Has globalization gone too far—or not far enough?

Subscribe to global connection, shantayanan devarajan shantayanan devarajan nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development @shanta_wb.

September 3, 2019

For developing countries as a whole, globalization—the process of lowering trade barriers and integrating with the world economy—has been enormously beneficial (Figure 1).

Figure 1: GDP growth rates before and after trade liberalization

Note: Red line=average growth rate before (after) trade liberalization, Blue line=growth rate (3-year MA), Dot=growth rate. Source: Wacziarg and Horn Welch (2008).

GDP growth rates have been about 2 percentage points higher after trade liberalization. Investment-to-GDP rates have been almost 10 percentage points higher—and sustained for a long time after liberalization. Moreover, this higher growth has contributed to faster poverty reduction in globalizing countries. And there is no systematic relationship between trade liberalization and inequality. In some globalizing countries inequality rose, while in others it fell.

Why then does globalization elicit so much criticism from NGOs and academics , among others? One reason is that the average growth rates hide a huge variation among individual countries. Among major Latin American countries, for instance, the only country that saw a significant increase in its growth rate post-liberalization was Chile; Brazil and Mexico experienced a decline in their growth rates. Similarly, in Africa, with the exception of Ghana, trade liberalization was accompanied by a decline in average growth rates in many countries. It is only in Asia that most countries have seen an increase in growth rates after liberalization. This includes not just the celebrated cases of India and China, but smaller countries such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines.

Furthermore, in some of the countries where the growth impact was weak, the employment effects were even more troubling. In Brazil , the regions facing tariff cuts experienced significant drops in formal-sector employment and earnings. These effects became more pronounced 20 years after liberalization.

Finally, for trade liberalization to have its intended effect, a host of other factors have to be in place. Africa still has a huge infrastructure deficit, which means that even if there is trade reform, it remains difficult to ship manufactured goods to ports. India has seen very little growth in manufacturing employment—even though it has a large number of low-skilled workers. The level of education of these people is woefully poor: The share of second-graders in rural public schools who could not read a single word was 80 percent .

Do these criticisms imply that globalization has gone too far? On the contrary, they suggest that it has not gone far enough. For the benefits of trade liberalization were not simply the efficiency gains from removing a set of tariff distortions in the economy. Simulations with computable general equilibrium (CGE) models showed that, if this were the only effect, the benefits from trade reform would be minuscule . Trade restrictions did more than add a distortion to a competitive economy. In many cases, they created domestic monopolies that could exercise their monopoly power behind trade protection. Some of these monopolists were also politically connected, which may explain the resistance to trade liberalization in many countries. When the presence of these monopolies is incorporated into a CGE model, the beneficial effects of trade liberalization become much greater . The reason is that trade liberalization subjects these monopolists to foreign competition, breaking down their monopoly power, lowering domestic prices much more (thereby making it cheaper for those who buy these goods), and permitting the exploitation of economies of scale.

But trade liberalization only affected monopoly power in the tradable sector—manufacturing and agriculture. It did nothing to break down the monopolies in the nontradable sector—services such as finance, transport, and distribution. To this day, the services sector remains largely unreformed . Yet, finance, transport, distribution, and business services are necessary inputs into the production of exports, accounting for about 30-40 percent of value-added in exports. If these nontradable services remain monopolized, then it is difficult for the tradable sector to expand in the wake of trade liberalization.

That this is not just a theoretical possibility, I will illustrate with three specific examples.

- Cronyism in Tunisia. Tunisia undertook major trade reforms in the 1990s but export growth remained anemic. This is surprising given Tunisia’s proximity to Europe, fairly good infrastructure, and an educated population. During this same period, the family of the then President, Ben Ali, had interests in certain enterprises. The sectors where these enterprises were situated received protection from both domestic and foreign competition. And these sectors were telecoms, transport, and banking. So the prices of these services were artificially high (Tunisia had the third-highest telecoms prices in the world). Since you need these services to export, Tunisian exports were not competitive in world markets. The monopoly power enjoyed by these firms can be seen in the distribution of profits: The “Ben Ali firms” relative to the rest of the economy accounted for 0.8 percent of employment, 3 percent of output—and 21 percent of profits .

- Roads in Africa . As already mentioned, Africa’s infrastructure deficit stands in the way of harnessing the gains from trade liberalization. But a study of the major road transport corridors in Africa revealed that vehicle operating costs along these four corridors were no higher than in France. What was higher in Africa were transport prices—the highest in the world, in fact. The difference between transport prices and vehicle operating costs is the profit margin accruing to the trucking companies. These margins were of the order of 100 percent. How can this be? Because there are regulations in the books in almost every African country that prohibit entry into the trucking industry. These regulations were introduced a half-century ago when trucking was thought to be a natural monopoly. Today, there is no need for such regulation, but there are huge trucking monopolies in every country that lobby against deregulation. The fact that relatives of the ruling family own the trucking company doesn’t help. Africa’s high transport prices are due to monopoly power in the (nontradable) transport sector, which is in turn standing in the way of the continent’s benefiting from trade liberalization.

- Teachers in India . How is it that second-graders in rural public schools in India can’t read? For about a quarter of the time, the teacher is absent . How can teachers continue to be absent year in and year out? In India, teachers run the campaigns of the local politicians. If the politician gets elected, he turns around and gives the teacher a job for which he doesn’t need to show up. The result is that teachers, being providers of nontradable services, have a small degree of monopoly power that enables them to be absent without major sanctions.

In sum, the reason trade liberalization has not fully delivered on the promise is that only tradable sectors have been subject to international competition. If this competition can be spread to the nontradable sectors, we will see greater competition in those sectors and bigger gains from trade liberalization. The problem with globalization is not that it has gone too far; it’s that it hasn’t gone far enough.

Related Content

Shantayanan Devarajan

January 14, 2016

Vera Songwe

January 11, 2019

November 29, 2017

Emerging Markets & Developing Economies Global Trade

Global Economy and Development

Homi Kharas, Charlotte Rivard

April 16, 2024

Homi Kharas, Vera Songwe

April 15, 2024

Douglas A. Rediker

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Liberalization

TUM School of Governance and Bavarian School of Public Policy, Technical University of Munich

- Published: 10 November 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Liberalization is the removal of barriers to the cross-border movement of capital, goods, and people. Understanding liberalization is central to understanding how governments respond to and shape the global economy. This article reviews the literature on liberalization from a public-goods perspective, where liberalization is seen as benefiting the population as a whole, and from a private-goods perspective, where liberalization benefits a select few. These perspectives are united by questions over who supports liberalization, when liberalization occurs, and how governments liberalize markets. The article further explores the methods and approaches used by American International Political Economy (IPE), represented by articles published in International Organization , and British IPE, represented by articles published in the Review of International Political Economy .

The cross-border movement of capital, goods, and people is central to International Political Economy (IPE). Government policies play a key role in this regard: governments can facilitate or restrict cross-border transactions. Market liberalization—which we understand here as the removal of barriers to cross-border transactions—sets the stage for globalization, but it also shapes the form that globalization takes.

Consequently, studying the sources of liberalization takes a prominent place in IPE. And it offers lessons for political science more broadly. Ultimately, because liberalization is a policy choice by governments, questions about liberalization are questions about government behavior in domestic and international politics and about the relationship between governments and other actors in politics. Research about liberalization contributes to our understanding of distributive politics; the role of power, norms, and ideas; mass political behavior; and institutional theories of politics. And because it addresses cross-border transactions, liberalization touches on questions at the core of our understanding of the state, including control over territorial borders, the domestic economy, and policy autonomy.

A major distinction across work in this research area is what is perceived as the puzzling aspect of liberalization. One perspective views restrictions as puzzling: if liberalization is a public good with broad-based benefits, why do we observe so many market restrictions? Viewing liberalization as a public good is a natural consequence of economic theories, which emphasize the aggregate gains from trade and capital account liberalization, such as lower prices, lower borrowing costs, productivity gains, and technological spillovers. From this perspective, politics explains the maintenance of (inefficient) market restrictions.

A second perspective views liberalization as puzzling and, in more critical approaches, problematic. Liberalization—and especially liberalization in the context of a broader neoliberal reform agenda—is a private good. Liberalization from this perspective benefits a select few and frequently carries significant costs for domestic societies. These two different perspectives are united by an emphasis on collective action problems, corporate influence in politics, and bargaining between states; and by questions over who supports liberalization, when liberalization occurs, and how governments liberalize markets. 1

Liberalization as a Public Good

Viewing liberalization as a public good offers a powerful analytical framework in IPE. The liberalization of trade and capital accounts benefits societies overall, reducing the cost of goods and the cost of borrowing, reducing opportunities for rent-seeking by interest groups and policymakers, and increasing the efficiency of markets. And while liberalization creates winners and losers, in principle the gains could be redistributed to make everyone better off. Yet, because the gains from liberalization are dispersed across voters as consumers, who are a large and diffuse group, public demand for liberalization is weak ( Pareto 1927 ; Olson 1965 ). In contrast, the costs from liberalization are concentrated: with both trade and capital account liberalization, market incumbents lose market shares and may go out of business, providing an incentive to oppose liberalization.

This framework provides a parsimonious model for understanding central cleavages over government policy. Because the framework emphasizes the public goods character of liberalization, and contrasts it with the private goods delivered by market restrictions, it connects readily to other subfields in political science. If trade and financial market liberalization are public goods and hampered by firm influence, for example, political institutions that circumscribe the influence of firms—and special interests more broadly—should lead to liberalization. This argument has implications for our understanding of several dimensions of political institutions. Differences in electoral rules ( Rogowski 1987b ; Nielson 2003 ; Gawande, Krishna, and Olarreaga 2009 ; Mukherjee, Yadav, and Béjar 2014 ), checks and balances ( Mansfield, Milner, and Pevehouse 2007 ), interest group access ( Ehrlich 2007 ), and delegation to politically insulated policymakers ( Lohmann and O’Halloran 1994 ; Gilligan 1997a ) explain patterns of trade and capital account liberalization across countries. Notably, these patterns are reversed for the liberalization of migration policy, where firms tend to benefit from open markets and voters tend to be opposed ( Bearce and Hart 2017 ).

This framework also lends itself to a normative interpretation: processes and institutions that are associated with liberalization can be justified on the basis that they produce public goods, suppress the influence of special interests in politics, and are more representative of (diffuse) voter interests. In particular, liberal political systems and liberal economic policy go hand in hand (Mansfield, Milner, and Rosendorff 2000 , 2002 ; Lake and Baum 2001 ; Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003 ; Phelan 2011 )—offering a powerful narrative behind the simultaneous waves of democratization and liberalization throughout the twentieth century ( Milner and Mukherjee 2009 ).

Moreover, if liberalization is driven by public-goods considerations, government capacity becomes an important variable in explaining why some governments refrain from liberalization despite the perceived benefits: governments may struggle to replace the lost revenue from liberalization because they lack the fiscal capacity to do so ( Richter 2013 ; Queralt 2015 ; Bastiaens and Rudra 2016 ); governments may lack the capacity to implement and enforce liberalization ( Hamilton-Hart 2003 ; Mosley 2010 ; Gray 2014 ; Betz 2019 ); and frictions in the redistribution of the gains from liberalization across groups can undermine the ability of governments to open their markets ( Davis 2020 ).

The public goods framework has additional implications for how governments liberalize their markets. If liberalization is a public good, some governments may have incentives to appear as if they put liberalization in place, while undermining the effects of liberalization on less transparent dimensions. Governments can substitute regulatory and non-tariff barriers, as relatively obscure and complex measures, for tariffs, which are a more easily observable form of trade protection ( Magee, Brock and Young 1989 ; Mansfield and Busch 1995 ; Kono 2006 ). A similar argument explains patterns of capital account liberalization, where de jure liberalization efforts are not accompanied by de facto liberalization ( Quinn, Schindler, and Toyoda 2011 ; Henisz and Mansfield 2019 ). For example, governments can open capital accounts to facilitate capital inflows while forcing foreign entrants to channel credit through domestic banks ( Pepinsky 2013 ) or liberalize capital inflows while restricting outflows ( Pond 2018c ). While governments may have incentives to provide liberalization as a public good, they systematically offset these effects by reaching for compensatory market restrictions that are even costlier to societies than the measures that were removed ( Kono 2006 ).

Liberalization as a public good, but across countries, is also the basis for theories that emphasize the international system ( Lake 1993 ). In Hegemonic Stability Theory, because of collective action challenges, a global hegemon is necessary to provide the public good of maintaining open markets, for example by punishing defectors that would undermine the liberal order ( Krasner 1976 ; Kindleberger 1986 ; Eichengreen 1987 ; Gilpin 2011 ). If open markets increase the wealth of individual states, they also increase the wealth of adversaries. This rationale underpins a large literature on the security externalities of liberalization. Governments should be more open to economic interactions with allies ( Gowa and Mansfield 1993 ; Gowa 1994 ) and with countries with similar interests ( Morrow, Siverson, and Tabares 1998 ), and they may open markets in exchange for security benefits ( Poast 2012 ).

International institutions can sustain international openness even in the absence of a hegemon, thus providing public goods at the international level. The literature offers two broader interpretations of the role of international institutions in liberalization. As a set of rules, international institutions align expectations, coordinate behavior, and empower some actors over others; but international institutions, and bureaucrats associated with them, also have agency of their own, driving policy change, reorienting the political discourse, and exploiting their agenda-setting power.

The seminal work on institutions as a set of rules has shaped the literature in both international political economy and international institutions, and the two fields remain closely aligned ( Keohane 1984 ). By aligning expectations and providing standards for evaluating government behavior, international institutions sustain liberalization once in place ( Simmons 2000 ; Rosendorff 2005 ; Chaudoin 2014 ). By structuring negotiations, international institutions mobilize domestic constituencies and shape bargaining between states ( Davis 2004 ). By providing legitimacy, international institutions also shape the responses of other governments and thus the evolution of liberalization ( Pelc 2010 ; Brewster 2013 ). And as commitment devices, international institutions reduce policy uncertainty, sustaining beliefs about continued market openness and its benefits ( Mansfield and Reinhardt 2008 ; Mansfield and Milner 2018 ).

A second strand of literature ascribes international institutions more agency in driving liberalization. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is an early example in this literature, because international bureaucrats directly negotiate with governments over trade and capital account liberalization in exchange for loans. In terms of who is driving liberalization, this led to a vibrant literature weighing the relative importance of powerful donor countries ( Stone 2002 ; Dreher and Jensen 2007 ; Dreher, Sturm, and Vreeland 2009 ), private creditors ( Gould 2003 ; Broz and Hawes 2006 ), the Fund staff ( Momani 2005 ; Copelovitch 2010 ), and recipient countries ( Vreeland 2003 ). This research agenda presents new questions for those interested in the legitimacy of the international order, and new opportunities for understanding—and questioning—the role of powerful countries and emerging powers in international politics ( Moschella 2009 ; Fioretos 2019 ; Fioretos and Heldt 2019 ).

Increasingly, the literature also turns to other international institutions as independent actors in driving liberalization. In this area, American- and British-style research traditions are starting to see more overlap, both in substance and approach, by emphasizing the ability of international institutions as actors, independent of state interests, to change the discourse over liberalization. Consistent with sociological approaches to institutionalism, liberalization is not (solely) driven by material considerations, but also by what is perceived as appropriate and legitimate.

For example, the UN confers legitimacy to its delegates; UN delegates, in turn, can use their perceived authority to shape rule-making at the World Trade Organization (WTO) ( Margulis 2018 ). Similarly, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) played an active role in the liberalization of capital accounts by shifting the discourse over liberalization, moving beyond what OECD member states had initially envisioned ( Howarth and Sadeh 2011 ). The increasing availability of tools such as text analysis facilitates quantitative studies as well, documenting the role of language and discourse in driving liberalization both through the IMF ( Kaya and Reay 2019 ) and the WTO dispute settlement body ( Busch and Pelc 2019 ). Experience within the rule-based environment of international institutions, such as the WTO, can also lead governments to invest in their institutional capacity, allowing for a more active role of the government in shaping liberalization domestically and at the international level ( Shaffer, Nedumpara, and Sinha 2015 ; Sinha 2016 ).

The public goods framework is also amenable to the role of learning and ideas in explaining the timing and the forms of liberalization. Whether liberalization is perceived as a public good, and to what extent this belief is held and perpetuated, has changed over time. For example, waves of capital account liberalization and closure throughout the twentieth century align with waves of ideology ( Quinn and Toyoda 2007 ). The prevalence of ideas can also explain liberalization at key moments in history. Morrison (2012) documents how Great Britain’s move toward open trade was driven by a shift in the beliefs of key policymakers away from mercantilism and toward Adam Smith’s ideas of liberalism. Thus, the emergence of a new idea was key in explaining this period of globalization. The repeal of the corn laws in Great Britain can likewise be traced to a shift in ideas among political elites ( Schonhardt-Bailey 2006 ). Chwieroth (2007) offers empirical evidence for the role of ideas in explaining capital account liberalization: countries whose policymakers were socialized into neoliberal beliefs through their education tend to have more open capital accounts. Liberalization as a public good also featured prominently in the justification of the Washington Consensus and its underlying neoliberal ideas, which view market openness and deregulation as optimal and envision little role for the state ( Florio 2002 ; Helleiner 2003 , 2019 ).

Moreover, ideas shape the form of liberalization. What is viewed as a legitimate form of market restriction and as the “proper” role of the state changes over time. These waves of ideas result in different policy choices that then persist, explaining the simultaneous presence of seemingly contradictory policies—such as a more active role of government intervention in trade policies for some sectors and not others (Goldstein 1986 , 1988 ). Thus, ideas matter not only for whether governments liberalize their markets, but also how they do so. A prominent example is the pact of embedded liberalism, which emphasizes the role of the government in providing social safety nets to accompany open markets ( Ruggie 1982 ; Hays 2009 )—an idea that is distinct from the paradigms of free trade or fair trade ( Goldstein 1988 ). This pact has faltered in the wake of the global financial crisis as citizens became disillusioned with government intervention and instead associated international integration with job loss and inequality ( Frieden 2019 Ch. 2).

Prior experience—of their own and others—can be an important element in how firms, citizens, and policymakers perceive liberalization. Economic crises, in particular, provide an impetus to change the status quo and to challenge existing paradigms, which may result in a swing toward more or less liberalization ( Florio 2002 ; Brooks and Kurtz 2007 ), even beyond what the change in economic circumstances would warrant ( Widmaier, Blyth, and Seabrooke 2007 ).

The broad-scale liberalization in response to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act and the Great Depression, and the increasing legitimacy of capital controls in response to the Great Recession, are perhaps the most notable examples of changes brought about by crises ( Chwieroth 2013 ; Grabel and Gallagher 2014 ). But similar patterns emerge for smaller crises, and economic difficulties more generally, as well. A tightening of global credit conditions may promote liberalization if governments seek access to capital from abroad ( Haggard and Maxfield 1996 ; Betz and Kerner 2016b ). Policymakers may also use liberalization during crises to reassure citizens and markets that they are implementing sound economic policies, reinforcing the perception that liberalization is a public good ( Mansfield and Milner 2018 ).

If the experience of other countries informs the perception of economic policies, liberalization may diffuse across countries. Simmons and Elkins (2004) observe that policies of liberalization cluster in specific regions at specific times, spread by two mechanisms. First, the benefits of liberalization are larger when other countries also have open markets. Second, market openness in one country provides information about the costs and benefits of openness to that country’s peers. Both processes are consistent with the policies of liberalization that we observe. The process may also be contingent on domestic political institutions ( Steinberg, Nelson, and Nguyen 2018 ) and on the performance of the countries implementing the reforms ( Brooks and Kurtz 2007 ).

Of course, ideas can be contested. Despite a growing overlap between American- and British-style IPE in their interest in ideas, only the latter approach emphasizes the role of ideas in perpetuating existing power relationships. In particular, and reminiscent of work by Gramsci, the very idea that liberalization is a public good might be perpetuated by elites that benefit from liberalization. Political elites have constructed a discourse over liberalization that tried to obscure the costs for societies ( Siles-Brügge 2014 ). Some governments might want to give the appearance of adhering to established ideas like the Washington Consensus while in fact returning to market intervention ( Ban and Blyth 2013 ). Ideas also matter for the choice among conflicting goals, which in turn may dictate policy choices. Blyth and Matthijs (2017) identify two broad macro-regimes throughout the twentieth century—one centered on full employment, one centered on price stability—and show how adherence to each of these regimes had consequences for the liberalization of individual policies.

The public goods framework thus speaks to several important debates and provides a clear analytical framework for understanding liberalization. At the same time, the public goods framework, which emphasizes the price effects of market restrictions, is at odds with other empirical regularities, especially on trade politics. 2 While Baker ( 2003 , 2005 ) documents that support for free trade in Latin America is driven by consumption effects, voters in other countries—and in particular in the most open countries—appear unaware of, and unmoved by, some of the benefits of market liberalization, especially when it comes to diffuse gains like the price effects of liberalization ( Hiscox 2006 ; Naoi and Kume 2015 ; Bearce and Moya 2020 ). The low salience of trade issues in elections further casts doubt on some aspects of voter- and public goods-driven models ( Guisinger 2009 ), as do findings that many voters evaluate liberalization on non-material dimensions, including nationalism and in-group favoritism, or are driven by social networks rather than economic self-interest ( Tsygankov 2000 ; Mansfield and Mutz 2009 ; Ahlquist, Clayton, and Levi 2014 ; Pandya and Venkatesan 2016 ; Guisinger 2017 ; Mutz and Kim 2017 ; Mansfield, Mutz, and Brackbill 2019 ).

Moreover, there is little evidence that policymakers liberalize markets with an eye toward price effects. Tariffs are highest on those products where tariffs have the largest price effects. In democracies in particular, price considerations do not appear to drive trade liberalization: Tariffs are higher on consumption products than on other products, and this effect is strongest in democracies. Democratization, in turn, has smaller effects on tariff reductions for consumption products than for other goods, suggesting that price effects and consumer interests do not explain trade liberalization( Betz and Pond 2019 ). Moreover, early forms of democratization in India led to protectionism, not free trade ( Gaikwad and Casler 2019 ).

On the one hand, these findings might be interpreted as evidence of collective action problems and informational asymmetries ( Rho and Tomz 2017 ), which could be remedied if voters were more informed. Such an argument also explains different political dynamics across trade and capital account liberalization, based on differences in relative political salience ( Brooks and Kurtz 2007 ).

On the other hand, these findings raise questions about the political forces that drive liberalization: if voters are unaware of the benefits of liberalization and frequently opposed to it, why would accountable and representative policymakers implement liberalization? The belief, based on economic models, that voters should value liberalization, and that any resistance to liberalization could be overcome with better information and more redistribution, led parts of this literature to underestimate the costs of liberalization for societies and the eventual resistance this might cause. The severity of the backlash to liberalization in advanced countries over the past decade, driven by the often persistent costs of liberalization ( Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2013 ; Colantone and Stanig 2018 ), has caught parts of this literature by surprise.

The contrast with more critical approaches to liberalization—which question, for example, the motives behind neoliberal reform agendas in the 1990s—is also pronounced. Focusing on the discourse over liberalization, Fairbrother (2010) observes that policymakers tend to focus on the benefits for producers, rather than for consumers and societies overall, which raises doubts over explanations that view liberalization as driven by public good considerations. And while liberalization can have substantial economic benefits, the distribution of those benefits is at times biased against voters as employees ( Dean 2016 ) and toward high-income countries with high-quality market institutions ( Wade 2010 ; Levchenko 2007 ).

Additionally, capital account liberalization can impose substantial constraints on governments, partially offsetting the gains ( Lindblom 1977 ; Andrews 1994 ). While liberalization can have attributes of a public good, making societies better off overall, it may come at the cost of giving up other public goods, such as policy autonomy ( Li and Smith 2002 ; Arel-Bundock 2017 ) or environmental protection ( Bechtel, Bernauer, and Meyer 2012 ). The public goods character of liberalization may be undermined if the policy constraints imposed by liberalization benefit political elites that fear redistribution in the future ( Pond 2018a ). Perhaps surprisingly, liberalization of migrant flows can reduce constraints on policymakers, by allowing potential political dissidents to leave ( Hirschman 1970 ; Gehlbach 2006 ; Clark, Golder, and Golder 2017 ; Sellars 2018 ). Liberalization also may necessitate public spending to maintain support for openness, putting dual strains on governments ( Flores and Nooruddin 2016 ; Bastiaens and Rudra 2018 ). Others have emphasized multinational corporations (MNCs), especially from the US and Western Europe, as the prime beneficiaries of liberalization, often in opposition to consumers and voter groups ( Young 2016 ). As we note in the next section, the turn toward firm-level accounts of liberalization in recent years led to a new convergence between American- and British-style IPE.

Liberalization as a Private Good

A second view of liberalization, reaching back at least to Schattschneider (1935) , emphasizes the distributional conflict created by trade and capital account liberalization. Drawing on theories of comparative advantage, a large part of this literature focuses on whether the political cleavages over these policies fall along class lines, following the Heckscher-Ohlin model, or along industry lines, following the Ricardo-Viner model ( Schattschneider 1935 ; Rogowski 1987a ; Frieden 1991 ). Which of the two cleavages is more prevalent at any given point in time can be explained by differences in factor mobility ( Hiscox 2002 ; Ladewig 2006 ): when labor is mobile across sectors, the Heckscher-Ohlin model provides a better explanation of political conflict. Immigration can also be viewed through this lens, where restrictions benefit unskilled labor in developed countries, but hurt unskilled labor in developing countries ( Milanovic 2011 ).

These models explain several empirical patterns in the liberalization of trade and capital accounts. For example, whether industries are able to block liberalization depends on their geographic features. Political influence is largest for industries that are dispersed across electoral districts but concentrated geographically (Busch and Reinhardt 1999 , 2005 ), and this effect in turn depends on a country’s electoral rules ( McGillivray 2004 ; Rickard 2012 ). In a class-based model, partisanship moves to the forefront: if political parties align with economic classes, the support of left-wing parties for liberalization depends on whether labor is a relatively abundant or scarce factor ( Quinn and Inclan 1997 ; Li and Smith 2002 ; Milner and Judkins 2004 ; Pinto 2013 ). Similar arguments apply to democratic institutions, which should reduce the political influence of capital owners, relative to labor, in driving trade and capital account liberalization ( Milner and Kubota 2005 ; Kono 2006 ; Pandya 2014 ). Some work emphasizes how these theories interact with the global spread of ideas ( Quinn and Toyoda 2007 ; Steinberg, Nelson, and Nguyen 2018 ).

When explaining trade liberalization, and in contrast to models of trade liberalization as a public good, many of these models implicitly build on the norm of reciprocity. Reciprocity, together with most favored nation and national treatment, is one of the key elements underlying the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the WTO and most preferential trade agreements. With reciprocal trade agreements, export-oriented factor owners, industries, or firms support liberalization at home when it gives them access to markets abroad ( Bailey, Goldstein, and Weingast 1997 ; Gilligan 1997a ; Pahre 2008 ; Betz 2017 ). This form of issue linkage has overcome some of the most entrenched resistance to liberalization, such as that from the agricultural sector in many countries ( Davis 2004 ). 3

Mirroring developments in other subfields of political science, international political economy has increasingly turned to more granular theories and data. Over the past two decades, economists have documented that few individual firms engage in international economic transactions, that the gains from openness are concentrated on these firms, and that liberalization induces substantial reallocations across firms within industries ( Bernard and Jensen 1999 ; Melitz 2003 ; Bernard et al. 2007 ; Goldberg and Pavcnik 2007 ; Freund and Pierola 2015 ; Bernard et al. 2018 ). This led to a surge of interest in individual-level and firm-level accounts of liberalization.

These studies point to substantial differences across firms within industries, rather than differences across industries or across classes. Firms differ in production technologies, access to inputs from abroad, and access to production networks, and as a consequence differ in their ability to engage with foreign markets: only the largest and most productive firms can afford the fixed costs of entering foreign markets and establishing global production networks, resulting in concentrated gains from trade and capital account liberalization. Moreover, the gains from liberalization are not only concentrated on few firms, but on firms that have political influence.

Plouffe (2015) provides an early overview of a firm-based model of trade politics. Subsequent work elaborated several implications. Within-industry conflict and firm-level lobbying for trade liberalization are more pronounced in industries with higher levels of intra-industry trade ( Madeira 2016 ), challenging a more harmonious view of intra-industry trade (for a review see, e.g., Gilligan 1997b ). Other work has built on a firm-based model to explain the creation and management of supply chains ( Dallas 2015 ), intra-industry divisions in public position-taking ( Osgood 2016 ), firm attitudes ( Plouffe 2017 ), lobbying for trade liberalization ( Kim 2017 ), and the institutional sources of trade policy ( Betz 2017 ). Early precursors to these studies are Milner (1988b) , who emphasizes the international ties of individual firms within industries as a source of opposition to protectionism, and Chase (2004b) , who documents that smaller firms are more protectionist than larger firms and relates these differences to cross-country differences in trade policy. The contrast between the liberalization of tariffs and non-tariff barriers is emphasized by Gulotty (2020) . Because only the largest firms can overcome the fixed costs created by non-tariff barriers (such as adjusting to new labeling requirements), the very firms that tend to benefit from, and drive, the liberalization of tariffs also support restrictions in the form of non-tariff barriers.

Recent work also builds on firm-based models to explain capital account liberalization, for example with different financing constraints across firms ( Leiteritz 2012 ; Danzman 2019 ). This understanding of the drivers of liberalization also speaks to some of the dynamics of liberalization over time: once a market is sufficiently competitive, governments have little reason to maintain barriers to international trade and capital flows, facilitating a “juggernaut” effect toward further liberalization ( Hathaway 1998 ; Rajan and Zingales 2003 ; Brooks 2004 ; Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud 2008 ; Pond 2018b ), but also increasing the resistance to initial attempts at liberalization ( Davis 2015 ).

Fusing the granularity of trade policy with a firm-based model in the context of trade agreements reverses the collective action arguments outlined above: liberalization not only provides diffuse gains for the public, but also concentrated gains for individual, politically powerful firms—which leads to new implications for the institutional theories of liberalization outlined in the previous section ( Goldstein and Gulotty 2014 ; Betz 2017 ; Betz and Pond 2019 ). Liberalization, from the perspective of a firm-based model, need not be driven by a higher regard for voter interests or the insulation of policymakers from special interests. Consistent with the growing discontent with liberalization among citizens in developed countries, liberalization may happen not because of, but despite, what citizens and societal groups prefer. Firms may lobby for the liberalization of trade and capital accounts, but they are not doing the bidding of voters in providing public goods—the shape that liberalization takes differs in its timing, in its product coverage, in its trade partners, and in its choice of policy instruments from what voters may have preferred. The largest firms emerge as the main beneficiaries of the liberalization of trade and capital accounts, and of the international rules that have contributed to that liberalization.

The gains from liberalization for individual firms, and the role of individual firms in IPE, has always had a prominent place in British-style IPE ( Stopford, Strange, and Henley 1991 ; Strange 1996 ; Cohen 2008 ; Rutland 2013 ). The turn to firm-based models has thus resulted in a new alignment in themes between American- and British-style IPE, and a growing consensus that trade and capital account liberalization during the twentieth century were shaped by large, politically powerful firms, sometimes in opposition to voters. Additionally, the content of liberalization efforts appears to be tilted toward powerful Western countries and their “domestic” MNCs ( Wade 2010 ). The imbalance between countries is also evident in the dispute settlement body of the WTO, although it appears that the rule-based system of the dispute settlement body has reduced at least some of the power asymmetries between countries ( Sattler and Bernauer 2011 ).

Driven by advances in transportation and information technology, production processes are now not only geographically separated from the location of consumers, but the different stages of production have also disintegrated across firms and across countries ( Baldwin 2016 ). The emphasis on the largest firms as the beneficiaries of openness thus moved MNCs, global production processes, and global supply chains, which featured prominently in earlier literature ( Vernon 1971 ; Moran 1978 ; Cox 1987 ; Milner 1988 a ; Milner and Yoffie 1989 ; Goodman and Pauly 1993 ), back to the forefront in explaining liberalization: in addition to exporting and import-competing firms, importing firms play an important role in the politics over trade and capital account liberalization. This has the potential to substantially reshape political responses to external financial conditions ( Jensen, Quinn, and Weymouth 2015 ; Weldzius 2020 ), patterns of trade liberalization (Manger 2005 , 2012 ; Baccini, Dür, and Elsig 2018 ; Anderer, Dür, and Lechner 2020 ), and the role of individual firms in the creation and governance of international economic flows ( Dallas 2015 ; Gaubert and Itskhoki 2018 ).

Viewing liberalization as a private good also offers a framework for understanding the timing and the shape of liberalization. Diffusion explains liberalization by spreading the perception that liberalization is a public good, as discussed in the previous section. Diffusion also accounts for liberalization, however, through competition effects. If firms from other countries gain access to new markets—through capital account and trade liberalization—it puts domestic firms at a relative disadvantage. Thus, liberalization between pairs of countries, by discriminating against outsiders, triggers demands for liberalization by firms located in those outsiders: they seek to prevent a deterioration in relative terms for their firms’ exports ( Dür 2010 ) and for their firms’ investment ( Manger 2009 ).

Liberalization among groups of countries, most prominently in the European Union (EU), implies a relative increase in market restrictions for firms from outside the arrangement ( Limão 2006 ). This aspect of regionalism is frequently by design, because it helps governments build political coalitions ( Chase 2004a ). Whether regionalism provides a “stumbling block” or a “stepping stone” to further liberalization remains a largely open question ( Mansfield and Milner 1999 ). Multilateralism itself is subject to similar challenges ( Goldstein et al. 2000 ). Gowa and Hicks (2012) show how governments have used the most favored nations clause in a discriminatory fashion, creating private goods for individual countries. Even in the relatively legalized environment of the WTO’s dispute settlement body, governments frequently strike settlements that disadvantage third countries ( Kucik and Pelc 2016 ). Moreover, trade barriers by foreign governments are more likely to get challenged if they impose concentrated costs: trade disputes that provide public goods across countries are less readily initiated, shaping patterns of liberalization across countries and across products ( Johns and Pelc 2018 ).

That liberalization can also have protectionist undertones is a common theme in a larger body of literature on how governments liberalize. Governments typically do not liberalize their markets across the board. They tailor tariffs to individual products and drive up the variance in tariff rates across products ( Goldstein and Gulotty 2015 ; Kim 2017 ; Betz 2017 , 2019 ), insert content requirements that limit the scope of liberalization ( Chase 2008b ), target trade liberalization toward some countries but not others ( Kono 2008 ; Barari, Kim, and Wong 2020 ), limit migration for low-skilled but not high-skilled workers ( Peters 2015 ), and open their capital accounts toward investment inflows but restrict outflows ( Pond 2018c ). These forms of partial liberalization facilitate the creation of political coalitions and may help governments accommodate competing demands. But they also open room for arbitrage, corruption, and evasion. The resulting policy complexity may ultimately depress the effects of liberalization efforts, in some environments intentionally so ( Wu 2020 ).

The redistributive character of liberalization also motivates a growing body of literature that seeks to understand the relationship between different policy choices. With open capital accounts, exchange rate movements have clear implications for domestic groups: currency appreciation aids consumers and importing firms, but hurts import-competing firms and exporting firms ( Frieden 1991 ). Consequently, currency appreciation is associated with an increase in both protectionist demands at home ( Broz and Werfel 2014 ) and attempts to remove trade barriers abroad ( Betz and Kerner 2016a ). Conversely, where trade agreements restrict a government’s trade policy choices, monetary policy autonomy becomes more attractive to governments ( Copelovitch and Pevehouse 2013 ). Notably, Jensen, Quinn, and Weymouth (2015) show how the presence of MNCs, as politically powerful importing firms, breaks the otherwise clear link between external financial conditions and trade policy.

Recent work looks more comprehensively at the relationship between trade liberalization, capital account liberalization, and migration policy. Once trade and capital account liberalization allowed US firms to produce goods abroad and import them back to the US, firms no longer required low-cost labor within the US ( Peters 2014 ). This resulted in less support for open immigration policies from firms, increased influence of nativist forces, and more restrictive immigration policy. Thus, the liberalization of trade and capital flows substitutes for the liberalization of migration. These findings point to the need to consider the relationship between different dimensions of liberalization, and how governments address competing demands over liberalization. Examples include the inclusion of labor rights and environmental standards in trade agreements, which may be interpreted as a form of non-tariff barrier to reduce the extent of de facto liberalization ( Lechner 2016 ) and which may substitute for compensatory government spending ( Bastiaens and Postnikov 2020 ).

New areas of overlap between different research traditions emerge in questions about the mass politics over liberalization and the role of material interests in explaining voter attitudes. The emphasis on production networks and modes of production in British IPE, most prominently articulated by Cox (1987) , is increasingly mirrored in work that is more closely aligned with American IPE as well. It is well established that highly educated voters in the US tend to be more supportive of trade liberalization. This may be interpreted as evidence of a factor-based model ( Scheve and Slaughter 2001 ). Yet, contrasting with a factor-model, but consistent with research on the distributional consequences of trade liberalization based on firm-based models and in models that emphasize the skill-bias in international trade ( Goldberg and Pavcnik 2007 ; Bustos 2011 ), similar empirical patterns are evident in Argentinean surveys ( Ardanaz, Murillo, and Pinto 2013 ). This finding suggests that mass attitudes may be better explained by the skill bias inherent in trade and capital account liberalization ( Li and Smith 2002 ; Menendez, Owen, and Walter 2018 ; Palmtag, Rommel, and Walter 2020 ). Recent work also examines the role of individual occupations in explaining attitudes over liberalization. Occupations that require few context-specific skills can be relocated abroad relatively easily, creating new cleavages over liberalization based on occupation, which cut across industry and class lines ( Chase 2008a ; Owen and Johnston 2017 ; Owen 2017 ).

Education may also shape attitudes by providing individuals with information about the gains from trade and through socialization, which explains voter attitudes toward both trade ( Hainmueller and Hiscox 2006 ) and migration ( Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007 ; Hainmueller, Hiscox, and Margalit 2015 ). That voters may have limited knowledge of the distributional consequences of liberalization suggests that they are susceptible to informational cues, socialization effects, and framing effects ( Hiscox 2006 ; Ahlquist, Clayton and Levi 2014 ; Naoi and Kume 2015 ; Rho and Tomz 2017 ; Bearce and Moya 2020 ). Consequently, the discourse over liberalization matters for building support for liberalization. Blending constructivist approaches with firm-based models of trade, Skonieczny (2018) documents how pro-trade firms use national identity narratives, rather than arguments about material gains, to shape public support for trade liberalization. In part driven by recent elections in the US and the UK, this research agenda suggests new questions not just about who supports liberalization, but the ideological sources and the cohesion of political coalitions. How individual firms and interest groups succeed in building public support for trade liberalization, sometimes in opposition to (perceived) material interests, is a question of increasing political relevance.

Journal Articles

In this review article, we developed two frameworks for understanding liberalization, stressing either the public- or private-good effects of liberalization. In doing so, we attempted to bridge many divisions in IPE. Nevertheless, the conventional wisdom expects a divide between American- and British-style IPE: American IPE is oriented toward abstract theory and generalizability across cases, as well as economic methodologies and identification of causal effects. British IPE alternatively emphasizes deep understandings of subject matter in relatively few units and is more open to exploring topics, like power, intentions, and hierarchy, that might challenge traditional forms of empirical inference (see Cohen 2008 for a discussion of the development of both traditions).

To evaluate the extent of division in the literature, we tasked two graduate students to collect the literature on “liberalization” in International Organization ( IO ), frequently associated with American-style IPE, and Review of International Political Economy ( RIPE ), representing the British tradition. 4 They collected 352 articles, 212 from RIPE and 140 from IO , from 2000 to 2019. They then coded each article depending on the topic, emphasis of the study, and the methods used.

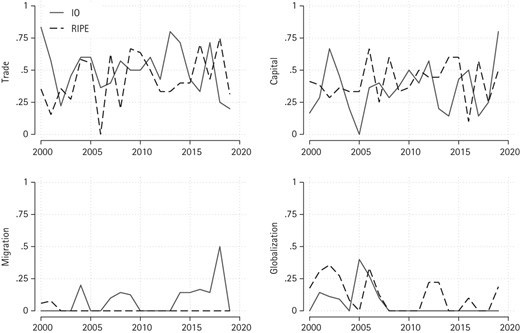

The topics we identified are trade, capital, migration, or globalization. Globalization captures studies that consider the drivers of increased integration, writ large, rather than any specific type of economic flow—the vast majority are studies of trade and capital liberalization. We fit each article into a single category; the categories are thus mutually exclusive.

Figure 1 depicts the share of articles in each issue area over time for both IO and RIPE . The overwhelming majority of the studies in both journals emphasize trade or capital flows only. Migration seems slightly more common in IO while studies of globalization as a broad phenomenon appear more commonly in RIPE . This is consistent with a general emphasis on power, hierarchy, and the constraints posed by international economic integration in the British tradition ( Strange 1996 ).

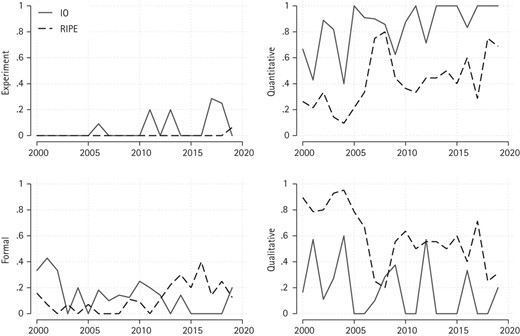

We then coded the papers by the methodology used, including qualitative, quantitative, formal models, or experimental designs. 5 Because a single paper could use multiple different methods, these categories are not mutually exclusive. Figure 2 depicts the share of articles using each method over time. Consistent with anecdotal claims, there seems to be a preference for quantitative methods in IO and for qualitative methods in RIPE —although quantitative methods are becoming increasingly common in both journals. Formal and experimental approaches to liberalization are relatively uncommon.

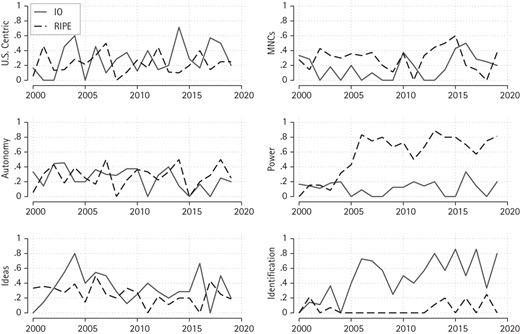

Finally, we attempted to identify the emphasis in each study. We coded whether each study emphasized the role of the US, MNCs or firms, policy autonomy, state power, ideas, and whether a concern for (causal) identification was mentioned. 6 Any one study could again fit into multiple categories, for example using an instrumental variables approach to explore the influence of US MNCs in eroding state autonomy. Figure 3 depicts the trends in emphasis over time. The largest differences appear over power and identification. Articles in RIPE more frequently reference power while articles in IO are more likely to discuss the identification strategy—consistent with the perception that American IPE has moved toward research that addresses smaller questions in a rigorous way. The influence of firms over liberalization appears earlier in RIPE than in IO .

Some other differences between the different research traditions stand out. In contrast to main themes in British IPE, American IPE frequently shies away from normative assessments—despite its reliance on frameworks from economics, a discipline heavily reliant on normative comparisons like “welfare analysis.” American IPE also tends to take existing institutions and power structures as given, rather than questioning their legitimacy or origins.

At the same time, we perceive increasing areas of overlap between British and American IPE. Some of these are driven by methodological innovations, which have allowed American IPE to approach topics usually more central to British IPE. The emergence of text analysis allows for the quantitative assessment of language and discourse; similarly, network models and increasingly granular data made the relations between actors, a central issue in British IPE, amenable to quantitative analyses by those in the tradition of American IPE. Put (perhaps too) simply, by being able to measure things that were previously not quantifiable, those working in American IPE can now address topics that were previously the purview of British IPE. Overlap also arises from policy debates and on substantive grounds, such as the concern with globalization backlash and the often substantial adjustment costs to liberalization.

Share of articles in IO and RIPE, by topic.

Share of articles in IO and RIPE, by method.