Tate Etc 18 June 2018

Opinion Art and Nature

John-Paul Stonard

Art can only ever express the distance between humans and the natural world

Fan Kuan, Travellers among Mountains and Streams c.1000, ink on silk hanging scroll, 206.3 x 103.3 cm

The Collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei

‘Through art we express our conception of what nature is not.’ – Pablo Picasso, 1923

Picasso was right. No matter how naturalistic a work of art, it is always more about art than nature. Works of art show our sense of being apart from the natural world, our stubborn sense of difference from other animals and the the universe in which we find ourselves.

Landscape paintings made in China around the 900s are among the first great poetic statements of this sense of apartness. Fan Kuan’s hanging- scroll painting Travellers among Mountains and Streams , the most famous of this school, shows the ‘unendurable contrast’, as the poet and translator Arthur Waley put it, between the human and natural worlds. Vast cliffs swamp the human world, tiny figures lost in the ink-drawn landscape.

It was an idea taken up in European art many centuries later – a sense that nature was beyond human control. I love James Ward’s great, glowering painting Gordale Scar 1812–14 , in Tate’s collection, but it does nothing to rid you of your deep sense of fear when actually approaching the towering cliffs in the Yorkshire Dales, or to calm your racing heart when scrambling up the dangerous limestone cleft, an ascent both terrifying and impossible to resist. Only at the top, lying exhausted out on the quiet, windswept plateau, is it possible to think of Ward’s painting once again.

Art is constantly driven by the attempt to bridge the apartness of humans and the world. It always fails. In the 20th century, this pursuit became a matter of finding an equivalent not for the appearance, but for the invisible forces of nature. How might you show processes of growth, decay or gravity in art? These are just as much ‘nature’ as a tree in the field. ‘Art imitates nature in her manner of operation’, in the words of the art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy in his 1934 book The Transformation of Nature in Art . This tradition of thought was brilliantly summarised by Clement Greenberg in his essay from 1961 ‘On the Role of Nature in Modern Painting’. He describes how impressionist artists tried to resolve all conflict between art and nature by bringing painting to the verge of abstraction, but it was for the cubists to realise what this meant: ‘When Braque and Picasso stopped trying to imitate the normal appearance of a wineglass and tried instead to approximate, by analogy, the way nature opposed verticals in general to horizontals in general – at this point art caught up with a new conception and feeling of reality that was already emerging in general sensibility as well as in science’. Perhaps this was when Picasso first conceived his ‘not nature’ definition of art.

Ward’s Gordale Scar now seems prophetic of how this feeling of reality has become, in our own times, so dark and dangerous. John Ruskin was among the first to realise that man had ‘desacrilised’ nature, as he put it, viewing it as a source of raw materials to be exploited, emptying it of its mystery. It is no longer simply a feeling of apartness, but also a sense that we own and control nature. But art shows us that we do not. We have laboratories where we recreate the birth of stars. Art is a record of our changing encounter with nature, and reveals the truth that our sense of separation is mere illusion — we are a tiny part of a greater whole. Art ‘cannot stand in competition with nature’, Hegel once wrote, ‘and if it tries it looks like a worm trying to crawl after an elephant’.

John-Paul Stonard is a writer and art historian. He is currently writing a book telling the story of art, from Palaeolithic to the present day, for Bloomsbury.

You Might Like

Issue 43: summer 2018.

Online articles from Tate Etc. magazine featuring Egon Schiele, Francesca Woodman, William Kentridge, Lynn Hershman Leeson, and much more

Sorry, no image available

Art and Democracy

A response to Ai Weiwei's quotation on art's relation to democracy

Mind fields

Jonathon Porritt , Wim Wenders , Siobhan Davies , The Reverend Alan Walker , Richard A. Fortey , José Loosemore , Mark Avery , Michael Palin , Thomas Joshua Cooper , Rick Stein and David Matthews

Tate Etc. introduces eleven personal responses to artworks that reflect the changing face of a nation.

Staring into the contemporary abyss

Simon Morley

In the early eighteenth century Joseph Addison described the notion of the sublime as something that ‘fills the mind with an agreeable kind of horror’. It was an idea feverishly explored by artists such as Turner, John Martin and Caspar David Friedrich, and further taken up by the American abstract painters Rothko and Barnett Newman. But how about now? As Tate comes to the close of a three-year research project, ‘The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language’, Tate Etc. explores how contemporary artists have responded.

Examining the Relationship Between Nature and Art

One of the most remarkable artists to ever live, Henry Matisse once said: “An artist must possess Nature. He must identify himself with her rhythm, by efforts that will prepare the mastery which will later enable him to express himself in his own language.”

For as long as there has been art, artists have been enthused by nature. Apart from providing endless inspiration, many of the mediums that artists use to create their masterpieces such as wood, charcoal, clay, graphite, and water are all products from nature.

The artists of years gone by

Although Vincent van Gogh only sold one painting during his lifetime, he was in a league of his own. He had the ability to bring aspects of nature, such as simple flowers, to life in his paintings. One such a work of art, Irises, is particularly impressive with the life-force of the flowers being almost tangible. Monet is another of the world’s greatest artist who drew inspiration from nature. His series of paintings entitled Lilies is a beautiful showcase of shadows, light, and water and portray his garden in France. Monet’s flowers were one of the main focuses of his work for the latter 30 years of his life, perfectly illustrating what an immense influence the natural beauty around us can have on the imagination of an artist.

Modern artists inspired by nature

Mary Iverson both lives and works in Seattle, Washington and draws inspiration from the immense natural beauty that surrounds her. Her remarkable paintings offer a rather contemporary spin on traditional landscape art portraying the great monuments and national parks of the USA. Mary’s greatest inspiration comes from the picturesque Port of Seattle, and the Rainer, North Cascades, and Olympic National Parks. Mary’s work has been featured on the cover of Juxtapoz Magazine in 2015 and also appeared in Huffington Post, The Boston Review and Foreign Policy Magazine . She also works closely with a number of galleries in Germany, Paris, Amsterdam and Los Angeles and teaches visual art at the Skagit Valley College in Mount Vernon where she passionately shares her love for the natural world with her students.

British artist draws lifelong inspiration from the natural world

British wildlife artist Jonathan Sainsbury is known for his astonishing ability to capture the fleeting moments of the natural world. Having spent most of his life observing and drawing his various subjects, Sainsbury has become a master at using watercolor and watercolor combined with charcoal to effortlessly evoke a feeling of movement in his artwork. Apart from capturing the very essence of countless natural scenes he also draws on nature in a metaphorical way to refer to our everyday lives. Jonathan’s work can be viewed at the Wykeham Gallery in Stockbridge, the Strathearn Gallery, and the Dunkeld Art Exhibition.

Despite the world becoming more technology-driven by the minute, there are very few things that can inspire artistic brilliance quite like nature does. From a single rose petal spiralling to the ground to a mighty fish eagle swooping in on its prey, the countless faces of Mother Nature will continue to mesmerize and provide inspiration for some of the most renowned works of art the world has ever seen.

HANDMADE: a 'small village' in the middle of a big city

If you are not a fan of arts and crafts, be a fan of your own life, launch of the new series of legendary ukrainian photo project razom.ua, tracks: how art can become a tool of communication and a way of making sense of life during war, hatathon 3.0: nft edition, photo is:rael.

HOW THE EU WILL SUPPORT DEVELOPMENT OF CULTURE IN 6 COUNTRIES OF THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP

CREATIVE GEORGIA FORUM IN TEN QUOTES

CV as a Promo Campaign

Main cultural heritage activities at EU level in 2018

The Close Connection Between Art And Nature

By Team Mojarto

An artist must possess Nature. He must identify himself with her rhythm, by efforts that will prepare the mastery which will later enable him to express himself in his language.

-Henry Matisse

There seems to be a close relationship between nature and art. Nature has become a central theme in many famous artists’ artworks. Nature has proven to be one of the most treasured muses known to man. It provides endless inspiration to artists, where they can bring life to nature in their paintings. Many famous artists like Van Gogh and Monet celebrated nature in their artworks. Nature in art is glorified for its sublime and picturesque manifestation on canvas. It is cherished for its intricacy and beauty.

Some philosophers including Aristotle lauded that art can mimic nature. It embodies as a true reflection of the artist’s inner soul. Aristotle even once wrote that “Art not only imitates nature but also completes its deficiencies”. This can be interpreted as art not only recreating the natural world but also creating new ways in which to see it in another light. In other words, art is the missing voice of what nature lacks to speak. Here’s a look at some beautiful artwork that can mesmerize one’s soul and convey a sense of deeper thoughts and perspectives.

The idea offered by nature is endless. It is seen as a way to appreciate nature and bring out the complex human connection to nature. From time immemorial artists and poets have connected nature to human characteristics and mood. Earlier artists used art as a medium to bring out the spirituality in nature. They portrayed every landscape, flower, and insect with a touch of divinity, which was largely attained by the use o light and shade. Art was also a way to explore the world of nature. It brought out the beauty and importance of nature. Many artists portray nature as realistically as possible, which led to the emergence of many movements surrounding art.

Photorealism to abstraction, nature is depicted in every art style. Art movements like Tonalism, naturalism, Plein air, Danube school, and Ecological art were based solely on nature and the natural world.

Landscape Paintings depict natural scenery in art, which is why it is also referred to as nature paintings. Artists have been enamoured by the beauty of nature and have tried to capture nature in all her glory through beautiful landscape paintings. Traditionally, landscape art depicts the surface of the Earth, but there are other sorts of landscapes that are also depicted extensively in art, such as moonscapes, skyscapes, seascapes among others.

Related Articles

Amrita sher-gil: a savant’s stroke, 4 reasons why we love landscape paintings, unravel 2024: a canvas of infinite possibilities, the intersection of art and literature: exploring the connections between two creative forms.

- Customer Support

- info Shipping Worldwide

FOR COLLECTORS

- Collector’s Support

- Resell Works

- Collector’s FAQ

ART BY PRICE

- Under Rs 25000

- Rs 25000 - Rs 1 Lac

- Rs 1 Lac - Rs 3 Lac

ART CATEGORY

- Digital Art

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture | 3D

- Thota Vaikuntam

- Jyoti Bhatt

- Shobha Broota

- K G Subramanyam

FOR SELLERS

- Sell Your Art

- Mojarto For Sellers

- Seller’s FAQ

- Testimonials

- Work With Us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms And Conditions

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

Copyright OnArt Quest Limited 2021.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Nature in chinese culture.

Wine pouring vessel (Gong)

Night-Shining White

Attributed to Dong Yuan

Finches and bamboo

Emperor Huizong

Scholar viewing a waterfall

Service with Decoration of Flowers and Birds

Landscapes after old masters

- Dong Qichang

Windblown bamboo

Brush holder with “Ode to the Pavilion of the Inebriated Old Man”

- Zhang Xihuang

Grazing Horse

Stately Pines on Mount Hua

Department of Asian Art , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

In no other cultural tradition has nature played a more important role in the arts than in that of China. Since China’s earliest dynastic period, real and imagined creatures of the earth—serpents, bovines, cicadas, and dragons —were endowed with special attributes, as revealed by their depiction on ritual bronze vessels . In the Chinese imagination, mountains were also imbued since ancient times with sacred power as manifestations of nature’s vital energy ( qi ). They not only attracted the rain clouds that watered the farmer’s crops, they also concealed medicinal herbs, magical fruits, and alchemical minerals that held the promise of longevity . Mountains pierced by caves and grottoes were viewed as gateways to other realms—”cave heavens” ( dongtian ) leading to Daoist paradises where aging is arrested and inhabitants live in harmony.

From the early centuries of the Common Era, men wandered in the mountains not only in quest of immortality but to purify the spirit and find renewal. Daoist and Buddhist holy men gravitated to sacred mountains to build meditation huts and establish temples. They were followed by pilgrims, travelers, and sightseers: poets who celebrated nature’s beauty , city dwellers who built country estates to escape the dust and pestilence of crowded urban centers, and, during periods of political turmoil, officials and courtiers who retreated to the mountains as places of refuge.

Early Chinese philosophical and historical texts contain sophisticated conceptions of the nature of the cosmos. These ideas predate the formal development of the native belief systems of Daoism and Confucianism, and, as part of the foundation of Chinese culture, they were incorporated into the fundamental tenets of these two philosophies. Similarly, these ideas strongly influenced Buddhism when it arrived in China around the first century A.D. Therefore, the ideas about nature described below, as well as their manifestation in Chinese gardens , are consistent with all three belief systems.

The natural world has long been conceived in Chinese thought as a self-generating, complex arrangement of elements that are continuously changing and interacting. Uniting these disparate elements is the Dao, or the Way. Dao is the dominant principle by which all things exist, but it is not understood as a causal or governing force. Chinese philosophy tends to focus on the relationships between the various elements in nature rather than on what makes or controls them. According to Daoist beliefs, man is a crucial component of the natural world and is advised to follow the flow of nature’s rhythms. Daoism also teaches that people should maintain a close relationship with nature for optimal moral and physical health.

Within this structure, each part of the universe is made up of complementary aspects known as yin and yang. Yin, which can be described as passive, dark, secretive, negative, weak, feminine, and cool, and yang, which is active, bright, revealed, positive, masculine, and hot, constantly interact and shift from one extreme to the other, giving rise to the rhythm of nature and unending change.

As early as the Han dynasty , mountains figured prominently in the arts. Han incense burners typically resemble mountain peaks, with perforations concealed amid the clefts to emit incense, like grottoes disgorging magical vapors. Han mirrors are often decorated with either a diagram of the cosmos featuring a large central boss that recalls Mount Kunlun, the mythical abode of the Queen Mother of the West and the axis of the cosmos, or an image of the Queen Mother of the West enthroned on a mountain. While they never lost their cosmic symbolism or association with paradises inhabited by numinous beings, mountains gradually became a more familiar part of the scenery in depictions of hunting parks, ritual processions, temples, palaces, and gardens. By the late Tang dynasty , landscape painting had evolved into an independent genre that embodied the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. The prominence of landscape imagery in Chinese art has continued for more than a millennium and still inspires contemporary artists .

Department of Asian Art. “Nature in Chinese Culture.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cnat/hd_cnat.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Clunas, Craig. Art in China . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Fong, Wen C., et al. Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996. See on MetPublications

Hearn, Maxwell K. How to Read Chinese Paintings . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. See on MetPublications

Sullivan, Michael. The Arts of China . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Additional Essays by Department of Asian Art

- Department of Asian Art. “ Mauryan Empire (ca. 323–185 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Zen Buddhism .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Chinese Cloisonné .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Chinese Gardens and Collectors’ Rocks .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Landscape Painting in Chinese Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Kushan Empire (ca. Second Century B.C.–Third Century A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Qin Dynasty (221–206 B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Rinpa Painting Style .” (October 2003)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Jōmon Culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 B.C.) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ The Kano School of Painting .” (October 2003)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style .” (October 2003)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Traditional Chinese Painting in the Twentieth Century .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386–581) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Tang Dynasty (618–907) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Yayoi Culture (ca. 300 B.C.–300 A.D.) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) .” (October 2001)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Scholar-Officials of China .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Kofun Period (ca. 300–710) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shunga Dynasty (ca. Second–First Century B.C.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Lacquerware of East Asia .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Painting Formats in East Asian Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Asuka and Nara Periods (538–794) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Heian Period (794–1185) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Kamakura and Nanbokucho Periods (1185–1392) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Momoyama Period (1573–1615) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Neolithic Period in China .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Muromachi Period (1392–1573) .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Samurai .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shinto .” (October 2002)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Shōguns and Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Asian Art. “ Art of the Edo Period (1615–1868) .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- Chinese Gardens and Collectors’ Rocks

- Landscape Painting in Chinese Art

- Longevity in Chinese Art

- Scholar-Officials of China

- Traditional Chinese Painting in the Twentieth Century

- Chinese Calligraphy

- Chinese Cloisonné

- Chinese Handscrolls

- Chinese Hardstone Carvings

- Chinese Painting

- Daoism and Daoist Art

- East Asian Cultural Exchange in Tiger and Dragon Paintings

- Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.)

- The Japanese Tea Ceremony

- Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

- Mountain and Water: Korean Landscape Painting, 1400–1800

- Music and Art of China

- Painting Formats in East Asian Art

- The Qing Dynasty (1644–1911): Painting

- Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Art

- Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China

- Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279)

- Tang Dynasty (618–907)

- The Vibrant Role of Mingqi in Early Chinese Burials

- Wang Hui (1632–1717)

- Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

- Zen Buddhism

- China, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- China, 1000–1400 A.D.

- China, 1400–1600 A.D.

- China, 1–500 A.D.

- China, 1600–1800 A.D.

- China, 1800–1900 A.D.

- China, 1900 A.D.–present

- China, 2000–1000 B.C.

- China, 500–1000 A.D.

- Calligraphy

- Han Dynasty

- Immortality

- Incense Burner

- Religious Art

- Southern Song Dynasty

- Tang Dynasty

- Yuan Dynasty

Artist or Maker

Online features.

- 82nd & Fifth: “Dream Logic” by Joseph Scheier-Dolberg

- 82nd & Fifth: “Eternity” by Maxwell K. Hearn

- 82nd & Fifth: “Metaphorical” by Shi-yee Liu

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature

Author Webpage

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Consists of four self‐contained essays on the aesthetics of nature, which complement one another by exploring the subject from different points of view. The first is concerned with how the idea of aesthetic appreciation of nature should be understood and proposes that it is best understood as aesthetic appreciation of nature as nature —as what nature actually is. This idea is elaborated by means of accounts of what is meant by nature, what is meant by a response to nature as nature, and what an aesthetic response consists in, and through an examination of the aesthetic relevance of knowledge of nature. The second essay, which is divided into three separate chapters, expounds and critically examines Immanuel Kant's theory of aesthetic judgements about nature. The first of these chapters deals with Kant's account of aesthetic judgements about natural beauty; the second with his claims about the connections between love of natural beauty and morality (which are contrasted with Schiller's claim about love of naive nature); and the third examines his theory of aesthetic judgements about the sublime in nature, rejecting much of Kant's view and proposing an alternative account of the emotion of the sublime. The third essay argues against the assimilation of the aesthetics of nature to that of art, explores the question of what determines the aesthetic properties of a natural item, and attempts to show that the doctrine of positive aesthetics with respect to nature, which maintains that nature unaffected by humanity is such as to make negative aesthetic judgements about the products of the natural world misplaced, is in certain versions false, in others inherently problematic. The fourth essay is a critical survey of much of the most significant recent literature on the aesthetics of nature. Various models of the aesthetic appreciation of nature have been advanced, but none of these is acceptable and, it is argued, no model is needed.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature

Malcolm Budd, The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature , Oxford, 2003, 180pp, $29.95 (hbk), ISBN 0199259658.

Reviewed by Fiona Hughes, University of Essex

This book comprises four essays, each based on previously published articles and capable of being read independently, yet as a whole they constitute a substantial study of the aesthetics of nature. The book has the virtue of serving as an introduction to the uninitiated while deepening the interest of the converted and will be of interest to anyone working in the field of aesthetics. Budd is committed to a catholic perspective allowing for the aesthetic appreciation of nature, art, sport, juggling and much else. [p. 15] But his focus in this book is exclusively on the first of these. He dates a renaissance in the topic to the publication in 1966 of Ronald Hepburn’s highly influential ``Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect of Natural Beauty’, which Budd suggests reversed the priority of artistic over natural beauty prevailing since Hegel. Not surprisingly, given this genealogy, Hegel’s predecessor, Kant, for whom natural beauty was paradigmatic, figures as an important point of reference for Budd’s studies.

The approach is analytical and critical in style. Budd’s aims are descriptive in that he believes that any successful theory will ‘chime in with’ our experience. His preference is for a theory that would be ‘neutral as to the relative importance or priority of art and nature within the field of the aesthetic’. [p. 13] These preferences set the scene for investigations that are rigorous and unpolemical. However, an emphasis on the shortcomings in theories under investigation can be limiting, especially when it comes to seeing the broader picture. In particular, Budd displays a lack of sympathy for Kant’s systematic commitments.

Essay 1 is concerned with what it is to aesthetically appreciate ‘nature as nature’, the Leitmotiv of the book as a whole. In Essay 2 Budd gives an extended, although necessarily selective, reading of Kant’s aesthetics of nature in the Critique of Judgment , focusing on Kant’s account of natural beauty, the relationship of the latter to morality and the sublime in nature. Essay 3 takes issue with those aesthetic theories for which art is the dominant paradigm, even for an aesthetics of nature. Budd then turns to ‘positive aesthetics’, for which everything in unmanipulated nature has a positive aesthetic value. In particular he considers arguments put forward by Allen Carlson, whose environmentally oriented aesthetics stands in contrast to his own account. In Essay 4 Budd gives a helpful, though selective overview of trends in the literature since Hepburn’s article. Carlson figures once again as a major interlocutor, particularly with reference to the way in which knowledge plays a role in aesthetic appreciation. While Carlson believes that Kendall Walton’s distinction between apparent and real properties of artworks can be applied to nature in so far as the latter is capable of being ‘determined by the right categories’, Budd convincingly questions whether such categories could ever be established. His conclusion is that, because of the freedom left to the observer in the face of the variability or ‘relativity’ of phenomena, ‘there is no such thing as the appropriate foci of aesthetic significance in the natural environment or the appropriate boundaries of the setting’[p. 147].

In Essay 1 Budd distinguishes between a weak and a strong form of the aesthetic appreciation of ‘nature as nature’. [pp. 9-10] The weak or ‘external’ form covers those cases where a natural thing or event is liked either not in virtue of being an artwork or in virtue of not being an artwork. Budd calls the first the ‘non-artistic’ and the second the ‘anti-artistic’ version. The strong or ‘internal’ form is only the case when the liking arises in virtue of something being natural. In other words, the natural status of the object or event – Budd uses the neutral term ‘item’ – constitutes a necessary element of one’s appreciation. This is Budd’s own position, which he seeks to elaborate and then apply throughout the rest of the book. He sums it up as:

the idea of a response to a natural item, grounded on its naturalness—on its being a part of nature or on its being a specific kind of natural item—focused on its elements or aspects as structured or interrelated in the item, the item being experienced as intrinsically rewarding, unrewarding, or displeasing, the hedonic character of the reaction being ‘disinterested’.[p.16]

Aesthetic appreciation of ‘nature as nature’ entails an awareness of the object or event falling under the concept of nature and this knowledge is constitutive of our liking for it.

The idea of liking ‘nature as nature’ marks an important difference between Budd and Kant, which can be drawn out by contrasting the ways in which they characterize aesthetic appreciation as ‘free’. Whereas, as we have seen, for Budd the freedom of the spectator arises from the diversity of categories under which nature could be taken up, for Kant the freedom of aesthetic judgment implies that it is not determined by a concept. Budd is, however, right to insist that Kant’s account does not entail that ‘the object must be experienced without its being experienced as falling under a concept (of that natural kind)’. [p. 29] Kant does not insist that we are unaware of the object’s natural kind in finding it aesthetically pleasing, but only that a concept does not determine the pleasure. Budd holds that, nevertheless, Kant has no account of aesthetic appreciation of ‘nature as nature’, in that he insists that when I like something aesthetically, I ‘abstract’ from any empirical concept of it. [p. 29] This would seem to rule out the possibility that my liking could be ‘grounded on its naturalness’ as Budd’s model requires, for although in another frame of mind I know the object to be natural, this does not contribute to my aesthetic appreciation of it.

It is arguable that Kant concedes a greater role to our awareness of the natural status of an aesthetically appreciated object than Budd’s talk of ‘abstraction’ suggests. Paradoxically, we can draw this out from Kant’s claim that the beautiful in nature looks as if it were art, whereas the beautiful in art looks as if it were nature. [ Critique of Judgement AA 306] Budd rejects positions such as Savile’s and Wollheim’s that regard artworks as paradigmatic for our aesthetic appreciation of natural objects. Without entering into an assessment of his response to either (his account of the latter is very brief), I would like to suggest that there is more to Kant’s chiasmic statement than meets the eye. Kant’s suggestion is surely that the natural thing, recognized as natural, is beautiful in so far as it mimics art. But in what sense does it do so? The aesthetically pleasing natural object bears a certain structural similarity to an artwork in so far as it displays purposiveness of form. The artwork, conversely, is only beautiful in so far as, while we are aware that it is an artwork, it nevertheless mimics the purposeless or intention-free appearance of nature. The beautiful hovers between purpose and purposelessness and this indeterminate status is only possible in so far as a natural object mimics art or vice versa . If this is right then there is a sense in which the awareness of the object’s natural status is a necessary condition of, while not determining or engendering, our aesthetic appreciation of it.

Repeatedly Budd argues against the idea that aesthetic appreciation of nature involves seeing the latter as art. An early statement of this central commitment comes when he says that his theme is ‘nature as nature and not as art (or artefact)’ [p. 5]. However there is a distinction between viewing nature as art in a reductive sense and the subjunctive mood of the ‘as if’. Nature can be viewed as if it were art, without in any sense reducing nature to art. Admittedly, conceding this distinction to Kant does not result in an aesthetics of ‘nature as nature’ in Budd’s terms. But this is not because Kant ‘abstracts’ from the natural status of the aesthetic object, but rather because its being natural is not sufficient for it to count as aesthetic. If it is to qualify as such, it must be recognized as nature and yet at the same time mimic art. To say that nature is seen as if it were art is strictly to say that it is not possible to determine the scene or thing under a concept because of the playful or expansive frame of mind it invites in our response to it.

There is undoubtedly a disagreement between Kant and Budd in so far as the latter holds that ‘relevant knowledge’ makes possible aesthetic responses that would otherwise be impossible. [p. 20] The knowledge now in question is not simply the awareness that the object or event is natural, but rather that further determinations play a role in our aesthetic appreciation of it. In principle, Kant need not have excluded the possibility that knowledge can enhance our aesthetic appreciation, just as he concedes an ancillary role to charm. But he did not entertain such a possibility, blinded perhaps by the need to exclude knowledge as the determining ground of aesthetic pleasure. While Budd denies that knowledge necessarily leads to heightened aesthetic pleasure, he insists that it can do so. The question that arises is whether knowledge is capable not only of ‘transform[ing] one’s aesthetic experience of nature’ [p. 20], but also of engendering it. Budd seems to be on firmer ground in the former case, but he also says the sublime can be ‘produced’ by the addition of knowledge to perception. [p. 22] As he makes no distinction between the sublime and aesthetic response in general here, we must conclude that this would hold for any aesthetic experience. While knowledge is not a necessary condition of aesthetic pleasure, it can, according to Budd, be a sufficient condition. Yet this claim would require a deeper analysis of the role played by knowledge in the internal dynamics of aesthetic appreciation.

Importantly not all knowledge is aesthetically relevant for Budd. Only that which ‘integrate[s] with the perception in such a manner as to generate a new perceptual-cum-imaginative content of experience ’ counts. [my emphasis. p. 22] This distinction is important for the distance at which Budd stands to Carlson’s ‘natural environmental model’ of aesthetics of nature, discussed in Essays 3 and 4. Whereas Carlson insists that common sense or natural-scientific knowledge of nature is essential to the aesthetic appreciation of nature, Budd asks how we can delimit the knowledge that is aesthetically relevant. [p. 136] Whereas Carlson’s account threatens to deaden aesthetic affect under a burden of knowledge, Budd’s focus on the emergence of new perceptions through the intermediary of imagination discovers a criterion of aesthetic relevance for knowledge. Budd does not much develop this idea beyond supplying an extended range of examples in Essay 1, nor does he do so in the critical reconstructive discussion of Essay 4. Nevertheless it is one of the most valuable ideas he offers and reveals a place for knowledge in aesthetics, which it would be possible to combine with the Kantian insight that the latter is not reducible to cognitive, moral or other, including environmental, interests. This insight could have been developed into an account of how different orientations overlap in the aesthetic case, without their determining it. This could allow us to see how aesthetic freedom fosters our capacity not only for cognitive open-mindedness, but also for moral impartiality.

However such a development of his account of the generative role of knowledge would almost certainly go against Budd’s instincts. In Essay II he reveals himself to be skeptical about Kant’s systematic aspirations. While there is much in his reading of Kant that is of great value, two points are particularly telling. Firstly, Budd is unconvinced by Kant’s attempt to link aesthetic judgment to morality through their shared formal status. With characteristic incisiveness, he points out the distinction between the formal status of the categorical imperative that concerns any maxim or principle of action’s ‘ accordance or conflict with the requirement of willed universality ’ and ‘the form of a beautiful object’ that is nothing other than ‘ the structure of its elements ’. [p. 57] The transition from aesthetics to morality is unsuccessful because ‘the existence of natural beauty … reveals only that nature is hospitable to the aesthetic exercise of our cognitive powers’. It does not concern ‘our ability to realize our moral ends’. [pp. 56-7] The second issue is that of Kant’s much criticized use of a psychological idiom, in that he tries to explain the possibility of knowledge and aesthetic appreciation through a ‘murky’ [p. 31] investigation of mental faculties. Budd says that this amounts either to a ‘picturesque redescription of the experience’ or ‘a priori speculation about psychological processes’. In the first case it is ‘unenlightening’, while in the second ‘it needs to be replaced by an empirically well-founded account’. [p. 34] These two criticisms are related, for it is by means of faculty theory that Kant attempts to show the systematic connection between aesthetics, morality and cognition.

Kant’s reason for writing a third critique was not simply the discovery of a distinct species of aesthetic judgment, but the coincidence of this event with the possibility of revealing a bridge between cognition and morality, thus completing the critical system. While Budd is right that the formal status of aesthetic judgment and of morality are distinct from one another, it would be possible to show how they are linked within a systematic account of Kant’s formalism. I can only sketch what would be an intricate argument. The form of an object or the ‘structure of its elements’ invites a formal judgment in which the imagination is in harmony with the understanding without determination by an empirical or categorial rule. We are able to give the rule to ourselves (this counts as ‘heautonomy’), even though in response to something given to us in experience. This is a first step to revealing our capacity for the autonomous use of reason. It is strictly a preparation or propadeutic for the moral ability to judge according to the form of the moral law. Whereas it would be impossible to move directly from the form of the aesthetic object to the form of the moral law, as Budd rightly says, the move is rather from the form of aesthetic judgment to that of action based on a formal principle. The freedom of mind both imply is the ground of the possibility for the transition from aesthetics to morality. As aesthetics is based on the subjective conditions of cognition, the giant step from cognition to morality becomes, at least in principle, possible.

JustynZolli-Visual Artist.com

- Artist Statement

- Studies of Rock and Water

- Studies of Trees

- Studies of Skyscapes

- Studies of the Moon

- Studies of Birds

- Justyn Zolli: Selected Drawings [2009]

- ATLAS: VOLUMES I-III

- Of Ships & Light

- ‘Contemplation of Waves’

- ‘Autumn Sea Meditations’

- ‘Elyseum Pass’ mural [2012]

- LEVYDance Mural

- History Painting: Federal Mural Project I

- Portfolio 2011

- Portfolio 2010

- Sketchbook IV

- Sketchbook III

- Sketchbook II

- Sketchbook I

- Essay: Understanding Art Through Nature

- Notes on my Creative Process

- Notes on my Painting Practice

- Exhibit Services

- Workshops+Teaching

- Earth Studies

- Artist Talk: Nature As Model

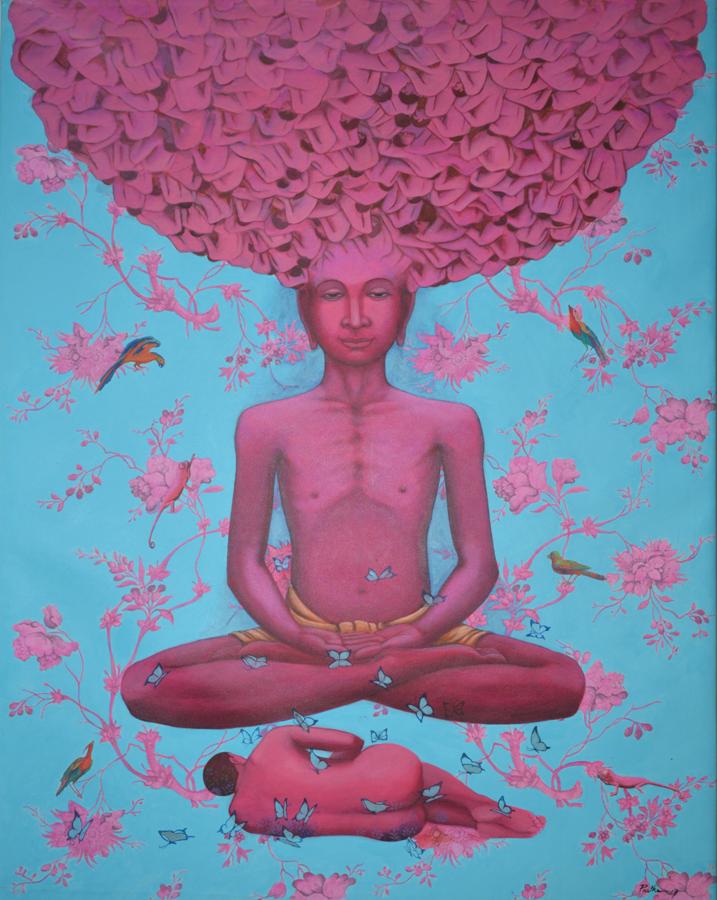

Essay: Understanding Art Through Nature

Justyn zolli, much of my work in the visual arts is centered on understanding and creating compositions derived from the exploration of patterns and organizing dynamics in landscape, to better explore the themes of change and transformation in the world and in us., “nature is an endless combination and repetition of a very few laws. she hums the old well-known air through innumerable variations.” -ralph waldo emerson, ‘history’ essays, what attracts me to this study is the way in which differing forces are reconciled, and how fixed and seemingly static states succeed in incorporating differences in endless variety, using only a simple set of rules and dynamics. i am fascinated by how natural systems can adapt and rearrange their own structures to account for new forces and thereby establish new orders. patterning is the mechanism for how new orders can grow out of older orders, but can also incorporate them into the new paradigm. it seems evident to me that this is the exact process by which culture itself is created. patterns in nature become formed or revealed by instabilities introduced by external forces to a system of relative equilibrium or symmetry. this area of study is called ‘phase transitions’ in the modern science of thermodynamics. it includes the study of various patterns that arise in matter or energy in an attempt to reconcile opposing forces: they include vortices, branching, fracturing, crackling, cellular, concentra, ripple, contornare, polygonal, nubilous, phyllotaxy, labyrinthine, vermiculate, fractal, etc… while this field is being explored in thermodynamic science, only a few older civilizations ever sought to extol these patterns within the visual arts. the ancient chinese landscape painters of the taoist lineages are a notable example. the old chinese sages used the term ‘ li ’ which meant ‘natural principle’. li eventually became a standard study for ink painters and scholar-artists, arguably reaching its highest expression with the mountain landscape painters of the sung dynasty in the 11 th and 12 th centuries., “speaking of painting in its finest essentials, one must read widely in the documents and histories, ascend mountains, and trace rivers to their source, and only then can one create one’s idea’s.” – k’un-ts’an,, (zen painter 14th century), for many years now i have been studying these processes as the requisite research to developing a personal approach to abstract painting and organic design. to that end, i have been studying these principles by direct observation and primary experience. this has led me to travel and study the land in vast, remote wilderness preserves and national parks throughout north america. such wilderness ecosystems have included old-growth forests, tide-pools, alpine mountaintops, wetlands, high and low deserts, salt flats, cliff erosions, dry plains, canyons, underground cavern complexes, coastal ranges, and volcanic formations, among others. i have also collected and published my analysis into several volumes of photography, which describe sets of visual correspondences in natural forms across differing ecosystems. in a sense therefore, all my work is ‘earth-centered’ and ecology-inspired, be it in the synthetic art of painting, the analytic art of photography, or in the application of organic design. my concern artistically is of approaching the subject of landscape as dynamic and abstract, yet the underlying idea has always been broadly one of transformation, transmutation, and change from one state of being into another., “the equilibrium phase transition, like the abrupt transitions that characterize much of pattern formation are spontaneous, global, and often symmetry breaking changes of state that happen when a threshold is broken.”- philip ball (the self made tapestry), the transformation from one state to another is the basis of all such ‘alchemy’, and change itself is really the only universal constant. all matter on our beautiful earth once existed inside the fiery belly of some distant star. so creation is not really a matter of purity versus impurity, as those old alchemists thought. more simply, it is a change in the organizing systems. in this way, the universe creates itself. the more this is grasped, the more interconnection we will feel with great nature. this interconnection is one that every age must rediscover for itself in its own language. every generation of poets and artists must sing these songs anew., “i believe now there is no school worth its existence except as it’s a form of nature study — true nature study — dedicated to that first, foremost, and all the time. man is a phase of nature, and only as he is related to nature does he really matter…”, -frank lloyd wright. (education and art on behalf of life), so what are the implications of such a message what is the point of researching nature and then pictorially describing the phase transitions of one elegant pattern engaging another in space the purpose is to convey and speak eloquently of the change we are all a part of, and then attempt to convey it in humanistic and poetic terms through the visual arts. the message for this civilization is that we are still evolving , still in a change-state, as is all of nature. furthermore, this transition is intrinsic and interconnected to our very being., we are an expression of great nature. i believe art can be a noble means of reminding us of this understanding. a reconnection with this knowledge is urgent in our current age. our ecological ignorance is threatening our collective future on this planet. by using the poetic language of art to speak to others of the dynamic forces in nature, i am attempting to remind them of their own deep but perhaps unaware connection. in an age of global warming, floating garbage islands, and undersea oil geysers, we need to become aware of our relationship to our living planet in more conscious way, and i believe art to be a very powerful vehicle for this message., [justyn zolli, 2010].

Blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

These are just as much ‘nature’ as a tree in the field. ‘Art imitates nature in her manner of operation’, in the words of the art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy in his 1934 book The Transformation of Nature in Art. This tradition of thought was brilliantly summarised by Clement Greenberg in his essay from 1961 ‘On the Role of Nature in ...

Nature in Art is a British museum devoted entirely to artwork inspired by nature. They have an extensive collection of artwork covering a 1500 year time period, representing over 60 countries and cultures. In addition to their permanent collection, they have special exhibitions as well as classes and events for adults and children.

One of the most remarkable artists to ever live, Henry Matisse once said: “An artist must possess Nature. He must identify himself with her rhythm, by efforts that will prepare the mastery which will later enable him to express himself in his own language.”. For as long as there has been art, artists have been enthused by nature.

Photorealism to abstraction, nature is depicted in every art style. Art movements like Tonalism, naturalism, Plein air, Danube school, and Ecological art were based solely on nature and the natural world. Forest Stream by Sujata Joshi. Landscape Paintings depict natural scenery in art, which is why it is also referred to as nature paintings.

In Romantic art, nature—with its uncontrollable power, unpredictability, and potential for cataclysmic extremes—offered an alternative to the ordered world of Enlightenment thought. The violent and terrifying images of nature conjured by Romantic artists recall the eighteenth-century aesthetic of the Sublime.

In no other cultural tradition has nature played a more important role in the arts than in that of China. Since China’s earliest dynastic period, real and imagined creatures of the earth—serpents, bovines, cicadas, and dragons—were endowed with special attributes, as revealed by their depiction on ritual bronze vessels.

The third essay argues against the assimilation of the aesthetics of nature to that of art, explores the question of what determines the aesthetic properties of a natural item, and attempts to show that the doctrine of positive aesthetics with respect to nature, which maintains that nature unaffected by humanity is such as to make negative ...

In Essay 2 Budd gives an extended, although necessarily selective, reading of Kant’s aesthetics of nature in the Critique of Judgment, focusing on Kant’s account of natural beauty, the relationship of the latter to morality and the sublime in nature. Essay 3 takes issue with those aesthetic theories for which art is the dominant paradigm ...

Justyn Zolli Essay 2010 I. Much of my work in the Visual Arts is centered on understanding and creating compositions derived from the exploration of patterns and organizing dynamics in Landscape, to better explore the themes of change and transformation in the world and in us. “Nature is an endless combination and repetition of a….