Biography Online

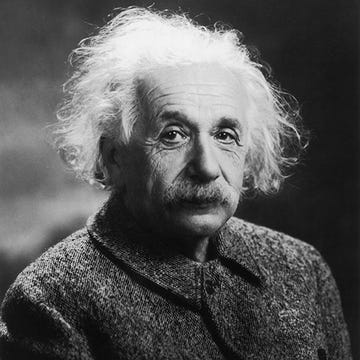

Albert Einstein Biography

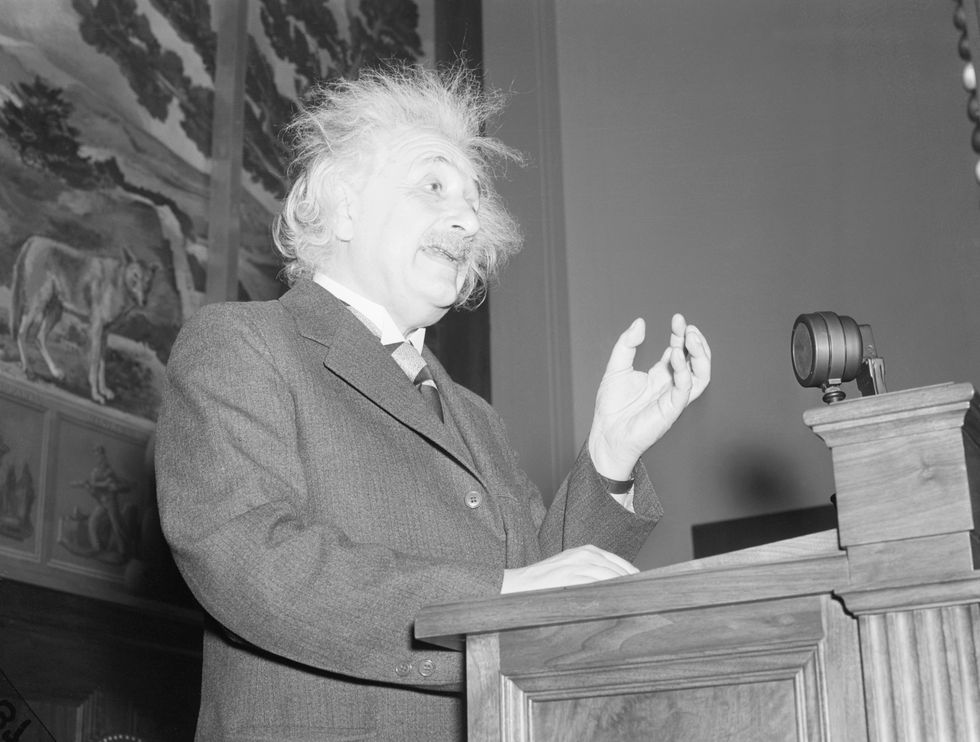

Einstein is also well known as an original free-thinker, speaking on a range of humanitarian and global issues. After contributing to the theoretical development of nuclear physics and encouraging F.D. Roosevelt to start the Manhattan Project, he later spoke out against the use of nuclear weapons.

Born in Germany to Jewish parents, Einstein settled in Switzerland and then, after Hitler’s rise to power, the United States. Einstein was a truly global man and one of the undisputed genius’ of the Twentieth Century.

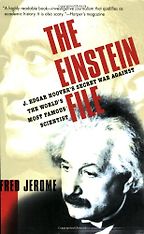

Early life Albert Einstein

Einstein was born 14 March 1879, in Ulm the German Empire. His parents were working-class (salesman/engineer) and non-observant Jews. Aged 15, the family moved to Milan, Italy, where his father hoped Albert would become a mechanical engineer. However, despite Einstein’s intellect and thirst for knowledge, his early academic reports suggested anything but a glittering career in academia. His teachers found him dim and slow to learn. Part of the problem was that Albert expressed no interest in learning languages and the learning by rote that was popular at the time.

“School failed me, and I failed the school. It bored me. The teachers behaved like Feldwebel (sergeants). I wanted to learn what I wanted to know, but they wanted me to learn for the exam.” Einstein and the Poet (1983)

At the age of 12, Einstein picked up a book on geometry and read it cover to cover. – He would later refer to it as his ‘holy booklet’. He became fascinated by maths and taught himself – becoming acquainted with the great scientific discoveries of the age.

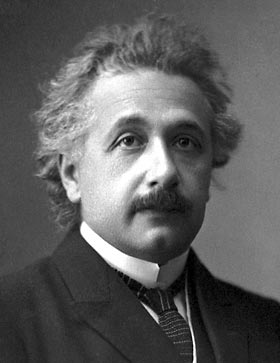

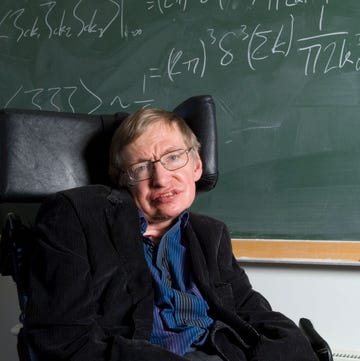

Albert Einstein with wife Elsa

Despite Albert’s independent learning, he languished at school. Eventually, he was asked to leave by the authorities because his indifference was setting a bad example to other students.

He applied for admission to the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. His first attempt was a failure because he failed exams in botany, zoology and languages. However, he passed the next year and in 1900 became a Swiss citizen.

At college, he met a fellow student Mileva Maric, and after a long friendship, they married in 1903; they had two sons before divorcing several years later.

In 1896 Einstein renounced his German citizenship to avoid military conscription. For five years he was stateless, before successfully applying for Swiss citizenship in 1901. After graduating from Zurich college, he attempted to gain a teaching post but none was forthcoming; instead, he gained a job in the Swiss Patent Office.

While working at the Patent Office, Einstein continued his own scientific discoveries and began radical experiments to consider the nature of light and space.

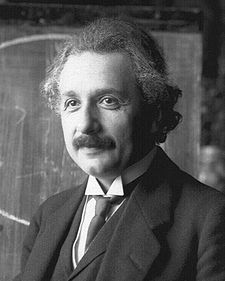

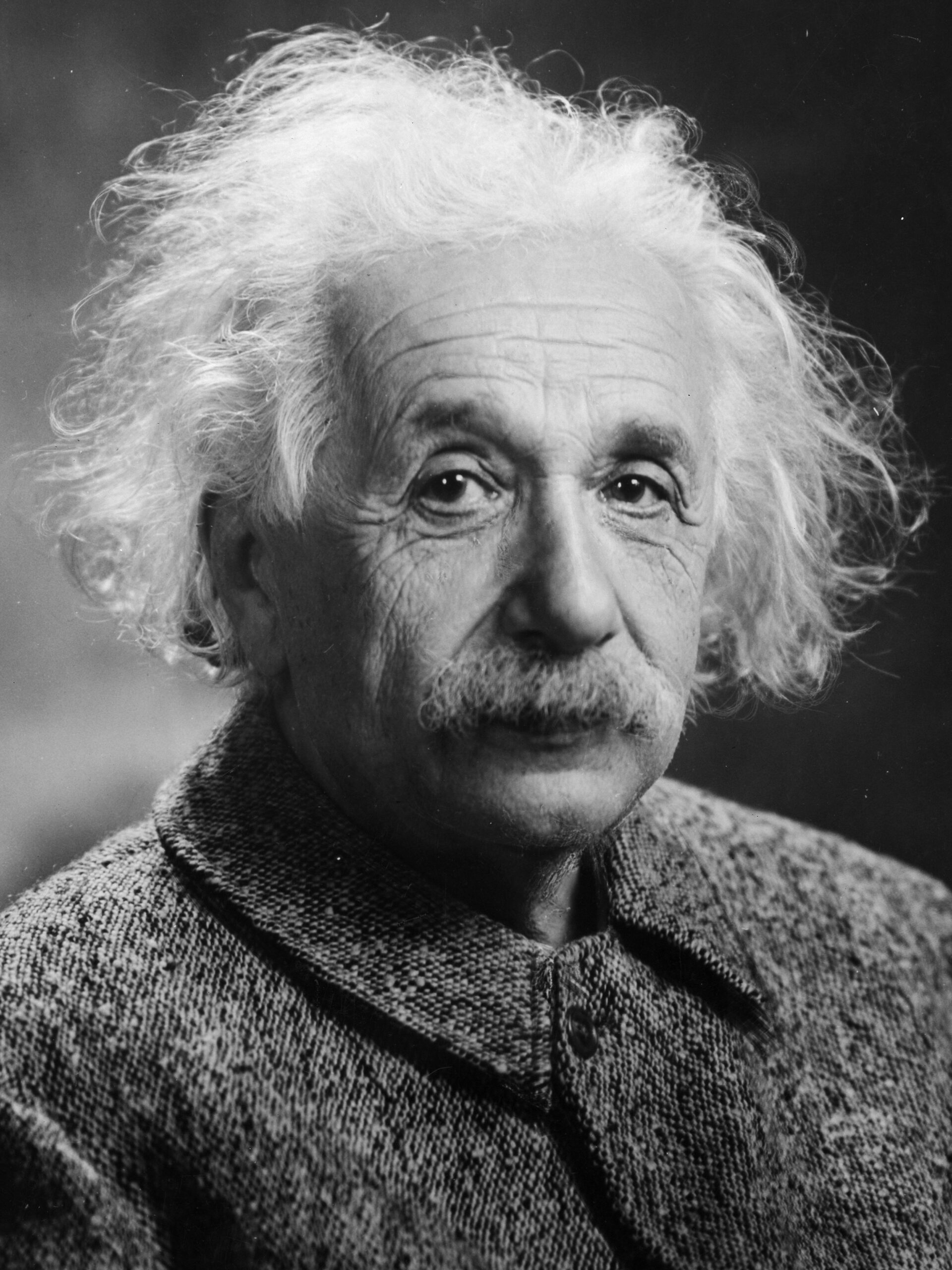

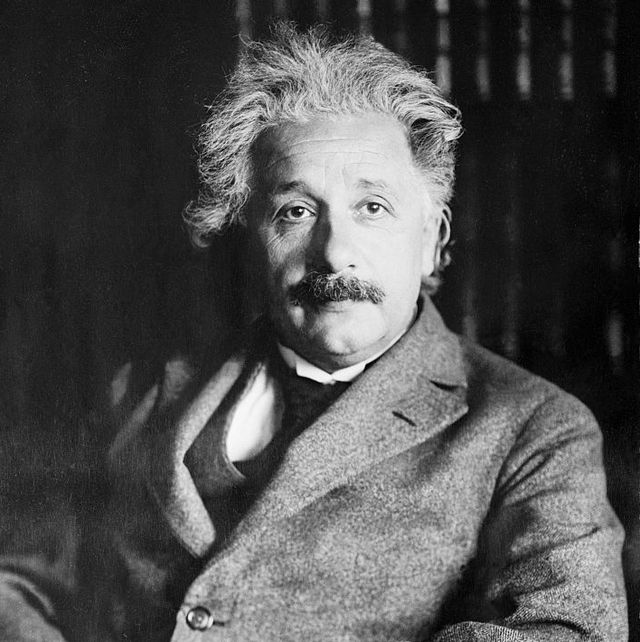

Einstein in 1921

He published his first scientific paper in 1900, and by 1905 had completed his PhD entitled “ A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions . In addition to working on his PhD, Einstein also worked feverishly on other papers. In 1905, he published four pivotal scientific works, which would revolutionise modern physics. 1905 would later be referred to as his ‘ annus mirabilis .’

Einstein’s work started to gain recognition, and he was given a post at the University of Zurich (1909) and, in 1911, was offered the post of full-professor at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague (which was then part of Austria-Hungary Empire). He took Austrian-Hungary citizenship to accept the job. In 1914, he returned to Germany and was appointed a director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics. (1914–1932)

Albert Einstein’s Scientific Contributions

Quantum Theory

Einstein suggested that light doesn’t just travel as waves but as electric currents. This photoelectric effect could force metals to release a tiny stream of particles known as ‘quanta’. From this Quantum Theory, other inventors were able to develop devices such as television and movies. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.

Special Theory of Relativity

This theory was written in a simple style with no footnotes or academic references. The core of his theory of relativity is that:

“Movement can only be detected and measured as relative movement; the change of position of one body in respect to another.”

Thus there is no fixed absolute standard of comparison for judging the motion of the earth or plants. It was revolutionary because previously people had thought time and distance are absolutes. But, Einstein proved this not to be true.

He also said that if electrons travelled at close to the speed of light, their weight would increase.

This lead to Einstein’s famous equation:

Where E = energy m = mass and c = speed of light.

General Theory of Relativity 1916

Working from a basis of special relativity. Einstein sought to express all physical laws using equations based on mathematical equations.

He devoted the last period of his life trying to formulate a final unified field theory which included a rational explanation for electromagnetism. However, he was to be frustrated in searching for this final breakthrough theory.

Solar eclipse of 1919

In 1911, Einstein predicted the sun’s gravity would bend the light of another star. He based this on his new general theory of relativity. On 29 May 1919, during a solar eclipse, British astronomer and physicist Sir Arthur Eddington was able to confirm Einstein’s prediction. The news was published in newspapers around the world, and it made Einstein internationally known as a leading physicist. It was also symbolic of international co-operation between British and German scientists after the horrors of the First World War.

In the 1920s, Einstein travelled around the world – including the UK, US, Japan, Palestine and other countries. Einstein gave lectures to packed audiences and became an internationally recognised figure for his work on physics, but also his wider observations on world affairs.

Bohr-Einstein debates

During the 1920s, other scientists started developing the work of Einstein and coming to different conclusions on Quantum Physics. In 1925 and 1926, Einstein took part in debates with Max Born about the nature of relativity and quantum physics. Although the two disagreed on physics, they shared a mutual admiration.

As a German Jew, Einstein was threatened by the rise of the Nazi party. In 1933, when the Nazi’s seized power, they confiscated Einstein’s property, and later started burning his books. Einstein, then in England, took an offer to go to Princeton University in the US. He later wrote that he never had strong opinions about race and nationality but saw himself as a citizen of the world.

“I do not believe in race as such. Race is a fraud. All modern people are the conglomeration of so many ethnic mixtures that no pure race remains.”

Once in the US, Einstein dedicated himself to a strict discipline of academic study. He would spend no time on maintaining his dress and image. He considered these things ‘inessential’ and meant less time for his research. Einstein was notoriously absent-minded. In his youth, he once left his suitcase at a friends house. His friend’s parents told Einstein’s parents: “ That young man will never amount to anything, because he can’t remember anything.”

Although a bit of a loner, and happy in his own company, he had a good sense of humour. On January 3, 1943, Einstein received a letter from a girl who was having difficulties with mathematics in her studies. Einstein consoled her when he wrote in reply to her letter

“Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics. I can assure you that mine are still greater.”

Einstein professed belief in a God “Who reveals himself in the harmony of all being”. But, he followed no established religion. His view of God sought to establish a harmony between science and religion.

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.”

– Einstein, Science and Religion (1941)

Politics of Einstein

Einstein described himself as a Zionist Socialist. He did support the state of Israel but became concerned about the narrow nationalism of the new state. In 1952, he was offered the position as President of Israel, but he declined saying he had:

“neither the natural ability nor the experience to deal with human beings.” … “I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it.”

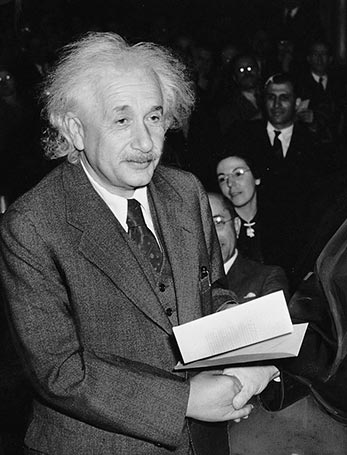

Einstein receiving US citizenship.

Albert Einstein was involved in many civil rights movements such as the American campaign to end lynching. He joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and considered racism, America’s worst disease. But he also spoke highly of the meritocracy in American society and the value of being able to speak freely.

On the outbreak of war in 1939, Einstein wrote to President Roosevelt about the prospect of Germany developing an atomic bomb. He warned Roosevelt that the Germans were working on a bomb with a devastating potential. Roosevelt headed his advice and started the Manhattan project to develop the US atom bomb. But, after the war ended, Einstein reverted to his pacifist views. Einstein said after the war.

“Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I would not have lifted a finger.” (Newsweek, 10 March 1947)

In the post-war McCarthyite era, Einstein was scrutinised closely for potential Communist links. He wrote an article in favour of socialism, “Why Socialism” (1949) He criticised Capitalism and suggested a democratic socialist alternative. He was also a strong critic of the arms race. Einstein remarked:

“I do not know how the third World War will be fought, but I can tell you what they will use in the Fourth—rocks!”

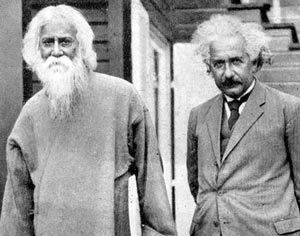

Rabindranath Tagore and Einstein

Einstein was feted as a scientist, but he was a polymath with interests in many fields. In particular, he loved music. He wrote that if he had not been a scientist, he would have been a musician. Einstein played the violin to a high standard.

“I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music… I get most joy in life out of music.”

Einstein died in 1955, at his request his brain and vital organs were removed for scientific study.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Albert Einstein ”, Oxford, www.biographyonline.net 23 Feb. 2008. Updated 2nd March 2017.

Albert Einstein – His Life and Universe

Albert Einstein – His Life at Amazon

Related pages

53 Interesting and unusual facts about Albert Einstein.

19 Comments

Albert E is awesome! Thanks for this website!!

- January 11, 2019 3:00 PM

Albert Einstein is the best scientist ever! He shall live forever!

- January 10, 2019 4:11 PM

very inspiring

- December 23, 2018 8:06 PM

Wow it is good

- December 08, 2018 10:14 AM

Thank u Albert for discovering all this and all the wonderful things u did!!!!

- November 15, 2018 7:03 PM

- By Madalyn Silva

Thank you so much, This biography really motivates me a lot. and I Have started to copy of Sir Albert Einstein’s habit.

- November 02, 2018 3:37 PM

- By Ankit Gupta

Sooo inspiring thanks Albert E. You helped me in my report in school I love you Albert E. 🙂 <3

- October 17, 2018 4:39 PM

- By brooklynn

By this inspired has been I !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- October 12, 2018 4:25 PM

- By Richard Clarlk

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Albert Einstein

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 16, 2019 | Original: October 27, 2009

The German-born physicist Albert Einstein developed the first of his groundbreaking theories while working as a clerk in the Swiss patent office in Bern. After making his name with four scientific articles published in 1905, he went on to win worldwide fame for his general theory of relativity and a Nobel Prize in 1921 for his explanation of the phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect. An outspoken pacifist who was publicly identified with the Zionist movement, Einstein emigrated from Germany to the United States when the Nazis took power before World War II. He lived and worked in Princeton, New Jersey, for the remainder of his life.

Einstein’s Early Life (1879-1904)

Born on March 14, 1879, in the southern German city of Ulm, Albert Einstein grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Munich. As a child, Einstein became fascinated by music (he played the violin), mathematics and science. He dropped out of school in 1894 and moved to Switzerland, where he resumed his schooling and later gained admission to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich. In 1896, he renounced his German citizenship, and remained officially stateless before becoming a Swiss citizen in 1901.

Did you know? Almost immediately after Albert Einstein learned of the atomic bomb's use in Japan, he became an advocate for nuclear disarmament. He formed the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists and backed Manhattan Project scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer in his opposition to the hydrogen bomb.

While at Zurich Polytechnic, Einstein fell in love with his fellow student Mileva Maric, but his parents opposed the match and he lacked the money to marry. The couple had an illegitimate daughter, Lieserl, born in early 1902, of whom little is known. After finding a position as a clerk at the Swiss patent office in Bern, Einstein married Maric in 1903; they would have two more children, Hans Albert (born 1904) and Eduard (born 1910).

Einstein’s Miracle Year (1905)

While working at the patent office, Einstein did some of the most creative work of his life, producing no fewer than four groundbreaking articles in 1905 alone. In the first paper, he applied the quantum theory (developed by German physicist Max Planck) to light in order to explain the phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect, by which a material will emit electrically charged particles when hit by light. The second article contained Einstein’s experimental proof of the existence of atoms, which he got by analyzing the phenomenon of Brownian motion, in which tiny particles were suspended in water.

In the third and most famous article, titled “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” Einstein confronted the apparent contradiction between two principal theories of physics: Isaac Newton’s concepts of absolute space and time and James Clerk Maxwell’s idea that the speed of light was a constant. To do this, Einstein introduced his special theory of relativity, which held that the laws of physics are the same even for objects moving in different inertial frames (i.e. at constant speeds relative to each other), and that the speed of light is a constant in all inertial frames. A fourth paper concerned the fundamental relationship between mass and energy, concepts viewed previously as completely separate. Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2 (where “c” was the constant speed of light) expressed this relationship.

From Zurich to Berlin (1906-1932)

Einstein continued working at the patent office until 1909, when he finally found a full-time academic post at the University of Zurich. In 1913, he arrived at the University of Berlin, where he was made director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics. The move coincided with the beginning of Einstein’s romantic relationship with a cousin of his, Elsa Lowenthal, whom he would eventually marry after divorcing Mileva. In 1915, Einstein published the general theory of relativity, which he considered his masterwork. This theory found that gravity, as well as motion, can affect time and space. According to Einstein’s equivalence principle–which held that gravity’s pull in one direction is equivalent to an acceleration of speed in the opposite direction–if light is bent by acceleration, it must also be bent by gravity. In 1919, two expeditions sent to perform experiments during a solar eclipse found that light rays from distant stars were deflected or bent by the gravity of the sun in just the way Einstein had predicted.

The general theory of relativity was the first major theory of gravity since Newton’s, more than 250 years before, and the results made a tremendous splash worldwide, with the London Times proclaiming a “Revolution in Science” and a “New Theory of the Universe.” Einstein began touring the world, speaking in front of crowds of thousands in the United States, Britain, France and Japan. In 1921, he won the Nobel Prize for his work on the photoelectric effect, as his work on relativity remained controversial at the time. Einstein soon began building on his theories to form a new science of cosmology, which held that the universe was dynamic instead of static, and was capable of expanding and contracting.

Einstein Moves to the United States (1933-39)

A longtime pacifist and a Jew, Einstein became the target of hostility in Weimar Germany, where many citizens were suffering plummeting economic fortunes in the aftermath of defeat in the Great War. In December 1932, a month before Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Einstein made the decision to emigrate to the United States, where he took a position at the newly founded Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey . He would never again enter the country of his birth.

By the time Einstein’s wife Elsa died in 1936, he had been involved for more than a decade with his efforts to find a unified field theory, which would incorporate all the laws of the universe, and those of physics, into a single framework. In the process, Einstein became increasingly isolated from many of his colleagues, who were focused mainly on the quantum theory and its implications, rather than on relativity.

Einstein’s Later Life (1939-1955)

In the late 1930s, Einstein’s theories, including his equation E=mc2, helped form the basis of the development of the atomic bomb. In 1939, at the urging of the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, Einstein wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt advising him to approve funding for the development of uranium before Germany could gain the upper hand. Einstein, who became a U.S. citizen in 1940 but retained his Swiss citizenship, was never asked to participate in the resulting Manhattan Project , as the U.S. government suspected his socialist and pacifist views. In 1952, Einstein declined an offer extended by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s premier, to become president of Israel .

Throughout the last years of his life, Einstein continued his quest for a unified field theory. Though he published an article on the theory in Scientific American in 1950, it remained unfinished when he died, of an aortic aneurysm, five years later. In the decades following his death, Einstein’s reputation and stature in the world of physics only grew, as physicists began to unravel the mystery of the so-called “strong force” (the missing piece of his unified field theory) and space satellites further verified the principles of his cosmology.

HISTORY Vault: Secrets of Einstein's Brain

Originally stolen by the doctor trusted to perform his autopsy, scientists over the decades have examined the brain of Albert Einstein to try and determine what made this seemingly normal man tick.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Einstein : his life and universe

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Cut-off text on some pages due to tight binding

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

13 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station23.cebu on October 16, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Culture History

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was a renowned theoretical physicist, best known for developing the theory of relativity, which revolutionized our understanding of space, time, and gravity. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. Einstein’s work laid the foundation for many advancements in modern physics.

Early Life and Education

Albert Einstein’s early life and education laid the foundation for a revolutionary career in physics. Born on March 14, 1879, in the city of Ulm in the Kingdom of Württemberg, which was part of the German Empire, Einstein was the first child of Hermann and Pauline Einstein. His father, a salesman and engineer, and his mother, a homemaker, provided a modest yet supportive environment for their son’s intellectual development.

Einstein’s early years were marked by curiosity and a fascination with the mysteries of the natural world. He showed an early interest in mathematics and began to explore the subject on his own. The family’s move to Munich in 1880 coincided with the start of Einstein’s formal education. At the age of six, he entered the Luitpold Gymnasium, a Catholic elementary school, where his unconventional behavior and independent thinking sometimes clashed with the traditional educational methods.

Einstein’s teachers noted his exceptional mathematical abilities, but his rebellious spirit and refusal to conform to authority created a challenging academic environment. Frustrated by the rigid structure of the school, Einstein often clashed with his teachers, earning a reputation as a nonconformist. His dissatisfaction with the educational system ultimately led his parents to consider removing him from the Gymnasium.

In 1889, Einstein’s family faced a significant change with the relocation to Italy due to financial challenges. While his parents and sister settled in Pavia, Albert remained in Munich to complete his education. At the age of 15, Einstein applied to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, seeking admission to the prestigious institution. Despite excelling in mathematics and physics, he failed the entrance exam, and his application was rejected.

Undeterred, Einstein enrolled in the Swiss Cantonal School in Aarau, Switzerland, to complete his secondary education. Under the guidance of Jost Winteler, a supportive and understanding teacher, Einstein thrived in this new environment. He immersed himself in his studies, delving into advanced topics in mathematics and physics. It was during this period that Einstein developed a deep appreciation for the works of classical physicists, including Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell .

In 1896, Einstein graduated from the Swiss Cantonal School with excellent grades, earning his diploma. His success paved the way for his acceptance into the ETH Zurich, where he pursued his passion for physics. Einstein’s time at the ETH marked a crucial phase in his intellectual development. He studied under renowned physicists such as Heinrich Friedrich Weber and Hermann Minkowski, delving into the latest advancements in theoretical physics.

While at the ETH, Einstein faced financial challenges, often struggling to make ends meet. He earned money by tutoring classmates and discovered a passion for teaching. Despite the financial hardships, his dedication to his studies remained unwavering. In 1900, Einstein graduated from the ETH with a teaching diploma in physics and mathematics.

After completing his formal education, Einstein faced the challenge of entering the professional world. His initial attempts to secure a university position were unsuccessful, leading him to accept a position as a technical assistant at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern in 1902. The patent office provided a stable income for Einstein, allowing him to marry Mileva Maric, a fellow student from the ETH, in 1903. The couple had two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard.

While working at the patent office, Einstein continued to explore his scientific interests during his free time. He published several scientific papers, including his groundbreaking work on the photoelectric effect in 1905, which laid the foundation for the concept of photons and earned him a Ph.D. from the University of Zurich. This period, often referred to as Einstein’s “miracle year,” saw the publication of four influential papers that had a profound impact on various branches of physics.

Einstein’s success in 1905 marked a turning point in his career. Recognizing his contributions, the scientific community began to take notice of the young physicist. In 1908, he was appointed as a lecturer at the University of Bern. This marked the beginning of his transition from the patent office to an academic career.

As Einstein’s reputation grew, so did his opportunities. In 1911, he accepted a position as a professor at the German University in Prague. His time in Prague was productive, leading to further advancements in his theoretical work. However, in 1912, he returned to Switzerland, accepting a position at the ETH Zurich, where he had once been a student.

Einstein’s journey from a rebellious schoolboy in Munich to a renowned physicist at the ETH Zurich showcased not only his intellectual prowess but also his resilience in the face of challenges. His early life and education set the stage for the remarkable scientific contributions that would follow, forever changing our understanding of the universe.

Special Theory of Relativity

Albert Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, published in 1905, stands as one of the most revolutionary achievements in the history of physics . Building on the foundation laid by Isaac Newton’s classical mechanics, Einstein’s theory introduced profound changes to our understanding of space, time, and the nature of the universe.

At the heart of the Special Theory of Relativity is the principle of relativity itself. Einstein proposed that the laws of physics are the same for all observers in uniform motion, regardless of their relative velocities. This concept challenged the classical notion of absolute space and time, as described by Newtonian physics. Instead, Einstein proposed a new framework in which the laws of physics are consistent for all observers, regardless of their state of motion.

One of the most iconic consequences of the theory is the equivalence of mass and energy, expressed by the famous equation E=mc². This equation states that energy (E) is proportional to mass (m) and is equivalent to the speed of light (c) squared. The realization that mass could be converted into energy and vice versa had profound implications for our understanding of the physical world. It laid the groundwork for advancements in nuclear physics and played a crucial role in the development of nuclear energy.

The theory also introduced a novel perspective on space and time, merging them into a single entity known as spacetime. According to Special Relativity, space and time are interconnected, and the fabric of spacetime can be curved by the presence of mass and energy. This concept set the stage for Einstein’s later development of the General Theory of Relativity, which extended the principles of Special Relativity to include gravity.

One of the key postulates of Special Relativity is the constancy of the speed of light in a vacuum. Einstein proposed that the speed of light is the same for all observers, regardless of their relative motion. This departure from classical physics was experimentally confirmed by the famous Michelson-Morley experiment, which aimed to detect variations in the speed of light due to the Earth’s motion through space. The experiment’s results supported Einstein’s theory and led to a fundamental shift in our understanding of the nature of light and motion.

Special Relativity also introduced the concept of time dilation, a phenomenon in which time appears to pass more slowly for an observer in motion relative to a stationary observer. This effect becomes significant at speeds approaching the speed of light and has been experimentally verified through measurements of particles moving at high velocities.

Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity not only reshaped the foundations of physics but also had broader implications for philosophy and our conception of reality. It challenged classical notions of absolute space and time, paving the way for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamic relationship between matter, energy, space, and time.

The profound impact of Special Relativity continues to be felt today. Its principles are integrated into the framework of modern physics, influencing a wide range of scientific disciplines, from particle physics to cosmology. Einstein’s ability to question fundamental assumptions and propose groundbreaking ideas in 1905 has left an enduring legacy, shaping the trajectory of scientific inquiry and expanding our comprehension of the universe.

Nobel Prize in Physics (1921)

Albert Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921, marking a significant recognition of his groundbreaking contributions to theoretical physics. However, the circumstances surrounding the prize and its specific focus highlight the complex relationship between Einstein and the scientific establishment of the time.

The Nobel Prize in Physics for 1921 was awarded to Albert Einstein “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.” The photoelectric effect, a phenomenon where light falling on a material surface ejects electrons from it, had been a subject of scientific inquiry for many years. Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect, published in 1905, provided a theoretical framework that not only explained the experimental observations but also laid the foundation for the concept of photons—particles of light.

Einstein’s explanation of the photoelectric effect departed from classical wave theory, proposing that light is quantized and composed of discrete packets of energy, or quanta. Each quantum of light (later termed a photon) carries energy proportional to its frequency. This groundbreaking idea, combined with his equation E=hf (where E is energy, h is Planck’s constant, and f is frequency), revolutionized the understanding of light and paved the way for the development of quantum theory.

The choice of the photoelectric effect for the Nobel Prize was not without controversy. At the time, Einstein’s theories were still gaining acceptance within the scientific community. Some physicists, notably Max Planck , had embraced the quantum nature of light, but others were hesitant to fully embrace these revolutionary ideas. The Nobel Committee’s decision to recognize Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect rather than his more famous theories of special and general relativity reflected a certain caution within the scientific establishment.

Einstein himself had reservations about the Nobel Committee’s choice. In his acceptance speech, he acknowledged the award but expressed his hope that future Nobel Prizes would be awarded for achievements in relativity theory. The decision to focus on the photoelectric effect instead of relativity may have been influenced by a desire to avoid controversies surrounding the acceptance of the more radical aspects of Einstein’s work at that time.

The recognition of the photoelectric effect in 1921 marked a turning point in Einstein’s relationship with the scientific community. While he had faced skepticism and resistance to his ideas, the Nobel Prize provided a measure of validation for his contributions to theoretical physics. It also brought him greater visibility on the international stage.

The impact of Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect extended far beyond the Nobel Prize. The development of quantum theory, influenced by his ideas, became a cornerstone of modern physics. The photoelectric effect played a crucial role in the experimental verification of quantum principles, providing empirical support for the concept of quantized energy levels.

Emigration to the United States

Albert Einstein’s emigration to the United States in 1933 marked a significant chapter in his life, shaped by a combination of personal and political factors. Fleeing the rising Nazi regime in Germany, Einstein sought refuge in America, where he would continue his scientific work, contribute to academia, and become an influential public figure.

As Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Party gained power in Germany, Einstein, who was of Jewish heritage and known for his outspoken views, became a target of increasing persecution. The Nazi regime’s anti-Semitic policies and restrictions on intellectuals compelled Einstein to reassess his situation. His opposition to authoritarianism, coupled with concerns for his safety, prompted him to make the difficult decision to leave his homeland.

In March 1933, Einstein and his wife, Elsa, left Germany for Belgium, where they briefly resided before continuing to the United States. At the time, Einstein was a professor at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin. The decision to abandon his position and the academic environment he had contributed to for many years underscored the urgency and gravity of the situation.

Einstein’s emigration to the United States was facilitated by the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey. In 1932, he had accepted an offer to join the IAS as a resident professor, which provided him with an academic home and a haven from the political turmoil in Europe. The IAS, founded by philanthropists Louis Bamberger and Caroline Bamberger Fuld, became a refuge for scholars fleeing persecution.

Upon arriving in the United States, Einstein settled into his new role at the IAS and began an era of scientific productivity. He continued his theoretical work, collaborating with other prominent physicists at the institute. Princeton offered him not only a sanctuary from political unrest but also a vibrant intellectual community that fueled his scientific endeavors.

Einstein’s presence in the United States also had a profound impact on the American scientific landscape. He became a sought-after figure in both academic and public circles, lending his support to various causes. His emigration coincided with the increasing awareness of the threat posed by fascist ideologies, and Einstein’s advocacy for democracy, pacifism, and civil rights resonated with many.

In addition to his scientific pursuits, Einstein embraced a more public role in American society. He became involved in political and social issues, speaking out against racism and discrimination. Einstein’s commitment to civil rights was reflected in his association with the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), where he collaborated with activists such as W.E.B. Du Bois. His support for Zionism and the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine also became part of his public discourse.

Einstein’s emigration to the United States not only allowed him to escape the immediate dangers of Nazi persecution but also provided him with a platform to influence the course of history. His contributions extended beyond the realm of theoretical physics to encompass broader issues of social justice, human rights, and global peace.

The United States, in turn, benefited greatly from Einstein’s presence. His work at the IAS and his engagement with American society left an indelible mark, contributing to the country’s scientific and cultural landscape. Einstein’s emigration underscored the complex interplay between personal circumstances, political upheaval, and the enduring impact of a brilliant mind on the world stage.

World War II and Manhattan Project

World War II and the Manhattan Project represent a crucial period in the life of Albert Einstein and his indirect involvement in the development of nuclear weapons. While Einstein did not directly participate in the Manhattan Project, his contributions to the field of theoretical physics laid the groundwork for the scientific understanding that made the project possible.

As World War II unfolded, the scientific community became increasingly aware of the potential for harnessing atomic energy for destructive purposes. In 1939, physicists Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner, both refugees from Europe, approached Einstein with concerns about the possibility of Nazi Germany developing atomic weapons. Recognizing the grave implications, they urged Einstein to write a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, urging the United States to initiate its own atomic research.

Einstein, along with physicist Leó Szilárd, drafted a letter to President Roosevelt in August 1939. This letter emphasized the theoretical possibility of atomic bombs and the urgency of American efforts to develop this technology. Einstein’s prestige and global reputation lent significant weight to the appeal. This letter, often referred to as the Einstein-Szilárd letter, played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Manhattan Project.

The Manhattan Project, officially initiated in 1942, was a top-secret research and development project aimed at producing nuclear weapons. The project brought together some of the world’s leading physicists, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, and Richard Feynman, to work on the complexities of nuclear fission and the construction of atomic bombs.

Despite his initial advocacy for nuclear research in the face of Nazi threats, Einstein did not play a direct role in the Manhattan Project. The U.S. government, considering him a security risk due to his outspoken political views and associations with leftist causes, did not involve him in the classified research efforts. Instead, Einstein continued his academic work at Princeton and remained on the periphery of the project.

Einstein’s indirect involvement in the Manhattan Project became a source of internal conflict for him. While he initially supported the idea of nuclear research as a deterrent against Nazi aggression, he later became increasingly uneasy about the destructive potential of atomic weapons. Einstein’s commitment to pacifism and his desire for global disarmament clashed with the realization that the very scientific principles he had helped establish were being used to create immensely powerful and destructive weapons.

Following the successful test of the first atomic bomb in July 1945, Einstein’s concerns deepened. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, which played a decisive role in ending World War II, further fueled his unease. Einstein, grappling with the ethical implications of his earlier involvement, became an advocate for peace and disarmament in the post-war era.

Einstein’s reflections on the consequences of atomic weapons were encapsulated in his famous remark: “The release of atomic energy has not created a new problem. It has merely made more urgent the necessity of solving an existing one.” In the aftermath of World War II, Einstein devoted considerable effort to promoting nuclear disarmament and advocating for peaceful coexistence.

The juxtaposition of Einstein’s early support for atomic research, driven by fears of Nazi Germany, and his later advocacy for disarmament underscored the moral dilemmas associated with scientific advancements during times of war. While Einstein’s scientific contributions were instrumental in shaping the theoretical foundations of the atomic bomb, his later reflections reflected a deep concern for the ethical implications of the use of nuclear weapons and the imperative of preventing their catastrophic consequences.

Civil Rights Advocacy

Albert Einstein’s advocacy for civil rights in the United States was a defining aspect of his public persona during the mid-20th century. Emigrating to the U.S. in 1933 to escape Nazi persecution, Einstein, who was of Jewish heritage, became increasingly aware of racial injustice and discrimination prevalent in his new homeland. Throughout his life, he used his platform and influence to champion civil rights, leaving a lasting impact on the struggle for racial equality.

Einstein’s engagement with civil rights issues can be traced back to the 1930s when he became increasingly disturbed by the racial segregation and discrimination faced by African Americans. His experiences with racism in the United States, combined with his commitment to principles of justice and equality, prompted him to take a stand against racial injustice.

In 1937, Einstein accepted an invitation to join the American Crusade to End Lynching, a campaign aimed at raising awareness and mobilizing public opinion against the horrific practice of racial violence in the form of lynchings. Einstein’s involvement brought attention to the cause and underscored the need for collective action to combat racial hatred.

As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s, Einstein’s commitment to the cause deepened. He developed a friendship and collaboration with prominent African American civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois, supporting the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and contributing financially to the organization’s efforts to fight racial discrimination.

Einstein’s association with the NAACP included serving on the board of directors and using his influential voice to advocate for equal rights. He spoke out against segregation and racial discrimination, emphasizing the importance of addressing systemic inequalities. Einstein believed that racism was not only a moral injustice but also an impediment to the progress and unity of the nation.

One of Einstein’s notable contributions to the civil rights movement was his critique of segregation in the southern United States. In 1946, he delivered a commencement address at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, becoming the first white person to receive an honorary degree from the historically Black university. In his speech, Einstein condemned racial segregation, calling it a “disease of white people,” and expressed his hope for a future of racial harmony.

Einstein’s commitment to civil rights extended beyond public statements. He corresponded with political leaders and engaged in dialogue with fellow intellectuals on the need for social change. In 1948, he wrote a letter to the then-President of the United States, Harry S. Truman, urging him to take a stand against racism and lynching.

While Einstein’s involvement in civil rights advocacy was primarily focused on racial issues, he also expressed concern for broader social justice causes. He was an advocate for pacifism, disarmament, and international cooperation, reflecting his deep commitment to building a more just and peaceful world.

Albert Einstein’s legacy as a civil rights advocate transcends his contributions to science. His willingness to use his platform to challenge racial injustice demonstrated the power of prominent figures to influence societal attitudes and policies. Einstein’s commitment to civil rights continues to inspire those who recognize the importance of using one’s influence to combat discrimination and promote equality in all its forms.

Personal Life and Family

Albert Einstein’s personal life and family played a significant role in shaping the experiences and perspectives of one of the most iconic figures in the history of science. Beyond his groundbreaking work in theoretical physics, Einstein’s relationships, marriages, and family dynamics offer glimpses into the private life of a complex and multifaceted individual.

Einstein’s first marriage was to Mileva Maric, a fellow student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. The couple married in 1903 and had two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard. Mileva, herself a physicist, collaborated with Einstein on scientific work during the early years of their marriage. However, the relationship faced challenges, both personal and professional. The demands of Einstein’s career and the strain of a troubled marriage eventually led to their separation in 1914 and divorce in 1919.

Einstein’s relationship with his two sons was marked by the complexities of his professional commitments and the upheavals of the time. Hans Albert, the elder son, pursued a career in hydraulic engineering. Eduard, the younger son, faced mental health challenges, and his struggles had a profound impact on the family. Einstein, despite his global fame and intellectual pursuits, navigated the intricate balance between his public life and personal responsibilities.

In 1919, the same year as his divorce from Mileva, Einstein remarried. His second wife was Elsa Löwenthal, a cousin on his maternal side. Elsa, a widow with two daughters, brought her own family into the union. This second marriage provided Einstein with a supportive companion who understood the challenges and demands of his life. Elsa, instrumental in managing Einstein’s affairs and social engagements, provided stability and support throughout their marriage.

The Einstein-Löwenthal household became a blended family, with Albert and Elsa navigating the complexities of raising a stepdaughter, Ilse, and a stepson, Margot. The dynamics of this extended family reflected Einstein’s ability to adapt to evolving personal circumstances. Elsa, often described as Einstein’s anchor, played a vital role in maintaining a harmonious domestic environment.

While Einstein’s professional life soared to new heights, his personal life faced additional challenges. Eduard, his younger son, struggled with mental health issues, eventually leading to his institutionalization. This period marked a difficult chapter for the family, and Einstein, despite his brilliance in physics, grappled with the complexities of mental health within his own household.

The family faced further trials with the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany. Einstein’s Jewish heritage and outspoken views made him a target for persecution. Fearing for their safety, the Einstein family emigrated to the United States in 1933. This move marked a significant transition in their lives, as they sought refuge from the political turmoil in Europe.

In the United States, Einstein’s family life continued to evolve. Elsa passed away in 1936, leaving Einstein to navigate the challenges of his personal and professional life as a widower. Despite personal losses and the global upheaval of World War II, Einstein’s commitment to scientific inquiry and advocacy for peace remained steadfast.

Albert Einstein’s personal life, marked by the complexities of family dynamics, relationships, and personal challenges, adds depth to our understanding of this towering figure in the world of science. His ability to balance the demands of a tumultuous personal life with his groundbreaking scientific contributions reflects the intricate interplay between the private and public dimensions of his extraordinary existence.

Unified Field Theory

Albert Einstein’s pursuit of a Unified Field Theory (UFT) was a lifelong scientific endeavor aimed at unifying the fundamental forces of nature into a single, comprehensive framework. This ambitious quest consumed much of Einstein’s later career, as he sought to reconcile the principles of general relativity and electromagnetism, ultimately aiming for a unified description of the gravitational and electromagnetic forces.

Einstein’s interest in unifying the forces of nature was sparked by the success of his earlier theories. In 1915, he had formulated the General Theory of Relativity, which provided a groundbreaking understanding of gravity as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. This theory successfully explained gravitational phenomena on large scales, such as the motion of planets and the bending of light around massive objects.

However, as quantum mechanics emerged in the early 20th century, describing the behavior of particles on very small scales, a tension arose between Einstein’s theory of gravity and the quantum framework. Quantum mechanics, which successfully explained the behavior of subatomic particles, relied on probabilistic principles and seemed incompatible with the determinism inherent in Einstein’s general relativity.

Einstein’s initial attempts at unification focused on incorporating electromagnetism into his gravitational framework. In the 1920s, he collaborated with mathematician Theodor Kaluza, who proposed a five-dimensional extension of general relativity that included electromagnetism. This Kaluza-Klein theory, while elegant in its mathematical formulation, did not gain widespread acceptance during Einstein’s lifetime.

Einstein’s pursuit of a unified theory gained momentum in the 1930s and 1940s, particularly after the discovery of nuclear forces. His vision extended beyond gravity and electromagnetism to include the strong and weak nuclear forces, seeking a theory that could encompass all fundamental interactions in a single, elegant framework.

One of Einstein’s notable attempts was the Einstein-Cartan theory, developed in collaboration with mathematician Élie Cartan. This theory incorporated torsion—a measure of twisting or distortion in spacetime—into the gravitational field equations. While intriguing, this theory did not achieve the desired unification and faced challenges in reconciling with experimental observations.

Einstein’s last major attempt at a unified theory was the development of the “unified field theory of gravitation and electricity” in the 1950s. Collaborating with physicist Walther Mayer, Einstein sought a theory that could describe both gravitational and electromagnetic phenomena. However, the challenges of combining quantum principles with general relativity persisted, and the theory remained incomplete.

Despite the lack of success in formulating a complete Unified Field Theory, Einstein’s contributions to the pursuit of unification had a lasting impact. His efforts inspired subsequent generations of physicists to explore new avenues for understanding the fundamental forces of nature. The quest for a unified theory continues today, with ongoing research in areas such as string theory and quantum gravity.

Einstein’s vision for a unified theory reflected his deep conviction in the elegance and simplicity of the laws governing the universe. While he did not achieve the ultimate goal of unification during his lifetime, his legacy as a pioneer in the quest for a unified understanding of nature endures, challenging scientists to explore the frontiers of theoretical physics in pursuit of a comprehensive theory that encompasses all fundamental forces.

Political Activism

Albert Einstein’s political activism was a prominent and impactful facet of his public life, reflecting his commitment to social justice, pacifism, and human rights. Throughout the turbulent events of the 20th century, Einstein used his fame and influence to address pressing political and moral issues, leaving a lasting legacy as a global advocate for peace and equality.

Einstein’s political engagement was sparked by the rise of fascism in Europe during the 1920s and 1930s. As Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party gained power in Germany, Einstein, who was of Jewish heritage and known for his progressive views, became a target for persecution. Faced with the threat of anti-Semitic oppression, Einstein emigrated to the United States in 1933, seeking refuge from the political turmoil in Europe.

In his new homeland, Einstein embraced his role as a public intellectual and began to speak out on a range of political issues. He became an outspoken critic of fascism, totalitarianism, and militarism. Einstein’s early anti-war stance was evident in his involvement with the anti-war movement during World War I, but it gained renewed urgency as the world descended into the chaos of World War II.

Einstein’s commitment to pacifism, however, faced a complex dilemma with the outbreak of World War II and the rise of the Nazi regime. While he advocated for peaceful solutions to conflicts, he recognized the threat posed by Hitler and the necessity of confronting fascist aggression. Einstein supported the Allied war effort against Nazi Germany and actively collaborated with other scientists on projects related to military defense, such as the development of radar technology.

Following World War II, Einstein’s focus shifted toward broader issues of peace, disarmament, and international cooperation. He played a central role in the formation of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, an organization that sought to promote nuclear disarmament and prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Einstein’s concerns about the devastating consequences of atomic warfare led him to become a prominent advocate for global peace.

In 1946, Einstein delivered a powerful commencement address at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, addressing the moral implications of science and technology. He emphasized the responsibility of scientists to use their knowledge for the benefit of humanity, stressing the importance of ethics and social responsibility in scientific pursuits.

Einstein’s involvement with political causes extended beyond the realm of science. He became an active supporter of civil rights in the United States, using his influence to speak out against racial segregation and discrimination. Einstein joined the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and collaborated with civil rights leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois. His commitment to civil rights was reflected in his advocacy for racial equality and his critique of racism as a disease that afflicted white society.

In the realm of international affairs, Einstein supported the establishment of the United Nations and became an advocate for global governance and diplomacy. He recognized the need for collective efforts to address global challenges and prevent future conflicts. Einstein’s engagement with political issues underscored his belief in the interconnectedness of humanity and the importance of fostering a just and harmonious world.

Albert Einstein’s political activism, marked by his courageous stand against fascism, commitment to pacifism, and advocacy for civil rights, demonstrated the power of intellectual influence in shaping public discourse and promoting social change. His legacy as a principled advocate for peace and justice continues to inspire those who recognize the moral responsibility of individuals, particularly those with influence, to contribute to the betterment of society.

Legacy and Impact

Albert Einstein’s legacy and impact extend far beyond the realm of theoretical physics, leaving an indelible mark on science, philosophy, and culture. His groundbreaking theories revolutionized our understanding of the universe, and his intellectual influence resonates across diverse fields. Einstein’s legacy encompasses scientific achievements, cultural contributions, and a lasting imprint on the collective imagination.

At the heart of Einstein’s legacy are his revolutionary theories of relativity. The Special Theory of Relativity, published in 1905, transformed our understanding of space and time, challenging long-standing notions of absolute measurements and introducing the concept of spacetime. This theory laid the groundwork for subsequent developments in physics and had profound implications for our understanding of the cosmos.

Einstein’s crowning achievement, the General Theory of Relativity, published in 1915, provided a new understanding of gravity as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. This theory not only explained gravitational phenomena with unprecedented precision but also predicted phenomena such as gravitational waves, later confirmed by experimental observations. General relativity has become a cornerstone of modern physics, influencing fields as diverse as astrophysics, cosmology, and the study of black holes.

The iconic equation E=mc², arising from Einstein’s work on the equivalence of mass and energy, became a symbol of the profound interconnections between matter and energy. This equation laid the foundation for advancements in nuclear physics and led to the development of nuclear energy. Einstein’s contributions to the understanding of quantum mechanics, despite his initial reservations about its probabilistic nature, also left a lasting impact on the field.

Beyond his scientific achievements, Einstein’s cultural and philosophical contributions shaped the intellectual landscape of the 20th century. His reflections on the nature of reality, the limitations of human knowledge, and the quest for a unified theory captivated the public imagination. Einstein’s philosophical musings, often expressed in his writings and public pronouncements, influenced debates on determinism, free will, and the nature of scientific inquiry.

Einstein’s fame transcended the scientific community, turning him into a global symbol of intellect, curiosity, and moral integrity. His public persona, marked by his iconic image with disheveled hair and thoughtful gaze, became synonymous with genius. Einstein’s popularity reached unprecedented heights, making him a cultural icon whose influence extended beyond the scientific realm.

Einstein’s advocacy for social justice and political causes further enhanced his legacy. His outspoken stance against fascism, commitment to pacifism, and advocacy for civil rights demonstrated a moral responsibility that went beyond the laboratory. Einstein’s involvement in political and social issues showcased the potential for individuals with intellectual influence to shape public discourse and contribute to the betterment of society.

Einstein’s legacy also manifests in the enduring pursuit of a unified theory, a quest that continues to captivate physicists today. While Einstein did not achieve this goal during his lifetime, his exploration of the connections between fundamental forces laid the groundwork for subsequent generations of researchers, inspiring ongoing efforts to unravel the mysteries of the universe.

In popular culture, Einstein’s name has become synonymous with genius, and his image is often used as a symbol of intellectual prowess. The “Einstein effect” has permeated literature, art, and entertainment, reflecting the fascination with the brilliant mind behind the theories of relativity.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- How to Invest

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Science » Lives of Scientists » Albert Einstein

The best books on albert einstein, recommended by andrew robinson.

Einstein: A Hundred Years of Relativity by Andrew Robinson

Andrew Robinson , author of a biography of Albert Einstein, picks and talks through the five best Albert Einstein books and discusses the life and times of the 'unique genius.'

Interview by Jo Marchant

Albert Einstein: A Biography by Albrecht Folsing

Einstein 1905: The Standard of Greatness by John S. Rigden

The Born-Einstein Letters,1916-1955 by Albert Einstein and Max Born

The Einstein File by Fred Jerome

Einstein on Politics by David Rowe and Robert Schulmann

1 Albert Einstein: A Biography by Albrecht Folsing

2 einstein 1905: the standard of greatness by john s. rigden, 3 the born-einstein letters,1916-1955 by albert einstein and max born, 4 the einstein file by fred jerome, 5 einstein on politics by david rowe and robert schulmann.

B efore we start talking generally about Albert Einstein books , can you give us a brief outline of the significance of Einstein and his work? You’re the author of a biography of Albert Einstein called Einstein: A Hundred Years of Relativity that was republished this year to coincide with the centenary of the theory of general relativity.

There must be literally hundreds of Albert Einstein books. Was it daunting for you to tackle someone of so much significance and interest?

And out of those 1700 Albert Einstein books, we’ve asked you to pick just five! Your first choice is Albert Einstein: A Biography by Albrecht Fölsing published in 1997. What makes this biography so good?

It’s comprehensive, for a start. It is a very big book — one of the biggest on Einstein’s life. Fölsing is a physicist by training so he is able to bring clear explanations of the physics into the life. He’s extremely good at quoting Einstein’s writings and comments in an illuminating way. What makes the book unique is that the author is German, when most biographers come from the English-speaking world. He is able to present Einstein’s ambivalence towards Germany both in physics and in politics and bring that to life in quite a subtle way. To have a German writing on Einstein is particularly interesting.

Just to illuminate that, could you briefly sketch the arc of Einstein’s life for us?

He was born in Germany in 1879 and grew up there until he was 16 when he went to join his parents in Italy. He was unhappy with the German educational system: He was not a very willing student in an authoritarian education system. In fact, his whole life was a battle against authority in different forms. Later in life he said—and it’s one of my favourite quotes from him —“To punish me for my contempt for authority, fate has made me an authority myself.” Finally, he was educated in Switzerland and that’s where he really belongs. He kept Swiss nationality throughout his life, until he went to the United States and became an American citizen when he was quite old, in 1940. So, he is not German by nationality, though he was born there.

“He was not very successful in his relationships with his university lecturers.”

The Swiss atmosphere was very productive for his physics, which started in about 1905 with special relativity and some other key work. He stayed in Germany until 1933, when the Nazis came to power, and he had to get out. He spent a little time in Europe, including in Britain in the early 1930s. Finally, he left Europe forever—never to return—in 1933. He lived in Princeton, New Jersey, at the Institute for Advanced Study, a sort of ivory tower. That suited him very well. He could just think and didn’t have to do any teaching. He lived in Princeton right up to his death in 1955. In that period he wasn’t so successful as a physicist — but became much more involved in political causes like the atomic bomb, the hydrogen bomb, pacifism, and Zionism. As a Jew, he was very interested in the founding of Israel and took an active role in that.

One of the most intriguing things about his life story is the fact that when he did his first really significant revolutionary work in physics, he wasn’t working as a physicist was he? He was working in a patent office and didn’t really have contact with other top physicists at the time.

That’s right. That’s always going to be one of the most intriguing aspects of Einstein and his life. He was a patent clerk in Bern and worked in the patent office for a number of years from 1902. After 1909/1910, he finally takes a position as a professional, academic physicist and moves to various institutions around Europe. Probably his most productive years are those years when he was a patent clerk. Having said that, he came up with general relativity when he was a professor of physics in Berlin. Also, at the patent office, although he was not known in the academic world, he had some contact with academic physicists like Max Planck who was a key supporter of relativity. But we should remember that he was always involved with those two worlds.

Are there any clues as to where his revelations came from? Did his unconventional background play a part in that?

Yes. It’s difficult to pin that down but from an early age—from his teens onwards—he was a great believer in self-education. Like many geniuses, he was not particularly successful in his university training. He attended a famous institution—in Zurich—but was always rebelling against his academic education, constantly reading the latest research on his own. He was not working with other people at all. He was not very successful in his relationships with his university lecturers. He was a rebel and, because he was so passionate about physics, his best ideas really came from his own reading and thinking. From his earliest days as a teenager he was a believer in what he called ‘thought experiments.’ He wasn’t involved with laboratories at all, these experiments were all in his head. One of the most famous ones concerns chasing a light ray. When he was 16 or 17, he imagined whether you could catch up with a light ray and what that would mean.

Did that help him to see things that other physicists didn’t, because he was free to think in his own way?

Let’s dig a little bit more into the science with your next choice which is Einstein 1905: The Standard of Greatness by John Rigden from 2005. This Albert Einstein book is about the so-called ‘miraculous’ year. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Einstein published five papers that year. All of them are considered of great value. The paper that Einstein regarded as the most revolutionary of his work in 1905 was actually about quantum theory. There was another paper about Brownian motion. He showed that the phenomenon of Brownian motion—which had been known for almost 100 years—was actually due to atoms bombarding particles. This was considered proof of the atomic theory of matter by his fellow physicists — the first time that atoms had really been proved to exist. Then, the last of the five papers concerned probably the most famous equation in science: E=mc2. This came out of his first paper on relativity and was published at the end of 1905. As everyone knows, E=mc2 is the basis for what happens with nuclear energy and the atomic bomb later in the century.

This is the principle that energy and mass are two aspects of the same thing. So, if you split apart mass, you’re going to release huge amounts of energy which is what drives nuclear energy and the atomic bomb.

Yes, and c is the speed of light. So, with E=mc2, you can immediately see that the amount of energy is enormous from a small amount of matter because c is such a large number. So, E=mc2 implies a very large amount of energy from a small amount of matter through the process of atomic fission and fusion which Einstein didn’t know about in 1905. Fission was not discovered until later — just before the Second World War , in fact.

Let’s talk about the theory of special relativity, then, which was one of the papers in this miraculous year. Can you talk us through that theory?

It’s a response to Newton’s idea of absolute time and absolute space which Einstein rejected after thinking about it deeply. John Rigden puts it quite well in his book. He says, “A world with absolute space existing apart from absolute time would turn into a world where space and time are joined”. This theory of relativity led to the concept of space-time which is a key thought in general relativity. It’s not easy to explain relativity in a few words, but it rejects absolute time and space, leading to the idea that all motion had to be defined relative to a coordinate system — and that different coordinate systems had to be compared. General relativity was much more comprehensive, it included gravitation and acceleration. In fact, Einstein’s great idea about general relativity was that gravitation and acceleration were equivalent and that we must build our idea of the universe on that thought, rather than regarding them as independent, as Newton did.

General relativity is what we often see illustrated with a rubber sheet with marbles on it distorting the sheet. Is that right?

Yes, the curvature of the rubber sheet is a way of expressing—not literally, it’s a symbol—the curvature of space-time. The experimental proof of general relativity came only later. Probably the most famous aspect of the experimental proof is the bending of a light-ray by the gravitational field of the sun. The light emitted by distant stars was observed to be bent by the gravitational field of the sun in 1919 during an astronomical expedition led by Sir Arthur Eddington, a British astronomer. After that expedition, physicists started to take general relativity much more seriously. There were other experimental proofs as well, but that was the beginning of the idea that general relativity was correct. Before that, it was unproven and Einstein asked astronomers to go looking for it. That’s what happened in 1919. Astronomers were able to back up his theory with observations.

So, after we had the proof of general relativity, how was science different? How did the universe look different? What are the implications of that for the way we see the world now?

The whole idea of the Big Bang has been explained, to a great extent, in terms of general relativity. This came much later than Einstein of course — he was dead by then. General relativity also explains the existence of black holes. Einstein didn’t think they existed, but, since the 1960s, experimental proofs have been found that they do. The whole structure of space and time which Newton imagined, an absolute coordinate system, has been abandoned in favour of a curved space-time formulation. That’s really the result of Einstein’s work.

Going back to the miraculous year of 1905, which is the focus of Rigden’s book. His achievements in so many papers in such a short period of time seems almost superhuman. But he was just human, right? Do we risk exaggerating his genius sometimes?

He was certainly very human and had many failings as well as an extraordinary scientific imagination. Scholars have looked closely at what Einstein was doing in the years up to 1905, there’s not enough evidence to be sure. There were a few letters to his wife, and he published a little bit. There is this feeling that it came out of the blue. It obviously didn’t. No genius works from a sudden eureka moment and it’s not like that, even with Einstein. The problem is that we don’t really know exactly what he was reading and how his thought process worked. What we do know is what he published in 1905 and that he was fascinated by contradictions in physics. He imagined chasing a light-ray in his mind and asked what a light-ray would look like if you caught up with it and came to the conclusion that it’s an impossible physical situation. That, according to Maxwell’s laws of electromagnetism, there was no such thing as catching a light-ray. From that, he concluded that light always moves at a constant speed — independent of the coordinate system you were using to measure it with. It didn’t matter how fast an observer moved, light would always move at a constant speed faster than the observer.

“Einstein’s great idea about general relativity was that gravitation and acceleration were equivalent and that we must build our idea of the universe on that thought.”

Another contradiction that fascinated him was to do with magnetism and electric charge. He imagined that if you had a stationary charge observed by a stationary observer, there would be no magnetic field which could be observed with a compass. But, if you kept the stationary charge and then the observer started to move, by Maxwell’s definition of electromagnetism, he/she would observe a magnetic field with a compass. So which was true? Was there a magnetic field or wasn’t there? He said that’s a contradiction, we have to resolve it. And he did resolve it, with his theory of relativity.

There’s often a temptation to move away from contradiction but it sounds like he just confronted it head-on.

Let’s talk about your next choice of Albert Einstein books which is the Born-Einstein Letters, 1916-1955 , which was republished in 2005. This is a collection of correspondence between Einstein and his friend, the German physicist, Max Born. What do they talk about in the letters?

It was a long friendship. It began with physics but developed into a relationship with many other overtones to do with politics, ethics, and the state of Germany during those years. Both of them won Nobel Prizes, so when we read them we’re exposed to a couple of very intelligent people writing about science. Throughout the letters, you get these human asides: It’s a very unique mixture of science and humanities. They disagreed frequently and they disagreed most famously about quantum theory. In one letter from Einstein to Born he says, ‘The old one does not play dice. I can’t accept the possibility of chance ruling the universe.’ And Born never agreed with that. Right to the end of the correspondence, they’re arguing about the role of probability in physics.