concentration of assets in their homes, and the precipitous fall in home prices. This translated into a very high negative rate of return on their wealth (−10.4 percent per year), which largely explains the steep decline in median wealth over 2007–10. High leverage, moreover, helps explain why median wealth fell more than house prices over these years. The high negative rate of return accounted for 61 percent of the collapse in median net worth, with the other 39 percent due to dissaving.

What about the recovery in median wealth after 2010? In 2010–16, the rate of return should have led to a $42,600 increase in median wealth, while the actual increase was $12,200. Dissaving reduced the gain by $30,400. For 2016–19, both the rate of return and saving made positive contributions, explaining 85.6 and 14.4 percent of the gain, respectively.

The large spread in returns between the middle three wealth quintiles and the top percentile — over 4 percentage points — also helps explain why wealth inequality climbed steeply from 2007 to 2010. It is first of note that, as shown in Figure 1, the return on net worth for the middle group exceeded that for the top percentile over the whole 1983–2019 period and for all subperiods except 1983–89 and 2007–10. A lot of theoretical work on wealth inequality assumes just the opposite relationship. In a decomposition analysis of the change in the ratio of the wealth of the top percentile to median wealth, the differential in returns between the two groups accounted for 28.7 percent of the increase in the inequality ratio over the Great Recession, with differences in saving accounting for the rest. The middle class took a bigger relative hit to its wealth from the home price plunge than the top 1 percent did from the stock market decline. There was a modest rise in the inequality ratio from 2010 to 2016. The same decomposition shows that the differential in returns between the two groups — now in favor of the middle group — should have led to a decline in the inequality ratio, while there actually was an increase. The inequality ratio fell a bit from 2016 to 2019. In this case, the rate of return difference — again in favor of the middle group — accounted for 18.2 percent of the decline and the residual accounted for 81.8 percent.

The Decline in Black and Hispanic Wealth

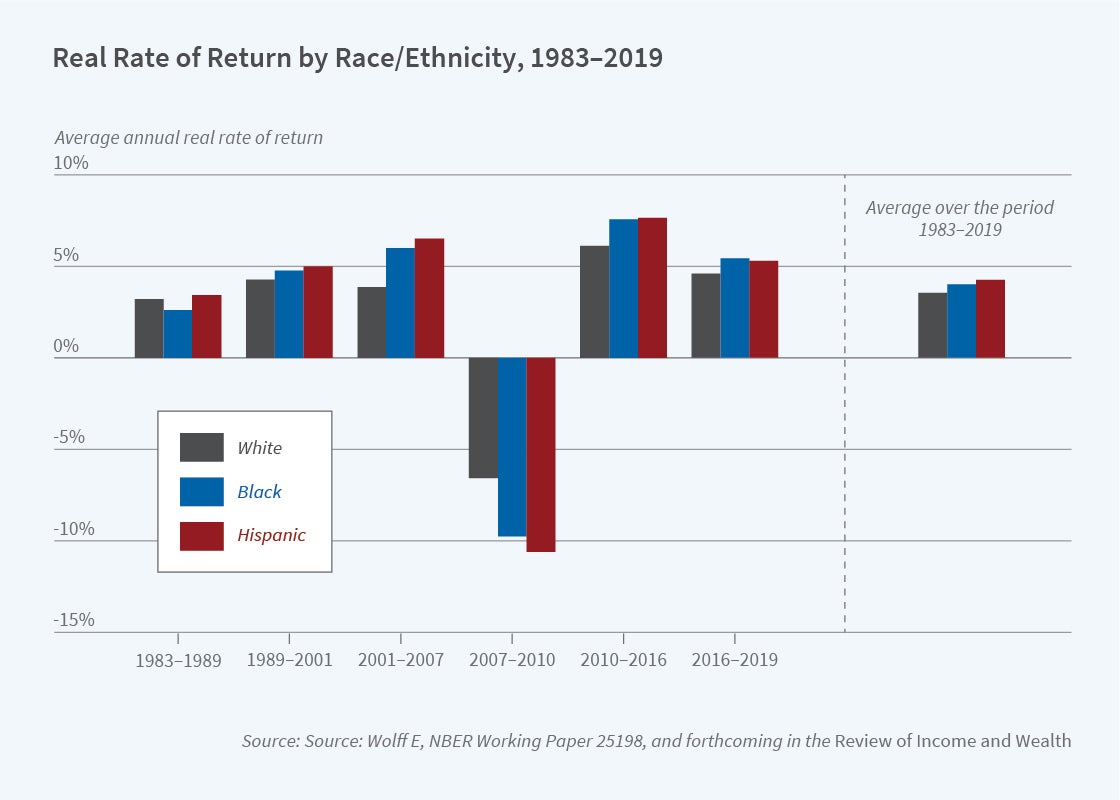

The year 2007 was also a watershed year for both the racial and ethnic wealth gaps. 2 The ratios of mean net worth between Blacks and Whites and between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites reached their maximum values, 0.19 and 0.26, respectively. The Great Recession hit Black households much harder than White because Blacks were more highly leveraged and had a greater share of their assets in their homes; the racial ratio plunged to 0.14 in 2010, reflecting a 33 percent decline of Black wealth in real terms. The wealth gap remained unchanged from 2010 to 2019.

Hispanic households made sizable gains on White households from 1983 to 2007, with the mean net worth ratio growing from 0.16 to 0.26. However, like Blacks, Hispanics got hammered by the Great Recession, with their mean net worth plunging in half over 2007–10 and the wealth ratio falling from 0.26 to 0.15. The relative and absolute losses suffered by Hispanic households over these three years were also mainly due to their much higher leverage and greater concentration of assets in homes. Over 2010–16, the mean wealth ratio rebounded to 0.19, where it remained in 2019.

Differential leverage and resulting differences in rates of return on net worth play critical roles in accounting for movements in the wealth of minorities relative to Whites. Blacks and Hispanics had much higher indebtedness and a higher concentration of housing wealth than Whites. In 2007, the debt-net worth ratio among Black households was an astounding 0.553 and that for Hispanics was 0.511, compared to 0.154 among Whites. Housing as a share of gross assets was 54 percent for Blacks and 52.5 percent for Hispanics, compared to 30.8 percent for Whites. The rate of return on net worth for the Black and Hispanic middle groups surpassed that for Whites for the whole period 1983–2019 and for all subperiods except 1983–89 and 2007–10, as shown in Figure 2.

Using a decomposition analysis, I find that capital revaluation explains about three-quarters of the advance of mean wealth among Black households over 2001–07 and 78 percent of the ensuing collapse over 2007–10. Among Hispanics, the corresponding figures are 59 and 57 percent. Differentials in returns account for 43 percent of the gain in the Black-White wealth ratio over 2001–07 and 39 percent of the decline over 2007–10. Over 2010–19, the higher rate of return for Black households should have helped close the racial wealth gap, but this was offset by greater dissaving.

Likewise, disparities in returns account for 33 percent of the gain in the Hispanic-White wealth ratio in 2001–07 and 28 percent of the ensuing drop over 2007–10. Over 2010–16, the higher returns for Hispanic households explain 41.4 percent of their relative gains, but over 2016–19 this effect is neutralized by greater dissaving.

The racial gap in augmented wealth, defined as the sum of net worth, defined-benefit pension wealth, and Social Security wealth, is considerably smaller than that in net worth. The former is defined as the present value of expected future pension benefits and the latter as the present value of expected Social Security benefits. In 2016, while the Black-White ratio in mean net worth was 0.14 and that in median net worth a mere 0.02, the ratio in mean augmented wealth was 0.27 and that in median augmented wealth also 0.27. The ratios in mean defined-benefit pension and Social Security wealth were notably higher, at 0.50 and 0.60, respectively. Whereas the racial gap in net worth widened from 1983 to 2016, the gap in augmented wealth remained largely unchanged.

Taxes and the Revaluation of Household Wealth

The face value of 401(k)s, IRAs, and other tax-deferred assets cannot be directly valued with other components of wealth like houses, stocks, and securities because tax-deferred assets carry a substantial tax liability on withdrawal. 3 For example, an IRA valued at $1,000 can yield considerably less than $1,000 when the asset is “cashed out.” Whether the net rate of return is higher with tax-deferred assets or directly investing in stocks depends on the income level of the investor, the time horizon, and the tax treatment of dividends.

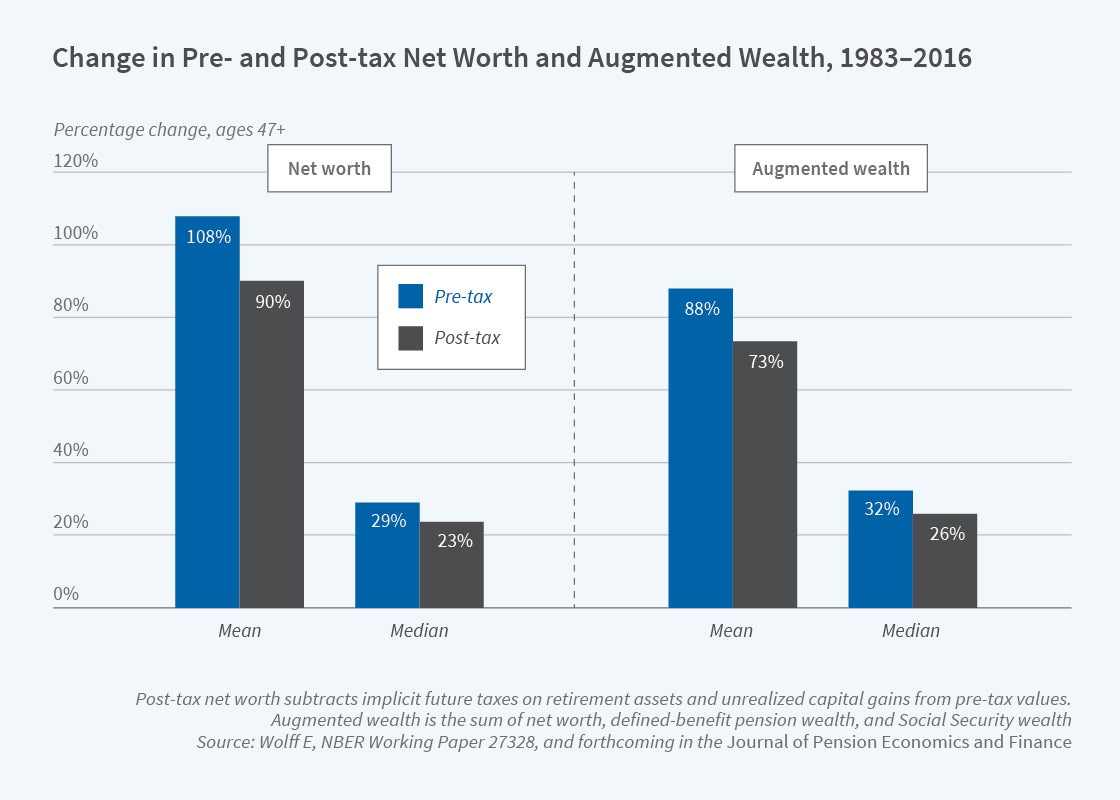

I compare trends in wealth levels and wealth inequality with and without netting out this implicit tax liability. 4 I also consider how netting out income taxes due on accrued capital gains impacts wealth trends for both conventional net worth and augmented wealth over the period 1983–2016.

Netting out implicit taxes on tax-deferred assets and accrued capital gains reduces the growth in net worth and augmented wealth by between 17 and 20 percent [see Figure 3] but has little impact on their inequality. However, it does lower pension wealth and Social Security wealth inequality. The implication is that the use of pre-tax values has led to a considerable overstatement of household wealth growth.

The impact of implicit taxes varies by demographic group. Netting out taxes is generally an equalizing factor with regard to intergroup differences in pension and Social Security wealth, though less so for net worth or augmented wealth. It has a minimal effect on the Black-White ratio in net worth or augmented wealth.

Distributional Effects of Wealth Taxation

I also analyze the fiscal effects of a Swiss-type direct tax on household wealth, with a $120,000 exemption and marginal tax rates running from 0.05 to 0.3 percent on $2,400,000 or more of wealth. 5 I also analyze the wealth tax proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren with a $50 million exemption, a 2 percent tax on wealth above that, and a 1 percent surcharge on wealth above $1 billion. Based on the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances augmented with wealth data from the Forbes 400, the Swiss tax would yield $189.3 billion and the Warren tax $303.4 billion per year by my estimates. Only 0.07 percent of households would pay the Warren tax, compared to 44.3 percent for the Swiss tax. However, the effect on wealth inequality of implementing either the Swiss tax or the Warren tax is small. If the policies were in place for a single year, they would reduce the Gini coefficient by at most 0.0005. The effect of both policies on wealth inequality would grow if they remained in place for a long period of time.

The incidence of the Swiss tax differs by demographic group, falling proportionately more on older than younger families, more on married couples than on singles, and more on Whites than on others.

A potential problem stemming from a wealth tax is capital flight. However, by my estimates, the Swiss tax would reduce the average yield on household assets by only 6.2 percent. It would reduce the yield in the top bracket by 9.7 percent. These figures suggest that disincentive effects on personal savings would be very modest. In contrast, the Warren wealth tax could reduce the after-tax rate of return on investments for the top group by almost 100 percent.

Researchers

More from nber.

“ Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2019: Median Wealth Rebounds … But Not Enough, ” Wolff E. NBER Working Paper 28383, January 2021. Published in part as “ The Declining Wealth of the Middle Class, 1983–2016 ,” Contemporary Economic Policy 39(3), July 2021, pp. 461–478.

“ The Decline of African-American and Hispanic Wealth since the Great Recession ,” Wolff E. NBER Working Paper 25198, October 2018, and Review of Income and Wealth , forthcoming.

“ Valuing Assets in Retirement Savings Accounts ,” Poterba J. NBER Working Paper 10395, March 2004. Published in National Tax Journal 57(2, Part 2), 2004, pp. 489–512.

“ Taxes and the Revaluation of Household Wealth ,” Wolff E. NBER Working Paper 27328, June 2020, and J ournal of Pension Economics and Finance , forthcoming.

“ Wealth Taxation in the United States ,” Wolff E. NBER Working Paper 26544, December 2019, and Public Sector Economics 44(2), June 2020, pp. 153–178.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Featured articles

- Virtual Issues

- Prize-Winning Articles

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C40 - General

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C70 - General

- C71 - Cooperative Games

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C73 - Stochastic and Dynamic Games; Evolutionary Games; Repeated Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- C99 - Other

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D00 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- D87 - Neuroeconomics

- D89 - Other

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- E1 - General Aggregative Models

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F45 - Macroeconomic Issues of Monetary Unions

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F66 - Labor

- F68 - Policy

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- G53 - Financial Literacy

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H42 - Publicly Provided Private Goods

- H44 - Publicly Provided Goods: Mixed Markets

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- H68 - Forecasts of Budgets, Deficits, and Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H72 - State and Local Budget and Expenditures

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H76 - State and Local Government: Other Expenditure Categories

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor Markets

- J43 - Agricultural Labor Markets

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J47 - Coercive Labor Markets

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J50 - General

- J51 - Trade Unions: Objectives, Structure, and Effects

- J53 - Labor-Management Relations; Industrial Jurisprudence

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K12 - Contract Law

- K14 - Criminal Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K36 - Family and Personal Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L0 - General

- L00 - General

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L32 - Public Enterprises; Public-Private Enterprises

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- L44 - Antitrust Policy and Public Enterprises, Nonprofit Institutions, and Professional Organizations

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L67 - Other Consumer Nondurables: Clothing, Textiles, Shoes, and Leather Goods; Household Goods; Sports Equipment

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L82 - Entertainment; Media

- L83 - Sports; Gambling; Recreation; Tourism

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L91 - Transportation: General

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L96 - Telecommunications

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M10 - General

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- Browse content in M2 - Business Economics

- M21 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M3 - Marketing and Advertising

- M30 - General

- M31 - Marketing

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- M55 - Labor Contracting Devices

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N13 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N14 - Europe: 1913-

- N15 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N26 - Latin America; Caribbean

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N30 - General, International, or Comparative

- N32 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N33 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- N35 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N40 - General, International, or Comparative

- N41 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N42 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N43 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N44 - Europe: 1913-

- N45 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N50 - General, International, or Comparative

- N51 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N53 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N6 - Manufacturing and Construction

- N63 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N70 - General, International, or Comparative

- N71 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N72 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N73 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N75 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N90 - General, International, or Comparative

- N92 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N94 - Europe: 1913-

- N95 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O38 - Government Policy

- O39 - Other

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O50 - General

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O55 - Africa

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P14 - Property Rights

- P16 - Political Economy

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P39 - Other

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P50 - General

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q23 - Forestry

- Q28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General