- Bihar Board

SRM University

Ap inter results.

- AP Board Results 2024

- UP Board Result 2024

- CBSE Board Result 2024

- MP Board Result 2024

- Rajasthan Board Result 2024

- Shiv Khera Special

- Education News

- Web Stories

- Current Affairs

- नए भारत का नया उत्तर प्रदेश

- School & Boards

- College Admission

- Govt Jobs Alert & Prep

- GK & Aptitude

- general knowledge

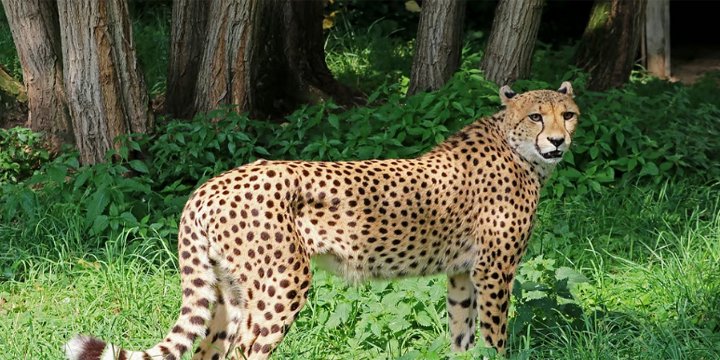

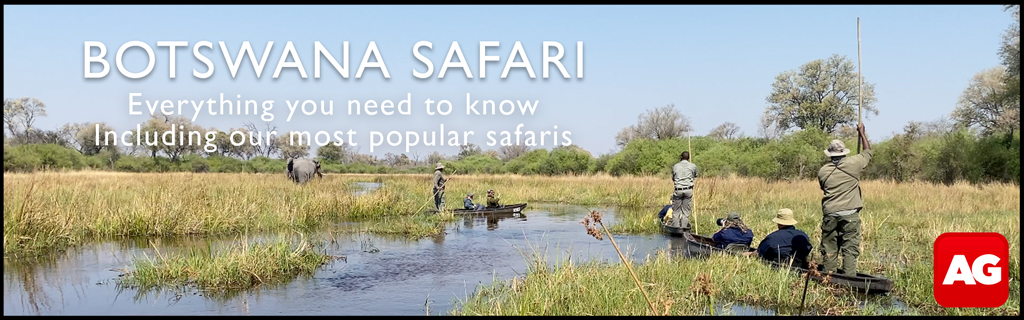

What is Project Cheetah? Who is behind it, Advantages, Challenges & more

Project cheetah is an initiative by the government to restore the extinct back in the indian woods. popular as the world’s first inter-continental large wild carnivore translocation project, the movement will revitalize the wildlife. read the article to know all about project cheetah, who is behind it, its advantages, challenges, and more.

What is Project Cheetah?

ये दुर्भाग्य रहा कि हमने 1952 में चीतों को देश से विलुप्त तो घोषित कर दिया, लेकिन उनके पुनर्वास के लिए दशकों तक कोई सार्थक प्रयास नहीं हुआ। आज आजादी के अमृतकाल में अब देश नई ऊर्जा के साथ चीतों के पुनर्वास के लिए जुट गया है: PM @narendramodi — PMO India (@PMOIndia) September 17, 2022

The Prime Minister making the historic move released Cheetahs at two different points in Kuno National Park. This initiative was part of a long series of measures to maintain sustainability and environmental protection in the last eight years.

What are the advantages of introducing ‘Cheetahs’ back to the Indian forest?

The release of wild Cheetahs in Kuno National Park is part of a movement to revitalize and diversify India’s wildlife and habitat. The spotted cat will help to conserve biodiversity and enhance the ecosystem services like water security, carbon sequestration, and soil moisture conservation, resulting in various benefits for human existence.

What are the common challenges for Project Cheetah?

Climate change is quoted as one of the main reasons for the extinction of Cheetahs. The worldly appraised movement to bring back is surrounded by various challenges. The major threat to the survival of Cheetahs is competition with similar size predators and humans.

According to experts from Africa, leopards are known to attack adult cheetahs whereas the cheetah cubs turn to prey for spotted hyenas. And Kuno National Park is home to 9 leopards per 100 sq kilometers.

Thinking of all these events, the government has ensured different measures for the safety and security of spotted cats. Along with forest officials, two elephants Lakshmi and Siddhnath are brought from Satpura Tiger Reserve for the protection of African Cheetah.

Following this, a group of students and villagers are also organized to sensitize people about Cheetahs, popularly known as ‘CheetahMitra’.

Get here current GK and GK quiz questions in English and Hindi for India , World, Sports and Competitive exam preparation. Download the Jagran Josh Current Affairs App .

- What is Project Cheetah? + 'Project Cheetah' is world's first inter-continental large wild carnivore translocation project.

- Who killed the last Indian Cheetah? + IFS Parveen Kaswan says that the King of Koriya hunted 3 cheetahs from the last lot of Indian cheetahs.

- Who released the cheetah in Kuno National Park? + The Indian prime minister released the cheetahs in Kuno National Park.

- Are cheetahs friendly? + Cheetahs are not an active threat to humans, also the spotted cat is less violent in terms of other existing members of the same family

- IPL Schedule 2024

- Surya Grahan 2024

- Most 100 Hundred in IPL

- Fastest 100 in IPL

- IPL 2024 Points Table

- Navratri Colours 2024

- Solar Eclipse of April 8 2024

- April Important Days 2024

- World Health Day 2024 Theme

- World Health Day Quotes

Latest Education News

UPPSC Agriculture Officer Recruitment 2024: यूपी एग्रीकल्चर ऑफिसर परीक्षा के लिए शार्ट नोटिस जारी

Google Tests "Lookup" Button for Unknown Callers: Know What it is

Today’s School Assembly Headlines (9 April): Total Solar Eclipse 2024, Right Against Climate Change, Heat Wave Alert in India and Other News in English

ISRO URSC Admit Card 2024 Released at isro.gov.in, Check Download Link

MUHS Result 2024 OUT at muhs.ac.in; Direct Link to Download UG and PG Marksheet PDF

Surya Grahan 2024: अपने मोबाइल पर देखें साल के पहले सूर्यग्रहण की LIVE स्ट्रीमिंग, डायरेक्ट लिंक यहां देखें

IIM Bangalore holds 49th Convocation Ceremony; award degrees to 706 students

IPL Orange Cap 2024: दिलचस्प हो गयी है ऑरेंज कैप की रेस, ये युवा बल्लेबाज रेस में है शामिल

IPL Points Table 2024: आईपीएल 2024 अपडेटेड पॉइंट टेबल यहां देखें

CUET PG 2024 Answer Key OUT LIVE: NTA Releases Provisional Answer Keys and Response Sheets, Check Latest Updates

Optical Illusion: Find the hidden frog in the picture in 8 seconds!

NDA Admit Card 2024 Live Updates: UPSC NDA 1 Hall Ticket Download Link on upsc.gov.in Soon

SSC Revised Exam Dates 2024 for JE, Selection Post 12, CPO and CHSL Released at ssc.gov.in, Check New Schedule Here

Purple Cap in IPL 2024: इन पांच गेंदबाजों में है पर्पल कैप की रेस, कौन निकलेगा सबसे आगे?

RGPV Diploma Results 2024 OUT on rgpvdiploma.in; Direct Link to Download All Semester Marksheet PDF

ISRO URSC Admit Card 2024 OUT: जारी हुआ इसरो यूआरएससी परीक्षा का हॉल टिकट, cdn.digialm.com से करें डाउनलोड

JEE Main Session 2 Question Paper 2024 Memory Based: Check Question Paper with Solutions April 8

JEE Main Analysis 2024 (April 8) Shift 1, 2: Check Subject-Wise Paper Analysis, Difficulty Level, Questions Asked

SSC Exam Calendar 2024 Revised for JE, CHSL, Phase 12 & More, Download New Schedule PDF

GK Quiz on Winners of IPL: Who Ruled the Tournament Each Year?

- International

- Today’s Paper

- Premium Stories

- Express Shorts

- Health & Wellness

- Board Exam Results

One year of Project Cheetah: Hits, misses and paradigm shift ahead

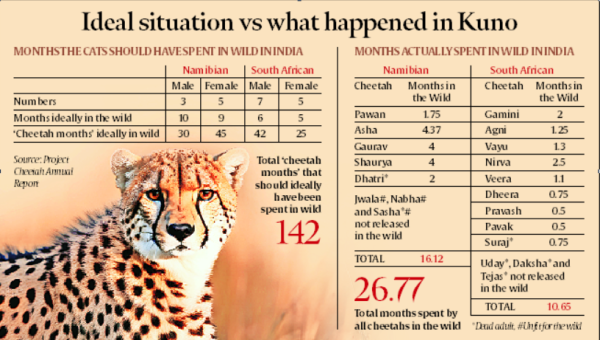

Twelve months since they arrived in india in september 2022, each of the three namibian males should have spent 10 months in the wild, and each of the five namibian females should have spent nine months in the wild..

A year after it was launched, Project Cheetah , India’s ambitious attempt to introduce African cats in the wild in the country, has claimed to have achieved short-term success on four counts: “50% survival of introduced cheetahs, establishment of home ranges, birth of cubs in Kuno”, and revenue generation for local communities.

The claims assessed

SURVIVAL: The test of survival is in the wild, not in captivity where animals are under protective care. According to India’s official Cheetah Action Plan, the male and female cats from both Namibia and South Africa were to spend two and three months respectively inside bomas (enclosures) before being released in the wild.

Therefore, in the 12 months since they arrived in India in September 2022, each of the three Namibian males should have spent 10 months in the wild, and each of the five Namibian females should have spent nine months in the wild. In all then, the eight cheetah imports from Namibia should have spent a cumulative 75 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

However, in reality, they spent just about 16 ‘cheetah months’ outside the bomas (Chart) .

The seven males and five females imported from South Africa arrived in mid-February 2023. By October, each male should have ideally spent six months, and each female five months, in the wild. Together, the 12 South African imports should have spent a cumulative 67 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

In reality, as the chart shows, they spent not even 11 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

Yet, the project lost 40% of its functional adult population. Of the 20 cats that arrived in India, six died (Dhatri and Sasha from Namibia; Suraj, Uday, Daksha, and Tejas from South Africa), and two were unfit for the wild. Four cubs were born in India, three of which died, and the fourth is being raised in captivity.

HOME RANGE: Only three cheetahs — Namibian imports Asha, Gaurav, and Shaurya — have spent more than three months at a stretch in the wild. Even they have been stuck inside bomas since July. It is unlikely any of the cats would have established “home ranges” in Kuno.

REPRODUCTION: The goal, as per the Action Plan, was: “Cheetah successfully reproduce in the wild”. However, Siyaya aka Jwala, the Namibian female that gave birth to four cubs in Kuno, was captive raised herself. She was unfit for the wild and her cubs were born inside a hunting boma.

LIVELIHOOD: The project has indeed generated a number of jobs and contracts for the local communities, and the price of land has appreciated significantly around Kuno. No human-cheetah conflict has been reported in the area.

Compromises, mistakes

Three of the eight Namibian cheetahs — Sasha, which was the project’s first casualty, and Jwala and Savannah alias Nabha, who were never released outside the bomas in Kuno — were captive-raised, reportedly as “research subjects”. They were offered to India to meet the “hard deadline” for the import.

To get the cheetahs , India promised to support Namibia for “sustainable utilisation and management of biodiversity…at international forums”. Weeks after the cheetahs arrived, India abandoned its decades-old stand by abstaining at the CITES vote against trade in elephant ivory.

In Kuno, captive breeding was attempted by putting the sexes together in hunting bomas. However, due to extremely low genetic variation within the species, a cheetah female is very selective in seeking out most distantly related males. That is why giving males access to a female not in heat can lead to violence.

The project got lucky with Jwala in March. But the gamble failed when two South African males killed the female Phinda alias Daksha in May.

The monitoring teams failed to intervene in time when three cubs succumbed to acute dehydration in May. Maggot infestation in multiple animals — which would have affected their gait — also went unnoticed until the festering wounds under their radio collars killed two in July.

The project experts had failed to factor in seasonal variation while sourcing animals from the southern hemisphere. The animals grew winter coats during the Indian monsoon, leading to prolonged wetness and infection.

Kuno’s carrying capacity

The project’s original goal, “to establish a free-ranging breeding population of cheetahs in and around Kuno”, has been diluted to “managing” a meta population through assisted dispersal.

The Cheetah Action Plan estimated “high probability of long-term cheetah persistence” within populations that exceed 50 individuals. Cheetal is the cheetah’s prime prey in Kuno where project scientists reported per-sq-km cheetal density of 5 (2006), 36 (2011), 52 (2012) and 69 (2013).

The feasibility report in 2010 estimated that 347 sq km of Kuno sanctuary could sustain 27 cheetahs, and the 3,000 sq km larger Kuno landscape could hold 70-100 animals.

After the project was revived in 2020, the Cheetah Action Plan assessed Kuno’s cheetal density at 38 per sq km which could sustain 21 cheetahs, while a larger landscape of 3,200 sq km could support 36. A single population of 50 cheetahs was no longer deemed feasible.

The Action Plan also offered another estimate based on distance-sampling — 23 cheetals per sq km — which would make it difficult to support even 36 cheetahs in the larger Kuno landscape.

Paradigm shift ahead

Since Kuno cannot support a genetically self-sustaining population, the project’s only option is a meta-population scattered over central and western India. But unlike leopards, which dominate this landscape, cheetahs cannot travel the distances between these pocket populations on their own.

A solution would be to borrow from the South African model that periodically translocates animals from one fenced reserve to another to maintain genetic viability. But if this “assisted dispersal” becomes the new normal, the case for maintaining forest connectivity that allows natural dispersal of wildlife will be severely weakened.

Tavleen Singh writes: Modi as a Congress role model Subscriber Only

In BJP bastion, voters flag: 'Missing oppn not healthy’ Subscriber Only

Diljit Dosanjh's journey to being Amar Singh Chamkila Subscriber Only

Odisha to Cambodia – how Indians were duped by dishonest Subscriber Only

Chital population up, a tiny Andaman island struggles to keep Subscriber Only

Behind the immersive art exhibition app for Apple’s Vision Pro Subscriber Only

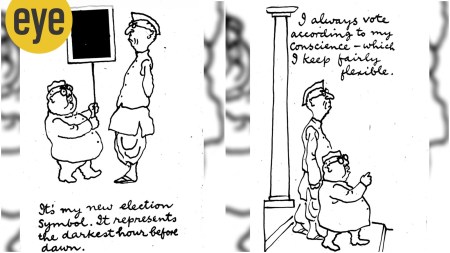

Abu Abraham's cartoons: a mind more wicked than any search

The Satwik-Chirag interview Subscriber Only

Jay Mazoomdaar is an investigative reporter focused on offshore finance, equitable growth, natural resources management and biodiversity conservation. Over two decades, his work has been recognised by the International Press Institute, the Ramnath Goenka Foundation, the Commonwealth Press Union, the Prem Bhatia Memorial Trust, the Asian College of Journalism etc. Mazoomdaar’s major investigations include the extirpation of tigers in Sariska, global offshore probes such as Panama Papers, Robert Vadra’s land deals in Rajasthan, India’s dubious forest cover data, Vyapam deaths in Madhya Pradesh, mega projects flouting clearance conditions, Nitin Gadkari’s link to e-rickshaws, India shifting stand on ivory ban to fly in African cheetahs, the loss of indigenous cow breeds, the hydel rush in Arunachal Pradesh, land mafias inside Corbett, the JDY financial inclusion scheme, an iron ore heist in Odisha, highways expansion through the Kanha-Pench landscape etc. ... Read More

- African cheetahs

- Express Explained

- Express Premium

BJP is trying to revive the legacy of Kamaraj, the last non-Dravidian icon in Tamil Nadu, through their new solo leader K Annamalai. The 40-year-old former IPS officer has no political baggage and is targeting the youth vote.

More Explained

Best of Express

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 08: Latest News

- 01 Anandraj Ambedkar says will contest polls from Amravati

- 02 Over 6,500 booked in 3 months for drunk driving

- 03 Chess Candidates Tournament 2024 Live Updates: Vidit, Humpy lose; Pragg, Vaishali, Gukesh draw

- 04 Bombay High Court refuses to quash FIR filed by woman after divorce for ill-treatment faced during marriage

- 05 Is New York City overdue for a major earthquake?

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Gold Rate Today

- Silver Rate Today

- Petrol Rate Today

- Diesel Rate Today

- Web Stories

Has India’s Reintroduction of Cheetahs Been a Success?

A cheetah released into Kuno National Park as part of India’s Project Cheetah, September 17, 2022. Photo: Press Information Bureau

India welcomed four new-born cheetah cubs in late March – more than 70 years after the world’s fastest land mammal was declared officially extinct there.

The cubs’ parents, Siyaya and Freddie, are two of eight rehabilitated cheetahs brought from Namibia to India’s Kuno National Park (KNP) in the central state of Madhya Pradesh last September.

Another 12 cheetahs were brought from South Africa in February, in an agreement between the two countries, and put into quarantine enclosures.

India has made ambitious attempts to reintroduce the feline species. The intercontinental movement of the animals is part of the country’s cheetah restoration initiative known as “Project Cheetah.” The Indian government hopes 50 cheetahs will be brought in from African countries to various national parks over the next five years.

“Project Cheetah will continue. While we do understand and accept there will be losses associated with introducing these cheetahs, we also look forward to celebrating the first Indian cubs born to a Namibian cheetah,” said the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), the international organisation that facilitated the historic translocation.

India prepares for cheetah population

Today, some 8,000 cheetahs are found in southern and eastern Africa, particularly in Namibia, South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, and Tanzania, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). A tiny population of another subspecies, the Asiatic cheetah, is found in Iran.

Before the arrival of the felines in India, expert teams from Namibia and South Africa trained Indian forest officers and wildlife experts on cheetah handling, breeding, rehabilitation, medical treatment and conservation.

Pradnya Giradkar, India’s first cheetah conservation specialist, said bringing back the species has been a huge challenge.

“Cheetah is the only animal in recorded history to become extinct from India due to unnatural causes. Therefore, scientific studies on the ecological interaction between habitat composition, habitat quality and demography of cheetahs and their prey are required to maintain viability,” Giridkar told DW .

She welcomed the latest cubs. “Increases in the number of reproductive events with longevity are key processes that influence annual individual performance that follows multiple generations. Of course, reproductive success depends on phenotypic, environmental, and genetic factors.”

Wildlife experts concerned over inadequate space

The announcement of the cubs’ arrival in March came just days after one of the Namibian cheetahs, a female named Sasha, died of kidney disease.

Ravi Chellam, a wildlife biologist and CEO at Metastring Foundation, said that as much as the death of an adult female does not signal the failure of Project Cheetah, the birth of these cubs does not indicate its success either.

“We should also remember that the mating took place within a fenced area of less than six square kilometers and the cubs were also born within this enclosure. This project is based on poor science, it’s is in conflict with stated national conservation priorities and is also at odds with the rule of law,” Chellam told DW .

According to the wildlife biologist, there is a fundamental problem with the action plan guiding the introduction of African cheetahs in India, as it doesn’t recognize the lack of adequate space for the animals to establish a viable population.

Last October, eight wildlife scientists expressed concerns in the research journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, that India’s cheetah reintroduction plan hinged on an unsupported claim that the country had sufficient and suitable space for cheetahs. They further argued that the plan ignores crucial scientific findings from important recent demographic studies on free-ranging cheetahs.

According to Chellam, “India has erred…by bringing the cats much before habitats of adequate size and quality were ready. This prolonged captivity will have negative impacts on the cats. I sincerely hope that we do not import more cheetahs from Africa until we have secure and good quality habitats to host them.”

Lack of predators may ensure cub survival rate

Yadvendradev Jhala, a conservationist and former dean at the Wildlife Institute of India, is one of the architects behind the cheetah reintroduction project. Jhala says that with 20 cheetahs from two different countries, India has a diverse cheetah genetic composition and if breeding was done judiciously, it could maintain this diversity for posterity.

“Cheetahs breed rapidly in a conducive environment. The birth of the cubs and mating by three females shows that the conditions in Kuno are ideal for them. It is the survival of cubs that is a concern. About 50% of cheetah cubs survive in the wild where they succumb to larger predators,” Jhala told DW .

“But in semi-wild conditions without predators like in the enclosure of Kuno, cub survival rates can be as high as 90-95%. This will help increase our cheetah populations indigenously and reduce our dependency on import,” he added.

The cheetahs at the KNP have been fitted with satellite collars and remain in a fenced holding area as they adapt to their new environment. Scientists are tracking their movements and monitoring their health.

The cheetahs will be released into the wild once conservationists decide they have fully adapted to local conditions.

This article was originally published on DW .

Silence of the Wolves: How Human Landscapes Alter Howling Behaviour

After Intense Debates About Timelines, Next IPCC Synthesis Report to Arrive in 2029

Why Less Sleep Cannot Make Workers More Productive

Why We Shouldn’t Lose Our Minds Over Sleep

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Personal Finance

- Today's Paper

- Partner Content

- Entertainment

- Social Viral

- Pro Kabaddi League

What is Project Cheetah?

The nation is waiting to celebrate the arrival of cheetahs from africa. most of us may have never seen a cheetah as it went extinct from india about 70 years ago. here's more about project cheetah.

Click here to follow our WhatsApp channel

India's plan to reintroduce Cheetah follows success in other such projects

Exotic inflation: price no worry for indian collectors to get status pets, this shipping company is rerouting its ships. to save blue whales, ind vs sa 4th t20i highlights: india annihilate south africa by 82 runs, cii-exim bank conclave: goyal calls for deepening trade ties with africa, nearly 100,000 people get work under urban job scheme in rajasthan, chhattisgarh deposits about 91% of targeted rice in central pool, lucknow metro rail project to cost rs 4,265 crore, complete in 5 years, pm modi's outreach to vladimir putin risks putting india in us crosshairs, andhra cm defends 3-capital formula amid fresh protest by amaravati farmers.

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Sep 16 2022 | 7:00 AM IST

Explore News

- Suzlon Energy Share Price Adani Enterprises Share Price Adani Power Share Price IRFC Share Price Tata Motors Share Price Tata Steel Share Price Yes Bank Share Price Infosys Share Price SBI Share Price Tata Power Share Price HDFC Bank Share Price

- Latest News Company News Market News India News Politics News Cricket News Personal Finance Technology News World News Industry News Education News Opinion Shows Economy News Lifestyle News Health News

- Today's Paper About Us T&C Privacy Policy Cookie Policy Disclaimer Investor Communication GST registration number List Compliance Contact Us Advertise with Us Sitemap Subscribe Careers BS Apps

- Budget 2024 Lok Sabha Election 2024 IPL 2024 Pro Kabaddi League IPL Points Table 2024

Celebrating the One-Year Milestone of Project Cheetah: Triumphs, Challenges, and Renewed Commitment

- by CCF Staff September 17, 2023

OTJIWARONGO, Namibia – 17 September 2023 – Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) is joining with partners and supporters around the world in celebrating the first anniversary of Project Cheetah. While the initial year of the historic reintroduction of cheetahs in India has been marked by setbacks, the Project Cheetah team remains dedicated to their mission. While the cheetahs await re-release, CCF has offered advice and new strategies to help ensure the successful reintegration of these majestic creatures into their natural habitat.

Dr. Laurie Marker, Founder and Executive Director of the Cheetah Conservation Fund, expressed the significance of this achievement, saying, “Bringing back cheetahs to India was a daring endeavor, full of challenges. We celebrated the birth of the first litter of four cubs born to one of the females from Namibia and the additional arrival of a group of 12 cheetahs from South Africa. Despite setbacks and difficulties that prompted a decision to retrieve the animals, we are leveraging these experiences to reassess strategies before the cheetahs are released once again.”

Over 12 years in the making, Project Cheetah came to fruition on 17 September of 2022 when CCF staff traveled to India to deliver a gift from the Namibian government: eight wild cheetahs. Namibia considered the “cheetah capitol of the world” with the highest density of wild cheetah, generously donated the first eight individuals to establish a new meta-population in India. The historic initiative is part of a larger, multi-year agreement to aid in the conservation of the species. The cheetahs, once a vital part of India’s ecosystem, faced a tragic decline, with the last recorded sighting in the 1950s, marking their local extinction. However, the vision of reintroducing these charismatic animals emerged, driven by a collective determination to restore ecological balance and preserve India’s biodiversity.

“As CCF’s International Patron, the project is on track and Namibia is proud to be a part of expanding the cheetahs’ territory into Namibia.” stated The Honorable Professor Peter Katjavivi, Namibia’s Speaker of the National Assembly.

“Bringing the cheetah back to India is an ambitious project of Government of India that intends to reestablish the species in its historic range. In this important species conservation project, the contribution of Republic of Namibia and Cheetah Conservation Fund has been immense and commendable. CCF has been instrumental in translocation of founding population of cheetahs to India and also in training the officials of Kuno National Park in cheetah management issues.” stated Dr. S. P. Yadav, ADGF (Project Tiger & Elephant) & Member Secretary, National Tiger Conservation Authority

The reintroduction process posed formidable challenges, involving the task of acclimating wild cheetahs to a habitat that had not seen this cat species for 70 years. Since the inception of the program, dedicated teams have tirelessly worked to create an environment conducive to the cheetah’s natural instincts. This remarkable journey was marked by both setbacks and successes. Despite the challenges, there has also been many positive outcomes including, the confirmation that the reintroduced cheetahs are hunting native prey species. It is indeed a matter of great management outcome to note that Siyaya and Savanah, two female Cheetahs which were wild caught and had spent substantial time in captivity in Namibia, have now remarkably adopted to the wilderness on Indian soil and have been independently hunting. As part of the rewilding process since they were released, they have shown promising signs and would be fit for release into the wild in due course following due diligence.

There has been no human-wildlife conflict incidents and the communities surrounding Kuno National Park have been incredibly accepting of having cheetahs living in such close proximity. With close to 90 leopards also residing in the park, there has been no reported conflicts between the cheetahs and other predator species. Cheetahs often face significant threats from other predators like hyenas and leopards, yet the presence of leopards has not deterred the cheetah’s integration back into their former range.

A pivotal aspect of monitoring the reintroduced cheetahs is the use of GPS radio tracking collars. These technological marvels have enabled researchers and conservationists to gather essential data about the cheetah’s movements, habits, and interactions, offering invaluable insights into their integration back into the wilds of India. While concerns have been raised about the potential impact of the collars, their role in the overall success of this reintroduction effort cannot be overstated.

CCF’s Conservation Biologist and Release Specialist, Eli Walker emphasized the significant impact collars have on the study of cheetahs in the wild, stating, “The tracking collars remain critical to the success of the project. Without them, no post-release monitoring is possible and therefore the animals’ progress in the wild of India would not be possible to determine. Additionally, without the collars, post-release management and support of the released cheetahs would not be possible.”

There are limited alternatives to tracking collars and the emergence of a direct replacement for this technology is not imminent. With the safety of cheetahs at the forefront of concerns, CCF’s cheetah release and management experts are helping the Project Cheetah team to address and find solutions, ensuring that when the cheetahs are released again, the risk of collar usage is mitigated.

As we celebrate this extraordinary milestone, it serves as a reminder of the urgency to conserve and protect the natural world. Dr. Marker remarked, “The return of the cheetahs to India is not just about their survival; it is a testament to our commitment to safeguard the web of life that sustains us all. We must recognize that our actions have repercussions that extend far beyond our own lifetimes.” Reflecting on this remarkable journey, Dr. Marker’s words resonate hope: “The anniversary of the cheetah’s return to India is a celebration of the boundless possibilities that emerge when humans unite for nature.”

Cheetah Conservation Fund

Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) is the global leader in research and conservation of cheetahs and dedicated to saving the cheetah in the wild. CCF is an international non-profit organization headquartered in Namibia, with a base in Somaliland and a partner field organization in Kenya as well as having fundraising operations in the United States, Canada, Australia, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom and a partner organization in Germany. Founded in 1990, CCF is celebrating 33 years, making it the longest running and most successful cheetah conservation organization. For more information, please visit www.cheetah.org .

Project Cheetah

The Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), in partnership with India’s Madhya Pradesh Forest Department, Wildlife Institute of India, the National Tiger Conservation Authority, and the governments of Namibia and South Africa, embarked on a collaborative reintroduction effort to reintroduce the majestic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) back into India’s Kuno National Park, after having been extinct for over 70 years. Project Cheetah’s goal is to establish a viable cheetah meta-population in India that allows the cheetah to perform its functional and historical role as a top predator and to provide space for the expansion of the cheetah population within its historical range thereby contributing to its global conservation efforts.

MEDIA CONTACT: For media inquiries, please contact: Teresia Robitschko [email protected] +491782722347 or Dr. Laurie Marker [email protected] +264811247887.

Related Reading

February 8, 2024

January 16, 2024

December 14, 2023

Keep up with the cheetahs Join our mailing list

- [email protected]

- 898-888-2525

Home / Current Affairs / One year of Project Cheetah: Hits, misses and paradigm shift ahead

One year of Project Cheetah: Hits, misses and paradigm shift ahead

- By : Author Desk

- Updated : November 16, 2023

For Latest Updates, Current Affairs & Knowledgeable Content.

Context- A year after it was launched, Project Cheetah , India’s ambitious attempt to introduce African cats in the wild in the country, has claimed to have achieved short-term success on four counts: “50% survival of introduced cheetahs, establishment of home ranges, birth of cubs in Kuno”, and revenue generation for local communities.

The claims assessed

- The test of survival is in the wild, not in captivity where animals are under protective care. According to India’s official Cheetah Action Plan, the male and female cats from both Namibia and South Africa were to spend two and three months respectively inside bomas (enclosures) before being released in the wild.

- Therefore, in the 12 months since they arrived in India in September 2022, each of the three Namibian males should have spent 10 months in the wild, and each of the five Namibian females should have spent nine months in the wild.

- In all then, the eight cheetah imports from Namibia should have spent a cumulative 75 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

(Credits- Indian Express)

- The seven males and five females imported from South Africa arrived in mid-February 2023. By October, each male should have ideally spent six months, and each female five months, in the wild. Together, the 12 South African imports should have spent a cumulative 67 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

- In reality, as the chart shows, they spent not even 11 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

- Yet, the project lost 40% of its functional adult population. Of the 20 cats that arrived in India, six died (Dhatri and Sasha from Namibia; Suraj, Uday, Daksha, and Tejas from South Africa), and two were unfit for the wild. Four cubs were born in India, three of which died, and the fourth is being raised in captivity.

HOME RANGE:

- Only three cheetahs — Namibian imports Asha, Gaurav, and Shaurya — have spent more than three months at a stretch in the wild. Even they have been stuck inside bomas since July. It is unlikely any of the cats would have established “home ranges” in Kuno.

REPRODUCTION:

- The goal, as per the Action Plan, was: “Cheetah successfully reproduce in the wild”. However, Siyaya aka Jwala, the Namibian female that gave birth to four cubs in Kuno, was captive raised herself. She was unfit for the wild and her cubs were born inside a hunting boma.

LIVELIHOOD:

- The project has indeed generated a number of jobs and contracts for the local communities, and the price of land has appreciated significantly around Kuno. No human-cheetah conflict has been reported in the area.

Compromises, mistakes

- Three of the eight Namibian cheetahs — Sasha, which was the project’s first casualty, and Jwala and Savannah alias Nabha, who were never released outside the bomas in Kuno — were captive-raised, reportedly as “research subjects”. They were offered to India to meet the “hard deadline” for the import.

- To get the cheetahs, India promised to support Namibia for “sustainable utilisation and management of biodiversity…at international forums”. Weeks after the cheetahs arrived, India abandoned its decades-old stand by abstaining at the CITES vote against trade in elephant ivory.

- In Kuno, captive breeding was attempted by putting the sexes together in hunting bomas. However, due to extremely low genetic variation within the species, a cheetah female is very selective in seeking out most distantly related males.

- The project got lucky with Jwala in March. But the gamble failed when two South African males killed the female Phinda alias Daksha in May.

- The monitoring teams failed to intervene in time when three cubs succumbed to acute dehydration in May. Maggot infestation in multiple animals — which would have affected their gait — also went unnoticed until the festering wounds under their radio collars killed two in July.

- The project experts had failed to factor in seasonal variation while sourcing animals from the southern hemisphere. The animals grew winter coats during the Indian monsoon, leading to prolonged wetness and infection.

Kuno’s carrying capacity

- The project’s original goal, “to establish a free-ranging breeding population of cheetahs in and around Kuno”, has been diluted to “managing” a meta population through assisted dispersal.

- The Cheetah Action Plan estimated “high probability of long-term cheetah persistence” within populations that exceed 50 individuals.The feasibility report in 2010 estimated that 347 sq km of Kuno sanctuary could sustain 27 cheetahs, and the 3,000 sq km larger Kuno landscape could hold 70-100 animals.

- After the project was revived in 2020, the Cheetah Action Plan assessed Kuno’s cheetal density at 38 per sq km which could sustain 21 cheetahs, while a larger landscape of 3,200 sq km could support 36. A single population of 50 cheetahs was no longer deemed feasible.

Paradigm shift ahead

- Since Kuno cannot support a genetically self-sustaining population, the project’s only option is a meta-population scattered over central and western India. But unlike leopards, which dominate this landscape, cheetahs cannot travel the distances between these pocket populations on their own.

Way Forward- A solution would be to borrow from the South African model that periodically translocates animals from one fenced reserve to another to maintain genetic viability. But if this “assisted dispersal” becomes the new normal, the case for maintaining forest connectivity that allows natural dispersal of wildlife will be severely weakened.

Syllabus- GS-3; Environment

Source- Indian Express

Any Doubts ? Connect With Us.

Join Our Channels

For Latest Updates & Daily Current Affairs

Connect With US Socially

- 898-888-2525, 898-888-2626

- 19/2A Shakti Nagar, Nagiya Park Near Delhi University, New Delhi - 110007

© 2024 Vajirao IAS. All rights reserved.

Request Callback

Fill out the form, and we will be in touch shortly.

Essay on Cheetah

Students are often asked to write an essay on Cheetah in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Cheetah

The cheetah: a speedy marvel.

Cheetahs are the world’s fastest land animals. They live in Africa’s grasslands and are known for their slender bodies and spotted coats.

Speed and Hunting

Cheetahs can reach speeds of up to 60 miles per hour! They use their speed to chase down and catch prey, usually small to medium-sized animals.

Threats to Cheetahs

Sadly, cheetahs face many threats. Habitat loss and illegal wildlife trade are major concerns. Efforts are ongoing to protect these amazing creatures and their habitats.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on Cheetah

- Paragraph on Cheetah

250 Words Essay on Cheetah

The majestic cheetah: an overview.

The cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus, a member of the Felidae family, is renowned for its incredible speed, reaching up to 60-70 miles per hour in short bursts. This speed, combined with its agility, makes it a formidable predator in the wild, primarily in Africa’s grasslands.

Adaptations for Speed

The cheetah’s slender, lightweight body and long legs are perfectly designed for speed. Its large nasal passages enable quick oxygen intake, while the adrenal gland produces adrenaline to fuel its explosive sprints. Interestingly, the cheetah’s claws are semi-retractable, providing additional grip, akin to a runner’s spikes.

Endangered Status

Sadly, the cheetah is currently classified as a vulnerable species. Their numbers have dwindled due to habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and illegal wildlife trade. Efforts to conserve these magnificent creatures are ongoing, with initiatives focused on habitat preservation and community education.

Ecological Importance

As apex predators, cheetahs play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of their ecosystems. They control the population of their prey, preventing overgrazing and promoting biodiversity. Their decline could disrupt these delicate systems, underscoring the importance of their conservation.

The Cheetah’s Future

The future of the cheetah lies in the hands of conservationists and the wider human population. Through concerted efforts to protect their habitats and combat illegal trade, there is hope for the survival of this remarkable species. The cheetah’s story is a poignant reminder of our shared responsibility to protect Earth’s biodiversity.

The cheetah is not just an embodiment of speed and grace; it is a symbol of the wild’s fragility and resilience. Understanding and appreciating the cheetah is crucial for its survival and the health of our planet.

500 Words Essay on Cheetah

Introduction.

The cheetah, scientifically known as Acinonyx jubatus, is an iconic species primarily recognized for its exceptional speed. As the fastest land mammal, the cheetah serves as a symbol of agility and grace. However, beyond their speed, cheetahs are fascinating creatures with unique biology, behavior, and ecological significance.

Physical Attributes and Adaptations

Cheetahs are slender-bodied animals, designed for speed. They weigh between 75-150 pounds, with a body length of up to 4.5 feet and a tail length of up to 33 inches. Their coats are typically a yellowish-tan or rufous to greyish white, with black spots. The most striking feature is the ‘tear mark’ running from the inner corner of each eye down to the sides of the mouth.

Their physical adaptations are specifically tailored for speed. The large nostrils and adrenal glands facilitate rapid oxygen intake and adrenaline production, respectively. The lightweight frame and long, flexible spine enable them to stretch their bodies while running at high speeds. The non-retractable claws provide grip, and the specialized pads act like tire treads for traction.

Behavior and Lifestyle

Cheetahs are diurnal animals, hunting primarily during the day to avoid competition with nocturnal predators like lions and hyenas. Their hunting strategy is a blend of stealth and speed; they use their excellent eyesight to spot prey from a distance, stalk them, and then unleash their explosive speed in a final sprint.

Cheetahs are not as social as lions, but they do form groups, particularly males. Male siblings often form coalitions that stay together for life, defending territories and hunting together. Females, on the other hand, are more solitary.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Female cheetahs reach sexual maturity at around 20-24 months, and they can give birth to three to five cubs after a gestation period of approximately 90 days. Mother cheetahs raise their cubs alone, teaching them survival skills until they become independent at around 18 months.

The lifespan of cheetahs in the wild is typically 10-12 years, although in captivity, they can live up to 20 years. However, cub mortality is high due to predation and disease.

Conservation Status and Threats

Cheetahs are currently listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Their population is decreasing due to habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, illegal wildlife trade, and climate change.

Conservation efforts are underway to protect and increase the cheetah population. These include habitat restoration, anti-poaching initiatives, community education, and scientific research to better understand cheetah biology and behavior.

Cheetahs are remarkable creatures, embodying a perfect blend of power and grace. Their unique adaptations make them a fascinating subject of study. However, their declining numbers highlight the urgent need for effective conservation strategies. Understanding and appreciating these majestic animals is the first step towards ensuring their survival and the health of the ecosystems they inhabit.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Charles Babbage

- Essay on Caste System

- Essay on Carrom

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Ready-made safaris

- Experiences

- Special offers

- Accommodation

- Start planning

- Booking terms

- When to go on safari - month by month

- East or Southern Africa safari?

- Solo travellers

- Women on safari

- Accommodation types & luxury levels

- General tips & advice

- All stories

- Afrika Odyssey Expedition

- Photographer of the Year

- Read on our app

- 2024 entries

- 2024 details

- 2024 prizes

- 2024 entry form

- 2023 winners

- Collar a lion

- Save a pangolin

- Rules of engagement

- Job vacancies

- Ukuri - safari camps

A passage to India – how the journey of southern Africa’s cheetah divided the experts

On Saturday, the 18 th of February, 12 more southern African cheetahs landed in India to join eight of their cohorts in Kuno National Park. Theoretically, these trailblazing cheetahs are intended to herald the long-term return of wild cheetahs to India. This project has divided conservationists along academic, ethical and philosophical lines. Critics have labelled the reintroduction “ecologically unsound”, “a vanity project”, and “grossly expensive”. Equally, experts with abundant experience in cheetah conservation have thrown their weight behind the project, highlighting the importance of restoring cheetahs to parts of their historic range and the potential benefits to Indian conservation.

Cheetahs have been extinct in India for over seven decades, but plans for their return have been afoot for many years. The first eight individuals from Namibia (after a period in quarantine) made the journey to Kuno National Park in September 2022. Amid the media furore over Project Cheetah, two groups of highly esteemed scientists – one for and one against – penned their opinions in correspondence published in Nature Ecology & Evolution . Each article neatly summarises the arguments put forward in various publications since the arrival of the first cheetahs. Read together, they highlight the complexities of the issues at play.

The argument against Project Cheetah

The first article, published in December 2022, is titled “Introducing African cheetahs to India is an ill-advised conservation attempt” and was authored by a group of experienced big-cat conservationists and scientists (Gopalaswamy et al., 2022). Many of the authors have been critical of the project since its inception. They argue that the costly plan has the potential to serve as a “distraction” instead of aiding global cheetah conservation.

Though there has yet to be scientific consensus on subspecies divisions, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group recognised four distinct subspecies of cheetah. Of these, the Southeast African cheetah ( Acinonyx jubatus jubatus ) and the Asiatic cheetah ( Acinonyx jubatus venaticus ) are relevant to the debate at hand. Before their extinction, the cheetahs found in India would have been Asiatic cheetahs. At present, the only remaining Asiatic cheetahs are found in Iran and are classified as Critically Endangered. In the opinion of Gopalaswamy et al. (2022), there are unknown ecological, disease and genetic risks associated with replacing Asiatic cheetahs with African ones.

The authors indicate that the plan to translocate cheetahs from Africa to India is based on three unsubstantiated claims. The first is that cheetahs have run out of space in Africa, the second is that India has sufficient space and habitat to support a cheetah population, and, finally, that translocations have successfully restored cheetah range in the past.

They cite contemporary research from the Maasai Mara from one of the authors (Dr Femke Broekhuis) that shows that cheetahs utilise disproportionately large home ranges and occur at low population densities. The authors argue that this, along with (presumably) declining cheetah numbers in Africa, makes them unsuitable as a source population for translocations. Based on this research, they also believe that the studies in Kuno National Park for the action plan may have substantially overestimated the carrying capacity. According to the action plan, the calculated carrying capacity was based on a density estimate from Namibia, which Gopalaswamy et al. (2022) suggest is outdated and possibly inaccurate.

The site of the first cheetah translocations – Kuno National Park – is a 748 km 2 (74,800 hectares) park located just over 300km south of Delhi. It is unfenced and surrounded by densely populated villages and farms. Gopalaswamy et al. (2022) imply that the size and surrounding anthropogenic pressures (along with some 500 feral cattle within the park) make it a poor habitat choice for the cheetahs. Furthermore, they argue that the other destinations named in the action plan for future translocations are equally inappropriate.

Gopalaswamy et al. (2022) also distinguish between “free-ranging” and “fenced-in” cheetahs. Most cheetahs in South Africa and many from Namibia come from smaller fenced reserves. These animals cannot naturally immigrate or emigrate, so the populations must be intensively managed. The cheetahs sourced for the translocations came from such a setup. The authors write that to the best of their knowledge, they know of no reintroduction successes where fenced-in cheetahs have been successfully reintroduced into an unfenced area, even within Africa. They argue that where these fenced-in populations are managed independently without achieving self-sustaining populations, there will be an urgency to find release sites that could “trigger unplanned, hastily executed translocation programmes”.

They write that they anticipate that “adopting such a speculative and unscientific approach will lead to human-cheetah conflicts, death of the introduced cheetahs or both, and will undermine other science-based species recovery efforts, both globally and within India”.

Instead, the scientists call on India to redirect the nearly US$ 60 million total cost of Project Cheetah towards global cheetah conservation efforts, including habitat protection and connectivity and enhancing human-cheetah relations in Iran, Africa, or both. Alternatively, they suggest revising the current action plan to reintroduce cheetahs to India using a “science-based approach” to rigorously assess the policies and methods utilised. The focus should be securing India’s threatened savannahs and grasslands and avoiding the disruption of other ongoing conservation efforts, such as the reintroduction of Asiatic lions.

They conclude that “there is an urgent need for international bodies, such as the IUCN and the wider community of cheetah and carnivore biologists, to re-evaluate the purpose and practice of such intercontinental, large carnivore translocation efforts”.

The argument for Project Cheetah

In response to this correspondence, a group of vets, scientists, ecologists and cheetah conservationists published their dissenting opinion in an article titled “The case for the reintroduction of cheetahs to India” (Tordiffe et al., 2023). Many of the authors have been intimately involved in the project since its inception, and all were involved in the scientific advisement on both the Indian and southern African sides of the operation.

Tordiffe et al. (2023) argue that cheetahs once occupied an ecological niche in India, which has been left vacant since their extinction. They cite previous research showing that the return of carnivores is particularly important in restoring the functional ecology of ecosystems. They suggest that the widespread human-wildlife conflict and poaching that precipitated the extinction of cheetahs in India have since been controlled through legislation and effective enforcement. Furthermore, suitable habitat, prey availability and anthropogenic pressures were thoroughly assessed before selecting Kuno National Park and other protected areas as potential reintroduction sites.

According to the Project Cheetah action plan, approximately 100,000 km 2 (10 million hectares) of legally protected reserves in India lie within the historic range of the cheetah and could potentially support breeding cheetah populations. Tordiffe et al. (2023) disagree with Gopalaswamy et al.’s (2022) approach of using East African cheetah population densities to estimate the potential carrying capacities of the selected release sites in India. Instead, they suggest that the biomass of suitable prey will determine such densities.

In answer to Gopalaswamy et al.’s (2022) discussion around the Asiatic cheetahs, Tordiffe et al. (2023) point to the IUCN guidelines for population reintroductions. These require that potential source populations have adequate genetic diversity and that removing a determined number of individuals would not compromise the source population. Given the recent announcement by the Iranian Department of Environment that only 12 confirmed Asiatic cheetahs remain, there is no way they could be utilised for this initiative. Instead, Tordiffe et al. (2023) argue that the southern African cheetah population has the greatest documented genetic diversity and is sufficiently large to supply founding individuals without negatively affecting their numbers.

The authors highlight that unpublished data indicates that the managed cheetah metapopulation in southern Africa of around 500 cheetahs is currently growing at a rate of 8.8% per year. These animals occur predominantly on smaller, fenced reserves, and translocation is vital to this metapopulation management. In South Africa alone, population viability analysis indicates that this population could sustain the removal of 29 individuals without detriment. Though they acknowledge that there are still areas in Africa that could theoretically support reintroduced cheetahs, the authors suggest that few of the sites are feasible in reality. They suggest that there are several socioeconomic, cultural and religious differences that contribute to a greater tolerance for large predators in India than in Africa, as evidenced by other large carnivore conservation initiatives in India.

Tordiffe et al. (2023) also refute the suggestion that there have been no successful translocations of “fenced-in” cheetahs into “free-ranging” environments. They cite the release of 22 cheetahs into the unfenced Zambezi Delta in Mozambique in August 2021, along with the release of 36 cheetahs onto Namibian farmlands, including some unfenced properties. With respect to the risk of disease transmission, three of the authors (and other experts) have conducted a comprehensive disease risk analysis. Though most diseases were judged to be of low or very low risk, those deemed medium risk are managed through a combination of vaccination programmes and antiparasitic treatments.

Finally, the response concedes that the suggestion by Gopalaswamy et al. (2022) that money for the project might be better invested in other cheetah conservation initiatives is “intriguing”. However, the authors suggest that this is unlikely, given that governments tend to prioritise conservation projects in their own jurisdictions.

Though Tordiffe et al. (2023) highlight the cheetahs’ potential role as an umbrella species that will benefit the “broader biodiversity conservation and livelihood goals in India”, they acknowledge that this must be evaluated once the project is completed.

Final thoughts

On the 26 th of January 2023, the South African Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment confirmed that India and South Africa had signed a Memorandum of Understanding. Under the terms of the MoU, 100 more cheetahs will be translocated to India over the next ten years to establish a healthy and diverse population. At the outset, there are likely to be significant losses. If the project is successful, it will likely be counted as one of the most daring conservation initiatives of the 21 st century. And more importantly, cheetahs will once again stalk the grasslands and savannahs of India. If it fails, the cheetah will die, millions of dollars will be lost, and the project will be consigned to the learning curve of history.

Few meaningful conservation initiatives could ever be labelled as risk-free. With ever-shrinking wild spaces and changing climates, conservation is facing a turning point. Considered interference and substantial risks may be necessary to protect the earth’s remaining megafauna and reverse the mistakes of the past. But with these decisions will come complex ethical debates that cut to the heart of the intrinsic value of an animal, the definition of “natural”, the importance of genetics and the balance of utilitarianism. There are unlikely to be easy answers or universal agreement.

Gopalaswamy, A. M. et al. (2022) “ Introducing African Cheetahs to India Is an Ill-Advised Conservation Attempt ,” Nature Ecology & Evolution

Tordiffe, A.S.W. et al. (2023) “ The case for the reintroduction of cheetahs to India ,” Nature Ecology & Evolution

Jhala, Y.V., et al. (2021). Action Plan for Introduction of Cheetah in India . Wildlife Institute of India, National Tiger Conservation Authority and Madhya Pradesh Forest Department.

Read more about the Cheetah Conservation Fund , that helped assist wildlife authorities in India with Project Cheetah.

Read more on all there is to know about cheetahs here .

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC:

- Travel with us . Travel in Africa is about knowing when and where to go, and with whom. A few weeks too early / late and a few kilometres off course and you could miss the greatest show on Earth. And wouldn’t that be a pity? Browse our ready-made packages or answer a few questions to start planning your dream safari .

- Subscribe to our FREE newsletter / download our FREE app to enjoy the following benefits.

- Plan your safaris in remote parks protected by African Parks via our sister company https://ukuri.travel/ - safari camps for responsible travellers

Friend's Email Address

Your Email Address

Project Cheetah

On the directions of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), a team of experts comprising of Adrian Tordiffe, Veterinary Wildlife Specialist, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa; Vincent van dan Merwe, Manager, Cheetah Metapopulation Project, The Metapopulation Initiative, South Africa; Qamar Qureshi, Lead Scientist, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Amit Mallick, Inspector General of Forests, National Tiger Conservation Authority, New Delhi visited the Kuno National Park on 30 April, 2023 and reviewed the current status of the Project Cheetah. The team examined all aspects of the project and submitted a comprehensive report on the way forward. The team observed that twenty cheetahs were successfully translocated to Kuno National Park (KNP) in September 2022 and February 2023 from southern Africa in the initial phase of an ambitious project to re-establish the species within its historical range in India. The project hopes to benefit global cheetah conservation efforts by providing up to 100 000 km 2 of habitat in legally protected areas and an additional 600 000 km 2 of habitable landscape for the species. Cheetahs fulfil a unique ecological role within the carnivore hierarchy and their restoration is expected to enhance ecosystem health in India. As a charismatic species, the cheetah can also benefit India’s broader conservation goals by improving general protection and ecotourism in areas that have been previously neglected.

It is not surprising that a project of this magnitude and complexity would face many challenges. This is the first intercontinental reintroduction of a wild, large carnivore species and therefore there is no comparable historical precedent. Due to careful planning and execution, all twenty cheetahs survived the initial capture, quarantine and lengthy transport to the purpose-built quarantine and larger acclimatization camps in KNP in Madhya Pradesh. Releasing the cheetahs into free-roaming conditions poses substantial risks. Like Kuno, no Protected Areas in India are fenced. Animals are thus free to move in and out of the park as they wish. Cheetahs, like other large carnivores are known to range widely during the initial few months after being reintroduced into unfamiliar open systems. These movements are unpredictable and depend on many factors. After several months the cheetahs should establish their own communication networks and settle down in relatively fixed home ranges. It is important that individual cheetahs do not become totally isolated from the reintroduced group during this phase as they will then not participate in breeding and will thus be genetically isolated. Two points should also be noted regarding the carrying capacity of cheetahs in KNP; Firstly, it is impossible to determine the precise carrying cheetah capacity in KNP until the cheetahs have properly established their home ranges and secondly, the home ranges of cheetahs can overlap substantially depending on the prey density and several other factors. While many have made predictions about the anticipated carrying capacity of cheetahs in KNP based on other ecosystems in Namibia and East Africa, the actual number of animals that the reserve can accommodate can only be assessed after the animals are released and have established home ranges. Cheetah home-range sizes and population densities vary tremendously for different cheetah populations in Africa and for obvious reasons, we do not have useful spatial ecology data for cheetahs in India yet.

To date, four of the cheetahs from Namibia have been released from the fenced acclimatization camps into free-ranging conditions in KNP. Two males (Gaurav and Shaurya) have stayed within the park and have not shown any interest in exploring the landscape beyond the borders of the park. A female named Aasha has made two exploratory excursions to the East of KNP beyond the buffer zone but has remained within the broader Kuno landscape and has not ventured into human-dominated areas. Another male (Pawan), explored areas well beyond the boundaries of the park on two occasions, venturing into farmland near the border with Utter Pradesh during his second excursion. He was darted by the veterinary team and returned to an acclimatization camp in KNP. All the cheetahs are fitted with satellite collars that record their location twice a day or more depending upon the situation. Monitoring teams have been employed to follow the released cheetahs 24 hours a day in rotating shifts, keeping some distance to allow the cheetah its normal behaviour and ranging. These teams record any information on the prey hunted by the animals and any other information on their behaviour that may be of importance. It is important that this intensive monitoring continues until the individual cheetahs have established home ranges.

The team inspected most of the cheetahs from a distance and evaluated the current procedures and protocols for managing the animals. All the cheetahs were in good physical condition, making kills at regular intervals and displaying natural behaviours. After discussion with the Forest Department officials in KNP they agreed on the next steps to be taken going forward.

- Five more cheetahs (three females and two males) will be released from the acclimatisation camps into free-roaming conditions in KNP before the onset of the monsoon rains in June. Individuals were chosen for release based on their behavioural characteristics and approachability by the monitoring teams. These released cheetahs will be monitored in the same way as those that have already been released.

- The remaining 10 cheetahs will remain in the acclimatisation camps for the duration of the monsoon season. Certain internal gates will be left open to allow these cheetahs to utilise more space in the acclimatisation camps and for interactions between specific males and females to take place.

- Once the monsoon rains are over in September, the situation will be reassessed. Further releases into KNP or surrounding areas will be done in a planned manner to Gandhisagar and other areas as per the Cheetah Conservation Action Plan to establish meta population.

- Cheetahs will be allowed to move out of KNP and will not necessarily be recaptured unless they venture into areas where they are in significant danger. Their degree of isolation will be assessed once they settle down and appropriate action will to be taken to enhance their connectivity to the group.

- The female who gave birth in March, will remain in her camp to hunt and raise her four cubs.

Information on the recent deaths of two cheetahs in the project:

- Sasha, a six-year-old female from Namibia became ill in late January. Her blood results indicated that she had chronic renal insufficiency. She was successfully stabilised by the veterinary team at KNP, but later died in March. A post-mortem confirmed the initial diagnosis. Chronic renal failure is a common problem in captive cheetahs and many other captive felid species. Sasha was born in the wild in Namibia but spent a large proportion of her life in captive conditions at CCF. The underlying causes of renal disease in felids are unknown, but generally the condition progresses slowly, taking several months or even years before clinical symptoms manifest. The disease is not infectious and cannot be transmitted from one animal to another. It therefore poses no risk to any of the other cheetahs in the project. The prognosis for the condition is very poor and there are currently no effective or ethical treatment options. Symptomatic treatment for the condition only provides temporary improvement, as seen in Sasha’s case.

- Uday, an adult male of uncertain age from South Africa developed acute neuromuscular symptoms on the 23 rd of April just over a week after he was released from his quarantine camp into a much larger acclimatisation camp. During the morning monitoring, it was noted that he was stumbling around in an uncoordinated manner and was unable to lift his head. He was sedated by the KNP veterinary team and treated symptomatically. Blood and other samples were collected to send to the lab to get a better understanding of his condition. He unfortunately died later that same afternoon. Additional wildlife veterinarians and veterinary pathologists were brought in to perform a thorough post-mortem. The initial examination revealed that he had most likely died of terminal cardio-pulmonary failure. Failure of the heart and lungs is common in the terminal stages of many conditions and does not provide much information about the underlying cause of the problem. It also does not explain the initial neuromuscular symptoms. The rest of his organ tissues appeared to be relatively normal except for a localised area of potential haemorrhage in his brain. There were no other signs of injury or infection. Numerous tissue samples were collected for analysis. Importantly, his relatively normal blood results and normal white blood cell count indicate that he was not suffering from any infectious disease that could pose a risk to any of the other animals. The histopathology and toxicology reports still need to be finalised before any conclusions can be drawn. The other cheetahs have been closely monitored and none of them have shown any similar symptoms. They all appear to be perfectly health, are hunting for themselves and displaying other natural behaviours.

All About Project Cheetah, Complete Information.

Finally, the ambitious Project of the government has been launched with the name 'Project Cheetah' which aims to reintroduce the species of cheetah to its former habitat in the nation.

Table of Contents

- Project Cheetah

Finally, the ambitious Project of the government has been launched with the name ‘Project Cheetah’ which aims to reintroduce the species of cheetah to its former habitat in the nation. The cheetah was declared extinct in India in 1952. Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Koriya (today’s Chhattisgarh) shot dead the last three recorded Asiatic cheetahs.

Now, after seven decades, on, September 17 , PM Modi released 8 African cheetahs brought from Namibia at Kuno National Park of India .

Five female and three male cheetahs flew from Namibia to Jaipur in a special Boeing 747-400 aeroplan e of IAF covering a distance of more than 8,000 kilometres in more than 20 hours. From Jaipur, they were taken to Kuno National Park of Madhya Pradesh.

Kuno National Park is a 748 square km protected area. To keep predators out of the park, which can hold a maximum of 21 cheetahs, a 12-km long fence has been built, where they will be kept and closely monitored for one month. Later, they will be released into a safe area.

What is the Project Cheetah?

- In January 2020, Project Cheetah was approved by the Supreme Court of India as a pilot programme with the motive of reintroducing the species of cheetah to India.

- The main motive of the project is to grow healthy meta-populations in India that allow the cheetah to execute its functional role as a top predator, the government had said earlier this year. The cheetah is a flagship grassland species; which plays a major role in conserving and preserving other grassland species in the predator food chain.

- The idea was conceptualised after the initiative taken in 2009 by the combined efforts of Indian conservationists and the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) , a not-for-profit organisation, headquartered in Namibia, which is working to save and rehabilitate the big cat in the Jungle.

- And after more than 12 years of talks, India and the Republic of Namibia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in July 2020. As per the MoU, Over the next five years, Namibia promised to deliver 50 cheetahs to India and for now, the Namibian government gave a green flag to donate the eight felines to launch the programme.

- At the last moment, the “project cheetah” faced an obstacle when India refused to accept three of the eight cheetahs, claiming that they were captive-bred and might not survive in the wild. However, the tourism ministry of Namibia said that all eight animals were seized while they were young and had experienced hunting.

- Currently, only 7,000 cheetahs are surviving, primarily in the woodlands of Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa. This is the first project of its kind as for the first time, wild southern African cheetahs are being relocated to any other part of the world.

FAQs related to Project Cheetah

Q1. How many Cheetahs have been brought from Namibia to India? Ans. 8 African cheetahs brought from Namibia at Kuno National Park of India.

Q2. What is the aim of Project Cheetah? Ans. The aim of the project is to grow healthy meta-populations in India that allow the cheetah to execute its functional role as a top predator.

Q3. Indian Air Force used which aircraft to translocate cheetahs from Namibia to India? Ans. Cheetahs flew from Namibia to Jaipur in a special Boeing 747-400 aeroplan e of IAF

Q1. How many Cheetahs have been brought from Namibia to India?

Ans. 8 African cheetahs brought from Namibia at Kuno National Park of India.

Q2. What is the aim of Project Cheetah?

Ans. The aim of the project is to grow healthy meta-populations in India that allow the cheetah to execute its functional role as a top predator.

Q3. Indian Air Force used which aircraft to translocate cheetahs from Namibia to India?

Ans. Cheetahs flew from Namibia to Jaipur in a special Boeing 747-400 aeroplane of IAF

- current affairs

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- CDS Full Form

- AFCAT Full Form

- NCC Full Form

- CRPF Full Form

- BSF Full Form

- CISF Full Form

- ITBP Full Form

- NSG Full Form

- SSB Full Form

- ISRO Full Form

- DRDO Full Form

- Dams and Reservoirs

- Scientific Names of Animals

- National Parks

- United Nation Agencies

- First Ranked States in Minerals

- Sports Cups and Trophies

- Rivers and their Tributaries

- Mountain Passes

- Famous Inventions and Inventors

- Mountain Passes of India

- IAF Command Training Institutes

- Gallantry Awards

- List of Military Operations

- List of India’s Missiles

- List of Presidents of France

- Largest Telescopes in The World

- List of UK Prime Ministers

- Chief Ministers of Tripura

- Father of Computer

- Largest State in India by Population

- Highest Waterfall in India

- Highest Peak in India

- Longest National Highway

- List of IPL Winners

- Prime Ministers of India

- Languages of India

- Famous Books and Authors

- List of RBI Governors

- Fathers of Various Fields

- Terminologies in Sports

- Folk Dances of India

- Bird Sanctuary in India

- How To Prepare For Psychology Test In SSB

- What After CDS Exam? CDS SSB Interview Process

- How To Clear NDA SSB Interview

- How To Maintain Physical Fitness For SSB Interview

- SSB Lecturette Tips For Freshers

- SSB Interview Questions, Download PDF

- SSB Day 1 Process, Get Complete Detail Of Day 1

- 25 PPDT Pictures for AFCAT AFSB Interview

IMPORTANT EXAMS

- AFCAT Notification

- AFCAT Admit Card

- AFCAT Eligibility

- AFCAT Syllabus

- AFCAT Salary

- CDS Notification

- CDS Admit Card

- CDS Syllabus

- CDS Eligibility

- NDA Notification

- NDA Syllabus

- NDA Eligibility

- NDA Admit Card

- ICG Notification

- ICG Eligibility

- ICG Selection Process

- ICG Syllabus

Agniveer 2024

- Army Agniveer Notification

- Army Agniveer Syllabus

- Army Agniveer Result

- Army Agniveer Cut Off

- Army Agniveer Eligibility

- Army Agniveer Selection Process

Our Other Websites

- Teachers Adda

- Bankers Adda

- Adda Malayalam

- Adda Punjab

- Current Affairs

- Defence Adda

- Adda Bengali

- Engineers Adda

- Adda Marathi

- Adda School

Welcome to Defence Adda, your one-stop solution to prepare for all Defence Examinations!! Adda247 Defence portal has complete information about all Sarkari Jobs and Naukri Alerts related to defence and its latest recruitment notifications, from all state, grand rush and national level jobs and their updates.

Download Adda247 App

Follow us on

- Responsible Disclosure Program

- Cancellation & Refunds

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- भाषा : हिंदी

- Classroom Courses

- Our Selections

- Student Login

- About NEXT IAS

- Director’s Desk

- Advisory Panel

- Faculty Panel

- General Studies Courses

- Optional Courses

- Interview Guidance Program

- Postal Courses

- Test Series

- Current Affairs

- Student Portal

- Recently, eight cheetahs have landed in Gwalior from Namibia’s capital Windhoek and reintroduced in Kuno National Park . The day also marks PM Modi’s 72nd birthday.

Timeline/ History of cheetah reintroduction in India

- Cheetah or Acinonyx Jubatus : It is the fastest terrestrial animal on earth. The cheetah is the only large carnivore that got completely wiped out from India , mainly due to over-hunting and habitat loss.

- Meaning: The word ‘Cheetah’ is of Sanskrit origin meaning ‘variegated’, ‘adorned’ or ‘painted’.

- They are found in classical Greek records of India , from Strabo, about 200 years before the Common Era.

- In the Mughal Period , cheetahs were used very extensively for hunting. Emperor Akbar had 1,000 cheetahs in his menagerie.

- Central India , particularly the Gwalior region, had cheetahs for a very long time. Various states including Gwalior and Jaipur used to hunt cheetahs.

- The country’s last spotted cheetah died in Sal forests of Chhattisgarh’s Koriya district in 1948 and the wild animal was declared extinct in the country in 1952.

- Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh , the ruler of a small princely state in today’s Chhattisgarh shot India’s last 3 surviving cheetahs.

- The plan was to exchange Asiatic lions for Asiatic cheetahs.

- 2009 : Another attempt to source Iranian Cheetahs was made in 2009 without success. Iran would not permit even cloning of its Cheetahs.

- 2012 : Supreme Court ordered a stay on the reintroduction project.

- 2020: South African experts visited four potential sites: Kuno-Palpur , Nauradehi Wildlife Sanctuary, Gandhi Sagar Wildlife Sanctuary and Madhav National Park.

About the recent translocation programme

- Project Cheetah : The introduction of cheetahs in India is being done under Project Cheetah, which is the world’s first intercontinental large wild carnivore translocation project.

- The Coexistence approach is considered more favourable by social scientists.

- Fencing has proven to be a valuable tool in eliminating cheetahs’ tendency to range over wide distances in South Africa and Malawi, thus allowing for population growth.

- The core conservation area of KNP is largely free of anthropogenic threats.

- Kuno NP will be more challenging, as it is not enclosed / fenced.

- There have been no successful cheetah reintroductions into unfenced systems.

- Anthropogenic threats to cheetah survival include snaring for bush meat and retaliatory killings due to livestock depredation.

- This would place them at the risk of human-related mortality including snaring and retaliatory killings by livestock farmers.

- But these reintroductions were all done in fenced PAs as fencing provides safety from human-animal conflict caused due to cheetahs killing livestock.

Significance of Cheetah reintroduction

- India as historical Cheetah habitat: The Cheetah habitat in India historically is from Jammu to Tamil Nadu , very widespread and they were found in any habitat dry forests, grasslands, scrub forest, etc.

- Pray base: Experts believe that as long as there is enough food and there is protection they will regenerate on their own. A‘prey base’ that can sustain the population and that has already been prepared at the Kuno-Palpur sanctuary.

- Cheetahs will help in the restoration of open forest and grassland ecosystems in India.

- The cheetah is a flagship grassland species ; whose conservation also helps in preserving other grassland species in the predator food chain.

- This will help conserve biodiversity and enhance the ecosystem services like water security, carbon sequestration and soil moisture conservation, benefiting society at large .