Consumer Perceptions and Pricing Practices for Weddings

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 20 April 2021

- Volume 44 , pages 407–426, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- N. D. Albers 1 ,

- A. O. Wren 1 ,

- T. L. Knotts ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7052-3657 1 &

- M. G. Chupp 2

7151 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Weddings represent a specific consumption experience with unusual pressures (financial and emotional). Societal pressures of perfection and the experience itself, including conspicuous consumption, experience, and credence qualities, create a unique consumption and pricing environment. Study 1 provides evidence of a two-tier retail pricing approach for “regular” and “wedding” items. Study 2 suggests this phenomenon has been propagated by a tendency to attach elevated importance to wedding products. This paper documents the practice of elevated wedding pricing and offers insight into why the practice is tolerated and perpetuated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Retracted article: low prices and high regret: how pricing influences regret at all-you-can-eat buffets.

Özge Siğirci & Brian Wansink

Presence or Absence of Unit Price Display and Its Influence on Snack Food Choices

Food Retailers and Obesity

Rosemary A. Stanton

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

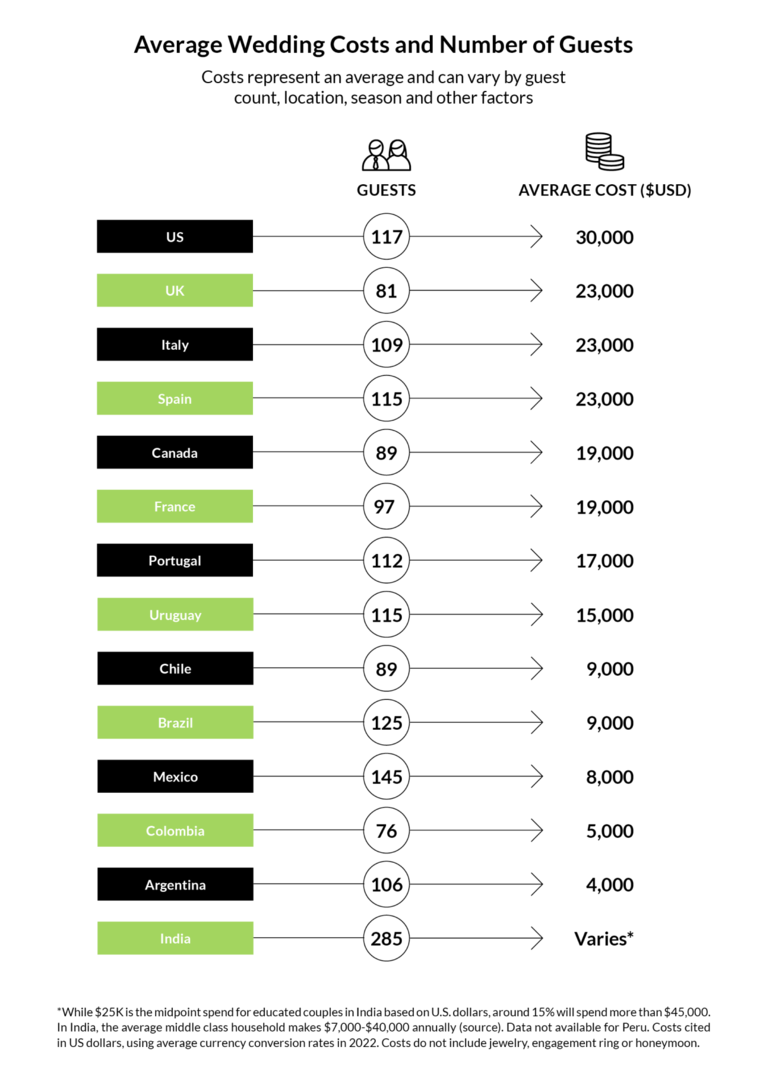

Approximately 2.23 million couples get married each year in the USA (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017 ). While extremely lavish and over the top weddings have become less common in in the early part of the century (Poquette 2010 ), the average wedding cost in the USA is still $38 700 (Goodson and Francis 2019 ). The average cost of a wedding varies tremendously depending on where the couple marries. The average can be as high as $76 944 in the Manhattan borough of New York City or as low as $17 584 in New Mexico (Jacobs 2018 ).

American consumers spend about $72 billion annually on weddings, not including the honeymoon (Segran 2018 ). Consumers spent almost $2 billion for the busiest wedding day in 2018, which was 8/18/18 (Bertram 2018 ). At least one elaborate international wedding cost more than $66 million (Erdei 2018 ). All over the world, there are massive pressures on couples and families to avoid looking cheap (Poquette 2010 ; Ward 2020 ). For example, one online planning site discourages brides from buying discounted items (O’Gorman Klein 2021 ), and American couples, on average, invite 167 guests to their wedding with 10.7 men and women as part of the wedding party (Brides Editors 2019 ).

Although some couples do not expect parents to cover the cost of the wedding, parents of the couple often feel obligated to make sure their children have the wedding of their dreams (Lepore 2020 ). Parents want to support their children’s aspirations and, in doing so, they have been known to borrow, cash in retirement savings, and/or access the equity in their homes (Lepore 2020 ). While most couples do contribute to the cost of the wedding, only about 27% of couples said they paid fully for their own weddings, often deferring the cost of wedding-related expenses and activities with credit cards and loans (McDowell 2019 ). The demand for wedding loans have quadrupled recently, and many wedding-related credit payments extend for more than three years after the wedding (Bhattarai 2019 ).

Weddings can become major productions complete with elaborate attire for the entire wedding party, limousine rental, venue rental, flowers, photographers, etc. Expenses mount because weddings are publically consumed productions. The cost of a wedding spans pre-wedding to post-wedding events, with pre-wedding events no longer limited to a bridesmaid’s luncheon or a rehearsal dinner. Pre-wedding events are likely to include a combination of engagement parties, fundraising events, bridal and couple showers, wedding party welcome events, bachelor and bachelorette parties, co-ed parties, spa visits, outdoor outings, luncheons, and dinners (Forrest 2018 ; Prendergast 2018 ). Post-wedding events, once consisting of a reception and honeymoon, now may be expanded into not only a post-wedding reception, but also after reception parties, day after brunches, and extravagant honeymoons (Brown 2017 ; Donovan 2020 ; The Knot 2020 ).

The Pressure of the Perfect Wedding

Weddings are not only financially draining, but emotionally fatiguing as well (Strauss 2019 ). While academia is quick to pan publications encouraging perfection-seeking behavior (Bigelow 2006 ; Slade 2006 ), the popular press and Internet have embraced the concept of perfection with an entire wedding magazine dedicated to this purpose (Cooper 2020 ; Ghosh and Ghosh 2010 ). Much like the myth of the perfect mother applying pressure to first time moms (Meeussen and Van Laar 2018 ; Slade 2006 ; Wilborn 1976 ), there is extraordinary pressure on “super brides” to not only be perfect, but to plan and execute the perfect wedding (Cooper 2020 ; Duncan 2016 ; Poquette 2010 ).

This pressure on brides often leads to extended demands on product selection and extensive, protracted search processes with many points of product comparisons. For example, the typical bride, planning a local wedding, will dedicate a year or more to wedding planning (Krueger 2020 ). The recommendation for planning a destination wedding can be two years or more (Shutterfly Community 2020 ).

While the Internet has dozens of wedding checklist for brides, many have 60 or more decision points where brides must make comparisons and choices (Here Comes the Guide 2021 ). When searching for the perfect wedding gown, most brides try on four to seven dresses, but others end up trying on many more (O’Gorman Klein 2021 ). The pressure for the perfect dress is so extreme that it has given rise to more brides selecting custom gowns. While custom dresses are not universally adopted, the brides who decide on a custom dress must increase their level of involvement and financial commitment (Choy and Lokar 2004 ).

Many wedding decisions are fraught with social consequences, such as who will and will not be in the wedding party or who will and will not be invited to the wedding. Along these lines, brides must choose who to involve in the decision-making processes. For decisions related to the wedding cake, wedding planners encourage brides to have friends and family sample many bakeries and contribute to the decision process for buying a wedding cake (Birdwell-Branson 2017 ). Brides are encouraged to begin the process of locating a bakery about six months before the wedding date, making appointments with at least two bakeries for tastings (Birdwell-Branson 2017 ). This can place additional pressure to please the family and friends by acquiescing to the popular choice rather than other fiscally responsible options.

According to wedding planning sites, most decisions that brides make should be thoroughly investigated. For example, selecting a florist is described as an eight-step process (Kay 2021 ). Additionally, the wedding venue is considered vital to the success of the wedding; therefore, brides are encouraged to build a venue research spreadsheet including location, capacity, availability, type, layout, rates, website, restrictions, parking, transportation, caterer, linens, tables, chairs, and media equipment availability (Levy 2019 ).

Media, social networks, and the wedding industry portray weddings as an obtainable consumer fantasy (Boden 2001 ; Mead 2008 ; Weiss 2020 ). While modern brides may feel able to choose between which wedding traditions to follow, expectations to observe family, culture, and regional traditions may still be extreme (Burvill 2019 ). The pressures of old traditions have also been replaced with new expectations. Sociologists explain that expectations on the bride are a result of social expectations and the media (Boden 2001 ; Hochschild 1998 ).

The pressure for perfection is compounded because all wedding-related events, down to the selection of table decorations, are typically captured both on video and in still photographs. The photos are supposed to capture unforgettable memories , but brides are aware that the photos and videos will also document and proclaim the quality of the decisions made long after the wedding events are concluded (Brown 2018 ). Cellphones and cameras allow untrained family and friends to capture amateur images, resulting in guests posting pictures on social media even while the wedding and reception are occurring. These photos document before and after wedding activities and are critiqued on social media (Park 2019 ).

In order to meet the societal expectations for perfection, weddings are expected to be planned on a romantic date and at a romantic church or venue filled with impeccable flowers, even if that means conducting the wedding hundreds of miles away or in a foreign country (Bertram 2018 ). The reception should be at a similarly grand location such as a mansion, historic estate, up-scale hotel, or expensive restaurant with delicious food and beverages (Forrest 2019 ; Schreiber 2020 ). In addition to the perfect wedding, evidence indicates that brides feel immense pressure to achieve personal perfection (Schank 2006 ). As the central focus of the wedding, brides are expected to be immaculate (Steer 2018 ), have a perfect body (Kovanis 2006 ), and wear an exquisite gown (Bridal 2016 ; Hoffower 2020 ). Having beautiful hands and nails, (Murray 2017 ), long flowing hair or glamorous upsweeps (Rud 2020 ; Title 2017 ), healthy, glowing skin, and flawless make-up (Levine 2020 ) are considered essential bridal features.

Consumption Behavior Impact on Pricing

Conspicuous consumption.

Based on the volume of media related to the perfection pressure for weddings and wedding-related products, it is logical to consider that a consumer might have elevated anxiety with regard to these purchases. Weddings and wedding-related products are reasonably considered to be conspicuous goods (Belk 1988 ). The conspicuousness of a wedding can be used to achieve social status (Bloch et al. 2014 ). Consumer response to conspicuously consumed goods is different from goods not consumed conspicuously. Conspicuous goods are often evaluated as priceless goods in that consumers attribute some level of intrinsic value beyond their normal market value. Priceless goods are difficult to assess in terms of an appropriate price using market-related models (Maitland 2002 ). Evidence suggests that marketers of conspicuous goods often take advantage of the social effects to charge a higher price (Amaldoss and Jain 2005b ). An extrapolation of this concept can be found in a WeddingWire post by a bride regarding the price of a wedding venue:

“… I absolutely fell in love with a place and it's $7000 for the reception and an extra $2500 for the ceremony. Is that too much? It's pretty much the place of my dreams a place I can look like an actual Disney princess at but other family members and friends say it might be a little too much. Then again they've all gotten married on beaches or in Barns (Wedding Ceremony 2018 ).”

Consumers buy goods for both material and social needs (Amaldoss and Jain 2005a ; Duan and Dohlakia 2017 ). Amaldoss and Jain ( 2005a ) explain that social needs may manifest in a consumer’s desire to appear to be exclusive or to conform. It is common among marketers of conspicuous goods to emphasize a product’s exclusivity (Pollay 1984 ).

Wedding consumption generates both needs simultaneously. Clearly, there is media and society-based pressure for the bride to make decisions that will result in the perception that her wedding is different and unique compared to all other competing weddings. Yet, brides are also expected to make appropriate decisions that will maintain traditionally expected aspects of the wedding. For example, a bride may feel compelled to have a formal, white wedding dress to conform to tradition, and yet, locate a unique and exclusive design that is remarkably different from all of her friends’ gowns, even to the point of customization (Choy and Lokar 2004 ).

Consumers’ Ability to Judge Quality

All things being equal, consumers perceive a relationship between appropriate price and product quality. As quality increases, consumers are willing to pay more for the better quality product. In the best of consumption settings, a consumer would have complete knowledge about product quality and would be willing to pay a price appropriate to the incremental level of quality. Research confirms that consumers in this setting will pay more for a product even if there is no evidence of an increase in quality or utility (Amaldoss and Jain 2005a ).

Service researchers have long acknowledged that consumers do not have complete knowledge about quality. Services are intangible goods, and hence it is difficult for customers to judge the price/quality relationships (Berry and Manjit 1996 ). Zeithaml ( 1981 ) described service quality in three levels: search, experience, and credence. At the lowest level, search quality, a consumer can judge quality before purchase. Experience quality can only be judged during consumption. Credence quality cannot be accurately judged even after consumption. Credence quality is often judged by consumers based on their satisfaction, but doubt may linger if they wonder if a different provider might have delivered a better service or good.

Ostrom and Iacobucci ( 1995 ) empirically validated relationships between the ability to estimate value accurately, the perceived importance of the purchase, and price sensitivity. Not at all surprising, consumers are more price sensitive when a purchase is not perceived to be highly important. As importance increases, however, consumers become less sensitive to increases in price. Furthermore, when the consumer is faced with an inability to judge quality accurately, consumers do not expect to offset risk with anticipated lower prices, but rather may in fact use price as a proxy for quality. Consumers are theoretically willing to spend the most on products deemed as highly important and for which measures of quality are inadequate.

Wedding-related purchases, both services and even potentially tangible goods, may represent this type of purchase. Clearly, wedding purchases are considered as important. The ability to judge quality reasonably may be emotionally and psychologically hindered by the pressure for perfection. Conceivably, all product purchases fall short of perfection. Consumers striving for a perfect wedding may consider the highest priced item to be the closest to perfect.

Consumer Pricing Acquiescence

If vendors or venues charge more for a wedding than another event, they could be engaging in price discrimination. A price discrimination strategy is a strategy to sell products (identical or not) to different people at different prices. According to Paczkowsk ( 2018 , p. 5), legally, price discrimination is described in three forms or degrees.

“First-degree: Price varies by how much each consumer is willing and able to pay for the product.

Second-degree: Price varies with the amount purchased using a pricing schedule which is not a linear function of the quantity.

Third-degree: Price varies by consumer segments. This is a common form of price discrimination.”

Pricing by consumer segment would be the type of price discrimination that might be used in wedding price discrimination scenarios. Most often, price discrimination is legal unless it violates US antitrust law. The Act that prohibits unlawful price discrimination is the Robinson-Patman Act (Robinson-Patman Act 1936 ).

Empirical evidence confirms that consumers are often outraged when they believe that they are being charged unfairly. Concerns of price gouging (the charging of inappropriately high prices) have been levied against banking (Washington 2006 ), pharmaceutical companies (Greene and Padula 2017 ; Weissman 2004 ), and the oil and gas industry (Deck and Wilson 2004 ; Noel 2017 ). However, consumer response may be related to the degree the consumer believes the increases are unjustified (Deck and Wilson 2004 ; Rottier et al. 2003 ).

A 2016 study from Consumer Reports found that 28% of vendors in different areas of the USA quoted a higher price for weddings compared to an otherwise identical anniversary party (Stanger 2016 ). An investigation in Australia revealed a similar markup. It showed that venues, the priciest portion of any wedding budget, charged more in 50% of cases (Browne 2014 ).

Wedding consumers have not expressed the same level of outrage as consumers in the forementioned cases. The wedding industry is less constrained by repeat customers, and consumers are inexperienced customers in this category. Consumers have limited basis of comparison on which to evaluate if the price being charged is fair. Furthermore, the level of perceived importance and the inability to judge quality adequately interfere with a consumer’s ability to determine fair value.

Cashing In on Wedding Myths

Why might companies charge more for weddings than for other events? Potentially more than consumer naiveté drives supplier expectations for higher prices. Venues and producers may charge more for a myriad of reasons. Some providers see wedding consumers as higher maintenance, demanding more time and attention compared to consumers of other similar sized events (Malone 2017 ). Vendors may perceive a higher legal liability given that unhappy couples are historically more likely to sue than consumers of non-wedding events (Malone 2016 ). Additionally, weddings have a far higher level of injuries and property damage than other kinds of events, often resulting from excessive alcohol consumption (Malone 2017 ). Finally, wedding consumers are more likely to request a higher level of customization than their non-wedding counterparts are requesting. High levels of customization (e.g., napkins that are a specific shade of pink, custom designed centerpieces) are more expensive (Rampell 2013 ). But clearly some price differences are not attributable to cost of supply.

The social and media pressures for bigger, better, and more elaborate weddings have created a consumption environment supporting an upward spiral of expenditures. While products and services for any event can become expensive, especially with large and or lavish events, wedding expenses seem to be disproportionately high. It is unclear if the disproportionately higher prices are a result of liability insurance and demanded customization or if vendors are charging more for identical products. While many researchers have examined unethical pricing methods in general, there has been an almost total absence of academic research in the area of wedding-related pricing. Academic researchers, across a wide range of disciplines, have largely ignored the psychological and consumption experiences of weddings.

Wedding prices could be elevated from a silent price markup used by retailers and service providers. Rampell ( 2013 ) documents the experience of an economics professor, Austan Goolsbee, who was originally quoted a price for an event, but was up charged to 150% of the original quoted price when he disclosed the setting was a wedding. Rampell ( 2013 ) concluded given the inexperience of the consumer purchasing for a “once in a lifetime” event that vendors can pressure sentimental consumers to avoid looking cheap on the most important day of their lives. He extrapolates that even though the Federal Trade Commission has required funeral homes to provide itemized price lists to avoid this very type of hard selling that uses guilt and emotion to drive up spending, the FTC has not extended the same requirements to wedding vendors. Presumably, weddings are not standardized enough to make this practice as useful (Rampell 2013 ). One example would be the observed case where a formalwear store quoted different prices for dye-able shoes with a higher price for a wedding with a long turnaround time and a lower price for identical shoes from the same store for a prom even though the time frame was rushed.

Research Questions, Hypotheses, and Methodology

The research for this project was conducted in two separate studies. The first study was an exploratory examination of wedding-related products. The purpose of this study was to explore the degree to which sellers and retailers were actually using the conspicuous nature and social effects associated with wedding-related products to charge higher prices for their goods. Amaldoss and Jain ( 2005b ) provide the foundational theory for this exploration. The second study was conducted after the first study confirmed the disparity in prices between regular and wedding-related products. The second study examined consumer perceptions of importance and price expectations for wedding-related purchases. The purpose of this study was to explore the degree to which brides elevate the perceived importance of products purchased for their weddings relative to non-bride consumers. Additionally, the second study considered perceptions of appropriate pricing by brides compared to non-brides.

Study 1—Qualitative Exploration of Price Differences

The first study was an exploration of actual prices charged for wedding-related items relative to identical non-wedding items. No previous studies were found that specifically, empirically documented the differences in prices between wedding-related items relative to identical non-wedding items. The examples for this study were collected in matched sets (one wedding item and one non-wedding item) where prices between the two differed. Prices of products designated as wedding items were compared to prices of products that were not designated as wedding items. Sets were collected nationwide from a wide range of product categories. Obviously, there were cases when retailers did not have a price difference between products, but there were many examples where retailers did have differences. Products that were offered specifically in a forced bundle or tie-in were not included in this study because of the difficulty in attributing a specific price to a specific item.

Extreme caution was utilized to insure that comparisons were made between effectively identical items. In every pair, the prices for both products in the pair were obtained from the same seller. Items were matched specifically on brand and features. Great care was taken to ensure that the wedding item in the pair did not include any special features, add-ons, customization, or extra services. In most cases, the products were identical including the same brand, the same model number, the same color or color-options, and/or the same time duration. In one case, the Internet advertisement for the two items in the match set even contained the same typographical error in the two different product descriptions. By necessity, we excluded all providers who specialized in only wedding items because paired sets could not be obtained.

Pairs were located using a variety of methods. One common approach was to visit online retail sites that offered products designated as wedding-related and products which were not so designated. Items were located by following a “wedding” link and recording pricing information. The paired item was then located by looking for identical items that were offered by the company. This was done without following the “wedding” link. For example, on one online jewelry site, a crystal necklace was recorded from the “bridal” link at a price of $70. The site was exited and revisited, but the “bridal” link was not followed. The link to “necklaces” was followed instead. The same necklace (identical description and identical stock number) was located. The price obtained from the non-wedding link was $41.

In addition to obtaining examples from websites, price quotes were obtained over the telephone. In such a case, identical scenarios were provided with the only difference being the occasion of interest. For example, several churches were contacted to obtain the price of renting the church for a Friday evening and entire following Saturday. The pairs of prices were obtained for the same church office, for same date of interest, and for the same length of time. In the case of the wedding, the event was described as a wedding; in the other case, the event was described as a renewal of marriage vows. The price information specifically excluded payments to the clergy, payments to the providers of music, etc. The price included only the rental of the sanctuary. The rental price from churches was as much as $700 more for a wedding.

Some of the examples were obtained by email quotations. In such a case, identical scenarios were provided with the only difference being the occasion of interest. For example, a limousine service provider was contacted twice using the company’s online quote form. In both cases the time and date, the length of time for rental, the number of people, the description of the desired limo, etc. were all identical. The two pickup locations were on the same block of the same street. The quotes were placed using two different contact names, with different home addresses and different return email addresses. The only difference in the request was one request for a wedding transfer and the other for a night on the town. All extras were specifically excluded from the price estimates. The quote from one company for limousine rental for wedding transfers, with a four-hour minimum, was $900. The night on the town was quoted pricing for the first two hours at $225, the third hour at $150, and the fourth hour free ($600).

Some of the examples were obtained in the retail store. The only difference in the request was the intended event. For example, the price for a pair of dye-able shoes was obtained from a store offering bridal and formal wear. The price of the shoes was requested for bridesmaids in a wedding (priced at $80). The second price was obtained from the same store, from the same salesperson on the same day, for the same shoes except the price request was for an upcoming prom (priced at $60).

While some sellers made no effort to disguise the fact that they were selling identical or virtually identical items at two different prices, others were less forthcoming. One of the methods used to disguise the price differential was to quote the wedding item in a different quantity from the non-wedding item. For example, small containers of bubble solution were sold by one company to both wedding planners and to birthday party planners. The birthday party favors were sold in lots of 15 for $15. The wedding favors, which were identical in every aspect except for price, were sold in lots of 25 for $31.25. Another approach for misdirecting consumers was the use of discounts. In many situations, discounts were offered to non-brides that were not offered to brides. For example, one stationary retailer offered free return-address printing for monogrammed note cards that were not identified as wedding. The wedding customers, purchasing identical note cards, paid an additional $1 per envelope for this type of printing.

Wide varieties of examples were obtained using these methods. A t -test comparison of the cumulative set of observed prices (see Table 1 ) indicated that the differences were significant at the 0.01 level across the observations. The average percent difference associated with a product being designated as wedding was 53.68% higher than non-wedding products. Table 1 provides a list of the examples obtained for Study 1.

Study 2—Quasi-Experimental Study of Perceptional Differences

While the first study demonstrated that suppliers do market wedding-related products at higher prices, there are conflicting potential reasons. One research found that by 2009, no previous sociological research in the USA had been conducted on weddings although much has been written on marriage (Ingraham 2009 ). Currie ( 1993 ), a Canadian sociologist, reported a similar absence of research. The omission was considered to be remarkable in light of the role weddings play in our culture (Ingraham 2009 ). A disparity was reported between the focus that weddings receive in the media and the void present in the research. Popular press offers different insight than past empirical research. When pressures to reduce costs come from others, some brides turn to the Internet to support extravagant spending where they will get a wide variety of responses (Wedding Ceremony 2018 ). While some respondents recommend responsible spending, many others tell the bride that she “should do what makes you happy,” offer examples of how the bride could spend even more, or encourage the bride to go over budget.

The second study in this research was performed to help bridge this gap. Clearly, there are practices that indicate that vendors are able to upcharge consumers, but the lack of outrage on the part of consumers warrants additional insight. Do wedding consumers pay more because they are unaware of the difference (e.g., the consumers do not bother to shop and compare or take advantage of reasonable discounts)? Previous research suggests otherwise (Hwang et al. 2014 ). Furthermore, the increased availability for customization, including even the wedding dress (Choy and Lokar 2004 ), suggests that brides do shop and compare, but may bypass readily available products and select custom options regardless of the price differential. Potentially, the higher price actually could be desired or expected because of the social costs associated with weddings. Do higher prices become warranted by an inability of the consumer to judge quality and lead consumers to rely on price as a proxy? Similarly, does the extreme pressure of the conspicuousness of the event drive brides to pay higher prices as a means of communicating the quality of the event? The first step in understanding the situation is to develop a deeper understanding of what brides are willing to pay and comparing what non-brides are willing to pay for comparable items. The second study attempts to shed light on the consumer perceptions of importance and value which underlie the decision-making process. The wealth of popular press literature, along with several studies, suggests elevated levels of importance associated with wedding planning.

Much of the pressure associated with expectations of perfection is centered on the bride. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

H1: Brides will perceive the importance of products intended for use in a wedding as greater than non-brides will perceive the importance of similar products intended for events other than a wedding.

Additionally, previous research has indicated that consumers of products identified as conspicuously consumed and of high levels of importance may be valued more highly. Consumers facing these conditions are often less price sensitive. The combination of conditions a bride faces, including conspicuous consumption, high importance, and limited ability to measure quality, has been associated with a positively sloping demand curve. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

H2: Brides making product choices for a wedding will be willing to pay more for those products than non-brides making product choices for events other than weddings.

Data Collection

A quasi-experiment was conducted to test these hypotheses. Respondents were sorted non-randomly into two groups of consumers that were as homogeneous as possible with the exception that one group was planning a wedding and the other group was not. To maintain maximum homogeneity, only women in an age range of 18 to 30 were included in this study. Respondents were contacted by using a paid electronic Qualtrics panel.

Data were collected using an online survey. Potential respondents were directed to a web link. The first questions were screening filter questions that removed off-target respondents. Female respondents who indicated that they were single, engaged, and planned to be married for the first time within 12 months were routed to the wedding survey. Female respondents who indicated that they were single, not engaged, and did not have plans to be married within the next 12 months were routed to the special event survey. The special event was described as an important formal event. Other than the event, the questions were largely the same. Each survey began with a brief description of the context in which the respondent would answer the questions in order to standardize characteristics. Brides were asked to answer the questions in the survey in the context of planning a formal wedding for 200 guests. Non-brides were asked to answer the questions in the survey in the context of a major event, such as a wedding anniversary, fundraiser, or significant birthday for 200 guests. The questions reiterated and referenced the context.

In order to examine the hypotheses, five different products were used in this study: dresses (wedding or formal), cakes, invitations, floral centerpieces, and corsages. The survey examined two major issues of interest to this study, perceived importance and perception of appropriate pricing. The respondents were asked to assess the perceived importance of each product on a 5-point Likert-type scale (range from “not at all important” to “absolutely necessary”). For example, respondents were asked, “For the event described above, how important is a (wedding) cake for the event to meet your expectations?” Additionally, the respondents were asked to express the maximum reasonable price to pay for each product described.

Data were collected from 211 total female respondents who fell within the age range of 18 to 30. There were 106 respondents who were not engaged to be married and 105 respondents who were planning weddings. Following a desk edit of the data, several responses were removed. There were 102 women engaged to be married included in the study and 103 women who were not engaged. The average age of brides was 25.1 while the average age of the non-brides was 23.8. Men and women outside the age bracket were not invited to complete the survey.

Data Analysis and Results

The data were considered by comparing the responses from brides to non-brides. The mean responses from the two groups were compared using t -test comparisons for each product category. In keeping with the sociology and popular press literature, this study discovered that products for weddings have elevated importance.

Both brides and non-brides considered all of the products to be important to the success of the event. Across all five categories, the brides attributed more importance to each purchase than non-brides, but brides and non-brides were not significantly different in the importance ratings for the cake, the invitations, the centerpiece, and the corsage. However, the dress was considered to be significantly more important for the wedding dress (4.46) than the special event formal gown (3.39). These findings suggest that traditional wedding purchases remain important for brides, but not significantly more so than women planning other large events with the exception of the wedding dress. These findings offer partial support for Hypothesis 1. These findings are summarized in Table 2 .

Even though both brides and non-brides rate the importance of most wedding purchases similarly, the price expectations from brides are substantially higher than non-brides. Brides were more inclined to be prepared to pay more for the products described. For all five products, brides were statistically significantly inclined to set a higher average mean price for the products. On average, brides were willing to pay $911.10 dollars for a cake compared to a mean maximum price of about $561.40 for the non-brides (significant at the 0.01 level). Brides were willing on average to pay $553.40 for a floral centerpiece, which non-brides drew the line at $264.30 (significant at the 0.01 level). Additionally, brides were willing to pay $169.10 for a single mother’s corsage at the wedding, but mothers of non-brides expected a $75.11 corsage at an anniversary party (significant at the 0.05 level). Perceptions of invitation prices for brides were $450.90, and non-brides expected to pay a maximum of 208.70 (significant at the 0.01 level). The largest difference was observed for the dress. Brides indicated that they would pay no more than $2989.00, and non-brides would pay no more than $561.40 (significant at the 0.01 level). These findings offer strong support for Hypothesis 2 and are summarized in Table 3 .

Comparing Expectations to Actual Prices

A comparison of the respondents’ price cap and the reported actual expenditures as they were reported by The Knot (Table 4 ) and WeddingWire (Table 5 ) provides additional insight. The data from the respondents were compared on three categories, including invitations, wedding cake, and dress. These three categories were the only three with exact direct comparisons.

In one category, invitations, the maximum reasonable price expressed by the brides ($450.90) was compared to the two actual prices reported ($386 on The Knot and $550 on WeddingWire). The maximum price brides reported they would pay fell between the published expenditures. While the anticipated price from the brides was greater than the reported price on The Knot (16.81% difference), the bride maximum price was lower than the report by WeddingWire (−18.02% difference). This result is likely due to the decreasing value of paper invitations resulting from the willingness of some to use paperless products reducing demand for formal paper invitations (Kellogg 2020 ).

For a wedding cake, brides are willing to pay more than the brides from the previous year actually paid. Respondent brides indicated that they would pay $911.10 for a wedding cake, but prices paid by brides previously were reported in The Knot as $528 and $550 in WeddingWire. The percent difference was high, with brides willing to pay between 65.65% (WeddingWire) to 72.56% more (The Knot) than was observed in the previous year. Brides are prepared to pay much more than the actual prices charged for a wedding cake.

Additionally, brides are willing to pay a maximum of $2989.00 for a dress. The reported actual price paid by The Knot was $1631 and $1700 by WeddingWire. Brides’ expectations on what they are willing to pay is substantially more than brides the previous year actually paid. The percent difference that brides are willing to pay was remarkable (83.26% compared to The Knot report and 75.82% compared to WeddingWire).

Overall, respondent brides are willing to pay substantially higher prices for weddings than even actual prices paid by brides during the previous year.

Implications, Limitations, and Conclusions

The findings from the first study suggest that at least some providers of wedding-related products are using a significantly different pricing structure for products designated as wedding compared to non-wedding products. The literature on quality and conspicuous consumption gave rise to the possibility that brides would be willing to pay a higher price than was necessary when making purchases for weddings. This research appears to provide some support for that practice. When pricing differentials are used for wedding-related products, the percentage difference is about 53.7%. The fact that brides are willing to pay even more than what is charged presumably offers insight into why engaged couples are not outraged or resentful of the higher prices they pay for wedding products and services. The exploratory study specifically excluded sites where only wedding-related products were offered because these sites did not offer an opportunity to obtain side-by-side comparisons. Future research might broaden the scope of this study to examine closely wedding-only providers. Wedding-only providers represent a large portion of the sales in these product categories.

The price differences were observable across a wide range of products and services. The examples included products intended for use at the wedding (such as yacht rental and floral boutonnieres), at the reception (such as disposable cameras and table place cards), and for the honeymoon (such as casual bride and groom attire). They were products not only intended specifically for the bride (such as a formal wedding dress and bridal jewelry), but also for other bridal party members as well (such as bridesmaid shoes and dresses). They included both services (such as limousine rental and honeymoon packages) and tangible products (such as almonds and cameras). The examples ranged from products of modest costs (such as a few dollars for a votive candle) to items costing thousands of dollars (such as sunset sailboat weddings). In many cases, no effort was made on the part of the retailer to disguise or to differentiate the two products in the pair. In other cases, sellers used various methods of deception.

While both brides and non-brides expressed importance on products purchased for use at a planned event, brides placed a substantially higher importance on the bridal gown than non-brides placed on a formal event dress. The respondents expressed significant differences on the maximum acceptable prices for items used for a wedding compared to items used at another conspicuous event. This willingness to spend more for weddings is likely to be based on the substantial and persistent pressure on brides to achieve perfection when planning weddings that does not exist on people planning other celebratory events. The willingness to spend more has created an environment where vendors, retailers, and service providers are able to up charge wedding-related products and services without censure or negative consequences.

For all products considered, except the dress, brides were willing to pay on average 231.23% more than non-brides were. With regard to the dress, brides were willing to spend up to 532.42% more than non-brides on a formal special event dress. The perceived value gap between brides and non-brides is even greater than actual retail markup observed in Study 1 (53.7%). These findings indicate that sellers of wedding-related products are keenly aware of the degree to which the market will tolerate higher prices.

Policy Implications

Price discrimination in the wedding industry can be frustrating for the bride, groom, parents, and members of the wedding party. It certainly must feel unfair, but it is not just the feelings of annoyance that plague an engaged couple. Price discrimination is a widely recognized problem, or a benefit from the seller’s point of view, in the wedding goods and services industry. Some might even say it is a widely accepted practice by consumers, the wedding industry, and the media.

There are several ways to address the issue of price discrimination in the wedding industry. At the top is action by the Federal Trade Commission. Although, the FTC has not acted on pricing in the wedding industry, it has imposed a rule on another life-event business. The FTC’s so-called Funeral Rule requires funeral homes to provide itemized price lists to bereaved family members, to allow the purchase of separate items not as part of a package, and to allow the use of caskets or containers purchased by the family from an outside source, among other things. One of the main reasons for this rule is to allow consumers to comparison shop. A similar rule by the FTC could address price discrimination issues in the wedding industry.

Another way to address concerns about wedding pricing is through state statutes or local ordinances. Several states have recognized the problem of price discrimination based on gender. For example, in the 1990s, California recognized the numerous studies that showed that women pay a so-called gender tax or pink tax in certain arenas of commerce (Warren 1995 ). One survey by the Assembly Office of Research found that 40% of hair salons charged women from $2.50 to $25 more for similar services. Dry cleaners charged an average of $2 more to launder a woman’s shirt, the survey found. Other research has shown that department stores routinely make women pay for alterations to business suits. Men’s suits, by contrast, often are altered free (Warren 1995 ). California’s law, the Unruh Civil Rights Act, requires certain businesses, such as hair salons, tailors, and dry cleaners, to clearly and conspicuously post pricing lists for their services. The law also applies to both goods and services.

Similarly, New York passed a law last year that went into effect on September 30, 2020. The law prohibits charging different prices for goods or services that are substantially similar but are marketed to different genders. The law applies at all levels of the supply chain. Substantially similar goods are defined as those that “exhibit little difference in the materials used in production, intended use, functional design and features, and brand” (Friedman et al. 2020 ). Finally, Miami-Dade county in Florida has a law comparable to New York’s. The Gender Pricing Ordinance prohibits differential pricing for similar goods based solely on a person’s gender. Businesses are allowed to charge different prices if a good or service involves more time or cost.

Although these state laws and local ordinances do not specifically address weddings, businesses should be on notice that the laws could be applied or expanded to include the wedding industry. Most products and services in the wedding industry are marketed to and purchased by women. As a result, the pink tax laws could easily be applied to gender-biased transactions involving weddings.

Consumer Implications

Weddings are usually a once in a lifetime event. The goods and services purchased in connection with a wedding are not as familiar to consumers as regular, every-day goods and services. For the most part, consumers know how to comparison shop when it comes to regular foods and clothes as opposed to a wedding cake or wedding dress. Most brides and groom are just not familiar with the normal costs of a wedding.

As wedding videographer, Johnny Harris ( 2016 ), states, “Add in that many wedding vendors don't post prices on their websites and you start to see why wedding planning can involve so much stress: The familiarity and transparency we rely on for other purchases just isn't there.” One common tactic wedding vendors use to cover up high costs of weddings is to present wedding goods and services as an event so that brides and grooms fall in love with the overall experience before being told the prices. This process of stalling on revealing the price is common in the wedding industry (Harris 2016 ).

Consumers can protect themselves by asking for price lists up front. Wedding vendors can post the prices of goods online and provide the individual cost of goods in the information given to the bride and groom. Some states are already considering mandating these practices by law or regulation.

Limitations and Future Research

This project is limited in scope. Future research should expand both the breadth and depth of this study. Future research might expand the number of products included. Additionally, research should examine the degree to which there are differences between tangible products and services. This study did not examine pricing from the perspective of the groom or parents funding the wedding, and future research might compare differences in expectations between brides and grooms and/or parents.

Furthermore, pricing is complicated in event planning. While Study 1 carefully controlled for exactly identical items from the exact same supplier, this was not possible with Study 2. Future research may consider the hidden costs that could arise in a wedding (such as higher levels of damage at a reception hall) that might not occur for other social events. Additionally, it is possible that brides demand higher quality to achieve satisfaction (e.g., demanding roses instead of carnations in a center floral piece) which created a difference in cost of supply between those planning weddings and those planning other social events. Finally, this study does not address bundling, in particular forced bundling, but future research may need to explore the policy concerns in wedding bundling.

In Study 2, this research does not address the vastly different search process untaken by individuals planning weddings and individuals planning other large social events. A deeper understanding of the relationship between the amount of time a bride spends researching and planning a wedding may be needed. Future research might explore the relationship between actual spending on weddings and the time committed to planning the event.

Conclusions

While this study does generate additional questions, it provides early insight into consumer perceptions and expectations with regard to wedding-related spending. The massive amount of pressure placed on brides appears to be generating the anticipated outcomes of high levels of importance attribution and decreased price sensitivity for wedding-related goods. The study provides exploratory examples validating a tendency of retailers to charge a higher price for wedding-related goods and a tendency for brides to be vulnerable to accepting those differences, even when there is no noticeable or actual quality difference.

Amaldoss, W., & Jain, S. (2005a). Conspicuous consumption and sophisticated thinking. Management Science, 51 (10), 1449–1467.

Article Google Scholar

Amaldoss, W., & Jain, S. (2005b). Pricing of conspicuous goods: A competitive analysis of social effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 42 (1), 30–42.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (2), 139–168.

Berry, L. L., & Manjit, S. Y. (1996). Capture and communicate value in the pricing of services. Sloan Management Review, 37 (Summer), 41–51.

Google Scholar

Bertram, C. (2018). Saturday busiest wedding day of the year, at a cost of almost $2 billion. Bloomberg Pursuits . Retrieved from https://bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-16/over-1-billion-will-be-spent-on-weddings-this-weekend . Accessed 22 2020.

Bhattarai, A. (2019). Married to debt: couples are taking out loans to pay for their weddings. The Washington Post . Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/06/19/married-debt-couples-are-taking-out-loans-pay-their-weddings/ . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Bigelow, D. (2006). A review of a more perfect union: How I survived the happiest day of my life. Library Journal, 131 (1), 138.

Birdwell-Branson, J. (2017). All you need to know about wedding cakes: Tastings and ordering. Weddingbee . Retrieved from https://www.weddingbee.com/ceremony-and-reception/all-you-need-to-know-about-wedding-cakes-tastings-and-ordering/ . Accessed 16 Jan 2021.

Bloch, F., Rao, V., & Desai, S. (2014). Wedding celebrations as conspicuous consumption signaling social status in rural India. The Journal of Human Resources, Summer , 675–695.

Boden, S. (2001). Superbrides: Wedding consumer culture and the construction of identity. Sociology Research Online, 6 (1), 1–14.

Bridal, G. S. (2016). Why the wedding dress is the most important thing of all. Medium . Retrieved from https://medium.com/@GeorginaScottBridal/why-the-wedding-dress-is-the-most-important-thing-of-all-85452df51ea8 . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Brides Editors. (2019). This is what American weddings look like today. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/gallery/american-wedding-study . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Brown, A. (2017). Everything you need to know about the 9 most common wedding-related events. Martha Stewart . Retrieved from https://www.marthastewartweddings.com/617134/pre-and-post-wedding-parties-events . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Brown, A. (2018). Is wedding videography really worth the splurge? Martha Stewart . Retrieved from https://www.marthastewartweddings.com/630985/is-wedding-videography-worth-the-splurge . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Browne, K. (2014).What costs more - a wedding or a party? CHOICE . Retrieved from https://www.choice.com.au/shopping/shopping-for-special-occasions/weddings/articles/wedding-costs . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Burvill, L. (2019). Everything you need to know about wedding traditions in 2020. British Vogue . Retrieved from https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/wedding-traditions . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). FastStats - Marriage and Divorce . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm . Accessed 22 May 2020.

Choy, R., & Lokar, S. (2004). Mass customization of wedding gowns: Design involvement on the internet. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 22 (1-2), 79–87.

Cooper, G. (2020). Perfect wedding magazine . Retrieved from https://perfectweddingmagazine.com/ . Accessed 22 May 2020.

Currie, D. (1993). Here comes the bride: The making of a “modern traditional” wedding in Western culture. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 24 (3), 403–421.

Deck, C. A., & Wilson, B. J. (2004). Economics at the pump. Regulation, 27 (1), 22–30.

Donovan, B. (2020). Wedding after-party planning: How to host a budget-friendly celebration. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/story/budget-friendly-after-party . Accessed 22 May 2020.

Duan, J., & Dohlakia, R. R. (2017). Posting purchases on social media increases happiness: The mediating roles of purchases’ impact on self and interpersonal relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34 (5), 404–413.

Duncan, M. (2016). Wedding industry. In C. L. Shehan (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies (pp. 2041–2044). Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Erdei, I. (2018). TOP 10 most expensive weddings in history. Business Review . Retrieved from https://www.business-review.eu/lifestyle/top-10-most-expensive-weddings-in-hystory-170217 . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Forrest, K. (2018). All the pre-wedding parties you need to be aware of . WeddingWire . Retrieved from https://www.weddingwire.com/wedding-ideas/all-the-pre-wedding-parties . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Forrest, K. (2019). How to choose a wedding venue. WeddingWire . Retrieved from https://www.weddingwire.com/wedding-ideas/how-to-choose-a-wedding-venue . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Friedman, C., Yaghi, M., Ludaway, N.O., Albracht, J., & Trivette, S. (2020). New York law prohibits gendered pricing, retail and consumer products. Crowell Moring . Retrieved from https://www.retailconsumerproductslaw.com/2020/11/new-york-law-forbids-gendered-pricing . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Ghosh, S., & Ghosh, M. (2010). The making of an EPIC wedding film. EventDV, 23 (1), 40–46.

Goodson, L., & Francis, K. (2019). The 2019 WeddingWire newlywed report. WeddingWire . Retrieved from https://go.weddingwire.com/newlywed-report/2019 . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Greene, J., & Padula, W. (2017). Targeting unconscionable drug prices—Maryland’s anti-price-gouging law. New England Journal of Medicine, 377 (2), 101–103.

Harris, J. (2016). What I’ve learned about wedding prices from working in the industry. Vox . Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2015/7/30/9061419/weddings-so-expensive-economics . Accessed 10 Jan 2021.

Here Comes the Guide. (2021). 90-day wedding planning checklist. Here Comes THE GUIDE . Retrieved from https://www.herecomestheguide.com/wedding-ideas/90-day-wedding-planning-checklist . Accessed 16 January 2021.

Hochschild, A. R. (1998). The sociology of emotion as a way of seeing. In G. Bendelow & S. Williams (Eds.), Emotions in Social Life: Critical Themes and Contemporary Issues (pp. 3–16). London: Routledge.

Hoffower, H. (2020). Five easy steps for finding your perfect wedding dress. Brides . Retrieved https://www.brides.com/story/how-to-find-the-perfect-wedding-dress . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Hwang, Y., Ko, Y., & E., & Megeheeb, C. (2014). When higher prices increase sales: How chronic and manipulated desires for conspicuousness and rarity moderate price’s impact on choice of luxury brands. Journal of Business Research, 67 (9), 1912–1920.

Ingraham, E. (2009). White weddings: Romancing heterosexuality in popular culture (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Jacobs, S. (2018). The average wedding cost in America is over $30,000 – But here’s where couples spend way more than that. Business Insider . Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/average-wedding-cost-in-america-most-expensive-2018-3 . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Kay, L. (2021). Eight steps to finding your florist. The Knot . Retrieved from https://www.theknot.com/content/steps-to-finding-wedding-florist . Accessed 16 Jan 2021.

Kellogg, K. (2020). How to send digital wedding invitations. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/story/unique-ways-send-paperless-wedding-invitation . Accessed 22 May 2020.

Kovanis, G. (2006). The princess brides: January is the busiest time of the year for newly engaged women searching for the perfect wedding dress. Knight Ridder Tribune Business News, 1 .

Krueger, A. (2020). How long does it take to plan a wedding? Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/how-long-it-takes-to-plan-a-wedding-5087258 . Accessed 17 Jan 2021.

Lepore, M. (2020). Here’s how much parents pay for their children’s weddings. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/story/how-much-parents-pay-for-their-childrens-weddings . Accessed 22 May 2020.

Levine, H. (2020). 17 tips for glowing wedding skin: How to get your skin in top-notch shape before your wedding. The Knot . Retrieved from https://www.theknot.com/content/tips-to-glowing-wedding-skin . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Levy, K. (2019). How to choose a wedding venue (no, really). A Practical Wedding . Retrieved from https://apracticalwedding.com/choose-a-wedding-venue . Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

Maitland, I. (2002). Priceless goods: How should life-saving drugs be priced? Business Ethics Quarterly, 12 (4), 451–480.

Malone, S. (2016). What to think about before signing your wedding venue contract. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/story/wedding-responsibility-and-liability-sandy-malone . Accessed 16 Jan 2021.

Malone, S. (2017). Why venues charge wedding more. Sandy Malone Weddings . Retrieved from https://weddingrealitycheckwithsandymalone.libsyn.com/-why-venues-charge-weddings-more . Accessed 24 May 2020.

McDowell, E. (2019). A staggering percentage of couples are going into debt to pay for their weddings — Here are the countries where the problem is the worst. Business Insider . Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/wedding-cost-go-into-debt-pay-couples-2019-7 . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Mead, R. (2008). The perfect day: The selling of the American wedding . New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Meeussen, L., & Van Laar, C. (2018). Feeling pressure to be a perfect mother relates to parental burnout and career ambitions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 2113.

Murray, B. (2017). Bridal beauty bootcamp: A guide to the perfect manicure. Harper’s Bazaar . Retrieved from https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/beauty/make-up-nails/a38675/wedding-nails-manicure-tips . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Noel, M. (2017). Retail gasoline markets. In E. Basker (Ed.), Handbook on the economics of retailing and distribution (pp. 392–412). Cheltenham: Edward Edgar Publishing.

O’Gorman Klein, K. (2021). 10 mistakes brides make when dress shopping. Bridal Guide . Retrieved from https://www.bridalguide.com/fashion/wedding-dress-shopping-guide/wedding-dress-shopping-tips . Accessed 16 Jan 2021.

Ostrom, A., & Iacobucci, D. (1995). Consumer trade-offs and the evaluation of services. Journal of Marketing, 59 (1), 17–29.

Paczkowsk, W. R. (2018). Pricing analytics: Models and advanced quantitative techniques for product pricing . Abindgon: Routledge.

Park, A. (2019). How social media plays a role in almost every aspect of a wedding. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/story/american-wedding-study-social-media-number-1-resource . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Pollay, R. (1984). The identification and distribution of values manifest in print advertising 1900-1980. In R. E. Pitts Jr. & A. G. Woodside (Eds.), Personal values and consumer psychology (pp. 111–135). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Poquette, B. L. (2010). Going to the chapel. Library Journal, 134 (20), 60–62.

Prendergast, A. (2018). Pre-wedding party timelines. WeddingWire . Retrieved from https://www.weddingwire.ca/wedding-ideas/pre-wedding-party-timeline%2D%2Dc569 . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Rampell, C. (2013).The wedding fix is in . The New York Times Magazine . Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/08/magazine/the-wedding-fix-is-in.html . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Robinson-Patman Act. (1936). 15 U.S.C. § 13 et seq.

Rottier, H., Hill, D. J., Carlson, J., & Griffin, M. (2003). Events of 9/11/2001: Crisis and consumer dissatisfaction response styles. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 16 , 222–232.

Rud, M. (2020). The 8 best clip-in hair extensions that will help you score your perfect bridal ‘do. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/best-wedding-hair-extensions-4843055 . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Schank, H. (2006). A more perfect union: How I survived the happiest day of my life . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Schreiber, S. (2020). 25 unexpected wedding food ideas your guests will love. Martha Stewart . Retrieved from https://www.marthastewartweddings.com/341786/11-unexpected-wedding-food-ideas . Acccessed 22 May 2020.

Seaver, M. (2019). The national average cost of a wedding is $33,931. The Knot . Retrieved from https://www.theknot.com/content/average-wedding-cost . Accessed 16 Jan 2021.

Segran, E. (2018). Zola’s plan to take on the $72 Billion wedding industry. Fast Company . Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/90212949/zolas-plan-to-take-on-the-72-billion-wedding-industry . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Shutterfly Community. (2020). How long does it take to plan a wedding? Shutterfly . Retrieved from https://www.shutterfly.com/ideas/how-long-does-it-take-to-plan-a-wedding/ . Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

Slade, A. (2006). Perfect madness: Motherhood in the age of anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45 (1), 123–125.

Stanger, T. (2016). Get more wedding for your money. Consumer Reports . Retrieved from https://www.consumerreports.org/weddings/get-more-wedding-for-your-money/ . Aaccessed 2 April 2021.

Steer, C. (2018). Wedding make-up tips – the dos and don’ts you need for your big day. Marie Claire . Retrieved from https://www.marieclaire.co.uk/life/weddings/wedding-make-up-tips-2-101116 . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Strauss, A. (2019). From wedding bells to wedding blues. The New York Times . Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/18/fashion/weddings/from-wedding-bells-to-wedding-blues.html . Accessed 24 May 2020.

The Knot. (2020). How to plan a wedding: The ultimate guide. The Knot . https://www.theknot.com/content/how-to-plan-a-wedding . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Title, S. (2017). Our best tips for perfect wedding hair. WeddingWire . Retrieved from https://www.weddingwire.com/wedding-ideas/our-best-tips-for-perfect-wedding-hair . Accessed 24 May 2020.

Ward, T. (2020). How to plan a cheap wedding (that doesn’t look cheap). Simply Eloped . Retrieved from https://simplyeloped.com/plan-cheap-wedding-doesnt-look-cheap/ . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Warren, J. (1995). State bans gender bias in service pricing. Los Angeles Times . Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-10-14-mn-56735-story.html . Accessed 22 May 2020.

Washington, E. (2006). The impact of banking and fringe banking regulation on the number of unbanked Americans. The Journal of Human Resources, 41 (1), 106–137.

Wedding Ceremony. (2018). How much is too much? WeddingWire . Retrieved from https://www.weddingwire.com/wedding-forums/how-much-is-too-much/d456c753ac02e2cc.html . Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

Weiss, M. (2020). How to plan a wedding: 42 tips for the DIY bride. Brides . Retrieved from https://www.brides.com/gallery/how-to-plan-your-own-wedding . Accessed 23 May 2020.

Weissman, R. (2004). Drug price gouging OK’d. Multinational Monitor, 25 (9), 6–7.

Wilborn, B. L. (1976). A review of the myth of the perfect mother. Counseling Psychologist, 6 (2), 42–45.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1981). How consumer evaluation processes differ between goods and services. In J. H. Donnelly & W. R. George (Eds.), Marketing of services (pp. 186–189). American Marketing Association.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Louisiana State University Shreveport, Shreveport, LA, 71115, USA

N. D. Albers, A. O. Wren & T. L. Knotts

Berry College, Mount Berry, USA

M. G. Chupp

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to T. L. Knotts .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Albers, N.D., Wren, A.O., Knotts, T.L. et al. Consumer Perceptions and Pricing Practices for Weddings. J Consum Policy 44 , 407–426 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-021-09488-y

Download citation

Received : 04 June 2020

Accepted : 17 March 2021

Published : 20 April 2021

Issue Date : September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-021-09488-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Discrimination

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Market Research Consumer Goods Market Research Consumer Goods & Retailing Market Research House & Home Market Research Wedding Market Research

Wedding Market Research Reports & Industry Analysis

Wedding industry research & market reports, refine your search, 2024 wedding still photography services global market size & growth report with updated recession risk impact.

Mar 04, 2024 | Published by: Kentley Insights | USD 295

... and share across 4 global regions (The Americas, Europe, Asia & Oceania, Africa & Middle East), 22 subregions, and 195 countries. Figures are from 2012 through 2023, with forecasts for 2024 and 2028. The historical ... Read More

2024 Wedding and Special Event Photography Services Global Market Size & Growth Report with Updated Recession Risk Impact

... market size, revenue, growth, and share across 4 global regions (The Americas, Europe, Asia & Oceania, Africa & Middle East), 22 subregions, and 195 countries. Figures are from 2012 through 2023, with forecasts for 2024 ... Read More

The 2025-2030 World Outlook for Bridal Wear

Mar 03, 2024 | Published by: Icon Group International, Inc. | USD 995

... industry earnings (P.I.E.), for the country in question (in millions of U.S. dollars), the percent share the country is of the region, and of the globe. These comparative benchmarks allow the reader to quickly gauge ... Read More

Bridal Wear

Mar 01, 2024 | Published by: Global Industry Analysts | USD 5,600

... growing at a CAGR of 4% over the period 2022-2030. Offline Bridal Wear, one of the segments analyzed in the report, is expected to record 4% CAGR and reach US$71.3 Billion by the end of ... Read More

Destination Wedding Global Market Report 2024

Feb 23, 2024 | Published by: The Business Research Company | USD 4,000

... By Venues: National; International5) By Booking Channel: Phone Booking; Online Booking; In Person BookingCovering: Sparkles & Bubbles Weddings; Tropical Wedding & Honeymoon; Vivaah Weddings; Revel Events Weddings; The Wedding Travel Company Destination Wedding Global Market ... Read More

Bridal Stores in the US - Industry Market Research Report

Feb 15, 2024 | Published by: IBISWorld | USD 1,095

... clashed with a strong macroeconomic climate. Although fewer couples tied the knot during the five-year period, growth in per capita disposable income and consumer spending encouraged more brides and grooms to splurge on high-value wedding ... Read More

Global Wedding Jewelry Market Professional Survey by Types, Applications, and Players, with Regional Growth Rate Analysis and Development Situation, from 2023 to 2028

Feb 14, 2024 | Published by: Maia Research | USD 3,160

... growth of the Wedding Jewelry industry between the year 2018 to 2028, and breaks down according to the product type, downstream application, and consumption area of Wedding Jewelry. The report also introduces players in the ... Read More

US Wedding Management Market - Focused Insights 2024-2029

Feb 06, 2024 | Published by: Arizton Advisory and Intelligence | USD 1,800

... management is included in the report. This report provides a comprehensive and current market scenario of US wedding management, including the US wedding management market size, anticipated market forecast, relevant market segmentations, and industry trends. ... Read More

2024 Rental of Space for Weddings, Banquets, Parties, and Similar Short-Term Social Uses Global Market Size & Growth Report with Updated Recession Risk Impact

Feb 06, 2024 | Published by: Kentley Insights | USD 295

... and Similar Short-Term Social Uses Global Market Size & Growth Report covers market size, revenue, growth, and share across 4 global regions (The Americas, Europe, Asia & Oceania, Africa & Middle East), 22 subregions, and ... Read More

Photo Market By Type (Stock Photography, Theme Park and Cruise Line, Schools and Colleges, Sports, Conferences, Events and Weddings): Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2023-2032

Feb 01, 2024 | Published by: Allied Market Research | USD 5,730

... million in 2022, and is projected to reach $9163.3 million by 2032, registering a CAGR of 6.7% from 2023 to 2032. The photo market is engaged in the buying and selling of digital images and ... Read More

Wedding Wear Market by Category (Children Wear, Men Wear, Women Wear), Product (Accessories, Footwear, Gown), Distribution Channel - Global Forecast 2024-2030

Jan 15, 2024 | Published by: 360iResearch | USD 4,749

... and expected to reach USD 12.53 billion in 2024, at a CAGR 5.30% to reach USD 17.10 billion by 2030. Global Wedding Wear MarketWedding wear includes all garments that are worn by the couples, during ... Read More

Wedding Planners in the US - Industry Market Research Report

Jan 04, 2024 | Published by: IBISWorld | USD 1,020

... plan their weddings themselves rather than hire industry operators. According to 2021 data from the Wedding Planning Institute, 27.0% of couples are using wedding planners. This contraction in demand for industry services mainly stems from ... Read More

Bridalwear Manufacturers (UK) - Industry Report

Jan 01, 2024 | Published by: Plimsoll Publishing Ltd. | USD 400

... CARINA BAVERSTOCK COUTURE LTD, ELIZABETH DICKENS LTD and IMPRESSION BRIDAL UK LTD. This report covers activities such as wedding, bridesmaid, bridal, bride, white and includes a wealth of information on the financial trends over the ... Read More

Bridalwear Retailers (UK) - Industry Report

... ALWAYS & FOREVER LTD, BELLA B LTD and BRIDAL BOX LTD. This report covers activities such as bridal, wedding dresses, wedding, wedding dress, bridesmaids and includes a wealth of information on the financial trends over ... Read More

Bridal Wear Market Trends in China

Dec 31, 2023 | Published by: Asia Market Information & Development Company | USD 3,000

... manufacturing capabilities and rising consumer consumptions in China have transformed China’s society and economy. China is one of the world’s major producers for industrial and consumer products. Far outpacing other economies in the world, China ... Read More

Wedding Services in China - Industry Market Research Report

Nov 30, 2023 | Published by: IBISWorld | USD 1,095

... 2023, to total $26.8 billion in 2023. This trend includes expected revenue growth of 2.9% in the current year. In the first half of 2020, many small and medium-sized enterprises in the industry closed due ... Read More

Wedding Planning Apps Market Size, Share, Trends, Growth, Outlook, and Insights Report, 2023- Industry Forecasts by Type, Application, Segments, Countries, and Companies, 2021- 2030

Nov 23, 2023 | Published by: VPA Research | USD 3,400

... growth industry. In 2023, the market is poised to register positive year-on-year growth over 2022. Further, the Wedding Planning Apps market size maintains a super-linear growth trajectory, registering continuous expansion from 2023 to 2030. As ... Read More

Global Wedding Planning Market Professional Survey by Types, Applications, and Players, with Regional Growth Rate Analysis and Development Situation, from 2023 to 2028

Nov 14, 2023 | Published by: Maia Research | USD 3,160

... growth of the Wedding Planning industry between the year 2018 to 2028, and breaks down according to the product type, downstream application, and consumption area of Wedding Planning. The report also introduces players in the ... Read More

Asia-Pacific Underwater Hotels Market Assessment, By Location [Coastal Areas, Open Oceans], By Type of Accommodation [Underwater Suites, Underwater Villas, Underwater Pods/Capsules], By Design [Partially Submerged, Fully Submerged], By Target Audience [Luxury Travelers, Adventure Seekers], By Package [Corporate Retreat, Wedding & Honeymoon Packages, All-inclusive Stays, Others], By Region, Opportunities and Forecast, 2016-2030F

Nov 03, 2023 | Published by: Market Xcel | USD 4,500

... By Package [Corporate Retreat, Wedding & Honeymoon Packages, All-inclusive Stays, Others], By Region, Opportunities and Forecast, 2016-2030F Asia-Pacific underwater hotels market is anticipated to grow at a CAGR of 14.2% between 2023 and 2030. The ... Read More

2023 Rental of Space for Weddings, Banquets, Parties, and Similar Short-Term Social Uses Global Market Size & Growth Report with COVID-19 & Recession Risk Impact

Oct 15, 2023 | Published by: Kentley Insights | USD 295

... Parties, and Similar Short-Term Social Uses Global Market Size & Growth Report covers market size, revenue, growth, and share across 4 global regions (The Americas, Europe, Asia & Oceania, Africa & Middle East), 22 subregions, ... Read More

2023 Wedding and Special Event Photography Services Global Market Size & Growth Report with COVID-19 & Recession Risk Impact

... covers market size, revenue, growth, and share across 4 global regions (The Americas, Europe, Asia & Oceania, Africa & Middle East), 22 subregions, and 216 countries. Figures are from 2014 through 2022, with forecasts for ... Read More

2023 Wedding Still Photography Services Global Market Size & Growth Report with COVID-19 & Recession Risk Impact

... growth, and share across 4 global regions (The Americas, Europe, Asia & Oceania, Africa & Middle East), 22 subregions, and 216 countries. Figures are from 2014 through 2022, with forecasts for 2023 and 2027. The ... Read More

Lingerie, Bridal & Swimwear Stores - 2023 U.S. Market Research Report with Updated Recession Risk & COVID-19 Forecasts

Oct 12, 2023 | Published by: Kentley Insights | USD 295

... most comprehensive and in-depth assessments of the retail sector in the United States with over 100 data sets covering 2014-2027. This Kentley Insights report includes historical and forecasted market size, ecommerce, product lines, inventory turns, ... Read More

Bridal Stores in Australia - Industry Market Research Report

Oct 02, 2023 | Published by: IBISWorld | USD 770

... increases in the number of marriages and in consumer sentiment benefitted industry performance. Additionally, the legalisation of same-sex marriages in December 2017 expanded the industry's addressable market for bridal stores. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has ... Read More

Underwater Hotels Market Assessment, By Location [Coastal Areas, Open Oceans], By Type of Accommodation [Underwater Suites, Underwater Villas, Underwater Pods/Capsules], By Design [Partially Submerged, Fully Submerged], By Target Audience [Luxury Travellers, Adventure Seekers], By Package [Corporate Retreat, Wedding and Honeymoon Packages, All-inclusive Stays, Others], By Region, Opportunities, and Forecast, 2016-2030F

Sep 12, 2023 | Published by: Market Xcel | USD 4,500

... Package [Corporate Retreat, Wedding and Honeymoon Packages, All-inclusive Stays, Others], By Region, Opportunities, and Forecast, 2016-2030F The underwater hotels market has emerged as an innovative and captivating niche within the broader hospitality industry. These submerged ... Read More

< prev 1 2 3 next >

Filter your search

- Global (51)

- Middle East (1)

- North America (10)

- Oceania (2)

Research Assistance

Join Alert Me Now!

Start new browse.

- Consumer Goods

- Food & Beverage

- Heavy Industry

- Life Sciences

- Marketing & Market Research

- Public Sector

- Service Industries

- Technology & Media

- Company Reports

- Reports by Country

- View all Market Areas

- View all Publishers

2023 Global Wedding Report