Overview and General Information about Oral Presentation

- Daily Presentations During Work Rounds

- The New Patient Presentation

- The Holdover Admission Presentation

- Outpatient Clinic Presentations

- The structure of presentations varies from service to service (e.g. medicine vs. surgery), amongst subspecialties, and between environments (inpatient vs. outpatient). Applying the correct style to the right setting requires that the presenter seek guidance from the listeners at the outset.

- Time available for presenting is rather short, which makes the experience more stressful.

- Individual supervisors (residents, faculty) often have their own (sometimes quirky) preferences regarding presentation styles, adding another layer of variability that the presenter has to manage.

- Students are evaluated/judged on the way in which they present, with faculty using this as one way of gauging a student’s clinical knowledge.

- Done well, presentations promote efficient, excellent care. Done poorly, they promote tedium, low morale, and inefficiency.

General Tips:

- Practice, Practice, Practice! Do this on your own, with colleagues, and/or with anyone who will listen (and offer helpful commentary) before you actually present in front of other clinicians. Speaking "on-the-fly" is difficult, as rapidly organizing and delivering information in a clear and concise fashion is not a naturally occurring skill.

- Immediately following your presentations, seek feedback from your listeners. Ask for specifics about what was done well and what could have been done better – always with an eye towards gaining information that you can apply to improve your performance the next time.

- Listen to presentations that are done well – ask yourself, “Why was it good?” Then try to incorporate those elements into your own presentations.

- Listen to presentations that go poorly – identify the specific things that made it ineffective and avoid those pitfalls when you present.

- Effective presentations require that you have thought through the case beforehand and understand the rationale for your conclusions and plan. This, in turn, requires that you have a good grasp of physiology, pathology, clinical reasoning and decision-making - pushing you to read, pay attention, and in general acquire more knowledge.

- Think about the clinical situation in which you are presenting so that you can provide a summary that is consistent with the expectations of your audience. Work rounds, for example, are clearly different from conferences and therefore mandate a different style of presentation.

- Presentations are the way in which we tell medical stories to one another. When you present, ask yourself if you’ve described the story in an accurate way. Will the listener be able to “see” the patient the same way that you do? Can they come to the correct conclusions? If not, re-calibrate.

- It's O.K. to use notes, though the oral presentation should not simply be reduced to reading the admission note – rather, it requires appropriate editing/shortening.

- In general, try to give your presentations on a particular service using the same order and style for each patient, every day. Following a specific format makes it easier for the listener to follow, as they know what’s coming and when they can expect to hear particular information. Additionally, following a standardized approach makes it easier for you to stay organized, develop a rhythm, and lessens the chance that you’ll omit elements.

Specific types of presentations

There are a number of common presentation-types, each with its own goals and formats. These include:

- Daily presentations during work rounds for patients known to a service.

- Newly admitted patients, where you were the clinician that performed the H&P.

- Newly admitted patients that were “handed off” to the team in the morning, such that the H&P was performed by others.

- Outpatient clinic presentations, covering several common situations.

Key elements of each presentation type are described below. Examples of how these would be applied to most situations are provided in italics. The formats are typical of presentations done for internal medicine services and clinics.

Note that there is an acceptable range of how oral presentations can be delivered. Ultimately, your goal is to tell the correct story, in a reasonable amount of time, so that the right care can be delivered. Nuances in the order of presentation, what to include, what to omit, etc. are relatively small points. Don’t let the pursuit of these elements distract you or create undue anxiety.

Daily presentations during work rounds of patients that you’re following:

- Organize the presenter (forces you to think things through)

- Inform the listener(s) of 24 hour events and plan moving forward

- Promote focused discussion amongst your listeners and supervisors

- Opportunity to reassess plan, adjust as indicated

- Demonstrate your knowledge and engagement in the care of the patient

- Rapid (5 min) presentation of the key facts

Key features of presentation:

- Opening one liner: Describe who the patient is, number of days in hospital, and their main clinical issue(s).

- 24-hour events: Highlighting changes in clinical status, procedures, consults, etc.

- Subjective sense from the patient about how they’re feeling, vital signs (ranges), and key physical exam findings (highlighting changes)

- Relevant labs (highlighting changes) and imaging

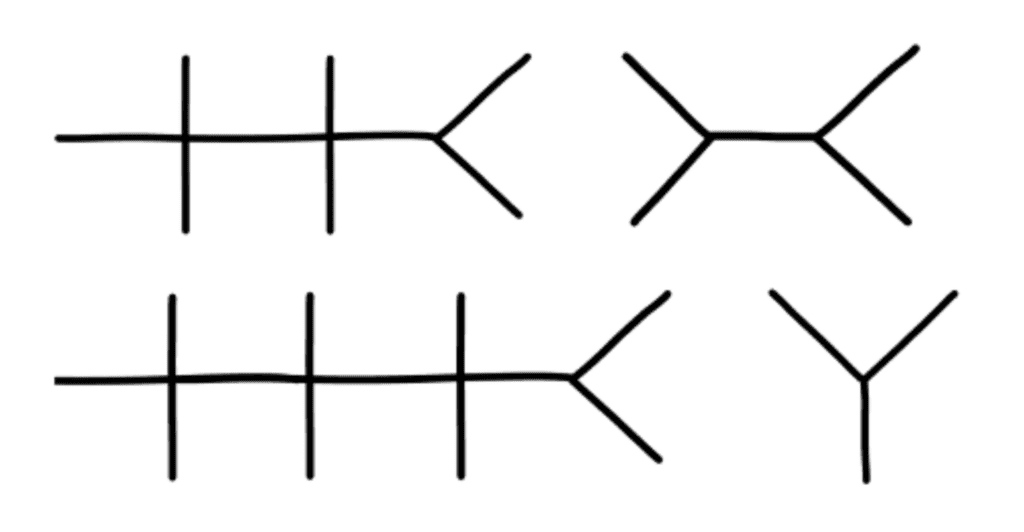

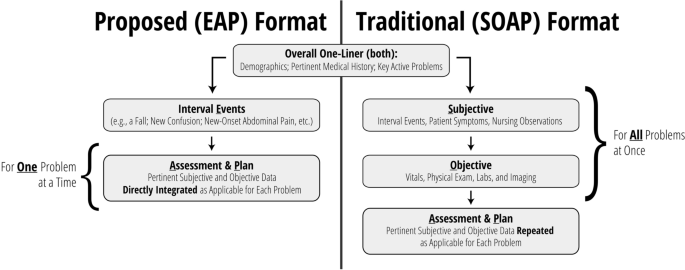

- Assessment and Plan : Presented by problem or organ systems(s), using as many or few as are relevant. Early on, it’s helpful to go through the main categories in your head as a way of making sure that you’re not missing any relevant areas. The broad organ system categories include (presented here head-to-toe): Neurological; Psychiatric; Cardiovascular; Pulmonary; Gastrointestinal; Renal/Genitourinary; Hematologic/Oncologic; Endocrine/Metabolic; Infectious; Tubes/lines/drains; Disposition.

Example of a daily presentation for a patient known to a team:

- Opening one liner: This is Mr. Smith, a 65 year old man, Hospital Day #3, being treated for right leg cellulitis

- MRI of the leg, negative for osteomyelitis

- Evaluation by Orthopedics, who I&D’d a superficial abscess in the calf, draining a moderate amount of pus

- Patient appears well, states leg is feeling better, less painful

- T Max 101 yesterday, T Current 98; Pulse range 60-80; BP 140s-160s/70-80s; O2 sat 98% Room Air

- Ins/Outs: 3L in (2 L NS, 1 L po)/Out 4L urine

- Right lower extremity redness now limited to calf, well within inked lines – improved compared with yesterday; bandage removed from the I&D site, and base had small amount of purulence; No evidence of fluctuance or undrained infection.

- Creatinine .8, down from 1.5 yesterday

- WBC 8.7, down from 14

- Blood cultures from admission still negative

- Gram stain of pus from yesterday’s I&D: + PMNS and GPCs; Culture pending

- MRI lower extremity as noted above – negative for osteomyelitis

- Continue Vancomycin for today

- Ortho to reassess I&D site, though looks good

- Follow-up on cultures: if MRSA, will transition to PO Doxycycline; if MSSA, will use PO Dicloxacillin

- Given AKI, will continue to hold ace-inhibitor; will likely wait until outpatient follow-up to restart

- Add back amlodipine 5mg/d today

- Hep lock IV as no need for more IVF

- Continue to hold ace-I as above

- Wound care teaching with RNs today – wife capable and willing to assist. She’ll be in this afternoon.

- Set up follow-up with PMD to reassess wound and cellulitis within 1 week

The Brand New Patient (admitted by you)

- Provide enough information so that the listeners can understand the presentation and generate an appropriate differential diagnosis.

- Present a thoughtful assessment

- Present diagnostic and therapeutic plans

- Provide opportunities for senior listeners to intervene and offer input

- Chief concern: Reason why patient presented to hospital (symptom/event and key past history in one sentence). It often includes a limited listing of their other medical conditions (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, etc.) if these elements might contribute to the reason for admission.

- The history is presented highlighting the relevant events in chronological order.

- 7 days ago, the patient began to notice vague shortness of breath.

- 5 days ago, the breathlessness worsened and they developed a cough productive of green sputum.

- 3 days ago his short of breath worsened to the point where he was winded after walking up a flight of stairs, accompanied by a vague right sided chest pain that was more pronounced with inspiration.

- Enough historical information has to be provided so that the listener can understand the reasons that lead to admission and be able to draw appropriate clinical conclusions.

- Past history that helps to shed light on the current presentation are included towards the end of the HPI and not presented later as “PMH.” This is because knowing this “past” history is actually critical to understanding the current complaint. For example, past cardiac catheterization findings and/or interventions should be presented during the HPI for a patient presenting with chest pain.

- Where relevant, the patient's baseline functional status is described, allowing the listener to understand the degree of impairment caused by the acute medical problem(s).

- It should be explicitly stated if a patient is a poor historian, confused or simply unaware of all the details related to their illness. Historical information obtained from family, friends, etc. should be described as such.

- Review of Systems (ROS): Pertinent positive and negative findings discovered during a review of systems are generally incorporated at the end of the HPI. The listener needs this information to help them put the story in appropriate perspective. Any positive responses to a more inclusive ROS that covers all of the other various organ systems are then noted. If the ROS is completely negative, it is generally acceptable to simply state, "ROS negative.”

- Other Past Medical and Surgical History (PMH/PSH): Past history that relates to the issues that lead to admission are typically mentioned in the HPI and do not have to be repeated here. That said, selective redundancy (i.e. if it’s really important) is OK. Other PMH/PSH are presented here if relevant to the current issues and/or likely to affect the patient’s hospitalization in some way. Unrelated PMH and PSH can be omitted (e.g. if the patient had their gall bladder removed 10y ago and this has no bearing on the admission, then it would be appropriate to leave it out). If the listener really wants to know peripheral details, they can read the admission note, ask the patient themselves, or inquire at the end of the presentation.

- Medications and Allergies: Typically all meds are described, as there’s high potential for adverse reactions or drug-drug interactions.

- Family History: Emphasis is placed on the identification of illnesses within the family (particularly among first degree relatives) that are known to be genetically based and therefore potentially heritable by the patient. This would include: coronary artery disease, diabetes, certain cancers and autoimmune disorders, etc. If the family history is non-contributory, it’s fine to say so.

- Social History, Habits, other → as relates to/informs the presentation or hospitalization. Includes education, work, exposures, hobbies, smoking, alcohol or other substance use/abuse.

- Sexual history if it relates to the active problems.

- Vital signs and relevant findings (or their absence) are provided. As your team develops trust in your ability to identify and report on key problems, it may become acceptable to say “Vital signs stable.”

- Note: Some listeners expect students (and other junior clinicians) to describe what they find in every organ system and will not allow the presenter to say “normal.” The only way to know what to include or omit is to ask beforehand.

- Key labs and imaging: Abnormal findings are highlighted as well as changes from baseline.

- Summary, assessment & plan(s) Presented by problem or organ systems(s), using as many or few as are relevant. Early on, it’s helpful to go through the main categories in your head as a way of making sure that you’re not missing any relevant areas. The broad organ system categories include (presented here head-to-toe): Neurological; Psychiatric; Cardiovascular; Pulmonary; Gastrointestinal; Renal/Genitourinary; Hematologic/Oncologic; Endocrine/Metabolic; Infectious; Tubes/lines/drains; Disposition.

- The assessment and plan typically concludes by mentioning appropriate prophylactic considerations (e.g. DVT prevention), code status and disposition.

- Chief Concern: Mr. H is a 50 year old male with AIDS, on HAART, with preserved CD4 count and undetectable viral load, who presents for the evaluation of fever, chills and a cough over the past 7 days.

- Until 1 week ago, he had been quite active, walking up to 2 miles a day without feeling short of breath.

- Approximately 1 week ago, he began to feel dyspneic with moderate activity.

- 3 days ago, he began to develop subjective fevers and chills along with a cough productive of red-green sputum.

- 1 day ago, he was breathless after walking up a single flight of stairs and spent most of the last 24 hours in bed.

- Diagnosed with HIV in 2000, done as a screening test when found to have gonococcal urethritis

- Was not treated with HAART at that time due to concomitant alcohol abuse and non-adherence.

- Diagnosed and treated for PJP pneumonia 2006

- Diagnosed and treated for CMV retinitis 2007

- Became sober in 2008, at which time interested in HAART. Started on Atripla, a combination pill containing: Efavirenz, Tonofovir, and Emtricitabine. He’s taken it ever since, with no adverse effects or issues with adherence. Receives care thru Dr. Smiley at the University HIV clinic.

- CD4 count 3 months ago was 400 and viral load was undetectable.

- He is homosexual though he is currently not sexually active. He has never used intravenous drugs.

- He has no history of asthma, COPD or chronic cardiac or pulmonary condition. No known liver disease. Hepatitis B and C negative. His current problem seems different to him then his past episode of PJP.

- Review of systems: negative for headache, photophobia, stiff neck, focal weakness, chest pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, urinary symptoms, leg swelling, or other complaints.

- Hypertension x 5 years, no other known vascular disease

- Gonorrhea as above

- Alcohol abuse above and now sober – no known liver disease

- No relevant surgeries

- Atripla, 1 po qd

- Omeprazole 20 mg, 1 PO, qd

- Lisinopril 20mg, qd

- Naprosyn 250 mg, 1-2, PO, BID PRN

- No allergies

- Both of the patient's parents are alive and well (his mother is 78 and father 80). He has 2 brothers, one 45 and the other 55, who are also healthy. There is no family history of heart disease or cancer.

- Patient works as an accountant for a large firm in San Diego. He lives alone in an apartment in the city.

- Smokes 1 pack of cigarettes per day and has done so for 20 years.

- No current alcohol use. Denies any drug use.

- Sexual History as noted above; has sex exclusively with men, last partner 6 months ago.

- Seated on a gurney in the ER, breathing through a face-mask oxygen delivery system. Breathing was labored and accessory muscles were in use. Able to speak in brief sentences, limited by shortness of breath

- Vital signs: Temp 102 F, Pulse 90, BP 150/90, Respiratory Rate 26, O2 Sat (on 40% Face Mask) 95%

- HEENT: No thrush, No adenopathy

- Lungs: Crackles and Bronchial breath sounds noted at right base. E to A changes present. No wheezing or other abnormal sounds noted over any other area of the lung. Dullness to percussion was also appreciated at the right base.

- Cardiac: JVP less than 5 cm; Rhythm was regular. Normal S1 and S2. No murmurs or extra heart sounds noted.

- Abdomen and Genital exams: normal

- Extremities: No clubbing, cyanosis or edema; distal pulses 2+ and equal bilaterally.

- Skin: no eruptions noted.

- Neurological exam: normal

- WBC 18 thousand with 10% bands;

- Normal Chem 7 and LFTs.

- Room air blood gas: pH of 7.47/ PO2 of 55/PCO2 of 30.

- Sputum gram stain remarkable for an abundance of polys along with gram positive diplococci.

- CXR remarkable for dense right lower lobe infiltrate without effusion.

- Monitored care unit, with vigilance for clinical deterioration.

- Hypertension: given significant pneumonia and unclear clinical direction, will hold lisinopril. If BP > 180 and or if clear not developing sepsis, will consider restarting.

- Low molecular weight heparin

- Code Status: Wishes to be full code full care, including intubation and ICU stay if necessary. Has good quality of life and hopes to return to that functional level. Wishes to reconsider if situation ever becomes hopeless. Older brother Tom is surrogate decision maker if the patient can’t speak for himself. Tom lives in San Diego and we have his contact info. He is aware that patient is in the hospital and plans on visiting later today or tomorrow.

- Expected duration of hospitalization unclear – will know more based on response to treatment over next 24 hours.

The holdover admission (presenting data that was generated by other physicians)

- Handoff admissions are very common and present unique challenges

- Understand the reasons why the patient was admitted

- Review key history, exam, imaging and labs to assure that they support the working diagnostic and therapeutic plans

- Does the data support the working diagnosis?

- Do the planned tests and consults make sense?

- What else should be considered (both diagnostically and therapeutically)?

- This process requires that the accepting team thoughtfully review their colleagues efforts with a critical eye – which is not disrespectful but rather constitutes one of the main jobs of the accepting team and is a cornerstone of good care *Note: At some point during the day (likely not during rounds), the team will need to verify all of the data directly with the patient.

- 8-10 minutes

- Chief concern: Reason for admission (symptom and/or event)

- Temporally presented bullets of events leading up to the admission

- Review of systems

- Relevant PMH/PSH – historical information that might affect the patient during their hospitalization.

- Meds and Allergies

- Family and Social History – focusing on information that helps to inform the current presentation.

- Habits and exposures

- Physical exam, imaging and labs that were obtained in the Emergency Department

- Assessment and plan that were generated in the Emergency Department.

- Overnight events (i.e. what happened in the Emergency Dept. and after the patient went to their hospital room)? Responses to treatments, changes in symptoms?

- How does the patient feel this morning? Key exam findings this morning (if seen)? Morning labs (if available)?

- Assessment and Plan , with attention as to whether there needs to be any changes in the working differential or treatment plan. The broad organ system categories include (presented here head-to-toe): Neurological; Psychiatric; Cardiovascular; Pulmonary; Gastrointestinal; Renal/Genitourinary; Hematologic/Oncologic; Endocrine/Metabolic; Infectious; Tubes/lines/drains; Disposition.

- Chief concern: 70 yo male who presented with 10 days of progressive shoulder pain, followed by confusion. He was brought in by his daughter, who felt that her father was no longer able to safely take care for himself.

- 10 days ago, Mr. X developed left shoulder pain, first noted a few days after lifting heavy boxes. He denies falls or direct injury to the shoulder.

- 1 week ago, presented to outside hospital ER for evaluation of left shoulder pain. Records from there were notable for his being afebrile with stable vitals. Exam notable for focal pain anteriorly on palpation, but no obvious deformity. Right shoulder had normal range of motion. Left shoulder reported as diminished range of motion but not otherwise quantified. X-ray negative. Labs remarkable for wbc 8, creat 2.2 (stable). Impression was that the pain was of musculoskeletal origin. Patient was provided with Percocet and told to see PMD in f/u

- Brought to our ER last night by his daughter. Pain in shoulder worse. Also noted to be confused and unable to care for self. Lives alone in the country, home in disarray, no food.

- ROS: negative for falls, prior joint or musculoskeletal problems, fevers, chills, cough, sob, chest pain, head ache, abdominal pain, urinary or bowel symptoms, substance abuse

- Hypertension

- Coronary artery disease, s/p LAD stent for angina 3 y ago, no symptoms since. Normal EF by echo 2 y ago

- Chronic kidney disease stage 3 with creatinine 1.8; felt to be secondary to atherosclerosis and hypertension

- aspirin 81mg qd, atorvastatin 80mg po qd, amlodipine 10 po qd, Prozac 20

- Allergies: none

- Family and Social: lives alone in a rural area of the county, in contact with children every month or so. Retired several years ago from work as truck driver. Otherwise non-contributory.

- Habits: denies alcohol or other drug use.

- Temp 98 Pulse 110 BP 100/70

- Drowsy though arousable; oriented to year but not day or date; knows he’s at a hospital for evaluation of shoulder pain, but doesn’t know the name of the hospital or city

- CV: regular rate and rhythm; normal s1 and s2; no murmurs or extra heart sounds.

- Left shoulder with generalized swelling, warmth and darker coloration compared with Right; generalized pain on palpation, very limited passive or active range of motion in all directions due to pain. Right shoulder appearance and exam normal.

- CXR: normal

- EKG: sr 100; nl intervals, no acute changes

- WBC 13; hemoglobin 14

- Na 134, k 4.6; creat 2.8 (1.8 baseline 4 m ago); bicarb 24

- LFTs and UA normal

- Vancomycin and Zosyn for now

- Orthopedics to see asap to aspirate shoulder for definitive diagnosis

- If aspiration is consistent with infection, will need to go to Operating Room for wash out.

- Urine electrolytes

- Follow-up on creatinine and obtain renal ultrasound if not improved

- Renal dosing of meds

- Strict Ins and Outs.

- follow exam

- obtain additional input from family to assure baseline is, in fact, normal

- Since admission (6 hours) no change in shoulder pain

- This morning, pleasant, easily distracted; knows he’s in the hospital, but not date or year

- T Current 101F Pulse 100 BP 140/80

- Ins and Outs: IVF Normal Saline 3L/Urine output 1.5 liters

- L shoulder with obvious swelling and warmth compared with right; no skin breaks; pain limits any active or passive range of motion to less than 10 degrees in all directions

- Labs this morning remarkable for WBC 10 (from 13), creatinine 2 (down from 2.8)

- Continue with Vancomycin and Zosyn for now

- I already paged Orthopedics this morning, who are en route for aspiration of shoulder, fluid for gram stain, cell count, culture

- If aspirate consistent with infection, then likely to the OR

- Continue IVF at 125/h, follow I/O

- Repeat creatinine later today

- Not on any nephrotoxins, meds renaly dosed

- Continue antibiotics, evaluation for primary source as above

- Discuss with family this morning to establish baseline; possible may have underlying dementia as well

- SC Heparin for DVT prophylaxis

- Code status: full code/full care.

Outpatient-based presentations

There are 4 main types of visits that commonly occur in an outpatient continuity clinic environment, each of which has its own presentation style and purpose. These include the following, each described in detail below.

- The patient who is presenting for their first visit to a primary care clinic and is entirely new to the physician.

- The patient who is returning to primary care for a scheduled follow-up visit.

- The patient who is presenting with an acute problem to a primary care clinic

- The specialty clinic evaluation (new or follow-up)

It’s worth noting that Primary care clinics (Internal Medicine, Family Medicine and Pediatrics) typically take responsibility for covering all of the patient’s issues, though the amount of energy focused on any one topic will depend on the time available, acuity, symptoms, and whether that issue is also followed by a specialty clinic.

The Brand New Primary Care Patient

Purpose of the presentation

- Accurately review all of the patient’s history as well as any new concerns that they might have.

- Identify health related problems that need additional evaluation and/or treatment

- Provide an opportunity for senior listeners to intervene and offer input

Key features of the presentation

- If this is truly their first visit, then one of the main reasons is typically to "establish care" with a new doctor.

- It might well include continuation of therapies and/or evaluations started elsewhere.

- If the patient has other specific goals (medications, referrals, etc.), then this should be stated as well. Note: There may well not be a "chief complaint."

- For a new patient, this is an opportunity to highlight the main issues that might be troubling/bothering them.

- This can include chronic disorders (e.g. diabetes, congestive heart failure, etc.) which cause ongoing symptoms (shortness of breath) and/or generate daily data (finger stick glucoses) that should be discussed.

- Sometimes, there are no specific areas that the patient wishes to discuss up-front.

- Review of systems (ROS): This is typically comprehensive, covering all organ systems. If the patient is known to have certain illnesses (e.g. diabetes), then the ROS should include the search for disorders with high prevalence (e.g. vascular disease). There should also be some consideration for including questions that are epidemiologically appropriate (e.g. based on age and sex).

- Past Medical History (PMH): All known medical conditions (in particular those requiring ongoing treatment) are listed, noting their duration and time of onset. If a condition is followed by a specialist or co-managed with other clinicians, this should be noted as well. If a problem was described in detail during the “acute” history, it doesn’t have to be re-stated here.

- Past Surgical History (PSH): All surgeries, along with the year when they were performed

- Medications and allergies: All meds, including dosage, frequency and over-the-counter preparations. Allergies (and the type of reaction) should be described.

- Social: Work, hobbies, exposures.

- Sexual activity – may include type of activity, number and sex of partner(s), partner’s health.

- Smoking, Alcohol, other drug use: including quantification of consumption, duration of use.

- Family history: Focus on heritable illness amongst first degree relatives. May also include whether patient married, in a relationship, children (and their ages).

- Physical Exam: Vital signs and relevant findings (or their absence).

- Key labs and imaging if they’re available. Also when and where they were obtained.

- Summary, assessment & plan(s) presented by organ system and/or problems. As many systems/problems as is necessary to cover all of the active issues that are relevant to that clinic. This typically concludes with a “health care maintenance” section, which covers age, sex and risk factor appropriate vaccinations and screening tests.

The Follow-up Visit to a Primary Care Clinic

- Organize the presenter (forces you to think things through).

- Accurately review any relevant interval health care events that might have occurred since the last visit.

- Identification of new symptoms or health related issues that might need additional evaluation and/or treatment

- If the patient has no concerns, then verification that health status is stable

- Review of medications

- Provide an opportunity for listeners to intervene and offer input

- Reason for the visit: Follow-up for whatever the patient’s main issues are, as well as stating when the last visit occurred *Note: There may well not be a “chief complaint,” as patients followed in continuity at any clinic may simply be returning for a visit as directed by their doctor.

- Events since the last visit: This might include emergency room visits, input from other clinicians/specialists, changes in medications, new symptoms, etc.

- Review of Systems (ROS): Depth depends on patient’s risk factors and known illnesses. If the patient has diabetes, then a vascular ROS would be done. On the other hand, if the patient is young and healthy, the ROS could be rather cursory.

- PMH, PSH, Social, Family, Habits are all OMITTED. This is because these facts are already known to the listener and actionable aspects have presumably been added to the problem list (presented at the end). That said, these elements can be restated if the patient has a new symptom or issue related to a historical problem has emerged.

- MEDS : A good idea to review these at every visit.

- Physical exam: Vital signs and pertinent findings (or absence there of) are mentioned.

- Lab and Imaging: The reason why these were done should be mentioned and any key findings mentioned, highlighting changes from baseline.

- Assessment and Plan: This is most clearly done by individually stating all of the conditions/problems that are being addressed (e.g. hypertension, hypothyroidism, depression, etc.) followed by their specific plan(s). If a new or acute issue was identified during the visit, the diagnostic and therapeutic plan for that concern should be described.

The Focused Visit to a Primary Care Clinic

- Accurately review the historical events that lead the patient to make the appointment.

- Identification of risk factors and/or other underlying medical conditions that might affect the diagnostic or therapeutic approach to the new symptom or concern.

- Generate an appropriate assessment and plan

- Allow the listener to comment

Key features of the presentation:

- Reason for the visit

- History of Present illness: Description of the sequence of symptoms and/or events that lead to the patient’s current condition.

- Review of Systems: To an appropriate depth that will allow the listener to grasp the full range of diagnostic possibilities that relate to the presenting problem.

- PMH and PSH: Stating only those elements that might relate to the presenting symptoms/issues.

- PE: Vital signs and key findings (or lack thereof)

- Labs and imaging (if done)

- Assessment and Plan: This is usually very focused and relates directly to the main presenting symptom(s) or issues.

The Specialty Clinic Visit

Specialty clinic visits focus on the health care domains covered by those physicians. For example, Cardiology clinics are interested in cardiovascular disease related symptoms, events, labs, imaging and procedures. Orthopedics clinics will focus on musculoskeletal symptoms, events, imaging and procedures. Information that is unrelated to these disciples will typically be omitted. It’s always a good idea to ask the supervising physician for guidance as to what’s expected to be covered in a particular clinic environment.

- Highlight the reason(s) for the visit

- Review key data

- Provide an opportunity for the listener(s) to comment

- 5-7 minutes

- If it’s a consult, state the main reason(s) that the patient was referred as well as who referred them.

- If it’s a return visit, state the reasons why the patient is being followed in the clinic and when the last visit took place

- If it’s for an acute issue, state up front what the issue is Note: There may well not be a “chief complaint,” as patients followed in continuity in any clinic may simply be returning for a return visit as directed

- For a new patient, this highlights the main things that might be troubling/bothering the patient.

- For a specialty clinic, the history presented typically relates to the symptoms and/or events that are pertinent to that area of care.

- Review of systems , focusing on those elements relevant to that clinic. For a cardiology patient, this will highlight a vascular ROS.

- PMH/PSH that helps to inform the current presentation (e.g. past cardiac catheterization findings/interventions for a patient with chest pain) and/or is otherwise felt to be relevant to that clinic environment.

- Meds and allergies: Typically all meds are described, as there is always the potential for adverse drug interactions.

- Social/Habits/other: as relates to/informs the presentation and/or is relevant to that clinic

- Family history: Focus is on heritable illness amongst first degree relatives

- Physical Exam: VS and relevant findings (or their absence)

- Key labs, imaging: For a cardiology clinic patient, this would include echos, catheterizations, coronary interventions, etc.

- Summary, assessment & plan(s) by organ system and/or problems. As many systems/problems as is necessary to cover all of the active issues that are relevant to that clinic.

- Reason for visit: Patient is a 67 year old male presenting for first office visit after admission for STEMI. He was referred by Dr. Goins, his PMD.

- The patient initially presented to the ER 4 weeks ago with acute CP that started 1 hour prior to his coming in. He was found to be in the midst of a STEMI with ST elevations across the precordial leads.

- Taken urgently to cath, where 95% proximal LAD lesion was stented

- EF preserved by Echo; Peak troponin 10

- In-hospital labs were remarkable for normal cbc, chem; LDL 170, hdl 42, nl lfts

- Uncomplicated hospital course, sent home after 3 days.

- Since home, he states that he feels great.

- Denies chest pain, sob, doe, pnd, edema, or other symptoms.

- No symptoms of stroke or TIA.

- No history of leg or calf pain with ambulation.

- Prior to this admission, he had a history of hypertension which was treated with lisinopril

- 40 pk yr smoking history, quit during hospitalization

- No known prior CAD or vascular disease elsewhere. No known diabetes, no family history of vascular disease; He thinks his cholesterol was always “a little high” but doesn’t know the numbers and was never treated with meds.

- History of depression, well treated with prozac

- Discharge meds included: aspirin, metoprolol 50 bid, lisinopril 10, atorvastatin 80, Plavix; in addition he takes Prozac for depression

- Taking all of them as directed.

- Patient lives with his wife; they have 2 grown children who are no longer at home

- Works as a computer programmer

- Smoking as above

- ETOH: 1 glass of wine w/dinner

- No drug use

- No known history of cardiovascular disease among 2 siblings or parents.

- Well appearing; BP 130/80, Pulse 80 regular, 97% sat on Room Air, weight 175lbs, BMI 32

- Lungs: clear to auscultation

- CV: s1 s2 no s3 s4 murmur

- No carotid bruits

- ABD: no masses

- Ext; no edema; distal pulses 2+

- Cath from 4 weeks ago: R dominant; 95% proximal LAD; 40% Cx.

- EF by TTE 1 day post PCI with mild Anterior Hypokinesis, EF 55%, no valvular disease, moderate LVH

- Labs of note from the hospital following cath: hgb 14, plt 240; creat 1, k 4.2, lfts normal, glucose 100, LDL 170, HDL 42.

- EKG today: SR at 78; nl intervals; nl axis; normal r wave progression, no q waves

- Plan: aspirin 81 indefinitely, Plavix x 1y

- Given nitroglycerine sublingual to have at home.

- Reviewed symptoms that would indicate another MI and what to do if occurred

- Plan: continue with current dosages of meds

- Chem 7 today to check k, creatinine

- Plan: Continue atorvastatin 80mg for life

- Smoking cessation: Doing well since discharge without adjuvant treatments, aware of supports.

- Plan: AAA screening ultrasound

- Log In Username Enter your ACP Online username. Password Enter the password that accompanies your username. Remember me Forget your username or password ?

- Privacy Policy

- Career Connection

- Member Forums

© Copyright 2024 American College of Physicians, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 190 North Independence Mall West, Philadelphia, PA 19106-1572 800-ACP-1915 (800-227-1915) or 215-351-2600

If you are unable to login, please try clearing your cookies . We apologize for the inconvenience.

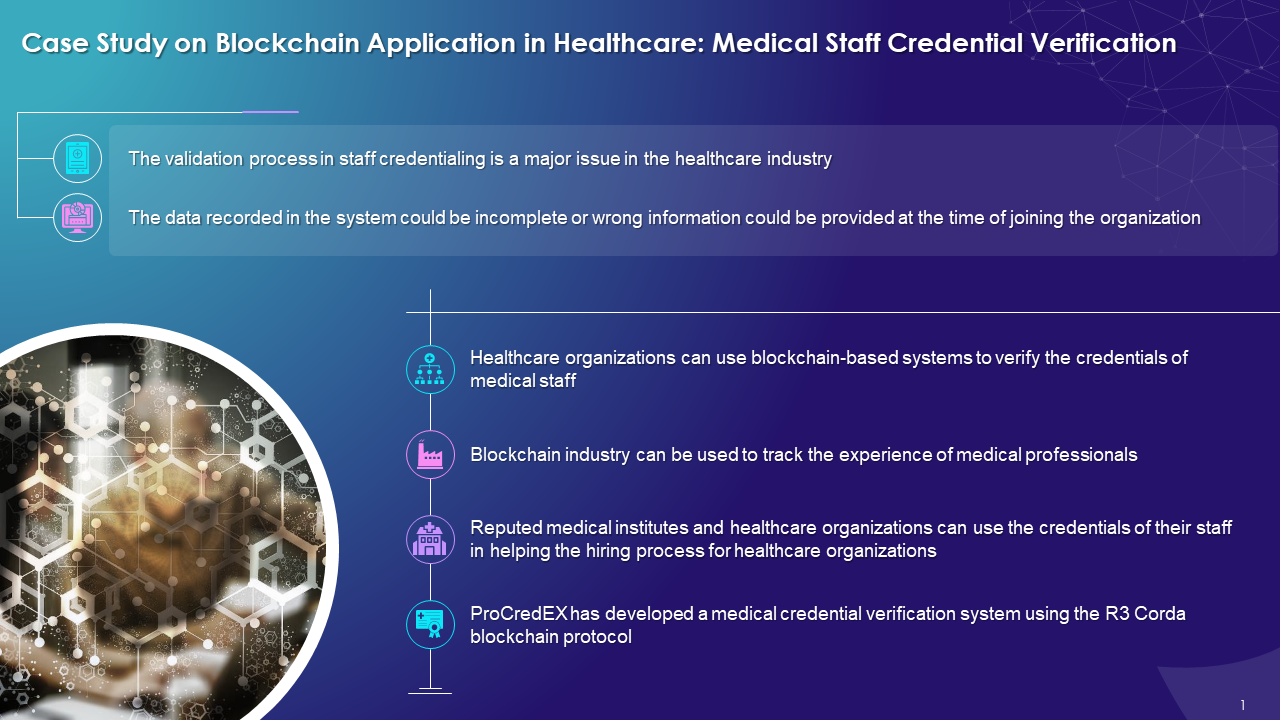

Presenting a Clinical Vignette: Deciding What to Present

If you are scheduled to make a presentation of a clinical vignette, reading this article will improve your performance. We describe a set of practical, proven steps that will guide your preparation of the presentation. The process of putting together a stellar presentation takes time and effort, and we assume that you will be willing to put forth the effort to make your presentation successful. This and subsequent articles will focus on planning, preparation, creating visual aids (slides), and presentation skills. The intent of this series of articles is to help you make a favorable impression and reap the rewards, personal and professional, of a job well done.

The process begins with the creation of an outline of the topics that might be presented at the meeting. Your outline should follow the typical format and sequence for this type of communication: history, physical examination, investigations, patient course, and discussion. This format is chosen because your audience understands it and uses it every day. If you have already prepared a paper for publication, it can be a rich source of content for the topic outline.

To get you started, we have prepared a generic outline to serve as an example. Look over the generic outline to get a sense of what might be addressed in your presentation. We realize that the generic outline will not precisely fit all of the types of cases; nevertheless, think about the larger principle and ask yourself, "How can I adapt this to my situation?" In order to help you visualize the type of content you might include in the outline, an example of a topic outline for a clinical vignette is presented.

Introduction

The main purpose of the introduction is to place the case in a clinical context and explain the importance or relevance of the case. Some case reports begin immediately with the description of the case, and this is perfectly acceptable.

1. Describing the clinical context and relevance

i. Ergotism is characterized by intense, generalized vasoconstriction of small and large blood vessels. ii. Ergotism is rare and therefore difficult to diagnose. iii. Failure to diagnose can lead to significant morbidity.

Case Presentation

The case report should be chronological and detail the history, physical findings, and investigations followed by the patient's course. At this point, you may wish to include more details than you might have time to present, prioritizing the content later.

i. A 34-year-old female smoker has chronic headaches, dyspnea, and burning leg pain. ii. Clinical diagnosis of mitral valve stenosis is made. iii. She returns in one week because of burning pain in the legs. iv. One month after presentation, cardiac catheterization demonstrates severe mitral valve stenosis. v. Elective mitral valve commisurotomy is scheduled, but the patient is admitted to hospital early because of increased burning pain in her feet and a painful right leg.

2. Physical Examination

i. Normal vital signs. ii. No skin findings. iii. Typical findings of mitral stenosis, no evidence of heart failure. iv. Cool, pulseless right leg. v. Normal neurological examination.

3. Investigations

i. Normal laboratory studies. ii. ECG shows left atrial enlargement. iii. Arteriogram of right femoral artery shows subtotal stenosis, collateral filling of the popliteal artery, and pseudoaneurysm formation.

4. Hospital Course

i. Mitral valve commisurotomy is performed, as well as femoral artery thombectomy, balloon dilation, and a patch graft repair. ii. On the fifth postoperative day, the patient experienced a return of burning pain in the right leg. The leg was pale, cool, mottled, and pulseless. iii. The arteriogram of femoral arteries showed smooth segmental narrowing and bilateral vasospasm suggesting large-vessel arteritis complicated by thrombosis. iv. Treatment was initiated with corticosteroids, anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs, and oral vasodilators. v. The patient continued to deteriorate with both legs becoming cool and pulseless. vi. Additional history revealed that the patient abused ergotamine preparations for years (headaches). She used 12 tables daily for the past year and continued to receive ergotamine in hospital on days 2, 6, and 7. vii. Ergotamine preparations were stopped, intravenous nitroprusside was begun, and she showed clinical improvement within 2 hours. Nitroprusside was stopped after 24 hours, and the symptoms did not return. viii. The remainder of hospitalization was uneventful.

The main purpose of the discussion section is to articulate the lessons learned from the case. It should describe how a similar case should be approached in the future. It is sometimes appropriate to provide background information to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms associated with the patient's presentation, findings, investigations, course, or therapy.

1. Discussion

i. The most common cause of ergotism is chronic poisoning found in young females with chronic headaches. ii. Manifestations can include neurological, gastrointestinal, and vascular (list each in a table). iii. Ergotamine poisoning induces intense vasospasm, and venous thrombosis may occur from direct damage to the endothelium. iv. Vasospasm is due primarily to the direct vasoconstrictor effects on the vascular smooth muscle. v. Habitual use of ergotamine can lead to withdrawal headaches leading to a cycle of greater levels of ingestion. vi. In addition to stopping ergotamine, a direct vasodilator is usually prescribed. vii. Lesson 1: Physicians should be alert to the potential of ergotamine toxicity in young women with chronic headaches that present with neurological, gastrointestinal, or ischemic symptoms. viii. Lesson 2: The value of a complete history and checking the medication list.

Creating a topic outline will provide a list of all the topics you might possibly present at the meeting. Since you will have only ten minutes, you will prioritize the topics to determine what to keep and what to cut.

How do you decide what to cut? First, identify the basic information in the three major categories that you simply must present. This represents the "must-say" category. If you have done your job well, the content you have retained will answer the following questions:

What happened to the patient? What was the time course of these events? Why did management follow the lines that it did? What was learned?

After you have identified the "must-say" content, identify information that will help the audience better understand the case. Call this the "elaboration" category. Finally, identify the content that you think the audience would like to know, provided there is enough time, and identify this as the "nice-to-know" category.

Preparing a presentation is an iterative process. As you begin to "fit" your talk into the allotted time, certain content you originally thought of as "elaboration" may be dropped to the "nice-to-know" category due to time constraints. Use the following organizational scheme to efficiently prioritize your outline.

Prioritizing Topics in the Topic Outline

1. Use your completed topic outline.

2. Next to each entry in your outline, prioritize the importance of content.

3. Use the following code system to track your prioritization decisions:

A = Must-Say B = Elaboration C = Nice-to-Know

4. Remember, this is an iterative process; your decisions are not final.

5. Review the outline with your mentor or interested colleagues, and listen to their decisions.

Use the Preparing the Clinical Vignette Presentation Checklist to assist you in preparing the topic outline.

- Free Study Planner

- Residency Consulting

- Free Resources

- Med School Blog

- 1-888-427-7737

The Ultimate Patient Case Presentation Template for Med Students

- by Neelesh Bagrodia

- Apr 06, 2024

- Reviewed by: Amy Rontal, MD

Knowing how to deliver a patient presentation is one of the most important skills to learn on your journey to becoming a physician. After all, when you’re on a medical team, you’ll need to convey all the critical information about a patient in an organized manner without any gaps in knowledge transfer.

One big caveat: opinions about the correct way to present a patient are highly personal and everyone is slightly different. Additionally, there’s a lot of variation in presentations across specialties, and even for ICU vs floor patients.

My goal with this blog is to give you the most complete version of a patient presentation, so you can tailor your presentations to the preferences of your attending and team. So, think of what follows as a model for presenting any general patient.

Here’s a breakdown of what goes into the typical patient presentation.

7 Ingredients for a Patient Case Presentation Template

1. the one-liner.

The one-liner is a succinct sentence that primes your listeners to the patient.

A typical format is: “[Patient name] is a [age] year-old [gender] with past medical history of [X] presenting with [Y].

2. The Chief Complaint

This is a very brief statement of the patient’s complaint in their own words. A common pitfall is when medical students say that the patient had a chief complaint of some medical condition (like cholecystitis) and the attending asks if the patient really used that word!

An example might be, “Patient has chief complaint of difficulty breathing while walking.”

3. History of Present Illness (HPI)

The goal of the HPI is to illustrate the story of the patient’s complaint.

I remember when I first began medical school, I had a lot of trouble determining what was relevant and ended up giving a lot of extra details. Don’t worry if you have the same issue. With time, you’ll learn which details are important.

The OPQRST Framework

In the beginning of your clinical experience, a helpful framework to use is OPQRST:

Describe when the issue started, and if it occurs during certain environmental or personal exposures.

P rovocative

Report if there are any factors that make the pain better or worse. These can be broad, like noting their shortness of breath worsened when lying flat, or their symptoms resolved during rest.

Relay how the patient describes their pain or associated symptoms. For example, does the patient have a burning versus a pressure sensation? Are they feeling weakness, stiffness, or pain?

R egion/Location

Indicate where the pain is located and if it radiates anywhere.

Talk about how bad the pain is for the patient. Typically, a 0-10 pain scale is useful to provide some objective measure.

Discuss how long the pain lasts and how often it occurs.

A Case Study

While the OPQRST framework is great when starting out, it can be limiting.

Let’s take an example where the patient is not experiencing pain and comes in with altered mental status along with diffuse jaundice of the skin and a history of chronic liver disease. You will find that certain sections of OPQRST do not apply.

In this event, the HPI is still a story, but with a different framework. Try to go in chronological order. Include relevant details like if there have been any changes in medications, diet, or bowel movements.

Pertinent Positive and Negative Symptoms

Regardless of the framework you use, the name of the game is pertinent positive and negative symptoms the patient is experiencing.

I’d like to highlight the word “pertinent.” It’s less likely the patient’s chronic osteoarthritis and its management is related to their new onset shortness of breath, but it’s still important for knowing the patient’s complete medical picture. A better place to mention these details would be in the “Past Medical History” section, and reserve the HPI portion for more pertinent history.

As you become exposed to more illness scripts, experience will teach you which parts of the history are most helpful to state. Also, as you spend more time on the wards, you will pick up on which questions are relevant and important to ask during the patient interview.

By painting a clear picture with pertinent positives and negatives during your presentation, the history will guide what may be higher or lower on the differential diagnosis.

Some other important components to add are the patient’s additional past medical/surgical history, family history, social history, medications, allergies, and immunizations.

The HEADSSS Method

Particularly, the social history is an important time to describe the patient as a complete person and understand how their life story may affect their present condition.

One way of organizing the social history is the HEADSSS method:

– H ome living situation and relationships – E ducation and employment – A ctivities and hobbies – D rug use (alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, etc.) Note frequency of use, and if applicable, be sure to add which types of alcohol consumption (like beer versus hard liquor) and forms of drug use. – S exual history (partners, STI history, pregnancy plans) – S uicidality and depression – S piritual and religious history

Again, there’s a lot of variation in presenting social history, so just follow the lead of your team. For example, it’s not always necessary/relevant to obtain a sexual history, so use your judgment of the situation.

4. Review of Symptoms

Oftentimes, most elements of this section are embedded within the HPI. If there are any additional symptoms not mentioned in the HPI, it’s appropriate to state them here.

5. Objective

Vital signs.

Some attendings love to hear all five vital signs: temperature, blood pressure (mean arterial pressure if applicable), heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Others are happy with “afebrile and vital signs stable.” Just find out their preference and stick to that.

Physical Exam

This is one of the most important parts of the patient presentation for any specialty. It paints a picture of how the patient looks and can guide acute management like in the case of a rigid abdomen. As discussed in the HPI section, typically you should report pertinent positives and negatives. When you’re starting out, your attending and team may prefer for you to report all findings as part of your learning.

For example, pulmonary exam findings can be reported as: “Regular chest appearance. No abnormalities on palpation. Lungs resonant to percussion. Clear to auscultation bilaterally without crackles, rhonchi, or wheezing.”

Typically, you want to report the physical exams in a head to toe format: General Appearance, Mental Status, Neurologic, Eyes/Ears/Nose/Mouth/Neck, Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Breast, Abdominal, Genitourinary, Musculoskeletal, and Skin. Depending on the situation, additional exams can be incorporated as applicable.

Now comes reporting pertinent positive and negative labs. Several labs are often drawn upon admission. It’s easy to fall into the trap of reading off all the labs and losing everyone’s attention. Here are some pieces of advice:

You normally can’t go wrong sticking to abnormal lab values.

One qualification is that for a patient with concern for acute coronary syndrome, reporting a normal troponin is essential. Also, stating the normalization of previously abnormal lab values like liver enzymes is important.

Demonstrate trends in lab values.

A lab value is just a single point in time and does not paint the full picture. For example, a hemoglobin of 10g/dL in a patient at 15g/dL the previous day is a lot more concerning than a patient who has been stable at 10g/dL for a week.

Try to avoid editorializing in this section.

Save your analysis of the labs for the assessment section. Again, this can be a point of personal preference. In my experience, the team typically wants the raw objective data in this section.

This is also a good place to state the ins and outs of your patient (if applicable). In some patients, these metrics are strictly recorded and are typically reported as total fluid in and out over the past day followed by the net fluid balance. For example, “1L in, 2L out, net -1L over the past 24 hours.”

6. Diagnostics/Imaging

Next, you’ll want to review any important diagnostic tests and imaging. For example, describe how the EKG and echo look in a patient presenting with chest pain or the abdominal CT scan in a patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

Try to provide your own interpretation to develop your skills and then include the final impression. Also, report if a diagnostic test is still pending.

7. Assessment/Plan

This is the fun part where you get to use your critical thinking (aka doctor) skills! For the scope of this blog, we’ll review a problem-based plan.

It’s helpful to begin with a summary statement that incorporates the one-liner, presenting issue(s)/diagnosis(es), and patient stability.

Then, go through all the problems relevant to the admission. You can impress your audience by casting a wide differential diagnosis and going through the elements of your patient presentation that support one diagnosis over another.

Following your assessment, try to suggest a management plan. In a patient with congestive heart failure exacerbation, initiating a diuresis regimen and measuring strict ins/outs are good starting points.

You may even suggest a follow-up on their latest ejection fraction with an echo and check if they’re on guideline-directed medical therapy. Again, with more time on the clinical wards you’ll start to pick up on what management plan to suggest.

One pointer is to talk about all relevant problems, not just the presenting issue. For example, a patient with diabetes may need to be put on a sliding scale insulin regimen or another patient may require physical/occupational therapy. Just try to stay organized and be comprehensive.

A Note About Patient Presentation Skills

When you’re doing your first patient presentations, it’s common to feel nervous. There may be a lot of “uhs” and “ums.”

Here’s the good news: you don’t have to be perfect! You just need to make a good faith attempt and keep on going with the presentation.

With time, your confidence will build. Practice your fluency in the mirror when you have a chance. No one was born knowing medicine and everyone has gone through the same stages of learning you are!

Practice your presentation a couple times before you present to the team if you have time. Pull a resident aside if they have the bandwidth to make sure you have all the information you need.

One big piece of advice: NEVER LIE. If you don’t know a specific detail, it’s okay to say, “I’m not sure, but I can look that up.” Someone on your team can usually retrieve the information while you continue on with your presentation.

Example Patient Case Presentation Template

Here’s a blank patient case presentation template that may come in handy. You can adapt it to best fit your needs.

Chief Complaint:

History of Present Illness:

Past Medical History:

Past Surgical History:

Family History:

Social History:

Medications:

Immunizations:

Vital Signs : Temp ___ BP ___ /___ HR ___ RR ___ O2 sat ___

Physical Exam:

General Appearance:

Mental Status:

Neurological:

Eyes, Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Neck:

Cardiovascular:

Genitourinary:

Musculoskeletal:

Most Recent Labs:

Previous Labs:

Diagnostics/Imaging:

Impression/Interpretation:

Assessment/Plan:

One-line summary:

#Problem 1:

Assessment:

#Problem 2:

Final Thoughts on Patient Presentations

I hope this post demystified the patient presentation for you. Be sure to stay organized in your delivery and be flexible with the specifications your team may provide.

Something I’d like to highlight is that you may need to tailor the presentation to the specialty you’re on. For example, on OB/GYN, it’s important to include a pregnancy history. Nonetheless, the aforementioned template should set you up for success from a broad overview perspective.

Stay tuned for my next post on how to give an ICU patient presentation. And if you’d like me to address any other topics in a blog, write to me at [email protected] !

Looking for more (free!) content to help you through clinical rotations? Check out these other posts from Blueprint tutors on the Med School blog:

- How I Balanced My Clinical Rotations with Shelf Exam Studying

- How (and Why) to Use a Qbank to Prepare for USMLE Step 2

- How to Study For Shelf Exams: A Tutor’s Guide

About the Author

Hailing from Phoenix, AZ, Neelesh is an enthusiastic, cheerful, and patient tutor. He is a fourth year medical student at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California and serves as president for the Class of 2024. He is applying to surgery programs for residency. He also graduated as valedictorian of his high school and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, obtaining a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering in 2020. He discovered his penchant for teaching when he began tutoring his friends for the SAT and ACT in the summer of 2015 out of his living room. Outside of the academic sphere, Neelesh enjoys surfing at San Onofre Beach and hiking in the Santa Monica Mountains. Twitter: @NeeleshBagrodia LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/neelesh-bagrodia

Related Posts

My Success Story: Passing Step 1 and Shelf Exams During Third Year with Med School Tutors

What Happens if I Fail Step 1 (Now That It’s Pass/Fail)?

What is a Fellow Doctor? A Guide on Fellowships for Eager Medical Students

Search the blog, try blueprint med school study planner.

Create a personalized study schedule in minutes for your upcoming USMLE, COMLEX, or Shelf exam. Try it out for FREE, forever!

Could You Benefit from Tutoring?

Sign up for a free consultation to get matched with an expert tutor who fits your board prep needs

Find Your Path in Medicine

A side by side comparison of specialties created by practicing physicians, for you!

Popular Posts

Need a personalized USMLE/COMLEX study plan?

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present...

How to present clinical cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Ademola Olaitan , medical student 1 ,

- Oluwakemi Okunade , final year medical student 1 ,

- Jonathan Corne , consultant physician 2

- 1 University of Nottingham

- 2 Nottingham University Hospitals

Presenting a patient is an essential skill that is rarely taught

Clinical presenting is the language that doctors use to communicate with each other every day of their working lives. Effective communication between doctors is crucial, considering the collaborative nature of medicine. As a medical student and later as a doctor you will be expected to present cases to peers and senior colleagues. This may be in the setting of handovers, referring a patient to another specialty, or requesting an opinion on a patient.

A well delivered case presentation will facilitate patient care, act a stimulus for timely intervention, and help identify individual and group learning needs. 1 Case presentations are also used as a tool for assessing clinical competencies at undergraduate and postgraduate level.

Medical students are taught how to take histories, examine, and communicate effectively with patients. However, we are expected to learn how to present effectively by observation, trial, and error.

Principles of presentation

Remember that the purpose of the case presentation is to convey your diagnostic reasoning to the listener. By the end of your presentation the examiner should have a clear view of the patient’s condition. Your presentation should include all the facts required to formulate a management plan.

There are no hard and fast rules for a perfect presentation, rather the content of each presentation should be determined by the case, the context, and the audience. For example, presenting a newly admitted patient with complex social issues on a medical ward round will be very different from presenting a patient with a perforated duodenal ulcer who is in need of an emergency laparotomy.

Whether you’re presenting on a busy ward round or during an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), it is important that you are concise yet get across all the important points. Start by introducing patients with identifiers such as age, sex, and occupation, and move on to the complaint that they presented with or the reason that they are in hospital. The presenting complaint is an important signpost and should always be clearly stated at the start of the presentation.

Presenting a history

After you’ve introduced the patient and stated the presenting complaint, you can proceed in a chronological approach—for example, “Mr X came in yesterday with worsening shortness of breath, which he first noticed four days ago.” Alternatively you can discuss each of the problems, starting with the most pertinent and then going through each symptom in turn. This method is especially useful in patients who have several important comorbidities.

The rest of the history can then be presented in the standard format of presenting complaint, history of presenting complaint, medical history, drug history, family history, and social history. Strictly speaking there is no right or wrong place to insert any piece of information. However, in some instances it may be more appropriate to present some information as part of the history of presenting complaints rather than sticking rigidly to the standard format. For example, in a patient who presents with haemoptysis, a mention of relevant risk factors such as smoking or contacts with tuberculosis guides the listener down a specific diagnostic pathway.

Apart from deciding at what point to present particular pieces of information, it is also important to know what is relevant and should be included, and what is not. Although there is some variation in what your seniors might view as important features of the history, there are some aspects which are universally agreed to be essential. These include identifying the chief complaint, accurately describing the patient’s symptoms, a logical sequence of events, and an assessment of the most important problems. In addition, senior medical students will be expected to devise a management plan. 1

The detail in the family and social history should be adapted to the situation. So, having 12 cats is irrelevant in a patient who presents with acute appendicitis but can be relevant in a patient who presents with an acute asthma attack. Discerning the irrelevant from the relevant is not always easy, but it comes with experience. 2 In the meantime, learning about the diseases and their associated features can help to guide you in the things you need to ask about in your history. Indeed, it is impossible to present a good clinical history if you haven’t taken a good history from the patient.

Presenting examination findings

When presenting examination findings remember that the aim is to paint a clear picture of the patient’s clinical status. Help the listener to decide firstly whether the patient is acutely unwell by describing basics such as whether the patient is comfortable at rest, respiratory rate, pulse, and blood pressure. Is the patient pyrexial? Is the patient in pain? Is the patient alert and orientated? These descriptions allow the listener to quickly form a mental picture of the patient’s clinical status. After giving an overall picture of the patient you can move on to present specific findings about the systems in question. It is important to include particular negative findings because they can influence the patient’s management. For example, in a patient with heart failure it is helpful to state whether the patient has a raised jugular venous pressure, or if someone has a large thyroid swelling it is useful to comment on whether the trachea is displaced. Initially, students may find it difficult to know which details are relevant to the case presentation; however, this skill becomes honed with increasing knowledge and clinical experience.

Presenting in an exam

Although the same principles as presenting in other situations also apply in an exam setting, the exam situation differs in the sense that its purpose is for you to show your clinical competence to the examiner.

It’s all about making a good impression. Walk into the room confidently and with a smile. After taking the history or examining the patient, turn to the examiner and look at him or her before starting to present your findings. Avoid looking back at the patient while presenting. A good way to avoid appearing fiddly is to hold your stethoscope behind your back. You can then wring to your heart’s content without the examiner sensing your imminent nervous breakdown.

Start with an opening statement as you would in any other situation, before moving on to the main body of the presentation. When presenting the main body of your history or examination make sure that you show the examiner how your findings are linked to each other and how they come together to support your conclusion.

Finally, a good summary is just as important as a good introduction. Always end your presentation with two or three sentences that summarise the patient’s main problem. It can go something like this: “In summary, this is Mrs X, a lifelong smoker with a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, who has intermittent episodes of chest pain suggestive of stable angina.”

Improving your skills

The RIME model (reporter, interpreter, manager, and educator) gives the natural progression of the clinical skills of a medical student. 3 Early on in clinical practice students are simply reporters of information. As the student progresses and is able to link together symptoms, signs, and investigation results to come up with a differential diagnosis, he or she becomes an interpreter of information. With further development of clinical skills and increasing knowledge students are actively able to suggest management plans. Finally, managers progress to become educators. The development from reporter to manager is reflected in the student’s case presentations.

The key to improving presentation skills is to practise, practise, and then practise some more. So seize every opportunity to present to your colleagues and seniors, and reflect on the feedback you receive. 4 Additionally, by observing colleagues and doctors you can see how to and how not to present.

Remember the purpose of the presentation

Be flexible; the context should dictate the content of the presentation

Always include a presenting complaint

Present your findings in a way that shows understanding

Have a system

Use appropriate terminology

Additional tips for exams

Start with a clear introductory statement and close with a brief summary

After your summary suggest a working diagnosis and a management plan

Practise, practise, practise, and get feedback

Present with confidence, and don’t be put off by an examiner’s poker face

Be honest; do not make up signs to fit in with your diagnosis

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

See “Medical ward rounds” ( Student BMJ 2009;17:98-9, http://archive.student.bmj.com/issues/09/03/life/98.php ).

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: Opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 -3. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Lingard LA, Haber RJ. What do we mean by “relevance”? A clinical and rhetorical definition with implications for teaching and learning the case-presentation format. Acad Med 1999 ; 74 : S124 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med 1999 ; 74 : 1203 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Haber RJ, Lingard LA. Learning oral presentation skills: a rhetorical analysis with pedagogical and professional implications. J Gen Intern Med 2001 ; 16 : 308 -14. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

Presenting Your Case

A Concise Guide for Medical Students

- © 2019

- Clifford D. Packer 0

Professor of Medicinem, Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, Cleveland, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Provides a comprehensive guide to case presentation and related activities

- Covers various types of oral case presentations on the wards, including the traditional new patient presentation, transfers, night float admissions, and brief SOAP presentations on daily rounds

- Prepares medical students for their clerkship evaluations, which depend largely on the quality of their oral presentations

11k Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Front matter, the importance of a good case presentation and why students struggle with it.

Clifford D. Packer

Organization of the Oral Case Presentation

Variations on the oral case presentation, the hpi: a timeline, not a time machine, pertinent positives and negatives, the diagnostic power of description, the assessment and plan, approaches to differential diagnosis, searching and citing the literature, adding value to the oral presentation, teaching rounds: speaking up, getting involved, and learning to accept uncertainty, the art of the 5-minute talk, future directions of the oral case presentation, back matter.

- Oral case presentation

- Differential Diagnosis

- Five-Minute-Talk

About this book

Medical students often struggle when presenting new patients to the attending physicians on the ward. Case presentation is either poorly taught or not taught at all in the first two years of medical school. As a result, students are thrust into the spotlight with only sketchy ideas about how to present, prioritize, edit, and focus their case presentations. They also struggle with producing a broad differential diagnosis and defending their leading diagnosis. This text provides a comprehensive guide to give well-prepared, focused and concise presentations. It also allows students to discuss differential diagnosis, incorporate high-value care, educate their colleagues, and participate actively in the care of their patients.

Linking in-depth discussion of the oral presentation with differential diagnosis and high value care, Presenting Your Case is a valuable resource for medical students, clerkship directors and others who educatestudents on the wards and in the clinic.

Authors and Affiliations

About the author.

Clifford D. Packer, MD

Professor of Medicine

Department of Medicine

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center

Cleveland, OH, USA

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Presenting Your Case

Book Subtitle : A Concise Guide for Medical Students

Authors : Clifford D. Packer

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13792-2

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-13791-5 Published: 14 May 2019

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-13792-2 Published: 29 April 2019

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIV, 196

Number of Illustrations : 8 b/w illustrations, 9 illustrations in colour

Topics : General Practice / Family Medicine

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- UNC Chapel Hill

Case Presentation Skills

Communicating patient care information to colleagues and other health professionals is an essential skill regardless of specialty. Internists have traditionally given special attention to case presentation skills because of the comprehensive nature of patient evaluations and the various settings in which internal medicine is practiced. Students should develop facility with different types of case presentation: written and oral, new patient and follow-up, inpatient and outpatient.

Prerequisite

Basic written and oral case presentation skills, obtained in physical diagnosis courses.

Specific Learning Objectives

- components of comprehensive and abbreviated case presentations (oral and written) and the settings appropriate for each.

- present illness organized chronologically, without repetition, omission, or extraneous information.

- a comprehensive physical examination with detail pertinent to the patient’s problem.

- a succinct and, where appropriate, unified list of all problems identified in the history and physical examination.

- a differential diagnosis for each problem (appropriate to level of training).

- a diagnosis/treatment plan for each problem (appropriate to level of training).

- orally present a new patient’s case in a logical manner, chronologically developing the present illness, summarizing the pertinent positive and negative findings as well as the differential diagnosis and plans for further testing and treatment.

- orally present a follow-up patient’s case, in a focused, problem-based manner that includes pertinent new findings and diagnostic and treatment plans.

- select the appropriate mode of presentation that is pertinent to the clinical situation.

- demonstrate a commitment to improving case presentation skills by regularly seeking feedback on presentations. accurately and objectively record and present data.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The purpose of the oral case presentation is:

- To concisely communicate the findings of your history and exam to other members of your team

- To formulate and address the clinical questions that are important to your patient’s care

On completion of Foundations of Clinical Medicine, students should be able to perform an accurate, complete and well organized comprehensive oral case presentation for a new clinic or hospital patient, and adapt the case presentation to different clinical settings. A comprehensive OCP includes each of these sections:

The oral case presentation is a mechanism for communicating with your team, which may include residents, attending physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists. Your audience may also include the patient and family if it is presented at the hospital bedside.

An oral case presentation includes only a SUBSET of the information that you record in your write-up, the information the team needs to provide care. The write-up contains ALL the facts while the OCP includes the facts needed to understand and address the current issues.

Purpose and format of each section

Identifying information & chief concern (id/cc).

Purpose: Sets the stage and gives a brief synopsis of the patient’s major problem.

Format: Same as in your writeup!

- Identify the patient by name and age. You can also include gender identity, if confirmed.

- Include no more than four medical problems (sometimes there are zero) that are highly relevant to the chief concern. List only the diagnoses here, and elaborate on them in the HPI or PMH.

- Report the chief concern and duration of symptoms

Template: “___ is a ___ year-old with a history of ___ who presents with ___ of ___ duration.”

History of present illness (HPI)

Purpose: Provides a complete account of the presenting problem, including any information from the past medical, family and social history related to that problem.

Content: The same as the HPI in the write up! Most new diagnoses are made based on the HPI so this is the most important part. It should take up 1/3 to 1/2 of your presentation time.