- Earn HPCSA and SACNASP CPD Points

- I have spots and my skin burns

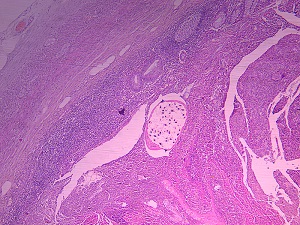

- A case of a 10 year old boy with a 3 week history of diarrhoea, vomiting and cough

- A case of fever and general malaise

- A case of persistant hectic fever

- A case of sudden rapid neurological deterioration in an HIV positive 27 year old female

- A case of swollen hands

- An unusual cause of fulminant hepatitis

- Case of a right axillary swelling

- Case of giant wart

- Case of recurrent meningitis

- Case of repeated apnoea and infections in a premature infant

- Case of sudden onset of fever, rash and neck pain

- Doctor, my sister is confused

- Eight month old boy with recurrent infections

- Enlarged Testicles

- Failure to thrive despite appropriate treatment

- Right Axillary Swelling

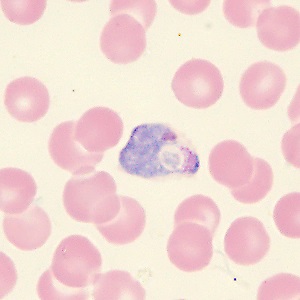

- Severe anaemia in HIV positive child

- The case of a floppy infant

- Two year old with spiking fevers and depressed level of consciousness

- 17 year old male with fever and decreased level of consciousness

- 3 TB Vignettes

- A 10 year old girl with a hard palate defect

- A case of decreased joint function, fever and rash

- Keep up while the storm is raging

- Fireworks of autoimmunity from birth

- My eyes cross at twilight

- A case of a 3 month old infant with bloody urine and stools

- A case of scaly annular plaques

- Case of eye injury and decreased vision

- My head hurts and I cannot speak?

- TB or not TB: a confusing case

- A 7 year old with severe muscle weakness and difficulty walking

- Why can I not walk today?

- 14 year old with severe hip pain

- A 9 year old girl presents with body swelling, shortness of breath and backache

- A sudden turn of events after successful therapy

- Declining CD4 count, despite viral suppression?

- Defaulted treatment

- 25 year old female presents with persistent flu-like symptoms

- A case of persistent bloody diarrhoea

- I’ve been coughing for so long

- A case of acute fever, rash and vomiting

- Adverse event following routine vaccination

- A case of cough, wasting and lymphadenopathy

- A case of lymphadenopathy and night sweats

- Case of enlarged hard tongue

- A high risk pregnancy

- A four year old with immunodeficiency

- Young girl with recurrent history of mycobacterial disease

- Immunodeficiency and failure to thrive

- Case of recurrent infections

- An 8 year old boy with recurrent respiratory infections

- 4 year old boy with recurrent bacterial infections

- Is this treatment failure or malnutrition

- 1. A Snapshot of the Immune System

- 2. Ontogeny of the Immune System

- 3. The Innate Immune System

- 4. MHC & Antigen Presentation

- 5. Overview of T Cell Subsets

- 6. Thymic T Cell Development

- 7. gamma/delta T Cells

- 8. B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- 9. Antibody Structure and Classes

- 10. Central and Peripheral Tolerance

- Immuno-Mexico 2024 Introduction

- Modulation of Peripheral Tolerance

- Metabolic Adaptation to Pathologic Milieu

- T Cell Exhaustion

- Suppression in the Context of Disease

- Redirecting Cytotoxicity

- Novel Therapeutic Strategies

- ImmunoInformatics

- Grant Writing

- Introduction to Immuno-Chile 2023

- Core Modules

- Gut Mucosal Immunity

- The Microbiome

- Gut Inflammation

- Viral Infections and Mucosal Immunity

- Colorectal Cancer

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Equity, Diversity, Inclusion in Academia

- Immuno-India 2023 Introduction

- Principles of Epigenetic Regulation

- Epigenetics Research in Systems Immunology

- Epigenetic (De)regulation in Non-Malignant Diseases

- Epigenetic (De)regulation in Immunodeficiency and Malignant Diseases

- Immunometabolism and Therapeutic Applications of Epigenetic Modifiers

- Immuno-Morocco 2023 Introduction

- Cancer Cellular Therapies

- Cancer Antibody Therapies

- Cancer Vaccines

- Immunobiology of Leukemia & Therapies

- Immune Landscape of the Tumour

- Targeting the Tumour Microenvironment

- Flow Cytometry

- Immuno-Zambia 2022 Introduction

- Immunity to Viral Infections

- Immunity to SARS-CoV2

- Basic Immunology of HIV

- Immunity to Tuberculosis

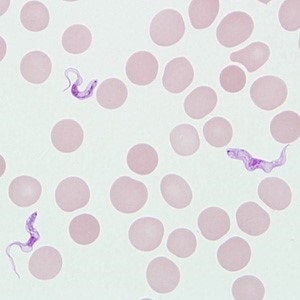

- Immunity to Malaria

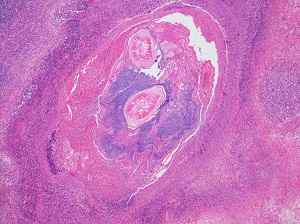

- Immunity to Schistosomiasis

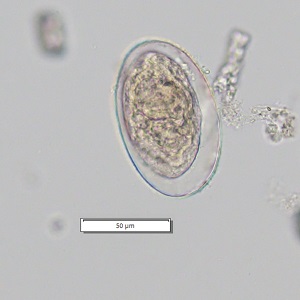

- Immunity to Helminths

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Academia

- Immuno-Argentina 2022 Introduction

- Dendritic Cells

- Trained Innate Immunity

- Gamma-Delta T cells

- Natural Killer Cell Memory

- Innate Immunity in Viral Infections

- Lectures – Innate Immunity

- T cells and Beyond

- Lectures – Cellular Immunity

- Strategies for Vaccine Design

- Lectures – Humoral Immunity

- Lectures – Vaccine development

- Lectures – Panel and Posters

- Immuno-Cuba 2022 Introduction

- Poster and Abstract Examples

- Immuno-Tunisia 2021 Introduction

- Basics of Anti-infectious Immunity

- Inborn Errors of Immunity and Infections

- Infection and Auto-Immunity

- Pathogen-Induced Immune Dysregulation & Cancer

- Understanding of Host-Pathogen Interaction & Applications (SARS-CoV-2)

- Day 1 – Basics of Anti-infectious Immunity

- Day 2 – Inborn Errors of Immunity and Infections

- Day 3 – Infection and Auto-immunity

- Day 4 – Pathogen-induced Immune Dysregulation and Cancer

- Day 5 – Understanding of Host-Pathogen Interaction and Applications

- Student Presentations

- Roundtable Discussions

- Orientation Meeting

- Poster Information

- Immuno-Colombia Introduction

- Core Modules Meeting

- Overview of Immunotherapy

- Check-Points Blockade Based Therapies

- Cancer Immunotherapy with γδ T cells

- CAR-T, armored CARs and CAR-NK therapies

- Anti-cytokines Therapies

- Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes (TIL)

- MDSC Promote Tumor Growth and Escape

- Immunological lab methods for patient’s follow-up

- Student Orientation Meeting

- Lectures – Week 1

- Lectures – Week 2

- Research Project

- Closing and Social

- Introduction to Immuno-Algeria 2020

- Hypersensitivity Reactions

- Immuno-Algeria Programme

- Online Lectures – Week 1

- Online Lectures – Week 2

- Student Presentations – Week 1

- Student Presentations – Week 2

- Introduction to Immuno-Ethiopia 2020

- Neutrophils

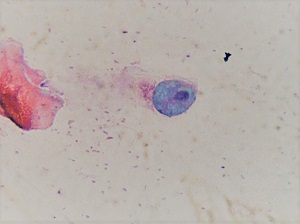

- Leishmaniasis – Transmission and Epidemiology

- Leishmaniasis – Immune Responses

- Leishmaniasis – Treatment and Vaccines

- Immunity to Helminth Infections

- Helminth immunomodulation on co-infections

- Malaria Vaccine Progress

- Immunity to Fungal Infections

- How to be successful scientist

- How to prepare a good academic CV

- Introduction to Immuno-Benin

- Immune Regulation in Pregnancy

- Immunity in infants and consequence of preeclampsia

- Schistosome infections and impact on Pregnancy

- Infant Immunity and Vaccines

- Regulation of Immunity & the Microbiome

- TGF-beta superfamily in infections and diseases

- Infectious Diseases in the Global Health era

- Immunity to Toxoplasma gondii

- A. melegueta inhibits inflammatory responses during Helminth Infections

- Host immune modulation by Helminth-induced products

- Immunity to HIV

- Immunity to Ebola

- Immunity to TB

- Genetic susceptibility in Tuberculosis

- Plant Extract Treatment for Diabetes

- Introduction to Immuno-South Africa 2019

- Models for Testing Vaccines

- Immune Responses to Vaccination

- IDA 2019 Quiz

- Introduction to Immuno-Jaipur

- Inflammation and autoinflammation

- Central and Peripheral Tolerance

- Autoimmunity and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases

- Autoimmunity & Dysregulation

- Novel Therapeutic strategies for Autoimmune Diseases

- Strategies to apply gamma/delta T cells for Immunotherapy

- Immune Responses to Cancer

- Tumour Microenvironment

- Cancer Immunotherapy

- Origin and perspectives of CAR T cells

- Metabolic checkpoints regulating immune responses

- Transplantation

- Primary Immunodeficiencies

- Growing up with Herpes virus

- Introduction to IUIS-ALAI-Mexico-ImmunoInformatics

- Introduction to Immunization Strategies

- Introduction to Immunoinformatics

- Omics Technologies

- Computational Modeling

- Machine Learning Methods

- Introduction to Immuno-Kenya

- Viruses hijacking host immune responses

- IFNs as 1st responders to virus infections

- HBV/HCV & Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Cytokines as biomarkers for HCV

- HTLV & T cell Leukemia

- HCMV and Cancers

- HPV and Cancers

- EBV-induced Oncogenesis

- Adenoviruses

- KSHV and HIV

- Ethics in Cancer Research

- Sex and gender in Immunity

- Introduction to Immuno-Iran

- Immunity to Leishmaniasis

- Breaking Tolerance: Autoimmunity & Dysregulation

- Introduction to Immuno-Morocco

- Cancer Epidemiology and Aetiology

- Pathogens and Cancer

- Immunodeficiency and Cancer

- Introduction to Immuno-Brazil

- 1. Systems Vaccinology

- 2. Vaccine Development

- 3. Adjuvants

- 4. DNA Vaccines

- 5. Mucosal Vaccines

- 6. Vaccines for Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Introduction to Immuno-Gambia

- Immuno-Gambia Photos

- 1. Infant Immunity and Vaccines

- 2. Dendritic Cells

- 3. Conventional T Cells

- 4. gamma/delta T Cells

- 5. Immunity to Viral Infections

- 6. Immunity to Helminth Infections

- 7. Immunity to TB

- 8. Immunity to Malaria

- 9. Flow Cytometry

- Introduction to Immuno-South Africa

- 1. Introduction to Immunization Strategies

- 2. Immune Responses to Vaccination

- 3. Models for Testing Vaccines

- 4. Immune Escape

- 5. Grant Writing

- Introduction to Immuno-Ethiopia

- 1. Neutrophils

- 3. Exosomes

- 5. Immunity to Leishmania

- 6. Immunity to HIV

- 7. Immunity to Helminth Infections

- 8. Immunity to TB

- 9. Grant Writing

- Introduction to ONCOIMMUNOLOGY-MEXICO

- ONCOIMMUNOLOGY-MEXICO Photos

- 1. Cancer Epidemiology and Etiology

- 2. T lymphocyte mediated immunity

- 3. Immune Responses to Cancer

- 4. Cancer Stem Cells and Tumor-initiating cells.

- 5. Tumor Microenvironment

- 6. Pathogens and Cancer

- 7. Cancer Immunotherapy

- 8. Flow cytometry approaches in cancer

- Introduction to the Immunology Course

- Immuno-Tunisia Photo

- 1. Overview of the Immune System

- 2. Role of cytokines in Immunity

- 3. Tolerance and autoimmunity

- 4. Genetics, Epigenetics and immunoregulation

- 5. Microbes and immunoregulation

- 6. Inflammation and autoinflammation

- 7. T cell mediated autoimmune diseases

- 8. Antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases

- Introduction to the Immunology Symposium

- Immuno-South Africa Photo

- 1. Antibody Generation by B cells

- 2. Mucosal Immunity

- 3. Immunity to TB

- 4. Immunity to Malaria

- 5. Immunity to HIV

- 6. Defining a Biomarker

- 7. Grant Writing Exercise

- Immuno-Colombia Photo

- 1. Overview of Complement

- 2. Transplantation

- 3. Immune Regulation in Pregnancy

- 4. Breaking Tolerance: Autoimmunity & Dysregulation

- 5. Mucosal Immunity & Immunopathology

- 6. Regulation of Immunity & the Microbiome

- 7. Epigenetics & Modulation of Immunity

- 8. Primary Immunodeficiencies

- 9. Anti-tumour Immunity

- 10. Cancer Immunotherapy

- Introduction

- Immune Cells

- NCDs and Multimorbidity

- Mosquito Vector Biology

- Vaccines and Other Interventions

- Autoimmunity

- Career Development

- SUN Honours Introduction

- A Snapshot of the Immune System

- Ontogeny of the Immune System

- The Innate Immune System

- MHC & Antigen Presentation

- Overview of T Cell Subsets

- B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- Antibody Structure and Classes

- Cellular Immunity and Immunological Memory

- Infectious Diseases Immunology

- Vaccinology

- Mucosal Immunity & Immunopathology

- Central & Peripheral Tolerance

- Epigenetics & Modulation of Immunity

- T cell and Ab-mediated autoimmune diseases

- Immunology of COVID-19 Vaccines

- 11th IDA 2022 Introduction

- Immunity to COVID-19

- Fundamentals of Immunology

- Fundamentals of Infection

- Integrating Immunology & Infection

- Infectious Diseases Symposium

- EULAR Symposium

- Thymic T Cell Development

- Immune Escape

- Genetics, Epigenetics and immunoregulation

- AfriBop 2021 Introduction

- Adaptive Immunity

- Fundamentals of Infection 2

- Fundamentals of Infection 3

- Host pathogen Interaction 1

- Host pathogen Interaction 2

- Student 3 minute Presentations

- 10th IDA 2021 Introduction

- Day 1 – Lectures

- Day 2 – Lectures

- Day 3 – Lectures

- Day 4 – Lectures

- Afribop 2020 Introduction

- WT PhD School Lectures 1

- EULAR symposium

- WT PhD School Lectures 2

- Host pathogen interaction 1

- Host pathogen interaction 2

- Bioinformatics

- Introduction to VACFA Vaccinology 2020

- Overview of Vaccinology

- Basic Principles of Immunity

- Adverse Events Following Immunization

- Targeted Immunization

- Challenges Facing Vaccination

- Vaccine Stakeholders

- Vaccination Questions Answered

- Malaria Vaccines

- IDA 2018 Introduction

- Vaccine Development

- Immune Escape by Pathogens

- Immunity to Viral Infections Introduction

- Flu, Ebola & SARS

- Antiretroviral Drug Treatments

- Responsible Conduct in Research

- Methods for Enhancing Reproducibility

- 6. B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- 7. Antibody Structure and Classes

- CD Nomenclature

- 1. Transplantation

- 2. Central & Peripheral Tolerance

- 8. Inflammation and autoinflammation

- 9. T cell mediated autoimmune diseases

- 10. Antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases

- 1. Primary Immunodeficiencies

- Cancer Stem Cells and Tumour-initiating Cells

- 6. Tolerance and Autoimmunity

- Discovery of the Thymus as a central immunological organ

- History of Immune Response

- History of Immunoglobulin molecules

- History of MHC – 1901 – 1970

- History of MHC – 1971 – 2011

- SAIS/Immunopaedia Webinars 2022

- Metabolic control of T cell differentiation during immune responses to cancer

- Microbiome control of host immunity

- Shaping of anti-tumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment

- The unusual COVID-19 pandemic: the African story

- Immune responses to SARS-CoV-2

- Adaptive Immunity and Immune Memory to SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19

- HIV prevention- antibodies and vaccine development (part 2)

- HIV prevention- antibodies and vaccine development (part 1)

- Immunopathology of COVID 19 lessons from pregnancy and from ageing

- Clinical representation of hyperinflammation

- In-depth characterisation of immune cells in Ebola virus

- Getting to the “bottom” of arthritis

- Immunoregulation and the tumor microenvironment

- Harnessing innate immunity from cancer therapy to COVID-19

- Flynn Webinar: Immune features associated natural infection

- Flynn Webinar: What immune cells play a role in protection against M.tb re-infection?

- JoAnne Flynn: BCG IV vaccination induces sterilising M.tb immunity

- IUIS-Immunopaedia-Frontiers Webinar on Immunology taught by P. falciparum

- COVID-19 Cytokine Storm & Paediatric COVID-19

- Immunothrombosis & COVID-19

- Severe vs mild COVID-19 immunity and Nicotinamide pathway

- BCG & COVID-19

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Antibody responses and serology testing

- Flow Cytometry Part 1

- Flow Cytometry Part 2

- Flow Cytometry Part 3

- Lateral Flow

- Diagnostic Tools

- Diagnostic Tests

- HIV Life Cycle

- ARV Drug Information

- ARV Mode of Action

- ARV Drug Resistance

- Declining CD4 count

- Ambassador of the Month – 2024

- North America

- South America

- Ambassador of the Month – 2023

- Ambassador of the Month – 2022

- The Day of Immunology 2022

- AMBASSADOR SCI-TALKS

- The Day of Immunology 2021

- Ambassador of the Month – 2021

- Ambassador of the Month-2020

- Ambassador of the Month – 2019

- Ambassador of the Month – 2018

- Ambassador of the Month – 2017

- Host an IUIS Course in 2025

- COLLABORATIONS

We will not share your details

Infectious Diseases

Please choose a Case Study below

© 2004 - 2024 Immunopaedia.org.za Sitemap - Privacy Policy - Cookie Policy - PAIA - Terms & Conditions

Website designed by Personalised Promotions in association with SA Medical Specialists .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- CLINICAL CASES

- ONLINE COURSES

- AMBASSADORS

- TREATMENT & DIAGNOSTICS

Case report

Case reports submitted to BMC Infectious Diseases should make a contribution to medical knowledge and must have educational value or highlight the need for a change in clinical practice or diagnostic/prognostic approaches. We will not consider reports on topics that have already been well characterized or where other, similar, cases have already been published.

BMC Infectious Diseases will not consider case reports describing preventive or therapeutic interventions, as these generally require stronger evidence.

BMC Infectious Diseases will not consider case reports whose main message is the clinical use of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) for the identification of a pathogen if it has been already previously reported in the literature.

BMC Infectious Diseases welcomes well-described reports of cases that include the following: • Unreported or unusual side effects or adverse interactions involving medications. • Unexpected or unusual presentations of a disease. • New associations or variations in disease processes. • Presentations, diagnoses and/or management of new and emerging diseases. • An unexpected association between diseases or symptoms. • An unexpected event in the course of observing or treating a patient. • Findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease or an adverse effect.

Authors must describe how the case report is rare or unusual as well as its educational and/or scientific merits in the covering letter that will accompany the submission of the manuscript. Case report submissions will be assessed by the Editors and will be sent for peer review if considered appropriate for the journal.

Case reports must include relevant positive and negative findings from history, examination and investigation, and can include clinical photographs, provided these are accompanied by a statement that written consent to publish was obtained from the patient(s). Case reports should include an up-to-date review of all previous cases in the field. Authors should follow the CARE guidelines and the CARE checklist should be provided as an additional file.

Authors should seek written and signed consent to publish the information from the patient(s) or their guardian(s) prior to submission. The submitted manuscript must include a statement that this consent was obtained in the consent to publish section as detailed in our editorial policies .

Professionally produced Visual Abstracts BMC Infectious Diseases will consider visual abstracts. As an author submitting to the journal, you may wish to make use of services provided at Springer Nature for high quality and affordable visual abstracts where you are entitled to a 20% discount. Click here to find out more about the service, and your discount will be automatically be applied when using this link .

Preparing your manuscript

The information below details the section headings that you should include in your manuscript and what information should be within each section.

Please note that your manuscript must include a 'Declarations' section including all of the subheadings (please see below for more information).

Title page

The title page should:

- "A versus B in the treatment of C: a randomized controlled trial", "X is a risk factor for Y: a case control study", "What is the impact of factor X on subject Y: A systematic review, A case report etc."

- or, for non-clinical or non-research studies: a description of what the article reports

- if a collaboration group should be listed as an author, please list the Group name as an author. If you would like the names of the individual members of the Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please include this information in the “Acknowledgements” section in accordance with the instructions below

- Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT , do not currently satisfy our authorship criteria . Notably an attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work, which cannot be effectively applied to LLMs. Use of an LLM should be properly documented in the Methods section (and if a Methods section is not available, in a suitable alternative part) of the manuscript

- indicate the corresponding author

The Abstract should not exceed 350 words. Please minimize the use of abbreviations and do not cite references in the abstract. The abstract must include the following separate sections:

- Background: why the case should be reported and its novelty

- Case presentation: a brief description of the patient’s clinical and demographic details, the diagnosis, any interventions and the outcomes

- Conclusions: a brief summary of the clinical impact or potential implications of the case report

Keywords

Three to ten keywords representing the main content of the article.

The Background section should explain the background to the case report or study, its aims, a summary of the existing literature.

Case presentation

This section should include a description of the patient’s relevant demographic details, medical history, symptoms and signs, treatment or intervention, outcomes and any other significant details.

Discussion and Conclusions

This should discuss the relevant existing literature and should state clearly the main conclusions, including an explanation of their relevance or importance to the field.

List of abbreviations

If abbreviations are used in the text they should be defined in the text at first use, and a list of abbreviations should be provided.

Declarations

All manuscripts must contain the following sections under the heading 'Declarations':

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication, availability of data and materials, competing interests, authors' contributions, acknowledgements.

- Authors' information (optional)

Please see below for details on the information to be included in these sections.

If any of the sections are not relevant to your manuscript, please include the heading and write 'Not applicable' for that section.

Manuscripts reporting studies involving human participants, human data or human tissue must:

- include a statement on ethics approval and consent (even where the need for approval was waived)

- include the name of the ethics committee that approved the study and the committee’s reference number if appropriate

Studies involving animals must include a statement on ethics approval and for experimental studies involving client-owned animals, authors must also include a statement on informed consent from the client or owner.

See our editorial policies for more information.

If your manuscript does not report on or involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

If your manuscript contains any individual person’s data in any form (including any individual details, images or videos), consent for publication must be obtained from that person, or in the case of children, their parent or legal guardian. All presentations of case reports must have consent for publication.

You can use your institutional consent form or our consent form if you prefer. You should not send the form to us on submission, but we may request to see a copy at any stage (including after publication).

See our editorial policies for more information on consent for publication.

If your manuscript does not contain data from any individual person, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

All manuscripts must include an ‘Availability of data and materials’ statement. Data availability statements should include information on where data supporting the results reported in the article can be found including, where applicable, hyperlinks to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study. By data we mean the minimal dataset that would be necessary to interpret, replicate and build upon the findings reported in the article. We recognise it is not always possible to share research data publicly, for instance when individual privacy could be compromised, and in such instances data availability should still be stated in the manuscript along with any conditions for access.

Authors are also encouraged to preserve search strings on searchRxiv https://searchrxiv.org/ , an archive to support researchers to report, store and share their searches consistently and to enable them to review and re-use existing searches. searchRxiv enables researchers to obtain a digital object identifier (DOI) for their search, allowing it to be cited.

Data availability statements can take one of the following forms (or a combination of more than one if required for multiple datasets):

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]

- The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- The data that support the findings of this study are available from [third party name] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [third party name].

- Not applicable. If your manuscript does not contain any data, please state 'Not applicable' in this section.

More examples of template data availability statements, which include examples of openly available and restricted access datasets, are available here .

BioMed Central strongly encourages the citation of any publicly available data on which the conclusions of the paper rely in the manuscript. Data citations should include a persistent identifier (such as a DOI) and should ideally be included in the reference list. Citations of datasets, when they appear in the reference list, should include the minimum information recommended by DataCite and follow journal style. Dataset identifiers including DOIs should be expressed as full URLs. For example:

Hao Z, AghaKouchak A, Nakhjiri N, Farahmand A. Global integrated drought monitoring and prediction system (GIDMaPS) data sets. figshare. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.853801

With the corresponding text in the Availability of data and materials statement:

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]. [Reference number]

If you wish to co-submit a data note describing your data to be published in BMC Research Notes , you can do so by visiting our submission portal . Data notes support open data and help authors to comply with funder policies on data sharing. Co-published data notes will be linked to the research article the data support ( example ).

All financial and non-financial competing interests must be declared in this section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of competing interests. If you are unsure whether you or any of your co-authors have a competing interest please contact the editorial office.

Please use the authors initials to refer to each authors' competing interests in this section.

If you do not have any competing interests, please state "The authors declare that they have no competing interests" in this section.

All sources of funding for the research reported should be declared. If the funder has a specific role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript, this should be declared.

The individual contributions of authors to the manuscript should be specified in this section. Guidance and criteria for authorship can be found in our editorial policies .

Please use initials to refer to each author's contribution in this section, for example: "FC analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the hematological disease and the transplant. RH performed the histological examination of the kidney, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript."

Please acknowledge anyone who contributed towards the article who does not meet the criteria for authorship including anyone who provided professional writing services or materials.

Authors should obtain permission to acknowledge from all those mentioned in the Acknowledgements section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of acknowledgements and authorship criteria.

If you do not have anyone to acknowledge, please write "Not applicable" in this section.

Group authorship (for manuscripts involving a collaboration group): if you would like the names of the individual members of a collaboration Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please ensure that the title of the collaboration Group is included on the title page and in the submission system and also include collaborating author names as the last paragraph of the “Acknowledgements” section. Please add authors in the format First Name, Middle initial(s) (optional), Last Name. You can add institution or country information for each author if you wish, but this should be consistent across all authors.

Please note that individual names may not be present in the PubMed record at the time a published article is initially included in PubMed as it takes PubMed additional time to code this information.

Authors' information

This section is optional.

You may choose to use this section to include any relevant information about the author(s) that may aid the reader's interpretation of the article, and understand the standpoint of the author(s). This may include details about the authors' qualifications, current positions they hold at institutions or societies, or any other relevant background information. Please refer to authors using their initials. Note this section should not be used to describe any competing interests.

Footnotes can be used to give additional information, which may include the citation of a reference included in the reference list. They should not consist solely of a reference citation, and they should never include the bibliographic details of a reference. They should also not contain any figures or tables.

Footnotes to the text are numbered consecutively; those to tables should be indicated by superscript lower-case letters (or asterisks for significance values and other statistical data). Footnotes to the title or the authors of the article are not given reference symbols.

Always use footnotes instead of endnotes.

Examples of the Vancouver reference style are shown below.

See our editorial policies for author guidance on good citation practice

Web links and URLs: All web links and URLs, including links to the authors' own websites, should be given a reference number and included in the reference list rather than within the text of the manuscript. They should be provided in full, including both the title of the site and the URL, as well as the date the site was accessed, in the following format: The Mouse Tumor Biology Database. http://tumor.informatics.jax.org/mtbwi/index.do . Accessed 20 May 2013. If an author or group of authors can clearly be associated with a web link, such as for weblogs, then they should be included in the reference.

Example reference style:

Article within a journal

Smith JJ. The world of science. Am J Sci. 1999;36:234-5.

Article within a journal (no page numbers)

Rohrmann S, Overvad K, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Jakobsen MU, Egeberg R, Tjønneland A, et al. Meat consumption and mortality - results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Medicine. 2013;11:63.

Article within a journal by DOI

Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Clinical implications of dysregulated cytokine production. Dig J Mol Med. 2000; doi:10.1007/s801090000086.

Article within a journal supplement

Frumin AM, Nussbaum J, Esposito M. Functional asplenia: demonstration of splenic activity by bone marrow scan. Blood 1979;59 Suppl 1:26-32.

Book chapter, or an article within a book

Wyllie AH, Kerr JFR, Currie AR. Cell death: the significance of apoptosis. In: Bourne GH, Danielli JF, Jeon KW, editors. International review of cytology. London: Academic; 1980. p. 251-306.

OnlineFirst chapter in a series (without a volume designation but with a DOI)

Saito Y, Hyuga H. Rate equation approaches to amplification of enantiomeric excess and chiral symmetry breaking. Top Curr Chem. 2007. doi:10.1007/128_2006_108.

Complete book, authored

Blenkinsopp A, Paxton P. Symptoms in the pharmacy: a guide to the management of common illness. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998.

Online document

Doe J. Title of subordinate document. In: The dictionary of substances and their effects. Royal Society of Chemistry. 1999. http://www.rsc.org/dose/title of subordinate document. Accessed 15 Jan 1999.

Online database

Healthwise Knowledgebase. US Pharmacopeia, Rockville. 1998. http://www.healthwise.org. Accessed 21 Sept 1998.

Supplementary material/private homepage

Doe J. Title of supplementary material. 2000. http://www.privatehomepage.com. Accessed 22 Feb 2000.

University site

Doe, J: Title of preprint. http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/mydata.html (1999). Accessed 25 Dec 1999.

Doe, J: Trivial HTTP, RFC2169. ftp://ftp.isi.edu/in-notes/rfc2169.txt (1999). Accessed 12 Nov 1999.

Organization site

ISSN International Centre: The ISSN register. http://www.issn.org (2006). Accessed 20 Feb 2007.

Dataset with persistent identifier

Zheng L-Y, Guo X-S, He B, Sun L-J, Peng Y, Dong S-S, et al. Genome data from sweet and grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). GigaScience Database. 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.5524/100012 .

Figures, tables and additional files

See General formatting guidelines for information on how to format figures, tables and additional files.

Submit manuscript

Important information

Editorial board

For authors

For editorial board members

For reviewers

- Manuscript editing services

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 3.7 - 2-year Impact Factor 3.6 - 5-year Impact Factor 1.283 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 1.055 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 28 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 148 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 6,949,317 downloads 28,444 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

Peer-review Terminology

The following summary describes the peer review process for this journal:

Identity transparency: Single anonymized

Reviewer interacts with: Editor

Review information published: Review reports. Reviewer Identities reviewer opt in. Author/reviewer communication

More information is available here

- Follow us on Twitter

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Volume 16, Number 1—January 2010

Books and Media

Case studies in infectious disease.

Cite This Article

The authors have assembled a collection of case studies about the 40 infectious diseases that cause the most illness and death worldwide. Each chapter begins with a brief case presentation. This example is followed by a section on microbiologic aspects of the organism, including the pathophysiology of infection. The host response is then described, followed by a discussion of clinical manifestations, diagnostic methods, and treatment options, including prevention. A summary highlights salient points of each section. References, suggestions for further reading, and websites for additional information are all provided. Chapters conclude with a series of questions (answers are given at the end of the book).

The book is meant for use by medical students in a microbiology course, but it can also be used by any clinician who wants a concise review of the pathogens that cause infectious diseases. The case presentations are short and not presented as conditions having an unknown cause, but they rather serve as a clinical starting point to open discussion. The microbiology sections are geared more toward the student in a microbiology course and tend to have more details than are needed by a practicing clinician. The sections on patient symptoms are generally quite good and are inclusive. The varied clinical manifestations, particularly of the tropical diseases, are presented in an easy-to-understand format. The level of detail given provides a thorough yet succinct picture of each disease. The sections on diagnosis are generally inclusive, although a few did not mention some available diagnostic options used in the United States; this may have been due to differences in the availability of some tests in the United Kingdom, where many of the authors are based. The treatment sections tend to be abbreviated and frequently do not include the length of therapy and some other details that a practicing clinician would want to know. For those needing specific therapy guidelines, another source will be necessary.

The summary sections are quite good and are an excellent quick reference source if one wants just the highlights and a brief summary about the pathogen and disease. The questions at the end tend to be multiple choice with several possible correct answers for each one; they are not structured to prepare for testing purposes (such as for a board review). The websites are helpful sources for downloadable slides as well as for further information if more details are wanted.

The only chapter that was confusing was that on coxsackie viruses. The authors kept referring to other enteroviruses. The chapter could benefit from either fewer references to other enteroviruses or renaming it to be a section on enteroviruses in general.

Case Studies in Infectious Diseases is a valuable compilation of information on the most common diseases that cause illness and death worldwide. The presentation format with distinct sections makes it readable and well suited for either students just learning about the pathogens causing infectious disease or clinicians who need an update. The level of detail is well thought out and gives the reader a useful summary of each pathogen and disease state. The condensed presentations make it a good reference source for those with insufficient time to read through more detailed textbooks.

DOI: 10.3201/eid1601.091254

Related Links

- More Books and Media Articles

Table of Contents – Volume 16, Number 1—January 2010

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Philip S. Brachman, Jr, Atlanta ID Group, Piedmont Hospital, 2001 Peachtree Rd, Ste 640, Atlanta, GA 30309, USA

Comment submitted successfully, thank you for your feedback.

There was an unexpected error. Message not sent.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Article Citations

Highlight and copy the desired format.

Metric Details

Article views: 1321.

Data is collected weekly and does not include downloads and attachments. View data is from .

What is the Altmetric Attention Score?

The Altmetric Attention Score for a research output provides an indicator of the amount of attention that it has received. The score is derived from an automated algorithm, and represents a weighted count of the amount of attention Altmetric picked up for a research output.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Emerg Infect Dis

- v.16(1); 2010 Jan

Case Studies in Infectious Disease

Peter M. Lydyard, Michael F. Cole, John Holton, William L. Irving, Nino Porakishvili, Pradhib Venkatesan, Katherine N. Ward Garland Science, New York, NY, USA, 2010 ISBN: 978-0-8153-4142-0 Pages: 608; Price: US $50.00.

The authors have assembled a collection of case studies about the 40 infectious diseases that cause the most illness and death worldwide. Each chapter begins with a brief case presentation. This example is followed by a section on microbiologic aspects of the organism, including the pathophysiology of infection. The host response is then described, followed by a discussion of clinical manifestations, diagnostic methods, and treatment options, including prevention. A summary highlights salient points of each section. References, suggestions for further reading, and websites for additional information are all provided. Chapters conclude with a series of questions (answers are given at the end of the book).

The book is meant for use by medical students in a microbiology course, but it can also be used by any clinician who wants a concise review of the pathogens that cause infectious diseases. The case presentations are short and not presented as conditions having an unknown cause, but they rather serve as a clinical starting point to open discussion. The microbiology sections are geared more toward the student in a microbiology course and tend to have more details than are needed by a practicing clinician. The sections on patient symptoms are generally quite good and are inclusive. The varied clinical manifestations, particularly of the tropical diseases, are presented in an easy-to-understand format. The level of detail given provides a thorough yet succinct picture of each disease. The sections on diagnosis are generally inclusive, although a few did not mention some available diagnostic options used in the United States; this may have been due to differences in the availability of some tests in the United Kingdom, where many of the authors are based. The treatment sections tend to be abbreviated and frequently do not include the length of therapy and some other details that a practicing clinician would want to know. For those needing specific therapy guidelines, another source will be necessary.

The summary sections are quite good and are an excellent quick reference source if one wants just the highlights and a brief summary about the pathogen and disease. The questions at the end tend to be multiple choice with several possible correct answers for each one; they are not structured to prepare for testing purposes (such as for a board review). The websites are helpful sources for downloadable slides as well as for further information if more details are wanted.

The only chapter that was confusing was that on coxsackie viruses. The authors kept referring to other enteroviruses. The chapter could benefit from either fewer references to other enteroviruses or renaming it to be a section on enteroviruses in general.

Case Studies in Infectious Diseases is a valuable compilation of information on the most common diseases that cause illness and death worldwide. The presentation format with distinct sections makes it readable and well suited for either students just learning about the pathogens causing infectious disease or clinicians who need an update. The level of detail is well thought out and gives the reader a useful summary of each pathogen and disease state. The condensed presentations make it a good reference source for those with insufficient time to read through more detailed textbooks.

Suggested citation for this article : Brachman PS Jr. Case studies in infectious disease [book review]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet] 2010 Jan [ date cited ]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/16/1/172a.htm

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

4: Pharyngitis

Frank S. Yu; Jonathan C. Cho

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Patient presentation.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Chief Complaint

“Mommy, my throat is on fire!”

History of Present Illness

JT is a 7-year-old Chinese American female, accompanied by her mother, who presents to the community pharmacy with complaints of sore throat and fever, looking for medications to take to relieve her symptoms. She is fussy and describes the pain when she swallows as feeling if her throat is “on fire.” Her symptoms began yesterday morning, and she has only tried drinking a pei pa koa syrup containing medicinal herbs (main active herb is elm bark) and honey to relieve the sore throat. This provided some relief but the pain has been getting worse. She did not have a temperature taken, but her forehead was hot to the touch. She was not given any medications to relieve the fever. She was dressed with additional clothing and blankets to “sweat the fever out,” but the fever still persisted. She reports that there may have been other sick classmates. She denies a prior history of sore throat.

Past Medical History

Attention-deficit disorder, recurrent otitis media (resolved)

Surgical History

Family history.

Non-contributory

Social History

Ear tubes at age 2

Amoxicillin (throat swelling, difficulty breathing)

Home Medications

Methylphenidate ER 18 mg PO daily

Physical Examination

Vital signs.

Temp 101.9°F (oral), Ht 4′4″, Wt 29.55 kg

Appears uncomfortable, tired, grimacing when swallowing

Anterior cervical lymph nodes enlarged and tender; tonsils moist, red, with white exudates

Point-of-Care GAS Rapid Antigen Detection Test

1. What is the most common pathogen responsible for acute bacterial pharyngitis in children?

A. Corynebacterium diphtheriae

B. Neisseria gonorrhoeae

C. Group C streptococcus

D. Group A streptococcus

2. What signs and symptoms in this patient definitely discriminate between GAS pharyngitis rather than viral pharyngitis?

A. Tonsils with white exudates

B. Temperature 101.9°F

C. Pain on swallowing

D. All of the above

3. If GAS is suspected, what age range is typically excluded for testing for GAS?

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Great Diseases

- Pre-College Programs

- Undergraduate Internships

- Resources for Building Inclusivity in Science

- Publications

Center for Science Education at Tufts University

- The Great Diseases

- Request Access

- Student Portal

- Online Courses

- Partnerships

- Infectious Diseases (ID)

- Neurological Disorders (ND)

- Metabolic Disease (MD)

- Cancer (CA)

- Order Printing

- - Online Courses

- - Webinars

- - Workshops

- - Partnerships

- - Community

- - COVID-19

- - Infectious Diseases (ID)

- - Neurological Disorders (ND)

- - Metabolic Disease (MD)

- - Cancer (CA)

- - Order Printing

Case Studies

Case study 1: what is this mysterious disease.

This case study examines the earliest reports of what we now know were AIDS cases. The medical community was perplexed and the public was scared because the cause of this disease and mode of transmission were not understood. Students will use the data provided to think about how scientists can look for meaningful patterns in data and how they practice formulating a scientific question — that is, one that can be answered through experiment or observation.

Many unresolved questions remain at the end of the lesson, illustrating the iterative nature of science and how science is not a list of facts to memorize but a process of discovery. The concepts presented here align well with those presented in ID Unit 1 .

Download Case Study 1 here .

Case Study 2 — Do bacteria cause stomach ulcers? Applying Koch’s postulates

This study grapples with the problem of arriving at causation from correlation with respect to infectious disease. First, students will discuss their stomach ulcer homework, and they will compare their predictions to real life excess-acid experiments in people. This is a key point because the results support the hypothesis; however, they do not prove causation. Next, students will design experiments that predict results for experiments to test the hypothesis that stomach ulcers are caused by an infectious agent. Students will then consider the implications of not being able to fulfill all of Koch’s postulates with Helicobacter pylori.

Download Case Study 2 here .

Case Study 3 — Where did HIV come from? Tracing the origin of disease

Prior to 1980, there were no reports of AIDS in the medical literature, but by 1987 the World Health Organization reported that an estimated 5-10 million people were living with HIV worldwide. The rapid emergence of this disease was indication that it might have “jumped” from an animal host. This is similar to flu viruses that are thought to have originated in birds. Most human viral diseases do originate in animals. In this case study, students develop a hypothesis and make predictions. Throughout the lesson, students will analyze and interpret a variety of data. The accumulation of results helps to support the hypothesis that HIV originated from a chimp virus.

Download Case Study 3 here .

Case Study 4 — Antibiotic resistance

In this study, students synthesize information from different studies to arrive at a model to explain how human antibiotic resistant infections may be linked to antibiotic use on farms. Importantly, the evidence does not prove causation, but conveys to students how an accumulation of evidence compels us to adopt a particular model. The concept of selective pressure is reviewed.

Download Case Study 4 here .

Case Study 5 — How would you know if you were infected with HIV?

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that 1 in 4 new HIV infections is among youth ages 13-24, yet most do not know they are infected. In this case study, students engage in data analysis and interpretation to demonstrate that symptoms of initial HIV infection can go unrecognized for years. Classical symptoms of AIDS may only become apparent years after the initial HIV infection. Meanwhile, the infected individual could be infecting others. Students learn what behaviors are associated with high risk of infection and the importance of getting tested if they engage in these high-risk behaviors.

Download Case Study 5 here .

Disclaimer | Non-Discrimination | Privacy | Terms for Creating and Maintaining Sites

2020 DPDx Case Studies

2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005

56-year-old Korean immigrant sought medical attention for non-specific abdominal pain and mild, intermittent diarrhea.

A 42-year-old State Park employee sought medical care due to fatigue, insomnia, intermittent bloating, and mild anemia.

A 45-year-old male who recently returned from a trip overseas to Korea presented to his primary care clinic for an annual checkup at a clinic in the United States.

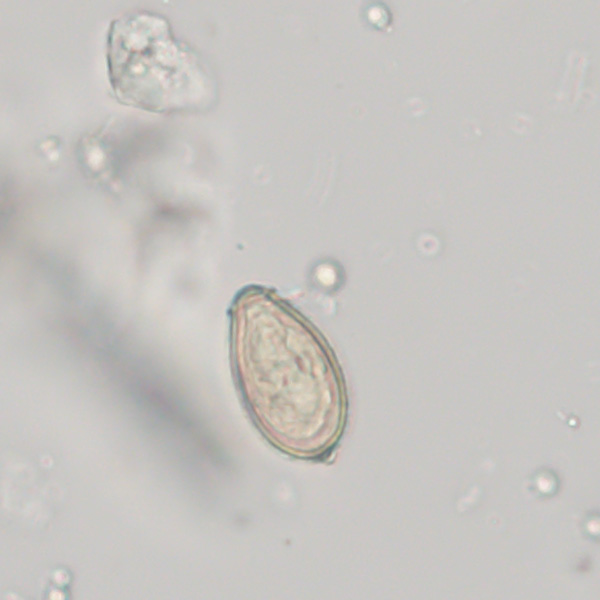

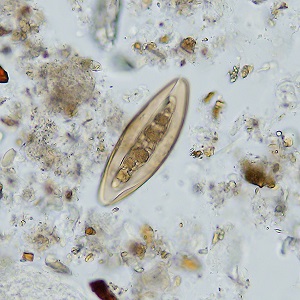

During a field study in Cambodia, stool ova and parasite (O&P) examinations were performed on participants in rural villages. Unusual eggs were found in the formalin-ethyl acetate concentrated stool specimen of one middle-aged woman.

A 53-year-old woman from Florida presented to a dermatology clinic with a raised, itchy, red rash on her torso that persisted over the past six months and did not respond to topical treatments.

A 25-year-old man with fever and myalgia presented to an urgent care clinic in Pennsylvania, and no travel history was obtained at that time.

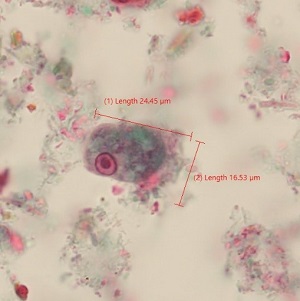

As part of a refugee screening program, a young child had a fecal ova and parasite (O & P) examination which included a formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) fecal concentration.

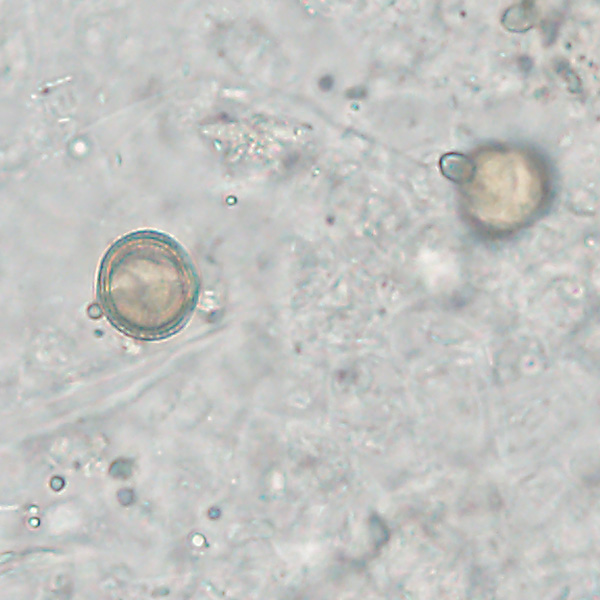

At a regional diagnostic laboratory, where specimens from the southeastern United States are evaluated, the objects shown in Figures A and B were observed on a wet mount preparation from a fecal formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentrate.

In Singapore, a 54-year-old man with an extensive travel history to Vietnam, Thailand, and France presented to a clinic with prolonged fever, urticarial rash, and muscle aches.

A 67-year-old male from Houston, TX sought medical evaluation following 3 days of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fatigue after returning from a two-week summer vacation in Nairobi, Kenya.

An 18-year-old male living in India presented with recurrent periumbilical abdominal pain for one week. Other symptoms included mild anemia and eosinophilic leukocytosis.

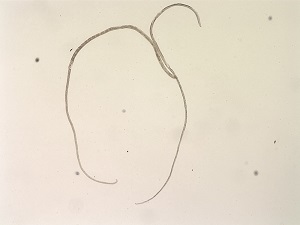

A 24-year-old man from Thailand presented to his healthcare provider with complaints of gastrointestinal pain and weight loss. He also reported seeing thin worms in his stool on rare occasion.

A group of college students traveled to Brazil on a rafting and camping trip for two weeks. Malaria prophylaxis was highly recommended however one student declined.

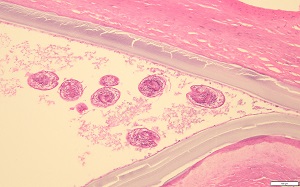

A 58 year-old-man from Peru visiting relatives in the United States was killed in a traffic accident. An autopsy revealed cysts in his liver of which a few were excised and sent to pathology for identification.

A 4-year-old boy went for a routine medical examination with his parents after they returned from a one-year sabbatical, studying primates in their natural habitat in central Africa.

A 24-year-old female exchange student from Guinea reported to the clinic with headaches, itchy skin, and enlarged lymph nodes.

A 60-year-old non-smoking male patient presented to his primary care physician with a chronic cough and shortness of breath. He reported no recent travel outside of the Southern United States.

A 29-year-old female patient presented to her primary care physician reporting a 15-day history of whitish, vaginal discharge associated with itching.

A 3-year-old boy was seen by a pediatrician for gastrointestinal pain and watery diarrhea. His parents conveyed that he has a propensity for putting insects in his mouth and sometimes eating them.

A 29-year-old man sought medical attention with his health care provider with a complaint of itchy maculopapular rash on several areas of his body.

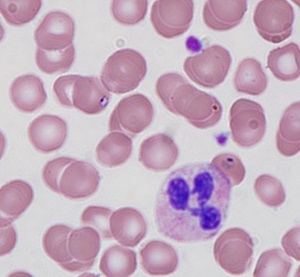

A 63-year-old man returned from visiting with family in Nigeria. He developed fever, chills and a mild headache three days before presenting to the clinic.

A 69-year-old male patient from a rural town in Georgia experiencing symptoms of productive cough with blood, hematochezia (rectal bleeding) and chest pain sought medical attention at the county health clinic.

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/ .

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

American Society for Microbiology

- Browse By Content Type

Browse By Content Type Case Study

Uncover interesting and unusual findings in the microbiology laboratory by browsing case studies, shared by your clinical and public health microbiology colleagues. Cases can be used as a teaching tool or to further your individual knowledge of the field.

- Sign up for CPHM Virtual Journal Club.

- Learn ASM’s position on the VALID Act.

- Apply for a CPEP Fellowship.

- Read top clinical microbiology textbooks online with ClinMicroNow.

- Get ASM journal articles on CPHM straight to my inbox.

ASM Microbe 2024 Registration Now Open!

Discover asm membership, get published in an asm journal.

BioEd Online

Science teacher resources from baylor college of medicine.

- Log in / Register

Infectious Disease Case Study

- Download Lesson and Student Pages

- Print Materials List

- Length: 60 Minutes

Students use evidence to determine whether a patient has a cold, flu or strep infection, and they also learn the differences between bacterial and viral infections.

This activity is from The Science of Microbes Teacher's Guide , and is most appropriate for use with students in grades 6-8. Lessons from the guide may be used with other grade levels as deemed appropriate.

The guide is available in print format.

This work was developed in partnership with the Baylor-UT Houston Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program.

Teacher Background

Objectives and standards, materials and setup, procedure and extensions, handouts and downloads.

Many different microorganisms can infect the human respiratory system, causing symptoms such as fever, runny nose or sore throat. Even the common cold, which may range from mild to serious, can be caused by any of more than 200 viruses! Colds are among the leading causes of visits to physicians in the United States, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that 22 million school days are lost in the U.S. each year due to the common cold. Usually, cold symptoms appear within two to three days of infection and include: mucus buildup in the nose, swelling of sinuses, cough, headache, sore throat, sneezing and mild fever (particularly in infants and young children). The body’s immune system, which protects against disease-causing microbes, almost always is able to eliminate the viruses responsible for a cold.

Flu (or influenza) often is more serious than the common cold. Caused by one of three types of closely related viruses, flu can come on quickly, with chills, fatigue, headache and body aches. A high fever and severe cough may develop. Flu may be prevented in some cases through a vaccine. However, since the viruses that cause flu change slightly from year to year, a new vaccine is required each flu season. Influenza was responsible for three pandemics (worldwide spread of disease) in the 20th Century alone.

Antibiotics do not kill viruses, and therefore, are not helpful in fighting the common cold or flu. But these diseases can make a person more susceptible to bacterial infections, such as strep throat, a common infection by a Streptococcus bacterium . Symptoms of “strep” infections include sore throat, high fever, coughing, and swollen lymph nodes and tonsils. Diagnosis should be based on the results of a throat swab, which is cultured, and/or a rapid antigen test, which detects foreign substances, known as antigens, in the throat. Strep infections usually can be treated effectively with antibiotics. Without treatment, strep throat can lead to other serious illnesses, such as scarlet fever and rheumatic fever.

Symptoms similar to those of a cold can be caused by allergens in the air. Health experts estimate that 35 million Americans suffer from respiratory allergies, such as hay fever (pollen allergy). An allergy is a reaction of an individual’s disease defense system (immune system) to a substance that does not bother most people. Allergies are not contagious.

Develop descriptions, explanations, predictions and models using evidence.

Think critically and logically to make the relationships between evidence and explanations.

Recognize and analyze alternative explanations and predictions.

Life Science

Disease is a breakdown in structures or functions of an organism. Some diseases are the result of infection by other organisms.

Teacher Materials (see Setup)

90 letter-size plain envelopes

6 sheets of white, self-stick folder labels, 3-7/16 in. x 2/3 in., 30 labels per sheet (Avery™ #5366, 5378 or 8366)

Overhead projector

Overhead transparency of the "Disorders and Symptoms" student sheet

Materials per Group of Students

Set of prepared envelopes (15 envelopes per set)

Copy of "What is Wrong with Allison?" and "Disorders and Symptoms" student sheets (see Lesson pdf)

Group concept map (ongoing)

Photocopy the "What is Wrong with Allison?" and "Disorders and Symptoms" student sheets (one copy of each per student), to be distributed in order (see Procedure).

Photocopy the label template sheet onto six sheets of white, self-stick labels, such as Avery™ #5366, 5378 or 8366, which contain 30 labels per sheet.

Use one page of photocopied labels to create each set of envelopes. Place a "Question" label on the outside of one envelope and stick the corresponding "Clue" label on the inside flap of the same envelope. Close the flap, but do not seal the envelope. Make six sets of 15 envelopes (one set per group).

Make an overhead transparency of the "Disorders and Symptoms" sheet. Have students work in groups of four.

Optional: Instead of using self-stick labels, copy the label template page onto plain paper and cut out each question and clue. Tape one question to the outside of an envelope and the corresponding clue to the inside flap of the envelope.

Begin a class discussion of disease by asking questions such as, How do you know when you are sick? What are some common diseases? Are all diseases alike? Are all diseases caused by a kind of microbe? Do some diseases have similar symptoms?

Tell your students that in this class session, they will be acting as medical personnel trying to diagnose a patient. Give each group a copy of the "What is Wrong with Allison?" sheet. Have one student read the case to the group, and then have groups discuss it. The reporter should record each group’s ideas about what might be wrong with Allison.

Have each student group list four possible questions that a doctor might ask a patient like Allison. Write these questions on the board and discuss with the class.

Have groups identify three possible diseases that Allison may have, based on the story, class discussion and their own experiences.

Give each student a copy of the "Disorders and Symptoms" sheet and briefly introduce the four illnesses to the entire class. Compare these illnesses to the ones that students suggested. Ask, Are there any similarities? Have students follow the instructions on the sheet to complete the exercise.

Give each group of students a set of envelopes. Warn students not to open the envelopes until they are instructed to do so. Tell students that each envelope contains information that a medical doctor might need about a patient. All information is important to the diagnosis, but only certain information will help to distinguish among the four possible respiratory disorders. Instruct students that their task is to decide which envelopes contain information that will help them determine Allison’s illness. Once a group has agreed on question choices, it may open as many envelopes—one at a time—as needed. The challenge is to use as few envelopes as possible to diagnose Allison’s illness. Each group should keep a tally of the number of envelopes opened. Remind students that in real life, a physician would conduct a complete examination and gather all possible information before making a diagnosis.

Allow time for groups to work. Provide assistance to students who may not understand the information contained in the envelopes. If the medicine and body temperature envelopes have been opened, make sure students understand that some medications, like Tylenol™, will mask the presence of mild fevers.

Have each group present its diagnosis and the reasoning used to arrive at its decision. (Allison’s disease is a common cold. If students have arrived at other conclusions, discuss the evidence they used. Mention the challenges of diagnosing respiratory diseases.)

Expand the discussion to address the importance of not taking antibiotics for viral diseases. Ask, Since Allison has a cold, should her doctor prescribe antibiotics? Would it be okay to take leftover antibiotics? Help students understand that antibiotics are effective for bacterial infections, but do not help against viral infections like colds. Also, mention that if antibiotics are prescribed for a bacterial infection, it is important to follow the doctor’s instructions and to take all the medication, even if symptoms start to improve before the medicine is gone. Otherwise, the disease may reoccur. Taking antibiotics incorrectly, or using them inappropriately (such as taking leftover medicine without a doctor’s guidance) can contribute to the development of antibiotic resistant forms of bacteria, which cannot be killed by existing antibiotics.

Have student groups add information to their concept maps.

Related Content

Students explore microbes that impact our health (e.g., bacteria, fungi, protists, and viruses) and learn that microbes play key roles in the lives of humans, sometimes causing disease. (12 activities)

X-Times: Career Options

Student magazine: Special issue featuring healthcare professionals who discuss why each chose his or her career, educational requirements needed to obtain the job, and day-to-day responsibilities.

X-Times: Microbes

Student magazine: articles focusing on microbes, both helpful and harmful. Includes a special report, "HIV/AIDS: The Virus and the Epidemic."

Science Education Partnership Award, NIH

MicroMatters Grant Number: 5R25RR018605

User Tools [+] Expand

User tools [-] collapse.

- You currently have no favorites. You may add some using the "Add to favorites" link below.

- Stored in favorites

- Add to favorites

- Send this Page

- Print this Page

Lessons and More

Join our mailing list.

Stay up to date with news and information from BioEd Online, join our mailing list today!

- Click Here to Subscribe

Need Assistance?

If you need help or have a question please use the links below to help resolve your problem.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Case Studies: Diseases

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 403

Aging (including Alzheimer's disease)

C Rundel, Genes, aging, and the future of longevity. Engineering & Science LXV #4, 12/02, p 36. A delightful essay on some issues of aging, written by a Caltech undergraduate as part of a science writing class -- and then published in the Caltech magazine. The article is available online at http://eands.caltech.edu/articles/LXV4/longevity.html . The article discusses some genes that are known to affect aging in simple model organisms, and even a drug which seems to extend the life of fruit flies.

An intriguing result has recently been published: A team at Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, California) has engineered mice to have a slightly lower core body temperature (by about 0.5 degree Celsius). These mice lived longer (by about 15%) than the "normal" mice. How did they lower the body temperature? By engineering the mice to make a heat-producing protein (uncoupling protein) in the hypothalamus -- where the body senses and regulates its temperature. The cooler mice ate and exercised normally, had somewhat higher weight (since they were producing less heat from the same food) -- and lived longer. Interestingly, one effect of severe caloric restriction, which is known to increase lifespan, is lowering the body temperature. So this work may give us one more piece of a complex puzzle. Its practical significance for now is purely speculative: there is no known way to reduce human body temperature, and of course we know nothing about what the side effects might be. The paper is B Conti et al, Transgenic mice with a reduced core body temperature have an increased life span. Science 314:825, 11/3/06. The paper is accompanied by a "perspective" article: C B Saper, Biomedicine: Life, the universe, and body temperature. Science 314:773, 11/3/06. These are online at http://www.sciencemag.org/content/314/5800/773.summary (perspective, probably the best place to start) and http://www.sciencemag.org/content/314/5800/825.abstract (article).

SAGE KE, the Science of Aging Knowledge Environment Archive Site, from Science magazine. "From October 2001 to June 2006, Science's SAGE KE provided news, reviews, commentaries, disease case studies, databases, and other resources pertaining to aging-related research. Although SAGE KE has now ceased publication, we invite you to search and browse the article content on this archive site." http://sageke.sciencemag.org/ .

Nature web focus sites on aging:

- http://www.nature.com/nm/focus/alzheimer/index.html . Alzheimer's disease. (June 2006)

- http://www.nature.com/nature/focus/s...nce/index.html . Senescence: Cells, ageing and cancer. (August 2005)

- http://www.nature.com/nature/focus/l...pan/index.html . Determining lifespan. (September 2003)

Book. Stephen S Hall, Merchants of Immortality - Chasing the dream of human life extension. Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-618-09524-1. Available in Berkeley Public Library. For more about this book, see the listing of it under Cloning and stem cells . The "aging" parts of the book largely deal with telomerase, a fascinating scientific topic which probably is not a key limiting factor in human aging. In fact, much of the book deals with the hype surrounding telomerase -- and attempts to commercialize telomerase technologies.

Book. Lenny Guarente, Ageless Quest - One scientist's search for genes that prolong youth. Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press, 2003. ISBN 0-87969-652-4. Available in UC Berkeley Library. Guarente is a biologist at MIT. In this short book, he talks about finding a gene that extends the life of simple yeast -- and of worms. The question, then, is whether it is relevant to aging in higher organisms, including humans. He discusses evidence that it may be, though conclusive evidence is not yet available. This story is a good testimonial to the importance of basic research -- how studying simple model systems leads to insights that guide work in more complex systems. It is also a good story of how scientists develop and pursue leads -- some of which work out and some of which do not; that is how science works. It is an optimistic book -- perhaps too optimistic, since the gap between what has been shown and what is needed is still quite large. Enjoy the story, and Guarante's enthusiasm. But be careful to distinguish what turns out to work from the exciting discussions of what might be.

Anthrax vaccine immunization program. One place where the anthrax vaccine is actually used with high frequency is in the US military. This is their site about the vaccine and the program. Be alert for bias (as with any source!), but there is actually a lot of good info here. www.anthrax.osd.mil.

Researchers, including a group from UC Berkeley, have explored the tricks that the anthrax bacteria use to get the iron they need for growth. They found that these bacteria make two chemicals designed to steal iron from their host; such chemicals are generically called siderophores. One of these is attacked by the human immune system; however, the other -- the more novel one -- evades it, and actually succeeds in supplying iron to the bacteria. They suggest that this novel siderophore might be a good target for anti-anthrax drugs, or simply a marker for detection of this pathogen. The work was featured in the student newspaper, December 8, 2006: Researchers Find Possible Way to Block Anthrax, http://archive.dailycal.org/article/22576/_i_science_technology_i_br_researchers_find_possib . It was also discussed in a nice article in the student publication BSR: N Keith, Double Trouble - Anthrax has two tricks for stealing iron. Berkeley Science Review, Issue 12, p 15, Spring 2007. BSR is free online; this item is at sciencereview.berkeley.edu/ar...ticle=briefs_5. The work was published as R J Abergel et al, Anthrax pathogen evades the mammalian immune system through stealth siderophore production. PNAS 103:18499, 12/5/06. Online at http://www.pnas.org/content/103/49/18499.abstract . This work is also briefly noted on my Intro Chem Internet Resources page under solutions .

Book. For some interesting history, see the listing for Thomas D Brock, Robert Koch - A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology (1988) on my page Books: Suggestions for general reading . One major story is the first clear elucidation of the life cycle of a pathogenic bacterium -- anthrax. Those interested in bacteria, especially as agents of disease, will enjoy this fascinating tale of the origins of modern medical microbiology.

Antibiotics

Bacterial 'battle for survival' leads to new antibiotic -- Holds promise for treating stomach ulcers. A press release from MIT, Feb 2008, on a new approach for discovering new antibiotics. Briefly, they force bacteria not known to make antibiotics to compete with other bacteria. One possible response is for them to develop the ability to make antibiotics. This should be considered interesting lab work at this point. The potential of the new antibiotics is unknown. web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2008/a...tics-0226.html.

Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics. www.tufts.edu/med/apua/. This site has "an agenda" -- trying to reduce "inappropriate" use of antibiotics. A particular concern is the use of vast amounts of antibiotics with farm animals, sometimes with minimal justification. The site also contains a lot of general information about antibiotics, aimed at the consumer and at doctors.