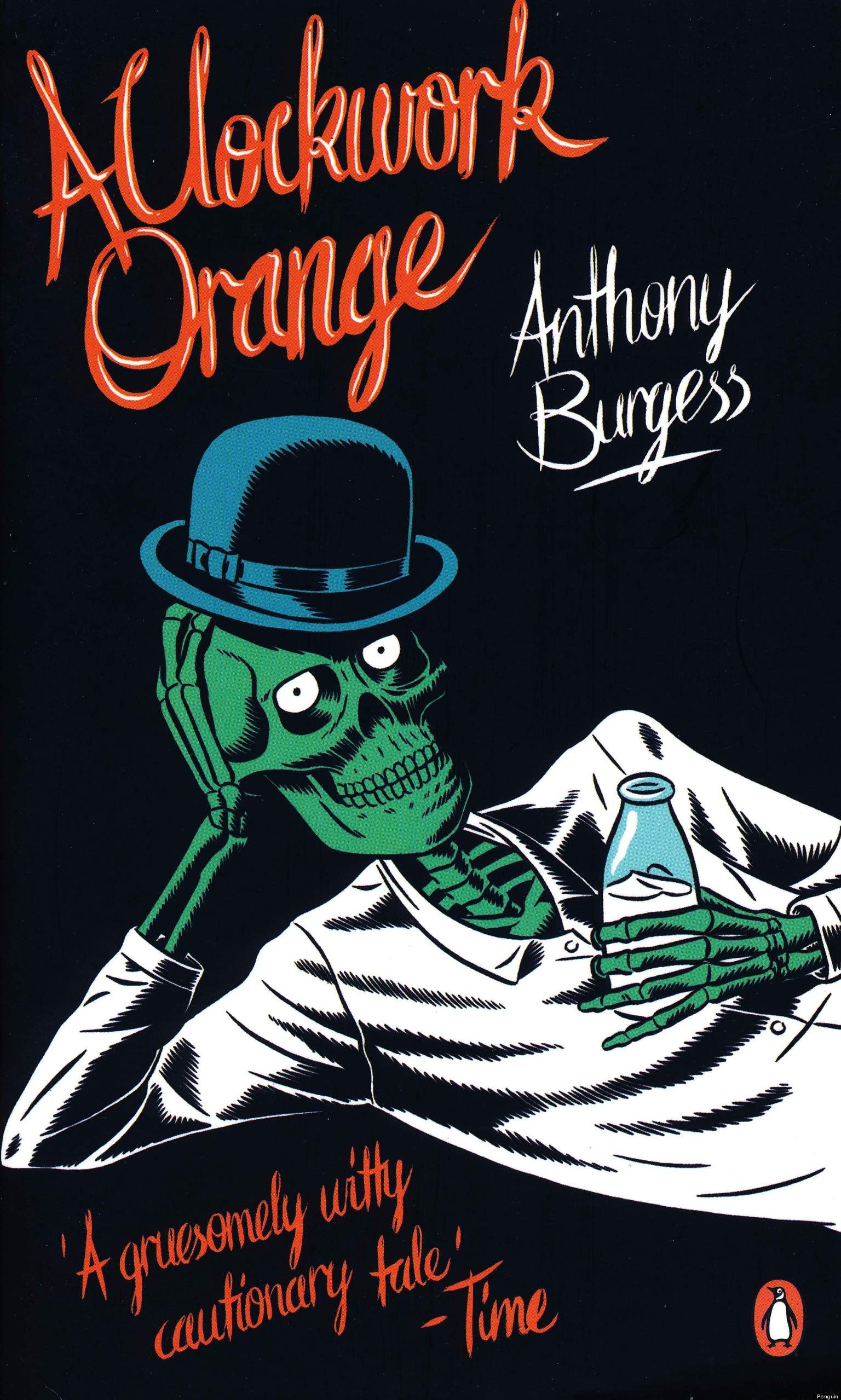

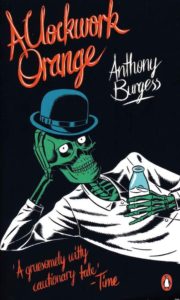

A Clockwork Orange

By anthony burgess.

A Clockwork Orange follows Alex, a young gang leader who, along with his companions, runs the streets committing the worst crimes imaginable.

About the Book

Written by Emma Baldwin

B.A. in English, B.F.A. in Fine Art, and B.A. in Art Histories from East Carolina University.

Burgess openly addresses this violence which is often physical and sexual and contrasts it against the oppressed and controlled lives of other citizens of the novel.

Alex’s view of the world is nightmarish and will likely disturb a large percentage of readers. But, it’s also presented as a necessary evil in a world where free will and human nature are on the verge of being entirely stopped by a burgeoning totalitarian state.

The novel was incredibly influential in the years after it was published, gaining a cult and then mainstream following, especially after the filming of ‘ A Clockwork Orange ‘ movie, directed by Stanley Kubrick. The film went on to influence visual and musical artists as well as fashion designers and other filmmakers. Burgess’s novel was a game-changer, redefining what the genre of dystopia could accomplish.

Violence in A Clockwork Orange

All that being said, this novel isn’t for everyone. It’s incredibly violent, driven in sections by Alex’s willingness and desire to harm other people. He is fueled by a need to break with the rules society sets for him, and in doing so, he commits acts that are likely going to bother readers. This novel is not for those troubled by descriptions of violence nor for young readers who are not yet mature enough to handle it. This is furthered by the fact that in many passages, violence is treated artistically. Alex sees it as an expression of his inner self. It is treated as something aesthetic and something to be admired. Here is a great example of the way that violence is treated:

Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders. And then, a bird of like rarest spun heavenmetal, or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now, came the violin solo above all the other strings, and those strings were like a cage of silk round my bed. Then flute and oboe bored, like worms of like platinum, into the thick thick toffee gold and silver. I was in such bliss, my brothers.

Words like “gorgeosity” and “silverflamed” in addition to “silvery win,” “wonder of wonders,” “thick thick toffee gold and silver” are all

The Use of Nadsat in A Clockwork Orange

His horrific acts are only partially disguised by the use of Nadsat, requiring some translation on the reader’s part. The use of slang in the novel is something that also turns away some readers. The novel starts with the following quote :

‘What’s it going to be then, eh?’ There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim. Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry. The Ko Part 1 rova Milkbar was a milk-plus mesto, and you may, O my brothers, have forgotten what these mestos were like, things changing so skorry these days and everybody very quick to forget, newspapers not being read much neither.

There is an immediate barrier to entry with this novel. Readers are met with new words, ones that require context to understand. It may take pages or even chapters for one to figure out what words like “mestos” and “droogs” mean. This was, of course, intentional on Burgess’s part. He even fought with publishers to keep a glossary of terms from being published as part of the novel. He wanted readers to work to figure these words out. This means, though, that the first pages of the book are hard to get through. It requires perseverance to read pages of text that don’t entirely make sense. But, the language and what does come through amongst the Nadsat is interesting enough to compel most readers onward.

As the novel progresses, it gets easier and easier to figure out what the slang means. By the end of the book, the language appears almost normal. That is until Burgess includes dialogue from an adult and readers are returned to the world of contemporary English. While the slang presents positives and negatives, it can’t be denied that it does a great job of transporting readers into the world of ‘ A Clockwork Orange ‘ . With these new and strange words, Alex’s thoughts are distorted and made even harder to comprehend than they otherwise would’ve been.

After the novel was published, Anthony Burgess famously referred to it as “too didactic” to be considered art. Although some have issues with the book, this is a statement that very few readers and critics agree with today.

What’s so special about A Clockwork Orange?

When it comes to the book, Burgess attempted a type of writing and a storyline that had never been attempted before. He used language the reader was not meant to understand, relished in the ultra-violence of his main character, and focused on a series of characters who are all unlikeable. The novel transports readers to a different world, one that’s as compelling as it is nightmarish.

Why was the book A Clockwork Orange banned?

The book was and still is, banned in some schools and other intuitions due to its depictions of violence, physical and sexual violence. The novel is fueled by these passages and without them, it would lose much of what makes it worth reading. Alex’s violent acts are at the centre of the discussion of free will versus control.

What is the ending of A Clockwork Orange ?

The ending is different depending on which version of the novel you’re reading. In some American versions, the final chapter in which Alex reforms himself is omitted. In others, readers learn that Alex stops his violent acts and turns his mind toward finding a wife and having a son.

Was A Clockwork Orange based on a true story?

No, not entirely. There is one incident in the novel that may have been based on a similar event in Burgess’s life, an attack on his wife during a WWII blackout. But, aside from that, the world of ‘ A Clockwork Orange ‘ is entirely fictional.

A Clockwork Orange: Burgess' Violent Masterpiece

- Writing Style

- Lasting Effect on Reader

A Clockwork Orange Review

A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess’ best-known novel. It follows Alex, a violent and seemingly irredeemable protagonist who is subjected to a brainwashing experiment at the hands of the State. No longer able to think violent thoughts, he serves as a lesson of the importance of free will.

- Incredibly creative writing style

- One of a kind dialogue

- Memorable characters

- Nadsat is challenging to read

- Very violent

- Characters are unlikeable

About Emma Baldwin

Emma Baldwin, a graduate of East Carolina University, has a deep-rooted passion for literature. She serves as a key contributor to the Book Analysis team with years of experience.

Cite This Page

Baldwin, Emma " A Clockwork Orange Review ⭐ " Book Analysis , https://bookanalysis.com/anthony-burgess/a-clockwork-orange/review/ . Accessed 1 April 2024.

It'll change your perspective on books forever.

Discover 5 Secrets to the Greatest Literature

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Tiger Riding for Beginners

Bernie gourley: traveling poet-philosopher & aspiring puddle dancer.

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.

- A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess" data-content="https://berniegourley.com/2017/08/22/book-review-a-clockwork-orange-by-anthony-burgess/" title="Share on Tumblr">Share on Tumblr

4 thoughts on “ BOOK REVIEW: A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess ”

I loved the movie and I’ve always wanted to read this book but for some unknown reasons I’ve never bought it. Thank you for this review, I’ll add this book to my loooong (and never-ending) list 😻

I loved the movie and I’ve always wanted to read this book but for some unknown reasons I’ve never bought it. Thank you for this review, I’ll add this book to my loooong (and never-ending) list 🙂

Pingback: A Clockwork Orange | Science Book a Day

Pingback: A Clockwork Orange | My Pretty Site

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Nov 5, 2020

Review: A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

Well you can't get more classic than A Clockwork Orange . I continuously watched the movie when I was a teenager; safe to say I had a sick curiosity about witnessing a character that was so purely evil such as Alex. After some research, I learnt that the meaning of the term 'a clockwork orange' is to describe something as solely one thing - for example, solely good or solely evil. This book certainly demonstrates the frantic mind of someone who is solely evil.

In this horrifying dystopian future, criminals take over after dark. Teen gang leader, Alex, narrates in highly inventive slang that echoes the violent intensity of the youth rebelling against society. A Clockwork Orange is a frightening fable about good and evil and the meaning of human freedom.

I decided to listen to this book as an audiobook. I initially tried reading the text and felt it was a real struggle to interpret the language. Due to the amount of words and phrases that are replaced with slang and the text almost being written in an accent, seeing the story on paper was disabling me from getting any enjoyment from it. I quickly made the media switch and I'm so happy that I did. With an actor doing all the work for you, the accent and slang only added to the story. It felt like a language of absolute madness - frantic, nonsensical and relentless. With the story being told by main character, Alex, he often addresses the reader. His speech gives off a real sense of mental unrest and a lack of caring about his actions. He consistently talks with humour, and no empathy.

One of the most interesting parts to this book (to me, anyway) was the introduction; a letter to the reader from Anthony Burgess, written years after the acclaim of the book as well as the movie had reached its peak. In the letter, Burgess speaks of his disappointment to the fame of the novel. As with any great artist, it is not uncommon that one piece of their work will always be associated with them, and all their other feats will be forgotten and under appreciated. He also goes into detail about the differences between the British and American versions. The British publishers felt it was essential to include the final chapter, showing Alex's growth as a person - he ages and eventually finds violence dull. However, in the US, the publishers felt that the Americans could handle what the British couldn't - a character that truly is evil through and through, never reflects and never improves. Perhaps this is proved again by American Classics from Brett Easton Ellis?

Overall, I think this was a fantastic audiobook - a vision was truly brought to life where you can appreciate the levels of madness that Burgess was trying to convey through his protagonist. The violence is non-stop, and despite it being very constant and brutish, having it narrated by a main character that is oblivious to the horror of his actions, means everything is put forward in a nonchalant tone; take that as you will - maybe that makes it even more horrifying to read...

Initial Prediction : 3.5 stars

Final Rating : 4 stars

Publication Date : 1962 (my edition: 24 February 2000)

Publisher : Penguin Books

Genres : Science Fiction, Dystopian, Horror

# of Pages : 159

Links : Goodreads , Amazon

Recent Posts

Review: The Martian by Andy Weir

Review: The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi

Review: Tender is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica

Yes! I wouldn't even bother with the physical copy. Everyone that I've spoken with that tried the physical copy only didn't like it and gave up before finishing. The version on audible (50 year anniversary) is the one to go for!

Oooh I'm always up for listening to classics as audiobook. Absolutely want to give this one a go now!

Advertisement

Supported by

The Shock of the New

- Share full article

By Martin Amis

- Aug. 31, 2012

The day-to-day business of writing a novel often seems to consist of nothing but decisions — decisions, decisions, decisions. Should this paragraph go here? Or should it go there? Can that chunk of exposition be diversified by dialogue? At what point does this information need to be revealed? Ought I use a different adjective and a different adverb in that sentence? Or no adverb and no adjective? Comma or semicolon? Colon or dash? And so on.

These decisions are minor, clearly enough, and they are processed more or less rationally by the conscious mind. All the major decisions, by contrast, have been reached before you sit down at your desk; and they involve not a moment’s thought. The major decisions are inherent in the original frisson — in the enabling throb or whisper (a whisper that says, Here is a novel you may be able to write). Very mysteriously, it is the unconscious mind that does the heavy lifting. No one knows how it happens.

When, in 1960, Anthony Burgess sat down to write “A Clockwork Orange,” we may be pretty sure that he had a handful of certainties about what lay ahead of him. He knew the novel would be set in the near future (and that it would take the standard science-fictional route, developing, and fiercely exaggerating, current tendencies). He knew his vicious antihero, Alex, would narrate, and that he would do so in an argot or idiolect the world had never heard before (he eventually settled on a blend of Russian, Romany and rhyming slang). He knew it would have something to do with Good and Bad, and Free Will. And he knew, crucially, that Alex would harbor a highly implausible passion: an ecstatic love of classical music.

We see the wayward brilliance of that last decision when we reacquaint ourselves, after half a century, with Burgess’ leering, sneering, sniggering, sniveling young sociopath (a type unimprovably caught by Malcolm McDowell in Stanley Kubrick’s uneven but justly celebrated film). “It wasn’t me, brother, sir” Alex whines at his social worker, who has hurried to the local jailhouse: “Speak up for me, sir, for I’m not so bad.” But Alex is so bad; and he knows it. The opening chapters of “A Clockwork Orange” still deliver the shock of the new: a red streak of gleeful evil.

On a night on the town Alex and his droogs (partners in crime) waylay a schoolmaster, rip up the books he is carrying, strip off his clothes and stomp on his dentures; they rob and belabor a shopkeeper and his wife (“a fair tap with a crowbar”); they give a drunken bum a kicking (“we cracked into him lovely”); and they have a ruck with a rival gang, using the knife, the chain, the straight razor. Next, they steal a car, cursorily savage a courting couple, break into a cottage owned by “another intelligent type bookman type like that we’d fillied with some hours back,” destroy the typescript of his work in progress and gang rape his wife. And all this has been accomplished by the time we reach Page 20.

In a brief hiatus between storms of “ultra-violence,” Alex goes home to Municipal Flatblock 18A. Here, for a change, he does nothing worse than keep his parents awake by playing the multi-speaker stereo in his room, listening to a new violin concerto, before moving on to Mozart and Bach. Burgess evokes Alex’s sensations in a bravura passage that owes less to nadsat, or teenage pidgin, and more to the modulations of “Ulysses”:

“The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders.”

Here we feel the power of that enabling throb or whisper — the authorial insistence that the Beast would be susceptible to Beauty. At a stroke, and without sentimentality, Alex is realigned. He has now been equipped with a soul, and even a suspicion of innocence. Burgess airs the sinister but not implausible suggestion that Beethoven and Birkenau didn’t merely coexist. They combined and colluded, inspiring mad dreams of supremacism and omnipotence.

In Part 2, violence comes, not from below, but from above: it is the “clean” and focused violence of the state. Having served two years of his sentence, the entirely incorrigible Alex is selected for a crash course of a Reclamation Treatment, a form of aversion therapy. Each morning he is injected with a strong emetic and wheeled into a screening room, where his head is clamped in a brace and his eyes pinned wide open. Alex is then obliged to watch familiar scenes of recreational mayhem, lingering mutilations, Japanese tortures and finally a newsreel, with eagles and swastikas, firing squads, naked corpses. The soundtrack of the last clip is Beethoven’s Fifth. From now on Alex will feel intense nausea, not only when he contemplates violence, but also when he hears Ludwig van and the other starry masters. His soul, such as it was, has been excised.

We now embark on the curious apologetics of Part 3. “Nothing odd will do long,” said Dr. Johnson — meaning that the reader’s appetite for weirdness is very quickly surfeited. Burgess (unlike, say, Kafka) is sensitive to this near-infallible law; but there’s a case for saying that “A Clockwork Orange” ought to be even shorter than its 141 pages. It was in fact published with two different endings. The American edition omits the final chapter (this is the version used by Kubrick) and closes with Alex recovering from what proves to be a cathartic suicide attempt. He is listening to Beethoven’s Ninth:

“When it came to the Scherzo I could viddy myself very clear running and running on like very light and mysterious nogas, carving the whole litso of the creeching world with my cut-throat britva. And there was the slow movement and the lovely last singing movement still to come. I was cured all right.”

This is the “dark” ending. In the official version, though, Alex is afforded full redemption. He simply — and bathetically — “outgrows” the atavisms of youth, and starts itching to get married and settle down; and he carries around with him a photo of “a baby gurgling goo goo goo.” We are asked to accept that Alex has turned all soft and broody — at the age of 18.

It feels like a startling loss of nerve on Burgess’ part, or a recrudescence (we recall that he was an Augustinian Catholic) of self-punitive guilt. Horrified by its own transgressive energy, the novel submits to a Reclamation Treatment sternly supplied by its author. Burgess knew something was wrong: “a work too didactic to be artistic,” he half-conceded, “pure art dragged into the arena of morality.” And he shouldn’t have worried: Alex may be a teenager, but readers are grown-ups, and are perfectly at peace with the unregenerate. Besides, “A Clockwork Orange” is in essence a black comedy. Confronted by evil, comedy feels no need to punish or correct. It answers with corrosive laughter.

In his 1973 book on Joyce, “Joysprick,” Burgess made a provocative distinction between what he calls the “A” novelist and the “B” novelist: the A novelist is interested in plot, character and psychological insight, whereas the B novelist is interested, above all, in the play of words. The most famous B novel is “Finnegans Wake,” which Nabokov aptly described as “a cold pudding of a book, a persistent snore in the next room.” The B novel, as a genre, is now utterly defunct; and “A Clockwork Orange” may be its only long-term survivor. It is a book that can still be read with steady pleasure, continuous amusement and — at times — incredulous admiration. Anthony Burgess, then, is not “a minor B novelist,” as he described himself; he is the only B novelist. I think he would have settled for that.

Martin Amis is the author, most recently, of “Lionel Asbo: State of England.” This essay is adapted from his introduction to a new 50th-anniversary edition of “A Clockwork Orange” published in Britain by William Heinemann.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

James McBride’s novel sold a million copies, and he isn’t sure how he feels about that, as he considers the critical and commercial success of “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.”

How did gender become a scary word? Judith Butler, the theorist who got us talking about the subject , has answers.

You never know what’s going to go wrong in these graphic novels, where Circus tigers, giant spiders, shifting borders and motherhood all threaten to end life as we know it .

When the author Tommy Orange received an impassioned email from a teacher in the Bronx, he dropped everything to visit the students who inspired it.

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

A Clockwork Orange comes under the heading of "books you feel you ought to have read by now". Mostly these are books that you don't necessarily want to read, but are considered such classics that an inability to pass any kind of comment upon them suggests a gaping hole in your education.

Like most people I had heard of "Clockwork Orange" primarily via Kubrick's 1971 film, but I hadn't even seen that. I had only the vaguest idea of what was going on.

Were he still with us Burgess might be disheartened or, maybe, ironically pleased that having read the book, my idea is still somewhat vague.

The basic plot is that at fifteen Alex is a nasty piece of work, with an evil bunch of friends. Sorry, but the word delinquent just doesn't cover it. These guys torture and kill just for the kicks, and then go home to their families, who are genuinely frightened of them, sleep, get up and go to school. Eventually, obviously, something is bound to go wrong and our anti-hero finds himself in prison. Prison life comes as something as shock to the youngster – there are people even worse than he is – plus he finds he misses the outside (who'd a thought?) – so when he's offered a solution, a "cure", that will see him released within the fortnight rather than in fourteen years time, he jumps at it. That's when it all goes wrong.

So far, no spoilers. All of this is on the blurb. Which is a shame; because the Ludovico experiment (the cure) doesn't crop until about three quarters of the way through the book. Sometimes publishers do tell too much. Forget the age of the book, forget the films and the internet, some of us still come to books not knowing the premise! When will they learn?

In some sense, you could argue that knowing the plot in advance doesn't really matter, because nearly fifty years on, it's almost the least interesting point about it. The Ludovico technique might have been something strange and new back in 1962, but the basic principle is now common therapy for all sorts of unwanted activity. Perhaps without such extreme results it must be said.

Right there is a point for discussion. When does therapy become mind-control? Where are the boundaries?

Then there is the society which Burgess has imagined. The sudden arrival of this new being "the teenager" in the late fifties / early sixties created all kinds of horrific projections of delinquent young rebels taking over the world, scorning "society" and holding ordinary folk a communal hostage. Dystopia. When the mods and rockers fought it out on Brighton sea front (or wherever) it was clearly the way the world was going. Yet we seem to have survived.

There are pockets of violence and control, both geographically (there are some districts in some cities where you really don't want to be alone on a dark night, or maybe even a bright afternoon in the wrong clothes) and chronologically (otherwise peaceful neighbourhoods suddenly erupt in riots and destruction, but then settle down again to a normal life). The closed-in nature of Burgess's novella is that it is never clear whether the society he depicts is global, national, or just a few unfortunate estates in one or two Boroughs.

That there are gangs of Alex's disposition wandering our streets today, I have no doubt. But not every street. And, frankly, I think there probably always were, always will be. Somewhere. For a while. Some will get caught. Some will pay a bigger price. Some will grow out of it.

That last is a point that also isn't lost on the author.

If the violence alone doesn't make Clockwork Orange a difficult enough read – and Burgess doesn't pull his punches, so it isn't for the squeamish – then the language does. Children have always made up languages by adding in syllables or simply talking gibberish to which they assign meaning within their clique. With the growth of teen culture this tendency took on a new dimension. Teen slang was already growing out of the music culture and the beat generation by the time the book was written, but the linguist Burgess takes the idea to its extreme. He creates something approaching a whole new language.

He calls it "nadsat" – which is almost a direct Russian parallel to the English "-teen" suffix. Many of the words used are borrowed from Russian, others are from cockney rhyming slang (or derived from that premise), there's the occasional German and some clear inventions of the author. It takes a long while to settle into reading this. The natural reaction is to struggle over what the words mean. Eventually though, like a child learning a new language, as a reader you stop worrying about it. You either know exactly what the word means and so translate it instantly, you have a rough idea which you assume is more or less right, or you haven't a clue so you skim over it in the hope that it isn't important. With each repetition of the word, your understanding of it becomes clearer.

The theory is that Burgess did this because he wanted to give his narrator a very distinctive voice, and one that would not become dated as genuine slang tends to do. I cannot help wondering however whether there wasn't a wider experiment at work, to see if people would respond as I've indicated above, and read it anyway, and not necessarily learn the slang to speak it, but sufficiently to understand it by the end of the book. I'm intrigued as to whether he sought feedback from his readers.

In this area, I think that his prescience is stronger than in others. Consider the growth of text-speak and gangsta-rap. Jargon generally is on the increase. It is possible to overhear a conversation in your native tongue these days and not follow a sentence of it. In one specific he comes close to the mark. "My brothers" Alex addresses his gang and us, his readers. Uncomfortably close "Bro!" you might think.

When it comes to characterisation, Alex is the only person we get a truly complete vision of. Everyone else simply fulfils a role. Then again, it's Alex talking, and that is probably how he sees them too. As for Alex, he is thoroughly detestable. Manipulative. Just plain nasty. If you read closely, there is no point at which he shows any glimmer of what some might call "humanity".

Burgess wrote the book in three parts, each of seven "chapters". He is on record as saying that the number 21 was symbolic – being, at the time, the age of maturity. Yet when the book was published in America the final chapter was omitted. The U.S. publishers (and indeed Kubrick when he finally saw it) felt that it did not ring true with the rest of the book. I can only suggest that they should have read both that last chapter and the rest of the book more closely. Redemption? Not the way I read it.

So: should you read it? On balance I think "yes" – but I have to temper that by saying, "but not necessarily for fun!"

I did not enjoy the book in the slightest. I found it hard work and intensely distasteful. But the more I think about it, the more I realise that it is a clever piece of literature that deserves to be read and thought about and discussed. I almost wish it was one of those we were given to dissect at school. It is full of strong ideas and subtle ones.

And it is only 140 pages long. You can keep the concentration up for that span.

I'd like to thank the publishers for sending a copy to the Bookbag.

Further reading suggestion: for another classic look at a dystopian future try Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (aka Blade Runner).

Like to comment on this review?

Just send us an email and we'll put the best up on the site.

- Anthony Burgess

- Reviewed by Lesley Mason

- 4 Star Reviews

- Literary Fiction

Navigation menu

Page actions.

- View source

Personal tools

- Non-fiction

- Children's books

- New reviews

- Recommendations

- New features

- Competitions

- Forthcoming publications

- Random review

- Social networks

- For authors and publishers

- Self-publishing and indie authors

- Copyright and privacy policy

- Advertise with us

- Reviewer vacancies

We Buy Books

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- This page was last edited on 23 March 2018, at 14:55.

- Privacy policy

- About TheBookbag

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

by Anthony Burgess & edited by Mark Rawlinson ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 8, 1962

The previous books of this author ( Devil of a State, 1962; The Right to an Answer, 1961) had valid points of satire, some humor, and a contemporary view, but here the picture is all out—from a time in the future to an argot that makes such demands on the reader that no one could care less after the first two pages. If anyone geta beyond that—this is the first person story of Alex, a teen-age hoodlum, who, in step with his times, viddies himself and the world around him without a care for law, decency, honesty; whose autobiographical language has droogies to follow his orders, wallow in his hate and murder moods, accents the vonof human hole products. Betrayed by his dictatorial demands by a policing of his violence, he is committed when an old lady dies after an attack; he kills again in prison; he submits to a new method that will destroy his criminal impulses; blameless, he is returned to a world that visits immediate retribution on him; he is, when an accidental propulsion to death does not destroy him, foisted upon society once more in his original state of sin. What happens to Alex is terrible but it is worse for the reader.

Pub Date: Jan. 8, 1962

ISBN: 0393928098

Page Count: 357

Publisher: Norton

Review Posted Online: Nov. 2, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 1962

GENERAL FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Anthony Burgess

BOOK REVIEW

by Anthony Burgess

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2015

Kirkus Prize winner

National Book Award Finalist

A LITTLE LIFE

by Hanya Yanagihara ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 10, 2015

The phrase “tour de force” could have been invented for this audacious novel.

Four men who meet as college roommates move to New York and spend the next three decades gaining renown in their professions—as an architect, painter, actor and lawyer—and struggling with demons in their intertwined personal lives.

Yanagihara ( The People in the Trees , 2013) takes the still-bold leap of writing about characters who don’t share her background; in addition to being male, JB is African-American, Malcolm has a black father and white mother, Willem is white, and “Jude’s race was undetermined”—deserted at birth, he was raised in a monastery and had an unspeakably traumatic childhood that’s revealed slowly over the course of the book. Two of them are gay, one straight and one bisexual. There isn’t a single significant female character, and for a long novel, there isn’t much plot. There aren’t even many markers of what’s happening in the outside world; Jude moves to a loft in SoHo as a young man, but we don’t see the neighborhood change from gritty artists’ enclave to glitzy tourist destination. What we get instead is an intensely interior look at the friends’ psyches and relationships, and it’s utterly enthralling. The four men think about work and creativity and success and failure; they cook for each other, compete with each other and jostle for each other’s affection. JB bases his entire artistic career on painting portraits of his friends, while Malcolm takes care of them by designing their apartments and houses. When Jude, as an adult, is adopted by his favorite Harvard law professor, his friends join him for Thanksgiving in Cambridge every year. And when Willem becomes a movie star, they all bask in his glow. Eventually, the tone darkens and the story narrows to focus on Jude as the pain of his past cuts deep into his carefully constructed life.

Pub Date: March 10, 2015

ISBN: 978-0-385-53925-8

Page Count: 720

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: Dec. 21, 2014

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 2015

More by Hanya Yanagihara

by Hanya Yanagihara

PERSPECTIVES

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

by Harper Lee ‧ RELEASE DATE: July 11, 1960

A first novel, this is also a first person account of Scout's (Jean Louise) recall of the years that led to the ending of a mystery, the breaking of her brother Jem's elbow, the death of her father's enemy — and the close of childhood years. A widower, Atticus raises his children with legal dispassion and paternal intelligence, and is ably abetted by Calpurnia, the colored cook, while the Alabama town of Maycomb, in the 1930's, remains aloof to their divergence from its tribal patterns. Scout and Jem, with their summer-time companion, Dill, find their paths free from interference — but not from dangers; their curiosity about the imprisoned Boo, whose miserable past is incorporated in their play, results in a tentative friendliness; their fears of Atticus' lack of distinction is dissipated when he shoots a mad dog; his defense of a Negro accused of raping a white girl, Mayella Ewell, is followed with avid interest and turns the rabble whites against him. Scout is the means of averting an attack on Atticus but when he loses the case it is Boo who saves Jem and Scout by killing Mayella's father when he attempts to murder them. The shadows of a beginning for black-white understanding, the persistent fight that Scout carries on against school, Jem's emergence into adulthood, Calpurnia's quiet power, and all the incidents touching on the children's "growing outward" have an attractive starchiness that keeps this southern picture pert and provocative. There is much advance interest in this book; it has been selected by the Literary Guild and Reader's Digest; it should win many friends.

Pub Date: July 11, 1960

ISBN: 0060935464

Page Count: 323

Publisher: Lippincott

Review Posted Online: Oct. 7, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: July 1, 1960

More by Harper Lee

by Harper Lee

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

I should infinitely prefer a book — A Clockwork Orange Book Review

See, that’s what the app is perfect for..

I should infinitely prefer a book

A clockwork orange book review.

Fifteen-year-old Alex and his thrill-seeking gang regularly indulge in ultra-violence, rape and drugs, but when he is caught and brainwashed by a government psychologist Alex finds his new law-abiding life unbearable. Set in a terrifying dystopian future, A Clockwork Orange is a disturbing exploration of morality and free will.

Rating: ★★★ ½

I enjoyed A Clockwork Orange much more than I thought I would after briefly scanning it and reading all of the strange language. I read this novel in preparation for seeing a performance of it, so I was determined to get through it, even though I struggled a little at first. It takes a bit of time, but if you have a glossary with you (I used one on Sparknotes), you get used to the slang and slowly start to remember what the words mean. Eventually, you’ll hopefully feel no need to translate every slang word and you’ll be able to understand the narrative on its own terms.

The language also lessens the horror of the violence committed by Alex and his gang – even when this violence is described with details, it doesn’t appear to be graphic because it is somewhat concealed by the words used. But although A Clockwork Orange contains violence in multitudes, it does not glorify violence. It’s not even really a book about violence, rather, it is about free will and a person’s ability to exercise it. Of the moral and ethical questions presented throughout the novel, some are less convincing than others, although on the whole the shades of grey are brilliantly displayed.

Famously, both American publishers and the Kubrick film omitted the final chapter, in which Alex decides he cannot continue to live a life full of violence. I for one cannot comprehend this move, because the final chapter validates the entire purpose of the novel. However, although I prefer the inclusion of the final chapter, I am not convinced by all of its conclusions – specifically that the desire for violence is solved by maturity.

See more posts like this on Tumblr

More you might like

JOMP Book Photo Challenge

March 27 - Flowers 💐

sunflower & next read

Mexican Gothic ✨✨

there's no greater betrayal than finally starting to read a book you've had sitting for months on your shelf or your desk or your nightstand and then finding out it's bad. like. i gave you a fucking home.

I mean it when I say that my reading list is longer than my life expectancy.

I’m not bitter

I am bitter

Literally every movie adaptation ever: Henry Jeckyll is just a poor victim of his evil side Mr Hyde!

The Actual Book: Henry Jeckyll is a weird fuck who turned himself into a monster man because he wanted to indulge in doing horrible things without fear of getting caught

Add the phantom of the Opera !

If you allow me-

They did the mash….

something about foreshadowing being more prominent the second time around reading a story but in a way that the meaning is changed forever and you can never view a story the same as you once did before. do you know what i mean.

literally so insane how you can never go back to the innocence of it all. you see all the signs coming and you know how it ends. but there's nothing you can do to turn a blind eye to it anymore. it hits you and you just have to keep going.

So turns out…..you guys are not gonna believe this…….but it turns out. Reading real books. Is good for you actually.

Let me be completely clear - I’m not being a sarcastic ass. I’m just realizing all over again, in real time, for myself, that reading a real life published book makes your neurons feel like they’re getting a spa day. Like I can feel my brain getting juicer and wrinklier with every page I turn. This shit is no joke, this is like hard drugs if hard drugs were good for you and made your brain feel revived and alive.

when you start reading again and it's like oh. oh . the sun actually does still shine.

the chronicles of narnia should be read in. . .

publication order

chronological order

publication: the lion, the witch and the wardrobe, prince caspian, the voyage of the dawn treader, silver chair, the horse and his boy, the magician's nephew, the last battle

chronological: the magician's nephew, the lion, the witch, and the wardrobe, the horse and his boy, prince caspian, the voyage of the dawn treader, silver chair, the last battle

Publication order!!! I just filmed a whole ass hour and fifteen minute video that talked about why. I will die on this hill.

i knew i could trust you

I'm rather disappointed that chronological is leading. I'm hoping it's just because that's how the publisher numbers them. (But sometimes publishers, and even the authors themselves, are just Wrong.)

Here's the link if you want to check it out!

I'm glad to see things are now being put to rights.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

A Clockwork Orange review – Kubrick's sensationally scabrous thesis on violence

This outlandish tale of dystopian delinquency remains deeply thought-provoking – but is not without troublesome elements

T he souring of the swinging 60s got properly under way with this radioactively outrageous film, now rereleased as part of the Stanley Kubrick season at London’s BFI Southbank; this was Kubrick’s sensationally scabrous, declamatory, epically indulgent and mad adaptation of the 1962 Anthony Burgess novella about ultra-violent youth gangs in a dystopian future Britain speaking cod-Russian mixed with a weird version of Cockney rhyming slang. (Burgess cheekily trolled the public by claiming his title was taken from a certain Cockney phrase – “queer as a clockwork orange” – apparently known only to him.)

In place of peace and love and prosperity, A Clockwork Orange offered a new zeitgeist-decade of violence, anger, misogyny, the degradation of the public space in dreary suburban locales and modernist designs for living that had been vandalised. John Barry’s production design showed us “ ruin porn ” before the phrase had been invented.

All of the film’s provocation and jaded sexual politics are flavoured with histrionic cynicism and disillusion. It was self-banned by Kubrick: withdrawn by Warner Bros from UK distribution at the director’s insistence, an extraordinary example of director power over a studio. Kubrick had been badly shaken by press reports of real-life crimes supposedly inspired by the film. The ban remained theoretically in force until Kubrick’s death in 1999, although in the 90s it was easy enough to get hold of imported DVDs from the US, which is how I first saw it.

It is strange to watch A Clockwork Orange again, in my case for the first time in 20 years. It is still brilliant, still audacious, still nasty, but definitely dated, and longer than I remembered. Kubrick’s use of pop-classical scores can seem unvarying and strident, and less interesting than in 2001: A Space Odyssey . But his signature is there all the way through, especially in the establishing shots of cavernous interiors, with their vertiginous lines disappearing into the distance. What is also there is Kubrick’s definite weakness for softcore nudity, a definite liking for showing unclothed young women in decoratively pretty ways, which makes his depiction of rapes uncomfortable, although the offence is intentionally contrived. The nasty cutting of breast-shaped holes in the woman’s top in the first rape scene is bizarrely duplicated in the second: the woman has a painting on her wall of a woman with a similarly scissored outfit.

The fundamental premise is still potent: a young “droog” called Alex, brilliantly played by Malcolm McDowell, leads a gang of delinquents in acts of grotesque violence – which is turned on him when he is captured and forced to endure a clinical remedial torture. The swaggering assailant is made to watch upsetting films as aversion therapy with his eyelids clipped wide open and lubricated with an eyedropper – a genuinely horrifying scene, something to match the eye-slitting in Un Chien Andalou . But the use of Beethoven on the soundtrack causes Alex to hate not just rape and violence but also Beethoven’s music, which had been the love of his life and his one redeeming feature.

This turning of the tables, this challenge to our liberal sensibilities, is what makes A Clockwork Orange powerful: a sudden widening of the perspective on violence. Should we feel sympathy for Alex, or scorn for his richly deserved agony? If we are invited to feel nothing at all, then our very blankness, our neutrality, is our ordeal. I have watched many violent films by directors who have clearly been influenced by A Clockwork Orange, but it is as if they have only seen the first half. They have violent scenes, violent people, violent acts … and it leads nowhere. The shock just reverberates up to the next shock. Kubrick created irony and satire from his ultra-violence, and insolently made the audience’s own discomfort in watching these earlier scenes into part of the story.

It is also a very English film: the native New Yorker Kubrick had thoroughly mastered an English idiom, though this is perhaps partly due to excellent performances from Warren Clarke and Michael Bates, actors who were to be familiar on British TV. Flawed or not, it is a compelling thought experiment.

- A Clockwork Orange

- Stanley Kubrick

- Malcolm McDowell

- Drama films

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

thisdreamsalive

Saving the world one blog post at a time, book review: a clockwork orange.

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess was released in the 1960s and is not considered a classic and essential read. It may then be surprising that I’ve only read it now, despite it having a place on my reading list for at least four years now.

What A Clockwork Orange Is About

The novel follows protagonist Alex’s fall from grace, reformation, and the aftermath of his “change.” Quite Orwellian in nature, the novel centers on disobedience and governmental control.

Alex and his friends frequely get drunk in milk bars and terrorise their families and their community. Although all his friends are violent, Alex is by far the most malevolent. Alex’s friends leave him as he gets arrested for murder. When the opporunity to get out of jail early if he undergoes a rehabilitation programe presents itself, Alex gets involved thinking he can beat the system. The programe raises questions about if its ethical to fundamentally change a person so radically and free will.

A Clockwork Orange is difficult to get into at first as Alex speaks in “Nadsat” which is teenage slang, that is influenced by Russian. At the start it’s very difficult to get into and understand, but you pick up some of the words as you go on. The language is used in such a way that you understand what is actually happening but the specifics or dialogue isn’t very clear, I’d recommend looking up the Nadsat dictionary and checking chapter summary’s if you struggle.

What I Thought

What I found interesting what that people were adamant that I shouldn’t read The Catcher in the Rye , which is one of my favourite books but A Clockwork Orange was much more violent, and disturbing. In fact, nothing in The Catcher in the Rye disturbed me, I was just mildly irritated by Holden at the end of it.

If death, sexual assault, and violence bother you then this absolutely is not the book for you. I found it difficult to read and Alex was by far the most volatile protagonist I think I’ve ever come across. I haven’t seen the movie, but if it’s true to the novel then I probably won’t watch it.

Although not an easy read, I still think it’s a cautionary tale and calls ethics into play. It came out in the 1960s but is still relevant today. Do we rob people of agency for the greater good? Or live in anarchy?

Honestly it was so disturbing that I didn’t enjoy it, but I made myself finish it. This is a book you should read once, and never again.

Have you read A Clockwork Orange ?

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

0 thoughts on “ Book Review: A Clockwork Orange ”

I’ve never heard of this book but I may have to give it a read. I’ve been trying to find other genres and books that I could give a try so I may just put this on my reading list!

It’s quite disturbing, but it’s always interesting branching into new genres!

I haven’t read the book but I saw the movie and it was frankly nuts. I’m sure the book is even more so. I also couldn’t understand why catcher in the rye was perceived to be a tough read or why it has such an effect on those lacking in empathy. For me it was just a good read. Sorry I’m rambling. Thanks for sharing

I found the book disturbing so I don’t think I’ll watch the movie.

I found “Catcher in The Rye” pretty boring. DNF it about 10% in. May be I was way older than the target reader when I read this classic. “A Clockwork Orange” has been on my TBR list for a decade. But I’m a chicken when it comes to violence/rape scenes.

Your review is nicely written. Glad that- in this YA fantasy frenzy, there are some of us who still read classics.

I was 17 when I first read The Catcher in the Rye so I probably related to it more then than I would now. Thank you

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Screen Rant

A clockwork orange: 10 differences between the book and the film.

Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel is a disturbing masterpiece. How does the movie differ from the original book?

The Stanley Kubrick adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel is often considered one of the most graphically violent, needlessly brutal and incredibly over-the-top films of all time. It depicts everything from intentionally unnecessary violence to rape and torture.

RELATED: The 10 Most Controversial Films Of All Time, Ranked

There are a lot of similarities in that regard between the film and the book that inspired it. However, there are a few major differences that all the two works to keep a bit of contrast. We’ve collected ten of those.

10 Year Old Girls

The first, and arguably most alarming, thing that exists in the book that was taken away for the film is the ages of the Droog’s victims. When Billyboy’s gang commits a rape early on in the film, she is a young woman; in the book, she is just ten years old.

Similarly, the two teenagers we see Alex talking to in the record shop and taking home are also just ten years old in the book. Now, in the film, this seems to be a consensual situation (though they do still appear to be underage), but in the book, this is just another horrific rape. The director likely thought this was too far, even for this film.

Pete’s Demise

Alex’s Droogs Dim, Georgie and Pete are all pretty stupid. They basically enjoy inflicting pain, fear and suffering and not a lot else. They aren’t exactly likable characters that we want to see succeed in life. The books provide a very small bit of justice when we find out that Georgie died in a failed robbery.

RELATED: The 10 Most Surprising Sex Scenes in Film

However, Georgie doesn’t die at all in the film. When Alex is released from prison, it is Pete who seems to be missing from the gang, even though his lack of presence is never referenced.

Alex’s Recognition

A major twist in the plot of A Clockwork Orange comes after Alex’s rehabilitation. He ends up back at the house of a man called F. Alexander, who was the recipient of a violent attack from Alex and his Droogs.

At first, he doesn’t recognize Alex at all, but in the film, he gives himself away by singing ‘Singing In The Rain’. This was the song he sang during the attack. In the books, he simply makes various references to the previous attack by accident, leading to Alexander realizing who he was.

Beethoven’s 9 th

Not being able to list to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony would be quite the punishment for anybody. Taking such powerful music and turning it into a source of anguish is a clever punishment, but it is just about as cruel as Alex himself.

RELATED: 10 '70s Sci-Fi Movies That Are Still Mind-Blowing Today

However, rather than making Alex averse only to Beethoven’s Ninth, the book sees his turned off of all music altogether. Even crueler! Obviously, Kubrick had to diverge from that slightly, because Alex needed to sing ‘Singing In The Rain’ in the film version.

F. Alexander’s Life

Speaking of F. Alexander and the events that took place in his house, his life in the books took a much less drastic turn after Alex’s Droogs attacked him. He may well be scarred after that fateful day, but by the time Alex arrives at his door, he is at least able to walk and take care of himself.

In the film, the added visual spectacle of what Alex did to him is even more powerful. He is forced to move around in a wheelchair and has had to employ an assistant in order to carry out basic tasks. This just shows the lasting impact that one day of ‘ultra-violence’ for Alex had on the life of his victim forever.

The Robbery

Towards the start of Kubrick’s film, we see a lot of examples of the sort of violent actions Alex and the Droogs get up to from rape to senseless, unmotivated violence. What we don’t see, however, is robbery.

RELATED: 10 Beloved Movies That Roger Ebert Hated

The film seems to avoid this concept (remember Georgie’s robbery-based death being cut?), perhaps not thinking it was violent enough for the gang? The book depicts the robbery of a shop at one point, and then use an old lady as an alibi to pretend that they’d simply been in a café the whole time.

The Origins Of The Title

The title of A Clockwork Orange is very strange, and without any explanation, seems to make no sense. There are no oranges, and no clockwork, as far as we can tell. The interpretation that seems to be rather popular is that those carrying out this ultra-violence have an orange for a brain, which is being operated by clockwork, and thus they have no real control over it.

This is supported by the explanation we actually do get in the book: F. Alexander is writing an essay that effectively explains how someone who can’t make their own choices (but still has a conscience) isn’t really alive anymore.

Alex’s Life In Prison

Even though it makes up the entire second act of the film, we don’t see a lot of Alex’s actual life in prison. There are other inmates shown briefly, but we don’t learn names or see a great deal of interaction with them.

RELATED: 10 Most Disturbing Stanley Kubrick Scenes, Ranked

In the books, however, Alex commits another murder while in prison. There is a man who the inmates don’t like and are attacking, with Alex coming in to finish off the job. Rather than each taking responsibility for their part, the other inmates all pin the murder on Alex.

The Droog’s Look

One of the most iconic shots from A Clockwork Orange shows the camera slowly zooming towards the Droogs, who are each sipping milk in the milk bar, dressed in their haunting white attire.

In the book, this image isn’t quite as powerful, with the creepy all-white being replaced with a much more stereotypical black outfit.

Arguably the greatest difference between the book and film is the entire ending. After Alex goes back on his conditioning, the film ends straight away. We leave thinking that Alex isn’t cured, but have no idea what happens to him afterward.

In the book, there is an epilogue that explains how Alex actually is cured. As he ages, his desire for violence begins to wane, and he even suggests that he may start a family one day.

NEXT: The 10 Most Memorable Stanley Kubrick Characters, Ranked

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, a clockwork orange.

Now streaming on:

Stanley Kubrick 's "A Clockwork Orange" is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading As an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex.

I don't know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom Kubrick likes very much, as his visual style reveals and as we shall see in a moment). Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we've all run across a few times in our lives -- usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies. He must have been the kind of kid who tore off the wings of flies and ate ants just because that was so disgusting. He was the kid who always seemed to know more about sex than anyone else, too -- and especially about how dirty it was.

Alex has grown up in "A Clockwork Orange," and now he's a sadistic rapist. I realize that calling him a sadistic rapist -- just like that -- is to stereotype poor Alex a little. But Kubrick doesn't give us much more to go on, except that Alex likes Beethoven a lot. Why he likes Beethoven is never explained, but my notion is that Alex likes Beethoven in the same way that Kubrick likes to load his sound track with familiar classical music -- to add a cute, cheap, dead-end dimension.

Now Alex isn't the kind of sat-upon, working-class anti-hero we got in the angry British movies of the early 1960s. No effort is made to explain his inner workings or take apart his society. Indeed, there's not much to take apart; both Alex and his society are smart-nose pop-art abstractions. Kubrick hasn't created a future world in his imagination -- he's created a trendy decor. If we fall for the Kubrick line and say Alex is violent because "society offers him no alternative," weep, sob, we're just making excuses.

Alex is violent because it is necessary for him to be violent in order for this movie to entertain in the way Kubrick intends. Alex has been made into a sadistic rapist not by society, not by his parents, not by the police state, not by centralization and not by creeping fascism -- but by the producer, director and writer of this film, Stanley Kubrick. Directors sometimes get sanctimonious and talk about their creations in the third person, as if society had really created Alex. But this makes their direction into a sort of cinematic automatic writing. No, I think Kubrick is being too modest: Alex is all his.

I say that in full awareness that "A Clockwork Orange" is based, somewhat faithfully, on a novel by Anthony Burgess . Yet I don't pin the rap on Burgess. Kubrick has used visuals to alter the book's point of view and to nudge us toward a kind of grudging pal-ship with Alex.

Kubrick's most obvious photographic device this time is the wide-angle lens. Used on objects that are fairly close to the camera, this lens tends to distort the sides of the image. The objects in the center of the screen look normal, but those on the edges tend to slant upward and outward, becoming bizarrely elongated. Kubrick uses the wide-angle lens almost all the time when he is showing events from Alex's point of view; this encourages us to see the world as Alex does, as a crazy-house of weird people out to get him.

When Kubrick shows us Alex, however, he either places him in the center of a wide-angle shot (so Alex alone has normal human dimensions,) or uses a standard lens that does not distort. So a visual impression is built up during the movie that Alex, and only Alex, is normal.

Kubrick has another couple of neat gimmicks to build Alex into a hero instead of a wretch. He likes to shoot Alex from above, letting Alex look up at us from under a lowered brow. This was also a favorite Kubrick angle in the close-ups in " 2001: A Space Odyssey ," and in both pictures, Kubrick puts the lighting emphasis on the eyes. This gives his characters a slightly scary, messianic look.

And then Kubrick makes all sorts of references at the end of "A Clockwork Orange" to the famous bedroom (and bathroom) scenes at the end of "2001." The echoing water-drips while Alex takes his bath remind us indirectly of the sound effects in the "2001" bedroom, and then Alex sits down to a table and a glass of wine. He is photographed from the same angle Kubrick used in "2001" to show us Keir Dullea at dinner. And then there's even a shot from behind, showing Alex turning around as he swallows a mouthful of wine.

This isn't just simple visual quotation, I think. Kubrick used the final shots of "2001" to ease his space voyager into the Space Child who ends the movie. The child, you'll remember, turns large and fearsomely wise eyes upon us, and is our savior. In somewhat the same way, Alex turns into a wide eyed child at the end of "A Clockwork Orange," and smiles mischievously as he has a fantasy of rape. We're now supposed to cheer because he's been cured of the anti-rape, anti-violence programming forced upon him by society during a prison "rehabilitation" process.

What in hell is Kubrick up to here? Does he really want us to identify with the antisocial tilt of Alex's psychopathic little life? In a world where society is criminal, of course, a good man must live outside the law. But that isn't what Kubrick is saying, He actually seems to be implying something simpler and more frightening: that in a world where society is criminal, the citizen might as well be a criminal, too.

Well, enough philosophy. We'll probably be debating "A Clockwork Orange" for a long time -- a long, weary and pointless time. The New York critical establishment has guaranteed that for us. They missed the boat on "2001," so maybe they were trying to catch up with Kubrick on this one. Or maybe the news weeklies just needed a good movie cover story for Christmas.

I don't know. But they've really hyped "A Clockwork Orange" for more than it's worth, and a lot of people will go if only out of curiosity. Too bad. In addition to the things I've mentioned above -- things I really got mad about -- "A Clockwork Orange" commits another, perhaps even more unforgivable, artistic sin. It is just plain talky and boring. You know there's something wrong with a movie when the last third feels like the last half.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

Brian Tallerico

About Dry Grasses

Carlos aguilar.

Outlaw Posse

Peter sobczynski.

Glenn Kenny

Bring Him to Me

On the Adamant

Film credits.

A Clockwork Orange (1972)

136 minutes

Michael Gover as Prison Governor

Michael Bates as Chief Guard

Malcolm McDowell as Alex

Miriam Karlin as Catlady

Patrick Magee as Mr. Alexander

Anthony Sharp as Minister

Madge Ryan as Mum

Philip Stone as Dad

Photographed by

- John Alcott

Based on the novel by

- Anthony Burgess

- Walter Carlos

Produced, directed and written by

- Stanley Kubrick

Latest blog posts

Beyoncé and My Daughter Love Country Music

A Poet of an Actor: Louis Gossett, Jr. (1936-2024)

Why I Love Ebertfest: A Movie Lover's Dream

Adam Wingard Focuses on the Monsters

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Kingsley Amis' 1962 Review of A Clockwork Orange

The english comic novelist called anthony burgess' infamous dystopian satire "a fine farrago of outrageousness".

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Is it better for a man to have chosen evil than to have good imposed upon him?

“I acclaim Anthony Burgess’s new novel as the curiosity of the day. A Clockwork Orange is told in the first person. That is the extent of its resemblance to anything much else, though a hasty attempt at orientation might suggest Colin MacInnes and the prole parts of Nineteen Eighty-Four as distant reference points.

Fifteen-year-old Alex pursues a zealously delinquent career through the last decade of the present century, robbing, punching, kicking, slashing, raping, murdering, going to jail etc. He finds plenty of time to talk to the reader at the top of his voice in his era’s hip patois, an amalgam of Russian (the political implications of this are not explored), gypsy jargon, rhyming slang and a touch of schoolboy’s facetious-biblical.

All this is done so thoroughly—there are getting on for 20 neologisms on the first page—that the less adventurous reader, especially if he may happen to be giving up smoking, will be tempted to let the book drop. That would be a pity, because soon you pick up the language and begin to see, as the action develops, that this speech not only gives the book its curious flavour, but also fits in with its prevailing mood.

This is a sort of cheerful horror which many British readers, adventurous or not, will not be up to stomaching. Even I, all-tolerant as I am, found the double child-rape scene a little uninviting, especially since it takes place to the accompaniment of Beethoven’s Ninth , choral section. What price the notion that buying classical LPs is our youth’s route to salvation, eh?

But there’s no harm in it really. Mr Burgess has written a fine farrago of outrageousness, one which incidentally suggests a view of juvenile violence I can’t remember having met before: that its greatest appeal is that it’s a big laugh, in which what we ordinarily think of as sadism plays little part.

There’s a science-fiction interest here too, to do with a machine that makes you good. We get to this rather late on, as is common when a writer of ordinary fiction has a go at such things, but it’s disagreeably plausible when it comes. If you don’t take to it all, then I can’t resist calling you a starry ptitsa who can’t viddy a horrorshow veshch when it’s in front of your glazzies. And yarbles to you.”

–Kingsley Amis, The Observer , May 13, 1962

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

April 1, 2024

- Jhumpa Lahiri shares the syllabus for her recent course

- Thoughts on Trump’s new gig as a Bible salesman

- The life and work of Raymond Williams

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Users share their opinions on whether the book is worth reading after seeing the film. They praise the book's language, atmosphere, and ending, but warn about the difficulty and darkness of the story.

A user asks if A Clockwork Orange is overrated and wonders what to gain from the book besides enjoyment. See the comments and other posts related to books, reading, and literature on r/books subreddit.

4.00. 710,828 ratings20,661 reviews. In Anthony Burgess's influential nightmare vision of the future, criminals take over after dark. Teen gang leader Alex narrates in fantastically inventive slang that echoes the violent intensity of youth rebelling against society. Dazzling and transgressive, A Clockwork Orange is a frightening fable about ...

A Clockwork Orange is one of those books that I have been told is an 'essential' read for any teenager - and after reading it myself, I found that I completely agree with the general consensus ...

3.4. A Clockwork Orange Review. A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess' best-known novel. It follows Alex, a violent and seemingly irredeemable protagonist who is subjected to a brainwashing experiment at the hands of the State. No longer able to think violent thoughts, he serves as a lesson of the importance of free will.

My rating: 5 of 5 stars. Amazon page. While it's a title that probably has had many readers scratching their heads, "A Clockwork Orange" is the perfect title for Burgess's book. Our brains—while highly capable—are a stringy, wet mess of complexity, and to treat them like a clockwork machine is to invite trouble as well as to muddle ...

Well you can't get more classic than A Clockwork Orange. I continuously watched the movie when I was a teenager; safe to say I had a sick curiosity about witnessing a character that was so purely evil such as Alex. After some research, I learnt that the meaning of the term 'a clockwork orange' is to describe something as solely one thing - for example, solely good or solely evil. This book ...

Martin Amis is the author, most recently, of "Lionel Asbo: State of England.". This essay is adapted from his introduction to a new 50th-anniversary edition of "A Clockwork Orange ...

Yes. A Clockwork Orange comes under the heading of "books you feel you ought to have read by now". Mostly these are books that you don't necessarily want to read, but are considered such classics that an inability to pass any kind of comment upon them suggests a gaping hole in your education. Like most people I had heard of "Clockwork Orange ...

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE. The previous books of this author ( Devil of a State, 1962; The Right to an Answer, 1961) had valid points of satire, some humor, and a contemporary view, but here the picture is all out—from a time in the future to an argot that makes such demands on the reader that no one could care less after the first two pages.

Set in a terrifying dystopian future, A Clockwork Orange is a disturbing exploration of morality and free will. Rating: ★★★½. I enjoyed A Clockwork Orange much more than I thought I would after briefly scanning it and reading all of the strange language. I read this novel in preparation for seeing a performance of it, so I was determined ...

It is strange to watch A Clockwork Orange again, in my case for the first time in 20 years. It is still brilliant, still audacious, still nasty, but definitely dated, and longer than I remembered.

What novel was the basis for a popular Apple ad directed by Ridley Scott? A Clockwork Orange Brave New World The Great Gatsby Nineteen Eighty-Four

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess was released in the 1960s and is not considered a classic and essential read. It may then be surprising that I've only read it now, despite it having a place on my reading list for at least four years now. What A Clockwork Orange Is About

A concise book review of Anthony Burgess's classic novel, A Clockwork Orange. Let's have some ultraviolence! (tw // rape, violence)🐲Expand Me 🐲Buy A Clockw...

Arguably the greatest difference between the book and film is the entire ending. After Alex goes back on his conditioning, the film ends straight away. We leave thinking that Alex isn't cured, but have no idea what happens to him afterward. In the book, there is an epilogue that explains how Alex actually is cured.

A Clockwork Orange. Stanley Kubrick 's "A Clockwork Orange" is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading As an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex. I don't know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom ...

Behind the scenes of "A Clockwork Orange" (1971) with Malcolm McDowell, Stanley Kubrick, and a few members of the filming crew. ... That's an epic scene in cinema history. That book and movie is as relevant today as it was then. Reply reply Rank by size . More posts you may like Related discussions Best Stanley Kubrick Movies ...

Fifteen-year-old Alex pursues a zealously delinquent career through the last decade of the present century, robbing, punching, kicking, slashing, raping, murdering, going to jail etc. He finds plenty of time to talk to the reader at the top of his voice in his era's hip patois, an amalgam of Russian (the political implications of this are not ...