Daria Gritsenko, PhD

Thinking with concepts, top social science questions.

Social science is the scholarly study of human society and social relationships. It is a tremendously important branch of research that examines what it means to be a social being, how individuals function together as organized groups and societies, and how they interact with each other on issues of common interest. Yet, this remains very broad to provide proper guidance to an early career researcher, as myself. In particular, a researcher en route to social impact. In order to be socially relevant, social research has to be problem-driven. I think, the most pressing problems of today are

(1) sustainability transition , incl. natural resource governance, climate change, and decoupling of well-being from consumption;

(2) intercultural conflicts , religious controversies, new sources of violence, and pathways to democracy, tolerance, equality, and peace;

(3) unbridled reliance on technology of digitalisation and automation/AI leading to individual deskilling, societal depoliticisation, new political economy of tech giants, and loss of social competences.

Yet, it does not mean that we can tackle these issues straight away. Indeed, over a century of institutionalized social research already provided us with some important insights, but as our environment changes, so do the answers.

Having asked myself this question – What are the most important questions in social science today? – I decided to search for what is being considered by the scholarly community as the most pressing questions that social scientists should tackle today, the unresolved issues that young scholars should work upon. And I found a few. I think that paying attention to the most urgent social science problems will equip us with tools to address these problems. We are free in choosing our cases, methods of analysis, and testing different theories, yet, we are indebted to the society (and tax-payers) to act at the edge of human knowledge and to be socially relevant keeping in mind the BIG picture.

Top ten social science questions

( Nature 470 , 18-19 (2011) doi:10.1038/470018a):

1. How can we induce people to look after their health?

2. How do societies create effective and resilient institutions, such as governments?

3. How can humanity increase its collective wisdom?

4. How do we reduce the ‘skill gap’ between black and white people in America?

5. How can we aggregate information possessed by individuals to make the best decisions?

6. How can we understand the human capacity to create and articulate knowledge?

7. Why do so many female workers still earn less than male workers?

8. How and why does the ‘social’ become ‘biological’?

9. How can we be robust against ‘black swans’ — rare events that have extreme consequences?

10. Why do social processes, in particular civil violence, either persist over time or suddenly change?

During the symposium in Harvard that led to formulation of these problems, a few other concrete puzzles received a lot of attention, too (details from Nature) :

11. How physiological and psychological attributes, such as obesity and loneliness, can spread through a social network like a contagious disease?

12. How to explain “small outbursts of creativity and achievement”: such Renaissance Florence, the Scottish Enlightenment, Silicon Valley?

13. What are the sources of social inequality and how does it relate to political institutions and social structures?

14. We’re better at biology than behavior. Some of the social problems are ‘solved’ from the technical point of view. How to foster behavioral change?

15. What is the causal effect of culture on human behavior and how can better models of what culture is and how it works be developed?

Here also 1 0 reasons why we need social sciences .

One thought on “ Top social science questions ”

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular post! It’s the little changes that produce the most significant changes. Thanks for sharing!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

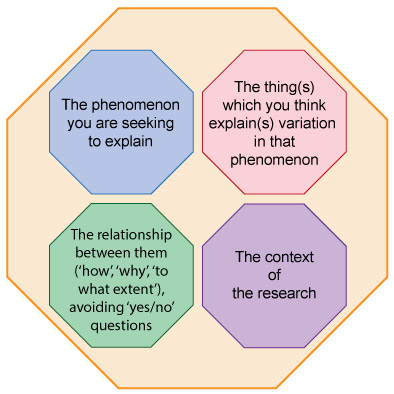

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE : A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

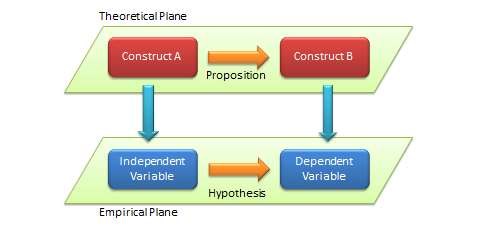

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

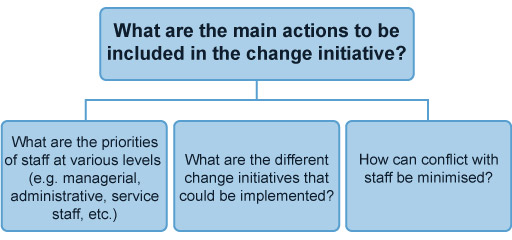

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Apr 22, 2024 9:12 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

9 9. Writing your research question

Chapter outline.

- Empirical vs. ethical questions (4 minute read)

- Characteristics of a good research question (4 minute read)

- Quantitative research questions (7 minute read)

- Qualitative research questions (3 minute read)

- Evaluating and updating your research questions (4 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter include references to sexual violence, sexism, substance use disorders, homelessness, domestic violence, the child welfare system, cissexism and heterosexism, and truancy and school discipline.

9.1 Empirical vs. ethical questions

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Define empirical questions and provide an example

- Define ethical questions and provide an example

Writing a good research question is an art and a science. It is a science because you have to make sure it is clear, concise, and well-developed. It is an art because often your language needs “wordsmithing” to perfect and clarify the meaning. This is an exciting part of the research process; however, it can also be one of the most stressful.

Creating a good research question begins by identifying a topic you are interested in studying. At this point, you already have a working question. You’ve been applying it to the exercises in each chapter, and after reading more about your topic in the scholarly literature, you’ve probably gone back and revised your working question a few times. We’re going to continue that process in more detail in this chapter. Keep in mind that writing research questions is an iterative process, with revisions happening week after week until you are ready to start your project.

Empirical vs. ethical questions

When it comes to research questions, social science is best equipped to answer empirical questions —those that can be answered by real experience in the real world—as opposed to ethical questions —questions about which people have moral opinions and that may not be answerable in reference to the real world. While social workers have explicit ethical obligations (e.g., service, social justice), research projects ask empirical questions to help actualize and support the work of upholding those ethical principles.

In order to help you better understand the difference between ethical and empirical questions, let’s consider a topic about which people have moral opinions. How about SpongeBob SquarePants? [1] In early 2005, members of the conservative Christian group Focus on the Family (2005) [2] denounced this seemingly innocuous cartoon character as “morally offensive” because they perceived his character to be one that promotes a “pro-gay agenda.” Focus on the Family supported their claim that SpongeBob is immoral by citing his appearance in a children’s video designed to promote tolerance of all family forms (BBC News, 2005). [3] They also cited SpongeBob’s regular hand-holding with his male sidekick Patrick as further evidence of his immorality.

So, can we now conclude that SpongeBob SquarePants is immoral? Not so fast. While your mother or a newspaper or television reporter may provide an answer, a social science researcher cannot. Questions of morality are ethical, not empirical. Of course, this doesn’t mean that social science researchers cannot study opinions about or social meanings surrounding SpongeBob SquarePants (Carter, 2010). [4] We study humans after all, and as you will discover in the following chapters of this textbook, we are trained to utilize a variety of scientific data-collection techniques to understand patterns of human beliefs and behaviors. Using these techniques, we could find out how many people in the United States find SpongeBob morally reprehensible, but we could never learn, empirically, whether SpongeBob is in fact morally reprehensible.

Let’s consider an example from a recent MSW research class I taught. A student group wanted to research the penalties for sexual assault. Their original research question was: “How can prison sentences for sexual assault be so much lower than the penalty for drug possession?” Outside of the research context, that is a darn good question! It speaks to how the War on Drugs and the patriarchy have distorted the criminal justice system towards policing of drug crimes over gender-based violence.

Unfortunately, it is an ethical question, not an empirical one. To answer that question, you would have to draw on philosophy and morality, answering what it is about human nature and society that allows such unjust outcomes. However, you could not answer that question by gathering data about people in the real world. If I asked people that question, they would likely give me their opinions about drugs, gender-based violence, and the criminal justice system. But I wouldn’t get the real answer about why our society tolerates such an imbalance in punishment.

As the students worked on the project through the semester, they continued to focus on the topic of sexual assault in the criminal justice system. Their research question became more empirical because they read more empirical articles about their topic. One option that they considered was to evaluate intervention programs for perpetrators of sexual assault to see if they reduced the likelihood of committing sexual assault again. Another option they considered was seeing if counties or states with higher than average jail sentences for sexual assault perpetrators had lower rates of re-offense for sexual assault. These projects addressed the ethical question of punishing perpetrators of sexual violence but did so in a way that gathered and analyzed empirical real-world data. Our job as social work researchers is to gather social facts about social work issues, not to judge or determine morality.

Key Takeaways

- Empirical questions are distinct from ethical questions.

- There are usually a number of ethical questions and a number of empirical questions that could be asked about any single topic.

- While social workers may research topics about which people have moral opinions, a researcher’s job is to gather and analyze empirical data.

- Take a look at your working question. Make sure you have an empirical question, not an ethical one. To perform this check, describe how you could find an answer to your question by conducting a study, like a survey or focus group, with real people.

9.2 Characteristics of a good research question

- Identify and explain the key features of a good research question

- Explain why it is important for social workers to be focused and clear with the language they use in their research questions

Now that you’ve made sure your working question is empirical, you need to revise that working question into a formal research question. So, what makes a good research question? First, it is generally written in the form of a question. To say that your research question is “the opioid epidemic” or “animal assisted therapy” or “oppression” would not be correct. You need to frame your topic as a question, not a statement. A good research question is also one that is well-focused. A well-focused question helps you tune out irrelevant information and not try to answer everything about the world all at once. You could be the most eloquent writer in your class, or even in the world, but if the research question about which you are writing is unclear, your work will ultimately lack direction.

In addition to being written in the form of a question and being well-focused, a good research question is one that cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. For example, if your interest is in gender norms, you could ask, “Does gender affect a person’s performance of household tasks?” but you will have nothing left to say once you discover your yes or no answer. Instead, why not ask, about the relationship between gender and household tasks. Alternatively, maybe we are interested in how or to what extent gender affects a person’s contributions to housework in a marriage? By tweaking your question in this small way, you suddenly have a much more fascinating question and more to say as you attempt to answer it.

A good research question should also have more than one plausible answer. In the example above, the student who studied the relationship between gender and household tasks had a specific interest in the impact of gender, but she also knew that preferences might be impacted by other factors. For example, she knew from her own experience that her more traditional and socially conservative friends were more likely to see household tasks as part of the female domain, and were less likely to expect their male partners to contribute to those tasks. Thinking through the possible relationships between gender, culture, and household tasks led that student to realize that there were many plausible answers to her questions about how gender affects a person’s contribution to household tasks. Because gender doesn’t exist in a vacuum, she wisely felt that she needed to consider other characteristics that work together with gender to shape people’s behaviors, likes, and dislikes. By doing this, the student considered the third feature of a good research question–she thought about relationships between several concepts. While she began with an interest in a single concept—household tasks—by asking herself what other concepts (such as gender or political orientation) might be related to her original interest, she was able to form a question that considered the relationships among those concepts.

This student had one final component to consider. Social work research questions must contain a target population. Her study would be very different if she were to conduct it on older adults or immigrants who just arrived in a new country. The target population is the group of people whose needs your study addresses. Maybe the student noticed issues with household tasks as part of her social work practice with first-generation immigrants, and so she made it her target population. Maybe she wants to address the needs of another community. Whatever the case, the target population should be chosen while keeping in mind social work’s responsibility to work on behalf of marginalized and oppressed groups.

In sum, a good research question generally has the following features:

- It is written in the form of a question

- It is clearly written

- It cannot be answered with “yes” or “no”

- It has more than one plausible answer

- It considers relationships among multiple variables

- It is specific and clear about the concepts it addresses

- It includes a target population

- A poorly focused research question can lead to the demise of an otherwise well-executed study.

- Research questions should be clearly worded, consider relationships between multiple variables, have more than one plausible answer, and address the needs of a target population.

Okay, it’s time to write out your first draft of a research question.

- Once you’ve done so, take a look at the checklist in this chapter and see if your research question meets the criteria to be a good one.

Brainstorm whether your research question might be better suited to quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Describe why your question fits better with quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Provide an alternative research question that fits with the other type of research method.

9.3 Quantitative research questions

- Describe how research questions for exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory quantitative questions differ and how to phrase them

- Identify the differences between and provide examples of strong and weak explanatory research questions

Quantitative descriptive questions

The type of research you are conducting will impact the research question that you ask. Probably the easiest questions to think of are quantitative descriptive questions. For example, “What is the average student debt load of MSW students?” is a descriptive question—and an important one. We aren’t trying to build a causal relationship here. We’re simply trying to describe how much debt MSW students carry. Quantitative descriptive questions like this one are helpful in social work practice as part of community scans, in which human service agencies survey the various needs of the community they serve. If the scan reveals that the community requires more services related to housing, child care, or day treatment for people with disabilities, a nonprofit office can use the community scan to create new programs that meet a defined community need.

Quantitative descriptive questions will often ask for percentage, count the number of instances of a phenomenon, or determine an average. Descriptive questions may only include one variable, such as ours about student debt load, or they may include multiple variables. Because these are descriptive questions, our purpose is not to investigate causal relationships between variables. To do that, we need to use a quantitative explanatory question.

Quantitative explanatory questions

Most studies you read in the academic literature will be quantitative and explanatory. Why is that? If you recall from Chapter 2 , explanatory research tries to build nomothetic causal relationships. They are generalizable across space and time, so they are applicable to a wide audience. The editorial board of a journal wants to make sure their content will be useful to as many people as possible, so it’s not surprising that quantitative research dominates the academic literature.

Structurally, quantitative explanatory questions must contain an independent variable and dependent variable. Questions should ask about the relationship between these variables. The standard format I was taught in graduate school for an explanatory quantitative research question is: “What is the relationship between [independent variable] and [dependent variable] for [target population]?” You should play with the wording for your research question, revising that standard format to match what you really want to know about your topic.

Let’s take a look at a few more examples of possible research questions and consider the relative strengths and weaknesses of each. Table 9.1 does just that. While reading the table, keep in mind that I have only noted what I view to be the most relevant strengths and weaknesses of each question. Certainly each question may have additional strengths and weaknesses not noted in the table. Each of these questions is drawn from student projects in my research methods classes and reflects the work of many students on their research question over many weeks.

Making it more specific

A good research question should also be specific and clear about the concepts it addresses. A student investigating gender and household tasks knows what they mean by “household tasks.” You likely also have an impression of what “household tasks” means. But are your definition and the student’s definition the same? A participant in their study may think that managing finances and performing home maintenance are household tasks, but the researcher may be interested in other tasks like childcare or cleaning. The only way to ensure your study stays focused and clear is to be specific about what you mean by a concept. The student in our example could pick a specific household task that was interesting to them or that the literature indicated was important—for example, childcare. Or, the student could have a broader view of household tasks, one that encompasses childcare, food preparation, financial management, home repair, and care for relatives. Any option is probably okay, as long as the researcher is clear on what they mean by “household tasks.” Clarifying these distinctions is important as we look ahead to specifying how your variables will be measured in Chapter 11 .

Table 9.2 contains some “watch words” that indicate you may need to be more specific about the concepts in your research question.

It can be challenging to be this specific in social work research, particularly when you are just starting out your project and still reading the literature. If you’ve only read one or two articles on your topic, it can be hard to know what you are interested in studying. Broad questions like “What are the causes of chronic homelessness, and what can be done to prevent it?” are common at the beginning stages of a research project as working questions. However, moving from working questions to research questions in your research proposal requires that you examine the literature on the topic and refine your question over time to be more specific and clear. Perhaps you want to study the effect of a specific anti-homelessness program that you found in the literature. Maybe there is a particular model to fighting homelessness, like Housing First or transitional housing, that you want to investigate further. You may want to focus on a potential cause of homelessness such as LGBTQ+ discrimination that you find interesting or relevant to your practice. As you can see, the possibilities for making your question more specific are almost infinite.

Quantitative exploratory questions

In exploratory research, the researcher doesn’t quite know the lay of the land yet. If someone is proposing to conduct an exploratory quantitative project, the watch words highlighted in Table 9.2 are not problematic at all. In fact, questions such as “What factors influence the removal of children in child welfare cases?” are good because they will explore a variety of factors or causes. In this question, the independent variable is less clearly written, but the dependent variable, family preservation outcomes, is quite clearly written. The inverse can also be true. If we were to ask, “What outcomes are associated with family preservation services in child welfare?”, we would have a clear independent variable, family preservation services, but an unclear dependent variable, outcomes. Because we are only conducting exploratory research on a topic, we may not have an idea of what concepts may comprise our “outcomes” or “factors.” Only after interacting with our participants will we be able to understand which concepts are important.

Remember that exploratory research is appropriate only when the researcher does not know much about topic because there is very little scholarly research. In our examples above, there is extensive literature on the outcomes in family reunification programs and risk factors for child removal in child welfare. Make sure you’ve done a thorough literature review to ensure there is little relevant research to guide you towards a more explanatory question.

- Descriptive quantitative research questions are helpful for community scans but cannot investigate causal relationships between variables.

- Explanatory quantitative research questions must include an independent and dependent variable.

- Exploratory quantitative research questions should only be considered when there is very little previous research on your topic.

- Identify the type of research you are engaged in (descriptive, explanatory, or exploratory).

- Create a quantitative research question for your project that matches with the type of research you are engaged in.

Preferably, you should be creating an explanatory research question for quantitative research.

9.4 Qualitative research questions

- List the key terms associated with qualitative research questions

- Distinguish between qualitative and quantitative research questions

Qualitative research questions differ from quantitative research questions. Because qualitative research questions seek to explore or describe phenomena, not provide a neat nomothetic explanation, they are often more general and openly worded. They may include only one concept, though many include more than one. Instead of asking how one variable causes changes in another, we are instead trying to understand the experiences , understandings , and meanings that people have about the concepts in our research question. These keywords often make an appearance in qualitative research questions.

Let’s work through an example from our last section. In Table 9.1, a student asked, “What is the relationship between sexual orientation or gender identity and homelessness for late adolescents in foster care?” In this question, it is pretty clear that the student believes that adolescents in foster care who identify as LGBTQ+ may be at greater risk for homelessness. This is a nomothetic causal relationship—LGBTQ+ status causes changes in homelessness.

However, what if the student were less interested in predicting homelessness based on LGBTQ+ status and more interested in understanding the stories of foster care youth who identify as LGBTQ+ and may be at risk for homelessness? In that case, the researcher would be building an idiographic causal explanation . The youths whom the researcher interviews may share stories of how their foster families, caseworkers, and others treated them. They may share stories about how they thought of their own sexuality or gender identity and how it changed over time. They may have different ideas about what it means to transition out of foster care.

Because qualitative questions usually center on idiographic causal relationships, they look different than quantitative questions. Table 9.3 below takes the final research questions from Table 9.1 and adapts them for qualitative research. The guidelines for research questions previously described in this chapter still apply, but there are some new elements to qualitative research questions that are not present in quantitative questions.

- Qualitative research questions often ask about lived experience, personal experience, understanding, meaning, and stories.

- Qualitative research questions may be more general and less specific.

- Qualitative research questions may also contain only one variable, rather than asking about relationships between multiple variables.

Qualitative research questions have one final feature that distinguishes them from quantitative research questions: they can change over the course of a study. Qualitative research is a reflexive process, one in which the researcher adapts their approach based on what participants say and do. The researcher must constantly evaluate whether their question is important and relevant to the participants. As the researcher gains information from participants, it is normal for the focus of the inquiry to shift.

For example, a qualitative researcher may want to study how a new truancy rule impacts youth at risk of expulsion. However, after interviewing some of the youth in their community, a researcher might find that the rule is actually irrelevant to their behavior and thoughts. Instead, their participants will direct the discussion to their frustration with the school administrators or the lack of job opportunities in the area. This is a natural part of qualitative research, and it is normal for research questions and hypothesis to evolve based on information gleaned from participants.

However, this reflexivity and openness unacceptable in quantitative research for good reasons. Researchers using quantitative methods are testing a hypothesis, and if they could revise that hypothesis to match what they found, they could never be wrong! Indeed, an important component of open science and reproducability is the preregistration of a researcher’s hypotheses and data analysis plan in a central repository that can be verified and replicated by reviewers and other researchers. This interactive graphic from 538 shows how an unscrupulous research could come up with a hypothesis and theoretical explanation after collecting data by hunting for a combination of factors that results in a statistically significant relationship. This is an excellent example of how the positivist assumptions behind quantitative research and intepretivist assumptions behind qualitative research result in different approaches to social science.

- Qualitative research questions often contain words or phrases like “lived experience,” “personal experience,” “understanding,” “meaning,” and “stories.”

- Qualitative research questions can change and evolve over the course of the study.

- Using the guidance in this chapter, write a qualitative research question. You may want to use some of the keywords mentioned above.

9.5 Evaluating and updating your research questions

- Evaluate the feasibility and importance of your research questions

- Begin to match your research questions to specific designs that determine what the participants in your study will do

Feasibility and importance

As you are getting ready to finalize your research question and move into designing your research study, it is important to check whether your research question is feasible for you to answer and what importance your results will have in the community, among your participants, and in the scientific literature

Key questions to consider when evaluating your question’s feasibility include:

- Do you have access to the data you need?

- Will you be able to get consent from stakeholders, gatekeepers, and others?

- Does your project pose risk to individuals through direct harm, dual relationships, or breaches in confidentiality? (see Chapter 6 for more ethical considerations)

- Are you competent enough to complete the study?

- Do you have the resources and time needed to carry out the project?

Key questions to consider when evaluating the importance of your question include:

- Can we answer your research question simply by looking at the literature on your topic?

- How does your question add something new to the scholarly literature? (raises a new issue, addresses a controversy, studies a new population, etc.)

- How will your target population benefit, once you answer your research question?

- How will the community, social work practice, and the broader social world benefit, once you answer your research question?

- Using the questions above, check whether you think your project is feasible for you to complete, given the constrains that student projects face.

- Realistically, explore the potential impact of your project on the community and in the scientific literature. Make sure your question cannot be answered by simply reading more about your topic.

Matching your research question and study design

This chapter described how to create a good quantitative and qualitative research question. In Parts 3 and 4 of this textbook, we will detail some of the basic designs like surveys and interviews that social scientists use to answer their research questions. But which design should you choose?

As with most things, it all depends on your research question. If your research question involves, for example, testing a new intervention, you will likely want to use an experimental design. On the other hand, if you want to know the lived experience of people in a public housing building, you probably want to use an interview or focus group design.

We will learn more about each one of these designs in the remainder of this textbook. We will also learn about using data that already exists, studying an individual client inside clinical practice, and evaluating programs, which are other examples of designs. Below is a list of designs we will cover in this textbook:

- Surveys: online, phone, mail, in-person

- Experiments: classic, pre-experiments, quasi-experiments

- Interviews: in-person or via phone or videoconference

- Focus groups: in-person or via videoconference

- Content analysis of existing data

- Secondary data analysis of another researcher’s data

- Program evaluation

The design of your research study determines what you and your participants will do. In an experiment, for example, the researcher will introduce a stimulus or treatment to participants and measure their responses. In contrast, a content analysis may not have participants at all, and the researcher may simply read the marketing materials for a corporation or look at a politician’s speeches to conduct the data analysis for the study.

I imagine that a content analysis probably seems easier to accomplish than an experiment. However, as a researcher, you have to choose a research design that makes sense for your question and that is feasible to complete with the resources you have. All research projects require some resources to accomplish. Make sure your design is one you can carry out with the resources (time, money, staff, etc.) that you have.

There are so many different designs that exist in the social science literature that it would be impossible to include them all in this textbook. The purpose of the subsequent chapters is to help you understand the basic designs upon which these more advanced designs are built. As you learn more about research design, you will likely find yourself revising your research question to make sure it fits with the design. At the same time, your research question as it exists now should influence the design you end up choosing. There is no set order in which these should happen. Instead, your research project should be guided by whether you can feasibly carry it out and contribute new and important knowledge to the world.

- Research questions must be feasible and important.

- Research questions must match study design.

- Based on what you know about designs like surveys, experiments, and interviews, describe how you might use one of them to answer your research question.

- You may want to refer back to Chapter 2 which discusses how to get raw data about your topic and the common designs used in student research projects.

- Not familiar with SpongeBob SquarePants? You can learn more about him on Nickelodeon’s site dedicated to all things SpongeBob: http://www.nick.com/spongebob-squarepants/ ↵

- Focus on the Family. (2005, January 26). Focus on SpongeBob. Christianity Today . Retrieved from http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2005/januaryweb-only/34.0c.html ↵

- BBC News. (2005, January 20). US right attacks SpongeBob video. Retrieved from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4190699.stm ↵

- In fact, an MA thesis examines representations of gender and relationships in the cartoon: Carter, A. C. (2010). Constructing gender and relationships in “SpongeBob SquarePants”: Who lives in a pineapple under the sea . MA thesis, Department of Communication, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL. ↵

research questions that can be answered by systematically observing the real world

unsuitable research questions which are not answerable by systematic observation of the real world but instead rely on moral or philosophical opinions

the group of people whose needs your study addresses

attempts to explain or describe your phenomenon exhaustively, based on the subjective understandings of your participants

"Assuming that the null hypothesis is true and the study is repeated an infinite number times by drawing random samples from the same populations(s), less than 5% of these results will be more extreme than the current result" (Cassidy et al., 2019, p. 233).

whether you can practically and ethically complete the research project you propose

the impact your study will have on participants, communities, scientific knowledge, and social justice

Graduate research methods in social work Copyright © 2021 by Matthew DeCarlo, Cory Cummings, Kate Agnelli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

4. Research Questions

4.2. Types of Research Questions

Learning Objectives

- Define empirical and normative questions and provide examples of each.

- Understand the differences between exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory studies and research questions.

As you move from a research topic to a research question, there are some considerations that should guide how you pose your question. First, social scientists are best equipped to answer empirical questions —questions about the facts of the world around us—as opposed to normative or ethical questions—questions about what we as a society should value. Empirical questions can be answered through research, but the answers to normative questions depend on people’s moral opinions. (To say something is “normative” means that it relates to our norms or standards—what we should do.) While research projects can inform how we make decisions about ethical issues, they cannot directly answer normative questions, which are fundamentally a matter of debate within communities and societies about what sorts of principles they want to uphold.

For example, a student in one of our methods classes wanted to research student athletes. Their original research question was: “Should college athletes be paid?” Outside of a research context, this is a great question—the matter of paying or not paying athletes affects the lives of millions of students, and it speaks to critical issues about what we as a society think a college education should entail, and what is a fair reward for the work people do. Unfortunately, this specific question is a normative one that we need to debate, not an empirical question that we can resolve with research. A tip-off here is that it begins with the word “should,” a normative phrasing that you generally want to avoid in research questions. The answer to such a question would be a series of moral arguments, based on the particular values the author and their audience hold in common.

It’s true that research can help us to make moral arguments. For example, if we learn how much money universities make from college sports, or how all the work that athletes put into training and playing shapes their experience of college, that empirical knowledge could help us decide whether we believe student athletes are being exploited by their universities, and whether we believe they have a moral right to be paid for their labor. But then those questions would be our research questions, rather than the normative question of whether athletes “should” be paid.

Let’s consider another ethical question that research can inform but not answer: is SpongeBob SquarePants immoral? In 2012, a Ukrainian government commission began reviewing that cartoon show in response to complaints by a right-wing religious group that its depiction of depraved behaviors—such as SpongeBob’s regular practice of holding his male sidekick Patrick’s hand—amounted to the “promotion of homosexuality” (Marson 2012). (Before the government body was disbanded in 2015, the National Expert Commission of Ukraine on the Protection of Public Morality evaluated media to ensure television shows and other content adhered to the country’s morality laws regarding pornography and other controversial issues.) The agency called a special session to discuss SpongeBob and other suspect kids’ shows, though ultimately the eponymous sponge and his starfish companion stayed on Ukrainian TV. A decade earlier, SpongeBob had also drawn the ire of U.S. conservative groups for appearing with other popular cartoon characters in a music video intended to teach children about multiculturalism—which the advocacy group Focus on the Family said was “pro-homosexual” and served as an “insidious means” of “manipulating and potentially brainwashing kids” (Kirkpatrick 2005).

Can research answer the question of whether SpongeBob SquarePants is immoral? No, because questions of morality are ethical, not empirical. Your family members and pundits on TV can rant about sponge creatures all they want, and they can make better or worse moral arguments for their positions, but this is not a question a social scientist should build a study around. That said, we sociologists could certainly choose to study the public opinions and cultural meanings that surround a popular show like SpongeBob SquarePants . We could conduct experiments measuring the detrimental effects that watching the show has on children’s behavior. We could even use surveys to find out precisely how many people in the United States find SpongeBob and/or Patrick repugnant. But sadly, we could not settle the question of whether SpongeBob is indeed morally reprehensible, given that it is not an empirical question.

As you start designing your study, your choice of a particular empirical question will also be influenced by your study’s general purpose. There are three approaches that a research study will typically take: exploration , description , or explanation . These are not mutually exclusive categories, and a study may fall into multiple categories.

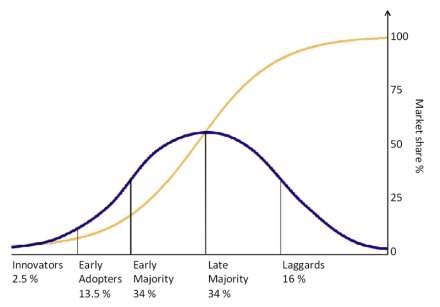

Exploratory research is often conducted in new areas of inquiry, where the goals of the research are: (1) to scope out the magnitude or extent of a particular phenomenon; (2) to generate some initial ideas or hunches about that phenomenon; or (3) to test the feasibility of undertaking a more extensive study. For instance, if the citizens of a country are generally dissatisfied with their government’s policies during an economic recession, sociologists could create and implement new surveys to measure the extent of that dissatisfaction and probe for possible causes of it, such as anxieties about unemployment, inflation, or higher taxes. This research may not lead to a very accurate understanding of the target problem, but it may be worthwhile nonetheless in order to get a preliminary sense of its nature and extent, serving as a stepping stone to more in-depth research.

Descriptive research is directed at making careful observations and detailed documentation of a phenomenon of interest. Because these observations follow the scientific method, they hopefully are more accurate than casual observations by untrained people. Much exploratory research overlaps with descriptive research: we often want to describe the magnitude of an emerging problem as a starting point in understanding it. Yet descriptive research is also helpful to conduct on an ongoing basis, and it can involve well-studied topics.

A common type of descriptive research is the work of government agencies to tabulate statistics about the population. In the United States, for example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics uses survey questions to estimate employment by sector every month. The U.S. Census Bureau regularly conducts demographic surveys that allow policymakers and social scientists to track the growth of a wide range of racial and ethnic groups over many years. In general, government agencies, corporations, nonprofits, and other organizations are in great need of such descriptive research so that they understand the circumstances that their citizens, clients, and members are experiencing. They can use these assessments to create new programs or policies to meet people’s needs or preferences. For that reason, if you decide to use your sociological research skills in a nonacademic setting (as described in Chapter 2: Using Sociology in Everyday Life ), you will likely be doing a lot of descriptive research.

That said, descriptive research is also a large component of many studies that academic sociologists do. For example, a sociologist’s ethnographic study of gang activities among adolescent youth in urban areas might entail detailed observations of the children’s activities. A study of religious practices in immigrant communities might chronicle the evolution of those practices over time. In conducting this descriptive research, sociologists are gathering essential information about what is actually going on in the social spaces they observe.

Explanatory research seeks explanations of observed behaviors, problems, or other phenomena. You might think of the difference between descriptive and explanatory research in this way: while the former seeks answers to basic “what,” “where,” “who,” and “when” types of questions, the latter examines questions that are more complex—whether or not one concept affects another, and “why” and “how” those concepts are related. Put another way, explanatory research attempts to “connect the dots” in research, by identifying certain important factors and showing how they lead to specific outcomes. Let’s consider the hypothetical studies we discussed at the end of the last paragraph in this light. For an explanatory study about urban gangs, sociologists might seek to understand the reasons that adolescent youth in urban areas get involved with gangs. For an explanatory study of immigrant religious practices, researchers might examine why these practices evolve in the ways they do within particular local or national contexts.

Most studies you read in the academic literature will be explanatory. Why is that? Explanatory research tries to identify causal relationships that are generalizable across space and time. That means the findings of such research should matter to many people: because we’re learning something fundamental about the relationships between the concepts we’re interested in, our conclusions aren’t limited to a one-off situation or scenario. It also means our findings are actionable: because we know what causes what, we can act individually or collectively to promote, discourage, or alter the phenomenon we’re studying. In other words, explanatory research gives us a better sense of how and why society operates the way it does, rather than just describing what particular aspects of society look like.

Arriving at compelling explanations for social phenomena requires especially strong theoretical and empirical skills. You need to have a sophisticated understanding of how a social process operates and rule out any alternative stories, and you need to collect empirically sound data and rigorously analyze it. For these reasons, sociologists often see explanatory research as a “higher” form of research, one that is exceedingly challenging to do well. At the same time, they will frequently engage in some amount of exploratory and descriptive research for any given study, particularly during its initial phases. Indeed, these other approaches can be especially important in helping us understand a relatively new or hard-to-study phenomenon: without good descriptive research to draw from, any theorizing we do will be built on shaky empirical foundations.

Deciding on the primary purpose of your research will shape the study you ultimately propose and conduct. If you are doing academic work, your instructor or advisor may push you to be less “descriptive” in your approach, and to focus more on seeking out explanations for what you observe. If you are studying a topic that so far has generated only a small amount of literature, however, you may very well want to conduct exploratory research to generate plausible theories, or descriptive research to understand the scale or characteristics of a particular phenomenon.

The overall purpose of your research will also inform the research questions that you pose. Probably the easiest questions to think of are descriptive research questions. For example, “What is the average student debt load of college graduates?” is a descriptive question—and an important one. In this case, you aren’t trying to identify a causal relationship. You’re simply trying to describe how much debt students carry. When you seek to answer a descriptive research question like this one, you might find yourself generating descriptive statistics —counting the number of instances of a phenomenon, or determining an average, median, or percentage. You can also pursue descriptive research questions using qualitative methods. For instance, you might conduct in-depth interviews or focus groups to gauge the public’s view of student debt, describing the range of opinions on that subject.

In the next section, we’ll focus on explanatory research questions. We will detail one strategy for developing questions based on whether your study is using quantitative methods or qualitative methods. We’ll also connect those two types of research questions to two kinds of empirical analysis—deduction and induction.

Key Takeaways

- Empirical questions can be answered through the gathering and analyzing of data. Normative questions have to do with people’s moral values and opinions and can only be informed, but not answered, through empirical research.

- Exploratory research focuses on tentatively understanding new and emerging phenomena by gathering details and formulating plausible theories. Descriptive research involves a careful measurement of what a phenomenon looks like. Explanatory research tries to understand whether and to what extent two concepts are causally related, and how and why they are related.

- Descriptive questions are helpful for assessing current conditions for policy implementation and other purposes, but they do not investigate causal relationships between variables, which social scientists are often interested in.

The Craft of Sociological Research by Victor Tan Chen; Gabriela León-Pérez; Julie Honnold; and Volkan Aytar is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Sociology Research Guide

- Source Selection & Evaluation

Characteristics of a Research Question

Topic selection, topic verification.

- Search Tips & Strategies

- Online Sources

- Data & Statistics

- Citing Sources [opens a new window] This link opens in a new window

Library Help

Need assistance? Get in touch!

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 931-540-2560

Research questions have a few characteristics.

- They're open-ended . (They can't be answered with a simple yes or no response.)

- They're often measurable through quantitative data or qualitative measures.

- They summarize the issue/topic being researched.

- They may take a fresh look at an issue or try to solve a problem.

In addition, research questions may . . .

- answer how or why questions.

- fit within a cause/effect structure.

- have a pro/con format.

- introduce an argument that is then supported with evidence .

Topic selection is the process you use to choose your topic. This is the more creative side of topic development. There are several steps to this process.

- Brainstorming. Start a list of topics that interest you and are within the guidelines of the assignment. They could be personal, professional, or academic interests. Researching something that interests you is much more enjoyable and will keep you interested in the research process. Write down related words or phrases. These will be useful at the research stage.

- Reshaping the topic. Sometimes you'll choose a topic that's either too narrow or too broad. Find out ways to broaden or narrow the topic so that it's a better size to fit your research assignment. This is where Wikipedia and generic Google searches are okay. You can use those sites to get other ideas of how your topic idea may work. Perform some simple searches to see what information is out there. (Just be sure not to cite Wikipedia or Google.)

- Looking at the body of research. Once you have a topic that you think is a good size, take a look at the body of research that's available for the topic. Check in catalogs and databases. Look at reputable websites. You want to be sure that your topic has an adequate amount of research before you invest too much time into the idea.

- Revising. Throughout this process, be prepared to revise your topic. Don't think that you have to keep the same topic that you started with. Topic revision happens all the time. In fact, we often develop better topics as a result of this revision!

Topic verification is the process you use to confirm your topic is viable for research. This is the more technical side of topic development. There are also several steps to this process.

- Using search strategies. Do some experimental searching in the databases using search strategies . Try different combinations to see what you find. Use your notes from your brainstorming to search for different synonyms or phrases.

- Locating relevant and reliable information. At this stage, you want to see if you can find both a good quality and good quantity of sources. You don't need to read the entirety of the sources right now. Just read their abstracts and identifying information. Confirm that the sources you find support each other. Double-check the authority of the authors. This is the source evaluation stage.

- Verifying information. Once you've confirmed that the sources are reliable and relevant, decide whether or not you can verify the information in the sources. If your sources corrobate each other, you have a good topic. In fact, even if they dispute each other, that is sometimes okay. It just depends on your topic's goal. However, if you cannot verify the reliability of any of your sources' information, then you may need to start over again with a new topic idea.

- << Previous: Source Selection & Evaluation

- Next: Search Tips & Strategies >>

- Last Updated: Dec 7, 2023 11:04 AM

- URL: https://libguides.columbiastate.edu/sociology

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg

- v.24(1); Jan-Mar 2019

Formulation of Research Question – Stepwise Approach

Simmi k. ratan.

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India

1 Department of Community Medicine, North Delhi Municipal Corporation Medical College, New Delhi, India

2 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Batra Hospital and Research Centre, New Delhi, India

Formulation of research question (RQ) is an essentiality before starting any research. It aims to explore an existing uncertainty in an area of concern and points to a need for deliberate investigation. It is, therefore, pertinent to formulate a good RQ. The present paper aims to discuss the process of formulation of RQ with stepwise approach. The characteristics of good RQ are expressed by acronym “FINERMAPS” expanded as feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant, manageable, appropriate, potential value, publishability, and systematic. A RQ can address different formats depending on the aspect to be evaluated. Based on this, there can be different types of RQ such as based on the existence of the phenomenon, description and classification, composition, relationship, comparative, and causality. To develop a RQ, one needs to begin by identifying the subject of interest and then do preliminary research on that subject. The researcher then defines what still needs to be known in that particular subject and assesses the implied questions. After narrowing the focus and scope of the research subject, researcher frames a RQ and then evaluates it. Thus, conception to formulation of RQ is very systematic process and has to be performed meticulously as research guided by such question can have wider impact in the field of social and health research by leading to formulation of policies for the benefit of larger population.

I NTRODUCTION

A good research question (RQ) forms backbone of a good research, which in turn is vital in unraveling mysteries of nature and giving insight into a problem.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] RQ identifies the problem to be studied and guides to the methodology. It leads to building up of an appropriate hypothesis (Hs). Hence, RQ aims to explore an existing uncertainty in an area of concern and points to a need for deliberate investigation. A good RQ helps support a focused arguable thesis and construction of a logical argument. Hence, formulation of a good RQ is undoubtedly one of the first critical steps in the research process, especially in the field of social and health research, where the systematic generation of knowledge that can be used to promote, restore, maintain, and/or protect health of individuals and populations.[ 1 , 3 , 4 ] Basically, the research can be classified as action, applied, basic, clinical, empirical, administrative, theoretical, or qualitative or quantitative research, depending on its purpose.[ 2 ]

Research plays an important role in developing clinical practices and instituting new health policies. Hence, there is a need for a logical scientific approach as research has an important goal of generating new claims.[ 1 ]

C HARACTERISTICS OF G OOD R ESEARCH Q UESTION

“The most successful research topics are narrowly focused and carefully defined but are important parts of a broad-ranging, complex problem.”

A good RQ is an asset as it:

- Details the problem statement

- Further describes and refines the issue under study

- Adds focus to the problem statement

- Guides data collection and analysis

- Sets context of research.

Hence, while writing RQ, it is important to see if it is relevant to the existing time frame and conditions. For example, the impact of “odd-even” vehicle formula in decreasing the level of air particulate pollution in various districts of Delhi.

A good research is represented by acronym FINERMAPS[ 5 ]

Interesting.

- Appropriate

- Potential value and publishability

- Systematic.