Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 January 2023

Implications of the POCSO Act and determinants of child sexual abuse in India: insights at the state level

- Shrabanti Maity ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5791-3140 1 &

- Pronobesh Ranjan Chakraborty 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 6 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social policy

Child sexual abuse is a worldwide phenomenon, and India is not an exception. The magnitude of this grave crime is underrated because of under-reporting. The reality is that the incidence of child sexual abuse has reached epidemic proportions in India. In 2021 only there were 53,874 cases registered under Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act of 2012. To enable the all-around protection of children, the Indian government administrated the “Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO)” Act of 2012. The act is a comprehensive piece of legislation designed to protect children from crimes including sexual assault, sexual harassment, and pornography. The degree to which this act has improved child protection is therefore an important issue for interrogation. Here, we consider the implications of the POCSO Act (2012) in enhancing children’s protection from sexual abuse and pin-point the role of quality of life together with other social, economic, and demographic determinants in foreshortening POCSO incidences. The empirical analysis of the paper is conducted based on secondary data compiled from National Crime Records Bureau. Our empirical results reveal that the POCSO Act has reduced the Growth rate of incidents of sexual offences against children in India from 4.681% to −4.611. Moreover, our empirical results also reveal that by enhancing the quality of life it is possible to restrict the POCSO incidences across Indian states. In addition, favourable sex-ratio, the increased gross enrolment ratio at the elementary level, the improvement in the judiciary and Public Safety Score of the state also enables the state to restrict the POCSO incidences. Based on our empirical result we recommend that future policies could include, for instance, aiming to improve the quality of life as well as the law and order conditions of the state, and increasing the enrolment of the girl children in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Sayed Fayaz Ahmad, Heesup Han, … Antonio Ariza-Montes

Investigating child sexual abuse material availability, searches, and users on the anonymous Tor network for a public health intervention strategy

Juha Nurmi, Arttu Paju, … David Arroyo

Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies

Marco Solmi, Joaquim Radua, … Paolo Fusar-Poli

Introduction

Around the globe, millions of children irrespective of gender face exploitation and sexual abuse every year. According to UNICEF ( 2022 ), “ About 1 in 10 girls under the age of 20 have been forced to engage in sex or perform other sexual acts ”. In 90% of cases, the accused is known to the victim (UNICEF, 2022 ). Globally, the highest prevalence of Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) is observed in Africa and the corresponding figure is 34.4% (Wihbey, 2011 ; Behere and Mulmule, 2013 ). The reported CSA cases in Europe and America are 9.2% and 10.1%, respectively (Wihbey, 2011 ). The lowest figure may not reflect controlling such horrendous crime but rather may be the consequence of under-reporting (Wihbey, 2011 ). The lowest prevalence of CSA should not be ignored as its scar on the victim should never be ignored (Wihbey, 2011 ). The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data reported in 2006 in the U.S.A., 8.8% of children were victims of child sexual abuse (Miller et al., 2007 ). The reported sexual abuse cases recognised that in 60% of cases victims are within the age of 12 years (Collin-Vézina et al., 2013 ). Barth et al. ( 2013 ) reported every year globally 4% of girls and 2% of boys are victims of CSA and the consequences become extremely severe for about 15% of girls and 6% of boys. The prevalence of CSA in urban China is 4.2% (Chiu et al., 2013 ). The identification of actual global figures concerning CSA is a challenging task because of under-reporting of such crimes (Miller, et al., 2007 ).

India is the home of 472 million children (Chandramouli and General, 2011 ). Children constitute more than one-third of the Indian population (39%). In India, we celebrate “ Children’s Day ” on 14th November, the birthday of the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, who is popularly known as “ Chacha Nehru ”. He dreamt of making India a “ Children’s paradise ”. However, the reality is something else. On 17th November 2020, a 6-year-old girl was raped and then murdered brutally to perform black magic and the accused were arrested under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act (Kanpur (UP), November 17, The Tribune). On 26 th August 2020, a 17-year-old girl was found dead near her house in Uttar Pradesh’s Lakhimpur Kheri district (August 26, 2020, The Indian Express). Before that, another horrendous incident was reported in the same state for a forlorn 13-year-old Dalit girl. Because of the societal status, this case was less talked about. In India, “ child sexual abuse ” is an understated transgression. Only a handful of cases get media attention and the people of India sought justice. Most of the cases remain unexplored. The most talked about “ POCSO ” incident in India was the “ Kathua rape case ”. The case was about “Asifa Bano”, an 8-year-old girl from Rasana village near Kathua in Jammu and Kashmir, India, who was gang-raped and then killed in January 2018 Footnote 1 . By closing our eyes, we cannot deny the reality and the reality is that “ child sexual abuse ” in India has reached an epidemic proportion (Moirangthem, et al., 2015 ; Kshirsagar, 2020 ; Tamilarasi et al., 2020 ; Pallathadka et al., 2021 ; Maity, 2022 ). According to the “ National Crime Record Bureau ” in 2019 the highest “ rate of POCSO ” was reported for Sikkim (44.8%).In that list, Uttar Pradesh(8.6%) was ranked 16th among the twenty-eight Indian states (Crime in Indian, 2019 ). This simply evidences the under and/or un-reporting of “ child sexual abuse ” (Crime in Indian, 2021 ), the report shows that in 2021 only 36.5% of crimes against children are registered under POCSO Act (The Indian Express, September 23, 2022).

The Indian government has administrated the “Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO)” Act, 2012 (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2013 ; https://wcd.nic.in ), a specified law, to ensure children’s protection from mal treatment. “ The Act has come into force with effect from 14 th November 2012 along with the rules framed there under. The POCSO Act, 2012 is a comprehensive law to provide for the protection of children from the offences of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and pornography while safeguarding the interests of the child at every stage of the judicial process by incorporating child-friendly mechanisms for reporting, recording of evidence, investigation and speedy trial of offences through designated Special Courts ” (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2013 ; https://wcd.nic.in ). This act includes “Special Courts”, where the victim child is allowed to record his/her statement on camera in a child-friendly circumstance and simultaneously the child’s identity also remains un revealed. However, this special act is not infallible to protect children from sexual abuse. In 2019, 1510 rape cases in specific and 2091 reported POCSO cases, in general, were filed in Kerala (Kartik. The New Indian Express, 31/01/2020).In fact, in Kerala, children—both boys and girls, have had such horrid experiences at least once in life and the corresponding figure, in this case, are 36% and 35%, respectively (Krishnakumar et al., 2014 ; Moirangthem et al., 2015 ). However, it is not the exceptional one. Between January to June 2019, the total number of registered POCSO cases all over India was 24,212 (Ali, 2019 ).

Child sexual abuse is a global phenomena and a matter of concern for comprehensive existing literature. Researchers observe that CSA health professionals play a crucial role in the identification and protection of children (Fraser et al., 2010 ). Sometimes even a genuine allegation made by a child against a powerful person is reported casually based on the accuser’s disownment. Such reporting reduces the credibility of the incidence (Rubin & Thelen, 1996 ). Researchers also recognise that in most cases assailants are known to the victims (Haque et al., 2019 ; Maity, 2022 ). Concerning the Indian scenario we can say that 90% accused are known to the child (The Times of India, March 1, 2018 ; Maity, 2022 ). Economically weaker and vulnerable are always found to be the soft target for any crime, particularly in developing countries (Bower, 2003 ; Bywaters, et al., 2016 ; Sexton and Sobelson, 2018 ). In India, aged 40 and above, alcoholic, addicted to pornography, illiterate or minor literate, are the common characteristics of the accused of the POCSO Act (2012) (Chowdhuri & Mukhopadhayay, 2016 ).

On the contrary, quality of life indicates the well-being of a state or nation. The “Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI)” helps in quantify the qualitative aspect of life (Morris, 1978 ). The variables utilised for index calculation are well defined (for details see Table 9 in appendices) in Morris’s ( 1978 ) article. To avoid the limitations of GDP as a measure of well-being this measure was developed by Morris ( 1978 ). An improvement in PQLI is supposed to be transmitted to minimise the ethnocentricity of culture and development. Accordingly, a favourable PQLI may indicate an environment for equal opportunities for all, and equal safety for all. Thus, it will be interesting to explore the implication of PQLI in protecting children from sexual offences. Childhood experiences of sexual exploitation adversely affect adulthood’s psychological, physical, and socio-economic well-being and thus deteriorate the adult’s physical quality of life (Downing et al., 2021 ). Childhood experiences of sexual abuse may result in permanent scars on a child’s well-being and quality of life (Chahine, 2014 ). It is noteworthy that earlier studies were concentrated on exploring the consequences of CSA on the physical quality of life. However, the present study unlike the earlier involves in self exploring the consequences of the improvement of PQLI on CSA. It is not worthy that the relation between CSA and PQLI is rare in literature and almost absent in empirical studies where improvement of PQLI’s effect on CSA is explored.

This back drop motivates us to explore the research questions, viz., does the POCSO Act, 2012 has any implication in creating India as a children’s paradise? Simultaneously, we also want to explore, does amplification of the quality of life of Indian citizens and Judiciary and Public Safety Scores help in reducing POCSO incidences? These research questions when unfold, result in twin objectives. Initially, the study explores the aftermaths of the “ Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act ” (POCSO) (2012), on protecting children from sexual offences. Then the paper tries to unfold different socio-economic factors, including “ Quality of Life ” that helps in revamping children’s safety across Indian states. The novelty of the study is that it is the first attempt to explore the role of the POCSO Act (2012), on child sexual abuse. The earlier studies, such as Kshirsagar ( 2020 ), Tamilarasi et al. ( 2020 ), are non-empirical documentation of the POCSO Act (2012).The study by Pallathadka et al. ( 2021 ), is an experimental study investigating the effectiveness of the inclusion of the knowledge of the POCSO Act (2012).

In a teaching programme in reducing CSA the only empirical study we find is Maity ( 2022 ). However, this study mainly focuses on the efficacy of the enhancement of police efficiency in reducing POCSO incidences across Indian states. In this sense, it is the first attempt of such type. Moreover, this study also explores the implication of the improvement of quality of life and improvement of Judiciary and Public Safety (JPS) in the foreshortening of child sexual abuse. This study perhaps is the first attempt of such kind. The present study explores the role of PQLI and JPS scores in foreshortening the CSA and this establishes the novelty of the study. Thus, our contribution to the existing literature is this study tries to test empirically the inevitability of the act in foreshortening CSA in India. Beyond that, this study tries to explore with other factors the role of quality of life in reducing CSA in India.

The study follows the aforementioned sequence: Section “Methods” deals with the materials and methods required for exploring the above-mentioned objectives. Section “Results and Discussion” presents the empirical results with a discussion concerning the implication of POCSO on children’s protection and the identification of the influencing factors of recorded POCSO incidences. Finally, Section “Conclusion and policy implications” concludes and presents policy implications.

The theoretical foundation of the economics of crime is discussed in this section. In conjunction with that, the major data sources and the concerned variables are described in this section. The econometric models, which are utilised to investigate the said objectives are also presented in this section.

Conceptual framework

According to Becker ( 1968 ), criminals possess different attitudes concerning costs and benefits and this difference in viewpoint is the principal imputes for them to commit a crime. These attitudinal differences motivate a person to commit a crime despite the likelihood of being arrested by police, convicted and to be imprisoned by the legal system. In this regard, the “Economic Theory of Crime” is based on the assumption that a person will devote his/her time and other resources to commit a crime/offence if the person believes that his/her expected utility by committing the crime exceeds the expected utility from other activity utilising the same time and resources. The theory can be formulated mathematically by using vonNeumann and Morgenstern ( 2007 ), expected utility function.

Ehrlich ( 1996 ) defines that a person may decide to divide his/her total working time between criminal activities ( \(b_{{\mathrm{crime}}}\) ) under uncertain conditions and legitimate activities ( \(b_{{\mathrm{legal}}}\) ) under certain conditions. The income generated from devoting specific time to legal activities is denoted by \(W\left( {b_{{\mathrm{legal}}}} \right)\) . On the contrary, the income generated from devoting specific time to illegal activities is denoted by \(W\left( {b_{{\mathrm{crime}}}} \right)\) depending on the probability of being arrested p and not arrested ( 1–p ). If the person involves in both legal and illegal activities simultaneously and he/she has an initial wealth \(W_{{\mathrm{Initial}}}\) , then the income obtained from both legal and illegal activities and not being apprehended is given by:

On the contrary, if the person is convicted and arrested he/she has to pay a penalty \(Y_2\) depending on whether he/she is devoted to the criminal activities \(Z_{{\mathrm{crime}}}\left( {b_{{\mathrm{crime}}}} \right)\) . Under such circumstances the income generated is:

The objective of the individual is to maximise his/her expected utility by dividing his/her entire time into legal and illegal activities. Thus, the expected utility can be presented by the following equation:

To determine the optimal time to be devoted for criminal activities ( \(b_{{\mathrm{crime}}}\) ) we determine the first-order-condition as follows:

where \(w_{{\mathrm{legal}}} = \frac{{dW_{{\mathrm{legal}}}}}{{db_{{\mathrm{crime}}}}}\) , \(w_{{\mathrm{crime}}} = \frac{{dW_{{\mathrm{crime}}}}}{{db_{{\mathrm{crime}}}}}\) , \(z_{{\mathrm{crime}}} = \frac{{dZ_{{\mathrm{crime}}}}}{{db_{{\mathrm{crime}}}}}\) and \(U^\prime (Y_i) = \frac{{dU\left( {Y_i} \right)}}{{db_{{\mathrm{crime}}}}}\forall i = {\mathrm{crime}},{\mathrm{legal}}\)

We assume that the concerned person is a risk averter and thus the person copes with both legal and illegal activities simultaneously. This implies equilibrium is ensured by the condition \(U^\prime \left( {Y_1} \right) = U^\prime \left( {Y_2} \right)\) given that equal wealth is generated from legal and illegal activities, that is, \(Y_1 = Y_2\) . Therefore the necessary condition to devote time to illegal activities is given by the equation:

Díez-Ticio and Brande´s ( 2001 ), mentioned the propensity of criminality can only be reduced in society through a reduction in economic inequality. The economic paradigm discloses two types of incentives for crime, viz., positive and negative (Domínguez et al., 2015 ). The negative incentives will demoralise and prevent criminals to commit a crime. On the contrary, positive incentives will encourage delinquents to choose legitimate alternatives (Ehrlich, 1973 ; Domínguez et al., 2015 ).

Stationarity checking

The stochastic process must be stationary for the reliability and validity of the result. The prediction and policy prescription based on the non-stationary stochastic process is not reliable. The checking of “ stationarity ” of the time series variable is the primal concern for the time series analysis. This is particularly because stationarity of the time series variable ensures universality of the estimated result as well as applicability of the variable for prediction and policy prescription. Two non-parametric tests, viz., “ Augmented Dicky Fuller Test (ADF)” and “ Phillips Perron Test (PP)” are available for this purpose. However, we will conclude about “ stationarity ” of the stochastic process based on the “ Phillips-Perron (PP)” test. As the test is more robust for testing heteroscedasticity in error variance (Phillips and Perron, 1988 ) and has greater powers than the “Augmented Dickey and Fuller (ADF)” test (Banerjee et al., 1993 ). Moreover, the test is free from the specification of the lag length, which is mandatory in the case of the ADF technique (Debnath and Roy, 2012 ).

Test equations in two cases are presented below.

Augmented Dicky Fuller Test:

Phillips Perron Test:

In both cases the hypothesis to be tested is \(H_0:\delta = 0\) and the corresponding test statistic is

Structural break and growth rate

The implication of the “ Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act ” (POCSO) (2012), for revamping children’s security in India can only be explored by considering structural breaks together with analysing the growth of POCSO incidences. The study period for the empirical analysis is from 2001 to 2019. As the natures of crimes against children have changed over time we have included only those crime heads, which are common during the entire study period as well as in POCSO Act (2012). This practice enables us to ensure uniformity of the data and allows us to conduct time series analysis. The selection of the study period is guided by the availability of data. The study period is susceptible to various policy changes for the “ Protection of Women and Child Rights ”. The “Ministry of Women and Child Development” has been administrating various special laws focusing on women and child protection. It is noteworthy that India is a signatory to the “ United Nations Convention on Right of Child (UNCRC) ” since 1992. In adherence to its commitment to ensuring child rights, the Government of India has framed different national policies to protect child rights from time to time, viz., “The Commissions for Protection of Child Right (CPCR) Act, 2005”, “The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006”, “The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012”, “Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act, 2015”. The Government of India has also framed the National Policy for Children, 2013 and the National Plan of Action, 2016 (Ministry of Women and Child Development, Press Information Bureau, 2019). Naturally one can expect to have structural breaks during this period. The existence of the structural break makes the normal time series analysis and growth rate calculation inapplicable. Consequently, the identification of the switching point is essential and an appropriate growth rate can only be obtained by calculating the same for different regimes as depicted by the switching points. The identification of the break or switching point should be facilitated by some statistical criterion, viz., “ Chow Test ” (Chow, 1960 ), “ CUSUM ” and “ CUSUMQ ” tests. As “ Chow Test ” is criticised for the arbitrariness problem, we have utilised the “CUSUMQ” test. Brown et al. ( 1975 ), introduces the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests for stability checking in parameter. Based on the scaled recursive residuals the break points are identified by the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests. The identification of the break points is also facilitated by the Chow ( 1960 ) tests. However, the greatest advantage of the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests is that these tests do not require prior knowledge of the point where the hypothesised structural switching points are expected to occur. The mathematical underpinning of the CUSUMQ test is as follows:

We consider a generalised linear regression model as

where x is a ( k × 1 ) vector with unit first element and ( k–1 ) are the observed value of the independent variables at time t . \(\beta _t\) is the ( k × 1 ) vectors of parameters. \(u_t\) is IID and \(u_t \sim N(0,\sigma ^2)\) . The recursive residuals are defined as:

where \(X_r = \left[ {x_1,x_2,....\,,x_r} \right]\) and \(y_r^\prime = \left[ {y_1,y_2,....\,,y_r} \right]\) and \(\hat \beta _{r - 1}\) is the vector of OLS estimates of the regression Eq. ( 9 )

The test statistic corresponding to CUSUMQ test is developed based on the recursive residuals are defined in (10). The corresponding test statistic is given as follows:

where \(\hat \sigma ^2 = \frac{{\mathop {\sum}\limits_{t = 1}^T {(y_t - x_t^\prime \hat \beta _r)^2} }}{{T - k}}\)

Under the null hypothesis that the parameters are constant, that is,

\(H_0:\beta _t = \beta\) with \(\sigma _t^2 = \sigma _t^2\) \(\forall t = 1,2,....\,,T\) Eq. ( 11 ) follows a distribution with parameters r – k and T – k . In the conventional CUSUMQ test we use symmetric error bands and the corresponding pairs of lines are given by \(\left[ { \pm critical\,value + \frac{{(r - k)}}{{(T - k)}}} \right]\) . The critical value is obtained from the Durbin ( 1969 ), table.

After the identification of the switching points, the growth rate will be calculated following the “ Poirier’s Spline function approach (Poirier & Garber, 1974 )”. Poirier’s Spline function approach (Poirier & Garber, 1974 ), helps us to determine the trend in the growth of the variable of interest in different regimes.

Assuming a linear time trend, the postulated model is presented as follows:

where, \(t_1\) is the switching point.

We next define following variables:

By reparameterisize we rewrite the function as follows:

For the i th (i = 1, 2) regime the growth rate in percentages will be obtained by using the following formula:

where \(\beta _1 = \gamma _1\) and \(\beta _2 = \gamma _1 + \gamma _2\) . The Eq. ( 15 ) helps in computing the growth rate for different regimes. Based on the change in economic policy or structure we may obtain more than one structural break point and accordingly, the corresponding model for analysing the growth rate will be modified. The growth rate for the entire study period will be computed by utilising the following equations:

Regression analysis

One of the objectives of the study is to explore the implications of the improvement in the “ quality of life ” and “ Judiciary and Public Safety Score (JPSS) ” in revamping children’s safety and security. This objective is explored based on the cross-sectional information of bigger Indian states’ on a list of relevant variables, including “PQLI” as one of the regressors. Another interesting regressor is the JPSS , which is used to portray the law and order condition of a state. This score is calculated using a number of indicators that reflect a state’s law and order situation (for more information, see Table 1 ). The selection of the sample period and the Indian states is strictly guided by data availability. The list of the regressors along with their definitions and data sources are presented in Table 1 . It is noteworthy that the regresand here is the rate of recorded POCSO cases. We didn’t pursue panel regression here because of the non-availability and decadal nature of data. The specified regression equation is:

where, x is a ( 1XK ) vector of regressor and \(\beta = (\beta _1,\beta _2,.....\,,\beta _K)^\prime\) is a ( KX1 ) vector. To incorporate an intercept term we will simply assume that \(x_1 \equiv 1\) , as this assumption makes interpreting the conditions easier (Wooldridge, 2016 ). y is a scalar. The equation-(17) can be estimated by using OLS method. The OLS estimators will be Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUE) iff all the “ Gauss-Markov ” assumptions are satisfied.

It is noteworthy that “ quality of life ” here is proxied by the “ Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI) ”. The index was developed based on Morris ( 1980 ) (see Tables 9 and 10 in the appendices for details). Thus, PQLI is calculated by using the following formula:

The regression analysis is conducted based on the latest available information of all concerned regressors as well as regressand (Bhaumik, 2015 ).

However, the regression analysis to explore the determining factors of POCSO incidences across Indian states will be meaningful if there is variation in the reported POCSO incidences. Thus, before conducting regression analysis, the appropriateness of such analysis is tested by performing non-parametric ANOVA.

The present study is entirely based on published secondary data. The major data sources are “ National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) ”, “ Census of India (2011) ”, “ Sample Registration System (SRS) ”, “ Central Statistics Office (CSO)” , “ Ministry of Human Resource Development ”, “ Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances, Government of India ” and “ National Sample Survey Office (NSSO).” The crime statistics in the present paper have mainly been compiled from NCRB for different years. It is noteworthy that concerning the “Incidents of sexual offences against children”, we have considered statistics related to the crime heads, which are common in the entire study period. As such, we have considered only those statistics related to child sexual abuse that are included later in the POCSO Act (2012). We did not include all crimes committed against children in this paper. By summing some specific crime heads, we have calculated “Incidents of sexual offences against children” for this paper to ensure uniformity in the data to facilitate the time series analysis. On the contrary, the empirical analysis of the second objective is facilitated by various regressors, including a composite index, the “Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI”),” which is compiled from various published sources. The composite scores of “ Judiciary and Public Safety Score ( JPSS )” reflecting the law and order condition of any state are obtained from the “ Good Governance Index, Assessment of State of Governance 2020–21 ” report. The detailed descriptions of the variables together with their sources are presented in Table 1 .

The variables utilised for delineating the PQLI are narrated in Table 9 in the appendices. It is noteworthy that the exploration of the first objective is executed by considering the “ total number of reported cases of sexual offences against children, viz., Rape (Section 376 IPC), Unnatural Offence (Section 377 IPC), Assault on Women (Girl Child) with Intent to Outrage her Modesty (section 354 IPC), Sexual Harassment (Section 354A IPC), etc .,” during the time period 2001 to 2019. To ensure uniformity of data we have considered selected crime heads, which are common to entire study period and also included in the POCSO Act (2012). The uniformity of crime heads authorises us to conduct time series analysis over the study period. Moreover, we have considered here “Incidents of sexual offences against children” for the time series analysis and not the rate to avoid further normalisation. The “Incidents of sexual offences against children” are calculated by summing different crime heads committed against children. These crime heads are common for the entire study period as well as also included in the POCSO Act (2012) (see Table 1 for more information). The choice of the sample period is dictated by data availability. On the contrary, pin-pointing the socio-economic determinants of the “ Rate of cases reported under POCSO ” is accomplished by considering the cross-sectional data across Indian states. Because of the cross-sectional data we have considered the “ Rate of cases reported under POCSO ” as regressor and not the actual incidences to facilitate cross-sectional analysis. The empirical analysis of the second objective is facilitated by the latest available information for the twenty bigger states in India (Bhaumik, 2015 ). The selection of the states and the sample period is purely based on the availability of relevant information on the concerned variables.

Results and Discussion

In this section, we will present the empirical results related to the objectives obtained by applying the said methodology and the possible reasons behind such empirical results.

Summary statistics Sexual Offences Against Children

Sexual offences against children (SOAC) have been a hidden problem in India and are largely ignored both in social discourse as well as by the criminal justice system. Table 2 presents the summary statistics of the sexual offences committed against children over the time period from 2001 to 2019.

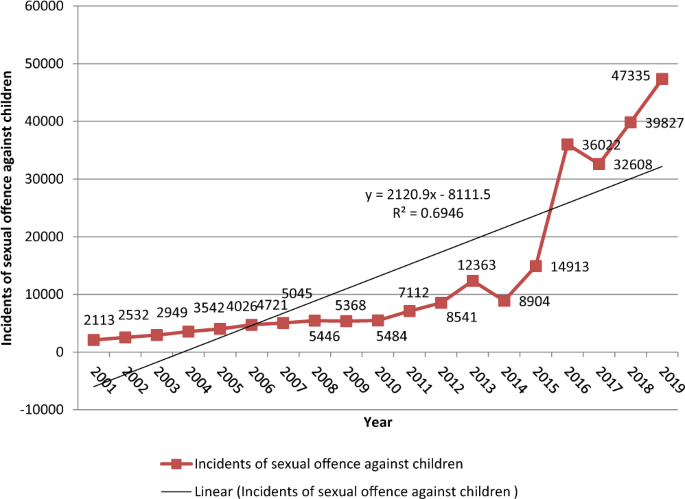

The table reveals that the mean incidence of SOAC is 13097.42 while the mean rate of the same is ~3%. Considering the huge population of India, this 3% figure is amounted to more than 13,000 incidences. The minimum incidence is a petrified figure (2113), and the corresponding maximum incidences are more than 47,000. As we are considering only the Indian scenario concerning SOAC, the impact of the POCSO act is analysed considering the “ Incidences of Sexual Offences against Children ”.

The incidences of sexual offences against children over the time period are also presented graphically in Fig. 1 .

Authors’ own presentation based on NCRB data.

The figure discloses a sharp increase up to 2013 and then, in 2014, it decreased marginally. In the next 2 years, India witnessed a sharp escalation of the incidences of sexual offences against children. In 2017, India witnessed a marginal decline in incidences. However, this decrease only lasts a year before the incidences rise again until 2019. The extreme fluctuations of the “ Incidences of Sexual Offences against Children ” indicating that there may be switching points in the study period and further investigation is required to understand the influence of different act legislated by the Indian government time-to-time for the protection of children.

Unit-root test

The stationarity of the time series is tested by using both the “Augmented Dickey and Fuller (ADF)” and the “Phillips-Perron (PP)” tests. However, to conclude about the stationarity of the stochastic process, we emphasise the “Phillips-Perron” test as it has greater power than the ADF test (Banerjee et al., 1993 ). The test result of the “ Incidents of sexual offences against children ” is presented in Table 3 .

The table reveals that we must accept the null hypothesis of unit root at the level. This means the variable is non-stationary and to make it stationary we consider the first difference of the variable. Further application of both tests on the first difference ensures the stationarity of the concerned variable. Therefore, for the analysis of the implication of the POCSO Act (2012), we must precede with a first difference as the differencing makes the stochastic process stationary. However, because of differencing, we lost one observation. Thus, the empirical investigation of the first objective will be executed by considering the “ Incidents of sexual offences against children ” for the time period 2002 to 2019. The apriori conditions for time series analysis, such as uniformity of statistical information and stationarity, are ensured, and thus we can proceed to structural break analysis.

Structural breaker switching points

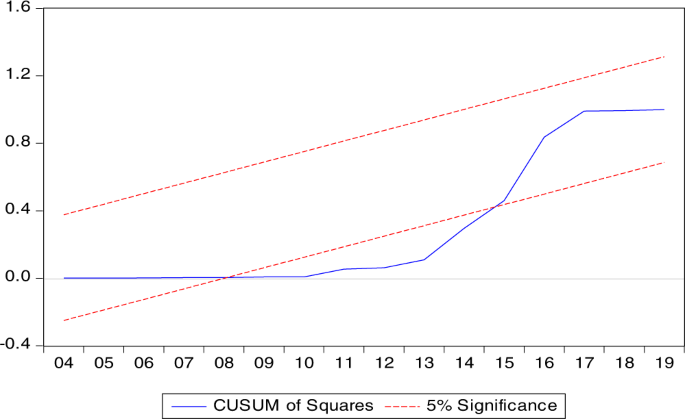

Figure 1 discloses that there are fluctuations in the incidences of sexual offences against children in India. Moreover, the results related to PP and ADF tests suggest that the stochastic process is non-stationary at the level. Figure 1 and Table 3 together provide evidence to suspect that there may be structural breaks in the series. The structural break appears when there is an unexpected shift in the series. The possible reasons for that may be a change in the policy or structure of the economy, etc. In the present paper, the identification of the switching point of the time series variable is facilitated by the application of the “CUSUM squares test (CUSUMQ)” because of its superiority over the “Chow test”. When the switching points are unknown, the “CUSUM squares test (CUSUMQ)” is thought to be the most suitable method for determining the same. Figure 2 presents the test result of the CUSUMQ test.

Authors’ own calculation based on NCRB data.

The CUSUMQ test result reveals that the series has two break points, viz., in 2008 and 2015 and the result is significant at a 5% level. These two switching points divide our entire study period into three regimes viz., Regime-I (2002 to 2008), Regime-II (2009 to 2015), and Regime-III (2016 to 2019). Therefore, based on the switching point as dictated by the CUSUMQ test, we have divided our study period into three regimes. The critical question is, why do such unexpected changes occur with SOAC cases? In search of this question, we came across that the “Ministry of Women and Child Development” has been administering various special laws relating to women and children, such as “The Commissions for Protection of Child Right (CPCR) Act, 2005”, “The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006”, and “The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012”. Any policy change to protect children from any form of sexual abuse will take time to become effective. Consequently, if any policy change materialises in some period of time, say, 2005–2006, its implications will be felt after 1 or 2 years. Therefore, the first break point we obtain may be because of the influence of “The Commissions for Protection of Child Right (CPCR) Act, 2005”, “The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006”, and because of “The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012”, the second switching point appears. This is because although the act was passed in the Indian parliament in 2012, the implementation of the act takes time and was executed fully from 2016 onwards. NCRB also provides POCSO statistics from 2016 only. Consequently, the implications of these acts on children’s protection can be analysed by calculating the growth rate of SOAC for different time regimes by satiating the switching points.

Growth rate of incidents of sexual offences against children in India

We now consider the exploration of our first objective—the implication of the POCSO act in controlling the incidences of sexual offences against children in India. Based on the CUSUMQ test, we have divided our entire study period into three regimes, viz., Regime-I (2002 to 2008), Regime-II (2009 to 2015), and Regime-III (2016 to 2019). The third regime will enable us to analyse the implication of the POCSO act in revamping children’s paradise in India. To investigate the objective, we separately estimate the growth rate of SOAC incidences during these three different regimes, and the empirical result is shown in Table 4 . The estimations of the growth rates for different regimes are derived from Poirier’s Spline function approach (Poirier & Garber, 1974 ).

The growth rate of SOAC in Regime-I (2002 to 2008) was 1.219, a positive but controlled figure. As mentioned earlier, the Regime-II (2009–2015) may be expected to reflect the impact of two laws, viz., “ The Commissions for Protection of Child Right (CPCR) Act, 2005 ” and “ The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 ”, that have been administrated by “The Ministry of Women and Child Development” in 2005 and 2006, respectively. Unfortunately, our empirical findings indicate that these two laws do not protect children from “sexual offences.” The growth rate of SOAC during Regime-II escalated to 4.681. This may be because perhaps these laws are not focused on giving protection to children from sexual abuse. The former one was addressing the protection of children’s rights and the focus of the latter one was to forbid child marriage. None of these acts focus on terminating the sexual abuse of a child . Consequently, none of the act becomes king pin for minimising the sexual abuse of a child. On the contrary, on May 22, 2012, the Parliament of India passed the “ Protection of Children against Sexual Offence Bill, 2011 ” concerning the sexual abuse of a child (Bajpai, 2018 ) and, based on that, the “ Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 ” was enacted. The act is centred on ensuring a strong legal framework for protecting children from sexual offences of any kind, including rape, sexual harassment, and pornography (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2013 ). Consequently, the “ POCSO Act, 2012 ”, becomes the first safeguard law for protecting children from sexual offences. The act was enacted in 2012, so we can expect the implication of this policy change to materialise from 2015 onwards. The NCRB provides recorded POCSO incidences, victims, and rates from 2016 onward. Therefore, we can expect the implication of the “ POCSO Act, 2012 ” to materialise in the Regime-III . Legitimately, the empirical result suggests that the “ POCSO Act, 2012 ” helps in reducing the sexual abuse of children . The growth rate of “ sexual offences against children ” in Regime-III declined to −4.611. Therefore, we can conclude that the “ POCSO Act, 2012 ” helps to reduce the sexual abuse of children and revamp children’s safety and security.

After exploring the implication of the “ POCSO Act, 2012 ”, in revamping children’s paradise, we next explore if there is any variation in reported POCSO incidences across Indian states or not. If variation exists, then only there organisation of the factors responsible for the successful implementation of the “ POCSO Act, 2012 ” across Indian states will be meaningful.

Variation in POCSO incidences across Indian states

To understand the variation in the “ Rate of cases reported under POCSO ” across Indian states, we performed a non-parametric ANOVA test considering 20 bigger Indian states for the time period 2016 to 2019. Table 5 presents the test result.

The table shows that the 1% threshold of statistical significance rejects the null hypothesis, H 0 : no inter-state variation , in the “Rate of instances reported under POCSO” across Indian states. The high F -statistic’s value of 19.417 demonstrates that there is considerable inter-state variation in the “Rate of instances reported under POCSO”. This result elucidates that there must be some determining factors for the inter-state variations. This test then authorised us to perform regression analysis in an attempt to identify the factors influencing the “ Rate of cases reported under POCSO ”.

Factors influencing the rate of reported POCSO cases

We next consider the pin-pointing of the role of PQLI along with other regressors in reducing reported POCSO cases for Indian states. The “ Ordinary Least Squares ” is our estimation technique, and thus the post-estimation of the validation of the OLS is also verified in this paper. The apriori condition for cross-sectional analysis, representative data, is primarily scrutinised by the descriptive statistics of the regression variables, which confirms the appropriateness of the regression analysis (see Table 11 in appendices). Table 6 presents the regression result.

A close perusal of the table divulges that the percentage of SC population, 0–19 Sex-ratio, Urbanisation, POCSO Percentage Share of Known Persons Cases to Total Cases, Secondary Gross Enrolment Ratio, PQLI, Judiciary and Public Safety Score (JPSS), and Employment relate male migration (Male migration) have a Significant footprint on the rate of reported POCSO cases . The regressors SC and ST are both positively related to POCSO . Historically, it is patently true that the lower castes, vis-à-vis weaker sections of society, are always as of target for any form of crime (Bower, 2003 ; Bywaters, et al., 2016 ; Sexton and Sobelson, 2018 ).

Here, we are also getting the reverberation of the paten fact. It is noteworthy that the estimated coefficient for ST is not statistically significant. The negative role of the JPSS demonstrates that enhancement in the law and order condition in the state results in the reduction of POCSO incidences. The result is pronounced. The improved law and order condition reflects the state’s efficacy in protecting its citizens. The state can provide a safe environment for normal daily life activities. Consequently, improvement in the JPSS fore shortens POCSO incidences in particular and crime as a whole. The absence of the implication of such an independent variable on POCSO cases in earlier studies prevents us from presenting any earlier study in support of our findings. The negative and significant value of the estimated coefficient 0–19 Sex-ratio enables us to pin-point that a favourable sex-ratio at any age will help to minimise any form of sexual offence.The favourable sex-ratio may give the voice less a voice and make it possible to recognise sexual offences, including sexual abuse of children (Kansal, 2016 ; Maity & Sinha, 2018 ; Maity, 2019 ). Based on our research, it is clear that most often it is a close family who abuses a child, the corresponding estimated coefficient, 0.438 is significant at 1% level. The well-established truth is confirmed by this finding. According to a research, the victims are familiar with 90% of the perpetrators (The Times of India, March 1, 2018 ; Maity, 2022 ). We draw two paradoxical results from our regression analysis, viz., an increase in both urbanisation and secondary gross enrolment ratio (elementary GER turns out statistically insignificant), and increase in the reported POCSO incidences. This may be because lower-class residents in urban regions frequently work in low-wage, ad hoc occupations. Even the primary female members need to work to pay the bills. Children become an easy target for any type of sexual assault when their parents are not present. Additionally, young kids are sometimes hired as domestic an assistant, which renders them more susceptible to this kind of crime. Education improves view points and gives the voice less a platform. The positive correlation between SGER and POCSO occurrences may be due to this. Here, we solely take into account recorded POCSO incidents. Because of their increased knowledge and awareness, the parents were eventually able to report the crime to the police after overcoming a variety of social stigmas, prejudices, and beliefs. The most interesting result is the relationship between POCSO-reported cases and PQLI. The estimated coefficient is not only statistically significant but also the sign of the coefficient is desirable. The estimated coefficient envisages a juxta position of the “ quality of life ” and “ reported POCSO cases ”. Consequently, the estimated coefficient allows us to conclude that by enhancing the “ quality of life ”, it is possible to deplete “ reported POCSO cases ” and revamp children’s paradise on earth. Finally, employment-related male migration is found to influence the reported POCSO cases positively. The result reflects the Indian societal structure where in the male is the undisputed leader of the family (Maity & Sinha, 2018 ; Maity, 2019 ). When the family’s main bread winner moves to another location, state, or country, the female members of the family become easy prey for others. Under such a scenario, the little one becomes more exposed to crime reported under POCSO. Only by speaking out against such crimes by other family members, including females, can such incidents be avoided. The absence of earlier literature concerning this prevents us from presenting any earlier study in support of our study. The table also presents the “ beta coefficient ”. A perusal of “ standardised coefficients ” discloses the paramount factor for reducing “ reported POCSO cases” Is the “quality of life” , followed by “ JPSS ” and a favourable “0 – 19 Sex-ratio ”. On the contrary, the “ standardised coefficients “reveal that “ POCSO known person ” and “ urbanisation ” is the most important factor in enhancing “ reported POCSO cases ”. The possible reasons for such results are explained earlier.

The testaments of the five basic assumptions which are necessary for the OLS estimators to be BLUE are examined thereafter.

The “ Adjusted Coefficient of Determination ”, \(\bar R^2\) is a measure of “ goodness of fit ” in a multiple regression model. The rule of thumb is higher the value better the fit. In the present model, \(\bar R^2\) is 0.8664, means best fit. The model is also well-specified, with a high F -statistic of 6.67 and a Prob > F of 0.0062.

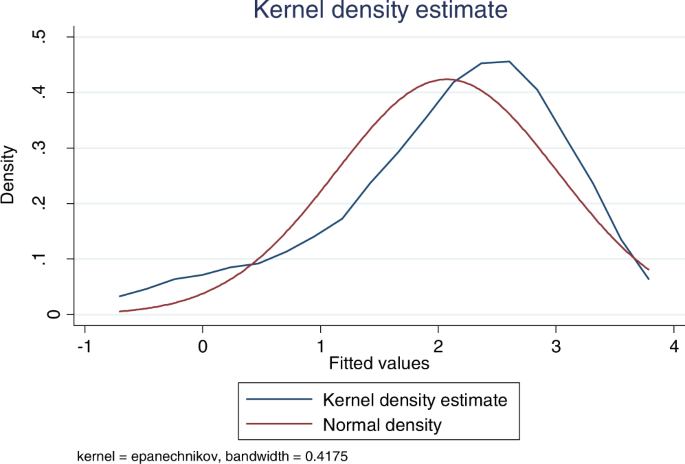

The normality of the error term is the primary condition for the OLS estimators to be BLUE. Graphical and statistical verification of the normality of the error term is performed here. For statistical verification of normality, we have used the “Shapiro–Wilk W -test for normal data.” The results are depicted graphically in Figure 3 and statistically in Table 7 .

Authors’ own calculation.

The null hypothesis of the test is that the corresponding distribution is normal. As disclosed in Table 7 , the large p -value (0.11) indicates the acceptance of \(\hat u_i\) is normally distributed. Thus, the normality of the residuals is established.

Heteroskedasticity

Based on the cross-sectional information, an empirical inspection of the determinants of the rate of reported POCSO cases across Indian states is performed. Accordingly, non-constancy of the error variance is a common phenomenon. To ensure homoscedasticity of the error variance, we conduct the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity and Cameron and Trivedi’s decomposition of the IM-test. Here,

\(H_0\) : Constant Variance ,

The test results are presented in Table 7 ensures constancy of error variance or homoscedaticity .

Multicollinearity

Only in the absence of multicollinearity can independent effects of the regressors on the regressand be obtained. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of the regression helps us to confirm the absence of multicollinearity. The corresponding result is presented in Table 8 .

Both VIF and the tolerance (1/VIF) are to be checked for the confirmation of the absence of multicollinearity. The table shows that for all regressors, the VIF and the tolerance (1/VIF) are within the prescribed level and thus corroborates the absence of multicollinearity .

Consequently, the OLS estimators presented in Table 6 are BLUE, and the conclusions drawn from these estimators are universal.

Conclusion and policy implications

The present study pivot around two research questions, viz., firstly, does the “ Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act” (PCSO) (2012), contribute to reducing “ sexual abuse of children ” in India? Secondly, does the escalation of “ Quality of life ” also entail a reduction of “sexual abuse of children”? Our empirical findings authorise us to conclude affirmatively in both cases. Based on our empirical findings we can suggest the following policy prescriptions to fore shorten “ child sexual abuse ” in India.

Firstly , improvement of “ quality of life ” will benefit everyone in society and that is the rudimentary reason for the negative sign. Improvement of the “ quality of life ” also ensures child protection together with the up-gradation of human capital. This yields in the enhancement of socio-economic conditions and that results in enhancing the safety and security of all. Therefore, both the state and the central governments must focus to improve the “ quality of life ” of their citizens. Secondly , the positive sign of the estimated coefficient of the “ secondary gross enrolment ratio ” encourages us to prescribe that emphasis should be placed on the enrolment of children in schools and encourage them for continuing education. Education will empower them, equip them to recognise “ good and bad touch ”, give them to voice against any “kind of sexual offence” without fear, and ultimately empower them to break “ irrational social stigma ”. In fact, only education empowers them to recognise and protest when they are the victims of “ sexual abuse ” by the “ known person ” Hence, only by encouraging parents to enrolment and continue of education of their children, including girl children, it is possible to fore shorten “ reported POCSO cases ” one day. Thirdly , recognising that lower cast people are soft targets of crime including “ child sexual abuse ”, a special provision in the law is demanded to protect these people. In fact, the “Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989”,is there to protect SC and ST people. However, the mere existence of such acts does not guarantee the protection of SC and ST people. Only detecting and punishing such offences on a fast-track basis can foreshorten such crimes. The concentration of power among the high-caste people is one of the sources of such crimes. The distribution of powers, especially political power may furnish some solution. Identifying this, the Government of India reserved certain numbers of political positions for specific groups of the population including “ Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes ”. However, without changing the mentality of people, it is not possible to stop these cast-based crimes. Fourthly , the scenario of law and order condition of any state is proxied by the “Judiciary and Public Safety Score”. A higher value of JPSS indicates improved law and order conditions in any state. This means greater protection for all. By improving law and order conditions the concerned state will be able to provide an appropriate environment for social and economic activities. Accordingly, irrespective of the JPSS status Indian states are recommended to improve their law-and-order conditions. Finally , recognising the positive correlation between “ reported POCSO cases ” and “ urbanisation ” it is patently true that “child protection” is an emergent issue in urban India. In this respect, the local-state-central governments need to work in one line appropriately.

In the present study the pin-pointing of the determinants of the “reported POCSO act” is conducted by considering cross-sectional data. However, such a study can be better understood by considering panel data. Unfortunately, because of the unavailability of such statistics, we cannot pursue this. This can be considered a limitation of the study. However, based on the availability of the data, this extension is a future plan.

Data availability

The present study is based on secondary data. All relevant data are available at free of cost. The data sources are mentioned in the text.

TimesofIndia,15/04/2018

Ali S (2019) Death penalty in POCSO Act imperils child victims of sexual offences. Retrieve from: https://www.indiaspend.com/death-penalty-in-pocso-act-may-imperil-child-victims-of-sexual-offences/ . Accessed 14 May 2020

Bajpai A (2018) Child rights in India: Law, policy, and practice. Oxford University Press

Banerjee A, Dolado J, Galbraith JH, Hendry DF (1993). Co-integration, error-correction, and the econometric analysis of non-stationary data: advanced texts in econometrics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T (2013) The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Pub Health 58(3):469–483

Article CAS Google Scholar

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76(2):169–217

Article Google Scholar

Behere PB, Mulmule AN (2013) Sexual abuse in 8-year-old child: Where do we stand legally? Indian J Psychol Med 35(2):203–205

Bhaumik SK (2015) Principles of econometrics: a modern approach using eviews. OUP Catalogue

Books SW (2016) Regression with Stata. Chapter 2-Regression Diagnostics. UCLA: Academic Technology Services, Statistical Consulting Group. Retrieve from: https://www.coursehero.com Accessed 11 Aug 2016

Bower C (2003) The relationship between child abuse and poverty. Agenda 17(56):84–87

Google Scholar

Brown RL, Durbin J, Evans JM (1975) Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relationships over time. J Royal Stat Soc: Series B (Methodological) 37(2):149–163

MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Bywaters P, Bunting L, Davidson G, Hanratty J, Mason W, McCartan C, Steils N (2016) The relationship between poverty, child abuse and neglect: an evidence review. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York

Chahine EF (2014) Child abuse and its relation to quality of life of male and female children. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 159:161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.350

Chandramouli C, General R (2011) Census of India. Rural urban distribution of population, provisional population total. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, New Delhi, India

Children in India-Statistical Information (2022) Retrieve from: https://toybank.in/children-in-india-statistical-information . Accessed 05 Jul 2022

Chiu GR, Lutfey KE, Litman HJ, Link CL, Hall SA, McKinlay JB (2013) Prevalence and overlap of childhood and adult physical, sexual, and emotional abuse: a descriptive analysis of results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Violence Vict 28(3):381–402

Chow GC (1960) Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econ: J Econ Soc 28(3):591–605

Chowdhuri S, Mukhopadhayay P (2016) A study of the socio-demographic profile of the persons accused under POCSO act 2012. Int J Health Res Med Leg Pract 2:50–55

Collin-Vézina D, Daigneault I, Hébert M (2013) Lessons learned from child sexual abuse research: Prevalence, outcomes, and preventive strategies. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 7(1):1–9

Crime in Indian (2018) Statistics, Volume-I. National Crime Record Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. Government of India, New Delhi. Retrieve from: https://ncrb.gov.in/

Crime in Indian (2019) National Crime Record Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. Government of India, New Delhi. Retrieve from: https://ncrb.gov.in/

Crime in Indian (2021) National Crime Record Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. Government of India, New Delhi. Retrieve from: https://ncrb.gov.in/

Debnath A, Roy N (2012) Structural Change and Inter-sectoral Linkages. Econ Polit Week 47(6):73

Díez-Ticio A, Brande´s E (2001) Delincuencia y accio´n policial. Un enfoque econo´mico. Revista Economı´a Aplicada 9(27):5–33

Domínguez JP, Sánchez IMG, Domínguez LR (2015) Relationship between police efficiency and crime rate: a worldwide approach. Eur J Law Econ 39(1):203–223

Downing NR, Akinlotan M, Thornhill CW (2021) The impact of childhood sexual abuse and adverse childhood experiences on adult health related quality of life. Child Abuse Neglect 120:105181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105181

Durbin J (1969) Tests for serial correlation in regression analysis based on the periodogram of least-squares residuals. Biometrika 56(1):1–15

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Ehrlich I (1996) Crime, punishment, and the market for offenses. J Econ Perspect 10(1):43–67

Ehrlich I (1973) Participation in illegitimate activities: A theoretical and empirical investigation. J Pol Econ 81(3):521–565

Fraser JA, Mathews B, Walsh K, Chen L, Dunne M (2010) Factors influencing child abuse and neglect recognition and reporting by nurses: a multivariate analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 47(2):146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.015

Haque MA, Janson S, Moniruzzaman S, Rahman AKM, Islam SS, Mashreky SR, Eriksson UB (2019) Child maltreatment portrayed in Bangladeshi newspapers. Child Abuse Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2606 . https://indianexpress.com/article/india/crime-against-kids-a-third-still-under-pocso-8119689/ https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/7-pocso-cases-every-month-90-of-accused-known-to-child/articleshow/63118909.cms

Kanpur UP (2020) The Tribune, November 17. 6-year-old girl found dead in Kanpur was gang-raped; heart, lungs taken out to perform black magic

Kansal I (2016) Child sexual abuse in india: socio-legal issues. Int J Sci Res Sci Technol 2(2):1–4

Kartik KK (2020) The New Indian Express, January, 31. Number of POCSO cases in Karnataka moved up in 2019

Krishnakumar P, Satheesan K, Geeta MG, Sureshkumar K (2014) Prevalence and spectrum of sexual abuse among adolescents in Kerala, South India. Indian J Pediatr 81(8):770–774

Kshirsagar J (2020) POSCO-an effective act of the era. Supremo Amicus 18:428

Maity S (2019) Performance of controlling rape in India: efficiency estimates across states. J Int Women’s Stud 20(7):180–204

Maity S (2022) Escalation of police efficiency diminishes POCSO incidences—myth or reality? Evidence from Indian states. Int J Child Maltreat Res Policy Pract 5(1):155–180

Maity S, Sinha A (2018) Interstate disparity in the performance of controlling crime against women in India: efficiency estimate across states. Int J Educ Econ Dev 9(1):57–79

Miller KL, Dove MK, Miller SM (2007) A counselor’s guide to child sexual abuse: Prevention, reporting and treatment strategies. In: Paper based on a program presented at the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision Conference, Columbus, OH

Ministry of Women and Child Development (2013) Model Guidelines under Section 39 of The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012. Retrieve from: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/POCSO-ModelGuidelines.pdf . Accessed 12 Feb 2020

Moirangthem S, Kumar NC, Math SB (2015) Child sexual abuse: Issues & concerns. Indian J Med Res 142(1):1

Morris MD (1978) A physical quality of life index. Urban Ecol 3(3):225–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4009(78)90015-3

Morris MD (1980) The Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI). Dev Digest 18(1):95

CAS Google Scholar

Pallathadka H, Kumar S, Kumar V (2021) A socio-legal analysis of child sexual abuse in India. Des Eng 2021(9):1768–1775

Phillips PC, Perron P (1988) Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 75(2):335–346

Poirier DJ, Garber SG (1974) The determinants of aerospace profit rates 1951–1971. South Econ J 41:228–238

Rubin ML, Thelen MH (1996) Factors influencing believing and blaming in reports of child sexual abuse: Survey of a community sample. J Child Sex Abuse 5(2):81–100. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v05n02_05

Scroll Staff (2020) The Indian Express, August 26. Uttar Pradesh: 17-year-old girl raped, murdered in Lakhimpur Kheri; no arrests so far

Sexton DL Jr., Sobelson B (2018) Examining the connection between poverty and child maltreatment and neglect. September 10, 2018. Retrieve from: https://militaryfamilieslearningnetwork.org . Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Soondas A (2018) The Times of India, April, 15. Kathua rape case: ‘Not just me, the nation lost a daughter’. Retrieve from: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com . Accessed 25 Jun 2018

Staff Reporter, New Delhi (2018) 7 POCSO cases every month, 90% of accused known to child Retrieve from: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/63118909.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst . Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Tamilarasi B, Kanimozhi M, Kumari J (2020) Effectiveness of planned teaching programme on knowledge regarding pocso act among school teachers. TNNMC J Med Surg Nurs 8(1):36–39

UNICEF (2022) Retrieve from: https://www.unicef.org/protection/sexual-violence-against-children . Accessed 28 Jun 2022

vonNeumann J, Morgenstern O (2007) Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton University Press

Wihbey J (2011) Global prevalence of child sexual abuse. Journal Resour 15(4):25–30

Wooldridge JM (2016) Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Nelson Education

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal, India

Shrabanti Maity

Department of French, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India

Pronobesh Ranjan Chakraborty

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SM, conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript; PRC, helped to draft and revised the manuscript. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shrabanti Maity .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tables 9 , 10 , 11

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maity, S., Chakraborty, P.R. Implications of the POCSO Act and determinants of child sexual abuse in India: insights at the state level. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 6 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01469-x

Download citation

Received : 30 March 2022

Accepted : 29 November 2022

Published : 03 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01469-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

PolicyBristol

Seen but not heard: addressing the silent epidemic of child maltreatment in india.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 calls for a reduction in exposure or experience of any form of child abuse and neglect., particularly in children from lower- and middle income countries. The term ‘child maltreatment’ encompasses physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse, and physical and emotional neglect.

India has the largest population of children in the world (over 200 million) and data from UNICEF shows that Indian children are disadvantaged in their rights, access to education and healthcare, and are often exposed to physical labour and early marriages. A third of all child brides in the world are from India.

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012 is the only active child protection legislation in India specific to sexual abuse. However, its implementation has been poor, with delays in prosecutions due to the overburdened nature of courts and stigmatization of reporting child abuse.

This systematic review is the first of its kind, examining the evidence of all types of abuse and neglect in Indian children to determine how common child maltreatment is, and identify any differences by sex, population density, and legislation.

We identify specific risk factors and assess the effectiveness of the current legislation at tackling abuse and neglect.

Half of the girls interviewed from the largest study 4 of over 12,000 children wished they were born as boys.

Policy recommendations

Government of india.

• Current nationwide legislation is ineffective at countering specific cultural practices, such as child marriage, particularly in states with rural and tribal populations. Prioritise state-specific legislation.

• Prioritise policies and safeguards for those children most at risk: homeless or orphaned children, girls from rural or tribal regions and girls living in poverty or within urban slums.

• Create better social welfare frameworks for both home and school environments in which better safeguarding measures are put into place to identify vulnerable children or those who have had an experience of maltreatment.

• Implement and enforce the ban on corporal punishment across all Indian states.

Ministry of Women & Child Development

• Target policy and research funding to end corporal punishment as a normative cultural practice, such as focusing interventions on positive disciplining methods within homes and schools.

• Encourage behavioural change in parents/caregivers (positive parenting), helping to protect children from maltreatment at home.

• Prioritise measures that empower children with knowledge of their rights and builds core life skills (e.g. resilience and de-stigmatisation) in schools

• Raise awareness of all safe, accessible, and available channels to report abuse and neglect for children of all ages.

'Parents are the most common perpetrators of violence against girls'

– Rose-Clarke et al., 2019. 6

Research findings

The systematic review 1,2 consisted of evaluating 21 relevant studies published between 2005 and 2020 to determine the extent of child maltreatment, and any effects by sex, population density, population groups and POCSO implementation.

Twenty quantitative studies were state-specific, and one was nationwide. The studies included were based on self-report, child-report and assessment of child maltreatment by teachers or health professionals.

We excluded any study based on retrospective recall of maltreatment. Therefore, this review could be considered a snapshot of the time during which the studies were conducted.

This work builds on an earlier systematic review of child sexual abuse in India 3 providing more detailed findings about all types of abuse and neglect over a 15 year period and the specific impacts of these on children by their sex, where they live, and housing and family status.

• We estimate that up to 74% of Indian children report physical abuse; up to 72% report emotional abuse and up to 69% report sexual abuse.

• Up to 71% of Indian children report overall neglect, up to 60% report emotional neglect and up to 58% report physical neglect.

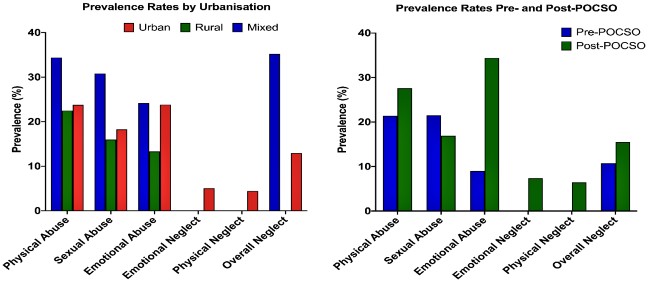

• Physical, sexual and emotional abuse and overall neglect is higher in rural and urban slum settings compared to urban settings.

• Children in socioeconomically advantaged households are four-times more vulnerable to physical violence compared with disadvantaged households. This is associated with academic achievements and expectations.

• Homeless children and orphans or runaways living in observation homes, particularly boys, are at increased risk of physical abuse.

• Girls who live in rural or tribal regions, urban slums, or socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, are at increased risk of child pregnancy and more likely to have restricted access to food, health services and education.

• Within tribal populations, almost 70% of girls report a pregnancy during childhood (under the age of 18 years).

• In addition to being at higher risk of many types of abuse and neglect, the studies reveal a common theme for girls: the futility of reporting maltreatment, as girls were often ignored, judged as being ‘at fault’, and not provided with any protection from perpetrators.

’Grandparents sent this girl to the observation home and her brother stays with them as they are taking care of her brother because he is a boy and they have left her, to live in an observation home because she is a girl’

– Kacker et al., 2007. 4

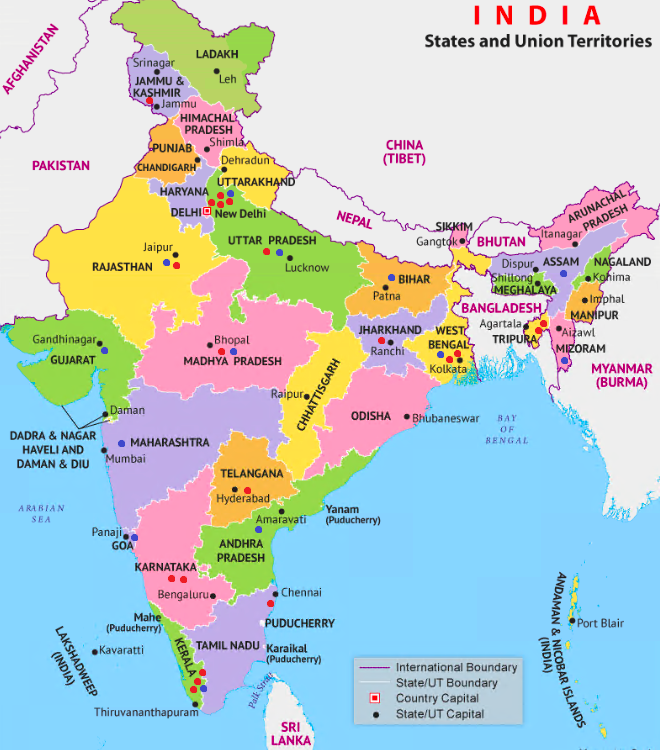

Red: locations of individual-site studies Blue: locations of the nationwide study by the Ministry of Women and Child Development

Taken from Figure 2. ‘Map of Indian states and union territories with red color showing the locations of studies selected for this systematic review and blue color showing the locations of Kacker’s nationwide study locations’, The prevalence of child maltreatment in India: a systematic review and narrative synthesis, Fernandes et al., 2021.

The effect of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012

Reported physical and emotional abuse and all types of neglect were higher after 2012 (post-POSCO implementation) but not for sexual abuse. However, our review found that abuse and neglect often occur in tandem, rather than in isolation, though sexual abuse is often least reported of all types of child maltreatment.

This is attributed to the stigma associated with reporting child sexual abuse; the draconian punishment, the daunting procedures involved (in terms of time, resources and money) mean that parents and carers are less likely to pursue legal redress.

There is also a lack of multi-agency, collaborative, approaches to tackling child maltreatment (healthcare, legislation, social services, research).

We found emotional and physical neglect were only evaluated in studies conducted after 2012. The improved clarity around definitions of abuse and neglect and improved study design (e.g. robust and generalisable sample size) and methodologies may explain these findings.

’The fallout from eve-teasing include restrictions on a girl’s movements, ending her education, questioning her sexual purity and bringing forward her marriage’

– Beattie et al., 2019. 5

Figure 2 Prevalence percentages of different forms of child maltreatmentmeans (%) by urbanisation

Prevalence percentages of different forms of child maltreatmentmeans (%) pre- and post POCSO

• Studies within mixed populations, i.e. including vulnerable children from both rural and urban slum settings, reported higher rates of physical, sexual and emotional abuse. Overall, neglect was also higher in mixed populations.

• Introducing child sexual abuse legislation in 2012 corresponds with an increase in overall reporting and evaluation of neglect and abuse.

Examples of good practice

ARPAN, a Mumbai based non-governmental organisation whose Personal Safety Education Programme aims to build core life skills in children between the ages of 5 and 16 years including interpersonal relationships, resilience, selfawareness and gender-awareness. The programme further provides counselling support for children and their families at schools following a disclosure of maltreatment. www.arpan.org.in

TULIR, a Chennai based non-governmental organisation that provides a personal safety education combined with therapeutic and socio-legal support to families and children with experience of maltreatment. www.tulir.org

The Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation use a holistic approach to address pressing issues of children such as child labour, child trafficking, child marriage, child sexual abuse, education, health & nutrition and livelihood for parents. www.satyarthi.org.in

The Trafficking in Persons (Prevention, Care & Rehabilitation) Bill 2021 This bill aims to create a dedicated institutional mechanism at district, state and national level to prevent and counter trafficking practices, and to further dedicate resources to the protection and rehabilitation of victims. It also covers all aspects of human trafficking, such as sexual oppression, enslaved labour, slavery and organ smuggling.

'Over 80% of child domestic workers are girls under the age of 18 years, and over 80% of children working in tea shops and restaurants are boys under the age of 18 years. Almost 70% of child domestic workers have experienced physical abuse.'

Research next steps

The study team are mapping the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child maltreatment experiences in Indian children.

Further information

1. The prevalence of child sexual abuse and associated adverse childhood experiences in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. PROSPERO. www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=150403

2. Fernandes, GS, Fernandes, MK, Vaidya, N, DeSouza, PE, Holla, B, Sharma, E, Plotnikova, E, Geddes, R, Benegal, V., Choudhry, V., 2021. The prevalence of child maltreatment in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. In press

3. Choudhry, V., Dayal, R., Pillai, D., Kalokhe, A. S., Beier, K. & Patel, V. 2018. Child sexual abuse in India: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13, e0205086. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205086

4. Kacker L, Vardan S, Kumar P, 2007. Study on Child Abuse: Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/study-child-abuse-india-2007

5. Beattie, T. S., Prakash, R., Mazzuca, A., Kelly, L., Javalkar, P., Raghavendra, T., Ramanaik, S., Collumbien, M., Moses, S., Heise, L., Isac, S. & Watts, C. 2019. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among 13-14 year old adolescent girls in North Karnataka, South India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 19, 48. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6355-z

6. Rose-Clarke, K., Pradhan, H., Rath, S., Rath, S., Samal, S., Gagrai, S., Nair, N., Tripathy, P. & Prost, A. 2019. Adolescent girls’ health, nutrition and wellbeing in rural eastern India: a descriptive, cross-sectional community-based study. BMC Public Health, 19, 673. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7053-1

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the study co-authors Miss Nilakshi Vaidya (NIMHANS, India), Dr Phillip De Souza (Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, United Kingdom), Dr Evgeniya Plotnikova (University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom), Professor Rosemary Geddes (University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom) and to Mrs Sarah Harding (University of Bristol).

Dr Gwen Fernandes (University of Bristol), Dr Megan Fernandes (Norwich and Norfolk University Hospital), United Kingdom Dr Vikas Choudhry (International Planned Parenthood Federation), Professor Vivek Benegal (NIMHANS), India

Policy Report 66: Oct 2021

Addressing the silent epidemic of child maltreatment in India (PDF, 476kB)

Contact the researchers

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Child sexual abuse in India: A systematic review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Public Health Foundation of India, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, India, Sambodhi Research and Communications Pvt. Ltd., Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Public Health Foundation of India, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, India

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Department of Global Health, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, Luisenstraße, Berlin, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Public Health Foundation of India, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, India, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States of America

- Vikas Choudhry,

- Radhika Dayal,

- Divya Pillai,

- Ameeta S. Kalokhe,

- Klaus Beier,

- Vikram Patel

- Published: October 9, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205086

- Reader Comments