New Research

What Really Turned the Sahara Desert From a Green Oasis Into a Wasteland?

10,000 years ago, this iconic desert was unrecognizable. A new hypothesis suggests that humans may have tipped the balance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

Lorraine Boissoneault

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/94/f294516b-db3d-4f7b-9a60-ca3cd5f3d9b2/fbby1h_1.jpg)

When most people imagine an archetypal desert landscape—with its relentless sun, rippling sand and hidden oases—they often picture the Sahara. But 11,000 years ago, what we know today as the world’s largest hot desert would’ve been unrecognizable. The now-dessicated northern strip of Africa was once green and alive, pocked with lakes, rivers, grasslands and even forests. So where did all that water go?

Archaeologist David Wright has an idea: Maybe humans and their goats tipped the balance, kick-starting this dramatic ecological transformation. In a new study in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science , Wright set out to argue that humans could be the answer to a question that has plagued archaeologists and paleoecologists for years.

The Sahara has long been subject to periodic bouts of humidity and aridity. These fluctuations are caused by slight wobbles in the tilt of the Earth’s orbital axis, which in turn changes the angle at which solar radiation penetrates the atmosphere. At repeated intervals throughout Earth’s history , there’s been more energy pouring in from the sun during the West African monsoon season, and during those times—known as African Humid Periods—much more rain comes down over north Africa.

With more rain, the region gets more greenery and rivers and lakes. All this has been known for decades. But between 8,000 and 4,500 years ago, something strange happened: The transition from humid to dry happened far more rapidly in some areas than could be explained by the orbital precession alone, resulting in the Sahara Desert as we know it today. “Scientists usually call it ‘poor parameterization’ of the data,” Wright said by email. “Which is to say that we have no idea what we’re missing here—but something’s wrong.”

As Wright pored the archaeological and environmental data (mostly sediment cores and pollen records, all dated to the same time period), he noticed what seemed like a pattern. Wherever the archaeological record showed the presence of “pastoralists”—humans with their domesticated animals—there was a corresponding change in the types and variety of plants. It was as if, every time humans and their goats and cattle hopscotched across the grasslands, they had turned everything to scrub and desert in their wake.

Wright thinks this is exactly what happened. “By overgrazing the grasses, they were reducing the amount of atmospheric moisture—plants give off moisture, which produces clouds—and enhancing albedo,” Wright said. He suggests this may have triggered the end of the humid period more abruptly than can be explained by the orbital changes. These nomadic humans also may have used fire as a land management tool, which would have exacerbated the speed at which the desert took hold.

It’s important to note that the green Sahara always would’ve turned back into a desert even without humans doing anything—that’s just how Earth’s orbit works, says geologist Jessica Tierney, an associate professor of geoscience at the University of Arizona. Moreover, according to Tierney, we don’t necessarily need humans to explain the abruptness of the transition from green to desert.

Instead, the culprits might be regular old vegetation feedbacks and changes in the amount of dust. “At first you have this slow change in the Earth’s orbit,” Tierney explains. “As that’s happening, the West African monsoon is going to get a little bit weaker. Slowly you’ll degrade the landscape, switching from desert to vegetation. And then at some point you pass the tipping point where change accelerates.”

Tierney adds that it’s hard to know what triggered the cascade in the system, because everything is so closely intertwined. During the last humid period, the Sahara was filled with hunter-gatherers. As the orbit slowly changed and less rain fell, humans would have needed to domesticate animals, like cattle and goats , for sustenance. “It could be the climate was pushing people to herd cattle, or the overgrazing practices accelerated denudation [of foliage],” Tierney says.

Which came first? It’s hard to say with evidence we have now. “The question is: How do we test this hypothesis?” she says. “How do we isolate the climatically driven changes from the role of humans? It’s a bit of a chicken and an egg problem.” Wright, too, cautions that right now we have evidence only for correlation, not causation.

But Tierney is also intrigued by Wright’s research, and agrees with him that much more research needs to be done to answer these questions.

“We need to drill down into the dried-up lake beds that are scattered around the Sahara and look at the pollen and seed data and then match that to the archaeological datasets,” Wright said. “With enough correlations, we may be able to more definitively develop a theory of why the pace of climate change at the end of the AHP doesn’t match orbital timescales and is irregular across northern Africa.”

Tierney suggests researchers could use mathematical models that compare the impact hunter-gatherers would have on the environment versus that of pastoralists herding animals. For such models it would be necessary to have some idea of how many people lived in the Sahara at the time, but Tierney is sure there were more people in the region than there are today, excepting coastal urban areas.

While the shifts between a green Sahara and a desert do constitute a type of climate change, it’s important to understand that the mechanism differs from what we think of as anthropogenic (human-made) climate change today, which is largely driven by rising levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Still, that doesn’t mean these studies can’t help us understand the impact humans are having on the environment now.

“It’s definitely important,” Tierney says. “Understanding the way those feedback (loops) work could improve our ability to predict changes for vulnerable arid and semi-arid regions.”

Wright sees an even broader message in this type of study. “Humans don’t exist in ecological vacuums,” he said. “We are a keystone species and, as such, we make massive impacts on the entire ecological complexion of the Earth. Some of these can be good for us, but some have really threatened the long-term sustainability of the Earth.”

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

Lorraine Boissoneault | | READ MORE

Lorraine Boissoneault is a contributing writer to SmithsonianMag.com covering history and archaeology. She has previously written for The Atlantic, Salon, Nautilus and others. She is also the author of The Last Voyageurs: Retracing La Salle's Journey Across America. Website: http://www.lboissoneault.com/

Sand dunes show the increasing desertification of the Tibetan Plateau, as land dries out and vegetation cover vanishes due to human activity.

- ENVIRONMENT

Desertification, explained

Humans are driving the transformation of drylands into desert on an unprecedented scale around the world, with serious consequences. But there are solutions.

As global temperatures rise and the human population expands, more of the planet is vulnerable to desertification, the permanent degradation of land that was once arable.

While interpretations of the term desertification vary, the concern centers on human-caused land degradation in areas with low or variable rainfall known as drylands: arid, semi-arid, and sub-humid lands . These drylands account for more than 40 percent of the world's terrestrial surface area.

While land degradation has occurred throughout history, the pace has accelerated, reaching 30 to 35 times the historical rate, according to the United Nations . This degradation tends to be driven by a number of factors, including urbanization , mining, farming, and ranching. In the course of these activities, trees and other vegetation are cleared away , animal hooves pound the dirt, and crops deplete nutrients in the soil. Climate change also plays a significant role, increasing the risk of drought .

All of this contributes to soil erosion and an inability for the land to retain water or regrow plants. About 2 billion people live on the drylands that are vulnerable to desertification, which could displace an estimated 50 million people by 2030.

Where is desertification happening, and why?

The risk of desertification is widespread and spans more than 100 countries , hitting some of the poorest and most vulnerable populations the hardest, since subsistence farming is common across many of the affected regions.

More than 75 percent of Earth's land area is already degraded, according to the European Commission's World Atlas of Desertification , and more than 90 percent could become degraded by 2050. The commission's Joint Research Centre found that a total area half of the size of the European Union (1.61 million square miles, or 4.18 million square kilometers) is degraded annually, with Africa and Asia being the most affected.

The drivers of land degradation vary with different locations, and causes often overlap with each other. In the regions of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan surrounding the Aral Sea , excessive use of water for agricultural irrigation has been a primary culprit in causing the sea to shrink , leaving behind a saline desert. And in Africa's Sahel region , bordered by the Sahara Desert to the north and savannas to the south, population growth has caused an increase in wood harvesting, illegal farming, and land-clearing for housing, among other changes.

The prospect of climate change and warmer average temperatures could amplify these effects. The Mediterranean region would experience a drastic transformation with warming of 2 degrees Celsius, according to one study , with all of southern Spain becoming desert. Another recent study found that the same level of warming would result in "aridification," or drying out, of up to 30 percent of Earth's land surface.

A herder family tends pastures beside a growing desert.

When land becomes desert, its ability to support surrounding populations of people and animals declines sharply. Food often doesn't grow, water can't be collected, and habitats shift. This often produces several human health problems that range from malnutrition, respiratory disease caused by dusty air, and other diseases stemming from a lack of clean water.

Desertification solutions

In 1994, the United Nations established the Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), through which 122 countries have committed to Land Degradation Neutrality targets, similar to the way countries in the climate Paris Agreement have agreed to targets for reducing carbon pollution. These efforts involve working with farmers to safeguard arable land, repairing degraded land, and managing water supplies more effectively.

The UNCCD has also promoted the Great Green Wall Initiative , an effort to restore 386,000 square miles (100 million hectares) across 20 countries in Africa by 2030. A similar effort is underway in northern China , with the government planting trees along the border of the Gobi desert to prevent it from expanding as farming, livestock grazing , and urbanization , along with climate change, removed buffering vegetation.

However, the results for these types of restoration efforts so far have been mixed. One type of mesquite tree planted in East Africa to buffer against desertification has proved to be invasive and problematic . The Great Green Wall initiative in Africa has evolved away from the idea of simply planting trees and toward the idea of " re-greening ," or supporting small farmers in managing land to maximize water harvesting (via stone barriers that decrease water runoff, for example) and nurture natural regrowth of trees and vegetation.

"The absolute number of farmers in these [at-risk rural] regions is so large that even simple and inexpensive interventions can have regional impacts," write the authors of the World Atlas of Desertification, noting that more than 80 percent of the world's farms are managed by individual households, primarily in Africa and Asia. "Smallholders are now seen as part of the solution of land degradation rather than a main problem, which was a prevailing view of the past."

LIMITED TIME OFFER

Get a FREE tote featuring 1 of 7 ICONIC PLACES OF THE WORLD

Related Topics

- AGRICULTURE

- DEFORESTATION

You May Also Like

They planted a forest at the edge of the desert. From there it got complicated.

Forests are reeling from climate change—but the future isn’t lost

Why forests are our best chance for survival in a warming world

How to become an ‘arbornaut’

Palm oil is unavoidable. Can it be sustainable?

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- The Big Idea

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Desertification

Charney's hypothesis

There is a controversy about the advance of deserts in the world (1). There is a widespread belief that the Sahara desert is advancing into the Sahel region, for instance. The Sahel is a narrow band of West Africa between 15 -18 ° N, between the Sahara to the north and savannah (grass and open forest) and equatorial forest to the south. It extends from Senegal at the coast at about 15 ° W, across Mali and Niger, to about 15 ° E. It receives rainfall during a short but active wet season, from late June to mid September. It is covered by grassland and supports a pasture-based society which traditionally moved meridionally following the rains. Its northern limit may be defined by the 200 mm/a isohyet.

Is the Sahara extending into the Sahel? And if so, is this because of fluctuations of rainfall (total amount, rainfall intensity, duration of wet season, …) or is it largely the result of human activities, such as overgrazing or the removal of trees for firewood? There are also the questions: Do deserts create droughts? Do droughts create deserts? In other words, is there a positive climate feedback, which accelerates land degradation? A now classic paper by Jules Charney in 1975 (2) speculated that overgrazing in the Sahel leads to less vegetation, which raises the ground’s albedo, so that less solar radiation is absorbed and the Earth’s surface becomes cooler. It should be noted that the atmosphere above the Sahara experiences continues radiative cooling, because the dry air, free of clouds, absorbs very little of the longwave radiation upwelling from the ground. This radiative cooling is naturally compensated by subsidence heating, and the subsidence sustains the dry air, cloudlessness, and arid surface conditions. According Charney, overgrazing would enhance the radiative loss, which would foster subsidence within the troposphere, leading to drier conditions in the Sahel, and therefore less plant growth during the wet season. Less vegetation means a higher albedo. So we have positive feedback and a self-aggravating process, culminating in desertification, a process of land degradation that destroys its productivity. Charney’s hypothesis was supported by experiments with a very simple GCM, in which he changed the surface albedo from 20% to 30% (3).

The problem of overgrazing in the Sahel is as acute now as it was in the 1960's, yet there is no clear rainfall trend in the Sahel. The period 1930-'60 was slightly wetter than 1960-'90 in most parts of the Sahel. More significant than any trend is the occurrence of dry and wet periods, each lasting several years. The Sahel enjoyed a notably wet decade in the 1950’s, which was followed by a drought in the 70’s and 80’s (1). However, land productivity was fully recovered around 1990. So Charney's hypothesis cannot be confirmed.

To reject Charney's hypothesis, one needs to examine whether the albedo has really increased in the Sahel. Satellite-estimated albedo of the Sahel between 1983-1988 was about 35% in (dry) January and 31% in (wet) July, a difference of about 4%. The seasonal variation greatly exceeded any overall change during the period. This points to there being no irreversible change towards desert. It is concluded that the formation of desert is not a single self-aggravating process, but is complex, reflecting changes of both climate and human activities. There may be incomplete recovery after a dry period, or changes in the composition of the vegetation.

Desertification trends are evaluated by means of the ‘normalised difference vegetation index’ (NDVI). This index, based on satellite data, quantifies the amount of vegetation (1). It is a figure for the ‘green-ness’ of the surface, the ratio of the measured reflectances of red light (i.e. 0.55-0.68 micron wavelength) and near-infra-red (0.73-1.1) in solar radiation. NDVI is strongly correlated with the biological productivity of an area. In the Sahel there is close agreement of the shifts of NDVI and rainfall boundaries during 1980 - 1995, i.e. the NDVI/rainfall relationship remained about constant. In other words, there was no progressive ‘march’ of desert over more fertile areas, no one-way ratchet effect due to deserts causing droughts.

A question related to the question about deserts causing drought, is that of large lakes inducing rain. Nicholson et al. (1) mentioned proposals to flood the Kalahari desert of Botswana to increase the rainfall regionally. The topic was discussed indirectly in Notes 10.I and 10.J, where reasons are given for expecting no influence of forestation on rainfall, unless done over large areas; even then, the enhanced rainfall is insufficient to support the manmade forest.

A separate effect of desertification, apart from any possible influence on rainfall, is an increase of soil erosion and dust storms (4), as shown in Fig 1 . This shows the close relationship between rainfall and dust.

Fig 1 . The frequency of dust storms at Gao (in the Sahel), compared with annual rainfall anomalies (from (1), after (4)). The anomaly unit is the regionally averaged departure from the long-term mean, divided by the standard deviation. The dust occurrence is expressed in terms of the number of days when there is dust haze.

References

(1) Nicholson, S.E., C.J. Tucker and M.B. Ba 1998. Desertification, drought and surface vegetation: an example from the West African Sahel. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 79 , 815-29.

(2) Charney, J.G. 1975. Dynamics of deserts and drought in Sahel. Quart. J. Royal Meteor. Soc, 101 , 193-202.

(3) Xue, Y. and J. Shukla 1993. The influence of land surface properties on Sahel climate. J. Climate, 6 , 2232-45.

(4) N’Tchayi, M.G., J.J. Bertrand and S.E. Nicholson 1997. The diurnal and seasonal cycles of desert dust over Africa north of the equator. J. Appl. Meteor. 36 , 868-82.

Desertification, land degradation and drought

Related sdgs, protect, restore and promote sustainable use ....

Description

Publications.

Paragraph 33 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development focuses on the linkage between sustainable management of the planet’s natural resources and social and economic development as well as on “strengthen cooperation on desertification, dust storms, land degradation and drought and promote resilience and disaster risk reduction” .

Sustainable Development Goal 15 of the 2030 Agenda aims to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss” .

The economic and social significance of a good land management, including soil and its contribution to economic growth and social progress is recognized in paragraph 205 of the Future We Want. In this context, Member States express their concern on the challenges posed to sustainable development by desertification, land degradation and drought, especially for Africa, LDCs and LLDCs. At the same time, Member States highlight the need to take action at national, regional and international level to reverse land degradation, catalyse financial resources, from both private and public donors and implement both the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and its 10- Year Strategic Plan and Framework (2008-2018).

Furthermore, in paragraphs 207 and 208 of the Future We Want, Member States encourage and recognize the importance of partnerships and initiatives for the safeguarding of land resources, further development and implementation of scientifically based, sound and socially inclusive methods and indicators for monitoring and assessing the extent of desertification, land degradation and drought. The relevance of efforts underway to promote scientific research and strengthen the scientific base of activities to address desertification and drought under the UNCCD is also addressed.

Combating desertification and drought were discussed by the Commission on Sustainable Development in several sessions. In the framework of the Commission's multi-year work programme, CSD 16-17 focused, respectively in 2008 and 2009, on desertification and drought along with the interrelated issues of Land, Agriculture, Rural development and Africa.

In accordance with its multi-year programme of work, CSD-8 in 2000 reviewed integrated planning and management of land resources as its sectoral theme. In its decision 8/3 on integrated planning and management of land resources, the Commission on Sustainable Development noted the importance of addressing sustainable development through a holistic approach, such as ecosystem management, in order to meet the priority challenges of desertification and drought, sustainable mountain development, prevention and mitigation of land degradation, coastal zones, deforestation, climate change, rural and urban land use, urban growth and conservation of biological diversity.

The sectoral cluster of land, desertification, forests and biodiversity, as well as mountains (chapters 10-13 and 15 of Agenda 21) were considered by CSD-3 in 1995 and again at the five-year review in 1997.

The UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) called upon the United Nations General Assembly to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INCD) to prepare, by June 1994, an international convention to combat desertification in those countries experiencing serious drought and/or desertification, particularly in Africa. The Convention was adopted in Paris on 17 June 1994 and opened for signature there on 14-15 October 1994. It entered into force on 26 December 1996.

Deserts are among the "fragile ecosystems" addressed by Agenda 21, and "combating desertification and drought" is the subject of Chapter 12. Desertification includes land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub humid areas resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities. Desertification affects as much as one-sixth of the world's population, seventy percent of all drylands, and one-quarter of the total land area of the world. It results in widespread poverty as well as in the degradation of billion hectares of rangeland and cropland.

Integrated planning and management of land resources is the subject of chapter 10 of Agenda 21, which deals with the cross-sectoral aspects of decision-making for the sustainable use and development of natural resources, including the soils, minerals, water and biota that land comprises. This broad integrative view of land resources, which are essential for life-support systems and the productive capacity of the environment, is the basis of Agenda 21's and the Commission on Sustainable Development's consideration of land issues.

Expanding human requirements and economic activities are placing ever increasing pressures on land resources, creating competition and conflicts and resulting in suboptimal use of resources. By examining all uses of land in an integrated manner, it makes it possible to minimize conflicts, to make the most efficient trade-offs and to link social and economic development with environmental protection and enhancement, thus helping to achieve the objectives of sustainable development. (Agenda 21, para 10.1) The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is the task manager for chapter 10 of Agenda 21.

Publication - Making Peace with Nature A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies

Part I of the report addresses how the current expansive mode of development degrades and exceeds the Earth’s finite capacity to sustain human well-being. The world is failing to meet most of its commitments to limit environmental damage and this increasingly threatens the achievement of the Sustain...

Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom, We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for su...

“Combating desertification/land degradation and drought for poverty reduction and sustainable development: the contribution of science, technology, traditional knowledge and practices” Preliminary conclusions

The effects of demographic pressure and unsustainable land management practices on land degradation and desertification are being exacerbated worldwide due to the effects of climate change, which include (but are not limited to) changing rainfall patterns, increased frequency and intensity of drough...

Climate change and desertification: Anticipating, assessing & adapting to future change in drylands - Impulse Report

Climate change and desertification: Anticipating, assessing and adapting to future change in drylands The ‘Impulse report’, a preparatory document for the Third Scientific Conference of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), to be held in Cancún Mexico this 9-12 March 2015 has been pub...

Transforming Land Management Globally

Combatting land degradation is a key component of the post 2015 development agenda. The linkage between land degradation and other global environmental challenges is more recognized than ever before. We must leverage the increasing attention being given to land to further promote sustainable land ma...

WHITE PAPER II: Costs and Benefits of Policies and Practices Addressing Land Degradation and Drought in the Drylands

- Drylands are complex social-ecological systems, characterized by non-linearity of causation, complex feedback loops within and between the many different social, ecological, and economic entities, and potential of regime shifts to alternative stable states as a result of thresholds. As such, dryla...

Brazil Low-carbon - Country Case Study

In order to mitigate the impacts of climate change, the world must drastically reduce global GHG emissions in the coming decades. According to the IPCC, to prevent the global mean temperature from rising over 3oC, atmospheric GHG concentrations must be stabilized at 550 ppm. By 2030, this will requi...

Sustainable Development Innovation Briefs: Issue 7

The contribution of sustainable agriculture and land management to sustainable development....

Sustainable land use for the 21st century

This study is part of the Sustainable Development in the 21st century (SD21) project. The project is implemented by the Division for Sustainable Development of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and funded by the European Commission - Directorate-General for Environment - T...

Trends in Sustainable Development 2008-2009

This report highlights key developments and recent trends in agriculture, rural development, land, desertification and drought, five of the six themes being considered by the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) at its 16th and 17th sessions (2008-2009). A separate Trends Report addresses de...

Sustainable Development Innovation Briefs: Issue 8

Foreign land purchases for agriculture: what impact on sustainable development? Private investors and governments have recently stepped up foreign investment in farmlandin the form of purchases or long-term lease of large tracks of arable land, notably in Africa. This brief examines the implication...

Expert Group Meeting on SDG 15 (Life on land) and its interlinkages with other SDGs

In preparation for the review of SDG 15— “Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”—and its role in advancing sustainable development across the 2030 Ag

Expert Group Meetings on 2022 HLPF Thematic Review

The theme of the 2022 high-level political forum on sustainable development (HLPF) is “Building back better from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) while advancing the full implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. The 2022 HLPF will have an in-depth rev

UNEP Environment Assembly

United nations forum on forests, fourteenth meeting of the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity (cop14), expert group meeting on sustainable development goal 15: progress and prospects.

In preparation for the 2018 HLPF, the Division for Sustainable Development Goals of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DSDG-DESA) organized an Expert Group Meeting (EGM) on SDG 15 and its role in advancing sustainable development through implementation of the 2030 Agenda, in partnership

IYS Closure Event

The World Soil Day 2015 will host the 'closure' event of the International Year of Soils. It will also coincide with the launch of the first 'Status of the World Soil Resources Report'.

21st Session of the Conference of the Parties and 11th Session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol- UNFCCC COP 21/ CMP 11

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or “UNFCCC”, was adopted during the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992. It entered into force on 21 March 1994 and has been ratified by 196 States, which constitute the “Parties” to the Convention – its stakeholders. This Framework Conven

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) - 12th Session

The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) will host its Twelfth Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP12) in Ankara, Turkey, from 12 October to 23 October 2015. The conference will take place at the Congresium Ankara-ATO International Convention and Exhibition Centre. De

Third Plenary Assembly of the Global Soil Partnership

The Food and Agriculture Organization extends an invitation to attend the Third Plenary Assembly of the Global Soil Partnership (GSP) to be held from 22 to 24 June 2015 at FAO headquarters in Rome. The opening meeting will commence at 09.00 hours on Monday 22 June. The Provisional Agenda is attach

- January 2015 SDG 15 - Desertification SDG 15 aims at protecting, restoring and promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainable manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss. Target 15.3 in particular reads to achieve "by 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world".

- January 2012 Future We Want (Para 205-209) The economic and social significance of a good land management, including soil and its contribution to economic growth and social progress is also recognized in paragraph 205 of the Future We Want. In this context, Member States express their concern on the challenges posed to sustainable development by desertification, land degradation and drought, especially for Africa, LDCs and LLDCs. At the same time, Member States highlight the need to take action at national, regional and international level to reverse land degradation, catalyze financial resources, from both private and public donors and implement both the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and its 10- Year Strategic Plan and Framework (2008-2018). Furthermore, in paragraphs 207 and 208 of the Future We Want, Member States encourage and recognize the importance of partnerships and initiatives for the safeguarding of land resources, further development and implementation of scientifically based, sound and socially inclusive methods and indicators for monitoring and assessing the extent of desertification, land degradation and drought. The relevance of efforts underway to promote scientific research and strengthen the scientific base of activities to address desertification and drought under the UNCCD is also taken into account by paragraph 208.

- January 2010 UN Decade on Desertification Launched by the General Assembly with the adoption of Resolution A/RES/64/201, the UN Decade for Deserts and the Fight Against Desertification was designed to address the Parties'concern about the worsening of the situation of desertification and its negative impact on the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. The Decade started in January 2010 and will end in December 2020 with the aim of promoting action ensuring the protection of dry-lands.

- January 2008 CSD-16 (Chap.2 C,D,E) CSD-16 focused on the thematic cluster of agriculture, rural development, land, drought, desertification and Africa.

- January 2006 Int. Year of Deserts and Desertification The International Year of Deserts and Desertification was launched to highlight the threat represented by the advancing of deserts and the loss it may cause to biodiversity. Through this International Year, the UN aimed at raising public awareness on this issue and at reversing the trend of desertification, setting the world on a safer and more sustainable path of development.

- January 2000 CSD-8 (Chap. 4) As decided at UNGASS, the economic, sectoral and cross-sectoral themes under consideration for CSD-8 were sustainable agriculture and land management, integrating planning and management of land resources and financial resources, trade and investment and economic growth.CSD-6 to CSD-9 annually gathered at the UN Headquarters for spring meetings. Discussions at each session opened with multi-stakeholder dialogues, in which major groups were invited to make opening statements on selected themes followed by a dialogue with government representatives.

- January 1996 UNCCD The only legally binding international agreement connecting environment and development to sustainable land management, UNCCD addresses the arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas, known as the drylands, where some of the most vulnerable ecosystems and peoples can be found. In 2007 the 10-Year Strategy of the UNCCD (2008-2018) was adopted and on that occasion, parties to the Convention further specified their goals: "to forge a global partnership to reverse and prevent desertification/land degradation and to mitigate the effects of drought in affected areas in order to support poverty reduction and environmental sustainability". The Convention was adopted in Paris on 17 June 1994 and entered into force on 26 December 1996, 90 days after the 50th ratification was received. 194 countries and the European Union are Parties as at April 2015.

- January 1992 Agenda 21 (Chap. 10 and 12) Integrated planning and management of land resources is the subject of chapter 10 of Agenda 21, which deals with the cross-sectoral aspects of decision-making for the sustainable use and development of natural resources, including the soils, minerals and water that land comprises. Included in the sections devoted to the management of fragile ecosystems, chapter 12 has focused on combating desertification and droughts. The priority to keep in mind while combating desertification is identified by Chap 12.3 in the need to implement "preventive measures for lands that are not yet degraded, or which are only slightly degraded. However, the severely degraded areas should not be neglected. In combating desertification and drought, the participation of local communities, rural organizations, national Governments, non-governmental organizations and international and regional organizations is essential".

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Desertification in the Karoo

Driving eastward out of the Cape, through the winelands around Paarl and away from the region of winter rainfall the landscape becomes arid. Sheep grazing replaces the vineyards except in irrigated areas where fruits can still be grown.

This is a hostile landscape to which early European colonisers originally brought cattle, but moved-on in search of better pastures. The settlers learned to live with the periodic droughts and unfamiliar wild animals, building homesteads near sources of water, replacing cattle with hardier sheep, and establishing towns like Graaf Reinet in the 1820s.

Sheep-ranges were fenced and protected and jackal predators eradicated. As the control of nature increased, so did populations of sheep.

The great semi-arid area stretching eastwards from the Cape is called the Karoo. Typically, it is flat dry shrubland with grass-growth restricted to the moistness of the occasional mountain ranges. Rainfall is sporadic, less than 500 mm a year, in some places a great deal less. Periods of drought last for several years, affecting the region and its plant growth. Notable droughts occurred in the periods 1919-31, 1944-49 and 1962-73. Since 1974 has been a relatively wet period.

Karoo lamb is succulent herby meat, much appreciated on the braais, or barbecues, of South Africa, but the vast region of the Karoo produces little else of note. In a time of farm incomes that are falling, there is much talk of developing game parks and attracting overseas tourists to provide a living.

White farmers making a precarious living from sheep in the Karoo. They feel marginalised in a country with politically different and largely urban priorities.

Of great concern to the farmers is the suggestion that the landscape is becoming more hostile to farming, and eventually unsuitable for livestock.

First suggested by a French-forester named Aubréville in the late nineteenth century, and forcibly advocated in South Africa by J.P.H.Acocks in the 1950s, the term 'desertification' implies the advance of desert-like conditions - a growing aridification. Acocks described a desert margin advancing northeastwards towards Pretoria - a powerful image since this is the seat of South African government.

In the days when public values were Boer farming values, desertification was seen as a threat to rural livelihoods and a cause for concern. Government spent large sums of money subsidising farming systems that arguably, as in other parts of the world, were unsustainable.

Sheep prices were high, and grants were available for fencing, water conservation and anti-erosion measures such as dams. These subsidies and measures further enabled farmers to overstock with sheep.

Nowadays, there is an additional cause for concern. Desertification implies soil erosion. Soils are washed into streams and eventually silt-up reservoirs. South Africa has a water resource problem and loss of water storage in reservoirs contributes to the scarcity.

The concept of desertification has been the subject of fierce debate. The vegetation of the Karoo has changed from a mix of livestock-edible grasses and shrubs, to undesirable shrubs which are less palatable to sheep.

One of the problems with the loss of grasses is that a patchy shrub-dominated landscape has much bare ground, causing increased potential for rainfall runoff and soil erosion. Controversy rages around why these changes have occurred. Is it climate-induced, detrimental human impact, climate and human impact, or just a natural process in marginal-arid areas of the world?

Semi-arid areas are notoriously sensitive to climate variability and the Karoo has had many droughts, but much of the Karoo has also had very high numbers of sheep, until fairly recently. Overgrazing is recognised worldwide as an impact on vegetation that leads to the land degradation that is soil erosion. Together with occasional droughts, the Karoos dense sheep populations could explain the cause of desertification in the region.

If drought alone were the cause of the vegetation change, then relating change to cycles of drought would test the hypothesis. Recent research confirms that the vegetation type has changed, but it does not provide reliable dates for the changes.

The landscape of the Karoo shows evidence of desertification in that systems of deep gullies and crazy-paved badlands scar much of the landscape. These are likely to have formed when vegetation decline produced bare ground through loss of grasses that enables soil erosion by rainfall and runoff.

Dating the gullies and badlands is crucial to explaining the causes of desertification in the Karoo.

In the Sneeuberg uplands, gully systems developed when the first Europeans moved through the area in the early nineteenth century. At that time, cattle drank in streams that now lie at the bottom of six metre deep gullies, and hippopotami wallowed in pools that no longer exist. The gullies have continued to deepen to the extent that small dams built in the 1950s quickly filled with sediment.

Fences built on flatlands in the 1930s now cross deep gullies. Similarly, the badlands seem rather recent in age. During present-day storms, considerable erosion occurs. Once formed the badlands appear very difficult to revegetate, even with greatly reduced sheep numbers.

The desertified areas of the Karoo, gullied and lacking vegetation or growing unpalatable shrubs, seem likely to be a product of dense sheep populations in the 100 years from 1860 to 1960.

If this is the case, the desertification of the Karoo is an indictment of the introduction and development of European farming systems in fragile semi-arid landscapes that are subject to drought. Similar stories are told in the arid farming regions of western USA, Australia and New Zealand, and the controversy over the causes remain.

- Desertification

- Climate crisis

Most viewed

What is a scientific hypothesis?

It's the initial building block in the scientific method.

Hypothesis basics

What makes a hypothesis testable.

- Types of hypotheses

- Hypothesis versus theory

Additional resources

Bibliography.

A scientific hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for a phenomenon in the natural world. It's the initial building block in the scientific method . Many describe it as an "educated guess" based on prior knowledge and observation. While this is true, a hypothesis is more informed than a guess. While an "educated guess" suggests a random prediction based on a person's expertise, developing a hypothesis requires active observation and background research.

The basic idea of a hypothesis is that there is no predetermined outcome. For a solution to be termed a scientific hypothesis, it has to be an idea that can be supported or refuted through carefully crafted experimentation or observation. This concept, called falsifiability and testability, was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper in his famous book "The Logic of Scientific Discovery" (Routledge, 1959).

A key function of a hypothesis is to derive predictions about the results of future experiments and then perform those experiments to see whether they support the predictions.

A hypothesis is usually written in the form of an if-then statement, which gives a possibility (if) and explains what may happen because of the possibility (then). The statement could also include "may," according to California State University, Bakersfield .

Here are some examples of hypothesis statements:

- If garlic repels fleas, then a dog that is given garlic every day will not get fleas.

- If sugar causes cavities, then people who eat a lot of candy may be more prone to cavities.

- If ultraviolet light can damage the eyes, then maybe this light can cause blindness.

A useful hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable. That means that it should be possible to prove it wrong. A theory that can't be proved wrong is nonscientific, according to Karl Popper's 1963 book " Conjectures and Refutations ."

An example of an untestable statement is, "Dogs are better than cats." That's because the definition of "better" is vague and subjective. However, an untestable statement can be reworded to make it testable. For example, the previous statement could be changed to this: "Owning a dog is associated with higher levels of physical fitness than owning a cat." With this statement, the researcher can take measures of physical fitness from dog and cat owners and compare the two.

Types of scientific hypotheses

In an experiment, researchers generally state their hypotheses in two ways. The null hypothesis predicts that there will be no relationship between the variables tested, or no difference between the experimental groups. The alternative hypothesis predicts the opposite: that there will be a difference between the experimental groups. This is usually the hypothesis scientists are most interested in, according to the University of Miami .

For example, a null hypothesis might state, "There will be no difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't." The alternative hypothesis would state, "There will be a difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't."

If the results of the experiment show a relationship between the variables, then the null hypothesis has been rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, according to the book " Research Methods in Psychology " (BCcampus, 2015).

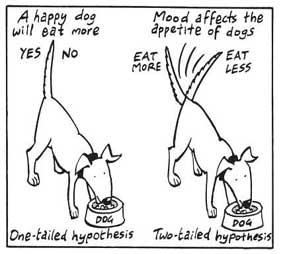

There are other ways to describe an alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis above does not specify a direction of the effect, only that there will be a difference between the two groups. That type of prediction is called a two-tailed hypothesis. If a hypothesis specifies a certain direction — for example, that people who take a protein supplement will gain more muscle than people who don't — it is called a one-tailed hypothesis, according to William M. K. Trochim , a professor of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University.

Sometimes, errors take place during an experiment. These errors can happen in one of two ways. A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it is true. This is also known as a false positive. A type II error occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false. This is also known as a false negative, according to the University of California, Berkeley .

A hypothesis can be rejected or modified, but it can never be proved correct 100% of the time. For example, a scientist can form a hypothesis stating that if a certain type of tomato has a gene for red pigment, that type of tomato will be red. During research, the scientist then finds that each tomato of this type is red. Though the findings confirm the hypothesis, there may be a tomato of that type somewhere in the world that isn't red. Thus, the hypothesis is true, but it may not be true 100% of the time.

Scientific theory vs. scientific hypothesis

The best hypotheses are simple. They deal with a relatively narrow set of phenomena. But theories are broader; they generally combine multiple hypotheses into a general explanation for a wide range of phenomena, according to the University of California, Berkeley . For example, a hypothesis might state, "If animals adapt to suit their environments, then birds that live on islands with lots of seeds to eat will have differently shaped beaks than birds that live on islands with lots of insects to eat." After testing many hypotheses like these, Charles Darwin formulated an overarching theory: the theory of evolution by natural selection.

"Theories are the ways that we make sense of what we observe in the natural world," Tanner said. "Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts."

- Read more about writing a hypothesis, from the American Medical Writers Association.

- Find out why a hypothesis isn't always necessary in science, from The American Biology Teacher.

- Learn about null and alternative hypotheses, from Prof. Essa on YouTube .

Encyclopedia Britannica. Scientific Hypothesis. Jan. 13, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-hypothesis

Karl Popper, "The Logic of Scientific Discovery," Routledge, 1959.

California State University, Bakersfield, "Formatting a testable hypothesis." https://www.csub.edu/~ddodenhoff/Bio100/Bio100sp04/formattingahypothesis.htm

Karl Popper, "Conjectures and Refutations," Routledge, 1963.

Price, P., Jhangiani, R., & Chiang, I., "Research Methods of Psychology — 2nd Canadian Edition," BCcampus, 2015.

University of Miami, "The Scientific Method" http://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/161/evolution/161app1_scimethod.pdf

William M.K. Trochim, "Research Methods Knowledge Base," https://conjointly.com/kb/hypotheses-explained/

University of California, Berkeley, "Multiple Hypothesis Testing and False Discovery Rate" https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~hhuang/STAT141/Lecture-FDR.pdf

University of California, Berkeley, "Science at multiple levels" https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/howscienceworks_19

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Oldest evidence of earthquakes found in strange jumble of 3.3 billion-year-old rocks from Africa

Sleeping subduction zone could awaken and form a new 'Ring of Fire' that swallows the Atlantic Ocean

'Worrisome and even frightening': Ancient ecosystem of Lake Baikal at risk of regime change from warming

Most Popular

By Anna Gora December 27, 2023

By Anna Gora December 26, 2023

By Anna Gora December 25, 2023

By Emily Cooke December 23, 2023

By Victoria Atkinson December 22, 2023

By Anna Gora December 16, 2023

By Anna Gora December 15, 2023

By Anna Gora November 09, 2023

By Donavyn Coffey November 06, 2023

By Anna Gora October 31, 2023

By Anna Gora October 26, 2023

- 2 Mass grave of plague victims may be largest ever found in Europe, archaeologists say

- 3 India's evolutionary past tied to huge migration 50,000 years ago and to now-extinct human relatives

- 4 1,900-year-old coins from Jewish revolt against the Romans discovered in the Judaen desert

- 5 Dying SpaceX rocket creates glowing, galaxy-like spiral in the middle of the Northern Lights

- 2 'Flow state' uncovered: We finally know what happens in the brain when you're 'in the zone'

- 3 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 4 12 surprising facts about pi to chew on this Pi Day

- Scientific Methods

What is Hypothesis?

We have heard of many hypotheses which have led to great inventions in science. Assumptions that are made on the basis of some evidence are known as hypotheses. In this article, let us learn in detail about the hypothesis and the type of hypothesis with examples.

A hypothesis is an assumption that is made based on some evidence. This is the initial point of any investigation that translates the research questions into predictions. It includes components like variables, population and the relation between the variables. A research hypothesis is a hypothesis that is used to test the relationship between two or more variables.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Following are the characteristics of the hypothesis:

- The hypothesis should be clear and precise to consider it to be reliable.

- If the hypothesis is a relational hypothesis, then it should be stating the relationship between variables.

- The hypothesis must be specific and should have scope for conducting more tests.

- The way of explanation of the hypothesis must be very simple and it should also be understood that the simplicity of the hypothesis is not related to its significance.

Sources of Hypothesis

Following are the sources of hypothesis:

- The resemblance between the phenomenon.

- Observations from past studies, present-day experiences and from the competitors.

- Scientific theories.

- General patterns that influence the thinking process of people.

Types of Hypothesis

There are six forms of hypothesis and they are:

- Simple hypothesis

- Complex hypothesis

- Directional hypothesis

- Non-directional hypothesis

- Null hypothesis

- Associative and casual hypothesis

Simple Hypothesis

It shows a relationship between one dependent variable and a single independent variable. For example – If you eat more vegetables, you will lose weight faster. Here, eating more vegetables is an independent variable, while losing weight is the dependent variable.

Complex Hypothesis

It shows the relationship between two or more dependent variables and two or more independent variables. Eating more vegetables and fruits leads to weight loss, glowing skin, and reduces the risk of many diseases such as heart disease.

Directional Hypothesis

It shows how a researcher is intellectual and committed to a particular outcome. The relationship between the variables can also predict its nature. For example- children aged four years eating proper food over a five-year period are having higher IQ levels than children not having a proper meal. This shows the effect and direction of the effect.

Non-directional Hypothesis

It is used when there is no theory involved. It is a statement that a relationship exists between two variables, without predicting the exact nature (direction) of the relationship.

Null Hypothesis

It provides a statement which is contrary to the hypothesis. It’s a negative statement, and there is no relationship between independent and dependent variables. The symbol is denoted by “H O ”.

Associative and Causal Hypothesis

Associative hypothesis occurs when there is a change in one variable resulting in a change in the other variable. Whereas, the causal hypothesis proposes a cause and effect interaction between two or more variables.

Examples of Hypothesis

Following are the examples of hypotheses based on their types:

- Consumption of sugary drinks every day leads to obesity is an example of a simple hypothesis.

- All lilies have the same number of petals is an example of a null hypothesis.

- If a person gets 7 hours of sleep, then he will feel less fatigue than if he sleeps less. It is an example of a directional hypothesis.

Functions of Hypothesis

Following are the functions performed by the hypothesis:

- Hypothesis helps in making an observation and experiments possible.

- It becomes the start point for the investigation.

- Hypothesis helps in verifying the observations.

- It helps in directing the inquiries in the right direction.

How will Hypothesis help in the Scientific Method?

Researchers use hypotheses to put down their thoughts directing how the experiment would take place. Following are the steps that are involved in the scientific method:

- Formation of question

- Doing background research

- Creation of hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collection of data

- Result analysis

- Summarizing the experiment

- Communicating the results

Frequently Asked Questions – FAQs

What is hypothesis.

A hypothesis is an assumption made based on some evidence.

Give an example of simple hypothesis?

What are the types of hypothesis.

Types of hypothesis are:

- Associative and Casual hypothesis

State true or false: Hypothesis is the initial point of any investigation that translates the research questions into a prediction.

Define complex hypothesis..

A complex hypothesis shows the relationship between two or more dependent variables and two or more independent variables.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Physics related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, Ph.D., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years experience of working in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of desertion

- abandonment

- dereliction

Examples of desertion in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'desertion.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

borrowed from Middle French & Latin; Middle French, borrowed from Latin dēsertiōn-, dēsertiō, from dēserere "to part company with, abandon, leave uninhabited, leave in the lurch" + -tiōn-, -tiō, suffix of verbal action — more at desert entry 3

1591, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Dictionary Entries Near desertion

desertification

desert ironwood

Cite this Entry

“Desertion.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/desertion. Accessed 19 Mar. 2024.

Legal Definition

Legal definition of desertion.

Note: Desertion is a ground for divorce in many states.

More from Merriam-Webster on desertion

Nglish: Translation of desertion for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of desertion for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about desertion

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

8 grammar terms you used to know, but forgot, homophones, homographs, and homonyms, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 15, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Step 1. Ask a question

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is your plagiarism score.

What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

If...,Then...

Angela Lumsden/Getty Images

- Scientific Method

- Chemical Laws