Technical Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Structure Included)

A technical report can either act as a cherry on top of your project or can ruin the entire dough.

Everything depends on how you write and present it.

A technical report is a sole medium through which the audience and readers of your project can understand the entire process of your research or experimentation.

So, you basically have to write a report on how you managed to do that research, steps you followed, events that occurred, etc., taking the reader from the ideation of the process and then to the conclusion or findings.

Sounds exhausting, doesn’t it?

Well hopefully after reading this entire article, it won’t.

However, note that there is no specific standard determined to write a technical report. It depends on the type of project and the preference of your project supervisor.

With that in mind, let’s dig right in!

What is a Technical Report? (Definition)

A technical report is described as a written scientific document that conveys information about technical research in an objective and fact-based manner. This technical report consists of the three key features of a research i.e process, progress, and results associated with it.

Some common areas in which technical reports are used are agriculture, engineering, physical, and biomedical science. So, such complicated information must be conveyed by a report that is easily readable and efficient.

Now, how do we decide on the readability level?

The answer is simple – by knowing our target audience.

A technical report is considered as a product that comes with your research, like a guide for it.

You study the target audience of a product before creating it, right?

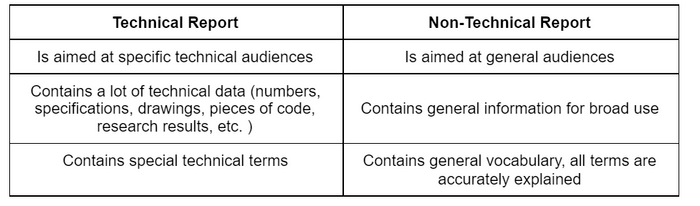

Similarly, before writing a technical report, you must keep in mind who your reader is going to be.

Whether it is professors, industry professionals, or even customers looking to buy your project – studying the target audience enables you to start structuring your report. It gives you an idea of the existing knowledge level of the reader and how much information you need to put in the report.

Many people tend to put in fewer efforts in the report than what they did in the actual research..which is only fair.

We mean, you’ve already worked so much, why should you go through the entire process again to create a report?

Well then, let’s move to the second section where we talk about why it is absolutely essential to write a technical report accompanying your project.

Read more: What is a Progress Report and How to Write One?

Importance of Writing a Technical Report

1. efficient communication.

Technical reports are used by industries to convey pertinent information to upper management. This information is then used to make crucial decisions that would impact the company in the future.

Examples of such technical reports include proposals, regulations, manuals, procedures, requests, progress reports, emails, and memos.

2. Evidence for your work

Most of the technical work is backed by software.

However, graduation projects are not.

So, if you’re a student, your technical report acts as the sole evidence of your work. It shows the steps you took for the research and glorifies your efforts for a better evaluation.

3. Organizes the data

A technical report is a concise, factual piece of information that is aligned and designed in a standard manner. It is the one place where all the data of a project is written in a compact manner that is easily understandable by a reader.

4. Tool for evaluation of your work

Professors and supervisors mainly evaluate your research project based on the technical write-up for it. If your report is accurate, clear, and comprehensible, you will surely bag a good grade.

A technical report to research is like Robin to Batman.

Best results occur when both of them work together.

So, how can you write a technical report that leaves the readers in a ‘wow’ mode? Let’s find out!

How to Write a Technical Report?

When writing a technical report, there are two approaches you can follow, depending on what suits you the best.

- Top-down approach- In this, you structure the entire report from title to sub-sections and conclusion and then start putting in the matter in the respective chapters. This allows your thought process to have a defined flow and thus helps in time management as well.

- Evolutionary delivery- This approach is suitable if you’re someone who believes in ‘go with the flow’. Here the author writes and decides as and when the work progresses. This gives you a broad thinking horizon. You can even add and edit certain parts when some new idea or inspiration strikes.

A technical report must have a defined structure that is easy to navigate and clearly portrays the objective of the report. Here is a list of pages, set in the order that you should include in your technical report.

Cover page- It is the face of your project. So, it must contain details like title, name of the author, name of the institution with its logo. It should be a simple yet eye-catching page.

Title page- In addition to all the information on the cover page, the title page also informs the reader about the status of the project. For instance, technical report part 1, final report, etc. The name of the mentor or supervisor is also mentioned on this page.

Abstract- Also referred to as the executive summary, this page gives a concise and clear overview of the project. It is written in such a manner that a person only reading the abstract can gain complete information on the project.

Preface – It is an announcement page wherein you specify that you have given due credits to all the sources and that no part of your research is plagiarised. The findings are of your own experimentation and research.

Dedication- This is an optional page when an author wants to dedicate their study to a loved one. It is a small sentence in the middle of a new page. It is mostly used in theses.

Acknowledgment- Here, you acknowledge the people parties, and institutions who helped you in the process or inspired you for the idea of it.

Table of contents – Each chapter and its subchapter is carefully divided into this section for easy navigation in the project. If you have included symbols, then a similar nomenclature page is also made. Similarly, if you’ve used a lot of graphs and tables, you need to create a separate content page for that. Each of these lists begins on a new page.

Introduction- Finally comes the introduction, marking the beginning of your project. On this page, you must clearly specify the context of the report. It includes specifying the purpose, objectives of the project, the questions you have answered in your report, and sometimes an overview of the report is also provided. Note that your conclusion should answer the objective questions.

Central Chapter(s)- Each chapter should be clearly defined with sub and sub-sub sections if needed. Every section should serve a purpose. While writing the central chapter, keep in mind the following factors:

- Clearly define the purpose of each chapter in its introduction.

- Any assumptions you are taking for this study should be mentioned. For instance, if your report is targeting globally or a specific country. There can be many assumptions in a report. Your work can be disregarded if it is not mentioned every time you talk about the topic.

- Results you portray must be verifiable and not based upon your opinion. (Big no to opinions!)

- Each conclusion drawn must be connected to some central chapter.

Conclusion- The purpose of the conclusion is to basically conclude any and everything that you talked about in your project. Mention the findings of each chapter, objectives reached, and the extent to which the given objectives were reached. Discuss the implications of the findings and the significant contribution your research made.

Appendices- They are used for complete sets of data, long mathematical formulas, tables, and figures. Items in the appendices should be mentioned in the order they were used in the project.

References- This is a very crucial part of your report. It cites the sources from which the information has been taken from. This may be figures, statistics, graphs, or word-to-word sentences. The absence of this section can pose a legal threat for you. While writing references, give due credit to the sources and show your support to other people who have studied the same genres.

Bibliography- Many people tend to get confused between references and bibliography. Let us clear it out for you. References are the actual material you take into your research, previously published by someone else. Whereas a bibliography is an account of all the data you read, got inspired from, or gained knowledge from, which is not necessarily a direct part of your research.

Style ( Pointers to remember )

Let’s take a look at the writing style you should follow while writing a technical report:

- Avoid using slang or informal words. For instance, use ‘cannot’ instead of can’t.

- Use a third-person tone and avoid using words like I, Me.

- Each sentence should be grammatically complete with an object and subject.

- Two sentences should not be linked via a comma.

- Avoid the use of passive voice.

- Tenses should be carefully employed. Use present for something that is still viable and past for something no longer applicable.

- Readers should be kept in mind while writing. Avoid giving them instructions. Your work is to make their work of evaluation easier.

- Abbreviations should be avoided and if used, the full form should be mentioned.

- Understand the difference between a numbered and bulleted list. Numbering is used when something is explained sequence-wise. Whereas bullets are used to just list out points in which sequence is not important.

- All the preliminary pages (title, abstract, preface..) should be named in small roman numerals. ( i, ii, iv..)

- All the other pages should be named in Arabic numerals (1,2,3..) thus, your report begins with 1 – on the introduction page.

- Separate long texts into small paragraphs to keep the reader engaged. A paragraph should not be more than 10 lines.

- Do not incorporate too many fonts. Use standard times new roman 12pt for the text. You can use bold for headlines.

Proofreading

If you think your work ends when the report ends, think again. Proofreading the report is a very important step. While proofreading you see your work from a reader’s point of view and you can correct any small mistakes you might have done while typing. Check everything from content to layout, and style of writing.

Presentation

Finally comes the presentation of the report in which you submit it to an evaluator.

- It should be printed single-sided on an A4 size paper. double side printing looks chaotic and messy.

- Margins should be equal throughout the report.

- You can use single staples on the left side for binding or use binders if the report is long.

AND VOILA! You’re done.

…and don’t worry, if the above process seems like too much for you, Bit.ai is here to help.

Read more: Technical Manual: What, Types & How to Create One? (Steps Included)

Bit.ai : The Ultimate Tool for Writing Technical Reports

What if we tell you that the entire structure of a technical report explained in this article is already done and designed for you!

Yes, you read that right.

With Bit.ai’s 70+ templates , all you have to do is insert your text in a pre-formatted document that has been designed to appeal to the creative nerve of the reader.

You can even add collaborators who can proofread or edit your work in real-time. You can also highlight text, @mention collaborators, and make comments!

Wait, there’s more! When you send your document to the evaluators, you can even trace who read it, how much time they spent on it, and more.

Exciting, isn’t it?

Start making your fabulous technical report with Bit.ai today!

Few technical documents templates you might be interested in:

- Status Report Template

- API Documentation

- Product Requirements Document Template

- Software Design Document Template

- Software Requirements Document Template

- UX Research Template

- Issue Tracker Template

- Release Notes Template

- Statement of Work

- Scope of Work Template

Wrap up(Conclusion)

A well structured and designed report adds credibility to your research work. You can rely on bit.ai for that part.

However, the content is still yours so remember to make it worth it.

After finishing up your report, ask yourself:

Does the abstract summarize the objectives and methods employed in the paper?

Are the objective questions answered in your conclusion?

What are the implications of the findings and how is your work making a change in the way that particular topic is read and conceived?

If you find logical answers to these, then you have done a good job!

Remember, writing isn’t an overnight process. ideas won’t just arrive. Give yourself space and time for inspiration to strike and then write it down. Good writing has no shortcuts, it takes practice.

But at least now that you’ve bit.ai in the back of your pocket, you don’t have to worry about the design and formatting!

Have you written any technical reports before? If yes, what tools did you use? Do let us know by tweeting us @bit_docs.

Further reads:

How To Create An Effective Status Report?

7 Types of Reports Your Business Certainly Needs!

What is Project Status Report Documentation?

Scientific Paper: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps and Format)

Business Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Format)

How to Write Project Reports that ‘Wow’ Your Clients? (Template Included)

Business Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Format)

Internship Cover Letter: How to Write a Perfect one?

Related posts

How to skyrocket your sales with a sales dashboard (template included), how to write an impressive business one pager (template included), resource management plan: what is it & how to create it, company wiki vs knowledge base: understanding the key differences, top real-time document collaboration tools for team productivity, 7 shocking reasons to use vpn at work.

About Bit.ai

Bit.ai is the essential next-gen workplace and document collaboration platform. that helps teams share knowledge by connecting any type of digital content. With this intuitive, cloud-based solution, anyone can work visually and collaborate in real-time while creating internal notes, team projects, knowledge bases, client-facing content, and more.

The smartest online Google Docs and Word alternative, Bit.ai is used in over 100 countries by professionals everywhere, from IT teams creating internal documentation and knowledge bases, to sales and marketing teams sharing client materials and client portals.

👉👉Click Here to Check out Bit.ai.

Recent Posts

Maximizing digital agency success: 4 ways to leverage client portals, how to create wikis for employee onboarding & training, what is support documentation: key insights and types, how to create a smart company wiki | a guide by bit.ai, 9 must-have internal communication software in 2024, 21 business productivity tools to enhance work efficiency.

- Research Guides

- University Libraries

- Advanced Research Topics

Technical Reports

- What is a Technical report?

- Find Technical Reports

- Print & Microform Tech Reports in the Library

- Author Profile

What is a Technical Report?

What is a Technical Report?

"A technical report is a document written by a researcher detailing the results of a project and submitted to the sponsor of that project." TRs are not peer-reviewed unless they are subsequently published in a peer-review journal.

Characteristics (TRs vary greatly): Technical reports ....

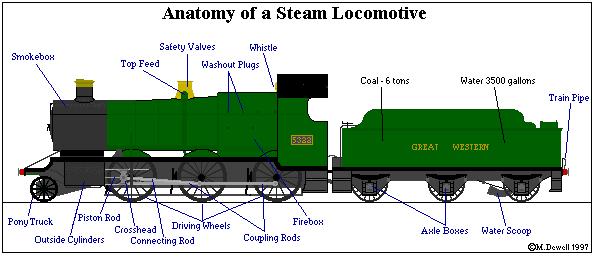

- may contain data, design criteria, procedures, literature reviews, research history, detailed tables, illustrations/images, explanation of approaches that were unsuccessful.

- may be published before the corresponding journal literature; may have more or different details than its subsequent journal article.

- may contain less background information since the sponsor already knows it

- classified and export controlled reports

- may contain obscure acronyms and codes as part of identifying information

Disciplines:

- Physical sciences, engineering, agriculture, biomedical sciences, and the social sciences. education etc.

Documents research and development conducted by:

- government agencies (NASA, Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Energy (DOE) are top sponsors of research

- commercial companies

- non-profit, non-governmental organizations

- Educational Institutions

- Issued in print, microform, digital

- Older TRs may have been digitized and are available in fulltext on the Intranet

- Newer TRs should be born digital

Definition used with permission from Georgia Tech. Other sources: Pinelli & Barclay (1994).

- Nation's Report Card: State Reading 2002, Report for Department of Defense Domestic Dependent Elementary and Secondary Schools. U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Sciences The National Assessment of Educational Progress Reading 2002 The Nation’s

- Study for fabrication, evaluation, and testing of monolayer woven type materials for space suit insulation NASA-CR-166139, ACUREX-TR-79-156. May 1979. Reproduced from the microfiche.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Find Technical Reports >>

- Last Updated: Sep 1, 2023 11:06 AM

- URL: https://tamu.libguides.com/TR

Libraries | Research Guides

Technical reports, technical reports: a definition, search engines & databases, multi-disciplinary technical report repositories, topical technical report repositories.

"A technical report is a document that describes the process, progress, or results of technical or scientific research or the state of a technical or scientific research problem. It might also include recommendations and conclusions of the research." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technical_report

Technical reports are produced by corporations, academic institutions, and government agencies at all levels of government, e.g. state, federal, and international. Technical reports are not included in formal publication and distribution channels and therefore fall into the category of grey literature .

- Science.gov Searches over 60 databases and over 2,200 scientific websites hosted by U.S. federal government agencies. Not limited to tech reports.

- WorldWideScience.org A global science gateway comprised of national and international scientific databases and portals, providing real-time searching and translation of globally-dispersed multilingual scientific literature.

- Open Grey System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe, is your open access to 700.000 bibliographical references. more... less... OpenGrey covers Science, Technology, Biomedical Science, Economics, Social Science and Humanities.

- National Technical Reports Library (NTRL) This link opens in a new window The National Technical Reports Library provides indexing and access to a collection of more than two million historical and current government technical reports of U.S. government-sponsored research. Full-text available for 700,000 of the 2.2 million items described. Dates covered include 1900-present.

- Argonne National Lab: Scientific Publications While sponsored by the US Dept of Energy, research at Argonne National Laboratory is wide ranging (see Research Index )

- Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC) The Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC®) has served the information needs of the Defense community for more than 65 years. It provides technical research, development, testing & evaluation information; including but not limited to: journal articles, conference proceedings, test results, theses and dissertations, studies & analyses, and technical reports & memos.

- HathiTrust This repository of books digitized by member libraries includes a large number of technical reports. Search by keywords, specific report title, or identifiers.

- Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL) LBNL a multiprogram science lab in the national laboratory system supported by the U.S. Department of Energy through its Office of Science. It is managed by the University of California and is charged with conducting unclassified research across a wide range of scientific disciplines.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) NIST is one of the nation's oldest physical science laboratories.

- RAND Corporation RAND's research and analysis address issues that impact people around the world including security, health, education, sustainability, growth, and development. Much of this research is carried out on behalf of public and private grantors and clients.

- TRAIL Technical Report Archive & Image Library Identifies, acquires, catalogs, digitizes and provides unrestricted access to U.S. government agency technical reports. TRAIL is a membership organization . more... less... Majority of content is pre-1976, but some reports after that date are included.

Aerospace / Aviation

- Contrails 20th century aerospace research, hosted at the Illinois Institute of Technology

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory Technical Reports Server repository for digital copies of technical publications authored by JPL employees. It includes preprints, meeting papers, conference presentations, some articles, and other publications cleared for external distribution from 1992 to the present.

- NTRS - NASA Technical Reports Server The NASA STI Repository (also known as the NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS)) provides access to NASA metadata records, full-text online documents, images, and videos. The types of information included are conference papers, journal articles, meeting papers, patents, research reports, images, movies, and technical videos – scientific and technical information (STI) created or funded by NASA. Includes NTIS reports.

Computing Research

- Computing Research Repository

- IBM Technical Paper Archive

- Microsoft Research

- INIS International Nuclear Information System One of the world's largest collections of published information on the peaceful uses of nuclear science and technology.

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory Research Library Primary subject areas covered include chemistry, physics, materials science, biological and environmental sciences, computer science, mathematics, engineering, nuclear technology, and homeland security.

- OSTI.gov The primary search tool for DOE science, technology, and engineering research and development results more... less... over 70 years of research results from DOE and its predecessor agencies. Research results include journal articles/accepted manuscripts and related metadata; technical reports; scientific research datasets and collections; scientific software; patents; conference and workshop papers; books and theses; and multimedia

- OSTI Open Net Provides access to over 495,000 bibliographic references and 147,000 recently declassified documents, including information declassified in response to Freedom of Information Act requests. In addition to these documents, OpenNet references older document collections from several DOE sources.

Environment

- National Service Center for Environmental Publications From the Environmental Protection Agency

- US Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) Digital Library See in particular the option to search technical reports by the Waterways Experiment Station, Engineering Research and Development Center, and districts .

- National Clearinghouse for Science, Technology and the Law (NCSTL) Forensic research at the intersection of science, technology and law.

Transportation

- ROSA-P National Transportation Library Full-text digital publications, datasets, and other resources. Legacy print materials that have been digitized are collected if they have historic, technical, or national significance.

- Last Updated: Jul 13, 2022 11:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/techreports

Penn State University Libraries

Technical reports, recognizing technical reports, recommendations for finding technical reports, databases with technical reports, other tools for finding technical reports.

- Direct Links to Organizations with Technical Reports

- Techical report collections at Penn State

- How to Write

Engineering Instruction Librarian

Engineering Librarian

Technical reports describe the process, progress, or results of technical or scientific research and usually include in-depth experimental details, data, and results. Technical reports are usually produced to report on a specific research need and can serve as a report of accountability to the organization funding the research. They provide access to the information before it is published elsewhere. Technical Reports are usually not peer reviewed. They need to be evaluated on how the problem, research method, and results are described.

A technical report citation will include a report number and will probably not have journal name.

Technical reports can be divided into two general categories:

- Non-Governmental Reports- these are published by companies and engineering societies, such as Lockheed-Martin, AIAA (American Institute of Aeronautical and Astronautics), IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), or SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers).

- Governmental Reports- the research conducted in these reports has been sponsored by the United States or an international government body as well as state and local governments.

Some technical reports are cataloged as books, which you can search for in the catalog, while others may be located in databases, or free online. The boxes below list databases and online resources you can use to locate a report.

If you’re not sure where to start, try to learn more about the report by confirming the full title or learning more about the publication information.

Confirm the title and locate the report number in NTRL.

Search Google Scholar, the HathiTrust, or WorldCat. This can verify the accuracy of the citation and determine if the technical report was also published in a journal or conference proceeding or under a different report number.

Having trouble finding a report through Penn State? If we don’t have access to the report, you can submit an interlibrary loan request and we will get it for you from another library. If you have any questions, you can always contact a librarian!

- National Technical Reports Library (NTRL) NTRL is the preeminent resource for accessing the latest US government sponsored research, and worldwide scientific, technical, and engineering information. Search by title to determine report number.

- Engineering Village Engineering Village is the most comprehensive interdisciplinary engineering database in the world with over 5,000 engineering journals and conference materials dating from 1884. Has citations to many ASME, ASCE, SAE, and other professional organizations' technical papers. Search by author, title, or report number.

- IEEE Xplore Provides access to articles, papers, reports, and standards from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

- ASABE Technical Library Provides access to all of the recent technical documents published by the American Society of Agricultural Engineers.

- International Nuclear Information System (INIS) Database Provides access to nuclear science and technology technical reports.

- NASA Technical Reports Server Contains the searchable NACA Technical Reports collection, NASA Technical Reports collection and NIX collection of images, movies, and videos. Includes the full text and bibliographic records of selected unclassified, publicly available NASA-sponsored technical reports. Coverage: NACA reports 1915-1958, NASA reports since 1958.

- OSTI Technical Reports Full-text of Department of Energy (DOE) funded science, technology, and engineering technical reports. OSTI has replaced SciTech Connect as the primary search tool for Department of Energy (DOE) funded science, technology, and engineering research results. It provides access to all the information previously available in SciTech Connect, DOE Information Bridge, and Energy Citations Database.

- ERIC (ProQuest) Provides access to technical reports and other education-related materials. ERIC is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES).

- Transportation Research International Documentation (TRID) TRID is a newly integrated database that combines the records from TRB's Transportation Research Information Services (TRIS) Database and the OECD's Joint Transport Research Centre's International Transport Research Documentation (ITRD) Database. TRID provides access to over 900,000 records of transportation research worldwide.

- TRAIL Technical Reports Archive & Image Library Provide access to federal technical reports issued prior to 1975.

- Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC) The largest central resource for Department of Defense and government-funded scientific, technical, engineering, and business related information.

- Correlation Index of Technical Reports (AD-PB Reports) Publication Date: 1958

- Criss-cross directory of NASA "N" numbers and DOD "AD" numbers, 1962-1986

Print indexes to technical reports :

- Government Reports Announcements & Index (1971-1996)

- Government Reports Announcements (1946-1975)

- U.S. Government Research & Development Reports (1965-1971)

- U.S. Government Research Reports (1954-1964)

- Bibliography of Technical Reports (1949-1954)

- Bibliography of Scientific and Industrial Reports (1946-1949)

- Next: Direct Links to Organizations with Technical Reports >>

- Last Updated: Oct 5, 2023 2:56 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/techreports

Guide to Technical Reports: What it is and How to Write it

Introduction.

You want to improve the customers’ experience with your products, but your team is too busy creating and/or updating products to write a report.

Getting them ready for the task is another problem you need to overcome.

Who wants to write a technical report on the exact process you just conducted?

Exactly, no one.

Honestly, we get it: you’re supposed to be managing coding geniuses — not writers.

But it's one of those things you need to get it done for sound decision-making and ensuring communication transparency. In many organizations, engineers spend nearly 40 percent of their time writing technical reports.

If you're wondering how to write good technical reports that convey your development process and results in the shortest time possible, we've got you covered.

Let’s start with the basics.

What is a technical report?

A technical report is a piece of documentation developed by technical writers and/or the software team outlining the process of:

- The research conducted.

- How it advances.

- The results obtained.

In layman's terms, a technical report is created to accompany a product, like a manual. Along with the research conducted, a technical report also summarizes the conclusion and recommendations of the research.

The idea behind building technical documentation is to create a single source of truth about the product and including any product-related information that may be insightful down the line.

Industries like engineering, IT, medicine and marketing use technical documentation to explain the process of how a product was created.

Ideally, you should start documenting the process when a product is in development, or already in use. A good technical report has the following elements:

- Functionality.

- Development.

Gone are the days when technical reports used to be boring yawn-inducing dry text. Today, you can make them interactive and engaging using screenshots, charts, diagrams, tables, and similar visual assets.

💡 Related resource: 5 Software Documentation Challenges & How To Overcome Them

Who is responsible for creating reports?

Anyone with a clear knowledge of the industry and the product can write a technical report by following simple writing rules.

It's possible your developers will be too busy developing the product to demonstrate the product development process.

Keeping this in mind, you can have them cover the main points and send off the writing part to the writing team. Hiring a technical writer can also be beneficial, who can collaborate with the development and operations team to create the report.

Why is technical documentation crucial for a business?

If you’re wondering about the benefits of writing a report, here are three reasons to convince you why creating and maintaining technical documentation is a worthy cause.

1. Easy communication of the process

Technical reports give you a more transparent way to communicate the process behind the software development to the upper management or the stakeholders.

You can also show the technical report to your readers interested in understanding the behind the scenes (BTS) action of product development. Treat this as a chance to show value and the methodology behind the same.

🎓 The Ultimate Product Development Checklist

2. Demonstrating the problem & solution

You can use technical documentation tools to create and share assets that make your target audience aware of the problem.

Technical reports can shed more light on the problem they’re facing while simultaneously positioning your product as the best solution for it.

3. Influence upper management decisions

Technical reports are also handy for conveying the product's value and functionality to the stakeholders and the upper management, opening up the communication channel between them and other employees.

You can also use this way to throw light on complex technical nuances and help them understand the jargon better.

Benefits of creating technical reports

The following are some of the biggest benefits of technical documentation:

- Cuts down customer support tickets, enabling users to easily use the product without technical complications.

- Lets you share detailed knowledge of the product's usability and potential, showing every aspect to the user as clearly as possible.

- Enables customer success teams to answer user questions promptly and effectively.

- Creates a clear roadmap for future products.

- Improves efficiency for other employees in the form of technical training.

The 5 types of technical reports

There are not just one but five types of technical reports you can create. These include:

1. Feasibility report

This report is prepared during the initial stages of software development to determine whether the proposed project will be successful.

2. Business report

This report outlines the vision, objectives and goals of the business while laying down the steps needed to crush those goals.

3. Technical specification report

This report specifies the essentials for a product or project and details related to the development and design.

4. Research report

This report includes information on the methodology and outcomes based on any experimentation.

5. Recommendation report

This report contains all the recommendations the DevOps team can use to solve potential technical problems.

The type of technical report you choose depends on certain factors like your goals, the complexity of the product and its requirements.

What are the key elements of a technical report?

Following technical documentation best practices , you want the presented information to be clear and well-organized. Here are the elements (or sections) a typical technical report should have:

This part is simple and usually contains the names of the authors, your company name, logo and so on.

Synopses are usually a couple of paragraphs long, but it sets the scene for the readers. It outlines the problem to be solved, the methods used, purpose and concept of the report.

You can’t just write the title of the project here, and call it a day. This page should also include information about the author, their company position and submission date, among other things. The name and position of the supervisor or mentor is also mentioned here.

The abstract is a brief summary of the project addressed to the readers. It gives a clear overview of the project and helps readers decide whether they want to read the report.

The foreword is a page dedicated to acknowledging all the sources used to write this report. It gives assurance that no part of the report is plagiarized and all the necessary sources have been cited and given credit to.

Acknowledgment

This page is used for acknowledging people and institutions who helped in completing the report.

Table of Contents

Adding a table of contents makes navigating from one section to another easier for readers. It acts as a compass for the structure of the report.

List of illustrations

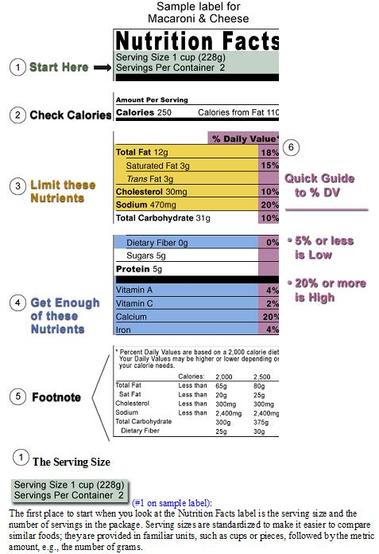

This part contains all the graphs, diagrams, images, charts and tables used across the report. Ideally, it should have all the materials supporting the content presented in the report.

The introduction is a very crucial part of the project that should specify the context of the project, along with its purpose and objective. Things like background information, scope of work and limitations are discussed under this section.

The body of the report is generally divided into sections and subsections that clearly define the purpose of each area, ideas, purpose and central scope of work.

Conclusion

The conclusion should have an answer to all the questions and arguments made in the introduction or body of the report. It should answer the objectives of the findings, the results achieved and any further observations made.

This part lists the mathematical formulas and data used in the content, following the same order as they were used in the report.

The page cites the sources from which information was taken. Any quotes, graphs and statistics used in your report need to be credited to the original source.

A glossary is the index of all the terms and symbols used in the report.

Bibliography

The bibliography outlines the names of all the books and data you researched to gain knowledge on the subject matter.

How to create your own technical report in 6 simple steps

To create a high-quality technical report, you need to follow these 5 steps.

Step 1: Research

If you’ve taken part in the product development process, this part comes easily. But if you’ve not participated in the development (or are hiring a writer), you need to learn as much about the product as possible to understand it in and out.

While doing your research, you need to think from your target users' perspectives.

- You have to know if they’re tech-savvy or not. Whether they understand industry technicalities and jargon or not?

- What goals do you want to achieve with the report? What do you want the final outcome to look like for your users?

- What do you want to convey using the report and why?

- What problems are you solving with the report, and how are you solving them?

This will help you better understand the audience you’re writing for and create a truly valuable document.

Step 2: Design

You need to make it simple for users to consume and navigate through the report.

The structure is a crucial element to help your users get familiar with your product and skim through sections. Some points to keep in mind are:

- Outlining : Create an outline of the technical report before you start writing. This will ensure that the DevOps team and the writer are on the same page.

- Table of contents : Make it easy for your users to skip to any part of the report they want without scrolling through the entire document.

- Easy to read and understand : Make the report easy to read and define all technical terms, if your users aren’t aware of them. Explain everything in detail, adding as many practical examples and case studies as possible.

- Interactive : Add images, screenshots, or any other visual aids to make the content interactive and engaging.

- Overview : Including a summary of what's going to be discussed in the next sections adds a great touch to the report.

- FAQ section : An underrated part of creating a report is adding a FAQ section at the end that addresses users' objections or queries regarding the product.

Step 3: Write

Writing content is vital, as it forms the body of the report. Ensure the content quality is strong by using the following tips:

- Create a writing plan.

- Ensure the sentence structure and wording is clear.

- Don’t repeat information.

- Explain each and every concept precisely.

- Maintain consistency in the language used throughout the document

- Understand user requirements and problems, and solve them with your content.

- Avoid using passive voice and informal words.

- Keep an eye out for grammatical errors.

- Make the presentation of the report clean.

- Regularly update the report over time.

- Avoid using abbreviations.

Regardless of whether you hire a writer or write the report yourself, these best practices will help you create a great technical report that provides value to the reader.

Step 4: Format

The next step of writing technical reports is formatting.

You can either use the company style guide provided to you or follow the general rules of report formatting. Here is a quick rundown:

1. Page Numbering (excluding cover page, and back covers).

2. Headers.

- Make it self-explanatory.

- Must be parallel in phrasing.

- Avoid “lone headings.”

- Avoid pronouns .

3. Documentation.

- Cite borrowed information.

- Use in-text citations or a separate page for the same.

Step 5: Proofread

Don’t finalize the report for publishing before proofreading the entire documentation.

Our best proofreading advice is to read it aloud after a day or two. If you find any unexplained parts or grammatical mistakes, you can easily fix them and make the necessary changes. You can also consider getting another set of eyes to spot the mistakes you may have missed.

Step 6: Publish

Once your technical report is ready, get it cross-checked by an evaluator. After you get their approval, publish on your website as a gated asset — or print it out as an A4 version for presentation.

Extra Step: Refreshing

Okay, we added an extra step, but hear us out: your job is not finished after hitting publish.

Frequent product updates mean you should also refresh the report every now and then to reflect these changes. A good rule of thumb is to refresh any technical documentation every eight to twelve months and update it with the latest information.

Not only will this eliminate confusion but also ensure your readers get the most value out of the document.

Making successful technical reports with Scribe

How about developing technical reports faster and without the hassle?

With Scribe and Scribe’s newest feature, Pages , you can do just that.

Scribe is a leading process documentation tool that does the documenting for you, pat down to capturing and annotating screenshots. Here's one in action.

Pages lets you compile all your guides, instructions and SOPs in a single document, giving you an elaborate and digital technical report you can share with both customers and stakeholders.

{{banner-default="/banner-ads"}}

Here is a Page showing you how to use Scribe Pages .

Examples of good technical reports

You can use these real-life examples of good technical reports for inspiration and guidance!

- Mediums API Documentation

- Twilio Docs

- The AWS PRD for Container-based Products

Signing off…

Now you know how to write technical documentation , what's next?

Writing your first technical report! Remember, it’s not rocket science. Simply follow the technical writing best practices and the format we shared and you'll be good to go.

Ready to try Scribe?

Related content

- Scribe Gallery

- Help Center

- What's New

- Careers We're Hiring!

- Contact Sales

Technical Reports

- Technical Reports Databases

- Definition and Thesauri

What is a Technical Report?

A technical report is a document written by a researcher detailing the results of a project and submitted to the sponsor of that project. Many of Georgia Tech's reports are government sponsored and are on microfiche. DOE, NASA and the Department of Defense are top sponsors. A number of U.S. Government sponsors now make technical reports available full image via the internet .

Although technical reports are very heterogeneous, they tend to possess the following characteristics:

- technical reports may be published before the corresponding journal literature

- content may be more detailed than the corresponding journal literature, although there may be less background information since the sponsor already knows it

- technical reports are usually not peer reviewed unless the report is separately published as journal literature

- classified and export controlled reports have restricted access.

- obscure acronyms and codes are frequently used

- DTIC Thesaurus

- NASA Thesaurus (both volumes): Volume 1, Hierarchical Listing With Definitions. Volume 2, Rotated Term Display

- Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms

- Report Series Codes Dictionary. Library Catalog record Z6945.A2 R45 1986

Acknowledgments

The authors of this Guide used material from previous Georgia Tech Library Research Guides.

- << Previous: Technical Reports Databases

- Last Updated: Nov 22, 2023 10:58 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.gatech.edu/techreports

Chemistry: Technical Reports

- Chemistry Home

- Databases and Preprint Servers

- Dictionaries and Handbooks

- Encyclopedias

- Patents & Trademarks

- Laboratory Safety

- Theses and Dissertations

- Technical Reports

- KiltHub Repository This link opens in a new window

About Technical Reports

Technical reports online.

- NTIS - now the National Technical Reports Library (NTRL) This link opens in a new window Describes government technical reports from the U.S. and other countries. Good for locating reports that one should be able to obtain for free from NASA, DOD, DOE, EPA and other agencies. NTRL has the full text of more than 800,000 technical reports.

Free computer science citation database with some full text available. Lists the most frequently cited authors and documents in computer science, as well as impact ratings. Also provides algorithms, metadata, services, techniques, and software.

Technical Report Collections at Other Universities

University of Maryland - a U.S. Government Document Depository Library for scientific and technical reports from several agencies

Indiana University Computer Science Department

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Stanford University

U.C. Berkeley

University of Washington Computer Science & Engineering Department

Carnegie Mellon Technical Reports

- Computer Science

- Human-Computer Interaction Institute (HCII)

- Information Technology Center (ITC)

- Institute for Complex Engineered Systems (ICES) [formerly: Engineering Design Research Center ]

- Institute for Software Research (ISR)

- Language Technologies Institute (LTI)

- Machine Learning Department [formerly: Center for Automated Learning and Discovery]

- Parallel Data Laboratory (PDL)

- Robotics Institute

- Software Engineering Institute (SEI)

- Statistics Department

- Philosophy Department

U.S. Government Public Technical Reports

A concise list of government agencies with free access to their technical reports:

Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC)

DTIC helps the Department of Defense (DoD) community access pertinent scientific and technical information to meet mission needs more effectively.

Information Bridge (U.S. Department of Energy)

Provides free public access to over 230,000 full-text documents and bibliographic citations of Department of Energy (DOE) research report literature. Documents are primarily from 1991-present and were produced by DOE, the DOE contractor community, and/or DOE grantees.

Technical Report Archive and Image Library (TRAIL)

A collaborative project to digitize, archive, and provide persistent and unrestricted access to federal technical reports issued prior to 1975.

Army Corps of Engineers Research and Development Center (CRREL)

The results of CRREL's research projects are published in a technical report series covering topics of interest to Civil and Environmental Engineers. Reports from 1995 to present are available, as well as some older ones.

NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS)

1920–present. Indexes technical reports, conference papers, journal articles, and other publications sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and its predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). NACA Reports, Technical Notes, and Technical Memoranda are available in fulltext from 1917–1958. Some NASA reports are fulltext.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Fulltext of more than 7,000 archival and current EPA documents.

Specialized Technical Reports

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Caltech)

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL)

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL)

Los Alamos Technical Reports

IBM Research -Technical Paper Search

Hewlett Packard Labs Technical Reports

Microsoft Research Technical Reports

- << Previous: Theses and Dissertations

- Next: KiltHub Repository >>

- Last Updated: Jan 9, 2024 3:06 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cmu.edu/Chemistry

Cookies on our website

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We'd like to set additional cookies to understand how you use our site. And we'd like to serve you some cookies set by other services to show you relevant content.

- Accessibility

- Staff search

- External website

- Schools & services

- Sussex Direct

- Professional services

- Schools and services

- Engineering and Informatics

- Student handbook

- Engineering and Design

- Study guides

Guide to Technical Report Writing

- Back to previous menu

- Guide to Laboratory Writing

School of Engineering and Informatics (for staff and students)

Table of contents

1 Introduction

2 structure, 3 presentation, 4 planning the report, 5 writing the first draft, 6 revising the first draft, 7 diagrams, graphs, tables and mathematics, 8 the report layout, 10 references to diagrams, graphs, tables and equations, 11 originality and plagiarism, 12 finalising the report and proofreading, 13 the summary, 14 proofreading, 15 word processing / desktop publishing, 16 recommended reading.

A technical report is a formal report designed to convey technical information in a clear and easily accessible format. It is divided into sections which allow different readers to access different levels of information. This guide explains the commonly accepted format for a technical report; explains the purposes of the individual sections; and gives hints on how to go about drafting and refining a report in order to produce an accurate, professional document.

A technical report should contain the following sections;

For technical reports required as part of an assessment, the following presentation guidelines are recommended;

There are some excellent textbooks contain advice about the writing process and how to begin (see Section 16 ). Here is a checklist of the main stages;

- Collect your information. Sources include laboratory handouts and lecture notes, the University Library, the reference books and journals in the Department office. Keep an accurate record of all the published references which you intend to use in your report, by noting down the following information; Journal article: author(s) title of article name of journal (italic or underlined) year of publication volume number (bold) issue number, if provided (in brackets) page numbers Book: author(s) title of book (italic or underlined) edition, if appropriate publisher year of publication N.B. the listing of recommended textbooks in section 2 contains all this information in the correct format.

- Creative phase of planning. Write down topics and ideas from your researched material in random order. Next arrange them into logical groups. Keep note of topics that do not fit into groups in case they come in useful later. Put the groups into a logical sequence which covers the topic of your report.

- Structuring the report. Using your logical sequence of grouped ideas, write out a rough outline of the report with headings and subheadings.

N.B. the listing of recommended textbooks in Section 16 contains all this information in the correct format.

Who is going to read the report? For coursework assignments, the readers might be fellow students and/or faculty markers. In professional contexts, the readers might be managers, clients, project team members. The answer will affect the content and technical level, and is a major consideration in the level of detail required in the introduction.

Begin writing with the main text, not the introduction. Follow your outline in terms of headings and subheadings. Let the ideas flow; do not worry at this stage about style, spelling or word processing. If you get stuck, go back to your outline plan and make more detailed preparatory notes to get the writing flowing again.

Make rough sketches of diagrams or graphs. Keep a numbered list of references as they are included in your writing and put any quoted material inside quotation marks (see Section 11 ).

Write the Conclusion next, followed by the Introduction. Do not write the Summary at this stage.

This is the stage at which your report will start to take shape as a professional, technical document. In revising what you have drafted you must bear in mind the following, important principle;

- the essence of a successful technical report lies in how accurately and concisely it conveys the intended information to the intended readership.

During year 1, term 1 you will be learning how to write formal English for technical communication. This includes examples of the most common pitfalls in the use of English and how to avoid them. Use what you learn and the recommended books to guide you. Most importantly, when you read through what you have written, you must ask yourself these questions;

- Does that sentence/paragraph/section say what I want and mean it to say? If not, write it in a different way.

- Are there any words/sentences/paragraphs which could be removed without affecting the information which I am trying to convey? If so, remove them.

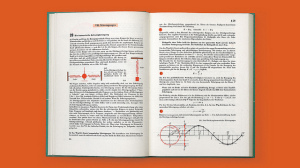

It is often the case that technical information is most concisely and clearly conveyed by means other than words. Imagine how you would describe an electrical circuit layout using words rather than a circuit diagram. Here are some simple guidelines;

The appearance of a report is no less important than its content. An attractive, clearly organised report stands a better chance of being read. Use a standard, 12pt, font, such as Times New Roman, for the main text. Use different font sizes, bold, italic and underline where appropriate but not to excess. Too many changes of type style can look very fussy.

Use heading and sub-headings to break up the text and to guide the reader. They should be based on the logical sequence which you identified at the planning stage but with enough sub-headings to break up the material into manageable chunks. The use of numbering and type size and style can clarify the structure as follows;

- In the main text you must always refer to any diagram, graph or table which you use.

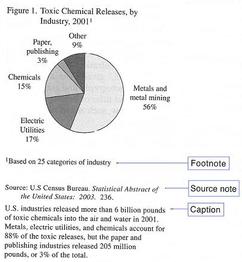

- Label diagrams and graphs as follows; Figure 1.2 Graph of energy output as a function of wave height. In this example, the second diagram in section 1 would be referred to by "...see figure 1.2..."

- Label tables in a similar fashion; Table 3.1 Performance specifications of a range of commercially available GaAsFET devices In this example, the first table in section 3 might be referred to by "...with reference to the performance specifications provided in Table 3.1..."

- Number equations as follows; F(dB) = 10*log 10 (F) (3.6) In this example, the sixth equation in section 3 might be referred to by "...noise figure in decibels as given by eqn (3.6)..."

Whenever you make use of other people's facts or ideas, you must indicate this in the text with a number which refers to an item in the list of references. Any phrases, sentences or paragraphs which are copied unaltered must be enclosed in quotation marks and referenced by a number. Material which is not reproduced unaltered should not be in quotation marks but must still be referenced. It is not sufficient to list the sources of information at the end of the report; you must indicate the sources of information individually within the report using the reference numbering system.

Information that is not referenced is assumed to be either common knowledge or your own work or ideas; if it is not, then it is assumed to be plagiarised i.e. you have knowingly copied someone else's words, facts or ideas without reference, passing them off as your own. This is a serious offence . If the person copied from is a fellow student, then this offence is known as collusion and is equally serious. Examination boards can, and do, impose penalties for these offences ranging from loss of marks to disqualification from the award of a degree

This warning applies equally to information obtained from the Internet. It is very easy for markers to identify words and images that have been copied directly from web sites. If you do this without acknowledging the source of your information and putting the words in quotation marks then your report will be sent to the Investigating Officer and you may be called before a disciplinary panel.

Your report should now be nearly complete with an introduction, main text in sections, conclusions, properly formatted references and bibliography and any appendices. Now you must add the page numbers, contents and title pages and write the summary.

The summary, with the title, should indicate the scope of the report and give the main results and conclusions. It must be intelligible without the rest of the report. Many people may read, and refer to, a report summary but only a few may read the full report, as often happens in a professional organisation.

- Purpose - a short version of the report and a guide to the report.

- Length - short, typically not more than 100-300 words

- Content - provide information, not just a description of the report.

This refers to the checking of every aspect of a piece of written work from the content to the layout and is an absolutely necessary part of the writing process. You should acquire the habit of never sending or submitting any piece of written work, from email to course work, without at least one and preferably several processes of proofreading. In addition, it is not possible for you, as the author of a long piece of writing, to proofread accurately yourself; you are too familiar with what you have written and will not spot all the mistakes.

When you have finished your report, and before you staple it, you must check it very carefully yourself. You should then give it to someone else, e.g. one of your fellow students, to read carefully and check for any errors in content, style, structure and layout. You should record the name of this person in your acknowledgements.

Two useful tips;

- Do not bother with style and formatting of a document until the penultimate or final draft.

- Do not try to get graphics finalised until the text content is complete.

- Davies J.W. Communication Skills - A Guide for Engineering and Applied Science Students (2nd ed., Prentice Hall, 2001)

- van Emden J. Effective communication for Science and Technology (Palgrave 2001)

- van Emden J. A Handbook of Writing for Engineers 2nd ed. (Macmillan 1998)

- van Emden J. and Easteal J. Technical Writing and Speaking, an Introduction (McGraw-Hill 1996)

- Pfeiffer W.S. Pocket Guide to Technical Writing (Prentice Hall 1998)

- Eisenberg A. Effective Technical Communication (McGraw-Hill 1992)

Updated and revised by the Department of Engineering & Design, November 2022

School Office: School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, Chichester 1 Room 002, Falmer, Brighton, BN1 9QJ [email protected] T 01273 (67) 8195 School Office opening hours: School Office open Monday – Friday 09:00-15:00, phone lines open Monday-Friday 09:00-17:00 School Office location [PDF 1.74MB]

Copyright © 2024, University of Sussex

7.4 Technical Reports

Longer technical reports can take on many different forms (and names), but most, such as recommendation and evaluation reports, do essentially the same thing: they provide a careful study of a situation or problem , and often recommend what should be done to improve that situation or problem .

The structural principle fundamental to these types of reports is this: you provide not only your recommendation, choice, or judgment, but also the data, analysis, discussion, and the conclusions leading to it. That way, readers can check your findings, your logic, and your conclusions to make sure your methodology was sound and that they can agree with your recommendation. Your goal is to convince the reader to agree with you by using your careful research, detailed analysis, rhetorical style, and documentation.

Composing Reports

When creating a report of any type, the general problem-solving approach works well for most technical reports; t he steps below in Table 7.4 , generally coincide with how you organize your report’s information.

Structuring Reports

- INTRODUCTION : T he introduction should clearly indicate the document’s purpose. Your introduction should discuss the “unsatisfactory situation” that has given rise to this report (in other words, the reason(s) for the report), and the requirements that must be met. Your reader may also need some background. Finally, provide an overview of the contents of the report. The following section provides additional information on writing report introductions.

- TECHNICAL BACKGROUND : S ome recommendation or feasibility reports may require technical discussion in order to make the rest of the report meaningful. The dilemma with this kind of information is whether to put it in a section of its own or to fit it into the comparison sections where it is relevant. For example, a discussion of power and speed of tablet computers is going to necessitate some discussion of RAM, megahertz, and processors. Should you put that in a section that compares the tablets according to power and speed? Should you keep the comparison neat and clean, limited strictly to the comparison and the conclusion? Maybe all the technical background can be pitched in its own section—either toward the front of the report or in an appendix.

- REQUIREMENTS AND CRITERIA : A critical part of feasibility and recommendation reports is the discussion of the requirements (objectives and constraints) you’ll use to reach the final decision or recommendation. Here are some examples:

- If you’re trying to recommend a tablet computer for use by employees, your requirements are likely to involve size, cost, hard-disk storage, display quality, durability, and battery function.

- If you’re looking into the feasibility of providing every student at Linn-Benton Community College with a free transportation pass, you’d need define the basic requirements of such a program—what it would be expected to accomplish, problems that it would have to avoid, how much it would cost, and so on.

- If you’re evaluating the recent implementation of a public transit system in your area, you’d need to know what was originally expected of the program and then compare (see “Comparative Analysis” below) its actual results to those requirements.

Requirements can be defined in several ways:

Numerical Values : many requirements are stated as maximum or minimum numerical values. For example, there may be a cost requirement—the tablet should cost no more than $900.

Yes/No Values : some requirements are simply a yes-no question. Does the tablet come equipped with Bluetooth? Is the car equipped with voice recognition?

Ratings Values : in some cases, key considerations cannot be handled either with numerical values or yes/no values. For example, your organization might want a tablet that has an ease-of-use rating of at least “good” by some nationally accepted ratings group. Or you may have to assign ratings yourself.

The requirements section should also discuss how important the individual requirements are in relation to each other. Picture the typical situation where no one option is best in all categories of comparison. One option is cheaper; another has more functions; one has better ease-of-use ratings; another is known to be more durable. Set up your requirements so that they dictate a “winner” from a situation where there is no obvious winner.

- DISCUSSION OF SOLUTION OPTIONS : In certain kinds of feasibility or recommendation reports, you’ll need to explain how you narrowed the field of choices down to the ones your report focuses on. Often, this follows right after the discussion of the requirements. Your basic requirements may well narrow the field down for you. But there may be other considerations that disqualify other options—explain these as well.

Additionally, you may need to provide brief technical descriptions of the options themselves. In this description section, you provide a general discussion of the options so that readers will know something about them. The discussion at this stage is not comparative. It’s just a general orientation to the options. In the tablets example, you might want to give some brief, general specifications on each model about to be compared (see below).

- COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS : O ne of the most important parts of a feasibility or recommendation report is the comparison of the options. Remember that you include this section so that readers can follow the logic of your analysis and come up with different conclusions if they desire. This comparison can be structured using a “block” (whole-to-whole) approach, or an “alternating” (point-by-point) approach.

The comparative section should end with a conclusion that sums up the relative strengths and weaknesses of each option and indicates which option is the best choice in that particular category of comparison. Of course, it won’t always be easy to state a clear winner—you may have to qualify the conclusions in various ways, providing multiple conclusions for different conditions. *NOTE : If you were writing an evaluative report, you wouldn’t be comparing options so much as you’d be comparing the thing being evaluated against the requirements placed upon it and/or the expectations people had of it. For example, if you were evaluating your town’s new public transit system, you might compare what the initiative’s original expectations were with how effectively it has met those expectations.

- SUMMARY TABLE : A fter the individual comparisons, include a summary table that summarizes the conclusions from the comparative analysis section. Some readers are more likely to pay attention to details in a table (like the one above) than in paragraphs; however, you still have to write up a clear summary paragraph of your findings.

- CONCLUSIONS : the conclusions section of a feasibility or recommendation report ties together all of the conclusions you have already reached in each section. In other words, in this section, you restate the individual conclusions. For example, you might note which model had the best price, which had the best battery function, which was most user-friendly, and so on. You could also give a summary of the relative strengths and weakness of each option based on how well they meet the criteria.

The conclusions section must untangle all the conflicting conclusions and somehow reach the final conclusion, which is the one that states the best choice. Thus, the conclusion section first lists the primary conclusions —the simple, single-category ones. Then it must state secondary conclusions —the ones that balance conflicting primary conclusions. For example, if one tablet is the least inexpensive but has poor battery function, but another is the most expensive but has good battery function, which do you choose and why? The secondary conclusion would state the answer to this dilemma.

- RECOMMENDATIONS : the final section states recommendations and directly address the problem outlined in the introduction. These may at times seem repetitive, but remember that some readers may skip right to the recommendation section. Also, there will be some cases where there may be a best choice but you wouldn’t want to recommend it. Early in their history, laptop computers were heavy and unreliable—there may have been one model that was better than the rest, but even it was not worth having. You may want to recommend further research, a pilot project, or a re-design of one of the options discussed.

The recommendation section should outline what further work needs to be done, based solidly on the information presented previously in the report and responding directly to the needs outlined in the beginning. In some cases, you may need to recommend several ranked options based on different possibilities.

For more information on what technical reports are and how to write them, watch “ Technical Report Meaning and Explanation ” from The Audiopedia:

Additional Resources

- “ How to Write A Technical Paper ” by Michael Ernst, University of Washington

- “ Report Design ,” from Online Technical Writing

- “ Engineering Report Guidelines ” (PDF example of a style guide for engineers from Technical Writing Essentials )

Technical Writing at LBCC Copyright © 2020 by Will Fleming is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.2: Types of Technical Reports

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 51520

- Tiffani Reardon, Tammy Powell, Jonathan Arnett, Monique Logan, & Cassie Race

- Kennesaw State University

Learning Objective

Upon completion of this chapter, readers will be able to:

- Identify common types of technical documents.

- Summarize the purposes and formats of common types of technical documents.

Types of Technical Documents

For the final report in some technical-writing courses, you can write one of (or even a combination of) several different types of reports. If there is some other type of report that you know about and want to write, get with your instructor to discuss it.

This chapter briefly defines these different report types; some are covered in full detail elsewhere in this book; the rest are described here. But to get everything in one place, all the reports are briefly defined here, with cross-references to where their presentations occur:

Standard operating policies and procedures

These are the operating documents for organizations; they contain rules and regulations on how the organization and its members are expected to perform. Policies and procedures are like instructions, but they go much further. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) are more for procedures in which a process is performed--for example, taking a dental impression.

Recommendation, feasibility, evaluation reports

This group of similar reports does things like compare several options against a set of requirements and recommend one; considers an idea (plan, project) in terms of its "feasibility," for example, some combination of its technical, economical, social practicality or possibility; passes judgement on the worth or value of a thing by comparing it to a set of requirements, or criteria.

Technical background reports

This type is the hardest one to define but the one that most people write. It focuses on a technical topic, provides background on that topic for a specific set of readers who have specific needs for it. This report does not supply instructions, nor does it supply recommendations in any systematic way, nor does it report new and original data.

Technical guides and handbooks

Closely related to technical report but differing somewhat in purpose and audience are technical guides and handbooks.

Primary research reports

This type presents findings and interpretation from laboratory or field research.

Business plans

This type is a proposal to start a new business.

Technical specifications

This type presents descriptive and operational details on a new or updated product.

Technical Background Reports

The technical background report is hard to define—it's not a lot of things, but it's hard to say what it is. It doesn't provide step-by-step directions on how to do something in the way that instructions do. It does not formally provide recommendations in the way that feasibility reports do. It does not report data from original research and draw conclusions in the way that primary research reports do.

So what does the technical background report do? It provides information on a technical topic but in such a way that is adapted for a particular audience that has specific needs for that information. Imagine a topic like this: renal disease and therapy. A technical background report on this topic would not dump out a ten-ton textbook containing everything you could possibly say about it. It would select information about the topic suited to a specific group of readers who had specific needs and uses for the information. Imagine the audience was a group of engineers bidding on a contract to do part of the work for a dialysis clinic. Yes, they need to know about renal disease and its therapy, but only to the extent that it has to do with their areas of expertise. Such a background report might also include some basic discussion of renal disease and its treatment, but no more than what the engineers need to do their work and to interact with representatives of the clinic.

One of the reports is an exploration of global warming, or the greenhouse effect, as it is called in the report. Notice that it discusses causes, then explores the effects, then discusses what can be done about it.

Typical contents and organization of technical background reports. Unlike most of the other reports discussed in this course guide, the technical background report does not have a common set of contents. Because it focuses on a specific technical topic for specific audiences who have specific needs or uses for the information, it grabs at whatever type of contents it needs to get the job done. You use a lot of intuition to plan this type of report. For example, with the report on renal disease and treatment, you'd probably want to discuss what renal disease is, what causes it, how it is treated, and what kinds of technologies are involved in the treatment. If you don't fully trust your intuition, use a checklist like the following:

- Definitions —Define the potentially unfamiliar terms associated with the topic. Write extended definitions if there are key terms or if they are particularly difficult to explain.

- Causes —Explain what causes are related to the topic. For example, with the renal disease topic, what causes the disease?

- Effects —Explain what are the consequences, results, or effects associated with the topic. With the renal disease topic, what happens to people with the disease; what effects do the various treatments have?

- Types —Discuss the different types or categories associated with the topic. For example, are there different types of renal disease; are there different categories of treatment?

- Historical background —Discuss relevant history related to the topic. Discuss people, events, and past theories related to the topic.

- Processes —Discuss mechanical, natural, human-controlled processes related to the topic. Explain step by step how the process occurs. For example, what are the phases of the renal disease cycle; what typically happens to a person with a specific form of the disease?