An Introduction to the Lyric Essay

Rebecca Hussey

Rebecca holds a PhD in English and is a professor at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She teaches courses in composition, literature, and the arts. When she’s not reading or grading papers, she’s hanging out with her husband and son and/or riding her bike and/or buying books. She can't get enough of reading and writing about books, so she writes the bookish newsletter "Reading Indie," focusing on small press books and translations. Newsletter: Reading Indie Twitter: @ofbooksandbikes

View All posts by Rebecca Hussey

Essays come in a bewildering variety of shapes and forms: they can be the five paragraph essays you wrote in school — maybe for or against gun control or on symbolism in The Great Gatsby . Essays can be personal narratives or argumentative pieces that appear on blogs or as newspaper editorials. They can be funny takes on modern life or works of literary criticism. They can even be book-length instead of short. Essays can be so many things!

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “lyric essay” and are wondering what that means. I’m here to help.

What is the Lyric Essay?

A quick definition of the term “lyric essay” is that it’s a hybrid genre that combines essay and poetry. Lyric essays are prose, but written in a manner that might remind you of reading a poem.

Before we go any further, let me step back with some more definitions. If you want to know the difference between poetry and prose, it’s simply that in poetry the line breaks matter, and in prose they don’t. That’s it! So the lyric essay is prose, meaning where the line breaks fall doesn’t matter, but it has other similarities to what you find in poems.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Lyric essays have what we call “poetic” prose. This kind of prose draws attention to its own use of language. Lyric essays set out to create certain effects with words, often, although not necessarily, aiming to create beauty. They are often condensed in the way poetry is, communicating depth and complexity in few words. Chances are, you will take your time reading them, to fully absorb what they are trying to say. They may be more suggestive than argumentative and communicate multiple meanings, maybe even contradictory ones.

Lyric essays often have lots of white space on their pages, as poems do. Sometimes they use the space of the page in creative ways, arranging chunks of text differently than regular paragraphs, or using only part of the page, for example. They sometimes include photos, drawings, documents, or other images to add to (or have some other relationship to) the meaning of the words.

Lyric essays can be about any subject. Often, they are memoiristic, but they don’t have to be. They can be philosophical or about nature or history or culture, or any combination of these things. What distinguishes them from other essays, which can also be about any subject, is their heightened attention to language. Also, they tend to deemphasize argument and carefully-researched explanations of the kind you find in expository essays . Lyric essays can argue and use research, but they are more likely to explore and suggest than explain and defend.

Now, you may be familiar with the term “ prose poem .” Even if you’re not, the term “prose poem” might sound exactly like what I’m describing here: a mix of poetry and prose. Prose poems are poetic pieces of writing without line breaks. So what is the difference between the lyric essay and the prose poem?

Honestly, I’m not sure. You could call some pieces of writing either term and both would be accurate. My sense, though, is that if you put prose and poetry on a continuum, with prose on one end and poetry on the other, and with prose poetry and the lyric essay somewhere in the middle, the prose poem would be closer to the poetry side and the lyric essay closer to the prose side.

Some pieces of writing just defy categorization, however. In the end, I think it’s best to call a work what the author wants it to be called, if it’s possible to determine what that is. If not, take your best guess.

Four Examples of the Lyric Essay

Below are some examples of my favorite lyric essays. The best way to learn about a genre is to read in it, after all, so consider giving one of these books a try!

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen counts as a lyric essay, but I want to highlight her lesser-known 2004 work. In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely , Rankine explores isolation, depression, death, and violence from the perspective of post-9/11 America. It combines words and images, particularly television images, to ponder our relationship to media and culture. Rankine writes in short sections, surrounded by lots of white space, that are personal, meditative, beautiful, and achingly sad.

Calamities by Renee Gladman

Calamities is a collection of lyric essays exploring language, imagination, and the writing life. All of the pieces, up until the last 14, open with “I began the day…” and then describe what she is thinking and experiencing as a writer, teacher, thinker, and person in the world. Many of the essays are straightforward, while some become dreamlike and poetic. The last 14 essays are the “calamities” of the title. Together, the essays capture the artistic mind at work, processing experience and slowly turning it into writing.

The Self Unstable by Elisa Gabbert

The Self Unstable is a collection of short essays — or are they prose poems? — each about the length of a paragraph, one per page. Gabbert’s sentences read like aphorisms. They are short and declarative, and part of the fun of the book is thinking about how the ideas fit together. The essays are divided into sections with titles such as “The Self is Unstable: Humans & Other Animals” and “Enjoyment of Adversity: Love & Sex.” The book is sharp, surprising, and delightful.

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Bluets is made up of short essayistic, poetic paragraphs, organized in a numbered list. Maggie Nelson’s subjects are many and include the color blue, in which she finds so much interest and meaning it will take your breath away. It’s also about suffering: she writes about a friend who became a quadriplegic after an accident, and she tells about her heartbreak after a difficult break-up. Bluets is meditative and philosophical, vulnerable and personal. It’s gorgeous, a book lovers of The Argonauts shouldn’t miss.

It’s probably no surprise that all of these books are published by small presses. Lyric essays are weird and genre-defying enough that the big publishers generally avoid them. This is just one more reason, among many, to read small presses!

If you’re looking for more essay recommendations, check out our list of 100 must-read essay collections and these 25 great essays you can read online for free .

You Might Also Like

A Guide to Lyric Essay Writing: 4 Evocative Essays and Prompts to Learn From

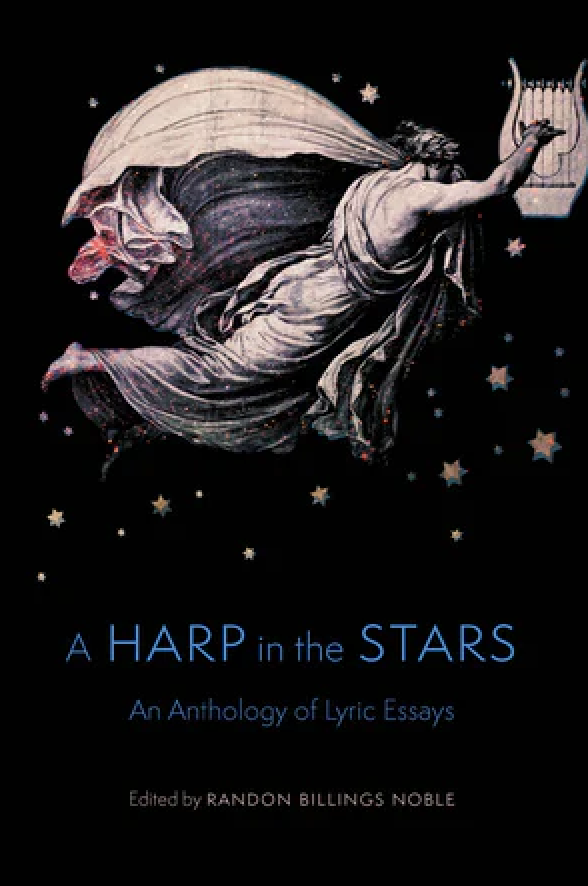

Poets can learn a lot from blurring genres. Whether getting inspiration from fiction proves effective in building characters or song-writing provides a musical tone, poetry intersects with a broader literary landscape. This shines through especially in lyric essays, a form that has inspired articles from the Poetry Foundation and Purdue Writing Lab , as well as become the concept for a 2015 anthology titled We Might as Well Call it the Lyric Essay.

Put simply, the lyric essay is a hybrid, creative nonfiction form that combines the rich figurative language of poetry with the longer-form analysis and narrative of essay or memoir. Oftentimes, it emerges as a way to explore a big-picture idea with both imagery and rigor. These four examples provide an introduction to the writing style, as well as spotlight tips for creating your own.

1. Draft a “braided essay,” like Michelle Zauner in this excerpt from Crying in H Mart .

Before Crying in H Mart became a bestselling memoir, Michelle Zauner—a writer and frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast—published an essay of the same name in The New Yorker . It opens with the fascinating and emotional sentence, “Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.” This first line not only immediately propels the reader into Zauner’s grief, but it also reveals an example of the popular “braided essay” technique, which weaves together two distinct but somehow related experiences.

Throughout the work, Zauner establishes a parallel between her and her mother’s relationship and traditional Korean food. “You’ll likely find me crying by the banchan refrigerators, remembering the taste of my mom’s soy-sauce eggs and cold radish soup,” Zauner writes, illuminating the deeply personal and mystifying experience of grieving through direct, sensory imagery.

2. Experiment with nonfiction forms , like Hadara Bar-Nadav in “ Selections from Babyland . ”

Lyric essays blend poetic qualities and nonfiction qualities. Hadara Bar-Nadav illustrates this experimental nature in Selections from Babyland , a multi-part lyric essay that delves into experiences with infertility. Though Bar-Nadav’s writing throughout this piece showcases rhythmic anaphora—a definite poetic skill—it also plays with nonfiction forms not typically seen in poetry, including bullet points and a multiple-choice list.

For example, when recounting unsolicited advice from others, Bar-Nadav presents their dialogue in the following way:

I heard about this great _____________.

a. acupuncturist

b. chiropractor

d. shamanic healer

e. orthodontist ( can straighter teeth really make me pregnant ?)

This unexpected visual approach feels reminiscent of an article or quiz—both popular nonfiction forms—and adds dimension and white space to the lyric essay.

3. Travel through time , like Nina Boutsikaris in “ Some Sort of Union .”

Nina Boutsikaris is the author of I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych , and her work has also appeared in an anthology of the best flash nonfiction. Her essay “Some Sort of Union,” published in Hippocampus Magazine , was a finalist in the magazine’s Best Creative Nonfiction contest.

Since lyric essays are typically longer and more free verse than poems, they can be a way to address a larger idea or broader time period. Boutsikaris does this in “Some Sort of Union,” where the speaker drifts from an interaction with a romantic interest to her childhood.

“They were neighbors, the girl and the air force paramedic. She could have seen his front door from her high-rise window if her window faced west rather than east,” Boutsikaris describes. “When she first met him two weeks ago, she’d been wearing all white, buying a wedge of cheap brie at the corner market.”

In the very next paragraph, Boutskiras shifts this perspective and timeline, writing, “The girl’s mother had been angry with her when she was a child. She had needed something from the girl that the girl did not know how to give. Not the way her mother hoped she would.”

As this example reveals, examining different perspectives and timelines within a lyric essay can flesh out a broader understanding of who a character is.

4. Bring in research, history, and data, like Roxane Gay in “ What Fullness Is .”

Like any other form of writing, lyric essays benefit from in-depth research. And while journalistic or scientific details can sometimes throw off the concise ecosystem and syntax of a poem, the lyric essay has room for this sprawling information.

In “What Fullness Is,” award-winning writer Roxane Gay contextualizes her own ideas and experiences with weight loss surgery through the history and culture surrounding the procedure.

“The first weight-loss surgery was performed during the 10th century, on D. Sancho, the king of León, Spain,” Gay details. “He was so fat that he lost his throne, so he was taken to Córdoba, where a doctor sewed his lips shut. Only able to drink through a straw, the former king lost enough weight after a time to return home and reclaim his kingdom.”

“The notion that thinness—and the attempt to force the fat body toward a state of culturally mandated discipline—begets great rewards is centuries old.”

Researching and knowing this history empowers Gay to make a strong central point in her essay.

Bonus prompt: Choose one of the techniques above to emulate in your own take on the lyric essay. Happy writing!

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

6 Ways to Support AAPI Poets During AAPI Heritage Month

5 Ways to Support Your Local Bookstores on Indie Bookstore Day

4 Poetry Prompts to Help You Celebrate Earth Day

What is creative nonfiction? Despite its slightly enigmatic name, no literary genre has grown quite as quickly as creative nonfiction in recent decades. Literary nonfiction is now well-established as a powerful means of storytelling, and bookstores now reserve large amounts of space for nonfiction, when it often used to occupy a single bookshelf.

Like any literary genre, creative nonfiction has a long history; also like other genres, defining contemporary CNF for the modern writer can be nuanced. If you’re interested in writing true-to-life stories but you’re not sure where to begin, let’s start by dissecting the creative nonfiction genre and what it means to write a modern literary essay.

What Creative Nonfiction Is

Creative nonfiction employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story.

How do we define creative nonfiction? What makes it “creative,” as opposed to just “factual writing”? These are great questions to ask when entering the genre, and they require answers which could become literary essays themselves.

In short, creative nonfiction (CNF) is a form of storytelling that employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story. Creative nonfiction writers don’t just share pithy anecdotes, they use craft and technique to situate the reader into their own personal lives. Fictional elements, such as character development and narrative arcs, are employed to create a cohesive story, but so are poetic elements like conceit and juxtaposition.

The CNF genre is wildly experimental, and contemporary nonfiction writers are pushing the bounds of literature by finding new ways to tell their stories. While a CNF writer might retell a personal narrative, they might also focus their gaze on history, politics, or they might use creative writing elements to write an expository essay. There are very few limits to what creative nonfiction can be, which is what makes defining the genre so difficult—but writing it so exciting.

Different Forms of Creative Nonfiction

From the autobiographies of Mark Twain and Benvenuto Cellini, to the more experimental styles of modern writers like Karl Ove Knausgård, creative nonfiction has a long history and takes a wide variety of forms. Common iterations of the creative nonfiction genre include the following:

Also known as biography or autobiography, the memoir form is probably the most recognizable form of creative nonfiction. Memoirs are collections of memories, either surrounding a single narrative thread or multiple interrelated ideas. The memoir is usually published as a book or extended piece of fiction, and many memoirs take years to write and perfect. Memoirs often take on a similar writing style as the personal essay does, though it must be personable and interesting enough to encourage the reader through the entire book.

Personal Essay

Personal essays are stories about personal experiences told using literary techniques.

When someone hears the word “essay,” they instinctively think about those five paragraph book essays everyone wrote in high school. In creative nonfiction, the personal essay is much more vibrant and dynamic. Personal essays are stories about personal experiences, and while some personal essays can be standalone stories about a single event, many essays braid true stories with extended metaphors and other narratives.

Personal essays are often intimate, emotionally charged spaces. Consider the opening two paragraphs from Beth Ann Fennelly’s personal essay “ I Survived the Blizzard of ’79. ”

We didn’t question. Or complain. It wouldn’t have occurred to us, and it wouldn’t have helped. I was eight. Julie was ten.

We didn’t know yet that this blizzard would earn itself a moniker that would be silk-screened on T-shirts. We would own such a shirt, which extended its tenure in our house as a rag for polishing silver.

The word “essay” comes from the French “essayer,” which means “to try” or “attempt.” The personal essay is more than just an autobiographical narrative—it’s an attempt to tell your own history with literary techniques.

Lyric Essay

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, but is much more experimental in form.

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, with one key distinction: lyric essays are much more experimental in form. Poetry and creative nonfiction merge in the lyric essay, challenging the conventional prose format of paragraphs and linear sentences.

The lyric essay stands out for its unique writing style and sentence structure. Consider these lines from “ Life Code ” by J. A. Knight:

The dream goes like this: blue room of water. God light from above. Child’s fist, foot, curve, face, the arc of an eye, the symmetry of circles… and then an opening of this body—which surprised her—a movement so clean and assured and then the push towards the light like a frog or a fish.

What we get is language driven by emotion, choosing an internal logic rather than a universally accepted one.

Lyric essays are amazing spaces to break barriers in language. For example, the lyricist might write a few paragraphs about their story, then examine a key emotion in the form of a villanelle or a ghazal . They might decide to write their entire essay in a string of couplets or a series of sonnets, then interrupt those stanzas with moments of insight or analysis. In the lyric essay, language dictates form. The successful lyricist lets the words arrange themselves in whatever format best tells the story, allowing for experimental new forms of storytelling.

Literary Journalism

Much more ambiguously defined is the idea of literary journalism. The idea is simple: report on real life events using literary conventions and styles. But how do you do this effectively, in a way that the audience pays attention and takes the story seriously?

You can best find examples of literary journalism in more “prestigious” news journals, such as The New Yorker , The Atlantic , Salon , and occasionally The New York Times . Think pieces about real world events, as well as expository journalism, might use braiding and extended metaphors to make readers feel more connected to the story. Other forms of nonfiction, such as the academic essay or more technical writing, might also fall under literary journalism, provided those pieces still use the elements of creative nonfiction.

Consider this recently published article from The Atlantic : The Uncanny Tale of Shimmel Zohar by Lawrence Weschler. It employs a style that’s breezy yet personable—including its opening line.

So I first heard about Shimmel Zohar from Gravity Goldberg—yeah, I know, but she insists it’s her real name (explaining that her father was a physicist)—who is the director of public programs and visitor experience at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, in San Francisco.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Common Elements and Techniques

What separates a general news update from a well-written piece of literary journalism? What’s the difference between essay writing in high school and the personal essay? When nonfiction writers put out creative work, they are most successful when they utilize the following elements.

Just like fiction, nonfiction relies on effective narration. Telling the story with an effective plot, writing from a certain point of view, and using the narrative to flesh out the story’s big idea are all key craft elements. How you structure your story can have a huge impact on how the reader perceives the work, as well as the insights you draw from the story itself.

Consider the first lines of the story “ To the Miami University Payroll Lady ” by Frenci Nguyen:

You might not remember me, but I’m the dark-haired, Texas-born, Asian-American graduate student who visited the Payroll Office the other day to complete direct deposit and tax forms.

Because the story is written in second person, with the reader experiencing the story as the payroll lady, the story’s narration feels much more personal and important, forcing the reader to evaluate their own personal biases and beliefs.

Observation

Telling the story involves more than just simple plot elements, it also involves situating the reader in the key details. Setting the scene requires attention to all five senses, and interpersonal dialogue is much more effective when the narrator observes changes in vocal pitch, certain facial expressions, and movements in body language. Essentially, let the reader experience the tiny details – we access each other best through minutiae.

The story “ In Transit ” by Erica Plouffe Lazure is a perfect example of storytelling through observation. Every detail of this flash piece is carefully noted to tell a story without direct action, using observations about group behavior to find hope in a crisis. We get observation when the narrator notes the following:

Here at the St. Thomas airport in mid-March, we feel the urgency of the transition, the awareness of how we position our bodies, where we place our luggage, how we consider for the first time the numbers of people whose belongings are placed on the same steel table, the same conveyor belt, the same glowing radioactive scan, whose IDs are touched by the same gloved hand[.]

What’s especially powerful about this story is that it is written in a single sentence, allowing the reader to be just as overwhelmed by observation and context as the narrator is.

We’ve used this word a lot, but what is braiding? Braiding is a technique most often used in creative nonfiction where the writer intertwines multiple narratives, or “threads.” Not all essays use braiding, but the longer a story is, the more it benefits the writer to intertwine their story with an extended metaphor or another idea to draw insight from.

“ The Crush ” by Zsofia McMullin demonstrates braiding wonderfully. Some paragraphs are written in first person, while others are written in second person.

The following example from “The Crush” demonstrates braiding:

Your hair is still wet when you slip into the booth across from me and throw your wallet and glasses and phone on the table, and I marvel at how everything about you is streamlined, compact, organized. I am always overflowing — flesh and wants and a purse stuffed with snacks and toy soldiers and tissues.

The author threads these narratives together by having both people interact in a diner, yet the reader still perceives a distance between the two threads because of the separation of “I” and “you” pronouns. When these threads meet, briefly, we know they will never meet again.

Speaking of insight, creative nonfiction writers must draw novel conclusions from the stories they write. When the narrator pauses in the story to delve into their emotions, explain complex ideas, or draw strength and meaning from tough situations, they’re finding insight in the essay.

Often, creative writers experience insight as they write it, drawing conclusions they hadn’t yet considered as they tell their story, which makes creative nonfiction much more genuine and raw.

The story “ Me Llamo Theresa ” by Theresa Okokun does a fantastic job of finding insight. The story is about the history of our own names and the generations that stand before them, and as the writer explores her disconnect with her own name, she recognizes a similar disconnect in her mother, as well as the need to connect with her name because of her father.

The narrator offers insight when she remarks:

I began to experience a particular type of identity crisis that so many immigrants and children of immigrants go through — where we are called one name at school or at work, but another name at home, and in our hearts.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: the 5 R’s

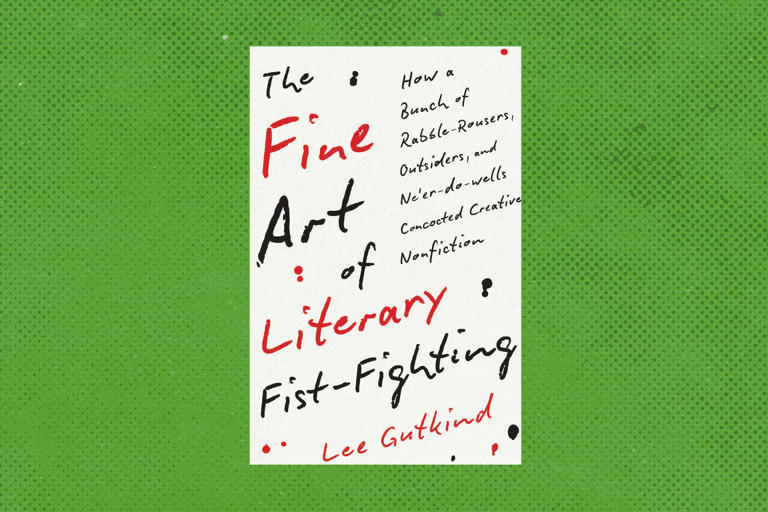

CNF pioneer Lee Gutkind developed a very system called the “5 R’s” of creative nonfiction writing. Together, the 5 R’s form a general framework for any creative writing project. They are:

- Write about r eal life: Creative nonfiction tackles real people, events, and places—things that actually happened or are happening.

- Conduct extensive r esearch: Learn as much as you can about your subject matter, to deepen and enrich your ability to relay the subject matter. (Are you writing about your tenth birthday? What were the newspaper headlines that day?)

- (W) r ite a narrative: Use storytelling elements originally from fiction, such as Freytag’s Pyramid , to structure your CNF piece’s narrative as a story with literary impact rather than just a recounting.

- Include personal r eflection: Share your unique voice and perspective on the narrative you are retelling.

- Learn by r eading: The best way to learn to write creative nonfiction well is to read it being written well. Read as much CNF as you can, and observe closely how the author’s choices impact you as a reader.

You can read more about the 5 R’s in this helpful summary article .

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Give it a Try!

Whatever form you choose, whatever story you tell, and whatever techniques you write with, the more important aspect of creative nonfiction is this: be honest. That may seem redundant, but often, writers mistakenly create narratives that aren’t true, or they use details and symbols that didn’t exist in the story. Trust us – real life is best read when it’s honest, and readers can tell when details in the story feel fabricated or inflated. Write with honesty, and the right words will follow!

Ready to start writing your creative nonfiction piece? If you need extra guidance or want to write alongside our community, take a look at the upcoming nonfiction classes at Writers.com. Now, go and write the next bestselling memoir!

Sean Glatch

Thank you so much for including these samples from Hippocampus Magazine essays/contributors; it was so wonderful to see these pieces reflected on from the craft perspective! – Donna from Hippocampus

Absolutely, Donna! I’m a longtime fan of Hippocampus and am always astounded by the writing you publish. We’re always happy to showcase stunning work 🙂

[…] Source: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/a-complete-guide-to-writing-creative-nonfiction#5-creative-nonfiction-writing-promptshttps://writers.com/what-is-creative-nonfiction […]

So impressive

Thank you. I’ve been researching a number of figures from the 1800’s and have come across a large number of ‘biographies’ of figures. These include quoted conversations which I knew to be figments of the author and yet some works are lauded as ‘histories’.

excellent guidelines inspiring me to write CNF thank you

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

15 Creative Nonfiction and the Lyric Essay: The American Essay in the Twenty-First Century

- Published: September 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter is devoted to writing which falls under a recent, nearly paradoxical coinage: ‘creative nonfiction’, a phrase which raises the fundamental theoretical questions asked by Lukács and Adorno about whether the essay is better seen as art or knowledge. Stuckey-French examines both the rise of this category in creative writing programmes in universities in the United States, and the arguments of the influential theorist and anthologist of the essay John d’Agata, who rejects ‘creative nonfiction’ in favour of the ‘lyric essay’. Stuckey-French then shows how the contemporary essayists Jo Ann Beard, Eula Biss, and Claudia Rankine are both preoccupied by the boundary between fiction and reality, and often transgress it without minimizing its ethical and political significance, in respect of childhood memory, violence, or race.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Craft Essays

- Teaching Resources

Structure: Lifeblood of the Lyric Essay

Writing mostly poetry for the last two years, I had pretty much given up on prose. Until I met the lyric essay. It was as if I found myself a new lover. I was on a cloud-nine high: I didn’t have to write a tightly knitted argument required of a critical essay. I could loosely stitch fragments—even seemingly unrelated ones. I could leave gaps. Lean on poetic devices such as lyricism and metaphor. Let juxtaposition do the talking. I did not need to know the answer, nor did I need to offer one. It was up to the reader to intuit meaning. Whew!

Okay, so it’s not as easy as that. I can’t just stick bits together. Not if I want to write a decent —fabulous! —lyric essay. Structure is work. A work of craft, like shaping a poem, requiring space and patience. In her essay “The Interplay of Form and Content in Creative Nonfiction,” Eileen Pollack writes “…finding the perfect form for the material a writer is trying to shape is the most important factor in whether or not that material will ever advance from a one- or two-page beginning to a coherent first draft to a polished essay [my emphasis].”

But why such weight on structure?

The lyric essay, say Deborah Tall and John D’Agata , is useful for “circling the core” of ineffable subjects. And in her Fourth Genre essay , Judith Kitchen states that its moment is the present, as it “goes about discovering what its about is [Kitchen’s emphasis].” As such, traditional structures—e.g. narrative logic and fully fleshed arguments that help the writer organize what he or she already knows—don’t befit the lyric essay (as per Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in Tell It Slant ).

This makes sense. Because when I tried to write prose I would flail in too many words, unable to say what I felt. Hence, the poetry. But now I had discovered a prose genre where the writer leans on form— consciously constructing it or borrowing a “shell” like the hermit crab [1] —to eloquently hold the inexpressible aboutness , to let meaning dance in the spaces between its juxtaposed parts.

For fun—and to appreciate the significance of structure—I juxtaposed two essays from Ellena Savage’s debut collection Blueberries : the titular essay “Blueberries” and “The Museum of Rape,” essays with very different forms; in fact, the whole book is a goodie bag of experimental forms.

I saw that while “Blueberries’” structural unit looked like the paragraph, its appearance is deceptive: the usual paragraph-by-paragraph logic is non-existent; instead, each paragraph acts as an individual poetic musing, making it more like a stanza, which literally means “room” in Italian. Some rooms are big—a single block of unindented text that can be longer than a page—and each room is separated by a single line break. As such, “Blueberries” could have easily become an amorphous piece of writing that leaves the reader thinking What’s the point of this? or scares them off with the lack of white space, but Savage uses metaphor and the lyricism of repetition to build a sturdy, stylish house.

The phrase “I was in America at a very expensive writer’s workshop”—or variations of it—appears in almost every room. Other words and phrases such as blueberries, black silk robe, gender-neutral toilets, reedy and tepid and well-read [male] faculty member, also often fleck the essay. This syntactical play and repetition, delivered in long, conversational sentences as if talking passionately to a friend about something weighty (which she is), are used as metaphors—tangible stand-ins—allowing Savage to have a broader conversation about complex abstract themes, in this case the intersection of privilege, gender, and making a living as a woman and a writer. Crucially, the repetition also makes associative links between the rooms, giving the reader agency to intuit meaning. As such, these structural devices create layered connotations (like a poem), making structure integral to the completeness—and coherence—of “Blueberries.”

In “The Museum of Rape,” Savage sections the content by numbered indexes – e.g. 4.0, 4.1, 4.2, like museum labels for pieces of artwork; hence, performing the essay’s title on one level. Savage uses these indexes to direct the reader to different parts of the essay, associating (in some instances ostensibly unrelated) fragments together, whereas in “Blueberries” Savage uses repetition as the associative device. This structure invites the reader to navigate the essay in multiple interwoven ways, intentionally making meaning a slippery thing that can “fall into an abyss”—a phrase that Savage often directs the reader to. In this way, the structure—labyrinthine and tangential—mimics the content, which is much more allusive— elusive even —than “Blueberries,” given its themes of trauma, memory’s unreliability, and, as beautifully summarized by a review , “the lacunae of loss (of loved ones, faith, and even the mind itself).” Savage captures this essence in index 8.0: What I’m saying is that I understand the total collapse of structured memory.

I asked myself, what it means to anticipate the loss of one’s rational function (7.0, 7.1, 7.2)…I comprehend tripping into the lacuna with my hands tied behind my back.

The museum-label structure also offers plenty of lacunae: There is almost a double line break in between each of the indexed fragments, because the index number is left-adjusted and given an entire line. Also, the fragments are, on average, shorter than the rooms in “Blueberries,” with many paragraphs indicated by an indent or a line break rather than a block of unindented text. There’s a poem in there, too, peppered with cesurae. These structural devices further signify the content, whereas “Blueberries” is purposefully dense to indicate a pressing sense of importance. Which is to say, the form used for “Blueberries” could not convey the aboutness of “The Museum of Rape” and vice versa—proof that form is the lifeblood of the lyric essay.

Now all there’s left to do is construct one. So, let’s play.

Choose a nonfiction piece you’ve already written or are working on, preferably one with a subject matter that’s tricky to articulate. Now reconstruct it by building or borrowing a form that’ll illuminate (even perform) the aboutness of your piece. Here are some ideas:

- A series of letters, emails, tweets or diary entries (epistolatory)

- An instructional piece—e.g. “How to…,” a recipe, or a to-do list—using “you” as the point of view

- Stanzas/paragraphs (like “Blueberries”) that can stand alone, but when put together offer a bigger/layered meaning through repetition

- Versify, playing with lineation and cesura; you can also intermix a series of poems and prose fragments

- A “mock” scientific paper with title, author(s), aim, methods, results, conclusion, discussion, and a reference list, as a way to section the content

Above all, have fun experimenting. ____

Lesh Karan is a former pharmacist who writes. Read her in Australian Multilingual Writing Project, Australian Poetry Journal, Cordite Poetry Review, Not Very Quiet and Rabbit , among others. Her writing has previously been shortlisted for the New Philosopher Writers’ Award. Lesh is currently undertaking a Master of Creative Writing, Editing and Publishing at the University of Melbourne.

[1] The “Hermit Crab Essay” is a term coined by Miller and Paola to describe an essay that “appropriates existing forms as an outer covering” for its “tender” content. A classic example is Primo Levi’s memoir The Periodic Table , structured using the chemical elements in the periodic table.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

© 2024 Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction. All Rights Reserved!

Designed by WPSHOWER

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Creative Nonfiction in Writing Courses

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Introduction

Creative nonfiction is a broad term and encompasses many different forms of writing. This resource focuses on the three basic forms of creative nonfiction: the personal essay, the memoir essay, and the literary journalism essay. A short section on the lyric essay is also discussed.

The Personal Essay

The personal essay is commonly taught in first-year composition courses because students find it relatively easy to pick a topic that interests them, and to follow their associative train of thoughts, with the freedom to digress and circle back.

The point to having students write personal essays is to help them become better writers, since part of becoming a better writer is the ability to express personal experiences, thoughts and opinions. Since academic writing may not allow for personal experiences and opinions, writing the personal essay is a good way to allow students further practice in writing.

The goal of the personal essay is to convey personal experiences in a convincing way to the reader, and in this way is related to rhetoric and composition, which is also persuasive. A good way to explain a personal essay assignment to a more goal-oriented student is simply to ask them to try to persuade the reader about the significance of a particular event.

Most high-school and first-year college students have plenty of experiences to draw from, and they are convinced about the importance of certain events over others in their lives. Often, students find their strongest conviction in the process of writing, and the personal essay is a good way to get students to start exploring these possibilities in writing.

A personal essay assignment can work well as a prelude to a research paper, because personal essays will help students understand their own convictions better, and will help prepare them to choose research topics that interest them.

An Example and Discussion of a Personal Essay

The following excerpt from Wole Soyinka's (Nigerian Nobel Laureate) Why Do I Fast? is an example of a personal essay. What follows is a short discussion of Soyinka's essay.

Soyinka begins with a question that fascinates him. He doesn’t feel required to immediately answer the question in the second paragraph. Rather, he takes time to consider his own inclination to believe that there is a connection between fasting and sensuality.

Soyinka follows the flowing associative arc of his thoughts, and he goes on to write about sunsets, and quotes from a poem that he wrote in his cell. The essay ends, not on a restatement of his thesis, but on yet another question that arises:

This question remains unanswered. Soyinka is not interested in even attempting to answer it. The personal essay doesn’t necessarily seek to make sense out of life experiences; rather, personal essays tend to let go of that sense-making impulse to do something else, like nose around a bit in the wondering, uncertain space that lies between experience and the need to organize it in a logical manner.

However informal the personal essay may seem, it’s important to keep in mind that, as Dinty W. Moore says in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction , “the essay should always be motivated by the author’s genuine interest in wrestling with complex questions.”

Generating Ideas for Personal Essays

In The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction , Moore goes on to explain an effective way to help students generate ideas for personal essays:

“Think about ten things you care about deeply: the environment, children in poverty, Alzheimer’s research (because your grandfather is a victim), hip-hop music, Saturday afternoon football games. Make your own list of ten important subjects, and then narrow the larger subject down to specific subjects you might write about. The environment? How about that bird sanctuary out on Township Line Road that might be torn down to make room for a megastore?..."

"...What is it like to be the food service worker who puts mustard on two thousand hot dogs every Saturday afternoon? Don’t just wonder about it - talk to the mustard spreader, spend an afternoon hanging out behind the counter, spread some mustard yourself. Transform your list of ten things into a longer list of possible story ideas. Don’t worry for now about whether these ideas would take a great amount of research, or might require special permission or access. Just write down a master list of possible stories related to your ideas and passions. Keep the list. You may use it later.”

It is this flexibility of form in the personal essay that makes it easy for students who are majoring in engineering, nutrition, graphic design, finance, management, etc. to adapt, learn and practice. The essay can be a more worldly form of writing than poetry or fiction, so students from various backgrounds, majors, jobs and cultures can express interesting and powerful thoughts and feelings in them.

The essay is more worldly than poetry and fiction in another sense: it allows for more of the world and its languages, its arts and food, its sport and business, its travel and politics, its sciences and entertainment, to be present, valid and important.

- Bibliography

You are here

Lyric essay.

Back to Glossary

Lyric essay is a term that some writers of creative nonfiction use to describe a type of creative essay that blends a lyrical, poetic sensibility with intellectual engagement. Although it may include personal elements, it is not a memoir or personal essay, where the primary subject is the writer's own experience. Not all creative essayists have embraced the term, however, which makes it a problematic classification in this community.

Blackburn, Kathleen. “Interview with Lia Purpura.” The Journal 36.4 (Autumn 2012). Web. 2 November 2012.

Butler, Judith. "Grounding the Lyric Essay." Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonfiction 13.2 (Fall 2011).

D’Agata, John, and Deborah Tall. “The Lyric Essay.” Seneca Review . Web. 5 May 2012.

Dillon, Brian. “Energy and Rue.” Frieze 151 (November-December 2012). Web. 19 October 2012.

Lazar, David. “Queering the Essay.” Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction. Ed. Margot Singer and Nicole Walker. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013. Print.

Lopate, Phillip. “Curiouser and Curiouser: The Practice of Nonfiction Today.” The Iowa Review 36.1 (Spring 2006). Web. 29 October 2012.

Lopate, Phillip. “A Skeptical Take.” The Seneca Review 357.2 (Fall 2007). Geneva, NY: Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Print.

Klaus, Carl H. and Stuckey-French, Ned. Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2012. Print.

Nelson, Emma. " Review of Small Fires, a Book of Lyric Essays ." Brevity's Nonfiction Blog. 13 April 2012. Web. 10 December 2013.

Emma Nelson describes Julie Marie Wade's book Small Fires, a book of lyric essays, using the following language, which is a good example of how lyric essays are usually categorized: "Julie Marie Wade’s Small Fires tells a similar story of her own time capsules that, much like the essays themselves, preserve self and childhood memories. Small Fires , a book of lyric essays, seamlessly incorporates Kantian philosophy, 1980s popular culture, and poetic explorations of words and meanings. Wade’s word choices and descriptions are impeccable, leading her reader on a rhythmic walk through the landscape of life as she explores what we give up to become who we are. Her exquisite language is not limited to word choice, however, but expands to the ways she plays with ordinary words and ideas such as waffle: a breakfast food or a verb “to switch back and forth between possibilities,” she writes, and camouflage as a metaphor for hiding who we are. Wade plays with the ideas, sounds, and feelings of words in a way that only a true poet can, sounding like a woman who not only loves language, but one who knows language well."

In the years since the term “lyric essay” was coined, some creative nonfiction writers have embraced it as a term for the kind of writing they do, while others have rejected it. In 2007, the Seneca Review published a special issue on the lyric essay, in which writers were still at odds about it ten years after the coining of the term, and arguments have continued since then. Some argue that what Tall and D’Agata describe is just essay writing and does not need the descriptor “lyric”; for instance, essayist Lia Purpura states, “I don’t really use the term ‘lyrical essay.’ I really prefer just ‘essay’ to describe what it is I’m up to. The tradition is long and honorable and I don’t feel the need to nichify” (Blackburn). In the Seneca Review special issue, Phillip Lopate praises the idea of the lyric essay for its “replacement of the monaural, imperially ego-confident self” of the traditional personal essay, but questions the lyric essay's lack of argumentative force, or its “refusal to let thought accrue to some purpose” (31). Lopate writes that some lyric essays may be “trying to get a license for their vagueness, which will allow them to dither on prettily, or 'lyrically,' to the frustration of most readers” (32). In short, Lopate is concerned that the lyricism of these essays will not drive intellectual engagement (which he considers to be central to the essay) but will instead become an excuse not to engage fully with issues or arguments.

Others have reacted negatively against the idea of perceiving creative nonfiction as closely related to poetry because poems have been held traditionally to looser standards for factual accuracy than creative nonfiction. In a lyric essay, the “I” persona is cast more as the speaker of a poem, and in poetry, it is understood that this speaker is not always the writer him- or herself and that the speaker may communicate poetic truth instead of factual truth. Brian Dillon, in “Energy and Rue,” criticizes the lyric essay: “If D’Agata’s lyric essay were the best or only hope for the genre today, you’d have to conclude it would be better off defunct” because nonfiction should not depend on a loose, poetic relationship with truth; instead, essayists should be more confident in the tradition of their form as a communication of information through art, not a privileging of art over information.

The term “lyric essay” emerged as a new name for a type of creative essay in 1997 when the Seneca Review began publishing work under this categorization. Associate editors at the time, Deborah Tall and John D’Agata, describe these essays as "‘poetic essays’ or ‘essayistic poems’ [that] give primacy to artfulness over the conveying of information. They forsake narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation. The lyric essay partakes of the poem in its density and shapeliness, its distillation of ideas and musicality of language. It partakes of the essay in its weight, in its overt desire to engage with facts, melding its allegiance to the actual with its passion for imaginative form."

Tall and D’Agata describe the lyric essay as reclaiming the original sense of essay as essai , attempt, or specifically “attempt at making sense.” Instead of statement, the lyric essay partakes of questions, pursuing an idea but not reaching any conclusion; the reader is meant not to be persuaded or convinced, but to follow the meanderings of the writer’s mind. The rationale behind the lyric essay stems from the claim that “perhaps we're drawn to the lyric now because it seems less possible (and rewarding) to approach the world through the front door, through the myth of objectivity” (Tall and D’Agata). In these essays, there is no objectivity because facts are filtered through the subjective consciousness of the writer, where they may become distorted. Although it does feature subjective consciousness, the lyric essay is not the same as a personal or memoir essay, in that its main purpose is not to narrate the personal experience of the writer. Instead of experience, the lyric essay engages primarily with ideas or inquiries, lending it an aspect of intellectual engagement that is not usually foregrounded in the personal essay. The tension comes when such engagement is blended with a poetic, subjective sensibility.

Laura Tetreault

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

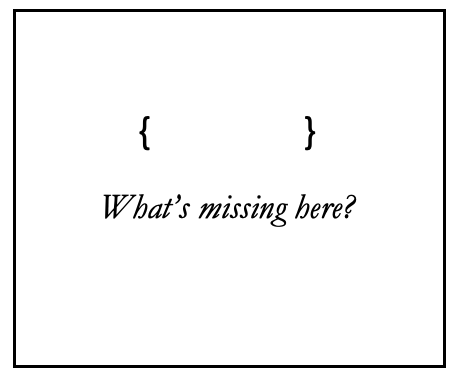

What’s Missing Here? A Fragmentary, Lyric Essay About Fragmentary, Lyric Essays

Julie marie wade on the mode that never quite feels finished.