How to Write a Business Plan: Step-by-Step Guide + Examples

Noah Parsons

24 min. read

Updated April 10, 2024

Writing a business plan doesn’t have to be complicated.

In this step-by-step guide, you’ll learn how to write a business plan that’s detailed enough to impress bankers and potential investors, while giving you the tools to start, run, and grow a successful business.

- The basics of business planning

If you’re reading this guide, then you already know why you need a business plan .

You understand that planning helps you:

- Raise money

- Grow strategically

- Keep your business on the right track

As you start to write your plan, it’s useful to zoom out and remember what a business plan is .

At its core, a business plan is an overview of the products and services you sell, and the customers that you sell to. It explains your business strategy: how you’re going to build and grow your business, what your marketing strategy is, and who your competitors are.

Most business plans also include financial forecasts for the future. These set sales goals, budget for expenses, and predict profits and cash flow.

A good business plan is much more than just a document that you write once and forget about. It’s also a guide that helps you outline and achieve your goals.

After completing your plan, you can use it as a management tool to track your progress toward your goals. Updating and adjusting your forecasts and budgets as you go is one of the most important steps you can take to run a healthier, smarter business.

We’ll dive into how to use your plan later in this article.

There are many different types of plans , but we’ll go over the most common type here, which includes everything you need for an investor-ready plan. However, if you’re just starting out and are looking for something simpler—I recommend starting with a one-page business plan . It’s faster and easier to create.

It’s also the perfect place to start if you’re just figuring out your idea, or need a simple strategic plan to use inside your business.

Dig deeper : How to write a one-page business plan

Brought to you by

Create a professional business plan

Using ai and step-by-step instructions.

Secure funding

Validate ideas

Build a strategy

- What to include in your business plan

Executive summary

The executive summary is an overview of your business and your plans. It comes first in your plan and is ideally just one to two pages. Most people write it last because it’s a summary of the complete business plan.

Ideally, the executive summary can act as a stand-alone document that covers the highlights of your detailed plan.

In fact, it’s common for investors to ask only for the executive summary when evaluating your business. If they like what they see in the executive summary, they’ll often follow up with a request for a complete plan, a pitch presentation , or more in-depth financial forecasts .

Your executive summary should include:

- A summary of the problem you are solving

- A description of your product or service

- An overview of your target market

- A brief description of your team

- A summary of your financials

- Your funding requirements (if you are raising money)

Dig Deeper: How to write an effective executive summary

Products and services description

This is where you describe exactly what you’re selling, and how it solves a problem for your target market. The best way to organize this part of your plan is to start by describing the problem that exists for your customers. After that, you can describe how you plan to solve that problem with your product or service.

This is usually called a problem and solution statement .

To truly showcase the value of your products and services, you need to craft a compelling narrative around your offerings. How will your product or service transform your customers’ lives or jobs? A strong narrative will draw in your readers.

This is also the part of the business plan to discuss any competitive advantages you may have, like specific intellectual property or patents that protect your product. If you have any initial sales, contracts, or other evidence that your product or service is likely to sell, include that information as well. It will show that your idea has traction , which can help convince readers that your plan has a high chance of success.

Market analysis

Your target market is a description of the type of people that you plan to sell to. You might even have multiple target markets, depending on your business.

A market analysis is the part of your plan where you bring together all of the information you know about your target market. Basically, it’s a thorough description of who your customers are and why they need what you’re selling. You’ll also include information about the growth of your market and your industry .

Try to be as specific as possible when you describe your market.

Include information such as age, income level, and location—these are what’s called “demographics.” If you can, also describe your market’s interests and habits as they relate to your business—these are “psychographics.”

Related: Target market examples

Essentially, you want to include any knowledge you have about your customers that is relevant to how your product or service is right for them. With a solid target market, it will be easier to create a sales and marketing plan that will reach your customers. That’s because you know who they are, what they like to do, and the best ways to reach them.

Next, provide any additional information you have about your market.

What is the size of your market ? Is the market growing or shrinking? Ideally, you’ll want to demonstrate that your market is growing over time, and also explain how your business is positioned to take advantage of any expected changes in your industry.

Dig Deeper: Learn how to write a market analysis

Competitive analysis

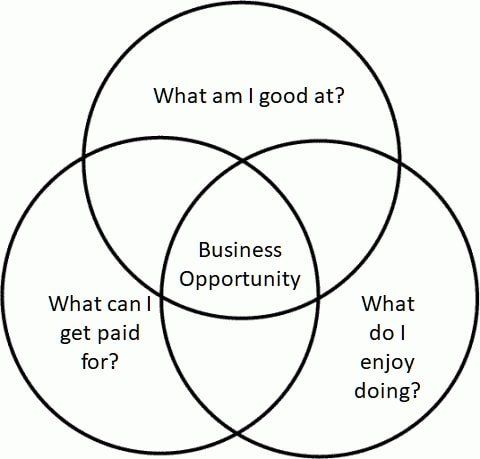

Part of defining your business opportunity is determining what your competitive advantage is. To do this effectively, you need to know as much about your competitors as your target customers.

Every business has some form of competition. If you don’t think you have competitors, then explore what alternatives there are in the market for your product or service.

For example: In the early years of cars, their main competition was horses. For social media, the early competition was reading books, watching TV, and talking on the phone.

A good competitive analysis fully lays out the competitive landscape and then explains how your business is different. Maybe your products are better made, or cheaper, or your customer service is superior. Maybe your competitive advantage is your location – a wide variety of factors can ultimately give you an advantage.

Dig Deeper: How to write a competitive analysis for your business plan

Marketing and sales plan

The marketing and sales plan covers how you will position your product or service in the market, the marketing channels and messaging you will use, and your sales tactics.

The best place to start with a marketing plan is with a positioning statement .

This explains how your business fits into the overall market, and how you will explain the advantages of your product or service to customers. You’ll use the information from your competitive analysis to help you with your positioning.

For example: You might position your company as the premium, most expensive but the highest quality option in the market. Or your positioning might focus on being locally owned and that shoppers support the local economy by buying your products.

Once you understand your positioning, you’ll bring this together with the information about your target market to create your marketing strategy .

This is how you plan to communicate your message to potential customers. Depending on who your customers are and how they purchase products like yours, you might use many different strategies, from social media advertising to creating a podcast. Your marketing plan is all about how your customers discover who you are and why they should consider your products and services.

While your marketing plan is about reaching your customers—your sales plan will describe the actual sales process once a customer has decided that they’re interested in what you have to offer.

If your business requires salespeople and a long sales process, describe that in this section. If your customers can “self-serve” and just make purchases quickly on your website, describe that process.

A good sales plan picks up where your marketing plan leaves off. The marketing plan brings customers in the door and the sales plan is how you close the deal.

Together, these specific plans paint a picture of how you will connect with your target audience, and how you will turn them into paying customers.

Dig deeper: What to include in your sales and marketing plan

Business operations

The operations section describes the necessary requirements for your business to run smoothly. It’s where you talk about how your business works and what day-to-day operations look like.

Depending on how your business is structured, your operations plan may include elements of the business like:

- Supply chain management

- Manufacturing processes

- Equipment and technology

- Distribution

Some businesses distribute their products and reach their customers through large retailers like Amazon.com, Walmart, Target, and grocery store chains.

These businesses should review how this part of their business works. The plan should discuss the logistics and costs of getting products onto store shelves and any potential hurdles the business may have to overcome.

If your business is much simpler than this, that’s OK. This section of your business plan can be either extremely short or more detailed, depending on the type of business you are building.

For businesses selling services, such as physical therapy or online software, you can use this section to describe the technology you’ll leverage, what goes into your service, and who you will partner with to deliver your services.

Dig Deeper: Learn how to write the operations chapter of your plan

Key milestones and metrics

Although it’s not required to complete your business plan, mapping out key business milestones and the metrics can be incredibly useful for measuring your success.

Good milestones clearly lay out the parameters of the task and set expectations for their execution. You’ll want to include:

- A description of each task

- The proposed due date

- Who is responsible for each task

If you have a budget, you can include projected costs to hit each milestone. You don’t need extensive project planning in this section—just list key milestones you want to hit and when you plan to hit them. This is your overall business roadmap.

Possible milestones might be:

- Website launch date

- Store or office opening date

- First significant sales

- Break even date

- Business licenses and approvals

You should also discuss the key numbers you will track to determine your success. Some common metrics worth tracking include:

- Conversion rates

- Customer acquisition costs

- Profit per customer

- Repeat purchases

It’s perfectly fine to start with just a few metrics and grow the number you are tracking over time. You also may find that some metrics simply aren’t relevant to your business and can narrow down what you’re tracking.

Dig Deeper: How to use milestones in your business plan

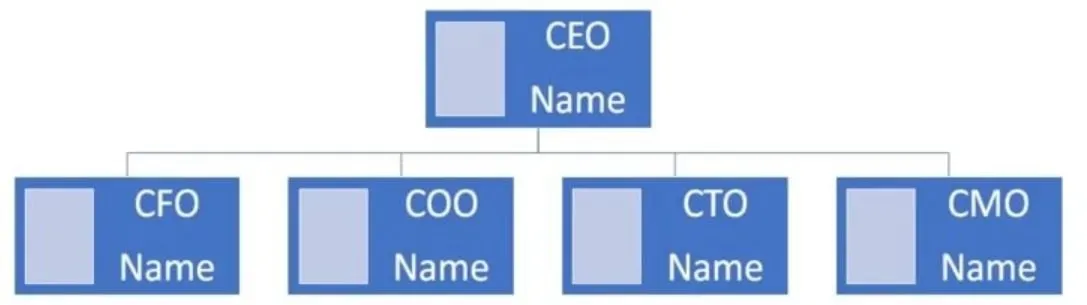

Organization and management team

Investors don’t just look for great ideas—they want to find great teams. Use this chapter to describe your current team and who you need to hire . You should also provide a quick overview of your location and history if you’re already up and running.

Briefly highlight the relevant experiences of each key team member in the company. It’s important to make the case for why yours is the right team to turn an idea into a reality.

Do they have the right industry experience and background? Have members of the team had entrepreneurial successes before?

If you still need to hire key team members, that’s OK. Just note those gaps in this section.

Your company overview should also include a summary of your company’s current business structure . The most common business structures include:

- Sole proprietor

- Partnership

Be sure to provide an overview of how the business is owned as well. Does each business partner own an equal portion of the business? How is ownership divided?

Potential lenders and investors will want to know the structure of the business before they will consider a loan or investment.

Dig Deeper: How to write about your company structure and team

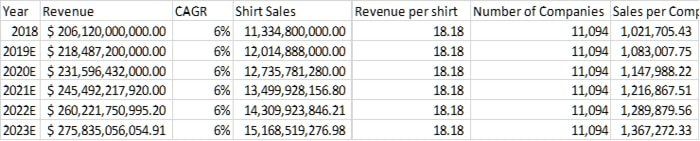

Financial plan

Last, but certainly not least, is your financial plan chapter.

Entrepreneurs often find this section the most daunting. But, business financials for most startups are less complicated than you think, and a business degree is certainly not required to build a solid financial forecast.

A typical financial forecast in a business plan includes the following:

- Sales forecast : An estimate of the sales expected over a given period. You’ll break down your forecast into the key revenue streams that you expect to have.

- Expense budget : Your planned spending such as personnel costs , marketing expenses, and taxes.

- Profit & Loss : Brings together your sales and expenses and helps you calculate planned profits.

- Cash Flow : Shows how cash moves into and out of your business. It can predict how much cash you’ll have on hand at any given point in the future.

- Balance Sheet : A list of the assets, liabilities, and equity in your company. In short, it provides an overview of the financial health of your business.

A strong business plan will include a description of assumptions about the future, and potential risks that could impact the financial plan. Including those will be especially important if you’re writing a business plan to pursue a loan or other investment.

Dig Deeper: How to create financial forecasts and budgets

This is the place for additional data, charts, or other information that supports your plan.

Including an appendix can significantly enhance the credibility of your plan by showing readers that you’ve thoroughly considered the details of your business idea, and are backing your ideas up with solid data.

Just remember that the information in the appendix is meant to be supplementary. Your business plan should stand on its own, even if the reader skips this section.

Dig Deeper : What to include in your business plan appendix

Optional: Business plan cover page

Adding a business plan cover page can make your plan, and by extension your business, seem more professional in the eyes of potential investors, lenders, and partners. It serves as the introduction to your document and provides necessary contact information for stakeholders to reference.

Your cover page should be simple and include:

- Company logo

- Business name

- Value proposition (optional)

- Business plan title

- Completion and/or update date

- Address and contact information

- Confidentiality statement

Just remember, the cover page is optional. If you decide to include it, keep it very simple and only spend a short amount of time putting it together.

Dig Deeper: How to create a business plan cover page

How to use AI to help write your business plan

Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT can speed up the business plan writing process and help you think through concepts like market segmentation and competition. These tools are especially useful for taking ideas that you provide and converting them into polished text for your business plan.

The best way to use AI for your business plan is to leverage it as a collaborator , not a replacement for human creative thinking and ingenuity.

AI can come up with lots of ideas and act as a brainstorming partner. It’s up to you to filter through those ideas and figure out which ones are realistic enough to resonate with your customers.

There are pros and cons of using AI to help with your business plan . So, spend some time understanding how it can be most helpful before just outsourcing the job to AI.

Learn more: 10 AI prompts you need to write a business plan

- Writing tips and strategies

To help streamline the business plan writing process, here are a few tips and key questions to answer to make sure you get the most out of your plan and avoid common mistakes .

Determine why you are writing a business plan

Knowing why you are writing a business plan will determine your approach to your planning project.

For example: If you are writing a business plan for yourself, or just to use inside your own business , you can probably skip the section about your team and organizational structure.

If you’re raising money, you’ll want to spend more time explaining why you’re looking to raise the funds and exactly how you will use them.

Regardless of how you intend to use your business plan , think about why you are writing and what you’re trying to get out of the process before you begin.

Keep things concise

Probably the most important tip is to keep your business plan short and simple. There are no prizes for long business plans . The longer your plan is, the less likely people are to read it.

So focus on trimming things down to the essentials your readers need to know. Skip the extended, wordy descriptions and instead focus on creating a plan that is easy to read —using bullets and short sentences whenever possible.

Have someone review your business plan

Writing a business plan in a vacuum is never a good idea. Sometimes it’s helpful to zoom out and check if your plan makes sense to someone else. You also want to make sure that it’s easy to read and understand.

Don’t wait until your plan is “done” to get a second look. Start sharing your plan early, and find out from readers what questions your plan leaves unanswered. This early review cycle will help you spot shortcomings in your plan and address them quickly, rather than finding out about them right before you present your plan to a lender or investor.

If you need a more detailed review, you may want to explore hiring a professional plan writer to thoroughly examine it.

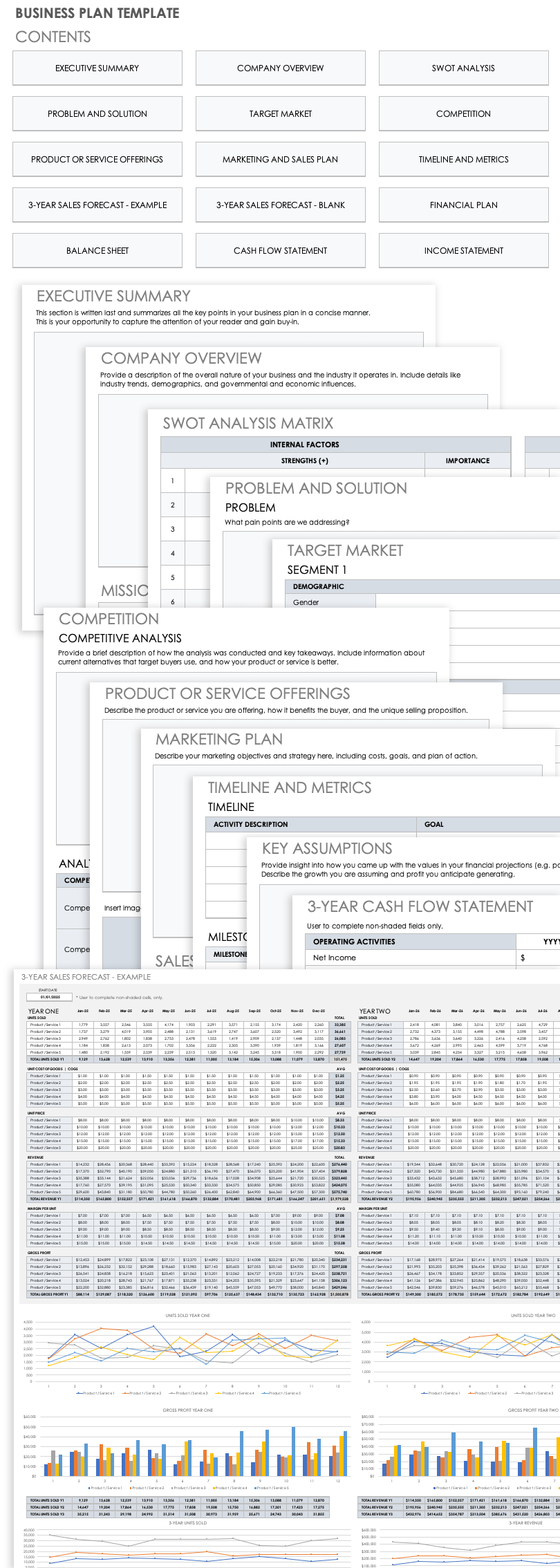

Use a free business plan template and business plan examples to get started

Knowing what information to include in a business plan is sometimes not quite enough. If you’re struggling to get started or need additional guidance, it may be worth using a business plan template.

There are plenty of great options available (we’ve rounded up our 8 favorites to streamline your search).

But, if you’re looking for a free downloadable business plan template , you can get one right now; download the template used by more than 1 million businesses.

Or, if you just want to see what a completed business plan looks like, check out our library of over 550 free business plan examples .

We even have a growing list of industry business planning guides with tips for what to focus on depending on your business type.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

It’s easy to make mistakes when you’re writing your business plan. Some entrepreneurs get sucked into the writing and research process, and don’t focus enough on actually getting their business started.

Here are a few common mistakes and how to avoid them:

Not talking to your customers : This is one of the most common mistakes. It’s easy to assume that your product or service is something that people want. Before you invest too much in your business and too much in the planning process, make sure you talk to your prospective customers and have a good understanding of their needs.

- Overly optimistic sales and profit forecasts: By nature, entrepreneurs are optimistic about the future. But it’s good to temper that optimism a little when you’re planning, and make sure your forecasts are grounded in reality.

- Spending too much time planning: Yes, planning is crucial. But you also need to get out and talk to customers, build prototypes of your product and figure out if there’s a market for your idea. Make sure to balance planning with building.

- Not revising the plan: Planning is useful, but nothing ever goes exactly as planned. As you learn more about what’s working and what’s not—revise your plan, your budgets, and your revenue forecast. Doing so will provide a more realistic picture of where your business is going, and what your financial needs will be moving forward.

- Not using the plan to manage your business: A good business plan is a management tool. Don’t just write it and put it on the shelf to collect dust – use it to track your progress and help you reach your goals.

- Presenting your business plan

The planning process forces you to think through every aspect of your business and answer questions that you may not have thought of. That’s the real benefit of writing a business plan – the knowledge you gain about your business that you may not have been able to discover otherwise.

With all of this knowledge, you’re well prepared to convert your business plan into a pitch presentation to present your ideas.

A pitch presentation is a summary of your plan, just hitting the highlights and key points. It’s the best way to present your business plan to investors and team members.

Dig Deeper: Learn what key slides should be included in your pitch deck

Use your business plan to manage your business

One of the biggest benefits of planning is that it gives you a tool to manage your business better. With a revenue forecast, expense budget, and projected cash flow, you know your targets and where you are headed.

And yet, nothing ever goes exactly as planned – it’s the nature of business.

That’s where using your plan as a management tool comes in. The key to leveraging it for your business is to review it periodically and compare your forecasts and projections to your actual results.

Start by setting up a regular time to review the plan – a monthly review is a good starting point. During this review, answer questions like:

- Did you meet your sales goals?

- Is spending following your budget?

- Has anything gone differently than what you expected?

Now that you see whether you’re meeting your goals or are off track, you can make adjustments and set new targets.

Maybe you’re exceeding your sales goals and should set new, more aggressive goals. In that case, maybe you should also explore more spending or hiring more employees.

Or maybe expenses are rising faster than you projected. If that’s the case, you would need to look at where you can cut costs.

A plan, and a method for comparing your plan to your actual results , is the tool you need to steer your business toward success.

Learn More: How to run a regular plan review

Free business plan templates and examples

Kickstart your business plan writing with one of our free business plan templates or recommended tools.

Free business plan template

Download a free SBA-approved business plan template built for small businesses and startups.

Download Template

One-page plan template

Download a free one-page plan template to write a useful business plan in as little as 30-minutes.

Sample business plan library

Explore over 500 real-world business plan examples from a wide variety of industries.

View Sample Plans

How to write a business plan FAQ

What is a business plan?

A document that describes your business , the products and services you sell, and the customers that you sell to. It explains your business strategy, how you’re going to build and grow your business, what your marketing strategy is, and who your competitors are.

What are the benefits of a business plan?

A business plan helps you understand where you want to go with your business and what it will take to get there. It reduces your overall risk, helps you uncover your business’s potential, attracts investors, and identifies areas for growth.

Having a business plan ultimately makes you more confident as a business owner and more likely to succeed for a longer period of time.

What are the 7 steps of a business plan?

The seven steps to writing a business plan include:

- Write a brief executive summary

- Describe your products and services.

- Conduct market research and compile data into a cohesive market analysis.

- Describe your marketing and sales strategy.

- Outline your organizational structure and management team.

- Develop financial projections for sales, revenue, and cash flow.

- Add any additional documents to your appendix.

What are the 5 most common business plan mistakes?

There are plenty of mistakes that can be made when writing a business plan. However, these are the 5 most common that you should do your best to avoid:

- 1. Not taking the planning process seriously.

- Having unrealistic financial projections or incomplete financial information.

- Inconsistent information or simple mistakes.

- Failing to establish a sound business model.

- Not having a defined purpose for your business plan.

What questions should be answered in a business plan?

Writing a business plan is all about asking yourself questions about your business and being able to answer them through the planning process. You’ll likely be asking dozens and dozens of questions for each section of your plan.

However, these are the key questions you should ask and answer with your business plan:

- How will your business make money?

- Is there a need for your product or service?

- Who are your customers?

- How are you different from the competition?

- How will you reach your customers?

- How will you measure success?

How long should a business plan be?

The length of your business plan fully depends on what you intend to do with it. From the SBA and traditional lender point of view, a business plan needs to be whatever length necessary to fully explain your business. This means that you prove the viability of your business, show that you understand the market, and have a detailed strategy in place.

If you intend to use your business plan for internal management purposes, you don’t necessarily need a full 25-50 page business plan. Instead, you can start with a one-page plan to get all of the necessary information in place.

What are the different types of business plans?

While all business plans cover similar categories, the style and function fully depend on how you intend to use your plan. Here are a few common business plan types worth considering.

Traditional business plan: The tried-and-true traditional business plan is a formal document meant to be used when applying for funding or pitching to investors. This type of business plan follows the outline above and can be anywhere from 10-50 pages depending on the amount of detail included, the complexity of your business, and what you include in your appendix.

Business model canvas: The business model canvas is a one-page template designed to demystify the business planning process. It removes the need for a traditional, copy-heavy business plan, in favor of a single-page outline that can help you and outside parties better explore your business idea.

One-page business plan: This format is a simplified version of the traditional plan that focuses on the core aspects of your business. You’ll typically stick with bullet points and single sentences. It’s most useful for those exploring ideas, needing to validate their business model, or who need an internal plan to help them run and manage their business.

Lean Plan: The Lean Plan is less of a specific document type and more of a methodology. It takes the simplicity and styling of the one-page business plan and turns it into a process for you to continuously plan, test, review, refine, and take action based on performance. It’s faster, keeps your plan concise, and ensures that your plan is always up-to-date.

What’s the difference between a business plan and a strategic plan?

A business plan covers the “who” and “what” of your business. It explains what your business is doing right now and how it functions. The strategic plan explores long-term goals and explains “how” the business will get there. It encourages you to look more intently toward the future and how you will achieve your vision.

However, when approached correctly, your business plan can actually function as a strategic plan as well. If kept lean, you can define your business, outline strategic steps, and track ongoing operations all with a single plan.

See why 1.2 million entrepreneurs have written their business plans with LivePlan

Noah is the COO at Palo Alto Software, makers of the online business plan app LivePlan. He started his career at Yahoo! and then helped start the user review site Epinions.com. From there he started a software distribution business in the UK before coming to Palo Alto Software to run the marketing and product teams.

Table of Contents

- Use AI to help write your plan

- Common planning mistakes

- Manage with your business plan

- Templates and examples

Related Articles

7 Min. Read

How to Write an Online Boutique Clothing Store Business Plan + Example Templates

2 Min. Read

How to Use These Common Business Ratios

12 Min. Read

How to Write a Food Truck Business Plan (2024 + Template)

6 Min. Read

How to Get and Show Initial Traction for Your Business

The Bplans Newsletter

The Bplans Weekly

Subscribe now for weekly advice and free downloadable resources to help start and grow your business.

We care about your privacy. See our privacy policy .

The quickest way to turn a business idea into a business plan

Fill-in-the-blanks and automatic financials make it easy.

No thanks, I prefer writing 40-page documents.

Discover the world’s #1 plan building software

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Simple Business Plan

By Joe Weller | October 11, 2021

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

A business plan is the cornerstone of any successful company, regardless of size or industry. This step-by-step guide provides information on writing a business plan for organizations at any stage, complete with free templates and expert advice.

Included on this page, you’ll find a step-by-step guide to writing a business plan and a chart to identify which type of business plan you should write . Plus, find information on how a business plan can help grow a business and expert tips on writing one .

What Is a Business Plan?

A business plan is a document that communicates a company’s goals and ambitions, along with the timeline, finances, and methods needed to achieve them. Additionally, it may include a mission statement and details about the specific products or services offered.

A business plan can highlight varying time periods, depending on the stage of your company and its goals. That said, a typical business plan will include the following benchmarks:

- Product goals and deadlines for each month

- Monthly financials for the first two years

- Profit and loss statements for the first three to five years

- Balance sheet projections for the first three to five years

Startups, entrepreneurs, and small businesses all create business plans to use as a guide as their new company progresses. Larger organizations may also create (and update) a business plan to keep high-level goals, financials, and timelines in check.

While you certainly need to have a formalized outline of your business’s goals and finances, creating a business plan can also help you determine a company’s viability, its profitability (including when it will first turn a profit), and how much money you will need from investors. In turn, a business plan has functional value as well: Not only does outlining goals help keep you accountable on a timeline, it can also attract investors in and of itself and, therefore, act as an effective strategy for growth.

For more information, visit our comprehensive guide to writing a strategic plan or download free strategic plan templates . This page focuses on for-profit business plans, but you can read our article with nonprofit business plan templates .

Business Plan Steps

The specific information in your business plan will vary, depending on the needs and goals of your venture, but a typical plan includes the following ordered elements:

- Executive summary

- Description of business

- Market analysis

- Competitive analysis

- Description of organizational management

- Description of product or services

- Marketing plan

- Sales strategy

- Funding details (or request for funding)

- Financial projections

If your plan is particularly long or complicated, consider adding a table of contents or an appendix for reference. For an in-depth description of each step listed above, read “ How to Write a Business Plan Step by Step ” below.

Broadly speaking, your audience includes anyone with a vested interest in your organization. They can include potential and existing investors, as well as customers, internal team members, suppliers, and vendors.

Do I Need a Simple or Detailed Plan?

Your business’s stage and intended audience dictates the level of detail your plan needs. Corporations require a thorough business plan — up to 100 pages. Small businesses or startups should have a concise plan focusing on financials and strategy.

How to Choose the Right Plan for Your Business

In order to identify which type of business plan you need to create, ask: “What do we want the plan to do?” Identify function first, and form will follow.

Use the chart below as a guide for what type of business plan to create:

Is the Order of Your Business Plan Important?

There is no set order for a business plan, with the exception of the executive summary, which should always come first. Beyond that, simply ensure that you organize the plan in a way that makes sense and flows naturally.

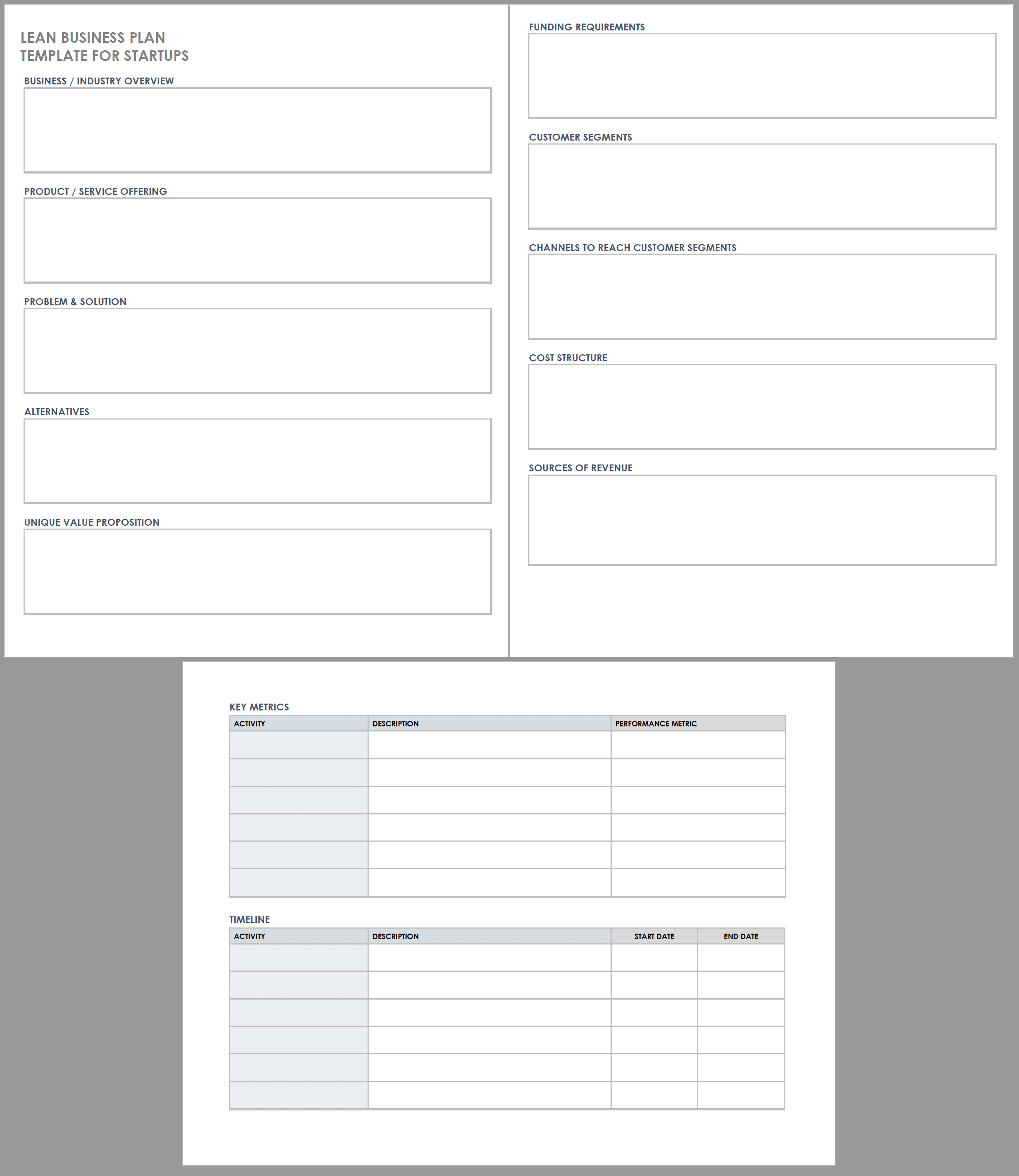

The Difference Between Traditional and Lean Business Plans

A traditional business plan follows the standard structure — because these plans encourage detail, they tend to require more work upfront and can run dozens of pages. A Lean business plan is less common and focuses on summarizing critical points for each section. These plans take much less work and typically run one page in length.

In general, you should use a traditional model for a legacy company, a large company, or any business that does not adhere to Lean (or another Agile method ). Use Lean if you expect the company to pivot quickly or if you already employ a Lean strategy with other business operations. Additionally, a Lean business plan can suffice if the document is for internal use only. Stick to a traditional version for investors, as they may be more sensitive to sudden changes or a high degree of built-in flexibility in the plan.

How to Write a Business Plan Step by Step

Writing a strong business plan requires research and attention to detail for each section. Below, you’ll find a 10-step guide to researching and defining each element in the plan.

Step 1: Executive Summary

The executive summary will always be the first section of your business plan. The goal is to answer the following questions:

- What is the vision and mission of the company?

- What are the company’s short- and long-term goals?

See our roundup of executive summary examples and templates for samples. Read our executive summary guide to learn more about writing one.

Step 2: Description of Business

The goal of this section is to define the realm, scope, and intent of your venture. To do so, answer the following questions as clearly and concisely as possible:

- What business are we in?

- What does our business do?

Step 3: Market Analysis

In this section, provide evidence that you have surveyed and understand the current marketplace, and that your product or service satisfies a niche in the market. To do so, answer these questions:

- Who is our customer?

- What does that customer value?

Step 4: Competitive Analysis

In many cases, a business plan proposes not a brand-new (or even market-disrupting) venture, but a more competitive version — whether via features, pricing, integrations, etc. — than what is currently available. In this section, answer the following questions to show that your product or service stands to outpace competitors:

- Who is the competition?

- What do they do best?

- What is our unique value proposition?

Step 5: Description of Organizational Management

In this section, write an overview of the team members and other key personnel who are integral to success. List roles and responsibilities, and if possible, note the hierarchy or team structure.

Step 6: Description of Products or Services

In this section, clearly define your product or service, as well as all the effort and resources that go into producing it. The strength of your product largely defines the success of your business, so it’s imperative that you take time to test and refine the product before launching into marketing, sales, or funding details.

Questions to answer in this section are as follows:

- What is the product or service?

- How do we produce it, and what resources are necessary for production?

Step 7: Marketing Plan

In this section, define the marketing strategy for your product or service. This doesn’t need to be as fleshed out as a full marketing plan , but it should answer basic questions, such as the following:

- Who is the target market (if different from existing customer base)?

- What channels will you use to reach your target market?

- What resources does your marketing strategy require, and do you have access to them?

- If possible, do you have a rough estimate of timeline and budget?

- How will you measure success?

Step 8: Sales Plan

Write an overview of the sales strategy, including the priorities of each cycle, steps to achieve these goals, and metrics for success. For the purposes of a business plan, this section does not need to be a comprehensive, in-depth sales plan , but can simply outline the high-level objectives and strategies of your sales efforts.

Start by answering the following questions:

- What is the sales strategy?

- What are the tools and tactics you will use to achieve your goals?

- What are the potential obstacles, and how will you overcome them?

- What is the timeline for sales and turning a profit?

- What are the metrics of success?

Step 9: Funding Details (or Request for Funding)

This section is one of the most critical parts of your business plan, particularly if you are sharing it with investors. You do not need to provide a full financial plan, but you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How much capital do you currently have? How much capital do you need?

- How will you grow the team (onboarding, team structure, training and development)?

- What are your physical needs and constraints (space, equipment, etc.)?

Step 10: Financial Projections

Apart from the fundraising analysis, investors like to see thought-out financial projections for the future. As discussed earlier, depending on the scope and stage of your business, this could be anywhere from one to five years.

While these projections won’t be exact — and will need to be somewhat flexible — you should be able to gauge the following:

- How and when will the company first generate a profit?

- How will the company maintain profit thereafter?

Business Plan Template

Download Business Plan Template

Microsoft Excel | Smartsheet

This basic business plan template has space for all the traditional elements: an executive summary, product or service details, target audience, marketing and sales strategies, etc. In the finances sections, input your baseline numbers, and the template will automatically calculate projections for sales forecasting, financial statements, and more.

For templates tailored to more specific needs, visit this business plan template roundup or download a fill-in-the-blank business plan template to make things easy.

If you are looking for a particular template by file type, visit our pages dedicated exclusively to Microsoft Excel , Microsoft Word , and Adobe PDF business plan templates.

How to Write a Simple Business Plan

A simple business plan is a streamlined, lightweight version of the large, traditional model. As opposed to a one-page business plan , which communicates high-level information for quick overviews (such as a stakeholder presentation), a simple business plan can exceed one page.

Below are the steps for creating a generic simple business plan, which are reflected in the template below .

- Write the Executive Summary This section is the same as in the traditional business plan — simply offer an overview of what’s in the business plan, the prospect or core offering, and the short- and long-term goals of the company.

- Add a Company Overview Document the larger company mission and vision.

- Provide the Problem and Solution In straightforward terms, define the problem you are attempting to solve with your product or service and how your company will attempt to do it. Think of this section as the gap in the market you are attempting to close.

- Identify the Target Market Who is your company (and its products or services) attempting to reach? If possible, briefly define your buyer personas .

- Write About the Competition In this section, demonstrate your knowledge of the market by listing the current competitors and outlining your competitive advantage.

- Describe Your Product or Service Offerings Get down to brass tacks and define your product or service. What exactly are you selling?

- Outline Your Marketing Tactics Without getting into too much detail, describe your planned marketing initiatives.

- Add a Timeline and the Metrics You Will Use to Measure Success Offer a rough timeline, including milestones and key performance indicators (KPIs) that you will use to measure your progress.

- Include Your Financial Forecasts Write an overview of your financial plan that demonstrates you have done your research and adequate modeling. You can also list key assumptions that go into this forecasting.

- Identify Your Financing Needs This section is where you will make your funding request. Based on everything in the business plan, list your proposed sources of funding, as well as how you will use it.

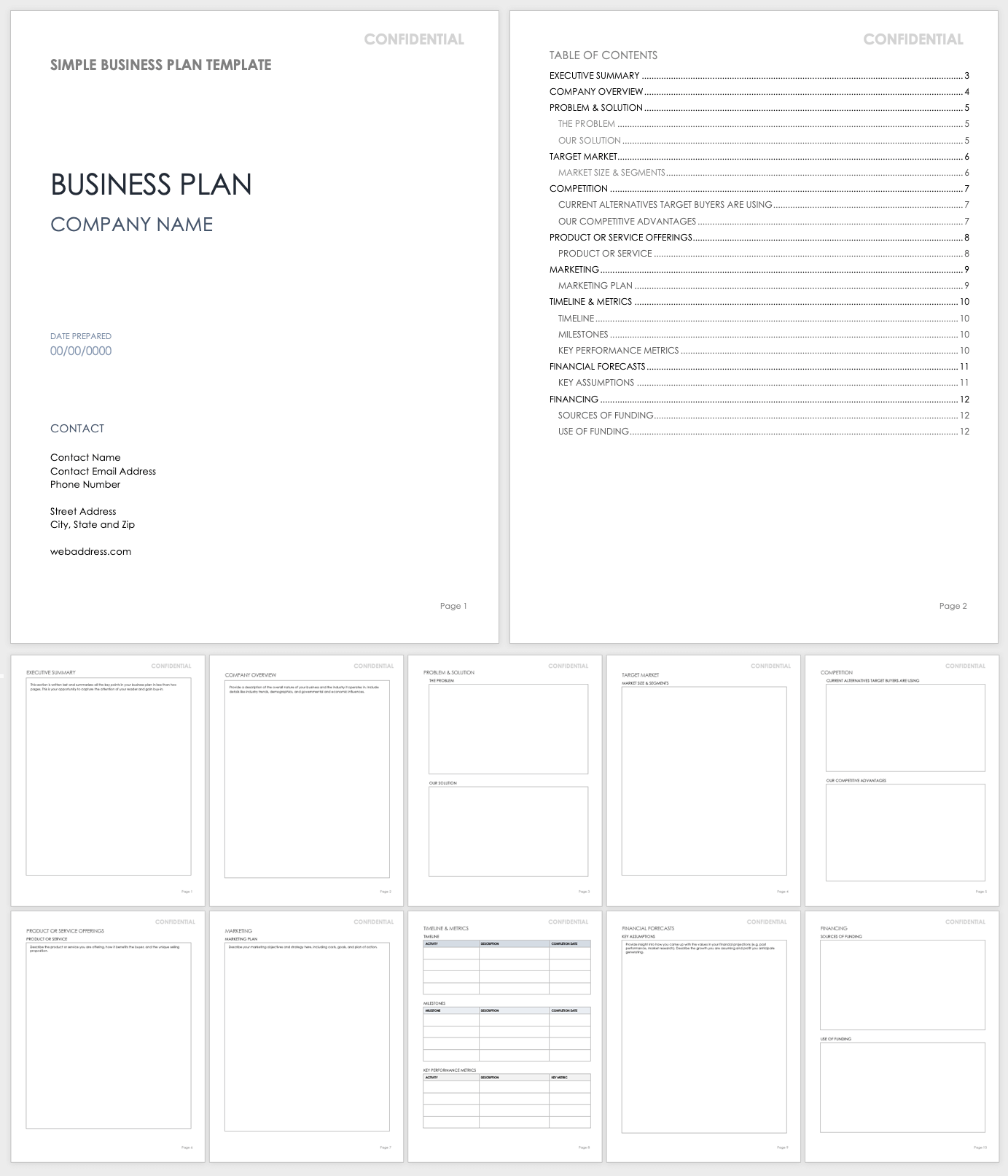

Simple Business Plan Template

Download Simple Business Plan Template

Microsoft Excel | Microsoft Word | Adobe PDF | Smartsheet

Use this simple business plan template to outline each aspect of your organization, including information about financing and opportunities to seek out further funding. This template is completely customizable to fit the needs of any business, whether it’s a startup or large company.

Read our article offering free simple business plan templates or free 30-60-90-day business plan templates to find more tailored options. You can also explore our collection of one page business templates .

How to Write a Business Plan for a Lean Startup

A Lean startup business plan is a more Agile approach to a traditional version. The plan focuses more on activities, processes, and relationships (and maintains flexibility in all aspects), rather than on concrete deliverables and timelines.

While there is some overlap between a traditional and a Lean business plan, you can write a Lean plan by following the steps below:

- Add Your Value Proposition Take a streamlined approach to describing your product or service. What is the unique value your startup aims to deliver to customers? Make sure the team is aligned on the core offering and that you can state it in clear, simple language.

- List Your Key Partners List any other businesses you will work with to realize your vision, including external vendors, suppliers, and partners. This section demonstrates that you have thoughtfully considered the resources you can provide internally, identified areas for external assistance, and conducted research to find alternatives.

- Note the Key Activities Describe the key activities of your business, including sourcing, production, marketing, distribution channels, and customer relationships.

- Include Your Key Resources List the critical resources — including personnel, equipment, space, and intellectual property — that will enable you to deliver your unique value.

- Identify Your Customer Relationships and Channels In this section, document how you will reach and build relationships with customers. Provide a high-level map of the customer experience from start to finish, including the spaces in which you will interact with the customer (online, retail, etc.).

- Detail Your Marketing Channels Describe the marketing methods and communication platforms you will use to identify and nurture your relationships with customers. These could be email, advertising, social media, etc.

- Explain the Cost Structure This section is especially necessary in the early stages of a business. Will you prioritize maximizing value or keeping costs low? List the foundational startup costs and how you will move toward profit over time.

- Share Your Revenue Streams Over time, how will the company make money? Include both the direct product or service purchase, as well as secondary sources of revenue, such as subscriptions, selling advertising space, fundraising, etc.

Lean Business Plan Template for Startups

Download Lean Business Plan Template for Startups

Microsoft Word | Adobe PDF

Startup leaders can use this Lean business plan template to relay the most critical information from a traditional plan. You’ll find all the sections listed above, including spaces for industry and product overviews, cost structure and sources of revenue, and key metrics, and a timeline. The template is completely customizable, so you can edit it to suit the objectives of your Lean startups.

See our wide variety of startup business plan templates for more options.

How to Write a Business Plan for a Loan

A business plan for a loan, often called a loan proposal , includes many of the same aspects of a traditional business plan, as well as additional financial documents, such as a credit history, a loan request, and a loan repayment plan.

In addition, you may be asked to include personal and business financial statements, a form of collateral, and equity investment information.

Download free financial templates to support your business plan.

Tips for Writing a Business Plan

Outside of including all the key details in your business plan, you have several options to elevate the document for the highest chance of winning funding and other resources. Follow these tips from experts:.

- Keep It Simple: Avner Brodsky , the Co-Founder and CEO of Lezgo Limited, an online marketing company, uses the acronym KISS (keep it short and simple) as a variation on this idea. “The business plan is not a college thesis,” he says. “Just focus on providing the essential information.”

- Do Adequate Research: Michael Dean, the Co-Founder of Pool Research , encourages business leaders to “invest time in research, both internal and external (market, finance, legal etc.). Avoid being overly ambitious or presumptive. Instead, keep everything objective, balanced, and accurate.” Your plan needs to stand on its own, and you must have the data to back up any claims or forecasting you make. As Brodsky explains, “Your business needs to be grounded on the realities of the market in your chosen location. Get the most recent data from authoritative sources so that the figures are vetted by experts and are reliable.”

- Set Clear Goals: Make sure your plan includes clear, time-based goals. “Short-term goals are key to momentum growth and are especially important to identify for new businesses,” advises Dean.

- Know (and Address) Your Weaknesses: “This awareness sets you up to overcome your weak points much quicker than waiting for them to arise,” shares Dean. Brodsky recommends performing a full SWOT analysis to identify your weaknesses, too. “Your business will fare better with self-knowledge, which will help you better define the mission of your business, as well as the strategies you will choose to achieve your objectives,” he adds.

- Seek Peer or Mentor Review: “Ask for feedback on your drafts and for areas to improve,” advises Brodsky. “When your mind is filled with dreams for your business, sometimes it is an outsider who can tell you what you’re missing and will save your business from being a product of whimsy.”

Outside of these more practical tips, the language you use is also important and may make or break your business plan.

Shaun Heng, VP of Operations at Coin Market Cap , gives the following advice on the writing, “Your business plan is your sales pitch to an investor. And as with any sales pitch, you need to strike the right tone and hit a few emotional chords. This is a little tricky in a business plan, because you also need to be formal and matter-of-fact. But you can still impress by weaving in descriptive language and saying things in a more elegant way.

“A great way to do this is by expanding your vocabulary, avoiding word repetition, and using business language. Instead of saying that something ‘will bring in as many customers as possible,’ try saying ‘will garner the largest possible market segment.’ Elevate your writing with precise descriptive words and you'll impress even the busiest investor.”

Additionally, Dean recommends that you “stay consistent and concise by keeping your tone and style steady throughout, and your language clear and precise. Include only what is 100 percent necessary.”

Resources for Writing a Business Plan

While a template provides a great outline of what to include in a business plan, a live document or more robust program can provide additional functionality, visibility, and real-time updates. The U.S. Small Business Association also curates resources for writing a business plan.

Additionally, you can use business plan software to house data, attach documentation, and share information with stakeholders. Popular options include LivePlan, Enloop, BizPlanner, PlanGuru, and iPlanner.

How a Business Plan Helps to Grow Your Business

A business plan — both the exercise of creating one and the document — can grow your business by helping you to refine your product, target audience, sales plan, identify opportunities, secure funding, and build new partnerships.

Outside of these immediate returns, writing a business plan is a useful exercise in that it forces you to research the market, which prompts you to forge your unique value proposition and identify ways to beat the competition. Doing so will also help you build (and keep you accountable to) attainable financial and product milestones. And down the line, it will serve as a welcome guide as hurdles inevitably arise.

Streamline Your Business Planning Activities with Real-Time Work Management in Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

- Sources of Business Finance

- Small Business Loans

- Small Business Grants

- Crowdfunding Sites

- How to Get a Business Loan

- Small Business Insurance Providers

- Best Factoring Companies

- Types of Bank Accounts

- Best Banks for Small Business

- Best Business Bank Accounts

- Open a Business Bank Account

- Bank Accounts for Small Businesses

- Free Business Checking Accounts

- Best Business Credit Cards

- Get a Business Credit Card

- Business Credit Cards for Bad Credit

- Build Business Credit Fast

- Business Loan Eligibility Criteria

- Small-Business Bookkeeping Basics

- How to Set Financial Goals

- Business Loan Calculators

- How to Calculate ROI

- Calculate Net Income

- Calculate Working Capital

- Calculate Operating Income

- Calculate Net Present Value (NPV)

- Calculate Payroll Tax

How to Write a Business Plan in 9 Steps (+ Template and Examples)

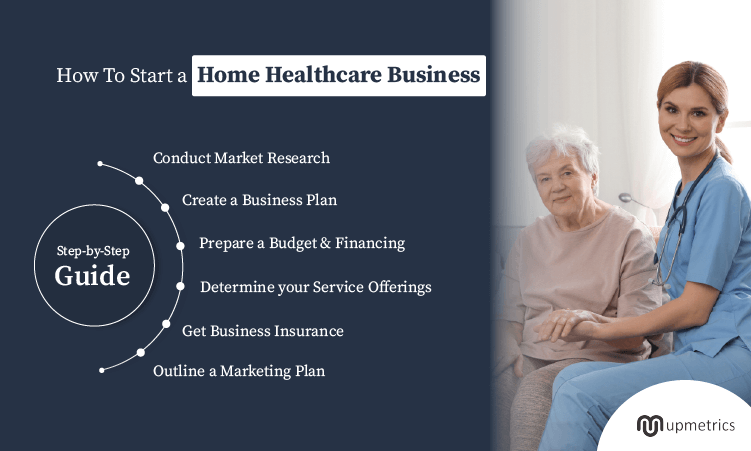

Every successful business has one thing in common, a good and well-executed business plan. A business plan is more than a document, it is a complete guide that outlines the goals your business wants to achieve, including its financial goals . It helps you analyze results, make strategic decisions, show your business operations and growth.

If you want to start a business or already have one and need to pitch it to investors for funding, writing a good business plan improves your chances of attracting financiers. As a startup, if you want to secure loans from financial institutions, part of the requirements involve submitting your business plan.

Writing a business plan does not have to be a complicated or time-consuming process. In this article, you will learn the step-by-step process for writing a successful business plan.

You will also learn what you need a business plan for, tips and strategies for writing a convincing business plan, business plan examples and templates that will save you tons of time, and the alternatives to the traditional business plan.

Let’s get started.

What Do You Need A Business Plan For?

Businesses create business plans for different purposes such as to secure funds, monitor business growth, measure your marketing strategies, and measure your business success.

1. Secure Funds

One of the primary reasons for writing a business plan is to secure funds, either from financial institutions/agencies or investors.

For you to effectively acquire funds, your business plan must contain the key elements of your business plan . For example, your business plan should include your growth plans, goals you want to achieve, and milestones you have recorded.

A business plan can also attract new business partners that are willing to contribute financially and intellectually. If you are writing a business plan to a bank, your project must show your traction , that is, the proof that you can pay back any loan borrowed.

Also, if you are writing to an investor, your plan must contain evidence that you can effectively utilize the funds you want them to invest in your business. Here, you are using your business plan to persuade a group or an individual that your business is a source of a good investment.

2. Monitor Business Growth

A business plan can help you track cash flows in your business. It steers your business to greater heights. A business plan capable of tracking business growth should contain:

- The business goals

- Methods to achieve the goals

- Time-frame for attaining those goals

A good business plan should guide you through every step in achieving your goals. It can also track the allocation of assets to every aspect of the business. You can tell when you are spending more than you should on a project.

You can compare a business plan to a written GPS. It helps you manage your business and hints at the right time to expand your business.

3. Measure Business Success

A business plan can help you measure your business success rate. Some small-scale businesses are thriving better than more prominent companies because of their track record of success.

Right from the onset of your business operation, set goals and work towards them. Write a plan to guide you through your procedures. Use your plan to measure how much you have achieved and how much is left to attain.

You can also weigh your success by monitoring the position of your brand relative to competitors. On the other hand, a business plan can also show you why you have not achieved a goal. It can tell if you have elapsed the time frame you set to attain a goal.

4. Document Your Marketing Strategies

You can use a business plan to document your marketing plans. Every business should have an effective marketing plan.

Competition mandates every business owner to go the extraordinary mile to remain relevant in the market. Your business plan should contain your marketing strategies that work. You can measure the success rate of your marketing plans.

In your business plan, your marketing strategy must answer the questions:

- How do you want to reach your target audience?

- How do you plan to retain your customers?

- What is/are your pricing plans?

- What is your budget for marketing?

How to Write a Business Plan Step-by-Step

1. create your executive summary.

The executive summary is a snapshot of your business or a high-level overview of your business purposes and plans . Although the executive summary is the first section in your business plan, most people write it last. The length of the executive summary is not more than two pages.

Generally, there are nine sections in a business plan, the executive summary should condense essential ideas from the other eight sections.

A good executive summary should do the following:

- A Snapshot of Growth Potential. Briefly inform the reader about your company and why it will be successful)

- Contain your Mission Statement which explains what the main objective or focus of your business is.

- Product Description and Differentiation. Brief description of your products or services and why it is different from other solutions in the market.

- The Team. Basic information about your company’s leadership team and employees

- Business Concept. A solid description of what your business does.

- Target Market. The customers you plan to sell to.

- Marketing Strategy. Your plans on reaching and selling to your customers

- Current Financial State. Brief information about what revenue your business currently generates.

- Projected Financial State. Brief information about what you foresee your business revenue to be in the future.

The executive summary is the make-or-break section of your business plan. If your summary cannot in less than two pages cannot clearly describe how your business will solve a particular problem of your target audience and make a profit, your business plan is set on a faulty foundation.

Avoid using the executive summary to hype your business, instead, focus on helping the reader understand the what and how of your plan.

View the executive summary as an opportunity to introduce your vision for your company. You know your executive summary is powerful when it can answer these key questions:

- Who is your target audience?

- What sector or industry are you in?

- What are your products and services?

- What is the future of your industry?

- Is your company scaleable?

- Who are the owners and leaders of your company? What are their backgrounds and experience levels?

- What is the motivation for starting your company?

- What are the next steps?

Writing the executive summary last although it is the most important section of your business plan is an excellent idea. The reason why is because it is a high-level overview of your business plan. It is the section that determines whether potential investors and lenders will read further or not.

The executive summary can be a stand-alone document that covers everything in your business plan. It is not uncommon for investors to request only the executive summary when evaluating your business. If the information in the executive summary impresses them, they will ask for the complete business plan.

If you are writing your business plan for your planning purposes, you do not need to write the executive summary.

2. Add Your Company Overview

The company overview or description is the next section in your business plan after the executive summary. It describes what your business does.

Adding your company overview can be tricky especially when your business is still in the planning stages. Existing businesses can easily summarize their current operations but may encounter difficulties trying to explain what they plan to become.

Your company overview should contain the following:

- What products and services you will provide

- Geographical markets and locations your company have a presence

- What you need to run your business

- Who your target audience or customers are

- Who will service your customers

- Your company’s purpose, mission, and vision

- Information about your company’s founders

- Who the founders are

- Notable achievements of your company so far

When creating a company overview, you have to focus on three basics: identifying your industry, identifying your customer, and explaining the problem you solve.

If you are stuck when creating your company overview, try to answer some of these questions that pertain to you.

- Who are you targeting? (The answer is not everyone)

- What pain point does your product or service solve for your customers that they will be willing to spend money on resolving?

- How does your product or service overcome that pain point?

- Where is the location of your business?

- What products, equipment, and services do you need to run your business?

- How is your company’s product or service different from your competition in the eyes of your customers?

- How many employees do you need and what skills do you require them to have?

After answering some or all of these questions, you will get more than enough information you need to write your company overview or description section. When writing this section, describe what your company does for your customers.

The company description or overview section contains three elements: mission statement, history, and objectives.

- Mission Statement

The mission statement refers to the reason why your business or company is existing. It goes beyond what you do or sell, it is about the ‘why’. A good mission statement should be emotional and inspirational.

Your mission statement should follow the KISS rule (Keep It Simple, Stupid). For example, Shopify’s mission statement is “Make commerce better for everyone.”

When describing your company’s history, make it simple and avoid the temptation of tying it to a defensive narrative. Write it in the manner you would a profile. Your company’s history should include the following information:

- Founding Date

- Major Milestones

- Location(s)

- Flagship Products or Services

- Number of Employees

- Executive Leadership Roles

When you fill in this information, you use it to write one or two paragraphs about your company’s history.

Business Objectives

Your business objective must be SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.) Failure to clearly identify your business objectives does not inspire confidence and makes it hard for your team members to work towards a common purpose.

3. Perform Market and Competitive Analyses to Proof a Big Enough Business Opportunity

The third step in writing a business plan is the market and competitive analysis section. Every business, no matter the size, needs to perform comprehensive market and competitive analyses before it enters into a market.

Performing market and competitive analyses are critical for the success of your business. It helps you avoid entering the right market with the wrong product, or vice versa. Anyone reading your business plans, especially financiers and financial institutions will want to see proof that there is a big enough business opportunity you are targeting.

This section is where you describe the market and industry you want to operate in and show the big opportunities in the market that your business can leverage to make a profit. If you noticed any unique trends when doing your research, show them in this section.

Market analysis alone is not enough, you have to add competitive analysis to strengthen this section. There are already businesses in the industry or market, how do you plan to take a share of the market from them?

You have to clearly illustrate the competitive landscape in your business plan. Are there areas your competitors are doing well? Are there areas where they are not doing so well? Show it.

Make it clear in this section why you are moving into the industry and what weaknesses are present there that you plan to explain. How are your competitors going to react to your market entry? How do you plan to get customers? Do you plan on taking your competitors' competitors, tap into other sources for customers, or both?

Illustrate the competitive landscape as well. What are your competitors doing well and not so well?

Answering these questions and thoughts will aid your market and competitive analysis of the opportunities in your space. Depending on how sophisticated your industry is, or the expectations of your financiers, you may need to carry out a more comprehensive market and competitive analysis to prove that big business opportunity.

Instead of looking at the market and competitive analyses as one entity, separating them will make the research even more comprehensive.

Market Analysis

Market analysis, boarding speaking, refers to research a business carried out on its industry, market, and competitors. It helps businesses gain a good understanding of their target market and the outlook of their industry. Before starting a company, it is vital to carry out market research to find out if the market is viable.

The market analysis section is a key part of the business plan. It is the section where you identify who your best clients or customers are. You cannot omit this section, without it your business plan is incomplete.

A good market analysis will tell your readers how you fit into the existing market and what makes you stand out. This section requires in-depth research, it will probably be the most time-consuming part of the business plan to write.

- Market Research

To create a compelling market analysis that will win over investors and financial institutions, you have to carry out thorough market research . Your market research should be targeted at your primary target market for your products or services. Here is what you want to find out about your target market.

- Your target market’s needs or pain points

- The existing solutions for their pain points

- Geographic Location

- Demographics

The purpose of carrying out a marketing analysis is to get all the information you need to show that you have a solid and thorough understanding of your target audience.

Only after you have fully understood the people you plan to sell your products or services to, can you evaluate correctly if your target market will be interested in your products or services.

You can easily convince interested parties to invest in your business if you can show them you thoroughly understand the market and show them that there is a market for your products or services.

How to Quantify Your Target Market

One of the goals of your marketing research is to understand who your ideal customers are and their purchasing power. To quantify your target market, you have to determine the following:

- Your Potential Customers: They are the people you plan to target. For example, if you sell accounting software for small businesses , then anyone who runs an enterprise or large business is unlikely to be your customers. Also, individuals who do not have a business will most likely not be interested in your product.

- Total Households: If you are selling household products such as heating and air conditioning systems, determining the number of total households is more important than finding out the total population in the area you want to sell to. The logic is simple, people buy the product but it is the household that uses it.

- Median Income: You need to know the median income of your target market. If you target a market that cannot afford to buy your products and services, your business will not last long.

- Income by Demographics: If your potential customers belong to a certain age group or gender, determining income levels by demographics is necessary. For example, if you sell men's clothes, your target audience is men.

What Does a Good Market Analysis Entail?

Your business does not exist on its own, it can only flourish within an industry and alongside competitors. Market analysis takes into consideration your industry, target market, and competitors. Understanding these three entities will drastically improve your company’s chances of success.

You can view your market analysis as an examination of the market you want to break into and an education on the emerging trends and themes in that market. Good market analyses include the following:

- Industry Description. You find out about the history of your industry, the current and future market size, and who the largest players/companies are in your industry.

- Overview of Target Market. You research your target market and its characteristics. Who are you targeting? Note, it cannot be everyone, it has to be a specific group. You also have to find out all information possible about your customers that can help you understand how and why they make buying decisions.

- Size of Target Market: You need to know the size of your target market, how frequently they buy, and the expected quantity they buy so you do not risk overproducing and having lots of bad inventory. Researching the size of your target market will help you determine if it is big enough for sustained business or not.

- Growth Potential: Before picking a target market, you want to be sure there are lots of potential for future growth. You want to avoid going for an industry that is declining slowly or rapidly with almost zero growth potential.

- Market Share Potential: Does your business stand a good chance of taking a good share of the market?

- Market Pricing and Promotional Strategies: Your market analysis should give you an idea of the price point you can expect to charge for your products and services. Researching your target market will also give you ideas of pricing strategies you can implement to break into the market or to enjoy maximum profits.

- Potential Barriers to Entry: One of the biggest benefits of conducting market analysis is that it shows you every potential barrier to entry your business will likely encounter. It is a good idea to discuss potential barriers to entry such as changing technology. It informs readers of your business plan that you understand the market.

- Research on Competitors: You need to know the strengths and weaknesses of your competitors and how you can exploit them for the benefit of your business. Find patterns and trends among your competitors that make them successful, discover what works and what doesn’t, and see what you can do better.

The market analysis section is not just for talking about your target market, industry, and competitors. You also have to explain how your company can fill the hole you have identified in the market.

Here are some questions you can answer that can help you position your product or service in a positive light to your readers.

- Is your product or service of superior quality?

- What additional features do you offer that your competitors do not offer?

- Are you targeting a ‘new’ market?

Basically, your market analysis should include an analysis of what already exists in the market and an explanation of how your company fits into the market.

Competitive Analysis

In the competitive analysis section, y ou have to understand who your direct and indirect competitions are, and how successful they are in the marketplace. It is the section where you assess the strengths and weaknesses of your competitors, the advantage(s) they possess in the market and show the unique features or qualities that make you different from your competitors.

Many businesses do market analysis and competitive analysis together. However, to fully understand what the competitive analysis entails, it is essential to separate it from the market analysis.

Competitive analysis for your business can also include analysis on how to overcome barriers to entry in your target market.

The primary goal of conducting a competitive analysis is to distinguish your business from your competitors. A strong competitive analysis is essential if you want to convince potential funding sources to invest in your business. You have to show potential investors and lenders that your business has what it takes to compete in the marketplace successfully.

Competitive analysis will s how you what the strengths of your competition are and what they are doing to maintain that advantage.

When doing your competitive research, you first have to identify your competitor and then get all the information you can about them. The idea of spending time to identify your competitor and learn everything about them may seem daunting but it is well worth it.

Find answers to the following questions after you have identified who your competitors are.

- What are your successful competitors doing?

- Why is what they are doing working?

- Can your business do it better?

- What are the weaknesses of your successful competitors?

- What are they not doing well?

- Can your business turn its weaknesses into strengths?

- How good is your competitors’ customer service?

- Where do your competitors invest in advertising?

- What sales and pricing strategies are they using?

- What marketing strategies are they using?

- What kind of press coverage do they get?

- What are their customers saying about your competitors (both the positive and negative)?

If your competitors have a website, it is a good idea to visit their websites for more competitors’ research. Check their “About Us” page for more information.

If you are presenting your business plan to investors, you need to clearly distinguish yourself from your competitors. Investors can easily tell when you have not properly researched your competitors.

Take time to think about what unique qualities or features set you apart from your competitors. If you do not have any direct competition offering your product to the market, it does not mean you leave out the competitor analysis section blank. Instead research on other companies that are providing a similar product, or whose product is solving the problem your product solves.

The next step is to create a table listing the top competitors you want to include in your business plan. Ensure you list your business as the last and on the right. What you just created is known as the competitor analysis table.

Direct vs Indirect Competition

You cannot know if your product or service will be a fit for your target market if you have not understood your business and the competitive landscape.

There is no market you want to target where you will not encounter competition, even if your product is innovative. Including competitive analysis in your business plan is essential.

If you are entering an established market, you need to explain how you plan to differentiate your products from the available options in the market. Also, include a list of few companies that you view as your direct competitors The competition you face in an established market is your direct competition.

In situations where you are entering a market with no direct competition, it does not mean there is no competition there. Consider your indirect competition that offers substitutes for the products or services you offer.

For example, if you sell an innovative SaaS product, let us say a project management software , a company offering time management software is your indirect competition.

There is an easy way to find out who your indirect competitors are in the absence of no direct competitors. You simply have to research how your potential customers are solving the problems that your product or service seeks to solve. That is your direct competition.

Factors that Differentiate Your Business from the Competition

There are three main factors that any business can use to differentiate itself from its competition. They are cost leadership, product differentiation, and market segmentation.

1. Cost Leadership

A strategy you can impose to maximize your profits and gain an edge over your competitors. It involves offering lower prices than what the majority of your competitors are offering.

A common practice among businesses looking to enter into a market where there are dominant players is to use free trials or pricing to attract as many customers as possible to their offer.