- Premier Google Partner

- Meta Business Partner

- Digital Marketing Referral Program

- Google Marketing Solutions

- Google Shopping

- Google Display Network

- YouTube Ads

- SEO Solutions

- SEO Referral Program

- International SEO

- Off-Page SEO & Link Building Services

- SEO Copywriting

- E-commerce SEO

- Shopify SEO

- Social Media Marketing Solutions

- Paid Social

- Social Media Management

- LinkedIn Ads

- Content Marketing

- Copywriting

- Skyscraper Content

- Social Media Content

- Infographic Content Creation

- Blog Article

- Website Development Solutions

- E-commerce Website Design and Development

- Corporate Website Design and Development

- Dedicated Landing Page Development

- Website Maintenance

- Domain/Hosting

- Creative Solutions

- Display Ads Production

- YouTube Video Ads Production

- China Digital Solutions

- WeChat Marketing

- Digi-TAC Grant for TACs

- Case Studies

- Digital Marketing Singapore

- Facebook Marketing Singapore

- Why Google Ads Management

- Digital Marketing Videos

- Free Google Ads Consultation

- Free SEO Audit Report

- Free Competitor Analysis Report

The POEM Framework: How To Optimise Your Marketing Strategies?

Nov 26 2021

Posted by Carlo Angelo Suñga

Introduction

The Rise of the POEM Framework

Part I – Understanding The Poem Framework

Owned Media

Earned media.

Part II – How To Use Poem For Marketing?

List Of Marketing Strategies That Affect POEM

Part III – The Pros And Cons Of Poem

The Future Of POEM

The digital marketing landscape has been continuously growing and evolving in the past few years, with trends changing and consumers becoming more engaged with businesses.

However, regardless of the many constant changes in the digital marketing industry, one thing will always remain relevant: the POEM framework.

But what exactly is the POEM framework , anyway?

The POEM framework is a business model that marketers use as a reference for their digital marketing strategies. You can use the POEM framework for various digital marketing practices, such as social media management, SEO, SEM, and many more.

The Rise Of The Poem Framework

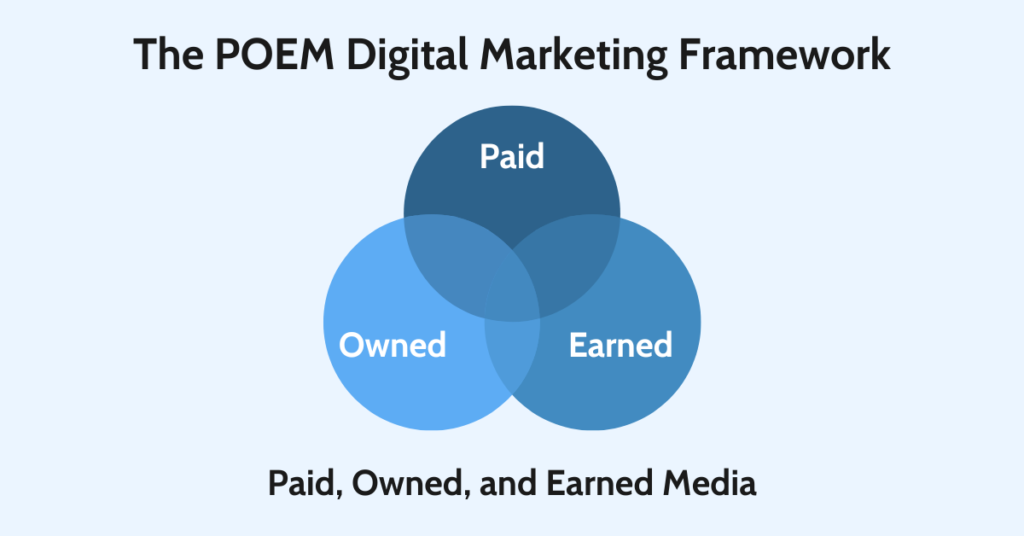

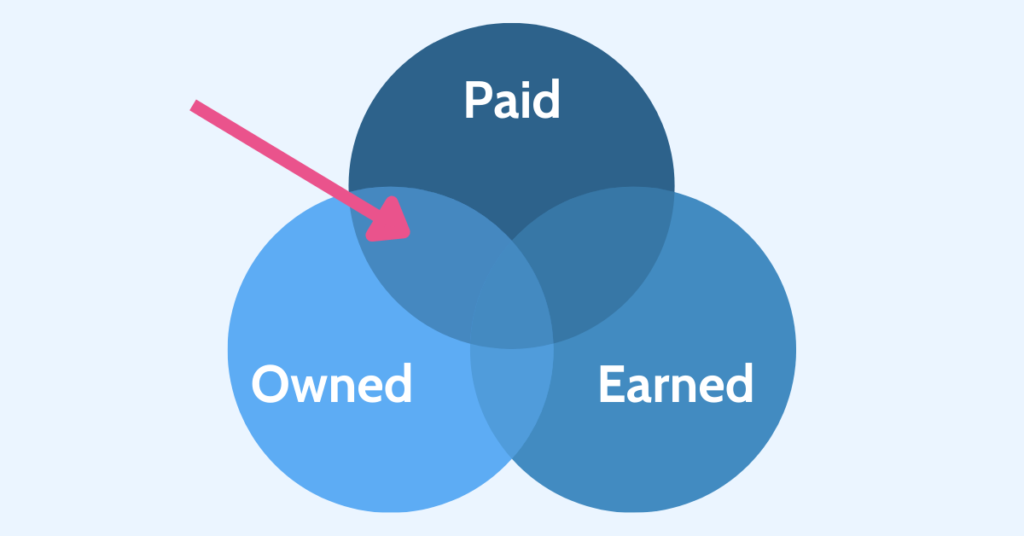

POEM in digital marketing is not about words that rhyme and help express emotions. This acronym, POEM framework, stands for paid, owned, and earned media.

While the POEM framework has nothing new to most experienced marketers, not everyone is aware of its importance for marketing. With so many changes and additions to the digital marketing industry, it is not surprising that many people overlook the significance of the POEM (or P.O.E.M.) framework.

You should know that the POEM framework has been around for decades, and it continues to evolve up to this day. You can use POEM as a guide for your marketing strategy and formulate better tactics that will allow you to attract more traffic , gain leads and boost sales.

The best way to achieve success for your digital marketing efforts is to follow the POEM framework . With the right balance of paid, owned, and earned media marketing strategies, you can think and plan better and more effective tactics for your business.

Part 1 – Understanding The Poem Framework

The POEM framework is a business methodology that you can use to develop your digital marketing strategies. There are three parts of the POEM framework : paid, owned, and earned media, all of which will affect every aspect of your digital marketing campaign.

Know More: POEM In Digital Marketing | What Is It & Why Must You Use POEM?

The first part of the POEM framework —paid media . It is the most common type of marketing channel. Any avenue or space that requires payment falls under this category. Most advertisements are also part of paid media, including sponsorships and publications.

In the context of digital marketing , paid media offers a variety of channels that you can use to expand your reach. Paid media is one of the quickest and most efficient ways to connect with your target audience. By promoting your products or services on paid media channels, such as Google Ads and Facebook Ads—you can grow your audience and build a sizable customer base.

Examples of promoting your brand through paid media channels cover television commercials , radio announcements , print, pay-per-click (PPC) advertising, advertising platforms (e.g. Google Ads, Bing Ads), and search engine marketing (SEM). Even specific aspects of social media, mainly sponsored ads for Facebook and Instagram, are a part of paid media.

More examples of paid media include:

- Shopping ads

- Display ads

- Retargeting

- Paid influencers

Gaining exposure by way of paid media is an excellent digital marketing strategy for raising brand awareness. The price of displaying your ads might be concerning, but the rewards are worth your investment. Your ads will eventually reach your target audience, allowing you to attract traffic , gain leads and boost sales.

Owned media is the second part of the POEM framework , and it is about everything under the ownership of your company, organisation, or brand. When it comes to owned media, you can use your assets and possessions for marketing purposes. You control your digital marketing channels, allowing you to promote your business online in any way you see fit.

Owned media consists of various assets under your ownership, such as your website, blog, print ads, and other promotional materials. You can use these assets to promote your products or services.

Examples of owned media include:

- Social media pages

Cost-effectiveness is your main advantage when it comes to owned media. Since you already own assets and possessions , there is no need to spend as much money as paid media marketing. However, maintaining your digital marketing outlets and channels will lead to incurred costs, so you still have to include your owned media expenses in your return on investment (ROI).

Versatility and longevity are additional benefits of owned media. You have total control over the way you handle your marketing assets. It allows you to maximise the effectiveness of your owned media marketing strategies as long as needed.

Earned media is the latest term in the POEM framework . It refers to the exposure and recognition your business is receiving due to organic publicity and awareness. With earned media, you can interact, connect, and communicate with your audience through third-party channels, such as social media, public relations (PR), and referrals.

You should know that most marketers classify earned media as inbound marketing. It is a process of gaining leads by distributing valuable content and securing conversions. Know that earned media is highly effective for digital marketing — as long as you continue to deliver quality and relevant content and engage with your target audience. Any hindrance to your marketing efforts may prevent your earned media from making substantial progress.

Managing your earned media is vital for establishing credibility and authority. If done right, you can analyse the impact of your marketing on your brand. It will help you think and plan better strategies to attract more traffic , gain leads and drive sales.

Examples of earned media include:

- Word-of-mouth marketing

- Viral marketing

- Press releases

- Brand awareness

Good thing you can promote your business through earned media channels in many ways. One excellent example is search engine optimisation (SEO). With SEO, you can improve your website’s online presence on organic search results. To do so, you have to optimise your website for SEO by getting quality backlinks and creating relevant content.

Similar to owned media, you can gain publicity without having to pay for ad space. Your earned media marketing efforts should extend your online reach. Once you have established your credibility, you can reach more people and build trust —that allows you to gain more exposure and recognition.

Part 2 – How To Use POEM Framework For Marketing?

When you divide the POEM framework into three separate categories, you will have different sets of effective marketing strategies for your business. Earn, owned, and paid media—all of these specialise in diverse aspects of your marketing campaign.

Here are some of the most effective marketing strategies that involve the use of the POEM framework .

List Of Marketing Strategies That Affect Poem

1. social media marketing.

Social media marketing covers all three categories of the POEM framework for many reasons. First, you can boost your paid ads on social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn to reach more people. As such, social media marketing falls under the paid media category.

Second, social media marketing is also a part of owned media since you can share and create content while using your very own social media page. The goal is to engage with potential customers and drive more traffic to your website. To do so, create quality and relevant content on your website that will capture the attention of your target audience and share it on social media to gain more brand exposure.

Lastly, sharing valuable content and engaging with customers on social media will help you raise brand awareness and gain exposure. As a result, you can earn publicity on social media to attract more potential customers. Examples of earned media on social media platforms include likes, shares, and comments.

Know that social media is the most versatile platform for digital marketing , as it affects paid, owned, and earned media. You can manage a social media page, deliver paid ads, and build a name for your business. All of these are attainable with the help of an effective social media marketing strategy.

LEARN MORE: How To Create A Social Media Marketing Campaign In 2021?

2. Influencer Marketing

Earned media is all about interacting with an audience through third-party channels. Fortunately, influencer marketing is the perfect strategy for doing just that. The goal of influencer marketing is to let a social media influencer endorse your products or services. Since they already have many followers and fans supporting them, more people would see your digital marketing campaign if you partner with one.

That is why influencer marketing is effective when it comes to engaging with an audience. Try finding an influencer who has the same target audience as you. The influencer can promote your business by showcasing your products on social media, both on your social media page and the influencer’s social media account.

When choosing an influencer for your marketing campaign, you have to consider the following factors:

- Who is their target audience

- How many followers and fans do they have

- If your brand and the type of content the influencer endorses is a good match

These days, the highly recommended social media platforms for influencer marketing are Instagram and TikTok since both have more than 1 billion users worldwide. That is why you can start from there if you want to engage with an active audience on social media. Also, make sure to choose the right influencer to establish your credibility and connect with more potential customers.

ALSO READ: How To Make An Effective Influencer Marketing Strategy?

3. Search Engine Optimisation (SEO)

In this day and age, having an SEO-friendly website is a must. SEO services are essential for driving organic traffic to your website. Optimise your website for SEO to increase your search engine rankings and attract more potential customers.

To obtain high-quality traffic for your website, optimise your content based on effective marketing strategies, such as link building and keyword research. Link building focuses on increasing the number of inbound links to your website, while keyword research is the method of finding relevant terms and phrases for your content.

With SEO , you have countless marketing opportunities to expand your online presence. For instance, you can create high-quality, SEO-friendly content for your website by using relevant keywords. Doing so should make your website more visible and searchable on search engines like Google and Bing.

SEO can also serve as your primary source of leads. Combine it with effective content marketing, and your online presence will grow in the long run. Other benefits of SEO marketing include:

- Achieve a higher conversion rate

- Establish credibility

- Raise brand awareness

- Rank higher on search engines

- Cater your website to mobile users

- Effectively measure search engine rankings

Search engine optimisation is ideal for achieving higher web visibility. You can attract more visitors as your search engine rankings increase over time. Remember to optimise your content from time to time to get more customers.

The only downside of SEO is that it can take a long time before you notice any results. Increasing your SEO rankings requires long-term planning and execution. You have to be patient and wait until your marketing efforts can make noticeable progress.

For more effective SEO strategies, get in touch with an SEO company in Singapore. Discover the perfect marketing strategy for your business with the help of a search engine optimisation specialist.

4. Search Engine Marketing (SEM)

Search engine marketing , also known as SEM , is an umbrella term that covers a wide range of promotional activities involving search engines such as Google, Yahoo!, and Bing. Unlike SEO, SEM is a paid marketing strategy. With search engines as your digital marketing platforms, you can upload your display ads to improve your web visibility and generate leads.

One part of SEM is PPC advertising, a digital marketing practice that marketers use to drive paid traffic to their websites. With PPC advertising, you will conduct keyword research and choose highly relevant keywords for your website. Afterwards, the next step is to bid on high-value keywords on Google Ads to get your ads on top of a search engine results page (SERP).

Most marketers use online advertising platforms such as Google Ads and Amazon Advertising to launch their PPC advertising campaigns. Each time someone clicks on your ads, you will have to pay for your chosen advertising platform.

As a paid media channel, Google Ads is one of your best choices available. It is a highly effective platform for gaining leads and targeting prospects. By earning enough clicks, you can direct as many people as possible to your website, allowing you to convert leads to sales.

Not to mention, SEM is highly scalable, meaning you have total control over your budget. That is why you should use this to your advantage to obtain a high quality of paid traffic for your website.

5. Content Marketing

To apply the first and second categories of the POEM framework , use content marketing practices to promote your business, engage with your target audience, and boost your search engine rankings . Your content marketing efforts shall nurture traffic and leads as time progresses, as long as you maintain a stable relationship with potential customers.

Know that content marketing is an effective digital marketing strategy that involves paid, owned, and earned media channels and assets. You can share quality content with your customers to earn their trust. To extend your reach, try using paid content promotional tactics that can generate your ROI.

Examples of content marketing assets include:

- Whitepapers

- Case studies

- Infographics

- eBooks (e.g., epub, PDF)

With content marketing , you have a wide range of assets at your disposal. Besides creating written content for blog posts or whitepapers, you can produce videos to showcase valuable information about your business or relevant topics.

Content marketing is essential for building trust and increasing search engine rankings . Unlike traditional advertising, the purpose of content marketing is to forge relationships and connect with potential customers. Once you earn their trust, you can subtly persuade them to engage with your business even further, like making a purchase or sharing your content with others.

6. Viral Marketing

For your digital marketing efforts to succeed in earned media, you have to generate publicity and attract attention. The best way to do so is by conducting a viral marketing campaign.

Viral marketing is a business strategy that aims to spread information in the fastest way possible, either through word-of-mouth or the Internet. A successful viral marketing campaign starts by staying up to date with the latest trends. Utilise some of the latest trends for your ads to connect with your audience.

Most successful viral campaigns happen by accident. Any digital marketing campaign is viewed as viral as long as it has reached thousands or millions of people in a short time . The trick here is to create viral content is to share information with a high probability of being spread by your audience.

For example, Google Android released a viral commercial in 2015 that showcases a compilation of short clips presenting various animals huddled together. Despite the brand logo of Android appearing for only two seconds, the commercial garnered millions of views almost instantly. Google Android’s digital marketing campaign is still popular up to this day.

The low-budget commercial succeeded in appealing to a broad audience that consists of animal lovers. Even today, the commercial is still receiving a ton of attention, with many viewers appreciating the heartwarming concept and theme.

Creating a successful viral marketing campaign is probably one of the hardest things to do. There is no secret recipe for success, but you can incorporate themes such as humour and drama with your digital marketing campaign to make it more appealing and attract the attention of your target audience.

For more examples of viral marketing campaigns, read this article . By looking at these examples, you might gain ideas on what you should do to produce a viral marketing campaign for your brand.

7. Email Marketing

Until today, email marketing remains to be an effective strategy for building trust and connecting with customers. You can send quality content via emails to welcome customers to your business, share updates about your products and services, and even give out exclusive promotions.

The best part is that you can incorporate email marketing with PPC advertising by using paid search to grow your list of email subscribers. Doing so would help increase your customer base and reach.

For instance, consider putting a call to action (CTA) in your paid ads that encourage users to send you an email. Make your CTA engaging to encourage more users to contact your business via email.

KNOW MORE : A Beginner’s Guide To Email Marketing

Email marketing is also cost-effective. If your email marketing strategy succeeds, it can deliver the highest ROI compared to other forms of marketing. According to a study from Litmus, email marketing generates $36 of every $1 spent. That means that ROI you gain is 3,600% times more—making it one of the most effective digital marketing strategies.

Here are the other benefits of email marketing include:

- Connect with potential customers

- It is highly measurable

- Ideal for small businesses

- Provide customers with personalised content

ALSO READ: Email Marketing: Tips, Tricks, And Mistakes

Part 3 – The Pros And Cons Of Poem Framework

The POEM framework should serve as a guide for your digital marketing strategies. By sticking to only one marketing channel, you will be less likely to reach your target audience. That is why you should try combining all three parts of the POEM framework so you can get the best results out of your digital marketing campaign.

Also, the POEM framework is becoming more relevant as digital marketing continues to evolve. Over time, transformations happen in the marketing industry that will change the landscape forever. Know that the way people handle business today may not be the same in the next few years, so understanding the current POEM framework is vital for your marketing success.

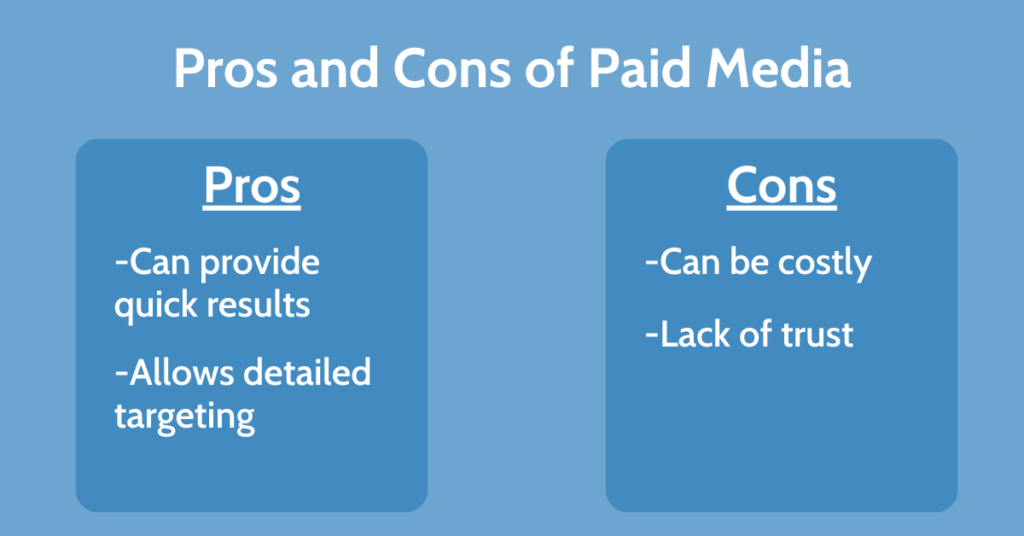

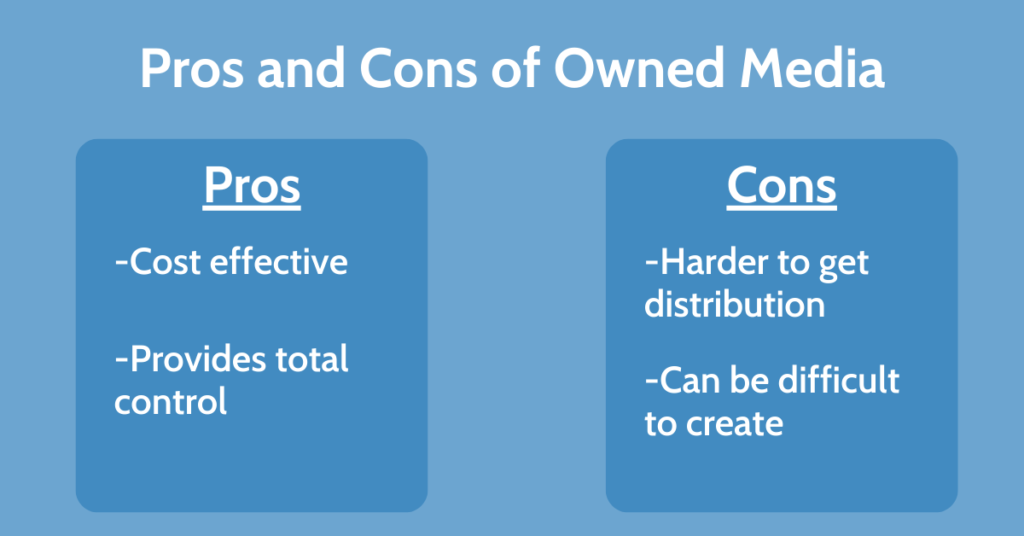

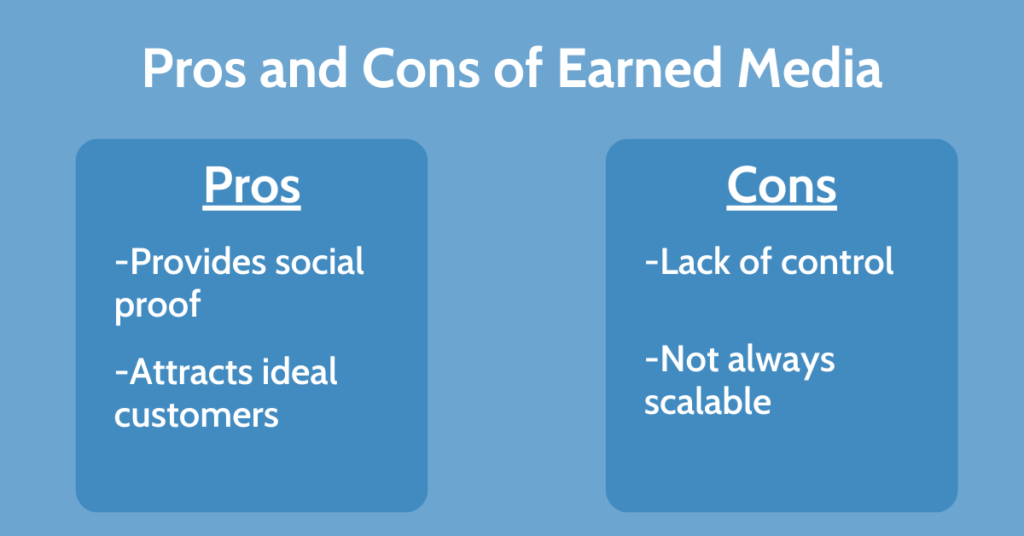

Each category of the POEM framework offers unique advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, better gain an understanding of what the POEM framework is so you would know where your brand should stand.

Check out the pros and cons of paid, owned, and earned media.

The Future Of Poem

It is only a matter of time until the POEM framework in digital marketing will transform into something bigger and better. The Internet age has already passed, providing people with social media, mobile devices, and many more blessings to help marketers promote products and services. As a result, the POEM framework has changed for the better.

Keep the POEM framework in mind whenever you create an effective digital marketing strategy in Singapore for your business. Try to cover all marketing channels, especially the three categories of the POEM framework : paid, owned, and earned media channels, as much as possible.

For more tips and tricks about digital marketing , get in touch with our award winning digital marketing agency in Singapore . Contact OOm today at 6391-0930.

Share This Article

Related posts, the dangers of duplicate content for seo, seo competitive analysis: how to analyse your competition, content marketing: top 10 trends this 2023.

Posted by Leyda Gandeza

Guide to Core Web Vitals in 2023

Posted by adm_oom

What is Social Media Optimisation (SMO)?

Posted by Dennet Macorol

Ready to Elevate your Business to the Next Level?

Discover how we can help you to achieve your business goals through digital marketing in just 30 minutes.

Call us today to schedule your free review or to learn more about our services:

Or contact us online and we will quickly respond to you:

PSG for E-Commerce and Digital Marketing Solutions (Up to 70%* Support)

Fill in the form below for a free consultation. We will contact you shortly.

*Only SMEs in retail sectors are eligible for 80% support until 31 March 2023

Privacy Overview

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. These cookies ensure basic functionalities and security features of the website, anonymously.

Functional cookies help to perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collect feedbacks, and other third-party features.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with relevant ads and marketing campaigns. These cookies track visitors across websites and collect information to provide customized ads.

Other uncategorized cookies are those that are being analyzed and have not been classified into a category as yet.

Table of Contents

Poem framework in digital marketing.

Did you ever think that a poem could help your business grow? We’re not talking about the kind with rhymes and stanzas. We’re talking about the POEM framework for digital marketing.

POEM digital marketing framework

The POEM model is a digital marketing framework that helps marketers plan their efforts to achieve business goals. POEM stands for paid, owned, and earned media. This model helps identify the types of content used in a marketing campaign.

Businesses use the POEM framework to get more attention, generate more online traffic, and make more sales.

Let’s dive into these different types of media and learn how they work together to create a complete strategy .

The “P” in POEM stands for Paid Media. As the name suggests, paid media involves distribution that you pay for. It includes sponsored advertising in various places across the internet. Any time when you exchange money to put your message in front of people, that’s paid media.

Examples of paid media

Paid media can come in many different forms. Some common examples of paid media include:

- Facebook ads

- Google search ads

- Display ads

- Sponsored influencer posts

Offline, paid media could include billboards, radio spots, and television advertisements.

Benefits of paid media

One of the main benefits of paid media is its ability to target specific users with a specific message. Platforms like Facebook and Google have billions of data points that they’ve collected that will help you reach a specific audience. These companies offer you the opportunity to advertise to the exact demographic or psychographic group that you’re interested in.

Influencer marketing also allows you to reach a specific audience. For example, if you want to target people interested in yoga, you’d work with a yoga influencer. This influencer would have an engaged audience of yoga that you want to reach.

Another benefit of paid media is that it can help jumpstart your marketing efforts. Owned and earned media take longer to reach the ideal audience and produce results. Paid media cuts down on that time by getting directly in front of the eyeballs you want.

Paid media offers another advantage for businesses when it comes to PPC advertising. With this approach, advertisers only pay when someone actually clicks on their ad. This helps businesses manage their costs and get a good ROI.

Drawbacks of paid media

One of the main drawbacks of paid media is just that. It’s paid. This means that you’ll always have to spend money to get your message out there. This can be an issue for businesses that are starting out. Not every business has the budget to invest in paid media.

Another potential drawback of paid media is ad blindness. Ad blindness occurs when someone simply ignores things that they know are advertisements. Think of how many times you’ve been on a website with banner ads and looked right past them to the content you actually want to see.

People don’t always like being sold things. Even if your product or service would be perfect for someone, they could ignore your message because they don’t trust ads.

Owned media

The “O” in POEM stands for owned media. Owned media includes all the assets that your business owns and controls.

Examples of owned media

Owned media can be one of the best ways to promote your product or service. Some of the best examples of owned media are:

- Email lists

- Mobile apps

Benefits of owned media

The two greatest benefits of owned media assets are freedom and control. You can make them how you want and do with them what you please. This isn’t always the case with paid and earned media.

The possibilities are endless when it comes to owned media. You can have your website designed to your exact specifications . You can send whatever message you want to people on your email list. This isn’t always true when it comes to a business’s social media profile, for example.

Platforms like Facebook and Twitter have terms of service . You can only use the platforms on their terms. If you stray from those, they have the right to throttle your reach or even delete your account.

That may be an extreme example, but it’s important to consider who’s really in charge of the platforms that you’re using.

Another benefit of owned media is that it’s cost-effective. You don’t need to fork money over to advertising platforms to create it.

Drawbacks of owned media

One of the drawbacks of owned media is that it can be hard to get distribution for it. No matter how great your website is, if you can’t get the right eyeballs on it, it won’t make a difference for your business.

Another downside to owned media is that it can be difficult to create and manage. Designing an awesome website or developing a slick mobile app is a big undertaking. Not everyone has the time and talent to create and continually update owned media.

Earned media

The “E” in POEM stands for earned media. Earned media is exposure that a business receives as a result of organic attention. The best way to increase earned media is to create valuable content that people want to share.

Many marketers consider earned media to be inbound marketing. This is because the content attracts potential customers to your business without you doing outreach (outbound marketing).

Examples of earned media

- Word-of-mouth

- Viral marketing

- Search engine optimization

Benefits of earned media

A benefit of earned media is that it can attract potential customers to your brand without you having to go out searching for them. Earned media works like a magnet, attracting the right kind of people to your business. You know that these people are more likely to buy your product or service because something you’ve made has already resonated with them.

Earned media also helps increase your credibility. If lots of people are talking about and sharing your business, that buzz means something. Earned media can help you position yourself as an expert within your niche.

Drawbacks of earned media

One drawback of earned media is that you don’t necessarily have control over it. You can make awesome social media posts and do great work, but that doesn’t guarantee that people will talk about your business. You can do your best to create content that resonates, but it’s ultimately up to the people to decide whether or not to engage with or share it.

Another drawback when it comes to earned media is that it can be hard to replicate. If you are fortunate enough to “go viral,” it’s hard to strike gold twice. Because you don’t have a lot of control and don’t always know what will be a hit, earned media isn’t always scalable.

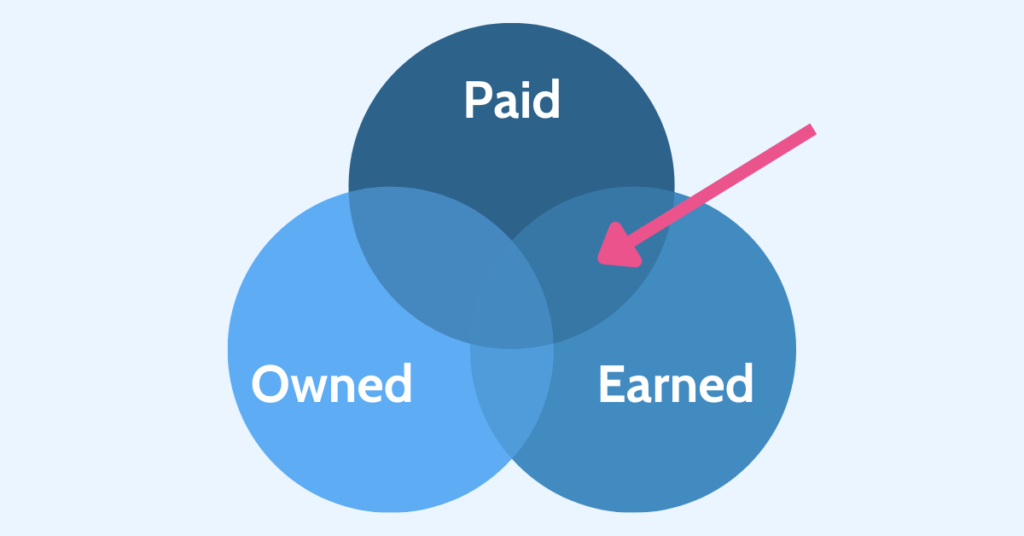

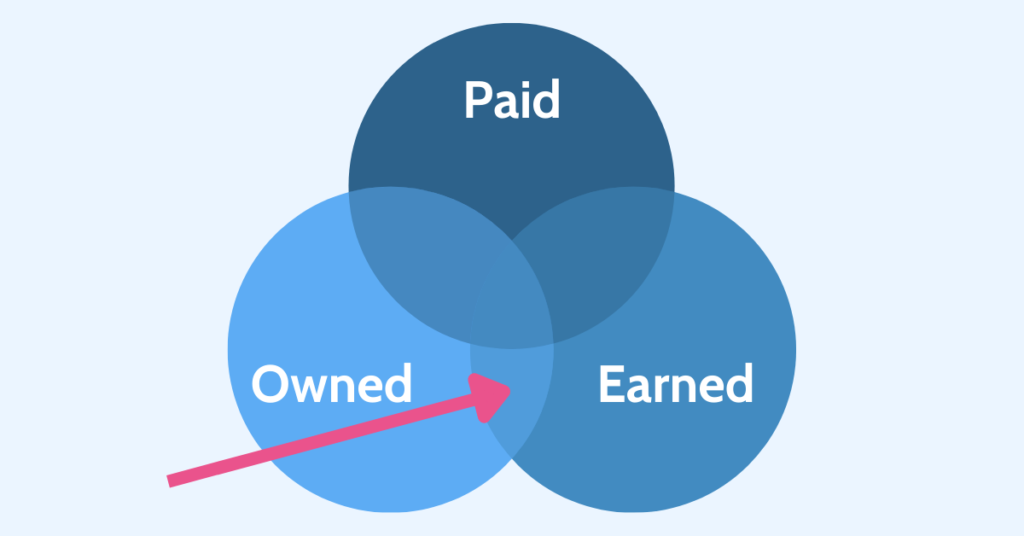

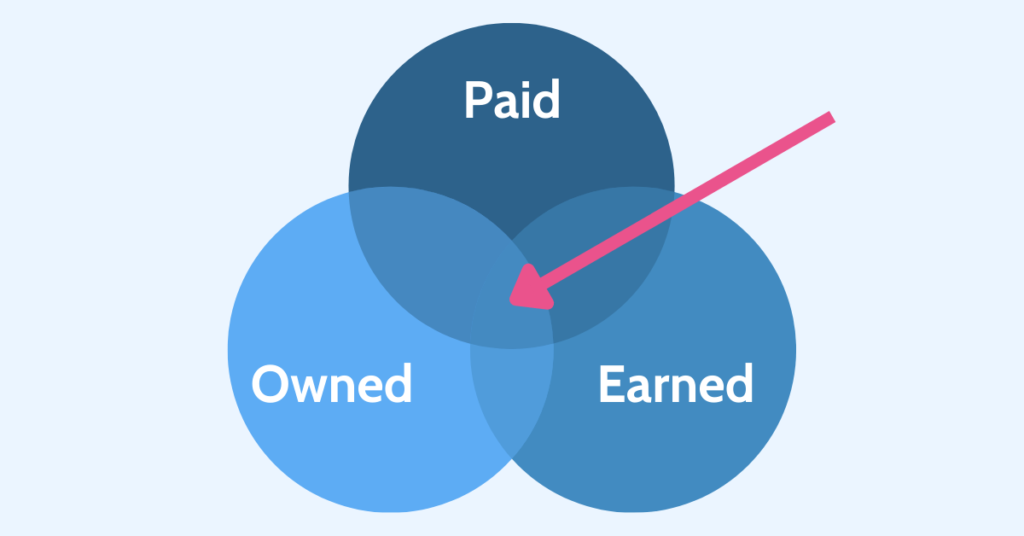

Combining paid, owned, and earned media

None of the parts of POEM operate in a vacuum. Sometimes the lines between them blur and they become difficult to distinguish. The best marketing results come when you combine these types of media.

Paid + owned media

One way that you could combine paid and owned media would be through PPC ads that lead to an email sign-up form on your website. You would use paid media to attract potential customers and then add them to your email list, which is part of your owned media.

Paid + earned media

An example of combining paid and earned media is boosting an organic Facebook post that received a lot of engagement . The reach that the post earned thanks to people interacting with it would be supplemented by the paid distribution that it receives.

Owned + earned media

Owned and earned media work together when you create valuable content on your website. Helpful blog posts or infographics are pieces of owned media that can be shared to drive earned media traffic.

Paid, owned, + earned media

The best marketing happens when paid, owned, and earned media all support each other. Each part of the POEM framework is more effective when the other pieces are playing a role. A campaign in which each piece of the POEM model is complimenting the other pieces is the digital marketing trifecta.

Sometimes, the strategy starts with owned, then moves to earned, and finally ends with paid media. In this case, you would create a compelling piece of content (owned), which would drive social shares and traction (earned), and then sponsor posts or run ads using that asset because you already know it resonates (paid).

You could also start from a different direction. A marketer could use Google ads (paid) to get in front of the right audience and attract them to a blog post on your website (owned) that people would share with their friends because they found it valuable (earned).

Take advantage of the POEM model in your digital marketing

The POEM framework helps us understand that digital marketing is a multifaceted process. A well-rounded marketing strategy involves paid, owned, and earned media. If you don’t take the opportunity to combine all three, you’re likely leaving money on the table.

How is your business doing online?

Get your free online report card to see how your business is performing based on seven key categories!

Coffee Shop Website Inspiration from All 50 States

Wouldn’t you love to go on a coffee shop tour of the whole United States? There are certain things that every coffee

Digital Advertising for Coffee Shops

There are tons of different ways to spread the word about your coffee shop. However, not all methods are created equal. Digital

12 Social Media Tips for Coffee Shops

You know that social media marketing is one of the most important digital marketing strategies for coffee shops. But this strategy is

About the author

James Schweizer

About marketing backend.

Marketing Backend is an all-in-one software solution designed to help your business grow. Through efficiency and a single platform for all of your marketing needs, our SaaS provides the most future-proof solution for your organization.

- (502) 512-3710

- 251 Marsee Trail, Corbin, KY 40701

All rights reserved © 2024

Get your free online report card!

We’ll check out your website and then look at all the other places your business appears online. After that, you’ll receive a report that shows you how well your business is doing on the internet. You’ll also get some quick tips on how you could improve!

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.4: Case Study - A Close Reading of a Poem

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40427

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Image from Pixabay

How to Conduct a Close Reading of a Poem

The title matters.

Reading a poem, we start at the beginning — the title, which we allow to set up an expectation for the poem in us. A title can set a mood or tone, or ground us in a setting, persona, or time. It is the doorway into the poem. It prepares us for what follows.

Exercise 6.4.1

Read the titles of the poems that follow. What do the titles bring up for you? Discuss your findings.

- Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening

- Wishes for Sons

- Riot Act, April 29, 1992

- Reckless Sonnet

- Pissing Off the Back of the Boat into the Nivernais Canal

- How Much Is This Poem Going to Cost Me?

- Girl Friend Poem #3

- Sex at Noon Taxes

- The Tree of Personal Effort

- The First Time Through

Upon a first reading, it’s important to get an idea of what it is you are entering. Read the poem out loud. Listen for the general, larger qualities of the poem like tone, mood, and style. Look up any words you cannot define. Circle any phrases that you don’t understand and mark any that stand out to you. Some questions we may ask ourselves include:

- What is my first emotional reaction to the poem?

- Is this poem telling a story? Sharing thoughts? Playing with language experimentally? Is it exploring one’s feelings or perceptions? Is it describing something?

- Abrasive, accepting, admiring, adoring, angry, anxious, apologetic, apprehensive, argumentative, awe-struck

- Biting, bitter, blissful, boastful

- Candid, childish, child-like, clipped, cold, complimentary, condescending, critical

- Despairing, detached, didactic, direct, discouraged, doubtful, dramatic

- Fearful, forceful, frightened

- Happy, heavy-hearted, horrified, humorous

- Indifferent, ironic, irreverent

- Melancholic, mysterious

- Naïve, nostalgic

- Objective, optimistic, peaceful, pessimistic, playful, proud

- Questioning

- Reflective, reminiscent

- Sad, sarcastic, satirical, satisfied, seductive, self-critical, self-mocking, sexy, shocked, silly, sly, solemn, somber, stunned, subdued, sweet, sympathetic

- Thoughtful, threatening

- Uncertain, urgent

These initial questions will emotionally prepare you to be a good listener. When we come to a text, though we release ourselves of any preconceived judgments, we do come prepared emotionally. Picking up a book of fiction is different than opening a book of nonfiction essays. Within us there is an ever-so-slight yet important preparation. Think about it. Although both nonfiction and fiction share similar writing tropes, how would you feel if someone told you that the nonfiction book you are reading—the one that brought you to tears—is not nonfiction, but actually fiction? Most people become upset. It feels like you’ve been lied to. To put it another way, think about how differently you prepare to engage with a performance depending on its genre. How do you set yourself up differently for a stand-up comic as opposed to an opera? Not only are the effects of the performance different, but the way we emotionally prepare ourselves to receive them is also different.

Let’s begin to apply our approaches to the following poem by Stephen Dunn:

Poem: The Insistence of Beauty by Stephen Dunn

The day before those silver planes came out of the perfect blue, I was struck by the beauty of pollution rising from smokestacks near Newark, gray and white ribbons of it on their way to evanescence.

And at impact, no doubt, certain beholders and believers from another part of the world must have seen what appeared gorgeous— the flames of something theirs being born.

I watched for hours—mesmerized— that willful collision replayed, the better man in me not yielding, then yielding to revenge’s sweet surge.

The next day there was a photograph of dust and smoke ghosting a street, and another of a man you couldn’t be sure was fear-frozen or dead or made of stone,

and for a while I was pleased to admire the intensity—or was it the coldness?— of each photographer’s good eye. For years I’d taken pride in resisting

the obvious—sunsets, snowy peaks, a starlet’s face—yet had come to realize even those, seen just right, can have their edgy place. And the sentimental,

beauty’s sloppy cousin, that enemy, can’t it have a place too? Doesn’t a tear deserve a close-up? When word came of a fireman

who hid in the rubble so his dispirited search dog could have someone to find, I repeated it to everyone I knew. I did this for myself, not for community or beauty’s sake, yet soon it had a rhythm and a frame.

“The Insistence of Beauty,” from THE INSISTENCE OF BEAUTY: POEMS by Stephen Dunn. Copyright © 2004 by Stephen Dunn. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Begin with the title: “The Insistence of Beauty.” What does this title do to you? What kind of expectations and tone does it set up?

Perhaps you expect a poem about beauty, or because it is the “insistence of” you may feel determination, or like beauty is up against some other force. Or maybe you expect a poem about art.

Then ask and begin to answer these questions:

- There is no one answer to this, obviously. But maybe you feel loss. Or hope. Or desperation. Or sadness. Or admiration. Maybe you’re confused or feel a combination of these.

- This poem seems to be telling a story. The poem contains a sequence of events: “The day before”; “I watched for hours”; “the next day.” The speaker is sharing emotional reactions to something, as well as his actions to an event.

- It seems serious, inquisitive, and confessional. It’s not humorous and isn’t experimental.

Images and Tone

After an initial introduction to the poem, read slowly and allow the meanings to emerge as you move from line to line, paying attention next to images and tone . Before moving ahead, ask what your emotional response is at the end of each line, as lines can create different meanings and give the poem complexity. For instance, in the following stanza, we respond one way to the first two lines’ image, and another way after its turn to the third line:

The day before those silver planes came out of the perfect blue, I was struck by the beauty of pollution rising from smokestacks near Newark

In the second line, the phrase “I was struck” forms an image with what precedes before it can form an image with what follows. This second line leaves us with the image of the speaker being struck by something. It might be different for you, but because I am holding the image of a plane in my mind, a plane being a large and physical object, I immediately imagine the speaker being “struck” physically by an object. Therefore, we momentarily hold the image of being struck physically: “The day before those silver planes / came out of the perfect blue, I was struck.”

But when we move to the third line, the image changes. The speaker is no longer struck by an object , but by an emotion or idea: the “beauty of pollution rising.” Although we may think of pollution as ugly, here we are being told that it is beautiful. The word reverses our assumptions; maybe we see in our mind’s eye the cliché image of smog rising from smokestacks and ask, “How is that beautiful?” Or maybe we think about how smog makes the colors of sunsets more intense. Either way, the speaker is telling us that he sees pollution as beautiful even with all of its complications (it’s harmful, smelly, ugly, et cetera). Rather than leave us with only the speaker’s judgement of pollution, the next lines create for us an image of that “beauty” so we can see it, too: “gray and white ribbons of it / on their way to evanescence.” These last two lines help us make sense of the idea that pollution is beautiful. The ribbons evaporating maybe are somehow beautiful. If we disconnect our knowledge from the image so we do not think about how the ribbons are smoke, if we simply see the visual the smoke makes: “ribbons… on their way to evanescence,” we experience what the speaker experiences: beauty. Or, perhaps, what the speaker sees as beautiful is the pollution disappearing. From this perspective, the speaker would see not the gray and white ribbons as beautiful, but the gray and white ribbons disappearing as beautiful.

Tonally, the words “perfect” and “struck” stand out for different reasons in the first two lines — one for meaning, one for sound. When something is “perfect” we feel admiration, maybe the need to protect it. Since nothing really is perfect, it also sounds a little romantic, subjective, or too good to be true, which may also produce tension as we know perfection isn’t real, or doesn’t last. The word “struck” is a harsh, violent, physical word. And ending the line on it emphasizes it even more. To be struck by something suggests shock, surprise, immediacy, and change.

In addition to these two words, the first phrase sets a tone, too, of expectation. We know something significant is being made of the planes because they are marking a day: “The day before those silver planes.” The event is important enough to refer to it in such a way. This is how we speak of big events. The day we were married. The day we went swimming. The day those silver planes came out of the blue.

The tone in the first stanza immediately produces a connection between the speaker and reader. We feel the speaker is disclosing something to us, or divulging something important. As we continue through the poem the speaker’s tone becomes inquisitive as he asks questions:

—or was it the coldness?—

that enemy, can’t it have a place too?

Doesn’t a tear deserve a close-up?

Is he asking questions of the reader? To himself? A bit of both? We journey with him on his seeking.

Read through Dunn’s poem and identify the rest of the images. Discuss how each image makes you feel. To what words or images is your attention drawn? What associations do you make from them?

Find Connections and Ask Questions

After moving through the poem and noting images, their effects, and the tone or places where tone changes, the next question that is helpful to ask is: What does x remind me of? Or, what associations am I making? Usually the connections I would suggest making would be within the poem itself and the patterns it creates—between lines, images, repetitive words or themes, diction (word choice)—but in Dunn’s poem, before we can make connections within the poem, we are actually reminded of something outside of the poem. In the first stanza, the two planes near Newark and two ribbons evaporating may remind you of the iconic image of the September 11th attacks on The World Trade Center in New York City. This an allusion (an indirect reference) to that event, as suggested by the second stanza: “believers from another part of the world / must have seen what appeared to be gorgeous.” Making this connection provides us with a context for the poem’s occasion. Maybe we begin to ask, “How can the attacks on the World Trade Center and its subsequent collapse be seen as gorgeous?”

You may be wondering what happens if you didn’t make that connection. Will you misread Dunn’s poem? In a poem, allusions like this usually aren’t usually necessary if the poem makes use of all the other elements of poetry successfully. And in Dunn’s poem we are actually given enough, I would say, to have a sufficient experience if the allusion isn’t made. In the poem the planes cause an “impact,” believers elsewhere watch the “flames of something of theirs being born,” the speaker watches “mesmerized,” the media posts photographs of the fearful and “dead or made of stone” watching the events; then the poem focuses on the speaker’s emotional reactions and thoughts regarding the event, and what thoughts it evokes within him in regard to beauty. The poem closes with the story of the fireman and his dog and the speaker’s insights. Looking at it this way, maybe 9/11 is secondary in experiencing the poem. It’s hard to be certain since I cannot not make the connection to the event personally, but perhaps it is possible that the allusion is not central to the poem’s experience, since it is all of the other poetic techniques of the poem that create the sensual reaction in the reader.

Let’s for a moment pretend that the poem isn’t alluding to these events. This will leave us to focus on the private and unique universe of the poem and make connections within it. If we begin to make connections within the poem itself, one of the first connections we might make is how the ribbons in the first stanza appear beautiful to the speaker even though they are pollution, and how the flames in the second stanza appear “gorgeous” to the believers even though they are destructive. What does that suggest? The connection bridges the distance between the speaker and the believers, as they both have the capacity to see beauty in something harmful, in something that others see as ugly. This further suggests that beauty is subjective, though the ability to see it is universal.

You can see how making connections like this and asking questions about those connections can lead to insight into the poem’s experience, as well as insight into the experience of being human. Here, Dunn’s speaker has found similarities between himself and people who might be considered enemies. Beauty, we see, may be received and interpreted by our senses and not rely on context.

What other connections and patterns can we see? And what questions can these patterns raise in us? In the third stanza the speaker watches the collision “replayed”—be it on a television screen or in his mind—and admits to a desire for revenge. Later, in the last stanza, the speaker repeats the story of the fireman: “I repeated it / to everyone I knew.” What does this suggest? He says “I did this for myself, / not for community or beauty’s sake, / yet soon it had a rhythm and a frame.” How are we to understand the impact of his repeating his story? If it is told “for myself,” then what exactly is the speaker getting from this and how is it connected to the replaying of the collision? What might be meant by rhythm and frame?

In the fourth and fifth stanza the speaker makes a connection between himself admiring “the intensity” of the people in the photographs and between the photographers taking the photographs:

and for a while I was pleased to admire the intensity—or was it the coldness?— of each photographer’s good eye.

The speaker asks, “Was it the coldness?” This seems to suggest a distance, or emotional coldness, in the voyeuristic qualities he is experiencing and the way photographers act as objective eyes for the audience. The photographers cannot act on their emotions or empathies; instead, to succeed, photographers in intense situations must shut down their responses and capture the moment visually, detached from their emotions. The speaker says that he admires this, “the intensity—or was it the coldness?— / of each photographer’s good eye.” Perhaps he sees courage in the act of taking these photographs, or maybe he sees something admirable in the way a person can detach himself from an event in order to focus only on the image, the visual, the camera’s eye with a “good eye” that can see art and capture it.

In the fifth and sixth stanzas, the speaker muses on how he’s reacted to beautiful things in the past just as coldly as these photographers: “For years I’d taken pride in resisting / the obvious—sunsets, snowy peaks, / a starlet’s face.” The pattern of “coldness” is established by several word choices here: “fear-frozen,” “coldness,” “snowy.” The words are used as physical description and emotional description. They are literal, and they are figurative. Our speaker then tells us how he discovered that images of “sunsets, snowy peaks, / a starlet’s face,” too, have their “edgy” place. This is a little mysterious. Does “edgy” refer to the destructive, ugly yet mesmerizing collision and photographs he’s been viewing? Is this suggesting that serene beauty and edginess are somehow closely related?

The speaker then introduces the idea of “the sentimental,” which he refers to as “beauty’s sloppy cousin, the enemy,” and asks if it can have a place to also be appreciated. The word choice of “enemy” is interesting, as it echoes the relationship between the speaker and the believers from the beginning of the poem. What does this suggest about the relationship between enemies, and between the roles they play? The speaker ends the stanza with another question: “Doesn’t a tear deserve a close-up?” The image represents sentimentality, beauty’s “sloppy cousin,” but it actually could be another allusion, this time to a commercial by the Keep America Beautiful campaign, made in the 1970s at the start of the environmental movement. It is another reference that will not diminish the poem’s effect on a reader if he or she doesn’t know it, but it can add another layer of complexity if it is understood. In a commercial, a Native American witnesses the pollution of a river as he paddles a canoe up the river, and as he turns to the camera, we zoom in on a tear slipping from his eye. The allusion echoes the pollution that the speaker found beautiful in the first stanza.

In the last part of the poem, the speaker confesses that he retells the story about the fireman hiding in the rubble “so his dispirited search dog / could have someone to find.” And that he retells it not “ for community or beauty’s sake,” but for himself. Why would he do that? Why does it matter that he does? The story is moving. Who isn’t moved by the relationship between a man and his dog? Our focus shifts from all of the people who perished in the rubble whom the fireman and his dog cannot help, to the “dispirited” feelings of the dog that the fireman tries to help. It is almost as if all the devastating emotion we feel thinking about those people and their families, empathizing with them, transfers to the emotion we feel thinking about the dog, empathizing with the fireman who feels such empathy and emotion for the dog that he hides in the rubble so the dog can find someone. In this moment, the feelings the dog has become as important and as worthy as our own—a dog’s emotions equate with a human’s. If we can feel such strong empathy toward the dog, as the fireman clearly does, can we not also feel it toward our enemies? And are these feelings in any way similar to “revenge’s sweet surge,” referred to earlier in the poem? Are they maybe one side and the other, sloppy cousins of each other like beauty and sentimentality? Or is the dog and fireman story too sentimental to fall in love with? And if it is, doesn’t it “deserve a close-up” too?

Look Closely at Diction

When reading a poem, you should always look up words you do not know, but sometimes it can help to look up words that you do know when they have more than one meaning, too. The last line of the poem may seem a bit mysterious: “I did this for myself, / not for community or beauty’s sake, / yet soon it had a rhythm and a frame.” A rhythm and a frame? What on earth does that have to do with anything? Is the speaker suggesting that beauty relies somehow on rhythm and a frame? We can begin by looking in the poem for other things that have rhythm and a frame. The poem itself, does, for starters. Poetry has rhythm. Speech has rhythm. And the images of the building collapsing repetitively have a rhythm too, as well as a frame if they are being shown on television, captured through a camera lens. But “frame” is a word with many meanings. If we look at the word “frame,” we find that it is a noun defined as:

- a border or case for enclosing a picture, mirror, etc.

- a rigid structure formed of relatively slender pieces, joined so as to surround sizable empty spaces or nonstructural panels, and generally used as a major support in building or engineering works, machinery, furniture, etc.

- a body, especially a human body, with reference to its size or build; physique: He has a large frame.

- a structure for admitting or enclosing something: a window frame.

- usually, frames. ( used with a plural verb ) the framework for a pair of eyeglasses.

- form, constitution, or structure in general; system; order.

- a particular state, as of the mind: an unhappy frame of mind.

In looking at the above definitions, there are several that have resonance in relation to this poem.

- We frame art and other works of beauty, and the title of the poem is “The Insistence of Beauty.” What is the purpose of a frame in this sense of the word?

- The World Trade Center, like all buildings, had a frame, which was destroyed in the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Were the Twin Towers a piece of art that had beauty and a frame? What did they represent symbolically?

- All people—no matter what their culture or nationality—and other living beings have frames.

- Poems have form; society has systems; the United States has a Constitution; the 9/11 terrorist attacks were very orderly and systematic. How is beauty linked to order?

- A poem’s speaker has a state of mind, as does the reader; the events of 9/11 place us in a certain “frame of mind.” What frame of mind is the reader in? What frame of mind does the poem put the reader in?

The word “frame” adds layers of meaning that can contribute to our interpretations, reactions, and understandings of this poem, as the word relates to many of the poem’s themes: beauty, violence, love, destruction, storytelling, and the visual nature of art, to name a few. Considering these definitions, we might follow our thoughts to conclude something like this:

“Frame” can refer to the building’s architecture, the human body, systems, and orders. We frame photographs—a single moment captured from time—and hang them on our walls. A frame lends support, gives something its shape. And rhythm? Our first rhythm: our mother’s heartbeat—rhythm is elemental and basic. It is the basis of music and poetry. The human body finds rhythms pleasing. Rhythms repeat themselves. The man telling the story of the fireman and his dog creates a rhythm through its repetition; it becomes artful, monumental. It becomes an experience shared rather than isolated. It stands as a symbol, an allegory for the wreckage of person, animal, and city. Perhaps the retelling becomes its own type of architecture that listeners can enter, or the bones within someone, like the fireman, who in retelling this story finds strength and support.

What is your experience of this poem? How do you interpret its meaning? After discussing your reactions to the poem, discuss the specific approaches you used to come to your interpretation. What do you think is the most powerful part of the poem? What, if anything, confused you in its reading? Did that change once you conducted a closer reading of the poem? Did your interpretation align with mine in some places? Or are there sections in which it differed? Remember, there is no one way to interpret a poem. That’s what makes discussing them so pleasing and rewarding.

Read the poem by Wordsworth below aloud the first time to hear the sound of the words and the brief pauses with each line break. Each and every word, every punctuation mark is deliberately chosen by the poet, so read thoughtfully and carefully. You can also use " Those Winter Sundays " by Robert Hayden or "Catch" by Robert Francis.

I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud by William Wordsworth

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

2) Go through the same process the author used to read Stephen Dunn's poem to do a close reading of Wordsworth's poem. What is your first emotional reaction to the poem? Next, follow the steps below to do a close reading.

- What does this title do to you? What kind of expectations and tone does it set up?

- What do you notice about the structure of the poem?

- How are the lines organized differently than prose? Where do they break?

- What do you notice about the last word of each line?

- Is this poem telling a story? Sharing thoughts? Playing with language experimentally?

- Is the tone serious? Funny? Meditative?

- Read through and identify the images in the poem and also the tone and places where the tone changes. Discuss how each image makes you feel. To what words or images is your attention drawn? What associations do you make from them?

- Find connections and ask questions. What does x remind me of? Or, what associations am I making? What other connections and patterns can we see?

- Look closely at diction or word choice, especially as the connotative and denotative meanings of words.

- What do you think is the most powerful part of the poem?

- What, if anything, confused you in its reading? Did that change once you conducted a closer reading of the poem?

- What is your experience of this poem? How do you interpret its meaning? What are the specific approaches you used to come to your interpretation?

- Now, read the poem in your own mind again once or twice. Pause at each word that “jumps” out at you because it is either an unusual image or it elicits a mood, or it could just be that you don’t know the meaning of the word and will need to refer to a dictionary.

- Note recurring ideas or images—color code these with highlighters for visual recognition as you look at the poem on the page.

- Determine formal patterns. Is there a regular rhythm? How would you describe it? Can it be characterized by the number of syllables in each line? If not, do you note a certain number of beats (moments where your voice emphasizes the sound) in the line? Are there rhyming sounds? Where do they occur?

- What is the overarching effect of all these elements taken together? What do you think is the message conveyed by the poem?

As you learn more about the elements of poetry, you will be looking at word choices a poet makes and also changes in tone. Are there any figures of speech the poet uses? What is the form of the poem? Each of these contributes to the overall meaning of a poem.

Contributors and Attributions

Adapted from Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations by Michelle Bonczek Evory under the license CC BY-NC-SA

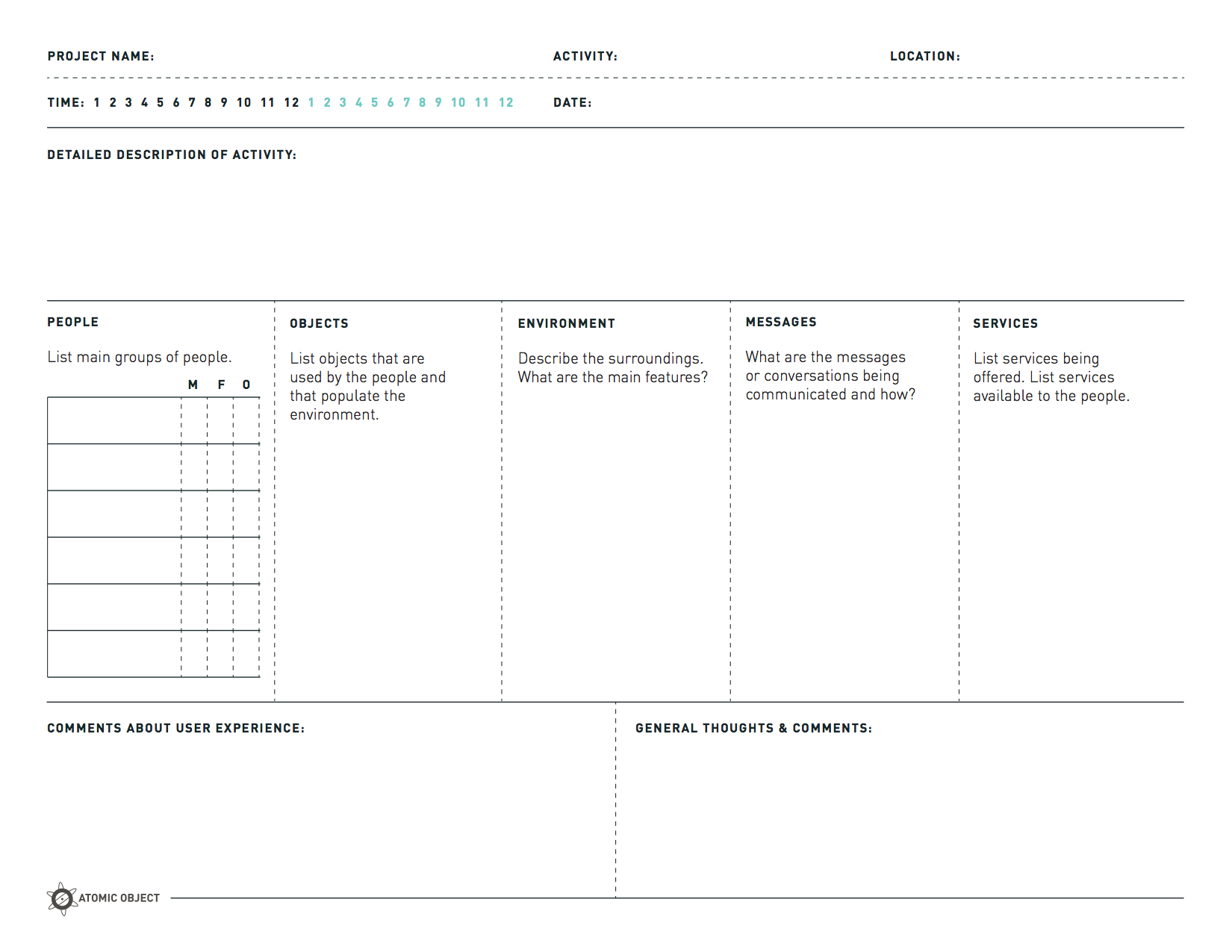

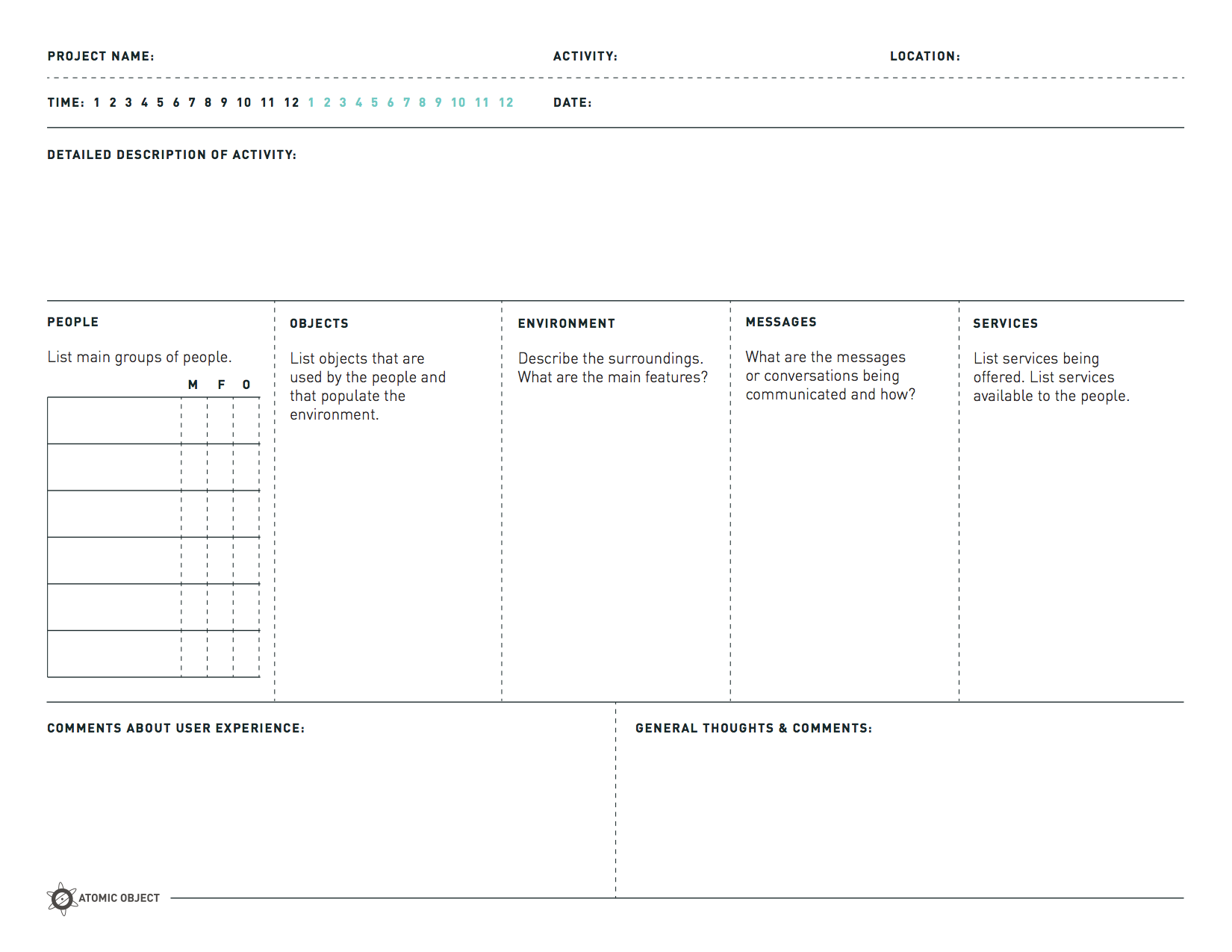

Design Thinking Toolkit, Activity 3 – POEMS

Article summary

1. identify your subjects & location, 2. prep & understand your worksheet.

- Atomic's Design Thinking Toolkit

Welcome to our series on Design Thinking methods and activities . You’ll find a full list of posts in this series at the end of the page.

POEMS stands for People, Objects, Environments, Messages, and Services. This exercise provides a simple framework for quick and surprisingly deep user observation.

We do user observation to understand the people who will be using the software we’re about to create. We want to study them in their current state—who they are, what their environment is like, how they do their job, how they feel about their current process and why, etc.

Whenever possible, do this out in the real world Go to where the end users are trying to accomplish whatever it is that you want to help them do better. Spend at least an hour with each person, and try to observe several.

Begin by creating your template (or download this POEMS Template we made.) There should be five columns, one for each word represented in the acronym. Here is a breakdown of the information you’ll track for each section:

- People – The demographics, roles, behavioral traits, and quantity of people in the environment

- Objects – The items the people are interacting with, including furniture, devices, machines, appliances, tools, etc.

- Environments – Observations about the architecture, lighting, furniture, temperature, atmosphere, etc.

- Messages – The tone of the language or commonly used phrases in tag lines, social/professional interactions, and/or environmental messages

- Services – All services, apps, tools, and frameworks used

Make sure you leave a place to mark your name, the date, time, and location. It’s also good to leave a space open for miscellaneous notes. Here’s what ours looks like:

Begin the exercise by breaking off on your own or with your small team. Sit quietly and observe your surroundings. Mark quick notes in each of the categories based on your findings.

Either review your notes privately or with a group by going through each category one-by-one and sharing. Track each observation on a sticky note and group like observations together.

That ends today’s lesson. Check back soon for new lessons, and leave me a comment below if you’ve given POEMS a try.

Class dismissed!

Atomic’s Design Thinking Toolkit

- What Is Design Thinking?

- Your Design Thinking Supply List

- Activity 1 – The Love/Breakup Letter

- Activity 2 – Story Mapping

- Activity 3 – P.O.E.M.S.

- Activity 4 – Start Your Day

- Activity 5 – Remember the Future

- Activity 6 – Card Sorting

- Activity 7 – Competitors/Complementors Map

- Activity 8 – Difficulty & Importance Matrix

- Activity 9 – Rose, Bud, Thorn

- Activity 10 – Affinity Mapping

- Activity 11 – Speed Boat

- Activity 12 – Visualize The Vote

- Activity 13 – Hopes & Fears

- Activity 14 – I Like, I Wish, What If

- Activity 15 – How to Make Toast

- Activity 16 – How Might We…?

- Activity 17 – Alter Egos

- Activity 18 – What’s On Your Radar?

- Activity 19 – The Perfect Morning

- Activity 20 – 2×3

- Activity 21 – How Can I Help…?

- Activity 22 – Cover Story

- Activity 23 – Crazy 8s

- Activity 24 – Abstraction Ladder

- Activity 25 – Empathy Map

- Activity 26 – Worse Possible Idea

- Activity 27 – Pre-Project Survey

- Activity 28 – The Powers of Ten

- Activity 29 – SCAMPER

- Activity 30 – Design Studio

Related Posts

Can design thinking workshops benefit from competition, lead with “why”: a storytelling shortcut for ideas and products, how to animate on scroll in figma: part 1, keep up with our latest posts..

We’ll send our latest tips, learnings, and case studies from the Atomic braintrust on a monthly basis.

Hi Kimberly! Is there any author writing about the POEMS design method? I have searched all around internet, do you think it is just a practical non-theoretical method? Thanks a lot for your help :)

Hi Cedrela,

Thanks for the great question. I was first introduced to POEMS by the book “101 Design Methods: A Structured Approach for Driving Innovation in Your Organization” by Vijay Kumar. The activity can be found on page 105.

I highly recommend the book especially if you’re interested in learning new research methods. It will give you many, many activities to add to your designer toolbox.

Comments are closed.

Tell Us About Your Project

We’d love to talk with you about your next great software project. Fill out this form and we’ll get back to you within two business days.

A Case Study on Netflix’s Marketing Strategies & Tactics

As the spread of COVID-19 has affected most industries and economies worldwide, people have been forced to stay contained at home to prevent the spread of coronavirus. People have also been bored to death as they have nothing to do.

In this locked-up scenario, your best partner could be your Netflix account which contains thousands of interesting movies, series, and shows. We were discussing which brand to take up for this week’s case study, and then one of our team members got an idea, let’s take the famous OTT platform Netflix which has managed to entertain a large population in no time.

Today, we are going to discuss the story of a platform that is providing us streaming services, or as we call it video-on-demand available on various platforms- personal computers, iPods, or smartphones. Netflix cut through the competitive clutter and reached out to its targeted audience by curating some interesting brand communication strategies over the years.

Let’s get into the success story of Netflix’s Journey.

Netflix was founded on August 29, 1997, in Scotts Valley, California when founders Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings came up with the idea of starting the service of offering online movie rentals. The company began its operations of rental stores with only 30 employees and 925 titles available, which was almost the entire catalog of DVDs in print at the time, through the pay-per-rent model with rates and due dates. Rentals were around $4 plus a $2 postage charge. After significant growth, Netflix decided to switch to a subscriber-based model.

In 2000, Netflix introduced a personalized movie recommendation system. In this system, a user-based rating helps to accurately predict choices for Netflix members. By 2005, the number of Netflix subscribers rose to 4.2 million. On October 1, 2006, Netflix offered a $1,000,000 prize to the first developer of a video-recommendation algorithm that could beat its existing algorithm Cinematch, at predicting customer ratings by more than 10%.

By 2007 the company decided to move away from its original core business model of DVDs by introducing video on demand via the internet. As a part of the internet streaming strategy, they decided to stream their content on Xbox 360, Blu-Ray disc players, and TV set-top boxes. The ventures also partnered with these companies to online streaming their content. With the introduction of the services in Canada in 2010, Netflix also made its services available on the range of Apple products, Nintendo Wii, and other internet-connected devices.

In 2013, Netflix won three Primetime Emmy Awards for its series “House of Cards. By 2014, Netflix made itself available in 6 countries in Europe and won 7 creative Emmy Awards for “House of Cards” and “Orange Is the New Black”. With blooming streaming services, Netflix gathered over 50 million members globally. By 2016, Netflix was accessible worldwide, and the company has continued to create more original content while pressing to grow its membership. From this point, Netflix was unstoppable and today it has a worldwide presence in the video-on-demand industry.

Business Model of Netflix

The platform has advanced to streaming technologies that have elevated and improved Netflix’s overall business structure and revenue. The platform gives viewers the ability to stream and watch a variety of TV shows, movies, and documentaries through its software applications. Since Netflix converted to a streaming platform, it is the world’s seventh-largest Internet company by revenue.

Now, let’s have a look at the business model of Netflix. 1. Netflix’s Key Partners:

- Netflix has built more than 35+ partners across the world. They have partnered with different types of genres for subscribers to select from and enjoy watching.

- Built alliances with Smart TV companies like LG, Sony, Samsung, Xiaomi, and other players in the market.

- Built alliances with Apple, Android, and Microsoft platforms for the purpose of converting business leads from mail-in-system to streaming.

- Built alliances with telecom networks like Airtel, Reliance Jio, and Vodafone.

2. Netflix’s Value Proposition: Netflix aims to provide the best customer experience by deploying valuable propositions. Here is how the online streaming brand strives to do so:

- With a 24*7 streaming service, users can enjoy shows and movies in high-definition quality from anywhere whether they are at home or traveling.

- Users get access to thousands of movies and tv shows and Netflix Original movies or shows.

- New signups can avail of a 30-day free trial and have the option of canceling their subscriptions anytime.

- Receive algorithmic recommendations for new items to watch.

- At Netflix, users have the flexibility to either turn on notifications and suggestions or keep them switched off.

- Netflix’s “user profiles” give leverage for users to personalize their user accounts and preferences. The User profiles allow the “admin-user” to modify, allow or ever restrict certain users.

- Sharing account options is one of the rarest features a movie platform can provide. Sharing accounts feature on Netflix allows spouses, friends, or even groups to share an account with specific filters and preferences already set.

3. Netflix’s Key Activities

- Maintain and continue to expand its platforms on the website, mobile apps

- Curate, develop and acquire licenses for Netflix’s original content and expand its video library.

- Ensure high-quality user recommendations to retain the customer base

- Develop and maintain partnerships with studios, content production houses, and movie production houses.

- Operate according to censorship laws. Netflix always promotes and operates within the boundaries of censorship.

4. Netflix’s Customer Relationships: Netflix has designed a customer-friendly platform that offers:

- Self-Setup: Netflix platform was originally designed to ensure that it is simple and easy to use. Developers of the website ensured to associate elements and themes that serve, promote friendliness, and provide self-setup.

- Unbelievable Customer Experience: Customers can solve their queries by reaching the Netflix team through the website portal, emailing inquiries, and directly reaching the representative on call or live chat.

- Social Media Channels: Netflix also engages its audience through social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. It advertises and offers deals to gain high attraction customers and enhance its customer base.

- Netflix Gift Cards: Netflix offers its customers special promotional discounts and other gift cards as a part of their subscription plan.

Netflix’s Revenue Model

Netflix gained major popularity when the platform launched online streaming services. Let’s have a look at how the platform earns.

- Subscription-Based Business Model: Netflix offers monthly subscription fees with three different price options basic, standard, and premium plan. Today, Netflix has over 125 million paid members from over 190 countries and generates $15 billion annually.

- Important partnerships: Built alliances with a wide range of movie producers, filmmakers, writers, and animators to receive content and legally broadcast the contents required by aligning licenses.

- Internet Service Provider: One of the most influential tactics implemented was its ability to build alliances with a wide range of movie producers, filmmakers, writers, and animators to receive content and legally broadcast the contents required by aligning licenses.

Netflix was able to establish a well-reputed image worldwide and increased its customer base day by day. When it comes to giving competition, the brand has devised various digital marketing strategies and has gained wide popularity on digital media platforms. With the help of the best digital marketing services, they have kindled the excitement and craze in the people to travel and host.

Digital Marketing Model of Netflix

In less than 4 years, Netflix has gathered a major share of the Indian market. Today a majority of households in India subscribe to Netflix, and that number is expected to rise this year and further in the years to come. The product is designed so well, that you remain engrossed in the content they deliver. They adopted top digital marketing strategies. Consult the best brand activation agencies. Further, let’s talk about a few of the digital marketing principles that Netflix has successfully implemented to gather customers.

1. Personalised Content Marketing: People love using Netflix because they get a broad range of things to watch. Netflix’s library of TV shows and movies from all over the world is there for consumers to choose from at any time.

The reason that Netflix won the personalization game is that its advanced algorithm continues to rearrange the programs overtime on the basis of your viewing history. Hire some of the best performance marketing agencies for personalized content.

2. Website Development: Netflix has designed its website with a user-friendly interface that allows customers to rate TV shows and movies, which then goes through Netflix’s algorithm to recommend more content they might enjoy. With the onsite optimization for the website, they have optimized each and every page for enhanced customer experience.

To easily get in the minds of customers, they have optimized their website for content by title, by an actor’s name, or even by a director’s name. By leveraging the best website development services , they added a host of personalization features to their website with clean looks no matter which platform you are using.

3. Email Marketing: Netflix tapped on email marketing techniques as a part of its digital marketing strategy and as a key component of customer onboarding and nurturing. New Netflix customers receive a series of emails that make content recommendations and encourage new users to explore the platform. Netflix marketers invest hours in building creative email marketing campaigns designed to engage and delight recipients. With the help of the best email marketing services , they continue to enhance the experience of the customers

4. Search Engine Optimization: Netflix makes use of search engine optimization services for the sake of improving organic research and establishing its brand presence. The brand aimed at the best search engine optimization services to drive traffic organically and adopted both on-page and off-page SEO strategies. They optimized their content with potential keywords that show up high in search results. They also tapped the strategy of International SEO to gain organic leads from the worldwide stage.

5. Social Media Optimization: Today, social media platforms have become an integral part of digital marketing strategy. If you want to connect with your audience in real time, then it is the best platform to establish your brand image. As social media plays a vital role in the lives of people, Netflix decided to leverage the best social media optimization services that made them earn billions. They made use of the following platforms:

Through creative social media optimization strategies, Netflix has garnered more than 61 million Facebook followers. In just one year, the brand added 11 million followers to its account. Netflix posts nearly 90% of videos and the rests images. Videos featured on Netflix’s

Facebook pages are typically clips from interviews with the actors from the upcoming movies, clips from the upcoming movies and TV shows, offering audiences a sneak peek into what’s in store for them. Besides videos, the OTT platforms share images, GIFs, funny memes, and simple text posts featuring questions about current movies and TV shows.