Teaching & Learning

- Education Excellence

- Professional development

- Case studies

- Teaching toolkits

- MicroCPD-UCL

- Assessment resources

- Student partnership

- Generative AI Hub

- Community Engaged Learning

- UCL Student Success

Oral assessment

Oral assessment is a common practice across education and comes in many forms. Here is basic guidance on how to approach it.

1 August 2019

In oral assessment, students speak to provide evidence of their learning. Internationally, oral examinations are commonplace.

We use a wide variety of oral assessment techniques at UCL.

Students can be asked to:

- present posters

- use presentation software such as Power Point or Prezi

- perform in a debate

- present a case

- answer questions from teachers or their peers.

Students’ knowledge and skills are explored through dialogue with examiners.

Teachers at UCL recommend oral examinations, because they provide students with the scope to demonstrate their detailed understanding of course knowledge.

Educational benefits for your students

Good assessment practice gives students the opportunity to demonstrate learning in different ways.

Some students find it difficult to write so they do better in oral assessments. Others may find it challenging to present their ideas to a group of people.

Oral assessment takes account of diversity and enables students to develop verbal communication skills that will be valuable in their future careers.

Marking criteria and guides can be carefully developed so that assessment processes can be quick, simple and transparent.

How to organise oral assessment

Oral assessment can take many forms.

Audio and/or video recordings can be uploaded to Moodle if live assessment is not practicable.

Tasks can range from individual or group talks and presentations to dialogic oral examinations.

Oral assessment works well as a basis for feedback to students and/or to generate marks towards final results.

1. Consider the learning you're aiming to assess

How can you best offer students the opportunity to demonstrate that learning?

The planning process needs to start early because students must know about and practise the assessment tasks you design.

2. Inform the students of the criteria

Discuss the assessment criteria with students, ensuring that you include (but don’t overemphasise) presentation or speaking skills.

Identify activities which encourage the application or analysis of knowledge. You could choose from the options below or devise a task with a practical element adapted to learning in your discipline.

3. Decide what kind of oral assessment to use

Options for oral assessment can include:

Assessment task

- Presentation

- Question and answer session.

Individual or group

If group, how will you distribute the tasks and the marks?

Combination with other modes of assessment

- Oral presentation of a project report or dissertation.

- Oral presentation of posters, diagrams, or museum objects.

- Commentary on a practical exercise.

- Questions to follow up written tests, examinations, or essays.

Decide on the weighting of the different assessment tasks and clarify how the assessment criteria will be applied to each.

Peer or staff assessment or a combination: groups of students can assess other groups or individuals.

4. Brief your students

When you’ve decided which options to use, provide students with detailed information.

Integrate opportunities to develop the skills needed for oral assessment progressively as students learn.

If you can involve students in formulating assessment criteria, they will be motivated and engaged and they will gain insight into what is required, especially if examples are used.

5. Planning, planning planning!

Plan the oral assessment event meticulously.

Stick rigidly to planned timing. Ensure that students practise presentations with time limitations in mind. Allow time between presentations or interviews and keep presentations brief.

6. Decide how you will evaluate

Decide how you will evaluate presentations or students’ responses.

It is useful to create an assessment sheet with a grid or table using the relevant assessment criteria.

Focus on core learning outcomes, avoiding detail.

Two assessors must be present to:

- evaluate against a range of specific core criteria

- focus on forming a holistic judgment.

Leave time to make a final decision on marks perhaps after every four presentations. Refer to audio recordings later for borderline cases.

7. Use peers to assess presentations

Students will learn from presentations especially if you can use ‘audio/video recall’ for feedback.

Let speakers talk through aspects of the presentation, pointing out areas they might develop. Then discuss your evaluation with them. This can also be done in peer groups.

If you have large groups of students, they can support each other, each providing feedback to several peers. They can use the same assessment sheets as teachers. Marks can also be awarded for feedback.

8. Use peer review

A great advantage of oral assessment is that learning can be shared and peer reviewed, in line with academic practice.

There are many variants on the theme so why not let your students benefit from this underused form of assessment?

This guide has been produced by the UCL Arena Centre for Research-based Education . You are welcome to use this guide if you are from another educational facility, but you must credit the UCL Arena Centre.

Further information

More teaching toolkits - back to the toolkits menu

[email protected] : contact the UCL Arena Centre

UCL Education Strategy 2016–21

Assessment and feedback: resources and useful links

Six tips on how to develop good feedback practices toolkit

Download a printable copy of this guide

Case studies : browse related stories from UCL staff and students.

Sign up to the monthly UCL education e-newsletter to get the latest teaching news, events & resources.

Assessment and feedback events

Funnelback feed: https://search2.ucl.ac.uk/s/search.json?collection=drupal-teaching-learn... Double click the feed URL above to edit

Assessment and feedback case studies

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Students’ Oral Presentation as Multimodaland Formative Assessment

Abstract: The pervasiveness of digital media technologies has significantly shifted the notion of teaching and language learning. This also affects how teachers design particular assessment for students’ learning process in a multimodal environment of the contemporary classroom. However, the construction of multimodal assessment and its effects on students’ learning outcomes particularly on their oral performance is still inconclusive. Taking into account Wiliam’s (2011) strategies for successful formative assessment practice and the advancement of Computer-mediated Communication (CMC) use in learning, this paper illustrates the emergence of students’ oral presentation as multimodal assessment in language classrooms particularly at tertiary level, and provides insights for teachers to design and develop a rubric for assessment. Specifically, this paper argues that despite its challenges in classroom practice, this alternative assessment can be used to assess students’ multimodality ...

Related Papers

English Teaching: Practice and Critique

This article explores the emergence of multimodality as intrinsic to the learning, teaching and assessment of English in the Twenty-First Century. With subject traditions tied to the study of language, literature and media, multimodal texts and new technologies are now accorded overdue recognition in English curriculum documents in several countries, though assessment tends to remain largely print-centric. Until assessment modes and practices align with the nature of multimodal text production, their value as sites for inquiry in classroom practice will not be assured. The article takes up the question: What is involved in assessing the multimodal texts that students create? In exploring this question, we first consider central concepts of multimodality and what is involved in “working multimodally” to create a multimodal text. Here, “transmodal operation” and “staged multimodality” are considered as central concepts to “working multimodally”. Further, we suggest that these concepts...

English Teaching: Practice and …

ABSTRACT: This article explores the emergence of multimodality as intrinsic to the learning, teaching and assessment of English in the Twenty-First Century. With subject traditions tied to the study of language, literature and media, multimodal texts and new technologies are ...

Kate Anderson

Purpose-This article presents an analysis of empirical literature on classroom assessment of students' multimodal compositions to characterize the field and make recommendations for teachers and researchers. Design/methodology/approach-An interpretive synthesis of the literature related to practices and possibilities for assessing students' multimodal compositions. Findings-Findings present three overarching types of studies across the body of literature on assessment of student multimodal compositions: reshaping educational practices, promoting multiliteracies approaches to learning and evaluating students' understanding and competence. These studies' recommendations range along a continuum of more to less structural changes to "what counts" in classrooms. Research limitations/implications-This review only considers studies published in English from 2000to 2019. Future studies could extend these parameters. Practical implications-This analysis of the literature on assessing student multimodal compositions highlights foundational differences across studies' purposes and offers guidance for educations seeking to revise their practices, whether their goals are more theoretical/philosophical, oriented toward reshaping classroom practice or focused on ways of measuring student understanding. Social implications-Rethinking assessment can reshape educational practices to be more equitable, more theoretically commensurate with teachers' beliefs and/or include more thorough and accurate measures of student understanding. Changes to any or all of these facets of educational practices can lead to continued discussion and change regarding the role of multimodal composition in teaching and learning. Originality/value-This study fills a gap in the literature by considering what empirical studies suggest about why, how and what to assess with regard to multimodal compositions. Introduction Attention to multimodal compositions in the field of English Education has proliferated over recent decades. Multimodality-meaning making and texts that incorporate multiple modes, or different channels of communication-is a hallmark of learners' practices (both in and out of schools) with screen-based multimodal texts (e.g. videos, videogames) and non-digital forms (e.g. signs, collages, live performances). Many studies have discussed the benefits of students' multimodal composition, or the creation of texts (broadly defined) using multiple Students' multimodal compositions

Shakina Rajendram

This article presents the results of a review of published literature on the use of the multiliteracies pedagogy to teach English Language Learners (ELLs). A total of 12 studies were selected for the literature review based on three inclusion criteria: (1) studies using the multiliteracies framework or other aspects of the multiliteracies pedagogy such as multimodality; (2) studies with ELL participants; and (3) studies conducted within the last 10 years. Through a detailed review and analysis of these studies, five emerging themes related to the potential benefits of the multiliteracies approach were identified and discussed in this article: (i) student agency and ownership of learning; (ii) language and literacy development; (iii) affirmation of students' languages, cultures and identities; (iv) student engagement and collaboration; and (v) critical literacy.

María Martínez Lirola

Our society has become more technological and multimodal, and consequently teaching has to be adapted to the demands of society. This article analyses the way in which the subject English Language V of the English Studies degree at the University of Alicante combines the development of the five skills (listening, speaking, reading, writing and interacting) evaluated through a portfolio with multimodality in the teaching practices and in each of the activities that are part of the portfolio. The results of a survey prepared at the end of the 2015–16 academic year show the main competences that university students develop thanks to multimodal teaching and the importance of tutorials in this kind of teaching.

Peter Smagorinsky

Emily Howell , David Reinking , Rebecca Kaminski

IATED 2017 Proceedings

Raquel Bambirra , Valéria Valente , Marcos Racilan

This paper presents a research that focused on raising students’ awareness of the main characteristics of a textual genre to support its written production in English at a secondary public school in Brazil. Based on the pedagogy of multiliteracies, this study promoted the collaborative and process writing of campaigns against animal abuse by 104 first-year students from five classes organized in groups of four. In the pre-writing phase, the students reflected on animal rights and critically analyzed some samples of campaigns on the same subject using a checklist containing the main characteristics of this textual genre. Elaborated collectively and piloted for some years by several teachers at this school, this instrument was also used both to guide the writing process and to subsidize the evaluation of the final production. Next, the groups chose a circumstance involving animal abuse to be the focus of their campaigns and organized their ideas in a conceptual map. Throughout the writing process, the students searched the internet for images, looked up words in print and online dictionaries, used text and image editors, and created logos on a website in order to indicate the authorship of the campaigns. During the rewriting phase, the teacher went from group to group giving feedback. Finally, the post-writing phase involved the production of a set of slides that documented the groups’ reflections on the production of their campaigns and served as support for the oral presentation of their work. The campaigns made by the students are rich in multimodal resources, what shows their creativity in meaning making. It was possible to notice that they developed their levels of autonomy and critical literacy by investing in a collaborative work that demanded intense negotiation. By having mediated the whole process, the checklist was essential for the students to become aware of the characteristics of a campaign, what assured the quality of their productions. Keywords: campaign, multiliteracies, textual genre characteristics, process writing, checklist.

Journal of Computers in Education

Anna Åkerfeldt

Finita Dewi

The proposed study is an attempt to respond to the demands of todays' EFL teaching which should start to move away from focusing on the teaching of language skills only to preparing learners for different literacy practices they might encounter in their future involving visual, gestural, audio, spatial, digital dimension of communication. Although several study have been conducted in exploring the use of digital storytelling project to foster students' multimodal literacies, in Indonesian context, almost none of the researches focused on the development of students' multimodal literacies in orchestrating different use of all semiotic modes in making meaning and communicating ideas. This study will explore how the use of pedagogy of multiliteracies in the Digital Storytelling (DST) project can contribute to the students' multiliteracies. Utilizing a case study design, this study will involve 30 elementary school students from the fifth grade and 1 elementary school English teachers. The school site and the teacher is purposively chosen as they have previously joined a digital story project. Multiple method of data collection will be used to triangulate findings, among others are the result of observation, interviews with students and teachers, and the document analysis including students' story scripts and final product of DST. The analysis of the findings will be based on the description of the course and the project, procedure and instructional steps using the pedagogy of multiliteracies, students' use of multimodality in their digital story and students' knowledge and discovery on multimodality

RELATED PAPERS

Universal Journal of Educational Research

García-Pinar Aránzazu

Sylvana Sofkova Hashemi

Language, Culture and Curriculum

Leila Kajee

Annual Review of Applied …

Heather Lotherington

Journal of Media Literacy Education

Robin Jocius

E-Learning and Digital Media

Jen Scott Curwood

Gillian Brooks

Journal of Educational Policies and Current Practices

Richard (Jianxin) Liu

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Miguel Farias

Languages 2021, 6(3), 140.

Languages _MDPI

Terry Loerts

Research in the Teaching of English

Mary McVee , Lynn E Shanahan , Nancy Bailey

Elyse Petit

Elyse Barbara Petit

Phillip Towndrow , Mark Evan Nelson , Wan Fareed

Marjorie Siegel

Pablo Peláez

Roxana C Orrego

Bill Cope , Mary Kalantzis , Sonia Kline

Multimodal Communications

Navan N Govender

Carl Young , Robert Rozema

Sri Endah Kusmartini

Dwi Astuti Wahyu Nurhayati

W. Ian O'Byrne

Adelia Carstens

Nato Pachuashvili

Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics. Special issue "Multimodality in Education"

Sofia Goria

UC Berkeley L2 Journal

Christelle Palpacuer Lee

Teaching Education

Eu Made 4ll , ilaria moschini , Daniela Cesiri , Giuseppe Balirano , Massimiliano Demata , Arianna Maiorani , Maria Bortoluzzi , Inmaculada Fortanet Gómez

Tuba Angay-Crowder

Pedagogies: An International Journal

Maureen Kendrick , Diane R. Collier

Naomi Silver

Chris Walsh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Browser does not support script.

- Departments and Institutes

- Research centres and groups

- Chair's Blog: Summer Term 2022

- Staff wellbeing

Oral presentations

Oral assessments offer teachers the opportunity to assess the structure and content of a presentation as well as students’ capacity to answer any subsequent probing questions. They can be formatted as individual presentations or small-group presentations; they can be done face-to-face or online, and they can be given behind closed doors or in front of peers. The most common format involves one or two students presenting during class time with a follow-up question and answer session. Because of logistics and the demands of the curriculum, oral presentations tend to be quite short – perhaps 10 minutes for an undergraduate and 15-20 minutes for a postgraduate. Oral presentations are often used in a formative capacity but they can also be used as summative assessments. The focus of this form of assessment is not on students’ capacity to find relevant information, sources and literature but on their capacity to package such materials into a logically coherent exposition.

Advantages of oral presentations

- Allows for probing questions that test underlying assumptions.

- Quick to mark – immediate feedback is possible.

- Allow students to demonstrate a logical flow/development of an idea.

- Presentation skills are valued by employers.

- Students are familiar with this assessment method.

Challenges of oral presentations

Can be stressful for some students.

Non-native speakers may be at a disadvantage.

Can be time-consuming.

Limited scope for inter-rater checks.

A danger that ‘good speakers’ get good marks.

How students might experience oral presentations

Students are often familiar with giving oral presentations and many will have done so in other courses. However, they may focus too much on certain aspects to the detriment of others. For example, some students may be overly concerned with the idea of standing up in front of their peers and may forget that their focus should be on offering a clear narrative. Other students may focus on the style of their presentation and overlook the importance of substance. Others yet may focus on what they have to say without considering the importance of an oral presentation being primarily for the benefit of the audience. The use of PowerPoint in particular should be addressed by teachers beforehand, so that students are aware that this should be a tool for supporting their presentation rather than the presentation in itself. Most oral presentations are followed by a question and answer phase – sometimes the questions will come from peers, sometimes they will come from teachers, and sometimes they will come from both. It is good practice to let students know about the format of the questions – especially if their capacity to answer them is part of the marking criteria.

Reliability, validity, fairness and inclusivity of oral presentations

Oral assessments are often marked in situ and this means that the process for allocating marks needs to be reliable, valid and fair when used under great time pressure. Through having a clearly defined marking structure with a set of pre-established, and shared, criteria, students should be aware of what they need to do to access the highest possible marks. Precise marking criteria help teachers to focus on the intended learning outcomes rather than presentational style. During oral presentations content validity is addressed through having marking criteria that focus on the quality of the points raised in the presentation itself and construct validity is addressed during the question and answer phase when the presenter is assessed for their capacity to comment on underpinning literature, theories and/or principles. One of the issues in having peer questions at the end of an oral presentation is that the teacher has very little control over what will be asked. This does not mean that such questions are not legitimate – only that teachers need to carefully consider how they mark the answers to such questions. In order to ensure equality of opportunity, teachers should ask their own questions after any peer questions, using them to fill any gaps and offer the presenter a chance to address any areas of the marking criteria that have not yet been covered. Oral presentation may challenge students with less proficiency in spoken English, and criteria should be scrutinised to support their achievement.

How to maintain and ensure rigour in oral presentations

Assessment rigour for oral presentations includes the teacher’s capacity to assess a range of presentation topics, formats and styles with an equal level of scrutiny. Teachers should therefore develop marking criteria that focus on a student’s ability to take complex issues and present them in a clear and relatable manner rather than focus on the content covered. Throughout this whole process teachers should be involved in a form of constant reflexive scrutiny – examining if they feel that they are applying marking criteria fairly across all students. As oral presentations are ephemeral, consider how the moderator and/or external examiner will evaluate the assessment process. Can a moderator ‘double mark’ a percentage of presentations? Is there a need (or would it be helpful) to record the presentations?

How to limit possible misconduct in oral presentations

The opportunities for academic misconduct are quite low in an oral presentation – especially during the question and answer phase. If written resources are expected to be produced as part of the assessment (handouts, bibliographies, PowerPoint slides etc.) then guidance on citing and referencing should be given and marking criteria may offer marks for appropriate use of such literature. In guiding students to avoid using written scripts (except where it is deemed necessary from an inclusivity perspective) teachers will steer them aware from the possibility of reading out someone else’s thoughts as their own. Instead, students should be encouraged to use techniques such as limited cue cards to structure their presentation. The questions posed by the teacher at the end of the presentation are also a possible check on misconduct and will allow the teacher to see if the student actually knows about the content they are presenting or if they have merely memorised someone else’s words.

LSE examples

MA498 Dissertation in Mathematics

PB202 Developmental Psychology

ST312 Applied Statistics Project

Further resources

https://twp.duke.edu/sites/twp.duke.edu/files/file-attachments/oral-presentation-handout.original.pdf

Langan, A.M., Shuker, D.M., Cullen, W.R., Penney, D., Preziosi, R.F. and Wheater, C.P. (2008) Relationships between student characteristics and self‐, peer and tutor evaluations of oral presentations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , 33(2): 179-190.

Dunbar, N.E., Brooks, C.F. and Kubicka-Miller, T. (2006) Oral communication skills in higher education: Using a performance-based evaluation rubric to assess communication skills. Innovative Higher Education , 31(2): 115.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HRaPmO6TlaM

https://www.lse.ac.uk/resources/calendar/courseGuides/PB/2020_PB202.htm

Implementing this method at LSE

If you’re considering using oral presentations as an assessment, this resource offers more specific information, pedagogic and practical, about implementing the method at LSE. This resource is password protected to LSE staff.

Back to Assessment methods

Back to Toolkit Main page

Contact your Eden Centre departmental adviser

If you have any suggestions for future Toolkit development, get in touch using our email below!

Email: [email protected].

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.12(6); 2020 Jun

Remote Assessment of Video-Recorded Oral Presentations Centered on a Virtual Case-Based Module: A COVID-19 Feasibility Study

Conrad krawiec.

1 Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Penn State Health Children's Hospital, Hershey, USA

Abigail Myers

2 Pediatrics, Penn State Health Children's Hospital, Hershey, USA

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in the suspension of our pediatric clerkship, which may result in medical student skill erosion due to lack of patient contact. Our clerkship has developed and assessed the feasibility of implementing a video-recorded oral presentation assignment and formative assessment centered on virtual case-based modules.

This retrospective study examined the feasibility of providing a remote formative assessment of third-year medical student video-recorded oral presentation submissions centered on virtual case-based modules over a one-week time period after pediatric clerkship suspension (March 16th to 20th, 2020). Descriptive statistics were used to assess the video length and assessment scores of the oral presentations.

Twelve subjects were included in this study. Overall median assessment score [median score, (25th, 75th percentile)] was 5 (4,6), described as “mostly on target” per the patient presentation rating tool.

Patient-related activities during the pediatric clerkship were halted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study demonstrated the possibility of remotely assessing oral presentation skills centered on virtual case-based modules using a patient presentation tool intended for non-virtual patients. This may prepare students for their clinical experiences when COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. Future studies are needed to determine if suspended clerkships should consider this approach.

In 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in the unprecedented prolonged closure of educational institutions worldwide to curb the spread of the virus [ 1 , 2 ]. Medical students were included in this group of learners per the guidance of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) [ 3 ]. Thus, our institution temporarily suspended the clinical portion of the pediatric clerkship.

Electronic resources exist to supplement the pediatric clerkship curriculum, thus key aspects can be taught remotely [ 4 - 7 ]. One aspect that electronic sources lack, however, is patient contact. Lack of patient contact results in the inability to practice clinical skills, including interviewing or orally presenting patients recently seen. These clinical skills are often assessed during the pediatric clerkship and students will often specifically receive feedback on these skills [ 8 ]. They are also prioritized by some clerkships for the summative evaluation as students must develop these skills to demonstrate they can assess a patient and synthesize their medical knowledge [ 8 ].

At our institution, we have instituted a remote learning curriculum for our third-year medical students starting at the end of April 2020. When COVID-19 restrictions are lifted, our students will undergo two weeks of patient contact time. Because our students will not have been in a clinical environment for a prolonged time period, they may have difficulty transitioning [ 9 ]. To minimize the impact this transition will have on our students, our pediatric clerkship has developed a video-recorded oral presentation assignment centered on a virtual case-based module with remote formative assessment. Our goal was to enhance the development of this clinical skill remotely thereby allowing students to focus on clinical skill development in areas that cannot be achieved without patient contact (i.e., patient interviewing) when restrictions are lifted.

The objective of this study is to demonstrate the feasibility of student video-recording an oral presentation centered on a virtual case-based module and having our attending faculty members provide a formative assessment. The study hypothesis is that it is feasible to assess and provide formative feedback on video-recorded oral presentations by pediatric attending faculty members using a patient presentation rating tool intended for non-virtual patients.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a feasibility study requesting students to video-record an oral presentation centered on a virtual case-based module for formative assessment during a time period (March 16th, 2020 until March 19th, 2020) when Pennsylvania State College of Medicine third-year medical students were abruptly restricted from providing direct patient care during the pediatric clerkship. A retrospective review of faculty submitted formative assessments of the video-recorded oral presentations centered on virtual case-based modules was completed. This study was reviewed by our institution’s review board and determined to be non-human research.

Subject population

Third-year medical students - (1) part of our institution’s traditional curriculum, (2) rotated at the pediatric clerkship’s primary site or off-campus affiliate sites during the first month of the academic year (2020-2021), (3) were abruptly restricted from direct patient care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and (4) completed a video-recorded oral presentation centered on a virtual case-based module - were included in this study. Students who were part of the longitudinal integrated curriculum were excluded.

Clerkship overview

The pediatric clerkship at our institution is a four-week rotation with the following clinical requirements: outpatient clinic, nursery, and inpatient service. On March 16th, third-year students were restricted from direct patient care, thus only three weeks of the clerkship was completed.

Video-recorded oral presentation assignment and assessment creation

The video-recorded oral presentation assignment was developed by a pediatric clerkship director experienced in inpatient medicine and an outpatient pediatrician. A patient presentation tool developed by Lewin et al. was utilized for this assessment [ 10 ].

Using behavioral and verbal anchors, the patient presentation tool assesses various oral presentation sections including patient history, physical exam and diagnostic study results, summary statement, assessment and plan, clinical reasoning/synthesis of information, and general aspects (organization, speaking style) based on a 5-point scale (5 being the highest) [ 10 ]. Overall assessment of presentation is based on a 9-point scale (9 being the highest and described as “well above expectations”). Eight faculty members were recruited to use this tool as they were assessing the video recordings.

Video-recorded oral presentation assignment implementation

Starting on March 16th, 2020, the subjects were provided a remote learning curriculum and were notified of the video-recorded oral presentation assignment. They were informed that the pediatric clerkship will be graded pass/fail, that submission of a video-recorded oral presentation for formative assessment will be required, and was due on March 19th, 2020. The subjects were instructed to (1) video-record an oral presentation of either a patient they have seen during the course of the clerkship or after completing a virtual online case-based module through Aquifer © (Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA) and (2) upload the assignment via the Instructure Canvas (Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) learning management system. Students were given specific directions including the use of professional attire, limiting the video-recording to 10 minutes, and requesting students to review the video prior to submission for clarity and organization. After receiving the video-recordings, the files were securely distributed through the CANVAS © learning management system among eight pediatric attending faculty volunteers who reviewed and provided formative assessment scores of the oral presentation.

Data collection

All completed assignments were collected using the Instructure Canvas learning management system. Using the Canvas learning management system, we extracted the following data: overall video-recorded oral presentation rating scores and video-recorded oral presentation scores divided by section as outlined by the patient presentation tool [ 10 ].

Virtual case-based module

If students elected to give an oral presentation based on a virtual case-based module, we asked students to complete the pediatric Aquifer © case-based module 3, a 3-year-old male seen for a well-child visit [ 4 ]. This case was chosen as it provides a robust history and physical examination, tasks the student to identify and prioritize problems uncovered during this visit, allows the student to apply a differential diagnosis when appropriate, formulate a management plan, and practice their organization skills during the oral presentation.

We used descriptive statistics to assess the study population in terms of length of presentation, type of patient presented, and assessment scores based on the patient presentation tool [ 10 ]. Formative assessment of each oral presentation was reported in the median and interquartile range.

Twelve individual oral presentation videos centered on the virtual case-based module were included in this study. Median video length [median time (mm:ss), (25th, 75th percentile)] was 06:20 (05:04,07:21).

Video-recorded oral presentation assessment scores

Overall, median overall formative assessment score [median score, 25th, 75th percentile] of video-recorded oral presentation centered on virtual case-based modules was 5 (4,6), described as “mostly on target” per the patient presentation tool [ 10 ]. The lowest items scored were pertinent positives and negatives of the differential diagnosis [2 (1,3)] (Table (Table1 1 ).

Note: Sections scored on a 1 to 5 scale, 5 being the highest score

Patient Presentation Rating Tool for Oral Case Presentations [ 10 ].

Oral presentations are an essential clinical skill that facilitates physician to physician communication, improves efficiency on rounds, and enables individual as well as group learning [ 8 ]. It also can be complex and time-consuming as students must use their medical knowledge and clinical reasoning skills to select the pertinent details to present from a patient’s history, physical, diagnostic, and laboratory tests [ 8 , 10 ]. In this study, we hypothesized that video-recorded oral presentations centered on a virtual case-based module can undergo a formative assessment. This study successfully demonstrated that a formative assessment can be remotely provided for video-recorded presentations based on virtual case-based modules. These results imply that this form of assessment is possible, may prepare students for the eventual live clinical experience (with patient contact), and potentially optimize the transition period from COVID-19 remote learning to a post-COVID-19 clinical patient experience.

To our knowledge, a pediatric clerkship has never been halted in this manner for a prolonged period due to a nationwide health emergency. Because of this, our pediatric clerkship, like others across the United States was placed in an unprecedented situation, potentially placing our students at risk of achieving suboptimal competency in various clinical areas [ 11 ]. Novel approaches are necessary to ensure that our students, who were hastily restricted during their pediatric clerkship and future students that have yet to complete their pediatric clerkship, are adequately trained [ 11 ].

Our institution’s current plans are for each clerkship to institute a remote learning curriculum and complete a two-week immersive clinical experience in each of the core clerkships. The remote learning curriculum will allow students to learn the basic concepts relevant for pediatrics and the two-week patient contact experience will allow students to apply their knowledge. When the two-week patient contact experience begins, however, the transition period may be difficult. Students will not have seen a patient (possibly for months) and similar to transitioning from the pre-clerkship to clerkship years, students may be overwhelmed by clerkship logistics, expectations, and adjusting to the clinical culture [ 12 ]. In all, students may be overwhelmed by this and the number of tasks they must complete in a short time period post-clerkship suspension, potentially limiting their clinical experience.

Thus, it is the clerkship’s responsibility to ensure that students in a remote curriculum continue to be comparably trained and are provided as many similar clinical experiences as possible to ease the transition that will occur on clerkship reinstatement. While the pediatric clerkship is currently limited in allowing students to see patients during the remote learning experience, there are other ways that students can be robustly prepared for the clinical environment. The area that our clerkship elected to focus on is the oral presentation.

If students are rigorously prepared to practice oral presentation skills using pediatric faculty members (that they will eventually present to), students may start to apply their communication, medical knowledge, and clinical reasoning skills earlier and potentially focus their clinical skills on other areas that they cannot easily achieve remotely (i.e., history taking and physical examination and providing live patient care) when they return to clerkship. Students may also have a better understanding of their expectations, roles, and responsibilities of this skill for our clerkship and thus are better prepared to provide meaningful patient care and be effective team members sooner.

In our study, we found that it is feasible for students to submit a video-recorded oral presentation centered on a virtual case-based module and recruit pediatric attending faculty members to assess and provide formative feedback. We also found that the overall median scores were “mostly on target” according to the patient presentation tool. The students who completed these assessments were the first students for the academic year, thus these results may indicate that these students developmentally require more practice. Alternatively, these results may indicate that because these assessments are formative and the clerkship is now pass/fail, these students were given the feedback necessary to improve their skills. Finally, students may not have received enough individual educational attention during the normal clinical workflow and thus were not given enough instruction. More studies are necessary to determine if these assessments are consistent.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. This includes its small sample size, the short intervention period, and the lack of randomization. The patient presentation rating tool intended for live patients was used without the opportunity to validate it for use in virtual case-based modules due to the haste in its implementation. Future studies will be required to validate the tool for this purpose. Student perception is also unknown regarding the effectiveness of this assessment technique, thus future qualitative studies are planned to determine this.

Conclusions

Our pediatric clerkship was suddenly curtailed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The students were provided a remote learning curriculum to emphasize pediatric concepts but may not be able to demonstrate their clinical skills in communication, data synthesis, and patient assessment. Our study demonstrated that it is possible to assess oral presentation skills centered on virtual case-based modules using a patient presentation rating tool intended for non-virtual patients and may potentially prepare students for their clinical experiences when COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. Future studies are needed to determine if suspended clerkships should consider this approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to our pediatric faculty, who took the time to assess our students during this stressful time.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Penn State College of Medicine Institutional Review Board issued approval STUDY00014941. The Human Subjects Protection Office determined that the proposed activity, as described in the above-referenced submission, does not meet the definition of human subject research as defined in 45 CFR 46.102(e) and/or (l). Institutional Review Board (IRB) review and approval is not required. Please note: While IRB review and approval is not required, you remain responsible for ensuring compliance with FERPA. If you have additional questions regarding FERPA regulations, please contact the Office of the University Registrar. The IRB requires notification and review if there are any proposed changes to the activities described in the IRB submission that may affect this determination. If changes are being considered and there are questions about whether IRB review is needed, please contact the Human Subjects Protection Office.

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

About the Language Assessment Tools

The language assessment tools provided for use on the Purdue ELL Language Portraits (Purdue ELLLPs) are proven formative assessments that effective teachers use to determine their ELL students’ current level of ability, to understand their strengths, to identity areas in need of improvement, and to plan future instruction that will build upon and address these strengths and needs.

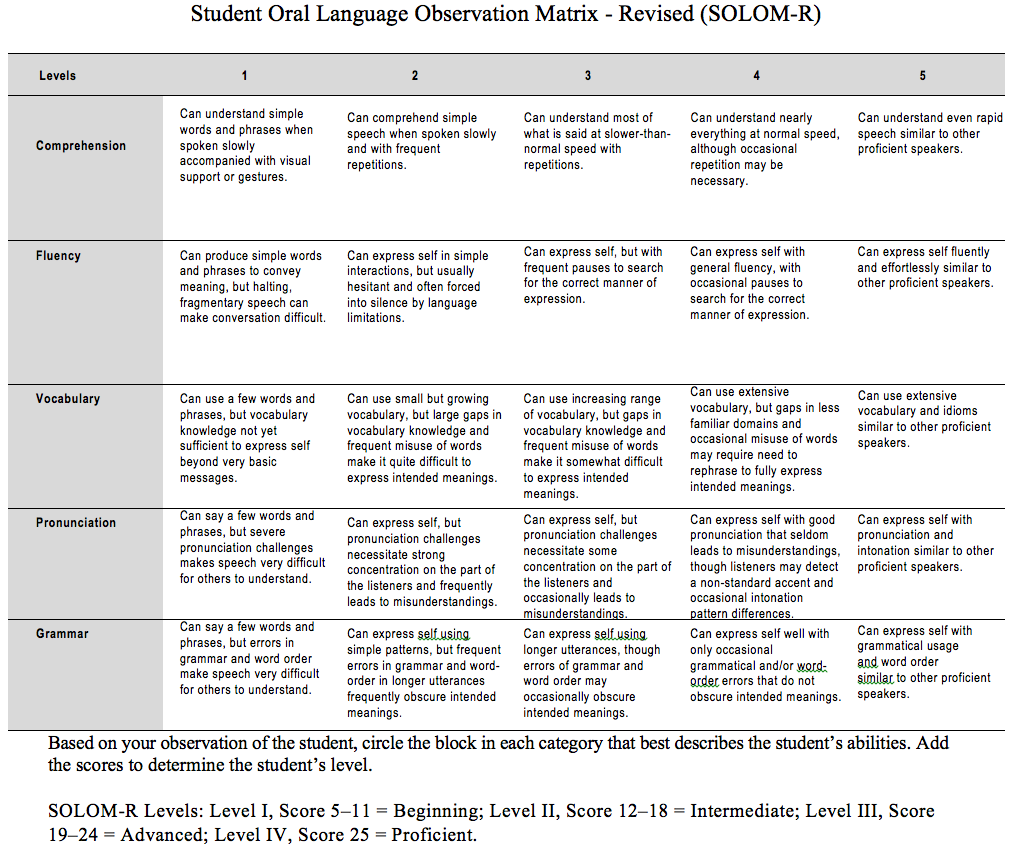

Student Oral Language Observation Matrix – Revised (SOLOM-R)

The Student Oral Language Observation Matrix (SOLOM) was first developed in the 1980s by bilingual teachers in California as a formative assessment to quickly gauge the listening and speaking ability of English language learners in English (and also the Spanish listening and speaking skills of English-proficient students in dual language bilingual education programs).

The SOLOM was revised by Wright in his book Foundations for Teaching English Language Learners: Research, Theory, Policy, and Practice (Brookes Publishing) (See Figure 1)

The Student Oral Language Observation Matrix-Revised (SOLOM-R) emphasizes what ELLs can do at each level of English proficiency and brings the original SOLOM up to date with current research on oral language development. The SOLOM-R helps teachers focus on five aspects of oral language:

- Comprehension – Engage the student in an informal or formal oral language tasks (e.g., conversations, interactive pair or group work, oral presentation, story retelling, or other performance requiring listening and speaking)

- Fluency – How well does the student speak? Are you able to have a conversation with him or her? Does the student’s speech flow well but occasionally gets stuck as he or she searches for the correct word?

- Vocabulary – How well does the student speak? Are you able to have a conversation with him or her? Does the student’s speech flow well but occasionally gets stuck as he or she searches for the correct word?

- Pronunciation – Are others able to understand what the student is saying? Do accent or intonation patterns sometimes lead to miscommunication?

- Grammar – Are grammar errors so frequent it is hard to understand the student? Or do they only occasionally obscure the meaning he or she is trying to convey?

Source: Wright (2015, p. 176)

Instructions for Administration and Evaluation of the SOLOM-R

- Engage the student in an informal or formal oral language tasks (e.g., conversations, interactive pair or group work, oral presentation, story retelling, or other performance requiring listening and speaking)

- Scores the students in each of the five areas above on a scale of 1 to 5.

- Add the scores to determine the student’s overall evaluation of the student’s oral language proficiency. The higher the score, the higher the student’s level of proficiency.

- Identify the student’s strengths, areas in need of improvement, and instructional activities that would benefit the student’s oral language development.

For the Purdue ELL Portraits, videos clips of student interviews and oral presentations are provided along with blank SOLOM-R forms.

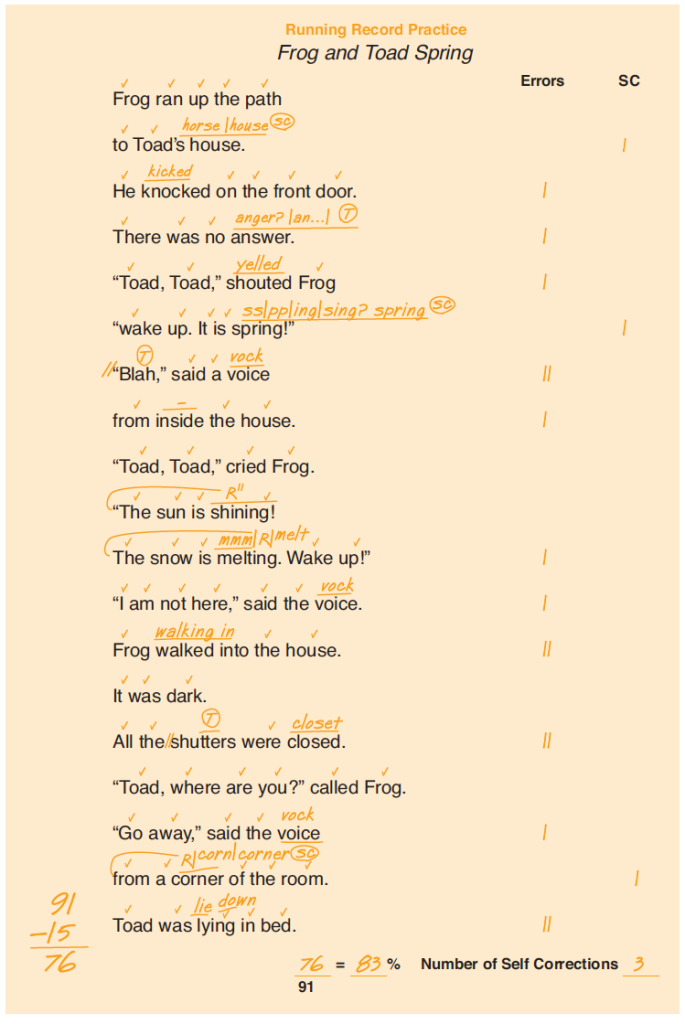

Running Records

A running record is a tool for in-depth observation and analysis of a student’s reading performance. It is essentially a visual recording of the student’s reading word by word. It enables a teacher to identify the reading strategies the student may or may not be using and the types of errors the student makes while reading. As Wright (2015) explains, “These errors reveal what is going on in the students’ mind as he or she attempts to make meaning from the text. Running records allow a teacher to quickly assess the students’ strengths and areas in need of improvement” (p. 213). An example of completed Running Record is provided in Figure 2.

Instructions for Administration and Evaluation of a Running Record

- Select a text you believe is at the student’s instructional level

- Prepare a running record form with a selection of text (no more than 100 words)

- Correct Reading – Write a check mark ✓above each word read correctly

- Omission Error – Write a dash (—) above each word that was omitted (skipped) without any effort to read it

- Substitution Error – Write the incorrect word the student said above the word the student read incorrectly

- Insertion Error – Write an insertion mark (^) at the point of insertion and write the inserted word

- Told Word Error (T) – If a student gets stuck on a word and appeals or help, or won’t go on, tell the student the correct word. Write a T and circle the T above the word to indicate “told.”

- Try That Again (TTA) Error – if a students reads a sentence or long phrase with several errors, and you think the student is capable of reading more accurately, you can ask the student to “Try that again.” Write TTA above the end of the sentence or phrase. Previous errors are discarded, but a TTA counts as 1 error (even if the student re-reads the sentence/phrase correctly)

- Repetition – Write the letter R at the point of repetition and draw a line back to the beginning of the repeated text. Add tally marks as after the R to indicate the number of times the text was repeated. Repetition does not count as an error.

- Self Corrections – If a student corrects an omission, insertion, or substitution error on his or her own, disregard the error and write (SC) above the point of self-correction

- Long Pause – If the student makes a long pause before reading a word, write a double forward slash // before the word. Pauses do not count as an error.

- Decoding attempts – If a student is audibly sounding out parts of the word as they attempt to decode, you may record these attempts above the word (e.g., sssss | aaaa | t |) Write a check mark if the student successfully reads the word (e.g., “sat”). Decoding attempts do not count as an error if the student is able to ultimately read the word correctly.

- On the running record sheet, keep a tally of the number of errors and self-corrections per line.

- Add up the total number of errors.

- Determine the number of words read correctly by subtracting the number of errors from the total number of words.

- Calculate the percentage of words read correctly by dividing the number of words read correctly by the total number of words.

- 95% + = Easy

- 90% – 94% = Instructional

- Less than 90% = Frustration

- Ask the student comprehension questions about the text and write down their answers.

- Identify the students strengths, areas in need of improvement, and instructional activities that would benefit the student’ reading development.

For the Purdue ELL Portraits, videos clips are provided of students reading selected texts, along with pre-prepared Running Record forms, and students’ responses to comprehension questions.

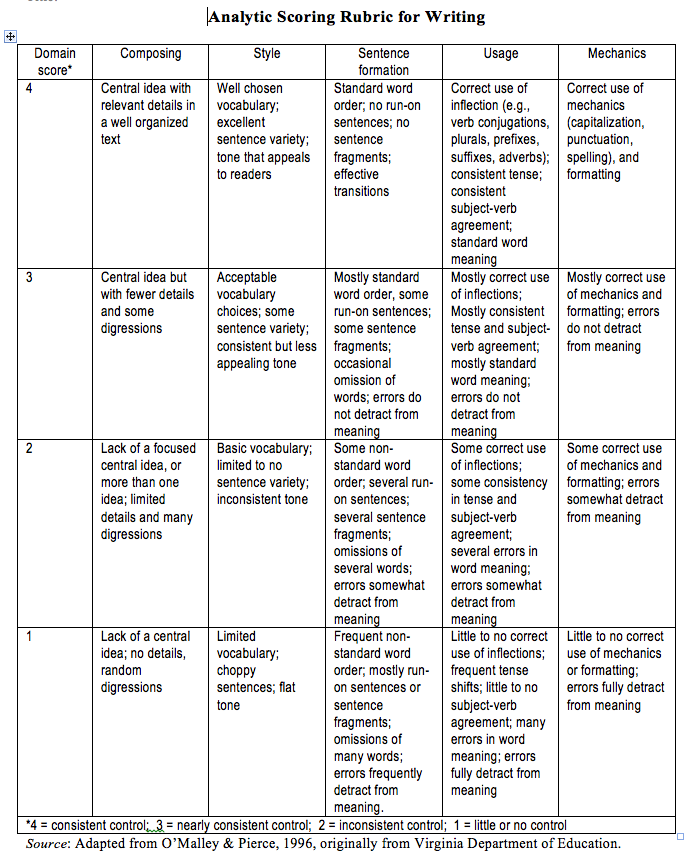

Writing Evaluations

Student writing may be evaluated with a rubric designed to help teachers focus on different aspects of the student’s writing. The Analytic Scoring Rubric for Writing used on this site (see Figure 3) was first developed by educators in Virginia in the 1990s, and was adapted by Wright (2015) for the 2nd edition of Foundation for Teaching English Language Learners: Research, Theory, Policy, and Practice (Caslon Publishing).

The rubric focuses on five areas:

- Composing – Does the text have a central idea and relevant details. Is the text well-organized?

- Style – Does the text have well-chosen vocabulary, good sentence variety, and an appealing tone?

- Sentence Formation – Are the sentences well formed with standard word order and effective transitions? Is the text free of sentence fragments and run-on sentences?

- Usage – Is there correct use of inflections (e.g., verb conjugations, plurals, prefixes, suffixes, adverbs, etc.), consistent use of tense, subject-verb agreement, and standard word meaning?

- Mechanics – Is there correct usage of capitalization, punctuation, spelling, and formatting?

Instructions for Administration and Evaluation of the Analytic Scoring Rubric for Writing

- Have students complete a piece of writing appropriate to their grade and English-proficiency level

- Read the completed writing sample and score it in each of the 5 areas of the rubric on a scale of 1 – 4.

- Identify the students strengths, areas in need of improvement, and instructional activities that would benefit the student’ written language development.

For the Purdue ELL Portraits, writing samples are provided of students’ unedited writing, along with blank Analytic Scoring Rubric for Writing Forms.

Source: Wright, W. E. (2019). Foundations for teaching English language learners: Research, theory, policy, and practice . Philadelphia, PA: Brookes Publishing.

COMMENTS

Acquiring complex oral presentation skills is cognitively demanding for students and demands intensive teacher guidance. The aim of this study was twofold: (a) to identify and apply design guidelines in developing an effective formative assessment method for oral presentation skills during classroom practice, and (b) to develop and compare two analytic rubric formats as part of that assessment ...

We use a wide variety of oral assessment techniques at UCL. Students can be asked to: present posters. use presentation software such as Power Point or Prezi. perform in a debate. present a case. answer questions from teachers or their peers. Students' knowledge and skills are explored through dialogue with examiners.

formative assessment methods for other contexts, and for complex skills other than oral presentation, and should lead to more profound understanding of video-enhanced rubrics. Keywords Digital rubrics · Analytic rubrics · Video-enhanced rubrics · Oral presentation skills · Formative assessment method * Rob J. Nadolski [email protected]

Oral presentations can be made as formative assessment where instructors are expected to gi ve feedback for learners to improve their skills (Man et al., 2022; Murillo - Zamorano & Montaner, 2017).

This paper describes the oral assessment activity we designed and used as a culminating activity for faculty participants in a professional academic development program. The program offers multiple certificates, and the goal of each certificate is to enhance participants' abilities to design and deliver exceptional student learning experiences.

The aim of this study was twofold: (a) to identify and apply design guidelines in developing an effective formative assessment method for oral presentation skills during classroom practice, and (b ...

Assessment of oral presentation skills is an underexplored area. The study described here focuses on the agreement between professional assessment and self- and peer assessment of oral presentation skills and explores student perceptions about peer assessment. The study has the merit of paying attention to the inter-rater reliability of the ...

Keywords: oral assessment, formative, summative, presentations, student learning International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 22(3), 74-80, 2014. ... Formative peer assessment of an oral presentation also provides the presenters with immediate feedback. While this type of feedback may not be as accurate as feedback ...

Engaging students in the assessment process is challenging. In this Innovations in Practice article, the integration and implementation of online peer review of oral presentations into an undergraduate English Literature curriculum will be presented. The aim of the integration is to bridge the gap between tertiary education and the workplace ...

Ho LME (2018) Improving ESL formative assessment practices and student learning via multi-staged peer assessment of oral presentations. Doctoral dissertation, University of Bristol, UK. ... Nicol DJ, Macfarlane-Dick D (2006) Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in ...

Quality criteria for feedback. A recently published review study on assessment and evaluation in higher education (Pereira, Flores, and Niklasson Citation 2015) revealed that many recent articles have addressed formative assessment, modes of assessment (i.e. peer- and self-assessment) and their (assumed) effectiveness.While empirical evidence on the effectiveness of formative assessment in ...

This article describes how one English and humanities teacher used the formative assessment framework to teach students to develop their oral presentation skills. Research on the effectiveness of formative assessment and the importance of teaching presentation skills is highlighted along with a discussion on the instructional process and ...

Oral presentations can be one of instances of formative assessment in the classroom. This multimodal assessment can be used to create an interactive feedback session which afford more

Taking into account Wiliam's (2011) strategies for successful formative assessment practice and the advancement of Computer-mediated Communication (CMC) use in learning, this paper illustrates the emergence of students' oral presentation as multimodal assessment in language classrooms particularly at tertiary level, and provides insights ...

Because of logistics and the demands of the curriculum, oral presentations tend to be quite short - perhaps 10 minutes for an undergraduate and 15-20 minutes for a postgraduate. Oral presentations are often used in a formative capacity but they can also be used as summative assessments. The focus of this form of assessment is not on students ...

The oral assessment format allows the potential evaluation of all six cognitive domains of Bloom's taxonomy, which are knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, evaluation, and creation . This makes it a valuable multifunctional assessment type. Additionally, assessments can also be classified into summative and formative assessments ...

Materials and methods. Study design. This is a feasibility study requesting students to video-record an oral presentation centered on a virtual case-based module for formative assessment during a time period (March 16th, 2020 until March 19th, 2020) when Pennsylvania State College of Medicine third-year medical students were abruptly restricted from providing direct patient care during the ...

This study designed formative self-assessment and peer assessment (SAPA) to help students develop oral presentation skills in a specialization course in a Chinese university. The study aimed to investigate feasible and practical principles and strategies and identify students' learning performances and perceptions of the SAPA method. Both quantitative and qualitative data related to students ...

formative assessment and summative assessment. 2.2.1. Formative Assessment Black and Wiliam [3] defined formative assessment as "activities undertaken by teachers and by their students in assessing themselves that provide information to be used as feedback to modify teaching and learning activities." Thus, formative assessment aims to provide

advanced English courses were requested to assess their oral presentations and the oral presentations of their peers. Four teachers used the same rating scale to assess all students' oral presentations. To obtain students' attitudes towards self- and peer assessments, a questionnaire was administered before and after the employment of

Overview. The Student Oral Language Observation Matrix (SOLOM) was first developed in the 1980s by bilingual teachers in California as a formative assessment to quickly gauge the listening and speaking ability of English language learners in English (and also the Spanish listening and speaking skills of English-proficient students in dual language bilingual education programs).

Formative assessment is incorporated in the national curriculum of both primary and lower-secondary school teacher education programmes. This is because assessment in primary and lower secondary schools is mainly formative, with grades only provided in secondary school. ... It is usually followed by an oral presentation either as one written ...