- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Language and Literacy Development: Research-Based, Teacher-Tested Strategies

You are here

“Why does it tick and why does it tock?”

“Why don’t we call it a granddaughter clock?”

“Why are there pointy things stuck to a rose?”

“Why are there hairs up inside of your nose?”

She started with Why? and then What? How? and When? By bedtime she came back to Why? once again. She drifted to sleep as her dazed parents smiled at the curious thoughts of their curious child, who wanted to know what the world was about. They kissed her and whispered, “You’ll figure it out.”

—Andrea Beaty, Ada Twist, Scientist

I have dozens of favorite children’s books, but while working on this cluster about language and literacy development, Ada Twist, Scientist kept coming to mind. Ada is an African American girl who depicts the very essence of what it means to be a scientist. The book is a celebration of children’s curiosity, wonder, and desire to learn.

The more I thought about language and literacy, the more Ada became my model. All children should have books as good as Ada Twist, Scientist read to them. All children should be able to read books like Ada Twist, Scientist by the end of third grade. All children should be encouraged to ask questions about their world and be supported in developing the literacy tools (along with broad knowledge, inquiring minds, and other tools!) to answer those questions. All children should see themselves in books that rejoice in learning.

Early childhood teachers play a key role as children develop literacy. While this cluster does not cover the basics of reading instruction, it offers classroom-tested ways to make common practices like read alouds and discussions even more effective.

The cluster begins with “ Enhancing Toddlers’ Communication Skills: Partnerships with Speech-Language Pathologists ,” by Janet L. Gooch. In a mutually beneficial partnership, interns from a university communication disorders program supported Early Head Start teachers in learning several effective ways to boost toddlers’ language development, such as modeling the use of new vocabulary and expanding on what toddlers say. (One quirk of Ada Twist, Scientist is that Ada doesn’t speak until she is 3; in real life, that would be cause for significant concern. Having a submission about early speech interventions was pure serendipity.) Focusing on preschoolers, Kathleen M. Horst, Lisa H. Stewart, and Susan True offer a framework for enhancing social, emotional, and academic learning. In “ Joyful Learning with Stories: Making the Most of Read Alouds ,” they explain how to establish emotionally supportive routines that are attentive to each child’s strengths and needs while also increasing group discussions. During three to five read alouds of a book, teachers engage children in building knowledge, vocabulary, phonological awareness, and concepts of print.

Next up, readers go inside the lab school at Stepping Stones Museum for Children. In “ Equalizing Opportunities to Learn: A Collaborative Approach to Language and Literacy Development in Preschool ,” Laura B. Raynolds, Margie B. Gillis, Cristina Matos, and Kate Delli Carpini share the engaging, challenging activities they designed with and for preschoolers growing up in an under-resourced community. Devondre finds out how hard Michelangelo had to work to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and Sayo serves as a guide in the children’s classroom minimuseum— taking visitors to her artwork!

Moving into first grade, Laura Beth Kelly, Meridith K. Ogden, and Lindsey Moses explain how they helped children learn to lead and participate in meaningful discussions of literature. “ Collaborative Conversations: Speaking and Listening in the Primary Grades ” details the children’s progress (and the teacher’s methods) as they developed discussion-related social and academic skills. Although the first graders still required some teacher facilitation at the end of the school year, they made great strides in preparing for conversations, listening to their peers, extending others’ comments, asking questions, and reflecting on discussions.

Rounding out the cluster are two articles on different aspects of learning to read. In “ Sounding It Out Is Just the First Step: Supporting Young Readers ,” Sharon Ruth Gill briefly explains the complexity of the English language and suggests several ways teachers can support children as they learn to decode fluently. Her tips include giving children time to self-correct, helping them use semantic and syntactic cues, and analyzing children’s miscues to decide what to teach next.

In “ Climbing Fry’s Mountain: A Home–School Partnership for Learning Sight Words ,” Lynda M. Valerie and Kathleen A. Simoneau describe a fun program for families. With game-like activities that require only basic household items, children in kindergarten through second grade practice reading 300 sight words. Children feel successful as they begin reading, and teachers reserve instructional time for phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and other essentials of early reading.

At the end of Ada Twist, Scientist , there is a marvelous illustration of Ada’s whole family reading. “They remade their world—now they’re all in the act / of helping young Ada sort fiction from fact.” It reminds me of the power of reading and of the important language and literacy work that early childhood educators do every day.

—Lisa Hansel

We’d love to hear from you!

Send your thoughts on this issue, as well as topics you’d like to read about in future issues of Young Children , to [email protected] .

Would you like to see your children’s artwork featured? For guidance on submitting print-quality photos (as well as details on permissions and licensing), see NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/authors-photographers/photos .

Is your classroom full of children’s artwork? To feature it in Young Children , see the link at the bottom of the page or email [email protected] for details.

Lisa Hansel, EdD, is the editor in chief of NAEYC's peer-reviewed journal, Young Children .

Vol. 74, No. 1

Print this article

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Untying the Gordian Knot of Early Language Screening and Improved Developmental Outcomes

- 1 Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, Nashville, Tennessee

- 2 University of Washington, Seattle

- Editorial Recommendations for Speech and Language Screenings Marisha L. Speights, PhD, CCC-SLP; Maranda K. Jones, BA; Megan Y. Roberts, PhD, CCC-SLP JAMA

- US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF Recommendation: Screening for Speech and Language Delay and Disorders US Preventive Services Task Force; Michael J. Barry, MD; Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA; Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH; David Chelmow, MD; Tumaini Rucker Coker, MD, MBA; Esa M. Davis, MD, MPH; Katrina E. Donahue, MD, MPH; Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD, MS; Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH; Carol M. Mangione, MD, MSPH; Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH; Goutham Rao, MD; John M. Ruiz, PhD; James Stevermer, MD, MSPH; Joel Tsevat, MD, MPH; Sandra Millon Underwood, PhD, RN; John B. Wong, MD JAMA

- US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF Review: Screening for Speech and Language Delay and Disorders in Children Cynthia Feltner, MD, MPH; Ina F. Wallace, PhD; Sallie W. Nowell, PhD, CCC-SLP; Colin J. Orr, MD, MPH; Brittany Raffa, MD; Jennifer Cook Middleton, PhD; Jessica Vaughan, MPH; Claire Baker; Roger Chou, MD; Leila Kahwati, MD, MPH JAMA

- JAMA Patient Page Patient Information: Screening for Speech and Language Problems in Young Children Jill Jin, MD, MPH JAMA

Early language development is the foundation for communication, social relationships, reading, academic accomplishments, job performance, and other life-long indicators of positive social development and economic success. Early detection of significant delays in language development and effective intervention, when needed, are essential to ensuring optimal developmental outcomes. Estimates of primary language delays in children younger than 5 years vary widely, ranging from less than 5% to nearly 20%, depending on the age of the child, the inclusion of speech and/or language criteria, the specific measures used, and the criteria for identification of significant delays. 1 - 4 Given that only 30% of children younger than 5 years are screened when their primary caregivers or teachers do not express concerns about their speech or language development and only 50% of children eligible for intervention are reported to receive interventions, there is a need for contemporary evidence-based guidance on the potential positive and negative outcomes of screening.

Although there are documented associations of early speech and language delays with subsequent poor academic, social, and behavioral outcomes, 5 , 6 evidence linking screening to effective interventions and subsequent improvements in long-term developmental outcomes is limited. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation statement concluded that “the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for speech and language delay and disorders in children age 5 years or younger” (I statement). 7 , 8 No studies specifically examining the risks and benefits of screening vs no screening were identified. 7 , 8 The reports by the UPSTF 7 and Feltner et al 8 reviewed a total of 38 studies of screening and intervention meeting stringent inclusion criteria for methodological quality and outcomes. In this editorial, we highlight several secondary contributions of the USPSFT recommendations, 7 , 8 suggest additions that might enhance the impact of the recommendations, and make suggestions for research and policy, with particular emphasis on the role of parents as collaborators in screening and intervention.

Contributions of the Report

In addition to the overall recommendation, 7 , 8 the USPSTF makes several important contributions to understanding the “Gordian knot” linking speech and language screening to improved long-term developmental outcomes. First, the mean incidence of primary speech and language delays was 16% across 21 studies enrolling 7489 children younger than 5 years. 7 , 8 There was considerable variability in reported incidence by study, screening measure, language constructs (eg, specific vs global language skills), and informant (eg, parent vs clinician). This variability is important; however, the mean incidence level reported across studies suggests early screening would detect a significant number of children. Second, overall sensitivity and specificity data indicated that early delays in specific language skills and articulation can be detected with available screening instruments used by parents or clinicians. 7 , 8 Again, variability across screening instruments, speech and language constructs, and informants was noted; however, several screening tools appeared promising for immediate practice and candidates for future research studies. Third, across all components of the synthesis, there was evidence that parents were essential partners in screening and effective intervention delivery. 7 , 8 For example, parent reports of specific child language skills were precise, with high levels of sensitivity and specificity similar to examiner levels but with less variability. Most studies in which parents were trained to deliver interventions to their children reported positive outcomes for some measures. Positive outcomes were associated with longer parent implementation. These results, 7 , 8 when paired with meta-analysis of parent-implemented interventions across populations of young children with language impairment, 9 - 11 support the use of parent-implemented interventions to improve language outcomes. In the USPSTF analysis of contextual factors impacting screening, 7 , 8 parent characteristics (eg, socioeconomic status, single parent status, social isolation, primary language other than English) were associated with participation in screening and intervention. These findings suggest that parents may be gatekeepers for their children’s access to a range of supports for language development. 12 The associations between these indicated parent characteristics and expected disparities in health care access deserve notice, since this may be the mediating association between parent characteristics and participating in screening and intervention.

Expanding on Important Information From the Synthesis

All syntheses of empirical studies are limited by the quantity and quality of the studies under review; the USPSTF evidence review and recommendation statement are no exception. 7 , 8 However, 2 additions to the synthesis of the available studies could have contributed important information. First, age is a critical variable in understanding language development and delay. The use of the broad age umbrella, younger than 5 years, for synthesizing studies may have masked important differences associated with age at screening. Accuracy in identification of speech and language delays generally increases with age; assessments after age 36 months are likely to be more reliable than those prior to age 30 months. 2 , 13 , 14 Child age may also impact the accuracy and sensitivity of parent reports of their children’s language development. Parents are likely to be more reliable informants about their children’s early development of specific skills (eg, vocabulary) than later development of more complex skills (eg, morphology, syntax) that may be indicative of a developmental language delay. Analysis of the screening studies to characterize age-related precision in screening could provide preliminary guidance about when to screen and when parents are most valuable as informants.

Second, characterizing the outcomes of intervention studies in terms of measures with statistically significant outcomes may have masked important information about the magnitude of the changes observed across measures and studies. A meta-analysis of the speech and language outcomes would be constrained in the small sample of language intervention studies and even smaller sample of speech studies. However, including the effect sizes in the USPSTF synthesis 7 , 8 would have added important information about the relative benefits of intervention, consistent with contemporary standards for reporting the outcomes of intervention research.

Recommendations for Research

The evidence report by Feltner et al 8 and the USPSTF recommendation statement 7 highlight gaps in evidence related to screening and treatment studies with short-term and long-term follow-up addressing key academic, behavioral, and well-being outcomes. There is a particular absence of studies including young children and families for whom disparities in health care and limited resources are also barriers to accessing screening and intervention. This recommendation again draws attention to the difficulties in resolving the Gordian knot linking screening to functional long-term outcomes. At the center of the knot is the need for funding for inclusive research at scale and with sufficient replication to provide evidence to guide practice and policy recommendations.

Funding is needed for 4 key areas with representative populations of children and families. First, we need screening research that describes trajectories of speech and language development over the first 5 years with follow-up through the transition to reading. Second, validation must be performed for promising, pragmatic screening measures across critical periods in language development in early childhood, including assessing the validity for valued language, academic, and social outcomes. Third, we need intervention research based on contextualized, promising interventions. Such interventions would be calibrated for intensity and dosage associated with optimal developmental outcomes and responsive to the cultural, linguistic, and caregiving contexts of families. Particular attention should be given to caregiver-implemented interventions and interventions provided by teachers in childcare and prekindergarten classrooms. Fourth, there is a need for implementation-level and systems-level research that places screening at the nexus of the health care, community, and education systems. The goal is to understand how to link and supplement existing systems to ensure sustainable delivery of early language screening that leads to effective and timely intervention. This research should also address preparing systems to implement the methods, practices, and policies based on evidence from the research recommended.

Public Education Initiatives to Support Parents

Parents and caregivers of young children are not likely to have extensive knowledge about early language development and how it relates to children’s long-tern academic and social outcomes. Parents need information about language development, why screening is important, and the potential of early intervention to support their child’s development. This information should be accessible and timely, provided in parents’ primary language, and presented without the stigma of labeling children at risk due to poverty, neighborhood, race, ethnicity, home language, or family structure. Without culturally and linguistically accessible, unbiased information, it is unlikely parents will choose to participate in screening their children’s emerging speech and language. Many families need more than information; they need active assistance to access follow-up assessments and opportunities to participate in interventions that reflect their language and culture as well as addressing their children’s needs. Innovative family-centered approaches to providing information, screening, and intervention in communities are needed to support parents as well as children. Health care practitioners, particularly pediatricians, play a critical role in language screenings for all children and in facilitating access to comprehensive assessment and intervention when indicated. Collaboration between health care and educational systems is essential.

Conclusions

There is a critical need for research on screening for early language delays, including evaluating measures that are sensitive and specific in detecting delays in all young children and testing a range of culturally and linguistically contextualized early interventions to effectively address children’s delays. Given the lifelong importance of language related skills, the USPSTF recommendation 7 , 8 must be construed as a challenge rather than a conclusion.

Published: January 23, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54529

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2024 Kaiser AP et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Ann P. Kaiser, PhD, Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, 110 Magnolia Cir, Ste 314, Nashville, TN 37232 ( [email protected] ).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

See More About

Kaiser AP , Chow JC , Baumingham JE. Untying the Gordian Knot of Early Language Screening and Improved Developmental Outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2354529. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54529

Manage citations:

© 2024

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Observation

The littlest linguists: new research on language development.

- Bilingualism

- Developmental Psychology

- Language Development

How do children learn language, and how is language related to other cognitive and social skills? For decades, the specialized field of developmental psycholinguistics has studied how children acquire language—or multiple languages—taking into account biological, neurological, and social factors that influence linguistic developments and, in turn, can play a role in how children learn and socialize. Here’s a look at recent research (2020–2021) on language development published in Psychological Science .

Preverbal Infants Discover Statistical Word Patterns at Similar Rates as Adults: Evidence From Neural Entrainment

Dawoon Choi, Laura J. Batterink, Alexis K. Black, Ken A. Paller, and Janet F. Werker (2020)

One of the first challenges faced by infants during language acquisition is identifying word boundaries in continuous speech. This neurological research suggests that even preverbal infants can learn statistical patterns in language, indicating that they may have the ability to segment words within continuous speech.

Using electroencephalogram measures to track infants’ ability to segment words, Choi and colleagues found that 6-month-olds’ neural processing increasingly synchronized with the newly learned words embedded in speech over the learning period in one session in the laboratory. Specifically, patterns of electrical activity in their brains increasingly aligned with sensory regularities associated with word boundaries. This synchronization was comparable to that seen among adults and predicted future ability to discriminate words.

These findings indicate that infants and adults may follow similar learning trajectories when tracking probabilities in speech, with both groups showing a logarithmic (rather than linear) increase in the synchronization of neural processing with frequent words. Moreover, speech segmentation appears to use neural mechanisms that emerge early in life and are maintained throughout adulthood.

Parents Fine-Tune Their Speech to Children’s Vocabulary Knowledge

Ashley Leung, Alexandra Tunkel, and Daniel Yurovsky (2021)

Children can acquire language rapidly, possibly because their caregivers use language in ways that support such development. Specifically, caregivers’ language is often fine-tuned to children’s current linguistic knowledge and vocabulary, providing an optimal level of complexity to support language learning. In their new research, Leung and colleagues add to the body of knowledge involving how caregivers foster children’s language acquisition.

The researchers asked individual parents to play a game with their child (age 2–2.5 years) in which they guided their child to select a target animal from a set. Without prompting, the parents provided more informative references for animals they thought their children did not know. For example, if a parent thought their child did not know the word “leopard,” they might use adjectives (“the spotted, yellow leopard”) or comparisons (“the one like a cat”). This indicates that parents adjust their references to account for their children’s language knowledge and vocabulary—not in a simplifying way but in a way that could increase the children’s vocabulary. Parents also appeared to learn about their children’s knowledge throughout the game and to adjust their references accordingly.

Infant and Adult Brains Are Coupled to the Dynamics of Natural Communication

Elise A. Piazza, Liat Hasenfratz, Uri Hasson, and Casey Lew-Williams (2020)

This research tracked real-time brain activation during infant–adult interactions, providing an innovative measure of social interaction at an early age. When communicating with infants, adults appear to be sensitive to subtle cues that can modify their brain responses and behaviors to improve alignment with, and maximize information transfer to, the infants.

Piazza and colleagues used functional near-infrared spectroscopy—a noninvasive measure of blood oxygenation resulting from neural activity that is minimally affected by movements and thus allows participants to freely interact and move—to measure the brain activation of infants (9–15 months old) and adults while they communicated and played with each other. An adult experimenter either engaged directly with an infant by playing with toys, singing nursery rhymes, and reading a story or performed those same tasks while turned away from the child and toward another adult in the room.

Results indicated that when the adult interacted with the child (but not with the other adult), the activations of many prefrontal cortex (PFC) channels and some parietal channels were intercorrelated, indicating neural coupling of the adult’s and child’s brains. Both infant and adult PFC activation preceded moments of mutual gaze and increased before the infant smiled, with the infant’s PFC response preceding the adult’s. Infant PFC activity also preceded an increase in the pitch variability of the adult’s speech, although no changes occurred in the adult’s PFC, indicating that the adult’s speech influenced the infant but probably did not influence neural coupling between the child and the adult.

Theory-of-Mind Development in Young Deaf Children With Early Hearing Provisions

Chi-Lin Yu, Christopher M. Stanzione, Henry M. Wellman, and Amy R. Lederberg (2020)

Language and communication are important for social and cognitive development. Although deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) children born to deaf parents can communicate with their caregivers using sign language, most DHH children are born to hearing parents who do not have experience with sign language. These children may have difficulty with early communication and experience developmental delays. For instance, the development of theory of mind—the understanding of others’ mental states—is usually delayed in DHH children born to hearing parents.

Yu and colleagues studied how providing DHH children with hearing devices early in life (before 2 years of age) might enrich their early communication experiences and benefit their language development, supporting the typical development of other capabilities—in particular, theory of mind. The researchers show that 3- to 6-year-old DHH children who began using cochlear implants or hearing aids earlier had more advanced language abilities, leading to better theory-of-mind growth, than children who started using hearing provisions later. These findings highlight the relationships among hearing, language, and theory of mind.

The Bilingual Advantage in Children’s Executive Functioning Is Not Related to Language Status: A Meta-Analytic Review

Cassandra J. Lowe, Isu Cho, Samantha F. Goldsmith, and J. Bruce Morton (2021)

Acommon idea is that bilingual children, who grow up speaking two languages fluently, perform better than monolingual children in diverse executive-functioning domains (e.g., attention, working memory, decision making). This meta-analysis calls that idea into question.

Lowe and colleagues synthesized data from studies that compared the performance of monolingual and bilingual participants between the ages of 3 and 17 years in executive-functioning domains (1,194 effect sizes). They found only a small effect of bilingualism on participants’ executive functioning, which was largely explained by factors such as publication bias. After accounting for these factors, bilingualism had no distinguishable effect. The results of this large meta-analysis thus suggest that bilingual and monolingual children tend to perform at the same level in executive-functioning tasks. Bilingualism does not appear to boost performance in executive functions that serve learning, thinking, reasoning, or problem solving.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Teaching: Ethical Research to Help Romania’s Abandoned Children

An early intervention experiment in Bucharest can introduce students to the importance of responsive caregiving during human development.

Silver Linings in the Demographic Revolution

Podcast: In her final column as APS President, Alison Gopnik makes the case for more effectively and creatively caring for vulnerable humans at either end of life.

Communicating Psychological Science: The Lifelong Consequences of Early Language Skills

“When families are informed about the importance of conversational interaction and are provided training, they become active communicators and directly contribute to reducing the word gap (Leung et al., 2020).”

Privacy Overview

The Impact of Peer Interactions on Language Development Among Preschool English Language Learners: A Systematic Review

- Published: 20 November 2020

- Volume 50 , pages 49–59, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Princess-Melissa Washington-Nortey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8721-1710 1 ,

- Fa Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2839-6820 1 ,

- Yaoying Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3683-5347 1 ,

- Amber Brown Ruiz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3587-3747 1 ,

- Chin-Chih Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9503-8145 1 &

- Christine Spence ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6158-7082 1

3596 Accesses

12 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

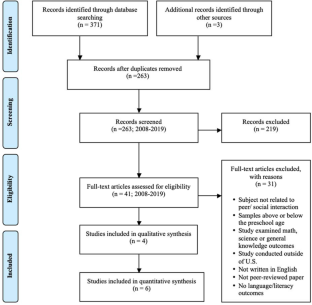

Studies showing that early language skills are important predictors of later academic success and social outcomes have prompted efforts to promote early language development among children at risk. Good social skills, a competence identified in many children who are English Language Learners (ELLs), have been posited in the general literature as facilitators of language development. Yet to date, a comprehensive review on the nature and impact of social interaction on language development among children who are ELLs has not been conducted. Using PRISMA procedures, a systematic review was conducted and 10 eligible studies published between 2008 and 2019 were identified. Findings revealed that despite their limited language capabilities, children who are ELLs can engage in complex speech during peer interaction. However, the nature and frequency of interactions, as well as the unique skill sets of communication partners may affect their development of relevant language skills. These findings have implications for policy and intervention development for preschool settings in the United States.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Early Language Intervention in School Settings: What Works for Whom?

The Influence of Teachers, Peers, and Play Materials on Dual Language Learners’ Play Interactions in Preschool

An exploration of language and social-emotional development of children with and without disabilities in a statewide pre-kindergarten program.

Aikens, N., Tarullo, L., Hulsey, L., Ross, C., West, J., & Xue, Y. (2010). A Year in Head Start Children Families and Programs (No. 118a1d963bb04e23b24ea60039c88337). Mathematica Policy Research.

Atkins-Burnett, S., Xue, Y., & Aikens, N. (2017). Peer effects on children’s expressive vocabulary development using conceptual scoring in linguistically diverse preschools. Early Education and Development, 28 (7), 901–920.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, S., & Phillips, D. (2017). Is pre-K classroom quality associated with kindergarten and middle-school academic skills? Developmental Psychology, 53 (6), 1063.

Bell, E. R., Greenfield, D. B., Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., & Carter, T. M. (2016). Peer play as a context for identifying profiles of children and examining rates of growth in academic readiness for children enrolled in head start. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108 (5), 740.

Bernstein, K. A. (2018). The perks of being peripheral: English learning and participation in a preschool classroom network of practice. TESOL Quarterly, 52 (4), 798–844.

Burchinal MR, Pace A, Alper R, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM (2016) Early language outshines other predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Presented at Assoc. Child. Fam. Conf. (ACF), Washington, DC, p. 11–13.

Bustamante, A. S., & Hindman, A. H. (2019). Classroom quality and academic school readiness outcomes in head start: The indirect effect of approaches to learning. Early Education and Development, 30 (1), 19–35.

Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., DeCoster, J., & Forston, L. D. (2015). Teacher–child conversations in preschool classrooms: Contributions to children’s vocabulary development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30, 80–92.

Carr, R. C., Mokrova, I. L., Vernon-Feagans, L., & Burchinal, M. R. (2019). Cumulative classroom quality during pre-kindergarten and kindergarten and children’s language, literacy, and mathematics skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 218–228.

Franco, X., Bryant, D. M., Gillanders, C., Castro, D. C., Zepeda, M., & Willoughby, M. T. (2019). Examining linguistic interactions of dual language learners using the language interaction snapshot (LISn). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 50–61.

Galindo, C., & Fuller, B. (2010). The social competence of latino kindergartners and growth in mathematical understanding. Developmental psychology, 46 (3), 579.

Guerrero, A. D., Fuller, B., Chu, L., Kim, A., Franke, T., Bridges, M., & Kuo, A. (2013). Early growth of mexican-american children: Lagging in preliteracy skills but not social development. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17 (9), 1701–1711.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Owen, M. T., Golinkoff, R. M., Pace, A., & Suma, K. (2015). The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science, 26 (7), 1071–1083.

Justice, L. M., Jiang, H., & Strasser, K. (2018). Linguistic environment of preschool classrooms: What dimensions support children’s language growth? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42, 79–92.

Justice, L. M., Petscher, Y., Schatschneider, C., & Mashburn, A. (2011). Peer effects in preschool classrooms: Is children’s language growth associated with their classmates’ skills? Child Development, 82 (6), 1768–1777.

Kyratzis, A. (2017). Peer ecologies for learning how to read: Exhibiting reading, orchestrating participation, and learning over time in bilingual Mexican-American preschoolers’ play enactments of reading to a peer. Linguistics and Education, 41, 7–19.

Kyratzis, A., Tang, Y. T., & Koymen, S. B. (2009). Codes, code-switching, and context: Style and footing in peer group bilingual play. Multilingua, 28, 265–290.

Mashburn, A. J., Justice, L. M., Downer, J. T., & Pianta, R. C. (2009). Peer effects on children’s language achievement during pre-kindergarten. Child Development, 80 (3), 686–702.

McWayne, C., & Cheung, K. (2009). A picture of strength: Preschool competencies mediate the effects of early behavior problems on later academic and social adjustment for head start children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30 (3), 273–285.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151 (4), 264–269.

National Education Association. (2015). Understanding the gaps: Who are we leaving behind and how far. NEA Education Policy and Practice & Priority Schools Departments and Center for Great Public Schools .

Pace, A., Luo, R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2017). Identifying pathways between socioeconomic status and language development. Annual Review of Linguistics, 3, 285–308.

Palermo, F., & Mikulski, A. M. (2014). The role of positive peer interactions and English exposure in Spanish-speaking preschoolers’ English vocabulary and letter-word skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly , 29 (4), 625–635.

Palermo, F., Mikulski, A. M., Fabes, R. A., Hanish, L. D., Martin, C. L., & Stargel, L. E. (2014). English exposure in the home and classroom: Predictions to spanish-speaking preschoolers’ english vocabulary skills. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35 (6), 1163–1187.

Pancsofar, N., & Vernon-Feagans, L. (2006). Mother and father language input to young children: Contributions to later language development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27 (6), 571–587.

Piker, R. A. (2013). Understanding influences of play on second language learning: A microethnographic view in one head start preschool classroom. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 11 (2), 184–200.

Pungello, E. P., Iruka, I. U., Dotterer, A. M., Mills-Koonce, R., & Reznick, J. S. (2009). The effects of socioeconomic status, race, and parenting on language development in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 45 (2), 544.

Rathbone, J., Hoffmann, T., & Glasziou, P. (2015). Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Systematic reviews, 4 (1), 80.

Romeo, R. R., Leonard, J. A., Robinson, S. T., West, M. R., Mackey, A. P., Rowe, M. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children’s conversational exposure is associated with language-related brain function. Psychological Science, 29 (5), 700–710.

Sawyer, B., Atkins-Burnett, S., Sandilos, L., Scheffner Hammer, C., Lopez, L., & Blair, C. (2018). Variations in classroom language environments of preschool children who are low-income and linguistically diverse. Early Education and Development, 29 (3), 398–416.

Schechter, C., & Bye, B. (2007). Preliminary evidence for the impact of mixed-income preschools on low-income children’s language growth. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22 (1), 137–146.

Spencer, T. D., Petersen, D. B., Slocum, T. A., & Allen, M. M. (2015). Large group narrative intervention in head start preschools: Implications for response to intervention. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13 (2), 196–217.

Stoddart, T., Solis, J., Tolbert, S., Bravo, M. (2010). A framework for the effective science teaching of English language learners in elementary schools. Teaching science with Hispanic ELLs in K-16 classrooms, 151–181.

Suskind, D., Suskind, B., Lewinter-Suskind, L. (2015). Thirty million words: Building a child's brain: tune in, talk more, take turns. Dutton Books.

Vernon-Feagans, L., Mokrova, I. L., Carr, R. C., Garrett-Peters, P. T., Burchinal, M. R., & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2019). Cumulative years of classroom quality from kindergarten to third grade: Prediction to children’s third grade literacy skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 531–540.

Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2014). Does higher peer socio-economic status predict children’s language and executive function skills gains in prekindergarten? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35 (5), 422–432.

Wong, K., Boben, M., Thomas, M. C. (2018). Disrupting the early learning status quo: Providence Talks as innovative policy in diverse urban communities.

Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Justice, L. M., & Logan, J. A. (2019). The mediating role of classroom quality on peer effects and language gain in pre-kindergarten ECSE classrooms. Applied Developmental Science, 23 (1), 90–103.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Virginia Commonwealth University, 1015 West Main Street, Richmond, VA, 23284-2020, USA

Princess-Melissa Washington-Nortey, Fa Zhang, Yaoying Xu, Amber Brown Ruiz, Chin-Chih Chen & Christine Spence

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fa Zhang .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Washington-Nortey, PM., Zhang, F., Xu, Y. et al. The Impact of Peer Interactions on Language Development Among Preschool English Language Learners: A Systematic Review. Early Childhood Educ J 50 , 49–59 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01126-5

Download citation

Accepted : 20 October 2020

Published : 20 November 2020

Issue Date : January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01126-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- English language learners

- Peer interactions

- Language development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

MINI REVIEW article

Early childhood education language environments: considerations for research and practice.

- 1 Department of Human Development and Family Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

- 2 Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

The importance of developing early language and literacy skills is acknowledged by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a global human rights issue. Indeed, research suggests that language abilities are foundational for a host of cognitive, behavioral, and social–emotional outcomes. Therefore, it is critical to provide experiences that foster language acquisition across early learning settings. Central to these efforts is incorporating assessments of language environments into research and practice to drive quality improvement. Yet, several barriers may be preventing language environment assessments from becoming widely integrated into early education. In this brief, we review evidence on the types of experiences that promote language development, describe characteristics of language environment assessments, and outline practical and philosophical considerations to assist with decision-making. Further, we offer recommendations for future research that may contribute knowledge regarding strategies to assess and support language development. In addressing both areas, we highlight the potential for early childhood language environments to advance equity.

Introduction

Despite compelling evidence indicating the importance of environmental inputs for language acquisition within the first 5 years of life (e.g., Anderson et al., 2021 ), several obstacles have prevented language environment assessments from becoming widely integrated into early education settings (e.g., Mitchell, 2016 ). First, for any program that seeks to enhance language environments, measuring the processes known to drive language development is fundamental prior to developing intervention strategies and monitoring continual quality improvement. Yet, the limited application of language environment assessments in interventions or programs of scale restricts our understanding of how to effectively utilize language assessments to evaluate practice (e.g., Greenwood et al., 2020 ). Thus, we offer opportunities for future research that have the potential to contribute knowledge regarding strategies to assess and support language development and fill critical gaps in the literature. Second, selecting a language environment assessment that meets program goals, can be administered with fidelity, is accommodating to resource constraints, and is appropriate for informing professional development can be arduous (e.g., Zaslow et al., 2009 ; Derrick-Mills et al., 2014 ; Ackerman, 2019 ). To help practitioners overcome this challenge, we review evidence on the types of experiences that promote language development, describe characteristics of language environment assessments, and outline practical and philosophical considerations to assist with decision-making. The overall goal of this mini review is to demystify the complexities of early childhood language environments and articulate the ways in which language environment assessments can drive practice. We believe this is an essential step toward improving early language experiences and evaluating the impacts of education programming on learning in this fundamental developmental domain.

Environments that support early language development

Language is a complex and multifaceted construct. It typically includes the production of speech sounds and patterns (phonetics and phonology), the words and associated knowledge (semantics), and the systems for combining parts of words together and words into sentences to convey meaning (grammar; Bates et al., 1992 ; Hoff, 2013 ). Research examining these underlying components of language has uncovered diverse developmental trajectories starting in early childhood ( Huttenlocher et al., 2010 ). Indeed, children develop language relatively early compared to other domains, not only because it necessary for communication ( Cates et al., 2012 ), but also because it is foundational for the acquisition of higher-order skills ( Kuhn et al., 2014 ). The first 5 years constitutes a sensitive period of development, as children increase their language learning at a rapid rate due to increased neural plasticity in the brain ( Knudsen, 2004 ). By age four, language development becomes more stable and is highly predictive of language abilities in adolescence ( Bornstein et al., 2014 ). For instance, one study demonstrated that children’s oral narrative skills measured at school entry were related to their reading comprehension performance at age 16 ( Suggate et al., 2018 ). Early language skills are also linked to a host of outcomes across developmental domains. These include cognitive skills (e.g., executive functioning), academic achievement, and socioemotional competence ( Bleses et al., 2016 ; Hentges et al., 2021 ; Bruce and Bell, 2022 ). Thus, it is important to provide experiences that promote language acquisition early in life to ensure children are set on a path for success.

Children’s language abilities are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors ( Hoff-Ginsberg, 1998 ; Hayiou-Thomas et al., 2012 ). Notably, the amount of speech children hear has a direct impact on their developing language, suggesting their language development is shaped by social contexts ( Mahr and Edwards, 2018 ). To illustrate, Hart and Risley (1995) documented a 30-million-word gap between children from families with higher socioeconomic status (SES) and children from families with lower SES. Moreover, neurological studies indicate children who experience more conversational turns with adults have more complex speech, which is reflected in brain functioning that underlies language processing ( Hutton et al., 2017 ; Romeo et al., 2018 ). A large body of observational work has also examined specific aspects of adult interactions that affect language development (see Golinkoff et al., 2019 for a review). Recently, a meta-analysis revealed moderate effects of the quality (e.g., diversity and reciprocity) and quantity (e.g., number of words) of language inputs in the home environment on children’s language development ( Anderson et al., 2021 ). Specifically, conversational interactions between infants and adults account for significant variation in vocabulary in school-age children ( Gilkerson et al., 2018 ). Yet, children are exposed to many sources of language input that are not captured by parent–child interactions, potentially underestimating the language environments of children from low SES backgrounds ( Sperry et al., 2019 ). For instance, “social determinants of language development” outside of the immediate family include community resources, educational programs, and public policies ( Di Sante and Potvin, 2022 ). Notably, the majority of children who are under the age of five spend their day in some type of non-parental care ( Pilarz, 2018 ). Therefore, it is necessary to consider the features of child care and education settings that impact language acquisition.

Classroom and home environments provide very different language opportunities for children. Comparisons between child care and home language environments generally reveal more language interactions occurring between children and caregivers in the home relative to teachers and children in the classroom ( Larson et al., 2020 ). Still, research has documented an association between language exposure in early childhood education settings and children’s language abilities and growth (e.g., Turnbull et al., 2009 ). For example, one study projected a difference of 100 adult words heard per 5 min (equivalent to approximately 1,800,000 words per year) that could be attributed to variation in prekindergarten classroom language environments ( Duncan et al., 2023 ). Children from families with low SES are more likely to experience language of more limited complexity and diversity in the home and school context ( Neuman et al., 2018 ; Duncan et al., 2023 ). This may be, in part, due to families having limited access to high-quality early childhood education in higher poverty communities ( Bassok and Galdo, 2016 ). Targeting the quality of early learning environments in areas with greater socioeconomic disadvantage, and dedicating more public funding to these communities, may help to reduce the observed income quality gradient in ECE ( Hatfield et al., 2015 ; Cloney et al., 2016 ). For example, research indicates that improving community-level social determinants, such as increasing the supply of child care, may elevate children’s literacy scores ( Lipscomb et al., 2019 ). Thus, ensuring children have access to rich language environments inside and outside of the home may be one promising approach to enhancing equity in language development.

Assessments of children’s language environments

Assessments of early childhood learning environments serve multiple purposes—they describe the quality of language environments, help to identify best practices, evaluate programs and interventions, and may even guide public policy ( Lambert et al., 2006 ; Halle et al., 2010 ). Yet, there is ongoing debate as to which components of educational environments are most essential to assess and meaningfully link to children’s short- and long-term outcomes ( Layzer and Goodson, 2006 ; Burchinal, 2018 ). Historically, measures have been classified based on whether they assess structural characteristics of classrooms (e.g., adult-child ratios) or the process of teaching (e.g., teacher-child interactions; Mashburn et al., 2008 ). The most frequently administered assessments of children’s learning environments are observational in nature and typically offer a one-time general snapshot of both the physical space and interactions within the setting (see Halle et al., 2010 for a review). For example, the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale–Revised (ECERS–R) was designed as a global measure of classroom quality that assesses both structural and process aspects of the early childhood environment, including language reasoning ( Cryer et al., 2003 ). However, the ECERS–R only weakly correlates with children’s language outcomes ( r = 0.05; Brunsek et al., 2017 ), providing little evidence that using the ECERS – R for quality improvement purposes will result in the intended effects among children. Researchers have discovered that domain-specific measures focused on the quality of instruction and stimulation in specific content areas, like language and literacy, are more promising for guiding practice ( Burchinal et al., 2021 ). Even so, domain-specific measures of language environments remain less commonly assimilated into accountability systems than global assessments of quality ( Mitchell, 2016 ).

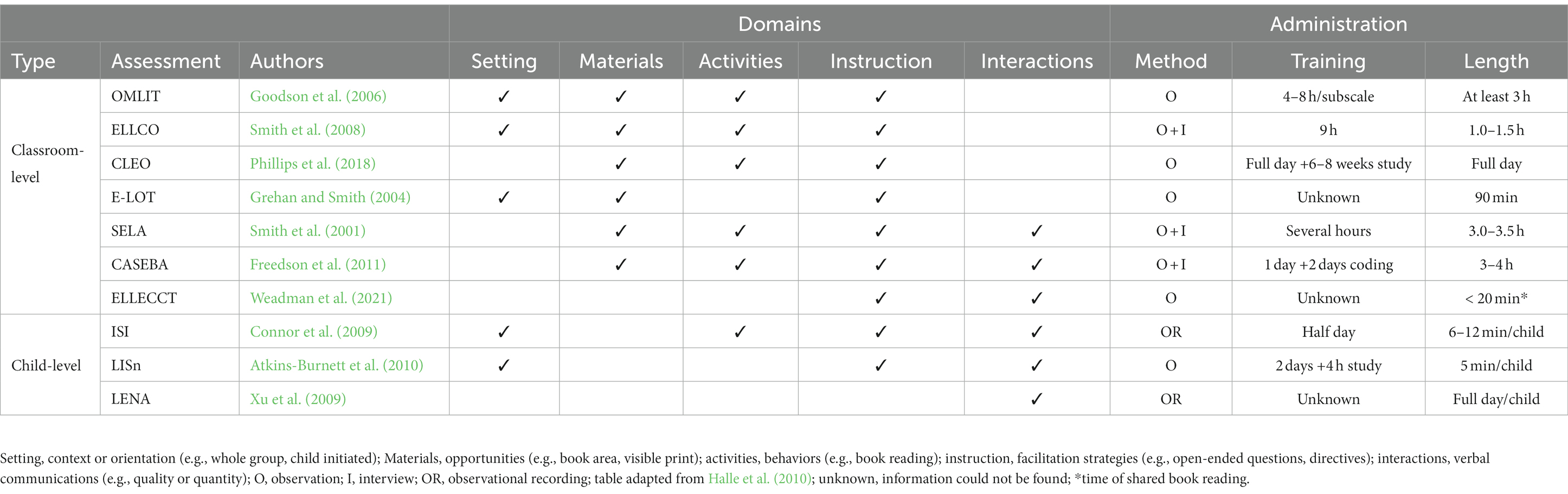

The early language environment is comprised of classroom features (e.g., activity settings), characteristics of teachers (e.g., pedagogical orientations), and interactions that support language development (e.g., input, responsivity, feedback; Smith and Dickinson, 1994 ; Wiggins et al., 2007 ). Research indicates that teacher communication-facilitating behaviors, those that create and sustain engagement in conversational turns, are the most powerful predictor of growth in children’s vocabulary from preschool to kindergarten ( Cabell et al., 2015 ; Justice et al., 2018 ). Indeed, teachers can bolster children’s language development by providing opportunities for children to speak and extending their responses ( Huttenlocher et al., 2002 ). Given that children ages 4–6 spend approximately 20–30% of their day learning in language and literacy domains, assessments that capture overall exposure to language and support for rich conversations are most promising for examining the features of environments that scaffold language development ( Pelatti et al., 2014 ). We recognize that other assessments have been developed to include an item, subscale, or dimension for measuring language environments [e.g., the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS); Pianta et al., 2008 , Teacher Behavior Rating Scale (TBRS); Landry et al., 2000 ] or features of teacher language input [e.g., Code for Interactive Recording of Children’s Learning Environments (CIRCLE); Atwater et al., 2009 ]. However, for the purpose of keeping our review brief and focused on the topic at hand, we have decided to only highlight domain-specific assessments of language/literacy. Therefore, we describe characteristics of frequently utilized domain-specific assessments of early childhood language environments in terms of their measurement properties. Importantly, we make the distinction between classroom-level assessments that provide information about the quality of instructional strategies teachers employ to engage all children in literacy activities, and child-level assessments that evaluate the quality and quantity of linguistic interactions individual children have with their teachers and peers.

Classroom-level assessments

Classroom-level assessments of early language environments measure the widespread opportunities that are available to support children’s language development. These assessments typically include multiple dimensions of the early language environment, including the context, materials and activities, and instructional practices (see Table 1 ). Given their focus on general routines and exercises, these assessments offer a macro view of the overall educational processes in classrooms and are predominantly observation based. Because of the risk of rater bias, administrators of classroom-level assessments may need a certain level of education, experience, and familiarity with early childhood development and learning, and must complete training on implementation procedures. However, the length of observation period that is necessary for obtaining reliable estimates can vary for classroom-level assessments. For example, the Early Language and Literacy Classroom Observation Pre-K assessment (ELLCO) assesses the degree to which children receive optimal support in language and literacy development ( Smith et al., 2008 ). Administrators need a strong background and understanding of children’s language and literacy development, classroom teaching experience, and must complete 9 h of training. Yet, the observation only takes approximately 1.0–1.5 h to administer. Alternatively, the Classroom Language Environment Observational Scale (CLEO) captures both implicit language supports and explicit language instruction ( Phillips et al., 2018 ). Administrators should hold a bachelor’s degree or higher and have experience teaching or observing early childhood classrooms. Training includes one full day of instruction plus 6–8 weeks of practice to establish reliability, and the CLEO observation lasts throughout the entire classroom day. Despite these slight variations, both the ELLCO and CLEO have demonstrated moderate to strong internal consistency ( Smith et al., 2008 ; Phillips et al., 2018 ).

Table 1 . Features of commonly utilized language environment assessments.

Child-level assessments

Child-level assessments of early language environments measure the language experiences that individual children are exposed to. These assessments typically focus on the quality and quantity of language interactions and may also capture the context of instruction or activities (see Table 1 ). Given their focus on relational components, these assessments offer a micro view of the child and their immediate exchanges with peers and adults. Because they predominantly rely on technological applications for observations, administrators of child-level assessments need less direct classroom experience or child development knowledge but may be required to complete training to master the software and coding procedures. There is less risk for rater bias, so reliable estimates can be obtained with shorter lengths of observation periods. For example, the Individualizing Student Instruction Classroom Observation System (ISI) is a video observation and coding system that assesses foundational and instructional elements of the language and literacy classroom environment ( Connor et al., 2009 ). The ISI requires one half day workshop to introduce the assessment and software, but it is most successful with ongoing coaching and professional development ( Connor and Morrison, 2016 ). Video observations on the ISI should record about 6–12 min per target child. Alternatively, the Language Environment Analysis System (LENA) is an audio recording device that quantifies the number of words heard, child vocalizations made, and conversational turn taking ( Xu et al., 2009 ). A basic training on how to use the device and audio processing software is required to purchase the LENA technology. Observations should be a minimum of 10 min long, but the LENA device will record up to 16 h. Both the ISI and LENA have demonstrated moderate to strong internal consistency ( Connor et al., 2009 ; Xu et al., 2009 ).

Research gaps and opportunities

Despite the wide range of assessment options, ongoing debates regarding the merit of observational methods (e.g., Purpura, 2019 ) have contributed to a lack of consensus regarding which aspects of language environments are most promising to assess. Since the formative Hart and Risley study (1995), total amount of language heard remains of interest to researchers (e.g., Sperry et al., 2019 ; Duncan et al., 2023 ). Indeed, frequent input of directed speech is important for building early vocabulary and language-learning processes ( Mahr and Edwards, 2018 ). However, there is also evidence indicating the quality of talk is of greater importance for children’s language development than purely the number of words heard ( Golinkoff et al., 2019 ; Anderson et al., 2021 ). Features of adult speech, such as lexical diversity and reciprocity, enable children to adopt word-learning mechanisms ( Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015 ; Newman et al., 2016 ). While the total amount of talk may be easier to code with language processing devices (e.g., the LENA), the quality of talk often requires more intensive researcher coding or subjective ratings of the experiences (e.g., Justice et al., 2018 ; Anderson et al., 2021 ). Possibly in between the pure counts of adult words heard and quality of language interactions would be the number of conversational turns children experience. These are typically defined as the instances of back and forth between the child and an adult. Conversational turns—usually conceptualized as quantitative metrics—have been linked to number of key child outcomes and brain development ( Gilkerson et al., 2018 ; Romeo et al., 2018 ), and have been shown to have larger effect sizes than pure numbers of adult words heard ( Duncan et al., 2023 ). Still, more research is needed that compares approaches to determine which provides the greatest return on investment both in terms of predictive power and information gained relative to effort expended.

Widespread adoption of language environment assessments has also, in part, been hindered by limited direct application in program evaluation research. As previously noted, interventions that focus on conversational interactions elicited by adults have the strongest potential to foster vocabulary development ( Dowdall et al., 2020 ). For example, dialogic reading has been found to encourage the use of a larger vocabulary, greater conceptual discussion, and longer sentences, which in turn, can impact the neural networks underlying language development ( Wasik et al., 2006 ; Hadley et al., 2022 ). Yet, evidence suggests that Head Start teachers rarely ask open-ended prompts or wait for responses during shared book reading ( Hindman et al., 2019 ). Language environment assessments can therefore be leveraged for the purpose of documenting existing processes and developing strategies for improving interactions. For instance, preliminary results indicate the LENA Start Program—designed to improve knowledge about the importance of the early language environment and provide tips for enriching the early language environment—can effectively increase the number of conversational turns between children and their parents through enhancing parental beliefs about the quality and quantity of language input ( Cunha et al., 2023 ). Therefore, researchers should evaluate whether strategically integrating language environment assessments into large-scale interventions increases awareness and positive attitudes about the importance of conversational turns and impacts children’s learning outcomes.

Relatedly, researchers can utilize language environment assessments to examine the ecological validity of language interventions and programs designed to improve the quality of early learning. For example, it is unclear whether effects of interventions delivered by trained research assistants transfer when administered by practitioners in real world situations ( Piasta et al., 2020a , b ). Indeed, a systematic review synthesizing results from early language interventions implemented by caregivers and parents of young children revealed that only half of studies observationally assessed changes in the quality of the language environment ( Greenwood et al., 2020 ). However, it is critical that language environment assessments are validated for this purpose and can detect discrete changes in all critical aspects of language environments that are known to predict language development, such as diversity and complexity of vocabulary, conversational turn-taking, verbal responsivity, and the supports for primary and secondary language learning ( Anderson et al., 2021 ). Thus, it is important to continue to develop and refine language environment assessments before administering them to examine the fidelity of implementing interventions or programs within authentic settings. Both efforts will provide evidence of the suitability of existing measures to detect targeted changes in language environments.

The effects of language interventions on child- and classroom-level processes have also been under-evaluated in the literature. Previous work indicates the classroom context is an important factor that influences the frequency of language stimulation practices ( Turnbull et al., 2009 ). For instance, in a meta-analysis of language interventions delivered to children between 4 and 9 years old, Rogde et al. (2019) found that studies with small-group interventions demonstrated larger effects on oral language skills than whole-classroom interventions or those involving larger groups. These results imply that high-quality interventions delivered to small groups can be beneficial for children’s language development. However, it is possible for more targeted language interventions to have spillover effects that enhance the larger classroom language environment, or impact future cohorts of students in the classroom ( Cilliers et al., 2022 ). Peers may also make significant contributions to one another’s language skills by serving as language models ( Perry et al., 2018 ; Washington-Nortey et al., 2022 ). Therefore, utilizing both child- and classroom-level language environments assessments to understand the potential for educational interventions to have a ripple or cascading effect may lead to significant discoveries regarding persistence and fadeout.

Language environment assessments are also somewhat limited in their ability to capture the breadth of classroom practices and strategies that promote language development. Beyond interactive or dialogic book reading, approaches involving speech and language therapists have been shown to be effective interventions for supporting language development ( Dobinson and Dockrell, 2021 ). Moreover, a meta-analysis revealed that language and literacy focused professional development in preschool had a medium to small effect on process quality and children’s phonological awareness ( Markussen-Brown et al., 2017 ). However, many language environment assessments are not intended to capture the processes targeted by professional development ( Justice et al., 2018 ), or the direct impacts of coaching or instruction provided by other specialized professionals. Therefore, a complementary line of work should center on the development and modification of language environment assessments to align with a broader conceptualization of what constitutes language supports.

Finally, there are critical gaps concerning the applicability of language environment assessments within diverse educational settings, including classrooms that serve dual language learners (DLLs), that must be filled ( White et al., 2020 ). For example, one analysis determined that most studies on the LENA system have been conducted with English-speaking children ( Ganek and Eriks-Brophy, 2018 ). A lack of representation is also apparent across language intervention research. In a systematic literature review, Walker et al. (2020) demonstrated that less than a quarter of language intervention studies in early education programs reported information about the race or ethnicity of children participating in the intervention, and only a quarter of samples included children who were DLLs. Further, they discovered that only 12% of studies reported on the racial/ethnic backgrounds of the early childhood personnel administering the interventions. Given that DLLs acquire their first and second language best when delivered instruction in their home language (e.g., Barnett et al., 2007 ; Partika et al., 2021 ), it is important that language environment assessments capture the instructional practices that facilitate first and second language development, such as the use of contextualized language ( Sawyer et al., 2018 ). Thus, research that addresses these shortcomings may also help to clarify how to appropriately incorporate language environment assessments into mainstream education.

Considerations for practice

In addition to the limitations of current research on early childhood language environments, there are practical constraints that may be impeding widespread uptake of assessments. Teachers may lack a fundamental understanding of what constitutes oral language and emergent literacy ( Weadman et al., 2023 ), as well as the skills to evaluate their own assessment practices and professional development needs ( Hill, 2017 ). These competencies are critical to develop because educator language and literacy knowledge has been shown to be correlated with more desirable classroom practices and children’s language outcomes ( Piasta et al., 2020a , b ). Researchers argue there is a need for consistent training on language and literacy content and the benefits of teacher talk for children’s language development in educator preparation programs ( Weadman et al., 2021 ). Moreover, ongoing professional development should focus on effective language facilitation and conversation strategies that preschool teachers can implement and should offer practice connecting this procedural knowledge to “in the moment” situations ( Mathers, 2021 ). For example, one study used the Emergent Literacy and Language Early Childhood Checklist for Teachers (ELLECCT) assessment to demonstrate how teachers often miss opportunities to target children’s phonological awareness during shared book reading ( Weadman et al., 2022 ). Therefore, early childhood language environment assessments may serve as a useful framework for training and professional development to help inform teachers of their use of practices associated with language development ( Franco et al., 2019 ).

Choosing an assessment that aligns with program goals and meets the needs of children and educators can, however, be a challenge in and of itself ( Zaslow et al., 2009 ). For instance, the ELLCO provides teachers with an understanding of the quality of the language and literacy environment of the classroom, while the LISn offers details on the quality of interactions between peers and adults, including the frequency and types of languages spoken. There are also tradeoffs according to the amount of information ascertained with reasonable effort. Classroom-level metrics can be captured by only observing and rating the teacher (i.e., the behaviors the teacher shows that would impact all children in the classroom). Conversely, child-level metrics would potentially better capture the unique experiences of children within the classroom, as opposed to assuming all children have the same experiences. Depending on whether the purpose of the assessment is to understand granular language engagement processes or general indices of the quality of language environment, some measures may be more sensitive to pick up discrete characteristics than others ( Justice et al., 2018 ). Thus, one consideration may be whether to administer classroom-level assessments to inform universal teaching practices ( Baker and Páez, 2018 ), or child-level assessments to provide guidance on individualized interventions for children ( Franco et al., 2019 ).

Additionally, it may be unrealistic for educational programs to accumulate the capital necessary for precise measurement and communication of language environment assessment findings. As described earlier, many assessments require extensive training and experience within early childhood classrooms, and programs may not have staff with relevant background to dedicate to this purpose ( Ackerman, 2019 ). For instance, the protocols for several assessments recommend administration by individuals with certain education levels or observation history. It may not be feasible for a teacher to administer individual assessments when they must also manage the classroom environment and facilitate children’s learning and development. Similarly, substantial training is often needed to become a reliable observer and maintain adherence to the procedures of language environment assessments ( Zaslow et al., 2009 ). Meeting these prerequisites can be costly and labor intensive, especially for programs that do not have a robust administrative infrastructure in place. The amount of support a program receives from their leadership to overcome these obstacles may be a critical factor in determining assessment participation ( Derrick-Mills et al., 2014 ).

Even after a language environment assessment has been chosen and implemented, programs may need specific resources to leverage the data to inform professional development. At a very basic level, human capacity is needed to analyze and translate data, which sometimes involves individuals who have pertinent technical skills to interpret statistics and graphs ( Isaacs et al., 2015 ). Programs may also need staff who can manage complex equipment, technology, and datasets. For example, child-level assessments like the LENA and ISI rely on hardware for collecting data and software for analyzing and/or storing data and developing reports ( Derrick-Mills et al., 2014 ). Beyond these logistical parameters, another challenge is effectively using the information to promote positive practices. One issue that can arise is teachers may assume they should emphasize only the discrete aspects of instruction addressed through the assessment itself rather than supporting broader integration ( Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2005 ). Thus, hiring coaches who have relevant funds of knowledge to make developmentally appropriate and evidence-based recommendations may be essential ( Ackerman, 2019 ). As Mathers (2022) contests, adoption of an observation tool itself cannot guarantee successful application without the focus on professional learning.

Another barrier that may be necessary to overcome is creating buy-in around language environment assessment use. For example, research suggests that teachers generally do not find kindergarten readiness assessments beneficial for instruction, and further, they view them as administratively burdensome and as taking time away from instruction, rather than contributing useful information for practice ( Schachter et al., 2020 ). Although there has been limited investigation into teacher perspectives on classroom environment assessments, one study found that administrators experience difficulties finding the time to conduct observations of classroom quality, but they report using the data for a variety of purposes, including individual teacher development ( Zweig et al., 2015 ). One framework that has been proposed for conceptualizing emergent literacy data practices is through examining: (1) how teachers prefer to gather data, (2) how they interpret data, (3) and how they use the data ( Schachter and Piasta, 2022 ). Given that educators play a critical role in supporting young children’s language development, it will be important for administrators to incentivize the implementation of language environment assessments and be prepared to engage in best practices around collecting and using data.