Home — Essay Samples — Education — Assessment — The Purpose of Assessment and Its Methods

The Purpose of Assessment and Its Methods

- Categories: Assessment

About this sample

Words: 2607 |

14 min read

Published: Feb 13, 2024

Words: 2607 | Pages: 6 | 14 min read

- Gravells, A (2008) Preparing to teach in the LLS

- Ministry of Education (2014) Purpose of Assessment [Online] Available at: http://assessment.tki.org.nz/Assessment-in-the-classroom/Assessment-for-learning-in-principle/Purposes-of-assessment Accessed on 20/03/14

- Rust. C (2005) Developing a variety of assessment methods page 150 Mansfield: Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education Sellors.

- A (2014) Different forms of formative assessment in lesson plans [Online] Available at: http://everydaylife.globalpost.com/different-forms-formative-assessment-lesson-plans-34048.html Accessed on 19/03/14

- Tummons. J (2007) Becoming a professional tutor in the lifelong learning sector Chapter 3 UK: Learning Matters Ltd The University of Texas at Austin (2013) Methods of Assessment [Online] Available at: https://ctl.utexas.edu/assessment/methods Accessed on 19/03/14

- University of Exeter (2005) Principles of Assessment [Online] Available at: https://as.exeter.ac.uk/support/staffdevelopment/aspectsofacademicpractice/assessmentandfeedback/principlesofassessment/typesofassessment-definitions/ Accessed on 22/03/14

- Willis. J (2007) The Neuroscience of Joyful Education Volume 64 UK: Educational Leadership Weaver. B (2014) Formal vs. Informal Assessments [Online] Available at: http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/formal-versus-informal-assessments Accessed on 20/03/14

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 994 words

6 pages / 2696 words

1 pages / 412 words

1 pages / 430 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Assessment

In an ever-evolving digital landscape, the importance of vulnerability assessments cannot be overstated. As organizations increasingly rely on technology to store sensitive information and conduct business operations, the [...]

The learning plan described in this paper is to have students debate a topic related to the Civil War. The debate topic is “Was the Emancipation Proclamation enacted for moral reasons or political reasons?” The main concept of [...]

Assessment is an essential component of the educational process, as it allows educators to measure students' understanding and skill development. This essay aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of WGU Assessment Task 1, [...]

Family assessment and intervention models are crucial tools in the field of social work and psychology, providing a framework for understanding and addressing complex family dynamics. By identifying strengths and challenges [...]

Education is very essential for the betterment of everyone’s life and so everyone should know the importance of education in our life. It enables us and prepares us in every portion of our life. Educated people can easily [...]

This study focused on the relationship that exists amongst the fields of education and economic growth in Pakistan in 1980- 2014 periods. As an equivalent result with the literature studies, the existence of a positive and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Assessing student writing, what does it mean to assess writing.

- Suggestions for Assessing Writing

Means of Responding

Rubrics: tools for response and assessment, constructing a rubric.

Assessment is the gathering of information about student learning. It can be used for formative purposes−−to adjust instruction−−or summative purposes: to render a judgment about the quality of student work. It is a key instructional activity, and teachers engage in it every day in a variety of informal and formal ways.

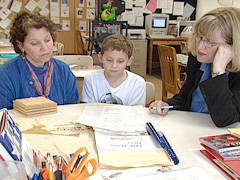

Assessment of student writing is a process. Assessment of student writing and performance in the class should occur at many different stages throughout the course and could come in many different forms. At various points in the assessment process, teachers usually take on different roles such as motivator, collaborator, critic, evaluator, etc., (see Brooke Horvath for more on these roles) and give different types of response.

One of the major purposes of writing assessment is to provide feedback to students. We know that feedback is crucial to writing development. The 2004 Harvard Study of Writing concluded, "Feedback emerged as the hero and the anti-hero of our study−powerful enough to convince students that they could or couldn't do the work in a given field, to push them toward or away from selecting their majors, and contributed, more than any other single factor, to students' sense of academic belonging or alienation" (http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~expos/index.cgi?section=study).

Source: Horvath, Brooke K. "The Components of Written Response: A Practical Synthesis of Current Views." Rhetoric Review 2 (January 1985): 136−56. Rpt. in C Corbett, Edward P. J., Nancy Myers, and Gary Tate. The Writing Teacher's Sourcebook . 4th ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000.

Suggestions for Assessing Student Writing

Be sure to know what you want students to be able to do and why. Good assessment practices start with a pedagogically sound assignment description and learning goals for the writing task at hand. The type of feedback given on any task should depend on the learning goals you have for students and the purpose of the assignment. Think early on about why you want students to complete a given writing project (see guide to writing strong assignments page). What do you want them to know? What do you want students to be able to do? Why? How will you know when they have reached these goals? What methods of assessment will allow you to see that students have accomplished these goals (portfolio assessment assigning multiple drafts, rubric, etc)? What will distinguish the strongest projects from the weakest?

Begin designing writing assignments with your learning goals and methods of assessment in mind.

Plan and implement activities that support students in meeting the learning goals. How will you support students in meeting these goals? What writing activities will you allow time for? How can you help students meet these learning goals?

Begin giving feedback early in the writing process. Give multiple types of feedback early in the writing process. For example, talking with students about ideas, write written responses on drafts, have students respond to their peers' drafts in process, etc. These are all ways for students to receive feedback while they are still in the process of revising.

Structure opportunities for feedback at various points in the writing process. Students should also have opportunities to receive feedback on their writing at various stages in the writing process. This does not mean that teachers need to respond to every draft of a writing project. Structuring time for peer response and group workshops can be a very effective way for students to receive feedback from other writers in the class and for them to begin to learn to revise and edit their own writing.

Be open with students about your expectations and the purposes of the assignments. Students respond better to writing projects when they understand why the project is important and what they can learn through the process of completing it. Be explicit about your goals for them as writers and why those goals are important to their learning. Additionally, talk with students about methods of assessment. Some teachers have students help collaboratively design rubrics for the grading of writing. Whatever methods of assessment you choose, be sure to let students in on how they will be evaluated.

Do not burden students with excessive feedback. Our instinct as teachers, especially when we are really interested in students´ writing is to offer as many comments and suggestions as we can. However, providing too much feedback can leave students feeling daunted and uncertain where to start in terms of revision. Try to choose one or two things to focus on when responding to a draft. Offer students concrete possibilities or strategies for revision.

Allow students to maintain control over their paper. Instead of acting as an editor, suggest options or open-ended alternatives the student can choose for their revision path. Help students learn to assess their own writing and the advice they get about it.

Purposes of Responding We provide different kinds of response at different moments. But we might also fall into a kind of "default" mode, working to get through the papers without making a conscious choice about how and why we want to respond to a given assignment. So it might be helpful to identify the two major kinds of response we provide:

- Formative Response: response that aims primarily to help students develop their writing. Might focus on confidence-building, on engaging the student in a conversation about her ideas or writing choices so as to help student to see herself as a successful and promising writer. Might focus on helping student develop a particular writing project, from one draft to next. Or, might suggest to student some general skills she could focus on developing over the course of a semester.

- Evaluative Response: response that focuses on evaluation of how well a student has done. Might be related to a grade. Might be used primarily on a final product or portfolio. Tends to emphasize whether or not student has met the criteria operative for specific assignment and to explain that judgment.

We respond to many kinds of writing and at different stages in the process, from reading responses, to exercises, to generation or brainstorming, to drafts, to source critiques, to final drafts. It is also helpful to think of the various forms that response can take.

- Conferencing: verbal, interactive response. This might happen in class or during scheduled sessions in offices. Conferencing can be more dynamic: we can ask students questions about their work, modeling a process of reflecting on and revising a piece of writing. Students can also ask us questions and receive immediate feedback. Conference is typically a formative response mechanism, but might also serve usefully to convey evaluative response.

- Written Comments on Drafts

- Local: when we focus on "local" moments in a piece of writing, we are calling attention to specifics in the paper. Perhaps certain patterns of grammar or moments where the essay takes a sudden, unexpected turn. We might also use local comments to emphasize a powerful turn of phrase, or a compelling and well-developed moment in a piece. Local commenting tends to happen in the margins, to call attention to specific moments in the piece by highlighting them and explaining their significance. We tend to use local commenting more often on drafts and when doing formative response.

- Global: when we focus more on the overall piece of writing and less on the specific moments in and of themselves. Global comments tend to come at the end of a piece, in narrative-form response. We might use these to step back and tell the writer what we learned overall, or to comment on a pieces' general organizational structure or focus. We tend to use these for evaluative response and often, deliberately or not, as a means of justifying the grade we assigned.

- Rubrics: charts or grids on which we identify the central requirements or goals of a specific project. Then, we evaluate whether or not, and how effectively, students met those criteria. These can be written with students as a means of helping them see and articulate the goals a given project.

Rubrics are tools teachers and students use to evaluate and classify writing, whether individual pieces or portfolios. They identify and articulate what is being evaluated in the writing, and offer "descriptors" to classify writing into certain categories (1-5, for instance, or A-F). Narrative rubrics and chart rubrics are the two most common forms. Here is an example of each, using the same classification descriptors:

Example: Narrative Rubric for Inquiring into Family & Community History

An "A" project clearly and compellingly demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows strong audience awareness, engaging readers throughout. The form and structure are appropriate for the purpose(s) and audience(s) of the piece. The final product is virtually error-free. The piece seamlessly weaves in several other voices, drawn from appropriate archival, secondary, and primary research. Drafts - at least two beyond the initial draft - show extensive, effective revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter demonstrate thoughtful reflection and growing awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "B" project clearly and compellingly demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows strong audience awareness, and usually engages readers. The form and structure are appropriate for the audience(s) and purpose(s) of the piece, though the organization may not be tight in a couple places. The final product includes a few errors, but these do no interfere with readers' comprehension. The piece effectively, if not always seamlessly, weaves several other voices, drawn from appropriate archival, secondary, and primary research. One area of research may not be as strong as the other two. Drafts - at least two beyond the initial drafts - show extensive, effective revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter demonstrate thoughtful reflection and growing awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "C" project demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows audience awareness, sometimes engaging readers. The form and structure are appropriate for the audience(s) and purpose(s), but the organization breaks down at times. The piece includes several, apparent errors, which at times compromises the clarity of the piece. The piece incorporates other voices, drawn from at least two kinds of research, but in a generally forced or awkward way. There is unevenness in the quality and appropriateness of the research. Drafts - at least one beyond the initial draft - show some evidence of revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter show some reflection and growth in awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "D" project discusses a public event and a family/community, but the connections may not be clear. It shows little audience awareness. The form and structure is poorly chosen or poorly executed. The piece includes many errors, which regularly compromise the comprehensibility of the piece. There is an attempt to incorporate other voices, but this is done awkwardly or is drawn from incomplete or inappropriate research. There is little evidence of revision. Writer's notes and learning letter are missing or show little reflection or growth.

An "F" project is not responsive to the prompt. It shows little or no audience awareness. The purpose is unclear and the form and structure are poorly chosen and poorly executed. The piece includes many errors, compromising the clarity of the piece throughout. There is little or no evidence of research. There is little or no evidence of revision. Writer's notes and learning letter are missing or show no reflection or growth.

Chart Rubric for Community/Family History Inquiry Project

All good rubrics begin (and end) with solid criteria. We always start working on rubrics by generating a list - by ourselves or with students - of what we value for a particular project or portfolio. We generally list far more items than we could use in a single rubric. Then, we narrow this list down to the most important items - between 5 and 7, ideally. We do not usually rank these items in importance, but it is certainly possible to create a hierarchy of criteria on a rubric (usually by listing the most important criteria at the top of the chart or at the beginning of the narrative description).

Once we have our final list of criteria, we begin to imagine how writing would fit into a certain classification category (1-5, A-F, etc.). How would an "A" essay differ from a "B" essay in Organization? How would a "B" story differ from a "C" story in Character Development? The key here is to identify useful descriptors - drawing the line at appropriate places. Sometimes, these gradations will be precise: the difference between handing in 80% and 90% of weekly writing, for instance. Other times, they will be vague: the difference between "effective revisions" and "mostly effective revisions", for instance. While it is important to be as precise as possible, it is also important to remember that rubric writing (especially in writing classrooms) is more art than science, and will never - and nor should it - stand in for algorithms. When we find ourselves getting caught up in minute gradations, we tend to be overlegislating students´- writing and losing sight of the purpose of the exercise: to support students' development as writers. At the moment when rubric-writing thwarts rather than supports students' writing, we should discontinue the practice. Until then, many students will find rubrics helpful -- and sometimes even motivating.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.6: What are the benefits of essay tests?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 87692

- Jennfer Kidd, Jamie Kaufman, Peter Baker, Patrick O'Shea, Dwight Allen, & Old Dominion U students

- Old Dominion University

Learning Objectives

- Understand the benefits of essay questions for both Students and Teachers

- Identify when essays are useful

Introduction

Essays, along with multiple choice, are a very common method of assessment. Essays offer a means completely different than that of multiple choice. When thinking of a means of assessment, the essay along with multiple choice are the two that most come to mind (Schouller).The essay lends itself to specific subjects; for example, a math test would not have an essay question. The essay is more common in the arts, humanities and the social sciences(Scouller). On occasion an essay can be used used in both physical and natural sciences as well(Scouller). As a future history teacher, I will find that essays will be an essential part of my teaching structure.

The Benefits for Students

By utilizing essays as a mean of assessments, teachers are able to better survey what the student has learned. Multiple choice questions, by their very design, can be worked around. The student can guess, and has decent chance of getting the question right, even if they did not know the answer. This blind guessing does not benefit the student at all. In addition, some multiple choices can deceive the student(Moore). Short answers, and their big brother the essay, work in an entirely different way. Essays remove this factor. in a addition, rather than simply recognize the subject matter, the student must recall the material covered. This challenges the student more, and by forcing the student to remember the information needed, causes the student to retain it better. This in turn reinforces understanding(Moore). Scouller adds to this observation, determining that essay assessment "encourages students' development of higher order intellectual skills and the employment of deeper learning approaches; and secondly, allows students to demonstrate their development."

"Essay questions provide more opportunity to communicate ideas. Whereas multiple choice limits the options, an essay allows the student express ideas that would otherwise not be communicated." (Moore)

The Benefits for Teachers

The matter of preparation must also be considered when comparing multiple choice and essays. For multiple choice questions, the instructor must choose several questions that cover the material covered. After doing so, then the teacher has to come up with multiple possible answers. This is much more difficult than one might assume. With the essay question, the teacher will still need to be creative. However, the teacher only has to come up with a topic, and what the student is expected to cover. This saves the teacher time. When grading, the teacher knows what he or she is looking for in the paper, so the time spent reading is not necessarily more. The teacher also benefits from a better understanding of what they are teaching. The process of selecting a good essay question requires some critical thought of its own, which reflects onto the teacher(Moore).

Multiple Choice. True or False. Short Answer. Essay. All are forms of assessment. All have their pros and cons. For some, they are better suited for particular subjects. Others, not so much. Some students may even find essays to be easier. It is vital to understand when it is best to utilize the essay. Obviously for teachers of younger students, essays are not as useful. However, as the age of the student increase, the importance of the essay follows suit. That essays are utilized in essential exams such as the SAT, SOLs and in our case the PRAXIS demonstrates how important essays are. However, what it ultimately comes down to is what the teacher feels what will best assess what has been covered.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

1)What Subject would most benefit from essays?

B: Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

C: Survey of American Literature

2)What is an advantage of essay assessment for the student?

A) They allow for better expression

B) There is little probability for randomness

C) The time taken is less overall

D) A & B

3)What is NOT a benefit of essay assessment for the teacher

A)They help the instructor better understand the subject

B)They remove some the work required for multiple choice

C)The time spent on preparation is less

D) There is no noticeable benefit.

4)Issac is a teacher making up a test. The test will have multiple sections: Short answer, multiple choice, and an essay. What subject does Issac MOST LIKELY teach?

References Cited

1)Moore, S.(2008) Interview with Scott Moore, Professor at Old Dominion University

2)Scouller, K. (1998). The influence of assessment method on students' learning approaches: multiple Choice question examination versus assignment essay. Higher Education 35(4), pp. 453–472

Center for Teaching

Assessing student learning.

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

Assessment is more than grading, assessment plans, methods of student assessment, generative and reflective assessment, teaching guides related to student assessment, references and additional resources.

Student assessment is, arguably, the centerpiece of the teaching and learning process and therefore the subject of much discussion in the scholarship of teaching and learning. Without some method of obtaining and analyzing evidence of student learning, we can never know whether our teaching is making a difference. That is, teaching requires some process through which we can come to know whether students are developing the desired knowledge and skills, and therefore whether our instruction is effective. Learning assessment is like a magnifying glass we hold up to students’ learning to discern whether the teaching and learning process is functioning well or is in need of change.

To provide an overview of learning assessment, this teaching guide has several goals, 1) to define student learning assessment and why it is important, 2) to discuss several approaches that may help to guide and refine student assessment, 3) to address various methods of student assessment, including the test and the essay, and 4) to offer several resources for further research. In addition, you may find helfpul this five-part video series on assessment that was part of the Center for Teaching’s Online Course Design Institute.

What is student assessment and why is it Important?

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning” (2001, p. 5). An intentional and thorough assessment of student learning is vital because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction — “Backward Design”— that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggins and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course goals. Assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred (2005, p. 18). Their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, p. 18). [1]

Not only does effective assessment provide us with valuable information to support student growth, but it also enables critically reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, argues that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students (1995). Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the intentional and meaningful development of one’s teaching philosophy and practices. According to Brookfield, referencing higher education faculty, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment” (Brookfield, 1995, p. 17). One important lens through which we may reflect on our teaching is our student evaluations and student learning assessments. This reflection allows educators to determine where their teaching has been effective in meeting learning goals and where it has not, allowing for improvements. Student assessment, then, both develop the rationale for pedagogical choices, and enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching.

The scholarship of teaching and learning discusses two general forms of assessment. The first, summative assessment , is one that is implemented at the end of the course of study, for example via comprehensive final exams or papers. Its primary purpose is to produce an evaluation that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful for communicating final evaluations of student achievement, it does so without providing opportunities for students to reflect on their progress, alter their learning, and demonstrate growth or improvement; nor does it allow instructors to modify their teaching strategies before student learning in a course has concluded (Maki, 2002).

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning at intermediate points before any summative form. Its fundamental purpose is to help students during the learning process by enabling them to reflect on their challenges and growth so they may improve. By analyzing students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies” (Maki, 2002, p. 11). Pat Hutchings refers to as “assessment behind outcomes”: “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, p. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes all manner of coursework with feedback, discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves (Brown and Knight, 1994).

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed below) can either be summative or formative depending on when and how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in Assessing Learners in Higher Education caution against a conflation of the method (e.g., an essay) with the goal (formative or summative): “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback” (1994, p. 17). If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, but he or she does not take the requisite time or effort to provide extensive feedback to students, the assessment effectively functions as a summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions (Brown and Knight, 1994). Indeed, feedback and discussion are critical factors that distinguish between formative and summative assessment; formative assessment is only as good as the feedback that accompanies it.

It is not uncommon to conflate assessment with grading, but this would be a mistake. Student assessment is more than just grading. Assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to students and instructors about learning and teaching, respectively. Grading, on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. (2001) merely involves affixing a number or letter to an assignment, giving students only the most minimal indication of their performance relative to a set of criteria or to their peers: “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest” (Stassen et al., 2001, p. 6). Grades are only the broadest of indicators of achievement or status, and as such do not provide very meaningful information about students’ learning of knowledge or skills, how they have developed, and what may yet improve. Unfortunately, despite the limited information grades provide students about their learning, grades do provide students with significant indicators of their status – their academic rank, their credits towards graduation, their post-graduation opportunities, their eligibility for grants and aid, etc. – which can distract students from the primary goal of assessment: learning. Indeed, shifting the focus of assessment away from grades and towards more meaningful understandings of intellectual growth can encourage students (as well as instructors and institutions) to attend to the primary goal of education.

Barbara Walvoord (2010) argues that assessment is more likely to be successful if there is a clear plan, whether one is assessing learning in a course or in an entire curriculum (see also Gelmon, Holland, and Spring, 2018). Without some intentional and careful plan, assessment can fall prey to unclear goals, vague criteria, limited communication of criteria or feedback, invalid or unreliable assessments, unfairness in student evaluations, or insufficient or even unmeasured learning. There are several steps in this planning process.

- Defining learning goals. An assessment plan usually begins with a clearly articulated set of learning goals.

- Defining assessment methods. Once goals are clear, an instructor must decide on what evidence – assignment(s) – will best reveal whether students are meeting the goals. We discuss several common methods below, but these need not be limited by anything but the learning goals and the teaching context.

- Developing the assessment. The next step would be to formulate clear formats, prompts, and performance criteria that ensure students can prepare effectively and provide valid, reliable evidence of their learning.

- Integrating assessment with other course elements. Then the remainder of the course design process can be completed. In both integrated (Fink 2013) and backward course design models (Wiggins & McTighe 2005), the primary assessment methods, once chosen, become the basis for other smaller reading and skill-building assignments as well as daily learning experiences such as lectures, discussions, and other activities that will prepare students for their best effort in the assessments.

- Communicate about the assessment. Once the course has begun, it is possible and necessary to communicate the assignment and its performance criteria to students. This communication may take many and preferably multiple forms to ensure student clarity and preparation, including assignment overviews in the syllabus, handouts with prompts and assessment criteria, rubrics with learning goals, model assignments (e.g., papers), in-class discussions, and collaborative decision-making about prompts or criteria, among others.

- Administer the assessment. Instructors then can implement the assessment at the appropriate time, collecting evidence of student learning – e.g., receiving papers or administering tests.

- Analyze the results. Analysis of the results can take various forms – from reading essays to computer-assisted test scoring – but always involves comparing student work to the performance criteria and the relevant scholarly research from the field(s).

- Communicate the results. Instructors then compose an assessment complete with areas of strength and improvement, and communicate it to students along with grades (if the assignment is graded), hopefully within a reasonable time frame. This also is the time to determine whether the assessment was valid and reliable, and if not, how to communicate this to students and adjust feedback and grades fairly. For instance, were the test or essay questions confusing, yielding invalid and unreliable assessments of student knowledge.

- Reflect and revise. Once the assessment is complete, instructors and students can develop learning plans for the remainder of the course so as to ensure improvements, and the assignment may be changed for future courses, as necessary.

Let’s see how this might work in practice through an example. An instructor in a Political Science course on American Environmental Policy may have a learning goal (among others) of students understanding the historical precursors of various environmental policies and how these both enabled and constrained the resulting legislation and its impacts on environmental conservation and health. The instructor therefore decides that the course will be organized around a series of short papers that will combine to make a thorough policy report, one that will also be the subject of student presentations and discussions in the last third of the course. Each student will write about an American environmental policy of their choice, with a first paper addressing its historical precursors, a second focused on the process of policy formation, and a third analyzing the extent of its impacts on environmental conservation or health. This will help students to meet the content knowledge goals of the course, in addition to its goals of improving students’ research, writing, and oral presentation skills. The instructor then develops the prompts, guidelines, and performance criteria that will be used to assess student skills, in addition to other course elements to best prepare them for this work – e.g., scaffolded units with quizzes, readings, lectures, debates, and other activities. Once the course has begun, the instructor communicates with the students about the learning goals, the assignments, and the criteria used to assess them, giving them the necessary context (goals, assessment plan) in the syllabus, handouts on the policy papers, rubrics with assessment criteria, model papers (if possible), and discussions with them as they need to prepare. The instructor then collects the papers at the appropriate due dates, assesses their conceptual and writing quality against the criteria and field’s scholarship, and then provides written feedback and grades in a manner that is reasonably prompt and sufficiently thorough for students to make improvements. Then the instructor can make determinations about whether the assessment method was effective and what changes might be necessary.

Assessment can vary widely from informal checks on understanding, to quizzes, to blogs, to essays, and to elaborate performance tasks such as written or audiovisual projects (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Below are a few common methods of assessment identified by Brown and Knight (1994) that are important to consider.

According to Euan S. Henderson, essays make two important contributions to learning and assessment: the development of skills and the cultivation of a learning style (1980). The American Association of Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) also has found that intensive writing is a “high impact” teaching practice likely to help students in their engagement, learning, and academic attainment (Kuh 2008).

Things to Keep in Mind about Essays

- Essays are a common form of writing assignment in courses and can be either a summative or formative form of assessment depending on how the instructor utilizes them.

- Essays encompass a wide array of narrative forms and lengths, from short descriptive essays to long analytical or creative ones. Shorter essays are often best suited to assess student’s understanding of threshold concepts and discrete analytical or writing skills, while longer essays afford assessments of higher order concepts and more complex learning goals, such as rigorous analysis, synthetic writing, problem solving, or creative tasks.

- A common challenge of the essay is that students can use them simply to regurgitate rather than analyze and synthesize information to make arguments. Students need performance criteria and prompts that urge them to go beyond mere memorization and comprehension, but encourage the highest levels of learning on Bloom’s Taxonomy . This may open the possibility for essay assignments that go beyond the common summary or descriptive essay on a given topic, but demand, for example, narrative or persuasive essays or more creative projects.

- Instructors commonly assume that students know how to write essays and can encounter disappointment or frustration when they discover that this is sometimes not the case. For this reason, it is important for instructors to make their expectations clear and be prepared to assist, or provide students to resources that will enhance their writing skills. Faculty may also encourage students to attend writing workshops at university writing centers, such as Vanderbilt University’s Writing Studio .

Exams and time-constrained, individual assessment

Examinations have traditionally been a gold standard of assessment, particularly in post-secondary education. Many educators prefer them because they can be highly effective, they can be standardized, they are easily integrated into disciplines with certification standards, and they are efficient to implement since they can allow for less labor-intensive feedback and grading. They can involve multiple forms of questions, be of varying lengths, and can be used to assess multiple levels of student learning. Like essays they can be summative or formative forms of assessment.

Things to Keep in Mind about Exams

- Exams typically focus on the assessment of students’ knowledge of facts, figures, and other discrete information crucial to a course. While they can involve questioning that demands students to engage in higher order demonstrations of comprehension, problem solving, analysis, synthesis, critique, and even creativity, such exams often require more time to prepare and validate.

- Exam questions can be multiple choice, true/false, or other discrete answer formats, or they can be essay or problem-solving. For more on how to write good multiple choice questions, see this guide .

- Exams can make significant demands on students’ factual knowledge and therefore can have the side-effect of encouraging cramming and surface learning. Further, when exams are offered infrequently, or when they have high stakes by virtue of their heavy weighting in course grade schemes or in student goals, they may accompany violations of academic integrity.

- In the process of designing an exam, instructors should consider the following questions. What are the learning objectives that the exam seeks to evaluate? Have students been adequately prepared to meet exam expectations? What are the skills and abilities that students need to do well on the exam? How will this exam be utilized to enhance the student learning process?

Self-Assessment

The goal of implementing self-assessment in a course is to enable students to develop their own judgment and the capacities for critical meta-cognition – to learn how to learn. In self-assessment students are expected to assess both the processes and products of their learning. While the assessment of the product is often the task of the instructor, implementing student self-assessment in the classroom ensures students evaluate their performance and the process of learning that led to it. Self-assessment thus provides a sense of student ownership of their learning and can lead to greater investment and engagement. It also enables students to develop transferable skills in other areas of learning that involve group projects and teamwork, critical thinking and problem-solving, as well as leadership roles in the teaching and learning process with their peers.

Things to Keep in Mind about Self-Assessment

- Self-assessment is not self-grading. According to Brown and Knight, “Self-assessment involves the use of evaluative processes in which judgement is involved, where self-grading is the marking of one’s own work against a set of criteria and potential outcomes provided by a third person, usually the [instructor]” (1994, p. 52). Self-assessment can involve self-grading, but instructors of record retain the final authority to determine and assign grades.

- To accurately and thoroughly self-assess, students require clear learning goals for the assignment in question, as well as rubrics that clarify different performance criteria and levels of achievement for each. These rubrics may be instructor-designed, or they may be fashioned through a collaborative dialogue with students. Rubrics need not include any grade assignation, but merely descriptive academic standards for different criteria.

- Students may not have the expertise to assess themselves thoroughly, so it is helpful to build students’ capacities for self-evaluation, and it is important that they always be supplemented with faculty assessments.

- Students may initially resist instructor attempts to involve themselves in the assessment process. This is usually due to insecurities or lack of confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate their own work, or possibly because of habituation to more passive roles in the learning process. Brown and Knight note, however, that when students are asked to evaluate their work, frequently student-determined outcomes are very similar to those of instructors, particularly when the criteria and expectations have been made explicit in advance (1994).

- Methods of self-assessment vary widely and can be as unique as the instructor or the course. Common forms of self-assessment involve written or oral reflection on a student’s own work, including portfolio, logs, instructor-student interviews, learner diaries and dialog journals, post-test reflections, and the like.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is a type of collaborative learning technique where students evaluate the work of their peers and, in return, have their own work evaluated as well. This dimension of assessment is significantly grounded in theoretical approaches to active learning and adult learning . Like self-assessment, peer assessment gives learners ownership of learning and focuses on the process of learning as students are able to “share with one another the experiences that they have undertaken” (Brown and Knight, 1994, p. 52). However, it also provides students with other models of performance (e.g., different styles or narrative forms of writing), as well as the opportunity to teach, which can enable greater preparation, reflection, and meta-cognitive organization.

Things to Keep in Mind about Peer Assessment

- Similar to self-assessment, students benefit from clear and specific learning goals and rubrics. Again, these may be instructor-defined or determined through collaborative dialogue.

- Also similar to self-assessment, it is important to not conflate peer assessment and peer grading, since grading authority is retained by the instructor of record.

- While student peer assessments are most often fair and accurate, they sometimes can be subject to bias. In competitive educational contexts, for example when students are graded normatively (“on a curve”), students can be biased or potentially game their peer assessments, giving their fellow students unmerited low evaluations. Conversely, in more cooperative teaching environments or in cases when they are friends with their peers, students may provide overly favorable evaluations. Also, other biases associated with identity (e.g., race, gender, or class) and personality differences can shape student assessments in unfair ways. Therefore, it is important for instructors to encourage fairness, to establish processes based on clear evidence and identifiable criteria, and to provide instructor assessments as accompaniments or correctives to peer evaluations.

- Students may not have the disciplinary expertise or assessment experience of the instructor, and therefore can issue unsophisticated judgments of their peers. Therefore, to avoid unfairness, inaccuracy, and limited comments, formative peer assessments may need to be supplemented with instructor feedback.

As Brown and Knight assert, utilizing multiple methods of assessment, including more than one assessor when possible, improves the reliability of the assessment data. It also ensures that students with diverse aptitudes and abilities can be assessed accurately and have equal opportunities to excel. However, a primary challenge to the multiple methods approach is how to weigh the scores produced by multiple methods of assessment. When particular methods produce higher range of marks than others, instructors can potentially misinterpret and mis-evaluate student learning. Ultimately, they caution that, when multiple methods produce different messages about the same student, instructors should be mindful that the methods are likely assessing different forms of achievement (Brown and Knight, 1994).

These are only a few of the many forms of assessment that one might use to evaluate and enhance student learning (see also ideas present in Brown and Knight, 1994). To this list of assessment forms and methods we may add many more that encourage students to produce anything from research papers to films, theatrical productions to travel logs, op-eds to photo essays, manifestos to short stories. The limits of what may be assigned as a form of assessment is as varied as the subjects and skills we seek to empower in our students. Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching has an ever-expanding array of guides on creative models of assessment that are present below, so please visit them to learn more about other assessment innovations and subjects.

Whatever plan and method you use, assessment often begins with an intentional clarification of the values that drive it. While many in higher education may argue that values do not have a role in assessment, we contend that values (for example, rigor) always motivate and shape even the most objective of learning assessments. Therefore, as in other aspects of assessment planning, it is helpful to be intentional and critically reflective about what values animate your teaching and the learning assessments it requires. There are many values that may direct learning assessment, but common ones include rigor, generativity, practicability, co-creativity, and full participation (Bandy et al., 2018). What do these characteristics mean in practice?

Rigor. In the context of learning assessment, rigor means aligning our methods with the goals we have for students, principles of validity and reliability, ethics of fairness and doing no harm, critical examinations of the meaning we make from the results, and good faith efforts to improve teaching and learning. In short, rigor suggests understanding learning assessment as we would any other form of intentional, thoroughgoing, critical, and ethical inquiry.

Generativity. Learning assessments may be most effective when they create conditions for the emergence of new knowledge and practice, including student learning and skill development, as well as instructor pedagogy and teaching methods. Generativity opens up rather than closes down possibilities for discovery, reflection, growth, and transformation.

Practicability. Practicability recommends that learning assessment be grounded in the realities of the world as it is, fitting within the boundaries of both instructor’s and students’ time and labor. While this may, at times, advise a method of learning assessment that seems to conflict with the other values, we believe that assessment fails to be rigorous, generative, participatory, or co-creative if it is not feasible and manageable for instructors and students.

Full Participation. Assessments should be equally accessible to, and encouraging of, learning for all students, empowering all to thrive regardless of identity or background. This requires multiple and varied methods of assessment that are inclusive of diverse identities – racial, ethnic, national, linguistic, gendered, sexual, class, etcetera – and their varied perspectives, skills, and cultures of learning.

Co-creation. As alluded to above regarding self- and peer-assessment, co-creative approaches empower students to become subjects of, not just objects of, learning assessment. That is, learning assessments may be more effective and generative when assessment is done with, not just for or to, students. This is consistent with feminist, social, and community engagement pedagogies, in which values of co-creation encourage us to critically interrogate and break down hierarchies between knowledge producers (traditionally, instructors) and consumers (traditionally, students) (e.g., Saltmarsh, Hartley, & Clayton, 2009, p. 10; Weimer, 2013). In co-creative approaches, students’ involvement enhances the meaningfulness, engagement, motivation, and meta-cognitive reflection of assessments, yielding greater learning (Bass & Elmendorf, 2019). The principle of students being co-creators of their own education is what motivates the course design and professional development work Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching has organized around the Students as Producers theme.

Below is a list of other CFT teaching guides that supplement this one and may be of assistance as you consider all of the factors that shape your assessment plan.

- Active Learning

- An Introduction to Lecturing

- Beyond the Essay: Making Student Thinking Visible in the Humanities

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Classroom Response Systems

- How People Learn

- Service-Learning and Community Engagement

- Syllabus Construction

- Teaching with Blogs

- Test-Enhanced Learning

- Assessing Student Learning (a five-part video series for the CFT’s Online Course Design Institute)

Angelo, Thomas A., and K. Patricia Cross. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers . 2 nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. Print.

Bandy, Joe, Mary Price, Patti Clayton, Julia Metzker, Georgia Nigro, Sarah Stanlick, Stephani Etheridge Woodson, Anna Bartel, & Sylvia Gale. Democratically engaged assessment: Reimagining the purposes and practices of assessment in community engagement . Davis, CA: Imagining America, 2018. Web.

Bass, Randy and Heidi Elmendorf. 2019. “ Designing for Difficulty: Social Pedagogies as a Framework for Course Design .” Social Pedagogies: Teagle Foundation White Paper. Georgetown University, 2019. Web.

Brookfield, Stephen D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. Print

Brown, Sally, and Peter Knight. Assessing Learners in Higher Education . 1 edition. London ;Philadelphia: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Cameron, Jeanne et al. “Assessment as Critical Praxis: A Community College Experience.” Teaching Sociology 30.4 (2002): 414–429. JSTOR . Web.

Fink, L. Dee. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Gibbs, Graham and Claire Simpson. “Conditions under which Assessment Supports Student Learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (2004): 3-31. Print.

Henderson, Euan S. “The Essay in Continuous Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 5.2 (1980): 197–203. Taylor and Francis+NEJM . Web.

Gelmon, Sherril B., Barbara Holland, and Amy Spring. Assessing Service-Learning and Civic Engagement: Principles and Techniques. Second Edition . Stylus, 2018. Print.

Kuh, George. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter , American Association of Colleges & Universities, 2008. Web.

Maki, Peggy L. “Developing an Assessment Plan to Learn about Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 28.1 (2002): 8–13. ScienceDirect . Web. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. Print.

Sharkey, Stephen, and William S. Johnson. Assessing Undergraduate Learning in Sociology . ASA Teaching Resource Center, 1992. Print.

Walvoord, Barbara. Assessment Clear and Simple: A Practical Guide for Institutions, Departments, and General Education. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print.

Weimer, Maryellen. Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding By Design . 2nd Expanded edition. Alexandria,

VA: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2005. Print.

[1] For more on Wiggins and McTighe’s “Backward Design” model, see our teaching guide here .

Photo credit

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Jun 29, 2023

Evaluation Essay Examples: Master the Art of Critical Assessment with Examples and Techniques

Want to turn good evaluation essays into great ones? We've got you covered with the guidance and insights you need. Join us as we delve into the art of critical assessment!

An evaluation paper's main purpose is to assess entities like a book, movie, restaurant, or product and provide constructive criticism. This writing style can be approached with serious objectivity or with humor and sarcasm. Reviewing is a common form of academic writing that serves to assess something and is often used in various fields as a research method. For example, research papers might include literature reviews or case studies, using evaluation as an analytical tool.

Evaluation reports can also take the form of analyses and critiques. A critique of a scientific study would look at its methodology and findings, while an analysis of a novel would focus on its themes, characters, and writing style. It's essential to consider your audience and your purpose before starting an evaluation document.

Evaluation papers are a versatile and meaningful writing form that can both educate and entertain audiences. Regardless of whether the tone is serious or humorous, objective or subjective, a well-written review can engage and educate.

To understand everything about evaluation essays, from their definition and purpose to potential topics and writing tips, read on.

What are Evaluation Essays?

An evaluation essay allows the author to make a claim and offer a verdict on a topic. This essay type can be used to identify the best option among several alternatives, or to analyze a specific method, product, or situation. It is a common academic task across all levels. Evaluation essays come in different forms, from online product reviews to business cases prepared by management professionals.

In contrast to a descriptive essay, an evaluation essay aims to express the author's judgment. However, this essay type is defined by an objective tone. The author's judgment should be based on careful examination of the available evidence. This differs from a persuasive essay, which seeks to convince the reader to adopt the author's point of view. An evaluation essay starts with the facts and forms conclusions based on these facts.

How to Write an Evaluation Essay?

To write an effective evaluation essay, follow these essential writing tips:

1. Select a Topic

The essay topic is crucial. It should be both educational and interesting, providing enough information to fill an entire essay.

2. Draft an Evaluation Essay Outline

Professional writers always advise creating an evaluation essay outline before writing the essay itself. This aids in writing and ensures content coherence. An outline is also easier to modify than a complete essay. Think about what should be included and excluded when designing your essay's outline. However, skipping this step and diving straight into the essay writing can create extra work later, as it can mean editing and revising the entire piece.

The general components of an evaluation essay outline include:

a. Introduction

The introduction is vital as it forms the readers' first impression. It should engage readers and arouse their interest in the topic. The aspects to consider when writing the introduction are as follows:

Begin with a compelling hook statement to capture the reader's interest.

Provide background information on the topic for better understanding.

Formulate a clear and concise thesis statement, outlining the main objective of the evaluation.

b. Body Section

The body of the essay consists of three paragraphs. Each paragraph should deliver several related ideas and flow seamlessly from start to finish. The key ideas to cover in the body paragraphs include:

Start with a sentence that presents your view on the topic.

Provide arguments that support the topic sentence and your stance.

Present a well-rounded argument to show impartiality.

Compare the subject to a different topic to showcase its strengths and weaknesses.

Present the evaluation from various angles, applying both approving and critical thinking.

c. Conclusion

This is your final chance to convince the reader of your viewpoint. The conclusion should summarize the essay and present the overall evaluation and final assessment. When composing an evaluation essay's conclusion, keep the following points in mind:

Restate your main points and arguments from the essay body.

Present evidence to support your thesis.

Conclude your argument convincingly, ultimately persuading the reader of your assessment.

3. Review, Edit, and Proofread

The final steps after writing the essay are editing and proofreading. Carefully reading your essay will help identify and correct any unintentional errors. If necessary, review your draft multiple times to ensure no mistakes are present.

Structure of an Evaluation Essay

An evaluation essay, like any good piece of writing, follows a basic structure: an introduction, body, and conclusion. But to make your evaluation essay standout, it's crucial to distinctly outline every segment and explain the process that led you to your final verdict. Here's how to do it:

Introduction

Start strong. Your introduction needs to captivate your readers and compel them to read further. To accomplish this, begin with a clear declaration of purpose. Provide a brief background of the work being evaluated to showcase your expertise on the topic.

Next, rephrase the essay prompt, stating the purpose of your piece. For example, "This essay will critically assess X, utilizing Y standards, and analyzing its pros and cons." This presents your comprehension of the task at hand.

Wrap up your introduction with a thesis statement that clearly outlines the topics to be discussed in the body. This way, you set the stage for the essay's content and direction, sparking curiosity for the main body of the work.

Body of the Essay

Dive deep, but not without preparation. Before delving into the assessment, offer an unbiased overview of the topic being evaluated. This reaffirms your understanding and familiarity with the subject.

Each paragraph of the body should focus on one evaluation criterion, presenting either support or criticism for the point. This structured approach ensures clarity while presenting evidence to substantiate each point. For instance, discussing the benefits of a product, you can outline each advantage and back it up with supporting evidence like customer reviews or scientific studies.

Ensure a smooth flow of thoughts by linking paragraphs with transitional phrases like "in addition," "moreover," and "furthermore." Each paragraph should have a clear topic sentence, explanation, and supporting evidence or examples for easy understanding.

Your conclusion is where you make your final, compelling argument. It should focus on summarizing the points made according to your evaluation criteria. This isn't the place for new information but rather a concise summary of your work.

To conclude effectively, revisit your thesis and check whether it holds up or falls short based on your analysis. This completes the narrative arc and provides a solid stance on the topic. A thoughtful conclusion should consider the potential impact and outcomes of your evaluation, illustrating that your findings are based on the available data and recognizing the potential need for further exploration.

Evaluation Essay Examples

Now that we've covered the structure, let's take a look at some examples. Remember, an evaluation essay is just one type of essay that can be generated using tools like Jenni.ai. This AI-powered software can produce high-quality essays on any topic at impressive speeds. Here are some ideas to kickstart your assessment essay writing journey.

Evaluation Essay: Online Teaching vs. On-campus Teaching

In the face of technological evolution, education has seen a shift in teaching styles, with online learning platforms providing an alternative to traditional on-campus teaching. This essay will evaluate and compare the effectiveness of these two teaching styles, delving into various factors that contribute to their strengths and weaknesses.

The landscape of education has transformed significantly with the advent of online learning. This essay will scrutinize and juxtapose the effectiveness of online teaching against traditional on-campus teaching. The evaluation will take into account numerous factors that contribute to the success of each teaching style, focusing on their individual benefits and drawbacks.

On-campus Teaching

On-campus teaching, the time-tested method of education, has proven its effectiveness repeatedly. The physical classroom setting provides students direct access to their teachers, promoting immediate feedback and real-time interaction. Moreover, the hands-on learning, group discussions, and collaborative projects intrinsic to on-campus teaching cultivate crucial soft skills like communication and teamwork.

A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research reveals that students attending on-campus classes show higher academic performance and are more likely to complete their degrees compared to those in online classes (Bettinger & Loeb, 2017). However, on-campus teaching isn't without its challenges. It offers limited flexibility in scheduling and requires physical attendance, which can be inconvenient for students residing far from campus or those with mobility constraints.

Online Teaching

Online teaching, propelled by technological advancements and digital learning platforms, offers a compelling alternative. The most significant benefit of online teaching is its scheduling flexibility. Students can access classes and course materials from anywhere, at any time, providing a superior balance for work, family, and other commitments.

Online teaching democratizes education by enabling access for students in remote areas or with mobility challenges. The use of innovative teaching methods like interactive multimedia and gamification enhances engagement and enjoyment in learning.

Despite its numerous advantages, online teaching presents its own set of challenges. A major drawback is the lack of direct interaction with teachers and peers, potentially leading to delayed feedback and feelings of isolation. Furthermore, online classes demand a higher degree of self-motivation and discipline, which may be challenging for some students.

Both online teaching and on-campus teaching present their unique benefits and drawbacks. While on-campus teaching fosters direct interaction and immediate feedback, online teaching provides unmatched flexibility and accessibility. The choice between the two often depends on factors such as the course content, learning objectives, and student preferences.

A study by the University of Massachusetts reports that the academic performance of students in online classes is on par with those attending on-campus classes (Allen & Seaman, 2017). Furthermore, online classes are more cost-effective, eliminating the need for physical classrooms and related resources.

In conclusion, while both teaching styles have their merits, the effectiveness of each is heavily dependent on the subject matter, learning objectives, and the individual needs and preferences of students.

Citations: Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2017). Digital learning compass: Distance education enrollment report 2017. Babson Survey Research Group. Bettinger, E., & Loeb, S. (2017). Promises and pitfalls of online education. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2017, 347-384.

Evaluation essay: Analyze how the roles of females and males changed in recent romantic movies

Romantic movies have long been a popular genre, offering a glimpse into the complex and varied world of relationships. Over the years, the portrayal of gender roles in romantic movies has evolved significantly. This essay aims to evaluate and analyze how the roles of females and males have changed in recent romantic movies.

Historical Context of Gender Roles in Romantic Movies:

Gender roles have played a significant role in shaping the portrayal of romantic relationships in movies. In the past, traditional gender roles were often reinforced, with women playing the role of the damsel in distress, and men playing the role of the protector and provider.

However, over the years, the feminist movement and other social changes have led to a more nuanced portrayal of gender roles in romantic movies. Women are no longer just passive objects of desire, and men are not just dominant figures. Instead, both genders are portrayed as complex and multifaceted individuals with their desires, needs, and struggles.

Analysis of Recent Romantic Movies:

In recent years, romantic movies have become more diverse and inclusive, featuring a wider range of gender identities, sexual orientations, and cultural backgrounds. As a result, the portrayal of gender roles in these movies has also become more nuanced and complex.

One significant trend in recent romantic movies is the portrayal of female characters as strong, independent, and empowered. Female characters are no longer just passive objects of desire, waiting for the male lead to sweep them off their feet. Instead, they are shown to be capable of taking charge of their own lives, pursuing their goals, and making their own decisions.

For example, in the movie "Crazy Rich Asians," the female lead, Rachel, is portrayed as a strong and independent woman who stands up for herself and refuses to be intimidated by the wealthy and powerful people around her. Similarly, in the movie "The Shape of Water," the female lead, Elisa, is portrayed as a determined and resourceful woman who takes action to rescue the creature she has fallen in love with.

Another trend in recent romantic movies is the portrayal of male characters as vulnerable and emotionally expressive. Male characters are no longer just stoic and unemotional but are shown to have their insecurities, fears, and vulnerabilities.

For example, in the movie "Call Me By Your Name," the male lead, Elio, is shown to be sensitive and emotional, struggling with his feelings for another man. Similarly, in the movie "Moonlight," the male lead, Chiron, is shown to be vulnerable and emotionally expressive, struggling with his identity and his relationships with those around him.

However, while there have been significant changes in the portrayal of gender roles in recent romantic movies, there are still some aspects that remain problematic. For example, female characters are still often portrayed as objects of desire, with their value determined by their physical appearance and sexual appeal. Male characters are still often portrayed as dominant and aggressive, with their masculinity tied to their ability to assert control over others.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the portrayal of gender roles in recent romantic movies has evolved significantly, with female characters being portrayed as strong, independent, and empowered, and male characters being portrayed as vulnerable and emotionally expressive. These changes reflect the shifting social norms and values of our society and offer a more nuanced and complex portrayal of romantic relationships.

However, there are still some problematic aspects of the portrayal of gender roles in romantic movies, such as the objectification of female characters and the perpetuation of toxic masculinity. Filmmakers and audiences need to continue to push for greater diversity, inclusivity, and nuance in the portrayal of gender roles in romantic movies so that everyone can see themselves reflected in these stories.

"Crazy Rich Asians" Directed by Jon M. Chu, performances by Constance Wu, Henry Golding, and Michelle

Final Thoughts

The step-by-step guide and examples provided should have equipped you with the skills necessary to write a successful evaluation essay. However, crafting the perfect essay isn't a simple task; it demands practice, patience, and experience.

Incorporate Jenni.ai into your academic journey to revolutionize your writing experience. This advanced AI writing tool is designed to assist with a range of academic writing projects. With Jenni.ai, you can confidently tackle essays on any topic, easing your writing tasks considerably. Don't hesitate to register with Jenni.ai today ! Discover a world of writing opportunities and take your essay writing skills to new heights!

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

- Our Mission

- Why Is Assessment Important?

Asking students to demonstrate their understanding of the subject matter is critical to the learning process; it is essential to evaluate whether the educational goals and standards of the lessons are being met.

Assessment is an integral part of instruction, as it determines whether or not the goals of education are being met. Assessment affects decisions about grades, placement, advancement, instructional needs, curriculum, and, in some cases, funding. Assessment inspire us to ask these hard questions: "Are we teaching what we think we are teaching?" "Are students learning what they are supposed to be learning?" "Is there a way to teach the subject better, thereby promoting better learning?"

Today's students need to know not only the basic reading and arithmetic skills, but also skills that will allow them to face a world that is continually changing. They must be able to think critically, to analyze, and to make inferences. Changes in the skills base and knowledge our students need require new learning goals; these new learning goals change the relationship between assessment and instruction. Teachers need to take an active role in making decisions about the purpose of assessment and the content that is being assessed.

Grant Wiggins, a nationally recognized assessment expert, shared his thoughts on performance assessments, standardized tests, and more in an Edutopia.org interview . Read his answers to the following questions from the interview and reflect on his ideas:

- What distinction do you make between 'testing' and 'assessment'?

- Why is it important that teachers consider assessment before they begin planning lessons or projects?

- Standardized tests, such as the SAT, are used by schools as a predictor of a student's future success. Is this a valid use of these tests?

Do you agree with his statements? Why or why not? Discuss your opinions with your peers.

When assessment works best, it does the following:

- What is the student's knowledge base?

- What is the student's performance base?

- What are the student's needs?

- What has to be taught?

- What performance demonstrates understanding?

- What performance demonstrates knowledge?

- What performance demonstrates mastery?

- How is the student doing?

- What teaching methods or approaches are most effective?

- What changes or modifications to a lesson are needed to help the student?

- What has the student learned?

- Can the student talk about the new knowledge?

- Can the student demonstrate and use the new skills in other projects?

- Now that I'm in charge of my learning, how am I doing?

- Now that I know how I'm doing, how can I do better?

- What else would I like to learn?

- What is working for the students?

- What can I do to help the students more?

- In what direction should we go next?

Continue to the next section of the guide, Types of Assessment .

This guide is organized into six sections:

- Introduction

- Types of Assessment

- How Do Rubrics Help?

- Workshop Activities

- Resources for Assessment

- Campus Maps

- Faculties & Schools

Now searching for:

- Home

- Courses

- Subjects

- Design standards

- Methods

- Exams

- Online exams

- Interactive oral assessment

- Report

- Case study analysis or scenario-based questions

- Essay

- Newspaper article/editorial

- Literature review

- Student presentations

- Posters/infographics

- Portfolio

- Reflection

- Annotated bibliography

- OSCE/Online Practical Exam

- Viva voce

- Marking criteria and rubrics

- Review checklist

- Alterations

- Moderation

- Feedback

- Teaching

- Learning technology

- Professional learning

- Framework and policy

- Strategic projects

- About and contacts

- Help and resources

Essay assessments ask students to demonstrate a point of view supported by evidence. They allow students to demonstrate what they've learned and build their writing skills.